Abstract

Invasive aspergillosis by Aspergillus fumigatus is a leading cause of infection-related mortality in immunocompromised patients. In this study, we show that veA, a major conserved regulatory gene that is unique to fungi, is necessary for normal morphogenesis in this medically relevant fungus. Although deletion of veA results in a strain with reduced conidiation, overexpression of this gene further reduced conidial production, indicating that veA has a major role as a regulator of development in A. fumigatus and that normal conidiation is only sustained in the presence of wild-type VeA levels. Furthermore, our studies revealed that veA is a positive regulator in the production of gliotoxin, a secondary metabolite known to be a virulent factor in A. fumigatus. Deletion of veA resulted in a reduction of gliotoxin production with respect to that of the wild-type control. This reduction in toxin coincided with a decrease in gliZ and gliP expression, which is necessary for gliotoxin biosynthesis. Interestingly, veA also influences protease activity in this organism. Specifically, deletion of veA resulted in a reduction of protease activity; this is the first report of a veA homolog with a role in controlling fungal hydrolytic activity. Although veA affects several cellular processes in A. fumigatus, pathogenicity studies in a neutropenic mouse infection model indicated that veA is dispensable for virulence.

INTRODUCTION

The ubiquitous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus is one of the most common human fungal pathogens, particularly in immunosuppressed patients. This group includes patients with hematological malignancies, individuals with genetic immunodeficiencies, individuals infected with HIV, and cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy (24, 41, 53, 61, 67, 95). This population group is increasing (50) due to the HIV pandemic, the higher number of transplants, and immunosuppressive and myeloablative therapies for autoimmune and neoplastic diseases (24, 31, 50, 79). Mortality rates caused by A. fumigatus infections in immunosuppressed patients range from 40% to 90% (44, 50, 60, 77, 79).

The main point of entry leading to infection by A. fumigatus is the respiratory tract. Aspergillus fumigatus infection can cause aspergilloma and invasive aspergillosis (IA) among immunosuppressed individuals. Aspergillus fumigatus asexual spores (conidia) are small compared to those of other Aspergillus species, being only 2.5 to 3.0 μm in diameter. This allows them to reach the lung alveoli (74, 76). In individuals with healthy immune systems, spores that are not removed by mucociliary clearance are eliminated by epithecial cells or alveolar macrophages, by phagocytosis and killing of conidia, triggering a proinflammatory response that recruits neutrophils that eliminate hyphae. Failure in these defenses leads to IA. Due to the fact that conidia are the main inoculum in A. fumigatus infections, it is important to elucidate the genetic mechanism governing the production of asexual spores in this fungus. A homolog of the VeA fungal global regulator was found in A. fumigatus (6, 45, 85) and was reported to affect conidiation in a nitrogen source-dependent manner (45).

VeA homologs have been described to regulate asexual and sexual development in numerous fungal species (26, 38, 39, 52, 100). VeA function has been particularly characterized in the model fungus Aspergillus nidulans, where it was found that VeA forms a nuclear protein complex. Mechanistically, VeA is transported to the nucleus by the α-importin KapA (4, 85). In the nucleus, VeA interacts with the chromatin-remodeling LaeA protein (6), the red phytochrome-like protein FphA, which interacts with the blue light-response elements LreA and LreB (68), and VelB, another velvet family protein (6, 7, 58).

In addition to its role in regulating development, VeA has been demonstrated to control secondary metabolism in several fungal genera (reviewed in reference 17). The first study demonstrating the association of VeA with regulation of secondary metabolism was carried by our group in 2003 (38), where we showed that VeA was necessary for the production for the mycotoxin sterigmatocystin. VeA controls the expression of the transcription factor gene aflR (38), which is necessary for sterigmatocystin gene cluster activation (103). VeA is found in numerous fungal species, particularly in Ascomycetes (57). Orthologs of VeA in other fungi have also been demonstrated to regulate secondary metabolism: for example, aflatoxin in Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus (16, 26), fumonisin and fusarins in Fusarium verticillioides (56) and F. fujikori, where it was also found to regulate gibberellins and bikaverin (96), trichothecenes in Fusarium graminearum (54), dothistromin in Dothistroma septosporum (19), penicillin in A. nidulans (38), cephalosporin C in Acremonium chrysogenum (25), polyketide ML-236B (substrate in pravastatin production) in Penicillium citrinum (5), and T-toxin in Cochliobolus heterostrophus (99), among others.

Whether VeA affects secondary metabolism in A. fumigatus remains to be determined. Secondary metabolites are part of the chemical arsenal necessary for niche specialization (15), including host-fungus interactions. Aspergillus fumigatus synthesizes several toxic secondary metabolites. Some of these compounds act as immunosuppressants, which may influence pathogenesis processes. Among them, the most characterized is gliotoxin. Some studies have described that gliotoxin is important for virulence, while others have shown that it is unimportant (reviewed in references 23 and 47). Gliotoxin has been described as having immunosuppressive properties (3, 12, 20, 29, 55, 62, 66, 83, 86, 92, 94, 101, 102). This compound has also been shown to inhibit phagocytosis in macrophages and to induce apoptosis. Gliotoxin has been detected in A. fumigatus-infected animals and humans at concentrations at least as high as those required to detect an effect in vitro (28, 72).

Other virulence factors also allow A. fumigatus to become an opportunistic pathogen in the case of immunocompromised patients. Examples of these virulence factors include conidial cell components (10, 14, 33, 34, 48, 91). Additionally, Kolattukudy et al. (43) reported that certain fungal hydrolytic activities could also influence pathogenicity. For example, mutants defective in elastolytic serine protease showed a decreased in virulence (43). Also, the A. fumigatus strain lacking hacA, encoding a transcriptional regulator of the unfolded protein response (73), showed a reduced capacity for protease secretion and reduction in virulence. Whether VeA affects hydrolytic activity in A. fumigatus has not been previously investigated.

The effect of VeA on virulence has been mainly characterized in plant-pathogenic fungi. For example, we found that the F. verticillioides veA null mutant fails to produce disease in seedlings grown from seeds infected with a veA deletion mutant (57). Deletion of veA also reduced plant pathogenicity in Aspergillus flavus (27), A. parasiticus (16), F. fujikuroi (96), F. graminearum (54), and Cochliobolus heterostrophus (99), among others. Importantly, a recent study has shown for the first time that VeA also influences pathogenicity in animals by the opportunistic pathogenic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum (49).

In the present study, we demonstrate that veA not only controls morphogenesis by regulating conidiation, but it also controls gliotoxin gene expression and concomitant gliotoxin biosynthesis in A. fumigatus. Importantly, we report for the first time a relationship between hydrolytic enzymes, specifically protease activity, and the VeA regulator in fungi. Additionally, we evaluated the possible role of veA in pathogenity in a murine model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

The Aspergillus fumigatus strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains were grown on Czapek Dox medium (Difco), unless otherwise indicated, plus the appropriate supplements for the corresponding auxotrophic markers (37). Solid medium was prepared by adding 15 g/liter agar. Strains were stored as 30% glycerol stocks at −80°C.

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

| Name | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| CEA10 | veA+ | Gift from Robert Cramer |

| CEA17 | pyrG1 veA+ | Gift from Robert Cramer |

| TSD1.15 | pyrG1 ΔveA::pyrGA. fum | This study |

| TSD3.5 | pyrG1 ΔveA::pyrG veA::hyg | This study |

| TSD2.8 | pyrG1 gpdA(p)::veA::trpC(t)::pyrGA. fum | This study |

| TSD25.1 | pyrG1 veA::gfp::pyrGA. fum | This study |

| TSD26.1 | pyrG1 gpdA(p)::gliZ::trpC(t)::pyrGA. fum | This study |

Generation of the deletion, complementation, and overexpression strains.

The deletion cassette was generated by fusion PCR as outlined by Szewczyk et al. (89). A 1.2-kb 5′-untranslated region (UTR) fragment was first amplified from A. fumigatus genomic DNA with primers 5′F-Afu577 and 5′R-Afu578 (Table 2). A 1.2-kb 3′-UTR fragment was also amplified from genomic DNA with primers 3′F-Afu579 and 3′R-Afu580 (Table 2). The intermediate DNA fragment containing the A. fumigatus pyrG (pyrGA. fum) was amplified from plasmid p1439 (84) using primers Afu5PyrG581 and Afu3PyrG582 (Table 2). pyrG was utilized as transformation marker, achieving a complete gene replacement of veA in CEA17, a commonly used pyrG auxotroph derived from the wild-type pathogenic isolate CBS144-89 (32, 40, 80).

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Name | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| 5′F-Afu577 | 5′-GTGCTCTCTGGTTGGATCAGCCTG-3′ |

