Abstract

Objectives

To present responses to sexual function items contained within the quality of life (QOL) survey of the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) LAP2 study, to investigate associations between sexual function and other factors such as relationship quality and body image), and to explore patterns of response in endometrial cancer patients.

Methods

Participants enrolled on the LAP2 QOL study arm completed a self-report QOL survey, which contained sexual function items, before surgery, and at 1, 3, 6-weeks and 6-months post surgery. Responses to sexual function questions were classified into three patterns—responder, intermittent responder and non-responder—based on whether the sexual function items were answered when the QOL survey was completed.

Results

Of 752 patients who completed the QOL survey, 225 completed the sexual function items within the QOL survey, 224 responded intermittently, and 303 did not respond at all. No significant differences of sexual function were found between the patients randomized to laparoscopy compared to laparotomy. Among those who responded completely or intermittently, sexual function scores declined after surgery and recovered to pre-surgery levels at 6 months. Sexual function was positively associated with better quality of relationship (P<0.001), body image (P<0.001), and QOL (P<0.001), and negatively associated with fear of sex (P<0.001).

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that younger patients, those who were married, and those who had quality relationships were more likely to answer the sexual function items and have better quality of sexual function. Factors such as age, relationship quality, body image, and pain may place women with endometrial cancer at risk for sexual difficulties in the immediate recovery period; however, sexual function improved by 6-months postoperatively in our cohort of early-stage endometrial cancer patients.

Keywords: sexual function, endometrial cancer, gynecologic cancer treatment, laparoscopy, laparotomy

INTRODUCTION

Gynecologic cancers account for ~11% of the newly diagnosed female cancers in the US and 18% globally.1 Uterine cancer is the most common gynecologic cancer in the US, with an estimated 46,470 new cases in 2011.2 Comprehensive surgical staging is the standard of care and includes the removal of the uterus and ovaries. In 1996, the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) opened a randomized, prospective clinical trial (GOG-2222, or LAP2) to compare comprehensive surgical staging by laparotomy (open approach) versus laparoscopy for the treatment of women with stage I to IIA uterine cancer (n=2,616).3 In 2009, the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) published the results of LAP2 regarding the completeness of surgical staging, recurrence-free survival, complications, and quality of life (QOL) of laparoscopy versus laparotomy as primary treatment for endometrial cancer.3,4 Laparoscopy was proven safe and feasible, and associated with a QOL advantage over laparotomy.3,4 The advantage of laparoscopy was further established in a report by Walker et al in 2012.5 However, sexual function items were not evaluated in either analysis.

Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in the general US population is ~40%,6–9 but in patients with gynecologic cancers the rate can b~80%.10 Sexual morbidity is associated with poor psychological adjustment and QOL in gynecologic cancer survivors11–14 both immediately post-treatment 4, 14,15 and in long-term survivorship.16–18 Data on sexual dysfunction varies greatly within the gynecologic oncology literature. Despite endometrial cancer being the leading gynecologic malignancy, it is the least studied in this area. There have been a few studies in these patients, but study approaches, cancer treatments, and findings have varied. A recent prospective study found early-stage endometrial (and cervical) cancer patients experienced major physical changes such as vaginal stenosis and diminished sexual activity.19 However, these physical changes did not result in poorer sexual satisfaction or desire,19 supporting earlier qualitative findings indicating post-treatment sexual satisfaction is associated with intimacy rather than intercourse.20 Although, a recent cross-sectional study using a validated sexual function measure indicated 89% of endometrial cancer survivors (stage I-IIIa) had sexual dysfunction.21 It is unclear if adjuvant radiation therapy and vaginal toxicity played a factor, as reported in other studies.22–25

This ancillary data study was designed to explore the sexual function items of early-stage endometrial cancer patients surgically treated on LAP2. Patterns associated with participants who did and did not respond to these items within the QOL survey will also be examined. Primary study aims were to investigate and present responses to sexual function items over time and determine whether antecedent variables (demographics, stage, surgical treatment type [laparotomy vs laparoscopy]) and mediating variables (relationship quality, body image, fear of sex, fear of recurrence) impacted sexual function in this cohort. We also analyzed whether quality of relationships influence response to sexual function items or scores. Additionally, we explored factors associated with response patterns and examined if responders versus non-responders differed by demographics, relationship, extent, and/or medical characteristics. Our study will hopefully provide guidance for the development of interventions to enhance coping and QOL in survivorship and identify subgroups for future intervention studies.

METHODS

Sample

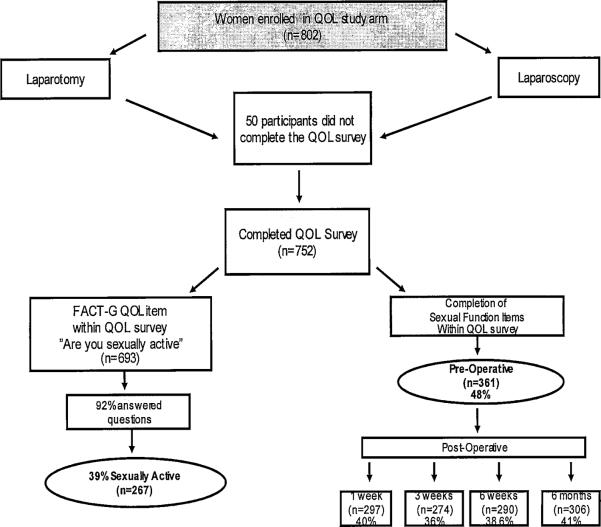

This study included newly diagnosed endometrial cancer patients consented/enrolled on GOG's LAP2 clinical trial before surgery and followed 6 months postoperatively.3 This protocol was IRB approved at each participating GOG institution. Participants completed QOL self-report surveys,4 and unpublished sexual function items were examined for this ancillary data study (Figure 1 [study schema]).

