Abstract

In the last decade, the global emergence of carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae has posed great concern to public health. Data concerning the role of environmental contamination in the dissemination of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are currently lacking. Here, we aimed to examine the extent of CRE contamination in various sites in the immediate surroundings of CRE carriers and to assess the effects of sampling time and cleaning regimens on the recovery rate. We evaluated the performance of two sampling methods, CHROMAgar KPC contact plate and eSwab, for the detection of environmental CRE. eSwab was followed either by direct plating or by broth enrichment. First, 14 sites in the close vicinity of the carrier were evaluated for environmental contamination, and 5, which were found to be contaminated, were further studied. The environmental contamination decreased with distance from the patient; the bed area was the most contaminated site. Additionally, we found that the sampling time and the cleaning regimen were critical factors affecting the prevalence of environmental CRE contamination. We found that the CHROMAgar KPC contact plate method was a more effective technique for detecting environmental CRE than were eSwab-based methods. In summary, our study demonstrated that the vicinity of patients colonized with CRE is often contaminated by these organisms. Using selective contact plates to detect environmental contamination may guide cleaning efficacy and assist with outbreak investigation in an effort to limit the spread of CRE.

INTRODUCTION

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) have become a major threat to public health worldwide (1–3). These organisms are spreading globally, primarily in the health care setting. Physical separation by isolating carriers and dedicated staff resulted in containing CRE outbreaks (4). Hospital environments contaminated by infected patients may serve as a source for the spread of these bacteria, either directly or indirectly via health care personnel (5, 6). However, the actual presence of environmental contamination by CRE has not been studied.

Detection of contamination of the health care environment requires specialized methods that were mainly studied for various Gram-positive organisms, such as Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus species, and Clostridium difficile (7–9). No standardized methods of CRE environmental culture have been developed. Thus, the aims of our work were to show the presence of environmental contamination by CRE, to identify the sites that are likely to be contaminated, to evaluate the performance of different environmental culturing methods for recovery of environmental CRE (eCRE), and to evaluate the effects of various parameters on the recovery rate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting and patient selection.

The study was conducted as part of an ongoing surveillance program that had been implemented at the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (TASMC), a 1,200-bed tertiary care hospital in Tel Aviv, Israel. From December 2010 through May 2011, cultures were collected from the environment of 29 Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing CRE carriers, on 2 separate internal medicine wards. Five patients were sampled twice at different time points at intervals of approximately 3 months. Therefore, we referred to a total of 34 patients who were sampled during this study. Environmental samples were collected twice per each patient's sampling: in the morning and at noon, 24 and 4 h after rooms were cleaned and patient clothes and sheets were changed, respectively.

Environmental sampling design.

Environmental sampling was coordinated and supervised by the Infection Control Program at TASMC. An initial preliminary study was performed in order to determine the sampling sites for CRE (detailed in Results). After the preliminary study, five sampling sites surrounding each CRE-colonized patient were chosen for eCRE sampling: sheet surfaces around the pillow, crotch, and legs; the personal bedside table; and the infusion pump (20/34 patients). In each ward tested, samples were also taken from an unoccupied bed, to evaluate for nonspecific environmental contamination. Environmental samples were immediately (within 30 min) transferred to the laboratory for further workup.

Cultivation methods for environmental samples.

Two environmental sampling methods were compared for the recovery of eCRE: (i) direct application of CHROMAgar KPC contact plates supplemented with 0.7 g/liter lecithin and 4.5 ml/liter Tween 80 (CP; HyLabs, Rehovot, Israel) and surface sampling by eSwab (ES; Copan Diagnostics, Italy), either (ii) followed by direct streaking on CHROMAgar KPC plates (HyLabs, Israel) or (iii) following enrichment in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (ESBB).

