Abstract

Numerous studies have investigated the effect of Interactive Cancer Communication Systems (ICCSs) on system users’ improvements in psychosocial status. Research in this area, however, has focused mostly on cancer patients, rather than caregivers, and the direct effects of ICCSs on improved outcomes, rather than the psychological mechanisms of ICCS effects. In an effort to understand the underlying mechanisms, this study examines the mediating role of perceived caregiver bonding in the relationship between one ICCS (the Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System, CHESS) use and caregivers’ coping strategies. To test the hypotheses, secondary analysis of data was conducted on 246 caregivers of lung cancer patients. They were randomly assigned to either the Internet with links to high-quality lung cancer websites or access to CHESS, which integrated information, communication and interactive coaching tools. Findings suggest that perceived bonding has positive impacts on caregivers’ appraisal and problem-focused coping strategies, and it mediates the effect of ICCS on the coping strategies 6 months after the intervention began.

Introduction

Lung cancer accounts for the most cancer-related deaths in men and women in the United States (American Cancer Society, 2009). Different from other cancers, early lung cancer detection has shown limited effectiveness in reducing lung cancer deaths. The 5-year survival rate of lung cancer is only 15% (American Cancer Society, 2009). Thus, lung cancer has usually been considered as an insurmountable disease, and consequently, a lung cancer diagnosis understandably has a detrimental impact on patients’ mental and physical health.

This detrimental effect is not limited to the cancer patients themselves. A lung cancer diagnosis is also a highly traumatic event for family members. Beginning with diagnosis, these informal caregivers face an onset of numerous challenges and changing needs, such as acquiring relevant information and coping with unexpected problems in a timely manner (DuBenske, et al., 2008). Furthermore, they frequently confront social isolation that results from physical and social barriers (Brennan, Moore, & Smyth, 1991) and suffer from physical, social and emotional problems (Stenberg, Ruland, & Miaskowski, 2009).

To overcome these stressful circumstances, caregivers may desire to participate in support groups or seek out resources. However, the desire for such support competes with the reality of the practical demands of caregiving, such that these support groups and resources are often underutilized (Given, Given, & Kozachik, 2001). Interactive Cancer Communication Systems (ICCSs) have the potential to overcome some of the key barriers to face-to-face interventions. With asynchronous communication and absence of geographical barriers, participants of online groups have 24-hour availability at times most convenient to them (White & Dorman, 2000; 2001; van Uden-Kraan, et al., 2008). Asynchronous, text-based communication also allows ICCS users to manage the interaction more effectively than individuals in a face-to-face group, because they have enough time to think about how and what they can contribute to discussions (Rains & Young, 2009). In addition, anonymity and absence of physical presence reduce ICCS users’ social cues that may cause some undesirable or unnecessary biases, such as racial or sexual discrimination. Reduced social cues may help members feel more comfortable, especially when sharing sensitive health information or stigmatized topics. Accordingly, this unique feature of computer-mediated communication (CMC) creates an environment that can foster supportive communication (Shaw, McTavish, Hawkins, Gustafson, & Pingree, 2000; Rains & Young, 2009).

Ever since the rise of online self-help activities in the area of cancer, numerous studies have investigated the effect of ICCSs on cancer patients’ psychosocial health benefits. Research in this area, however, has focused mostly on cancer patients, rather than caregivers, and the direct effects of ICCSs on positive outcomes, rather than the psychological mechanisms that explain the effects of using such systems. In order to investigate the underlying processes of how ICCSs can confer caregivers’ psychosocial health benefits, this study examines the mediating role of perceived bonding with other caregivers in the relationship between ICCS use and caregivers’ coping strategies.

Interactive Cancer Communication System: CHESS

The Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (CHESS) is a non-commercial, home-based ICCS created by clinical, communication, nursing, psychology and decision-making scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (Gustafson et al., 1994, 1999, 2008). CHESS is a multi-component intervention that employs data on user health status to help users monitor their condition and guides them to cancer information, communication and coaching services. CHESS has demonstrated effectiveness in improving cancer patient’s quality of life (Gustafson, et al., 2008), health information competence (Han, et al., 2009), emotional well-being (Shaw, Hawkins, McTavish, Pingree, & Gustafson, 2006), and health self-efficacy (Lee, Hwang, Hawkins, & Pingree, 2008).

This study focuses on a recently developed and tested CHESS module, “Coping with Lung Cancer: A Network of Support (DuBenske, Gustafson, Shaw, & Cleary, 2010).” This module moved CHESS in a couple of new directions. First, aside from being the first CHESS module addressing lung cancer, it was also one of the first to focus on advanced stage disease and end of life. Second, because of the severity of advanced stage disease, which could make it difficult for the patients to use the system and participate in the study process, particular focus was placed on supporting the caregiver, rather than the patient, throughout caregiving as well as into bereavement.

The CHESS module presents a variety of conceptually distinct services under the headings, “Information,” “Support,” and “Tools.” Support services include different types of discussion groups, which have been the most heavily used services in CHESS (Han et al., 2009). The CHESS discussion group is a type of computer-mediated social support (CMSS) group offering text-based, asynchronous bulletin boards. Here users can anonymously communicate with one another, with opportunities to exchange several kinds of social support. For example, previous content analyses of messages posted in the CHESS discussion groups, have found that group members exchanged emotional (Han et al., 2010), informational (Namkoong et al., 2010) and spiritual support (Shaw et al., 2007).