Figure 1.

LAP2 Quality of Life (QOL) Study Schema

LAP2 QOL Survey

The self-report QOL survey used in LAP2 assessed primary QOL dimensions (physical symptoms, physical role/vocational, social functioning, and psychological state) and queried issues of: pain, time to return to work and resume activities, body image, sexual relationships, and fear of recurrence. QOL survey data was collected at preop, 1, 3 and 6-weeks, and 6-months. Greater details are available in published reports containing the broader analysis.3,4 The following measures (or items) within the LAP2 QOL survey were used in this data analysis.

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale-General(FACT-G) - is the “core” QOL measure with 34 items grouped into 5 subscales: physical, social/family, emotional, functional well-being, and relationship with doctor. Most subscale items are rated on a 5-item Likert scale, from “not at all” to “very much.” Larger scores indicate better QOL.

Wisconsin Brief Pain Inventory(BPI) - measures pain severity and its interference with daily functioning. Pain severity is rated from “at its least” and “at its worst” on 2 items ranging from 0–10 (“no pain” to “pain as bad as you can imagine”). Higher scores indicate greater pain.

Fear of Relapse/Recurrence Scale- consists of 5 items measuring a patient's beliefs and anxieties concerning their disease recurring.4 All items are rated on a 5-item Likert scale, from “not at all” to “very much.” Larger scores indicate greater fear of recurrence.

Personal Relationships Subscale – consists of 7 items designed to assess the effect of surgery upon aspects of patients' sexual functioning—desire, arousal, feeling sexually attractive, partner's sexual response, pain during intercourse, and fear of sexual relations. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from “not at all” to “very much”. Larger scores suggest better relationships.

Personal Appearance Subscale - consists of 7 items assessing patients' concerns of physical appearance and its relationship to other areas in their life after being surgically treated for cancer. Items include concerns about their surgical scar, its effect upon feeling feminine, response of their partner to the scar, and degree to which scars are a reminder of cancer treatment rated on a 5-item Likert scale (“not at all” to “very much”). Larger scores indicate a more positive view of appearance.

Sociodemographic Characteristics - assessed basic sociodemographic characteristics (education, marital status, and employment) at enrollment.

Procedure

QOL survey items within personal relationship and appearance subscales were reviewed for the ancillary study and exploratory analysis. Within these subscales, we identified different content domains addressing: 1) sexual function; 2) quality of relationships; 3) body image; and 4) fear of intercourse. Items were reconceptualized into domains; new constructs (and their items) are presented in Table 1. For purposes of this paper, reference to sexual function, body image, quality of relationships, or fear of intercourse will refer to these constructs.

Table 1.

Reconceptualized Constructs

| Construct | QOL subscale |

|---|---|

| Sexual Function | |

| 1) I am interested in having sex | Personal Relationship Subscales |

| 2) I am able to become sexually aroused | Personal Relationship Subscales |

| 3) I have pain in my vagina during sex | Personal Relationship Subscales |

| 4) I am satisfied with my sex life | FACT-G |

| Body Image | |

| 1) My physical appearance is important to me | Personal Appearance Subscale |

| 2) I am satisfied with the way my stomach area looks | Personal Appearance Subscale |

| 3) I am satisfied with the way my body looks overall | Personal Appearance Subscale |

| 4) I am able to feel like a woman | Personal Appearance Subscale |

| 5) I feel sexually attractive | Personal Relationship Subscale |

| Quality of Relationships | |

| 1) I feel close to my partner | FACT-G |

| 2) I am able to express affection to my partner | Personal Relationship Subscale |

| 3) My partner is able to express affection to me | Personal Relationship Subscale |

| Fear of Sex | |

| 1) I am afraid to have sex | Personal Relationship Subscale |

FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale-General

Sexual Function Construct - consists of 4 items—3 from the personal relationship subscale and 1 from the social well-being subscale of the FACT-G. Each item is rated from 1=“not at all” to 5=“very much”. Score for one item was reversed. The subscale score is calculated by adding items scores. Larger scores suggest better sexual function. Cronbach α coefficient of 0.67 at preop and 0.74 at 6 months demonstrate acceptable internal consistency.

Body Image Construct - consists of 4 items from the personal appearance subscale and 1 item from the personal relationship subscale. Each item is rated from 1=“not at all” to 5=“very much”. The subscale is calculated by adding the item scores. Larger score indicates more positive body image. Cronbach α coefficient of 0.75 at preop and 0.76 at 6 months demonstrates acceptable internal consistency.

Relationship Quality Construct - includes 1 item from FACT-G social well-being subscale and 2 items from personal relationship subscale. Each item is based on the following scale: 1=“not at all” to 5=“very much,” and total score is calculated by adding the items. A larger score indicates a higher relationship quality. Cronbach α coefficient of 0.67 at preop and 0.54 at 6 months demonstrates marginal internal consistency.

