Abstract

Although malaria remains one of the leading infectious diseases in the world, the decline in malaria transmission in some area makes it possible to consider elimination of the disease. As countries approach elimination, malaria diagnosis needs to change from diagnosing ill patients to actively detecting infections in all carriers, including asymptomatic and low-parasite-load patients. However, few of the current diagnostic methods have both the throughput and the sensitivity required. We adopted a sandwich RNA hybridization assay to detect genus Plasmodium 18S rRNA directly from whole-blood samples from Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax patients without RNA isolation. We tested the assay with 202 febrile patients from areas where malaria is endemic, using 20 μl of each blood sample in a 96-well plate format with a 2-day enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-like work flow. The results were compared with diagnoses obtained using microscopy, a rapid diagnostic test (RDT), and genus-specific real-time PCR. Our assay identified all 66 positive samples diagnosed by microscopy, including 49 poorly stored samples that underwent multiple freeze-thaw cycles due to resource limitation. The assay uncovered three false-negative samples by microscopy and four false-negative samples by RDT and agreed completely with real-time PCR diagnosis. There was no negative sample by our assay that would show a positive result when tested with other methods. The detection limit of our assay for P. falciparum was 0.04 parasite/μl. The assay's simple work flow, high throughput, and sensitivity make it suitable for active malaria screening.

INTRODUCTION

Accurate diagnosis of ill patients has been essential for malaria control programs aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality. As programs successfully reduce malaria transmission to low levels, malaria elimination is being considered (1, 2). However, detection of infection in elimination settings will become increasingly difficult since a substantial proportion of infections will be of low parasite load or even asymptomatic (3–6). To achieve elimination, malaria diagnosis needs to change from passively diagnosing ill patients in health facilities to actively detecting infections in all carriers in the community, who may or may not show clinical symptoms, as subclinically infected individuals can be significant sources of infection (7–10).

Current malaria diagnostic methods, however, lack the sensitivity or throughput needed for active malaria detection and surveillance in elimination settings. The most widely used microscopic examination is time-consuming and, being unable to detect infection of lower than 50 parasites/μl (11), can miss a substantial proportion of infections in surveys of populations in areas of endemicity, especially areas with low transmission of infection (12). The antibody-based rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), which are easy to perform, have improved sensitivities for Plasmodium falciparum infections and were proposed as a mass screening tool for malaria elimination (5). However, their sensitivities for other malaria species are often poorer than microscopy, and some cannot differentiate between active infection and past malaria experience (11). In a recent malaria survey in an elimination setting, RDT missed the majority of Plasmodium vivax infections while giving a number of false-positive results for P. falciparum infection (4), indicating that RDT is not appropriate for general malaria screening. Molecular methods, such as PCR (13), quantitative PCR (qPCR) (14), reverse transcription-PCR (15), nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA) (16), and loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) (17), are more sensitive than microscopy and RDT, yet their dependence on DNA/RNA extraction can strongly influence the performance of the diagnosis (14, 16, 17), and in surveillance settings, DNA/RNA extraction can be labor-intensive to perform on large numbers of samples. Importantly, when performed in parallel on 96-well plates, the target amplification nature of these methods, even those with closed systems such as real-time PCR, requires a very high standard of laboratory practice to avoid contamination that leads to false-positive results, restricting their application to well-equipped laboratories with specially trained technicians (18). To date an appropriate diagnostic method suitable for active malaria diagnosis and surveillance in low-transmission settings remains to be developed.

