Abstract

Predisposition to food allergies may reflect a type 2 immune response (IR) bias in neonates due to the intrauterine environment required to maintain pregnancy. The hygiene hypothesis states that lack of early environmental stimulus leading to inappropriate development and bias in IR may also contribute. Here, the ability of heat-killed Escherichia coli, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), or muramyl dipeptide (MDP) to alter IR bias and subsequent allergic response in neonatal pigs was investigated. Three groups of three litters of pigs (12 pigs/litter) were given intramuscular injections of E. coli, LPS, MDP, or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (control) and subsequently sensitized to the egg white allergen ovomucoid using an established protocol. To evaluate change in IR bias, immunoglobulin isotype-associated antibody activity (AbA), concentrations of type 1 and 2 and proinflammatory cytokines released from mitogen-stimulated blood mononuclear cells, and the percentage of T-regulatory cells (T-regs) in blood were measured. Clinical signs of allergy were assessed after oral challenge with egg white. The greatest effect on IR bias was observed in MDP-treated pigs, which had a type 2-biased phenotype by isotype-specific AbA, cytokine production, and a low proportion of T-regs. LPS-treated pigs had decreased type 1- and type 2-associated AbA. E. coli-treated pigs displayed increased response to Ovm as AbA and had more balanced cytokine profiles, as well as the highest proportion of T-regs. Accordingly, pigs treated with MDP were more susceptible to allergy than PBS controls, while pigs treated with LPS were less susceptible. Treatment with E. coli did not significantly alter the frequency of clinical signs.

INTRODUCTION

The high prevalence of allergic disease in developed countries, estimated to be approximately 30% (46), is an important health problem. The rapid, recent increase in the incidence and prevalence of allergy can be attributed to environmental change, as stated by the hygiene hypothesis. The hygiene hypothesis, originally proposed by Strachan in 1989 (39), has been refined and states that microbial components and their proposed allergy-preventing potential are no longer present in the environment in sufficient quantity and/or quality to ensure proper development of the immune system, leading to imbalances in immune response (IR) and predisposition to allergic disease (12). While much epidemiological evidence supports the role of the environment in this increase, a genetic component also exists; however, the heritability of allergy is that of a complex polygenic disorder, such that genetic traits differ between allergic individuals (31). Therefore, due to the complex nature of allergic disease, standard treatments are limited to allergen avoidance, nutritional support, and immediate access to emergency medication (38). Although many allergen-specific immunotherapies have been investigated (1, 2, 3, 43), general, allergen-nonspecific treatments to control allergic predisposition and clinical allergy, regardless of the inciting allergen, would be of great benefit (1).

Predisposition to food allergies is attributed to a type 2 imbalance in IR. In an allergic reaction, type 2 cells produce cytokines (interleukin 4 [IL-4], IL-5, IL-13) that promote B lymphocyte immunoglobulin (Ig) isotype switching from IgG to IgE, thus increasing IgE-related antibody (36). Antibody associated with IgE mediates type I hypersensitivity reactions by sensitizing mast cells, platelets, and basophils for allergen-induced release of vasoconstrictive and smooth-muscle-activating mediators, such as histamine (13).

It is widely accepted that newborn animals have a type 2-biased immune system due to the intrauterine environment required to maintain pregnancy (45). This type 2 bias leads to selective susceptibility to microbial infection as well as the development of allergic disease (47). This bias is due in part to the low frequency and immaturity of neonatal dendritic cells (DCs), which results in diminished production of IL-12-secreting T-helper 1 (Th1; type 1) cells and the dominance of IL-4-producing T-helper 2 (Th2; type 2) cells upon secondary exposure to an antigen (47). To prevent allergy in neonates and at later stages, it would be beneficial to trigger the maturation of DCs and activation of other Ag-presenting cells, thus increasing available IL-12 to counteract the effect of IL-4 (19). This could be achieved by the activation of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Some Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs) and their ligands have been reported to promote type 1 IR. When administered intranasally to neonatal mice, nonliving, nongenetically modified particles of Lactococcus lactis peptidoglycan (PGN) displaying the Yersinia pestis Ag LcrV induced antibody production and type 1-associated cell-mediated IR specific to LcrV. Moreover, these mice were protected from lethal infection with Y. pestis (28). Protection was thought to be mediated by binding of PGN to TLR-2. Peptidoglycan is also recognized by NOD1 and NOD2 (40); the smallest recognizable component of PGN is muramyl dipeptide (MDP) (42), the ligand for NOD2. The bacterial component lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the ligand for TLR-4, also has type 1-promoting, allergy-protective effects in a mouse model of allergy (9).

Most individuals who suffer from food allergy are polysensitized and therefore allergic to more than one food; this is problematic when developing allergen-specific immunotherapies, as each allergen would require a different course of therapy. The use of allergen-nonspecific therapy could circumvent this problem by enabling change in the host IR, which ideally would induce tolerance toward all food allergens (20). Previously, in a neonatal pig model of food allergy to the egg white allergen ovomucoid (Ovm) (33), intramuscular injections (i.m.) of heat-killed Escherichia coli, on each of the first 7 days of life, prevented clinical signs of allergy upon subsequent sensitization and oral challenge with egg white (35). Similarly, live, orally administered Lactococcus lactis treatment prevented allergic sensitization and clinical signs to Ovm and was associated with an increase in type 1 IR bias as indicated by Ig isotype-specific antibody activity (AbA) ratios and a decrease in type 2 cytokine production in treated pigs (32). Although the mechanisms of this reduction in allergy were not investigated, it is likely that interactions between PRRs and microbial-associated molecular patterns were involved.

The use of pigs to investigate experimental food allergy may be advantageous (15). Swine are useful for comparative studies, as they are similar to humans in size, organ development, physiology, and disease progression (21). In addition, pigs are outbred, similar to humans, perhaps better mimicking the effect of environmental influences than do inbred mice. The clinical signs of allergy in pigs are similar to those in humans, and several studies have been reported (11, 15, 16, 32, 33, 35, 41).

In this study, we examined in swine the ability of heat-killed E. coli, LPS, or MDP to alter IR phenotype against a background of allergic sensitization to Ovm. Change in phenotype was observed by measuring Ig isotype-specific AbA to Ovm, type 1 and 2 and proinflammatory cytokine production from mitogen-stimulated blood mononuclear cells (BMCs), and the proportion of T-regulatory cells (T-regs) compared with those of untreated, sensitized controls. It was hypothesized that heat-killed E. coli, LPS, and MDP alter the IR phenotype and expression of allergy in neonatal pigs sensitized to the egg white allergen Ovm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and design.

A total of nine litters of newborn Yorkshire pigs, born to Yorkshire sows, 12 pigs per litter, and three litters per treatment, were used. The pigs were housed and maintained under normal husbandry conditions at the Arkell Swine Research Station (University of Guelph). During the experimental period, vaccinations and antibiotics were withheld from all pigs. Animal use was approved by the Animal Care Committee at the University of Guelph under guidelines of the Canadian Council of Animal Care.

Treatments and sensitization with ovomucoid.

