Abstract

Reassortant influenza viruses with combinations of avian, human, and/or swine genomic segments have been detected frequently in pigs. As a consequence, pigs have been accused of being a “mixing vessel” for influenza viruses. This implies that pig cells support transcription and replication of avian influenza viruses, in contrast to human cells, in which most avian influenza virus polymerases display limited activity. Although influenza virus polymerase activity has been studied in human and avian cells for many years by use of a minigenome assay, similar investigations in pig cells have not been reported. We developed the first minigenome assay for pig cells and compared the activities of polymerases of avian or human influenza virus origin in pig, human, and avian cells. We also investigated in pig cells the consequences of some known mammalian host range determinants that enhance influenza virus polymerase activity in human cells, such as PB2 mutations E627K, D701N, G590S/Q591R, and T271A. The two typical avian influenza virus polymerases used in this study were poorly active in pig cells, similar to what is seen in human cells, and mutations that adapt the avian influenza virus polymerase for human cells also increased activity in pig cells. In contrast, a different pattern was observed in avian cells. Finally, highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 polymerase activity was tested because this subtype has been reported to replicate only poorly in pigs. H5N1 polymerase was active in swine cells, suggesting that other barriers restrict these viruses from becoming endemic in pigs.

INTRODUCTION

The reservoir of influenza A virus is aquatic birds (1–3), in which infection is typically asymptomatic. Influenza A virus is also established in domestic birds and several mammalian species, including humans, pigs, and horses. Influenza viruses usually show a restricted host range, with poor or no replication in species that are not the natural host. However, transmission of influenza viruses from one species to another can occur, particularly if the virus is mutated in host determining genes. This may result in an influenza pandemic and the establishment of a new lineage (4). The causative agents of the 1957 (H2N2) and 1968 (H3N2) human pandemics were reassortant viruses containing gene segments from a human circulating strain combined with segments from avian viruses (5, 6), and it has been suggested, although there is no direct evidence to support the suggestion, that the reassortment events occurred in pigs (7).

Close interactions between humans, poultry, ducks, and pigs in farms or markets offer opportunities for interspecies influenza virus transmission. Swine influenza virus lineages often originated from avian or human influenza viruses (reviewed in references 8 and 9), implying that pigs are susceptible to infection with both types of influenza viruses. Indeed, Kida et al. showed that 33 of 38 avian influenza virus strains (including representatives of subtypes H1 to H13) used in their study replicated in pigs (10). In contrast, human volunteers were largely refractory to infection with a panel of avian influenza viruses (11). In addition, genetic reassortment among avian, human, and/or swine influenza virus genes has occurred frequently in pigs (8, 12–15). Finally, there have been several reports and evidence of influenza virus transmission from pigs to humans worldwide (9, 16–19), and the genome segments of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 (pH1N1) strain were all previously found in swine influenza viruses (20–22). As a consequence, pigs have for many years been “accused” of acting as intermediate hosts for the mammalian adaptation of avian influenza viruses or the generation of new reassortants between avian and human influenza virus strains that can cause pandemics (10, 14, 16, 23–28).

The molecular basis for influenza virus host range restriction and adaptation to a new species is not fully understood. The preference of the viral glycoprotein hemagglutinin (HA) for differently linked sialic acid receptors (NeuAcα2,3Gal or NeuAcα2,6Gal) is the first main barrier that prevents frequent species jumps. The apparent susceptibility of pigs to both avian and human influenza virus infections may be explained by the presence of receptors for both types of viruses in the upper respiratory tract of pigs (23). However, more recent publications have challenged that notion (29–31). Another major host range restriction is exerted in the nucleus of the infected cell, where the viral ribonucleoproteins (vRNPs) must interact with cellular cofactors in order to replicate and transcribe the viral genome (reviewed in reference 32). Influenza vRNPs are composed of a viral genomic RNA segment coated with nucleoprotein (NP) molecules complexed with the influenza virus polymerase complex (PB1, PB2, and PA). A vRNP constitutes the minimal set of molecules necessary for viral replication and transcription (33). Most avian-origin influenza virus polymerases are poorly active in human or primate cells (34–41), but their activity in pig cells has never been studied in detail so far.

The polymerase subunit PB2 is known to be important for human adaptation of avian influenza virus polymerase, and amino acid 627 is a key residue in host range restriction, viral replication, and pathogenicity of avian influenza virus in mice, guinea pigs, ferrets, or humans (32, 40, 42–53). Avian influenza viruses usually have a glutamic acid (E) residue at this position, whereas human viruses generally have a lysine (K). A notable exception is the 2009 pandemic H1N1 (pH1N1) virus, which harbors an E. Interestingly, the majority of swine influenza viruses that originate from an avian source retain the avian signature 627E; for example, residue 627E has been maintained in the predominant H1N1 Eurasian swine lineage, which originated from birds in 1979 (54, 55). This is in contrast to observations in mice, where the E627K adaptation arises very quickly, often after a single passage, when animals are infected with an avian- or equine-origin influenza virus (32, 51, 56–60). Similarly, multiple human isolates of H5N1 viruses acquired a lysine at position 627 (61–63), and an H7N7 virus associated with a fatal human infection also displayed the same adaptive mutation (44, 64). Other host-specific residues are present in PB2. The enhancing effect of the PB2 D701N mutation on polymerase function was attributed to a stronger interaction and a change in specificity for human α importins (65–67). 701N can compensate for the absence of 627K and restore transmissibility between guinea pigs (52), expand the host range of avian H5N1 virus to mice and humans (58, 61), and contribute to the efficient transmission of a duck-origin H5N1 strain in guinea pigs (68).

As previously mentioned, the 2009 pH1N1 virus does not harbor a K at position 627 of PB2 but has the avian signature E residue. It was demonstrated that PB2 residues 590S and 591R of pH1N1 can partially compensate for the lack of 627K (69). Interestingly, these two mutations, known as the SR polymorphism, appeared in North American pigs in 1998, with the establishment of a lineage of viruses that contain a unique internal gene constellation known as the triple-reassortant internal gene (TRIG) cassette (69–71). A third hallmark PB2 mutation also present in the TRIG cassette in swine influenza viruses and in pH1N1 viruses is at PB2 position 271. While a threonine is usually located at this position in avian influenza viruses, an alanine is found in human viruses (72–75). It was demonstrated that the T271A mutation enhances the function of an avian-origin influenza virus polymerase in human cells but not in avian cells, increases virus growth in human cells, and is responsible in part for the high polymerase activity of the pH1N1 polymerase (34). A recent publication from Liu et al. showed that the small effect of back mutation of 590S/591R or 271A on its own in a virus with a PB2 from the TRIG cassette was insufficient to attenuate viral replication in mammalian cells but that triple mutation to the avian consensus resulted in significant attenuation (76).

Despite the widespread geographical distribution of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 virus in Asia, Africa, and parts of Europe, reports describing natural infection of pigs with HPAI H5N1 viruses have been limited (77–80). Indeed, during the peak of the HPAI H5N1 outbreak in Vietnam in 2004, only 0.25% of pigs were seropositive for HPAI H5N1 (77), and no seropositive pigs were detected during an H5N1 poultry outbreak in 2003 in Korea (81). In contrast to mouse and ferret animal models, where HPAI H5N1 virus replicates extensively and often leads to systemic infection and high pathogenicity (47, 82–84), the outcome of experimental infection of pigs or miniature pigs was limited to disease signs, accompanied by only modest viral titers and no transmission to contact animals (77, 85, 86). It is not known why the outcome of HPAI H5N1 virus infection in pigs is different from that in other mammals or why HPAI H5N1 virus replication in pigs is so limited.

The plasmid-driven minigenome assay (or minireplicon assay) is a powerful cell-based assay to study influenza virus polymerase. It relies on expression from plasmids of polymerase subunits PB1, PB2, and PA, NP, and a virus-like minigenome RNA molecule of negative polarity containing a reporter gene (for example, a luciferase, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase [CAT], or green fluorescent protein [GFP] gene), mimicking a viral genomic segment. Expression of the reporter gene is an indirect measure of the activity of the reconstituted influenza virus polymerase. The virus-like minigenome is transcribed from the reporter plasmid by the cellular RNA polymerase I (Pol I), whose promoter sequence is species specific. Influenza virus polymerase has been studied intensively by use of this system and human cells since the late 1990s, and in 2005, an avian system was developed (87). Canine (88) and mouse (89) RNA Pol I promoters have also been cloned and used to establish reverse-genetic systems for recovery of recombinant influenza viruses or to study influenza virus polymerase activity in corresponding cell types.

Here we developed a minigenome assay to investigate influenza virus polymerase activity in pig cells and used the new assay to compare the activities of viral polymerase complexes cloned from viruses isolated from different hosts. Surprisingly, and in contrast to the proposed susceptibility of pigs to avian influenza viruses, we found that, as in human cells, polymerase complexes from typical avian influenza viruses directed a level of replication much lower than those from mammal-adapted strains in pig cells. PB2 mutations that enhanced avian-origin influenza virus polymerase function in human cells also increased activity in pig cells but not in avian cells. Finally, HPAI H5N1 polymerase was highly active in the two different pig cell lines used, suggesting that other barriers restrict replication of these viruses in pigs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs.

