Abstract

The subunit ε of bacterial F1FO ATP synthases plays an important regulatory role in coupling and catalysis via conformational transitions of its C-terminal domain. Here we present the first low-resolution solution structure of ε of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtε) F1FO ATP synthase and the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structure of its C-terminal segment (Mtε103–120). Mtε is significantly shorter (61.6 Å) than forms of the subunit in other bacteria, reflecting a shorter C-terminal sequence, proposed to be important in coupling processes via the catalytic β subunit. The C-terminal segment displays an α-helical structure and a highly positive surface charge due to the presence of arginine residues. Using NMR spectroscopy, fluorescence spectroscopy, and mutagenesis, we demonstrate that the new tuberculosis (TB) drug candidate TMC207, proposed to bind to the proton translocating c-ring, also binds to Mtε. A model for the interaction of TMC207 with both ε and the c-ring is presented, suggesting that TMC207 forms a wedge between the two rotating subunits by interacting with the residues W15 and F50 of ε and the c-ring, respectively. T19 and R37 of ε provide the necessary polar interactions with the drug molecule. This new model of the mechanism of TMC207 provides the basis for the design of new drugs targeting the F1FO ATP synthase in M. tuberculosis.

INTRODUCTION

With one-third of humankind infected subclinically, an incidence of nine million new cases of active tuberculosis disease (TB), and two million deaths per year, Mycobacterium tuberculosis remains the most important bacterial pathogen in the world (1). The increased prevalence of coinfections with HIV and the infection with multidrug-resistant as well as extensively drug-resistant mycobacterial strains are contributing to the worsening impact of this disease (2). New drugs for TB, which should have a new mechanism of action to be active against drug-resistant TB, are urgently needed. Furthermore, they should be active against the dormant form of the pathogen to enable shortening of the lengthy regimens currently in use (3). TMC207, the first member of a promising new class of antimycobacterial drugs, the diarylquinolines, is in early clinical development (4). The compound is active against drug-resistant M. tuberculosis and—importantly—also bactericidal for the phenotypically drug-resistant dormant form of the bacillus (5). TMC207 was identified in a phenotypic whole-cell screen. Target deconvolution studies revealed that the candidate interferes with the enzyme machinery responsible for the synthesis of the biological fuel ATP (5–7). Chemical inhibition of ATP synthesis by diarylquinoline strongly decreased the cellular ATP level, leading to death in not only replicating but also nonreplicating persistent mycobacteria (5, 6). The diarylquinoline TMC207 represents the first pharmacological proof that mycobacterial ATP synthesis can be a target of intervention (8). Furthermore, it demonstrates that ATP synthase is essential for the viability of growing as well as nongrowing dormant mycobacteria. These findings were additionally supported by physiological studies of a deletion mutant of atpD, encoding the β subunit of F1Fo ATP synthase in M. smegmatis (9). Critically, the excellent efficacy of TMC207 in a proof-of-concept study validates this target clinically. Of note, the drug displays pronounced target selectivity, with an extremely low effect on ATP synthesis in the human enzyme (10).

The target of TMC207, the mycobacterial F1FO ATP synthase (5), consists of the ATP-synthesizing F1 and the proton-translocating FO part (subunits a1b2c9-15 [11]). The proton transfer in the FO sector is linked via the central stalk subunits γ and ε to the α3β3-catalytic hexamer of F1 (11, 12). This coupling event is achieved by binding of the N-terminal domain of ε to the rotating subunit γ and the c-ring (Fig. 1A), as well as the interactions of the C termini of both ε and γ with the nucleotide-binding subunits α and β, which form the catalytic interfaces (12, 13).

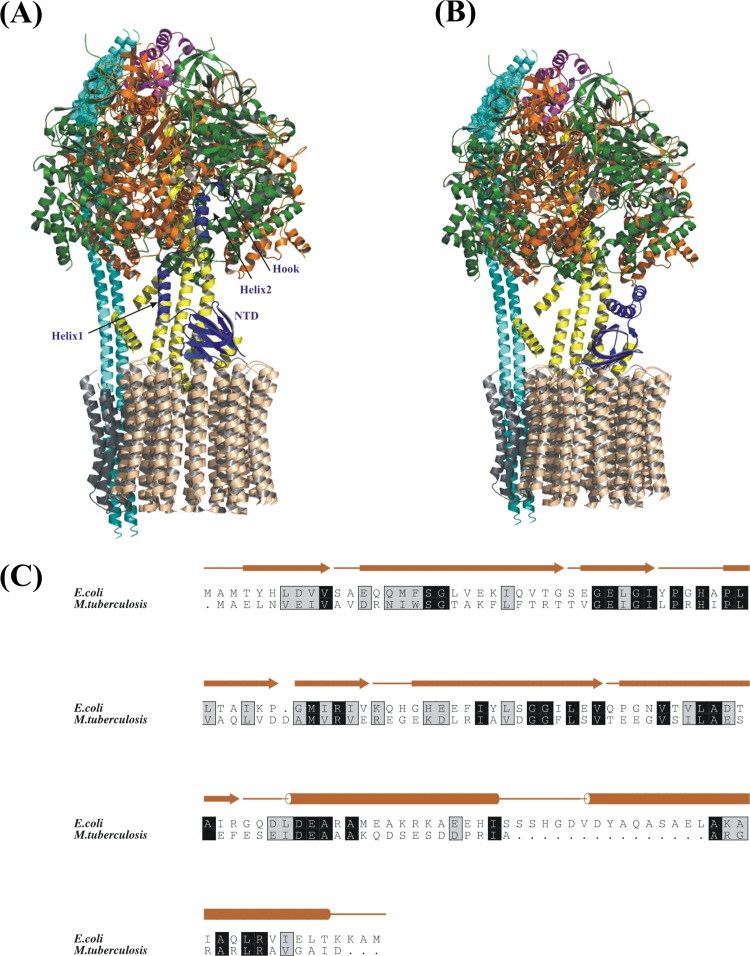

Fig 1.

