Abstract

The prospective project MOSAR was conducted in five rehabilitation units: the Berck Maritime Hôpital (Berck, France), Fondazione Santa Lucia (Rome, Italy), Guttmann Institute (GI; Barcelona, Spain), and Loewenstein Hospital and Tel-Aviv Souraski Medical Center (TA) (Tel-Aviv, Israel). Patients were screened for carriage of Enterobacteriaceae resistant to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs) from admission until discharge. The aim of this study was to characterize the clonal structure, extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), and acquired AmpC-like cephalosporinases in the Escherichia coli populations collected. A total of 376 isolates were randomly selected. The overall number of sequence types (STs) was 76, including 7 STs that grouped at least 10 isolates from at least three centers each, namely, STs 10, 38, 69, 131, 405, 410, and 648. These clones comprised 65.2% of all isolates, and ST131 alone comprised 41.2%. Of 54 STs observed only in one center, some STs played a locally significant role, like ST156 and ST393 in GI or ST372 and ST398 in TA. Among 16 new STs, five arose from evolution within the ST10 and ST131 clonal complexes. ESBLs and AmpCs accounted for 94.7% and 5.6% of the ESC-hydrolyzing β-lactamases, respectively, being dominated by the CTX-M-like enzymes (79.9%), followed by the SHV (13.5%) and CMY-2 (5.3%) types. CTX-M-15 was the most prevalent β-lactamase overall (40.6%); other ubiquitous enzymes were CTX-M-14 and CMY-2. Almost none of the common clones correlated strictly with one β-lactamase; although 58.7% of ST131 isolates produced CTX-M-15, the clone also expressed nine other enzymes. A number of clone variants with specific pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and ESBL types were spread in some locales, potentially representing newly emerging E. coli epidemic strains.

INTRODUCTION

Escherichia coli is one of the key human pathogens, responsible for a variety of infections in both the hospital and the community. The most important is urinary tract infection and also bacteremia, intra-abdominal infections, nosocomial pneumonia, neonatal meningitis, and others (1). Treatment of these infections has become more and more problematic with time due to the increasing resistance of E. coli to antimicrobials, including the expanded-spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs). The main mechanism of resistance to ESCs in Enterobacteriaceae is the production of several types of β-lactamases, such as extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) or AmpC-like cephalosporinases, and E. coli is one of the major producers of these (2, 3). The frequency of ESBL and acquired AmpC producers in nosocomial E. coli populations has been constantly growing since the 1980s and 1990s, and since the early 2000s, such strains have been increasingly observed in the community as well (2–4). Two main factors have been responsible for this increase, namely, the dissemination of plasmids carrying the ESBL and AmpC genes and the clonal spread of producer strains (5, 6).

The recent introduction of multilocus sequence typing (MLST) schemes (7) has accelerated the accumulation of knowledge on the clonality of E. coli populations worldwide. Numerous reports have described a number of clones, often forming clonal complexes, that have disseminated in all continents. Some of them, usually belonging to the more virulent phylogroups B2 and D (8), have been associated with the rapid spread of resistance, such as ESBL production (6, 9). The main example has been the uropathogenic sequence type 131 (ST131), identified in 2008 as a global producer of the CTX-M-15 β-lactamase, which currently predominates among ESBLs (10–14).

The European Union-funded project MOSAR was a prospective study addressing various aspects of the spread of resistance in intensive care, surgical, and rehabilitation wards across Europe and Israel, as well as specific actions aimed at combating that (www.mosar-sic.org). One of its objectives was to reveal the clonal structure of ESC-resistant Enterobacteriaceae colonizing patients in rehabilitation units (RUs) in four densely populated areas. Here we show the results of the molecular analysis of E. coli strains identified during this project.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and clinical isolates.

Five RUs located in the north of Paris, France (Berck Maritime Hôpital [BM], Berck, France), Rome, Italy (Fondazione Santa Lucia [FS]), Barcelona, Spain (Guttmann Institute [GI]), and Tel-Aviv, Israel (Loewenstein Hospital [LH] and Tel-Aviv Souraski Medical Center [TA]), participated in the study upon the approval of their ethics committees. The units differ in types of patients and size (BM, 80 beds; FS, 106 beds; GI, 38 beds; LH, 45 beds; TA, 50 beds). From October 2008 to February 2011, rectal swab specimens for culture were collected from all patients at admission, 2 weeks later, and then once monthly and at discharge. Rectal swabs were plated onto Brilliance ESBL agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom); Enterobacteriaceae colonies were identified using the manufacturer's instructions. One colony of each morphotype was frozen and shipped to the National Medicines Institute, Warsaw, Poland, for definite analysis. Species identification was done with the Vitek 2 system (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). The phenotypic detection of ESBL and AmpC expression was carried out using the ESBL double-disk synergy test with disks containing cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefepime, and amoxicillin with clavulanate on Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid) nonsupplemented and supplemented with 250 μg/ml cloxacillin (15). E. coli isolates suspected of the high-level AmpC production (augmentation of inhibition zones upon supplementation with cloxacillin) were tested by PCR for acquired AmpC types (16).

Of the total of 2,389 ESC-resistant E. coli isolates identified in the RUs during the project, 376 patient-unique isolates with an ESBL and/or acquired AmpC, collected in 2008 and 2009, were randomly selected for the molecular analysis according to their study numbers (BM, n = 31; FS, n = 108, GI, n = 32, LH, n = 64; and TA, n = 141). The aim was to select at least 30 isolates per hospital; differences in numbers between particular sites resulted from differences in the timing of the clinical trials at the sites, the availability of cultures at the start of this analysis, and the overall number of ESC-resistant isolates at each institution. The majority of isolates from TA were also used in a separate study on colonization risk factors and the population dynamics of ESBL-positive E. coli, and a part of the molecular data are presented elsewhere (17).