| 5′R-Afu578 | 5′-GGCTCTTGGGTTGGATTCGAAGG-3′ |

| 3′F-Afu579 | 5′-CGTGTTGGCCAGTGGAAAGATTATGTTC-3′ |

| 3′R-Afu580 | 5′-CCGCAACGTGGGATAGTGACGC-3′ |

| Afu5PyrG581 | 5′-CCTTCGAATCCAACCCAAGAGCCACCGGTCGCCTCAAACAATGCTCT-3′ |

| Afu3PyrG582 | 5′-GAACATAATCTTTCCACTGGCCAACACGGTCTGAGAGGAGGCACTGATGCG-3′ |

| veAcompFXbaI394 | 5′-AAAAATCTAGATGCTGCTGATCGCCTTGGTC-3′ |

| veAcompRXbaI478 | 5′-AAAAATCTAGAGCGGCTTTTCGCTCACGCTG-3′ |

| pBC-HygroF769 | 5′-ATCCTTGAAGCTGTCCCTGATGGT-3′ |

| pBC-HygroR770 | 5′-TCCGGCTCGTATGTTGTGTGGAAT-3′ |

| veAF398_AscI | 5′-AAAAGGCGCGCCATGGCGACCAGACCGCC-3′ |

| veAR399_NotI | 5′-ATATATAAAGCGGCCGCTATGGTAGCGCAGGCAAAATCTTCATGAC-3′ |

| pyrGF-XbaI-1439 | 5′-AAAAATCTAGAACCGGTCGCCTCAAACAATGCTCT-3′ |

| pyrGR-XbaI-1439 | 5′-AAAAATCTAGAGTCTGAGAGGAGGCACTGATGCG-3′ |

| gpdAF592 | 5′-AAGTACTTTGCTACATCCATACTCC-3′ |

| Afu5′F428 | 5′-AAAGAATTCAAGTTGCAGGAGTAGGATTTGGG-3′ |

| Linker-R642 | 5′-GTCTGAGAGGAGGCACTGATGCG-3′ |

| veA_qRTPCR_F814 | 5′-CCCCACGCTGTCGCAACCTCC-3′ |

| veA_qRTPCR_R815 | 5′-GCCGAAGGTTTCCTCGTGCGATCGC-3′ |

| gliP_qRTPCR_F840 | 5′-AGTTACACCGACTCGCATCCAGCTGC-3′ |

| gliP_qRTPCR_R841 | 5′-CTGGGGCAGACCATGCGTAG-3′ |

| gliZ_qRTPCR_F838 | 5′-ACGACGATGAGGAATCGAACCCG-3′ |

| gliZ_qRTPCR_R839 | 5′-GGTGCTCCAGAAAAGGGAGTCGTTG-3′ |

| veA_gfp_F589 | 5′-GACCGCCTTTAATGCCTCCCG-3′ |

| veA_gfp_R643 | 5′-TGGTAGCGCAGGCAAAATCTTCAT-3′ |

| veA_gfp_fusion_F644 | 5′-ATGAAGATTTTGCCTGCGCTACCAGGAGCTGGTGCAGGCGCTGGAGCC-3′ |

| gliZF_AscI1040 | 5′-ATATATATATGGCGCGCCATGGCGACAGCTATGCAGGATGTG-3′ |

| gliZR_Not11041 | 5′-ATATATATATAGCGGCCGCCTACAGCGCCAGTAGGTTGCACAATC-3′ |

| 18s_qRTPCRF_849 | 5′-TAGTCGGGGGCGTCAGTATTCAGC-3′ |

| 18s_qRTPCRR_850 | 5′-GTAAGGTGCCGAGCGGGTCATCAT-3′ |

| brlA_qRTPCRF_1158 | 5′-TGCACCAATATCCGCCAATGC-3′ |

| brlA_qRTPCRR_1159 | 5′-CGTGTAGGAAGGAGGAGGGGTTACC-3′ |

| FKS1-F | 5′-GCCTGGTAGTGAAGCTGAGCGT-3′ |

| FKS1-R | 5′-CGGTGAATGTAGGCATGTTGTCC-3′ |

| qPCR-probe | 6-FAM-AGCCAGCGGCCCGCAAATG-MGB-3′b |

Restriction sites are underlined.

From Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA. 6-FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; MGB, minor groove binder.

A complementation strain was also generated by transformation of the veA deletion mutant with the veA wild-type allele. The complementation veA strain was constructed by PCR amplification of a 6-kb genomic DNA fragment, including the coding region of the A. fumigatus veA gene, the 2.7-kb 5′-UTR, and the 1.5-kb 3′-UTR, with primers veAcompFXbaI394 and veAcompRXbaI478. This PCR product was then digested with XbaI and cloned into pBC-Hygro plasmid, containing the hygromycin B resistance marker hyg (FGSC), previously digested with XbaI, resulting in pSD20. A 10.3-kb fragment was then amplified from pSD20 using primers pBC-HygroF769 and pBC-HygroR770, which was then used to transform the veA deletion strain TSD1.15.

The A. fumigatus veA overexpression (OEveA) strain was constructed by transforming CEA17 with plasmid pSD21, resulting in strain TSD2.8. The overexpression plasmid was constructed as follows. First, A. fumigatus veA was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA using primers veAF398_AscI and veAR399_NotI (Table 2). This fragment was digested with AscI and NotI and ligated to plasmid pTMH44.2 (gift from N. P. Keller) previously digested with AscI and NotI. pTMH44.2 contains the gpdA promoter, gpdA(p), and trpC terminator, trpC(t), from A. nidulans. A. fumigatus pyrG was PCR amplified from p1439 with primers pyrGF-XbaI-1439 and pyrGR-XbaI-1439 (Table 2) and cloned into XbaI of pTMH44.2, resulting in the final transformation plasmid, pSD21.

The A. fumigatus gliZ overexpression strain (OE gliZ) was constructed by transformation of CEA17 with plasmid pSD37.1, resulting in strain TSD26.1. pSD37.1 was constructed as follows. First, A. fumigatus gliZ was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA using primers gliZF_AscI1040 and gliZR_Not11041 (Table 2). This fragment was then digested with AscI and NotI and ligated to plasmid pSD21, previously digested with AscI and NotI.

All A. fumigatus polyethylene glycol-mediated transformations were performed as previously described (89). Transformants were first screened by PCR using primers veA5F428 and linkerR642 for deletion and veAF398_AscI and veAR399_NotI for complementation. Selected transformants were further confirmed by Southern analysis (75). The OE veA strain was confirmed by PCR with primers gpdAF592 and veAR399_NotI, and the OE gliZ strain was confirmed by PCR with primers gpdAF592 and gliZR_Not11041 (Table 2).

Morphological analysis.

For assessment of colony growth, A. fumigatus strains were point inoculated on Czapek Dox medium and colony diameter was measured after 5 days. Next, 16-mm-diameter cores were harvested 1 cm from the center of the plates. Cores were homogenized in water, and conidia were counted using a hemocytometer. The experiments were done in the dark and in the light.

Gliotoxin analysis.

Analysis of gliotoxin production was conducted in a time course experiment. Plates containing 25 ml of liquid Czapek Dox medium were inoculated with approximately 107 conidia per plate. Stationary cultures were incubated at 37°C. Supernatant from 72- and 120-h-old cultures was filtered through sterile Miracloth (Calbiochem). Seventeen milliliters of culture supernatants from the 72- and 120-h time points were extracted with chloroform. The extracts were then allowed to dry and resuspended in 1 ml of methanol. The methanol-soluble extracts were then filtered with a 0.22-μm-pore filter, dried again, and resuspended in 500 μl of methanol. Gliotoxin analysis was performed as described by Cramer et al. (22), with some modifications. Briefly, 20 μl from each methanol solution was analyzed in a Waters 1525 high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system equipped with a binary pump and a Waters 717 autosampler. HPLC separation was performed at 37°C on a Phenomenex C18 4.6- by 25-mm, 5-μm analytical column connected to a column guard. UV detection was at 264 nm (Waters 2487 dual λ absorbance detector). Compounds were eluted using an isocratic mobile phase of water-acetonitrile-trifluoroacetic acid (65:34.9:0.1) with a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Gliotoxin was detected at a wavelength of 264 nm. Peak areas of the analyzed samples were compared to those from standard gliotoxin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Gene expression analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from mycelia harvested from 48- and 72-h liquid stationary cultures using TRIzol (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Five micrograms of total RNA was treated with DNase I RQI (Promega) to remove DNA contamination. One microgram of DNase-treated RNA was reverse transcribed using Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase (Promega). Expression of gliZ and gliP was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The reactions were performed with an Mx3000p thermocycler (Agilent Technologies) using SYBR green Jumpstart Taq Ready mix (Sigma). The primers used in qRT-PCR are listed in Table 2. Similarly, expression of brlA was analyzed in 72-h liquid stationary cultures by qRT-PCR. The primers used in this qRT-PCR analysis are also listed in Table 2.

Protease activity.

The wild-type, veA deletion mutant, complementation, and overexpression strains were point inoculated on Czapek Dox medium containing 5% skim milk powder (Difco) in triplicates and incubated for 4 days. Degradation halos indicated protease activity. This experiment was also repeated using glucose minimal medium (GMM) (37) supplemented with skim milk.

An azocasein assay was also performed as previously described by Reichard et al. (71) with some modifications. Azocasein (Sigma) at a concentration of 5 mg/ml was dissolved in a solution containing 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5), 0.2 M NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.05% Brij 35, and 0.01% sodium azide. The entire content of 3-day-old culture plates was blended with 25 ml of distilled water and collected in a 50-ml Falcon tube. The tubes were centrifuged at 3,800 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. One milliliter of supernatant was centrifuged again at 10,000 rpm for 3 min at 4°C. One hundred microliters of the supernatant was mixed with 400 μl of azocasein solution. The samples were incubated at 37°C in a water bath for 90 min. Twenty percent trichloroacetic acid was added to stop the reactions, and the samples were left at room temperature for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 3 min. Three hundred microliters of supernatant was then mixed with 300 μl of 1 M NaOH. The absorbance of the released azo group was measured in 96-well flat-bottom plates (BD Falcon) using a plate reader (Biotek) at 436 nm in duplicates. Distilled water mixed with azocasein was used as a blank.

In a separate experiment, the wild-type, veA deletion mutant, complementation, and overexpression strains were incubated on Czapek Dox medium, with 0.4% bovine serum albumin (BSA) or 0.1% peptone substituted for sodium nitrate as the nitrogen source, as described previously (9), and incubated at 37°C for 3 days to observe possible differences in the ability to grow utilizing a nonhydrolyzed nitrogen source.

Fluorescence microscopy.

The A. fumigatus CEA17 strain (Table 1) was transformed with the veA::gfp::pyrGA. fum fusion PCR products as described by Szewczyk et al. (89). The primers used for fusion PCR are listed in Table 2. Plasmid p1439 (85) was used as the template for the PCR amplification of the intermediate fragment. Integration was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis (data not shown). Conidia from the selected transformant TSD21.1 (Table 1) were inoculated as described previously (85). Briefly, conidia were inoculated on the surface of coverslips immersed in Watch minimal medium (65). The cultures were incubated for 16 h at 37°C in the dark or in the light. Samples were observed with a Nikon Eclipse E-600 microscope with a 60× oil-immersion objective, Nomarski optics, and fluorochromes for green fluorescent protein (GFP) detection (excitation, 470; emission, 525). Micrographs were taken using a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER high-sensitivity monochrome digital charge-coupled device (CCD) camera with MicroSuite5 image capture and optimization software. Differential interference contrast (DIC) and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) images to indicate nuclear localization were taken with an exposure of 200 ms and for GFP with an exposure of 1 s.

