Abstract

Enterovirus 71 (EV71) is the causative agent of hand-foot-and-mouth disease and can trigger neurological disorders. EV71 outbreaks are a major public health concern in Asia-Pacific countries. By performing experimental-mathematical investigation, we demonstrate here that viral productivity and transmissibility but not viral cytotoxicity are drastically different among EV71 strains and can be associated with their epidemiological backgrounds. This is the first report demonstrating the dynamics of nonenveloped virus replication in cell culture using mathematical modeling.

TEXT

Human enteroviruses are nonenveloped viruses with a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome that belong to the family Picornaviridae (1, 2). Enterovirus 71 (EV71) is one of the human enteroviruses and was first described in 1974 (3). It is well known that EV71 is the major causative agent of hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD), a common febrile disease occurring mainly in infants and young children (1, 4). Although HFMD is usually self-limiting, EV71 infection can result in neurological disorders such as aseptic meningitis, flaccid paralysis, and fatal encephalitis (1, 4). However, there are no specific therapies for severe EV71 infections.

EV71 can be transmitted through the fecal-oral and respiratory routes (1). Since the 1970s, EV71 outbreaks have been periodically reported throughout the world (4, 5). In particular, since the late 1990s, severe EV71 outbreaks have occurred frequently in several countries in the Asia-Pacific region, including Taiwan, mainland China, Malaysia, and Vietnam, and are among the major concerns in the fields of epidemiology and public health in these countries (4, 5).

The dynamics of virus replication is complex because this event is composed of the all-at-once creation and destruction of infected cells along with virus propagation. Mathematical analysis is one of the most powerful approaches used to reveal the complicated events in the viral life cycle. By applying mathematical analysis to experimental data, we are able to quantitatively understand the dynamics of virus replication as estimated numerical parameters such as the half-life of infected cells (log2/δ), the burst size of infectious viruses (p/δ; the net amount of virions produced by a cell during its lifetime), and the basic reproductive number (R0 = pβTmax/δc; the number of cells newly infected by an infected cell). These parameters may provide novel insights into the dynamics of virus replication that cannot be addressed by conventional experimental techniques. So far, mathematical models have been used to study the replication dynamics of enveloped viruses such as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) (6–8) and influenza virus (9–12) in in vitro cell culture. In order to obtain robust and reliable results by mathematical analysis, high-quality time course data are needed. Although some mathematical models of nonenveloped viruses focusing on viral replication kinetics in an infected cell have been reported (13–15), there is no report of the use of mathematical modeling and experimental data for the investigation of the dynamics of nonenveloped virus infection in cell culture.

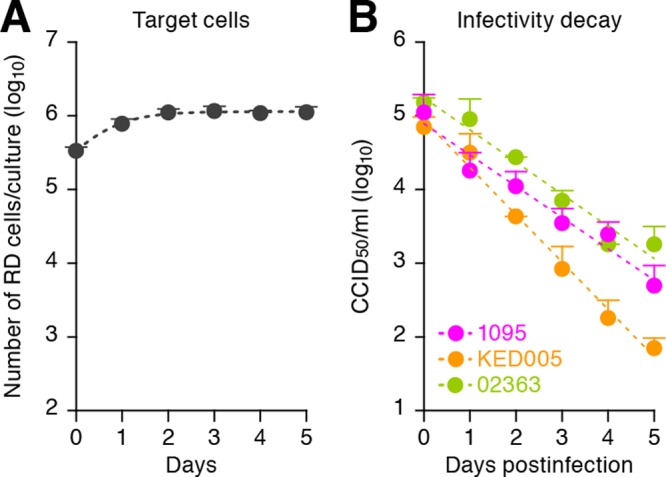

To quantitatively elucidate the dynamics of EV71 replication, we first estimated the growth kinetics of RD cells, which have been commonly used for EV71 studies (16), under normal (i.e., mock-infected) conditions (Fig. 1A). To estimate viral growth kinetics in cell culture, we used the following mathematical model:

| (1) |

where the variable T(t) is the number of RD cells at time t and the parameters g and Tmax are the growth rate of RD cells (i.e., log2/g is the doubling time) and the carrying capacity of a 12-well plate, respectively. Nonlinear least-squares regression (FindMinimum package of Mathematica 8.0) was performed to fit the model of equation 1 to the time course of the number of RD cells under normal conditions, yielding values of g = 1.58 ± 0.11/day (doubling time of log2/g = 10.57 ± 0.69 h) and Tmax = 1.18 ± 0.11 × 106 cells/ml.

