Abstract

The cholesterol-dependent cytolysins (CDCs) are pore-forming toxins that have been exclusively associated with a wide variety of bacterial pathogens and opportunistic pathogens from the Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, which exhibit a Gram-positive type of cell structure. We have characterized the first CDCs from Gram-negative bacterial species, which include Desulfobulbus propionicus type species Widdel 1981 (DSM 2032) (desulfolysin [DLY]) and Enterobacter lignolyticus (formerly Enterobacter cloacae) SCF1 (enterolysin [ELY]). The DLY and ELY primary structures show that they maintain the signature motifs of the CDCs but lack an obvious secretion signal. Recombinant, purified DLY (rDLY) and ELY (rELY) exhibited cholesterol-dependent binding and cytolytic activity and formed the typical large CDC membrane oligomeric pore complex. Unlike the CDCs from Gram-positive species, which are human- and animal-opportunistic pathogens, neither D. propionicus nor E. lignolyticus is known to be a pathogen or commensal of humans or animals: the habitats of both organisms appear to be restricted to anaerobic soils and/or sediments. These studies reveal for the first time that the genes for functional CDCs are present in bacterial species that exhibit a Gram-negative cell structure. These are also the first bacterial species containing a CDC gene that are not known to inhabit or cause disease in humans or animals, which suggests a role of these CDCs in the defense against eukaryote bacterial predators.

INTRODUCTION

The cholesterol-dependent cytolysins (CDCs) are pore-forming toxins that are produced by many bacterial pathogens and opportunistic pathogens from the Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, which exhibit a Gram-positive cell structure. These include species from the genera Clostridium, Streptococcus, Bacillus, Lactobacillus, Listeria, Gardnerella, and Brevibacillus. CDCs are released from the bacterial cell as soluble monomeric proteins of 50 to 70 kDa that bind to cholesterol-containing membranes and assemble into large oligomeric β-barrel pore complexes (reviewed in reference 1). The pore complex is typically composed of 35 to 40 monomers and forms a pore with a diameter of 25 to 30 nm. The pore-forming mechanism exhibits an absolute dependence on the presence of membrane cholesterol, which serves as a receptor for most CDCs. The CDCs contribute to pathogenesis in a variety of ways that include translocation of a protein into the eukaryotic cell by Streptococcus pyogenes (2), phagosomal escape by the intracellular pathogen Listeria monocytogenes (3), and leukostasis and escape from macrophages (4) during Clostridium perfringens gas gangrene (5). CDCs have not been identified in the Proteobacteria although evolutionarily related genes for protein toxins are rarely shared between bacteria that exhibit Gram-positive and Gram-negative cell structures.

The advent of large-scale genome sequencing has expanded our ability to identify additional members of various toxin families. Inspection of the genomes of Desulfobulbus propionicus type species Widdel 1981 (otherwise know as strain 1pr3T, DSM 2032, ATCC 33891, VKM B-1956, or DSM2032) (Deltaproteobacteria) (6) and Enterobacter lignolyticus SCF1 (Gammaproteobacteria) (7) has unexpectedly revealed the presence of genes that encode putative CDCs. D. propionicus type species Widdel 1981 and E. lignolyticus SCF1 inhabit environmental niches and are not known to be human or animal pathogens or commensals. D. propionicus is an anaerobic Gram-negative, lemon-shaped bacterium typically found in the anaerobic sediment of eutrophic freshwater lakes and streams as well as marine estuaries. D. propionicus type species Widdel 1981 (8) was isolated from the anaerobic mud of a village ditch in the municipality of Lindhorst near Hannover, Germany. D. propionicus incompletely oxidizes lactate, propionate, butyrate, and ethanol to acetate when sulfate is available as an electron acceptor although it can also ferment some organic acids in the absence of an electron acceptor. It was also the first bacterial species isolated that could disproportionate elemental sulfur to sulfide and sulfate (9), and strains are present in anaerobic sludge bed reactors used in the treatment of sulfate-rich wastewater (10).

E. lignolyticus SCF1 (formerly classified as E. cloacae SCF1) is a rod-shaped Gram-negative bacterium that has been frequently isolated from the anaerobic environment of Puerto Rican tropical forest soils (7). Although it is a facultative organism, it was found to primarily grow anaerobically in these settings with lignin or switchgrass as the sole carbon source. Interest in both bacterial species stems from their association with processes that may be important to the development of alternative energy sources: E. lignolyticus degrades lignin, which may be important in the development of biofuels, and D. propionicus has been associated with the generation of electricity from marine sediments by its ability to use a graphite electrode as an electron acceptor.

Until now the CDCs appeared to be an exclusive feature of bacteria that exhibit the Gram-positive type of cell structure of bacterial pathogens and opportunistic pathogens. Herein we show for the first time the presence of a CDC gene in species from the Proteobacteria and show that purified recombinant forms of the gene products are highly active pore-forming toxins. These CDC genes are also the first to be identified in bacterial species that are not associated with humans or animals as commensals or pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and PCR mutagenesis of the Proteobacteria-derived CDC genes.

The amino acid sequences for the CDCs from D. propionicus (desulfolysin [DLY]) (GenBank accession YP_004194591), Enterobacter lignolyticus SCF1 (enterolysin [ELY]) (GenBank accession YP_003942590.1), and Oxalobacter formigenes (oxalolysin [OLY]) (ZP_04576513) were codon optimized for expression in Escherichia coli (Genscript). The synthesized genes were cloned into the NdeI/XhoI site of the Escherichia coli expression vector pET22. The native stop codon was included to prevent translation of the C-terminal 6×His tag although this stop codon was changed to alanine in ELY to allow the addition of the His tag to ELY. Amino acid substitutions were created using the QuikChange method (Stratagene). The Laboratory for Molecular Biology and Cytometry Research at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center performed all sequence analysis.

Expression and purification of rDLY, rELY, and rOLY.

The plasmids encoding recombinant DLY (rDLY), rELY, and rOLY were transformed into the E. coli expression strain Tuner(DE3)/pLysS (Novagen). An overnight culture grown in Terrific Broth (TB) was used to inoculate a 2-liter culture (1:100) for expression. Cultures were grown aerobically at 37°C to an optical density (OD) of about 1.0 and then induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The induced culture was grown for an additional 3 h, and the cells were harvested by centrifugation. Cell pellets from the 2-liter culture were suspended in 100 ml of anion exchange buffer A (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) for rDLY or cobalt buffer A (10 mM morpholineethanesulfonic acid [MES], 150 mM NaCl, pH 6.5) for His6-tagged rELY. A Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablet (Roche) was added, and cells were lysed with an EmulsiFlex-C3 homogenizer (Avestin). The cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 20 min. The rDLY-containing supernatant was loaded onto a column (2.5 by 15 cm) containing Q-Sepharose Fast Flow (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) equilibrated in buffer A. The column was eluted with a 225-ml linear gradient (3 ml/min) from 5 to 35% anion exchange buffer B (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 M NaCl, pH 8.0). Fractions containing rDLY were pooled and diluted 1:3 with buffer A and loaded on a high-resolution Mono Q column (1 by 10 cm) (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The column was again eluted with a linear gradient (2 ml/min in total volume of 225 ml) from 5 to 35% of buffer B, and hemolytic fractions were collected and subjected to SDS-PAGE for purity analysis. Mass spectrometry was performed by the Laboratory for Molecular Biology and Cytometry Research at the University of Oklahoma Health Science Center.