Supportive communication in CMSS groups and its health benefits

Social support refers to a communicative behavior, either verbal or nonverbal, that helps the communicators manage uncertainty about a situation and, as a result, enhances a perception of personal control in the situation (Albrecht & Adelman, 1987). As a reciprocal process embedded in structures of social relationships (Goldsmith, McDermott, & Alexander, 2000), social support is performed for an individual by significant others in his/her social support network, such as family members and friends (Thoits, 1995). Supportive communication has been regarded as a necessary condition for quality of life and healthful living, with studies repeatedly showing that social support had profound impacts on mental and physical well-being (Albrecht & Goldsmith, 2003).

Social support groups are constructed interventions for supportive communication. Interactions in social support groups allow the group members to exchange social support with others who have suffered from similar problems, such as cancer caregiving. This unique supportive communication environment can foster perceived universality, the realization that others have similar problems, and this helps them experience close interpersonal relationships with other group members (Zhang, Galanek, Strauss, & Siminoff, 2008). In addition, social support groups can help people deal with their problems more effectively, by providing social models for coping behaviors (Posluszny, Hyman, & Baum, 1998).

CMSS groups share the same basic principle as face-to-face social support groups, providing opportunities to exchange social support among people facing similar stressors (Rains and Young, 2009). Beyond the benefits of the face-to-face group interventions, the unique communication patterns in CMSS groups, such as asynchronous, text-based, and anonymous communication, can help group participants exchange social support more frequently and efficiently due to the absence of time and geographical barriers. In turn, studies have demonstrated that the CMSS group participants experience a variety of health benefits, such as reduced depression (Lieberman et al., 2003), cancer-related trauma and perceived stress (Winzelberg et al., 2003), and improved self-perceived health status (Owen et al., 2005).

Although limited studies have examined CMSS groups for cancer caregivers, previous research has shown that caregivers are interested and willing to use this format of social support. Through examination of online caregiver support group messages, Klemm and Wheeler (2005) found that cancer caregivers share messages of hope and physical/emotional/psychological responses to their circumstances. Monnier (2002) found that caregivers are interested and willing to exchange online social support, reporting that 68% of cancer patients and caregivers in their study were specifically interested in online support. More recent work on interactive cancer communication systems has found caregivers who use the system felt less caregiver burden and negative emotions than those who used the Internet only (DuBenske et al, 2010).

In sum, the CMSS group is an additional and unique source of encouragement, emotional, and informational support in coping with their health problems. CMSS group interaction creates a network of people who inherently share the same problems and concerns. This provides crucial social support by connecting those who may not have similar others immediately available to them within their existing social networks. In addition, through supportive communication, participants learn about others’ experiences, and develop and maintain close interpersonal relationships that help the members cope more effectively with their stressors (Shaw et al., 2000).

Human bonding created in CMSS groups

Human bonding refers to the perception of a close relationship formed through interpersonal communication. Between adults, bonding often develops as a result of sharing intense experiences, such as life-threatening disease. Wasserman and Danforth (1988) argue that support group benefits depend directly on the element of human bonding. Universality, interpersonal learning and group cohesiveness in social support groups are closely related to core components of human bonding. The perception of universality has been considered a primary benefit in support groups for cancer patients, and requires commonality, on one of the central components of human bonding. A rationale for the perceived value of universality is the idea that individuals facing a similar stressor are in a unique position to understand one another in ways that one’s friends or family may not (Helgeson & Gottlieb, 2000; Rains & Young, 2009). Accordingly, sharing experiences with people who have the same problems and knowing that others share similar problems helps members feel less isolated (Weinberg, Uken, Schmale, & Adamek, 1995; Shaw et al., 2000; Zhang, et al., 2008). For example, in interviews with 13 prostate cancer patients who participated in a support group, Zhang and his colleagues found seven of these participants (53.9%) mentioned they experienced “bonding” with other group members, and valued sharing their experiences with people with similar problems (Zhang, et al., 2008).

Interpersonal learning and group cohesiveness are also closely associated with perceptions of human bonding. Yalom (1975) emphasized the role of human bonds as part of interpersonal learning within support groups. He argued that interpersonal behaviors have been adaptive in an evolutionary sense and based on positive, reciprocal, interpersonal bonds. Thus, interpersonal learning in a support group implicates the human connection among participants. He also emphasized the importance of group cohesiveness to be an important factor in contributing to beneficial experiences. Thus, group cohesiveness, a prerequisite of perceived bonding, is a crucial determinant of the positive psychosocial health outcomes associated with support group participation (Wasserman & Danforth, 1988).

Shaw and his colleagues (2000) found most of these elements of human bonding found in face-to-face social support groups were also present in CMSS groups. According to them, the CMSS group participants credited other members as being in a unique position to understand and help provide support because they shared similar problems and experiences. In addition, they had a desire to maintain intimate ties within the group, and these intimate relationships had emotional benefits. Therefore, supportive communication in CMSS groups can also create human bonding among group participants because of the perception of universality, interpersonal learning and group cohesiveness. The perception of bonding, in turn, likely plays a role in a variety of positive psychosocial health outcomes from CMSS group interventions.

