From Greek mythology and the Bible to modern critiques of the digital age, loneliness has been portrayed as part of the human condition. Recognition of the significant adverse consequences for health has come more recently, with much of the interest triggered by a rise in the death rate in Europe in 2003. Unusually high temperatures in the summer of that year were linked with the deaths of more than 40,000 mainly elderly people throughout mainland Europe. Proportionately fewer deaths were recorded among frail and sick older people living in institutions, compared with more able, but less well-supported people living in the community. These deaths stimulated much discussion and reflection on the treatment of elders in society. In France, and later the UK, non-governmental organizations instigated campaigns to address loneliness and isolation among the aged. Such campaigns, along with research from different disciplines linking loneliness and isolation with adverse health outcomes and premature mortality, have focused attention on the problems. But despite acknowledgement of isolation in the UK National Service Framework for Older People in relation to falls and depression,1 concern among care providers and commissioners has never matched the breadth and severity of the consequences of isolation and loneliness. In this article, we present an overview of current evidence and suggest that a renewed research agenda is required for a growing older population.

Age and inequalities

Loneliness and isolation are increasingly part of the experience of growing old. Reduced inter-generational living, greater social and geographical mobility, the rise in one-person households – all of these trends mean that older adults may become more socially isolated. For elders with the resources to choose to live in a retirement community, travel to visit friends or simply to get online, the adverse consequences of loneliness may be minor. For others made vulnerable by sickness or poverty – perhaps after a lifetime of poor access to healthcare in countries without comprehensive welfare provision – the impact of loneliness and isolation may be profound. The experience and consequences of loneliness and isolation vary with social position. Tackling these issues, therefore, has the potential to play a role in reducing health inequalities, as well as improving individuals’ quality of life.

Concepts and measurement

Loneliness and social isolation are distinct concepts: individuals can be lonely without being socially isolated; experience both loneliness and isolation; or be socially isolated without feeling lonely. One of the most widely used definitions has loneliness as a subjective negative feeling associated with a perceived lack of a wider social network (social loneliness) or the absence of a specific desired companion (emotional loneliness). There is much less of a consensus about how to define social isolation. Many studies have approached it as a unidimensional concept, defining social isolation as the objective lack or paucity of social contacts and interactions with family members, friends or the wider community. Alternative, multidimensional, definitions have incorporated the quality, as well as the quantity, of relationships – with loneliness falling under the subjective component of social isolation.2

How people define loneliness and social isolation is important because it influences how they measure these concepts. There are a number of widely used self-report measures for loneliness, such as the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale or the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale. The UCLA measure contains items to measure self-perceived isolation, and relational and social connectedness. The De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale combines social and emotional subscales, and encompasses such issues as a sense of emptiness and missing having people around, with the presence of people to rely on, trust and feel close to. A broader range of approaches have been applied to the measurement of isolation, from judging the levels of social contact and the size of social networks to recording marital status or household composition.

Quantifying the extent of loneliness and social isolation is essential, but it has been a challenge to researchers. Variation in the current estimates partly stem from the absence of universally accepted definitions and the difference in the phenomena observed, as well as from the range of indicators and measurement tools used. Experiences of loneliness and social isolation are not uniform across the life course: individuals may become lonely or isolated in old age, be lifelong isolates, or experience loneliness or isolation as a result of a triggering event such as retirement or bereavement. Loneliness can be a persistent or short-lived feeling, and one which individuals may be reluctant to share.

Prevalence and aetiology

Community studies have reported rates of severe loneliness among adults aged 65 and over of between 2% and 16%,3 while at any one given time up to 32% of individuals aged over 55 feel lonely.4 The prevalence of loneliness among institutionalized older adults is less well documented, but it is believed to be a common experience in long-term care. One study found that more than half of nursing home residents without cognitive impairment reported feeling lonely.5 Like loneliness, social isolation among older adults is substantial, with rising trends among populations across the world. In 2004, a non-institutionalized American was much more likely to report that they were completely isolated from people with whom he or she could discuss important matters, compared with two decades earlier.6

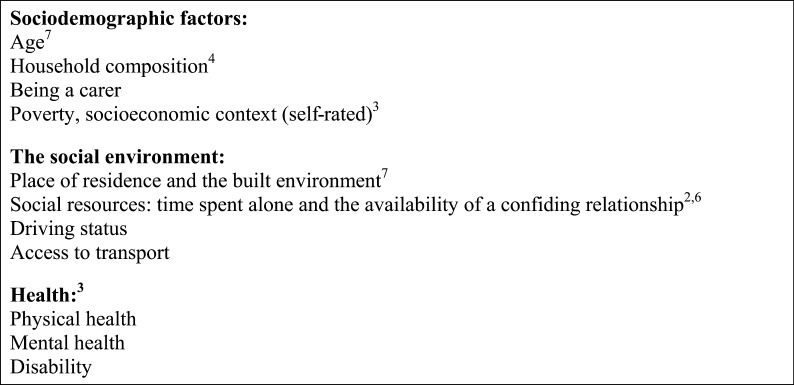

Factors that have been linked to social isolation and loneliness in later life range from sociodemographic characteristics to material resources and health status (Figure 1).7 The majority of available evidence has been collected through cross-sectional studies, which provide no information on the direction of the association between loneliness or isolation and health or other factors. This is one of the major limitations of research in this area. Ill health and immobility that leave people less able to socialize may lead to isolation and loneliness. Alternatively, loneliness may be a causal factor for ill health. Without more longitudinal studies, this and the independent effect of different, interacting variables may be impossible to disentangle. The identification of older age as a risk factor may thus be attributable to interactions with other factors such as the loss of contemporaries, cognitive impairment and disability.