The above purification approach did not work for rELY as it apparently did not carry a sufficient charge to keep it bound to either anion or cation exchange resins. Therefore, the stop codon was mutated to an alanine residue to allow fusion of the hexahistidine tag to its C terminus. This allowed the affinity purification of rELY using a cobalt-loaded metal chelate column (GE Healthcare). After loading, the column was washed with cobalt buffer A until the absorbance decreased to within 10% of the baseline, and then a gradient (4 ml/min) from 3% to 15% of cobalt buffer B (10 mM MES, 1 M Imidazole, pH 6.5) was carried out in a total of 150 ml. The gradient was held at 50% cobalt buffer B (3 ml/min) for 40 min to elute rELY. Purified rDLY and rELY proteins were made in 1 mM in dithiothreitol (DTT) and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol and stored at −80°C. Cultures failed to express the rOLY gene when induced with IPTG, so no further expression/purification strategy was performed for OLY.

HA.

The hemolytic activity (HA) of rDLY and rELY was determined by serially diluting the toxin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (final volume, 50 μl) and then incubating it with 50 μl of washed human erythrocytes (5% in PBS). The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and erythrocytes were removed by centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 5 min. Hemoglobin release was quantified by measuring the A540 of the supernatant. The computer software Prism was used to calculate the effective concentration dosage required to lyse 50% of erythrocytes (EC50).

SDS-AGE.

POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-choline)/cholesterol liposomes were prepared by extrusion as previously described (11). Lipids and cholesterol were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids. Detection of the rDLY and rELY monomers and oligomers by SDS-agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE) was performed as previously described (12). Briefly, 10 μg of toxin was incubated with 5 μl of liposomes and brought to a final volume (30 μl) with Hanks buffered saline (HBS). Samples were incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Samples were prepared for loading on the gel by the addition 4 μl of 25% SDS (wt/vol) and 6 μl of sample buffer (0.1% [wt/vol] bromphenol blue, 40% [vol/vol] glycerol, and 25% SDS [wt/vol] made up in reservoir buffer). Samples were loaded on a 1.5% SeaPlaque agarose (FMC, Rockland, ME) gel without heating, and the gel was run at 120 V for 60 min. The gel was rinsed for 60 min in 300 ml of a fixative solution comprised of 10% (vol/vol) acetic acid and 30% (vol/vol) methanol in distilled water. The gel was then removed from the fixative solution and pressed between paper towels overnight to remove most of the water and then further air dried in a Hoefer (San Francisco, CA) Easy Breeze gel dryer. The dried gel was then stained with Coomassie dye (0.25%) in the fixative solution (60 min) and then destained with the fixative solution.

Liposome release assay.

5,6-Carboxyfluorescein (CF) encapsulated liposomes were made by mixing 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) and cholesterol at a ratio of 45:55 mol% in chloroform. The mixture was dried under a stream of argon at 40°C, resuspended in 3 ml of ether, and dried again under argon at 40°C. The lipid-sterol mixture was then further dried under vacuum for 3 h. The dried lipid-sterol mixture was resuspended in 3 ml of HBS-CF buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM CF) and vortexed vigorously until a completely uniform suspension was obtained. The lipid mixture was carried through three freeze-thaw cycles using liquid nitrogen and room temperature (22°C) water. The lipid mixture was then passed 21 times through an Avestin Liposofast extruder, equipped with a polycarbonate membrane (100-nm pore size), to generate unilamellar liposomes. The CF liposomes were used within 7 days of preparation.

Similar to hemolytic assays, serial dilutions of toxin (100-μl final volume) were incubated with 100 μl of CF liposomes (diluted 1:1,000 in PBS). Reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Fluorescence measurements were taken on a fluorescence plate reader (Infinite F200PRO Tecan) (excitation at 485 nm/emission at 535 nm). The 50% effective concentration (EC50) for toxin-dependent CF release was calculated using a nonlinear sigmoidal dose-response curve fit of the data (Prism software). A no-toxin control was used to determine background fluorescence.

Electron microscopy of DLY oligomers.

Samples were fixed onto Formvar carbon-filmed grids for 5 min and then negatively stained with a 2% (wt/vol) solution of neutralized phosphotungstic acid for 15 s. Samples were examined and photographed on a JEOL 2000FX transmission electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at the University of Oklahoma Samuel Roberts Noble Electron Microscopy Laboratory.

SPR.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) was measured with a BIAcore T100 system (Laboratory for Molecular Biology and Cytometry Research at the University of Oklahoma Health Science Center) using an L1 sensor chip (BIAcore). An L1 chip was loaded with liposomes with a flow rate of 10 μl/min. Initially 10 μl of 20 mM CHAPS (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate) was injected, followed by injection with liposomes (final lipid concentration, 0.5 mM) at the same flow rate for 15 min. After injection of liposomes, 50 mM NaOH was injected for 3 min, followed by injection of 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 min. All injections were performed at 25°C. The L1 chip was regenerated and stripped of liposomes by repeated injections of 20 mM CHAPS and 50 mM NaOH until original resonance unit (RU) readings were reached. No loss of sensor chip binding capacity resulted from regeneration. Binding analyses were performed in HBS (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) at 25°C. Consecutive 50-μl injections of toxin (100 ng per injection) were passed over the liposome-coated chip at a flow rate of 10 μl/min until saturation was reached. Prism software was used to plot the changes in resonance units. No change in the RUs was observed due to buffer. Nonspecific binding to liposomes lacking cholesterol was subtracted from the data as a control.

RNA harvesting and qRT-PCR.

D. propionicus species Widdel 1981 (a kind gift of D. Lovely, University of Massachusetts) was grown anaerobically at 37°C in pure culture on a pyruvate and sulfate medium as described herein. One liter of Tanner's sulfate medium was prepared and autoclaved as described previously (13), to which 50 ml of filter-sterilized 20 mM pyruvate stock was added. Cultures of E. lignolyticus SCF1 (a generous gift of K. DeAngelis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA) were grown aerobically in tryptic soy broth at 37°C. Cells were harvested at various time intervals until the cultures achieved stationary phase. Harvesting was accomplished by rapid cooling in a dry ice-ethanol bath and centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 15 min. For both D. propionicus and E. lignolyticus, the following experiments were performed in triplicate on separate cultures. Cell pellets were suspended in RNAlater and stored at −80°C, and the total RNA was then obtained using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). DNA was removed by using on-column DNA digestion with an RNase-free DNase Set (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). RNA was verified to be free of DNA contamination by PCR without reverse transcriptase with the same primer set used for quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR). The primers used to detect the DLY cytolysin gene were Despr_1128F (GCGGCGAGATTCGTCTTGAG) and Despr_1128R (ACCTTGTAGCCCGAAGTCCG), and those for the DNA gyrase were Despr_3291F (TACGAAGGAAGGCGGTTCCC) and Despr_3291R (TTGAGAATCCCTCGGGCCAC). The primers for detection of the ELY gene were ELY_F (CGCAGACACGCACTCCATTG) and ELY_R (GTTTTGCTGGCAGGCCAGACATTG), and those for the DNA gyrase were GyrB_F (GCCTGATTGCGGTGGTTTCC) and GyrB_R; (CGATAATCTTGCCGACGACGAT).

qRT-PCR was performed using an MyIQ real-time PCR system and an iScriptT One-Step RT-PCR Kit with SYBR green (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Each reaction mixture (25-μl total volume) consisted of 12.5 μl of IQ SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad), 8 μl of nuclease-free water, 1.5 μl (10 μM) of the gene-appropriate primer, 0.5 μl of reverse transcriptase, and 1.0 μl of RNA. qRT-PCR generally followed a standard one-step protocol consisting of 10 min at 50°C and 5 min at 95°C, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. No primer dimers were observed in any primer set, as determined by melting curve analysis of qRT-PCR amplicons. Amplification efficiency was determined by testing the primers against decreasing concentrations of DNA. Also, the positive PCR control with DNA showed only one band of the correct size, and the DNA melting curves exhibited only a single peak showing a single hit for the primer set used. The qRT-PCR amplification curves were consistent for all three replicates and the cycle threshold (CT) versus DNA concentration curve was linear, with a slope of 3.32 giving a binding efficiency of 2, showing specific amplification. The expression level of a target gene was normalized to the expression level of the reference gene or, for absolute quantification, to a standard of known copy number (14), using the following equation: NE = (Ereference)CT(reference)/(Etarget)CT(target), where NE is normalized expression and E is expression.