Proposed model of the E. coli F1FO ATP synthase enzyme complex. The structures of α (green), β (orange), and γ (yellow) subunits (Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID: 1D8S), the ε subunit (blue) (PDB ID: 1BSN), the N-terminal domain (NTD) of the δ1–134 subunit (magenta) (PDB ID: 1ABV), the model of the c-ring (brown) with subunit a (gray) (PDB ID: 1C17), and the subunit b dimer model (cyan) were fitted. The subunit b model was created by fitting the NMR solution structures of b1–34 (45), b30–82 (PDB ID: 2KHK), and b140–156 (46) and the crystallographic structure of b62–122 (PDB ID: 1L2P). The mesh in subunit b indicates the region for which the structure is not known. Model with ECε in the extended (A) (17) and compact (B) conformations are shown. The N-terminal domain (NTD), helix 1, helix 2, and hook regions are indicated for ECε. (C) Amino acid sequence alignment of ECε and Mtε. The secondary structure of ECε is based on the NMR solution structure determined by Wilkens and Capaldi (15).

In bacteria and plants, subunit ε consists of an N-terminal β-barrel and a C-terminal segment, composed of two α-helices (14–16). As shown in the isolated (15) as well as in the F1-bound (17) complex, these two C-terminal α-helices can either be folded in a hairpin form and sitting on top of the N-terminal domain (NTD) (Fig. 1A and B), called the compact state (εc), or extended (εe [17]). In such an extended state, ε interacts with the same five subunits, α1, α2, β1, β3, and γ, as the inhibitor protein of the mitochondrial F1FO ATP synthase (18), causing enzymatic inhibition. The εc and εe states are described to be dependent on nucleotide binding to the C-terminal helices of ε (16, 19) and the membrane potential (20). For some bacteria the εc state can be stabilized by binding of ATP, thus favoring active complexes when cellular ATP is abundant (21).

Functional ATP synthase is critical for the viability of pathogenic bacteria such as M. tuberculosis. Based on the physiological role of ε regulation in the ATP synthase, which is connected to the C-terminal segment of this subunit, bacteria show variations in length and composition of the amino acid sequence of this C terminus. This is also revealed by the shorter C-terminal region of the M. tuberculosis ε compared to the Escherichia coli form (Fig. 1C), described to be responsible for enzymatic activity (17), coupling (12), and modulation of nucleotide specificity in the catalytic sites (21).

So far no structural details are available for mycobacterial F1FO ATP synthase, its subunits, or the interaction site of the TB drug TMC207 inside the enzyme. In this study, we have employed a complementary approach of solution X-ray scattering and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to determine the solution structures of M. tuberculosis subunit ε and its C-terminal domain, respectively. Importantly, we describe for the first time that TMC207 does interact with the N-terminal domain of ε. We propose a new model, in which TMC207 binds like a wedge in the interface of ε and subunit c and blocks the rotary mechanism of the c-ring with the central stalk subunits of F1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production and purification of Mtε and its mutant proteins Mtε-T19A and Mtε-R37G.

The gene atpC, which codes for subunit ε of the F1FO ATP synthase from the strain M. tuberculosis H37Rv, was amplified by PCR in two steps. Restriction sites NcoI and SacI, which were used for cloning, were introduced by the following PCR primers: Forward atpC, 5′-GAGTTGTCCCATGGCCGAATTGAAC-3′; Reverse atpC, 5′-TCATCGAGCTCTTAGTCAATCGCGC-3′. In order to abolish restriction site NcoI, which is present in an atpC DNA sequence, the following pair of internal primers introducing a silent mutation was constructed: IF-NcoI, 5′-GATGACGCAATGGTGCGGGTC-3′; IR-NcoI, 5′-GACCCGCACCATTGCGTCATC-3′. In the first step, PCR products were obtained in two independent reaction mixtures containing the primer pairs Forward atpC–IR-NcoI and IF-NcoI–Reverse atpC. The genomic DNA from the strain M. tuberculosis HR37v was used as the template. In the second PCR step, these products were used together as a template in a final reaction using primer pair Forward atpC–Reverse atpC. The mutated atpC genes coding for Mtε-R37G and -T19A were obtained by PCR in vitro mutagenesis using cloned gene atpC as a template and the internal primer pairs IF-R37G (5′-CATCCTGCCAGGACACATTCCGT-3′)–IR-R37G (5′-ACGGAATGTGTCCTGGCAGGATG-3′) and IF-T19A (5′-CATCTGGTCGGGTGCAGCGAAGT-3′)–IR-T19A (5′-ACTTCGCTGCACCCGACCAGATG-3′), respectively.

The purified PCR products were digested with restriction enzymes NcoI and SacI and ligated into the vector pET9d1 (22). The DNA constructs were transformed into Escherichia coli cells [strain BL21(DE3)] and grown on kanamycin-containing Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates. To express the cloned genes, liquid culture was shaken in LB medium containing kanamycin (30 μg ml−1) for about 4 h at 37°C until an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6 to 0.7 was reached, and then expression was induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM. The cells were lysed on ice by sonication in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 4 mM Pefabloc SC [BIOMOL]). The precipitated material was separated by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 35 min. The supernatant was passed over a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin column to isolate Mtε. The His-tagged protein was allowed to bind to the matrix for 1.5 h at 4°C and eluted with an imidazole gradient (50 to 400 mM) in buffer A. Fractions containing Mtε or the mutant ε-R37G were identified by SDS-PAGE, collected, and diluted to a final concentration of 100 mM NaCl. Filtered samples (0.45-μm pore size; Millipore) containing ε or its mutant protein were applied to anion-exchange Resource Q chromatography, which was previously equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.5. Whereas monomeric Mtε does not bind to the column matrix, the oligomeric forms of ε together with impurities bind to the column. Eluted Mtε was concentrated by using Centricon YM-3 (3-kDa molecular mass cutoff) spin concentrators (Millipore), and aliquots of 1 ml were subjected to gel filtration chromatography using a Superdex 75 HR 10/30 column (Amersham Biosciences), which was previously equilibrated with a buffer of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol. The fractions containing subunit ε and the mutant proteins ε-T19A and ε-R37G were collected and concentrated to the required concentrations.

Peptide synthesis of ε103–120.

The peptide ε103–120 from M. tuberculosis (strain H37RV), composed of the amino acid sequence 103DPRIAARGRARLRAVGAI120, was synthesized and purified by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography at the Division of Chemical Biology and Biotechnology, School of Biological Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. The purity of the peptide was confirmed by electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry.

CD spectroscopy of Mtε and mutant proteins Mtε-T19A and Mtε-R37G as well as Mtε103–120.