Fig 1.

Dynamics of RD cell growth and decay of EV71 infectivity. (A) Growth kinetics of RD cells. Two hundred thousand RD cells in 1 ml of culture medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium containing 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics) were seeded into the wells of a 12-well plate. By harvesting the cells daily for 5 days, the growth kinetics of RD cells under this condition was estimated as described in the text. The estimated numerical values are g = 1.58 ± 0.11/day and Tmax = 1.18 × 106 ± 0.11 × 106 cells/ml. (B) Decay of EV71 infectivity. One million CCID50 of the three strains of EV71 solution in 1 ml of culture medium in the wells of a 12-well plate were incubated in an incubator (5% CO2 and 37°C). The incubated virus solutions were harvested daily for 5 days, and the infectivity of the incubated virus solution, V/(t), was titrated as described in the text. The estimated numerical values are c = 1.01 ± 0.16, 1.46 ± 0.16, and 0.99 ± 0.08/day for strains 02363, KED005, and 1095, respectively. These assays were performed in triplicate. The average experimental data are shown as dots with standard deviations represented by bars, and the best fit of the mathematical model is shown as a broken line.

In this study, three representative strains of EV71, 1095 (17, 18), KED005 (19), and 02363 (20), that were isolated from HFMD patients with different epidemiological backgrounds were used (Table 1). For virus preparation and titration, we performed the following procedures. The virus solutions were prepared by using RD cells as previously described (21, 22). Infectivity was quantified by using RD cells and was calculated by the Kärber method and expressed in 50% cell culture infective doses (CCID50) as previously described (21–23).

Table 1.

Three EV71 strains used in this study

Then we estimated the infectivity decay, c, of each virus strain under cell culture conditions (Fig. 1B). By performing a linear regression analysis that fits logV(t) = logV(0) − ct to those data, the half-life of EV71 infectivity (log2/c) was calculated. Although the infectivity half-life of strain 1095 (16.53 ± 1.71 h) was comparable to that of strain 02363 (16.81 ± 2.98 h; P = 0.98 by Student's t test), the infectivity half-life of strain KED005 (11.52 ± 1.34 h) was significantly different from those of strains 1095 (P = 0.0084 by Student's t test) and 02363 (P = 0.049 by Student's t test). These results suggest that these EV71 strains differ in stability. In this regard, we found that 11 amino acid residues of the viral capsid proteins of the three EV71 strains used are different (data not shown). In fact, it has been suggested that the stability of poliovirus, a well-studied virus belonging to the family Picornaviridae, is determined by the amino acid sequences and/or conformations of viral capsid proteins VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4 (24, 25). Therefore, it would be reasonable to assume that the difference in the decay of viral infectivity is due to the stability of infectious viral particles, which is influenced by the sequences and/or conformations of viral capsid proteins. Moreover, EV71 infection of humans occurs through the fecal-oral and respiratory routes (5). Our results suggest that EV71 stability may result in the survival of infectious viruses in the environment, which can be associated with the efficiency of EV71 spread in the human community.