It is possible that people can find and use services like CHESS discussion groups through the Internet, especially in some high-quality lung cancer websites. However, distinct from other CMSS groups available on the Internet, participants in CHESS support groups get the opportunity to know one another on an individual basis due to its purposefully limited size. According to Shaw and his colleagues (2000), some women would visit other computer-mediated support groups on the Internet to obtain information, but they would return to the CHESS support group for intimacy enabled by smaller group size. Other researchers also argue that CMSS group interventions are different from the informal and loosely structured self-help groups found on Websites, such as **Yahoo.com, because formal CMSS groups have both educational and group communication components, closed membership enrollments and fixed duration (Gottlieb, 2000; Helgeson & Gottlieb, 2000; Rains & Young, 2009). Thus, we can predict that people who use CHESS would have stronger a sense of bonding than those who just use the Internet, and as a result, they will have more positive health outcomes.

H1. Lung cancer caregivers who were in the CHESS group will perceive higher bonding with other caregivers than those who are in the Internet control group.

Caregivers’ Coping Strategies

Supportive communication can help individuals manage their stress and health problems, facilitating coping strategies (Albrecht & Goldsmith, 2003). Considerable health-related research, including caregiver studies, has focused on coping strategies as a personal resource for confronting stressors. Coping strategies generally refer to behavioral and/or cognitive responses to manage environmental stressors, which are appraised as exceeding one’s ability to adapt (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Billings and Moos (1984) classified coping strategies within three general categories: appraisal-focused coping, problem-focused coping, and emotion-focused coping. Appraisal-focused coping (aka, perception-focused coping) consists of cognitive efforts to define and redefine the personal meaning of the stressful situation (Billings & Moos, 1984; Pearlin & Schooler, 1978). Problem-focused coping refers to responses that intend to modify or eliminate stressors by handling the reality of the demands. Emotion-focused coping refers to responses that control emotions and attempts to maintain affective equilibrium (Billings & Moos, 1984). People can also physically or mentally disengage from the demanding situation, which is referred to as avoidance-focused coping (Kohn, 1996).

Burleson and Goldsmith (1997) argued that supportive communication encourages distressed people to reappraise a stressful situation and their coping resources. For example, studies of support groups for caregivers have shown that support group participation enhances more active and positive coping responses. Social interaction in support groups encourages the caregivers to take a more active role in learning about symptoms, treatments, and finding productive ways of supporting those with the disease for whom they are caring (Wright & Frey, 2007). It is noteworthy that these positive caregiver outcomes result from strong interpersonal bonding among the caregivers in the social support group. Chesney and Chesler (1993) found that caregivers who take part in support groups for parents of children with cancer were strongly associated with social activism, use of active coping strategies, and help-seeking. The increased activism and active coping strategies were based on strong interpersonal relationships among the group participants. For example, they worked with others to raise awareness about cancer issues in their communities, and during the process, they actively helped each other. Accordingly, increased bonding among the support group members enhanced their positive and active coping responses. Based on findings from this study, we predict that perceived caregiver bonding will be positively associated with caregivers’ active coping strategies, mediating the effects of CHESS use on both appraisals and behavioral responses to their situations.

H2. Perceived caregiver bonding will be positively related to caregivers’ coping strategies (active behavioral coping, positive reframing, and instrumental support).

In addition, this study investigates the mediating role of caregiver bonding in the relationship between CHESS use and increase in coping strategies to understand the psychological mechanism of the ICCS effect.

H3. Perceived caregiver bonding will mediate the effect of treatment group (Internet Control vs. CHESS) on the caregivers’ coping strategies.

Method

Experimental Design

Patient-caregiver dyads were recruited from four major cancer centers in the Northeastern, Midwestern and Southwestern United States from January 2005 to April 2007. Patient-caregiver dyads were eligible for this study if patients were English-speaking adults with non-small cell lung cancer at stage IIIA, IIIB, or IV, and a patient-identified primary caregiver was willing to participate in the study. In addition, the patient must have a clinician-perceived life expectancy of at least four months. Despite a 43.7% study accrual rate, 325 cancer patient-caregiver dyads enrolled in the study and 40 of them withdrew before completing the consent form and pretest. Details of reasons for why a substantial number of individuals declined to join the study, particularly regarding perceptions of the computer as a barrier are provided in Buss et al (2008). Finally, 285 dyads that completed pretests were randomly assigned to either Internet control (141) or CHESS (144) groups. Randomization was blocked by recruitment site, caregiver-patient relationship (e.g., spouse/significant other vs. non-spouse/significant other) and minority status (Caucasian vs. non-Caucasian). Although caregivers and patients were encouraged to try to log onto the computer regularly, use of the computer was not required in order to observe naturalistic adoption of the CHESS system. The control group received usual care, a laptop computer with Internet access if needed, and a list of high-quality patient-directed lung cancer and palliative care websites (e.g., cancer.gov and alcase.org) that were determined based on clinician recommendations. Those randomized to the CHESS group received access to the CHESS website as well as a laptop computer and Internet access. Caregivers completed a pretest prior to randomization and post-test surveys were sent every two months after receipt of the intervention for two years. Patient surveys were optional. In the initial study, main effects of CHESS were tested at 6 months post intervention (DuBenske et al, 2010). In accordance with that study which demonstrated CHESS’s impact at 6 months, this study also sets the 6-month survey as the target outcome. Out of 246 dyads who had taken the pretest, 104 caregivers completed the 6 month surveys (Table1 shows attrition details).

