Abstract

During cellular invasion, human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) must transfer its viral genome (vDNA) across the endosomal membrane prior to its accumulation at nuclear PML bodies for the establishment of infection. After cellular uptake, the capsid likely undergoes pH-dependent disassembly within the endo-/lysosomal compartment, thereby exposing hidden domains in L2 that facilitate membrane penetration of L2/vDNA complexes. In an effort to identify regions of L2 that might physically interact with membranes, we have subjected the L2 sequence to multiple transmembrane (TM) domain prediction algorithms. Here, we describe a conserved TM domain within L2 (residues 45 to 67) and investigate its role in HPV16 infection. In vitro, the predicted TM domain adopts an alpha-helical structure in lipid environments and can function as a real TM domain, although not as efficiently as the bona fide TM domain of PDGFR. An L2 double point mutant renders the TM domain nonfunctional and blocks HPV16 infection by preventing endosomal translocation of vDNA. The TM domain contains three highly conserved GxxxG motifs. These motifs can facilitate homotypic and heterotypic interactions between TM helices, activities that may be important for vDNA translocation. Disruption of some of these GxxxG motifs resulted in noninfectious viruses, indicating a critical role in infection. Using a ToxR-based homo-oligomerization assay, we show a propensity for this TM domain to self-associate in a GxxxG-dependent manner. These data suggest an important role for the self-associating L2 TM domain and the conserved GxxxG motifs in the transfer of vDNA across the endo-/lysosomal membrane.

INTRODUCTION

All nonenveloped viruses are faced with a cellular membrane barrier through which they must transfer their genetic material to establish a successful infection. These viruses behave as metastable particles, rigid enough to survive transmission through the extracellular milieu but structurally poised to undergo conformational rearrangements or partial disassembly upon encountering specific factors during cellular entry, including the engagement of host cell receptors, proteolytic and chaperone activity, and low pH of the intracellular endosomal compartment. In response to these factors, capsids rearrange to expose hidden and often hydrophobic membrane translocation domains (MTDs), thereby ensuring that the coordinated process of membrane penetration occurs only when the viral capsid has reached the appropriate intracellular locale. Through convergent evolution, viruses have become equipped with a variety of different MTDs, designed to accomplish the feat of membrane penetration in several ways (recently reviewed in reference 1). Amphipathic helices, myristoylated and/or hydrophobic peptides, and phospholipase activity have all been documented to facilitate membrane penetration through pore formation, local membrane disruption, or gross fragmentation of membranes although many molecular details of these MTD-driven activities remain obscure and are ongoing subjects of investigation.

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) infect basal keratinocytes and replicate in differentiating cutaneous and mucosal epithelium. Persistent infections by certain high-risk types within the genus Alphapapillomavirus are associated with cervical, anogenital, and oropharyngeal cancers. Of the high-risk types, HPV type 16 (HPV16) is alone responsible for over half of the cases of cervical cancer worldwide (2, 3). Despite the long-established association between high-risk HPV infection and cancer, only now are the molecular mechanisms of cellular infection becoming well characterized.

Structurally, HPVs are relatively simple: 72 pentamers of the major coat protein L1 spontaneously assemble into a 55-nm-diameter, T=7d icosahedral lattice (4). Packaged within the L1 capsid is one copy of the 8-kb circular double-stranded (dsDNA) genome (viral DNA [vDNA]), chromatinized with cellular histones and associated with the minor capsid protein L2, although the nature of this vDNA/L2 complex remains obscure. The L2 protein can be present at variable copy numbers, with a maximum stoichiometry of 72 molecules per virion (5). Typical laboratory-generated preparations contain about one-third to one-half occupancy, or ∼24 to 36 molecules/virion (5, 6). L2 is a multifunctional protein, with auxiliary roles in virion assembly, stability, and vDNA encapsidation and an essential role in the endosomal translocation of vDNA during cellular invasion (7–10).

Despite its simple structure, HPV16 has a remarkably complex and protracted binding and entry pathway involving interactions with multiple cell surface and extracellular matrix (ECM) receptors, likely entailing conformational changes in virion structure. A thorough understanding of HPV16 receptor binding has been complicated by observed differences between in vitro cell culture systems and in vivo studies in the murine genital tract (11). Primary attachment of HPV16 occurs via heparin sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) present on the keratinocyte surface (in vitro) or basement membrane (in vivo). HSPG binding is believed to trigger a conformational change resulting in surface exposure of the N-terminal 9RTKR12 furin cleavage site in L2 and subsequent transfer of the capsid to an as of yet unidentified entry receptor (11, 12). Processing of L2 by cell surface furin is believed to trigger exposure of a neutralizing B-cell epitope, the RG-1 epitope, consisting of residues 17 to 36 of L2 (13, 14). There is also evidence that cell surface cyclophilin B may augment RG-1 epitope exposure through isomerization of a specific proline residue in L2 (15). Inhibition of furin cleavage of L2 and the subsequent exposure of the RG-1 epitope does not prevent viral entry into endosomal pathways but does inhibit the endosomal translocation of the vDNA/L2 complex further down the pathway of cell invasion (16).

Definitive characterization of the HPV16 entry mechanism has been elusive and remains a provocative topic of debate. A recent detailed analysis of HPV16 entry suggests that virions are taken up through a novel clathrin-, caveolin-, lipid raft-, and dynamin-2-independent endocytic pathway with some similarities to macropinocytosis (17). This entry pathway was dependent on actin dynamics, the Na+/H+ exchanger, and signaling through a variety of kinase pathways, including receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase, protein kinase C, and p21-activated kinases. Another recent study suggests that HPV16 can enter basal keratinocytes through an HSPG-dependent “Trojan horse” mechanism. HSPG-bound HPV16 can be released from the cell surface by matrix metalloproteases, heparinases, and other sheddase activities, liberating soluble HPV16-HSPG-growth factor (GF) complexes that can likely enter cells through cognate GF receptor-dependent endocytic mechanisms involving RTK and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling pathways (18). Regardless of the mode of entry, HPV16 appears to be sorted into an endosomal compartment whereby acidification facilitates capsid uncoating (19, 20), and the virus encounters the necessary signals that trigger endosomal translocation of the vDNA/L2 complex.

It is well recognized that L2 facilitates the endosomal translocation of vDNA. Previous efforts focused on L2 membrane penetration activity have identified and implicated a membrane destabilization peptide located toward the C terminus of L2 and consisting of residues 451SYYMLRKRRKRLPY464, with sequence similarity to the synthetic peptide dhvar5, a cationic membrane-lytic peptide derived from the antimicrobial polypeptide histatin-5 (10, 21). It was shown that a synthetic peptide corresponding to this sequence of L2 was cytotoxic, possessing membrane disruption activity, and that mutations or deletions within this C-terminal region abrogated viral infectivity, with the blockage occurring at the stage of endosomal vDNA translocation (10). While these findings do provide evidence for the involvement of this C-terminal peptide, it becomes difficult to draw firm conclusions regarding endosomal escape because this same region of L2 complexes with vDNA via the positively charged residues (22, 23) and also interacts with the dynein complex to facilitate cytoplasmic transport of the L2/vDNA complex toward the nucleus (24, 25).

To further explore the nature of L2-mediated translocation of vDNA across the endocytic membrane, we initiated a sequence-based search to identify regions and motifs, including amphipathic helices, hydrophobic peptides, and transmembrane (TM) domains that may directly interact with membranes. Herein we describe a conserved TM-like domain, containing GxxxG motifs, within the L2 minor capsid protein of HPV16 that is essential for translocation of the vDNA across the endosomal membrane. By virtue of their arrangement within an alpha helix, GxxxG motifs and similar “glycine zippers” (GxxxGxxxG) form a glycine patch positioned on one face of the helix, allowing the close right-handed packing of neighboring TM helices in a lipid bilayer (26, 27). Small residues like alanine and serine can sometimes substitute for glycines in these motifs and still aid in helix packing (28, 29). GxxxG and related motifs are known to support homo- and heterotypic association of TM helices and are present in a wide variety of single-pass and polytopic membrane proteins, channels, and pores (26, 27, 30–32). Using viral mutagenesis and a ToxR-based dimerization assay (33, 34), we show that while one particular GxxxG motif promotes TM domain self-association, the other conserved GxxxG motifs are also essential for HPV16 infection. These findings imply a potential mode for L2 homo- and heterotypic interactions and suggest that association into higher-ordered structures may be necessary for translocation of vDNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

TM prediction and modeling.