Sampling was performed as follows. (i) CP-CHROMAgar KPC contact plates (5-cm diameter,19.625-cm2 area) were pressed to the tested surface for 3 to 5 s and then incubated at 37°C for 48 h. (ii) For ES, the eSwab was moved at right angles up and down within a 10- by 10-cm area defined by a sterile square template frame for approximately 1 min. The swab was then placed in the eSwab fluid-containing tube and transported to the lab. After 1-min vortexing at maximum speed, 200 μl of the suspension was spread onto a CHROMAgar KPC plate and placed for incubation at 37°C for 48 h. (iii) For ESBB, environmental sampling was performed as described for ES followed by an enrichment step in which 50 μl of the eSwab medium was inoculated into 3 ml of BHI broth and incubated at 37°C with shaking at 150 rpm for 48 h. Subsequently, approximately 10 μl of the broth was spread with cotton-tipped applicators on a CHROMAgar KPC plate, which was then incubated at 37°C for 48 h.

Characterization of CRE from patients and environmental culture.

Detection and identification of CRE in patients were done as previously described (10, 11). Identification of eCRE colonies was performed based on growth characteristics on CHROMAgar KPC according to the manufacturer's instructions (Klebsiella and Enterobacter species, medium-size dark metallic blue colonies; Escherichia coli, medium to large pink/dark rose colonies). Blue and pink colonies were tested by blaKPC PCR (11) and further confirmed using the Vitek 2 system (bioMérieux).

Data analysis.

Bivariate analysis of categorical variables was done using the χ2 test. Analyses were done using the JMP IN v3.2.1 software (SAS Institute Inc.).

RESULTS

Identification of sites contaminated with eCRE.

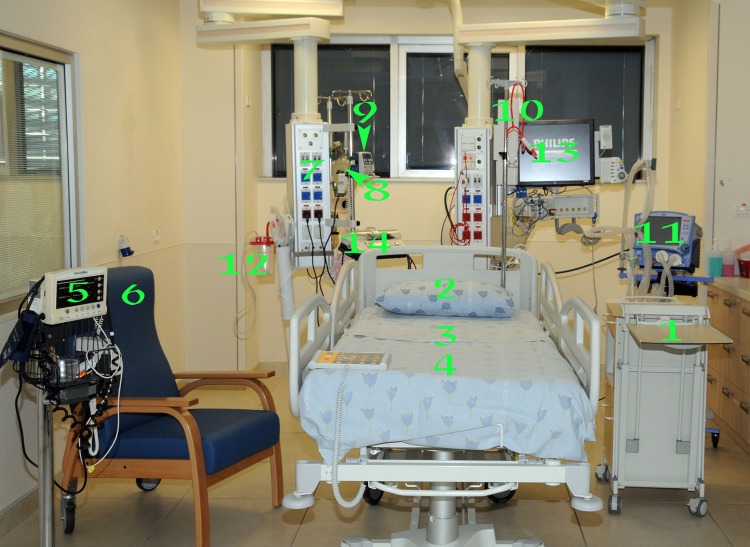

We first sought to identify the environmental sites that were contaminated in the vicinity of the CRE carriers. Fourteen sites were surveyed 6 times for eCRE using CHROMAgar KPC contact plates: bed linen around the head (pillow), crotch, and legs; personal bedside table; infusion pump; personal chair; dedicated stethoscope; electrical outlet line; suction machine; respirator; cardiovascular monitor screen; pulse oximeter; manual respirator bag; and enteral feeding pump (Fig. 1). eCRE were identified in only 5 of the 14 sites sampled: sheet surfaces around the pillow, crotch, and legs; personal bedside table; and infusion pump. Based on these preliminary data, these sites were further tested in our study.

Fig 1.

Locations of testing for environmental CRE (eCRE). 1, personal bedside table; 2 to 4, bed linen around the pillow (2), crotch (3), and legs (4); 5, pulse oximeter; 6, personal bedside chair; 7, electrical outlet line; 8, manual respirator bag; 9, infusion pump; 10, dedicated stethoscope; 11, ventilator; 12, suction machine; 13, cardiovascular monitor screen; 14, enteral feeding pump.