Fear of Sex Construct - is evaluated with 1 item (“I am afraid to have sex”) from the personal relationship subscale and scored as 1=“not at all” to 5=“very much.” A larger score indicates greater fear of sex.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis for this paper presents the unpublished findings from the sexual function items and conducts an exploratory on all LAP2 QOL participants to examine response patterns for the sexual function items, as defined below.

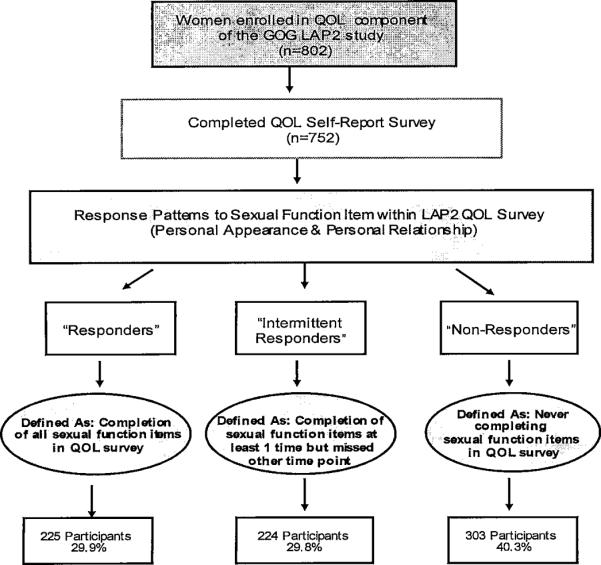

Response Patterns

Less than half of the QOL survey participants responded to sexual function questions during QOL assessment and response patterns also varied by assessment times. To identify potential characteristics or factors associated with compliance in answering sexual function items, we defined response patterns into three classes: 1) participants who always completed the sexual function items whenever a QOL assessment was completed—“responders”; 2) participants who never responded to sexual function items—“non-responders”; and 3) participants who completed sexual function items at one time point but not another—“intermittent responders” (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Response Pattern

Associations between responsiveness to sexual function items and participants characteristics was examined with a generalized linear model assuming multinomial probability distribution for response patterns. Percentage of scaled categories scored by each construct item were examined and summarized for sexual function item responders. Item scores are an ordinal variable, and a generalized estimating equations approach was applied to test the treatment difference over time between the randomized groups and use cumulative logit as the link function. Interaction effect between treatment assignment and assessment time points was calculated after adjustment for baseline item score; however, the actual overall type I error could be larger than estimated due to the multiple testing conducted in the study. Association of sexual function score with quality of relationship, body image, fear of sex, QOL(FACT-G), fear of recurrence, and pain severity (BPI) was explored using a linear mixed model to account for correlations among the longitudinal measurements, with adjustment for age, marital status, assessment times, and treatment assignment. Covariance of repeated measures among the same subject is assumed unstructured due to unequal spaced time points. The `empirical' variance is used in estimating precision of parameter estimates. Internal consistency of the new constructs were assessed with standardized Cronbach's coefficient alpha.

RESULTS

Eight hundred two eligible patients were enrolled on the LAP2 QOL component, of which 50 later declined. Of the 752 patients who participated, 361(48%) completed before-surgery self-report items addressing sexual function included within the QOL study survey, 297(40%) at 1 week post-surgery, 274(36%) at 3 weeks, 290(39%) at 6 weeks, and 306(41%) at 6 months postoperatively (Figure 1). Less than half (48% preop; 41% at 6 months) completed sexual function questions; therefore, caution should be taken in interpreting the results since it may only reflect a subset of the study sample.

Sexual Function Responders

Sexual function was explored among responders (including intermittent responders) and presented in Table 2. No statistical differences (p=0.08) between the open versus laparoscopic groups were detected in terms of postoperative sexual function scores after adjustment for baseline scores. During the QOL assessments, nearly 80% of the responders stated `sexual active during the past year'. After adjusting for the baseline scores, the patients in both groups reported the similar sexual function scores (p=0.09) regardless of the surgical procedures they had taken.

Table 2.

Sexual function among the responders (including intermittent responders) and those `sexual active'

| Among Responders | Among those `sexual active' | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope | Open | Scope | Open | |||||||||

| N | Mean | Std | N | Mean | Std | N | Mean | Std | N | Mean | Std | |

| Pre-surgery | 221 | 10.6 | 3.8 | 101 | 10.3 | 3.9 | 158 | 11.6 | 3.4 | 74 | 11.2 | 3.6 |

| 1 week post surgery | 140 | 7.0 | 3.8 | 79 | 7.4 | 3.8 | 111 | 7.1 | 4.0 | 58 | 7.6 | 4.0 |

| 3 weeks post surgery | 127 | 8.3 | 4.0 | 79 | 7.6 | 4.0 | 109 | 8.5 | 4.0 | 60 | 7.8 | 4.0 |

| 6 weeks post surgery | 149 | 10.3 | 4.1 | 84 | 9.0 | 4.1 | 124 | 10.9 | 3.8 | 64 | 9.7 | 4.1 |

| 6 months post surgery | 186 | 11.0 | 3.7 | 86 | 10.6 | 4.2 | 155 | 11.7 | 3.5 | 69 | 11.2 | 4.1 |

Among all of the patients who responded (both treatment arms), sexual function declined after surgery but recovered to preoperative levels by 6 months (see Table 3), Fear of sex increased in the immediate recovery period (1 week, x=2.4; 3 weeks, x=2.1) but declined by 6 months postoperatively (x=0.6).