Swine and mouse genomic DNAs were extracted from NSK and NIH 3T3 cells, respectively, by use of a Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega). Based on a previous report (90), the mouse RNA polymerase I terminator sequence was first amplified using primers mouseters1 (CCCTGCTTTTGCTCCCCCCCAACTTCGGAGG) and mousetermrev1 (GGTCGACCTAAAGGTTCCAGG). The purified PCR product was then amplified with primer NSmouseterms1 (TTATTATATTGAATTCTATGACTTTGTCACCCTGCTTTTGCTCCCC), which amplifies the influenza A virus segment 8 3′-noncoding sequence, and primer mousetermrev2 (ATTTTATTTTGGATCCATCGATTAAGGTCGACCTAAAGGTTCCAG) and cloned between EcoRI and BamHI sites of pHuman-PolI-Firefly (39) to generate pHPOM1-Firefly. The three regions of the swine RNA polymerase I promoter sequence were amplified from genomic DNA by using the forward primers PigPolIfw1 (CTGGGCCTGAGGCGTGC) (fragment from positions −472 to +1), PigPolIfw2 (GGAGTGTTTCCCTGTCGGTCG) (fragment from positions −387 to +1), and PigPolIfw3 (GGGTCGACCAGATGGCTCTG) (fragment from positions −173 to +1), together with the reverse primer PigPolIendrev1 (ATCTACCTGGTGACAGAAAAGGCG). Purified PCR products were then amplified with the XhoI-containing forward primers PigPolIfw1Xho (TTATTTATACTCGAGCTGGGCCTGAGGCGTGC), PigPolIfw2Xho (TTATTTATACTCGAGGGAGTGTTTCCCTGTCGGTCG), and PigPolIfw3Xho (TTATTTATACTCGAGGGTCGACCAGATGGCTCTG), respectively, together with the reverse primer PigPolIendNSr1 (ATATAAATAAAGCTTATTTAATGATAAAAAACACCCTTGTTTCTACTATCTACCTGGTGACAGAAAAGGCG), which amplifies the influenza A virus segment 8 5′-noncoding sequence and includes a HindIII restriction site. Digested PCR products were introduced into pHPMO1-Firefly between XhoI and HindIII sites, replacing the human RNA polymerase I promoter sequence and generating pSPOM1-Firefly, pSPOM2-Firefly, and pSPOM3-Firefly, respectively. The human polymerase I promoter sequence present in pHPOM1-Firefly was also replaced by the avian polymerase I promoter (87) from pCK-PolI-Firefly (39) to generate the avian virus-specific pCPOM1-Firefly PolI reporter plasmid. A/England/195/09 (Eng195), A/Duck/Bavaria/1/77 (Bav), A/Quail/Hong Kong/G1/97 (G1), A/Victoria/3/75 (Vic), and A/Turkey/Turkey/1/2005 (Ty05) PB1, PB2, PA, and NP genes were subcloned into the pCAGGS expression plasmid. Plasmids containing the PB1, PB2, PA, and NP genes from A/Duck/Bavaria/1/77 were provided by J. Stech (Friedrich Loeffler Institut, Greifswald-Insel Riems, Germany), those containing the genes from A/Quail/Hong Kong/G1/97 were supplied by M. Peiris (The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China), those containing the genes from A/Victoria/3/75 were provided by T. Zurcher (GlaxoSmithKline), and those containing the genes from A/Turkey/Turkey/1/2005 were supplied by R. Fouchier (Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Netherlands). PolI and pCAGGS plasmids for A/Turkey/England/50-92/91 (50-92) were described previously (39, 91), and PolI plasmids for A/England/195/09 PB1, PB2, PA, and NP gene segments were synthesized by GeneArt, based on the sequence of a prototypic pandemic 2009 virus as previously described (92). Mutagenesis of PB2 genes in pCAGGS was performed by overlapping PCR. 50-92 PB2 E627K, D701N, G590S-Q591R, and T271A mutants were introduced into a pCAGGS plasmid containing a C-terminal Flag-tagged sequence. All plasmid constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Antibodies.

Anti-Flag and anti-β-actin antibodies were obtained from Sigma (mouse monoclonal anti-Flag M2 F3165 and mouse anti-β-actin A228). The anti-influenza A virus M1 monoclonal antibody was purchased from AbD Serotec (mouse anti-influenza A virus matrix protein [MCA401]). Anti-vinculin antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (SC-7649).

Minigenome assays.

Cells were transfected in 12-well plates with plasmids encoding the PB1, PB2, PA, and NP proteins (320 ng of NP, 160 ng [each] of PB1 and PB2, and 40 ng of PA), together with a plasmid expressing negative-sense firefly luciferase flanked by segment 8 noncoding sequences under the control of a species-specific polymerase I promoter (160 ng) by use of the Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen). Twice the amount of DNA was transfected into DF-1 cells. Cells were incubated at 37°C. Twenty hours after transfection, cells were lysed with 300 μl of passive lysis buffer (Promega), and firefly luciferase activity was measured using a FLUOstar Omega plate reader (BMG Labtech).

Protein analysis.

To determine the effect of the adaptive mutations on PB2 expression, 293T, NPTr, and DF-1 cells were transfected in 6-well plates with 1 μg (293T and NPTr) or 2 μg (DF-1) of pCAGGS plasmid expressing 50-92 wild-type (WT) PB2 or the E627K, D701N, G590S-Q591R, or T271A mutant. At 20 h posttransfection, total cell lysates were prepared in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 1% Igepal, 25% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA), and PB2 proteins were detected by Western blotting using an antibody directed against the Flag tag.

Cultured cells.

Newborn pig trachea (NPTr), newborn swine kidney (NSK), human embryonic kidney (293T), chicken fibroblast (DF-1), and Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Biosera) and with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). The cell lines were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, except for DF-1 cells, which were maintained at 39°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Virus rescue.

Viruses were generated via reverse genetics using a 12-plasmid system as described previously (93, 94). The PR8/5092, PR8/5092 E627K, PR8/Bav, and PR8/Bav E627K viruses contained the HA, NA, M, and NS genes of A/PR/8/34 and the PB1, PA, NP, and WT or mutant PB2 genes from A/Turkey/England/50-92/91 or A/Duck/Bavaria/1/77. Briefly, all 12 plasmids were transfected into 293T cells in 12-well plates by use of Fugene 6 (Roche Diagnostics). After 24 h, the transfected cells were removed from the wells, mixed with MDCK cells, and cocultured in 25-ml flasks. The first 6 to 8 h of the coculture was carried out in 10% serum, after which the cells were washed briefly in serum-free medium and the medium was replaced with serum-free medium containing 2.5 μg/ml trypsin (Worthington). Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was carried out on the supernatants of the recovered viruses, and the amplified segment PB2 cDNAs were sequenced to confirm their genotype. Infectious titers were determined on MDCK cells.

Virus growth in vitro.

To determine the growth of recombinant viruses in vitro, NPTr cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.001 for 1 h and incubated at 37°C in DMEM containing 0.7 μg/ml of tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin (Lorne Labs). At the indicated times postinfection, supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C. Viral titers were determined on MDCK cells.

Protein production of recombinant viruses.

To determine the effect of PB2 E627K mutation on viral protein synthesis, NPTr cells were infected at an MOI of 3 and cultured at 37°C. At 7 and 10 h postinfection, total cell lysates were prepared in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 1% Igepal, 25% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA), and proteins were detected by Western blotting using influenza A virus M1 and actin antibodies.

Sequence analysis.

All swine, avian, human seasonal, and human pandemic complete viral genome sequences were downloaded. The avian, human seasonal, and human pandemic viral sequences were subsampled at 1 per subtype per county per year, since there were over 2,000 isolates in each of these categories; this resulted in a data set of 2,259 sequences. The segment 1 sequences were aligned using the custom Java code MUSCLE, checked manually, and trimmed to the coding frame. A neighbor-joining tree was estimated in MEGA 5.05, using the Tamura-Nei model, with gamma rates between sites, and major lineages were identified manually.

RESULTS

Generation of an influenza A virus minireplicon reporter construct driven by the swine RNA polymerase I promoter.

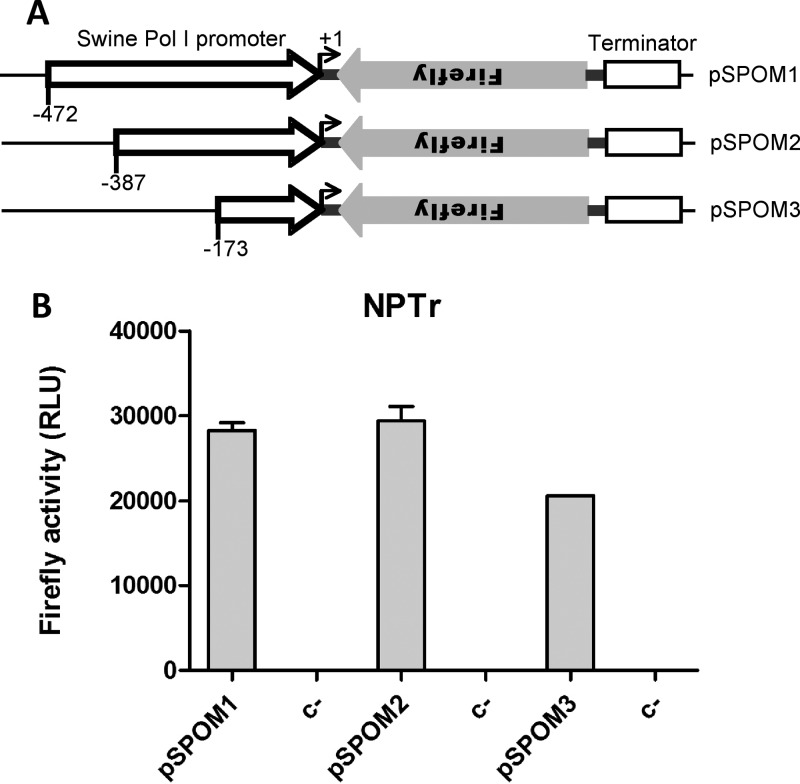

Because of the suggested role of pigs as a mixing vessel for influenza viruses and the apparent susceptibility of pigs to avian influenza, we were interested in studying influenza virus polymerase activity in pig cells. To this end, the promoter sequence recognized by the swine RNA polymerase I (95) was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA extracted from NSK cells (96) and introduced into a previously described minigenome reporter plasmid (39). Three different constructs with different 5′ boundaries were made. The mouse RNA polymerase I terminator sequence was cloned into the reporter constructs to optimize the minigenome RNA segment transcription termination (97). A diagram of the three constructs is presented in Fig. 1A.

Fig 1.

Generation of influenza virus polymerase assay for use with swine cells. (A) The swine RNA polymerase I promoter sequence was cloned into an influenza A virus minigenome reporter plasmid. Three different constructs with different 5′ boundaries were made (position −472, −387, or −173 to +1). The mouse RNA polymerase I terminator sequence is indicated by a white box. The dark gray boxes correspond to the influenza A virus NS segment noncoding sequences that flank the firefly luciferase open reading frame in reverse orientation (light gray). (B) NPTr cells were transfected with four plasmids, encoding PB1, PB2, PA, and NP proteins derived from influenza virus A/England/195/09 (Eng195), together with a plasmid that directs expression of the virus-like firefly luciferase reporter RNA minigenome under the control of the swine RNA polymerase I promoter (pSPOM1-Firefly, pSPOM2-Firefly, or pSPOM3-Firefly). Control cells were transfected with the reporter RNA minigenome alone (C−). At 20 h posttransfection, cells were lysed and firefly luciferase activity measured. Results are shown as raw data. Similar results were obtained with swine NSK cells (data not shown). RLU, relative light units.