Five empty beds from the two wards were surveyed for eCRE contamination, to test for nonspecific contamination. None of them were found to be contaminated with eCRE.

Recovery of eCRE using each sampling method.

Nine hundred twenty-eight environmental samples were collected in this study from the vicinity of 34 known KPC-producing CRE carriers using the 3 different sampling methods—CP, ES, and ESBB. Five sites were sampled from each carrier, except for the infusion pump, which was present in the surroundings of 20/34 patients. One patient was not sampled around the legs, and two ESBB samples were accidentally discarded. A positive eCRE culture was identified at least once in 30/34 patients (88%).

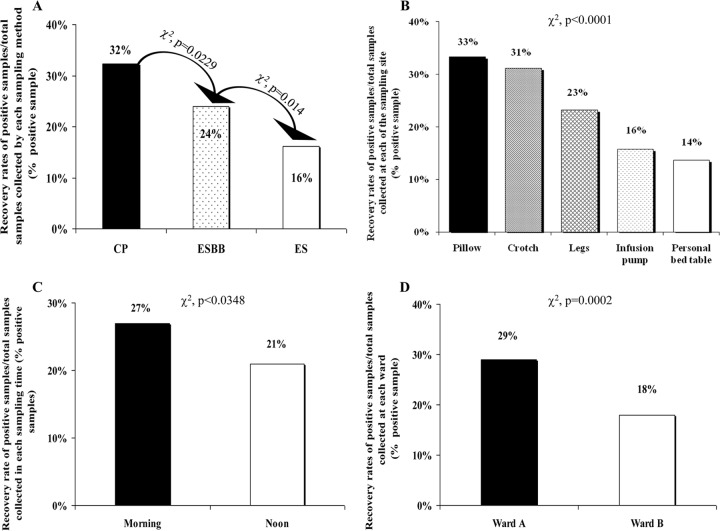

We evaluated the role of the following variables in the recovery rate of eCRE: the sampling and cultivation method, the sampling site, the time of sampling, and the ward. Of the 928 samples, 224 were positive for eCRE by any of the tested methods (24%). The recovery rates of the three sampling methods were 32%, 24%, and 16% for CP, ESBB, and ES, respectively (Fig. 2A).

Fig 2.

Recovery rates (% positive samples) of environmental CRE (eCRE) from the patients' surroundings. (A) The effect of the 3 sampling-cultivation methods on the recovery rate of eCRE. CP, CHROMAgar KPC contact plates; ES, eSwab sampling, direct plating onto CHROMAgar KPC plates; ESBB, eSwab sampling, broth enrichment prior to plating; (B) The recovery rates of eCRE from 5 different sites in the vicinity of the carriers: pillow, crotch, legs, personal bedside table, and infusion pump. (C) The effect of sampling time on the recovery rate of eCRE. Morning and noon samples were done before and 4 h after clothing and sheet replacement, respectively. (D) The recovery rate of eCRE from two wards at TASMC.

Recovery rates at different sampling sites.

The recovery rates of eCRE at the different sites were 68/204 (33%) at the pillow, 63/202 (31%) at the crotch, 46/198 (23%) at the legs, 19/120 (16%) at the infusion pump, and 28/204 (14%) at the personal bedside table (P < 0.0001; Fig. 2B). The distribution of these positive eCRE as a function of the sampling-cultivation method is shown in Table 1. The CP method was superior at the infusion pump and personal bedside table sites but was inferior to the eSwab sampling methods (ES and ESBB) at the pillow site (P > 0.05 for all) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Recovery of eCRE using different sampling methods and sampling sitesb

| eCRE sampling method | P valuea | No. of eCRE-positive samples/total positive samples recovered at the respective sampling site (% recovery) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pillow | Crotch | Legs | Personal bedside table | Infusion pump | ||

| CP | 0.1619 | 24/100 (24) | 29/100 (29) | 20/100 (20) | 16/100 (16) | 11/100 (11) |

| ES | 0.0011 | 19/50 (38) | 15/50 (30) | 10/50 (20) | 5/50 (10) | 1/50 (2) |

| ESBB | 0.0051 | 25/74 (34) | 19/74 (26) | 16/74 (22) | 7/74 (9) | 7/74 (9) |

The P value relates to the differences between sites for a particular sampling method.