Table 3.

Sexual function construct and other construct scores among responders

| Pre-surgery | 1 week post surgery | 3 weeks post surgery | 6 weeks post surgery | 6 months post surgery | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Std | N | Mean | Std | N | Mean | Std | N | Mean | Std | N | Mean | Std | |

| Sexual function | 322 | 10.5 | 3.8 | 219 | 7.1 | 3.8 | 206 | 8.0 | 4.0 | 233 | 9.8 | 4.2 | 272 | 10.9 | 3.9 |

| Quality of relationship | 317 | 10.1 | 2.6 | 213 | 9.4 | 2.6 | 204 | 9.8 | 2.6 | 230 | 10.0 | 2.6 | 271 | 10.2 | 2.4 |

| Body image | 321 | 12.7 | 4.0 | 214 | 18.4 | 4.4 | 204 | 20.4 | 4.5 | 230 | 21.5 | 4.4 | 266 | 22.6 | 4.1 |

| Fear of sex | 316 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 210 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 196 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 227 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 269 | 0.6 | 1.1 |

| QOL | 319 | 86.4 | 13.5 | 218 | 73.9 | 14.5 | 206 | 82.7 | 14.7 | 230 | 88.9 | 15.8 | 270 | 94.1 | 13.2 |

| Fear of cancer | - | - | - | 214 | 4.9 | 3.9 | 203 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 228 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 265 | 3.7 | 3.3 |

| Severity of pain | 305 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 212 | 7.8 | 4.8 | 201 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 225 | 2.5 | 3.7 | 264 | 1.3 | 2.8 |

The percentages of scaled categories reported for `body image' and `quality of relationship' items are summarized for responders to sexual functioning items and presented in Table 4. Differences were detected between the laparotomy and laparoscopy groups in those who completed sexual function items for physical appearance and/or femininity items. In sexual function responders, more laparoscopy patients indicated physical appearance as more important compared to laparotomy patients. Laparoscopy patients also had higher scores of satisfaction with stomach appearance (p=0.003) , overall appearance (p=0.002) , and in feeling like a woman (p<0.001) although the improvement over time was noted in both groups.

Table 4.

Body Image Construct and Quality of Relationship Construct Items by Randomized Surgical Groups

| Pre-Surgery | 1 week post surgery | 3 weeks post surgery | 6 weeks post surgery | 6 months post surgery | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Scope | Open | Scope | Open | Scope | Open | Scope | Open | Scope | Open | ||

|

|

|||||||||||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | *p-value | |

|

| |||||||||||

| My physical appearance is important to me | |||||||||||

| Not at all | 0.5 | . | . | 6.5 | 0.9 | . | . | . | 1.2 | . | |

| A little bit | 2.8 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 1.7 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 8.0 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 0.07 |

| Somewhat | 12.8 | 14.6 | 13.4 | 9.7 | 12.1 | 10.5 | 6.8 | 10.7 | 10.9 | 16.5 | |

| Quite a bit | 33.6 | 38.5 | 37.8 | 45.2 | 33.6 | 44.7 | 31.8 | 36.0 | 27.3 | 29.1 | |

| Very much | 50.2 | 42.7 | 44.9 | 35.5 | 51.7 | 40.8 | 59.1 | 45.3 | 58.8 | 51.9 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| I am satisfied with the way my stomach area looks | |||||||||||

| Not at all | 23.2 | 28.1 | 30.7 | 30.6 | 12.9 | 15.8 | 7.6 | 12.0 | 8.5 | 8.9 | |

| A little bit | 13.3 | 10.4 | 20.5 | 21.0 | 7.8 | 17.1 | 6.1 | 20.0 | 4.8 | 13.9 | 0.003 |

| Somewhat | 35.5 | 32.3 | 26.0 | 38.7 | 23.3 | 35.5 | 30.3 | 36.0 | 26.1 | 25.3 | |

| Quite a bit | 11.8 | 19.8 | 13.4 | 8.1 | 34.5 | 22.4 | 31.8 | 21.3 | 27.3 | 31.6 | |

| Very much | 16.1 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 1.6 | 21.6 | 9.2 | 24.2 | 10.7 | 33.3 | 20.3 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| I am satisfied with the way by body looks overall | |||||||||||

| Not at all | 10.0 | 14.6 | 14.2 | 16.1 | 5.2 | 13.2 | 5.3 | 9.3 | 3.0 | 3.8 | |

| A little bit | 14.2 | 14.6 | 17.3 | 22.6 | 9.5 | 14.5 | 6.8 | 21.3 | 7.9 | 15.2 | 0.002 |

| Somewhat | 37.4 | 42.7 | 39.4 | 38.7 | 30.2 | 35.5 | 28.8 | 34.7 | 32.1 | 32.9 | |

