Abstract

Class O forkhead box (FOXO) transcription factors are downstream targets of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, which is upregulated in many tumors. AKT phosphorylates and inactivates FOXO1 by relocating it to the cytoplasm. Because FOXO1 functions as a tumor suppressor by negatively regulating cell-cycle progression and cell survival, compounds that promote FOXO1 localization to the nucleus might have therapeutic value in oncology. Here we describe the identification of such compounds by using an image-based, high content screen. Compounds that were active in retaining FOXO1 in the nucleus were tested to determine their pathway-specificity and isoform-specificity by using high content assays for Rev and FOXO3, respectively.

Keywords: high content screening, FOXO1, AKT, FOXO3

INTRODUCTION

Class O forkhead box (FOXO) transcription factors are a highly regulated family of proteins that act in a number of essential roles, including cell-cycle progression, metabolism, apoptosis, and stress resistance. FOXO proteins may also play roles in tumorigenesis because a number of human cancers have chromosomal translocations that involve FOXO.1 These translocations result in chimeric transcription factors composed of the activation domain of FOXO and the DNA-binding domain of another transcription factor (e.g., that of PAX3 or PAX7 for FOXO1 and that of MLL for FOXO3 and FOXO4).2–4 These gross mutations lead to partial loss of FOXO and changes in transcriptional profiles, either of which may contribute to tumorigenesis.

By inhibiting cell cycle progression and/or initiating apoptosis, FOXOs are able to regulate cell proliferation. FOXOs regulate cell cycle progression by inducing cell cycle arrest at the G1/S transition of the cell cycle, either through their target genes p27KIP1 and the Rb family member p130,5,6 or by repressing the expression of cyclins D1 and 2.7,8 To trigger apoptosis, active FOXO transcription factors must localize to the nucleus, where they can transactivate the Bcl-2 family member Bim, Fas ligand, and BCL-6.9,10 The roles of FOXOs in controlling the cell cycle and triggering apoptosis are especially relevant to cancer and suggest that FOXOs may be suitable anti-cancer therapeutic targets.

FOXO transcription factors are subject to extensive regulation through post-translational modification. Most notably, the PI3K-AKT pathway negatively regulates FOXOs via phosphorylation at three highly conserved AKT sites, corresponding to Thr24, Ser256, and Ser319 in human FOXO1.11 Once FOXOs are phosphorylated by AKT, they associate with 14-3-3 proteins, resulting in decreased DNA binding and translocation from the nucleus to cytoplasm via CRM1.11 Individual FOXOs are also substrates for CK1, DYRK, SGK, CDK2, IKKB, JNK, cGK1, and MST1.12 Interestingly, phosphorylation of FOXO by MST1 results in lowered affinity for 14-3-3 proteins and promotes retention of FOXO in the nucleus.13

FOXO members are also subject to methylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination. FOXO1 is methylated by PRMT1, which appears to antagonize mouse FOXO1 phosphorylation by AKT at Ser253 (corresponding to Ser256 of human FOXO1).14 FOXO turnover is due to ubiquitination by SCF via interaction of FOXO and Skp2. The ubiquitinated FOXO is then degraded by the proteasome. Acetylation of FOXO by CBP and/or PCAF is counterbalanced by the deacetylase Sirt1. Acetylation is generally believed to downregulate FOXO, however this question is still under investigation and discussion.12

One of the most obvious ways to regulate transcription factors such as FOXO1 is by transporting them from the cytoplasm across the nuclear membrane and thus bringing them closer to their target genes in the nucleus. Therefore, we used an image-based assay to identify small molecules that increased the number of FOXO1 molecules in the nucleus. Of approximately 17,000 compounds tested in the primary screen, 96 were selected for further validation and specificity testing by testing them against FOXO3, another member of the FOXO family of transcription factors, and the unrelated Rev protein. Selected compounds showing specificity for FOXO1, FOXO3, or both, with respect to Rev, were ordered as fresh powder and their activities re-tested. Maintenance of FOXO activity by its accumulation in the nucleus leads to tumor suppression.13 Elucidating the proteins and pathways targeted by these compounds will provide new insight into FOXO regulation and potentially reveal new anti-cancer therapeutic targets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and cell culture

U2OS cells stably expressing FOXO1-GFP, FOXO3-GFP, or Rev-GFP (hereafter referred to as U2OS/FOXO1-GFP, U2OS/FOXO3-GFP, and U2OS/Rev-GFP, respectively) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Lafayette, CO) and cultured according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Minimum Essential Medium + Glutamax (Invitrogen; Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone; Logan, UT), 0.5 mg/mL Geneticin (Invitrogen), 100 IU/mL penicillin (Invitrogen), and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen) and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. For passage or cell seeding onto assay plates, cells were detached from T75 flasks (Corning; Corning, NY) by using 0.05% trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen).

Nuclear translocation assay

The assay protocol is outlined in Table 1. Compounds were screened by using an integrated screening system constructed by HighRes Biosolutions (Woburn, MA) that had an integrated Matrix Wellmate microplate dispenser (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Matrix products; Hudson, NH) to dispense reagents, and a Pin Tool (HighRes Biosolutions) with surface-coated pins (V & P Scientific; San Diego, CA) to transfer compounds. The integrated system also included a microplate orbital shaker (Big Bear Automation; Santa Clara, CA), a V-Spin plate centrifuge (Agilent Automation Solutions; Santa Clara, CA), Liconic STR plate incubators (LiCONiC Instruments; Boston, MA), a plate washer (BioTek; Winooski, VT), an EnVision plate reader (PerkinElmer; Waltham, MA) to measure luminescent signals, a CellWoRx automated fluorescence imager (Applied Precision; Issaquah, WA) to acquire images, and robot arms (Staübli; Duncan, SC) to transfer plates from instrument to instrument. Cells were seeded into black, clear-bottom, tissue–culture treated, 384-well plates (Corning) at a density of 2,000 cells per well in 50 μL growth medium. Plates were then briefly vortexed and centrifuged to aid with both the release of trapped air bubbles and facilitate the even dispersion of cells within each well. The cells were allowed to attach and grow overnight in a Liconic STR240 incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2, 95% relative humidity.