CP, CHROMAgar KPC contact plates; ES, eSwab sampling, direct plating onto CHROMAgar KPC plates; ESBB, eSwab sampling followed by broth enrichment prior to plating.

Effect of routine cleaning and ward on recovery of eCRE.

In order to examine the effect of routine cleaning on the persistence of CRE in the environment, we sampled at two different time points during the day: in the morning and at noon, before and 4 h after clothing and sheet replacement, respectively. Four hundred sixty-five samples were collected in the morning, and 463 were collected at noon. In the morning, 126/465 (27%) of the samples tested positive for eCRE, whereas only 98/463 (21%) were positive at noon (P < 0.05; Fig. 2C).

Five hundred four environmental samples were collected from ward A and 424 were collected from ward B, from the vicinity of 18 and 16 patients, respectively. The recovery rates differed significantly—146/504 (29%) at ward A and 78/424 (18%) at ward B (P = 0.0002; Fig. 2D). We have examined the recovery rate data for eCRE at the different sampling sites in each ward. In only one site, the infusion pump, was the recovery rate of eCRE lower in ward A than in ward B (3% versus 18%, respectively, P = 0.0002), while at the leg site the recovery rate in ward A was higher than that in ward B (25% versus 13%, respectively; P = 0.0367).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we documented the contamination of the hospital environment, in the vicinity of KPC-producing CRE carriers. eCRE were detected in the surroundings of 88% of these patients. This finding has ominous implications regarding the ability of the environment to serve as a vector for transmission of CRE in the health care setting.

We identified several factors, both methodological and environmental, that significantly affect the retrieval rate of eCRE. First, we found that the sampling-cultivation method has great implications for the sensitivity of the sampling. We compared the performances of CHROMAgar contact plates (CP) and eSwabs (ES) as sampling tools. The CHROMAgar KPC medium was chosen based on a previous study of ours that showed its high performance in detecting KPC-producing CRE (10). The additive surface-active components (lecithin and Tween 80) were added to eliminate the effect of disinfectants present in the environment that may inhibit growth of microorganisms (12, 13). The eSwab was chosen thanks to its increased sensitivity that could be ascribed both to the flocculated characteristics and to the transport Amies solution, which acts as a nonselective fluid and facilitates sampling of bacteria (14). In addition to the 2 sampling methods, we also added an enrichment step that was compared with direct plating from the swab, in order to improve the recovery of slow-growing bacteria (15, 16).

All sampling methods, CP, ES with enrichment, and ES without enrichment, were able to recover CRE from the environment. Overall, the CP method was superior to ES despite the fact that a greater surface area was sampled by the swab (100 cm2) than by the contact plate (19.625 cm2). Our findings are in accordance with other studies, which observed a better recovery of environmental infectious bacteria with contact plates than with the swab method followed by a direct plating or enrichment step (17, 18), although this difference may vary according to the organism sought. Obee et al. (18) showed a higher recovery rate of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from a stainless steel table using methicillin contact plates than using a swab method. In contrast, Lemmen et al. (17) showed that Rodac plates were superior to the swab technique in detecting Gram-positive cocci, whereas the swab method exhibited higher performance in detecting Gram-negative rods. The authors also obtained improvement in the detection rate for Gram-negative bacteria by using an enrichment step after swab sampling.

Previous studies suggested several explanations for the shortcomings of the swab method in sampling the hospital surroundings for infectious bacteria. These include the following: damage to the bacterial cells during swabbing (18); adhesion of bacterial cells to the swab fabrics, which can then be trapped within the swab bud (14, 15, 19, 20); the amount of pressure being applied to the swab handle during swabbing, which can limit the number of bacteria collected from the surface (19); and the transport medium, which can affect bacterial survival (20, 21). Thus, it is possible that the lower recovery rates obtained by the swab method in our study might result from one or several of these factors.