Typing.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed as described previously (18) with the use of the XbaI restriction enzyme (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania). PFGE types and subtypes were discerned visually using the criteria of Tenover et al. (19). In order to construct dendrograms, electrophoretic patterns were compared by the BioNumerics Fingerprinting software (version 6.01; Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium), using the Dice coefficient, and clustering by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean with a 1% tolerance in band position differences. MLST was carried out as described previously (7); the database available at http://mlst.ucc.i.e., was used for assigning sequence types (STs) and clonal complexes. The clonal diversity indexes and confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated as described by Grundmann et al. (20). Classification of isolates into major E. coli phylogenetic groups was done by PCR (21).

β-Lactamase analysis.

β-Lactamase profiling was done by isoelectric focusing as reported previously (22), using a model 111 mini-isoelectric focusing cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Identification of the blaCTX-M-1-, blaCTX-M-2-, blaCTX-M-9-, blaCTX-M-25-, blaSHV-, blaTEM-, blaCMY-2-, and blaDHA-like genes was done by PCRs (23–26). Sequencing of the genes was performed as reported previously (23), using sets of consecutive primers specific for each gene type.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Clonal structure of the E. coli populations.

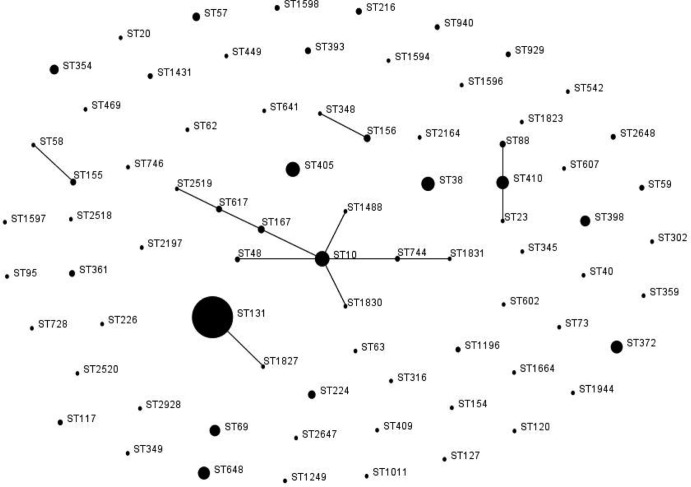

The 376 E. coli isolates were typed by PFGE, followed by MLST of representatives for each PFGE type; for larger types with subtypes, MLST was done on several isolates per type. Overall, 240 isolates were analyzed by MLST. A total of 76 clones (STs) were found (Tables 1 and 2; Fig. 1). The clonal diversity index for the entire collection was 81.9% (CI, 77.9 to 85.8%) and varied from 73.8% (CI, 64.3 to 83.2%) in FS, 80.9% (CI, 74.8 to 87.0%) in TA, 83.0% (CI, 69.4 to 96.2%) in BM, and 86.0% (CI, 79.6 to 92.4%) in LH to 91.3% (CI, 85.4 to 97.3%) in GI. This indicated that in general the E. coli populations were differentiated; however, the ongoing spread of specific strains likely played a notable role as well. Indeed, the detailed analysis (PFGE and β-lactamase profiling) revealed clusters of closely related isolates in each center, most significantly in FS and TA (discussed below).

Table 1.

Clonal complexes, geographic distribution, PFGE types, and ESBL or AmpC types of E. coli clones identified in at least two centers

| ST/clonea | Clonal complex | Phylogroupb | Center(s) | No. (%) of isolates | No. of PFGE types | ESBL or AmpC variant(s) (no. of isolates or center) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST131 | ST131 | B2 | BM | 13 | 6 | CTX-M-15 (8) and -14 (5) |

| FS | 55 | 19 | CTX-M-15 (50), -14 (2), -1 (1), and -2 (1); SHV-5 (1) | |||

| GI | 8 | 5 | CTX-M-15 (3), -14 (1), and -27 (1); SHV-12 (3) | |||

| LH | 21 | 13 | CTX-M-15 (15) and -27 (5); CMY-4 (1) | |||

| TA | 58 | 7 | CTX-M-27 (34), -15 (15), -14 (2), -39 (1), and -55 (1); CMY-4 (5) | |||