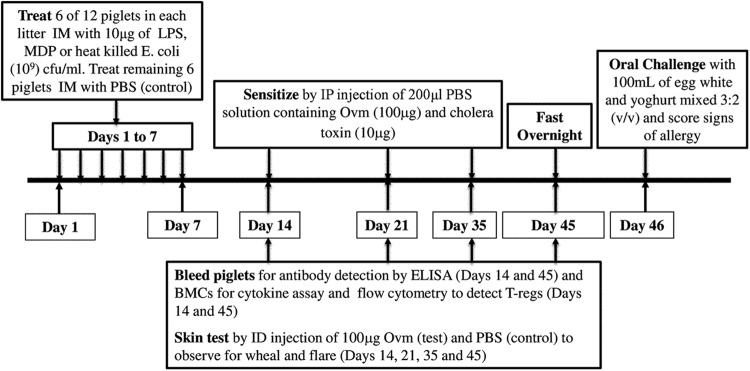

Fig. 1 summarizes the treatment, sensitization, sampling, and challenge schedule. Three litters of pigs were assigned to one of three treatment groups, and half of the pigs in each treatment group were treated with either heat-killed E. coli (n = 11 pigs; BL21 Star cells, 109 CFU/ml; Invitrogen, Burlington, ON, Canada), LPS, (n = 15 pigs; from E. coli 055:B5, 10 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON), or MDP (n = 16 pigs; from Staphylococcus aureus, 10 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). Other pigs in each group, 18 per group, were treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; n = 49 pigs, pooled across all litters; negative control). Values of n reflect final number of pigs in each group. Pigs in each litter were ranked by weight regardless of gender and assigned to the treatment or control group, ensuring approximately equal distribution of mass across groups. Each pig received an intramuscular (i.m.) injection of 1 ml of the designated treatments on each of the first 7 days of life, split into two equal volumes injected into opposite lateral cervical areas. Days of age were equivalent to experimental days. On days 14, 21, and 35, intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of 100 μg of purified Ovm, prepared in lab (33), adjuvanted with 10 μg of cholera toxin (List Biologicals, CA), were given to all pigs as previously described (33). Blood was taken from the retro-orbital sinus on day 45 to measure the effect of each treatment on bias of IR phenotype. On day 45, piglets were fasted for 18 h prior to oral challenge on day 46 with 100 ml of egg white mixed with yogurt in a 3:2 (vol/vol) ratio. The egg white-yogurt mixture was delivered to each pig using a Kendall Monoject 60-ml Toomey tip syringe (Covidien, Mansfield, MA) with an attached polypropylene tube to allow suckling.

Fig 1.

Pretreatment and sensitization protocol. Three groups of pigs, each group containing three litters of approximately 12 pigs/litter treated with intramuscular (i.m.) injections of heat-killed E. coli (109 CFU/ml in 1 ml PBS; n = 11 pigs), lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 10 μg/ml in 1 ml PBS; n = 15 pigs), muramyl dipeptide (MDP; 10 μg/ml in 1 ml PBS; n = 16 pigs), or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; n = 49 pigs, pooled across all litters) in a split-litter design. Six pigs in each litter of 12 received treatment with bacteria or bacterial components; the remaining pigs were treated with PBS as a negative control on each of the first 7 days of life. Injections were divided into two equal volumes and administered into lateral cervical areas. Pigs were then sensitized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of ovomucoid (Ovm; 100 μg/ml) mixed with 10 μg/ml of cholera toxin (CT) on days 14, 21, and 35. Skin tests were conducted on days 14, 21, 35, and 45 to monitor sensitization by intradermal (i.d.) injection of Ovm (100 μg). On day 45, pigs were fasted overnight and challenged on day 46 with 100 ml of egg white and yoghurt mixed 3:2 (vol/vol), observed for at least 2 h for clinical signs of allergy, and assigned clinical scores (Table 1). Blood was taken via the retro-orbital sinus on days 14 and 45 to measure immunoglobulin isotype-associated antibody activity by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and on day 45 to isolate blood mononuclear cells (BMCs) for culture and quantification of cytokine concentrations and to measure the proportion of circulating T-regulatory cells (T-regs) by flow cytometry. Experimental days are equal to days of age.

Cutaneous hypersensitivity to ovomucoid.

To monitor sensitization to Ovm, intradermal (ID) skin tests were performed prior to primary i.p. sensitization on day 14 and on days 21, 35, and 45. Two separate injection sites were marked on the medial aspect of opposite thighs, one for the test Ag Ovm and another for the PBS control. Injections of 100 μl of Ovm (10 μg/ml) or PBS were made using a tuberculin syringe with a 25-gauge needle (Covidien) and monitored for wheal and flare approximately 10 to 15 min after injection. Wheal and flare reactions were evaluated by three separate observers.

Clinical signs.

Following oral challenge, pigs were observed for at least 2 h by three researchers blinded to treatment group and monitored for clinical signs of allergy. Each pig was assessed individually and assigned a score as outlined in Table 1. In order to be classified as allergic, pigs had to exhibit signs such as cutaneous erythema and/or gastrointestinal signs, such as vomiting or diarrhea, and to have a minimum clinical score of 1. The clinical signs of scratching, sneezing, isolation, and lethargy and respiratory difficulty had to occur in combination with one of the aforementioned signs to be scored as a sign and were not themselves sufficient to identify a pig as allergic (Table 1). Thus, signs were additive, and clinical score was indicative of the severity of the allergic reaction. In severe responses, epinephrine was administered until allergic signs were alleviated.

Table 1.

Clinical score assessment for systemic and local signs of allergy

| Clinical sign | Score awarded |

|---|---|

| Isolation and lethargy | 1 |

| Repeated scratching | 0.5 |

| Repeated sneezing | 0.5 |

| Cutaneous erythemaa | |

| Isolated erythema | 1 |

| Partial erythema | 2 |

| Confluent erythema | 3 |

| Emesisa | |

| One episode | 1 |

| Repeated episodes | 2 |

| Diarrheaa | |

| One episode | 1 |

| Repeated episodes | 2 |

| Respiratory difficulty | 2 |

Pigs must display at least one of these signs to be considered allergic.