NPTr cells (96) were cotransfected with plasmids expressing A/England/195/09 (Eng195) PB1, PB2, PA, and NP proteins together with the pSPOM1-Firefly, pSPOM2-Firefly, or pSPOM3-Firefly minigenome-expressing plasmid. Although Eng195 is a representative of the swine-origin pandemic 2009 H1N1 virus (pH1N1) isolated from a human patient, this virus, like many pH1N1 isolates, efficiently replicates in and transmits between pigs (98, 99), and swine infection with pH1N1 was coincident with the 2009 pandemic (100, 101). Therefore, the Eng195 polymerase was expected to support amplification and replication of the minigenome in pig cells. Firefly luciferase activities obtained 20 h after transfection are presented in Fig. 1B. The three constructs all gave a robust luminescent signal following vRNP reconstitution, and since raw data values are shown, it is clearly evident that almost no background was detected from the reporter plasmids alone. Similar results were obtained following transfection of the swine NSK cell line (data not shown). For the rest of the study, pSPOM2-Firefly was used.

Comparison of activities of a panel of influenza virus polymerases in pig, human, and avian cells.

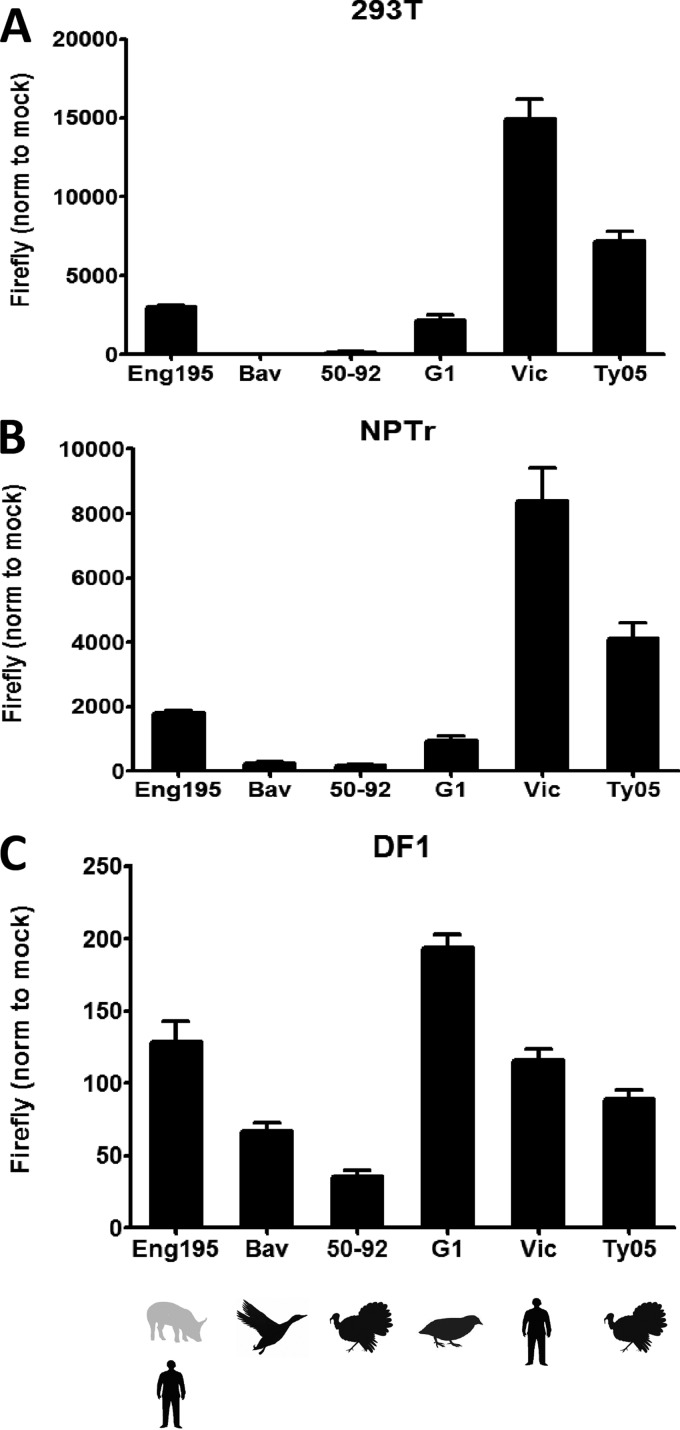

A polymerase assay was performed with pig, human, and avian cells, using a panel of influenza virus polymerases of different origins. A/Turkey/England/50-92/91 (50-92) (H5N1) and A/Duck/Bavaria/1/77 (Bav) (H1N1) are two typical avian influenza virus strains. We previously described 50-92 as a typical poultry-adapted avian influenza virus whose polymerase displays host range restriction in mammalian cells (35, 39, 91). A/Duck/Bavaria/1/77 is considered an ancestor of the avian-origin H1N1 virus that crossed into pigs in 1979 to generate the Eurasian avian-like swine H1N1 lineage (54, 102). A/Quail/Hong Kong/G1/97 (G1) is a less typical avian influenza virus that is representative of one of the prevalent avian H9N2 virus lineages circulating in southern China (103). Viruses from the G1 lineage have been responsible for two human infections, causing mild illness (104–106), but G1 H9N2 viruses have not been isolated from pigs. A/Turkey/Turkey/1/2005 (Ty05) is a Eurasian lineage HPAI H5N1 virus assigned to clade 2.2. It is the prototype isolate from an outbreak of H5N1 infection in Turkey in 2005 to 2006 in which there were eight confirmed human cases, including four fatalities (107). Finally, polymerases from two human strains were tested: a seasonal H3N2 strain frequently used in laboratory studies, i.e., A/Victoria/3/75 (Vic), and the already-mentioned pH1N1 virus Eng195. The capacities of this panel of influenza virus polymerases to replicate a minigenome in human 293T, swine NPTr, and avian DF-1 cells are presented in Fig. 2A, B, and C, respectively. The data have not been normalized, for example, to expression of a reporter gene such as the Renilla luciferase gene from a cotransfected plasmid, because this can skew results when polymerase genes from different viral sources are compared. In particular, we find that the endonuclease activities encoded by the PA and PA-X genes (108) differ in potency between viral strains (unpublished observations) and that these activities reduce the expression of reporter genes, as previously noted (109). It is also important that the transfection efficiencies of the three cell types used here differ greatly, explaining why the absolute values of firefly luciferase produced in different cells are markedly different. In particular, we and others have previously noted the low transfection efficiency of the DF-1 cell line (37, 39). Nonetheless, it is evident that the patterns of polymerase activity from different viral sources were very similar in human and pig cells but different in the avian cell line. In the two mammalian cell lines, the two typical avian virus strains, 50-92 and Bav, showed low polymerase activities, in contrast to the human-origin H3N2 Vic polymerase, which gave the strongest polymerase activity observed in both human and pig cells. G1 polymerase was more active than either Bav or 50-92 polymerase in human and pig cells, with an activity approaching that of Eng195. Expression of the firefly luciferase reporter gene by the polymerase derived from the HPAI H5N1 Ty05 virus was stronger than expression driven by the G1 or Eng195 polymerase in human or pig cells. In avian cells, the differences between the influenza virus polymerase activities were not dramatic, and the pattern was different. For example, the H9N2 G1 polymerase was the most active, followed by the Eng195 and Vic polymerases. The difference between the 50-92 and Vic polymerases was only 3.3-fold in avian DF-1 cells, whereas 50- and 98-fold differences were observed in swine NPTr cells and human 293T cells, respectively. Taken together, these data imply that a host range barrier at the level of polymerase activity for typical avian influenza viruses exists in pig cells, just as it does in human cells.

Fig 2.

Activities of a panel of avian and human influenza virus polymerases in human, swine, and avian cells. Plasmids encoding PB1, PB2, PA, and NP proteins derived from influenza viruses A/England/195/09 (Eng195), A/Duck/Bavaria/1/77 (Bav), A/Turkey/England/50-92/91 (50-92), A/Quail/Hong Kong/G1/97 (G1), A/Victoria/3/75 (Vic), and A/Turkey/Turkey/1/2005 (Ty05) were transfected into human 293T (A), swine NPTr (B), and avian DF-1 (C) cells, together with a species-specific firefly luciferase minigenome reporter plasmid. At 20 h posttransfection, cells were lysed and firefly luciferase activity measured. Data were normalized to those for cells transfected with reporter plasmid alone. Results shown are the averages with standard deviations for three independent experiments.

Known human-adaptive mutations also increase influenza virus polymerase activity in pig cells.

In order to gain some insights into the nature of the genetic changes that mediate efficient replication of a typical avian-origin influenza virus polymerase in swine, we first analyzed the polymorphisms at known host range-determining residues of the PB2 component of influenza virus polymerases that are endemic in different hosts, including pigs. The polymorphism frequencies in PB2 at positions 271, 590-591, 627, and 701 were estimated from a sample of complete genome sequences downloaded from the NCBI influenza virus resource (110). A total of 2,259 PB2 sequences were analyzed (see Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material for details). The amino acids at these positions in the strains used in the present study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