| Quite a bit | 22.7 | 20.8 | 18.9 | 21.0 | 38.8 | 31.6 | 40.2 | 24.0 | 34.5 | 32.9 | |

| Very much | 15.6 | 7.3 | 10.2 | 1.6 | 16.4 | 5.3 | 18.9 | 10.7 | 22.4 | 15.2 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| I am able to feel like a woman | |||||||||||

| Not at all | 2.4 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 12.9 | 0.9 | 3.9 | . | 4.0 | 0.6 | . | |

| A little bit | 2.4 | 2.1 | 9.4 | 14.5 | 6.0 | 13.2 | 2.3 | 6.7 | 2.4 | 5.1 | |

| Somewhat | 10.9 | 19.8 | 18.9 | 25.8 | 12.1 | 18.4 | 12.1 | 14.7 | 9.1 | 10.1 | 0.0003 |

| Quite a bit | 27.5 | 35.4 | 28.3 | 29.0 | 38.8 | 34.2 | 35.6 | 45.3 | 25.5 | 36.7 | |

| Very much | 56.9 | 41.7 | 40.2 | 17.7 | 42.2 | 30.3 | 50.0 | 29.3 | 62.4 | 48.1 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| I feel sexually attractive | |||||||||||

| Not at all | 10.4 | 14.6 | 30.7 | 41.9 | 11.2 | 23.7 | 8.3 | 14.7 | 7.3 | 11.4 | |

| A little bit | 10.4 | 15.6 | 15.7 | 14.5 | 19.8 | 18.4 | 11.4 | 18.7 | 9.7 | 12.7 | |

| Somewhat | 28.9 | 34.4 | 36.2 | 22.6 | 33.6 | 31.6 | 28.0 | 33.3 | 26.1 | 30.4 | 0.28 |

| Quite a bit | 29.4 | 22.9 | 10.2 | 11.3 | 19.0 | 14.5 | 27.3 | 22.7 | 30.3 | 25.3 | |

| Very much | 20.9 | 12.5 | 7.1 | 9.7 | 16.4 | 11.8 | 25.0 | 10.7 | 26.7 | 20.3 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| I feel close to my partner | |||||||||||

| Not at all | 0.9 | . | 0.8 | 3.2 | 1.7 | 3.9 | 0.8 | . | 3.0 | 3.8 | |

| A little bit | 1.4 | 1.0 | . | 3.2 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 6.7 | 1.2 | 1.3 | |

| Somewhat | 5.7 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 3.2 | 5.2 | 3.9 | 6.8 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 0.53 |

| Quite a bit | 12.3 | 16.7 | 17.3 | 16.1 | 11.2 | 13.2 | 11.4 | 17.3 | 16.4 | 19.0 | |

| Very much | 79.6 | 77.1 | 76.4 | 74.2 | 80.2 | 77.6 | 78.0 | 73.3 | 75.8 | 72.2 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| I am able to express affection to my partner | |||||||||||

| Not at all | 4.3 | 3.1 | 3.9 | 6.5 | 3.4 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 2.7 | 4.2 | . | |

| A little bit | 5.7 | 7.3 | 9.4 | 17.7 | 5.2 | 9.2 | 5.3 | 10.7 | 4.2 | 8.9 | |

| Somewhat | 13.3 | 13.5 | 15.0 | 19.4 | 15.5 | 15.8 | 7.6 | 16.0 | 7.9 | 12.7 | 0.02 |

| Quite a bit | 19.9 | 34.4 | 22.8 | 32.3 | 27.6 | 36.8 | 23.5 | 30.7 | 28.5 | 25.3 | |

| Very much | 56.9 | 41.7 | 48.8 | 24.2 | 48.3 | 32.9 | 58.3 | 40.0 | 55.2 | 53.2 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| My partner is able to express affection to me | |||||||||||

| Not at all | 3.8 | 6.3 | 3.9 | 6.5 | 2.6 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 2.7 | 4.8 | . | |

| A little bit | 3.8 | 8.3 | 3.9 | 6.5 | 1.7 | 6.6 | 2.3 | 8.0 | 4.2 | 5.1 | |

| Somewhat | 10.4 | 8.3 | 16.5 | 21.0 | 12.9 | 10.5 | 6.1 | 10.7 | 6.1 | 8.9 | 0.41 |

| Quite a bit | 21.8 | 34.4 | 22.8 | 30.6 | 28.4 | 36.8 | 23.5 | 30.7 | 23.0 | 24.1 | |

| Very much | 60.2 | 42.7 | 52.8 | 35.5 | 54.3 | 40.8 | 62.9 | 48.0 | 61.8 | 62.0 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| I am afraid to have sex | |||||||||||

| Not at all | 57.6 | 62.6 | 22.2 | 20.2 | 18.0 | 21.6 | 37.9 | 34.1 | 69.7 | 69.0 | |

| A little bit | 11.5 | 21.2 | 9.6 | 10.7 | 18.0 | 17.6 | 27.6 | 26.8 | 11.9 | 14.3 | |

| Somewhat | 16.1 | 4.0 | 11.1 | 20.0 | 23.8 | 17.6 | 20.0 | 15.9 | 10.3 | 8.3 | 0.9 |

| Quite a bit | 3.7 | 1.0 | 12.6 | 9.3 | 13.1 | 13.5 | 6.9 | 7.3 | 5.4 | 4.8 | |

| Very much | 11.1 | 11.1 | 44.4 | 40.0 | 27.0 | 29.7 | 7.6 | 15.9 | 2.7 | 3.6 | |

Note: Scope refers to the laparoscopic surgical group and Open - refers to the laparotomy surgical group.

p-values for treatment difference over time using generalized estimating equation approach with the cumulative logit as the link function. The baseline item score was included as a covariate. .