Osmotic and oxidative stress assays.

To test sensitivity to osmotic stress, Czapek Dox medium was supplemented with 0.6 M KCl, 1.2 M sorbitol, or 1 M sucrose. Strains were then point inoculated on these media. After 3 days of incubation at 37°C, colony diameter was measured.

Sensitivity of A. fumigatus strains to oxidative stress was determined as previously described by Sugareva et al. (87) with some modification. Spores (5 ×106 spores/ml) were top agar inoculated with 5 ml of Czapek-Dox medium (0.5% agar) on 25-ml plates of solid Czapek Dox medium (1.5% agar). After solidification, 7-mm cores were made at the center of each plate, and 100 μl of 2 mM water-soluble menadione (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 h, and growth inhibition halos were measured. The experiment was performed with three replicates.

Menadione sensitivity was also tested by adding various concentrations of menadione to the medium (0, 5, 7.5, 10, and 15 μM) after autoclaving and measuring the colony diameter after 48 h. The experiment was performed with four replicates.

Effect of pH on growth.

To test a possible veA-dependent effect of different pHs on A. fumigatus growth, Czapek Dox medium was adjusted to various pH levels (pHs 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10) and point inoculated with wild-type, veA deletion mutant, complementation, and overexpression strains. Colony diameter was measured after 48 h of incubation.

Cell wall defect tests.

To identify possible alterations in the cell wall due to alterations caused by the deletion or overexpression of veA, the strains were inoculated on Czapek Dox medium containing 0.05% or 0.1% SDS. With the same goal, a similar experiment was also carried out with addition of 5, 10, 20, 25, 50, or 100 μg/ml of Congo red to Czapek Dox medium (69, 73, 93). The cultures were incubated at 37°C in the dark. After 72 h, colony diameter was observed. Cell wall integrity was also tested by adding 32 and 64 μg/ml of the antifungal compound nikkomycin Z, as described in reference 84.

Pathogenicity tests.

Female 6-week-old, outbred Swiss ICR mice (Harlan Sprague Dawley), weighing 24 to 27 g, were immunosuppressed (neutropenic) by intraperitoneal injection of cyclophosphamide (150 mg/kg of body weight) on days −4, −1, and 3 with a single dose of cortisone acetate (200 mg/kg), given subcutaneously. The mice were anesthetized via isoflurane inhalation in a bell jar on day 0. The mice were infected by intranasal inoculation, mimicking the natural route of infection. Inocula were prepared from four strains: the isogenic wild-type strain, the ΔveA mutant, the complementation strain, and the OEveA strain grown on glucose minimal medium (GMM) plates. Conidia were harvested by flooding fungal colonies with 0.85% NaCl with Tween 80, enumerated with a hemocytometer, and adjusted to a final concentration of 6 log10 CFU/ml. (To ensure inoculum viability, counts and the viability of the inocula were verified by triplicate serial plating on GMM plates.) Sedated mice (10 mice/fungal strain) were infected by nasal instillation of 50 μl of the inoculum (day 1) and monitored three times daily for 7 days postinfection. All surviving mice were sacrificed on day 7. The tissue fungal burden in whole-lung homogenate was quantified by qPCR. Briefly, in this qPCR procedure we assessed the fungal tissue burden of infected animals by use of a single copy [FKS encoding a β (1-3) glucan synthase] to determine the number of fungal cell nuclei present (13, 21, 36). The primers used for qPCR are listed in Table 2. Cumulative mortality curves were generated, and the statistical analysis using the log rank test was utilized to perform pairwise comparisons of survival levels among the strain groups.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was done, unless otherwise indicated, by analysis of variance (ANOVA) in conjunction with Tukey's test using Statistical Package for Social Sciences 19 (SPSS 19; IBM). The means were compared at a P value of 0.05.

RESULTS

veA affects colony pigmentation and conidiation in A. fumigatus.

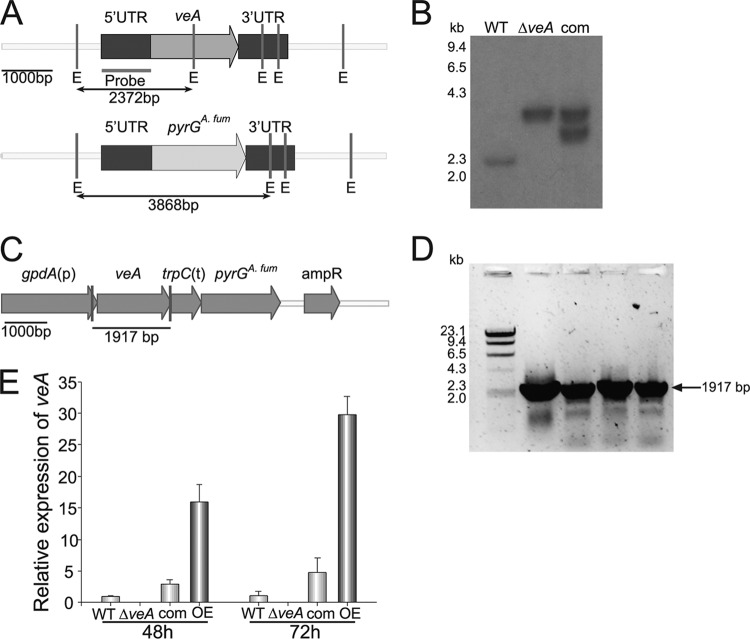

Studies in the model filamentous fungus A. nidulans have shown that veA regulates morphogenesis in a light-dependent manner, acting as a positive regulator of sexual development and a negative regulator of asexual development (100). Krappmann et al. (45) reported a reduction in conidiation on medium containing nitrate as nitrogen source in an A. fumigatus veA deletion mutant. The corresponding deduced amino acid sequence presents 55% identity with A. nidulans VeA, 67% with A. flavus VeA, and 68% with A. parasiticus VeA, all experimentally characterized orthologs (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) (16, 26, 38). In our study, we generated a veA deletion strain and also an OEveA strain with a constitutively active promoter to further investigate the role of veA in A. fumigatus conidiation as well as fungal growth. The construction of these strains was carried out as detailed in Materials and Methods. Polyethylene glycol-mediated transformation of the A. fumigatus CEA17 strain with the deletion DNA cassette yielded several transformants. These transformants were analyzed by PCR (data not shown) and Southern blotting (Fig. 1A and B). Complementation strains were obtained by transforming the selected deletion strain (TSD1.15) with an A. fumigatus veA wild-type allele (Fig. 1B). OEveA strains were also generated and confirmed by PCR (Fig. 1C and D). Expression analysis by qRT-PCR indicated absence of A. fumigatus veA expression in the ΔveA strain, recovery of veA expression after complementation with the veA wild-type allele, and higher accumulation of transcripts when veA was overexpressed. This was observed at both time points tested (48 and 72 h after inoculation) (Fig. 1E).

Fig 1.

DNA and RNA analyses for the verification of the A. fumigatus deletion and overexpression mutants. (A) Schematic representation showing EcoRI sites in the A. fumigatus wild-type veA locus and the veA deletion construct generated to replace veA with the A. fumigatus pyrG gene (pyrGA. fum) utilized as a transformation marker gene. The fragment used as the probe template for Southern blot analysis is also shown. The sizes of the DNA fragments predicted for the Southern blot analysis using this probe are also shown for both the wild-type and veA deletion mutant strains. (B) Southern blot analysis. The veA gene replacement construct was transformed in CEA17. EcoRI-digested genomic DNA of CEA10 wild-type (WT), ΔveA transformant (TSD1.15), and complementation transformant (TSD3.5) was hybridized with the probe shown in panel A. Additional deletion transformants also showed the same band pattern (data not shown). The extra band in the analysis of the complementation strain indicates integration of the wild-type veA allele in the TSD1.15 genomic DNA. Additional complementation transformants were also obtained. Integration of the full complementation cassette in these strains was also confirmed by PCR (data not shown). (C) Diagram showing the veA overexpression DNA cassette (from plasmid pSD21) used in this study. Vertical lines indicate the annealing sites for the primers gpdAF592and veAR399_NotI (Table 2) used in the diagnostic PCR of four veA overexpression transformants shown in panel D, with a predicted PCR product of 1,917 bp. (E) Expression analysis of veA by qRT-PCR using primers veA_qRTPCR_F814 and veA_qRTPCR_R815 (Table 2).

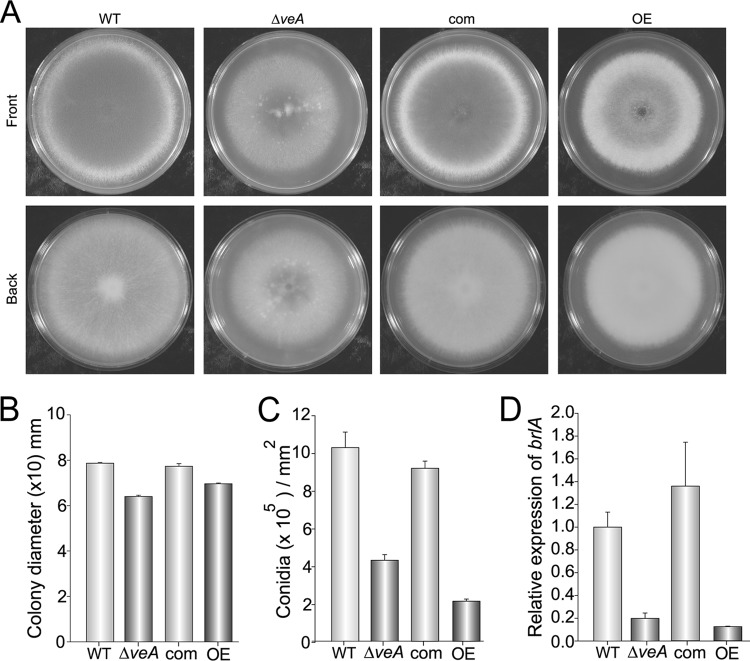

The veA deletion mutants showed slightly smaller colonies on Czapek Dox medium (Fig. 2A and B). These mutants also accumulated a dark pigment in the back of the colonies when grown on GMM (36) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), which was not produced by the wild-type strain. Colony pigmentation is also observed in A. nidulans ΔveA strains growing on the same medium (data not shown). Complementation of the A. fumigatus veA strain with the wild-type allele repressed the production of this pigment (see Fig. S2).