Table 1.

Nuclear Translocation Assay Protocol

| Step No. | Action | Value | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Plate cells | 50 μl | 2,000 U2OS cells expressing appropriate GFP- fusion protein |

| 2 | Vortex plate | 10 sec | Aids release of bubbles trapped at well’s bottom |

| 3 | Centrifuge plate | 10 sec | Aids release of bubbles trapped at well’s bottom and attachment of cells to well’s bottom |

| 4 | Incubate cells | 16–18 hrs | 37°C, 5% CO2 in Liconic incubator |

| 5 | Add control compounds | 65 nL | Wortmannin and leptomycin B in DMSO |

| 6 | Add library compounds | 65 nL | 13 μM final concentration |

| 7 | Incubate cells | 1 hr | 37°C, 5% CO2 in Liconic incubator |

| 8 | Fix cells and stain nuclei | 25 μL | 3.7% (final) formaldehyde and 1 μg/mL (final) Hoechst dye |

| 9 | Vortex plate | 10 s | Evenly mix DNA dye |

| 10 | Centrifuge plate | 10 s | Aids release of bubbles trapped at well’s bottom |

| 11 | Incubate | 15 min | Ambient conditions |

| 12 | Wash | 50 μL | 3 PBS washes |

| 13 | Seal plate | 171°C | Easy-peel foil seal applied to each plate top |

| 14 | Image acquisition | Hoechst: 360/460 nm GFP: 480/530 nm |

1 field per well; autofocus; CCD imager |

| 15 | Image analysis | Cell Analysis Tool in Cellomics Toolbox software |

The next day, control compounds and test compounds were added by pin transfer. Each transfer of compound (65 nL) from the stock plates to the assay plate resulted in a final concentration of 13 μM (0.13% final DMSO concentration). Plates were incubated for 1 hr before 25 μl of fix + stain solution was added to each well. Fix + stain solution contained 11.1% formaldehyde and 3 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich; St Louis, MO) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) adjusted to pH 7.2, giving a final concentration of 3.7% formaldehyde and 1 μg/mL Hoechst dye in the assay plate. Cells were incubated in fix + stain solution at room temperature for 30 min. Plates were then washed 3 times with PBS and sealed with easy-peel foil using a plate sealer (Agilent Automation Solutions; Santa Clara, CA).

Images were acquired by using a CellWoRx automated fluorescence imager using a 10x objective lens. Image acquisition began immediately and continued for up to 20 hours per screening run (each plate was imaged for approximately 30 min and the largest screening run contained 40 plates). GFP and Hoechst signals were stable during the entire image acquisition period (see RESULTS section). One field in the center of each well was selected and imaged through both blue and green channels, yielding 768 images per plate. Because resolution was of secondary concern, 2 × 2 pixel binning was utilized to reduce file size, increase signal intensity, and slightly shorten image-acquisition time.

Image and data analysis

All image analysis was performed using the Cell Analysis Tool within the ThermoFisher Cellomics vHCS Toolbox (Pittsburgh, PA). For each field, the Hoechst staining of DNA was used to define the nucleus, and a ring concentric to the nucleus was used to define a cytoplasmic region of the cell. The inner diameter of the ring was created by dilating the nuclear circle by 1 pixel on each side, and the thickness of the ring was 3 pixels. For each cell, the GFP’s fluorescence intensity in the nuclear circle and cytoplasmic ring was measured and divided by the respective area of the cell to yield the average fluorescence intensity for each region. We evaluated nuclear GFP intensity alone, the ratio of nuclear-to-cytoplasmic GFP fluorescence intensity, and the difference between cytoplasmic and nuclear GFP fluorescence intensity (i.e., Nuc – Cyto) and found that the (Nuc – Cyto) method yielded the most consistent results (data not shown). Therefore, (Nuc – Cyto) was used to quantitate nuclear localization. Most fields contained 500–1000 cells; fields containing fewer than 50 cells were not considered for analysis.

Data output from Cellomics was reformatted and analyzed using RISE software as previously described.15 All data were normalized to intraplate controls to determine the percent of activity. Interplate and intraplate variation and patterning were monitored for quality-control purposes during each screening run.

For analysis of individual cell responses as a function of their location in the well, 4 adjacent images were acquired, covering the entire well surface area. The nuclear localization (Nuc-Cyto) and position were recorded for each cell in the image. These data were analyzed in Spotfire (Somerville, MA) to create a visualization illustrating both the position and FOXO-GFP localization on a cell-by-cell basis. Data from three identically treated wells were aggregated for Fig. 3d.

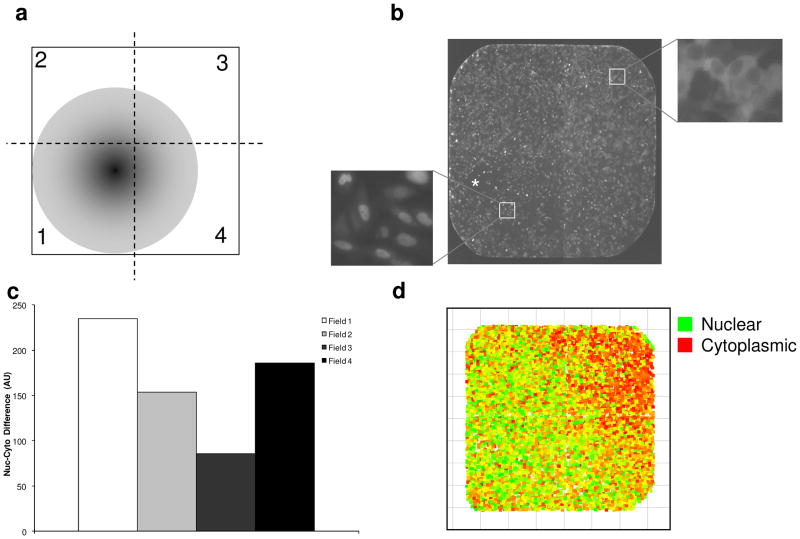

FIG. 3.