PB2 residues at positions 271, 590/591, 627, and 701 present in the different influenza strains used in this study

| Strain | PB2 residue(s) at indicated position(s) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 271 | 590/591 | 627 | 701 | |

| Eng195 | A | SR | E | D |

| BAV | T | GQ | E | D |

| 50-92 | T | GQ | E | D |

| G1 | T | SQ | E | D |

| Vic | S | GQ | K | D |

| Ty05 | T | GQ | K | D |

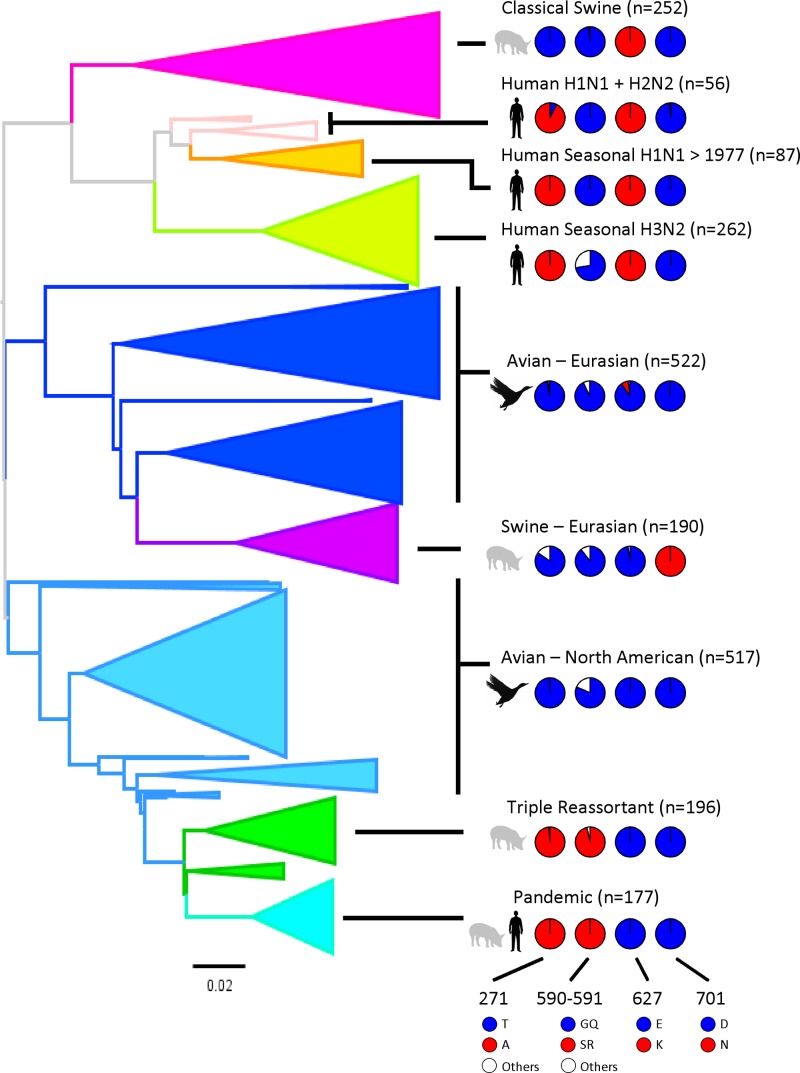

The most studied of these PB2 polymorphisms is undoubtedly the PB2 E627K mutation. The only swine lineage of influenza virus that contains PB2 627K is the classical swine lineage that was reintroduced in 1918 into pigs from humans rather than evolving naturally in pigs via an avian source (Fig. 3). In contrast, more than 30 years after introduction of the Eurasian avian-like H1N1 lineage from birds directly to pigs, the PB2 E627K mutation has not been naturally selected. Similarly, 627E is found in PB2 sequences from swine influenza viruses that have the TRIG cassette, in which PB2 and PA originated from a North American avian-origin virus 14 years ago (70, 71). This suggests that there is not a strong selection pressure for 627K to emerge in pigs, in contrast to other mammalian species. To test whether this was because 627K does not affect polymerase function in pig cells, the E627K mutation was engineered by site-directed mutagenesis in PB2 genes from the typical host-restricted avian virus polymerases, the Bav and 50-92 polymerases. Activities of polymerase complexes containing WT PB2 or PB2 with a mutation at position 627 were compared in human, swine, and avian cells (Fig. 4A, B, and C). To demonstrate that the host range mutations did not affect expression of the PB2 mutant proteins, the mutations were additionally engineered into an epitope-tagged 50-92 PB2 gene and expressed individually in each cell type. Western blot analysis using antibody to the C-terminal epitope tag (Flag tag) showed that none of the host range mutations affected the accumulation of PB2 protein in any of the cell types (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This result is in line with several other publications that also show that mutations that affect polymerase activity, such as those at PB2 position 627, do not alter the expression or accumulation of the protein (35, 37, 69, 111).

Fig 3.

Polymorphism frequencies at positions 271, 590-591, 627, and 701 in PB2, according to virus lineage. On the left is the neighbor-joining tree for PB2, with collapsed tips and branches colored by major lineage. A total of 2,259 PB2 sequences were analyzed (see Materials and Methods). Also shown are pie charts for each lineage, depicting the PB2 polymorphisms (across all hosts) at amino acids 271, 590-591, 627, and 701. The avian-like amino acids are colored blue, and the main alternative is colored red. Other amino acids are colored white. Details of the percentages of the different amino acids found at each PB2 site can be found in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

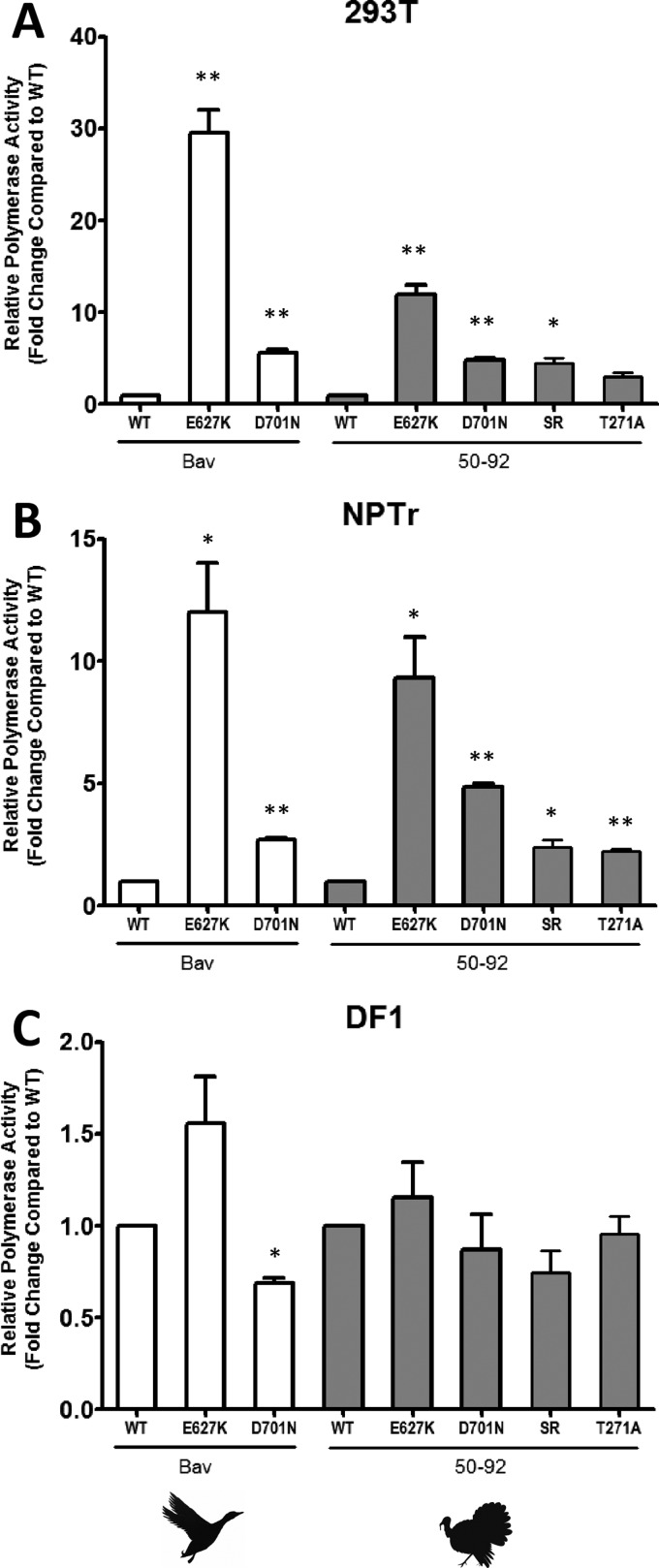

Fig 4.

Polymerase activities of Bav and 50-92 complexes containing PB2 mutants. Human 293T (A), swine NPTr (B), or avian DF-1 (C) cells were transfected with plasmids expressing A/Duck/Bavaria/1/77 (Bav) or A/Turkey/England/50-92/91 (50-92) NP, PB1, PA, and WT or mutant PB2, together with a species-specific firefly luciferase minigenome reporter plasmid. At 20 h posttransfection, cells were lysed and firefly luciferase activity was measured. Data were normalized to the activity of the WT polymerase. Results shown are the averages with standard deviations for three independent experiments. The statistical significance of the difference between each mutant and the respective wild-type polymerase was assessed by unpaired Student's t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

As previously reported (34, 35, 37–40), the introduction of 627K into avian-origin viral polymerases dramatically increased expression of the reporter gene in human cells (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, 627K also significantly increased avian virus polymerase activity in pig cells (P < 0.5 by unpaired Student's t test) (Fig. 4B). Compared to the respective WT polymerases, increases of about 12-fold and 10-fold were observed for Bav E627K and 50-92 E627K polymerases, respectively, meaning that they approached the level of activity of the Eng195 polymerase constellation in pig cells (Fig. 2B). The activity of the H9N2 G1 polymerase was also increased even further in pig cells (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) and human cells (data not shown) when the E627K mutation was introduced. Conversely, a reduction of activity in both cell types was observed when the human-adapted Vic PB2 or Ty05 PB2 was mutated (K627E) (see Fig. S2).

Similar to the E627K mutation, the D701N adaptive mutation has been reported to emerge when avian influenza viruses are passaged in animals such as mice (36, 41, 59, 112, 113). The D701N mutation in PB2 is associated with enhanced polymerase activity in human cells (35, 36, 113–115). During the natural evolution of influenza virus, this mutation has been selected in the Eurasian swine lineage only (Fig. 3). Indeed, 701N is present in the PB2 proteins of early isolates of the Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine viruses (for example, A/Swine/Germany/2/1981) but not in those from the supposed avian precursor, A/Duck/Bavaria/1/77. The effect of this mutation on the activity of two avian virus polymerases, the Bav and 50-92 polymerases, was tested in human and pig cells (Fig. 4A and B, respectively). In both cell types, D701N mutation resulted in increased polymerase activity, to a lesser extent than that with the E627K mutation, but the difference was still statistically significant (P < 0.01 by unpaired Student's t test) compared to the wild-type avian polymerase activities. Thus, in pig cells, the luciferase signal from Bav polymerase with the D701N mutation was 2.7-fold higher than that from WT Bav polymerase. The D701N mutation increased 50-92 polymerase activity 4.8-fold in pig cells. In avian cells, neither the E627K nor D701N mutation increased the polymerase activity of either of the avian viruses tested (Fig. 4C).

