Abstract

The association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking has been described in more than 1,000 articles, many with inadequate methodology. The studies on this association can focus on: (1) current smoking, ever smoking or smoking cessation; (2) non-psychiatric controls or controls with severe mental illness (e.g., bipolar disorder); and (3) higher smoking frequency or greater usage in smokers. The association with the most potential for genetic studies is that between ever daily smoking and schizophrenia; it may reflect a shared genetic vulnerability. To reduce the number of false-positive genes, we propose a three-stage approach derived from epidemiological knowledge. In the first stage, only genetic variations associated with ever daily smoking that are simultaneously significant within the non-psychiatric controls, the bipolar disorder controls and the schizophrenia cases will be selected. Only those genetic variations that are simultaneously significant in the three hypothesis tests will be tested in the second stage, where the prevalence of the genes must be significantly higher in schizophrenia than in bipolar disorder, and significantly higher in bipolar disorder than in controls. The genes simultaneously significant in the second stage will be included in a third stage where the gene variations must be significantly more frequent in schizophrenia patients who did not start smoking daily until their 20s (late start) versus those who had an early start. Any genetic approach to psychiatric disorders may fail if attention is not given to comorbidity and epidemiological studies that suggest which comorbidities are likely to be explained by genetics and which are not. Our approach, which examines the results of epidemiological studies on comorbidities and then looks for genes that simultaneously satisfy epidemiologically suggested sets of hypotheses, may also apply to the study of other major illnesses.

Introduction

This article proposes a study approach to investigate the genetics of the association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking based on results from the epidemiological literature. After an introduction, a short section that summarizes the various types of published data follows. The next two sections describe the association of schizophrenia with higher frequency and with higher intensity of smoking. The section describing the proposed study approach is followed by two sections placing the association between schizophrenia and smoking in the context of other psychiatric comorbidities: the association between nicotine and alcohol addiction, and the association between nicotine and drug addiction. Then, a description of how our study approach may take advantage of these other comorbidities follows.

This introduction provides the genetic expert without expertise in psychiatry with information on (1) the size and quality of the literature on schizophrenia and smoking; (2) some epidemiological statistical concepts; (3) the concept of addiction; (4) the concept of nicotine addiction; (5) the genetics of nicotine addiction; (6) the association between schizophrenia and nicotine addiction; and (7) the concept of severe mental illness (SMI), which encompasses other illnesses besides schizophrenia that are also associated with nicotine addiction, particularly bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.

Schizophrenia and tobacco smoking literature

The literature is full of articles on the association between smoking and schizophrenia. A PubMed search on “schizophrenia AND (smoking OR nicotine)” on July 6, 2011, produced 1,341 articles. If one is not an expert in this area, one would think that more than 1,000 published articles would provide a good understanding of this association. We propose in this article that, unfortunately, this is not the case. Many of the published articles include simplistic statements due to misinterpretation of statistical associations as causal relationships. Clinicians and basic scientists may not be aware of the limitations of the epidemiological approach and may not realize that many of the statements published in articles on the association between schizophrenia and smoking are wrong, according to basic epidemiological principles. As a matter of fact, it is possible that many of the articles on schizophrenia and smoking published in the 1990s in psychiatric journals would not currently be accepted for publication by epidemiological journals as they were originally published. Many of these published articles failed to account for cross-sectional studies’ inability to establish causation and did not correct the reported statistical associations for confounding effects using multivariate statistics. Another problem with the information provided in the review sections of published articles on schizophrenia and smoking is that some authors frequently tend to ignore studies that do not fit their hypotheses and do not give proper weight to consistently replicated findings when describing the literature. As described by Ioannidis (2005), the medical literature is full of false findings due to the publication of significant but small effects observed in small samples. The most important factor in establishing a scientific finding in medicine is the finding's replication across many independent samples. In particular, it is necessary that the finding survives the variations typically associated with the “noise” present in clinical research. In this regard we are quite confident that the association of schizophrenia with tobacco smoking is a “true” finding since it is a finding that has been consistently replicated all over the world (de Leon and Diaz 2005). However, we are not sure that many of the other findings published in the context of schizophrenia and smoking research are trustworthy, since very few have been consistently replicated. Thus, simplistic statements such as “smoking improves negative symptoms or antipsychotic side effects in schizophrenia patients” are not supported by a comprehensive review of the limited literature available (de Leon et al. 2006).

Epidemiological and statistical concepts

In this article two statistical measures are used to explore associations: adjusted odds ratios (ORs), and population attributable risks (PAR) calculated with these ORs (Bolton and Robinson 2010; Greenland and Drescher 1993). The OR is a measure of the strength of the association between two dichotomous variables: the more different from 1 an OR is, the stronger the association. When the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of two ORs do not overlap, they are usually considered to be significantly different. Multivariate logistic regression allows adjusting ORs for potentially confounding variables. Once we have an adjusted OR, if we assume that the OR measures a causal relationship between a condition and a risk factor which is not explained by confounders, the PAR estimates the percentage reduction in the condition's prevalence that would be observed if the risk factor were removed from the population.

Addiction

This article uses the term “addiction” to express the compulsive nature of taking an addictive drug (Volkow and Fowler 2000). Drug addiction is a group of chronically relapsing disorders characterized by compulsion to take the drug, loss of control in limiting the intake, and emergence of negative emotional states when there is no access to the drug (Koob and Volkow 2010). The current official psychiatric diagnostic system in the US is called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and is a variation of the third edition published in 1980, called DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association 1980). The current edition of the DSM continues to use the terminology “substance use disorder”, distinguishing between abuse (pathological use) and dependence (more severe pathological use with withdrawal symptoms).

The third and subsequent DSM editions use the word “substances” to mean “nicotine”, “alcohol”, and other substances of abuse that are usually included under the name “drugs”. The term “drug” usually refers to “illegal drugs” or prescribed drugs used inappropriately. Thus, this article, unless it is specifically needed (e.g., “nicotine dependence”, which is specifically defined) uses the terms “alcohol addiction”, “nicotine addiction” and “drug addiction” (referring to drugs other than nicotine or alcohol). When we use the plural word “addictions”, we mean addiction to any of these substances (nicotine, alcohol or other drugs) in general.

For researchers interested in genetics, it is important to know that addiction heritability estimates are 40–60% (Volkow and Li 2005) or 50–60% (Bierut 2011). Bierut (2011) recently described genetic vulnerability to addiction as probably reflecting the combination of hundreds or thousands of genes of modest effects. A complex issue not completely resolved by the literature is that genetic factors influencing the use of drugs may be different from those influencing addiction. Twin studies suggest that initiation and early patterns of drug use are strongly influenced by social and familial environmental factors whereas later patterns of use and levels of addiction are strongly influenced by genetic factors (Kendler et al. 2008). Even if we accept the hypothesis that genetic factors may be much more influential in drug addictions than in drug use, an explanation of the important role of genetic influences on addictions continues to be complex. A biological hypothesis proposes that genetic factors are expressed once exposed to sufficient quantities of the drug over a sufficiently long period. The socially mediated hypothesis is based on the finding that our genes play an increasing role in shaping our own social environment; it proposes that genes may influence the selection of environments that either actively discourage or encourage drug use (Kendler et al. 2008).

As this article focuses on the role of genetics in the association between schizophrenia and nicotine addiction, a context for the genetic studies on the association between psychiatric disorders and addictions is in order. In a very comprehensive approach, Kendler et al. (2003, 2007) proposed a model that posits (1) the pattern of lifetime comorbidity of common psychiatric disorders and addictions results largely from the effects of genetic risk factors, and (2) each addiction may have disorder-specific genetic risks.

Nicotine addiction

Epidemiological studies in the 1980s and 1990s in the US and other Western countries established that the majority of smokers in these general populations smoke at last one cigarette per day; that is, they are daily smokers. Few people in the general population of Western countries are considered occasional smokers. Nicotine is the most important addictive component of tobacco smoke. Thus, daily smoking is usually considered a sign of nicotine addiction. In the general population, initiation of daily smoking rarely occurs in the decade of one's 20s (Nelson and Wittchen 1998; de Leon et al. 2002a; Dierker et al. 2008). Occasional smokers do not smoke daily, appear not to have major problems (no major withdrawal signs) when they do not smoke and, therefore, are not addicted (Shiffman 1989). “Daily smoking” is a simple and reasonable measure of nicotine addiction in epidemiological studies in Western countries.