Compound gradient causes variable response within each well. (a) Diagram of a single well illustrating how delivery of compound to a single point might cause a concentration gradient in the well. Dashed lines divide the well into 4 quadrants. (b) Montage of four images that together cover an entire single well of U2OS/FOXO1-GFP cells treated with wortmannin. Cells near the point of compound delivery (asterisk; lower left quadrant) show a greater response than cells in distal regions of the well (see insets). (c) The response to a low concentration of wortmannin (0.5 nM) (expressed as Nuc-Cyto) was calculated for each of the four quadrants of the well. AU, arbitrary unit. (d) FOXO1 nuclear translocation for individual cells relative to their position in the well. Each square represents the position of the cell within the well and color indicates the nuclear (green) or cytoplasmic (red) localization for each cell.

Oxidative stress assay

Cells were plated and treated with compounds as described for the nuclear translocation assay. After 30 minutes of incubation with the test compound, dihydroethidium (DHE) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each well, and cells were incubated for an additional 30 minutes. Fix + stain solution was then added to each well (as described above), and the plate was washed with PBS and sealed before imaging to detect Hoechst staining and ethidium intensity in the nucleus. Image analysis was performed by measuring the average nuclear ethidium signal per cell in each field.

Dose-response analysis

Compounds were arrayed into 384-well plates in either 1:2 or 1:3 series dilution steps, as specified. The highest concentration tested was 100 μM (final concentration in assay well). Compounds were tested in triplicate to generate variable-slope, sigmoidal dose-response curves by using GraphPad’s Prism 4 software (La Jolla, CA).

Luciferase reporter assay

We used Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics) according to the supplier’s recommendations to transfect 50% confluent T75 flasks of U2OS/FOXO1-GFP cells with a reporter plasmid (6 μg) containing 3 tandem repeats of the insulin response sequence (3×IRS) upstream of the firefly luciferase gene (3×IRS-luc).16 After overnight incubation, cells were trypsinized, counted, and plated to 384-well, white, clear-bottom, tissue culture–treated microplates (Corning) (8,000 cells in 25 μL media per well). Compounds were added by pin tool, as described before, and incubated for 4 hours, unless otherwise noted. After incubation, plates were cooled to room temperature before 25 μL of HTS Steady-lite (Perkin Elmer) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for an additional 15 minutes. Luminescence was then measured by using an Envision plate reader (Perkin Elmer), and data were normalized to in-plate controls.

Compound libraries tested

Two sub-libraries of the St. Jude compound collection were included in the primary screen. The first collection (i.e., bioactive compound library) consists of 5,600 compounds (approximately 3,200 unique) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Microsource (Gaylordsville, CT), and Prestwick (Illkirch, France) chemical companies. This library contained chemicals, including some U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs, with previously described biological activity. The second collection consisted of 13,000 predicted kinase inhibitors purchased from ChemBridge (San Diego, CA). Random sampling of compounds for quality-control purposes showed that they were, on average, more than 95% pure (data not shown). Additional information about the compounds screened is available upon request. Hit compounds were reordered in powder form and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for secondary screening.

All compounds were dissolved in DMSO at 10 mM and stored at −20°C before screening. Compounds were arrayed in 384-well polypropylene plates; columns 1, 2, 13, and 14 were left empty for controls.

RESULTS

FOXO1 nuclear translocation assay

To identify chemical regulators of FOXO1, we developed an image-based, high content assay to measure the nuclear translocation of FOXO1-GFP in U2OS cells. The functionality of FOXO1-GFP was tested by comparing the activation of a FOXO1-responsive luciferase reporter (3×IRS-luc) in U2OS cells with or without FOXO1-GFP. Cells expressing FOXO1-GFP showed higher luciferase activity (data not shown) suggesting that FOXO1-GFP is functional.

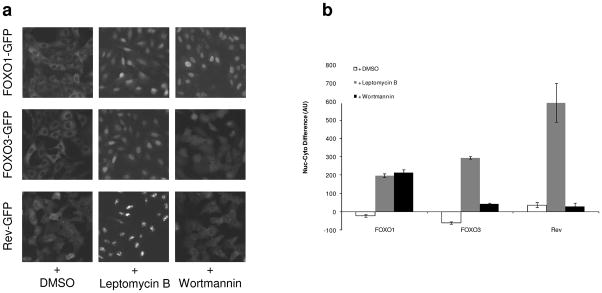

Under normal growth conditions, FOXO1-GFP was primarily located in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1a). During assay development and screening, 2 positive-control compounds were used to enrich FOXO1-GFP in the nucleus (Fig. 1a). First, wortmannin, a potent inhibitor of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), was used to determine the level of nuclear localization in response to small molecules acting upstream of FOXO1. Second, leptomycin B, an inhibitor of Exportin1 (CRM1)-dependent nuclear export, was used to determine the level of FOXO1 that might accumulate in the nucleus in response to compounds non-specific for the FOXO1 pathway. For FOXO1, the results from both control compounds were similar (Fig. 1b).

FIG. 1.

Nuclear translocation of FOXO1, FOXO3, and Rev. (a) Representative images of U2OS cells stably expressing FOXO1-GFP, FOXO3-GFP, or Rev-GFP treated as indicated. (b) The difference in GFP intensity between the nucleus and the cytoplasm (i.e., Nuc-Cyto). Cells were treated with DMSO, Wortmannin (100 nM) or Leptomycin B (10 μM) as indicated for 60 min before fixation. The values represent the average of 8 wells; error bars denote the standard deviation. AU, arbitrary unit.