Steady-state CD spectra were measured in far-UV light (185 to 260 nm) using a Chirascan spectropolarimeter (Applied Photophysics) as described previously (23). Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy of Mtε, Mtε-T19A, and Mtε-R37G (1.0 mg/ml) and the peptide ε103–120 (2.0 mg/ml) was performed in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol) and buffer B (25 mM phosphate, pH 6.5, 50% TFE [4-chlorobutanol and 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol]), respectively. The spectrum for the buffer was subtracted from the spectrum of the protein, and the data were analyzed as described recently (24).

X-ray scattering experiments and data analysis of subunit ε.

Small-angle X-ray scattering data for Mtε were collected on the X33 SAXS camera of the EMBL Hamburg located on a bending magnet (sector D) on the storage ring DORIS III of the Deutsches Elektronen Synchrotron (25) The scattering patterns from Mtε were measured at protein concentrations of 3.0 and 6.0 mg/ml. Protein samples were prepared in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol as a radical quencher. The data were normalized to the intensity of the incident beam; the scattering of the buffer was subtracted, and the difference curves were scaled for concentration. All the data processing steps were performed using the program package PRIMUS (26). The forward scattering, I(0), and the radius of gyration, Rg, were evaluated using the Guinier approximation (27). The molecular mass of Mtε was calculated by comparison with the forward scattering from the reference solution of bovine serum albumin (BSA). From this procedure a relative calibration factor for the molecular mass can be calculated using the known molecular mass of BSA (66 kDa) and the concentration of the reference solution. The shape of subunit ε in solution was built by the program GASBOR (28, 29). Ab initio shape models for subunit ε were obtained by superposition of 10 independent GASBOR reconstructions.

NMR spectroscopy of Mtε103–120.

Peptide ε103–120 (2 mM) was dissolved in 25 mM phosphate buffer at pH 6.5 and 50% d2TFE (deuterated 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol). All spectra were obtained at 298 K on a 600-MHz Avance Bruker NMR spectrometer, equipped with actively shielded cryo-probe and pulse field gradients. Total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) and nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) spectra of the peptide were recorded with mixing times of 80 and 250 ms, respectively. DSS (2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate sodium salt) was used as an internal reference. All the data acquisition and processing were done by the TopSpin (Bruker Biospin) program. The Sparky suite was used for spectrum visualization and peak picking. Standard procedures based on spin-system identification and sequential assignment were adopted to identify the resonances. Interproton distances were obtained from the NOESY spectra by using the caliba script included in the CYANA 2.1 package (30). Dihedral angle restraints were derived from TALOS. The predicted dihedral angle constraints were used for structure calculation, with a variation of ±30° from the average values. The CYANA 2.1 package was used to generate the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the peptide. Several rounds of structural calculation were performed. Angle and distance constraints were adjusted until no NOE violations occurred. In total, 100 structures were calculated and an ensemble of 20 structures with lowest total energy was chosen for structural analysis.

Titration of Mtε against drugs through NMR spectroscopy.

To analyze possible interactions of Mtε with drugs (TMC207 or mefloquine/HCl), a series of 1H-15N HSQC (hetero-nuclear single quantum coherence) spectra were recorded at 303 K for a fixed concentration of Mtε (250 μM) and with increasing concentrations of the drugs, respectively (up to 2.0 equivalents). Mtε was prepared in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.5) buffer containing 200 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol. The protein was incubated for 30 min with the drug at each level of concentration. Any changes in the chemical shift were monitored on the HSQC spectra.

Tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy of Mtε, Mtε-T19A, and Mtε-R37G in the presence of the antibiotic TMC207.

A Varian Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer was used, and all experiments were carried out at 20°C. The samples were excited at 295 nm, and the emission spectrum was recorded from 310 to 430 nm with excitation and emission band-passes set to 5 nm and a scan rate of 30 nm/min. For titration of the tryptophan fluorescence of Mtε as well as the mutant proteins Mtε-T19A and Mtε-R37G with compound TMC207, the peak emission wavelength was 339 nm. Before use, subunit ε or the mutant forms Mtε-T19A and Mtε-R37G and defined concentrations of compound TMC207 were incubated in a buffer of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 200 mM NaCl, 18% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and 10% glycerol for 20 min. After measurements, the raw fluorescence spectra were corrected for the buffer values.

Isothermal titration calorimetry of Mtε and nucleotides.

The binding affinities of Mtε toward nucleotides ATP or ADP was examined by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) in a MicroCal iTC200 microcalorimeter (MicroCal, Northampton, United Kingdom). Both the protein and the nucleotides were equilibrated in the same buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, pH 8.5), filtered, and degassed before titration. The solution, containing either 1 mM ATP or 1 mM ADP and 1 mM Mg2+, was titrated in 1-μl injections against 10 μM protein solution, which was loaded in the sample cell. The experiment was performed as described recently (31). The control experiment was done under the same experimental conditions using 10 μM protein of subunit A from the archaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3 in buffer, composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5. Data analysis was done as described recently (31).

Protein structure accession number.

The Protein Data Bank accession code of the peptide Mtε103–120 is 2LX5.

RESULTS

Purification of recombinant subunit ε and its secondary structural content.

Recombinant subunit ε of the M. tuberculosis H37Rv F1FO ATP synthase was isolated to high quality and quantity using Ni-NTA-affinity, ion, and size exclusion chromatography (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). The molecular mass of the recombinant protein was analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry, revealing that the protein has a sequence-based predicted mass of 15.19 kDa. The proper secondary folding of the recombinant Mtε was studied by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, resulting in a secondary structural content of 21% α-helix and 58% β-sheet (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). In order to prove whether the recombinant protein is able to bind to the α3β3γ complex, fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) experiments were performed and are described in the supplemental material. The autocorrelation curves of the fluorescently labeled Mtε with increased concentrations of α3β3γ of the related thermophilic F1FO ATP synthase from Bacillus PS3 (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material) and the resulting concentration-dependent binding curve are shown in the supplemental material (see Fig. S2B). The increase of the mean diffusion time, τD, reflects the increase in the mass of the diffusing particle, due to the formation of the Atto488-e-α3β3γ complex. A binding constant of 4.0 μM was determined by nonlinear curve fit by the Hill equation.