Table 1.

Patient/caregiver dyad attrition by study arm assignment

| Description of Dyads | Internet: Control-Group |

CHESS: Treatment-Group |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number randomized | 141 | 144 | 285 |

| Withdrew between randomization and starting the intervention | 17 | 18 | 35 |

| Patient died before intervention | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Caregiver received intervention | 122 | 124 | 246 |

| Dyads who dropped out of study | 4 | 8 | 12 |

| Patient died during 6 months of intervention | 30 | 31 | 61 |

| Caregiver did not return 6-month survey | 33 | 36 | 69 |

| Completed 6-month survey | 55 | 49 | 104 |

Note: 325 patient/caregiver dyads enrolled in study and 50 dyads withdrew prior to randomization.

The experimental condition received access to the CHESS “Coping with Lung Cancer: A Network of Support” ICCS. The CHESS program was designed for caregivers of lung cancer patients. CHESS integrates 15 services presented to provide patients and caregivers with information, communication, and coaching resources. Table2 listed and describe CHESS services (DuBenske et al., 2010).

Table 2.

CHESS services listed according to service category

| A. INFORMATION SERVICES | |

| Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) | Short answers to hundreds of common lung cancer questions; e.g., “How does chemotherapy work?” or “How do I know if I have depression?” |

| Instant Library | Full-text articles on lung cancer from scientific journals and the popular press; e.g., “Do I Have to Die in Pain?” - PBS |

| Resource Directory | Descriptions of and contacts for lung cancer organizations |

| Web Links | Links to high-quality content in health- and non-health-related sites |

| Cancer News | Summaries of lung cancer news and research; e.g., “Erlotinib Improves Survival in Stage III NSCLC” – August 2009 |

| Personal Stories | Real-life text accounts of how patients and caregivers cope with cancer |

| Caregiver Tips | Brief suggestions on topics written by experts and other CHESS users |

| B. COMMUNICATION SERVICES | |

| Discussion Groups | Limited-access, facilitated online support groups for—separately—patients, caregivers, and bereaved caregivers |

| Ask an Expert | Confidential expert responses to patient and caregiver questions |

| Personal Web Page | Guidance for setting up a patient’s own bulletin board and interactive calendar with family and friends to share updates and request help |

| Clinician Report | Three types: On Demand gives a summary report on a patient to a clinician who logs into CHESS; Threshold Alert sends an email notice to the clinician when the patient exceeds a threshold on a symptom; Clinic Visit Report sends an e-mail notice to the clinician two days before a patient’s scheduled clinic visit, suggesting that the clinician look at the report |

| C. COACHING AND TRAINING SERVICES | |

| Health Status | Prompts users to enter data and provides graphs showing how patient health status is changing |

| Decision Aids | Helps patients and caregivers think through difficult decisions by learning about options, clarifying values, and understanding consequences, e.g., Treatment Decision Aid or Respite Decision Aid |

| Easing Distress | Uses principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy to help patients and caregivers identify emotional distress and cope with it |

| Healthy Relating | Teaches techniques to increase closeness and decrease conflict |

| Action Plan | Guides patients and caregivers in building a plan for change, including identifying and overcoming obstacles |

Measures

Exogenous Variables

Six variables served as antecedent exogenous variables in our model: age, gender, education, caregiver comfort using the Internet, post-test score of caregiver perception of patient’s symptom distress, pretest score of each endogenous variable, and experimental condition. Caregiver age (M=55.56, SD=12.55, range 18–84 years) and gender (68.3% of respondents were female) were assessed at the pretest survey. Education was measured using six categories that ranged from less than a high school degree (coded 1) to graduate degree (coded 6) (M=3.87, SD=1.49, Median=4). Caregiver comfort using the Internet was also assessed at pretest with the single item “How comfortable are you using the Internet?” rated on a five-point scale from 0 ( “not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”) (M=2.53, SD=1.25). Pretest scores of each endogenous variable (bonding, and coping strategies) were also used as exogenous variables, which were found to have strong effects on the outcome variables. Finally, our experimental condition (0=Internet control group, 1=CHESS group) was included as an exogenous variable.

Endogenous Variables

Bonding

A five-item bonding scale was used to capture the concept of universality, group cohesiveness, and informational and emotional support exchanged in an ICCS. This scale had been validated in a previous CHESS study (Gustafson et al., 2008), showing positive and significant correlation with the social support scale, which had been used in several studies. Participants were asked to indicate on a five point scale (0=never, 4=nearly always) their level of frequency in feeling each of the following five statements: (1) “I feel stronger knowing that there are others are in my situation;” (2) “I’ve been getting emotional support from others in my situation;” (3) “I can get information from other caregivers;” (4) “It helps me to be able to share my feelings and fears with other caregivers;” and (5) “I am building a bond with other caregivers” (pretest: α=.89; posttest: α=.91).

