Abstract

Background

Nicotine withdrawal symptoms are related to smoking cessation. A Rasch model has been used to develop a unidimensional sensitivity score representing multiple correlated measures of nicotine withdrawal. A previous autosome-wide screen identified a nonparametric linkage (NPL) log-likelihood ratio (LOD) score of 2.7 on chromosome 6q26 for the sum of nine withdrawal symptoms.

Methods

The objectives of these analyses are: a) to assess the influence of nicotine withdrawal sensitivity on relapse, b) conduct autosome-wide NPL analysis of nicotine withdrawal sensitivity among 158 pedigrees with 432 individuals with microsatellite genotypes and nicotine withdrawal scores, and c) explore family-based association of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) at the mu opioid receptor (MOR) candidate gene (OPRM1) to nicotine withdrawal sensitivity in 172 nuclear pedigrees with 419 individuals with both SNP genotypes and nicotine withdrawal scores.

Results

An increased risk for relapse was associated with nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score (odds ratio, OR=1.25, 95% confidence interval, 95%CI=1.10,1.42). A maximal NPL LOD score of 3.15, suggestive of significant linkage, was identified at chr6q26 for nicotine withdrawal sensitivity. Evaluation of 18 OPRM1 SNPs via the family based association test (FBAT) with the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score identified eight tagging SNPs with global P-values<0.05 and false discovery rate Q-values<0.06.

Conclusion

An increased risk of relapse, suggestive linkage at chr6q26, and nominally significant association with multiple OPRM1 SNPs was found with Rasch modeled nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score in a multiplex smoking pedigree sample. Future studies should attempt to replicate these findings and investigate the relationship between nicotine withdrawal symptoms and variation at OPRM1.

INTRODUCTION

Smoking was reported to underlie 4.8 million premature deaths in the world in 2000 and were evenly split between developing countries and industrialized countries (1–2). Most smokers who attempt to quit smoking have difficulty remaining tobacco-free due to the large number of nicotine withdrawal symptoms and the severity of these symptoms has been reported to be related to smoking cessation success (3).

Nicotine withdrawal symptoms have been characterized using more than two dozen research based methods (4–5). Withdrawal symptoms characterize smokers’ levels of irritability, restlessness, insomnia, depression, concentration, appetite, and cravings and urges for tobacco over many differing time periods ranging from weeks (6) to years (7–8). Nicotine withdrawal symptoms are highly correlated and methods have been used to summarize these symptoms, including the use of latent class analyses (9–10) and Rasch models (11). A unidimensional Rasch model of nicotine withdrawal sensitivity was constructed in a sample of 1,644 smokers reporting quitting for 3 months or more at least once (11). The Rasch modeled nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score enables analysis of multiple highly correlated nicotine withdrawal symptoms in a single analysis, and is significantly associated with an increased hazard ratio with respect to the duration of these attempts, as well as to smoking intensity, and a shorter time to first cigarette in the morning (11). Rasch models have also been previously used to evaluate the unidimensionality and associations of established measures of nicotine dependence (12), and of additional measures of nicotine dependence and their relationship to items within established measures of nicotine dependence (13).

This study utilizes a Rasch modeled nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score constructed from eight quit attempt symptoms obtained from participants in a longitudinal family sample called the SMOking in FAMilies study (SMOFAM sample) (14). SMOFAM is a community based sample of pedigrees, ascertained via an adolescent proband, and longitudinally followed via annual assessments over a period of nearly two decades to study the social and behavioral risk factors for tobacco use (15). Multiplex ever smoking (≥ 100 cigarettes smoked) pedigrees, drawn from those pedigrees where the proband had completed at least seven of the first ten assessments on tobacco use and elected to provide a blood sample for DNA analysis, were recruited for an integrated study of the genetics of smoking behavior and nicotine metabolism. These pedigrees were administered a family history of tobacco use questionnaire that included cigarette smoking quit history and withdrawal symptoms (16). Specifically respondents were asked: ‘During the first few days after you quit smoking cigarettes (the first or the most recent time) for at least 3 months, did you feel or experience any of the following?’. Items, presented were: irritable or angry, restless, increased appetite, depressed mood, difficulty sleeping, craving to use tobacco, anxious, and difficulty concentrating. Previously (14), a withdrawal severity scale that included these eight symptoms of withdrawal, as well as a ninth symptom “decreased heart rate”, was used in a linkage analysis. The Rasch modeled nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score did not include the ninth withdrawal symptom due to reduced fit in a number of correlation, factor and item response analyses (data not shown). These analyses use the Rasch modeled nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score for analyses with relapse, defined as re-engaging in smoking after quitting for one week or longer, and for autosome-wide linkage analysis and association analysis with common variation at a candidate gene of importance for smoking behavior, the mu opioid receptor (MOR) gene (OPRM1).