We were able to improve significantly the recovery rate of the swab method (Fig. 2A) by applying an enrichment step prior to plating. This observation is in accordance with previous studies on various bacteria. Hallgren et al. (7) were able to obtain a significant increase in the detection sensitivity of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) from the environment using a selective broth enrichment step compared to direct plating.

Contamination by drug-resistant bacteria may be found on several surfaces, including the floor, the bed frame, the furniture, the patients' clothes, and the bed sheets (22). In the first part of our study, we identified 5 locations that are most likely to be contaminated—the bed surfaces, the infusion pump, and the personal table. We found that the detection rate of eCRE is reduced with increased distance from the carrier, with the bed surfaces being the most contaminated sites. This reduction is probably due to the fact that medical equipment and items at a distance from the patients are less exposed to hand touch or body secretions of CRE carriers. Similar findings were previously observed with different organisms. Dancer (23) reported that the bed linen, patients' gowns, and the over-bed table were the areas most contaminated with MRSA compared with other items such as the bed rails, bedside lockers, and infusion pumps. Similarly, Lemmen et al. (16) observed reduction in the detection rate of multiresistant Gram-positive bacteria with distance from the patients harboring these organisms. However, this trend was not observed for the Gram-negative bacteria.

The environmental surface being sampled may play a role in the detection efficiency of the different sampling methods. Several surface characteristics such as surface charge, topography, and hydrophobicity can affect the retrieval efficiency of the collection method. According to the work of Obee et al. (18), contact plates are effective in observing bacteria on flat and regular surfaces, while swabbing is sufficient for dry surfaces. Accordingly, in our study, the contact plate method was inferior to eSwab in detecting bacteria at the irregularly shaped pillow site, considered to be nonflat and less accessible for sampling, but was superior at the personal bedside table and infusion pump sites, which are flat and regular surfaces.

Two environmental factors were found to affect the recovery rate of eCRE. First, the time from cleaning to sampling was a significant factor. Although hardly surprising, it highlights the importance of frequent cleaning, especially in the vicinity of carriers of resistant bacteria, in order to reduce the potential of environment-related transmission. However, shortly after cleaning the patient's close vicinity is recontaminated. Furthermore, we were able to observe differences in the cleaning quality between ward A and ward B, as ward A was significantly more contaminated than ward B. This may be explained by factors such as the degree of crowdedness, the staff/patient ratio, and also differences in the infrastructure. The difference was especially pronounced in the recovery of eCRE from the bedside equipment (personal bedside table and infusion pump). As the two wards are at the same institution and sharing similar resources, it indicates the importance of attention by the ward management to meticulous cleaning routines. Also, it demonstrates the potential value of environmental cultures as a quality indicator tool in the health care setting.

In conclusion, the study performed in our hospital has shown the existence of CRE contamination in the patients' surroundings in different wards and the utility of different sampling-cultivation methods. It highlights the importance of standard cleaning regimens for surfaces and items in the patients' immediate surroundings and awareness of their role in CRE dissemination and transmission to other patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by European Commission FP7 SATURN-Impact of Specific Antibiotic Therapies on the Prevalence of Human Host Resistant Bacteria research grant 241796.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 31 October 2012