RESULTS

Identification of Proteobacteria-associated CDC genes.

PSI-BLAST was used to search the GenBank nonredundant translated nucleotide database using the primary structure of the secreted form of the Clostridium perfringens CDC, perfringolysin O (PFO) (15). This search revealed the presence of putative CDC genes in three species of the Proteobacteria that encoded proteins that exhibited 50 to 66% similarity across the entire primary structure of secreted PFO. These putative CDCs were present in Enterobacter cloacae (now E. lignolyticus) (Gammaproteobacteria) (YP_003942590.1) and Desulfobulbus propionicus (Deltaproteobacteria) (YP_004194591) (Fig. 1) and are herein termed enterolysin (ELY) and desulfolysin (DLY), respectively. A third potential CDC was identified in the genome of Oxalobacter formigenes (ZP_04576513) (Betaproteobacteria) (termed herein oxalolysin [OLY]). The major signature motifs of the CDCs are present in all three proteins (Fig. 1). These motifs include the highly conserved undecapeptide (or Trp-rich motif), which is the primary signature motif of the CDCs, an essential diglycine pair in the turn between β-strands 4 and 5 conserved in all CDCs (16), and the cholesterol recognition/binding motif (CRM) (17). Both the diglycine and the cholesterol binding motifs are maintained intact in OLY, DLY, and ELY. The undecapeptide motif is highly conserved in DLY and ELY but less so in OLY. The Gram-negative bacteria-derived CDCs share additional highly conserved motifs (Fig. 1) of the CDCs; however, these motifs have yet to be assigned a function.

Fig 1.

Primary structures of Gram-negative bacteria-derived CDCs. The primary structures of DLY, ELY, and OLY were compared with the primary structure of PFO. Homology comparison was carried out using Clustal X (49). The conserved undecapeptide (UND), cholesterol recognition motif (CRM), twin-glycine motif, and the transmembrane hairpins (TMH) are highlighted. Other conserved motifs (CM) are shown that are not associated with a specific CDC function but are highly conserved in the CDCs from Gram-positive bacteria. The arrow indicates the N terminus of the secreted PFO protein. Asterisk, conserved residues; colon, conservative substitutions.

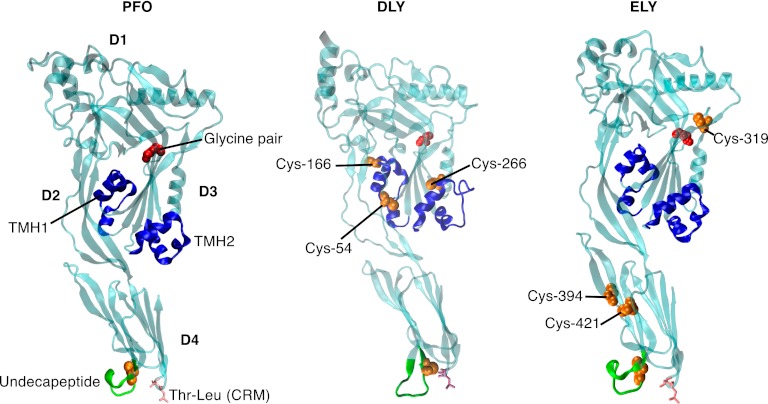

The locations of these signature motifs are shown on molecular models of the DLY and ELY soluble monomers, which are based on the crystal structures of the soluble monomers of the Streptococcus intermedius CDC, intermedilysin (ILY) (18) and PFO (19), respectively (Fig. 2). The structural models were generated using Swiss-Model (20) in the automated mode. Although DLY was modeled on the ILY structure, there was no evidence that it (or ELY) was a member of the CD59-binding class of CDCs typified by ILY as it did not contain the domain 4 signature motif (YXYX14RS) that is associated with CD59-binding CDCs (21).

Fig 2.

Molecular models of rDLY and rELY. Molecular models of the soluble monomers of DLY and ELY were generated using Swiss-Model (50) and the crystal structures of the Streptococcus intermedius CDC, intermedilysin (ILY) (18) and PFO (23) as templates, respectively. Shown are the locations of the conserved CDC motifs shown in Fig. 1 on the crystal structure of the PFO monomer (1PFO): undecapeptide, (green), CRM (magenta), diglycine motif (red, space-filled atoms), and the α-helical bundles that ultimately form the transmembrane β-hairpins (TMHs) (blue). The analogous motifs are color coded on the structural models of DLY and ELY. Also identified on the structures of DLY and ELY are the predicted locations of the cysteine residues (orange space-filled atoms) that are unique to ELY and DLY. D1-D4, domains 1 to 4.

In contrast to the Gram-positive CDCs, ELY and DLY lack a canonical type II signal peptide, which suggests that their release from the bacterial cell occurs by another mechanism(s). OLY exhibits an additional amino terminal peptide of about 40 residues, but it is unclear what, if any, role it may have in secretion.

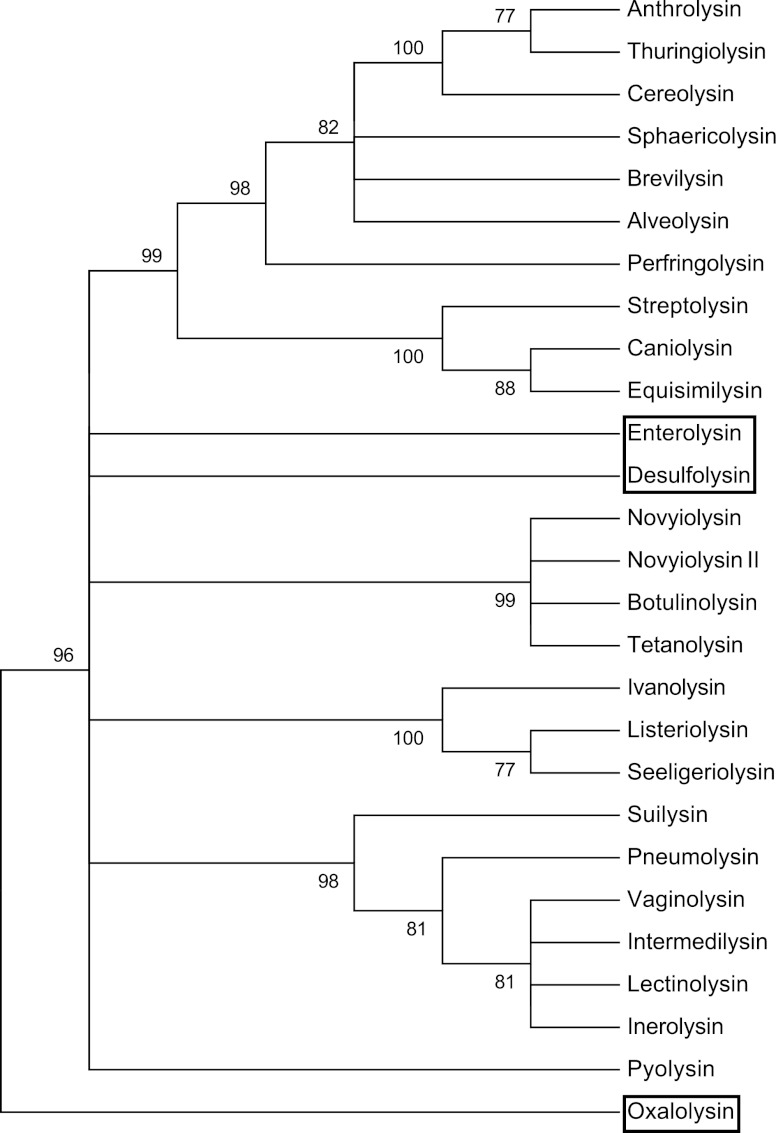

When the three Proteobacteria-derived CDCs were placed into a phylogenetic tree using the maximum-parsimony method, they did not group with the major clades of CDCs derived from the Firmicutes and Actinobacteria (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Maximum parsimony tree analysis of the CDCs. The evolutionary history of the CDC proteins was inferred using the maximum-parsimony (MP) method. Tree 1 out of 3 of the most parsimonious trees is shown. For parsimony-informative sites, the consistency index is 0.588558, the retention index is 0.648947, and the composite index is 0.381943. For all sites, the composite index is 0.386973. The percentages of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (500 replicates) are shown next to the branches (51). The MP tree was obtained using the close-neighbor interchange algorithm (52) with search level 1 in which the initial trees were obtained with the random addition of sequences (10 replicates). The analysis involved 27 amino acid sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 432 positions in the final data set. Branches with bootstrap values of less than 75 were condensed. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA5 (53).