The HPV16 L2 primary sequence (GenBank accession number ACL12316) was submitted to web-based amphipathic and transmembrane helix prediction algorithms (35–43). For prediction results and references, see Table 1. L2 amino acids 45 to 67 were modeled as an alpha helix with surface rendering using the MacPyMOL software package. TM sequence alignments were done using the ClustalW tool within the MacVector software package.

Table 1.

Sequence prediction algorithms

| Algorithm | Sequence typea | Residue no | Sequenceb | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMHMM2 | TM | 45–67 | ILQYGSMGVFFGGLGIGTGSGTG | 38 |

| TM Pred (out-in) | TM | 49–67 | GSMGVFFGGLGIGTGSGTG | 36 |

| TM Pred (in-out) | TM | 45–63 | ILQYGSMGVFFGGLGIGTG | 36 |

| PRED-TMR | TM | 45–65 | ILQYGSMGVFFGGLGIGTGSG | 40 |

| HMMTOP | TM | 45–62 | ILQYGSMGVFFGGLGIGT | 43 |

| MemBrain | TM | 48–59 | YGSMGVFFGGLG | 42 |

| DAS | TM | 51–61 | MGVFFGGLGIG | 35 |

| MEMSAT | TM | 45–61 | ILQYGSMGVFFGGLGIG | 37 |

| TMKink | TM | 48–66 | YGSMG^VFF^G^G^LGIGT^GSGT | 39 |

| Amphipa-seek | APH | NAc | NA | 41 |

TM, transmembrane; APH, amphipathic helix.

^, Predicted kink.

NA, not applicable.

Cells and viruses.

293TT, HeLa, and HaCaT cells were maintained as previously described (44). Cloning of mutant viruses was achieved by site-directed mutagenesis of the L1/L2 expression plasmid pXULL using a QuikChange-XL II system (catalog number 200521; Agilent), and all mutant plasmids were verified by Sanger sequencing. Virions containing a luciferase expression plasmid (pGL3-basic; Clontech) were produced by CaPO4 transfection of 293TT cells. Purification was achieved by CsCl density gradient centrifugation as previously described (6). Purified virions were assayed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining and compared against bovine serum albumin (BSA) standards. Genome content was determined by SYBR green quantitative PCR (qPCR) using primers specific for the luciferase gene of pGL3, and capsid/genome ratios were all in the ranges typical for wild-type (wt) HPV16 preps. All other transfections were performed with Turbofect reagent (R0531; Fermentas), according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Infections.

HaCaT cells were seeded in a 24-well plate with 60,000 cells/well and infected with HPV16 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1,000 to 2,000 genomes/cell for an overnight continuous infection. At 48 h postinfection the cells were lysed in 0.1 ml of 1× reporter lysis buffer (E3971; Promega). Luciferase levels were measured with a DTX-800 multimode plate reader (Beckman Coulter) by firefly luciferase assay according to the manufacturer's recommendations (E4550; Promega).

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Samples were diluted into denaturing/reducing SDS-PAGE loading buffer (62.5 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.5% bromophenol blue, 5% 2-β-mercaptoethanol) and incubated for 5 min at 95°C. Samples were run on a 10% Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gel, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, and blocked in Tris-buffered saline–Tween (TBST) plus 4% milk, 4% BSA, and 1% goat serum. Mouse anti-hemagglutinin (HA) (G036; Applied Biological Materials), rabbit anti-maltose-binding protein (MBP) (E8030S; New England BioLabs [NEB]), and rabbit anti-L2 antiserum (DK43811; a kind gift from R. Roden) were used at 1:5,000. Goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (ab6789 and ab6721, respectively; Abcam) were used at 1:10,000. Supersignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (34080; Pierce) was used.

EdU labeling and detection.

HPV virions containing 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU)-labeled pGL3-basic DNA were produced by CaPO4 transfection of 293TT cells supplemented with 15 μM EdU (44). HaCat cells were seeded on glass coverslips and infected with EdU-labeled viruses at 500 ng of L1/ml for 18 h. The cells were then washed once using fresh medium to remove unbound virions, medium was replaced with fresh medium, and cells were cultured for an additional 24 h. At 42 h postinfection, cells were chilled to 4°C, washed three times in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed in acetone at −20°C for 5 min. Cells were blocked overnight in PBS–4% BSA and 1% goat serum at 4°C. EdU-labeled vDNA was then conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488-N3 by CuSO4-catalyzed click chemistry (C10337; Invitrogen). Standard immunofluorescence was then performed as described below.

Immunofluorescence.

All immunostained samples except those containing EdU-labeled vDNA and those used in the TM functionality assay were fixed with PBS–2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature (RT) and then permeabilized with PBS–0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min at room temperature. Samples were then blocked in PBS–4% BSA and 1% goat serum prior to immunostaining. Cells in the TM functionality assay were treated in the same way, except that they were not permeabilized. The rabbit anti-L1 polyclonal antibody K75 and mouse anti-L1 monoclonal antibody L1-7 (kind gifts of M. Sapp) were used at 1:5,000 and 1:100, respectively. Rabbit anti-PML polyclonal antibody (ab53773; Abcam) was used at 1:300. Mouse anti-HA antibody (G036; Applied Biological Materials) was used at 1:2,000. Alexa Fluor-488, -555, and -633 goat anti-mouse/rabbit secondary antibodies (A21052; Molecular Probes) were all used at 1:1,000. Coverslips were mounted on slides in Prolong Gold Antifade medium containing 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (P36931; Molecular Probes).

Confocal microscopy.

Specimens were examined on a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted microscope with a 63×objective. Confocal microscopy was performed with a Zeiss LSM 510 META system using a 405-nm laser diode and 488-nm argon laser, 543-nm He/Ne1 laser, and 633-nm He/Ne2 laser excitations. Select single-plane images (depth of 0.25 μm) were processed with Adobe Photoshop and Microsoft PowerPoint software.

ToxLuc assay.

For the ToxLuc assay, control and experimental TM domains were cloned into the pTL backbone (kind gift of P. Hubert) as annealed oligonucleotides with NheI and BamHI, resulting in the N-terminal flanking sequence ToxR…Arg-Ala-Ser and the C-terminal flanking sequence Ile-Leu-Ile-Asn…MBP. ToxLuc TM sequences are presented in Fig. 4B. To verify proper membrane insertion, each construct was spotted on an M9 agar plate supplemented with 0.4% maltose and incubated for 2 to 3 days at 37°C. For luciferase measurement, cells were grown to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] between 0.2 and 0.5), pelleted, and lysed in bacterial lysis buffer (100 mM K2HPO4 pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mg/ml BSA, 5 mg/ml lysozyme, 0.2% Benzonase) for 30 min at RT with occasional vortexing, followed by a −80°C freeze-thaw. The lysate was then clarified by centrifugation, and the supernatant was assayed for firefly luciferase. Luciferase activity was normalized using the OD600 values of the cell cultures measured before lysis. Western blotting with anti-MBP (E8030S; NEB) verified expression of the constructs.

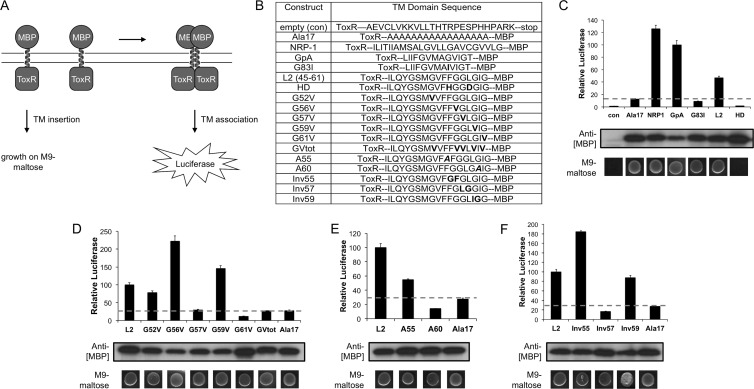

Fig 4.