Appraisal and Problem-focused Coping Strategies

Among the three domains of coping strategies (Billings & Moos, 1984), appraisal-focused and problem-focused coping strategies are the dependent variables of interest. Emotion-focused coping responses are not included in the analysis, because the definition of perceived bonding in this study shares some commonality with the concept of emotional support between caregivers. To measure the two other domains, three coping strategies - positive reframing (appraisal-focused), active behavioral coping, and seeking instrumental support (problem-focused) - were selected from the Brief Cope (Carver, 1997), which has been used and validated extensively in many health-relevant studies and among several ethnic groups (Muller & Spitz, 2003). All coping strategies of the Brief Cope were measured using two five-point-scale items ranging from 0=not at all to 4=a lot. Positive Reframing was measured with two statements: (1) “I have been trying to it in a different light, to make it seem more positive,” and (2) “I have been looking for something good in what is happening” (inter-item correlation: pretest=.44; posttest=.44). To measure a active behavioral coping strategy, participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with each of the following statements: (1) “I have been concentrating my effort on doing something about the situation they are in,” and (2) “I have been taking action to try to make the situation better” (inter-item correlation: pretest=.52; posttest=.40). Instrumental support in the Brief Cope was measured with the following two items: (1) “I have been getting help and advice from other people,” and (2) “I have been trying to get advice or help from other people about what to do” (inter-item correlation: pretest=.62; posttest=.78). Table 3 presents mean and standard deviation of bonding and three coping strategies by treatment group.

Table3.

Means and standard deviations of dependent variables

| Dependent variables | Pre-test | 6 months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | ||

| Bonding | Control | 113 | 1.19 | 1.01 | 54 | 1.08 | .88 |

| CHESS | 114 | 1.42 | .98 | 45 | 1.44 | .84 | |

| Active Coping | Control | 117 | 1.76 | 1.07 | 55 | 1.36 | .89 |

| CHESS | 123 | 1.92 | .94 | 46 | 1.50 | .91 | |

| Positive Reframing | Control | 118 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 54 | 1.38 | 1.09 |

| CHESS | 122 | 1.78 | 1.04 | 46 | 1.25 | .98 | |

| Instrumental Support | Control | 120 | 1.26 | 1.00 | 55 | 1.06 | .91 |

| CHESS | 123 | 1.36 | .96 | 46 | 1.09 | .98 | |

Structural Equation Modeling for Testing Mediation

To test the mediating role of perceived bonding in the relationship between experimental condition (Internet Control vs. CHESS) and caregiver coping strategies, we employed structural modeling techniques, using the Mplus5.1 (Muthen & Muthen, 2007). Because structural equation modeling allows for the simultaneous estimation of all parameters in a model, all coefficients in a model indicate the relationship between two variables after controlling for all exogenous factors in the model. This approach allowed us to examine the direct influence of CHESS access on caregivers’ coping strategies and to see the indirect impacts through perceived bonding, the main intermediary variable of this study.

Results

The main focus of this study is on the mediating role of perceived caregiver bonding in the effect of CHESS access on caregivers’ coping strategies. For this purpose, we constructed structural equation models to test our hypotheses at 6 months after the intervention began. Table4 summarizes results and displays structural parameters. In order to control possible spurious and third variable influences on the relationships among the variables, our model incorporates possible covariates: age, gender, education, caregiver comfort using the Internet, and pretest score for each endogenous variable. As might be expected, all pretest scores of each endogenous variable were strongly related with posttest values of the same variables, representing the stability of that construct. In contrast, other control variables were seldom associated with the endogenous variables.

Table4.

Relationship among exogenous and endogenous variables at 6 Months

| Coping Strategies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonding | Active Behavior |

Positive Reframing |

Instrumental Support |

|

| Age | .153 | .031 | −.017 | −.066 |

| Gender (Female=1) | .101 | −.037 | .057 | .072 |

| Education | .065 | −.039 | −.081 | .123 |

| Internet Comfort | .085 | −.004 | −.082 | −.109 |

| Pretest Valuea | .433*** | .296*** | .492*** | .375*** |

| CHESS Use | .174* | −.018 | −.153 | −.046 |

| Bonding | .260* | .201* | .319** | |

Notes. Coefficients are standardized Gamma (γ) and Beta (β: for the last row of the table).

