Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study (GSK ADA111194) was to compare asthma-related health care utilization and costs associated with fluticasone propionate (an inhaled corticosteroid [ICS]) and salmeterol (a long-acting beta-agonist) in a single inhalation device (fluticasone propionate-salmeterol) versus the combination of ICS + montelukast in the treatment of pediatric patients with asthma.

Methods

This was a retrospective, observational cohort study using a large health insurance claims database spanning January 1, 2000 to January 31, 2008. The target population was patients aged 4–11 years with at least one pharmacy claim for fluticasone propionate-salmeterol, any ICS, or montelukast during the study period. The date of first claim for the medication of interest was deemed the index date. Patients were required to be continuously eligible to receive health care services one year prior to and 30 days after the index date, and have at least one claim with an ICD-9-CM code for asthma (493.xx) in the one-year pre-index period. Patients with prescriptions for fluticasone propionate-salmeterol, ICS + montelukast, or long-acting beta-agonists during the pre-index period were excluded. Patients were matched on a 1:1 basis according to three variables, ie, pre-index use of oral corticosteroids, ICS, and presence of pre-index respiratory-related hospitalizations/emergency department visits. The risk of asthma-related hospitalization, combined hospitalization/emergency department visit, and monthly asthma-related costs were assessed using multivariate methods.

Results

Of the 3001 patients identified, 2231 patients were on fluticasone propionate-salmeterol and 770 were on ICS + montelukast. After matching, there were 747 pairs of fluticasone propionate-salmeterol and ICS + montelukast patients, which were well matched for baseline characteristics. Patients who started fluticasone propionate-salmeterol compared with patients on ICS + montelukast had a significantly (P < 0.02) lower rate of asthma-related hospitalizations (0.3% versus 3.5%) and asthma-related hospitalizations/emergency department visits (3.5% versus 5.7%). After controlling for baseline and patient characteristics, fluticasone propionate-salmeterol users were associated with a significantly lower risk of an asthma-related hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio 0.039; 95% confidence interval 0.004–0.408) or hospitalization/emergency department visit (hazard ratio 0.441; 95% confidence interval 0.225–0.864), and $151 (95% confidence interval 67–346) lower asthma-related monthly costs compared with ICS + montelukast.

Conclusion

In patients aged 4–11 years with asthma, use of fluticasone propionate-salmeterol was associated with lower asthma-related health care utilization and costs compared with use of ICS + montelukast.

Keywords: fluticasone propionate, salmeterol, montelukast, inhaled corticosteroids, asthma, pediatric, outcomes, asthma

Introduction

The prevalence of asthma has increased by more than 75% over the last two decades,1 with rates in children under 5 years increasing by more than 160%.2 In fact, asthma is the leading serious chronic illness of childhood in the United States.1 In 2006, an estimated 6.8 million children under the age of 18 years (almost 1.2 million under the age of 5 years) had asthma.1 Asthma is the third leading cause of hospitalization among children younger than 15 years, and is also associated with increases in emergency department visits.1

Although the economic burden of hospitalizations and emergency department visits is substantial, asthma-related prescription drug costs represent the largest single direct health care expenditure related to asthma.2 According to current treatment guidelines, anti-inflammatory agents (eg, corticosteroids, cromolyn, leukotriene receptor agonists) and bronchodilators (eg, long-acting beta agonists, methylxanthines, anticholinergics) are the generally recommended agents.3,4 The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3 states that inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the most effective long-term control medication across all age groups and are the preferred treatment for children aged 5–11 years with persistent asthma. For children whose symptoms are not adequately controlled with low-dose to medium-dose ICS monotherapy, add-on therapy with a long-acting beta-agonist or a leukotriene receptor agonist is recommended.3

Concordant with these recommendations, ICS have become the predominant form of initial maintenance therapy in asthmatic children,5,6 with combination use of long-acting beta-agonists and leukotriene receptor agonists increasing with ICS over the last decade.7,8

Although the utilization of leukotriene receptor agonists is on the rise, randomized controlled trials have found that addition of a long-acting beta-agonist to a regimen containing low-dose ICS is significantly more efficacious than adding a leukotriene receptor agonist in terms of better improvement in pulmonary function, asthma symptoms, supplemental use of short-acting beta agonists, frequency of exacerbations, and overall satisfaction with treatment.9–11 The BADGER (Best Add-On Therapy Giving Effective Response) trial assessed outcomes associated with three blinded step-up treatments in children who had uncontrolled asthma while receiving low-dose ICS, and revealed that step-up treatment to a long-acting beta-agonist had the best response compared with leukotriene receptor agonist step-up and ICS step-up.12 Furthermore, naturalistic studies using insurance claims data have reported that in patients receiving ICS monotherapy, add-on therapy with salmeterol is associated with better outcomes and reduced health care costs compared with add-on therapy using a leukotriene receptor agonist.13,14