In order to apply mathematical analyses robustly, we performed a time course infection experiment with RD cells (Fig. 2 and 3). To describe the in vitro kinetics of EV71 replication in our experimental system, we used a basic mathematical model with an eclipse phase of infection (i.e., the non-virus-producing period) as infection proceeds for analyzing viral kinetics (26, 27). Our model is defined by the equations

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where T(t), I1(t), and I1(t) are the numbers of target cells, ecliptic cells, and virus-producing cells per milliliter of culture, respectively, and V(t) is viral infectivity measured the number of CCID50 per milliliter of culture supernatant. The parameters k, δ, and β represent the rate of VP1 protein expression after virus infection, the death rate of virus-producing cells, and the rate constant for infection of target cells by virus per day, respectively. In addition, we assumed that each infected cell releases p virus particle per day and that those progeny virus particles lose their infectivity at a rate of c per day. A schematic of our mathematical model is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig 2.

Schematic of our mathematical model. The variables T(t), I1(t), and I2(t) are the numbers of target cells, ecliptic cells, and virus-producing cells, respectively, and V/(t) is viral infectivity. The parameters, k, δ, and β represent the rate of viral protein expression after infection, the rate of virus-producing cell death, and the rate constant of target cell infection by virus per day, respectively. It is assumed that infected cells release virus particles at a rate of p and that these virus particles lose their infectivity at a rate of c per day.

Fig 3.

Dynamics of EV71 replication in RD cells. As described in the legend to Fig. 1, 2 × 105 RD cells were seeded 1 day prior to infection and the cells were counted just before infection. The cells were inoculated with EV71 at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01 in 0.5 ml of culture medium in an incubator (5% CO2 and 37°C). At 1 h postinoculation, the culture supernatant was replaced with 1 ml of fresh culture medium. The cells and culture supernatants were harvested daily for 5 days. The virus infectivity in the culture supernatant was titrated as described in the text, and the harvested cells were counted. The cells were then used for flow cytometry according to the following procedure. The cells were permeabilized with Cytoperm/Cytofix solution (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacture's protocol and stained with a mouse anti-VP1 monoclonal antibody (clone MA105) labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (22). The number of cells positive for the VP1 antigen was determined by using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences), and the numbers of VP1-positive cells (i.e., virus-producing cells) and VP1-negative cells at each time point were calculated. (A to C) The virus infectivity in the culture supernatant (A), the number of VP1-positive cells (virus-producing cells) in the culture (B), and the number of VP1-negative cells (target cells and ecliptic cells) in the culture (C), respectively, are shown. (D and E) Mathematical predictions of the kinetics of target cells in the culture (D) and ecliptic cells in the culture (E), respectively, are shown. These assays were performed in triplicate. In panels A to C, the average experimental data are shown as dots with standard deviations indicated by bars. In panels A to E, the best fit of the mathematical model is shown as a broken line.

We simultaneously fitted equations 2 to 5 to the concentrations of VP1-negative and VP1-positive RD cells and the level of viral infectivity in the culture supernatant (CCID50) by using nonlinear least-squares regression, which minimizes the objective function

| (6) |

where T(ti) + I1(t), I2(t), and V(t) are the values predicted by the model for viral-protein-negative cells, viral-protein-positive cells, and viral infectivity, given by the solution of equations 2 to 5 at measurement time ti (ti = 0,…, 4 days for strain 1095 or 0,…, 5 days for strains KED005 and 02363). The variables with a superscript e are the corresponding experimental measurements of those quantities [Ne(ti) represents the concentration of VP1-negative RD cells in our experiment]. Here we note that g and Tmax were estimated to be 1.58 per day and 1.18 × 106 cells per ml of medium from RD cell growth experiments, respectively (Fig. 1A), and k was assumed to be 4.0 per day (i.e., the delay prior to expression of VP1 is 6 h) in the fitting. In addition, we used c values of 1.01, 1.46, and 0.99/day for strains 02363, KED005, and 1095, respectively (Fig. 1B). The remaining three parameters (β, δ, and p), along with two initial values for I1(0) and V(0) [T(0) = 3.0 × 105 for strains 02363 and KED005, T(0) = 3.7 × 105 for strain 1095, and I2(0) = 0 for all strains were fixed], were determined by fitting the model to the data. The estimated parameters of the model and derived quantities are given in Table 2. Here the estimated initial values are I1(0) = 67.2 ± 116.4, 155.3 ± 37.8, and 830.9 ± 744.3 cells/ml and V(0) = 582.5 ± 298.8, 1,979.8 ± 1,061.8, and 2,674.5 ± 4,559.0 CCID50/ml for strains 02363, KED005, and 1095, respectively.