To address the specificity of compounds affecting FOXO1 nuclear translocation, we used U2OS cell lines stably expressing GFP fusions to either another FOXO family member, FOXO3, or to the unrelated Rev protein, an RNA-binding HIV-1 regulatory protein. FOXO3 is regulated by many of the same upstream regulatory pathways that regulate FOXO1, but comparison of response in these 2 cell lines allowed us to determine if any compounds preferentially increased FOXO1 levels in the nucleus. Similar to FOXO1 and FOXO3, Rev contains nuclear localization signal and nuclear export signal sequences and shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, however Rev nuclear import/export is not regulated by the PI3K/Akt pathway like FOXO1 and FOXO3. Therefore, small molecules affecting FOXO1, FOXO3, and Rev localization are likely acting through a nonspecific mechanism (e.g., inhibiting the CRM1 nuclear-export machinery), and compounds affecting only FOXO1 and FOXO3 are more likely acting on a target upstream of those proteins. All 3 cell lines were tested using wortmannin and leptomycin B to measure their response to small-molecule treatment (Fig. 1a). As expected, FOXO1-GFP and FOXO3-GFP nuclear localization was increased by treatment with either positive-control compound, and Rev-GFP nuclear localization was increased only by treatment with leptomycin B (Fig. 1b).

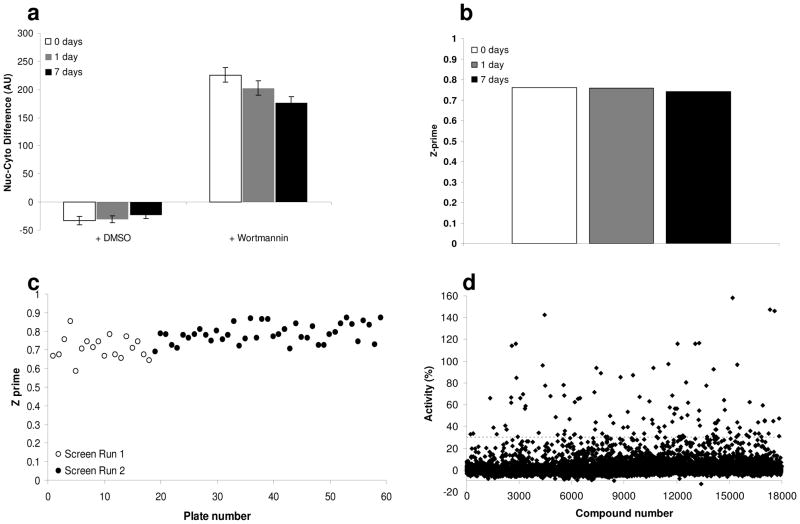

Primary screening

Screening took place during 2 independent screening runs for the 2 sub-libraries tested. Average throughput for each assay was approximately 10 plates per hour and approximately 2 plates per hour for image acquisition. Because imaging throughput was so much lower than that of the rest of the assay, GFP signal stability was tested directly to ensure that there was no significant fluorescence degradation as plates were queued for imaging. Images of positive and negative control treated wells were acquired immediately, and after one or 7 days of storage at room temperature. The difference between nuclear and cytoplasmic signal changed slightly over time, but the Z prime (Z’) was consistently high (Figs. 2a and 2b). During high-throughput screening, Z’ based on DMSO as the negative control (low signal) and wortmannin as the positive control (high signal) was consistently high throughout the runs (Fig. 2c). The percent activity was calculated relative to the controls, by using the following formula: , and 124 compounds with greater than 30% activity were identified for further examination (Fig. 2d). The images corresponding to these wells were manually inspected to remove obvious false positives from this tentative hit list, reducing the number of compounds to 96. Because the assay plates had been stored at 4°C, the wells in question were able to be manually inspected to determine the extent of FOXO1 nuclear translocation.

FIG. 2.

Screen performance. GFP signal (a) and Z’ (b) are stable. Fixed cells were kept at room temperature for 7 days and imaged at day 0, day 1, and day 7. (c) Distribution of Z’ across the screen. (d) The results of the entire HTS-dataset have been calculated to identify potential activators of FOXO1 nuclear translocation. ‘Activity’ is the FOXO1-GFP Nuc-Cyto difference normalized to positive and negative controls.

During manual inspection of tentative hits, 4 categories of cells were observed. First, in some cases the images were slightly out-of-focus, causing the image analysis software to give an inaccurate estimate of nuclear vs. cytoplasmic localization of FOXO1-GFP. Second, treatment with some compounds affected cell shape, causing them to round up. In contrast to the normally very flat U2OS cell shape, this rounded cell phenotype caused false positives since the cytoplasm and nucleus were not as spatially distinct in these cases. These 2 categories were considered false positives and were not further tested.

The third category contained wells with mixed populations of what appeared to be responding cells and non-responding cells. This mixture could be caused by biological or technical reasons (see below), and in most cases these compounds were allowed to pass as hits from the primary screen. The fourth category contained wells with nuclear translocation of FOXO1 to the nucleus in nearly all cells, without any evidence of poor focus or cell rounding. There were 96 compounds in the third and fourth categories; these were considered as hits worth testing further. Among these compounds were wortmannin and LY294002, 2 members of our bioactive compound library, previously known to inhibit PI3K upstream of FOXO1. Identification of wortmannin and LY294002 as hits validated the ability of this assay to identify chemical regulators of FOXO1 nuclear translocation among a library of variable compounds.

Heterogeneity of response

In most high throughput assays, detailed information about the response of individual cells is not possible, and only an average response for a population of cells is measured. High content assays, whether image-based or flow cytometry-based, allow for the investigation of cellular response of each individual cell within the population. This feature is particularly valuable when sub-populations of interest exist (such as cells in a certain stage of the cell cycle, or cells exhibiting some other biomarker of interest). Additionally, image-based high content screening gives spatial information (position) of each cell, allowing for the analysis of differential response based on location within the well.