L2 transmembrane self-association. (A) Schematic of the ToxLuc assay wherein a TM domain of interest is cloned and expressed as a ToxR-TM-MBP fusion in a malE strain of E. coli, complementing growth on M9-maltose medium upon proper membrane insertion. Dimerization of ToxR via TM interactions mediates luciferase expression. (B) Sequences for all the ToxLuc inserts. Substitutions are in bold, and insertions are in bold and italicized. (C, D, E, and F) ToxLuc experiments were performed with the following: the positive (NRP1 and GpA) and negative (A17, G83I, and con) controls and wt and HD versions of the L2 TM domain (C); the single glycine-to-valine point mutants and a combined mutant (GVtot) for each glycine involved in a GxxxG motif (D); the alanine insertion mutants (E); and the glycine inversion mutants (F). All ToxLuc constructs were tested for MBP expression by Western blotting and for insertion into E. coli inner membrane by plating on M9 medium-maltose plates.

L2 peptides.

Peptides were supplied by Pi Proteomics, LLC. The peptide comprised of L2 residues 45 to 61 (NH2-KKKILQYGSMGVFFGGLGIGKKK-acid) and the peptide comprised of L2 residues 45 to 67 (NH2-KKKILQYGSMGVFFGGLGIGTGSGTGKKK-acid), designed with three flanking lysine residues on both ends, were synthesized by solid-phase 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry and purified to >90% as determined by analytical high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Peptides were verified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry. Peptide aliquots were dissolved in deionized H2O for circular dichroism (CD) experiments.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy.

Far-UV CD spectra were recorded from 195 nm to 260 nm using an Olis DSM-20 CD Spectrometer. Samples (300 μl) contained 40 μM peptide in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, with or without 30 mM SDS. A quartz cuvette with a 1-mm path length was used. Spectra were recorded in three sets of 260 nm to 220 nm, 220 nm to 205 nm, and 205 nm to 195 nm with integration times of 5 s, 30 s, and 60 s, respectively. Each spectrum was recorded three times, and results were averaged. All spectra were then background corrected against average spectra obtained for buffer/detergent alone, zeroed at 260 nm, converted to mean residue ellipticity (θ), and plotted using the GraphPad Prism software package.

RESULTS

The N terminus of L2 contains a predicted TM domain.

To gain further insight into how HPV16 L2 facilitates genome escape from the endosome, we searched for potential membrane-interacting sequences using various algorithms (Table 1). The TM prediction algorithm TMHMM2 (38) gave a fairly high probability for a TM domain near the N terminus of L2, consisting of residues 45 to 67 (Fig. 1A). Several different TM prediction algorithms also gave positive hits within the same region of L2 (Table 1). Compared to typical TM domains, the 23-residue sequence is only moderately hydrophobic and rich in glycine residues (Fig. 1B). The predicted TM domain lies just downstream of the epitope for the broadly cross-neutralizing antibody RG-1, comprised of residues 17 to 36 (14), containing the conserved disulfide bond between Cys22 and Cys28 that is involved in endosomal penetration of vDNA (6) (Fig. 1B). The RG-1 epitope is not exposed until after furin cleavage of L2 at Arg12 prior to cell entry (13). It is therefore possible that the predicted TM domain is also not exposed until after furin cleavage although this region has been previously described as being surface exposed, and a monoclonal antibody against an overlapping epitope (residues 56 to 75) blocked infection, albeit neutralization required a high concentration of antibody (45, 46).

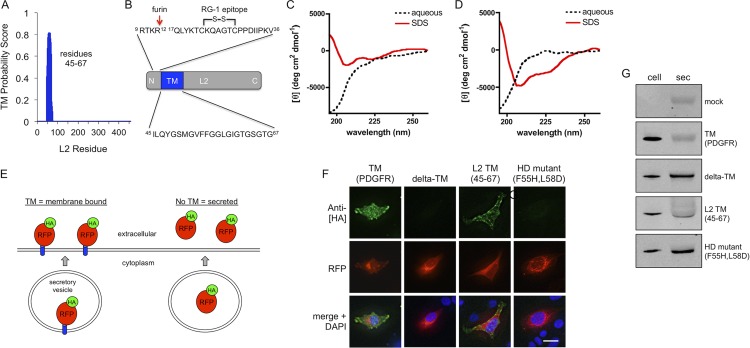

Fig 1.

The predicted TM domain in L2 is functional. (A) Scanning of L2 with the TMHMM2 transmembrane prediction algorithm gave a very high probability of a TM domain near the N terminus of L2 (residues 45 to 67). (B) Position of the TM domain relative to the furin cleavage site and the epitope for the cross-neutralizing antibody RG-1, which contains the conserved disulfide bond between Cys22 and Cys28. Results of CD spectroscopy of the long (residues 45 to 67) (C) and short (residues 45 to 61) (D) TM peptides in aqueous and SDS environments are shown. (E) Schematic of TM functionality assay, wherein a functional TM domain will tether HA-tagged RFP to the cell surface while a nonfunctional TM domain will result in secretion of the fusion protein. (F) HeLa cells were transfected with plasmid constructs expressing TM domains of interest fused to the C terminus of HA-tagged RFP with a secretory leader. Surface staining with anti-HA (green) is indicative of membrane insertion; RFP expression (red) is a marker for transfection. Scale bar, 20 μm. (G) Anti-HA Western blots of secreted (sec) and cell lysate fractions from transfected cells.

To gain structural insight into the nature of this region of L2, we synthesized peptides corresponding to residues 45 to 67 and 45 to 61, both of which were predicted to be TM domains by separate prediction algorithms (Table 1), and performed circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy in both aqueous and hydrophobic environments. Peptides were flanked with three lysine residues on both termini to aid in solubility. CD spectroscopy indicated that both peptides adopt a random-coil conformation in aqueous buffer but exhibit the 208-nm/222-nm double minima characteristic of alpha-helical structure in the hydrophobic membrane-mimetic environment of SDS micelles (47), albeit the long peptide at residues 45 to 67 had a less pronounced spectral shift in SDS micelles than the short peptide at residues 45 to 61 (Fig. 1C and D). The data are consistent with this region potentially functioning as an alpha-helical TM domain in lipid bilayers.

The predicted TM domain is functional.

To determine if the predicted TM can actually function as a TM domain in a cellular system, we cloned a TM reporter plasmid that fuses secreted HA-tagged red fluorescent protein (RFP) to a TM domain of interest (Fig. 1E). In this assay a functional TM domain will tether the fusion protein to the plasma membrane, with the HA tag exposed on the surface of the cell. A nonfunctional TM domain will result in secretion of the fusion protein into the extracellular medium (Fig. 1E). We cloned the TM domain of platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) as a positive control and used a construct lacking a TM domain (delta-TM) as a negative control. Residues 45 to 67 of the L2 TM domain were cloned, as well as a double point mutant (F55H L58D) of the L2 sequence that is predicted to abolish the TM functionality, according to TMHMM2 (Table 2). This mutant is here referred to as HD. Surface anti-HA staining of fixed, nonpermeabilized transfected cells showed that the L2 TM domain is functional, tethering the reporter fusion to the cell surface, similar to the PDGFR TM domain although to a lesser extent (Fig. 1F). The HD mutation destroyed the TM functionality, resulting in no surface HA staining, similar to the delta-TM negative control (Fig. 1D). Pronounced secretion of the fusion protein into the extracellular medium was observed only in constructs that lacked a functional TM domain, i.e., the delta-TM and HD mutants. The PDGFR TM construct had no detectable secretion while the L2 construct had an intermediate phenotype, with lower levels of secretion than either the HD or delta-TM constructs. Thus, it appears that although the region of residues 45 to 67 of L2 can tether proteins to the cell membrane, it does not function as well as a bona fide TM, like that from PDGFR. Again, the combination of the moderate TMHMM score (Fig. 1A), the CD data (Fig. 1C), and the TM reporter assay (Fig. 1F and G) implies that the region of residues 45 to 67 of L2 is an inefficient, although still functional, TM domain.