In underdeveloped countries, few individuals can afford daily smoking and non-daily smokers need to be included in smoking studies; socioeconomic status needs to be carefully considered as well (Campo-Arias et al. 2006). In the US population, progressively greater smoking restrictions have been implemented since 2000. This has led to an increase in the proportion of non-daily smokers, who now account for one-third of the US smokers in the general population (Shiffman 2009). Therefore, Shiffman (2009) has proposed that heavy daily smoking may only occur when smoking is not constrained by economic, social, or legal restrictions.

The DSM, which has become widely used internationally since its third edition (DSM-III), does not list “nicotine abuse” as a possible diagnosis; only “nicotine dependence” is listed. Thus, the abuse and dependence concepts of this classificatory system have never particularly “worked well” for nicotine addiction. The reasons may be that (1) when compared with other drugs, nicotine is a particularly addictive substance (Henningfeld et al. 1991; Lopez-Quintero et al. 2011); and (2) it is a legal substance whose uncontrolled use is very rarely associated with legal complications. In a large US epidemiological study, Lopez-Quintero and coworkers (2011) estimated that 68% of nicotine users become dependent (vs. 23% for alcohol, 21% for cocaine, and 9% for cannabis users). The DSM concepts of nicotine dependence, however, have been used in a few epidemiological studies of the general population but not in patients with schizophrenia.

Clinicians and researchers working in smoking cessation frequently use a scale to define nicotine dependence. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) is the most widely used measure of nicotine dependence, which has been found to be a reasonable predictor of success in stopping smoking (Heatherton et al. 1991). This scale has six items. However, two of the six items, which are each scored between 0 and 3, may reflect nicotine dependence best: Item 1 (the time between waking and smoking the first cigarette of the day), and Item 4 (the number of cigarettes smoked per day). The sum of the scores of these two items is called the Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) (Heatherton et al. 1998). A high FTND or HSI score appears to be a good indication of high nicotine dependence (de Leon et al. 2003; Diaz et al. 2005). Institutional smoking restrictions may artificially lower these scores (Steinberg et al. 2005).

Nicotine addiction and genetics

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have provided some robust findings for heavy smoking genetics in the 15q25 chromosome region, which encodes some nicotine receptor subunits (Bierut 2011). According to twin studies, heritability for smoking initiation has been estimated to be in males: 37% (Li et al. 2004), 31–61% (Tyndale 2003), and 22–75% (Rose et al. 2008) and in females: 55% (Li et al. 2004), 32–72% (Tyndale 2003), and 32–63% (Rose et al. 2008). Heritability for smoking persistence has been estimated to be in males: 59% (Li et al. 2004), and 50–71% (Tyndale 2003), and in females: 46% (Li et al. 2004), and 4–49% (Tyndale 2003).

Schizophrenia and nicotine addiction

Another unfounded statement, repeated by many articles, is that 80–90% of schizophrenia patients smoke (Chapman et al. 2009). A few studies conducted in the 1980s or 1990s from Western countries, provided these very high prevalences. However, these studies are not representative of schizophrenia patients throughout the world and reflect a point in time when smoking was even used as reinforcement in psychiatric hospitals. Moreover, although we are convinced that the association of schizophrenia and smoking is very consistent across the world and that a biological explanation is likely to account for it, we have to acknowledge that, as with any other addictive drug, nicotine addiction in schizophrenia is obviously influenced by the availability of the drug. Therefore, the prevalence of tobacco smoking in a particular sample of schizophrenia patients is going to be influenced by the availability of tobacco in the particular place and time at which the sample is collected. Our review of 42 samples from 20 countries provided a combined prevalence of current smoking of 62%. More important than this average prevalence is the size of the association between schizophrenia and smoking when comparing schizophrenia patients with the general population, that is, the effect size. This effect size is measured by a meta-analysis’ overall OR (and its CI), 5.3 (4.9–5.7) (de Leon and Diaz 2005). This estimated average OR is not a “true” and stable measure of the association. The worldwide average OR has to be recalculated as new studies reflect changes in smoking prevalences in the general population of each country, and changes in the access to tobacco of people who are going to develop schizophrenia (de Leon et al. 2007a).

The tobacco epidemic throughout the world usually passes through five stages (early, rising, peak, declining and late stages). Different countries are usually in different stages and women tend to be at earlier stages than men. Since many people from the US general population have quit smoking, the US is currently in the declining period. Low-income countries are currently in the early stages (Anderson 2006). People with schizophrenia tend to be somewhat isolated from smoking reduction trends (de Leon et al. 2002b) and, after more than 20 years of studies of people with schizophrenia in several Western countries, most of our studies reflect very low rates of smoking cessation (<20%) in schizophrenia patients under naturalistic conditions (i.e., without treatment), which are probably typical in the majority of psychiatric settings. Only in our most recently published study of psychosis and smoking have we seen prevalences of smoking cessation >20% in psychotic patients (60% in males and 28% in females). This study included Spanish patients in their early stages of psychosis who were followed for 8 years (González-Pinto et al. 2011).

Association between SMIs and addictions

The concept of SMI usually includes schizophrenia and severe mood disorders (bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder), and may encompass nearly 3% of the US population in a 1-year period (National Advisory Mental Health Council 1993). In the US, people with schizophrenia and severe mood disorders are frequently treated in the public health system.

Based on our epidemiological approach, we proposed that a shared genetic vulnerability model may explain the high prevalence of smokers among people with schizophrenia (de Leon 1996). As further data veriWed that this association is consistent throughout the world, and that the increase in smoking initiation starts before schizophrenia starts, we have come to firmly believe that the shared vulnerability definitively reflects a genetic component (de Leon and Diaz 2005). From a different perspective which considers neurobiological data, Freedman et al. (1997) defended the view that this association may be explained by an association of schizophrenia with genetic variations in the α7 nicotine receptor gene. This genetic explanation has not been empirically confirmed but, more recently, Freedman and coworkers found abnormalities in the expression of these receptors in schizophrenia nonsmokers who were compared with controls; the abnormalities were not present in schizophrenia smokers (Mexal et al. 2010).

The self-medication hypothesis suggests that patients with SMIs select specific drugs to treat their psychiatric symptoms (Khantzian 1985). Schizophrenia patients usually get addicted to nicotine before their illness starts; thus it does not seem plausible that schizophrenia patients get addicted to nicotine to treat their illness. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that in some patients and in some circumstances patients who are smokers may smoke more to decrease symptoms or side effects such as akathisia (de Leon et al. 2006). Other reviews have also been critical of the self-medication hypothesis (Ziedonis et al. 2008). Prochaska et al. (2008) suggested that the tobacco industry's support for this hypothesis may explain why it has remained so popular in the literature and why other hypotheses have received less attention.

Study designs for exploring smoking behaviors in schizophrenia

This section focuses on two major issues that are crucial for designing studies of the association between schizophrenia and smoking: the deWnition of smoking behaviors and the selection of controls.

Defining smoking behaviors

In a simplified way, the association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking can mean (1) the frequency of smokers is higher in schizophrenia patients than in other people (“a higher percentage of them smoke”) and/or (2) schizophrenia smokers smoke more cigarettes daily than other smokers (“they smoke more cigarettes”). More precise meanings can be given by using testable hypotheses that compare schizophrenia patients with controls as follows: (1) “schizophrenia is associated with an increase in smoking”, and (2) “schizophrenia is associated with increased smoking among smokers”.

Those interested in genetics should know that the genetics of current daily smoking may not be a good study target. Current daily smoking reflects two addiction processes: (1) ever being addicted (or ever daily smoking), and (2) addiction persistence (lack of smoking cessation in ever daily smokers). Thus the association between schizophrenia and current daily smoking may not be particularly useful for those interested in completing genetic studies of schizophrenia and nicotine addiction. More interesting facts are the statistical association of schizophrenia with increased frequencies of ever daily smoking, and with decreased smoking cessation among ever daily smokers.

Selection of controls

Regarding studying control subjects, two major types of controls can be selected: non-psychiatric controls representing the general population and patients with other SMIs. Patients with other SMIs are a better comparison group than the general population in studies of schizophrenia patients. It is well established that psychiatric disorders are associated with high frequencies of smoking (Hughes et al. 1986; Covey et al. 1994; Lasser et al. 2000). This is particularly true for people with SMIs other than schizophrenia such as major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder, who exhibit greater frequencies of smoking than non-psychiatric controls in all large US epidemiological studies (Covey et al. 1994; Lasser et al. 2000; McClave et al. 2010). It is not surprising that only a few studies use patients with other SMIs since these studies usually have much less statistical power than studies using non-psychiatric controls. In a 2007 US survey the difference in age-adjusted prevalences of current smoking between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder was 12.7% (=59.1 – 46.4); in contrast, a difference of 40.8% (=59.1 – 18.3) between schizophrenia patients and non-psychiatric controls was observed (McClave et al. 2010).