| 155 (41.2) | ||||||

| ST10 | ST10 | A | BM | 1 | 1 | CTX-M-15 |

| FS | 4 | 4 | CTX-M-2 (2) and -1 (1); CMY-2 (1) | |||

| GI | 3 | 2 | CTX-M-14 | |||

| LH | 8 | 4 | CTX-M-15 (4); SHV-12 (4) | |||

| TA | 3 | 3 | CTX-M-14 (1); SHV-5 (1) and -12 (1) | |||

| 19 (5.1) | ||||||

| ST354 | ST354 | D | BM | 1 | 1 | TEM-24 |

| FS | 2 | 2 | CTX-M-1 (1); CMY-2 (1) | |||

| GI | 1 | 1 | CTX-M-14 | |||

| LH | 1 | NTc | CMY-2 | |||

| TA | 2 | 2 | CTX-M-2 (1) and -15 (1) | |||

| 7 (1.9) | ||||||

| ST405 | ST405 | D | BM | 1 | 1 | CMY-2 |

| FS | 4 | 3 | CTX-M-15 (2), -1 (1), and -14 (1) | |||

| LH | 3 | 2 | CTX-M-9 (1) and -15 (1); CMY-2 (1) | |||

| TA | 10 | 7 | CTX-M-15 (5) and -9 (3); SHV-12 (1); CMY-2 (1) | |||

| 18 (4.9) | ||||||

| ST38 | ST38 | D | FS | 3 | 1 | CTX-M-2 |

| GI | 1 | 1 | CTX-M-14 | |||

| LH | 4 | 4 | CTX-M-15 (3) and -9 (1) | |||

| TA | 8 | 7 | CTX-M-15 (4), -14 (2), -9 (1), and -27 (1) | |||

| 16 (4.3) | ||||||

| ST648 | ST648 | D | BM | 2 | 2 | CTX-M-1 (1) and -15 (1) |

| FS | 4 | 4 | CTX-M-15 (3) and -14 (1) | |||

| LH | 1 | 1 | CTX-M-15 | |||

| TA | 6 | 2 + 1 NT | CTX-M-15 (5) and -14 (1) | |||

| 13 (3.5) | ||||||

| ST410 | ST23 | A | FS | 3 | 2 | CTX-M-15 (2); SHV-12 (1) |

| LH | 8 | 3 | SHV-12 | |||

| TA | 3 | 2 | SHV-12 | |||

| 14 (3.7) | ||||||

| ST69 | ST69 | D | FS | 1 | 1 | CTX-M-15 |

| LH | 2 | 2 | CTX-M-14 | |||

| TA | 7 | 3 | CTX-M-14 (5) and -15 (1); CMY-4 (1) | |||

| 10 (2.7) | ||||||

| ST57 | ST350 | D | FS | 1 | 1 | CTX-M-1 |

| GI | 3 | 2 | CTX-M-14 (2); SHV-12 (2) | |||

| LH | 1 | NT | CMY-2 | |||

| 5 (1.3) | ||||||

| ST155 | ST155 | B1 | FS | 1 | 1 | CTX-M-1 |

| GI | 1 | 1 | SHV-2 | |||

| LH | 1 | 1 | CTX-M-14 | |||

| 3 (0.8) | ||||||

| STs observed in two centers | ||||||

| ST224 | B1 | FS, LH | 5 (1.3) | 4 | CTX-M-1 (FS); CTX-M-1 and -15; SHV-12 (LH) | |

| ST167 | ST10 | A | FS, LH | 4 (1.1) | 3 | CTX-M-15 (FS); CMY-42 (LH) |

| ST88 | ST23 | A | FS, TA | 3 (0.8) | 2 | CTX-M-1 (FS); CTX-M-100 (TA) |

| ST216 | A | GI, TA | 3 (0.8) | 3 | CTX-M-3 (GI); SHV-12 (TA) | |

| ST617 | ST10 | A | FS, LH | 3 (0.8) | 2 + 1 NT | CTX-M-15 (FS); CTX-M-27; SHV-12 (LH) |

| ST48 | ST10 | A | FS, TA | 2 (0.5) | 2 | CTX-M-1 (FS); SHV-12 (TA) |

| ST59 | ST59 | D | FS, TA | 2 (0.5) | 2 | CTX-M-1 (FS); CTX-M-14 (TA) |

| ST117 | D | FS, GI | 2 (0.5) | 2 | CTX-M-1 (FS); CTX-M-14 (GI) | |

| ST744 | ST10 | A | BM, LH | 2 (0.5) | 2 | CTX-M-15 (BM); CMY-2 (LH) |

| ST929 | B2 | BM, TA | 2 (0.5) | 2 | CTX-M-15 (BM); CTX-M-55 (TA) | |

| ST940 | B1 | BM, TA | 2 (0.5) | 2 | CTX-M-15 (BM and TA) | |

| ST1431 | A | FS, TA | 2 (0.5) | 2 | CTX-M-2 (FS and TA) | |

| Total | 292 (77.7) |

STs are ordered according to (i) the number of centers in which these were identified and (ii) their prevalence in the entire collection of isolates. STs observed in two centers are presented one per line, without splitting into the center-specific groups.

E. coli phylogroups were adopted from reference 6, 9, 27, or 28 (STs 10, 38, 57, 59, 69, 117, 131, 155, 354, 405, 410, and 648) or determined in this work (STs 48, 88, 167, 216, 224, 617, 744, 929, 940, and 1431).

NT, nontypeable by PFGE due to repeated DNA degradation.

Table 2.

Clonal complexes, PFGE types, and ESBL or AmpC types of E. coli clones identified in a single center

| Center | ST/clone (clonal complex)a | No. of isolates | No. of PFGE types | ESBL or AmpC variant(s) (no. of isolates) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | 23 (23), 58 (155), 127, 154, 345, 349 (349), 1594, 1664, 2164, 2647 | 10 | 10 | CTX-M-1 (3), -9 (1), and -15 (2); TEM-24 (2) and -52 (1); CMY-2 (1); DHA-1 (1) |

| FS | 20 (20), 63, 73, 120, 302, 359, 728, 1249, 1488 (10), 1823, 1827 (131), 1831 (10), 1944, 2518, 2648, 2928 | 17 | 15 + 1 NTb | CTX-M-1 (12), -9 (1), and -15 (2); SHV-2a (1); CMY-2 (1) |

| GI | 156 (156) | 4 | 2 + 2 NT | CTX-M-14 (2); CMY-2 (2) |

| 393 (31) | 3 | NT | CTX-M-32 | |

| 40 (40), 226 (226), 602 (446), 607, 1830 (10), 2197 | 6 | 6 | CTX-M-14 (2) and -15 (1); SHV-12 (3) | |

| LH | 316 (278), 361, 542, 1011, 2519 (10), 2520 | 8 | 7 | CTX-M-2 (1), -14 (1), -15 (5), and -39 (1) |

| TA | 372 | 13 | 2 | CTX-M-15 (1); SHV-5 (12) |

| 398 (398) | 9 | 1 | CTX-M-39 (8); SHV-5 (1) | |

| 62, 95 (95), 348 (156), 409, 449 (31), 469 (469), 641 (86), 746, 1196, 1596, 1597, 1598 | 14 | 11 + 1 NT | CTX-M-2 (3), -14 (1), and -15 (7); SHV-5 (1) and -12 (2) |

The first number refers to the ST of a particular clone, and the following number in parentheses refers to the clonal complex if a clone is a member of such a complex. Numbers in bold refer to new STs identified in this work. The STs observed in a center are shown in one line together, except for the more prevalent STs (ST156 and ST393 in GI and ST372 and ST398 in TA), which are presented separately.