Wells containing cells of varying response levels might be the result of an interesting biological phenomenon, or simply the result of a technical artifact. In the first case, the localization of FOXO1 to the nucleus might be varied in some cases because the tested compound is effective only in cells in a particular biological state. For example, a given compound might cause FOXO1 translocation in cells at a certain cell cycle stage, or the translocation might be dependent on the extracellular environment (the cell’s proximity to other cells and/or to the edge of the well).

Alternatively, the varied response within a well might stem from technical reasons. In this assay, compounds dissolved in DMSO were delivered by pin tool to cells in an aqueous growth medium. This delivery method might result in an increased concentration at the point of delivery (i.e., where the pin gently touches the well bottom; Fig. 3a). This elevated local concentration of compound might yield an increased response in cells near the point of delivery as compared to cells in other regions of the well.

To test the possibility that using the pin tool for compound delivery might create a concentration gradient within the well and thus a gradient of response across the cells within the well, we measured the response of each quadrant of the well. After treatment with an approximately EC50 concentration (0.5 nM) of the control compound wortmannin, four images were acquired; together, these images cover the entire well surface (Fig. 3b). Nuclear translocation was calculated for the cells in each of the 4 images, correlating to the 4 quadrants of the well (Fig. 3c).

Cells near the point of compound delivery increased nuclear FOXO1 compared to cells in distal regions of the well (Figs. 3b and 3d). Breaking the well up into the 4 fields taken during image acquisition quantitatively showed the variance across the well (Fig 3c). This effect was not observed in wells in which the wortmannin concentration was at least 10-fold higher or lower than its EC50 (data not shown). This suggests that, although there is a gradient effect within each well, it is only likely to generate a heterogeneous response if the compound is being used in amounts approximating its EC50. In the primary screen, compounds were screened at 13 μM.

Specificity testing of FOXO1 hits

Hits from the primary screen might be caused by chemical regulation of targets specific to FOXO1, such as those in the PI3K/AKT pathway, or non-specific targets, such as proteins involved in general nuclear export. To distinguish between these possibilities, the 96 compounds that increased FOXO1 nuclear localization were cherry-picked from the screening collection, diluted into 384-well compound plates (i.e., dose-response plates), and screened in triplicate for their ability to translocate another GFP-labeled FOXO family member, FOXO3-GFP, as well as the unrelated Rev-GFP. Thirty compounds showing specificity for FOXO1, FOXO3, or both, with respect to Rev, were ordered as fresh powder from the appropriate chemical supplier. These compounds were then dissolved, and checked for purity by mass spectrometry. The fresh compounds were re-tested for activity in the FOXO1, FOXO3, and Rev translocation assays (Table 2). To our surprise, one of the compounds, SJ000128583, showed virtually no activity during confirmatory screening using fresh powder compound.

Table 2.

Specificity testing of compounds affecting FOXO1-GFP’s nuclear translocation

| Compound ID | FOXO1 EC50 (μM) | FOXO1 MAX (% Activity) | FOXO3 EC50 (μM) | FOXO3 MAX (% Activity) | Rev EC50 (μM) | Rev MAX (% Activity) | Ethidium EC50 (μM) | Ethidium MAX (% Activity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SJ000131336 | 8.1 | 55 | N.D. | 15 | 9.7 | 6 | N.D. | −6 |