Expression of rDLY, rELY, and rOLY in E. coli.

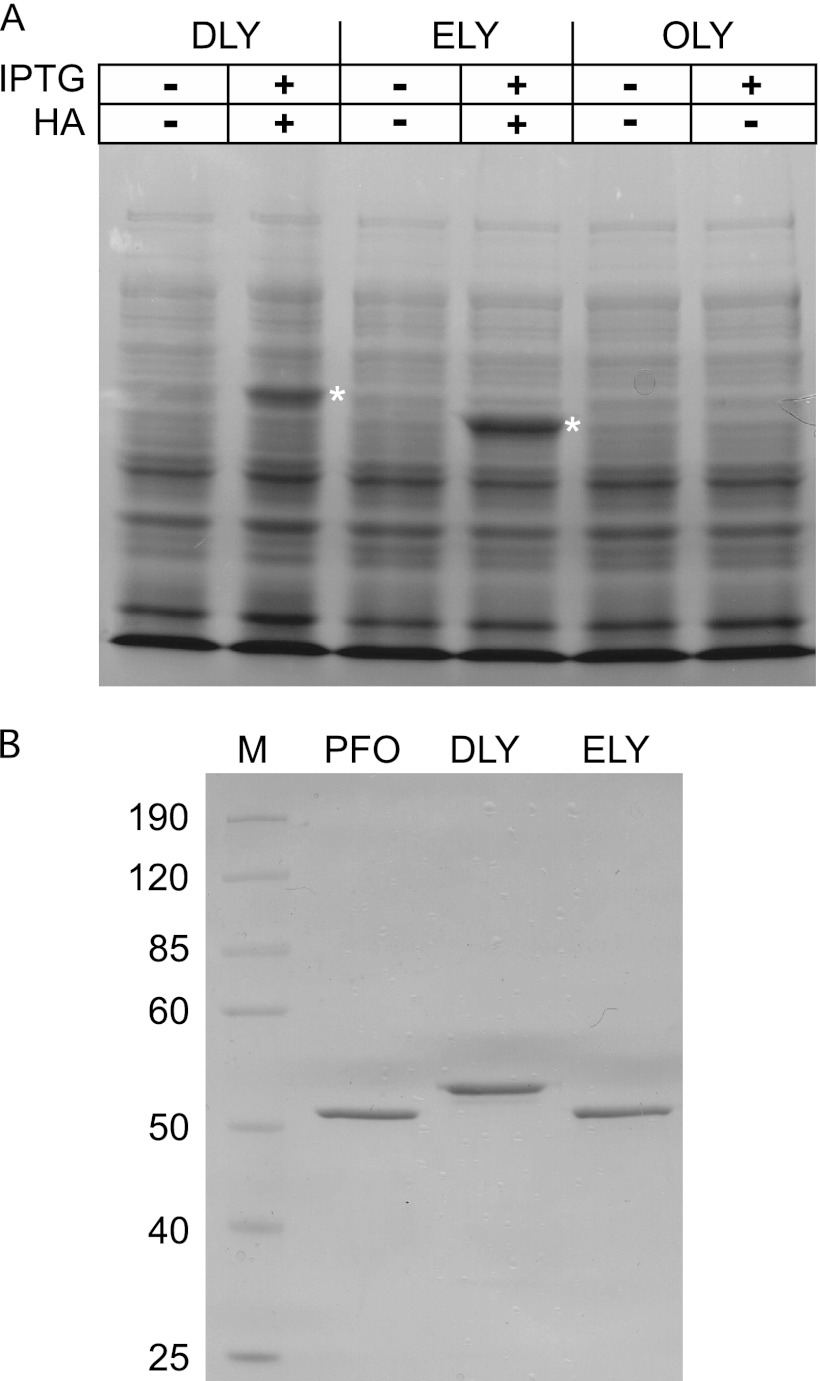

The genes for rDLY, rELY, and rOLY were synthesized and codon optimized for expression in E. coli in their native forms (i.e., no affinity tags were initially fused to the native protein structures). Whole-cell lysates from induced cultures were assayed for hemolytic activity and separated by SDS-PAGE. Only whole-cell extracts from induced E. coli cultures containing the recombinant gene for ELY exhibited an intense protein that was the approximate mass of the ELY protein predicted from the gene sequence (Fig. 4A). The cell lysate from the culture expressing the DLY gene also exhibited a single intense band when induced, but it migrated more slowly than expected, based on the predicted mass of DLY from its gene. The crude cell lysates from these two cultures also exhibited significant hemolytic activity on human red blood cells (RBCs) (data not shown). When the rOLY gene was induced, no obvious protein band (Fig. 4A) or hemolytic activity (data not shown) was detected in the crude lysate. Therefore, only rELY and rDLY proteins were purified and characterized further.

Fig 4.

Expression of rDLY, rELY, and rOLY. (A) Whole-cell lysates of E. coli expressing the codon-optimized genes (+ IPTG) for the recombinant forms of DLY, ELY, and OLY. Detection of hemolytic activity (HA) was determined for the crude cell lysate. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of purified recombinant DLY (lane 2) and ELY (lane 3) compared to purified PFO (lane 1). The proteins were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and visualized by Coomassie stain. Densitometry analysis using ImageJ software (54) was used to estimate the purity of the proteins (data not shown). Lane M, molecular mass markers (values at left in kDa). The white asterisks denote the positions of the rDLY and rELY protein bands that were overexpressed in the crude lysates.

Purification and cytolytic activity of rDLY and rELY.

Initial purification attempts of rELY without an affinity tag were unsuccessful as it exhibited poor binding to cation and anion exchange resins. A C-terminal hexahistidine tag was engineered onto rELY, which facilitated its purification using a cobalt-loaded metal chelate resin and did not interfere with its cytolytic activity. rDLY was purified without an affinity tag by using two successive medium- and high-resolution anion exchange resins. Approximately 95% purity was achieved for both proteins, based on densitometry analysis of the SDS-PAGE analysis of the proteins (Fig. 4B). The predicted masses of DLY and ELY were 52,848 Da and 52,299 Da, respectively, which are similar to the mass of the secreted form of PFO (52,670 Da). When the purified toxins were separated by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4B), rDLY exhibited an anomalous migration that suggested a higher mass than expected. Mass spectrometry of the excised rDLY band, however, showed its mass to be approximately 52,819 Da, similar to the 52,848 Da predicted from the primary structure. The migration of rDLY in the gel is apparently due to factors unrelated to the mass of the protein. rELY and rPFO ran as expected with the additional mass of their affinity tags.

Comparison of the hemolytic activities showed that they were similar to those observed for rPFO (Table 1) and other CDCs. The specific activity of hemolysis for rDLY was approximately three times greater than that for rPFO, whereas rELY was about 60% as active as rPFO.