There are at least three hurdles for malaria elimination that need to be urgently addressed. The first is that without sensitive and reliable diagnostic tests and accurate estimates of community prevalence, clinicians often respond to negative results of tests for malaria by ignoring them, and overprescription of antimalarial drugs is prevalent (19). At some low-transmission sites, fewer than 1% of patients treated with an antimalarial drug had malaria parasites in their blood (20). This overdiagnosis of malaria in health care facilities coexists with underdiagnosis of malaria in the community, with the result that antimalarials are given to people who do not need them and are not given to those who do (21). This situation will have to be changed if more effective but also more expensive drugs, such as artemisinin combination therapy, are to be introduced to control or eliminate the disease (5), as cost-effectiveness rapidly falls away at high levels of misdiagnosis (22) and drug resistance may arise. The second problem is that without reliable active population screening, malaria surveillance programs which measure only clinical illness will provide inaccurate pictures of the prevalence of parasitemia and probability of transmission as countries approach elimination (4, 23), resulting in unreliable modeling of risks, costs and benefits, and feasibility of eliminating and maintaining elimination, ultimately affecting the commitment to the elimination policy (1, 2, 24). A final problem is that, without an effective high-throughput assay to screen a large number of at-risk travelers and migrants, most of whom are asymptomatic, malaria can easily reemerge in regions that have already achieved elimination (18). It is therefore evident that a sensitive and high-throughput diagnostic assay plays a central and critical role in elimination programs.

We have sought to develop an easy, sensitive, and reliable molecular assay suitable for large-scale malaria screening by adopting our previously developed sandwich RNA hybridization assay, which uses an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-like work flow in a 96-well format without RNA purification, reverse transcription, and target amplification (25). The sandwich hybridization assay is done with a series of oligonucleotide probes containing target-specific sequences and an additional “tail” sequence that is independent of the target sequence but can interact with either the solid support or the detection system. These probes are called capture extenders (CEs) and label extenders (LEs), respectively. The probes bind a contiguous or near-contiguous region of the target RNA. The CEs bind to the capture oligonucleotides conjugated to the surface of each well in 96-well plate and, via cooperative hybridization, capture the associated target RNA. Signal amplification is mediated by DNA amplification molecules that hybridize to the tails of the LEs, and the DNA amplification molecules can then be detected by a chemiluminescent reaction (25).

In this study, we demonstrated the assay for the direct detection of genus Plasmodium 18S rRNA in whole-blood samples from P. falciparum and P. vivax patients. Results from the assay were compared with those using microscopy, an RDT method, and genus-specific real-time PCR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection.

Venous heparin blood samples were collected from 202 patients with fever of unknown origin in Kachine, Myanmar, and in Yunnan, China. Among them, 49 were collected in 2008 and 153 were collected in 2011. Control blood samples (n = 13) used for analytical evaluation were taken from healthy subjects in Beijing, China. All samples were frozen and stored at −80°C before use. Samples were collected with written informed consent. Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. Due to limited resources, the 49 blood samples collected in 2008 had suffered several freeze-and-thaw cycles before the test.

Diagnosis by microscopy.

At the time of admission, 2 slides, each containing a thick and a thin blood film, were collected from each patient and stained with 2% Giemsa stain solution for 30 min. The slides were then examined independently by two professional microscopists for Plasmodium parasites, and parasitemia was determined by counting the number of asexual parasites and the number of leukocytes, using a putative mean count of 8,000 leukocytes per μl (26). Samples were pronounced negative only when a minimum of 100 fields had been carefully examined by each microscopist for the absence of parasites.

Diagnosis by RDT.

The RDTs in this study were done with Carestart (Accessbio, Monmouth Junction, NJ) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The kit is among the list of RDT procurement recommendations issued by WHO (27).

Diagnosis by real-time qPCR.

DNA was extracted from 200 μl of thawed blood with the QIAamp DNA Blood Minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The genus Plasmodium 18S rRNA screening primer and probe sequences and real-time qPCR conditions were adopted from previously published work (14). If the fluorescent signal did not increase within 40 cycles (threshold cycle [CT], 40), the sample was considered negative (14). At least one positive control and one negative control were included to each experiment. Each sample was tested in duplicate.

Diagnosis by RNA hybridization assay.