PB2 residues 627K and 701N are absent in swine triple-reassortant viruses and also in the descendant 2009 pH1N1 viruses (Fig. 3; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). However, the G590S/Q591R and T271A mutations present in the TRIG cassette-encoded PB2 protein can compensate for this absence (34, 69). These mutations might have been selected and maintained in pigs because they confer a specific replicative advantage in this species. The T271A mutation is also found in seasonal human viruses, in conjunction with the E627K switch, but it did not emerge in the classical swine lineage (Fig. 3). Sequences encoding the G590S/Q591R and T271A mutations were introduced individually into the 50-92 PB2 gene, and minigenome assays were performed to assess the consequences of these changes on polymerase activity in human, swine, and avian cells (Fig. 4A, B, and C). The results indicate that G590S/Q591R and T271A mutations individually increased the activity of avian-origin 50-92 polymerase in both human and swine cells (4.5- and 3-fold, respectively, in human cells and 2.4- and 2.2-fold, respectively, in pig cells). Polymerase activities in DF-1 cells were not significantly affected by these mutations, in agreement with previous publications (34, 69). Thus, the four PB2 mutations tested (E627K, D701N, G590S/Q591R, and T271A), which adapt avian influenza virus polymerase for human cells, also increased activity in pig cells but not in avian cells.

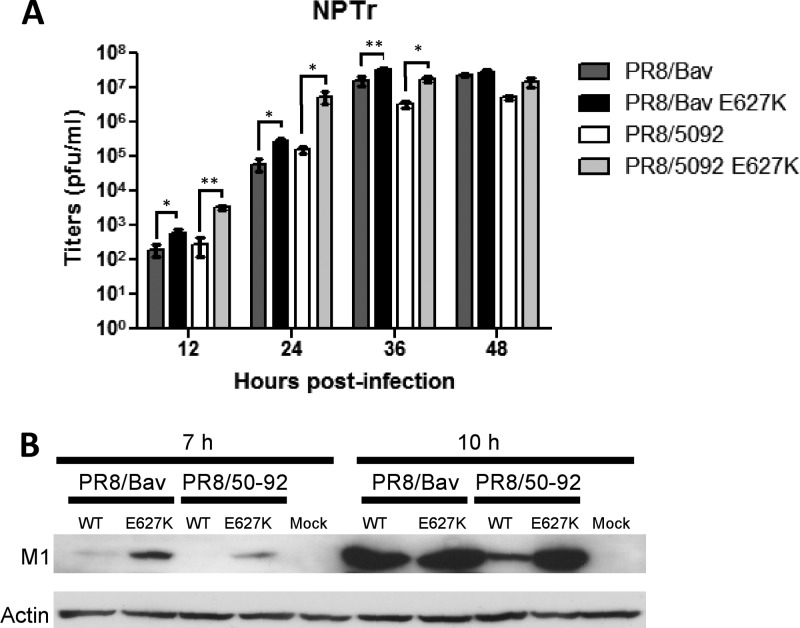

PB2 E627K enhances virus replication in pig cells.

To test that the results obtained with the in vitro polymerase assay reflected a difference of replication in the context of infectious virus, we generated a set of recombinant viruses by reverse genetics. Viruses that contained wild-type A/Turkey/England/50-92/91 or A/Duck/Bavaria/1/77 polymerase and NP genes or encoded the mammalian adaptive mutation E627K in PB2 were produced. To eliminate host restrictions that mapped to cell entry, interferon response, or vRNP export, we replaced the HA and NA surface protein genes and the NS and M genes of each virus with those from the vaccine strain PR8. PR8-based recombinant viruses have been used to experimentally infect minipigs (116). The multicycle replication of the viruses was compared in swine NPTr cells. Both PB2 E627K-containing viruses grew to higher titers than their wild-type counterparts; the differences in titer were statistically significant except at the last time point, i.e., 48 h postinfection (Fig. 5A). Moreover, Western blot analysis showed that viral gene expression, as exemplified by the M1 protein, was increased in the cells infected with PB2 E627K-expressing viruses over those infected by viruses with wholly avian polymerase constellations, and this was especially evident early during infection (Fig. 5B). These differences confirmed a growth advantage resulting from increased polymerase activity for PB2 E627K-containing viruses in vitro in swine cells, as has been seen in human or simian cells.

Fig 5.

Viral replication in pig cells. (A) Multistep growth of viruses in swine cells. NPTr cells were infected with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 0.001. Culture supernatants were harvested at the indicated times, and virus titers were determined on MDCK cells. Student's t test with the Bonferroni correction was performed to determine the P values (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (B) Viral protein synthesis in infected NPTr cells. Cells were infected with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 3 and then incubated at 37°C. Infected cells were harvested and lysed at the indicated time points and then analyzed by Western blotting using a monoclonal antibody against influenza A virus M1. Anti-actin antibody was used as a loading control. The data shown are results of two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Pigs are thought to play an important role in influenza virus transmission between birds and humans. They have been proposed to be an intermediate host for the adaptation of avian influenza viruses to humans and for the generation of reassortant viruses with pandemic potential (reviewed in reference 16). Pigs are naturally susceptible to infection with at least some avian influenza viruses, and avian-origin viruses have been isolated from pigs worldwide (reviewed in references 8 and 9). Thus, one might anticipate that pig cells would be more permissive to avian-origin influenza virus polymerase than human cells are. Moreover, it may be that pigs express cofactors for avian influenza virus polymerase that are not present or are different in other mammalian species, such as humans. Using an influenza virus polymerase assay, we investigated the ability of six influenza virus polymerase complexes from different species (turkey, duck, quail, and human) to amplify and express a reporter minigenome in swine cells. Surprisingly, our results indicated that pig and human cells have similar restrictions in supporting the function of influenza virus polymerases from different origins. Low activity was observed in pig cells for polymerases from the two classical avian strains A/Turkey/England/50-92/91 (50-92) and A/Duck/Bavaria/1/77 (Bav). Although pigs seem to support the growth of many typical avian influenza viruses, Kida et al. showed that not all strains replicated or induced a serological response in experimentally infected pigs. In addition, the large majority of avian viruses replicated to a lower level in pigs than a swine-adapted virus did (10). In the field, only a minority of avian influenza virus strains seem to naturally spread in the pig population. This suggests that avian influenza viruses with the potential to efficiently replicate and transmit in pigs are rare. Based on our polymerase assay, some candidates might be viruses from the H9N2 G1 lineage or the H5N1 Eurasian lineage Z genotype, such as Ty05 virus, that already bear the E627K mutation. H9N2 A/Quail/Hong Kong/G1/97 (G1) polymerase showed good activity in pig cells and also in human cells (Fig. 2). These results correlate with recent reports showing that H9N2 G1 virus replicates efficiently in human cells (117) and that a virus from the G1 lineage can replicate in 4-week-old pigs and in mice (118). In addition, H9N2 viruses from various genotypes can replicate in ferrets (119), and an H9N2 virus grew to a high titer in a porcine differentiated respiratory epithelial cell precision-cut lung slice system (120). Thus, we speculate that H9N2 G1 polymerase is already adapted to mammals. So far, isolation of H9N2 viruses from pigs has been infrequent, and no H9N2 transmission has been reported between swine and humans or between humans (121), but our results indicate that pigs might create a suitable environment for H9N2 viruses to acquire adaptive mammalian mutations and generate a mammal-transmissible strain. Continuous monitoring of the swine population for H9N2 viruses is essential.

Interestingly, HPAI H5N1 influenza A viruses that are lethal or extremely virulent in chickens and mammalian models, such as ferrets or mice, barely induce any symptoms in pigs. So far, HPAI H5N1 viruses have killed 363 humans worldwide, with a death rate of around 60% for WHO laboratory-confirmed infections (122). In contrast, HPAI H5N1 infections result in only mild to moderate infection in pigs (77, 85, 86, 123). Although HPAI H5N1 strains can replicate in pigs, this species is known to show a very low susceptibility to this subtype. We concluded from our study that the limited replication of HPAI H5N1 virus in pigs is not explained by a deficient polymerase activity. Differences in host immune responses and, in particular, an attenuated proinflammatory response in pig cells compared to human cells were recently described by Nelli et al. (124) and put forward as an explanation for the resistance of pigs to contemporary Eurasian HPAI H5N1 viruses (i.e., Ty05).

The well-known host range determinant PB2 E627K, which enhances influenza virus polymerase activity in human or mouse cells, also increased activity in pig cells. Introduction of residue 627K enhanced the activity of the Bav and 50-92 polymerases to a level similar to that shown by the Eng195 polymerase, an influenza virus polymerase capable of replication in pigs. Moreover, the E627K mutation occurred spontaneously when a restricted reassortant virus was used to infect pigs (125). It is not clear why most porcine influenza viruses derived directly from an avian source do not contain the 627K motif in PB2. Our previous work suggests that a host factor(s) strongly increases the influenza virus polymerase activity when there is a lysine at position 627 of PB2 in human cells (39). The results obtained in this study suggest that the same factor(s) is present in pig cells. Other mutations in PB2, such as D701N, 590S/591R, and T271A, increased influenza virus polymerase function in pig cells as they did in human cells, and these are the ones that have been selected in nature when avian-origin viruses have crossed into swine. The D701N mutation might have contributed to pig adaptation of the avian H1N1 virus strain that crossed into pigs in 1979, since introduction of 701N into A/Duck/Bavaria/1/77 PB2 resulted in an increase, albeit a modest one (2.7-fold), of polymerase activity in pig cells (Fig. 4B). The 590S/591R and T271A mutations have also appeared naturally in swine during the generation of the TRIG cassette. Both of these mutations enhanced the activity of avian virus polymerase in pig cells (Fig. 4B), in line with their role in replication and virulence of influenza viruses in mice (34, 76). The ability of these mutations to already adapt PB2 to pig cells might explain why engineering 627K into a swine virus with a TRIG cassette made little difference to replication in pigs, whereas back mutating the same residue (K627E mutation) in a classical swine influenza virus decreased replication in vivo (126). Here we showed that T271A and 590S/591R mutations acted individually to increase the activity of avian virus PB2 in mammalian cells. This conclusion is in line with the observation that starting from a TRIG-origin PB2, engineering away either mutation alone had little effect on virus replication or virulence in mice, whereas loss of both together resulted in attenuation (76).