Table 2.

HPV TM mutant sequences

| HPV16 type or mutant | TM sequence (residues 45–67)a | TM scoreb | TM functionc |

|---|---|---|---|

| wt | ILQYGSMGVFFGGLGIGTGSGTG | 0.825 | Yes |

| HD | ILQYGSMGVFHGGDGIGTGSGTG | 0.004 | No |

| A55 | ILQYGSMGVFAFGGLGIGTGSGTG | 0.885 | Yes |

| A60 | ILQYGSMGVFFGGLGAIGTGSGTG | 0.888 | Yes |

| A64 | ILQYGSMGVFFGGLGIGTGASGTG | 0.889 | ND |

| G52V | ILQYGSMVVFFGGLGIGTGSGTG | 0.924 | Yes |

| G56V | ILQYGSMGVFFVGLGIGTGSGTG | 0.922 | Yes |

| G57V | ILQYGSMGVFFGVLGIGTGSGTG | 0.921 | Yes |

| G59V | ILQYGSMGVFFGGLVIGTGSGTG | 0.921 | Yes |

| G61V | ILQYGSMGVFFGGLGIVTGSGTG | 0.920 | Yes |

| G63V | ILQYGSMGVFFGGLGIGTVSGTG | 0.915 | ND |

| Inv55 | ILQYGSMGVFGFGLGIGTGSGTG | 0.821 | Yes |

| Inv57 | ILQYGSMGVFFGLGGIGTGSGTG | 0.825 | Yes |

| Inv59 | ILQYGSMGVFFGGLIGGTGSGTG | 0.825 | Yes |

Mutated residues are shown in boldface. The A55, A60, and A64 insertion mutations (bold and italicized) were designed to disrupt the GxxxG motifs without compromising TM functionality.

Maximum TM probability score with TMHMM2 algorithm.

Assessed by cell surface HA-RFP experiment and/or maltose complementation in ToxLuc. ND, not determined.

The TM domain is essential for HPV16 infection.

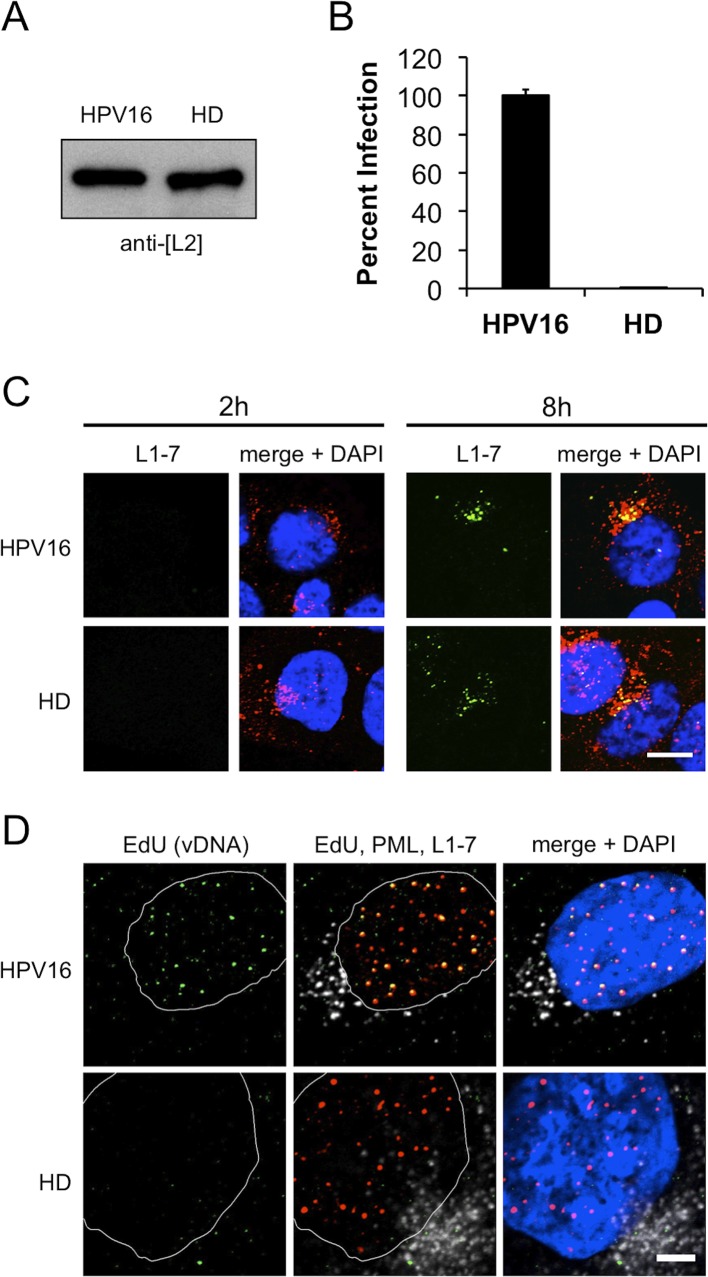

To determine if L2 TM functionality is necessary for successful infection, we generated wt and HD mutant luciferase-expressing HPV16 virions. The HD mutation did not affect viral assembly, morphology, overall yield, genome packaging, or L2 encapsidation (Fig. 2A; also data not shown). HD mutant virus was completely noninfectious, strongly suggesting that the functional TM domain of L2 is essential for infectivity (Fig. 2B). The HD mutation had no obvious effect on virion binding, entry, or time-dependent exposure of the buried L1-7 epitope, a marker for uncoating (44, 48) (Fig. 2C). Next, the viral genome was labeled with the thymidine analog EdU, allowing direct visualization of incoming vDNA in immunofluorescence experiments (44, 45, 49). Infection with wt HPV16 resulted in strong colocalization of EdU-labeled vDNA and nuclear PML bodies at late times postinfection (Fig. 2D). Unlike wt HPV16, the HD mutant was completely defective for vDNA localization at PML bodies, despite similar levels of invasion and uncoating as seen by L1-7 staining (Fig. 2C and D). These data suggest that HD mutant vDNA fails to escape the endo-/lysosomal compartment, further supporting a role for the TM domain in translocation of the L2/vDNA complex.

Fig 2.

The TM domain is essential for infection. (A) Anti-L2 blot of purified wt and HD mutant virions. (B) Infectivity of wt and HD virions on HaCaT cells. (C) HaCaT cells were infected with wt or HD virions for the indicated times prior to fixation and immunostaining. L1 was stained with rabbit polyclonal K75 (red) and mouse monoclonal L1-7 (green). (D) HaCaT cells were infected for 42 h with wt or HD virions containing EdU-labeled vDNA, fixed, and processed. EdU-labeled vDNA was stained with Alexa Fluor 488-azide (green), PML bodies were stained with rabbit anti-PML (red), and uncoated L1 was stained with L1-7 (white). All nuclei were stained blue with DAPI. Scale bars, 10 μm (C) and 5 μm (D).

The TM domain contains conserved GxxxG motifs that are essential for infection.