NT, nontypeable by PFGE due to repeated DNA degradation.

Fig 1.

MLST-based population structure of ESBL- and/or AmpC-producing E. coli isolates identified in the five rehabilitation centers (BM, FS, GI, LH, and TA) during the MOSAR study. The scheme was constructed using eBURST analysis. STs are symbolized by dots; the size of a dot corresponds to the number of isolates belonging to an ST. SLVs are linked by solid lines.

Major clones.

Twenty-two clones were observed in at least two centers in different countries (n = 292; 77.7%), while 10 STs were identified in three or more hospitals each (Table 1). Of these 10 clones, 7 comprised at least 10 isolates each, namely, STs 10, 38, 69, 131, 405, 410, and 648, accounting for 65.2% of the study isolates (n = 245). The situation in which a large collection of E. coli isolates is dominated by a small number of clones was often observed, but the composition of such groups differed according to the region and the type and source of isolates (29–32). The seven clones represent different phylogroups (8), namely, groups A (STs 10 and 410), B2 (ST131), and D (STs 38, 69, 405, and 648), and were reported in many studies performed worldwide on isolates from hospital and community patients (6, 29, 31–34). Their isolates varied in virulence inter- and intraclonally (7, 29, 33, 35, 36); recently, they have often been associated with diverse resistance traits, including ESBLs and other β-lactamases (6, 29, 31–35, 37–40).

(i) ST131.

The clonal distribution was dominated by ST131, to which 41.2% of the isolates (n = 155) were classified. It prevailed in all of the centers, though at various rates: from 25.0% in GI, 32.8% in LH, 41.1% in TA, and 41.9% in BM to 50.9% in FS. A single isolate from FS represented a new ST, ST1827, being a single-locus variant (SLV) of ST131 and belonging to its clonal complex. ST131 has been of the highest concern since 2008, when it was identified to be the global CTX-M-15 producer (10, 12, 13). It has been less frequent among susceptible isolates (13, 30, 41), but the apparent ease with which it acquired resistance combined with its virulence has fuelled its pandemic spread (13). Except for a few studies (27, 40), ST131 has been the dominant clone in most studies on ESBL-producing E. coli (6, 13, 31, 35, 42); therefore, its high frequency here was not surprising. The lowest rate in GI is concordant with other reports from Spain and Barcelona (33, 43, 44); so are the higher rates in France (BM) and Italy (FS) (41, 45). The data for Israel are the first from this country and some of the first from the Middle East (12, 34), showing a remarkable prevalence of ST131 that is higher than that in Egypt (34).

(ii) ST10.

ST10 was far less frequent (n = 19; 5.1%), but like ST131, it was identified in all of the hospitals. Moreover, eight other clones found sporadically in two sites or one site each (STs 48, 167, 617, 744, 1488, 1830, 1831, and 2519) belonged to the ST10 complex, grouping 34 isolates (9.0%) altogether. Four of these STs were new: ST1488 (from FS) and ST1830 (GI) were SLVs of ST10, while ST1831 (FS) and ST2519 (LH) were SLVs of the ST10-related ST744 and ST617, respectively. In all but one case, such SLV pairs occurred in the corresponding centers; therefore, the new STs might have evolved in these. The complex was especially remarkable in the Israeli center LH, where it comprised 17.2% of isolates (n = 11). The significant contribution of ST10 to the spread of resistance has been a very recent observation; previously it was reported in Spain (44), Italy (46), Egypt (34), and Canada (31).

Minor clones.

The 54 STs identified only in one center each (Table 2) encompassed 22.6% of the isolates (n = 84), with larger fractions in GI (40.6%) and BM (32.3%). Several clones in this group were locally significant, e.g., ST156 and ST393 in GI (12.5% and 9.4%, respectively) or ST372 and ST398 in TA (9.2% and 6.4%, respectively). A notable finding was 16 new STs, identified in each site, including the 5 aforementioned members of the ST10 and ST131 clonal complexes. The minor clones were an important source of the interhospital diversity, making, e.g., the E. coli population in GI relatively more specific than the E. coli populations in the others. Their position within the global MLST database varied; whereas the new STs were likely local clones, most of the minor STs had been found in other countries, and a number of them have spread globally or belonged to pandemic complexes. It is unclear why some of them, like the ST31 complex, were so scarcely observed. The ST31 complex (clonal group O15:K52:H1) is often associated with resistance (33, 47, 48) and was represented here only by three ST393 isolates in GI and one ST449 isolate in TA. It is easier to understand why just single isolates of ST73 (in FS) and ST95 (TA) were identified. These highly pathogenic clones have frequently been recovered from clinical samples but rarely, if at all, with ESBLs (29, 34, 49–51), which may explain their absence in the analyses targeted on ESBL-positive E. coli isolates (27, 31, 32, 44).

MLST versus PFGE.