The SMOFAM Study previously conducted model free linkage analysis with several nicotine dependence and tobacco use phenotypes (14). Swan et al found a maximal LOD score (MLS) of 2.7 on chromosome 6 for the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) and a MLS score of 2.7 on chromosome 6 for withdrawal severity (the summation of nine withdrawal symptom scores, rated on a 4-point Likert scale; 0, not at all to 3, severe, with range 0 to 27), with the FTND MLS found distal to the withdrawal severity MLS. The support interval for the FTND MLS covered a broad area of 34 centiMorgans (cM) (17), from 156–190 cM, while the support interval for withdrawal severity covered an overlapping but smaller region of 25 cM, from 148–173 cM. The more proximal support interval includes the mu opioid receptor (MOR) gene (OPRM1) locus.

The MOR binds endogenous beta-endorphin, the release of which increases upon nicotine administration; activation of the MOR results in dopamine release within the nucleus accumbens, possibly through inhibition of GABAergic inhibition of dopaminergic neurotransmission (18). The potential involvement of the OPRM1 gene in smoking related phenotypes is supported by multiple analyses. A novel linkage analysis of existing data and bioinformatic analyses of extant literature reported positive correlations between linkage analyses of nicotine dependence, microarray/candidate gene studies, and biological pathway analyses (19). Analysis of seven OPRM1 SNPs identified several haplotypes significantly associated with smoking initiation and two haplotypes marginally associated with nicotine dependence (20). The OPRM1 non-synonymous (Asn40Asp) SNP (rs1799971) has been significantly associated with long-term smoking cessation in interaction with gender (18).

Herein we present findings regarding an association between the Rasch modeled nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score and smoking relapse. We also present the results of an autosome-wide linkage analysis, and a family based association analysis at the OPRM1 gene to the Rasch modeled nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score using microsatellite genotypes and OPRM1 SNPs available in the SMOFAM dataset.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cohort

Included in these analyses are subjects 11 to 15 years of age, their parents and siblings from the longitudinal SMOFAM study of environmental and genetic determinants of tobacco use (15–16). Characterization of phenotypes for tobacco use, including the acquisition and maintenance of smoking, as well as potential psychosocial and environmental predictors of substance use, were collected for this cohort. After identification and recruitment of probands and family members, a detailed intake assessment was performed that included sociodemographics and a complete cigarette smoking history. Genomic DNA was extracted from venous whole blood using a standard salt-based precipitation method (21).

Phenotypes

The phenotypic outcome measure used in the logistic regression analyses is relapse, which is defined as re-engaging in smoking after quitting for one week or longer. Relapse was used as the dependent variable while the Rasch modeled nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score was the independent variable in the logistic regression analysis. The phenotypic outcome measure used in the linkage and association analyses is the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score formulated using the smoking withdrawal responses from the Smoking History Questionnaire with details of the development of this measure described in (22). The unidimensional nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score summarizes the eight quit attempt symptoms. The nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score was examined for autosome-wide linkage and for candidate gene association with SNPs of the OPRM1 gene.