Schizophrenia is associated with more smokers

This section focuses on the design of studies probing schizophrenia's association with more smokers. Six types of studies are possible, including those focused on (1) an increase in current smoking with respect to the general population; (2) an increase in current smoking with respect to other SMIs; (3) an increase in ever smoking with respect to the general population; (4) an increase in ever smoking with respect to other SMIs; (5) a decrease in smoking cessation in smokers with respect to the general population; or (6) a decrease in smoking cessation in smokers with respect to other SMIs.

Schizophrenia is associated with an increase in current smoking when compared with the general population

As described above, the prevalences of smoking in the general population vary across time and space. They also vary across schizophrenia patient samples, but perhaps less. Thus, it is more important to focus on effect sizes, quantifying the difference in prevalences between schizophrenia patients and controls and its stability. Our meta-analysis showed a very strong association between schizophrenia and current smoking (OR = 5.3) (see Table 1). Was this association consistent across countries? Yes, 40 of the 42 reviewed studies showed a significant association in the same direction (OR > 1, i.e., a smoking frequency higher in schizophrenia). Only two studies provided an OR < 1: a Colombian study also showing a low prevalence of smoking in the general population (Suárez et al. 1996), and a Japanese study with high smoking prevalences (Mori et al. 2003). These two studies reflect a “floor effect” and a “ceiling effect”, respectively. The association between schizophrenia and current smoking cannot be found if nobody smokes in the general population (0%, the floor), or if everybody smokes (100%, the ceiling). Based on our experience reviewing worldwide studies (de Leon and Diaz 2005), the floor and ceiling effects may occur at about 20 and 60% of current smoking in the general population, respectively (de Leon et al. 2007a). Thus, when only 20% of the population are current smokers, it is difficult to find an association unless confounding variables such as gender or educational (or socioeconomic) status are carefully controlled for and large samples are used. A Colombian schizophrenia sample that showed no significant differences when compared with published rates for the general population (Campo et al. 2004) became significantly different when compared with matched controls (OR = 3.1, CI 1.4–6.8) (Campo-Arias et al. 2006). At the time of the negative Japanese study (Mori et al. 2003), few women smoked (13%) and many males smoked (60%) in the Japanese general population. Thus, the Japanese schizophrenia study that did not show an association between smoking and schizophrenia (Mori et al. 2003) was contaminated by using published general population rates and not controlling for confounders and gender differences. In fact, in that Japanese study, schizophrenia females smoked significantly more than the general population (de Leon and Diaz 2005), and the association between schizophrenia and smoking in male smokers was limited by the ceiling effect of the male Japanese general population. A more recent Japanese study showed that after controlling for confounders it was also possible to demonstrate an association between schizophrenia and smoking in Japan (Shinozaki et al. 2010).

Table 1.

Summary of meta-analysis (de Leon and Diaz, 2005) on the association between schizophrenia and different smoking behaviors: odds ratios (ORs) and consistency

| Study consistencya |

Countries |

Average ORs (95% CI) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR > 1 | +Significant | Nb | Typec | Total sample | Male | Female | |

| ↑ Current smoking versus general population | 42 | 40/42 | 37/42 | 20 | Some non-Western | 5.3 (4.9–5.7) | ||

| 32 | 29/32 | 29/32 | 18 | Most Western | 7.2 (6.1–8.3) | |||

| 25 | 20/25 | 20/25 | 15 | Most Western | 3.3 (3.0–3.6) | |||

| ↑ Current smoking versus other SMIs | 18 | 17/18 | 14/18 | 9 | Most Western | 1.9 (1.7–2.1) | ||

| 14 | 11/14 | 11/14 | 8 | Most Western | 2.3 (2.0–2.7) | |||

| 8 | 6/8 | 3/8 | 5 | Western | 1.8 (1.5–2.3) | |||

| ↑ Ever smoking versus general population | 9 | 8/9 | 8/9 | 6 | Western | 3.1 (2.4–3.8) | ||

| 4 | 4/4 | 3/4 | 3 | Western | 7.3 (1.04–13.6) | |||

| 3 | 3/3 | 2/3 | 3 | Western | 2.8 (1.2–4.4) | |||

| ↑ Ever smoking versus other SMIs | 5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | 5 | Most Western | 2.0 (1.6–2.4) | ||

| 4 | 4/4 | 2/4 | 3 | Most Western | 2.0 (1.5–2.7) | |||

| 2 | 1/2 | 0/2 | 2 | Western | 0.92 (0.44–1.9) | |||

| ↓ Smoking cessation in ever smokers versus general population | 6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 5 | Western | 5.3 (4.2.–7.1) | ||

| 4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 3 | Western | 10.0 (7.1–16.7) | |||

| 3 | 3/3 | 2/3 | 3 | Western | 2.2 (1.5–4.3) | |||

| ↓ Smoking cessation in ever smokers versus other SMIs | 4 | 3/4 | 1/4 | 4 | Western | 1.8 (1.1–3.0) | ||

| 4 | 4/4 | 3/4 | 3 | Most Western | 2.9 (1.9–13.4) | |||

| 2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 2 | Western | 0.37 (0.11–1.3) | |||

CI 95% confidence interval

N, number of studies; OR > 1, number of individual studies with OR > 1 divided by N; +Significant, number of individual studies with significant OR > 1 divided by N

N number of countries

USA, Canada, European countries, and Israel are considered Western countries

Changes in the smoking epidemic have been heavily influenced by gender and economic factors (Anderson 2006). To present a simplified version of the tobacco epidemic's chronology, it must be noted that in Western countries gender differences were obvious in the first half of the twentieth century since few females smoked, but the differences have decreased since then. In non-Western countries, female smoking continues to be rare but is increasing, and the bulk of the tobacco business appears to be moving to Asian males (Anderson 2006).

If one believes that gender differences in smoking are important, one needs to acknowledge that ORs using the general population as a control are poor measures of association unless they are adjusted for gender. Nonetheless, ORs stratified by gender may be the best way of describing the association between schizophrenia and current smoking throughout the world. In our meta-analysis, the overall male OR for current smoking was 7.2 (Table 1). More importantly, out of the 32 studies that provided male ORs, three provided ORs < 1; however, these three studies were conducted in non-Western countries, probably with ceiling effects. Samples matched for socioeconomic and educational status may be needed to detect the association in countries with ceiling effects. In the meta-analysis, the overall female OR was 3.3 (Table 1). Five of the 25 studies that provided female ORs provided ORs < 1. These studies were conducted in Western countries with floor effects; again, matched studies may be needed to detect the association (de Leon and Diaz 2005).

Schizophrenia may be associated with an increase in current smoking when compared with other SMIs

When comparing schizophrenia with other SMIs, our meta-analysis produced an overall OR of 1.9 (de Leon and Diaz 2005). The male OR was 2.3. The female OR was 1.8 but only 3 of 8 studies had significant ORs >1 (Table 1). Unfortunately, few of the studies comparing schizophrenia with other SMIs have controlled for other addictions. In Western countries, alcohol and drug addictions are strongly associated with current smoking. In the US and other Western countries, other addictions may also be associated with SMIs, in general, and with schizophrenia in particular. Thus, methodologically sound studies trying to establish the association between schizophrenia and smoking need to control for the confounding effects of gender and substance use disorders. Few published studies have controlled for these confounders (de Leon et al. 2002b, 2005).

Is schizophrenia associated with increased ever smoking when compared with the general population?

The meta-analysis’ overall OR was 3.1 (de Leon and Diaz 2005). The male OR was 7.3 and the female OR was 2.8 (Table 1). The reviewed studies did not control for confounders such as level of education. In a more recent US study using ever daily smoking as a definition of ever smoking and non-psychiatric controls, there was a significant association of ever smoking with schizophrenia after controlling for confounders (OR = 5.2; CI 3.6–7.8) (de Leon et al. 2007a). This large OR may be partly explained by factors associated with schizophrenia that are not well controlled by using non-psychiatric controls (e.g., the presence of other addictions). Using the general population as a control does not allow the possibility of adjusting for other addictions since other addiction levels in the general population are low and, therefore, difficult to represent in general population samples.