| SJ000129673 | 13.8 | 39 | 20.4 | 9 | 3.1 | −1 | 7.8 | 13 |

| SJ000138301 | 18.2 | 80 | 15.1 | 28 | N.D. | 7 | 11.6 | 4 |

| SJ000288312 | 18.5 | 53 | 23.8 | 28 | N.D. | 2 | 29.7 | 37 |

| SJ000134820 | 21.6 | 71 | 33.0 | 35 | N.D. | 4 | 24.3 | 7 |

| SJ000129038 | 23.3 | 96 | 20.8 | 62 | 18.8 | 18 | 7.4 | 18 |

| SJ000133952 | 26.1 | 116 | 26.4 | 14 | 55.2 | 14 | N.D. | 4 |

| SJ000128190 | 28.5 | 162 | 29.5 | 40 | N.D. | −3 | 28.0 | 2 |

| SJ000112789 | 50.3 | 72 | N.D. | 20 | N.D. | 1 | 0.5 | 7 |

| SJ000112849 | 64.5 | 125 | N.D. | 40 | N.D. | 11 | 58.6 | 4 |

| SJ000130476 | 6.0 | 109 | 8.6 | 56 | 10.5 | 25 | N.D. | 2 |

| SJ000130584 | 9.2 | 101 | 17.1 | 32 | 18.5 | 14 | 17.0 | 8 |

| SJ000139718 | 13.0 | 172 | 60.8 | 68 | 25.0 | 38 | N.D. | 13 |

| SJ000129289 | 15.7 | 355 | 17.3 | 130 | 19.0 | 123 | 12.2 | 59 |

| SJ000137622 | 17.8 | 87 | N.D. | 15 | 23.6 | 27 | N.D. | 4 |

| SJ000128040 | 18.4 | 65.8 | N.D. | 79 | N.D. | 54 | 10.4 | 10 |

| SJ000288182 | 20.8 | 220 | 65.5 | 154 | 17.6 | 50 | N.D. | −10 |

| SJ000133010 | 23.1 | 58 | 24.2 | 49 | 40.6 | 17 | 16.3 | 12 |

| SJ000139522 | 23.2 | 133 | 26.9 | 51 | N.D. | 5 | 17.7 | 17 |

| SJ000132003 | 23.3 | 54 | 41.4 | 32 | N.D. | 35 | 20.4 | 33 |

| SJ000130711 | 24.9 | 121 | 72.2 | 24 | 46.6 | 21 | 25.2 | 20 |

| SJ000138922 | 27.9 | 114 | 32.0 | 73 | 34.1 | 94 | N.D. | 30 |

| SJ000136117 | 35.6 | 115 | N.D. | 26 | 80.8 | 36 | 41.7 | 12 |

| SJ000129192 | 36.7 | 159 | 49.3 | 85 | 47.7 | 30 | N.D. | 37 |

| SJ000135706 | 42.2 | 194 | 55.3 | 124 | 124.6 | 67 | N.D. | 19 |

| SJ000136763 | 42.7 | 127 | 24.2 | 88 | 36.1 | 56 | N.D. | 13 |

| SJ000128953 | 42.7 | 175 | 53.0 | 63 | 48.6 | 24 | 49.6 | 14 |

| SJ000138767 | 65.4 | 131 | 10.3 | 5 | 92.6 | 23 | 13.2 | 8 |

| SJ000287647 | N.D. | 51 | 20.0 | 43 | 19.5 | 9 | N.D. | 10 |

| SJ000128583 | N.D. | 1 | N.D. | 2 | N.D. | −3 | 10.4 | 5 |

Note: EC50 and normalized maximum percent activity values are reported for 30 compounds tested in FOXO1, FOXO3, and Rev translocation assays and induction of oxidative cellular stress. N.D. (not determined) denotes that a suitable curve could not be fitted to the data to determine the EC50. In all cases, curves were fit to triplicate data.

When comparing these three cell lines, we faced the challenge of comparing data from different cell lines that were normalized to different control compounds (wortmannin for FOXO1 and FOXO3 and leptomycin B for Rev). We previously observed that FOXO3 showed a drastic difference between wortmannin treatment (a compound known to act upstream of FOXO proteins) and leptomycin B (a compound which enriches FOXO3 in a non-specific manner) (Fig. 1b). To overcome the challenge of comparing data from different cell lines that were normalized to different control compounds, all data were normalized to DMSO (low signal) and leptomycin B (high signal) prior to comparing the responses of the different proteins.

Because FOXO1 nuclear translocation can be triggered by the induction of oxidative stress, hits from the primary screen were also tested for their ability to induce cellular oxidative stress within the 1-hour window used in the primary screen using dihydroethidium (DHE). In oxidatively stressed cells, DHE is rapidly converted to ethidium, a common fluorescent DNA dye (Fig. 4).17 Compared to treatment with 0.5% hydrogen peroxide, the tested compounds showed very little indication of inducing cellular oxidative stress after compound treatment. Of the 30 compounds tested, 24 compounds had less than a 20% response as measured by ethidium staining (Table 2), suggesting that, although low levels of oxidative stress were induced in some cells, this stress was not a driving factor for FOXO1 nuclear translocation. Table 2 lists the EC50 and maximal activity (% activity) levels of these compounds for FOXO1, FOXO3, and Rev nuclear translocation as well as the results of DHE nuclear staining.

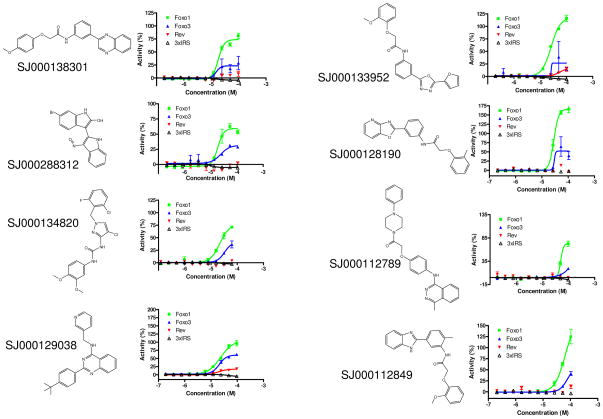

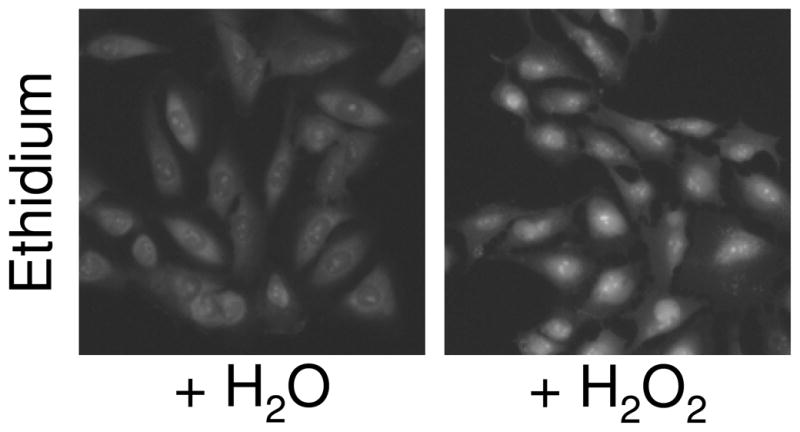

FIG. 4.

Cellular oxidative stress. Conversion of dihydroethidium (DHE) to ethidium was used to measure cellular oxidative stress. U2OS/FOXO1-GFP cells were treated with 0.1% H2O2 or an equivalent volume of water (negative control) 30 min prior to staining, fixation, and image acquisition.