Table 1.

Hemolytic activity of rPFO, rELY, and rDLY

| Toxin | EC50 (nM)a | % rPFO activity |

|---|---|---|

| rPFO | 0.35 ± 0.06 | 100 |

| rDLY | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 292 |

| rELY | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 63 |

EC50, effective concentration for 50% lysis of a standard erythrocyte suspension.

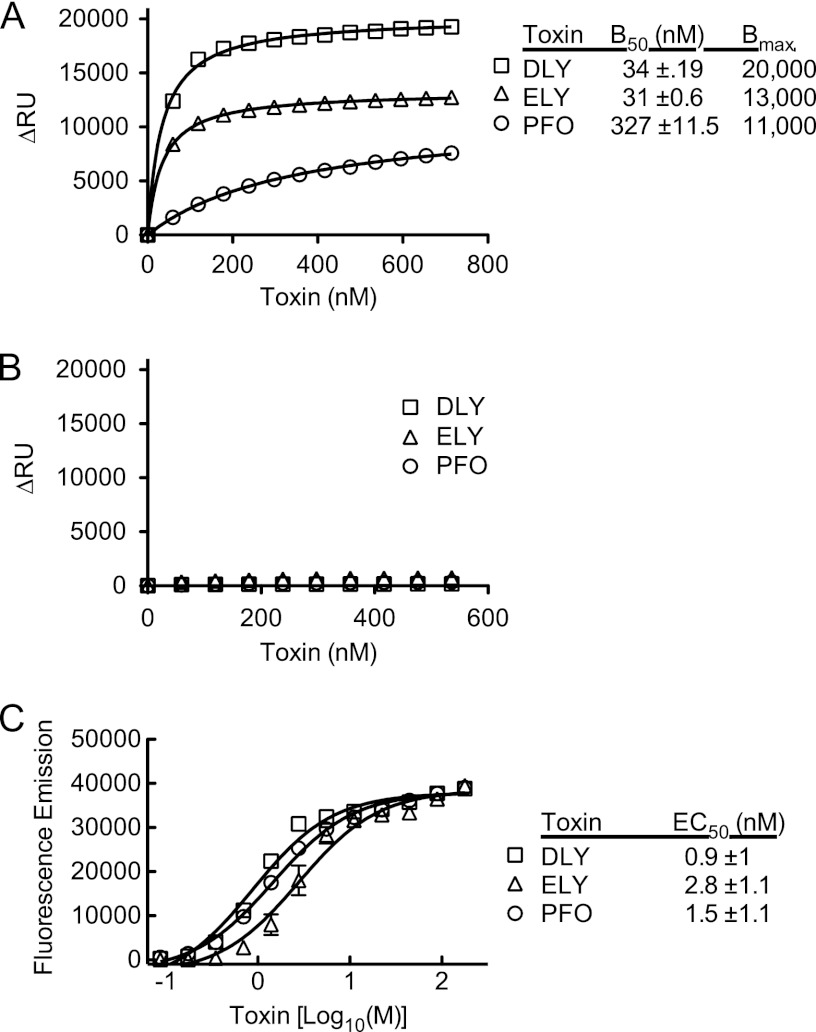

Sterol-dependent binding by rDLY and rELY.

rDLY and rELY each contain the consensus cholesterol recognition/binding motif (CRM) of the CDCs (17), which is comprised of a Thr-Leu pair in loop L1 in domain 4 (Fig. 1). Using surface plasmon resonance, the cholesterol-dependent binding activities of rDLY and rELY were compared to the activity of rPFO. rDLY and rELY were found to exhibit cholesterol-dependent binding to the cholesterol-phosphatidylcholine liposomes (Fig. 5A), whereas no significant binding to liposomes comprised of only phosphatidylcholine (Fig. 5B) was observed.

Fig 5.

SPR analysis of cholesterol-dependent binding of rDLY and rELY. (A) SPR was used to analyze the binding of rDLY, rELY, and rPFO to an L1 chip loaded with cholesterol/POPC liposomes. (B) Binding to POPC-only liposomes. The binding to the cholesterol-POPC liposomes shown in panel A is the net binding obtained after the nonspecific binding to the POPC liposomes shown in panel B was subtracted. In panel C the EC50 (effective concentration of toxin required for 50% marker release from liposomes) for each toxin was determined for marker release from liposomes loaded with carboxyfluorescein.

The concentration for 50% binding (B50) of rDLY and rELY to the cholesterol-rich liposomes was approximately 10-fold lower than that observed for rPFO (Fig. 5C), which showed that they exhibited a higher affinity than rPFO for the membrane surface although the maximum number of binding sites (Bmax) for all three CDCs was between 10,000 and 20,000. The difference in B50 values was not due to an increased off-rate of one versus another: once bound to the membrane, the toxins oligomerized, thereby significantly increasing the avidity. Furthermore, no significant off-rate was detected for any of the three toxins (data not shown).

We then examined the ability of both proteins to release a fluorescent dye entrapped in the same cholesterol-rich liposomes. The EC50 (effective concentration of toxin required to release 50% of the entrapped dye) of rDLY was 2-fold lower than that for rPFO, whereas the EC50 for rELY was about 2-fold higher than for rPFO.

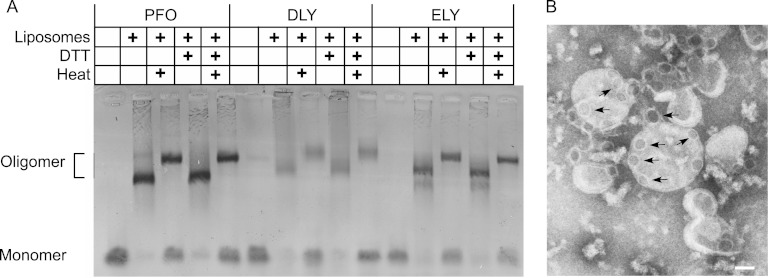

rDLY and rELY oligomer formation.

SDS-agarose gel electrophoresis (SDS-AGE), which can separate the monomeric and membrane oligomeric pore complex of the CDCs (12), showed that rELY and rDLY formed typical large SDS-stable oligomeric structures on cholesterol-rich liposomes (Fig. 6A). The masses of the rDLY and rELY oligomers appeared to be similar to the mass of rPFO, suggesting that their oligomers were comprised of a similar number of monomers. Heating the oligomers in the presence of SDS appears to open up the structure so that they migrate more slowly in the gel than when they are not heated.

Fig 6.

Membrane oligomer formation by rDLY and rELY. (A) Purified rPFO, rDLY, and rELY were incubated in the presence or absence of cholesterol-rich liposomes, and then the monomer and oligomer species were separated by SDS-AGE. Also shown is whether the sample was heated at 95°C (Heat). Shown is the Coomassie-stained gel. (B) Electron micrograph of rDLY oligomer. rDLY oligomers were formed on cholesterol-rich liposomes for 30 min at room temperature. The rDLY oligomers (examples of oligomeric pore complexes denoted by arrows) were imaged by electron microscopy. Magnification, ×100,000. Scale bar, 50 nm.

Both ELY and DLY have the conserved undecapeptide cysteine, as well as three additional cysteine residues located throughout their structures (Fig. 2). In neither DLY nor ELY are these cysteines predicted to form an intramolecular disulfide based on the molecular models (Fig. 2). In DLY, however, a cysteine was present in each of the α-helical bundles that form transmembrane hairpins 1 (TMH1) (Cys-166) and 2 (TMH2) (Cys-266) (Fig. 2). Cys-166 and Cys-266 could potentially form an intermolecular disulfide that would stabilize the β-barrel pore. However, no difference in the stability of the oligomer to dissociation by SDS and heat was observed when a reducing reagent (dithiothreitol) was added to the sample buffer.