By using survival analyses that were focused on age at onset of daily smoking and controlled for confounders, we have specifically explored the timing in the association of schizophrenia with an increased initiation of daily smoking in three studies (two in the US and one in Spain). The three studies (de Leon et al. 2002a; Gurpegui et al. 2005; Diaz et al. 2008) replicated that (1) when compared with non-psychiatric controls, schizophrenia was associated with a significant increase in initiation of ever daily smoking after controlling for education and gender; and (2) non-psychiatric smokers showed a pattern of getting addicted in their teens, with very few people getting addicted in their late 20s; in contrast, schizophrenia patients continue to be at risk of becoming addicted after the age of 20. By focusing only on people who started daily smoking 5 years before illness onset, two of the studies (Gurpegui et al. 2005; Diaz et al. 2008) demonstrated that the differences between schizophrenia patients and non-psychiatric controls were not explained by the prodromal effects of schizophrenia illness. A study of Chinese male schizophrenia patients replicated the association of schizophrenia with increased initiation of daily smoking, by focusing on individuals who started to smoke 5 years before illness onset (Zhang et al. 2010).

Is schizophrenia associated with increased ever daily smoking when compared with other SMIs?

The meta-analysis overall OR was 2.0 and significant for the total and male samples but did not reach significance in female samples (Table 1). The average rates of lifetime smoking in schizophrenia patients were 69% for the total samples, 83% for males, and 65% for females (de Leon and Diaz 2005). These studies did not control for some confounders such as level of education and substance use disorders. In a more recent US study of ever daily smoking, there was a significant association of ever daily smoking with schizophrenia after controlling for confounders, OR = 1.9 (CI 1.2–2.8) (de Leon et al. 2007a).

Our survival analyses of age at onset of daily smoking which controlled for confounders suggest that severe mood disorders have an intermediate position between schizophrenia and non-psychiatric controls in the risk of becoming an ever daily smoker, but the sample sizes were not sufficient to establish a significant difference between schizophrenia and mood disorders (de Leon et al. 2002a; Diaz et al. 2008).

Is schizophrenia associated with decreased smoking cessation in ever smokers when compared with the general population?

The meta-analysis overall OR for lack of smoking cessation for the total samples of ever smokers was 5.3. The male and female ORs were 10.0 and 2.2, respectively (Table 1). These studies did not control for other confounders. In a more recent US study that defined smoking cessation as not smoking for 1 year after being an ever daily smoker, which used non-psychiatric controls, there was a significant association between schizophrenia and a lack of smoking cessation after controlling for confounders (OR = 5.6; CI 3.4–9.1) (de Leon et al. 2007a).

The stronger predictors of failing to quit smoking are probably heavy smoking and high nicotine dependence. As schizophrenia is strongly associated with heavy smoking and possibly with high nicotine dependence (see next section), the most reasonable explanation for the association between schizophrenia and lack of smoking cessation is the high levels of nicotine dependence in schizophrenia patients. Before considering genetic factors as a possible explanation for the decreased smoking cessation in smokers with schizophrenia, one needs to consider the association between schizophrenia and high nicotine dependence in smokers.

Naturalistic studies indicate that smoking cessation in schizophrenia smokers is low (<10 or 20%) when no special treatment is provided. Due to the high levels of dependence, intensive programs are needed to help schizophrenia patients to stop smoking (Ziedonis and George 1997). According to the clinical trials literature, the only interventions that have proven to be somewhat effective in reducing smoking in schizophrenia are bupropion and contingent reinforcement (Tsoi et al. 2010).

Is schizophrenia associated with decreased smoking cessation in ever smokers when compared with other SMIs?

The limited number of studies and their limited sample size make it difficult to draw any reliable conclusion about the association between smoking cessation and schizophrenia when comparing schizophrenia patients with other SMIs (Table 1). In the more recent and larger of our US studies, which used controls with other SMIs and defined smoking cessation in an ever daily smoker as not having smoked for 1 year, there was no significant association between a lack of smoking cessation and schizophrenia after controlling for confounders, (OR = 1.2; CI 0.68–2.1) (de Leon et al. 2007a).

Is schizophrenia associated with more smoking in smokers?

An old review (Lohr and Flynn 1992) described clinicians’ experience that schizophrenia smokers appear to smoke more cigarettes and be more addicted than other smokers. Since then, this statement has been continuously repeated in the literature. This section focuses on the design of studies testing the hypothesis that schizophrenia is associated with more smoking in smokers. Four types of studies are possible, focusing on (1) the increase in heavy smoking in schizophrenia smokers with respect to smokers from the general population; (2) the increase in heavy smoking in schizophrenia smokers with respect to smokers with other SMIs; (3) the high levels of nicotine dependence in schizophrenia smokers compared with smokers from the general population; or (4) the high levels of nicotine dependence in schizophrenia smokers compared with smokers with other SMIs. A somewhat connected hypothesis that is reviewed in the fifth subsection is whether heavy smoking in schizophrenia is associated with poorer prognosis in schizophrenia or not.

Is schizophrenia associated with increased heavy smoking within smokers when compared with the general population?

Published studies have used different definitions of heavy smoking, making it impossible to provide an average OR. However, they tend to suggest that schizophrenia smokers consistently smoke more than the smokers in the general population. In our meta-analysis, the male ORs ranged from 2.0 to 7.4, and the female ORs from 2.0 to 8.8 (de Leon and Diaz 2005). A US study controlling for gender, education, race, and age (OR = 2.9; CI 1.5, 5.6; Diaz et al. 2008) indicated that heavy smoking was significantly more frequent in schizophrenia smokers (42%) than in smokers without psychiatric disorders (14%).

Only a few studies have used biological methods to establish the possibility that schizophrenia smokers may have higher nicotine metabolite levels than other smokers without psychiatric disorders (Olincy et al. 1997; Strand and Nybäck 2005; Weinberger et al. 2007; Williams et al. 2005, 2010). It may be hard to definitively establish this fact, unless large studies of representative samples of smokers with schizophrenia and smokers without psychiatric disorders are completed and confounders are controlled. Not surprisingly, a urine level study did not find differences after controlling for the number of cigarettes smoked since they were controlling for smoking intensity (Bozikas et al. 2005).

Is schizophrenia associated with increased heavy smoking within smokers when compared with other SMIs?

The use of different heavy smoking definitions has made it impossible to provide an average OR when comparing heavy smoking in schizophrenia smokers versus smokers with other SMIs. The differences tend to be small and non-significant, with approximately 2/3 of ORs > 1 and 1/3 of them <1. In our more recent US study the prevalence of heavy smoking within smokers was slightly higher in schizophrenia than in mood disorders (42 vs. 33%), but the difference was not significant after controlling for confounders (OR = 1.6; CI 0.94, 2.6; Diaz et al. 2008). There are no studies using biological measures comparing smokers with schizophrenia versus smokers with other SMIs.

Is schizophrenia associated with higher levels of nicotine dependence within smokers when compared with the general population?

Studies controlling for confounders and using measures of nicotine dependence based on the FTND (Gurpegui et al. 2005; Diaz et al. 2008) indicate that schizophrenia patients who smoke are probably more dependent than smokers without psychiatric disorders. More interesting are three small studies (Tidey et al. 2005; Lo et al. 2011; Williams et al. 2011) reporting that when schizophrenia patients who smoke are matched to other highly dependent smokers, the former crave nicotine more; this is something that has been suspected for years (Mckee et al. 2009; Weinberger et al. 2007).

Is schizophrenia associated with higher levels of nicotine dependence within smokers when compared with other SMIs?

We currently have good information from several countries showing that SMIs in general are consistently associated with higher levels of nicotine dependence than smokers from the general population (de Leon et al. 2002c, 2003; Diaz et al. 2009), but there is no definitive data showing that schizophrenia smokers smoke more or are more dependent than smokers with other SMIs. The small observed differences and the inconsistency of the results indicate that very large samples may be needed to settle this question.