All of the E. coli clones of wider occurrence and/or higher prevalence were split into multiple PFGE types in the entire population and often so in the local ones (Tables 1 and 2; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). ST131 isolates were diversified into 5 to 7 types in BM, GI, and TA, 13 types in LH, and 19 types in FS, with similarity rates between two patterns even falling below 60%. Some types formed bigger clusters in each hospital (>5% of isolates in a center), usually being ST131, e.g., PFGE types FSEcoJ in FS (n = 22; 20.4%) and TAEcoI in TA (n = 34; 24.1%). Among the other clones, larger clusters were observed for ST410 in LH (type LHEcoO, 9.4%), and ST372 and ST398 in TA (TAEcoQ, 8.5%, and TAEcoAS, 6.4%, respectively). The STs found in more than one hospital usually had different PFGE types in each center; only the two Israeli sites (LH and TA) shared closely related strains, including several types of ST131 (e.g., TAEcoI) and some types of STs: 38, 69, 405, and 648. In all these cases, isolates of the same PFGE type produced the same β-lactamase in both institutions (see below). The PFGE heterogeneity of ST131 and efficient spread of specific types have been observed previously, and it seems that while in general the diversity reflects the long-term evolution of the clone, the prevalent PFGE types may represent emerging subclones with even enhanced epidemic potential (31, 42, 52). Recently, Johnson et al. (35) have confirmed the earlier hypothesis that the increased virulence in combination with resistance is likely responsible for the ecological success of such variants (4, 6, 13), although on a smaller scale, similar observations could be made in this study for other clones with multiple PFGE types, like ST10, ST69, or ST648, in particular centers.

ESBLs and acquired AmpCs.

Overall, 94.7% of the E. coli isolates produced ESBLs (n = 356) and 5.6% produced acquired AmpCs (n = 21); one isolate had both an ESBL and AmpC. Considering that two isolates coexpressed two ESBLs, the total number of ESC-hydrolyzing β-lactamases was 379, including 358 ESBLs and 21 AmpCs (Table 3). The ESBLs belonged to the CTX-M (n = 303; 79.9%), SHV (n = 51; 13.5%), and TEM (n = 4; 1.1%) families, while the AmpCs were CMY-2-like enzymes (n = 20; 5.3%) and DHA-1 (n = 1; 0.3%). The prevalence of CTX-M enzymes was 66.7% in GI, 69.2% in LH, 77.3% in TA, 78.1% in BM, and 94.4% in FS. They represented four variant groups: CTX-M-1 (CTX-M-1, -3, -15, -32, and -55), CTX-M-2 (CTX-M-2), CTX-M-9 (CTX-M-9, -14, and -27), and CTX-M-25 (CTX-M-39 and -100). The CTX-M-1- and -9-like types were ubiquitous and prevalent (50.1% and 23.5%, respectively), while the CTX-M-25-like types were found only in Israel (7.1% in TA). SHVs (SHV-2, -2a, -5, and -12) were prevalent in GI (27.3%) and TA (17.7%), whereas TEMs (TEM-24 and -52) occurred only in BM (12.5%). The CMY-2-type AmpCs included three variants (CMY-2, -4, and -42). Only three β-lactamases, CTX-M-14, CTX-M-15, and CMY-2, were identified in each of the centers.

Table 3.

Geographic and quantitative distribution of β-lactamase variants in the study isolates

| β-Lactamase | CTX-M group | Center(s) | No. of isolates | % of enzymes | No. of clones |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-15 | 1 | BM, FS, GI, LH, TA | 154 | 40.6 | 29 |

| CTX-M-27a | 9 | GI, LH, TA | 42 | 11.1 | 3 |

| CTX-M-14b | 9 | BM, FS, GI, LH, TA | 39 | 10.3 | 16 |

| CTX-M-1 | 1 | BM, FS, LH | 30 | 7.9 | 26 |

| CTX-M-2 | 2 | FS, LH, TA | 13 | 3.4 | 8 |

| CTX-M-39 | 25 | TA | 10 | 2.6 | 3 |

| CTX-M-9 | 9 | BM, FS, LH, TA | 8 | 2.1 | 4 |

| CTX-M-32 | 1 | GI | 3 | 0.8 | 1 |

| CTX-M-55 | 1 | TA | 2 | 0.5 | 2 |

| CTX-M-3 | 1 | GI | 1 | 0.3 | 1 |

| CTX-M-100 | 25 | TA | 1 | 0.3 | 1 |

| SHV-12 | FS, GI, LH, TA | 33 | 8.7 | 14 | |

| SHV-5 | FS, TA | 16 | 4.2 | 5 | |

| SHV-2 | GI | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | |

| SHV-2a | FS | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | |

| TEM-24 | BM | 3 | 0.8 | 3 | |

| TEM-52 | BM | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | |

| CMY-2 | BM, FS, GI, LH, TA | 12 | 3.2 | 8 | |

| CMY-4 | LH, TA | 7 | 1.8 | 3 | |

| CMY-42 | LH | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | |

| DHA-1 | BM | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | |

| Total | 379c |

CTX-M-27 was encoded by the blaCTX-M-27a (n = 41) and blaCTX-M-27b (n = 1) genes.

CTX-M-14 was encoded by the blaCTX-M-14a (n = 36) and blaCTX-M-14b (n = 3) genes.

The total number is higher than 376 isolates because three isolates coproduced two different β-lactamases.

CTX-M-15 was produced by 154 isolates of 29 clones (40.6% of the enzymes) (Table 3). Its frequency varied from 12.1% in GI, 28.4% in TA, 46.2% in LH, and 46.9% in BM to 60.2% in FS. CTX-M-14 was present in 39 isolates of 16 clones (10.3%), being the main enzyme in GI (39.4%). CTX-M-27 and CTX-M-1 were observed in three centers each and were produced by 42 and 30 isolates, respectively (11.1% and 7.9% of all of the enzymes, respectively). CTX-M-27 was prevalent in TA (24.8%), but it was expressed only by three STs; in contrast, CTX-M-1, frequent in FS (23.1%), was produced by 26 clones. CTX-M-100 from a single isolate from TA was a new CTX-M-25-like variant and has separately been described in detail (53).