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

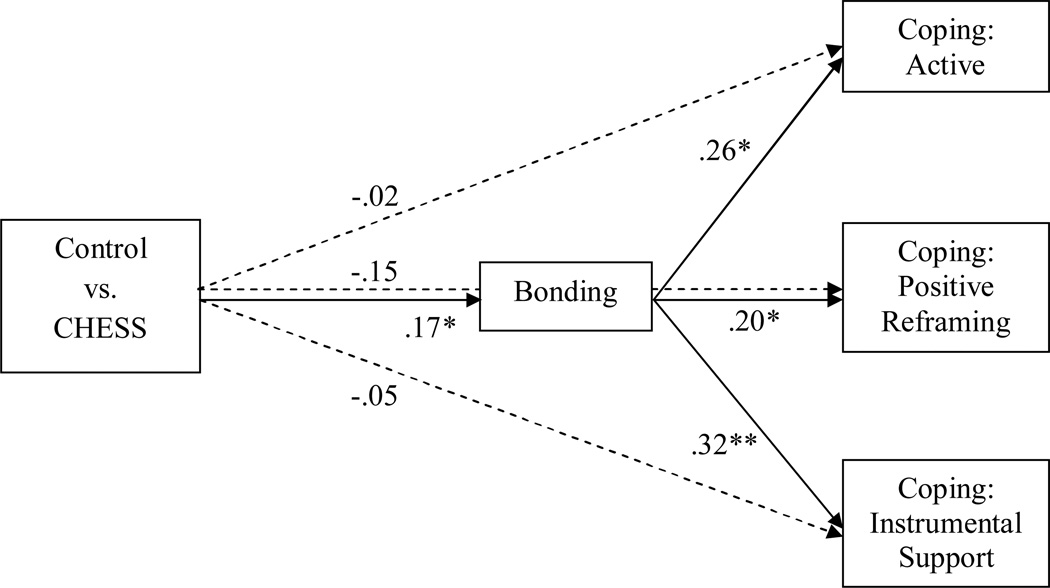

Our first hypothesis predicted that caregivers assigned to the CHESS condition would perceive higher bonding with other caregivers than those who were assigned to the control group. As shown in Table4, 6 months after the intervention was provided, CHESS use did have a significant and positive effect on caregivers’ perceived bonding (γ=.17, p<.05). Thus, the first hypothesis was supported. We also hypothesized that the perceived caregiver bonding would be positively associated with caregivers’ coping strategies. As expected, perceived bonding was positively related to all three caregivers’ coping strategies (active behavior: β=.26, p<.05; positive reframing: β=.20, p<.05; instrumental support: β=.32, p<.01). This result supported the second hypothesis.

Figure 1 displays the direct effects among experimental conditions and endogenous variables after controlling for the effects of covariates listed above. As shown in Figure1, there were no significant effects for the treatment group on all three coping strategies (active: γ =−.02, ns; positive reframing: γ=−.15, ns; instrumental support: γ=−.05, ns), while it had an initial effect on perceived caregiver bonding and, in turn, the bonding was positively associated with caregivers’ coping strategies. These results revealed that the perceived caregiver bonding fully mediates the effect of treatment on the caregivers’ coping strategies. The fitness indices of the final mediation model showed the model fits the data well (χ2=16.592 (12), p=.166, RMSEA=.061, SRMR=.045, and CFI=.966).

Figure1.

Mediating role of bonding in the effect of CHESS use on caregivers’ coping strategies (6 Month)

χ2=16.592 (12), p=.166, RMSEA=.061, SRMR=.045, and CFI=.966

*p<.05, ** p<.01, ***p<.001

Discussion

This study examined a psychological mechanism, bonding, to explain the reason why using an ICCS produces beneficial psychological outcomes among caregivers. For this purpose, this research hypothesized that lung cancer caregivers given access to the CHESS group would perceive higher bonding than those in the Internet control group. In addition, we also predicted that enhanced bonding would have positive impacts on caregivers’ coping strategies. As expected, caregivers’ perceived bonding fully mediated the effect of having CHESS on coping strategies at 6 months. In other words, having access to CHESS increases human bonding between users, and in turn that perceived bonding is associated with users employing more active coping strategies.

Yalom (1975) presented several curative factors of group intervention, such as universality, interpersonal learning, and group cohesiveness, and Wasserman and Danforth (1988) argue that many of the factors depend directly on the element of human bonding. Even though their arguments were originally posited to accrue from participating in face-to-face support groups, interviews with ICCS users showed the curative factors can be applicable to online support groups as well (Shaw, et al., 2000). This study empirically supports their arguments by demonstrating the beneficial effect of human bonding, as experienced through computer-mediated communication in an ICCS. It reveals that communication with other people facing a similar problem leads to a sense of belonging, and the perceived human bonding between caregivers has positive effects on caregivers’ coping strategies, such as active behavioral coping and seeking instrumental support. These two coping strategies have been regarded as very active and problem-focused responses to specific stressful events. In addition, though positive reframing is not a behavioral coping response, it also can be considered as an active appraisal coping strategy, because it shows more cognitively active processes beyond just accepting the stressful situation as it is. According to Wright & Frey (2007), active coping strategies are generally associated with positive adaptation to problems, and perceptions that the problem is not insurmountable, while passive coping strategies may be more effective when people perceive that the problem is beyond their control. Therefore, the results of this study may imply enhanced perceived bonding could encourage the caregivers to view their problems as easier to overcome.

Studies on social support and health have consistently shown that positive human relationships are linked to both physical and mental health (Schwarzer & Leppin, 1989). Acknowledging the effects of positive human relationships on health, McCabe and his colleagues (1996) emphasized that the quality of a relationship is a critical mediator of both physical and mental health and subjective well being. In other words, health benefits produced by relationships depend not on the mere existence of the relationship but also its depth and intimacy. The findings of the current study support their arguments, in that the measure of caregiver bonding used in this study attempted to reflect the quality of relationships among CMSS group participants.

Previous research argued that ICCSs, like CHESS, are different from the informal self-help groups found on the Internet, because the formal ICCSs have both educational and group communication components and closed membership enrollments (Gottlieb, 2000; Helgeson & Gottleib, 2000; Rains & Young, 2009; Shaw et al., 2000). This study supports these arguments by showing the difference in perceived bonding between the users of an ICCS and the Internet, and its consequences in adopting different coping strategies.