Fig 2.

Role of veA in A. fumigatus colony growth and conidiation. (A) Aspergillus fumigatus wild-type (WT), ΔveA, complementation (com), and OEveA (OE) strains were point inoculated on Czapek Dox medium and incubated for 5 days in the dark. (B) Colony diameter measurements. (C) Quantification of conidial production. Cores (16 mm in diameter) were taken 1 cm from the center of the plates and homogenized in water. Spores were counted using a hemocytometer. (D) Relative expression levels of brlA after 72 h in liquid stationary cultures. The Aspergillus fumigatus 18S gene was used as an internal reference gene. Error bars represent standard errors.

Deletion of veA resulted in a 50% reduction in conidiation rate with respect to the levels observed in wild-type control cultures growing on Czapek Dox medium (Fig. 2A and C). Interestingly, overexpression of veA lead to an even more pronounced decrease of conidiation (85% reduction) and abundant proliferation of aerial mycelium. The same effects were observed in additional veA deletion and OEveA mutants generated in this study (data not shown). Furthermore, expression of brlA, encoding a transcription factor that regulates conidiation (2), was also decreased in the deletion and overexpression strains compared to the expression levels in the control strains (Fig. 2D). Although the A. fumigatus OEveA strain is deficient in conidiation, it only presented small variations in growth rate with respect to the control strain; there were slightly smaller but denser colonies when grown on solid Czapek Dox medium (Fig. 2A and C) and slightly greater biomass production when growing in liquid stationary cultures (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) compared to the wild-type strain under the same experimental conditions.

Although in A. nidulans it has been established that veA regulation of morphogenesis is light dependent (8, 17, 100), in A. fumigatus the effects of veA on conidiation were similar in either dark (Fig. 2A and C) or light (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) cultures, suggesting that, differently from the model fungus A. nidulans, light is not a relevant factor in the veA-mediated regulation of conidition in A. fumigatus.

Gliotoxin production and expression of gliotoxin gene cluster genes are veA dependent.

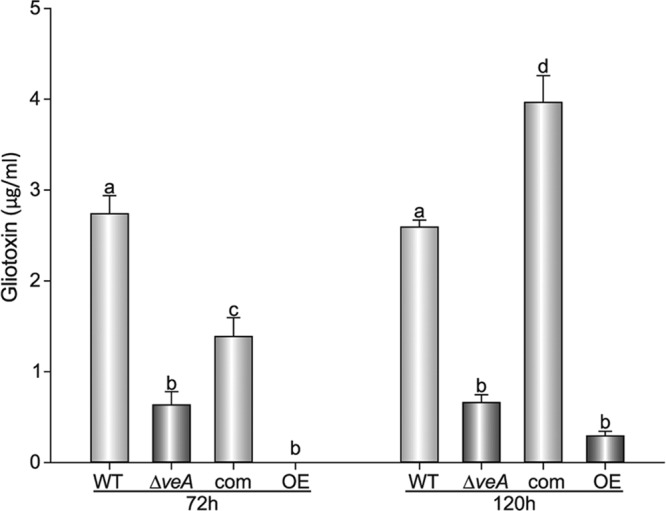

Aspergillus fumigatus produces gliotoxin, a secondary metabolite that in some cases has been shown to be associated with pathogenicity and that has been detected in the lungs of mice during infection (12). Previously it has been demonstrated that veA orthologs regulate secondary metabolism in other fungal species (17, 19, 26, 38, 56). For this reason, we investigated whether veA also controls the biosynthesis of gliotoxin in A. fumigatus. We compared the levels of production of gliotoxin in A. fumigatus wild-type, ΔveA, complementation, and OEveA strains at 3 and 5 days after inoculation. Our HPLC analysis indicated that in the absence of veA, gliotoxin production was reduced 5-fold with respect to the wild type and reached only 25% of wild-type levels after 5 days of incubation (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the OEveA strain produced only trace amounts of gliotoxin at both time points.

Fig 3.

veA controls gliotoxin production. Aspergillus fumigatus wild-type (WT), ΔveA mutant, complementation (com), and OEveA (OE) strains were grown in liquid stationary cultures in Czapek Dox medium. Samples were collected for toxin analysis 72 h and 120 h after inoculation and extracted with chloroform as detailed in Materials and Methods. Gliotoxin production in these cultures was analyzed by HPLC. The experiment was done with three replicates. Error bars represent standard errors. Different letters indicate samples that are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

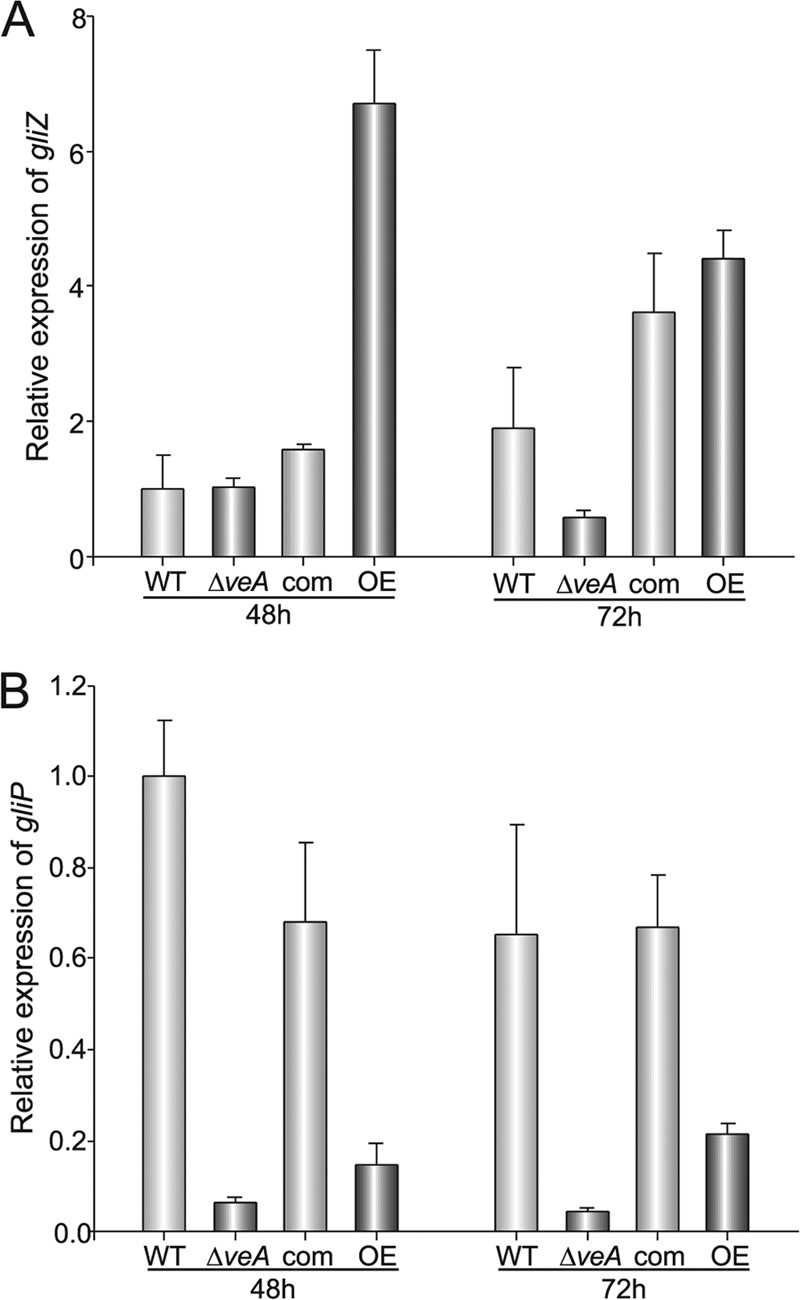

Previous studies have shown that gliP, encoding a nonribosomal peptide synthase (NRPS) (22, 46, 81, 88), and gliZ, encoding a putative Zn2Cys2 binuclear transcription factor (12), both located in the gliotoxin gene cluster, are necessary for gliotoxin biosynthesis. We examined whether the effect of veA on gliotoxin production was the result of a possible role of veA in regulating the expression levels of gliZ and gliP (Fig. 4A and B, respectively). In this study, gene expression was evaluated by qRT-PCR at 48 and 72 h after inoculation. Our results indicated that gliP expression levels were only approximately 10% in the ΔveA strain with respect to the wild-type strain at both 48 h and 72 h after inoculation (Fig. 4B). In parallel, overexpression of veA also resulted in a decrease of gliP expression compared to the wild-type expression levels. The decrease in gliP transcript accumulation correlated with the decrease in gliotoxin production observed in these strains (Fig. 3). The expression of the transcription factor-encoding gene gliZ was also reduced in the ΔveA strain to only 10% with respect to wild-type levels (Fig. 4A). Surprisingly, overexpression of veA showed an unexpected increase in the expression of gliZ compared to wild-type levels.

Fig 4.

Expression of gliZ and gliP is regulated by veA. The transcriptional pattern of gliZ (A) and gliP (B) was evaluated by qRT-PCR. Total RNA was isolated at 48 and 72 h from liquid stationary Czapek Dox cultures incubated in the dark at 37°C. Primer pairs gliZ_qRTPCR_F838 and gliZ_qRTPCR_R839 and gliP_qRTPCR_R841 and gliP_qRTPCR_R841 (Table 2) were used to measure expression of gliZ and gliP, respectively. The relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔCT method described by Schmittgen and Livak (78). Expression of the A. fumigatus 18S gene was used as internal reference. Values were normalized to that of the wild type at 48 h, which was considered 1. The error bars indicate the ranges for three replicates.