REFERENCES

- 1.Bilavsky E, Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y. 2010. How to stem the tide of carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae?: proactive versus reactive strategies. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 23:327–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordmann P, Cuzon G, Naas T. 2009. The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Lancet Infect. Dis. 9:228–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y. 2008. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a potential threat. JAMA 300:2911–2913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwaber MJ, Lev B, Israeli A, Solter E, Smollan G, Rubinovitch B, Shalit I, Carmeli Y, Israel Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Working Group 2011. Containment of a country-wide outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Israeli hospitals via a nationally implemented intervention. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:848–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Oliveira AC, Damasceno QS. 2010. Surfaces of the hospital environment as possible deposits of resistant bacteria: a review. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 44:1118–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.French GL, Otter JA, Shannon KP, Adams NM, Watling D, Parks MJ. 2004. Tackling contamination of the hospital environment by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): a comparison between conventional terminal cleaning and hydrogen peroxide vapour decontamination. J. Hosp. Infect. 57:31–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallgren A, Burman LG, Isaksson B, Olsson-Liljeqvist B, Nilsson LE, Saeedi B, Walther S, Hanberger H. 2005. Rectal colonization and frequency of enterococcal cross-transmission among prolonged-stay patients in two Swedish intensive care units. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 37:561–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mutters R, Nonnenmacher C, Susin C, Albrecht U, Kropatsch R, Schumacher S. 2009. Quantitative detection of Clostridium difficile in hospital environmental samples by real-time polymerase chain reaction. J. Hosp. Infect. 71:43–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sexton T, Clarke P, O'Neill E, Dillane T, Humphreys H. 2006. Environmental reservoirs of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in isolation rooms: correlation with patient isolates and implications for hospital hygiene. J. Hosp. Infect. 62:187–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adler A, Navon-Venezia S, Moran-Gilad J, Marcos E, Schwartz D, Carmeli Y. 2011. Laboratory and clinical evaluation of screening agar plates for detection of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae from surveillance rectal swabs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:2239–2242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schechner V, Straus-Robinson K, Schwartz D, Pfeffer I, Tarabeia J, Moskovich R, Chmelnitsky I, Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y, Navon-Venezia S. 2009. Evaluation of PCR-based testing for surveillance of KPC-producing carbapenem-resistant members of the Enterobacteriaceae family. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3261–3265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman H, Volin E, Laumann D. 1968. Terminal disinfection in hospitals with quaternary ammonium compounds by use of a spray-fog technique. Appl. Microbiol. 16:223–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnston MD, Lambert RJ, Hanlon GW, Denyer SP. 2002. A rapid method for assessing the suitability of quenching agents for individual biocides as well as combinations. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92:784–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolan A, Bartlett M, McEntee B, Creamer E, Humphreys H. 2011. Evaluation of different methods to recover meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from hospital environmental surfaces. J. Hosp. Infect. 79:227–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hakalehto E. 2006. Semmelweis' present day follow-up: updating bacterial sampling and enrichment in clinical hygiene. Pathophysiology 13:257–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemmen SW, Hafner H, Zolldann D, Stanzel S, Lutticken R. 2004. Distribution of multi-resistant Gram-negative versus Gram-positive bacteria in the hospital inanimate environment. J. Hosp. Infect. 56:191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemmen SW, Häfner H, Zolldann D, Amedick G, Lütticken R. 2001. Comparison of two sampling methods for the detection of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in the environment: moistened swabs versus Rodac plates. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 203:245–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obee P, Griffith CJ, Cooper RA, Bennion NE. 2007. An evaluation of different methods for the recovery of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from environmental surfaces. J. Hosp. Infect. 65:35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore G, Griffith C. 2002. A comparison of surface sampling methods for detecting coliforms on food contact surfaces. Food Microbiol. 19:65–73 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roelofsen E, van Leeuwen M, Meijer-Severs GJ, Wilkinson MH, Degener JE. 1999. Evaluation of the effects of storage in two different swab fabrics and under three different transport conditions on recovery of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3041–3043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perry JL. 1997. Assessment of swab transport systems for aerobic and anaerobic organism recovery. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1269–1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talon D. 1999. The role of the hospital environment in the epidemiology of multi-resistant bacteria. J. Hosp. Infect. 43:13–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dancer SJ. 2008. Importance of the environment in meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus acquisition: the case for hospital cleaning. Lancet Infect. Dis. 8:101–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]