The rDLY oligomer exhibited a somewhat smeared appearance on the gel. Because of this anomalous behavior, we examined the oligomer structure of rDLY on cholesterol-rich liposomes by electron microscopy (EM) (Fig. 6B). A typical rPFO oligomer is composed of approximately 37 monomers and has a diameter of 25 nm (22). The average diameter of the rDLY oligomer was calculated to be 25.8 nm ± 3.6 nm (n = 16) with the circumference of the oligomer measuring 81 nm. Using the width of the rPFO (≈2.3 nm) calculated from its monomer crystal structure (19), the average number of rDLY monomers per oligomer was approximately 35 monomers, consistent with rPFO (22). The smeared appearance of the oligomer was likely due to the association of oligomers, which were not completely dissociated by the treatment with SDS alone, rather than to the distribution of increasingly large oligomers.

Collectively, these data showed that rELY and rDLY exhibited significant hemolytic activity and formed large, SDS- and heat-resistant oligomeric complexes on cholesterol-rich liposomes, similar to PFO.

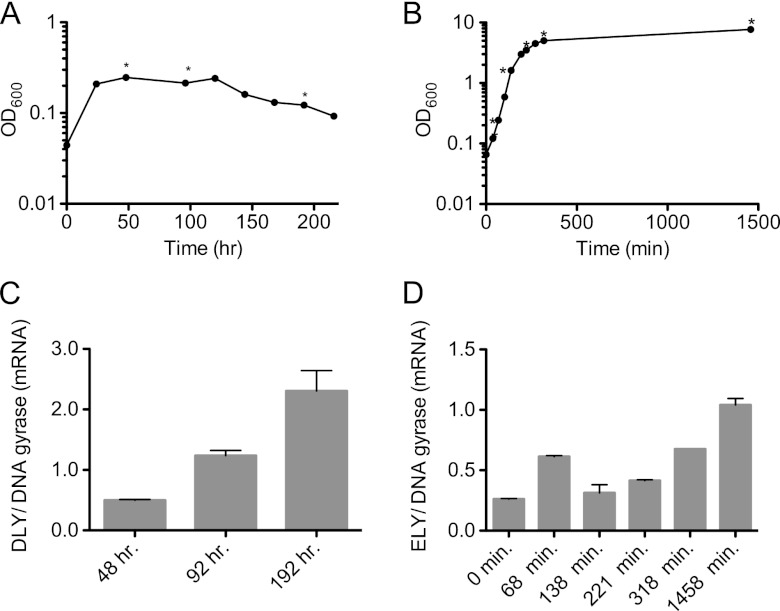

DLY and ELY mRNA and protein expression in D. propionicus cultures.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to quantify DLY and ELY mRNA levels in pure cultures of D. propionicus and E. lignolyticus. The growth of D. propionicus and E. lignolyticus was monitored by optical density, and samples were harvested at the times shown in Fig. 7A and B. Total mRNA was isolated from the cultures, and mRNA expression levels of the DLY and ELY genes were determined. Transcription of both genes was detected in samples taken at each of the time points during growth (Fig. 7C and D). During the earliest time points of growth, DLY mRNA levels were approximately 2-fold less than the level of the housekeeping gene DNA gyrase, whereas the ELY mRNA was about 4-fold less than that of the gyrase mRNA. In both cultures of E. lignolyticus, a spike in the ELY mRNA to a level 50% of the gyrase mRNA was detected at 68 min, and then it decreased. For both DLY and ELY, the mRNA levels increased as the cultures progressed toward stationary phase although the levels of the DLY mRNA increased to a greater extent than that of the ELY mRNA.

Fig 7.

Expression of the ELY and DLY mRNAs. (A) Growth curve of D. propionicus (DSM 2032) that was grown in pure culture on pyruvate and sulfate medium. Graphed is the average OD at 600 nm (OD600) of 15 samples. Cultures were harvested in triplicate at the time points indicated with an asterisk (*). (C) The ratio of DLY mRNA to the mRNA for DNA gyrase is shown for 48 h, 92 h, and 192 h of growth. Panels B and D show data from experiments performed as described for panels A and C except that two cultures of E. lignolyticus SCF1 grown in Trypticase soy broth were used, and data reflect different time points, as indicated on the graphs.

Neither culture exhibited any detectable hemolytic activity from either the concentrated spent culture medium or the cell lysate (data not shown). Attempts at detecting the CDCs using polyclonal antibodies to ILY, PFO, and streptolysin O (SLO) were unsuccessful as these antibodies did not cross-react with either purified rDLY or rELY. Polyclonal antibodies raised directly to rDLY were unable to detect toxin production in vivo by Western blotting (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The studies described herein demonstrate that rDLY and rELY are bona fide CDCs, and they are the first CDCs to be encoded by any Gram-negative bacterial species. Furthermore, they are the first examples of CDC genes possessed by bacterial species that are exclusively found in environmental habitats and are not known to be associated with humans or animals in any capacity. This is in sharp contrast to the CDCs from Gram-positive species, which are produced by a wide variety of human and/or animal pathogens or opportunistic pathogens. The DLY and ELY primary structures share the signature motifs of the characterized CDCs, which have been shown to play critical roles in the pore-forming activity of PFO (reviewed in reference 1). Both recombinant CDCs also exhibit the pore-forming features of the CDC family, which are typified by the cholesterol dependence of the pore-forming mechanism and the formation of a large oligomeric pore complex (11, 22, 23). Therefore, the CDCs can no longer be considered an exclusive feature of bacterial pathogens and opportunistic pathogens from bacteria that exhibit a Gram-positive cell structure. Yet, as discussed below, the CDCs are conspicuously absent from the Gram-negative pathogens.

We identified a third CDC candidate in the genome of the oxalate-degrading O. formigenes HOxBLS, which is being considered as a probiotic for the treatment of hyperoxaluria, which can lead to the formation of calcium oxalate kidney stones (24). Why rOLY was not expressed in E. coli was unclear but may be related to the unusual amino terminal peptide. The predicted secreted form of OLY exhibits 50% similarity (33% identity) with the PFO primary structure and exhibited the hallmark structural motifs of the CDCs, which suggests that it is an authentic CDC. The undecapeptide of the putative O. formigenes CDC shows the greatest degree of variation in this motif reported to date, and it most closely resembles the undecapeptides found in the Trueperella pyogenes (formerly Arcanobacterium pyogenes) CDC, pyolysin (25), and the ILY-like CDCs (21, 26, 27).

The mRNAs for DLY and ELY were expressed throughout the growth cycles of D. propionicus and E. lignolyticus although no hemolytic activity was detected in either the culture supernatant or within the cell cytoplasm of either organism. The fact that the mRNAs were present suggests that the block in production occurs at the level of translation. Hence, DLY and ELY protein expression may occur only under specific conditions where the necessary environmental signals are present, which were not met in the laboratory cultures. If these toxins are used in defense against eukaryotic predators, then their rapid expression from preexisting mRNA may be necessary. It is possible that they are rapidly degraded after expression, but this seems less likely as it would be unnecessarily wasteful, especially for an organism like D. propionicus that feeds on energy-poor substrates.

Unlike the structures of the majority of the Gram-positive bacteria-derived CDCs, the DNA-deduced structures of ELY and DLY did not contain a type II signal peptide. Therefore, their export from the bacterial cell must occur via an alternative mechanism as it is unlikely that a cholesterol-binding, pore-forming toxin would remain at an intracellular location in the bacterial cell. Pneumolysin (PLY), the CDC from Streptococcus pneumoniae, also lacks a type II signal peptide. In one study its release was shown to coincide with the lysis of the cell (28), but more recent evidence suggests that PLY is specifically transported to the exterior of the cell (29, 30) by a secretion mechanism that has yet to be identified. Whether DLY and ELY are released from the cell by lysis or by a specific secretion system remains to be determined.