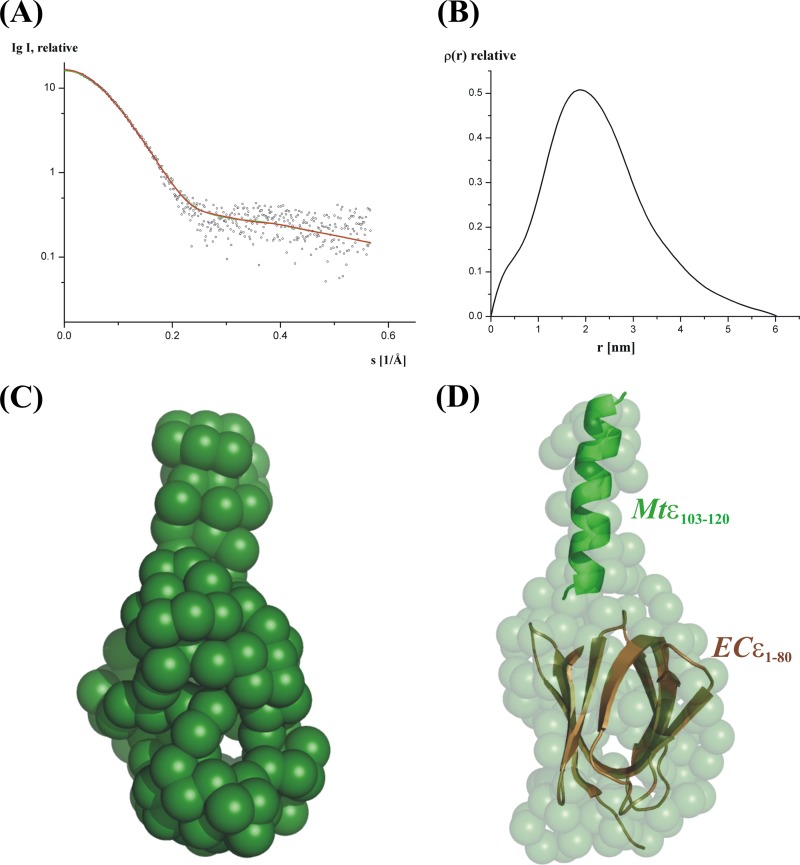

Low-resolution structure of Mtε in solution.

The high purity and mono-dispersity of the protein are nicely indicated by small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) data, represented by the final composite scattering curve in Fig. 2A. The radius of gyration, Rg, and the maximum dimension, Dmax, of subunit ε were 17.6 ± 0.3 Å and 61.7 ± 1 Å, respectively (Fig. 2B). Comparison with the scattering from the reference solutions of BSA yields an estimated molecular mass of 15.7 kDa. The gross structure of Mtε was restored ab initio from the scattering pattern in Fig. 2A using the dummy residues modeling program GASBOR (26), which fitted well to the experimental data in the entire scattering range (a typical fit displayed in Fig. 2A, red curve, has the discrepancy χ2 = 1.17). Ten independent reconstructions yielded reproducible models, and the best model is displayed in Fig. 2C. Qualitative analysis of the distance distribution function suggests that subunit ε consists of a major portion, yielding a principal maximum in the p(r) around 20 Å (Fig. 2B), whereas the separated protuberance domain gives rise to a shoulder from 42 Å to 61.7 Å. The protein appears as a two-domain molecule with a large major domain of about 39 by 27 Å, whereby the elongated domain has a dimension of about 20 by 11 Å. The gross structure of the globular domain resembles very much the shape of the N-terminal domain of the solution NMR structure of the homolog ε subunit of the E. coli F1FO ATP synthase, and this N-terminal barrel of ECε is well accommodated within the globular domain of Mtε (Fig. 2D). In contrast, the elongated domain (20 Å) of Mtε is shorter than that of the ECε subunit (30 Å [32]), reflecting the loss of 15 amino acids in the C terminus of Mtε (Fig. 1C).

Fig 2.

Small-angle X-ray scattering data of Mtε. (A and B) Experimental scattering curves (A) and distance distribution functions (B) of Mtε. (C) Low-resolution structures of Mtε. (D) Superimposition of the low-resolution solution structure of Mtε with the N-terminal β-barrel structure of ECε (37) (brown) and the Mtε103–120 (green) peptide structure.

Solution structure of the C-terminal segment ε103–120.

To get a deeper insight into the very C-terminal region of M. tuberculosis subunit ε, the C-terminal segment 103DPRIAARGRARLRAVGAI120 was synthesized and the CD spectrum shows an α-helical content of 87% (see Fig. S3A in the supplemental material). In order to determine the 3D structure of Mtε103–120, the primary sequences of ε103–120 were sequentially assigned as per the standard procedure by using a combination of TOCSY and NOESY spectra (see Fig. S3B and C in the supplemental material). Secondary structure prediction was done by using the PREDITOR online program (33), which uses HA chemical shifts and reveals the presence of an α-helical structure (see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material). Out of 100 structures generated, the 20 lowest-energy structures were taken for further analysis. In total, an ensemble of 20 calculated structures resulted in an overall mean root square deviation (RMSD) of 0.20 Å for the backbone atoms and 1.09 Å for the heavy atoms (Fig. 3A). All these structures have energies lower than −100 kcal mol−1, with no NOE violations and no dihedral violations. The summary of the statistics for 20 structures are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Identified cross peaks in the HN-HN and HA-NH regions are shown in Fig. S4B in the supplemental material. From the assigned NOESY spectrum HN-HN, Hα-HN (i, i + 3), Hα-HN (i, i + 4), and Hα-Hβ (i, i + 3) connectivities were plotted and support α-helical formation in the structure. The calculated structure has a total length of 27.46 Å and displays an α-helical region between residues 104 and 119 (23.31 Å; Fig. 3B). Molecular surface electrostatic potential of the peptide is shown in Fig. 3C, where positive charge residues R109 and R113 were distributed on one side and R111 as well as R115 on the opposite side of the helix. The solution structure of ε103–120 was positioned inside the elongated domain of the solution shape of Mtε. As revealed in Fig. 2D, Mtε103–120 fits well into the extended domain, with an RMSD of 0.29 Å.

Fig 3.

NMR studies of the peptide Mtε103–120.(A) Superimposition of the 20 lowest-energy NMR structures of Mtε103–120 in line representation. (B) Average NMR structures of Mtε103–120 in cartoon representation. (C) Molecular surface electrostatic potential of peptide Mtε103–120 generated by Pymol, where the positive potentials are drawn in blue and the negative in red.