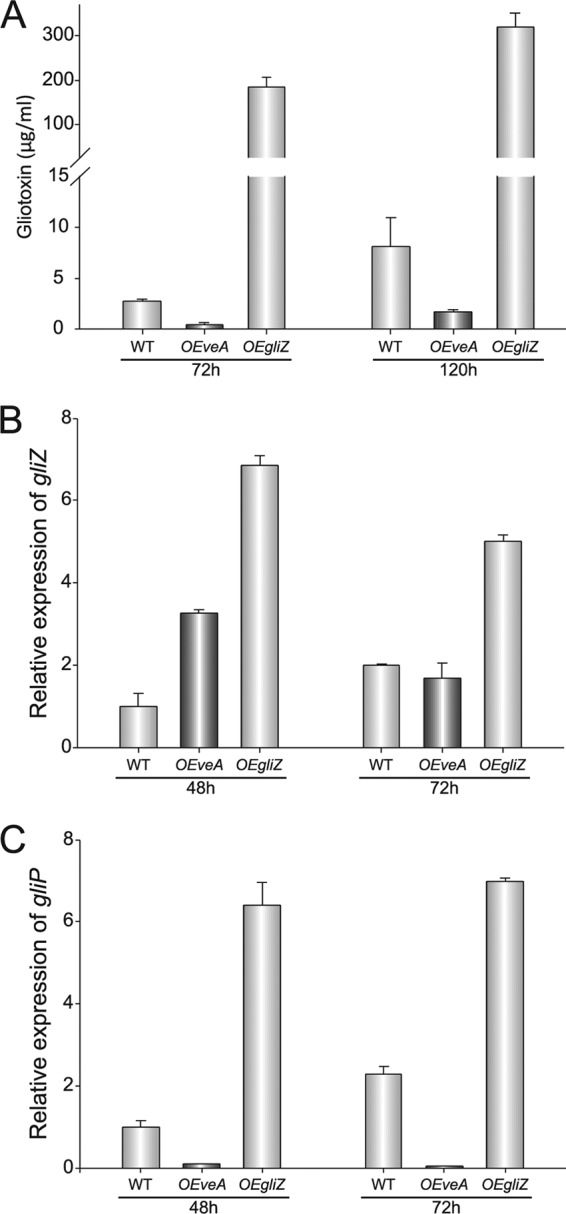

An additional experiment, including the wild-type, OEveA strain, and an OEgliZ strain (Table 1), was carried out under the same conditions. Again, the OEveA strain produced less gliotoxin than the controls: gliP was expressed only 10% or less with respect to the wild-type levels, while the gliZ expression levels increased in comparison to the wild-type control. The OEgliZ strain produced higher levels of gliotoxin, coinciding with elevated expression levels of both gliP and gliZ with respect to the wild type (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

veA controls gliotoxin production through additional mechanisms besides influencing gliZ expression. (A) HPLC analysis of gliotoxin from the Aspergillus fumigatus wild-type (WT) and OEveA and OEgliZ strains after 72 and 120 h of incubation in liquid stationary cultures. (B and C) Transcriptional patterns of gliZ and gliP, respectively. Total RNA was isolated at 48 and 72 h after inoculation. Primer pairs gliZ_qRTPCR_F838 and gliZ_qRTPCR_R839 and gliP_qRTPCR_R841 and gliP_qRTPCR_R841 (Table 2) were used to measure expression of gliZ and gliP, respectively. The relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔCT method described by Schmittgen and Livak (78). Expression of the A. fumigatus 18S gene was used as an internal reference. Values were normalized to that of the wild type at 48 h, which was considered 1. The error bars indicate the ranges for three replicates.

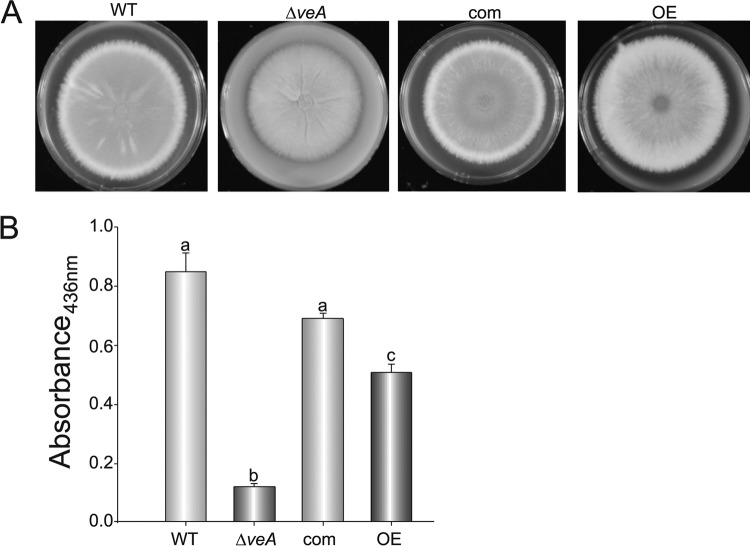

veA is required for normal protease activity.

Hydrolytic enzymes are an important factor that allows A. fumigatus to survive in the host environment (73). Previous studies showed that protease-deficient mutants are unable to grow in mouse lung in vivo. While some proteases have shown no role in virulence (9, 35; reviewed in references 1, 50, and 51), others have been shown to be associated with this process (43, 73). For this reason, in our study we examined the possible role of veA in controlling protease activity in A. fumigatus and observed that this hydrolytic activity is veA dependent. This is relevant since this is the first finding of a connection between VeA and hydrolytic activity in fungi.

In solid cultures containing casein (5% skim milk), degradation halos were observed in the wild-type and veA complemented cultures (Fig. 6A). However, the degradation halos in the ΔveA cultures were reduced in comparison to those observed in the control cultures. The azocasein quantitative analysis detected only 15% protease activity in the ΔveA cultures with respect to the wild-type strain (Fig. 6B). The OEveA strain also showed a 40% reduction in protease activity (Fig. 6B). Thus, normal expression of veA is necessary to maintain wild-type levels of protease activity in A. fumigatus.

Fig 6.

levels of veA expression are necessary for normal protease activity. (A) Aspergillus fumigatus wild-type (WT), ΔveA, complementation (com), and OEveA (OE) strains were point inoculated on Czapek Dox medium containing 5% skim milk. The plates were grown at 37°C in the dark. Degradation halos indicate protease activity. (B) Quantification of proteolytic activity measured by azocasein assay. The experiment included four replicates and was repeated twice with similar results. Error bars represent standard errors. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05).

Additionally, in a separate experiment, the wild-type, ΔveA mutant, complemented, and OEveA strains were point inoculated on Czapek Dox solid medium in which sodium nitrate was substituted for with 0.4% bovine serum albumin or 0.1% peptone as the nitrogen source and then incubated for 3 days. The growth of these strains was not as robust in Czapek Dox-BSA as that observed on Czapek Dox-peptone medium. This effect was especially notable in ΔveA colonies (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material).

Deletion or overexpression of veA does not increase sensitivity to pH, oxidative stress, osmotic stress, or the presence of SDS or Congo red in A. fumigatus.

Silencing of the H. capsulatum veA homolog, VEA1, resulted in strains that were more sensitive to acidic conditions (49), challenging their ability to grow at low pH. To test whether veA affects the capacity of A. fumigatus to grow at different pHs, we inoculated the wild-type, ΔveA, complemented, and OEveA strains on Czapek Dox medium (at pHs ranging from 3 to 10) and incubated the cultures for 3 days. Our results indicated that changes in pH did not affect the growth of these strains (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material).

Deletion of another veA ortholog in Cochliobolus heterostrophus showed a greater sensitivity to oxidative stress in this mutant (99). The ability to respond to the presence of reactive oxygen species (ROS) might be beneficial for the growth of A. fumigatus in the lung. While deletion of the conidium-specific catalase catA results in an increase in sensitivity to H2O2, no differences in conidial killing were observed in vivo in murine alveolar macrophage cultures (63). On the other hand, mycelial catalases cat1 and cat2 play a role in protecting the fungus in vivo; the mutants were sensitive to the oxidative burst of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNLs) (63). In our study, we examined whether veA is involved in the oxidative stress response in A. fumigatus. We challenged the wild-type, ΔveA, complemented, and OEveA strain cultures on Czapek Dox medium supplemented with different concentrations of menadione, as detailed in Materials and Methods. However, the addition of this compound to the culture medium equally affected the abilities of all strains to grow in the same manner (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material), inhibiting growth at a menadione concentration of 20 mM.

The possible role of veA in osmotic stress response was examined by addition of either sucrose (1 M), sorbitol (1.2 M), or KCl (0.6 M) to the medium. Also, the possible effect of veA on the integrity of the fungal cell wall was tested by addition of SDS, Congo red, or nikkomycin Z to Czapek Dox medium, as described in Materials and Methods. In these three experiments, the effect on growth caused by the supplementation of these compounds was veA independent in A. fumigatus (data not shown) (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material).

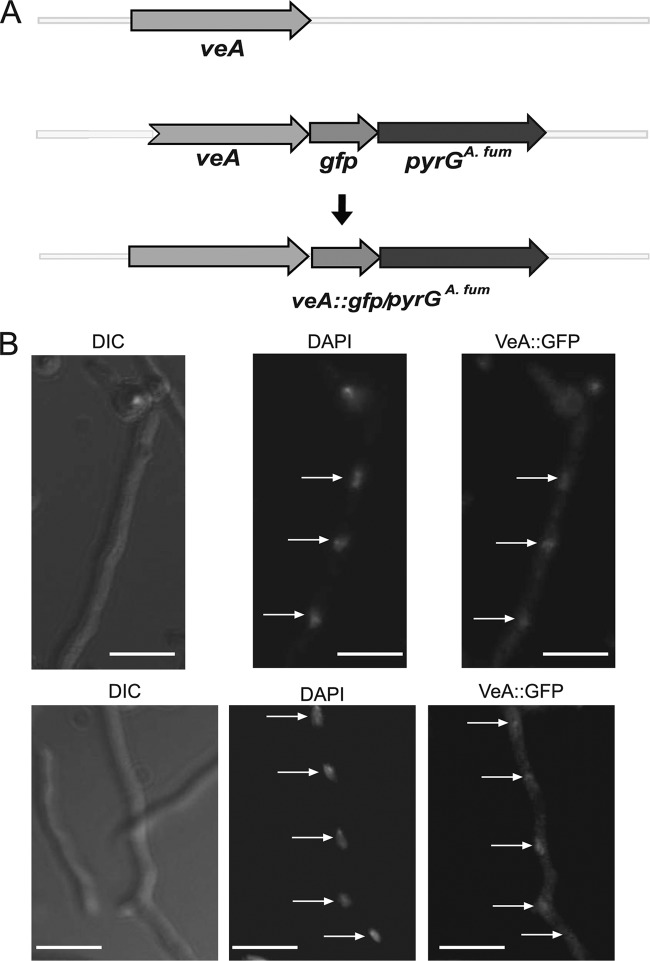

Subcellular localization of Aspergillus fumigatus VeA.