In Western countries, heavy smoking and high nicotine dependence are also frequent in alcoholics and drug abusers. In a study of a treatment program for quitting smoking, alcoholism and schizophrenia were associated with poor outcomes (Gershon Grand et al. 2007). The only published comparison that we have found of nicotine dependence in smokers with schizophrenia versus smokers treated for alcohol and/or drug addictions is a Canadian study in an inpatient unit (Solty et al. 2009). The study included 84 psychotic patients (only 73%, 62/84, with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder) and 31 with primary diagnosis of addiction. The prevalences (uncorrected for gender) of current smoking were 55 and 77%, and of high dependence (FTND ≥ 6) were 47 and 65%, respectively (Solty et al. 2009).

Is smoking associated with worse prognosis within schizophrenia patients?

Another way of exploring the relationship between schizophrenia and heavy smoking is to compare the psychiatric outcome of schizophrenia patients who are heavy smokers with that of schizophrenia patients who are not, controlling for other factors that may influence prognosis. Many of the studies that provided high percentages of smoking in schizophrenia, 80–90%, were completed in long-term hospitals. This suggests that institutionalized patients, who usually have the worst prognoses, were more prone to smoke (de Leon and Diaz 2005). The few limited studies that have systematically explored the association between smoking and schizophrenia outcome indicate that smokers (compared to non-smokers) or heavy smokers (compared with mild smokers and non-smokers) tend to have poorer longitudinal prognoses (Aguilar et al. 2005; Salokangas et al. 2006; Kobayashi et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2010; Segarra et al. 2011). Please be aware that these results go directly against the idea of self-medication. If smoking is helpful, heavy smokers should have better prognosis than mild smokers or non-smokers. Many more studies controlling for confounding variables are needed to establish an association between smoking or heavy smoking in smokers and worse prognosis. If this fact is established by new studies, it may make sense to consider the hypothesis of allostasis. Kolb and Le Moal (1997) proposed that the organism tries to counteract the effects of a given drug through a vicious cycle in which the point where pleasure is achieved continuously changes in response to the administration of that drug. They argue that drug addiction results from dys-regulation of reward mechanisms and subsequent allostasis (chronic perturbation of brain reward homeostasis, in which stability can only be reached through change). Following the concept of allostasis, heavy smoking in schizophrenia may be a no-win situation associated with a major disturbance of the brain's compensatory systems, which are unable to adjust themselves despite patients’ attempts to smoke heavily in order to adjust them (de Leon et al. 2005).

A proposed approach to studying the association between schizophrenia and smoking

This section begins with a summary of the complex information from epidemiological studies described in the two prior sections; it is followed by subsections on the implications of using SMI or non-psychiatric controls in these studies, and on our proposed study approach. Based on the above epidemiological information, we propose an approach to studying the association between schizophrenia and ever daily smoking. The main idea is to compare schizophrenia patients with non-psychiatric and bipolar controls by using a complex set of hierarchical hypotheses that will allow us to select consistently associated genes.

Summary of the epidemiological literature with a focus on planning genetic studies

Table 2 briefly summarizes the data supporting an association between schizophrenia and the various definitions of smoking behavior. In spite of the fact that there are more than 1,000 articles on the subject, the only association that appears to be definitively established is that of an increase in current smoking when compared with the general population. Unfortunately, many of the published studies do not provide data that allow investigating other definitions of smoking behavior. In particular, few studies report ever daily smoking rates. The limited available data suggest that for genetic studies, the best hypothesis is that schizophrenia is associated with an increase in ever daily smoking (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between smoking behaviors and schizophrenia: a summary focused on various definitions and their potential for genetic studies

| Smoking behavior deinition | Control | Results | Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| ↑ Current daily smoking | General population | Very strong and consistent association worldwide | Complex: ↑initiation and/or ↓ cessation |

| Other SMIs | Good, but limited data from non-Western countries | Complex: ↑initiation and/or ↓ cessation | |

| ↑ Ever daily smoking | General population | Good, but no data from non-Western countries | Differences partly due to SMI confounders |

| Other SMIs | Supported by very few Western studies | Best potential | |

| ↓ Cessation in daily smokers | General population | Supported by very few Western studies | Diferences may be due to heavy smoking |

| Other SMIs | No data in favor: it may not be true | No proof of association | |

| ↑ Heavy smoking in daily smokers | General population | Supported by a few Western studies | Diferences partly due to SMI confounders |

| Other SMIs | Few inconsistent studies | No proof of association | |

| ↑ Nicotine dependence in smokers | General population | Supported by a few Western studies | Diferences partly due to SMI confounders |

| Other SMIs | Few inconsistent studies | No proof of association |

SMI severe mental illness

Schizophrenia is a complex trait that results from genetic and environmental etiologic influences. As a matter of fact, it is unrealistic to consider it an etiologically homogenous entity (Kendler and Schaffner 2011). A meta-analysis of the twin literature indicates that schizophrenia heritability is 85% (73–90%) (Sullivan et al. 2003). The recent schizophrenia GWAS studies support a combination of rare and common genetic variations, a major role for polygenic inheritance, and a genetic overlap of schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder (Gejman et al. 2011). As smoking does not cause schizophrenia and the association of ever daily smoking with schizophrenia appears to indicate a shared vulnerability, this association can be used to explore a set of genes that may be associated with both schizophrenia and nicotine addiction.

Selecting SMI controls versus non-psychiatric controls

Non-psychiatric controls are likely to have much lower rates of ever daily smoking than schizophrenia patients. According to our meta-analysis of the few studies comparing schizophrenia with the general population in Western countries, the meta-analysis overall ORs are high: 7.3 for males, and 2.8 for females (Table 1). These large effect sizes suggest that future studies performing this comparison will have high statistical power.

The smaller difference between schizophrenia and SMIs will provide much lower statistical power but the authors believe that using controls with SMIs helps to eliminate some of the non-genetic confounders that may contribute to the association. People with SMIs and schizophrenia have been exposed to similar environments and treatments and are not likely to show differences in educational or socioeconomic status. Thus, according to our meta-analysis from a few studies comparing schizophrenia with other SMIs in Western countries, the ORs we expect to find will be lower than those comparing schizophrenia with the general population; the meta-analysis overall male OR was 2.0 and the female OR from two studies was non-significant (Table 1).

Therefore, SMI patients may be better controls than non-psychiatric subjects, but their inclusion in a study as controls will probably be accompanied by a reduction in statistical power. SMI patients used as controls may bring an additional set of problems since they may have the genetic abnormalities associated with SMIs in general or with a specific SMI. If one believes that including all severe mood disorders together in a genetic study is not a good idea, and that major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder have very different genetic underpinnings, one can use only one of these two SMIs as a control group. Tables 3 and 4 provide a new review of the literature that allowed estimating the differences in ever smoking between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, OR = 1.6 (1.1–2.2) (Table 3), and between schizophrenia and major depressive disorder, OR = 1.8 (1.2–2.7) (Table 4). These meta-analysis overall ORs were calculated using two types of studies: some were using research diagnoses and others clinical diagnoses. Obviously a good comprehensive genetic study may benefit from the use of the more accurate research diagnoses rather than clinical diagnoses. But it is also important to keep in mind that the studies that were used to estimate the differences between schizophrenia and mood disorders (Diaz et al. 2009) and ORs and PARs (de Leon et al. 2005) as described in Table 5 used the less accurate clinical diagnoses.

Table 3.

Odds ratios (ORs) comparing frequencies of ever smoking in patients with schizophrenia versus bipolar disorder

| Authors | Country | Type | Schizophrenia | Bipolar disorder | OR | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever smoking in samples including both genders | ||||||

| Döme et al. (2005) | Hungary | Outpatients | 75% (91/122) | 70% (42/60) | 1.3 | (0.63, 2.5) |

| Itkin et al. (2001) | Israel | Outpatients | 55% (35/64) | 60% (42/70) | 0.83 | (0.40, 1.6) |

| de Leon et al. (2002a) | USA | Inpatients | 91% (62/68) | 83% (24/29) | 2.1 | (0.59, 7.7) |

| Diaz et al. (2009) | USA | In/outpatients | 83% (215/258) | 74% (73/99) | 1.8 | (1.02, 3.1) |

| Total of 4 samples | 3 Countries | 79% (403/512) | 70% (181/258) | 1.6 | (1.1, 2.2) | |

| Ever smoking in males | ||||||

| Döme et al. (2005) | Hungary | Outpatients | 74% (46/62) | 77% (20/26) | 0.83 | (0.29, 2.5) |

| Itkin et al. (2001) | Israel | Outpatients | 71% (22/31) | 62% (20/32) | 1.5 | (0.50, 4.2) |

| de Leon et al. (2002a) | USA | Inpatients | 95% (41/43) | 88% (14/16) | 2.9 | (0.37, 25.0) |

| Diaz et al. (2009) | USA | In/outpatients | 86% (127/148) | 87% (40/46) | 0.91 | (0.34, 2.4) |

| Total of 4 samples | 3 Countries | 83% (236/284) | 78% (94/120) | 1.4 | (0.77, 2.3) | |

| Ever smoking in females | ||||||

| Döme et al. (2005) | Hungary | Outpatients | 75% (45/60) | 65% (22/34) | 1.6 | (0.67, 4.0) |

| Itkin et al. (2001) | Israel | Outpatients | 39% (13/33)a | 58% (22/38) | 0.48 | (0.18, 1.22) |

| de Leon et al. (2002a) | USA | Inpatients | 84% (21/25) | 77% (10/13) | 1.6 | (0.29, 8.3) |

| Diaz et al. (2009) | USA | In/outpatients | 80% (88/110) | 62% (33/53) | 2.4 | (1.2, 5.0) |

| Total of 4 samples | 3 Countries | 73% (167/228) | 63% (87/138) | 1.6 | (1.0, 2.5) | |