Probing the interaction of nucleotides with Mtε.

In bacteria and in chloroplasts the C terminus of ε is described as a mobile regulatory element that alters its conformation in response to nucleotide conditions or the ion motive force (IMF) (2, 20). ATP binding in ε of thermophilic Bacillus PS3 and Bacillus subtilis forces the C-terminal helices into a hairpin conformation, which extends in the absence of the nucleotide, leading to an inhibited ATP hydrolysis state (19). Here we performed isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to investigate whether the M. tuberculosis subunit ε also binds nucleotides. As demonstrated in the injection profile of Mtε (see Fig. S5A and C in the supplemental material) after baseline correction (top panel) with the profile of heat release/mole of injected ligand (bottom panel), the subunit binds neither ATP nor ADP. As shown by a control experiment under the same conditions, subunit A of the Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3 A1AO ATP synthase binds MgATP and MgADP with Kd values of 3 μM and 2.1 μM, respectively (see Fig. S5B and D in the supplemental material), which is in good agreement with previous results (31).

The drug TMC207 interacts with Mtε.

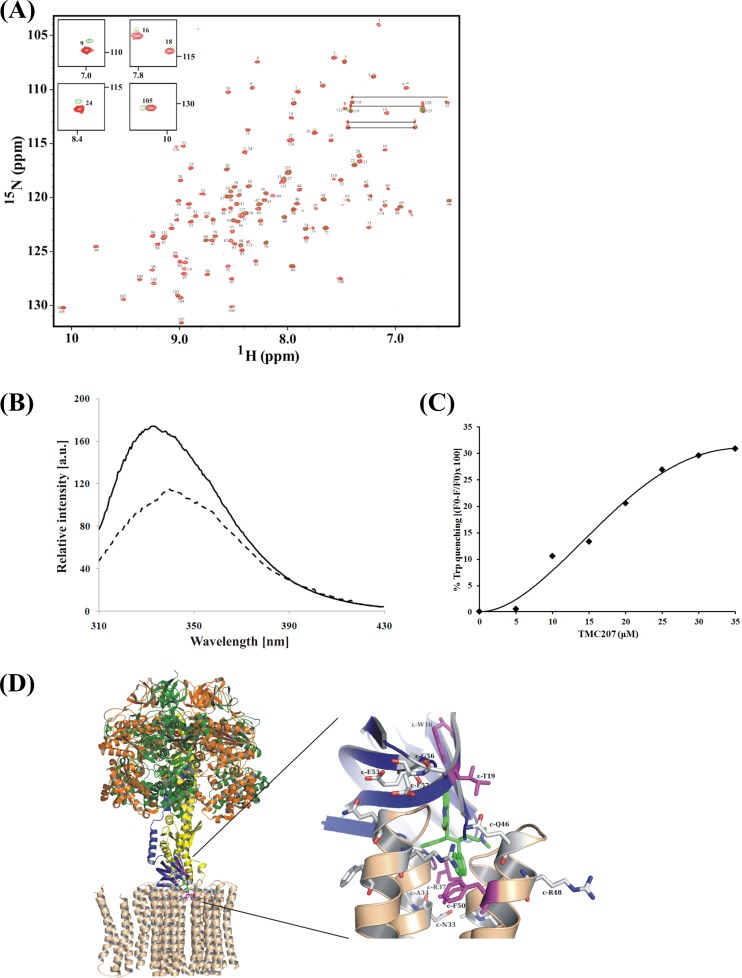

In all types of F1FO ATP synthases the N-terminal domain of ε binds to the rotating subunit γ and directly couples to the c-ring of the membrane-embedded FO-sector (12). The TB drug candidate TMC207 has been proposed to bind to subunit c by acting independently of the proton motive force and would not compete with protons for a common binding site, indicating that TMC207 may interfere with conformational changes in the entire enzyme, like the rotation of the c-ring (34). Based on these suggestions and the direct coupling of both the c-ring and subunit ε in the rotary events, we asked whether TMC207 may interact also with M. tuberculosis subunit ε. In order to demonstrate ε-TMC207 binding, NMR titration experiments were performed. 15N-labeled protein was used to acquire the HSQC spectrum of Mtε. The HSQC spectrum showed a good dispersion of around 4 ppm at 303 K, with acquisition giving a total of 126 peaks (Fig. 4A). When the 15N-labeled Mtε was titrated against increasing concentration of TMC207, seven peaks showed distortion at a molar ratio of 1:1. These peaks, namely 5, 9, 15, 16, 18, 24, and 105 (Fig. 4A), showed further dislocation on the spectrum upon titration against a 1:2 molar ratio and some peaks disappeared, giving an indication of the drug binding to ε. The predominant peaks, showing more distortions, are shown on the top left corner of the spectrum as an insert in Fig. 4A. Peak number 105, which appears at 10 ppm, can be identified as the tryptophan residue W15, based on the chemical shift index (35). Changes in this resonance of the W15 peak upon the addition of TMC207 indicate its significant interaction. On the other hand, no peak distortion was observed when Mtε was titrated against the mefloquine hydrochloride at a molar ratio of 1:2 (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material), reflecting the specific interaction of TMC207 with M. tuberculosis ε. Mefloquine was used in the experiment, as it has been shown to target the FO complex of the F1FO ATP synthase of Streptococcus pneumoniae (36).

Fig 4.

Spectroscopic titration studies of Mtε with TMC207. (A) 2D 1H-15N-HSQC spectra of Mtε in the absence (red) and presence (green) of 2 equivalents of drug (TMC207). The HSQC spectra were acquired at 303 K with 250 μM protein dissolved in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.5) buffer containing 200 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol. The peaks showing chemical shift change upon addition of the drug are shown in the respective insets. (B) Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence titration of Mtε in the absence (solid line) and presence (broken line) of TMC207. Excitation was at 295 nm. (C) Fluorescence titration of Mtε with TMC207. Excitation was at 295 nm, and the emission was measured at 339 nm. (D) Model of the ECF1 ATPase structure (17) with the c-ring (PDB ID: 1C17) and part of subunit a (PDB ID: 1C17) (left) and a plausible model showing the interaction of TMC207 (green) with the ε subunit (blue) and c-ring (beige) (right). The model shows the nonhomologous residues between Mtε and E. coli ε and c subunits, changed to M. tuberculosis residues, shown in gray and magenta stick representation. The crucial residues that might interact with the TMC207 molecule are shown in magenta stick representation for Mtε and the c-ring. The TMC207 molecule is proposed to interact with W15 of Mt ε and F50 of the c-ring.