Linkage

Genotypes were determined for 739 dinucleotide microsatellite markers (14) on 158 pedigrees containing 611 individuals with an average of 3.87 individuals genotyped per family (these figures apply to the entire SMOFAM dataset). A sex-averaged genetic map developed by Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA), using 763 autosomal map positions generated from CEPH genotype data, was used in the linkage analysis and all cM references herein are with respect to this map1. All available genotypes were analyzed for each family using PREST to validate the structure of pedigrees (23). Pedcheck was used to detect non-Mendelian inheritance patterns (24). The probability that each genotype was correct was assessed in the context of all other available genotypes using the error-checking algorithm implemented in Merlin (25). Less than 0.5% of all genotypes were excluded after these quality controls were applied. Autosomal multipoint non-parametric linkage analysis (NPL) was performed on the final genotype data in Merlin with the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score as the phenotype (25–26). Merlin (25) was used to identify the number of times a LOD score as significant as the MLS observed in this linkage analysis was observed in 1,000 simulated genome scans.

SNP Selection, Genotyping and Linkage Disequilibrium Analyses

Existing OPRM1 SNP data were available from a candidate gene panel designed to interrogate nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, dopaminergic and neuropeptide candidate genes for studies of nicotine addiction and treatment related phenotypes (27–30). As described in Conti et al., genotyping of DNA samples used the GoldenGate™ assay (Illumina, San Diego, CA), with quality control procedures that included automated sample handling protocols and the inclusion of replicate DNA samples to aid in identifying genotyping errors (29). The online databases dbSNP (31) and Genewindow (32) were used to assign chromosome position and genomic annotation for OPRM1 SNPs. The program HAPLOVIEW (33) was employed to examine the extent of linkage disequilibrium (LD) between pairs of OPRM1 SNPs as well as to determine the haplotype block structure within the SMOFAM sample. Blocks were defined using the criteria proposed by Gabriel et al (34). The tagging SNP selection program Tagger (35) was used to select a subset of 21 SNPs representing the genetic information contained in the 46 OPRM1 SNPs genotyped in the SMOFAM sample.

Association testing

Logistic regression as implemented in Stata Version 9 (36) was used to assess the association between relapse and the Rasch modeled nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score. The Family Based Association Test (FBAT) (37) as implemented within the GeneticsBase package from Bioconductor (38) of the R programming language (39) was used to test for association between OPRM1 SNPs in the pedigrees between the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score and 18 candidate SNPs. We considered P-values <0.05 to represent nominal statistical significance.

False Discovery Rate Analysis

To assign false discovery probabilities to individual OPRM1 SNPs included in the FBAT, false discovery rate (FDR) Q-values were calculated (40). Briefly, while P-values express the probability of a single false-positive result among all tests, Q-values estimate the proportion of results declared interesting that are actually false (41). As suggested by Storey et al (42) for analyses with few numbers of P-values, the bootstrap option was utilized in preference to the smoother option in generation of the Q-values. The authors suggest that the bootstrap method provides more reliable estimates under these conditions (42). We opted to not employ a specific Q-value threshold but rather present the Q-values in relationship to P-values and biological plausibility.