In 2001, the launch of a combination product of fluticasone propionate and salmeterol (fluticasone propionate-salmeterol) in a single inhalation device dramatically changed the treatment armamentarium for asthma. Clinical trials comparing the fluticasone propionate-salmeterol combination with ICS + montelukast showed that the fluticasone propionate-salmeterol regimen provided better overall asthma control in terms of pulmonary function and use of short-acting beta agonists.15–17 In addition, a cost-effectiveness analysis based on clinical trial data found fluticasone propionate-salmeterol to be the dominant therapy (ie, less costly and more effective) versus fluticasone propionate + montelukast.15,16 From a real-world clinical practice perspective, Delea et al suggested that in patients with asthma symptoms inadequately controlled with ICS monotherapy, switching to fluticasone propionate-salmeterol was associated with reduced utilization and costs of asthma-related care, and improved adherence compared with adding montelukast.18

Although the above studies indicate potential differences between fluticasone propionate-salmeterol and ICS + montelukast, they were all based on data in the adolescent and adult population, which may not be generalizable to a pediatric practice setting. The present trial (GSK ADA111194) is the first head-to-head study in a pediatric population to determine the comparative effect on health care utilization and costs of fluticasone propionate-salmeterol versus ICS + montelukast.

Materials and methods

A retrospective longitudinal analysis of pharmacy and medical claims data was conducted to assess asthma-related health care utilization and costs associated with pediatric asthmatic patients receiving fluticasone propionate-salmeterol in a single device versus ICS + montelukast.

Data source

Medical and pharmacy claims data were abstracted from the IMS Life Link Health Plans Claims Database. This commercial claims database is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and is nationally representative, encompassing more than 60 million patients from over 95 managed care plans in the United States. Information includes inpatient and outpatient diagnoses as determined by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes, and procedures as determined by Current Procedural Terminology 4 (CPT-4) codes, as well as prescription records. Dates of service and both paid and charged amounts were available for all services rendered. Data from January 1, 2000, to January 31, 2008, were used in this analysis.

Selection of patients

Patients aged 4–11 years with at least one pharmacy claim for fluticasone propionate-salmeterol, any ICS (ie, beclomethasone, budesonide, flunisolide, fluticasone propionate, triamcinolone, or mometasone) or montelukast between January 1, 2001 and September 30, 2007 (ie, enrolment period) were eligible for study inclusion. The index date for each patient was defined as the first chronologically occurring prescription of interest during this period. Patients were also required to be continuously eligible to receive health care services one year prior to and 120 days after the index date and have at least one claim with an ICD-9-CM code for asthma (493.xx) in the one-year period prior to index date. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they received fluticasone propionate-salmeterol, ICS + montelukast, another long-acting beta-agonist, or combination product of budesonide-formoterol during the one-year period prior to index date.

Patients were then placed into cohorts based upon pharmacotherapy patterns during the first 30-day period post index date. Patients receiving fluticasone propionate-salmeterol within this period were classified as such, while patients were deemed to be on combination therapy if they received an ICS and montelukast within this period, regardless of the index prescription. Within each cohort, 31–90 days post index date was utilized to ensure patients had at least one additional index prescription. Additional patients were excluded if they received another controller medication other than index medication during the 30-day period post index date or if they had a respiratory-related hospitalization or emergency department visit (ICD-9-CM codes 466.xx, 48x.xx, 49x.xx) during that same time period.

Comorbidities and disease severity assessment

Patient comorbidities and disease severity were evaluated during the one-year pre-index date period. The Charlson comorbidity index with the Dartmouth-Manitoba and Deyo modification19,20 was utilized to measure comorbidity status. This index includes 19 medical conditions, each assigned with a weight scale ranging from 1 to 6. The maximum possible score ranges from 0 to 33. Higher scores correlate with a greater burden of comorbidities.

The presence of allergic rhinitis (ICD-9-CM code 477.x) and number of unique classes of allergic rhinitis medications received (intranasal corticosteroids, oral nonsedating antihistamines, sedating antihistamines, leukotriene modifiers, cromones, and decongestants) were also flagged as key comorbidity measures.

Asthma severity was determined using proxy measures, which included presence and number of canisters of inhaled short-acting beta agonists, number of prescriptions for oral corticosteroids, ICS prescription count, number of hospitalizations/emergency department visits for respiratory-related conditions, and total costs for respiratory-related conditions.

Patient matching

Patients eligible for study inclusion were exactly matched in a 1:1 ratio (fluticasone propionate-salmeterol to ICS + montelukast) on three key variables measured in the pre-index date period: presence of oral corticosteroid use (yes/no), presence of ICS use (yes/no), and occurrence of respiratory-related hospitalizations/emergency department visits (yes/no).

Analysis of outcomes

The presence and timing (in days) of an asthma-related hospitalization (primary ICD-9-CM code of 493.xx) and asthma-related hospitalization/emergency department visit as a combined endpoint were the primary outcomes of interest that were assessed via survival analysis techniques. Each patient had variable follow-up time, which was computed as the time between start date of the follow-up period (ie, day after the end of the 30-day period post index date) and the date of the first outcome or the date a patient was censored. Patients were deemed to be censored or lost to follow-up when they discontinued receiving their index therapy (defined as a gap in therapy greater than 90 days between prescriptions). Patients’ time was also censored if they switched controller therapies, they were no longer eligible to receive health care services from the health plan, or the patients’ follow-up time surpassed the end of the study period. Time to each event of interest among the cohorts was modeled as a function of patient age, Charlson comorbidity index, geographic location (ie, East, Midwest, South, West), gender, presence of allergic rhinitis, number of canisters of inhaled short-acting beta agonists, oral corticosteroid prescription count, ICS prescription count, and number of hospitalizations/emergency department visits for respiratory-related conditions using a Cox proportional hazards model.