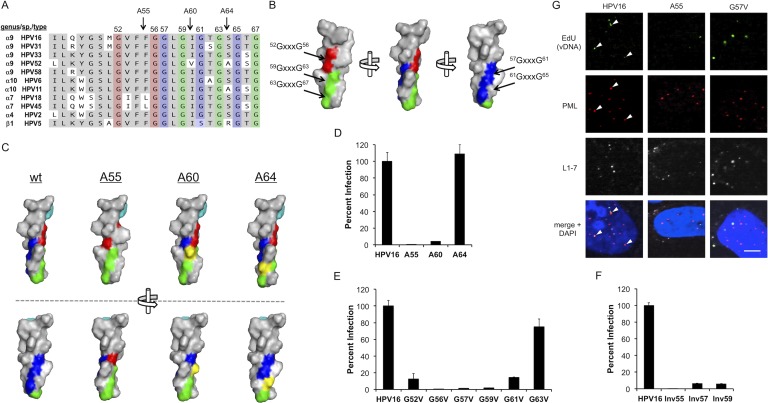

This TM domain of L2 is highly conserved among both low- and high-risk mucosal alphapapillomaviruses as well as other genera of the family Papillomaviridae (Fig. 3A). Upon further inspection of the primary sequence, we discovered that it contains three highly conserved GxxxG motifs, a single 52GxxxG56 motif and two overlapping tandem 57GxxxG61xxxG65 and 59GxxxG63xxxG67 motifs, highlighted in red, blue, and green, respectively, in Fig. 3A. GxxxG motifs are known to mediate the homo- and heterotypic interactions between TM domains of single-pass and polytopic membrane proteins, channels, transporters, and pore structures (26, 31, 50, 51). Modeling of the L2 TM domain as an alpha helix reveals that the GxxxG motifs lie on two opposing faces of the helix, with the 52GxxxG56 (red) and 59GxxxG63xxxG67 (green) motifs forming a glycine patch on one side and the 57GxxxG61xxxG65 (blue) motif positioned on the other side (Fig. 3B). To test the importance of these GxxxG motifs in HPV16 infection, we first designed three alanine insertion mutants of L2. The position of the alanine insertions for the A55, A60, and A64 mutants are designated by arrows in Fig. 3A. These mutations were designed to disrupt the GxxxG motifs without compromising TM functionality (Fig. 3A and Table 2). Molecular modeling illustrates that the insertions not only directly disrupt the single GxxxG motif into which the alanine is placed but also rotate all downstream GxxxG motifs out of alignment by 100° relative to the N terminus of the helix (Fig. 3C). A55 is predicted to be the most deleterious mutation, disturbing all the TM domain GxxxG motifs. A60 preserves the 52GxxxG56 motif but disrupts all downstream motifs, and A64 disrupts only the C-terminal 61GxxxG65 and 63GxxxG67 motifs. The A55 mutant was completely noninfectious, the A60 mutant had drastically reduced infectivity, and the A64 mutant had no reduction in infectivity (Fig. 3D). The severely reduced infectivity of A55 and A60 combined with the unaltered infectivity of A64 strongly suggests that only the N-terminal 52GxxxG56, 57GxxxG61, and 59GxxxG63 motifs are essential for infection.

Fig 3.

Conserved GxxxG motifs are essential for infection. (A) Sequence alignment highlighting the conserved GxxxG motifs within the TM domain. The 52GxxxG56 motif is outlined in red, the 57GxxxG61xxxG65 is in blue, and the 59GxxxG63xxxG67 motif is in green. Positions of the alanine insertion mutants A55, A60, and A64 are depicted with arrows. (B) Alpha-helical modeling of the TM domain shows that the three GxxxG motifs lie on two opposite faces of the helix. (C) Modeling of wild-type and alanine insertion mutant helices. Two orientations are shown, rotated roughly 90° relative to each other. GxxxG motifs are colored as depicted in panel B, and inserted alanine residues are shown in yellow. Tyr48 is represented in cyan for reference. Insertion of alanines within a GxxxG motif causes direct disruption of the GxxxG and shifts downstream residues 100° relative to the N terminus. (D) The relative infectivity of the alanine insertion mutants compared to wt HPV16. (E) Infectivity of the glycine-to-valine point mutants. (F) Infectivity of the glycine inversion mutants. (G) Effects of the A55 and G57V mutations on vDNA-PML colocalization. EdU-labeled vDNA was stained with Alexa Fluor 488-azide (green), PML bodies were stained with rabbit anti-PML (red), and uncoated L1 was stained with L1-7 (white). Arrowheads indicate vDNA colocalization with PML. All nuclei were stained blue with DAPI. Scale bar, 5 μm.

To further verify a role for these N-terminal GxxxG motifs in HPV16 infection, individual glycine-to-valine mutant viruses were generated and tested. Infection experiments revealed the importance of Gly52, Gly56, Gly57, Gly59, and Gly61 (Fig. 3E), arguing that multiple GxxxG motifs contribute to L2's function during infection. Notably, the G63V mutant was only mildly impaired, supporting our observations with the A64 mutant (Fig. 3C) and suggesting that the two N-terminal 52GxxxG56 and 57GxxxG61 motifs are important and that only Gly59 of the 59GxxxG63 motif is critical. Three inversion mutants, Inv55, Inv57, and Inv59, were also generated whereby select glycine residues were switched in position with neighboring amino acids (Table 2). The inversion mutants disrupt GxxxG motifs by altering the primary sequence of the TM domain without affecting the chemical composition or hydrophobicity of the region. Infectivity experiments again reveal an important role for the two N-terminal 52GxxxG56 and 57GxxxG61 motifs as well as Gly59 in HPV16 infection (Fig. 3F). Similar to the HD mutant, the A55 and G57V mutant viruses were normal in respect to entry and uncoating, as seen by L1-7 staining, but defective in PML localization of EdU-labeled vDNA, suggesting a role for these GxxxG motifs in endosomal translocation of vDNA (Fig. 3G).

The L2 TM domain can self-associate in a biological membrane.

The functional importance of the N-terminal GxxxG motifs in HPV16 infection prompted us to determine if these motifs are involved in homodimerization or oligomerization of the TM domain using a modified version of the ToxCAT assay called ToxLuc (33, 34). This assay works by expressing a TM domain of interest as a ToxR-TM-MBP (maltose binding protein; MalE) fusion in strain NT326, a malE mutant strain of E. coli. Proper membrane insertion of the fusion is readily determined by malE complementation of NT326 and restoration of growth on M9 medium containing maltose as the sole carbon source, as this requires the MBP moiety to be positioned toward the periplasmic space. ToxR is a dimerization-dependent transcriptional activator, and TM-driven self-association of the ToxR-TM-MBP fusion results in the activation of luciferase expression from the ToxR-dependent ctx promoter. Growth on M9 medium-maltose is therefore an indicator of TM functionality while luciferase activity is a gauge of TM dependent self-association within a cellular membrane (Fig. 4A). Notably, this assay gives a relative propensity for TM self-association but cannot distinguish between dimerization and higher-order oligomerization or multimerization of the TM domain (52). All TM domain sequences assayed with the ToxLuc system are shown in Fig. 4B.

The TM domains from glycophorin A (GpA) and NRP1 are known to homodimerize through GxxxG motifs (33, 34) and were used as positive controls for the ToxLuc assay, resulting in strong activation of luciferase activity (Fig. 4C). A previously characterized GxxxG mutant of GpA, G83I (53), served as a negative control for self-association and resulted in about 10-fold less luciferase activity than the wt GpA TM construct (Fig. 4C). A 17-residue polyalanine stretch (Ala17) was used as a baseline TM control for nonspecific ToxR-dependent luciferase activation due to molecular crowding and transient interactions of the ToxR-TM-MBP fusion when expressed in the limited space of the bacterial membrane (54). The Ala17 construct, like G83I, yielded baseline levels of luciferase, typically 10-fold less than those of GpA and NRP1 (Fig. 4B). An empty control containing a stop codon after the ToxR domain (Fig. 4B) resulted in essentially no luciferase activity, demonstrating that there is an inherent baseline activity (as seen in Ala17 and G83I) dependent on expression of a membrane-tethered ToxR domain. Relative ToxR-TM-MBP expression levels were gauged by anti-MBP Western blotting of cell lysates (Fig. 4C), and luciferase levels were normalized to cell density. All control TM constructs with the exception of the empty control had functional TM domains and could grow on M9 medium-maltose (Fig. 4C).