Measurement of immunoglobulin isotype-specific antibody activity to ovomucoid by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Sera obtained on day 45 and stored at −20°C were used to determine the Ig isotype-specific AbA to Ovm by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Anti-pig isotype IgG, heavy and light chain specific (rabbit polyclonal, H+L; Sigma-Aldrich), IgG1, IgG2 (mouse monoclonal; AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC), and IgE (rabbit polyclonal) (34) were used to quantify related antibody activity. Optimal Ag-coating conditions were determined using polystyrene, flat-bottomed, Immulon 2HB, 96-well plates (Dynex Technologies Inc., VWR International, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and 0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate coating buffer (pH 9.6). Plates were washed three times (ELX 405 automatic plate washer; Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT) with 200 μl 0.05% Tween-PBS (PBST; 0.01 M, pH 7.4, per well). Wells were blocked with 3.0% PBST (pH 7.4), 200 μl per well, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Washing was repeated, and sera diluted in 0.05% PBST were added at 100 μl per well in triplicate. Controls included wells without sera and negative (pooled serum from preimmunized piglets with low AbA) and positive (pooled serum from postimmunized piglets with high AbA) sera. Plates were incubated for 2 h at RT and washed. Alkaline phosphatase (Alk-phos)-conjugated rabbit anti-swine IgG (H+L), diluted in 0.05% Tween–Tris-buffered saline (TTBS; pH 7.4) for Ovm-specific IgG (H+L) activity or unconjugated monoclonal mouse anti-swine IgG1 or IgG2 for the isotype-specific ELISAs was added at 100 μl/well and incubated for 1 h at RT. Plates were washed, and for IgG, 100 μl p-nitrophenol phosphate substrate (Sigma-Aldrich), dissolved in 10% diethanolamine (pH 9.8) to a concentration of 1.0 mg/ml, was added to each well and incubated at RT in the dark. For IgG1 or IgG2 isotype-specific ELISAs, Alk-phos-conjugated goat-anti-mouse IgG (H+L specific; Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in TTBS was added at 100 μl/well after being washed and incubated for 1 h. Substrate was added after plates were washed, as described for IgG ELISA, and incubated at RT in the dark. Optical density (OD) of test sample wells was measured at 405 nm (EL 808; Biotek Instruments) when the positive-control OD reached 1.0. Mean values of OD were obtained from triplicates of test serum and from the controls. The protocol for Ovm-specific IgE activity was similar to that outlined by Rupa et al. (34). For individual sera, antibody activity of triplicate means were expressed as percent of the positive-control values for each plate with the following equation: % of positive-control activity = (mean test serum OD/mean positive-control serum OD) × 100.

Measurement of type 1, type 2, and proinflammatory cytokine concentrations.

Blood collected on day 45 was used to isolate BMCs for culture and stimulation with the T-cell mitogen phytohemagglutinin-P (PHA-P; Sigma-Aldrich). Concentrations of type 1 and 2 and proinflammatory cytokines were measured in culture supernatant using capture ELISA.

Blood mononuclear cells were isolated from whole blood using density gradient centrifugation on Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. To summarize, approximately 3 ml of blood was collected from each pig in an EDTA-coated 5-ml Vacutainer tube (Becton, Dickinson, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Blood was diluted with 3 ml of sterile PBS and underlaid with 6 ml of Histopaque at RT. The samples were then centrifuged at 400 × g for 30 min at RT, after which the layer containing BMCs was removed and transferred to a new, sterile tube and washed twice at RT in PBS. Resulting BMCs were resuspended in complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen), l-glutamine (2 mM; Invitrogen), and penicillin (100 U/ml)-streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Cells were counted using an automatic cell counter (T-C10 cell counter; Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and diluted with DMEM to 2.5 × 106 cells/ml, cultured in triplicate on 24-well plates (Costar; Sigma-Aldrich) with 1 ml of medium and 10 μg of PHA-P per well. After 96 h of incubation, cell culture supernatant was removed, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C.

The levels of type 1 cytokines gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and IL-12p40, type 2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-10, and proinflammatory cytokine IL-17A were measured in cell culture supernatant using porcine quantitative sandwich ELISA kits for each cytokine exactly as outlined by the manufacturers' instructions (Invitrogen [IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-10]; Kingfisher, St. Paul, MN [IL-17A]; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN [IL-12p40]). In summary, plates were coated with mouse monoclonal anti-porcine IFN-γ, IL-4, or IL-10 overnight at 4° and IL-12p40 overnight at RT. Mouse monoclonal anti-porcine IL-17A was precoated on the assay plate. Culture supernatant from PHA-P-stimulated and unstimulated BMCs and standards of known cytokine concentration were added in duplicate to wells of flat-bottomed, Immulon 2HB, 96-well plates (Dynex Technologies Inc.) and were incubated as specified by the manufacturer per assay. After the wells were washed, 50 μl of biotinylated anti-cytokine antibody was added to each well and incubated for 1 h. Plates were then washed, and 100 μl of streptavidin-peroxidase was added. After a final wash, color was developed with 100 μl of substrate solution (tetramethylbenzidine; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at RT in the dark. Stop solution (1.8 N sulfuric acid) was added, and OD was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. Optical density was directly proportional to the concentration of cytokine. Linear standard curves were plotted for concentrations using GraphPad Prism software and used to estimate cytokine concentration in test samples. For all cytokines assayed, if a test sample OD was below the sensitivity of the test to detect positivity, the lowest concentration detected on the standard curve was assigned to that sample.

Determination of proportion of T-regulatory cells in lymphocytes of whole blood by flow cytometry.

Blood collected on day 45 was also used to measure the proportion of blood T-regs from all pigs by flow cytometry, on the basis of CD25 and forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) positivity (18). One hundred microliters of blood from each pig was used for double staining with mouse anti-porcine CD25 (VMRD, Pullman, WA) and R-phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-mouse FoxP3 (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) (14). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 (Invitrogen) was used as a secondary antibody to detect anti-CD25 antibody. Isotype and unstained controls were included to confirm specific staining of anti-CD25 and anti-Foxp3 and to adjust compensation. The antibody isotype controls used were mouse IgG1 negative control (AbD Serotec) for CD25 and PE-conjugated rat IgG2a for FoxP3. Unstained samples were treated with wash buffer, PBS with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (PBA). The staining protocol used is summarized briefly below.

Staining for CD25 was conducted first in conjunction with the appropriate negative isotype control. Beginning with 100 μl of blood, to each sample, 100 μl at 10 μg/ml of mouse anti-porcine CD25 was added and 100 μl of rat IgG1 at 10 μg/ml was added to the CD25 isotype control. One hundred microliters of PBA was added to the unstained and FoxP3 isotype controls. All tubes were mixed gently by vortexing and incubated for 15 min at RT followed by two washes with 1 ml of PBA by centrifugation for 7 min at 470 × g at 4°C. After each wash, supernatant was discarded. Next, 50 μl of FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 at 10 μg/ml was added to samples and CD25 isotype controls, PBA was added to the unstained and FoxP3 isotype controls, and all tubes were mixed and incubated in the dark at RT for 15 min. Following incubation, 1.5 ml of BD FACS red blood cell lysing solution (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, ON, Canada) was added to samples and all controls and centrifuged at 470 × g at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was discarded, and 500 μl of permeabilization buffer (0.1% saponin in PBS), to enable intracellular staining, was added to samples and all controls, mixed, and incubated in the dark at RT for 10 min. Two milliliters of PBA was added to the permeabilization buffer and centrifuged at 470 × g at 4°C, following which the resulting supernatant was discarded. To detect FoxP3, 100 μl of PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse FoxP3 at 0.5 μg/ml was added to samples, and 100 μl of PE-conjugated rat IgG2a at 0.5 μg/ml was added to the FoxP3 isotype controls. The unstained and CD25 isotype controls received 100 μl of PBA, and all tubes were mixed and incubated at RT in the dark for 30 min. All tubes were washed with 2 ml of PBA as described above, supernatant was discarded, and 200 μl of 1.0% paraformaldehyde was added. Tubes were stored at 4°C for approximately 18 h before the proportion of T-regs was measured by flow cytometry using a Becton, Dickinson FacScan flow cytometer (Becton, Dickinson) and FACstation software (BD Biosciences). Percentage of T-regs was determined by gating on lymphocytes using forward and side scatter and identification of double positive cells for the markers CD25 and FoxP3. Resulting data were visualized using FCS Express version 4.0 software (De Novo Software, Los Angeles, CA) and analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0.