Asthma-related medical costs (primary ICD-9-CM code 493.xx) were defined as the amount paid by the health plan for the following services: physician visits, inpatient hospitalizations, outpatient hospital care, emergency department visits, and other services. Asthma-related pharmacy costs were also computed and included the amount paid by the health plan for any controller or rescue medications used to treat asthma. Because follow-up times differed from patient to patient, monthly average medical and pharmacy costs were calculated for each patient and standardized to 2007 US dollars. Statistical differences in monthly costs were determined by a gamma-distributed generalized linear model with a log-link function, controlling for variations in the same covariates mentioned above plus medical and pharmacy costs measured in the one-year period prior to index date. Differences in the demographic characteristics across cohorts were assessed utilizing Chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC), with an a priori significance level of P = 0.05.

Results

Demographics

Initially, a total of 3001 patients were identified who met study criteria (Table 1). Nearly three-quarters had initiated fluticasone propionate-salmeterol (74.3%, n = 2231) and one-quarter (25.7%, n = 770), combination ICS + montelukast. Due to the large differences between the two cohorts in the presence of oral corticosteroid use (21.6% versus 40.5%), presence of ICS use (5.4% versus 14.9%), and presence of respiratory-related hospitalization or emergency department visit (11.9% versus 22.6%), a 1:1 match was employed. After the match, a total of 1494 patients remained (747 in each cohort). Table 2 shows no statistically significant differences between cohorts on background variables, except for age and presence of allergic rhinitis. Patients in the ICS + montelukast cohort were, on average, 2.3 years younger than those in the fluticasone propionate-salmeterol cohort (6.2 years versus 8.5 years). The ICS + montelukast cohort had a higher proportion of patients with allergic rhinitis compared with the fluticasone propionate-salmeterol cohort.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study sample at baseline

| Fluticasone propionate-salmeterol (n = 2231) | ICS + montelukast (n = 770) | Total (n = 3001) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, year, mean (SD) | 8.7a | (1.9) | 6.2 | (2.1) | 8.0 | (2.2) |

| Female (n, %) | 871 | 39.0% | 301 | 39.1% | 1172 | 39.1% |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Charlson index in pre-index period (mean, SD) | 1.1 | (0.6) | 1.2 | (0.8) | 1.1 | (0.7) |

| Concomitant AR | 991 | 44.4% | 368 | 47.8% | 1359 | 45.3% |

| Number of classes of AR medicationsb (mean, SD) | 1.1 | (0.9) | 1.1 | (0.9) | 1.1 | (0.9) |

| Asthma severity in pre-index period | ||||||

| Presence of SABA use, n (%) | 1330 | 59.6% | 487 | 63.3% | 1817 | 60.6% |

| Number of SABA canisters, mean (SD) | 1.4 | (1.7) | 0.7 | (1.1) | 1.3 | (1.6) |

| Presence of OCS use, n (%) | 482a | 21.6% | 312 | 40.5% | 794 | 26.5% |

| Number of OCS prescriptions, mean (SD) | 1.5 | (0.9) | 1.7 | (1.1) | 1.6 | (1.0) |

| Presence of ICS use, n (%) | 120a | 5.4% | 115 | 14.9% | 235 | 7.8% |

| Number of ICS canisters, mean (SD) | 2.1 | (1.8) | 2.7 | (2.3) | 2.4 | (2.1) |

| Patients with respiratory-related hospitalization or ED, n (%) | 266a | 11.9% | 174 | 22.6% | 440 | 14.7% |

| Number of hospitalizations/ED visits for respiratory-related conditions, mean (SD) | 0.2 | (0.5) | 0.3 | (0.7) | 0.2 | (0.5) |

| Total medical costs for respiratory-related conditions, mean (SD) | $992a | ($4291) | $1785 | ($4919) | $1196 | ($4473) |

| Pharmacy costs for asthma medications, mean (SD) | $90a | ($186) | $194 | ($418) | $117 | ($269) |

Notes:

P < 0.05 when compared with ICS + montelukast; based on Chi-square test or t-test;

mean computed among those with a diagnosis of allergic rhinitis.

Abbreviations: AR, allergic rhinitis; ED, emergency department; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting beta agonist; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of matched study sample at baseline

| Characteristics | Fluticasone propionate-salmeterol (n = 747) | ICS + montelukast (n = 747) | Total (n = 1494) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, years, mean, (SD) | 8.5a | (1.9) | 6.2 | (2.1) | 7.4 | (2.3) |

| Female, n (%) | 293 | 39.2% | 292 | 39.1% | 585 | 39.2% |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Charlson index in pre-index period, mean (SD) | 1.1 | (0.6) | 1.2 | (0.8) | 1.1 | (0.7) |

| Concomitant AR | 314a | 42.0% | 358 | 47.9% | 672 | 45.0% |

| Number of classes of AR medicationsb (mean, SD) | 0.8 | (0.8) | 0.8 | (0.9) | 0.8 | (0.9) |