Phylogenetic analysis showed that DLY, ELY, and OLY are not members of the major clades of CDCs from species of the Firmicutes and Actinobacteria (Fig. 1). The codon usage of the CDC genes also matched that of their respective bacterial genomes, which suggests they were not recent acquisitions from another source. The similarity in their function and primary structures with the known CDCs, however, clearly shows that these proteins share a common origin. Evolutionarily related toxins are rarely identified in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial species; the only exception (that we know of) is that of Aeromonas hydrophila aerolysin and Clostridium septicum alpha-toxin, which are also pore-forming toxins that exhibit similar structures and mechanisms (31). Both of these organisms inhabit soil environments and cause soft tissue infections, which likely provided opportunities for the two species to exchange genetic material. Many of the species in the Firmicutes that produce CDCs are also primarily inhabitants of the soil (e.g., Bacillus and Clostridium species) but occasionally cause disease in humans and/or animals. It is possible that the CDC gene was transferred between soil inhabitants, rather than diverging from a common ancestral gene before the evolutionary divergence of cells with Gram-positive and Gram-negative cell structures.

In contrast to the CDCs from the Gram-positive bacteria, which are produced by many pathogens and opportunistic pathogens, the CDC gene is conspicuously absent from the Gram-negative pathogens. There are species of Enterobacter and Desulfobulbus that are opportunistic pathogens or commensals in humans (32–35), yet those species do not contain a gene that encodes a CDC. The CDC gene may have been previously tried and abandoned by the Gram-negative pathogens, or, more ominously, they may not have yet made their way to the Gram-negative pathogens.

Why do E. lignolyticus and D. propionicus maintain a CDC gene, given the nature of their environmental niches in anaerobic soils and sediments? Several Gram-positive pathogens have been shown to utilize their CDCs to prevent phagocytosis or to escape after phagocytosis by immune cells during an infection (3, 4, 36, 37). Ciliates and amoebas are responsible for significant depletion of bacterial numbers in aquatic and soil environments, and many are primarily bacterial predators (38–40). Some protozoa exhibit a facultative or strict anaerobic metabolism and require specific nutrients that are derived only from bacterial predation (41, 42). Therefore, bacteria may have initially utilized CDCs as a means of defense against eukaryotic predation and then later successfully adapted them to escape phagocytosis and destruction by phagocytic cells of the immune system.

Many protozoa contain cholesterol in their membranes (43–45), which serves as a receptor for most CDCs, including ELY and DLY. The binding affinities of rDLY and rELY were approximately 10-fold higher for cholesterol-rich liposomes than the binding affinity exhibited by PFO. We along with other investigators have previously shown that the lipid environment of the cholesterol has a significant impact on CDC binding (46, 47), as does the structure of the membrane-interactive tip of domain 4 (17, 48). Therefore, the differences observed in the binding of rDLY and rELY to the liposome membranes may reflect differences in these domain 4 structures that have evolved to bind cholesterol, or another appropriate sterol, in the lipid environment of protozoan membranes, which differ significantly from those of human or animal cells (45).