Since the NMR titration experiment of Mtε with TMC207 has shown that the only tryptophan residue (W15) of ε undergoes a shift in the HSQC spectra after addition of the compound, we used intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy to confirm and to quantitatively evaluate the binding of TMC207 to Mtε. The corrected tryptophan fluorescence spectrum of Mtε reveals the emission maximum at 339 nm (Fig. 4B). The intensity dropped by 34% and the maximum of the peak shifted to a longer wavelength, indicating an alteration in the close proximity of W15 after addition of TMC207. To quantitate the spectra, the binding of TMC207 to ε was measured using fluorescence quenching at 339 nm. As shown in the titration curve of Fig. 4C, a binding constant of 19.1 μM could be determined.

A plausible model for the interaction of the TMC207 molecule with both ε and the c-ring was generated (Fig. 4D). The crucial residues, which are on the interface between ε and the c-ring, were identified in the E. coli structure and were changed to their respective residues in the M. tuberculosis sequence, after which the TMC207 molecule was modeled in the interface of ε and the c-ring (Fig. 4D, right). The model shows that the TMC207 molecule forms a wedge between the two subunits by interacting with the residues W15 and F50 of ε and the c-ring, respectively. Two other residues, T19 and R37 of ε, which are within 5 Å of the TMC207 molecule and are shown in the presented data to be important in TMC207-ε binding (see below), might give the necessary polar interaction to the drug molecule.

To confirm the binding model, residues T19 and R37 of Mtε were replaced by alanine and glycine residues, respectively, which were allocated in the corresponding positions of ECε (Fig. 1C). Tryptophan titrations of the R37G mutant proteins revealed that a significant drop and shift of the tryptophan spectrum could be achieved only at a concentration of 48 μM TMC207, which was identical for the Mtε-T19A mutant form (not shown). These data indicate that binding of TMC207 to MtεT19A or MtεR37G is strongly affected by these mutations and support the importance of the residues T19 and R37 in TMC207 binding (see Fig. S1D in the supplemental material).

DISCUSSION

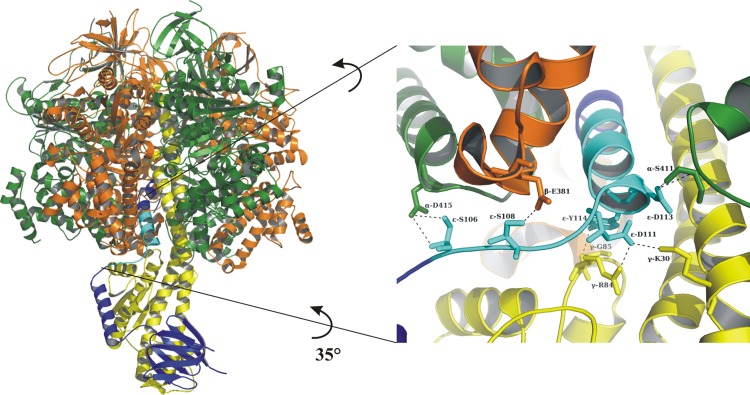

The presented NMR structure of the M. tuberculosis C-terminal ε103–120 shows an α-helical stretch between the residues P104 and A119. When superimposed into the low-resolution structure of the Mtε this α-helical structure fits well in the extended domain of Mtε (RMSD of 0.297Å [Fig. 2D]). Compared to the ε-inhibited state, εe, in the ECF1 ATPase (Fig. 5), which blocks both hydrolysis and synthesis of ATP (17), Mtε, with its shorter C-terminal domain, will not reach the upper region of the α-β interface close to the adenine-binding pocket and the N-terminal and rotating part of γ (17). The surface potential of Mtε103–120 reveals a highly positive surface charge due to the presence of arginine residues, with R109 and R113 situated on one side and R111 and R115 located on the opposite side (Fig. 3C). The two unique residues R111 and R113 on both sides of the Mtε C-terminal helix give the helix a very positive surface, enabling this region to interact strongly with the C terminus of one of the catalytic subunits and thereby regulate catalytic processes. As demonstrated recently, the very C terminus of Mtε in ATP synthases of slow- and fast-growing mycobacteria is responsible for blocking of ATP hydrolysis, preventing excess ATP consumption under low oxygen tensions (37). These studies also demonstrated that suppression of hydrolytic activity appeared to be more pronounced in the slow-growing mycobacteria, reflecting an adaptation to environments with a low energy supply and/or decreased oxygen tension, such as that found in TB lesions in the lungs (38). Mycobacteria require oxygen for growth; however, they are capable of persisting in a quiescent form under anaerobic conditions. Similar ATP hydrolysis inhibition processes are reported for the obligate aerobic bacteria Paracoccus denitrificans (39) and Micrococcus luteus (40), whose ATP synthases show variations in the inhibitory subunits, which are represented by the Pdξ (41) and the Mlδ subunit (42). Based on the specificity of the C-terminal segment of Mtε and the variability of the C termini of bacterial ε as well as the diversity of inhibitory proteins in F1FO ATP synthases described above, the C-terminal domain of Mtε becomes a promising epitope for compounds to bind and to regulate the synthesis of ATP but also to stimulate ATP hydrolysis.

Fig 5.

High-resolution model of ε with complex α3/β3 from E. coli. The recently determined crystal structure of the E. coli F1 ATPase (17) revealed the coupling and inhibitory subunit ε in an extended state (left), in which the second loop and helix of the C-terminal segment of ε contact α1, α2, β1, β3, and γ, with helix 2 inserting into the central rotary cavity of the α3β3-hexamer (right). The structure on the right is shown rotated by 35° for better viewing.