| Asthma severity in pre-index period | ||||||

| Presence of SABA use, n (%) | 502 | 67.2% | 466 | 62.4% | 968 | 64.8% |

| Number of SABA canisters, mean (SD) | 1.0 | (1.5) | 0.4 | (0.9) | 0.7 | (1.3) |

| Presence of OCS use, n (%) | 289 | 38.7% | 289 | 38.7% | 578 | 38.7% |

| Number of OCS prescriptions, mean (SD) | 0.6 | (0.9) | 0.7 | (1.1) | 0.6 | (1.0) |

| Presence of ICS use, n (%) | 92 | 12.3% | 92 | 12.3% | 184 | 12.3% |

| Number of ICS canisters, mean (SD) | 0.3 | (1.0) | 0.3 | (1.2) | 0.3 | (1.1) |

| Patients with respiratory-related hospitalization or ER, n (%) | 165 | 22.1% | 165 | 22.1% | 330 | 22.1% |

| Number of hospital/ED visits for respiratory-related conditions, mean (SD) | 0.3 | (0.6) | 0.3 | (0.7) | 0.3 | (0.7) |

| Total medical costs for respiratory-related conditions, mean (SD) | $1522 | ($4993) | $1757 | ($4937) | $1640 | ($4965) |

| Pharmacy costs for asthma medications, mean (SD) | $140 | ($254) | $169 | ($363) | $155 | ($314) |

Notes:

P < 0.05 when compared with ICS + montelukast;

mean computed among those with a diagnosis of allergic rhinitis.

Abbreviations: AR, allergic rhinitis; ED, emergency department; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting beta agonist; SD, standard deviation.

Assessment of asthma-related health care utilization

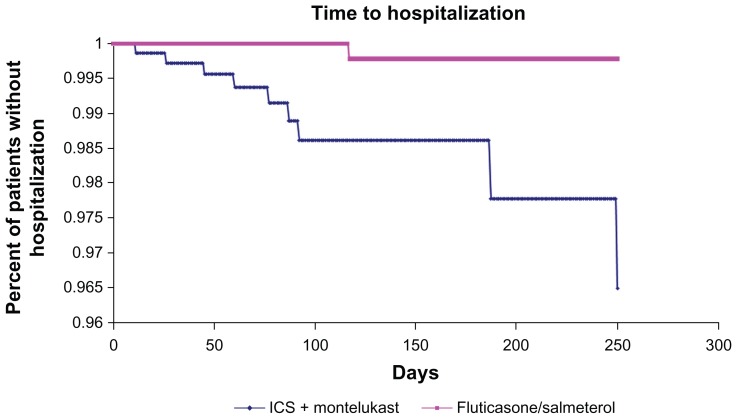

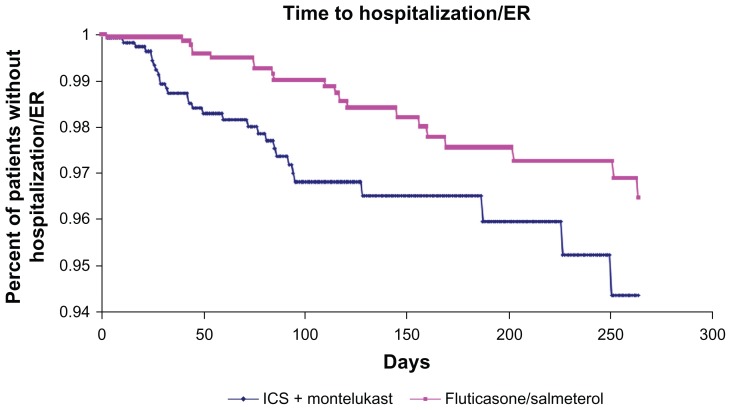

The adjusted survival curves displayed in Figure 1 show that the rate of asthma-related hospitalizations was significantly lower in the fluticasone propionate-salmeterol cohort compared with the ICS + montelukast cohort (0.3% versus 3.5%). Likewise, the rate of the combined endpoint of hospitalization/emergency department visit was also significantly lower in the fluticasone propionate-salmeterol cohort compared with the ICS + montelukast cohort (Figure 2, 3.5% versus 5.7%). After controlling for background covariates, patients receiving fluticasone propionate-salmeterol had a 96% (hazard ratio [HR] 0.039; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.004–0.428; P = 0.008) lower risk of experiencing an asthma-related hospitalization compared with patients receiving ICS + montelukast (see Supplementary Table 1A for full model results). The fluticasone propionate-salmeterol cohort also had a 56% lower risk of experiencing an asthma-related hospitalization/emergency department visit (HR 0.441; 95% CI 0.225–0.864; P = 0.0169, see Supplementary Table 1B for full model results).

Figure 1.

Time to first asthma related hospitalization for each cohort over the follow-up period.

Abbreviation: ICS, inhaled corticosteroid.

Figure 2.

Time to first combined asthma related hospitalization or emergency room visit for each cohort over the follow-up period.

Abbreviations: ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; ER, emergency room.