To develop an assay that can be used as an initial screening tool for malaria, we designed a set of 22 oligonucleotide probes (probe sequences available upon request) according to previously described principles (28), targeting several highly conserved regions in 18S rRNA of the genus Plasmodium, including P. falciparum (GenBank accession number M19172.1), P. vivax (U03079.1), P. malariae (AF488000.1), P. ovale (L48987.1), and P. knowlesi (L07560.1). For each assay, 20 μl of fresh or thawed blood or erythrocyte culture of P. falciparum was lysed with 50 μl of lysis mixture (Panomics/Affymetrix), 28 μl of water, and 2 μl of 50-mg/ml proteinase K at 60°C for 1 h with vigorous shaking. The lysates were mixed with probes and hybridized to a capture plate by incubation at 58°C overnight without shaking (25). After the unbound probes were washed off, captured targets were sequentially hybridized, with washing in between, with preamplifier, amplifier, label probe, and substrate as described in the Quantigene assay kit (Panomics/Affymetrix). The resulting chemiluminescence was quantified in a Modulus plate reader (Turner Biosciences) as previously described (25). For malaria diagnosis, the background signal from the blank control was subtracted from the sample signal to obtain the net signal, and samples with net signals above the detection threshold (3 times the standard deviation [SD] of the blank control) were diagnosed as positive, while those with net signals below the detection threshold were diagnosed as negative. Each sample was tested in duplicate. Erythrocytes were used as the blank control for determining the detection limit. For testing blood of healthy volunteers, water was used as the blank control, and for clinical samples, the blood of healthy volunteers was used as the blank control.

RESULTS

Analytical performance of the RNA hybridization assay.

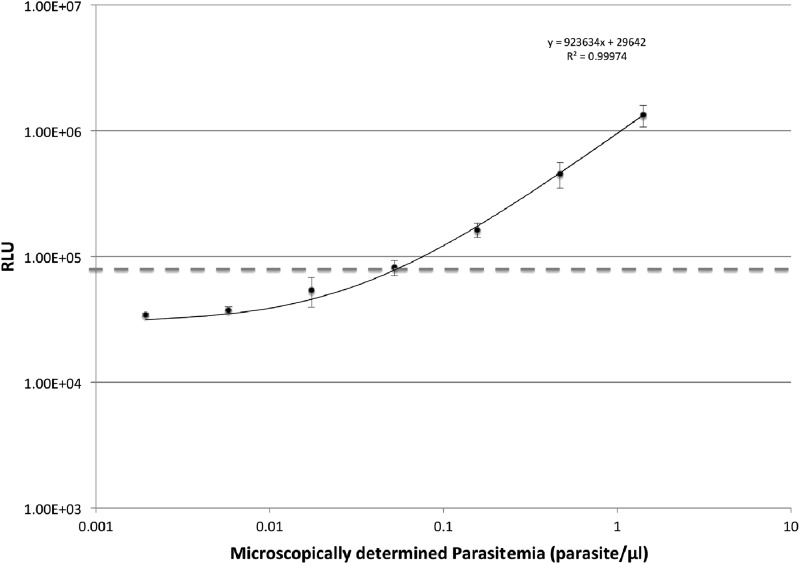

We tested a 3-fold serial dilution of fresh human erythrocyte-cultured Plasmodium falciparum. The limit of detection was determined as the minimal amount of erythrocyte-cultured Plasmodium falciparum (isolate 3D7) added to the erythrocytes that gave a net signal above three times the SD of the background erythrocyte control. The assay gave a detection limit of about 0.04 parasite/μl, with signals above the threshold proportional to parasite numbers (r2 = 0.999) (Fig. 1), indicating that our assay is highly sensitive and is able to detect low parasitemia in intact samples. All whole-blood samples collected from healthy volunteers (n = 13) were negative, using water as a background control.

Fig 1.

Correlation of assay signal with cultured Plasmodium falciparum parasitemia in human erythrocytes. Parasitemia in human erythrocyte culture was determined based on infection rate (number of infected red blood cells [RBCs]/number of infected plus uninfected RBCs [n = 1,000]) and RBC concentration The limit of detection was determined as the minimal amount of cultured plasmodia added to the erythrocytes that gave a net signal above three times the SD of the background erythrocyte control (dashed line). Each dilution was prepared using culture medium. Triplicate samples were used in the assay, and the data are representative of three independent runs. The average limit of detection was 0.04 parasite/μl blood. RLU, relative light units.

Microscopy examination of blood samples.