Table 2.

Parameters estimated by mathematical-experimental analysis

| Strain | Parameters |

Derived quantities |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (10−6 CCID50/ml · day−1) | p (CCID50/day) | δ (day−1) | c (day−1) | Log2/δ (days) | p/δ (CCID50) | R0 | |

| 1095 | 0.30 ± 0.11a | 738.9 ± 153.3 | 6.22 ± 0.13 | 0.99 ± 0.08 | 2.67 ± 0.06 | 118.82 ± 25.1 | 37.35 ± 8.99 |

| KED005 | 1.41 ± 0.15 | 146.8 ± 28.2 | 19.8 ± 3.90 | 1.46 ± 0.16 | 0.86 ± 0.16 | 7.43 ± 0.38 | 8.37 ± 0.82 |

| 02363 | 5.14 ± 1.02 | 13.4 ± 5.0 | 11.41 ± 1.50 | 1.01 ± 0.16 | 1.47 ± 0.19 | 1.16 ± 0.27 | 6.75 ± 0.16 |

Values are averages and standard deviations.

As summarized in Table 2, the half-life of virus-producing cells, log2/δ, which reflects the viral cytopathic potential, seemed to be different among the three strains examined. Since the three strains were isolated from patients with HFMD (17, 19, 20), which is a common and mild EV71-associated disease, the possibility that the viruses used in this study are relatively less pathogenic should be considered. However, one previous study demonstrated that strain 1095 caused neurological disorders such as flaccid paralysis, tremor, and ataxia in infected cynomolgus monkeys (21), which suggests that the severity of the EV71-associated diseases in the patients infected with the isolated virus cannot be directly represented by the apparent virulence of the corresponding EV71 isolates. In addition, a growing number of molecular epidemiological studies suggest that there is no correlation between the severity of clinical outcomes and specific genotypes of EV71 (28). Furthermore, it is well known that younger age is one of the major risk factors associated with severe EV71 infection (5). Therefore, host factors such as immunity level, viral susceptibility, and immunopathogenicity should also be considered when estimating the severity of EV71 infection. Taken together, the findings suggest that it is conceivable that the pathogenesis caused by EV71 infection in individuals is not only determined by the viral factors of EV71 strains, which are estimated by mathematical analyses through cell culture experiments in vitro and the genotypes of EV71 isolates, but is also associated with host factors.

On the other hand, the burst size (p/δ) and the basic reproductive number (R0), which, respectively, represent the potentials of viral productivity and viral transmissibility, were drastically different in each strain compared to the difference in log2/δ (Table 2). In particular, these values of strain KED005 were significantly different from those of strain 02363, although the two viruses belong to the same subgenogroup (C1) (22). These findings suggest that a virus's productivity and transmissibility are not determined by its subgenogroup, which is based on the sequence of the VP1 region. In addition, it should be noted that the burst size and the basic reproductive number of strain 02363 were significantly lower than those of strains 1095 and KED005. It is noteworthy that strain 02363 was isolated from a sporadic patient with HFMD in Thailand in 2002 (20), while strains 1095 and KED005 were, respectively, isolated from HFMD patients during the large outbreaks in 1997 in Japan (17, 19) and Malaysia (19). However, the viral phenotypes and genotypes of EV71 remain to be clarified by using more EV71 strains with different genotypes and/or different epidemiological backgrounds. Taken together, these findings suggest that the burst size and the basic reproductive number of each EV71 strain are novel criteria exhibiting viral characteristics that can correlate with the epidemiological backgrounds of EV71 infection. In fact, Mitchell et al. have recently performed mathematical and computational modeling to quantify the replication kinetics of three different types of influenza virus (H5N1 avian influenza virus, H1N1 seasonal influenza virus, and H1N1 pandemic influenza virus that emerged in 2009) (10). In that study, the authors suggested that the basic reproductive number of each influenza virus in in vitro cell culture correlates with the efficiency of person-to-person virus transmission (10). Therefore, it would be reasonable to assume that derived quantities of viral infection such as p/δ and R0 can represent the different epidemic potentials of viruses, which could not be addressed in previous experiments by using conventional viral phenotypic markers.