Assessment of asthma-related costs

After adjusting for background covariates, patients in the ICS + montelukast cohort, on average, incurred a cost of $121 per month for asthma-related medical services, which was more than double the monthly asthma-related medical cost of $57 for the fluticasone propionate-salmeterol cohort (P < 0.05, Table 3, and Supplementary Table 2B for full model results). Adding monthly pharmacy costs further drove the differences between the cohorts, with the ICS + montelukast patients incurring $316 per month versus $165 per month for fluticasone propionate-salmeterol patients, resulting in a difference of more than $150 per month (see Supplementary Table 2A for full model results).

Table 3.

Adjusted average asthma-related monthly costs

| Outcome, mean (95% CI) | Fluticasone propionate-salmeterol (n = 747) | ICS + montelukast (n = 747) | Difference (CI difference)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | $165 ($61, $467) | $316 ($129, $814) | $151 ($67, $346) |

| Medical | $57 ($1, $1232) | $121 ($4, $1980) | $64 ($3, $748) |

Notes:

P < 0.05 based on a gamma-distributed generalized linear model with a log-link function controlling for patient age, Charlson comorbidity index, geographic location, gender, presence of allergic rhinitis, number of canisters of inhaled short-acting beta-agonists, oral corticosteroid prescription count, ICS prescription count, and number of hospitalizations/ED visits.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid.

Discussion

This is the first head-to-head study to assess asthma-related health care utilization and costs in asthmatic children aged 4–11 years receiving fluticasone propionate-salmeterol versus ICS + montelukast. The results indicated that patients starting treatment with fluticasone propionate-salmeterol had a significantly lower risk of experiencing an asthma-related hospitalization or hospitalization/emergency department visit compared with ICS + montelukast. This reduction in risk translated into a significant reduction in cost, with monthly cost savings averaging more than $150 per asthma-treated patient.

The findings are consistent with previous randomized clinical trials conducted in the adult population that show fluticasone propionate-salmeterol to be less costly and more effective than the combination of fluticasone propionate plus montelukast in terms of effects on pulmonary function, asthma symptoms, supplemental use of short-acting beta agonists, and frequency of exacerbations.15,16 Results from this analysis are also consistent with prior observational studies. Two studies using health insurance claims data found that in patients receiving ICS monotherapy, add-on therapy with salmeterol from a separate inhaler was associated with better outcomes and reduced health care costs compared with add-on therapy with a leukotriene modifier.13,14 Delea et al18 reported similar findings in patients with asthma receiving ICS monotherapy who were either switched to fluticasone propionate plus salmeterol from a single inhaler or initiated add-on therapy with salmeterol from a separate inhaler or montelukast. The present study expands on these earlier findings by comparing asthma-related health care utilization and costs specifically in children with asthma, with concordant results.

As with all observational studies, the interpretation of the findings presented here is bound by several limitations. First, due to the retrospective, nonrandomized nature of the study, it is possible that differences between cohorts in utilization and costs were due to other known and unknown confounding factors (eg, selection bias or residual confounding). To minimize the influence of selection bias, the two cohorts were matched on proxy asthma severity measures, such as presence of oral corticosteroid use, presence of ICS use, and occurrence of respiratory-related hospitalizations/emergency department visit. Furthermore, all the analyses were adjusted for variations in patient age, Charlson comorbidity index, geographic location, gender, presence of allergic rhinitis, number of canisters of inhaled short-acting beta agonists, corticosteroid prescription count, ICS prescription count, and number of hospitalizations/emergency department visits for respiratory-related conditions. Even after minimizing selection bias, the possibility of residual confounding must be recognized. However, the relative similarity of the cohorts in terms of measured baseline characteristics and the consistency of our findings with those of prior controlled trials and observational studies make such confounding less likely. Second, the proportion of patients deemed to be taking asthma-related controller or rescue medications was based on medication dispensed rather than medication used. Third, diseases tend to be undercoded in administrative claims databases; thus, asthma-related medical costs may have been underestimated, because costs were computed using medical claims with a primary ICD-9-CM code of asthma. However, the underestimation of costs should be random and equal across both cohorts, and therefore would not affect the difference or cost-savings seen with fluticasone propionate-salmeterol. Fourth, patient adherence to therapy was not evaluated, which could affect asthma-related pharmacy costs. Another limitation, associated with administrative claims data, is that clinical outcomes were measured only through emergency department visits or inpatient hospitalization, rather than other commonly used endpoints in clinical trials, such as number of asthma control days. The next limitation is related to the fact that results of this analysis should not be extrapolated beyond one year, because no patients within this analysis were evaluated for longer than that. Finally, the data for analysis in this study were obtained from a managed care database and may not be generalizable to other populations (eg, patients receiving care through publicly funded sources).

Despite these limitations, our study suggests that use of fluticasone propionate-salmeterol may provide some benefit for children with asthma. These results should be evaluated in conjunction with appropriate US Food and Drug Administration labeling, including the black box warning for fluticasone propionate-salmeterol. Future research should continue to validate these potential differences between the two therapies in various pediatric settings using additional data sources.