The full-length predicted TM domain from L2 (residues 45 to 67) was cloned into the ToxLuc construct but was not tolerated as a TM domain and could not support growth of NT326 on M9 medium-maltose despite numerous attempts and adjustments of length and linker sequence. The truncated form of the TM domain (residues 45 to 61) was readily tolerated, and we therefore used this shortened version for all ToxLuc experiments. Importantly, the TM domain consisting of residues 45 to 61 was actually predicted by some of the TM algorithms (Table 1) and contains the important N-terminal GxxxG motifs identified in the alanine insertion and glycine substitution experiments. The TM domain consisting of residues 45 to 61 yielded intermediate levels of luciferase activation, which were 2-fold lower than the level of the GpA control but well above that of the Ala17 baseline control (Fig. 4C). These levels are on par with previously characterized dimeric and multimeric self-associating TM domains from a variety of membrane proteins (50, 55, 56). The HD mutant version of the TM domain consisting of residues 45 to 61 gave luciferase levels comparable to the level of the empty control and failed to support growth of NT326 on M9 medium-maltose, again demonstrating that the HD mutation is a complete knockout of TM functionality (Fig. 4C).

A specific GxxxG motif in L2 facilitates TM self-association.

Glycine-to-valine point mutants were constructed for all single and combined GxxxG motif glycines to determine the motif(s) responsible for TM self-association. Only the G57V and G61V single mutants yielded baseline luciferase activation, strongly suggesting that the 57GxxxG61 motif mediates self-association of the TM domain (Fig. 4D). The GV-total mutant (GVtot), where all the GxxxG motif glycines were mutated to valine, also resulted in baseline activation (Fig. 4D). Additional ToxLuc experiments on the A55 and A60 alanine insertion mutants confirm that the 57GxxxG61 motif is the only one necessary for TM self-association as only the A60 mutation, which directly disrupts the 57GxxxG61 motif, decreased luciferase activation under baseline levels (Fig. 4E). The A55 mutation, which caused a 45% decrease in luciferase activation, does not directly disrupt the 57GxxxG61 motif but throws it off register from the N terminus of the TM domain by 100° and also disrupts a conserved 54FxxG57xxxG61 motif that normally occurs in the TM domain (Fig. 3A), the phenylalanine of which has been shown to aid in GxxxG-driven TM dimerization (57). ToxLuc experiments with the inversion mutants again suggest that only the 57GxxxG61 motif is essential for TM self-association as Inv57 was the only mutant to abrogate luciferase activation (Fig. 4F).

DISCUSSION

Delivery of genetic material into the host cell is essential for viral infection, and the cellular membrane represents a major barrier which the nonenveloped viruses have evolved multiple ways to breach during infection (1, 58). Papillomaviruses depend on the minor capsid protein L2, present at low abundance, to accomplish this task. Here, we describe a conserved TM domain located toward the N terminus of L2 and show that this region is essential for endosomal penetration of the viral genome. Through extensive mutagenesis, we reveal that multiple GxxxG motifs within this TM domain are required for viral infectivity and that the 57GxxxG61 motif can facilitate self-association of this region within biological membranes. These data suggest a potential mechanism whereby multiple L2 molecules may participate in homo- and heterotypic interactions via their TM domain GxxxG motifs to form higher-order assemblies necessary for membrane translocation of vDNA. Previous studies by Kämper and colleagues have revealed a membrane-destabilizing peptide at the C-terminal end of L2 that also appears to be necessary for endosomal penetration of vDNA (10). We present our findings not to refute these previous conclusions but, rather, to offer an alternative or complementary model for the mechanism of L2-mediated vDNA translocation. Our conclusions and those of Kämper and colleagues are not mutually exclusive as cooperation between both regions of L2 may be required for vDNA penetration, and additional studies in our laboratory will further explore this possibility.

Several features of our TM-based model are conceptually attractive. First, there is already existing evidence for involvement of this region of L2 in vDNA penetration as a monoclonal antibody against residues 56 to 75, encompassing part of the TM domain, exhibits postentry neutralization activity by blocking this late stage of infection (45, 46). Second, the TM domain is in close proximity to the other N-terminal elements of L2 that are involved in vDNA translocation (Fig. 1B), notably the furin cleavage site at Arg12 (16) and the disulfide bond between Cys22 and Cys28 (6). Perturbation of either of these elements through genetic mutation or biochemical inhibition results in a failure of vDNA penetration. Following along thematic mechanisms commonly observed with nonenveloped viruses, furin cleavage and disulfide reduction may act as conformational switches, engagement of which could lead to exposure of the hydrophobic TM domain for interaction with endosomal membranes. In support of this notion, our group has recently found evidence that cellular protein disulfide isomerases may be supporting a reductase activity, necessary for vDNA translocation (44). The L2 disulfide bond seems like an obvious target for such a reductase activity, and efforts in this direction are ongoing in our laboratory.

A third attractive aspect of the TM domain concept is the existence of endocytic sorting motifs in L2. Recently, it has been shown that an interaction between a conserved 254NPxY257 motif in L2 and cellular sorting nexin 17 (SNX17) modulates residence and transport kinetics of HPV16 in the endo-/lysosomal compartment and is important for efficient vDNA penetration (49). SNX17 is a soluble factor that associates with the cytoplasmic face of phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate-containing membranes, including early and recycling endosomes, regulating the trafficking and sorting of various transmembrane cargos via their cytoplasmic NPxY motifs (59, 60). The presence of a functional TM domain provides a means by which L2 could physically span the endosomal membrane, interacting with cytoplasmic endosome-associated SNX17 to modulate HPV16 trafficking.

Lastly, the intramembrane protease complex, γ-secretase, has been shown to be absolutely critical for HPV infection (61). Biochemical inhibition of γ-secretase potently blocks HPV16 infection, again by preventing the endosomal translocation of vDNA. γ-Secretase cleaves transmembrane domain substrates, making the L2 TM domain an obvious candidate substrate for γ-secretase processing. Interestingly, over 25% of the known γ-secretase TM substrates contain GxxxG motifs (62), suggesting that these same motifs in L2 may participate in recruitment, recognition, or processing by γ-secretase. Notably, GxxxG motifs have been implicated in the homodimerization of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and regulation of APP cleavage by γ-secretase (63, 64), and the APP TM domain contains GxxxG motifs in a pattern similar to that of L2 (Table 3). Recent structural work on APP shows that it can exist as a kinked helix, with the bend occurring at Gly708 and Gly709, and the bent nature of this helix may contribute toward its binding by γ-secretase (65). Intriguingly, a TM kink algorithm (39) predicts a high propensity for helical kinks in the L2 TM domain between Gly52 and Thr62, with the highest probabilities at Phe55, Gly56, and Gly57 (Table 1).

Table 3.

Similarities among Gly/Ala-rich TM domains and viral fusion peptides

| Protein | Residue no. | Sequencea | Gly/Ala content (%) | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV16 L2 | 45–67 | ILQYGSMGVFFGGLGIGTGSGTG | 39.1 | ACL12316 |

| Human APP | 700–722 | GAIIGLMVGGVVIATVIVITLVM | 26.1 | NP_000475 |

| Influenza H1N1 virus HA | 344–366 | GLFGAIAGFIEGGWTGMVDGWYG | 43.5 | ABD59849 |

| Measles virus F protein | 116–138 | FAGVVLAGAALGVATAAQITAGI | 52.2 | ACC86104 |

| HIV gp160 | 510–532 | AVGIGAVFIGFLGAAGSTMGAAS | 52.2 | ACN69512 |

| Dengue virus Env | 96–118 | VVDRGWGNGCGLFGKGGVVTCAK | 34.8 | AEJ32009 |

All Gly/Ala residues are bolded, and those involved in potential (G/A)xxx(G/A) motifs are also underlined.