Statistical analyses.

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software version 5.0. Significance of difference in percent positive control of AbA, ratios of AbA, concentration of cytokines, ratios of cytokine concentrations, and percentages of T-regs were all determined using the unpaired Student's t test for normally distributed data. Welch's correction was applied for nonnormally distributed data as determined by the F-test. All data were pooled according to treatment group and expressed as means. Significance was taken at P values of <0.05, and significant trends were recognized at P values of <0.1.

RESULTS

Effect of pretreatments with heat-killed E. coli, LPS, and MDP on clinical signs of allergy. (i) Treatment with heat-killed E. coli does not affect frequency of ovomucoid allergy.

Pretreatment of pigs with heat-killed E. coli reduced frequency of clinical signs but not significantly (P = 0.1169). Of the three litters treated with E. coli (n = 11 pigs), two litters contained pigs which became allergic, and one litter, although all pigs were sensitized as evidenced by wheal and flare on day 45, did not. This phenotype was designated clinically tolerant. Twenty-seven percent of E. coli-treated pigs and 33% of PBS-treated pigs were allergic. Sixty-five percent of pigs in this group were classified as clinically tolerant regardless of treatment. Treatment with E. coli had no effect on severity of clinical signs.

(ii) Treatment with LPS decreases the frequency of ovomucoid allergy.

As hypothesized, pigs treated with LPS before allergic sensitization with Ovm were less likely to become allergic after oral challenge with egg white than pigs treated with PBS. As in the E. coli-treated group, all pigs were sensitized, and one of the three LPS-treated litters sensitized did not display clinical signs. Of the pigs treated with LPS (n = 15), 30% were allergic, compared to 44% of PBS controls (n = 16 pigs; P = 0.0405). Seventy-seven percent of pigs in this group were classified as clinically tolerant regardless of treatment. Treatment with LPS had no effect on severity of clinical signs.

(iii) Treatment with MDP increased frequency of ovomucoid allergy.

Pigs treated with MDP before sensitization to Ovm were more likely to become allergic than untreated PBS controls. This is contrary to the hypothesis but consistent with the type 2-biased IR phenotype observed. One hundred percent of pigs were sensitized to Ovm as evidenced by wheal and flare on day 45. Of the pigs treated with MDP (n = 16), 39% developed clinical signs and were therefore allergic, while only 12% of pigs treated with PBS displayed clinical signs (n = 15; P < 0.0001). Eighty-four percent of pigs in this group were classified as clinically tolerant regardless of treatment. Treatment with MDP had no effect on severity of clinical signs.

Effect of heat-killed E. coli, LPS, and MDP on immune response phenotype. (i) Isotype-specific serum antibody activity to ovomucoid indicates that Escherichia coli has the greatest adjuvancy.

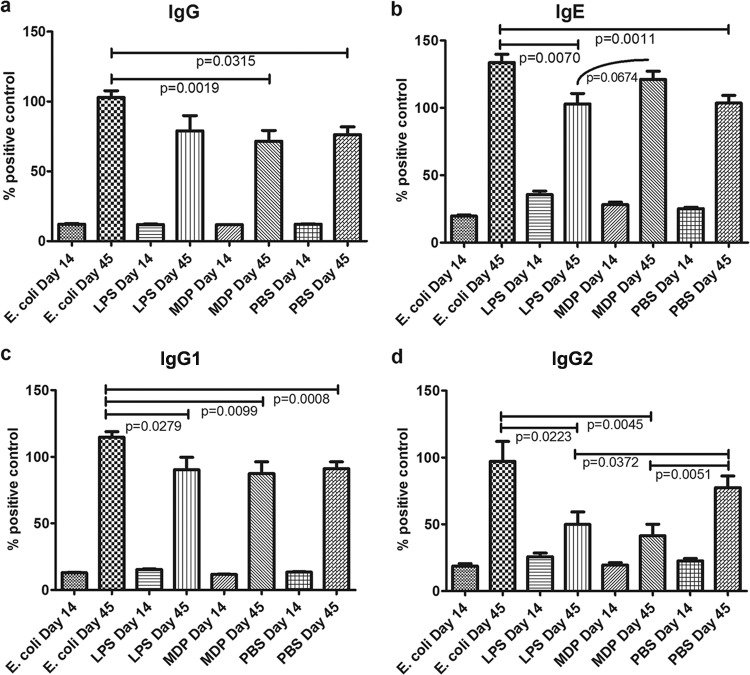

Isotype-specific AbA to Ovm was measured in pigs from each treatment group on day 45. Antibody activity in serum on day 45 was significantly greater than on day 14, indicating an antibody response to Ovm. Escherichia coli had the greatest adjuvant effect, as evidenced by increased AbA of all isotypes compared to that of other treatments, with the exception of IgG (H+L) compared to LPS (Fig. 2a to d). The IgG (H+L) or total AbA in E. coli-treated pigs was greater than that of PBS (P = 0.0315)- or MDP (P = 0.0019)-treated pigs. The IgE AbA was greater in E. coli-treated pigs than in LPS (P = 0.0070)- or PBS (P = 0.0011)-treated pigs. There was a trend indicating that the IgE AbA of MDP-treated pigs was greater than that of LPS (P = 0.0674)-treated animals (Fig. 2b). The type 2-associated IgG1 AbA was also greatest in the E. coli-treated pigs compared to that of other treatments (LPS, P = 0.0279; MDP, P = 0.0099; PBS, P = 0.0008; Fig. 2c). The greatest difference between treatment groups was observed for IgG2 AbA. Once again, E. coli-treated animals had more IgG2 activity than LPS (P = 0.0223)- or MDP (P = 0.0045)-treated pigs. Furthermore, PBS-treated pigs had more IgG2-associated AbA than LPS (P = 0.0372)- and MDP (P = 0.0051)-treated pigs (Fig. 2d).

Fig 2.

Ovomucoid-specific antibody activity of pigs treated with heat-killed E. coli, LPS, MDP, or PBS (control). Serum immunoglobulin isotype-specific antibody activity (AbA) to ovomucoid (Ovm) was monitored by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. All pigs, regardless of treatment group, produced significantly more Ovm-specific IgG (H+L), IgE, IgG1, and IgG2 AbA at 45 days of age than at 14 (P < 0.0001). Escherichia coli-treated pigs (n = 11) produced more Ovm-specific IgG than PBS (n = 49 pigs, pooled across all litters)-treated controls and MDP (n = 16)-treated piglets. Escherichia coli-treated piglets had more IgE AbA than PBS-treated controls and LPS (n = 15)-treated pigs. A trend toward decreased activity of IgE in LPS-treated pigs compared to MDP was also noted. E. coli-treated pigs had more IgG1 activity than all other treatment groups. More Ovm-specific IgG2 activity was present in E. coli-treated pigs than in LPS- or MDP-treated pigs, while both LPS- and MDP-treated pigs had less IgG2-specific AbA than PBS controls. Individual serum means were expressed as percent of the positive-control values for each plate as follows: % of positive-control activity = (mean test serum OD/mean positive-control serum OD) × 100 (unpaired t test, Welch's correction applied when necessary, significance taken at P < 0.05, trends at P < 0.1).