All these results reflected well the rapid dissemination of the CTX-M-type enzymes in the last decade, especially CTX-M-15 and -14 (11, 14). Local specificities, like the predominance of CTX-M-14 in GI, the spread of CTX-M-1 among E. coli clones in FS, and the presence of the CTX-M-25 types in LH and TA, had been observed in Spain, Italy, and Israel, respectively (28, 44, 54). The SHV enzymes have remained significant, but TEMs seemingly tend to disappear under CTX-M pressure, as reported elsewhere (23). They were identified only in France, where TEMs have evolved and extensively disseminated in the past (55).

Clones versus β-lactamases.

Of the widely identified clones (Table 1), ST131 alternatively produced 10 different β-lactamases, including 7 CTX-M variants of all groups, SHV-5, SHV-12, and CMY-4. The ST131 PFGE types were usually associated with one enzyme each, like the FSEcoJ with CTX-M-15 in FS or TAEcoI with CTX-M-27 in TA and LH. A few ST131 types expressed various β-lactamases, like TAEcoE in TA (n = 17; 12.1%), which produced CTX-M-14, CTX-M-15, CTX-M-55, or CMY-4, depending on the PFGE subtype. The most prevalent enzyme in ST131 was CTX-M-15 (58.7% of ST131 isolates), present in multiple PFGE types in each center; however, its frequency varied from 25.9% of ST131 isolates in TA (less than that of CTX-M-27) and 37.5% in GI (equal to that of SHV-12) to 90.9% in FS. The lack of a strict correlation between an ST and a β-lactamase was also observed for almost all other clones of wider distribution or higher prevalence, but isolates of a given PFGE type expressed the same enzyme. This was the case for the aforementioned larger PFGE clusters of ST410 in LH (SHV-12) or ST372 and ST398 in TA (SHV-5 and CTX-M-39, respectively). These results follow those of a number of other studies which demonstrated that the pandemic E. coli clones have basically been spreading by themselves, while the acquisition of locally prevalent plasmids with resistance genes stimulates their further dissemination (6, 13). The combination of ST131 traits with those provided by blaCTX-M-15-carrying plasmids has probably made such organisms better fit for further expansion (5, 10, 13, 35), and this association was observed in this work too. The remarkable exception was the Israeli center TA, where the spread of the PFGE type TAEcoI resulted in the predominance of CTX-M-27 in ST131 (∼59%), while the association was the strongest in FS in Rome, where the vast majority of ST131 isolates expressed CTX-M-15. These values are close to the extremes reported in earlier studies (13, 45).

Conclusions.

This study, being one of the largest E. coli population analyses conducted so far, showed a complex view of the epidemiology, with a number of similarities and differences between the clinical sites. The similar elements were the global clones, mainly ST131, and the predominant ESBL types, CTX-M-15 and -14. On the other hand, the local populations differed remarkably from each other; ∼50% of the STs identified in a center were usually not observed in the others. This diversity was apparent even in the two Tel-Aviv sites, which had only eight global clones in common. If one considers that only two clones (ST131 and ST393) in GI in Barcelona were found among ESBL producers from another hospital in this city in 2008 (43), the results show how different E. coli populations may exist in health care institutions of the same geographic area. The new data, especially those from Israel, suggest the possible emergence of several clonal variants that may appear to successfully spread in the future.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Karol Diestra for her excellent support and Ewa Sadowy for very helpful discussions.