In bacterial F1FO ATP synthases, the rotor of the F1 motor and the rotor of the FO motor are generally considered to be comprised, respectively, of the γ-ε subunit pair and the c-ring (35). The interface between subunits c and ε is formed by the loop region of the hairpin-structured c subunit and the bottom of the N-terminal β-barrel of ε (12). Proton transport via the subunit a-c interface triggers rotation of the oligomeric c-ring that is coupled to rotation of the γ-ε pair, which finally drives the synthesis in the α3β3-hexamer. Based on docking studies TMC207 has been predicted to bind at the a-c interface (5). Previously, the compound was proposed to block rotary movements of subunit c by interfering with conformational changes of subunit c during ATP catalysis, by competing with the protons for binding to c, or translocating across the membrane into the cytoplasm (43). Haagsma and colleagues have demonstrated that TMC207 does not directly compete with protons for a common binding site (34) and concluded that the protonated TMC207 may interfere with conformational changes in the F1FO ATP synthase. Based on docking studies the TMC207 molecule has been predicted to bind to the hydrophobic part of subunit c (5), which has been confirmed by recent binding studies using surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy using single subunit C from M. tuberculosis (5). The presented NMR titration experiments of Mtε with TMC207 and mefloquine hydrochloride demonstrate that TMC207 does in addition specifically bind to the Mtε subunit. The calculated binding constant Kd of 19.1 μM as well as the very weak TMC207 interaction of mutants Mtε-T19A and Mtε-R37G supports the specific interaction of the drug with the regulatory ε subunit. The data also identify W15 and R87 as interacting residues (Fig. 4C). Based on the results described above and the elongated character of TMC207 (13.3 Å by 8.55 Å), we propose that the drug TMC207 affects the catalysis of ATP formation by binding to both subunit c and ε, which together form a part of the rotary elements of the two motors FO and F1. As shown in Fig. 4D, TMC207 is predicted to work like a wedge which hinders the rotary movement of the c-ring as a consequence of proton translocation and conformational alteration in the membrane-integrated helices of c. As a further consequence, subunit ε is unable to regulate the efficiency of coupling, to influence the catalytic pathway, or to modulate nucleotide specificity in the catalytic sites (21). This new model would explain why TMC207 does not compete with protons for a common binding site (34).