The results of our polymerase assays of pig cells indicate that mutations (or reassortment) are required for efficient replication of avian influenza virus in pigs, as in humans. In fact, several reports recently challenged the notion that pigs readily replicate avian influenza viruses. In an experimental transmission study, avian influenza viruses failed to be transmitted among pigs (127). Infection of pigs with a lowly pathogenic avian influenza virus resulted in only low titers of shed virus (128). We propose that low polymerase activity in pig cells is responsible in part for the low viral titers usually obtained from swine infected with avian influenza virus (10, 30, 127) and, as a consequence, could also be a contributing factor in inefficient virus spread. Several recent reports indicated that sialic acid receptor distributions in the respiratory tracts of pigs and humans are indeed similar (29–31), challenging the theory of the pig as a mixing vessel for influenza virus reassortants. The avian influenza virus receptor (NeuAcα2,3Gal) was found only in bronchioles and alveoli, not in the trachea, emphasizing the resemblance between the two species. These observations and the results of our polymerase assays suggest that pigs are not a more appropriate mixing vessel for influenza viruses than humans. We and others speculate that observations of more genetic reassortments in pigs might simply be the consequence of swine husbandry and exposure of pigs to fecally contaminated material with high concentrations of avian influenza virus on farms (31).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the 7th Framework Programme of the European Commission (Pathogenesis and Transmission of Influenza in Pigs [FLUPIG] grant FP7, project no. 258084).