CI 95% confidence interval

The study included a small subsample of female schizophrenia patients with an unusual ethnic background who smoked less than the Israeli female general population

Table 4.

Odds ratios (ORs) comparing frequencies of ever smoking in patients with schizophrenia versus major depressive disorder

| Author | Country | Type | Schizophrenia | Major depressive disorder | OR | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever smoking in samples including both genders | ||||||

| Döme et al. (2005) | Hungary | Outpatients | 75% (91/122) | 70% (64/92) | 1.3 | (0.70, 2.3) |

| de Leon et al. (2002a) | USA | Inpatients | 91% (62/68) | 73% (16/22) | 3.9 | (1.1, 13.6) |

| Diaz et al. (2009) | USA | In/outpatients | 83% (215/258) | 75% (50/67) | 1.7 | (0.90, 3.2) |

| Total of 3 samples | 2 Countries | 82% (368/448) | 72% (130/181) | 1.8 | (1.2, 2.7) | |

| Ever smoking in males | ||||||

| Döme et al. (2005) | Hungary | Outpatients | 74% (46/62) | 75% (24/32) | 0.96 | (0.36, 2.6) |

| de Leon et al. (2002a) | USA | Inpatients | 95% (41/43) | 87% (13/15) | 3.2 | (0.40, 24.7) |

| Diaz et al. (2009) | USA | In/outpatients | 86% (127/148) | 74% (17/23) | 2.1 | (0.76, 6.0) |

| Total of 3 samples | 2 Countries | 85% (214/253) | 77% (54/70) | 1.6 | (0.85, 3.1) | |

| Ever smoking in females | ||||||

| Döme et al. (2005) | Hungary | Outpatients | 75% (45/60) | 67% (40/60) | 1.5 | (0.68, 3.3) |

| de Leon et al. (2002a) | USA | Inpatients | 84% (21/25) | 43% (3/7) | 7.0 | (1.1, 44.1) |

| Diaz et al. (2009) | USA | In/outpatients | 80% (88/110) | 75% (33/44) | 1.3 | (0.58, 3.0) |

| Total of 3 samples | 2 Countries | 79% (154/195) | 68% (76/111) | 1.7 | (1.02, 2.9) | |

CI 95% confidence interval

Table 5.

Adjusted odds ratios (ORs), their confidence intervals (CIs) and population attributable risks (PARs) for ever smoking

| Factor | Adjusted OR (CI) | Prevalence (P), (%) | PAR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| In the general population (de Leon et al. 2007b)a | |||

| Lifetime alcohol use (USA, 1992) | 6.2 (4.4–8.8) | 88 | 82 |

| Lifetime alcohol use (USA, 1996) | 9.8 (7.5–12.8) | 88 | 89 |

| Lifetime alcohol use (Basque country,b 1992) | 3.0 (2.3–3.9) | 86 | 63 |

| Lifetime alcohol use (Basque country,b 1996) | 2.6 (2.1–3.3) | 83 | 57 |

| In patients with severe mental illness (SMI) (N = 550; de Leon et al. 2005)c | |||

| Lifetime alcohol use disorder | 3.6 (2.2, 6.0) | 64 | 52 |

| Lifetime drug use disorder | 3.1 (1.8, 5.4) | 52 | 38 |

| Schizophrenia | 2.0 (1.3, 3.2) | 28 | 21 |

| High school or lower educational level | 2.1 (1.3, 3.3) | 71 | 33 |

| Non-obesity (BMI < 30) | 1.6 (2.6, 1.04) | 54 | 17 |

In patients with SMI, ever smoking was deined as ever daily smoking (clinical deinition). In the general population, ever smoking also included non-daily smokers, so the definition was slightly wider (epidemiological definition). A prior article described the differences and overlap between these two deinitions (Diaz et al. 2009)

For data from the general population, the population attributable risk was computed as (P/100) × (OR – 1)/{(P/100) × (OR – 1) + 1} (Bolton and Robinson 2010)

Basque country is located in the North of Spain

In patients with severe mental illness, the population attributable risk for a particular factor was adjusted for the other described factors. Covariate-adjusted attributable risks were computed by using Stata’ aflogit command (StataCorp 2009; Greenland and Drescher 1993)

We believe that bipolar disorder is a more reasonable choice as a control in schizophrenia studies than major depressive disorder since it is a more homogenous concept, and is frequently associated with psychosis and chronic antipsychotic treatment. Unfortunately, the limited data from four published studies indicate that increased ever smoking in schizophrenia compared with bipolar disorder is probably small, with an average OR = 1.6 (Table 3), which would require hundreds of patients to prove a significant difference in a genetic factor.

Major depressive disorder appears to be a less reasonable choice because it is a less homogenous concept than bipolar disorder, and is rarely associated with psychosis or chronic antipsychotic treatment. On the positive side, the prevalence of major depressive disorder in the general population is much higher than that of bipolar disorder, and the former disorder may have a slightly weaker association with smoking than the latter. Thus, if this weaker association is true, a study using patients with major depressive disorder may have more statistical power than a study of comparable sample size with bipolar patients. In the majority of cases, nicotine addiction begins before depression develops (Rohde et al. 2003, 2004). In a US female twin study, Kendler et al. (1993) found that ever daily smoking and lifetime major depression share some vulnerability, which is probably explained by genetic factors. In a Swedish twin study, Edwards et al. (2011) found a similar shared genetic vulnerability in males, and shared genetic and unique environmental influences in females. Since in epidemiological studies the association between major depressive disorder and nicotine addiction is weaker than that between schizophrenia and nicotine addiction, we suspect that major depressive disorder shares a smaller amount of genetic variability with nicotine addiction than does schizophrenia. Moreover, in our sample of US patients with SMIs, neither major depressive disorder nor bipolar disorder were associated with ever daily smoking within patients with SMIs after correcting for other addictions (de Leon et al. 2005). However, the association between schizophrenia and ever daily smoking was significant after controlling for addictions. Thus, it is possible that the association between severe mood disorders (bipolar and major depressive disorders) and nicotine addiction may merely reflect that (1) severe mood disorders are also associated with other addictions, and (2) other addictions are associated with ever daily smoking. Thus, the associations between severe mood disorders and ever daily smoking may not survive the control for other addictions (Black et al. 1999; Rohde et al. 2003, 2004) and high smoking rates in severe mood disorders may be mainly explained by comorbid addictions (Lawrence et al. 2009).

Another factor confounding the association between depression and smoking is suggested by the self-medication hypothesis. Although we do not believe that the self-medication hypothesis satisfactorily explains the association between schizophrenia and tobacco addiction, there is some evidence suggesting that it may explain the difficulties with smoking cessation that depressed patients have. In non-smokers nicotine appears to be an antidepressant (Salin-Pascual et al. 1996). Tobacco smoke inhibits monoamine oxidase (MAO) activity through epigenetic mechanisms. Drugs that are MAO inhibitors are antidepressants, so it is possible that smoking may have some antidepressant effects through this inhibition (Rendu et al. 2011). Some vulnerable patients with a history of recurrent depression may become depressed when they stop smoking (Covey et al. 1998), but not all studies agree with this hypothesis (Hitsman et al. 2003). More recently, one of the large US epidemiological surveys suggested that patients with mood disorders are more prone to experience tobacco withdrawal symptoms and distress (Weinberger et al. 2010); a clinical trial suggested that patients with history of depression have lower expectations of quitting (Weinberger et al. 2011), and, according to an epidemiological study, there are complex interactions between depression and obesity in female ever smokers (Widome et al. 2009). Twin studies indicate that psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder, may worsen nicotine withdrawal, which may contribute to lower smoking cessation rates (Xian et al. 2005; Edwards and Kendler 2011).