A total of 202 clinical blood samples from 202 febrile patients with fever of undetermined cause were collected and examined by microscopy. After confirmation by independent experts, 66 were diagnosed as positive (P. falciparum [n = 27] or P. vivax [n = 39]), with parasitemia ranging from 320 parasites/μl to 6 × 105 parasites/μl, while the remaining 136 samples were microscopy negative (Table 1). Among these microscopy-negative samples, real-time qPCR and RNA hybridization assay consistently detected three infections, while RDT found only two of them (Table 2). The remaining 133 microscopy-negative samples were confirmed by all three other methods in our study.

Table 1.

Results of microscopy, RDT, real-time qPCR, and RNA hybridization assay

| Method (no. of samples) | Result | No. of samples (n = 202) with RNA hybridization assay result: |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n = 69) | Negative (n = 133) | ||

| Microscopy (202) | Positive | 66a | 0 |

| Negative | 3 | 133 | |

| RDT (143) | Positive | 6 | 0 |

| Negative | 4 | 133 | |

| Real-time qPCR (152) | Positive | 19 | 0 |

| Negative | 0 | 133 | |

Includes 27 samples with Plasmodium falciparum and 39 samples with Plasmodium vivax.

Table 2.

Samples with discrepancies among four methods

| Sample | Result by: |

CT of real-time qPCR (mean ± SD) | Mean net RLU in RNA hybridization assay (P value)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | RDT | |||

| 1 | Negative | Negative | 34.78 ± 0.05 | 4.34E+06 (0.0183) |

| 2 | Negative | P. falciparum | 32.63 ± 0.24 | 8.03E+05 (0.0253) |

| 3 | Negative | P. falciparum | 37.87 ± 1.22 | 2.99E+04 (0.0021) |

| 4 | P. vivax | Negative | 20.95 ± 0.66 | 6.05E+06 (0.0002) |

| 5 | P. vivax | Negative | 21.34 ± 0.51 | 8.65E+06 (0.0090) |

| 6 | P. vivax | Negative | 26.66 ± 1.47 | 1.81E+06 (0.0144) |

The RLU detection threshold for the RNA hybridization assay is 9.11E+03 (3 times the SD).

Performance of rapid diagnostic test.

For the 143 samples collected in 2011, we used the Carestart Malaria HRP2/pLDH combo kit for diagnosis (Table 1). The RDT detected three P. falciparum and three P. vivax infections, including two P. falciparum infections that were missed by microscopy. All positive RDT results were confirmed by both real-time qPCR and RNA hybridization assay. Four RDT-negative samples were positive in both real-time qPCR and the RNA hybridization assay. Three out of these four RDT-negative samples were diagnosed as having P. vivax infection by microscopy (Table 2).

Performance of RNA hybridization assay.

Our assay, performed on 96-well plates through a 2-day ELISA-like work flow, identified all 66 microscopy-positive samples (Table 1). Blood samples from healthy volunteers were used as the background control. There was no apparent difference between detection of P. falciparum infection and P. vivax infection. Although an overnight incubation was required, the overall hands-on time for the assay was less than 2 h, as the samples were assayed in parallel. The blood lysates for this assay can be stored at −20°C with stability for at least 6 months (data not shown). These results suggest that the assay is sufficient for high-throughput qualitative detection of malaria infection in a large number of samples. There were three microscopy-negative samples that showed positive in our assay. All three of these samples were positive in real-time qPCR, and two of them were also positive in RDT (Table 2).

Confirmation by real-time qPCR.

Whenever possible we tested all available clinical blood samples with real-time qPCR. Among the 202 patient samples, 50 samples that were diagnosed as positive by both microscopy and RNA hybridization assay had an insufficient amount for DNA extraction and real-time qPCR tests. The results for the remaining 152 samples had no discrepancy with the RNA hybridization assay; all 19 samples positive in the RNA hybridization assay also were positive in real-time qPCR, while all 133 RNA hybridization-negative samples were also negative in real-time qPCR (Table 1). Finally, for six samples that showed discrepancies among microscopy, RDT, qPCR, and RNA hybridization assay results, we repeated both qPCR (including DNA extraction) and our RNA hybridization assay twice for confirmation, with consistent results (Table 2). Thus, using real-time qPCR results as the reference standard, the RNA hybridization assay obtained 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity for this sample set.