These studies show for the first time that functional CDCs are present in Gram-negative bacterial species, which are considered to be exclusive inhabitants of anaerobic soils or sediments. By analogy to the antiphagocytic roles of the CDCs produced by pathogens, we suggest that the expression of ELY and DLY is related to the bacteria's ability to survive protozoan predation in the soil and aquatic environments. Hence, CDCs may have initially evolved to fend off bacterial predators and were later adapted by pathogens to escape phagocytosis by cells of the immune system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The excellent technical assistance of P. Parrish is appreciated. We also thank D. Dyer for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, NIAID, to R.K.T. (5R01AI037657-16). Quantitative PCR analysis was supported by the Department of Energy, contract number DE-FG02-96ER20214 (M.J.M.), from the Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 31 October 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Hotze EM, Tweten RK. 2012. Membrane assembly of the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin pore complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1818:1028–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Madden JC, Ruiz N, Caparon M. 2001. Cytolysin-mediated translocation (CMT): a functional equivalent of type III secretion in Gram-positive bacteria. Cell 104:143–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Portnoy DA, Jacks PS, Hinrichs DJ. 1988. Role of hemolysin for the intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Exp. Med. 167:1459–1471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O'Brien DK, Melville SB. 2004. Effects of Clostridium perfringens alpha-toxin (PLC) and perfringolysin O (PFO) on cytotoxicity to macrophages, on escape from the phagosomes of macrophages, and on persistence of C. perfringens in host tissues. Infect. Immun. 72:5204–5215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Awad MM, Ellemor DM, Boyd RL, Emmins JJ, Rood JI. 2001. Synergistic effects of alpha-toxin and perfringolysin O in Clostridium perfringens-mediated gas gangrene. Infect. Immun. 69:7904–7910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pagani I, Lapidus A, Nolan M, Lucas S, Hammon N, Deshpande S, Cheng JF, Chertkov O, Davenport K, Tapia R, Han C, Goodwin L, Pitluck S, Liolios K, Mavromatis K, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Pati A, Chen A, Palaniappan K, Land M, Hauser L, Chang YJ, Jeffries CD, Detter JC, Brambilla E, Kannan KP, Djao OD, Rohde M, Pukall R, Spring S, Goker M, Sikorski J, Woyke T, Bristow J, Eisen JA, Markowitz V, Hugenholtz P, Kyrpides NC, Klenk HP. 2011. Complete genome sequence of Desulfobulbus propionicus type strain (1pr3). Stand. Genomic Sci. 4:100–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deangelis KM, D'Haeseleer P, Chivian D, Fortney JL, Khudyakov J, Simmons B, Woo H, Arkin AP, Davenport KW, Goodwin L, Chen A, Ivanova N, Kyrpides NC, Mavromatis K, Woyke T, Hazen TC. 2011. Complete genome sequence of “Enterobacter lignolyticus” SCF1. Stand. Genomic Sci. 5:69–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Widdel F, Pfennig N. 1981. Studies on dissimilatory sulfate-reducing bacteria that decompose fatty acids. I. Isolation of new sulfate-reducing bacteria enriched with acetate from saline environments. Description of Desulfobacter postgatei gen. nov., sp. nov. Arch. Microbiol. 129:395–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lovley DR, Phillips EJ. 1994. Novel processes for anaerobic sulfate production from elemental sulfur by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:2394–2399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dar SA, Stams AJ, Kuenen JG, Muyzer G. 2007. Co-existence of physiologically similar sulfate-reducing bacteria in a full-scale sulfidogenic bioreactor fed with a single organic electron donor. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 75:1463–1472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shepard LA, Heuck AP, Hamman BD, Rossjohn J, Parker MW, Ryan KR, Johnson AE, Tweten RK. 1998. Identification of a membrane-spanning domain of the thiol-activated pore-forming toxin Clostridium perfringens perfringolysin O: an α-helical to β-sheet transition identified by fluorescence spectroscopy. Biochemistry 37:14563–14574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shepard LA, Shatursky O, Johnson AE, Tweten RK. 2000. The mechanism of assembly and insertion of the membrane complex of the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin perfringolysin O: formation of a large prepore complex. Biochemistry 39:10284–10293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tanner RS. 1997. Cultivation of bacteria and fungi, p 52–60 In Hurst CJ, Knudsen GR. (ed), Manual of environmental microbiology. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pfaffl MW. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45 doi:10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tweten RK. 1988. Nucleotide sequence of the gene for perfringolysin O (theta-toxin) from Clostridium perfringens: significant homology with the genes for streptolysin O and pneumolysin. Infect. Immun. 56:3235–3240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ramachandran R, Tweten RK, Johnson AE. 2004. Membrane-dependent conformational changes initiate cholesterol-dependent cytolysin oligomerization and intersubunit β-strand alignment. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:697–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Farrand AJ, LaChapelle S, Hotze EM, Johnson AE, Tweten RK. 2010. Only two amino acids are essential for cytolytic toxin recognition of cholesterol at the membrane surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:4341–4346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Polekhina G, Giddings KS, Tweten RK, Parker MW. 2005. Insights into the action of the superfamily of cholesterol-dependent cytolysins from studies of intermedilysin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:600–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rossjohn J, Feil SC, McKinstry WJ, Tweten RK, Parker MW. 1997. Structure of a cholesterol-binding thiol-activated cytolysin and a model of its membrane form. Cell 89:685–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guex N, Peitsch MC. 1997. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18:2714–2723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wickham SE, Hotze EM, Farrand AJ, Polekhina G, Nero TL, Tomlinson S, Parker MW, Tweten RK. 2011. Mapping the intermedilysin-human CD59 receptor interface reveals a deep correspondence with the binding site on CD59 for complement binding proteins C8α and C9. J. Biol. Chem. 286:20952–20962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Czajkowsky DM, Hotze EM, Shao Z, Tweten RK. 2004. Vertical collapse of a cytolysin prepore moves its transmembrane β-hairpins to the membrane. EMBO J. 23:3206–3215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shatursky O, Heuck AP, Shepard LA, Rossjohn J, Parker MW, Johnson AE, Tweten RK. 1999. The mechanism of membrane insertion for a cholesterol dependent cytolysin: a novel paradigm for pore-forming toxins. Cell 99:293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stewart CS, Duncan SH, Cave DR. 2004. Oxalobacter formigenes and its role in oxalate metabolism in the human gut. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 230:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Billington SJ, Jost BH, Cuevas WA, Bright KR, Songer JG. 1997. The Arcanobacterium (Actinomyces) pyogenes hemolysin, pyolysin, is a novel member of the thiol-activated cytolysin family. J. Bacteriol. 179:6100–6106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gelber SE, Aguilar JL, Lewis KL, Ratner AJ. 2008. Functional and phylogenetic characterization of vaginolysin, the human-specific cytolysin from Gardnerella vaginalis. J. Bacteriol. 190:3896–3903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Giddings KS, Zhao J, Sims PJ, Tweten RK. 2004. Human CD59 is a receptor for the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin intermedilysin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:1173–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Benton KA, Paton JC, Briles DE. 1997. Differences in virulence for mice among Streptococcus pneumoniae strains of capsular types 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 are not attributable to differences in pneumolysin production. Infect. Immun. 65:1237–1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Balachandran P, Hollingshead SK, Paton JC, Briles DE. 2001. The autolytic enzyme LytA of Streptococcus pneumoniae is not responsible for releasing pneumolysin. J. Bacteriol. 183:3108–3116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Price KE, Camilli A. 2009. Pneumolysin localizes to the cell wall of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 191:2163–2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ballard J, Crabtree J, Roe BA, Tweten RK. 1995. The primary structure of Clostridium septicum alpha toxin exhibits similarity with Aeromonas hydrophila aerolysin. Infect. Immun. 63:340–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Colombo AP, Boches SK, Cotton SL, Goodson JM, Kent R, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS, Hasturk H, Van Dyke TE, Dewhirst F, Paster BJ. 2009. Comparisons of subgingival microbial profiles of refractory periodontitis, severe periodontitis, and periodontal health using the human oral microbe identification microarray. J. Periodontol. 80:1421–1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gibson GR, Cummings JH, Macfarlane GT. 1988. Use of a three-stage continuous culture system to study the effect of mucin on dissimilatory sulfate reduction and methanogenesis by mixed populations of human gut bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:2750–2755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gibson GR, Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH. 1988. Occurrence of sulphate-reducing bacteria in human faeces and the relationship of dissimilatory sulphate reduction to methanogenesis in the large gut. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 65:103–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dalben M, Varkulja G, Basso M, Krebs VL, Gibelli MA, van der Heijden I, Rossi F, Duboc G, Levin AS, Costa SF. 2008. Investigation of an outbreak of Enterobacter cloacae in a neonatal unit and review of the literature. J. Hosp. Infect. 70:7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Logsdon LK, Hakansson AP, Cortes G, Wessels MR. 2011. Streptolysin O inhibits clathrin-dependent internalization of group A Streptococcus. mBio 2(1):e00332–10 doi:10.1128/mBio.00332-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Awad MM, Bryant AE, Stevens DL, Rood JI. 1995. Virulence studies on chromosomal alpha-toxin and theta-toxin mutants constructed by allelic exchange provide genetic evidence for the essential role of alpha-toxin in Clostridium perfringens-mediated gas gangrene. Mol. Microbiol. 15:191–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sherr EB, Sherr BF. 2002. Significance of predation by protists in aquatic microbial food webs. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 81:293–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Habte M, Alexander M. 1977. Further evidence for the regulation of bacterial populations in soil by protozoa. Arch. Microbiol. 113:181–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pernthaler J. 2005. Predation on prokaryotes in the water column and its ecological implications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:537–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fritz-Laylin LK, Prochnik SE, Ginger ML, Dacks JB, Carpenter ML, Field MC, Kuo A, Paredez A, Chapman J, Pham J, Shu S, Neupane R, Cipriano M, Mancuso J, Tu H, Salamov A, Lindquist E, Shapiro H, Lucas S, Grigoriev IV, Cande WZ, Fulton C, Rokhsar DS, Dawson SC. 2010. The genome of Naegleria gruberi illuminates early eukaryotic versatility. Cell 140:631–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Loftus B, Anderson I, Davies R, Alsmark UC, Samuelson J, Amedeo P, Roncaglia P, Berriman M, Hirt RP, Mann BJ, Nozaki T, Suh B, Pop M, Duchene M, Ackers J, Tannich E, Leippe M, Hofer M, Bruchhaus I, Willhoeft U, Bhattacharya A, Chillingworth T, Churcher C, Hance Z, Harris B, Harris D, Jagels K, Moule S, Mungall K, Ormond D, Squares R, Whitehead S, Quail MA, Rabbinowitsch E, Norbertczak H, Price C, Wang Z, Guillen N, Gilchrist C, Stroup SE, Bhattacharya S, Lohia A, Foster PG, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Weber C, Singh U, Mukherjee C, El-Sayed NM, Petri WA, Jr, Clark CG, Embley TM, Barrell B, Fraser CM, Hall N. 2005. The genome of the protist parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Nature 433:865–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Williams BL, Goodwin TW. 1966. The sterol content of some protozoa. J. Protozool. 13:227–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sul D, Kaneshiro ES, Jayasimhulu K, Erwin JA. 2000. Neutral lipids, their fatty acids, and the sterols of the marine ciliated protozoon, Parauronema acutum. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 47:373–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Thompson GA, Jr, Nozawa Y. 1972. Lipids of protozoa: phospholipids and neutral lipids. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 26:249–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Flanagan JJ, Tweten RK, Johnson AE, Heuck AP. 2009. Cholesterol exposure at the membrane surface is necessary and sufficient to trigger perfringolysin O binding. Biochemistry 48:3977–3987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nelson LD, Johnson AE, London E. 2008. How interaction of perfringolysin O with membranes is controlled by sterol structure, lipid structure, and physiological low pH: insights into the origin of perfringolysin O-lipid raft interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 283:4632–4642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Johnson BB, Moe PC, Wang D, Rossi K, Trigatti BL, Heuck AP. 13 April 2012. Modifications in perfringolysin O domain 4 alter the cholesterol concentration threshold required for binding. Biochemistry. [Epub ahead of print.10.1021/bi3003132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bordoli L, Schwede T. 2012. Automated protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL Workspace and the Protein Model Portal. Methods Mol. Biol. 857:107–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Felsenstein J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nei M, Kumar S. 2000. Molecular evolution and phylogenetics. Oxford University Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. 2004. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophoton. Int. 11:36–42 [Google Scholar]