A study approach to searching for genes that explain the increased ever daily smoking seen in schizophrenia

Ever daily smoking may be associated with hundreds of thousands of genes of modest effects, but we are interested in those shared with schizophrenia. Exploring the association of schizophrenia with ever daily smoking using GWAS with millions of genetic variations may provide many false positives. To reduce the false positives due to chance, we propose to follow a study approach that uses a set of hypotheses developed after reviewing epidemiological data. This study approach can be used in an exploratory GWAS with millions of genetic variations or in a more focused candidate gene approach using thousands of genes selected a priori. Thus, the design (GWAS versus candidate gene study) will determine the number of genetic variations tested and the sample size. The recruited sample for any study testing the first-stage hypotheses can easily be used to test the second- and third-stage hypotheses.

To best explore the genetics of the association between ever daily smoking and schizophrenia, one can use simultaneously non-psychiatric controls and controls with other SMIs to take advantage of the progressive increase in ever daily smoking prevalence seen from non-psychiatric controls to schizophrenia, with other SMIs (e.g., bipolar disorder) having intermediate prevalences. The essence of our approach is that if an individual genetic variation is truly involved in the association between schizophrenia and smoking, then we expect that this variation rejects simultaneously a set of carefully selected null hypotheses that should be false according to epidemiological studies. Since the chance is very small that all hypotheses are rejected simultaneously with a genetic variation that is not truly involved in the association, the type I error of a study following our approach will be small and, therefore, the chance of obtaining many false positives is substantially reduced. For illustration purposes, it is assumed that a nominal (uncorrected) significance level of α = 0.01 is used to test each null hypothesis described below. This level is selected according to the preference of the investigators.

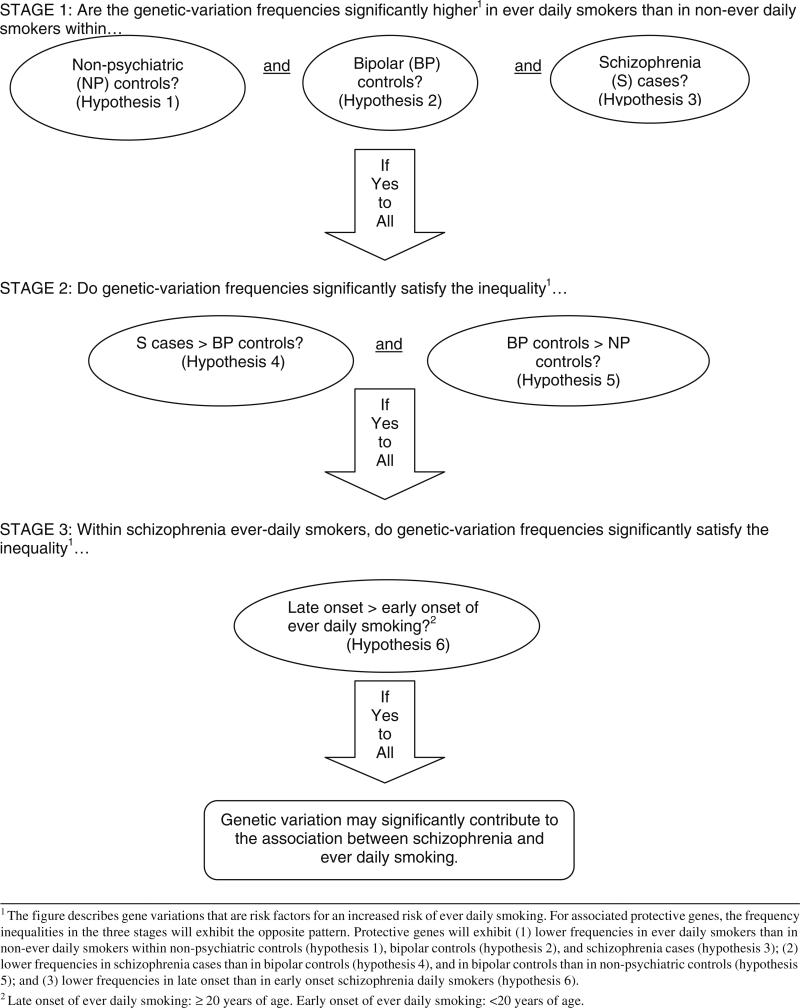

In the first stage of our approach (Fig. 1), only genetic variations associated with ever daily smoking versus non-ever daily smoking will be selected that are significant at the nominal level simultaneously within the non-psychiatric controls, the bipolar disorder controls, and the schizophrenia cases. That is, for a particular genetic variation, three null hypotheses of no association between the genetic variation and ever daily smoking are tested, one for each of the three subject groups. Provided that confounders such as gender or socioeconomic status are controlled for in the test procedure, if the genetic variation is not involved in ever daily smoking, the probability that the three null hypotheses are rejected simultaneously will be at most α3 = 10–6.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of a proposed three-stage approach for searching genes explaining the increased risk of ever daily smoking seen in schizophrenia

In the second stage of our approach (Fig. 1), only those genetic variations that were significant in each of the tests of the three above null hypotheses will be examined. The prevalence of these variations increasing the risk of smoking in schizophrenia would have to be significantly higher in schizophrenia than in bipolar disorder and, simultaneously, significantly higher in bipolar disorder than in controls. If a genetic variation is not involved in the association between schizophrenia and ever daily smoking, the possibility that it is selected in both the first and second stage, that is, the possibility that it simultaneously produces five significant tests is at most α5 = 10–10, provided confounders have been controlled for. The reason is that, for an irrelevant genetic variation, we do not expect that a non-significant result in the comparison of schizophrenia patients with bipolar patients changes our nominal probability of type I error in the comparison of bipolar patients with non-psychiatric controls.

The positively associated gene variations that were selected in both the first and second stages will be entered into a third stage (Fig. 1). According to epidemiological findings, each of these gene variations will need to have a significantly higher prevalence in people with schizophrenia who started daily smoking after the age of 20 than in people with schizophrenia who had an early start (20 years or younger). According to our more recent US study with 235 schizophrenia patients (de Leon et al. 2006; Diaz et al. 2008), we estimate that 16.6% will be never daily smokers, 58.3% ever daily smokers with early onset of daily smoking (<20 years of age) and 25.1% ever daily smokers with late onset of daily smoking (≥20 years of age). If appropriate confounders are controlled for, the possibility that an irrelevant genetic variation is selected simultaneously in all three stages will therefore be, at most, 10–12.

The prior description refers to genetic variations associated with increased risk. Protective gene variations will have opposite patterns: (1) in the first stage, significantly lower gene-variation prevalences in ever daily smokers than in non-ever daily smokers will be simultaneously observed within the non-psychiatric controls, the bipolar disorder controls and the schizophrenia cases; (2) in the second stage, a significantly lower prevalence in schizophrenia than in bipolar disorder and, simultaneously, a significantly lower prevalence in bipolar disorder than in non-psychiatric controls will be observed; and (3) in the third stage, a significantly lower prevalence will be observed in people with schizophrenia who started daily smoking after the age of 20 in comparison with people with schizophrenia who had an early start (20 years or younger).

Thus, although the nominal significance level for testing each individual hypothesis is 0.01, the nominal significance level for our 3-stage approach with 6 hypotheses will be much smaller, 10–12. Since many genetic variations will be examined, correction of p values for multiple comparisons at each individual hypothesis testing can be performed if desired. Our approach, however, will still reduce the final probability of type I error in this case by raising the corrected significance level to a power of about 6 and will also produce a set of candidate genes that are meaningful from an epidemiological point of view, not just from a statistical-significance perspective.

Association between nicotine and alcohol addictions

The aim of our study approach was to build a genetic psychiatric explanation of the comorbidity of schizophrenia and nicotine addiction. To fully understand our approach, it is necessary to pay attention to other psychiatric comorbidities, particularly alcohol and drug addictions. This section focuses on the association between nicotine and alcohol addictions and the next one between nicotine and drug addictions.