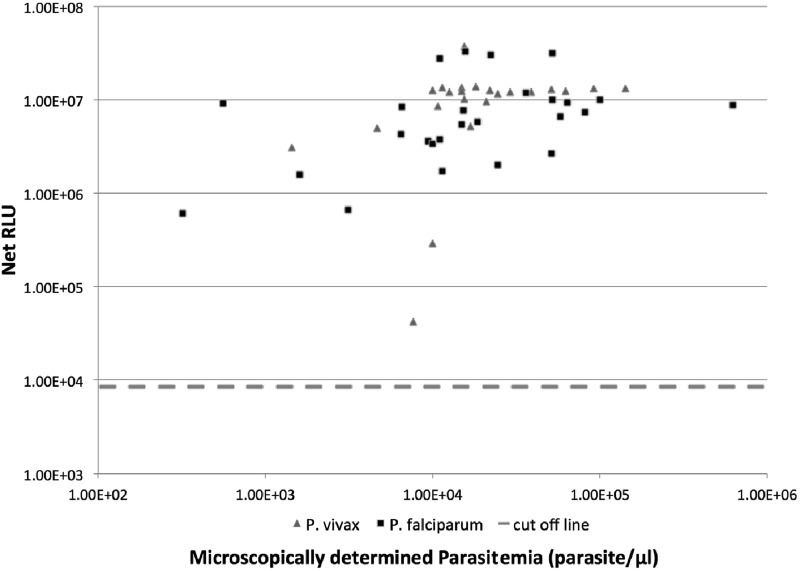

Assay robustness.

To test for the assay's robustness and to determine if the assay is capable of diagnosing samples of suboptimal quality, we examined the assay results for the 49 malaria samples collected in 2008 (with parasitemia ranging from 320 parasites/μl to 6 × 105 parasites/μl) that were poorly stored and likely partially degraded. These samples were microscopy positive and included both P. falciparum samples and P. vivax samples that underwent repeated freeze-thaw cycles during storage. Signals from all 49 patient samples were above the detection threshold, and a majority of them approached detection saturation (Fig. 2), despite the fact that the samples may have suffered from RNA degradation. The assay had a mean intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) of 5%.

Fig 2.

Correlation between assay signal and parasitemia for poorly stored blood samples. Stored blood samples from 49 patients, which underwent multiple freeze-and-thaw cycles after collection due to limited resources, were assayed (20 μl each), and the net signals were plotted against parasitemia determined microscopically at admission. Each sample was assayed in duplicate, and the average signal was used. Signal intensities beyond 1 × 107 RLU were considered approaching detection saturation of the photon detector.

DISCUSSION

As countries approach malaria elimination, both diagnosis and disease surveillance activities will need to shift from controlling morbidity and mortality to detecting infections and measuring transmission. This calls for new diagnostic assays with higher sensitivity for detecting low-load infections and higher throughput for mass screening (18). In this study, we demonstrated a novel Plasmodium assay that is able to detect at high sensitivity and throughput the most prevalent malaria parasites, P. falciparum and P. vivax, independent of malaria expertise. The detection limit of our assay (0.04 parasite/μl) is significantly better than that of either the microscopic or the RDT method, and the assay is as sensitive as the real-time qPCR assay we used (14), giving the assay an edge in detecting asymptomatic low-load patients. Not surprisingly, our assay identified all microscopy-, RDT-, or PCR-positive samples and uncovered three samples that were false negative by microscopy and four that were false negative by RDT. This exceptionally high sensitivity is not surprising, as the assay detects abundant 18S rRNA. Additionally, our direct assay eliminates target loss in nucleic acid preparation steps, which could be substantial (25). As a result, the assay has reached the ultimate sensitivity limit set by the small sampling volume of the assay (1 parasite/20 μl whole blood or 0.05 parasite/μl). This enables the assay to test a very small amount of blood, such as that obtained by pricking a finger or earlobe, a convenient way of sampling for mass screening. Blood from fingers or earlobes is ideal since the density of developed trophozoites or schizonts is greater in blood from these capillary-rich areas (29).