Previous studies in the model filamentous fungus A. nidulans have demonstrated that the VeA protein is transported to the nucleus, where it forms interactions with other proteins (4, 6, 85). With the purpose of elucidating the subcellular localization of VeA in A. fumigatus, we generated a strain containing VeA fused to GFP. Observations of this strain using fluorescence microscopy indicated that A. fumigatus VeA localizes in both cytoplasm and nuclei, preferentially accumulating in nuclei, as revealed by comparing images of micrographs with DAPI staining indicating nuclear location (Fig. 7). Similar results were obtained in light cultures (see Fig. S9 in the supplemental material), indicating that, differently from A. nidulans VeA, A. fumigatus VeA subcellular localization was light independent.

Fig 7.

Aspergillus fumigatus VeA preferentially localizes in nuclei. (A) Representation of the strategy to fuse GFP to VeA. The tagged construct was introduced at the veA locus by a double-recombination event. (B) Micrographs showing the subcellular localization of the VeA::GFP fusion described in panel A in A. fumigatus. From left to right, Nomarski images, DAPI images, and green fluorescence images are included. DAPI images were used as a nuclear localization internal control. Scale bars represent 10 μm. Arrows indicate nuclei.

Aspergillus fumigatus veA does not affect pathogenicity in the neutropenic mouse model.

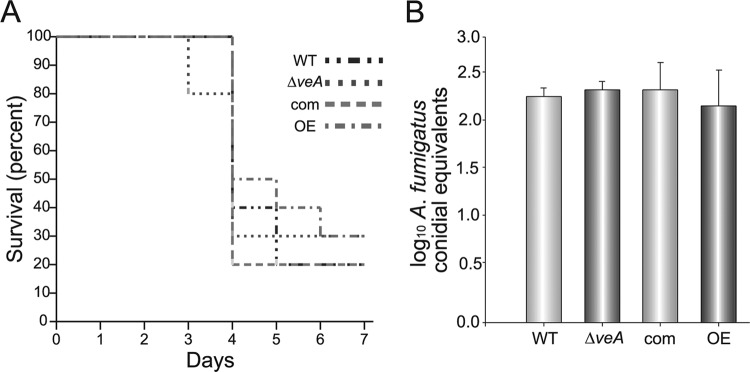

veA is necessary for virulence in different plant-pathogenic fungi (27, 54, 57, 96). Furthermore, a recent characterization of the H. capsulatum veA ortholog by Smulian's group in collaboration with our group showed for the first time that a veA ortholog is necessary for normal virulence in animals (49). In the present study, we investigated if veA was also a virulence factor in A. fumigatus in a neutropenic mouse model experiment. Seven days after infection with the wild-type, ΔveA, complemented, or OEveA strains, no significant differences in survival rates were detected among the strains (Fig. 8A).

Fig 8.

veA is dispensable in Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. (A) Neutropenic CD-1 mice were infected intranasally with conidia from Aspergillus fumigatus wild-type (WT), ΔveA, complementation (com), and OEveA (OE) strains. Survival rates are shown. (B) Fungal burden in mouse lungs measured by qPCR. DNA isolated from whole mouse lungs was used. The experiment included 10 mice per group.

The fungal burden in mouse lungs of dead or sacrificed animals 7 days after infection was measured by qPCR and normalized against values obtained from mice sacrificed just after infection. The data showed no significant difference in lung colonization levels among the A. fumigatus strains tested (Fig. 8B).

DISCUSSION

Aspergillus fumigatus is a primary causative agent of human infections. IA affects immunocompromised patients, resulting in a devastating disease with high mortality rates. Even with recent advances in medical technology, A. fumigatus infections are on the rise. This organism disseminates by producing abundant airborne conidia that can easily reach the lung alveoli due to their small size, leading to infection in immunosuppressed hosts (74, 76). In this study, we demonstrated that the global regulator veA is important for normal production of conidia. VeA has been shown to control development in other fungal species (6, 25, 26, 38, 39, 52). The role of veA as a negative regulator of asexual development has been particularly well characterized in the model fungus A. nidulans, where it was demonstrated that the light-dependent subcellular localization of the VeA protein controls the asexual/sexual developmental balance (4, 85). The deletion of veA in A. nidulans also affects the brlA α/β transcript ratio involved in the activation of conidiation (38). The reduction of conidiation in the A. fumigatus veA deletion strain observed in our studies is in agreement with previous work showing a nitrate-dependent reduction (45). However, differing from this report, our experiments indicated that veA overexpression resulted in an even more notable negative effect on conidiation. It is possible that this discrepancy could be due to the use of different culture media. A reduction of brlA expression in the deletion and overexpression strains parallels the differences in conidiation observed in Czapek Dox cultures. Similar to our findings, A. nidulans overexpression of the veA ortholog also led to a decrease in conidiation (39). Our study revealed that both abnormally high levels as well as the absence of the VeA regulator in A. fumigatus are detrimental for proper asexual development in this fungus. It is possible that a certain balanced stoichiometry with respect to other regulatory factors, perhaps with other VeA-interacting proteins (6, 7, 58) in the nucleus (Fig. 7), might be necessary for normal conidiation in this organism.

Differently from A. nidulans, where VeA control of morphogenesis is light dependent, in A. fumigatus this regulatory process was light independent, observing similar results in either dark or light cultures. With respect to sexual development, the A. fumigatus genome contains homologs of mating-type genes (70, 98), as well as other genes, such as nsdD (90), nsdC, or steA (data not shown), demonstrated to control sexual development in A. nidulans. Sexual development in A. fumigatus had been elusive until 2009, when O'Gorman et al. (59) described fruiting bodies in this fungus. In our study, A. fumigatus CEA10 did not reproduce sexually, and hence future research might be needed to demonstrate the possible role of VeA in A. fumigatus sexual development. It is known that A. fumigatus veA restores cleistothecial formation in the A. nidulans veA deletion mutant (45). This, together with the fact that veA controls sexual development in other fungal species (39, 49, 52, 99), suggests a role of veA in A. fumigatus sexual development.

Although veA regulates morphogenesis in A. fumigatus, only a small effect on growth was observed. Variation in veA expression did not affect the fungus response to pH or high levels of ROS, while veA orthologs in other fungal species are necessary for the genetic response to adapt and grow under these conditions (49, 99). In A. fumigatus, veA is not required for osmotic stress response either. This suggests that A. fumigatus might have a robust capacity to adapt to different environmental stresses using alternative veA-independent regulatory mechanisms that allow this fungus to survive. Cell wall integrity was not affected by veA in A. fumigatus, whereas in F. verticillioides deletion of the veA ortholog FvVE1 leads to defects in the cell wall that can be compensated for by osmotic stabilizers (52). Similar results were also observed in Acremonium chrysogenum veA ortholog studies (25).

Numerous studies have shown that VeA is also a master regulator of secondary metabolism in many fungal species (5, 16, 19, 25, 26, 38, 54, 56, 96, 99). In A. fumigatus, however, the involvement of VeA in secondary metabolism had not been investigated until now. Previous research revealed a role of fungal secondary metabolites as virulence factors during A. fumigatus lung colonization in immunosuppressed mice (81, 88). The most well known among these compounds is gliotoxin (3, 12, 20, 28, 29, 55, 62, 66, 72, 83, 86, 88, 92, 94, 101, 102). The gene cluster responsible for the synthesis of gliotoxin has been found (30). It is comprised of 22 genes and located in chromosome VI. Independent groups have disrupted the nonribosomal peptide synthase-encoding gene gliP within this cluster (22, 46, 88). These strains fail to produce gliotoxin. Similar results were obtained when gliZ, encoding a putative Zn2Cys2 binuclear transcription factor, also within this gene cluster, was deleted (12), suggesting that gliZ acts as specific positive regulator of the gliotoxin gene cluster. The location of genes encoding specific transcription factors in fungal secondary metabolic gene clusters is a common occurrence. One well-known example is aflR, encoding a transcription factor that activates the aflatoxin gene cluster in A. flavus and A. parasiticus and the sterigmatocystin gene cluster in A. nidulans (18, 64, 97, 103). In these and other fungi, the transcription factor within the clusters has been often found to be controlled by VeA (17), which is functionally connected to LaeA (6, 8). Our experiments indicated that VeA is required for wild-type levels of gliotoxin and that, similarly to the observed effect on conidiation, the absence or overexpression of veA has a negative effect on the production of this mycotoxin. Expression levels of gliP, used as an indicator of cluster activation, were downregulated in both veA deletion and veA overexpression strains. In our study, we also observed that VeA influences the expression of gliZ. The A. fumigatus strain lacking veA presented a reduction in gliZ expression with respect to the wild type, suggesting that abnormally low levels of gliZ in the ΔveA mutant are detrimental to the proper expression levels of the gliotoxin structural genes in the cluster and therefore negatively affect the production of this mycotoxin. Surprisingly, expression levels of gliZ were greater in the veA overexpression strain, in spite of the observed low levels of gliP expression and reduced gliotoxin accumulation. When gliZ was overexpressed in a veA wild-type background, high levels of both gliP and concomitant gliotoxin accumulation were observed. It is possible that veA in A. fumigatus could influence the expression of structural genes in the gliotoxin clusters by other unknown mechanisms in addition to the effect on the expression of gliZ. Detrimental effects on the production of certain secondary metabolites by both deletion and overexpression mutants of veA homologs have been previously reported. For example, in A. nidulans both deletion and overexpression of veA lead to a reduction in penicillin production (38, 82).