(ii) Immunoglobulin isotype bias of antibody reflects ability of muramyl dipeptide to induce type 2 bias.

Ratios of isotype-specific AbA to Ovm were calculated in order to compare isotype usage between treatment groups. Results indicate that MDP is an inducer of type 2-associated antibodies in this experimental system. The ratio of IgG1 to IgG2 was higher in serum from MDP-treated pigs than in the serum from E. coli (P = 0.0045)- or PBS (P = 0.0161)-treated pigs (Fig. 3a). The LPS-treated animals had a greater ratio of IgG1 to IgG2 than the E. coli (P = 0.0223)-treated pigs. In addition, MDP-treated pigs had a higher IgE/IgG2 ratio than pigs in all other treatment groups (E. coli, P = 0.0007; LPS, P = 0.0028; PBS, P = 0.0014; Fig. 3b). Notably, there was a strong trend toward E. coli-treated pigs having a lower IgE/IgG2 ratio than PBS-treated pigs (P = 0.0567).

Fig 3.

Ratio of isotype-specific antibody activity to ovomucoid in pigs treated with heat-killed E. coli, LPS, MDP, or PBS (control). Serum isotype-specific antibody activity (AbA) to ovomucoid was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and the ratio of AbA was calculated for each pig. The ratio of IgG1 to IgG2 was increased in MDP (n = 16)-treated piglets compared to that in E. coli (n = 11)- and PBS (n = 49, pooled across all litters)-treated piglets. This ratio was also increased in LPS (n = 15)-treated piglets compared to in E. coli-treated piglets. The IgE/IgG2 ratio was greater in MDP-treated piglets than in piglets in all other treatment groups. There was a trend toward a greater IgE/IgG2 ratio in PBS-treated pigs than in those treated with E. coli (unpaired t test, Welch's correction applied when necessary, significance taken at P < 0.05, trends at P < 0.1).

(iii) Cytokine concentration indicates E. coli-treated animals may better regulate cytokine production when sensitized to ovomucoid.

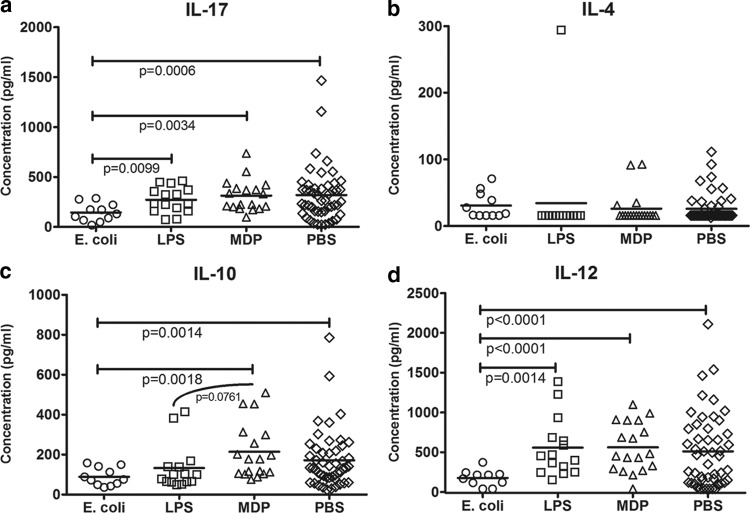

The concentrations of two type 1 cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-12p40), two type 2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-10), and the proinflammatory cytokine IL-17A were tested. There was no detectable IFN-γ in any of the BMC sample culture supernatants (data not shown); however, IL-12 was measurable. The culture supernatant of BMCs from E. coli-treated animals had less IL-12 than supernatants from pigs in any other treatment group (LPS, P = 0.0014; MDP, P < 0.0001; PBS, P < 0.0001; Fig. 4d). The concentration of IL-17A was significantly less in the BMC supernatant from E. coli-treated pigs than in all other treatment groups, including PBS controls (P = 0.0006; LPS, P = 0.0099; MDP, P = 0.0034; Fig. 4a). Although the concentration of IL-4 in culture supernatant was minimal, BMCs from some animals in all treatment groups did produce measurable amounts of IL-4. The difference between the treatment groups in IL-4 production, however, was not significantly different (Fig. 4b). For IL-10, it was found that BMCs from MDP-treated animals produced more IL-10 than those from E. coli-treated pigs (P = 0.0018), and there was a trend toward a similar effect compared to LPS-treated pigs (P = 0.0761; Fig. 4c). There was greater production of IL-10 in BMCs from PBS-treated pigs than from E. coli-treated pigs (P = 0.0014).

Fig 4.

Cytokine expression by PHA-P-stimulated BMCs from piglets treated with heat-killed E. coli, LPS, MDP, or PBS (control). Blood was collected from piglets at 45 days of age, postsensitization to ovomucoid. Blood mononuclear cells (BMCs) from each pig were isolated on a density gradient of Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich) and cultured at 2.5 × 106 cells/ml for 96 h, stimulated with 10 μg/ml of PHA-P (Sigma-Aldrich). Culture supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C. Cytokine concentration was measured using capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Invitrogen, IL-10 and IL-4; Kingfisher, IL-17; R&D Systems, IL-12). The concentration of IL-17 was lower in the supernatant of BMCs from E. coli-treated (n = 11) pigs than from all others. No difference in the expression of IL-4 was noted from the supernatant of cells from pigs in each treatment group. Cells from piglets treated with MDP (n = 16) and PBS (n = 49, pooled across all litters) had an increased expression of IL-10 compared to that in E. coli-treated pigs. Cells from MDP-treated pigs trended toward increased IL-10 production compared to cells from LPS-treated (n = 15) pigs. The concentration of IL-12 was lower in supernatant from cells of E. coli-treated pigs than in any other treatment group (unpaired t test, Welch's correction applied when necessary, significance taken at P < 0.05, trends at P < 0.1). Please note the difference in scale on the y axis.

(iv) Cytokine bias as described by ratios indicates that LPS treatment induces relatively greater IL-12 production.

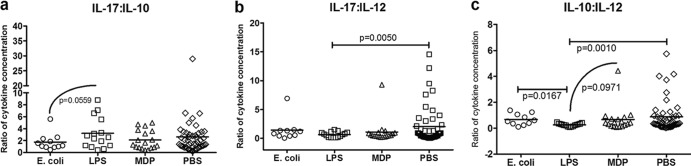

The ratio of IL-17 to IL-10 reflected the balanced cytokine production found in E. coli-treated animals, as there was a strong trend indicating a decrease in this ratio between E. coli- and LPS-treated pigs (P = 0.0559; Fig. 5a). However, when comparing the ratio of IL-10 to IL-12, E. coli-treated pigs favored IL-10, due to significantly greater IL-12 production in LPS-treated pigs (P = 0.0167; Fig. 5c). In comparison to MDP- and PBS-treated pigs, the ratio of IL-10 to IL-12 was less in the LPS-treated group (P = 0.0971, P = 0.0010; Fig. 5c). The ratio of IL-17 to IL-12 was greater in BMCs from PBS-treated pigs than from LPS-treated pigs (P = 0.0050; Fig. 5b), although there was no apparent difference in concentration in these cytokines between these groups. Ratios comparing measured cytokines to IL-4 are not described due to low frequency of positive individuals and minimal concentrations detected, as mentioned above.