One of the concerns for assays that detect RNA targets is that they place strict requirements on sample quality and proper sample processing, limiting their applicability. Our direct assay reduces such requirements by its multiple-probe design (25) and a work flow with minimal sample processing. The sampled blood can be lysed and assayed after collection or can be stored frozen for analysis later without affecting the assay performance (data not shown). For RNA detection, the quality of some clinical samples used in this study was poor but resembled realistic sample quality sometimes obtained from resource-limited settings. Our assay nevertheless correctly diagnosed all 49 samples that had gone through prolonged storage and several freeze-and-thaw cycles, showing the robustness of the assay and its ability to qualitatively diagnose samples from resource-poor areas. The result is consistent with previous demonstration of the technology to detect partially degraded targets (30).

A distinguishing feature of the assay is the absence of RNA purification and reverse transcription steps, resulting in more consistent results (CV = 5%), and a work flow suitable for large-scale molecular diagnosis. Although real-time PCR and LAMP were recently reported to be able to detect plasmodia directly from whole blood (17, 31), the sensitivities were compromised compared with those obtained using purified DNA. For example, the direct qPCR missed 5 positive samples out of 74 compared with conventional qPCR (31), and the detection limit of LAMP, when used directly on heated blood instead of DNA, changed from 1 to 10 parasites/μl to 40 parasites/μl (17), a sensitivity not significantly better than that of microscopy or RDT. Our direct assay, on the other hand, is as sensitive as conventional qPCR in our sample set. In addition, our assay is performed in parallel in 96-well plates and is amenable to automation with its ELISA-like work flow. Although the sample-to-result time per run is longer than for most molecular assays, without sample purification the hands-on time is probably shorter, and when a large number of samples are to be tested, the turnaround time of this assay can be advantageous compared with existing diagnostic methods. Screening for malaria infections on mass samples can be achieved using our assay, followed by confirmation and species identification on positive samples using currently available methods such as real-time PCR. Our assay requires no expensive equipment (only an incubator and a luminescence plate reader) and has a cost similar to that of qPCR. The per-assay cost can be significantly reduced in large-scale assays, as the fixed costs are spread. It can be initially adopted in resource-rich areas and gradually implemented in resource-limited areas of endemicity as the cost is reduced by the economy of scale. Given the high assay sensitivity (0.04 parasite/μl), pooling of specimens can be considered to further improve the cost-effectiveness and throughput of screening, as practiced for viral detection in low-prevalence settings such as blood banks. Finally, our assay amplifies the detection signal instead of the target (25), making it much less prone to false positives due to cross-contamination. While the assay cannot be used as “field-ready” as for RDT, it should be deployable in a district laboratory with services that provide ELISA-type tests and should be able to be handled by a technician with little training beyond standard routine clinical laboratory practices. Overall, this assay is a more desirable alternative for large-scale malaria screening and surveillance.

Given the definitive status of microscopy and the unsurpassed ease of use of RDT, we do not expect our assay to replace microscopy or RDT for routine clinical diagnosis. Instead, it could be used as a complement to these tests, for example, for quality assurance of these tests in clinical settings. A negative result of our assay would ascertain a lack of any malaria infection, thus orienting the investigations toward other causes. Perhaps the combination of quality-assured RDT/microscopy diagnosis in health facilities and the practice of regular active community surveys, as facilitated by our assay, will provide the needed assurance to clinicians to prescribe in consistency with malaria test results, resolving the issue of malaria overdiagnosis currently practiced in many low-transmission areas (19).

As an initial evaluation of assay performance, our study focused only on febrile patients, without screening for asymptomatic malaria patients; we therefore cannot make claims for asymptomatic malaria, but the excellent detection limit for cultured P. falciparum and the high-throughput detection of all malaria infections (microscopic and submicroscopic) in our sample set make the method promising for large-scale screening of malaria. Although only P. falciparum and P. vivax samples were tested in this study, the assay has the potential to detect other malaria species infectious to humans, since we targeted highly conserved regions of Plasmodium sequences. Since P. falciparum and P. vivax are the two most prevalent Plasmodium parasites responsible for the majority of malaria cases in the world and countries that proceed to malaria elimination are suggested to focus on P. falciparum and P. vivax elimination (32), our assay is ready to be evaluated for malaria screening/surveillance in actual elimination settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Major Program of China (no. 2008ZX10004011 and no. 2012ZX10004220 to Z. Zheng).