This secondary analysis highlights the potential benefits ICCSs can have on caregiver bonding. However, conclusions should be somewhat guarded in light of three noteworthy considerations for future research. First, the concept of bonding is defined as strong interpersonal connection through mutual social support among those who have similar problems. In other words, caregiver bonding was operationalized as a specific kind of social support. Thus, to clarify the effect of bonding on other psychological benefits, future research would be strengthened by controlling the effect of other kinds of social support, such as perceived social support from family members or friends. By comparing the bonding effect with other kinds of social support effects, future research could expand on these initial findings and examine the concept of bonding in a wider range of social support and relevant sub-dimensions. Second, as mentioned previously, this study sets the 6-month survey as the target outcome, following the initial study of main effects of CHESS for lung cancer caregivers. This cross sectional analysis suggests the mediating role perceived caregiver bonding has between CHESS use and three coping strategies. Based on these findings, further analyses are in progress investigating the longitudinal impact of CHESS on perceived bonding and the relationship between bonding and other dependent variables. Finally, this study focused only on caregivers of lung cancer patients, because the CHESS module used in this study was designed with a particular focus on lung cancer caregiver outcomes and the patient surveys were limited in scope and optional. In future studies, therefore, it would be worthwhile to test the model of this study with other CHESS modules designed for other types of cancer patients and caregivers.

This study just begins to address the underlying mechanism of ICCS effects. It shows that human bonding can be enriched through the computer-mediated interaction in an ICCS, and the enhanced bonding can have positive impacts on coping strategies. Considering that bonding captures the quality of the social relationship as well as strength of social tie, the results of this study support the idea that what matters is the quality of the relationship, not just the relationship itself. In this sense, the concept of bonding needs more academic attention to help explain the underlying psychological mechanism of the effect of ICCSs on several important psychosocial health benefits.

Acknowledgments

Grant Funding:

National Cancer Institute (1 P50 CA095817-01A1)

Reference

- Albrecht TL, Adelman MB. Communication networks as structures of social support. In: Albrecht T, Adelman M, editors. Communicating social support. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. pp. 40–60. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht TL, Goldsmith DJ. Social support, social networks, and health. In: Thompson T, et al., editors. Handbook of health communication. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 263–284. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Atlanta, GA: Author; 2009. [Retrieved July, 21, 2009]. Cancer facts and figures 2009. from http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/500809web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Billings AG, Moos RH. Coping, stress, and social resources among adults with unipolar depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:877–891. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PF, Moore SM, Smyth KA. ComputerLink: Electronic support for the home caregiver. Advances in Nursing Science. 1991;13(4):14–27. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199106000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleson BR, Goldsmith DJ. How comforting messages work: Some mechanisms through which messages may alleviate emotional distress. In: Anderson PA, Guerrero LK, editors. Handbook of communication and emotion: Research, theory, applications, and contexts. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 245–280. [Google Scholar]

- Buss MK, DuBenske LL, Dinauer S, Gustafson DH, McTavish F, Cleary JF. Patient/caregiver influences for declining participation in supportive oncology trials. Journal of Supportive Oncology. 2008;6:168–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4(1):92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney BK, Chesler MA. Activism through self-help group membership. Small Group Research. 1993;24(2):258–237. [Google Scholar]

- DuBenske LL, Wen KY, Gustafson DH, Guarnaccia CA, Cleary JF, Dinauer SK, et al. Caregivers’ Needs at Key Experiences of the Advanced Cancer Disease Trajectory. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2008;6:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBenske LL, Gustafson DG, Namkoong K, Hawkins RP, Brown R, McTavish FM, et al. Effects of an interactive cancer communication system on lung cancer caregivers’ quality of life and negative mood: A randomized clinical trial; Paper presented at the International Psycho-Oncology Society; Quebec, QC, Canada. 2010. May, [Google Scholar]

- DuBenske LL, Gustafson DH, Shaw BR, Cleary JF. Web-based cancer communication and decision making systems: Connecting patients, caregivers and clinicians for improved health outcomes. Medical Decision Making. 2010;30(6):732–744. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10386382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Given BA, Given CW, Kozachik S. Family support in advanced cancer. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2001;51:213–231. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.4.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith DJ, McDermott VM, Alexander SC. Helpful, supportive and sensitive: Measuring the evaluation of enacted social support in personal relationships. Journal of social and personal relationships. 2000;17(3):369–391. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb BH. Selecting and planning support interventions. In: Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH, editors. Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 195–220. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Boberg E, Pingree S, Serlin RE, Graziano F, et al. Impact of patient-centered, computer-based health information/support system. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1999;16:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, McTavish FM, Pingree S, Chen WC, Volrathongchai K, et al. Internet-based interactive support for cancer patients: Are integrated systems better? Journal of Communication. 2008;58(2):238–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Wise M, McTavish FM, Wolberg W, Stewart J, Smalley RV, et al. Development and pilot evaluation of a computer-based support system for women with breast cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1994;11(4):69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Han JY, Hawkins RD, Shaw BR, Pingree S, McTavish FM, Gustafson DH. Unraveling uses and effects of an interactive health communication system. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media. 2009;53(1):112–133. doi: 10.1080/08838150802643787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JY, Shah DV, Kim E, Namkoong K, Lee SY, Moon TJ, et al. Empathic exchanges in online cancer support groups: Distinguishing message expression and reception effects. Paper presented at the International Communication Association Conference; Singapore. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Gottleib BH. Support groups. In: Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottleib BH, editors. Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 221–245. [Google Scholar]