Other virulence factors that could influence A. fumigatus infection are hydrolytic enzymes (43). The action of some hydrolases facilitates tissue penetration in the infected A549 lung epithelial cell lines (42). Several proteases have been characterized in A. fumigatus with different effects on virulence (9, 35, 43). Deficiencies of elastolytic serine protease (43) or the protease secretion-deficient hacA mutant (73) presented a reduction in pathogenicity. As mentioned, whether VeA affects hydrolytic activity in A. fumigatus has not previously been investigated. Our study revealed that A. fumigatus ΔveA and OEveA strains present a notable reduction in protease activity, particularly the ΔveA strain, with only 10% activity with respect to the activity observed in the wild type. These results indicate an additional role of veA that has not been reported before in fungi—regulation of hydrolytic activity, in this case the protease activity in A. fumigatus.

Due to the fact that both deletion and overexpression of veA are detrimental to both gliotoxin production and protease activity, we predicted a decrease in pathogenicity in these mutants. Furthermore, the absence of LaeA, shown to interact with VeA in A. nidulans, resulted in a decrease in pathogenicity in neutropenic mice (11). Surprisingly, in our study neither ΔveA nor OEveA strains showed a difference in virulence with respect to the control strains. Fungal burden data showed the same ability to colonize the lungs in the ΔveA or OEveA strains compared to the control strains. It is possible that LaeA might control a separate set of virulence factors relevant in the neutropenic immunosuppressed environment—for example, secondary metabolites other than gliotoxin, control by both regulators (Fig. 3 and 11), or different characteristic of the spore surface (11). Although veA did not show a relevant role in pathogenicity in A. fumigatus, the veA ortholog in H. capsulatum was required for normal virulence in mice (49), suggesting that the role of veA in virulence might be different in other pathogenic fungi that affect animals and humans. It is also possible that although veA was not necessary for pathogenicity in neutropenic mice, this regulator could be important during A. fumigatus infection in nonneutropenic immunosuppressed hosts. Future studies will contribute to defining the relationship of VeA in infection in other immunosuppressed environments.

In conclusion, we have shown that A. fumigatus veA is a regulator of conidiation and also revealed veA as a positive regulator of gliotoxin, affecting expression of genes in the gliotoxin gene cluster. We have demonstrated that in A. fumigatus, protease activity is regulated by veA, a novel finding connecting this master regulator with fungal hydrolytic activity. Based on the conservation of VeA in other filamentous fungi, particularly in Ascomycetes, it is likely that VeA orthologs could affect hydrolytic activity in other fungal species. Another important observation is that alterations in veA expression (either deletion or overexpression of veA) did not, however, result in changes in pathogenicity under the experimental conditions tested, while deletion of the veA ortholog in other species, such as H. capsulatum (49), led to a reduction of virulence. This suggests that the possible use of VeA as a target in the design of a general strategy against a broad range of fungal infections might not be feasible and that although VeA still retains its high potential for this purpose, the role of VeA in pathogenicity must be studied on a case-by-case basis in different fungal species.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by NIH grant R03AI079496.