Figure 1.

Risk factors for social isolation and loneliness among older adults

Mortality and morbidity

Lonely or isolated older adults are at greater risk for all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis encompassing 148 longitudinal studies, with 308,849 participants followed for an average of 7.5 years, has reported that individuals with strong social ties have a 50% greater likelihood of survival compared with those who have poor social relationships and networks.8 This effect is greater than that of other well-established risk factors for mortality such as physical inactivity and obesity, and comparable with cigarette smoking. Older adults who experience loneliness or social isolation are likewise at greater risk for increased morbidity. Both have been associated with increased risks of some of the major causes of disease burden, worldwide. Social isolation and loneliness have been implicated in the development and progression of cardiovascular disease.9,10 A study of 1203 healthy people living at home in Stockholm found that an extensive social network appears to protect against dementia,11 while lonely individuals within a cohort of over 800 older adults in Chicago were more than twice as likely to develop Alzheimer's disease than those who were not lonely, over four years of follow-up.12

Compared with our understanding of risk factors such as smoking and obesity, we know much less about the mechanisms through which loneliness and social isolation affect health. The association between loneliness and blood pressure has implicated physiological functioning as a causal factor, but there is emerging evidence for the role of neuro-endocrine effects, hormonal influences on gene transcription and cellular immunity.9 Other research suggests that the association with health behaviours may be important. Social relationships have been shown to promote healthy behaviours, and socially isolated individuals’ health may deteriorate because they lack the social and environmental support that are critical to maintaining independence in later life. In contrast, a change in health behaviour does not appear to account for the association between loneliness and worse health outcomes.13

Effects on service utilization

Research shows that socially isolated and lonely adults are more likely to undergo early admission into residential or nursing care.14 Loneliness has been identified as a significant factor in physician utilization, independent of health status, depression and somatic complaints, though evidence for a higher consultation rate in British family practice is conflicting.15,16 Greater loneliness has been independently associated with emergency hospitalization – but not planned inpatient admissions – among community-dwelling older adults.17 Researchers in Los Angeles found that social isolation among older people was linked with a four- to five-fold increase in the likelihood of re-hospitalization within the year.18

Interventions

A variety of interventions have been directed towards alleviating loneliness and social isolation, ranging from social and physical activities such as choir rehearsals, lunch clubs, school visits and sport groups to counselling and therapy. The heterogeneity of interventions, multiplicity of measurement tools and outcome measures, alongside poor methodological quality and a focus on subgroups of the population, have all limited researchers’ ability to draw definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of interventions. Initiatives are often introduced by community groups or charities in local neighbourhoods, and seldom evaluated. Where evaluations have been carried out, success has tended to be judged by measures of process such as the number of people reached and the extent of participants’ satisfaction. The degree to which interventions have affected participants’ loneliness or social isolation often remains unknown; and the contextual circumstances are often not taken into account. Characteristics that are more likely to be associated with effective interventions are the presence of an underpinning theoretical framework, active rather than passive participation, and group rather than one-to-one delivery.19,20

Implications for clinicians and health services

The influence of loneliness and isolation on mortality is significant. The link with health is less clearly understood, but there are substantial data on pathophysiological mechanisms and growing evidence of an association with established disease. On their own, these are sufficient reasons to interest clinicians, but what if loneliness and isolation also play a role in the success or failure of some medical therapies? Effects on physiological functioning could reduce the effectiveness of treatments, and if loneliness or isolation influence health behaviour, it is plausible that adherence to advice or medication may be affected.

In elderly care and family practice, if lonely and isolated patients are being treated more often than others, then health practitioners are well placed to play a key role in identifying those at highest risk. We do not yet know how the individual clinician can best intervene once they have identified isolated or lonely patients in the clinic; but what is clear is that addressing this problem more directly could have benefits for the health system and for the affected individuals. As well as experiencing greater levels of morbidity, lonely and isolated individuals appear to use more healthcare resources and are more likely to need long-term care. Older adults are the greatest consumers of healthcare, so a four-fold increase in hospital readmission rates among lonely older adults, for example, is noteworthy. The interventions that have been implemented to address loneliness and isolation – social activities or psychological therapies – are low cost when compared with many medical technologies. A drive to address loneliness and isolation could prove to be one of the most cost-effective strategies that a health system could adopt, and a counter to rising costs of caring for an ageing population.