The quality of relationship, body image, fear of sex, QOL(FACT-G), fear of recurrence, and pain severity(BPI) reported by the responders to sexual functioning questions were also explored using a linear mixed model, with adjustment for age, marital status, assessment time points, and treatment assignment. The fitted mixed model suggests that sexual function are positively associated with better quality of relationship (p<0.001), body image (p<0.001) , or QOL as measured with FACT-G (p<0.001) , and, negatively with the fear of sex (p<0.001).

Exploratory Analysis of Response Patterns

693 out of 752 QOL participants answered the FACT-G item “Have you been sexually active during the past year?” within the QOL survey. At preoperative assessment, 39% (n=267) reported being sexually active and the majority were married (85%, n=220) or under 69 years of age. Sexually active women were more likely to respond to sexual function items (95%, n=253);cart however, 39% (n=166) of sexually inactive women did respond (including intermittent) to sexual function items.

Based on response pattern definitions to sexual function items, 225 patients responded to sexual function items whenever they completed the QOL assessments (responder), 224 responded intermittently to sexual function items (intermittent responder), and 303 never answered sexual function items despite responding to other QOL questions (non-responders). Group characteristics are presented in Table 5. Younger (P<0.001) or married (P<0.001) patients were more likely to respond. Responders (including intermittent) also indicated feeling more close to their partners (P<0.001) than non-responders. No significant differences were noted between response patterns by treatment (laparotomy vs laparoscopy), race, disease stage, or education.

Table 5.

Patient Characteristics

| Non-responder N=303 | Intermittent responder N=224 | Responder N=225 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

|

| ||||||

| Randomized group | ||||||

| Laparoscopy (scope) | 207 | 68.3 | 148 | 66.1 | 153 | 68.0 |

| Laparotomy (open) | 96 | 31.7 | 76 | 33.9 | 72 | 32.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Age * | ||||||

| ≤ 39 | 6 | 2.0 | 3 | 1.3 | 11 | 4.9 |

| 40–49 | 14 | 4.6 | 8 | 3.6 | 43 | 19.1 |

| 50–59 | 53 | 17.5 | 55 | 24.6 | 87 | 38.7 |

| 60–69 | 96 | 31.7 | 85 | 37.9 | 57 | 25.3 |

| 70–79 | 96 | 31.7 | 63 | 28.1 | 26 | 11.6 |

| > 80 | 38 | 12.5 | 10 | 4.5 | 1 | 0.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| Black | 14 | 4.6 | 14 | 6.3 | 4 | 1.8 |

| White | 264 | 87.1 | 193 | 86.2 | 208 | 92.4 |

| Other | 25 | 8.2 | 17 | 7.6 | 13 | 5.8 |

|

| ||||||

| Marital Status * | ||||||

| Unknown | 24 | 7.9 | 5 | 2.2 | 5 | 2.2 |

| Married | 66 | 21.8 | 174 | 77.7 | 193 | 85.8 |

| Widowed | 110 | 36.3 | 24 | 10.7 | 6 | 2.7 |

| Separated/divorced | 61 | 20.1 | 13 | 5.8 | 13 | 5.8 |

| Single | 42 | 13.9 | 8 | 3.6 | 8 | 3.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| Unknown | 25 | 8.3 | 8 | 3.6 | 10 | 4.4 |

| 1–11 years of education | 47 | 15.5 | 33 | 14.7 | 16 | 7.1 |

| High school graduate | 93 | 30.7 | 71 | 31.7 | 61 | 27.1 |

| Some college | 78 | 25.7 | 67 | 29.9 | 71 | 31.6 |

| Bachelor's degree | 33 | 10.9 | 25 | 11.2 | 41 | 18.2 |

| Graduate/professional degree | 27 | 8.9 | 20 | 8.9 | 26 | 11.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Surgical stage | ||||||

| Unstaged | 2 | 0.7 | 4 | 1.8 | 6 | 2.7 |

| IA | 103 | 34.0 | 72 | 32.1 | 103 | 45.8 |

| IB | 84 | 27.7 | 64 | 28.6 | 57 | 25.3 |

| IC | 50 | 16.5 | 32 | 14.3 | 18 | 8.0 |

| IIA | 10 | 3.3 | 8 | 3.6 | 10 | 4.4 |

| IIB | 15 | 5.0 | 5 | 2.2 | 8 | 3.6 |

| IIIA | 9 | 3.0 | 11 | 4.9 | 9 | 4.0 |

| IIC | 22 | 7.3 | 21 | 9.4 | 12 | 5.3 |

| IVB | 8 | 2.6 | 7 | 3.1 | 2 | 0.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Feel close to partner (at baseline) * | ||||||

| Unknown | 92 | 30.4 | 23 | 10.3 | 6 | 2.7 |

| Not at all | 17 | 5.6 | 3 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.9 |

| A little bit | 8 | 2.6 | 4 | 1.8 | 3 | 1.3 |

| Somewhat | 12 | 4.0 | 12 | 5.4 | 12 | 5.3 |

| Quite a bit | 36 | 11.9 | 30 | 13.4 | 29 | 12.9 |

| Very much | 138 | 45.5 | 152 | 67.9 | 173 | 76.9 |

P<0.001

DISCUSSION

This ancillary data analysis examined specific items of sexual difficulties in endometrial cancer patients enrolled in LAP2 and potential factors contributing to response patterns to these items. By reconceptualizing the QOL data by content domains we were able to develop constructs of sexual function, quality of relationships, body image, and fear of sex, and closely examine response patterns (non-responders, intermittent responders, and responders) not explained within this sample.