We thank I. Brown (AHVLA, United Kingdom) for providing NPTr and NSK cells and J. Stech (FLI, Germany), M. Peiris (HKU, China), and R. Fouchier (Erasmus, Netherlands) for the H1N1 duck Bavaria, H9N2 G1, and H5N1 Ty05 plasmids, respectively.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 17 October 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01633-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alexander DJ. 2000. A review of avian influenza in different bird species. Vet. Microbiol. 74:3–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fouchier RA, Munster V, Wallensten A, Bestebroer TM, Herfst S, Smith D, Rimmelzwaan GF, Olsen B, Osterhaus AD. 2005. Characterization of a novel influenza A virus hemagglutinin subtype (H16) obtained from black-headed gulls. J. Virol. 79:2814–2822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM, Kawaoka Y. 1992. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol. Rev. 56:152–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kilbourne ED. 2006. Influenza pandemics of the 20th century. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:9–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kawaoka Y, Krauss S, Webster RG. 1989. Avian-to-human transmission of the PB1 gene of influenza A viruses in the 1957 and 1968 pandemics. J. Virol. 63:4603–4608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scholtissek C, Rohde W, Von Hoyningen V, Rott R. 1978. On the origin of the human influenza virus subtypes H2N2 and H3N2. Virology 87:13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scholtissek C. 1994. Source for influenza pandemics. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 10:455–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brown IH. 2008. The role of pigs in interspecies transmission, p 88–100 In Klenk H-D, Matrosovich MN, Stech J. (ed), Avian influenza, vol 27. Monographs in virology. Krager, Basel, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van Reeth K. 2007. Avian and swine influenza viruses: our current understanding of the zoonotic risk. Vet. Res. 38:243–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kida H, Ito T, Yasuda J, Shimizu Y, Itakura C, Shortridge KF, Kawaoka Y, Webster RG. 1994. Potential for transmission of avian influenza viruses to pigs. J. Gen. Virol. 75:2183–2188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beare AS, Webster RG. 1991. Replication of avian influenza viruses in humans. Arch. Virol. 119:37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brown IH, Alexander DJ, Chakraverty P, Harris PA, Manvell RJ. 1994. Isolation of an influenza A virus of unusual subtype (H1N7) from pigs in England, and the subsequent experimental transmission from pig to pig. Vet. Microbiol. 39:125–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown IH, Harris PA, McCauley JW, Alexander DJ. 1998. Multiple genetic reassortment of avian and human influenza A viruses in European pigs, resulting in the emergence of an H1N2 virus of novel genotype. J. Gen. Virol. 79:2947–2955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Castrucci MR, Donatelli I, Sidoli L, Barigazzi G, Kawaoka Y, Webster RG. 1993. Genetic reassortment between avian and human influenza A viruses in Italian pigs. Virology 193:503–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sugimura T, Yonemochi H, Ogawa T, Tanaka Y, Kumagai T. 1980. Isolation of a recombinant influenza virus (Hsw 1 N2) from swine in Japan. Arch. Virol. 66:271–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown IH. 2000. The epidemiology and evolution of influenza viruses in pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 74:29–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gaydos JC, Top FH, Jr, Hodder RA, Russell PK. 2006. Swine influenza A outbreak, Fort Dix, New Jersey, 1976. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:23–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Myers KP, Olsen CW, Gray GC. 2007. Cases of swine influenza in humans: a review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:1084–1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rota PA, Rocha EP, Harmon MW, Hinshaw VS, Sheerar MG, Kawaoka Y, Cox NJ, Smith TF. 1989. Laboratory characterization of a swine influenza virus isolated from a fatal case of human influenza. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:1413–1416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, Shaw MW, Lindstrom S, Garten RJ, Gubareva LV, Xu X, Bridges CB, Uyeki TM. 2009. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 360:2605–2615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garten RJ, Davis CT, Russell CA, Shu B, Lindstrom S, Balish A, Sessions WM, Xu X, Skepner E, Deyde V, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Gubareva L, Barnes J, Smith CB, Emery SL, Hillman MJ, Rivailler P, Smagala J, de Graaf M, Burke DF, Fouchier RA, Pappas C, Alpuche-Aranda CM, Lopez-Gatell H, Olivera H, Lopez I, Myers CA, Faix D, Blair PJ, Yu C, Keene KM, Dotson PD, Jr, Boxrud D, Sambol AR, Abid SH, ST George K, Bannerman T, Moore AL, Stringer DJ, Blevins P, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Ginsberg M, Kriner P, Waterman S, Smole S, Guevara HF, Belongia EA, Clark PA, Beatrice ST, Donis R, Katz J, Finelli L, Bridges CB, Shaw M, Jernigan DB, Uyeki TM, Smith DJ, Klimov AI, Cox NJ. 2009. Antigenic and genetic characteristics of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza viruses circulating in humans. Science 325:197–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith GJ, Vijaykrishna D, Bahl J, Lycett SJ, Worobey M, Pybus OG, Ma SK, Cheung CL, Raghwani J, Bhatt S, Peiris JS, Guan Y, Rambaut A. 2009. Origins and evolutionary genomics of the 2009 swine-origin H1N1 influenza A epidemic. Nature 459:1122–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ito T, Couceiro JN, Kelm S, Baum LG, Krauss S, Castrucci MR, Donatelli I, Kida H, Paulson JC, Webster RG, Kawaoka Y. 1998. Molecular basis for the generation in pigs of influenza A viruses with pandemic potential. J. Virol. 72:7367–7373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kida H, Shortridge KF, Webster RG. 1988. Origin of the hemagglutinin gene of H3N2 influenza viruses from pigs in China. Virology 162:160–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ma W, Kahn RE, Richt JA. 2008. The pig as a mixing vessel for influenza viruses: human and veterinary implications. J. Mol. Genet. Med. 3:158–166 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scholtissek C, Burger H, Kistner O, Shortridge KF. 1985. The nucleoprotein as a possible major factor in determining host specificity of influenza H3N2 viruses. Virology 147:287–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Webster RG, Campbell CH, Granoff A. 1971. The “in vivo” production of “new” influenza A viruses. I. Genetic recombination between avian and mammalian influenza viruses. Virology 44:317–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yasuda J, Shortridge KF, Shimizu Y, Kida H. 1991. Molecular evidence for a role of domestic ducks in the introduction of avian H3 influenza viruses to pigs in southern China, where the A/Hong Kong/68 (H3N2) strain emerged. J. Gen. Virol. 72 (Pt 8):2007–2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nelli RK, Kuchipudi SV, White GA, Perez BB, Dunham SP, Chang KC. 2010. Comparative distribution of human and avian type sialic acid influenza receptors in the pig. BMC Vet. Res. 6:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Trebbien R, Larsen LE, Viuff BM. 2011. Distribution of sialic acid receptors and influenza A virus of avian and swine origin in experimentally infected pigs. Virol. J. 8:434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Van Poucke SG, Nicholls JM, Nauwynck HJ, Van Reeth K. 2010. Replication of avian, human and swine influenza viruses in porcine respiratory explants and association with sialic acid distribution. Virol. J. 7:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Naffakh N, Tomoiu A, Rameix-Welti MA, van der Werf S. 2008. Host restriction of avian influenza viruses at the level of the ribonucleoproteins. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 62:403–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huang TS, Palese P, Krystal M. 1990. Determination of influenza virus proteins required for genome replication. J. Virol. 64:5669–5673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bussey KA, Bousse TL, Desmet EA, Kim B, Takimoto T. 2010. PB2 residue 271 plays a key role in enhanced polymerase activity of influenza A viruses in mammalian host cells. J. Virol. 84:4395–4406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Foeglein A, Loucaides EM, Mura M, Wise HM, Barclay WS, Digard P. 2011. Influence of PB2 host-range determinants on the intranuclear mobility of the influenza A virus polymerase. J. Gen. Virol. 92:1650–1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gabriel G, Dauber B, Wolff T, Planz O, Klenk HD, Stech J. 2005. The viral polymerase mediates adaptation of an avian influenza virus to a mammalian host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:18590–18595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Labadie K, Dos Santos Afonso E, Rameix-Welti MA, van der Werf S, Naffakh N. 2007. Host-range determinants on the PB2 protein of influenza A viruses control the interaction between the viral polymerase and nucleoprotein in human cells. Virology 362:271–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Massin P, van der Werf S, Naffakh N. 2001. Residue 627 of PB2 is a determinant of cold sensitivity in RNA replication of avian influenza viruses. J. Virol. 75:5398–5404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moncorge O, Mura M, Barclay WS. 2010. Evidence for avian and human host cell factors that affect the activity of influenza virus polymerase. J. Virol. 84:9978–9986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Naffakh N, Massin P, Escriou N, Crescenzo-Chaigne B, van der Werf S. 2000. Genetic analysis of the compatibility between polymerase proteins from human and avian strains of influenza A viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1283–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yao Y, Mingay LJ, McCauley JW, Barclay WS. 2001. Sequences in influenza A virus PB2 protein that determine productive infection for an avian influenza virus in mouse and human cell lines. J. Virol. 75:5410–5415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Almond JW. 1977. A single gene determines the host range of influenza virus. Nature 270:617–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fornek JL, Gillim-Ross L, Santos C, Carter V, Ward JM, Cheng LI, Proll S, Katze MG, Subbarao K. 2009. A single-amino-acid substitution in a polymerase protein of an H5N1 influenza virus is associated with systemic infection and impaired T-cell activation in mice. J. Virol. 83:11102–11115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fouchier RA, Schneeberger PM, Rozendaal FW, Broekman JM, Kemink SA, Munster V, Kuiken T, Rimmelzwaan GF, Schutten M, Van Doornum GJ, Koch G, Bosman A, Koopmans M, Osterhaus AD. 2004. Avian influenza A virus (H7N7) associated with human conjunctivitis and a fatal case of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:1356–1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gao P, Watanabe S, Ito T, Goto H, Wells K, McGregor M, Cooley AJ, Kawaoka Y. 1999. Biological heterogeneity, including systemic replication in mice, of H5N1 influenza A virus isolates from humans in Hong Kong. J. Virol. 73:3184–3189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hatta M, Gao P, Halfmann P, Kawaoka Y. 2001. Molecular basis for high virulence of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza A viruses. Science 293:1840–1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hatta M, Hatta Y, Kim JH, Watanabe S, Shinya K, Nguyen T, Lien PS, Le QM, Kawaoka Y. 2007. Growth of H5N1 influenza A viruses in the upper respiratory tracts of mice. PLoS Pathog. 3:1374–1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Munster VJ, de Wit E, van Riel D, Beyer WE, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, Kuiken T, Fouchier RA. 2007. The molecular basis of the pathogenicity of the Dutch highly pathogenic human influenza A H7N7 viruses. J. Infect. Dis. 196:258–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Salomon R, Franks J, Govorkova EA, Ilyushina NA, Yen HL, Hulse-Post DJ, Humberd J, Trichet M, Rehg JE, Webby RJ, Webster RG, Hoffmann E. 2006. The polymerase complex genes contribute to the high virulence of the human H5N1 influenza virus isolate A/Vietnam/1203/04. J. Exp. Med. 203:689–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shinya K, Hamm S, Hatta M, Ito H, Ito T, Kawaoka Y. 2004. PB2 amino acid at position 627 affects replicative efficiency, but not cell tropism, of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza A viruses in mice. Virology 320:258–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shinya K, Watanabe S, Ito T, Kasai N, Kawaoka Y. 2007. Adaptation of an H7N7 equine influenza A virus in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 88:547–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Steel J, Lowen AC, Mubareka S, Palese P. 2009. Transmission of influenza virus in a mammalian host is increased by PB2 amino acids 627K or 627E/701N. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Subbarao EK, London W, Murphy BR. 1993. A single amino acid in the PB2 gene of influenza A virus is a determinant of host range. J. Virol. 67:1761–1764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pensaert M, Ottis K, Vandeputte J, Kaplan MM, Bachmann PA. 1981. Evidence for the natural transmission of influenza A virus from wild ducks to swine and its potential importance for man. Bull. World Health Organ. 59:75–78 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Scholtissek C, Burger H, Bachmann PA, Hannoun C. 1983. Genetic relatedness of hemagglutinins of the H1 subtype of influenza A viruses isolated from swine and birds. Virology 129:521–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hossain MJ, Hickman D, Perez DR. 2008. Evidence of expanded host range and mammalian-associated genetic changes in a duck H9N2 influenza virus following adaptation in quail and chickens. PLoS One 3:e3170 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Li J, Ishaq M, Prudence M, Xi X, Hu T, Liu Q, Guo D. 2009. Single mutation at the amino acid position 627 of PB2 that leads to increased virulence of an H5N1 avian influenza virus during adaptation in mice can be compensated by multiple mutations at other sites of PB2. Virus Res. 144:123–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li Z, Chen H, Jiao P, Deng G, Tian G, Li Y, Hoffmann E, Webster RG, Matsuoka Y, Yu K. 2005. Molecular basis of replication of duck H5N1 influenza viruses in a mammalian mouse model. J. Virol. 79:12058–12064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Manz B, Brunotte L, Reuther P, Schwemmle M. 2012. Adaptive mutations in NEP compensate for defective H5N1 RNA replication in cultured human cells. Nat. Commun. 3:802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mase M, Tanimura N, Imada T, Okamatsu M, Tsukamoto K, Yamaguchi S. 2006. Recent H5N1 avian influenza A virus increases rapidly in virulence to mice after a single passage in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 87:3655–3659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. de Jong MD, Simmons CP, Thanh TT, Hien VM, Smith GJ, Chau TN, Hoang DM, Chau NV, Khanh TH, Dong VC, Qui PT, Cam BV, Ha do Q, Guan Y, Peiris JS, Chinh NT, Hien TT, Farrar J. 2006. Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. Nat. Med. 12:1203–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Puthavathana P, Auewarakul P, Charoenying PC, Sangsiriwut K, Pooruk P, Boonnak K, Khanyok R, Thawachsupa P, Kijphati R, Sawanpanyalert P. 2005. Molecular characterization of the complete genome of human influenza H5N1 virus isolates from Thailand. J. Gen. Virol. 86:423–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Smith GJ, Naipospos TS, Nguyen TD, de Jong MD, Vijaykrishna D, Usman TB, Hassan SS, Nguyen TV, Dao TV, Bui NA, Leung YH, Cheung CL, Rayner JM, Zhang JX, Zhang LJ, Poon LL, Li KS, Nguyen VC, Hien TT, Farrar J, Webster RG, Chen H, Peiris JS, Guan Y. 2006. Evolution and adaptation of H5N1 influenza virus in avian and human hosts in Indonesia and Vietnam. Virology 350:258–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. de Wit E, Munster VJ, van Riel D, Beyer WE, Rimmelzwaan GF, Kuiken T, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. 