Fig 5.

Ratio of cytokine expression by PHA-P-stimulated BMCs from pigs treated with heat-killed E. coli, LPS, MDP, or PBS (control). Blood was collected from pigs at 45 days of age, postsensitization to ovomucoid. BMCs were isolated using a density gradient of Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich) and cultured at 2.5 × 106 cells/ml for 96 h, stimulated with 10 μg/ml of PHA-P (Sigma-Aldrich). Culture supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C. The concentrations of cytokines were measured using capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Invitrogen, IL-10; Kingfisher, IL-17; R&D Systems, IL-12). Ratios of cytokines were calculated to elucidate possible bias as a result of treatment. There was a trend toward an increased ratio of IL-17 to IL-10 in cells from LPS-treated pigs (n = 15) compared to those from pigs treated with E. coli (n = 11). The ratio of IL-17 to IL-12 was greater in supernatant from cells of PBS-treated pigs (n = 49, pooled across all litters) than in cells from LPS-treated pigs. In cells from LPS-treated pigs, the ratio of IL-10 to IL-12 was less than that in cells from all other treatment groups (unpaired t test, Welch's correction applied when necessary, significance taken at P < 0.05, trends at P < 0.1). Please note difference in scale.

(v) Proportion of T-regulatory cells reflects an immune response biasing effect of both E. coli and MDP.

Compared to all other groups, E. coli-treated pigs had the greatest proportion of circulating T-regs (LPS, P = 0.0103; MDP, P = 0.0035; PBS, P = 0.0180; Fig. 6). In addition, not only did MDP-treated pigs have a lower proportion of T-regs than E. coli-treated pigs, they also had a lower proportion than PBS control pigs (P = 0.0344; Fig. 6).

Fig 6.

Percentage of T-regulatory cells from blood of pigs treated with heat-killed E. coli, LPS, MDP, and PBS (control). Blood was collected from pigs at 45 days of age, postsensitization, prior to oral challenge with egg white and prepared for identification of CD25+ FoxP3+ T-regs by flow cytometry. Percentage of T-regs was measured from 10 μl of whole blood from each pig. Pigs treated with E. coli (n = 11) had higher percentages of T-regs than all others. Pigs treated with MDP (n = 16) had a lower percentage of T-regs than pigs treated with PBS) (n = 49, pooled across all litters) (unpaired t test, Welch's correction applied when necessary, significance taken at P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

It is reported here that daily pretreatments with heat-killed E. coli, LPS, or MDP influence the IR bias of neonatal pigs undergoing allergic sensitization to Ovm. The greatest effect was observed in MDP-treated pigs, which had a proallergic, type 2-biased phenotype by isotype-specific AbA and cytokine production profiles. Additionally, circulating T-regs were lowest in MDP-treated pigs. Pigs treated with LPS had both decreased type 1- and type 2-associated AbA and relatively increased type 1-associated cytokine production. Escherichia coli-treated pigs displayed an increased ability to respond to Ovm in terms of AbA and had more balanced cytokine profiles than pigs otherwise treated, as well as the highest proportion of circulating T-regs. Given this, it was found that pigs treated with MDP were more susceptible to developing clinical allergy than those treated with E. coli or LPS, of which, only LPS was protective against allergy.

Treatment with MDP caused the most significant change in frequency of clinical signs. Pigs treated with MDP were more likely than PBS controls to become allergic. This was an unexpected result. Muramyl dipeptide is the smallest component of PGN which is recognized by PRRs. Peptidoglycan, a ligand of TLR2, induces Th1-polarized IRs, enhancing protection against fatal infection with Yersinia pestis in mice (28). Moreover, MDP is an NOD2 ligand. Stimulation of NOD2 is known to enhance protection against sepsis, bacterial and viral infections, and some parasitic infections by inducing production of proinflammatory cytokines and enhancing phagocytic activity of immune system cells (14). This type 1-inducing effect of MDP binding to NOD2 may occur, however, only in the presence of other TLR ligands (22). It is likely that NOD2 is a critical mediator of microbial-induced polarization of the IR, which when stimulated in conjunction with other PRR ligands induces a type 1-associated bias and when stimulated alone induces a type 2-associated bias (22). Furthermore, independent MDP binding may instead induce a Th-17-polarized response (23), which in the case of allergy may enhance clinical signs. Indeed, in this experiment, alteration in IR by MDP was type 2 biased as reflected in decreased Ovm-specific IgG2 AbA, isotype-specific antibody ratios favoring type 2-associated (IgG1, IgE) AbA, increased production of the type 2 cytokine IL-10 in PHA-P-stimulated BMCs, a greater ratio of IL-10 to IL-12 than in LPS-treated pigs, and a low proportion of circulating CD25+ FoxP3+ T-regs. Immunoglobulin G2 activity to Ovm was lowest in MDP-treated pigs (Fig. 2d). There are six to eight isotypes of porcine IgG (5), and only two, IgG1 and IgG2, have been functionally characterized. Immunoglobulin G2 is type 1 associated, while IgG1 is type 2 (8). Pigs pretreated orally with live L. lactis had increased allergen-specific IgG2 AbA levels compared to those of PBS controls, associated with a decrease in sensitization to, and clinical signs of, Ovm allergy (32). Since L. lactis PGN mediates protection against infectious disease in mice and is linked to type 1 induction of IR (28), the decreased activity associated with IgG2 in MDP-treated animals in the present experiment was unexpected. In contrast, the ratio of IgG1-to-IgG2 Ovm-specific AbA was greatest in MDP-treated pigs (Fig. 3a), as was the ratio of IgE to IgG2 (Fig. 3b). The type 2 IR-promoting effect of pretreatment with MDP is consistent with the observed increased frequency of allergy in pigs treated with MDP.

Escherichia coli treatment also had IR-altering activity, reflected in increased serum antibody to the allergen Ovm, regulation of type 1 and 2 and proinflammatory cytokine production, and a greater proportion of blood T-regs than animals in all other groups. However, treatment with E. coli did not have a significant effect on the frequency of pigs with clinical signs of allergy. Pretreatment with heat-killed E. coli had an effect on IR bias in terms of ratios of isotype-specific AbA compared to those of LPS and MDP but was not significantly different than treatment with the PBS control (Fig. 2a and b). Still, an increased capacity for adjuvancy was observed for E. coli treatment. The isotype-specific AbA to Ovm was greater in E. coli-treated animals than in animals treated with LPS and MDP and, depending upon the isotype, PBS controls. This adjuvancy may be attributed to the complexity of E. coli. When germfree pigs were given bacterial components CpG oligonucleotide (CpG), LPS, or MDP via i.p. injection and tested for IgG-, IgM-, and IgA-associated AbA, pigs treated with CpG alone could produce IgM antibodies, and those treated with LPS or MDP could not. This IgM antibody-inducing activity was enhanced by coadministration of MDP but not LPS. Immunoglobulin G and IgA AbA in pigs treated with bacterial components alone were undetectable or less than that of germfree pigs colonized with a nonpathogenic strain of E. coli (4). Although the pigs in the present experiment were born conventionally and were therefore colonized and able to mount an adaptive IR, the more potent adjuvant effect of E. coli was nevertheless observed.