Conclusion

This pediatric outcomes study utilizing pharmacy and medical claims shows that fluticasone propionate-salmeterol was associated with lower utilization of asthma-related health care services and costs compared with ICS + montelukast. These findings, combined with results from randomized controlled trials and prior observational studies, suggest that fluticasone propionate-salmeterol should be considered in children with persistent asthma. Physicians may want to consider differences observed in clinical practice, overall risk benefit, and cost of treatment when making decisions regarding asthma management.

Supplementary tables

Table S1A.

Results of Cox proportional hazards model: time to asthma-related hospitalization

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluticasone-salmeterol (1 = yes) | 0.039 | 0.004 | 0.428 | 0.0080 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.159 | 0.826 | 1.625 | 0.3939 |

| Male (1 = yes) | 0.479 | 0.119 | 1.930 | 0.3003 |

| Midwest region* (1 = yes) | 4.703 | 0.502 | 44.096 | 0.1752 |

| South region* (1 = yes) | 6.467 | 0.391 | 106.867 | 0.1921 |

| Charlson index in pre-index period (continuous) | 1.672 | 1.149 | 2.432 | 0.0072 |

| Presence of allergic rhinitis (1 = yes) | 1.312 | 0.329 | 5.236 | 0.7002 |

| Number of SABA canisters (continuous) | 1.540 | 1.029 | 2.305 | 0.0358 |

| Number of OCS prescriptions (continuous) | 1.026 | 0.644 | 1.632 | 0.9153 |

| Number of ICS canisters (continuous) | 0.964 | 0.543 | 1.710 | 0.8999 |

| Number of hospital/ED visits for respiratory-related conditions (continuous) | 1.640 | 1.001 | 2.687 | 0.0497 |

Note:

Reference group, East region.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting beta agonist; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazards ratio.

Table S1B.

Results of Cox proportional hazards model: time to asthma-related hospitalization/emergency department visit

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluticasone/salmeterol (1 = yes) | 0.441 | 0.225 | 0.864 | 0.0169 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.050 | 0.906 | 1.216 | 0.5170 |

| Male (1 = yes) | 0.707 | 0.404 | 1.237 | 0.2248 |

| Midwest region* (1 = yes) | 1.321 | 0.633 | 2.755 | 0.4580 |

| South region* (1 = yes) | 1.752 | 0.647 | 4.743 | 0.2700 |

| Charlson index in pre-index period (continuous) | 1.294 | 0.970 | 1.725 | 0.0792 |

| Presence of allergic rhinitis (1 = yes) | 1.104 | 0.622 | 1.962 | 0.7346 |

| Number of SABA canisters (continuous) | 1.210 | 1.016 | 1.440 | 0.0324 |

| Number of OCS prescriptions (continuous) | 0.957 | 0.756 | 1.212 | 0.7150 |

| Number of ICS canisters (continuous) | 0.884 | 0.671 | 1.164 | 0.3796 |

| Number of hospital/ED visits for respiratory-related conditions (continuous) | 1.792 | 1.421 | 2.259 | <0.0001 |

Note:

Reference group, East region.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting beta agonist; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazards ratio.

Table S2A.

Results of cost model: asthma-related total costs

| Variable | Parameter estimate | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluticasone-salmeterol (1 = yes) | −0.6474 | −0.7401 | −0.5546 | <0.0001 |

| Age (continuous) | 0.0118 | −0.0099 | 0.0335 | 0.2864 |

| Male (1 = yes) | −0.0392 | −0.1213 | 0.0429 | 0.3489 |

| Midwest region* (1 = yes) | 0.0815 | −0.0132 | 0.1761 | 0.0917 |

| South region* (1 = yes) | −0.07 | −0.2107 | 0.0707 | 0.3295 |

| Charlson index in pre-index period (continuous) | 0.1703 | 0.1238 | 0.2169 | <0.0001 |

| Presence of allergic rhinitis (1 = yes) | 0.0798 | −0.001 | 0.1606 | 0.0528 |

| Number of SABA canisters (continuous) | 0.0278 | −0.0104 | 0.066 | 0.1544 |

| Number of OCS prescriptions (continuous) | 0.0287 | −0.0189 | 0.0763 | 0.2377 |

| Number of ICS canisters (continuous) | 0.0013 | −0.0406 | 0.0432 | 0.9525 |

| Number of hospital/ED visits for respiratory-related conditions (continuous) | 0.2097 | 0.1414 | 0.2779 | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory-related medical costs (natural log) | 0.0519 | 0.0311 | 0.0728 | <0.0001 |

| Asthma-related pharmacy costs (natural log) | 0.0027 | −0.0203 | 0.0257 | 0.8185 |

Note:

Reference group, East region.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting beta agonist; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazards ratio.

Table S2B.