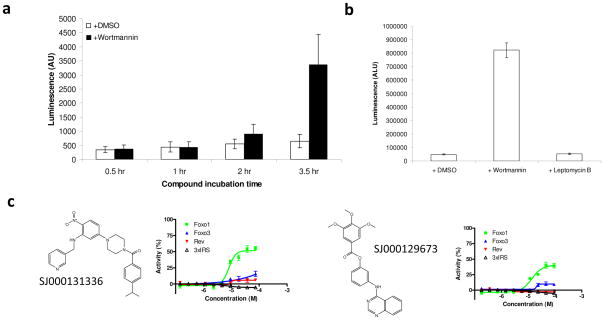

Functional testing of FOXO1 hits

Members of the FOXO family of transcription factors are critical in regulating genes in a number of essential pathways, including cell cycle progression, metabolism, apoptosis, and stress resistance. To determine whether translocation of FOXO1 to the nucleus after compound treatment resulted in increased transactivation activity, we used the 3×IRS-luc reporter in a luciferase assay. Since FOXO1 activation can also trigger apoptosis, which would result in decreased reporter activity due to dying cells, we identified the earliest timepoint when FOXO1 activity could be reliably detected (Fig. 5a). We found that treating the cells for at least 3.5 hours was sufficient to produce a significant response (p < 0.001).

FIG. 5.

Transcriptional activation of a FOXO1-responsive promoter reporter gene (3×IRS-luc). (a) Determination of the earliest timepoint for wortmannin (100 nM) to activate3×IRS-luc. (b) Wortmannin (100 nM), but not Leptomycin B (10 μM), activates 3×IRS-luc after only 4 h of incubation. (c) Representative compounds that specifically induced FOXO1 and/or FOXO3 nuclear translocation failed to activate 3×IRS-luc. The name and structure of each compound are shown on the left of each set of curves. AU, arbitrary unit. DMSO (low signal) and 10 μM of leptomycin B (high signal) were used to calculate the normalized activity (% Activity) of FOXO1-GFP, FOXO3-GFP, and Rev-GFP nuclear translocation. DMSO (low signal) and 100 nM of wortmannin (high signal) were used to calculate the normalized activity (% Activity) of 3×IRS-luc activity. The values represent the average of 3 independent experiments; error bars denote the standard deviation. AU, arbitrary unit.

We next tested 10 representative compounds (the first 10 compounds in Table 2) that exhibited specificity for FOXO1 or FOXO1 and FOXO3 nuclear translocation for transactivation activity. After 4 hours of incubation with wortmannin, there was a strong response, demonstrating that the assay was functioning (Fig. 5b). None of the 10 representative compounds tested were able to activate FOXO1 transactivation activity even when nuclear FOXO1 levels were elevated (Fig. 5c). In fact, a slight decrease in signal was observed when many of the compounds were used at higher concentrations, suggesting that cell death may have been decreasing luciferase signal even at the 4-hour timepoint. Additionally, prior to the addition of the reporter assay reagent (see Material and Methods), nuclear translocation of FOXO1 was verified by fluorescence microscopy (data not shown). These results suggest that nuclear translocation is only one mechanism by which FOXO1 activity is regulated. This result is consistent with previous work showing the poor correlation between FOXO1 localization and transactivation activity.18

DISCUSSION

FOXO1 is an attractive and challenging target for small-molecule screens because of its many roles in regulating cell signaling. This study describes the development of an image-based high-content screen to identify small molecules that enrich FOXO1 in the nucleus. Using wortmannin and leptomycin B as controls, we optimized cell plating and compound treatment conditions, fixation, DNA staining, image acquisition, and image analysis to develop a robust assay suitable for high-throughput screening. During the screening of the bioactive compound library, we identified 2 previously characterized compounds acting upstream of FOXO1 (wortmannin and LY294002), validating the ability of this assay to identify active compounds.

During screening, the primary confounding factors were focal problems during image acquisition (leading to inaccurate image analysis), compounds that affected cell shape, and compounds that gave a heterogeneous response among the cells in a single well. Achieving accurate focus is a challenge for all automated, image-based assays. The CellWoRx system uses image-based autofocus, which is slow but offers the advantage of actually focusing on the objects-of-interest independent from other variables (e.g., plate thickness). Fluorescent debris on the plate or within the well occasionally misguides the system to focus on objects other than cells; however, careful handling of the plates decreases the chance of contamination by debris and reduces this effect. Compounds that affect the cytoskeleton and cell shape also lead to false positives in this assay. Although we did not address this problem directly, staining either the entire cell (i.e., using a whole-cell stain) or only the membrane should provide a simple way to measure average cell size, diameter, and other parameters to determine gross changes in cell shape that might lead to false positives. Multiplexing cell morphology measurements with Nuc- Cyto difference of the protein-of-interest would allow compounds affecting cell shape to be removed from the hit list, lowering the false-positive rate.

The last confounding effect was the heterogeneity of response observed within a single well. This variance in response might be rooted in the subtle differences between neighboring cells within a single well. Through multi-parametric analysis of several biomarkers, one might eventually gain clues into the biological underpinnings of this phenomenon. Another possible cause of variance within a well is the uneven distribution of compound within the well as delivered by pin transfer from a DMSO stock. We tested this hypothesis directly and observed a clear gradient of response for the positive control compound, wortmannin. This suggests that assays measuring a relatively rapid response to compound treatment (i.e. short incubation time with tested compounds) might be particularly susceptible to such a chemical gradient found immediately after compound addition. Other cell-based assays tested, with 1–3 day compound treatment did not show a detectable gradient of response (data not shown).

The phenomenon of unequal compound distribution is particularly relevant to high-content screens in which typically only a small sub-area of the well is sampled (i.e., imaged) as the assay endpoint. The distance between the point of compound delivery and the area of image acquisition could lead to false negatives or false positives in a primary screen, as well as slightly shifted dose-response curves during follow-up testing. During the primary and secondary assays, we acquired a single image in the center of the well. Because the pin delivered compound to the left of and a little below center (see Fig. 3b, asterisk), the image we acquired was neither right on top of, nor extremely far away from the point of compound delivery. In the center of the well where we acquired the image, the gradient is at its least extreme (see Fig. 3d) and the effect of compound gradient on our results is therefore minimal. The compound gradient caused by pintool might have an effect on the results, but this potential effect can be minimized technically by appropriately selecting the location for image acquisition. It is expected that compound delivery by pipetting or acoustic nanodrop dispensing could drastically reduce the impact of this effect.