2010. Molecular determinants of adaptation of highly pathogenic avian influenza H7N7 viruses to efficient replication in the human host. J. Virol. 84:1597–1606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gabriel G, Herwig A, Klenk HD. 2008. Interaction of polymerase subunit PB2 and NP with importin alpha1 is a determinant of host range of influenza A virus. PLoS Pathog. 4:e11 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0040011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gabriel G, Klingel K, Otte A, Thiele S, Hudjetz B, Arman-Kalcek G, Sauter M, Shmidt T, Rother F, Baumgarte S, Keiner B, Hartmann E, Bader M, Brownlee GG, Fodor E, Klenk HD. 2011. Differential use of importin-alpha isoforms governs cell tropism and host adaptation of influenza virus. Nat. Commun. 2:156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tarendeau F, Boudet J, Guilligay D, Mas PJ, Bougault CM, Boulo S, Baudin F, Ruigrok RW, Daigle N, Ellenberg J, Cusack S, Simorre JP, Hart DJ. 2007. Structure and nuclear import function of the C-terminal domain of influenza virus polymerase PB2 subunit. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14:229–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gao Y, Zhang Y, Shinya K, Deng G, Jiang Y, Li Z, Guan Y, Tian G, Li Y, Shi J, Liu L, Zeng X, Bu Z, Xia X, Kawaoka Y, Chen H. 2009. Identification of amino acids in HA and PB2 critical for the transmission of H5N1 avian influenza viruses in a mammalian host. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000709 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mehle A, Doudna JA. 2009. Adaptive strategies of the influenza virus polymerase for replication in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:21312–21316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Karasin AI, Schutten MM, Cooper LA, Smith CB, Subbarao K, Anderson GA, Carman S, Olsen CW. 2000. Genetic characterization of H3N2 influenza viruses isolated from pigs in North America, 1977–1999: evidence for wholly human and reassortant virus genotypes. Virus Res. 68:71–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhou NN, Senne DA, Landgraf JS, Swenson SL, Erickson G, Rossow K, Liu L, Yoon K, Krauss S, Webster RG. 1999. Genetic reassortment of avian, swine, and human influenza A viruses in American pigs. J. Virol. 73:8851–8856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Chen GW, Chang SC, Mok CK, Lo YL, Kung YN, Huang JH, Shih YH, Wang JY, Chiang C, Chen CJ, Shih SR. 2006. Genomic signatures of human versus avian influenza A viruses. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:1353–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Finkelstein DB, Mukatira S, Mehta PK, Obenauer JC, Su X, Webster RG, Naeve CW. 2007. Persistent host markers in pandemic and H5N1 influenza viruses. J. Virol. 81:10292–10299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Miotto O, Heiny A, Tan TW, August JT, Brusic V. 2008. Identification of human-to-human transmissibility factors in PB2 proteins of influenza A by large-scale mutual information analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 9(Suppl 1):S18 doi:10.1186/1471-2105-9-S1-S18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Miotto O, Heiny AT, Albrecht R, Garcia-Sastre A, Tan TW, August JT, Brusic V. 2010. Complete-proteome mapping of human influenza A adaptive mutations: implications for human transmissibility of zoonotic strains. PLoS One 5:e9025 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Liu Q, Qiao C, Marjuki H, Bawa B, Ma J, Guillossou S, Webby RJ, Richt JA, Ma W. 2012. Combination of PB2 271A and SR polymorphism at positions 590/591 is critical for viral replication and virulence of swine influenza virus in cultured cells and in vivo. J. Virol. 86:1233–1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Choi YK, Nguyen TD, Ozaki H, Webby RJ, Puthavathana P, Buranathal C, Chaisingh A, Auewarakul P, Hanh NT, Ma SK, Hui PY, Guan Y, Peiris JS, Webster RG. 2005. Studies of H5N1 influenza virus infection of pigs by using viruses isolated in Vietnam and Thailand in 2004. J. Virol. 79:10821–10825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Nidom CA, Takano R, Yamada S, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Daulay S, Aswadi D, Suzuki T, Suzuki Y, Shinya K, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Muramoto Y, Kawaoka Y. 2010. Influenza A (H5N1) viruses from pigs, Indonesia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:1515–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Shi WF, Gibbs MJ, Zhang YZ, Zhang Z, Zhao XM, Jin X, Zhu CD, Yang MF, Yang NN, Cui YJ, Ji L. 2008. Genetic analysis of four porcine avian influenza viruses isolated from Shandong, China. Arch. Virol. 153:211–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zhu Q, Yang H, Chen W, Cao W, Zhong G, Jiao P, Deng G, Yu K, Yang C, Bu Z, Kawaoka Y, Chen H. 2008. A naturally occurring deletion in its NS gene contributes to the attenuation of an H5N1 swine influenza virus in chickens. J. Virol. 82:220–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Jung K, Song DS, Kang BK, Oh JS, Park BK. 2007. Serologic surveillance of swine H1 and H3 and avian H5 and H9 influenza A virus infections in swine population in Korea. Prev. Vet. Med. 79:294–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Govorkova EA, Rehg JE, Krauss S, Yen HL, Guan Y, Peiris M, Nguyen TD, Hanh TH, Puthavathana P, Long HT, Buranathai C, Lim W, Webster RG, Hoffmann E. 2005. Lethality to ferrets of H5N1 influenza viruses isolated from humans and poultry in 2004. J. Virol. 79:2191–2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Maines TR, Lu XH, Erb SM, Edwards L, Guarner J, Greer PW, Nguyen DC, Szretter KJ, Chen LM, Thawatsupha P, Chittaganpitch M, Waicharoen S, Nguyen DT, Nguyen T, Nguyen HH, Kim JH, Hoang LT, Kang C, Phuong LS, Lim W, Zaki S, Donis RO, Cox NJ, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. 2005. Avian influenza (H5N1) viruses isolated from humans in Asia in 2004 exhibit increased virulence in mammals. J. Virol. 79:11788–11800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zitzow LA, Rowe T, Morken T, Shieh WJ, Zaki S, Katz JM. 2002. Pathogenesis of avian influenza A (H5N1) viruses in ferrets. J. Virol. 76:4420–4429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Isoda N, Sakoda Y, Kishida N, Bai GR, Matsuda K, Umemura T, Kida H. 2006. Pathogenicity of a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus, A/chicken/Yamaguchi/7/04 (H5N1) in different species of birds and mammals. Arch. Virol. 151:1267–1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Shortridge KF, Zhou NN, Guan Y, Gao P, Ito T, Kawaoka Y, Kodihalli S, Krauss S, Markwell D, Murti KG, Norwood M, Senne D, Sims L, Takada A, Webster RG. 1998. Characterization of avian H5N1 influenza viruses from poultry in Hong Kong. Virology 252:331–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Massin P, Rodrigues P, Marasescu M, van der Werf S, Naffakh N. 2005. Cloning of the chicken RNA polymerase I promoter and use for reverse genetics of influenza A viruses in avian cells. J. Virol. 79:13811–13816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Wang Z, Duke GM. 2007. Cloning of the canine RNA polymerase I promoter and establishment of reverse genetics for influenza A and B in MDCK cells. Virol. J. 4:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Zobel A, Neumann G, Hobom G. 1993. RNA polymerase I catalysed transcription of insert viral cDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:3607–3614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Grummt I, Maier U, Ohrlein A, Hassouna N, Bachellerie JP. 1985. Transcription of mouse rDNA terminates downstream of the 3′ end of 28S RNA and involves interaction of factors with repeated sequences in the 3′ spacer. Cell 43:801–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Howard W, Hayman A, Lackenby A, Whiteley A, Londt B, Banks J, McCauley J, Barclay W. 2007. Development of a reverse genetics system enabling the rescue of recombinant avian influenza virus A/Turkey/England/50-92/91 (H5N1). Avian Dis. 51:393–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. van Doremalen N, Shelton H, Roberts KL, Jones IM, Pickles RJ, Thompson CI, Barclay WS. 2011. A single amino acid in the HA of pH1N1 2009 influenza virus affects cell tropism in human airway epithelium, but not transmission in ferrets. PLoS One 6:e25755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Elleman CJ, Barclay WS. 2004. The M1 matrix protein controls the filamentous phenotype of influenza A virus. Virology 321:144–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Neumann G, Watanabe T, Ito H, Watanabe S, Goto H, Gao P, Hughes M, Perez DR, Donis R, Hoffmann E, Hobom G, Kawaoka Y. 1999. Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:9345–9350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Ling X, Arnheim N. 1994. Cloning and identification of the pig ribosomal gene promoter. Gene 150:375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Ferrari M, Scalvini A, Losio MN, Corradi A, Soncini M, Bignotti E, Milanesi E, Ajmone-Marsan P, Barlati S, Bellotti D, Tonelli M. 2003. Establishment and characterization of two new pig cell lines for use in virological diagnostic laboratories. J. Virol. Methods 107:205–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Feng L, Li F, Zheng X, Pan W, Zhou K, Liu Y, He H, Chen L. 2009. The mouse Pol I terminator is more efficient than the hepatitis delta virus ribozyme in generating influenza-virus-like RNAs with precise 3′ ends in a plasmid-only-based virus rescue system. Arch. Virol. 154:1151–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Brookes SM, Nunez A, Choudhury B, Matrosovich M, Essen SC, Clifford D, Slomka MJ, Kuntz-Simon G, Garcon F, Nash B, Hanna A, Heegaard PM, Queguiner S, Chiapponi C, Bublot M, Garcia JM, Gardner R, Foni E, Loeffen W, Larsen L, Van Reeth K, Banks J, Irvine RM, Brown IH. 2010. Replication, pathogenesis and transmission of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus in non-immune pigs. PLoS One 5:e9068 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Lange E, Kalthoff D, Blohm U, Teifke JP, Breithaupt A, Maresch C, Starick E, Fereidouni S, Hoffmann B, Mettenleiter TC, Beer M, Vahlenkamp TW. 2009. Pathogenesis and transmission of the novel swine-origin influenza virus A/H1N1 after experimental infection of pigs. J. Gen. Virol. 90:2119–2123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Brown IH. 11 January. 2012. History and epidemiology of swine influenza in Europe. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. doi:10.1007/82_2011_194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Pasma T, Joseph T. 2010. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 infection in swine herds, Manitoba, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:706–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Ottis K, Bachmann PA. 1980. Occurrence of Hsw 1 N 1 subtype influenza A viruses in wild ducks in Europe. Arch. Virol. 63:185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Guan Y, Shortridge KF, Krauss S, Webster RG. 1999. Molecular characterization of H9N2 influenza viruses: were they the donors of the “internal” genes of H5N1 viruses in Hong Kong? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:9363–9367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Butt KM, Smith GJ, Chen H, Zhang LJ, Leung YH, Xu KM, Lim W, Webster RG, Yuen KY, Peiris JS, Guan Y. 2005. Human infection with an avian H9N2 influenza A virus in Hong Kong in 2003. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5760–5767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Cheng VC, Chan JF, Wen X, Wu WL, Que TL, Chen H, Chan KH, Yuen KY. 2011. Infection of immunocompromised patients by avian H9N2 influenza A virus. J. Infect. 62:394–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Peiris M, Yuen KY, Leung CW, Chan KH, Ip PL, Lai RW, Orr WK, Shortridge KF. 1999. Human infection with influenza H9N2. Lancet 354:916–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Oner AF, Bay A, Arslan S, Akdeniz H, Sahin HA, Cesur Y, Epcacan S, Yilmaz N, Deger I, Kizilyildiz B, Karsen H, Ceyhan M. 2006. Avian influenza A (H5N1) infection in eastern Turkey in 2006. N. Engl. J. Med. 355:2179–2185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Jagger BW, Wise HM, Kash JC, Walters KA, Wills NM, Xiao YL, Dunfee RL, Schwartzman LM, Ozinsky A, Bell GL, Dalton RM, Lo A, Efstathiou S, Atkins JF, Firth AE, Taubenberger JK, Digard P. 2012. An overlapping protein-coding region in influenza A virus segment 3 modulates the host response. Science 337:199–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Naffakh N, Massin P, van der Werf S. 2001. The transcription/replication activity of the polymerase of influenza A viruses is not correlated with the level of proteolysis induced by the PA subunit. Virology 285:244–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Bao Y, Bolotov P, Dernovoy D, Kiryutin B, Zaslavsky L, Tatusova T, Ostell J, Lipman D. 2008. The influenza virus resource at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. J. Virol. 82:596–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Mehle A, Doudna JA. 2008. An inhibitory activity in human cells restricts the function of an avian-like influenza virus polymerase. Cell Host Microbe 4:111–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Brown EG, Liu H, Kit LC, Baird S, Nesrallah M. 2001. Pattern of mutation in the genome of influenza A virus on adaptation to increased virulence in the mouse lung: identification of functional themes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:6883–6888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Ping J, Dankar SK, Forbes NE, Keleta L, Zhou Y, Tyler S, Brown EG. 2010. PB2 and hemagglutinin mutations are major determinants of host range and virulence in mouse-adapted influenza A virus. J. Virol. 84:10606–10618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Herfst S, Chutinimitkul S, Ye J, de Wit E, Munster VJ, Schrauwen EJ, Bestebroer TM, Jonges M, Meijer A, Koopmans M, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, Perez DR, Fouchier RA. 2010. Introduction of virulence markers in PB2 of pandemic swine-origin influenza virus does not result in enhanced virulence or transmission. J. Virol. 84:3752–3758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Zhang S, Wang Q, Wang J, Mizumoto K, Toyoda T. 2012. Two mutations in the C-terminal domain of influenza virus RNA polymerase PB2 enhance transcription by enhancing cap-1 RNA binding activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1819:78–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Seo SH, Hoffmann E, Webster RG. 2002. Lethal H5N1 influenza viruses escape host anti-viral cytokine responses. Nat. Med. 8:950–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Lee DC, Mok CK, Law AH, Peiris M, Lau AS. 2010. Differential replication of avian influenza H9N2 viruses in human alveolar epithelial A549 cells. Virol. J. 7:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Choi YK, Ozaki H, Webby RJ, Webster RG, Peiris JS, Poon L, Butt C, Leung YH, Guan Y. 2004. Continuing evolution of H9N2 influenza viruses in Southeastern China. J. Virol. 78:8609–8614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Wan H, Sorrell EM, Song H, Hossain MJ, Ramirez-Nieto G, Monne I, Stevens J, Cattoli G, Capua I, Chen LM, Donis RO, Busch J, Paulson JC, Brockwell C, Webby R, Blanco J, Al-Natour MQ, Perez DR. 2008. Replication and transmission of H9N2 influenza viruses in ferrets: evaluation of pandemic potential. PLoS One 3:e2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Punyadarsaniya D, Liang CH, Winter C, Petersen H, Rautenschlein S, Hennig-Pauka I, Schwegmann-Wessels C, Wu CY, Wong CH, Herrler G. 2011. Infection of differentiated porcine airway epithelial cells by influenza virus: differential susceptibility to infection by porcine and avian viruses. PLoS One 6:e28429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Uyeki TM, Chong YH, Katz JM, Lim W, Ho YY, Wang SS, Tsang TH, Au WW, Chan SC, Rowe T, Hu-Primmer J, Bell JC, Thompson WW, Bridges CB, Cox NJ, Mak KH, Fukuda K. 2002. Lack of evidence for human-to-human transmission of avian influenza A (H9N2) viruses in Hong Kong, China 1999. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:154–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. WHO June 2012. Cumulative number of confirmed human cases of avian influenza A (H5N1) reported to WHO. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/H5N1_cumulative_table_archives/en/index.html [Google Scholar]