Treatment with LPS had the least effect on IR bias, although some criteria reflect downregulation of type 2 IR. Nevertheless, LPS-treated pigs were less likely to display clinical signs of allergy after oral challenge. Immunoglobulin E activity was lower in LPS-treated pigs than in E. coli-treated pigs and trended toward lower activity than in MDP-treated pigs. The activity of IgG1 was also lower in LPS-treated pigs than in those treated with E. coli. This is indicative of a decreased type 2 antibody response to Ovm and may be expected to correlate with decreased clinical signs of allergy in LPS-treated animals. However, Ovm-specific IgG2 AbA was lower in LPS-treated pigs than in E. coli- or PBS-treated pigs and equal to that of MDP-treated pigs. This was surprising, as much evidence describes LPS as a powerful inducer of type 1 IR (44). Accordingly, although the concentration of IL-12 from BMCs of LPS-treated pigs was equal to that observed in BMCs from MDP- and PBS-treated pigs, it was greater than IL-12 production in E. coli-treated animals. Further, the ratio of IL-17 to IL-12 was less in BMCs from LPS-treated pigs than in BMCs from PBS-treated pigs, as was the ratio of IL-10 to IL-12, with a trend toward decrease in this ratio in LPS- compared to MDP- and E. coli-treated pigs. This suggests relative induction of type 1 IR in LPS-treated pigs. It is likely that LPS binding to TLR-4 induced anti-allergic type 1 polarizing changes, consistent with those found by Debarry et al. (9), who showed that Acinetobacter lwoffii F78 conveyed allergy protection by Th1 polarization of DCs by binding of LPS to TLR-4.

Concentrations of type 1 and 2 and proinflammatory cytokines corresponded to allergic outcomes and IR phenotype bias. Interleukin-17A is a proinflammatory cytokine produced by cells of the innate immune system as well as the newly identified T-helper 17 (Th17) subset. Elevated concentrations of IL-17 or mRNA have been observed in the lungs, sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluids, or sera of asthmatic patients and correlate with increased airway hypersensitivity (24), implying a role for IL-17 in allergy. Surprisingly, reports of a protective function for IL-17A in a mouse model of colitis speculate that IL-17A may directly inhibit Th1 cells by inhibiting IFN-γ production (25), a proallergic action. Therefore, pigs with elevated IL-17A may be more susceptible to allergy. In the present study, BMCs from E. coli-treated pigs produced less IL-17A than cells from pigs in any other group, although pigs in this group did not have reduced frequency of allergy compared to controls (P = 0.1169).

Interferon-γ was not detected in any of the pigs, although there was high sensitivity to the test standards in the assay. This may have been due to the time of sample collection (96 h); however, previous experiments with cells from pigs of similar age in the same research facility yielded measurable IFN-γ at this time point (data not shown). Previous research here has shown that the concentrations of IL-4 and IL-10, traditionally considered type 2 cytokines in pigs (29), are elevated in allergic animals and reduced in nonallergic pigs pretreated with live L. lactis (32). Therefore, the elevated concentration of IL-10 in MDP-treated pigs may reflect increased type 2 IR bias, leading to enhanced susceptibility to allergy. Since measurable amounts of IL-4 from culture supernatant was low, it may have been advantageous to measure IL-13, as it may mediate some or all of the activities of IL-4 in pigs (30). However, although attempts to measure IL-13 were made, it too was undetectable. This and the inability to measure IFN-γ may be due to the tendency of neonatal cells to produce large amounts of IL-17 and IL-10 and small amounts of IFN-γ and IL-12p70. Neonatal cells also have a restricted repertoire of cytokine production (27).

The induction of allergen-specific T-regs is a critical event which leads to the development of healthy immune response to allergens (1). Therefore, we measured the proportion of circulating T-regs as CD25+ FoxP3+ cells. Pigs from the type 2-biased MDP-treated group had fewer T-regs than other pigs, whereas IR-balanced E. coli-treated pigs had the most. In most nonallergic humans, in whom an active allergen-specific T-cell response can be detected, active in vitro suppression of allergy is mediated by inducible or natural T-regs (17). T-regulatory cells function through direct cell-cell interactions and the production of IL-10 and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) (7). In control of allergy, these cytokines complement each other to suppress type 1 and 2 IRs as well as the production of IgE, while promoting the production of IgA and the allergy-blocking isotype IgG4 in humans (1). Pathogenic Th17 responses are also controlled by T-regs (6); therefore, we conducted a Spearman's rank correlation test to determine if there was an inverse relationship between the proportion of T-regs and the concentration of IL-17A from BMCs on day 45. No correlation was found in any of the treatment groups (data not shown). Finally, new evidence which describes the necessity of inducible T-reg activation in lymph nodes and the subsequent migration of these optimally activated cells into sites of inflammation during an IR, allergy included (10), justifies measuring T-regs in circulation.

Pretreatment with LPS and MDP influenced the frequency of pigs with clinical signs of allergy; none of the treatments affected the severity of the allergic signs observed. Clinical signs in LPS-treated pigs were no less severe, as determined by clinical score (Table 1), than those in PBS-treated controls and vice versa in the case of MDP, for which, due to increased type 2 bias, one might expect clinical score to increase. This is suggestive of separate regulation of sensitization and allergic signs exemplified by the fact that 100% of pigs were sensitized and only 33% of pigs were allergic. Regulation at the effector phase appears to have occurred in this experiment and may have been controlled by T-regs, as MDP-treated pigs had the lowest proportion of circulating T-regs and the highest frequency of allergy. Mechanisms of T-reg control at the effector phase, including suppression of mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils by cell-to-cell contact, and the inhibition of effector T-cell infiltration to inflamed tissue by expression of regulatory cytokines (26) may have played a role in the prevention of clinical signs.

In the present experiment, pretreatment with heat-killed E. coli did not significantly reduce the frequency of pigs with clinical signs of allergy as previously reported (35). It may be speculated that the actual effect of E. coli treatment was masked by the low number of pigs in the E. coli-treated group (n = 11). Over the course of experimentation, pigs from all groups were lost due to infection with Streptococcus suis and in some cases Staphylococcus hyicus, which negatively affected group numbers, especially in the E. coli-treated group. In addition, pigs' IR to the type 2 Ag hen egg white lysozyme and the type 1 Ag Candida albicans in a standardized IR phenotyping protocol was found to vary in bias over time (37). This indicates that reproducibility is an important issue in experiments using conventionally housed, outbred animals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants to Bruce N. Wilkie from Ontario Pork, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture Food and Rural Affairs, and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). Julie Schmied was the recipient of a fellowship from the Allergen National Centre of Excellence.