We thank Robert Cramer for helpful discussion, and we also thank Barbara Ball for technical support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 October 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abad A, et al. 2010. What makes Aspergillus fumigatus a successful pathogen? Genes and molecules involved in invasive aspergillosis. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 27: 155–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adams TH, Boylan MT, Timberlake WE. 1988. brlA is necessary and sufficient to direct conidiophore development in Aspergillus nidulans. Cell 54: 353–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Amitani R, et al. 1995. Purification and characterization of factors produced by Aspergillus fumigatus which affect human ciliated respiratory epithelium. Infect. Immun. 63: 3266–3271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Araujo-Bazan L, et al. 2009. Importin alpha is an essential nuclear import carrier adaptor required for proper sexual and asexual development and secondary metabolism in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 46: 506–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baba S, Kinoshita H, Nihira T. 2012. Identification and characterization of Penicillium citrinum VeA and LaeA as global regulators for ML-236B production. Curr. Genet. 58: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bayram Ö, et al. 2008. VelB/VeA/LaeA complex coordinates light signal with fungal development and secondary metabolism. Science 320: 1504–1506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bayram Ö, Braus GH, Fischer R, Rodriguez-Romero J. 2010. Spotlight on Aspergillus nidulans photosensory systems. Fungal Genet. Biol. 47: 900–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bayram Ö, Braus GH. 2012. Coordination of secondary metabolism and development in fungi: the velvet family of regulatory proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36: 1–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bergmann A, Hartmann T, Cairns T, Bignell EM, Krappmann S. 2009. A regulator of Aspergillus fumigatus extracellular proteolytic activity is dispensable for virulence. Infect. Immun. 77: 4041–4050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bernard M, Latge JP. 2001. Aspergillus fumigatus cell wall: composition and biosynthesis. Med. Mycol. 39: 9–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bok JW, et al. 2005. LaeA, a regulator of morphogenetic fungal virulence factors. Eukaryot. Cell 4: 1574–1582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bok JW, et al. 2006. GliZ, a transcriptional regulator of gliotoxin biosynthesis, contributes to Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. Infect. Immun. 74: 6761–6768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bowman JC, et al. 2001. Quantitative PCR assay to measure Aspergillus fumigatus burden in a murine model of disseminated aspergillosis: demonstration of efficacy of caspofungin acetate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45: 3474–3481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brakhage AA, Langfelder K, Wanner G, Schmidt A, Jahn B. 1999. Pigment biosynthesis and virulence. Contrib. Microbiol. 2: 205–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Calvo AM, Wilson RA, Bok JW, Keller NP. 2002. Relationship between secondary metabolism and fungal development. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66: 447–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Calvo AM, Bok J, Brooks W, Keller NP. 2004. veA is required for toxin and sclerotial production in Aspergillus parasiticus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70: 4733–4739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Calvo AM. 2008. The VeA regulatory system and its role in morphological and chemical development in fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45: 1053–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang PK, Ehrlich KC, Yu JJ, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland TE. 1995. Increased expression of Aspergillus parasiticus aflr, encoding a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein, relieves nitrate inhibition of aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61: 2372–2377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chettri P, et al. 2012. The veA gene of the pine needle pathogen Dothistroma septosporum regulates sporulation and secondary metabolism. Fungal Genet. Biol. 49: 141–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Comera C, et al. 2007. Gliotoxin from Aspergillus fumigatus affects phagocytosis and the organization of the actin cytoskeleton by distinct signalling pathways in human neutrophils. Microbes Infect. 9: 47–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Costa C, et al. 2001. Development of two real-time quantitative TaqMan PCR assays to detect circulating Aspergillus fumigatus DNA in serum. J. Microbiol. Methods 44: 263–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cramer RA, et al. 2006. Disruption of a nonribosomal peptide synthetase in Aspergillus fumigatus eliminates gliotoxin production. Eukaryot. Cell 5: 972–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dagenais TRT, Keller NP. 2009. Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 22: 447–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Denning DW. 1998. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26: 781–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dreyer J, Eichhorn H, Friedlin E, Kuernsteiner H, Kueck U. 2007. A homologue of the Aspergillus velvet gene regulates both cephalosporin C biosynthesis and hyphal fragmentation in Acremonium chrysogenum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73: 3412–3422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Duran RM, Cary JW, Calvo AM. 2007. Production of cyclopiazonic acid, aflatrem, and aflatoxin by Aspergillus flavus is regulated by veA, a gene necessary for sclerotial formation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 73: 1158–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Duran RM, Cary JW, Calvo AM. 2009. The role of veA in Aspergillus flavus infection of peanut, corn and cotton. Open Mycol. J. 3: 27–36 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eichner RD, Waring P, Geue AM, Braithwaite AW, Mullbacher A. 1988. Gliotoxin causes oxidative damage to plasmid and cellular DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 263: 3772–3777 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Frame R, Carlton WW. 1988. Acute toxicity of gliotoxin in hamsters. Toxicol. Lett. 40: 269–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gardiner DM, Howlett BJ. 2005. Bioinformatic and expression analysis of the putative gliotoxin biosynthetic gene cluster of Aspergillus fumigatus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 248: 241–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hohl TM, Feldmesser M. 2007. Aspergillus fumigatus: principles of pathogenesis and host defense. Eukaryot. Cell 6: 1953–1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hu W, et al. 2007. Essential gene identification and drug target prioritization in Aspergillus fumigatus. PloS Pathog. 3: e24 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jahn B, et al. 1997. Isolation and characterization of a pigmentless-conidium mutant of Aspergillus fumigatus with altered conidial surface and reduced virulence. Infect. Immun. 65: 5110–5117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jahn B, et al. 2000. Interaction of human phagocytes with pigmentless Aspergillus conidia. Infect. Immun. 68: 3736–3739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jatonogay K, et al. 1994. Cloning and disruption of the gene encoding an extracellular metalloprotease of Aspergillus-fumigatus. Mol. Microbiol. 14: 917–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jin J, Lee YK, Wickes BL. 2004. Simple chemical extraction method for DNA isolation from Aspergillus fumigatus and other Aspergillus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42: 4293–4296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Käfer E. 1977. Meiotic and mitotic recombination in Aspergillus and its chromosomal aberrations. Adv. Genet. 19: 33–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kato N, Brooks W, Calvo AM. 2003. The expression of sterigmatocystin and penicillin genes in Aspergillus nidulans is controlled by veA, a gene required for sexual development. Eukaryot. Cell 2: 1178–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim HS, et al. 2002. The veA gene activates sexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 37: 72–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim K-H, et al. 2009. Tmpl, a transmembrane protein required for intracellular redox homeostasis and virulence in a plant and an animal fungal pathogen. PloS Pathog. 5: e1000653 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kliasova GA, et al. 2005. Invasive pulmonary aspergillesis. Terapevticheskii Arkhiv. 77: 65–71. (In Russian.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kogan TV, Jadoun J, Mittelman L, Hirschberg K, Osherov N. 2004. Involvement of secreted Aspergillus fumigatus proteases in disruption of the actin fiber cytoskeleton and loss of focal adhesion sites in infected A549 lung pneumocytes. J. Infect. Dis. 189: 1965–1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kolattukudy PE, et al. 1993. Evidence for possible involvement of an elastolytic serine-protease in aspergillosis. Infect. Immun. 61: 2357–2368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kontoyiannis DP, Bodey GP. 2002. Invasive aspergillosis in 2002: an update. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 21: 161–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Krappmann S, Bayram O, Braus GH. 2005. Deletion and allelic exchange of the Aspergillus fumigatus veA locus via a novel recyclable marker module. Eukaryot. Cell 4: 1298–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kupfahl C, et al. 2006. The gliP gene of Aspergillus fumigatus is essential for gliotoxin production but has no effect on pathogenicity of the fungus in a mouse infection model of invasive aspergillosis. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 296: 73–8116476569 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kwon-Chung KJ, Sugui JA. 2009. What do we know about the role of gliotoxin in the pathobiology of Aspergillus fumigatus? Med. Mycol. 47: S97–S103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Langfelder K, et al. 1998. Identification of a polyketide synthase gene (pksP) of Aspergillus fumigatus involved in conidial pigment biosynthesis and virulence. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 187: 79–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Laskowski-Peak MC, Calvo AM, Rohrssen J, Smulian GA. 2012. VEA1 is required for cleistothecial formation and virulence in Histoplasma capsulatum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 49: 836–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Latge JP. 1999. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12: 310–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Latge JP. 2001. The pathobiology of Aspergillus fumigatus. Trends Microbiol. 9: 382–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Li S, et al. 2006. FvVE1 regulates filamentous growth, the ratio of microconidia to macroconidia and cell wall formation in Fusarium verticillioides. Mol. Microbiol. 62: 1418–1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Marr KA, Carter RA, Boeckh M, Martin P, Corey L. 2002. Invasive aspergillosis in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients: changes in epidemiology and risk factors. Blood 100: 4358–4366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Merhej J, et al. 2012. The velvet gene, FgVe1, affects fungal development and positively regulates trichothecene biosynthesis and pathogenicity in Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13: 363–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mullbacher A, Eichner RD. 1984. Immunosuppression in vitro by a metabolite of a human pathogenic fungus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 81: 3835–3837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Myung K, et al. 2009. Fvve1 regulates biosynthesis of the mycotoxins fumonisins and fusarins in Fusarium verticillioides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57: 5089–5094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Myung K, et al. 2012. The conserved global regulator VeA is necessary for symptom production and mycotoxin synthesis in maize seedlings by Fusarium verticillioides. Plant Pathol. 61: 152–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ni M, Yu J-H. 2007. A novel regulator couples sporogenesis and trehalose biogenesis in Aspergillus nidulans. Plos One 2: e970 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. O'Gorman CM, Fuller HT, Dyer PS. 2009. Discovery of a sexual cycle in the opportunistic fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Nature 457: 471–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Oren I, Goldstein N. 2002. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 8: 195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pagano L, et al. 2001. Infections caused by filamentous fungi in patients with hematologic malignancies. A report of 391 cases by GIMEMA Infection Program. Haematologica 86: 862–870 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pan XQ, Harday J. 2007. Electromicroscopic observations on gliotoxin-induced apoptosis of cancer cells in culture and human cancer xenografts in transplanted SCID mice. In Vivo 21: 259–265 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Paris S, et al. 2003. Catalases of Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect. Immun. 71: 3551–3562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Payne GA, Nystrom GJ, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland TE, Woloshuk CP. 1993. Cloning of the afl-2 gene involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis from Aspergillus flavus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59: 156–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Peñalva MA. 2005. Tracing the endocytic pathway of Aspergillus nidulans with FM4-64. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42: 963–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Piva TJ. 1994. Gliotoxin induces apoptosis in mouse l929 fibroblast cells. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 33: 411–419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Post MJ, Lass-Floerl C, Gastl G, Nachbaur D. 2007. Invasive fungal infections in allogeneic and autologous stem cell transplant recipients: a single-center study of 166 transplanted patients. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 9: 189–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Purschwitz J, et al. 2008. Functional and physical interaction of blue- and red-light sensors in Aspergillus nidulans. Curr. Biol. 18: 255–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Puttikamonkul S, et al. 2010. Trehalose 6-phosphate phosphatase is required for cell wall integrity and fungal virulence but not trehalose biosynthesis in the human fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Mol. Microbiol. 77: 891–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Pyrzak W, Miller KY, Miller BL. 2008. Mating type protein Mat1-2 from asexual Aspergillus fumigatus drives sexual reproduction in fertile Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot. Cell 7: 1029–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Reichard U, Monod M, Odds F, Ruchel R. 1997. Virulence of an aspergillopepsin-deficient mutant of Aspergillus fumigatus and evidence for another aspartic proteinase linked to the fungal cell wall. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 35: 189–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Richard JL, Dvorak TJ, Ross PF. 1996. Natural occurrence of gliotoxin in turkeys infected with Aspergillus fumigatus, Fresenius. Mycopathologia 134: 167–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Richie DL, et al. 2009. A role for the unfolded protein response (upr) in virulence and antifungal susceptibility in Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathog. 5: e1000258 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ruchel R, Reichard U. 1999. Pathogenesis and clinical presentation of aspergillosis. Contrib. Microbiol. 2: 21–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 76. Samson RA. 1999. The genus Aspergillus with special regard to the Aspergillus fumigatus group. Contrib. Microbiol. 2: 5–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Schmitt HJ, Blevins A, Sobeck K, Armstrong D. 1990. Aspergillus species from hospital air and from patients. Mycoses 33: 539–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 3: 1101–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sherif R, Segal BH. 2010. Pulmonary aspergillosis: clinical presentation, diagnostic tests, management and complications. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 16: 242–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Soriani FM, et al. 2008. Functional characterization of the Aspergillus fumigatus CRZ1 homologue, CrzA. Mol. Microbiol. 67: 1274–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Spikes S, et al. 2008. Gliotoxin production in Aspergillus fumigatus contributes to host-specific differences in virulence. J. Infect. Dis. 197: 479–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sproete P, Brakhage AA. 2007. The light-dependent regulator velvet A of Aspergillus nidulans acts as a repressor of the penicillin biosynthesis. Arch. Microbiol. 188: 69–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Stanzani M, et al. 2005. Aspergillus fumigatus suppresses the human cellular immune response via gliotoxin-mediated apoptosis of monocytes. Blood 105: 2258–2265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Steinbach WJ, et al. 2007. Calcineurin inhibition or mutation enhances cell wall inhibitors against Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51: 2979–2981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Stinnett SM, Espeso EA, Cobeno L, Araujo-Bazan L, Calvo AM. 2007. Aspergillus nidulans VeA subcellular localization is dependent on the importin alpha carrier and on light. Mol. Microbiol. 63: 242–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Suen YK, Fung KP, Lee CY, Kong SK. 2001. Gliotoxin induces apoptosis in cultured macrophages via production of reactive oxygen species and cytochrome c release without mitochondrial depolarization. Free Radic. Res. 35: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Sugareva V, et al. 2006. Characterisation of the laccase-encoding gene abr2 of the dihydroxynaphthalene-like melanin gene cluster of Aspergillus fumigatus. Arch. Microbiol. 186: 345–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Sugui JA, et al. 2007. Gliotoxin is a virulence factor of Aspergillus fumigatus: gliP deletion attenuates virulence in mice immunosuppressed with hydrocortisone. Eukaryot. Cell 6: 1562–1569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Szewczyk E, et al. 2006. Fusion PCR and gene targeting in Aspergillus nidulans. Nat. Protoc. 1: 3111–3120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Szewczyk E, Krappmann S. 2010. Conserved regulators of mating are essential for Aspergillus fumigatus cleistothecium formation. Eukaryot. Cell 9: 774–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Tsai HF, Wheeler MH, Chang YC, Kwon-Chung KJ. 1999. A developmentally regulated gene cluster involved in conidial pigment biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Bacteriol. 181: 6469–6477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Tsunawaki S, Yoshida LS, Nishida S, Kobayashi T, Shimoyama T. 2004. Fungal metabolite gliotoxin inhibits assembly of the human respiratory burst NADPH oxidase. Infect. Immun. 72: 3373–3382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Valiante V, Heinekamp T, Jain R, Haertl A, Brakhage AA. 2008. The mitogen-activated protein kinase MpkA of Aspergillus fumigatus regulates cell wall signaling and oxidative stress response. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45: 618–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Waring P. 1990. DNA fragmentation induced in macrophages by gliotoxin does not require protein-synthesis and is preceded by raised inositol triphosphate levels. J. Biol. Chem. 265: 14476–14480 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wiederhold NP, Lewis RE. 2003. Invasive aspergillosis in patients with hematologic malignancies. Pharmacotherapy 23: 1592–1610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Wiemann P, et al. 2010. FfVel1 and FfLae1, components of a velvet-like complex in Fusarium fujikuroi, affect differentiation, secondary metabolism and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 77: 972–994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Woloshuk CP, Yousibova GL, Rollins JA, Bhatnagar D, Payne GA. 1995. Molecular characterization of the AFL-1 locus in Aspergillus flavus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61: 3019–3023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Wortman JR, et al. 2006. Whole genome comparison of the A. fumigatus family. Med. Mycol. 44: S3–S7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Wu D, Oide S, Zhang N, Choi MY, Turgeon BG. 2012. ChLae1 and ChVel1 regulate T-toxin production, virulence, oxidative stress response, and development of the maize pathogen Cochliobolus heterostrophus. PLoS Pathog. 8: e1002542 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Yager LN. 1992. Early developmental events during asexual and sexual sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Biotechnology (Reading, MA) 23: 19–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Yamada A, Kataoka T, Nagai K. 2000. The fungal metabolite gliotoxin: immunosuppressive activity on CTL-mediated cytotoxicity. Immunol. Lett. 71: 27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Yoshida LS, Abe S, Tsunawaki S. 2000. Fungal gliotoxin targets the onset of superoxide-generating NADPH oxidase of human neutrophils. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 268: 716–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Yu JH, et al. 1996. Conservation of structure and function of the aflatoxin regulatory gene aflR from Aspergillus nidulans and A. flavus. Curr. Genet. 29: 549–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.