In responders to sexual function items within the LAP2 QOL survey, sexual difficulties were associated with greater fear of sex and a poorer quality of relationship. Women experiencing vaginal discomfort may develop fear of sex due to pain, particularly if open communication is lacking in one's relationship. However, discussing sexual changes or difficulties can be challenging as misperceptions have been noted among couples. A recent study found female cancer survivors experienced greater vaginal changes and dryness than what was perceived by their partners.26 In our sample, more responders (including intermittent responders) felt very close to their partners, highlighting that connection (or quality) may be essential in coping with sexual difficulties. Of note, ~30% of non-responders did not provide feedback about their partner; therefore, it is hard to differentiate whether the lack of response to sexual function items was associated with a poor quality relationship or whether it was more of a reflection of being without a partner. Our findings also suggest age, body image, and relationship quality and pain may place women surgically treated for endometrial cancer at higher risk for sexual difficulties. Psychological and sexual morbidity connected with gynecologic cancer12,13 both in the immediate post-treatment period4,14,16 and in long-term survivorship.7,18 has been described in the literature. Despite the noted difficulties within our sample, improvement in sexual function and decreased fear of sex was seen by 6 months post surgery in those who responded to sexual function items.

Our assumption that the lack of a sexual partner might have contributed to decreased compliance to sexual function survey items was consistent with the findings. Over two-thirds (70%) of the non-responders were single, widowed or divorced, so many women may have felt these items were not applicable to them. Future studies should include screener items to elicit this information clearly so assumptions or post-hoc analyses do not have to be made. Age was also an important factor in whether women completed the sexual function items or were sexually active. The importance of sexuality has been noted to vary among women with a gynecologic cancer history. Some studies report rates of sexual activity from 10–50% in older ovarian cancer patients,10,27 whereas rates of 77–81% have been reported in younger cohorts of gynecologic cancer patients.15,28 Sexual inactivity may also be related to the physical health of a partner27,29 or contingent upon the quality of the relationship.26 Interestingly, despite being sexually inactive, 39% of patients provided answers to sexual function items.

Although no significant differences were noted between the groups, these results suggest that minimally invasive surgery may not differ from laparotomy regarding resumption of or improvements in sexual function postoperatively. However, laparoscopic patients were more satisfied with their appearance and femininity overall. Both groups, however, demonstrated improvement in these areas over their recovery process, which could reflect adjustment to their cancer experience with improvement in function, the establishment of a “new norm,” or experiencing a response shift, defined as a reprioritization of life goals as one adapts to a new health status.30 Of note, fear of cancer also followed the same pattern.

We recognize the limitations of this study, which conducted a post-hoc analysis with a small sample of participants who provided responses to sexual function items. The sexual functioning items were included in the design of the LAP2 study, however, they were not evaluated in the final analysis due to the insufficient compliance to these items. Although the low compliance didn't warrant the evaluation on the effect of surgical techniques on sexual functioning, the information provided by responders are still valuable and might reveal some insights on the sexual functioning that are worthy to look into in future research. This exploratory analysis, therefore, is reflective of only a subset (<50%) of the entire QOL study sample; and conclusive statements based on the results and P values should be reached cautiously. Regardless, our study reinforces the importance of not making assumptions about missing data or lack of responses as a proxy for sexual activity/function and provides insight for formulating future study designs and resources for gynecologic cancer patients. Women with a poorer body image or greater fear of sex appeared to be at higher risk of sexual dysfunction and could benefit from psychosocial support. Psychoeducational interventions have been shown to have a positive effect on sexual function, satisfaction, and overall well-being.31 Simple screener questions and/or preoperative counseling could also positively impact patient outcomes of sexual function and QOL by preparation or early identification of difficulties. Women struggling with the quality of their relationships preoperatively could be at risk for sexual morbidity following surgical intervention and would be an ideal target for development of a future couple interventions.