In conclusion, the structural details of Mtε add to nature's evolutionary strategy of varied key structural domains, along with the regulatory and inhibitory subunit ε of bacterial F1FO ATP synthases, or functionally homologue proteins, as described for IF1 (18), Pdξ (44), and the M. luteus δ subunit (42). The alterations of the C-terminal segment of Mtε may present a new target, to design new leads with improved antibacterial activities. In addition, the new insight into the interaction of TMC207 in the c-ε interface not only sheds light on the binding site of the drug but also adds to the mechanistic understanding of how the compound may act as an antibacterial in the M. tuberculosis F1FO ATP synthase. This forms a new platform to fine-tune the effect of TMC207 or to develop new compounds whose chemical as well as 3D traits will improve the effect of the wedge-shaped inhibitor and thereby the blocking of coupling events in the recently discovered TB drug target ATP synthase (5).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Sandip Basak is grateful to the Nanyang Technological University for awarding a research scholarship. This research was supported by the New Initiative Fund FY2010, NTU.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 October 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01039-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Guillemont J, Meyer C, Poncelet A, Bourdrez X, Andries K. 2011. Diarylquinolines, synthesis pathway and quantitative structure-activity relationship studies leading to the discovery of TMC207. Future Med. Chem. 3:1345–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Iino R, Hasegawa R, Tabata KV, Noji H. 2009. Mechanism of inhibition by C-terminal α-helices of the ε subunit of Escherichia coli FOF1-ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 284:17457–17464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barry CE, Boshoff HI, Dartois V, Dick T, Ehrt S, Flynn J, Schnappinger D, Wilkinson RJ, Young D. 2009. The spectrum of latent tuberculosis: rethinking the biology and intervention strategies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:845–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Diacon AH, Pym A, Grobusch M, Patientia R, Rustomjee R, Page-Shipp L, Pistorius C, Krause R, Bogoshi M, Churchyard G, Venter A, Allen J, Palomino JC, De Marez T, van Heeswijk RPG, Lounis N, Meyvisch P, Verbeeck J, Parys W, de Beule K, Andries K, Neeley DFM. 2009. The diarylquinoline TMC207 for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 360:2397–2405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koul A, Dendouga N, Vergauwen K, Molenberghs B, Vranckx L, Willebrords R, Ristic Z, Lill H, Dorange I, Guillemont J, Bald D, Andries K. 2007. Diarylquinolines target subunit c of mycobacterial ATP synthase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3:323–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koul A, Vrankx L, Dendouga N, Balemans W, Van den Wyngaert I, Vergauwen K, Göhlmann HW, Willebrords R, Poncelet A, Guillemont J, Bald D, Andries K. 2008. Diarylquinolines are bactericidal for dormant mycobacteria as a result of disturbed ATP homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 283:25273–25280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rao SP, Alonso S, Rand L, Dick T, Pethe K. 2008. The protonmotive force is required for maintaining ATP homoeostasis and viability of hypoxic, nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:11945–11950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Andries K, Verhasselt P, Guillemont J, Göhlmann HWH, Neefs JM, Winkler H, Van Gestel J, Timmerman P, Zhu M, Lee E, Williams P, de Chaffoy D, Huitric E, Hoffner S, Cambau E, Truffot-Pernot C, Lounis N, Jarlier V. 2005. A diarylquinoline drug active on the ATP synthase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 307:223–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tran SL, Cook GM. 2005. The F1FO-ATP synthase of Mycobacterium smegmatis is essential for growth. J. Bacteriol. 187:5023–5028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bald D, Koul A. 2010. Respiratory ATP synthases: the new generation of mycobacterial drug target? FEMS Microbiol. 308:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Müller V, Lingl A, Lewalter K, Fritz M. 2005. ATP synthases with novel rotor subunits: new insights into structure, function and evolution of ATPases. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 37:455–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Capaldi RA, Aggeler R, Wilkens S, Grüber G. 1996. Structural changes in the gamma and epsilon subunits of the Escherichia coli F1FO-type ATPase during energy coupling. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 28:397–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hausrath A, Grüber G, Matthews BW, Capaldi RA. 1999. Structural features of the γ subunit of the Escherichia coli F1 ATPase revealed by a 4.4-Å resolution map obtained by x-ray crystallography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:13697–13702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Uhlin U, Cox GB, Guss JM. 1997. Crystal structure of the epsilon subunit of the proton-translocating ATP synthase from Escherichia coli. Structure 5:1219–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilkens S, Capaldi RA. 1998. Solution structure of the ε subunit of the F1-ATPase from Escherichia coli and interactions of this subunit with β subunits in the complex. J. Biol. Chem. 273:26645–26651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yagi H, Kajiwara N, Tanaka H, Tsukihara T, Kato-Yamada Y, Yoshida M, Akutsu H. 2007. Structures of the thermophilic F1-ATPase ε subunit suggesting ATP-regulated arm motion of its C-terminal domain in F1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:11233–11238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cingolani G, Duncan TM. 2011. Structure of the ATP synthase catalytic complex (F(1)) from Escherichia coli in an autoinhibited conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18:701–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gledhill JR, Montgomery MG, Leslie AG, Walker JE. 2007. How the regulatory protein, IF1, inhibits F1-ATPase from bovine mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:15671–15676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kato-Yamada Y, Yoshida M. 2003. Isolated epsilon subunit of thermophilic F1-ATPase binds ATP. J. Biol. Chem. 278:36013–36016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richter ML. 2004. Gamma-epsilon interactions regulate the chloroplast ATP synthase. Photosynth. Res. 79:319–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saita E, Iino R, Suzuki T, Feniouk BA, Kinosita K, Yoshida M. 2010. Activation and stiffness of the inhibited states of F1-ATPase probed by single-molecule manipulation. J. Biol. Chem. 285:11411–11417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grüber G, Godovac-Zimmermann J, Link TA, Coskun Ü, Rizzo VF, Betz C, Bailer SM. 2002. Expression, purification, and characterization of subunit E, an essential subunit of the vacuolar ATPase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 298:383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Priya R, Biuković G, Gayen S, Vivekanandan S, Grüber G. 2009. NMR solution structure of the b30–82 domain of subunit b of Escherichia coli F1FO ATP synthase. J. Bacteriol. 191:7538–7544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Basak S, Gayen S, Thaker YR, Manimekalai MSS, Roessle M, Hunke C, Grüber G. 2011. Solution structure of subunit F (Vma7p) of the eukaryotic V1VO ATPase from Saccharomyces cerevesiae derived from SAXS and NMR spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808:360–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roessle M, Klaering R, Ristau U, Robrahn B, Jahn D, Gehrmann T, Konarev PV, Round A, Fiedler S, Hermes S, Svergun DI. 2007. Upgrade of the small angle X-ray scattering beamline X33 at the EMBL Hamburg. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40:190–194 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Svergun D. 1993. A direct indirect method of small-angle scattering data treatment. J. Appl. Cryst. 26:258–267 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guinier A, Fournet G. 1955. Small-angle scattering of X-ray, Wiley, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 28. Svergun DI, Bećirević A, Schrempf H, Koch MHJ, Grüber G. 2000. Solution structure and conformational changes of the streptomyces chitin binding protein (CHB1). Biochemistry 39:10677–10683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Volkov VV, Svergun DI. 2003. Uniqueness of ab initio shape determination in small angle scattering. J. Appl. Cryst. 36:860–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Güntert P. 2004. Automated NMR structure calculation with CYANA. Methods Mol. Biol. 278:353–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kumar A, Manimekalai MSS, Balakrishna AM, Jeyakanthan J, Grüber G. 2010. Nucleotide binding states of subunit A of the A-ATP synthase and the implication of P-loop switch in evolution. J. Mol. Biol. 396:301–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Suzuki T, Wakabayashi C, Tanaka K, Feniouk BA, Yoshida M. 2011. Modulation of nucleotide specificity of thermophilic FOF1-ATP synthase by ε subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 286:16807–16813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Berjanskii MV, Neal S, Wishart DS. 2006. PREDITOR: a web server for predicting protein torsion angle restraints. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:63–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Haagsma AC, Podasca I, Koul A, Andries K, Guillemont J, Lill H, Bald D. 2011. Probing the interaction of the diarylquionline TMC207 with its target mycobacterial ATP synthase. PLoS One 6:e23575 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. 1991. Relationship between nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift and protein secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 222:311–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Martín-Galiano AJ, Gorgojo B, Kunin CM, de la Campa AG. 2002. Mefloquine and new related compounds target the F0 complex of the F0F1 H+-ATPase of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1680–1687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Haagsma AC, Driessen NN, Hahn MM, Lill H, Bald D. 2010. ATP synthase in slow- and fast-growing mycobacteria is active in ATP synthesis and blocked in ATP hydrolysis direction. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 313:68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Via LE, Lin PL, Carrillo J, Allen SS, Eum SY, Taylor K, Klein E, Manjunatha U, Ganzales J, Lee EG, Park SK, Raleigh JA, Cho SN, McMurray DN, Flynn JL, Barry CE., III 2008. Tuberculous granulomas are hypoxic in guinea pigs, rabbits, and nonhuman primates. Infect. Immun. 76:2333–2340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zharova TV, Vinogradov AD. 2004. Energy-dependent transformation of F0.F1-ATPase in Paracoccus denitrificans plasma membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 279:12319–12324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grüber G, Godovac-Zimmermann J, Nawroth T. 1994. ATP synthesis and hydrolysis of the ATP-synthase from Micrococcus luteus regulated by an inhibitor subunit and membrane energization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1186:43–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mendel-Hartvig J, Capaldi RA. 1991. Nucleotide-dependent and dicyclohexyl-carbodiimide-sensitive conformational changes in the ε subunit of Escherichia coli ATP synthase. Biochemistry 30:10987–10991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Grüber G, Engelbrecht S, Junge W, Dose K, Nawroth T. 1994. Purification and characterization of the inhibitory subunit δ of the ATP-synthase from Micrococcus luteus. FEBS Lett. 356:226–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kaneko T, Cooper C, Mdluli K. 2011. Challenges and opportunities in developing novel drugs for TB. Future Med. Chem. 3:1373–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Morales-Ríos E, de la Rosa-Morales F, Mendoza-Hernández G, Rodríguez-Zavala JS, Celis H, Zarco-Zavala M, García-Trejo JJ. 2010. A novel 11-kDa inhibitory subunit in the F1FO ATP synthase of Paracoccus denitrificans and related alpha-proteobacteria. FASEB J. 24:599–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dmitriev O, Jones PC, Jjiang W, Fillingame RH. 1999. Structure of the membrane domain of subunit b of the Escherichia coli FOF1 ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15598–15604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Priya R, Tadwal SV, Roessle M, Gayen S, Hunke C, Peng WC, Torres J, Grüber G. 2008. Low resolution structure of subunit b (b22–156) of Escherichia coli F1Fo ATP synthase in solution and the b–δ assembly. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 40:245–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.