We thank Xiaoyi Tian and Yuhui Gao for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 October 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Alonso PL, Brown G, Arevalo-Herrera M, Binka F, Chitnis C, Collins F, Doumbo OK, Greenwood B, Hall BF, Levine MM, Mendis K, Newman RD, Plowe CV, Rodriguez MH, Sinden R, Slutsker L, Tanner M. 2011. A research agenda to underpin malaria eradication. PLoS Med. 8: e1000406 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feachem RG, Phillips AA, Targett GA, Snow RW. 2010. Call to action: priorities for malaria elimination. Lancet 376:1517– 1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guerra CA, Gikandi PW, Tatem AJ, Noor AM, Smith DL, Hay SI, Snow RW. 2008. The limits and intensity of Plasmodium falciparum transmission: implications for malaria control and elimination worldwide. PLoS Med. 5: e38 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harris I, Sharrock WW, Bain LM, Gray KA, Bobogare A, Boaz L, Lilley K, Krause D, Vallely A, Johnson ML, Gatton ML, Shanks GD, Cheng Q. 2010. A large proportion of asymptomatic Plasmodium infections with low and sub-microscopic parasite densities in the low transmission setting of Temotu Province, Solomon Islands: challenges for malaria diagnostics in an elimination setting. Malar. J. 9:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ogutu B, Tiono AB, Makanga M, Premji Z, Gbadoe AD, Ubben D, Marrast AC, Gaye O. 2010. Treatment of asymptomatic carriers with artemether-lumefantrine: an opportunity to reduce the burden of malaria? Malar. J. 9:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vafa M, Troye-Blomberg M, Anchang J, Garcia A, Migot-Nabias F. 2008. Multiplicity of Plasmodium falciparum infection in asymptomatic children in Senegal: relation to transmission, age and erythrocyte variants. Malar. J. 7:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baliraine FN, Afrane YA, Amenya DA, Bonizzoni M, Menge DM, Zhou G, Zhong D, Vardo-Zalik AM, Githeko AK, Yan G. 2009. High prevalence of asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum infections in a highland area of western Kenya: a cohort study. J. Infect. Dis. 200:66– 74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coleman RE, Kumpitak C, Ponlawat A, Maneechai N, Phunkitchar V, Rachapaew N, Zollner G, Sattabongkot J. 2004. Infectivity of asymptomatic Plasmodium-infected human populations to Anopheles dirus mosquitoes in western Thailand. J. Med. Entomol. 41: 201– 208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roper C, Elhassan IM, Hviid L, Giha H, Richardson W, Babiker H, Satti GM, Theander TG, Arnot DE. 1996. Detection of very low level Plasmodium falciparum infections using the nested polymerase chain reaction and a reassessment of the epidemiology of unstable malaria in Sudan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 54: 325– 331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schneider P, Bousema JT, Gouagna LC, Otieno S, van de Vegte-Bolmer M, Omar SA, Sauerwein RW. 2007. Submicroscopic Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte densities frequently result in mosquito infection. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 76: 470– 474 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moody A. 2002. Rapid diagnostic tests for malaria parasites. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15: 66– 78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Okell LC, Ghani AC, Lyons E, Drakeley CJ. 2009. Submicroscopic infection in Plasmodium falciparum-endemic populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. Dis. 200: 1509– 1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Jarra W, Thaithong S, Brown KN. 1993. Identification of the four human malaria parasite species in field samples by the polymerase chain reaction and detection of a high prevalence of mixed infections. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 58: 283– 292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rougemont M, Van Saanen M, Sahli R, Hinrikson HP, Bille J, Jaton K. 2004. Detection of four Plasmodium species in blood from humans by 18S rRNA gene subunit-based and species-specific real-time PCR assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42: 5636– 5643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kamau E, Tolbert LS, Kortepeter L, Pratt M, Nyakoe N, Muringo L, Ogutu B, Waitumbi JN, Ockenhouse CF. 2011. Development of a highly sensitive genus-specific quantitative reverse transcriptase real-time PCR assay for detection and quantitation of plasmodium by amplifying RNA and DNA of the 18s rRNA genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49: 2946– 2953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mens PF, Schoone GJ, Kager PA, Schallig HD. 2006. Detection and identification of human Plasmodium species with real-time quantitative nucleic acid sequence-based amplification. Malar. J. 5: 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lucchi NW, Demas A, Narayanan J, Sumari D, Kabanywanyi A, Kachur SP, Barnwell JW, Udhayakumar V. 2010. Real-time fluorescence loop mediated isothermal amplification for the diagnosis of malaria. PLoS One 5:e13733 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. malERAConsultative Group on Diagnoses and Diagnostics 2011. A research agenda for malaria eradication: diagnoses and diagnostics. PLoS Med. 8:e1000396 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sansom C. 2009. Overprescribing of antimalarials. Lancet Infect. Dis. 9:596 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reyburn H, Mbakilwa H, Mwangi R, Mwerinde O, Olomi R, Drakeley C, Whitty CJ. 2007. Rapid diagnostic tests compared with malaria microscopy for guiding outpatient treatment of febrile illness in Tanzania: randomised trial. BMJ 334:403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ansah EK, Narh-Bana S, Epokor M, Akanpigbiam S, Quartey AA, Gyapong J, Whitty CJ. 2010. Rapid testing for malaria in settings where microscopy is available and peripheral clinics where only presumptive treatment is available: a randomised controlled trial in Ghana. BMJ 340:c930 doi:10.1136/bmj.c930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lubell Y, Reyburn H, Mbakilwa H, Mwangi R, Chonya S, Whitty CJ, Mills A. 2008. The impact of response to the results of diagnostic tests for malaria: cost-benefit analysis. BMJ 336:202– 205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cibulskis RE, Aregawi M, Williams R, Otten M, Dye C. 2011. Worldwide incidence of malaria in 2009: estimates, time trends, and a critique of methods. PLoS Med. 8: e1001142 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. malERAConsultative Group on Monitoring, Evaluation, and Surveillance 2011. A research agenda for malaria eradication: monitoring, evaluation, and surveillance. PLoS Med. 8:e1000400 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng Z, Luo Y, McMaster GK. 2006. Sensitive and quantitative measurement of gene expression directly from a small amount of whole blood. Clin. Chem. 52:1294– 1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. World Health Organization 1996. Assessment of therapeutic efficacy of antimalarial drugs for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in areas with intense transmission. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 27. World Health Organization 2010. Information note on recommended selection criteria for malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs). http://www.who.int/malaria/diagnosis_treatment/diagnosis/RDT_selection_criteria.pdf Accessed 9 October 2011

- 28.Bushnell S, Budde J, Catino T, Cole J, Derti A, Kelso R, Collins ML, Molino G, Sheridan P, Monahan J, Urdea M. 1999. ProbeDesigner for the design of probesets for branched DNA (bDNA) signal amplification assays. Bioinformatics 15: 348– 355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gilles HM. 1993. Diagnostic methods in malaria, p 78–99 In Gilles HM, Warrell DA. (ed), Bruce-Chwatts essential malariology, 3rd ed. P Edward Arnold, London, United Kingdom: [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yang W, Maqsodi B, Ma YQ, Bui S, Crawford KL, McMaster GK, Witney F, Luo YL. 2006. Direct quantification of gene expression in homogenates of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Biotechniques 40: 481– 486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Taylor BJ, Martin KA, Arango E, Agudelo OM, Maestre A, Yanow SK. 2011. Real-time PCR detection of Plasmodium directly from whole blood and filter paper samples. Malar. J. 10: 244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. World Health Organization 2010. World malaria report 2010. http://www.who.int/malaria/world_malaria_report_2010/en/ Accessed 9 October 2011