Technical assistance of the Arkell Swine Research Station staff (University of Guelph) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 17 October 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Akdis CA, Akdis M. 2009. Mechanisms and treatment of allergic disease in the big picture of regulatory T cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 123: 735– 746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akdis M, Akdis CA. 2009. Therapeutic manipulation of immune tolerance in allergic disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8: 645– 660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Allen CW, Campbell DE, Kemp AS. 2009. Food allergy: is strict avoidance the only answer? Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 20: 415– 422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Butler JE, Francis DH, Freeling J, Weber P, Krieg AM. 2005. Piglets. IX. Three pathogen-associated molecular patterns act synergistically to allow germfree piglets to respond to type 2 thymus-independent and thymus-dependent antigens. J. Immunol. 4: 6772– 6785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Butler JE, Wertz N. 2006. Antibody repertoire development in fetal and neonatal piglets. XVII. IgG subclass transcription revisited with emphasis on new IgG3. J. Immunol. 177: 5480– 5489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chaudhry A, et al. 2009. CD4+ regulatory T cells control TH17 responses in a Stat3-dependent manner. Science 326: 986– 991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Corthay A. 2009. How do regulatory T-cells work? Scand. J. Immunol. 70: 326– 336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crawley A, Wilkie BN. 2003. Porcine Ig isotypes: function and molecular characteristics. Vaccine 21: 2911– 2922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Debarry J, Hanuszkiewicz A, Stein K, Holst O, Heine H. 2010. The allergy-protective properties of Acinetobacter lwoffii F78 are imparted by its lipopolysaccharide. Allergy 65: 690– 697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ding Y, Xu J, Bromberg JS. 2012. Regulatory T cell migration during an immune response. Trends Immunol. 33: 174– 180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fornhem C, Kumlin M, Lundberg JM, Alving K. 1995. Allergen-induced late-phase airways obstruction in the pig: mediator release and eosinophil recruitment. Eur. Respir. J. 8: 1100– 1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garn H, Renz H. 2007. Epidemiological and immunological evidence for the hygiene hypothesis. Immunobiology 212: 441– 452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gould HJ, Sutton BJ. 2008. IgE in allergy and asthma today. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8: 205– 217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hancock REW, Nijnik A, Philpott DJ. 2012. Modulating immunity as a therapy for bacterial infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10: 243– 254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hein WR, Griebel PJ. 2003. A road less travelled: large animal models in immunological research. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3: 79– 84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Helm RM, et al. 2002. A neonatal swine model for peanut allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 109: 136– 142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jartti T, et al. 2007. Association between CD4(+)CD25(high) T cells and atopy in children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 120: 177– 183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Käser T, Gerner W, Hammer SE, Patzl M, Saalmüller A. 2008. Detection of Foxp3 protein expression in porcine T lymphocytes. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 125: 92– 101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kollmann TR, et al. 2007. Induction of protective immunity to Listeria monocytogenes in neonates. J. Immunol. 178: 3695– 3701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lieberman Ja., Wang J. 2012. Nonallergen-specific treatments for food allergy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 12: 293– 301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lunney JK. 2007. Advances in swine biomedical model genomics. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 3: 179– 184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Magalhaes J, et al. 2011. Nucleotide oligomerization domain-containing proteins instruct T cell helper type 2 immunity through stromal activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108: 14896– 14901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Manni M, Ding W, Stohl L. 2011. Muramyl dipeptide induces Th17 polarization through activation of endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 186: 3356– 3363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oboki K, Ohno T, Saito H, Nakae S. 2008. Th17 and allergy. Allergol. Int. 57: 121– 134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O'Connor W, et al. 2009. A protective function for interleukin 17A in T cell-mediated intestinal inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 10: 603– 609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Palomares O, et al. 2010. Role of Treg in immune regulation of allergic diseases. Eur. J. Immunol. 40: 1232– 1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. PrabhuDas M, et al. 2011. Challenges in infant immunity: implications for responses to infection and vaccines. Nat. Immunol. 12: 189– 194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ramirez K, et al. 2010. Neonatal mucosal immunization with a non-living, non-genetically modified Lactococcus lactis vaccine carrier induces systemic and local Th1-type immunity and protects against lethal bacterial infection. Mucosal Immunol. 3: 159– 171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Raymond CR, Sidahmed AME, Wilkie BN. 2006. Effects of antigen and recombinant porcine cytokines on pig dendritic cell cytokine expression in vitro. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 111: 175– 185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Raymond CR, Wilkie BN. 2004. Th-1/Th-2 type cytokine profiles of pig T-cells cultured with antigen-treated monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Vaccine 22: 1016– 1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Romagnani S. 2004. Immunologic influences on allergy and the TH1/TH2 balance. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 113: 395– 400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rupa P, Schmied J, Wilkie BN. 2011. Prophylaxis of experimentally-induced ovomucoid allergy in neonatal pigs using Lactococcus lactis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 140: 23– 29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rupa P, Hamilton K, Cirinna M, Wilkie BN. 2008. A neonatal swine model of allergy induced by the major food allergen chicken ovomucoid (Gal d 1). Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 146: 11– 18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rupa P, Hamilton K, Cirinna M, Wilkie BN. 2008. Porcine IgE in the context of experimental food allergy: purification and isotype specific antibodies. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 125: 303– 314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rupa P, Schmied J, Lai S, Wilkie BN. 2009. Attenuation of allergy to ovomucoid in pigs by neonatal treatment with heat-killed Escherichia coli or E. coli producing porcine IFN-gamma. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 132: 78– 83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sashihara T, Sueki N, Ikegami S. 2006. An analysis of the effectiveness of heat-killed lactic acid bacteria in alleviating allergic diseases. J. Dairy Sci. 89: 2846– 2855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schmied J, Hamilton K, Rupa P, Oh S-Y, Wilkie B. 2012. Immune response phenotype induced by controlled immunization of neonatal pigs varies in type 1: type 2 bias. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 149: 11– 19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scurlock AM, Vickery BP, Hourihane JO, Burks AW. 2010. Pediatric food allergy and mucosal tolerance. Mucosal Immunol. 3: 345– 354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Strachan DP. 1989. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ 299: 1259– 1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Strober W, Murray PJ, Kitani A, Watanabe T. 2006. Signaling pathways and molecular interactions of NOD1 and NOD2. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6: 9– 20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thomas DJ, et al. 2011. Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 attenuates allergy development in a pig model. PLoS One 6: e16577 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Uehori J, et al. 2005. Dendritic cell maturation induced by muramyl dipeptide (MDP) derivatives: monoacylated MDP confers TLR2/TLR4 activation. J. Immunol. 174: 7096– 7103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vickery BP, et al. 2010. Individualized IgE-based dosing of egg oral immunotherapy and the development of tolerance. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 105: 444– 450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vosskuhl K, Greten TF, Manns MP, Korangy F, Wedemeyer J. 2010. Lipopolysaccharide-mediated mast cell activation induces IFN-gamma secretion by NK cells. J. Immunol. 185: 119– 125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wegmann TG, Lin H, Mosmann TR. 1993. Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal-fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a Th2 phenomenon? Immunol. Today 14: 353– 356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wills-Karp M, Nathan A, Page K, Karp CL. 2010. New insights into innate immune mechanisms underlying allergenicity. Mucosal Immunol. 3: 104– 110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zaghouani H, Hoeman CM, Adkins B. 2009. Neonatal immunity: faulty T-helpers and the shortcomings of dendritic cells. Trends Immunol. 30: 585– 591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]