In summary, we first demonstrated that novel EV71 phenotypes, the burst size and the basic reproductive number, that are estimated by our experimental-mathematical analyses could be associated with the rate of infection and transmissibility of viruses in the community. As mentioned above, EV71 outbreaks are a major concern in the Asia-Pacific region (4). Our strategy will be one of the informative approaches to estimate the epidemic potential of EV71 and will provide novel insights into the field of EV71 epidemiology in these countries. Moreover, this is the first demonstration that our mathematical modeling can be used to quantify the kinetics of not only enveloped viruses (e.g., HIV-1 and influenza virus) but also nonenveloped viruses, including EV71. The synergistic experimental-mathematical strategy is a powerful methodology and will be used to quantitatively investigate the dynamics of virus infections in a way that is not possible by conventional experimental strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Naoko Misawa (Laboratory of Viral Pathogenesis, Institute for Virus Research, Kyoto University) for her generous help with this study.

This research was supported in part by the following: Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases (to Y.N., H.S., and Y.K.) from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan; Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists B23790500 (to K.S.) and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research B22390092 (to H.S.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS); the Uehara Memorial Foundation (to K.S.); the Shimizu Foundation for Immunological Research Grant (to K.S.); the JST PRESTO program (to S.I.); and the Aihara Innovative Mathematical Modeling Project, JSPS, through the Funding Program for World-Leading Innovative R & D on Science and Technology (FIRST program), initiated by the Council for Science and Technology Policy (to S.I., K.S., and K.A.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 October 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Pallansch M, Roos R. 2007. Enteroviruses: polioviruses, coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and newer enteroviruses, p 839–893 In Knipe D. M., Howley P. M. (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed, vol 2 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 2. Racaniello VR. 2007. Picornaviridae: the viruses and their replication, p 795–838 In Knipe D. M., Howley P. M. (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed, vol 2 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schmidt NJ, Lennette EH, Ho HH. 1974. An apparently new enterovirus isolated from patients with disease of the central nervous system. J. Infect. Dis. 129:304–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization 2011. A guide to clinical management and public health response for hand, hoot and mouth disease (HFMD). WHO Press, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 5. Solomon T, Lewthwaite P, Perera D, Cardosa MJ, McMinn P, Ooi MH. 2010. Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of enterovirus 71. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10:778–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dimitrov DS, Willey RL, Sato H, Chang LJ, Blumenthal R, Martin MA. 1993. Quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection kinetics. J. Virol. 67:2182–2190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iwami S, Holder BP, Beauchemin CA, Morita S, Tada T, Sato K, Igarashi T, Miura T. 2012. Quantification system for the viral dynamics of a highly pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus based on an in vitro experiment and a mathematical model. Retrovirology 9:18 doi:10.1186/1742-4690-9-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iwami S, Sato K, De Boer RJ, Aihara K, Miura T, Koyanagi Y. 2012. Identifying viral parameters from in vitro cell cultures. Front. Microbiol. 3:319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beauchemin CA, McSharry JJ, Drusano GL, Nguyen JT, Went GT, Ribeiro RM, Perelson AS. 2008. Modeling amantadine treatment of influenza A virus in vitro. J. Theor. Biol. 254:439–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mitchell H, Levin D, Forrest S, Beauchemin CA, Tipper J, Knight J, Donart N, Layton RC, Pyles J, Gao P, Harrod KS, Perelson AS, Koster F. 2011. Higher level of replication efficiency of 2009 (H1N1) pandemic influenza virus than those of seasonal and avian strains: kinetics from epithelial cell culture and computational modeling. J. Virol. 