Our data suggesting an internal TM domain within L2 imply that this region must somehow interact with and integrate into the endosomal membrane to mediate vDNA translocation. How would such a TM domain spontaneously insert into the endosomal membrane? Interestingly, the TM sequence has remarkable similarities to the fusion peptides (FPs) of class I and class II fusion proteins from a variety of enveloped virus families, including the orthomyxoviruses, paramyxoviruses, retroviruses, and flaviviruses (Table 3). Although quite hydrophobic, these FPs are masked by other parts of the fusion protein until activation in response to stimuli (low pH, proteolysis, or receptor binding), whereby the FP inserts into target cellular membranes to mediate fusion (66). High glycine and/or alanine content is a hallmark of these FPs, and the conformational flexibility and backbone dynamics imparted by this Gly/Ala content are likely vital to membrane insertion and fusogenicity of the FPs (66, 67). Accordingly, structural studies on these viral fusion peptides reveal that while they can adopt kinked alpha-helical conformations in detergent and micelle environments (66–69), these membrane-embedded bent helices may straighten out to span the membrane bilayer as a continuous helix, self-associating into higher-order helical bundle structures, reminiscent of pores (70).

It is conceivable that the L2 TM domain could act in an analogous manner, with L2 monomers initially plunging their TM domains into the membrane as kinked hairpins, followed by a coordinated extension and association into higher-ordered pore-like structures via the conserved GxxxG motifs. It is possible that the inefficient nature of the L2 TM domain is important for infection as L2 may need to only transiently insert into the membrane to facilitate endosomal escape but then be able to untether itself from the membrane in order to traffic with the viral genome toward the nucleus. Much will be gained from future studies on the L2 TM domain and mechanisms of membrane insertion, self-association, interaction with cellular proteins, and translocation of vDNA. The identification of the TM domain and GxxxG motifs presented herein represents a significant conceptual advancement toward this end.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by American Cancer Society grant RSG 117469 (S.K.C.), Arizona Cancer Center grant CA023074 (S.K.C.), and a grant from the AZCC Better Than Ever Program (S.K.C.). M.P.B. was funded in part by a grant to the University of Arizona (UA) from HHMI (52006942) that supports the undergraduate biology research program (UBRP).