This screen successfully identified compounds affecting FOXO1’s nuclear translocation. Interestingly, no functional activity (i.e., transcriptional activation of FOXO1-responsive promoter) was observed for these compounds. Of the previous studies examining chemical regulators of FOXO1 or FOXO3 translocation, only one has compared localization of these proteins to their transcriptional activation.18 Unterreiner et al. showed a poor correlation between hits from image-based screening of FOXO3 activators and those from reporter-based screening.18 Kau et al. identified inhibitors of FOXO1 nuclear export, but whether these inhibitors affect the transcriptional activity of FOXO1 was not reported.19 Our data are consistent with the interpretation that nuclear translocation is only one mechanism of FOXO1 regulation. In fact, even when localized to the nucleus, FOXO1 is not necessarily active, suggesting that it is subject to multiple layers of regulation and that spatial regulation (i.e., shuttling into/out of the nucleus) is only one of these.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kun-Liang Guan for providing 3×IRS-luc; Dr. Kip Guy for reviewing the manuscript and valuable discussions; Dr. Cherise Guess for editing the manuscript; Cindy Nelson for assistance with compound management; Dr. Andrew Lemoff for analytical chemistry support; and other members of the Chen group for reagents and their valuable discussions. This work was supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and National Cancer Institute grant P30CA027165.

References

- 1.Reagan-Shaw S, Ahmad N. The role of Forkhead-box Class O (FoxO) transcription factors in cancer: a target for the management of cancer. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2007;224:360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis RJ, D’Cruz CM, Lovell MA, Biegel JA, Barr FG. Fusion of PAX7 to FKHR by the variant t(1;13)(p36;q14) translocation in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Research. 1994;54:2869–2872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galili N, Davis RJ, Fredericks WJ, Mukhopadhyay S, Rauscher FJ, 3rd, Emanuel BS, Rovera G, Barr FG. Fusion of a fork head domain gene to PAX3 in the solid tumour alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Nature Genetics. 1993;5:230–235. doi: 10.1038/ng1193-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hillion J, Le Coniat M, Jonveaux P, Berger R, Bernard OA. AF6q21, a novel partner of the MLL gene in t(6;11)(q21;q23), defines a forkhead transcriptional factor subfamily. Blood. 1997;90:3714–3719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kops GJ, Medema RH, Glassford J, Essers MA, Dijkers PF, Coffer PJ, Lam EW, Burgering BM. Control of cell cycle exit and entry by protein kinase B-regulated forkhead transcription factors. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2002;22:2025–2036. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2025-2036.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medema RH, Kops GJ, Bos JL, Burgering BM. AFX-like Forkhead transcription factors mediate cell-cycle regulation by Ras and PKB through p27kip1. Nature. 2000;404:782–787. doi: 10.1038/35008115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramaswamy S, Nakamura N, Sansal I, Bergeron L, Sellers WR. A novel mechanism of gene regulation and tumor suppression by the transcription factor FKHR. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt M, Fernandez de Mattos S, van der Horst A, Klompmaker R, Kops GJ, Lam EW, Burgering BM, Medema RH. Cell cycle inhibition by FoxO forkhead transcription factors involves downregulation of cyclin D. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2002;22:7842–7852. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7842-7852.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dijkers PF, Medema RH, Lammers JW, Koenderman L, Coffer PJ. Expression of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bim is regulated by the forkhead transcription factor FKHR-L1. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1201–1204. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00728-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang TT, Dowbenko D, Jackson A, Toney L, Lewin DA, Dent AL, Lasky LA. The forkhead transcription factor AFX activates apoptosis by induction of the BCL-6 transcriptional repressor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14255–14265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao X, Gan L, Pan H, Kan D, Majeski M, Adam SA, Unterman TG. Multiple elements regulate nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling of FOXO1: characterization of phosphorylation- and 14-3-3-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Biochem J. 2004;378:839–849. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Horst A, Burgering BM. Stressing the role of FoxO proteins in lifespan and disease. Nature Reviews. 2007;8:440–450. doi: 10.1038/nrm2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehtinen MK, Yuan Z, Boag PR, Yang Y, Villen J, Becker EB, DiBacco S, de la Iglesia N, Gygi S, Blackwell TK, Bonni A. A conserved MST-FOXO signaling pathway mediates oxidative-stress responses and extends life span. Cell. 2006;125:987–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamagata K, Daitoku H, Takahashi Y, Namiki K, Hisatake K, Kako K, Mukai H, Kasuya Y, Fukamizu A. Arginine methylation of FOXO transcription factors inhibits their phosphorylation by Akt. Molecular Cell. 2008;32:221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed D, Shen Y, Shelat AA, Arnold LA, Ferreira AM, Zhu F, Mills N, Smithson DC, Regni CA, Bashford D, Cicero SA, Schulman BA, Jochemsen AG, Guy RK, Dyer MA. Identification and characterization of the first small molecule inhibitor of MDMX. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10786–10796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.056747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang ED, Nunez G, Barr FG, Guan KL. Negative regulation of the forkhead transcription factor FKHR by Akt. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16741–16746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bindokas VP, Jordan J, Lee CC, Miller RJ. Superoxide production in rat hippocampal neurons: selective imaging with hydroethidine. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1324–1336. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01324.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unterreiner V, Ibig-Rehm Y, Simonen M, Gubler H, Gabriel D. Comparison of variability and sensitivity between nuclear translocation and luciferase reporter gene assays. J Biomol Screen. 2009;14:59–65. doi: 10.1177/1087057108328016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kau TR, Schroeder F, Ramaswamy S, Wojciechowski CL, Zhao JJ, Roberts TM, Clardy J, Sellers WR, Silver PA. A chemical genetic screen identifies inhibitors of regulated nuclear export of a Forkhead transcription factor in PTEN-deficient tumor cells. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:463–476. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]