This work was part of the activities of the MOSAR integrated project (LSHP-CT-2007-037941), supported by the European Commission under the Life Science Health priority of the 6th Framework Programme (WP5 and WP2 Study Teams). R.I., A.B., J.F, W.H., and M.G. were also financed by the MOSAR-complementary grant 934/6. Grant PR UE/2009/7 was from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Apart from the authors of this article, the MOSAR WP2 and WP5 Study Groups included A. Grabowska, M. Herda, and E. Nikonorow, National Medicines Institute, Warsaw, Poland; M. J. Schwaber, E. Bilavsky, M. Elenbogen, A. Klein, S. Navon-Venezia, M. Shklyar, L. Keren, R. Glick, S. Klarfeld-Lidji, E. Mordechai, S. Cohen, R. Fachima, Y. Zdonevsky, and B. Knubovets, Division of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel-Aviv, Israel; J. Lasley, I. Bertucci, M.-L. Delaby, C. Colmant, and C. Sacleux, Hôpital Maritime de Berck, Berck/Garches/Paris, France; R. Formisano, M. P. Balice, and E. Guaglianone, Fondazione Santa Lucia, IRCCS, Rome, Italy; S. Camps, Institute Guttmann, Barcelona, Spain; J. Hart, E. Isakov, A. Friedman, A. Rachman, G. Franco, and I. Or, Loewenstein Hospital, Ra'anana, Israel; and A. Rabinovich, Geriatric Division, Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel-Aviv, Israel.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 31 October 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01656-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rozenberg-Arska M, Visser MR. 2004. Enterobacteriaceae, p 2189–2202 In Cohen J, Powderly WG. (ed), Infectious diseases, vol 2 Mosby, St. Louis, MO [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bradford PA. 2001. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:933–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jacoby GA. 2009. AmpC beta-lactamases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 22:161–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pitout JD, Laupland KB. 2008. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: an emerging public-health concern. Lancet Infect. Dis. 8:159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carattoli A. 2009. Resistance plasmid families in Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2227–2238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Woodford N, Turton JF, Livermore DM. 2011. Multiresistant Gram-negative bacteria: the role of high-risk clones in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35:736–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wirth T, Falush D, Lan R, Colles F, Mensa P, Wieler LH, Karch H, Reeves PR, Maiden MC, Ochman H, Achtman M. 2006. Sex and virulence in Escherichia coli: an evolutionary perspective. Mol. Microbiol. 60:1136–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Selander RK, Caugant DA, Whittam TS. 1987. Genetic structure and variation in natural populations of Escherichia coli, p 1625–1648 In Neidhardt FC, Ingraham JL, Low KB, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger HE. (ed), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oteo J, Perez-Vazquez M, Campos J. 2010. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Escherichia coli: changing epidemiology and clinical impact. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 23:320–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coque TM, Novais A, Carattoli A, Poirel L, Pitout J, Peixe L, Baquero F, Canton R, Nordmann P. 2008. Dissemination of clonally related Escherichia coli strains expressing extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTX-M-15. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:195–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Livermore DM, Canton R, Gniadkowski M, Nordmann P, Rossolini GM, Arlet G, Ayala J, Coque TM, Kern-Zdanowicz I, Luzzaro F, Poirel L, Woodford N. 2007. CTX-M: changing the face of ESBLs in Europe. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59:165–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Blanco J, Leflon-Guibout V, Demarty R, Alonso MP, Canica MM, Park YJ, Lavigne JP, Pitout J, Johnson JR. 2008. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:273–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rogers BA, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL. 2011. Escherichia coli O25b-ST131: a pandemic, multiresistant, community-associated strain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rossolini GM, D'Andrea MM, Mugnaioli C. 2008. The spread of CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14(Suppl 1):33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Drieux L, Brossier F, Sougakoff W, Jarlier V. 2008. Phenotypic detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamase production in Enterobacteriaceae: review and bench guide. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14(Suppl 1):90–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perez-Perez FJ, Hanson ND. 2002. Detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase genes in clinical isolates by using multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2153–2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Adler A, Gniadkowski M, Baraniak A, Izdebski R, Fiett J, Hryniewicz W, Malhotra-Kumar S, Goossens H, Lammens C, Lerman Y, Kazma M, Kotlovsky T, Carmeli Y. Transmission dynamics of ESBL-producing E. coli clones in rehabilitation wards at a tertiary care center. Clin. Microbiol. Infect., in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Struelens MJ, Rost F, Deplano A, Maas A, Schwam V, Serruys E, Cremer M. 1993. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia after biliary endoscopy: an outbreak investigation using DNA macrorestriction analysis. Am. J. Med. 95:489–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, Swaminathan B. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grundmann H, Hori S, Tanner G. 2001. Determining confidence intervals when measuring genetic diversity and the discriminatory abilities of typing methods for microorganisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4190–4192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Bingen E. 2000. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4555–4558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bauernfeind A, Grimm H, Schweighart S. 1990. A new plasmidic cefotaximase in a clinical isolate of Escherichia coli. Infection 18:294–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Empel J, Baraniak A, Literacka E, Mrowka A, Fiett J, Sadowy E, Hryniewicz W, Gniadkowski M. 2008. Molecular survey of β-lactamases conferring resistance to newer β-lactams in Enterobacteriaceae isolates from Polish hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2449–2454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Empel J, Hrabak J, Kozinska A, Bergerova T, Urbaskova P, Kern-Zdanowicz I, Gniadkowski M. 2010. DHA-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a teaching hospital in the Czech Republic. Microb. Drug Resist. 16:291–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Literacka E, Empel J, Baraniak A, Sadowy E, Hryniewicz W, Gniadkowski M. 2004. Four variants of the Citrobacter freundii AmpC-type cephalosporinases, including novel enzymes CMY-14 and CMY-15, in a Proteus mirabilis clone widespread in Poland. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4136–4143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Woodford N, Fagan EJ, Ellington MJ. 2006. Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:154–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ben Sallem R, Ben Slama K, Estepa V, Jouini A, Gharsa H, Klibi N, Saenz Y, Ruiz-Larrea F, Boudabous A, Torres C. 2012. Prevalence and characterisation of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli isolates in healthy volunteers in Tunisia. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31:1511–1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mugnaioli C, Luzzaro F, De Luca F, Brigante G, Perilli M, Amicosante G, Stefani S, Toniolo A, Rossolini GM. 2006. CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Italy: molecular epidemiology of an emerging countrywide problem. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2700–2706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gibreel TM, Dodgson AR, Cheesbrough J, Fox AJ, Bolton FJ, Upton M. 2012. Population structure, virulence potential and antibiotic susceptibility of uropathogenic Escherichia coli from northwest England. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:346–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leflon-Guibout V, Blanco J, Amaqdouf K, Mora A, Guize L, Nicolas-Chanoine MH. 2008. Absence of CTX-M enzymes but high prevalence of clones, including clone ST131, among fecal Escherichia coli isolates from healthy subjects living in the area of Paris, France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3900–3905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peirano G, van der Bij AK, Gregson DB, Pitout JD. 2012. Molecular epidemiology over an 11-year period (2000 to 2010) of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli causing bacteremia in a centralized Canadian region. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:294–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van der Bij AK, Peirano G, Goessens WH, van der Vorm ER, van Westreenen M, Pitout JD. 2011. Clinical and molecular characteristics of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli causing bacteremia in the Rotterdam area, Netherlands. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:3576–3578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Blanco J, Mora A, Mamani R, Lopez C, Blanco M, Dahbi G, Herrera A, Blanco JE, Alonso MP, Garcia-Garrote F, Chaves F, Orellana MA, Martinez-Martinez L, Calvo J, Prats G, Larrosa MN, Gonzalez-Lopez JJ, Lopez-Cerero L, Rodriguez-Bano J, Pascual A. 2011. National survey of Escherichia coli causing extraintestinal infections reveals the spread of drug-resistant clonal groups O25b:H4-B2-ST131, O15:H1-D-ST393 and CGA-D-ST69 with high virulence gene content in Spain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:2011–2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fam N, Leflon-Guibout V, Fouad S, Aboul-Fadl L, Marcon E, Desouky D, El-Defrawy I, Abou-Aitta A, Klena J, Nicolas-Chanoine MH. 2011. CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli clinical isolates in Cairo (Egypt), including isolates of clonal complex ST10 and clones ST131, ST73, and ST405 in both community and hospital settings. Microb. Drug Resist. 17:67–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Johnson JR, Urban C, Weissman SJ, Jorgensen JH, Lewis JS, II, Hansen G, Edelstein PH, Robicsek A, Cleary T, Adachi J, Paterson D, Quinn J, Hanson ND, Johnston BD, Clabots C, Kuskowski MA. 2012. Molecular epidemiological analysis of Escherichia coli sequence type ST131 (O25:H4) and blaCTX-M-15 among extended-spectrum- β-lactamase-producing E. coli from the United States, 2000 to 2009. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:2364–2370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Van der Bij AK, Peirano G, Pitondo-Silva A, Pitout JD. 2012. The presence of genes encoding for different virulence factors in clonally related Escherichia coli that produce CTX-Ms. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 72:297–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dimou V, Dhanji H, Pike R, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2012. Characterization of Enterobacteriaceae producing OXA-48-like carbapenemases in the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:1660–1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mushtaq S, Irfan S, Sarma JB, Doumith M, Pike R, Pitout J, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2011. Phylogenetic diversity of Escherichia coli strains producing NDM-type carbapenemases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:2002–2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Naas T, Cuzon G, Gaillot O, Courcol R, Nordmann P. 2011. When carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase KPC meets Escherichia coli ST131 in France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4933–4934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Peirano G, Asensi MD, Pitondo-Silva A, Pitout JD. 2011. Molecular characteristics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17:1039–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Clermont O, Dhanji H, Upton M, Gibreel T, Fox A, Boyd D, Mulvey MR, Nordmann P, Ruppe E, Sarthou JL, Frank T, Vimont S, Arlet G, Branger C, Woodford N, Denamur E. 2009. Rapid detection of the O25b-ST131 clone of Escherichia coli encompassing the CTX-M-15-producing strains. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:274–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lau SH, Kaufmann ME, Livermore DM, Woodford N, Willshaw GA, Cheasty T, Stamper K, Reddy S, Cheesbrough J, Bolton FJ, Fox AJ, Upton M. 2008. UK epidemic Escherichia coli strains A-E, with CTX-M-15 beta-lactamase, all belong to the international O25:H4-ST131 clone. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:1241–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Coelho A, Mora A, Mamani R, Lopez C, Gonzalez-Lopez JJ, Larrosa MN, Quintero-Zarate JN, Dahbi G, Herrera A, Blanco JE, Blanco M, Alonso MP, Prats G, Blanco J. 2011. Spread of Escherichia coli O25b:H4-B2-ST131 producing CTX-M-15 and SHV-12 with high virulence gene content in Barcelona (Spain). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Oteo J, Diestra K, Juan C, Bautista V, Novais A, Perez-Vazquez M, Moya B, Miro E, Coque TM, Oliver A, Canton R, Navarro F, Campos J. 2009. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Spain belong to a large variety of multilocus sequence typing types, including ST10 complex/A, ST23 complex/A and ST131/B2. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34:173–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cerquetti M, Giufre M, Garcia-Fernandez A, Accogli M, Fortini D, Luzzi I, Carattoli A. 2010. Ciprofloxacin-resistant, CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli ST131 clone in extraintestinal infections in Italy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:1555–1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Giufre M, Graziani C, Accogli M, Luzzi I, Busani L, Cerquetti M. 2012. Escherichia coli of human and avian origin: detection of clonal groups associated with fluoroquinolone and multidrug resistance in Italy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:860–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cagnacci S, Gualco L, Debbia E, Schito GC, Marchese A. 2008. European emergence of ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli clonal groups O25:H4-ST 131 and O15:K52:H1 causing community-acquired uncomplicated cystitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2605–2612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Johnson JR, Menard M, Johnston B, Kuskowski MA, Nichol K, Zhanel GG. 2009. Epidemic clonal groups of Escherichia coli as a cause of antimicrobial-resistant urinary tract infections in Canada, 2002 to 2004. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2733–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bert F, Johnson JR, Ouattara B, Leflon-Guibout V, Johnston B, Marcon E, Valla D, Moreau R, Nicolas-Chanoine MH. 2010. Genetic diversity and virulence profiles of Escherichia coli isolates causing spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and bacteremia in patients with cirrhosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:2709–2714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Suzuki S, Shibata N, Yamane K, Wachino J, Ito K, Arakawa Y. 2009. Change in the prevalence of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Japan by clonal spread. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63:72–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vincent C, Boerlin P, Daignault D, Dozois CM, Dutil L, Galanakis C, Reid-Smith RJ, Tellier PP, Tellis PA, Ziebell K, Manges AR. 2010. Food reservoir for Escherichia coli causing urinary tract infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:88–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Johnson JR, Nicolas-Chanoine MH, DebRoy C, Castanheira M, Robicsek A, Hansen G, Weissman S, Urban C, Platell J, Trott D, Zhanel G, Clabots C, Johnston BD, Kuskowski MA. 2012. Comparison of Escherichia coli ST131 pulsotypes, by epidemiologic traits, 1967-2009. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18:598–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vervoort J, Baraniak A, Gazin M, Lammens C, Kazma M, Grabowska A, Izdebski R, Carmeli Y, Gniadkowski M, Goossens H, Malhotra-Kumar S. 2012. Characterization of two new CTX-M-25-group extended-spectrum β-lactamase variants identified in Escherichia coli isolates from Israel. PLoS One 7:e46329 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Navon-Venezia S, Chmelnitsky I, Leavitt A, Carmeli Y. 2008. Dissemination of the CTX-M-25 family β-lactamases among Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli and Enterobacter cloacae and identification of the novel enzyme CTX-M-41 in Proteus mirabilis in Israel. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:289–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. De Champs C, Sirot D, Chanal C, Bonnet R, Sirot J. 2000. A 1998 survey of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae in France. The French Study Group. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3177–3179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.