We gratefully acknowledge P. Hubert (Laboratoire d'Ingénierie des Systèmes Macromoléculaires, Marseille, France) for ToxLuc constructs, M. Sapp (LSU-HSC, Shreveport, LA) for L1-7 and K75 antibodies, R. Roden (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) for anti-L2 antisera, and C. Buck (NCI, Bethesda, MD) and M. Müller (DKFZ, Heidelberg, Germany) for HPV capsid plasmids. We thank C. Boswell and P. Jansma of the UA Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology Imaging Facility, D. Yoder of the BIO5 Media Facility, and Josef Vagner (UA BIO5) for help with peptide lyophilization, and we acknowledge the use of facilities at the analytical biophysics core in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of Arizona. We are gratefully indebted to M. Ozbun and her laboratory at the University of New Mexico, where early aspects of this work were pioneered.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 October 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Moyer CL, Nemerow GR. 2011. Viral weapons of membrane destruction: variable modes of membrane penetration by non-enveloped viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 1:44–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S. 2007. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet 370:890–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. zur Hausen H. 2002. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:342–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Modis Y, Trus BL, Harrison SC. 2002. Atomic model of the papillomavirus capsid. EMBO J. 21:4754–4762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buck CB, Cheng N, Thompson CD, Lowy DR, Steven AC, Schiller JT, Trus BL. 2008. Arrangement of L2 within the papillomavirus capsid. J. Virol. 82:5190–5197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Campos SK, Ozbun MA. 2009. Two highly conserved cysteine residues in HPV16 L2 form an intramolecular disulfide bond and are critical for infectivity in human keratinocytes. PLoS One 4:e4463 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Day PM, Roden RBS, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. 1998. The papillomavirus minor capsid protein, L2, induces localization of the major capsid protein, L1, and the viral transcription/replication protein, E2, to PML oncogenic domains. J. Virol. 72:142–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holmgren SC, Patterson NA, Ozbun MA, Lambert PF. 2005. The minor capsid protein L2 contributes to two steps in the human papillomavirus type 31 life cycle. J. Virol. 79:3938–3948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ishii Y, Ozaki S, Tanaka K, Kanda T. 2005. Human papillomavirus 16 minor capsid protein L2 helps capsomeres assemble independently of intercapsomeric disulfide bonding. Virus Genes 31:321–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kämper N, Day PM, Nowak T, Selinka HC, Florin L, Bolscher J, Hilbig L, Schiller JT, Sapp M. 2006. A membrane-destabilizing peptide in capsid protein L2 is required for egress of papillomavirus genomes from endosomes. J. Virol. 80:759–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schiller JT, Day PM, Kines RC. 2010. Current understanding of the mechanism of HPV infection. Gynecol. Oncol. 118:S12–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Day PM, Schiller JT. 2009. The role of furin in papillomavirus infection. Future Microbiol. 4:1255–1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Day PM, Gambhira R, Roden RBS, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. 2008. Mechanisms of human papillomavirus type 16 neutralization by L2 cross-neutralizing and L1 type-specific antibodies. J. Virol. 82:4638–4646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gambhira R, Karanam B, Jagu S, Roberts JN, Buck CB, Bossis I, Alphs HH, Culp T, Christensen ND, Roden RBS. 2007. A protective and broadly cross-neutralizing epitope of human papillomavirus L2. J. Virol. 81:13927–13931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bienkowska-Haba M, Patel HD, Sapp M. 2009. Target cell cyclophilins facilitate human papillomavirus type 16 infection. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000524 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Richards RM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, Day PM. 2006. Cleavage of the papillomavirus minor capsid protein, L2, at a furin consensus site is necessary for infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:1522–1527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schelhaas M, Shah B, Holzer M, Blattmann P, Kühling L, Day PM, Schiller JT, Helenius A. 2012. Entry of human papillomavirus type 16 by actin-dependent, clathrin- and lipid raft-independent endocytosis. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002657 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Surviladze Z, Dziduszko A, Ozbun MA. 2012. Essential roles for soluble virion-associated heparan sulfonated proteoglycans and growth factors in human papillomavirus infections. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002519 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schelhaas M. 2010. Come in and take your coat off—how host cells provide endocytosis for virus entry. Cell. Microbiol. 12:1378–1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith JL, Campos SK, Wandinger-Ness A, Ozbun MA. 2008. Caveolin-1-dependent infectious entry of human papillomavirus type 31 in human keratinocytes proceeds to the endosomal pathway for pH-dependent uncoating. J. Virol. 82:9505–9512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koshlukova SE, Lloyd TL, Araujo MWB, Edgerton M. 1999. Salivary histatin 5 induces non-lytic release of ATP from Candida albicans leading to cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 274:18872–18879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bordeaux J, Forte S, Harding E, Darshan MS, Klucevsek K, Moroianu J. 2006. The L2 minor capsid protein of low-risk human papillomavirus type 11 interacts with host nuclear import receptors and viral DNA. J. Virol. 80:8259–8262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fay A, Yutzy WH, IV, Roden RBS, Moroianu J. 2004. The positively charged termini of L2 minor capsid protein required for bovine papillomavirus infection function separately in nuclear import and DNA binding. J. Virol. 78:13447–13454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Florin L, Becker KA, Lambert C, Nowak T, Sapp C, Strand D, Streeck RE, Sapp M. 2006. Identification of a dynein interacting domain in the papillomavirus minor capsid protein L2. J. Virol. 80:6691–6696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schneider MA, Spoden GA, Florin L, Lambert C. 2011. Identification of the dynein light chains required for human papillomavirus infection. Cell. Microbiol. 13:32–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim S, Jeon TJ, Oberai A, Yang D, Schmidt JJ, Bowie JU. 2005. Transmembrane glycine zippers: Physiological and pathological roles in membrane proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:14278–14283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Russ WP, Engelman DM. 2000. The GxxxG motif: A framework for transmembrane helix-helix association. J. Mol. Biol. 296:911–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kleiger G, Grothe R, Mallick P, Eisenberg D. 2002. GXXXG and AXXXA: common alpha-helical interactions motifs in proteins, particularly in extremophiles. Biochemistry 41:5990–5997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schneider D, Engelman DM. 2004. Motifs of two small residues can assist but are not sufficient to mediate transmembrane helix interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 343:799–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim S, Chamberlain AK, Bowie JU. 2004. Membrane channel structure of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin: role of multiple GXXXG motifs in cylindrical channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:5988–5991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McClain MS, Iwamoto H, Cao P, Vinion-Dubiel AD, Li Y, Szabo G, Shao Z, Cover TL. 2003. Essential role of a GXXXG motif for membrane channel formation by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 278:12101–12108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Senes A, Engel DE, DeGrado WF. 2004. Folding of helical membrane proteins: the role of polar, GxxxG-like and proline motifs. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14:465–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roth L, Nasarre C, Dirrig-Grosch S, Aunis DCG, Hubert P, Bagnard D. 2008. Transmembrane domain interactions control biological functions of neuropilin-1. Mol. Biol. Cell 19:646–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Russ WP, Engelman DM. 1999. TOXCAT: a measure of transmembrane helix association in a biological membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:863–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cserzö M, Wallin E, Simon I, von Heijne G, Elofsson A. 1997. Prediction of transmembrane alpha-helices in prokaryotic membrane proteins: the dense alignment surface method. Protein Eng. 10:673–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hofmann K, Stoffel W. 1993. TMbase—a database of membrane spanning protein segments. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 374:166 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. 1994. A model recognition approach to the prediction of all-helical membrane protein structure and topology. Biochemistry 33:3038–3049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. 2001. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305:567–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meruelo AD, Samish I, Bowie JU. 2011. TMKink: a method to predict transmembrane helix kinks. Protein Sci. 20:1256–1264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pasquier C, Promponas VJ, Palaios GA, Hamodrakas JS, Hamodrakas SJ. 1999. A novel method for predicting transmembrane segments in proteins based on a statistical analysis of the SwissProt database: the PRED-TMR algorithm. Protein Eng. 12:381–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sapay N, Guermeur Y, Deléage G. 2006. Prediction of amphipathic in-plane membrane anchors in monotopic proteins using a SVM classifier. BMC Bioinformatics 7:255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shen H, Chou JJ. 2008. MemBrain: improving the accuracy of predicting transmembrane helices. PLoS One 3:e2399 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tusnády GE, Simon I. 2001. The HMMTOP transmembrane topology prediction server. Bioinformatics 17:849–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Campos SK, Chapman JA, Deymier MJ, Bronnimann MP, Ozbun MA. 2012. Opposing effects of bacitracin on human papillomavirus type 16 infection: enhancement of binding and entry and inhibition of endosomal penetration. J. Virol. 86:4169–4181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ishii Y, Tanaka K, Kondo K, Takeuchi T, Mori S, Kanda T. 2010. Inhibition of nuclear entry of HPV16 pseudovirus-packaged DNA by an anti-HPV16 L2 neutralizing antibody. Virology 406:181–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kondo K, Ishii Y, Ochi H, Matsumoto T, Yoshikawa H, Kanda T. 2007. Neutralization of HPV16, 18, 31, and 58 pseudovirions with antisera induced by immunizing rabbits with synthetic peptides representing segments of the HPV16 minor capsid protein L2 surface region. Virology 358:266–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tulumello DV, Deber CM. 2009. SDS micelles as a membrane-mimetic environment for transmembrane segments. Biochemistry 48:12096–12103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Spoden G, Fretag K, Husmann M, Boller K, Sapp M, Lambert C, Florin L. 2008. Clathrin- and caveolin-independent entry of human papillomavirus type 16: involvement of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs). PLoS One 3:e3313 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bergant Marušič M, Ozbun MA, Campos SK, Myers MP, Banks L. 2012. Human papillomavirus L2 facilitates viral escape from late endosomes via sorting nexin 17. Traffic 13:455–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Finger C, Escher C, Schneider D. 2009. The single transmembrane domains of human receptor tyrosine kinases encode self-interactions. Sci. Signal. 2:ra56 doi:10.1126/scisignal.2000547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Popov-Celeketić J, Waizenegger T, Rapaport D. 2008. Mim1 functions in an oligomeric form to facilitate the integration of Tom20 into the mitochondrial outer membrane. J. Mol. Biol. 376:671–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dixon AM, Stanley BJ, Matthews EE, Dawson JP, Engelman DM. 2006. Invariant chain transmembrane domain trimerization: a step in MHC class II assembly. Biochemistry 45:5228–5234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Melnyk RA, Kim S, Curran AR, Engelman DM, Bowie JU, Deber CM. 2004. The affinity of GXXXG motifs in transmembrane helix-helix interactions is modulated by long-range communication. J. Biol. Chem. 279:16591–16597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gerber D, Sal-Man N, Shai Y. 2004. Two motifs within a transmembrane domain, one for homodimerization and the other for heterodimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 279:21177–21182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jenei ZA, Borthwick K, Zammit VA, Dixon AM. 2009. Self-association of transmembrane domain 2 (TM2), but not TM1, in carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A: role of GXXXG(A) motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 284:6988–6997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li R, Gorelik R, Nanda V, Law PB, Lear JD, DeGrado WF, Bennett JS. 2004. Dimerization of the transmembrane domain of integrin alphaIIb subunit in cell membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 279:26666–26673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Unterreitmeier S, Fuchs A, Schaffler T, Heym RG, Frishman D, Langosch D. 2007. Phenylalanine promotes interaction of transmembrane domains via GxxxG motifs. J. Mol. Biol. 374:705–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tsai B. 2007. Penetration of nonenveloped viruses into the cytoplasm. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23:23–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Knauth P, Schlüter T, Czubayko M, Kirsch C, Florian V, Schreckenberger S, Hahn H, Bohnensack R. 2005. Functions of sorting nexin 17 domains and recognition motif for P-selectin trafficking. J. Mol. Biol. 347:813–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. van Kerkhof P, Lee J, McCormick L, Tetrault E, Lu W, Schoenfish M, Oorschot V, Strous GJ, Klumperman J, Bu G. 2005. Sorting nexin 17 facilitates LRP recycling in the early endosome. EMBO J. 24:2851–2861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Karanam B, Peng S, Li T, Buck C, Day PM, Roden RB. 2010. Papillomavirus infection requires gamma secretase. J. Virol. 84:10661–10670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Beel AJ, Sanders CR. 2008. Substrate specificity of γ-secretase and other intramembrane proteases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65:1311–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Munter LM, Voigt P, Harmeier A, Kaden D, Gottschalk KE, Weise C, Pipkorn R, Schaefer M, Langosch D, Multhaup G. 2007. GxxxG motifs within the amyloid precursor protein transmembrane sequence are critical for the etiology of Aβ42. EMBO J. 26:1702–1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wang H, Barreyro L, Provasi D, Djemil I, Torres-Arancivia C, Filizola M, Ubarretxena-Belandia I. 2011. Molecular determinants and thermodynamics of the amyloid precursor protein transmembrane domain implicated in Alzheimer's disease. J. Mol. Biol. 408:879–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Barrett PJ, Song Y, Van Horn WD, Hustedt EJ, Schafer JM, Hadziselimovic A, Beel AJ, Sanders CR. 2012. The amyloid precursor protein has a flexible transmembrane domain and binds cholesterol. Science 336:1168–1171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tamm LK, Han X, Li Y, Lai AL. 2002. Structure and function of membrane fusion peptides. Bioploymers 66:249–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cross KJ, Langley WA, Russell RJ, Skehel JJ, Steinhauer DA. 2009. Composition and functions of the influenza fusion peptide. Protein Pept. Lett. 16:766–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chang DK, Cheng SF, Chien WJ. 1997. The amino-terminal fusion domain peptide of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 inserts into the sodium dodecyl sulfate micelle primarily as a helix with a conserved glycine at the micelle-water interface. J. Virol. 71:6593–6602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lorieau JL, Louis JM, Bax A. 2010. The complete influenza hemagglutinin fusion domain adopts a tight helical hairpin arrangement at the lipid:water interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:11341–11346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Donald JE, Zhang Y, Fiorin G, Carnevale V, Slochower DR, Gai F, Klein ML, DeGrado WF. 2011. Transmembrane orientation and possible role of the fusogenic peptide from parainfluenza virus 5 (PIV5) in promoting fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:3958–3963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]