Results of cost model: asthma-related medical costs

| Variable | Parameter estimate | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluticasone-salmeterol (1 = yes) | −0.6675 | −0.8566 | −0.4783 | <0.0001 |

| Age (continuous) | 0.0622 | 0.0170 | 0.1075 | 0.0071 |

| Male (1 = yes) | −0.2849 | −0.4582 | −0.1117 | 0.0013 |

| Midwest region* (1 = yes) | 0.0881 | −0.1113 | 0.2875 | 0.3864 |

| South region* (1 = yes) | 0.0970 | −0.2215 | 0.4155 | 0.5505 |

| Charlson index in pre-index period (continuous) | 0.3038 | 0.2104 | 0.3972 | <0.0001 |

| Presence of allergic rhinitis (1 = yes) | 0.0609 | −0.1100 | 0.2319 | 0.4849 |

| Number of SABA canisters (continuous) | 0.0306 | −0.0624 | 0.1235 | 0.5192 |

| Number of OCS prescriptions (continuous) | −0.0079 | −0.1073 | 0.0916 | 0.8767 |

| Number of ICS canisters (continuous) | 0.0041 | −0.1002 | 0.1083 | 0.9388 |

| Number of hospital/ED visits for respiratory-related conditions (continuous) | 0.4177 | 0.2786 | 0.5568 | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory-related medical costs (natural log) | 0.1075 | 0.0632 | 0.1518 | <0.0001 |

| Asthma-related pharmacy costs (natural log) | 0.0091 | −0.0412 | 0.0594 | 0.7227 |

Note:

Reference group, East region.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting beta agonist; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazards ratio.

Footnotes

Disclosure

This work was supported and funded by GlaxoSmithKline. RS is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline and owns company stock. AD and MS are employees of Xcenda, which has received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline.

References

- 1.American Lung Association. Asthma and children fact sheet. [Accessed May 6, 2012]. Available from: http://www.lung.org/lung-disease/asthma/resources/facts-and-figures/asthma-children-fact-sheet.html.

- 2.American Academy of Allergy Asthma Immunology. Asthma statistics. [Accessed May 6, 2012]. Available from: http://www.aaaai.org/media/statistics/asthma-statistics.asp.

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Aug, 2007. NIH Publication 07-4051. Originally printed Jul 1997. Revised Jun 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Weel C, Bateman ED, Bousquet J, et al. Asthma management pocket reference 2008. Allergy. 2008;63:997–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guevara JP, Ducharme FM, Keren R, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids versus sodium cromoglycate in children and adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2:CD003558. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003558.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bollinger ME, Smith SW, LoCaSale R, Baisedell C. Transition to managed care impacts healthcare service utilization by children insured by Medicaid. J Asthma. 2007;44:717–722. doi: 10.1080/02770900701595584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips C, McDonald T. Trends in medication use for asthma among children. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:232–237. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3282fe9d2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith MJ, Pawar Vl. Medical services and prescription use for asthma and factors that predict inhaled corticosteroid use among African-American children covered by Medicaid. J Asthma. 2007;44:357–363. doi: 10.1080/02770900701344355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ram F, Cates C, Ducharme F. Long-acting beta-2 agonists versus anti-leukotrienes as add-on therapy to inhaled corticosteroids for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;1:CD003137. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003137.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fish JE, Israel E, Murray JJ, et al. Salmeterol powder provides significantly better benefit than montelukast in asthmatic patients receiving concomitant inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Chest. 2001;120:423–430. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busse W, Nelson H, Wolfe J, et al. Comparison of inhaled salmeterol and oral zafirlukast in patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:1075–1080. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemanske RF, Mauger DT, Sorkness CA, et al. Step-up therapy for children with uncontrolled asthma receiving inhaled corticosteroids. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:975–985. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Connor RD, O’Donnell JC, Pinto LA, et al. Two-year retrospective economic evaluation of three dual controller therapies used in the treatment of asthma. Chest. 2002;121:1028–1035. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.4.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stempel DA, Pinto L, Standford RH. The risk of hospitalization in patients with asthma switched from an inhaled corticosteroid to a leukotriene receptor antagonist. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:39–41. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.125263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson HS, Busse WW, Kerwin E, et al. Fluticasone propionate/salmeterol combination provides more effective asthma control than low-dose inhaled corticosteroid plus montelukast. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:1088–1095. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.110920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pieters WR, Wilson KK, Smith HC, Tamminga JJ, Sondhi S. Salmeterol/fluticasone propionate versus fluticasone propionate plus montelukast: a cost-effective comparison for asthma. Treat Respir Med. 2005;4:129–138. doi: 10.2165/00151829-200504020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pavord I, Woodcock A, Parker D, Rice L SOLTA Study Group. Salmeterol plus fluticasone propionate versus fluticasone propionate plus montelukast: a randomized controlled trial investigating the effects on airway inflammation in asthma. Respir Res. 2007;8:67. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delea TE, Hagiwara M, Stanford RH, Stempel DA. Effects of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol combination on asthma-related health care resource utilization and costs and adherence in children and adults with asthma. Clin Ther. 2008;30:560–571. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9 CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9 CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1A.

Results of Cox proportional hazards model: time to asthma-related hospitalization

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluticasone-salmeterol (1 = yes) | 0.039 | 0.004 | 0.428 | 0.0080 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.159 | 0.826 | 1.625 | 0.3939 |

| Male (1 = yes) | 0.479 | 0.119 | 1.930 | 0.3003 |

| Midwest region* (1 = yes) | 4.703 | 0.502 | 44.096 | 0.1752 |

| South region* (1 = yes) | 6.467 | 0.391 | 106.867 | 0.1921 |

| Charlson index in pre-index period (continuous) | 1.672 | 1.149 | 2.432 | 0.0072 |

| Presence of allergic rhinitis (1 = yes) | 1.312 | 0.329 | 5.236 | 0.7002 |

| Number of SABA canisters (continuous) | 1.540 | 1.029 | 2.305 | 0.0358 |

| Number of OCS prescriptions (continuous) | 1.026 | 0.644 | 1.632 | 0.9153 |

| Number of ICS canisters (continuous) | 0.964 | 0.543 | 1.710 | 0.8999 |

| Number of hospital/ED visits for respiratory-related conditions (continuous) | 1.640 | 1.001 | 2.687 | 0.0497 |

Note:

Reference group, East region.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting beta agonist; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazards ratio.