85:1125–1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Möhler L, Flockerzi D, Sann H, Reichl U. 2005. Mathematical model of influenza A virus production in large-scale microcarrier culture. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 90:46–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schulze-Horsel J, Schulze M, Agalaridis G, Genzel Y, Reichl U. 2009. Infection dynamics and virus-induced apoptosis in cell culture-based influenza vaccine production—Flow cytometry and mathematical modeling. Vaccine 27:2712–2722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eigen M, Biebricher CK, Gebinoga M, Gardiner WC. 1991. The hypercycle. Coupling of RNA and protein biosynthesis in the infection cycle of an RNA bacteriophage. Biochemistry 30:11005–11018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krakauer DC, Komarova NL. 2003. Levels of selection in positive-strand virus dynamics. J. Evol. Biol. 16:64–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Regoes RR, Crotty S, Antia R, Tanaka MM. 2005. Optimal replication of poliovirus within cells. Am. Nat. 165:364–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yamayoshi S, Yamashita Y, Li J, Hanagata N, Minowa T, Takemura T, Koike S. 2009. Scavenger receptor B2 is a cellular receptor for enterovirus 71. Nat. Med. 15:798–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cardosa MJ, Perera D, Brown BA, Cheon D, Chan HM, Chan KP, Cho H, McMinn P. 2003. Molecular epidemiology of human enterovirus 71 strains and recent outbreaks in the Asia-Pacific region: comparative analysis of the VP1 and VP4 genes. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:461–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Komatsu H, Shimizu Y, Takeuchi Y, Ishiko H, Takada H. 1999. Outbreak of severe neurologic involvement associated with enterovirus 71 infection. Pediatr. Neurol. 20:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shimizu H, Utama A, Yoshii K, Yoshida H, Yoneyama T, Sinniah M, Yusof MA, Okuno Y, Okabe N, Shih SR, Chen HY, Wang GR, Kao CL, Chang KS, Miyamura T, Hagiwara A. 1999. Enterovirus 71 from fatal and nonfatal cases of hand, foot and mouth disease epidemics in Malaysia, Japan and Taiwan in 1997-1998. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 52:12–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shimizu H, Utama A, Onnimala N, Li C, Li-Bi Z, Yu-Jie M, Pongsuwanna Y, Miyamura T. 2004. Molecular epidemiology of enterovirus 71 infection in the western Pacific region. Pediatr. Int. 46:231–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nagata N, Shimizu H, Ami Y, Tano Y, Harashima A, Suzaki Y, Sato Y, Miyamura T, Sata T, Iwasaki T. 2002. Pyramidal and extrapyramidal involvement in experimental infection of cynomolgus monkeys with enterovirus 71. J. Med. Virol. 67:207–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nishimura Y, Shimojima M, Tano Y, Miyamura T, Wakita T, Shimizu H. 2009. Human P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is a functional receptor for enterovirus 71. Nat. Med. 15:794–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization 2004. Polio laboratory manual, 4th ed WHO Document Production Services, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moscufo N, Chow M. 1992. Myristate-protein interactions in poliovirus: interactions of VP4 threonine 28 contribute to the structural conformation of assembly intermediates and the stability of assembled virions. J. Virol. 66:6849–6857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Simons J, Rogove A, Moscufo N, Reynolds C, Chow M. 1993. Efficient analysis of nonviable poliovirus capsid mutants. J. Virol. 67:1734–1738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nowak MA, May RM. 2000. Virus dynamics: the mathematical foundations of immunology and virology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 27. Perelson AS. 2002. Modelling viral and immune system dynamics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:28–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chu PY, Lin KH, Hwang KP, Chou LC, Wang CF, Shih SR, Wang JR, Shimada Y, Ishiko H. 2001. Molecular epidemiology of enterovirus 71 in Taiwan. Arch. Virol. 146:589–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]