Alcohol is widely used in many countries, although it is used in smaller proportions in the Middle East, Africa and China (Anderson 2006; Degenhardt et al. 2008). According to the National Epidemiology Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) study in the US, the prevalence of alcohol addiction during the 12 months prior to the study was 8.5% (12.4% in men and 4.5% in women; Grant et al. 2004).

The following issues are reviewed below in subsections: (1) the genetics of nicotine and alcohol addiction, (2) the association between tobacco and alcohol use in the general population, (3) the association between nicotine and alcohol addictions in clinical samples, and (4) the association between schizophrenia and alcohol addiction.

Genetics of tobacco and alcohol use or addiction

Tobacco and alcohol use and their addictions are associated in the general population of Western countries. The use of alcohol and tobacco may be related in two ways: (1) intrapersonal linkage (alcohol drinkers usually smoke and vice versa) and (2) situational linkage (people who use alcohol and tobacco may use them together in the same situations) (Schiffman and Balabanis 1995). To explain these links genetic, coping, pharmacological, learning, personality, and cultural factors have been proposed (Niaura and Shiffman 1995; Bien and Burge 1990; Room 2004). The intrapersonal linkage has interest for geneticists. Any intrapersonal linkage has the potential of being explained by genetic factors. There is good information on the genetics of alcohol addiction but there is less understanding on the genetics of alcohol use. Two facts are important: (1) polymorphisms that decrease alcohol metabolism have major effects on alcohol use and therefore are protective for alcohol addiction (they are frequent in Asian populations but rare in European and African populations) (Bierut 2011), and (2) US twin studies indicate that familial and social factors are important determinants of alcohol use (Kendler et al. 2011). This is in contrast with alcohol addiction, where genetic and temperamental factors are more critical (Kendler et al. 2011).

The estimates of the heritability of alcohol addiction are 51–65% in females and 48–73% in males (Tyndale 2003). It has been suggested that genetic influences explain a substantial portion of the covariance of nicotine and alcohol addictions (Swan et al. 1990, 1997; Lessov-Schlaggar et al. 2006). In contrast with GWAS studies of nicotine addiction, GWAS studies of alcohol addiction have not yet provided robust findings (Bierut 2011).

Association between tobacco smoking and alcohol use in the general population

In the US, epidemiological studies have demonstrated that tobacco and alcohol addictions are associated to the point that smoking status can be used as a possible marker of alcohol addiction (McKee et al. 2007) and that the severity of tobacco addiction increases with the severity of alcohol addiction (Falk et al. 2006). In the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) study (Lasser et al. 2000), alcohol addiction was present in 22% of the general population versus 66% of ever smokers and was significantly associated with ever smoking. However, the analysis did not control for other psychiatric disorders. As far as we know, there are no meta-analyses of the association between alcohol and tobacco use that summarize the epidemiological studies throughout the world and provide an idea of this association's variability.

Alcohol use varies widely in non-Western countries probably due to cultural and biological differences. Thus, shared genetic vulnerability between alcohol and nicotine use should vary widely across the world. The next two paragraphs summarizing epidemiological studies (de Leon et al. 2005) provide support to the finding from twin studies, that non-genetic factors may be crucial for understanding alcohol use and, therefore, its interaction with nicotine use in the general population.

When using epidemiological studies on alcohol and nicotine use as a guide for genetic studies, three key issues must be considered: (1) different definitions of alcohol and nicotine use (current, ever users, or quitters) may provide different results; (2) lifetime regular alcohol use (persistence of drug use) may be the best target according to what we know from addiction genetics; and (3) any epidemiological association that is not stable over time or not replicated in various countries is not likely to be explained by genetics. We explored the nicotine-alcohol association in the general population of two Western countries, the US and Spain (Basque country area), over a short period of time, 1992–1996 (de Leon et al. 2007b). Some of the observed associations were stable across the two general populations and subsamples determined by gender and race, but others were not. Table 5 describes the strength and relevance of the association between ever smoking and lifetime alcohol use by providing adjusted ORs and PARs.

In our study of two countries (de Leon et al. 2007b), the strength of the association between ever smoking and lifetime alcohol use, measured by ORs, was significantly higher in the US general population than in the Basque region of Spain (Table 5). Also, there were higher PARs for the US than for the Basque country (about 80–90% vs. about 60%, respectively; Table 5). Thus, in both countries tobacco smoking and alcohol use were strongly associated with each other, but the association was significantly stronger in the US. This comparison provides an idea of the complexity of trying to explore the association of ever smoking and lifetime alcohol use in the general population. We believe that this association may be strongly influenced by cultural differences and that alcohol use in the general population may be influenced by non-biological factors, too. In the Basque country, weekly drinking is a socially approved behavior. Therefore, in 1992 and 1996, alcohol drinking was much more frequent in the Basque region of Spain than in the US (45–47 vs. 22–24%, respectively). Consequently, since many people drink socially in the Basque country, those with a vulnerability to alcohol use disorders are a minority and social drinkers are a majority. In the US, where social drinking is less acceptable and there was more social pressure for smoking cessation, the strong relation between ever smoking and ever drinking was probably influenced by a higher percentage of people with higher biological vulnerability and more risk of becoming addicted (de Leon et al. 2007b). Therefore, in an interpretation that is consistent with the results from twin studies, the association between nicotine and alcohol use is substantially affected by cultural factors that are important in influencing alcohol use.

Association between nicotine and alcohol addictions in clinical samples

Smoking is very frequent in clinical samples of alcohol addicts but there are no meta-analyses or comprehensive reviews of the studies. This is not surprising since researchers investigating an addiction tend to ignore addictions other than the one in their field of research (Kozlowski et al. 1990). Published current smoking prevalences are >80% for alcohol addicts (Hughes 1996) and >75% for alcohol addicts in early recovery (Kalman et al. 2005).

Association between schizophrenia and alcohol addiction

Schizophrenia review articles have provided ranges of alcohol addiction prevalence of 25–45% (Buckley 2006) or 21–86% (Volkow 2009). More recently, Koskinen et al. (2009) completed a meta-analysis of studies from mainly Western countries that indicated that approximately one-fifth of schizophrenia patients had a diagnosis of lifetime alcohol addiction but there was a very high variability in study prevalences, a decreasing trend over years and a lack of control for smoking effects. A more recent Swedish schizophrenia study with a large cohort indicated a prevalence of alcohol addiction of 8%, higher than in the Swedish general population (Jones et al. 2011) but lower than in US schizophrenia studies.

Association between nicotine and drug addictions

Drugs other than alcohol and nicotine are frequently used and abused all over the world. Cannabis is used all across the world. Opiate use is concentrated in Asia and Europe, and cocaine use is concentrated in the Americas and to a lesser extent in Europe (Anderson 2006; Degenhardt et al. 2008). According to the NESARC study, the US prevalence of any reported drug addiction during the 12 months prior to the study was 2.0% (2.8% in men and 1.2% in women) (Grant et al. 2004).

The following issues are reviewed in the following subsections: (1) the genetics of nicotine and drug addictions; (2) the association between tobacco and drug use in the general population; (3) the association between nicotine and drug addictions in clinical samples; and (4) the association between schizophrenia and drug addiction.

Genetics of tobacco and drug use or addiction

Tobacco and other drug use and their addictions are associated in Western countries. Most of the studies focused on the association between drugs and tobacco tend to include all drugs together rather than separate specific drugs. Twin studies support the following: (1) initiation and early patterns of drug use are strongly influenced by social and familial environmental factors whereas later levels of use are strongly influenced by genetic factors (Kendler et al. 2008), (2) there are common genetic influences shared by all drugs (Xian et al. 2008; Vanyukov et al. 2009), and (3) there are unique environmental and genetic influences for specific drugs (Kendler et al. 2007; Xian et al. 2008). Kendler et al. (2005) commented that measures of availability may be important but difficult to establish for illegal drugs; thus, using drug use as a measure of availability may be practical but far from ideal. Agrawal et al. (2010) focused on the association between nicotine and cannabis addictions in a twin study, indicating that complex bidirectional models are possible (e.g., cannabis influences tobacco, and tobacco influences cannabis addiction).

As drug addictions are less frequent than nicotine and alcohol addictions, there have not been large-scale GWAS investigating drug addiction; the genetic approach has mainly focused on candidate gene studies. However, there have been few replications (Bierut 2011).

Association between tobacco smoking and drug use in the general population