A renewed research agenda

Current research evidence on loneliness, social isolation and health in older adults draws upon work from a range of different disciplines. Demographers, sociologists, psychologists, neuroscientists, gerontologists and others have all framed the challenges and solutions from their own perspectives. This has contributed to the richness of our knowledge, but the absence of a clear message from a single body of work may also have allowed policy-makers to ignore the potential health gain from addressing loneliness and isolation, with attention and resources directed to more tangible, clearly defined problems.

For loneliness and social isolation in older adults to be taken seriously by practitioners and policy-makers, we need to renew the research agenda, focusing more closely on the risks to public health. Demographic shifts and a high prevalence among some older groups should place prevention at the heart of any strategies to tackle loneliness and isolation. Primary prevention of loneliness is likely to require action earlier in the life-course, with work to conserve social networks or develop resilience, for example. Longitudinal studies will enable us to better understand how loneliness, social isolation and health interact over time, and to distinguish between cause and effect. Research must also consider the different ways in which interventions might reach lonely and isolated older adults. Population-based strategies are essential, as we know that targeting high-risk individuals may widen social inequalities, but if consultation rates are high among this hard-to-reach group of lonely older people, the opportunities afforded by contacts with health services should be fully explored. In relation to loneliness and isolation, secondary prevention activities might identify people who are lonely but healthy, while tertiary prevention acts to minimize progression of the adverse health effects of loneliness. Both require systematic assessment of needs, and a cross disciplinary approach that acknowledges the complexity of interventions and overcomes barriers between health and social, public health and medical.

The evidence base for the implications of loneliness and social isolation in older adults is growing, but at present the extent of the public health challenge posed by loneliness and social isolation, and the potential health gain from intervention, are uncertain. At times of financial stringency, with an ageing population, the possibility of a low-cost option to improve health should not be overlooked. A renewed research agenda with public health principles at its core, embracing the role of health and social interventions, would be best placed to answer some of the biggest questions facing those who are concerned for lonely, isolated older people.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

BH is supported by an NIHR Career Development Fellowship (NIHR CDF-2009-02-37). NV is funded from the same grant. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health

Ethical approval

Not required

Guarantor

BH

Contributorship

BH and NV developed the idea for the article, NV wrote the first draft. Both authors have seen and approved the final version

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Campaign to End Loneliness whose research hub provides a valuable forum for researchers

References

- 1.Department of Health, National Service Framework for Older People. London: Stationery Office, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Victor C, Scambler S, Bond J The social world of older people. Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wenger GC, Davies R, Shahtahmasebi S, Scott A Social isolation and loneliness in old age: Review and model refinement. Ageing Soc 1996;16:333–58 [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Jong Gierveld J, van Tilburg T Living arrangements of older adults in the Netherlands and Italy: coresidence values and behaviour and their consequences for loneliness. J Cross Cultur Gerontol 1999;14:1–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drageset J, Kirkevold M, Espehaug B Loneliness and social support among nursing home residents without cognitive impairment: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nur Stud 2011;48:611–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Brashears ME Social isolation in America: changes in core discussion networks over two decades. Am Sociol Rev 2006;71:353–75 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gierveld JdJ A review of loneliness: concept and definitions, determinants and consequences. Rev Clin Gerontol 1998;8:73–80 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med 2010;40:218–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knox SS, Uvnas-Moberg K Social isolation and cardiovascular disease: an atherosclerotic pathway? Psychoneuroendocrinology 1998;23:877–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fratiglioni L, Wang HX, Ericsson K, Maytan M, Winblad B Influence of social network on occurrence of dementia: a community-based longitudinal study. Lancet 2000;355:1315–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE, et al. Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:234–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawkley LC, Burleson MH, Berntson GG, Cacioppo JT Loneliness in everyday life: cardiovascular activity, psychosocial context, and health behaviors. J Pers Soc Psychol 2003;85:105–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savikko N, Routasalo P, Tilvis R, Pitkala K Psychosocial group rehabilitation for lonely older people: favourable processes and mediating factors of the intervention leading to alleviated loneliness. Int J Older People Nurs 2010;5:16–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellaway A, Wood S, Macintyre S Someone to talk to? The role of loneliness as a factor in the frequency of GP consultations. Brit J Gen Pract 1999;49:363–7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iliffe S, Kharicha K, Harari D, Swift C, Gillmann G, Stuck AE Health risk appraisal in older people 2: the implications for clinicians and commissioners of social isolation risk in older people. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:277–82 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molloy GJ, McGee HM, O'Neill D, Conroy RM Loneliness and emergency and planned hospitalizations in a community sample of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1538–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mistry R, Rosansky J, McGuire J, McDermott C, Jarvik L, Group UC Social isolation predicts re-hospitalization in a group of older American veterans enrolled in the UPBEAT Program. Unified psychogeriatric biopsychosocial evaluation and treatment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:950–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickens AP, Richards SH, Greaves CJ, Campbell JL Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: a systematic review. Bmc Public Health 2011;11:647 (15 August 2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cattan M, White M, Bond J, Learmouth A Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: a systematic review of health promotion interventions. Ageing Soc 2005;25:41–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]