- Klemm P, Wheeler E. Cancer caregivers online: Hope, emotional roller coaster, and physical/emotional/psychological responses. Computer, Informatics, Nursing. 2005;23(1):38–45. doi: 10.1097/00024665-200501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn PM. On coping adaptively with daily hassles. In: Zeidner M, Endler NS, editors. Handbook of coping: Theory, research, applications. New York: Wiley; 1996. pp. 181–201. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MA, Golant M, Giese-Davis J, Winzlenberg A, Benjamin H, Humphreys K, et al. Electronic support groups for breast carcinoma: A clinical trial of effectiveness. Cancer. 2003;97:920–925. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Hwang H, Hawkins RP, Pingree S. Interplay of negative emotion and health self-efficacy on the use of health information and its outcomes. Communication Research. 2008;35(3):358–381. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe MP, Cummins RA, Romeo Y. Relationship status, relationship quality, and health. Journal of Family Studies. 1996;2:109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Monnier J. Patient and caregiver interest in Internet-based cancer services. Cancer Practice. 2002;10(6):305–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.106005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller L, Spitz E. Multidimensional assessment of coping: Validation of the Brief COPE among French population. Encephale. 2003;29(6):507–518. Abstract retrieved from PubMed. (PMID: 15029085) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Namkoong K, Shah DV, Han JY, Kim SC, Yoo W, Fan D, et al. Expression and reception of treatment information in breast cancer support groups: How health self-efficacy moderates effects on emotional well-being. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.009. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen JE, Klapow JC, Roth DL, Shuster JL, Bellis J. Randomized pilot of a self-guided Internet coping group for women with early-stage breast cancer. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;30:54–64. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3001_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schooler C. The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1978;19:2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posluszny DM, Hyman KB, Baum A. Group interventions in cancer: The benefits of social support and education on patient adjustment. In: Tindale RS, Edwards J, Bryant FB, editors. Theory and research on small groups. New York: Plenum; 1998. pp. 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rains SA, Young V. A meta-analysis of research on formal computer-mediated support groups: Examining group characteristics and health outcomes. Human Communication Research. 2009;35(3):309–336. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Leppin A. Social support and health: A meta-analysis. Psychology & Health. 1989;3(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BR, Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, McTavish FM, McDowell H, Pingree S, et al. How underserved breast cancer patients use and benefit from eHealth programs: Implications for closing the digital divide. American Behavioral Scientist. 2006;49:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw B, Han JY, Baker T, Witherly J, Hawkins R, McTavish F, et al. How women with breast cancer learn using interactive cancer communication systems. Shaw, B. Health Education Research. 2007;22:108–119. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw B, Han JY, Kim E, Gustafson D, Hawkins RP, Cleary J, et al. Eff ects of prayer and religious expression within computer support groups on women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;7:676–687. doi: 10.1002/pon.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BR, Hawkins RP, McTavish F, Pingree S, Gustafson DH. Effects of insightful disclosure within computer mediated support groups on women with breast cancer. Health Communication. 2006;19(2):133–142. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1902_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BR, McTavish F, Hawkins RP, Gustafson DH, Pingree S. Experiences of women with breast cancer: Exchanging social support over the CHESS computer network. Journal of Health Communication. 2000;5(2):135–159. doi: 10.1080/108107300406866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2009 doi: 10.1002/pon.1670. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35:53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CH, Taal E, Shaw BR, Seydel ER, van de Laar MA. Empowering processes and outcomes of participation in online support groups for patients with breast cancer, arthritis, or fibromyalgia. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(3):405–417. doi: 10.1177/1049732307313429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman H, Danforth HE. The human bond: Support groups and mutual aid. New York: Springer; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg N, Uken JS, Schmale J, Adamek M. Therapeutic factors: Their presence in a computer-mediated support group. Social Work with Groups. 1995;18(4):57–69. [Google Scholar]

- White M, Dorman SM. Online support for caregivers: Analysis of an Internet Alzheimer mailgroup. Computers in nursing. 2000;18(4):168–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White M, Dorman SM. Receiving social support online: Implication for health education. Health Education Research. 2001;16(6):693–707. doi: 10.1093/her/16.6.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzelberg AJ, Classen C, Alpers GW, Roberts H, Koopman C, Adams RE, et al. Evaluation of an Internet support group for women with primary breast cancer. Cancer. 2003;97:1164–1173. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KB, Frey LR. Communication and support groups for people living with cancer. In: O’Hair HD, Kreps GL, Sparks L, editors. The handbook of communication and cancer care. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press Inc.; 2007. pp. 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Yalom ID. The theory and practice of group psychotherapy. 2nd ed. New York: Basic Books; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang AY, Galanek J, Strauss GJ, Siminoff LA. What it would take for men to attend and benefit from support groups after prostatectomy for prostate cancer: A problem-solving approach. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2008;26(3):97–112. doi: 10.1080/07347330802118123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]