Table S1B.

Results of Cox proportional hazards model: time to asthma-related hospitalization/emergency department visit

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluticasone/salmeterol (1 = yes) | 0.441 | 0.225 | 0.864 | 0.0169 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.050 | 0.906 | 1.216 | 0.5170 |

| Male (1 = yes) | 0.707 | 0.404 | 1.237 | 0.2248 |

| Midwest region* (1 = yes) | 1.321 | 0.633 | 2.755 | 0.4580 |

| South region* (1 = yes) | 1.752 | 0.647 | 4.743 | 0.2700 |

| Charlson index in pre-index period (continuous) | 1.294 | 0.970 | 1.725 | 0.0792 |

| Presence of allergic rhinitis (1 = yes) | 1.104 | 0.622 | 1.962 | 0.7346 |

| Number of SABA canisters (continuous) | 1.210 | 1.016 | 1.440 | 0.0324 |

| Number of OCS prescriptions (continuous) | 0.957 | 0.756 | 1.212 | 0.7150 |

| Number of ICS canisters (continuous) | 0.884 | 0.671 | 1.164 | 0.3796 |

| Number of hospital/ED visits for respiratory-related conditions (continuous) | 1.792 | 1.421 | 2.259 | <0.0001 |

Note:

Reference group, East region.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting beta agonist; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazards ratio.

Table S2A.

Results of cost model: asthma-related total costs

| Variable | Parameter estimate | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluticasone-salmeterol (1 = yes) | −0.6474 | −0.7401 | −0.5546 | <0.0001 |

| Age (continuous) | 0.0118 | −0.0099 | 0.0335 | 0.2864 |

| Male (1 = yes) | −0.0392 | −0.1213 | 0.0429 | 0.3489 |

| Midwest region* (1 = yes) | 0.0815 | −0.0132 | 0.1761 | 0.0917 |

| South region* (1 = yes) | −0.07 | −0.2107 | 0.0707 | 0.3295 |

| Charlson index in pre-index period (continuous) | 0.1703 | 0.1238 | 0.2169 | <0.0001 |

| Presence of allergic rhinitis (1 = yes) | 0.0798 | −0.001 | 0.1606 | 0.0528 |

| Number of SABA canisters (continuous) | 0.0278 | −0.0104 | 0.066 | 0.1544 |

| Number of OCS prescriptions (continuous) | 0.0287 | −0.0189 | 0.0763 | 0.2377 |

| Number of ICS canisters (continuous) | 0.0013 | −0.0406 | 0.0432 | 0.9525 |

| Number of hospital/ED visits for respiratory-related conditions (continuous) | 0.2097 | 0.1414 | 0.2779 | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory-related medical costs (natural log) | 0.0519 | 0.0311 | 0.0728 | <0.0001 |

| Asthma-related pharmacy costs (natural log) | 0.0027 | −0.0203 | 0.0257 | 0.8185 |

Note:

Reference group, East region.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting beta agonist; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazards ratio.

Table S2B.

Results of cost model: asthma-related medical costs

| Variable | Parameter estimate | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluticasone-salmeterol (1 = yes) | −0.6675 | −0.8566 | −0.4783 | <0.0001 |

| Age (continuous) | 0.0622 | 0.0170 | 0.1075 | 0.0071 |

| Male (1 = yes) | −0.2849 | −0.4582 | −0.1117 | 0.0013 |

| Midwest region* (1 = yes) | 0.0881 | −0.1113 | 0.2875 | 0.3864 |

| South region* (1 = yes) | 0.0970 | −0.2215 | 0.4155 | 0.5505 |

| Charlson index in pre-index period (continuous) | 0.3038 | 0.2104 | 0.3972 | <0.0001 |

| Presence of allergic rhinitis (1 = yes) | 0.0609 | −0.1100 | 0.2319 | 0.4849 |

| Number of SABA canisters (continuous) | 0.0306 | −0.0624 | 0.1235 | 0.5192 |

| Number of OCS prescriptions (continuous) | −0.0079 | −0.1073 | 0.0916 | 0.8767 |

| Number of ICS canisters (continuous) | 0.0041 | −0.1002 | 0.1083 | 0.9388 |

| Number of hospital/ED visits for respiratory-related conditions (continuous) | 0.4177 | 0.2786 | 0.5568 | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory-related medical costs (natural log) | 0.1075 | 0.0632 | 0.1518 | <0.0001 |

| Asthma-related pharmacy costs (natural log) | 0.0091 | −0.0412 | 0.0594 | 0.7227 |

Note:

Reference group, East region.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting beta agonist; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazards ratio.