As more women survive cancer due to medical advancement, so too should the field continue to move forward with strategies for enhanced QOL. Sexual function is important to many female cancer patients/survivors, yet without an accurate understanding or assessment of risk factors, progress cannot be made in improving outcomes and treating these issues. Future studies should incorporate appropriate questions to accurately screen participants, and for appropriate interpretation of sexual activity rates. Prospective clinical trials are needed and should include comprehensive empirical measures of sexual function, such as PROMIS-SxF (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Sexual Function), in addition to items to identify possible response shifts when examining the impact of other cancer treatments.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Cancer Institute grants to the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) Administrative Office (CA 27469) and the GOG Statistical and Data Center (CA 37517). The following GOG institutions participated in the GOG 2222 (LAP2):

Abington Memorial Hospital, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, University of Minnesota Medical School, University of Mississippi Medical Center, University of Pennsylvania Cancer Center, University of California at San Diego, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Indiana University School of Medicine, University of California Medical Center at Irvine, Tufts-New England Medical Center, Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke's Medical Center, University of New Mexico, The Cleveland Clinic Foundation, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Washington University School of Medicine, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Columbus Cancer Council, MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Women's Cancer Center, University of Oklahoma, Tacoma General Hospital, Tampa Bay Cancer Consortium, Gynecologic Oncology Network, Fletcher Allen Health Care, University of Wisconsin Hospital, Women and Infants Hospital, and CCOP.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer Statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, et al. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, et al. Laparoscopy compared with laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group study LAP2. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5331–5336. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kornblith AB, Huang HQ, Walker JL, et al. Quality of life of patients with endometrial cancer undergoing laparoscopic international federation of gynecology and obstetrics staging compared with laparotomy: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5337–5342. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, et al. Recurrence and survival after random assignment to laparoscopy versus laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group LAP2 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:695–700. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8645. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindau ST, Schumm P, Laumann, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. NEJM. 2007;357:762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shifren JL, Monz B, Russo PA, et al. Sexual problems and distress in United States women. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:970–978. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181898cdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trompeter SE, Bettencourt R, Barett-Connor E. Sexual activity and satisfaction in healthy community-dwelling older women. Am J Med. 2012;125:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matulonis UA, Kornblith A, Lee H, et al. Long-term adjustment of early stage ovarian cancer survivors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:1183–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Likes WM, Stegbauer C, Tillmanns T, et al. Correlates of sexual function following vulvar excision. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:600–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carpenter KM, Fowler JM, Maxwell GL, et al. Direct and buffering effects of social support among gynecologic cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med. 2010;39:79–90. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9160-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levin AO, Carpenter KM, Fowler JM, et al. Sexual morbidity associated with poorer psychological adjustment among gynecologic cancer survivors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:461–470. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181d24ce0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le T, Menard C, Samant R, et al. Longitudinal assessments of quality of life in endometrial cancer patients: effects of surgical approach and adjuvant radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:795–802. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter J, Sonoda Y, Baser RE, et al. A 2-year prospective study assessing the emotional, sexual and quality of life concerns of women undergoing radical trachelectomy versus radical hysterectomy for treatment of early-stage cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119:358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter J, Chi DS, Brown CL, et al. Cancer-related Infertility in survivorship. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:2–8. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181bf7d3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindau ST, Gavrilova N, Anderson D. Sexual morbidity in very long-term survivors of vaginal and cervical cancer: a comparison to national norms. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canada AL, Schover LR. The psychological impact of interrupted childbearing in long-term female cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2012;21:134–143. doi: 10.1002/pon.1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juraskova I, Butow P, Bonner C, et al. Sexual adjustment following early stage cervical and endometrial cancer: prospective controlled multi-centre study. Psychooncology. 2011 doi: 10.1002/pon.2066. DOI:10.1002/pon.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juraskova I, Butow P, Robertson R, et al. Post-treatment sexual adjustment following Cervical and endometrial cancer: a qualitative insight. Psychooncology. 2003;12:267–279. doi: 10.1002/pon.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onujiogu N, Johnson T, Seo S, et al. Survivors of endometrial cancer: who is at risk for sexual dysfunction. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:356–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen PT, Groenvold M, Klee MC, et al. Longitudinal study of sexual function and vaginal changes after radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:937–949. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00362-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaz AF, Pinto-Neto AM, Conde DM, et al. Quality of life and menopausal and sexual symptoms in gynecologic cancer survivors: a cohort study. Menopause. 2011;18:662–669. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181ffde7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van de Poll-Franse LV, Mols F, Essink-Bot ML, et al. Impact of external beam adjuvant radiotherapy on health-related QOL for long-term survivors of endometrial adenocarcimoma: a population-based study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nout RA, Putter H, Jurgenliemk-Schulz IM, et al. Five-year quality of endometrial cancer patients treated in the randomized Post Operative radiation therapy in Endometrial Cancer (PORTEC-2) trial and comparison with norm data. Eur J Cancer. 2011 Dec 14; doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.014. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stafford L, Judd K. Partners of long-term gynecologic cancer survivors: psychiatric morbidity, psychosexual outcomes and supportive needs. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;118:268–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carmack Taylor CL, Basen-Engquist K, Shinn EH, et al. Predictors of sexual functioning in ovarian cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:881–889. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenwald HP, McCorkle R. Sexuality and sexual function in long-term survivors of cervical cancer. J Womens Health. 2008;17:955–963. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greimel ER, Winter R, Kapp KS, et al. Quality of life and sexual functioning after cervical cancer treatment: a long-term follow-up study. Psychooncology. 2009;18:476–482. doi: 10.1002/pon.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rapkin BD, Schwartz CE. Toward theoretical model of quality-of-life appraisal: Implications of findings from studies of response shift. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:14. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brotto LA, Heiman JR, Goff B, et al. A psychoeducational intervention for sexual dysfunction in women with gynecologic cancer. Arch Sex Behav. 2008;37:317–329. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]