RESULTS

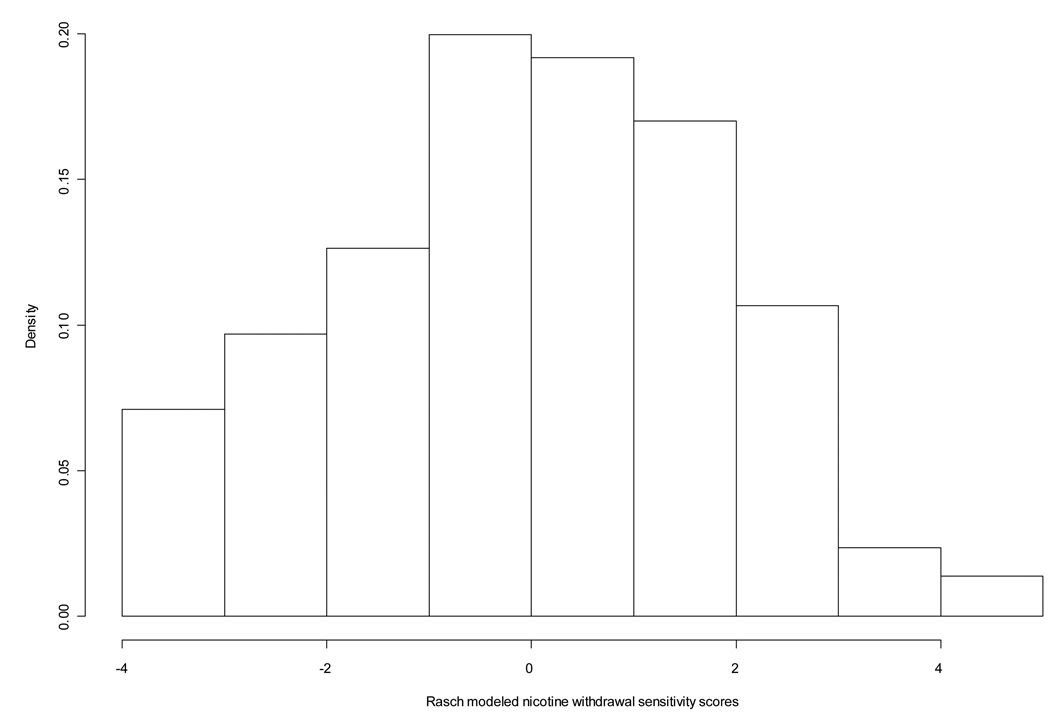

The sample for these genetic analyses consisted of 224 pedigrees (N=520 individuals) with complete nicotine withdrawal data, where 158 pedigrees had linkage scan genotype data and 172 pedigrees had OPRM1 SNP data. The sample of SMOFAM subjects with complete OPRM1 genotype and nicotine withdrawal sensitivity scores (N=419) used in these analyses was approximately equally divided by gender and by smoking status (current versus former smokers with a small proportion of experimenters) (Table 1). In these analyses 45% of subjects stated that they had relapsed due to withdrawal symptoms (data not shown). In the sample of 520 subjects, the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score distribution is approximately normal (Figure 1), and has a mean value of −0.014 with a standard deviation of 1.84. An increased risk of relapse was associated with the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score (OR=1.25, 95%CI=1.10,1.42) (data not shown). Models testing for associations between gender and the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score were null and therefore adjustments for gender were considered unnecessary in these analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects with complete genotype and Rasch modeled nicotine withdrawal score data.

| Gender | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 204 (48.7) | |

| Female | 215 (51.3) | |

| Smoker Status | N (%) | |

| Experimenter* | 9 (2.2) | |

| Current‡ | 216 (51.6) | |

| Former† | 194 (46.3) |

Experimenter smoker = smoking 100 or more cigarettes in a lifetime and not ever smoking on a daily basis.

Current smoker = ever smoking a cigarette even a puff and smoking 100 or more cigarettes in a lifetime and currently smoking one or more cigarettes on most days or currently smoking one or more cigarettes on most days and not having quit smoking cigarettes completely.

Former smoker = ever smoking a cigarette even a puff and ever smoking on a daily basis and quitting smoking cigarettes completely.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Rasch modeled nicotine withdrawal sensitivity scores in the SMOFAM sample.

The number of pedigrees with linkage scan data was 158 and the number of individuals in those pedigrees with nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score data was 432. The autosome-wide MLS for the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score linkage analysis was 3.15 at 164.5 cM on chr6q26 (Figure 2), with a multipoint P of 7×10−5 (Supplementary Table 1). A LOD score result of this magnitude was observed 37 times in 1000 simulated genome scans. The 1 and 2 LOD support intervals range from 152 to 172, and 147 to 178 cM, respectively. The average number of pedigrees and subjects with complete linkage scan genotype data and nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score data at the two markers flanking the MLS was 154 and 397, respectively. No other chromosomal regions with LOD scores > 2.0 other than chr6q26 were observed. Chromosomal regions with LOD scores > 1.0 were observed on chr1 at 112.1 cM (P=0.009), chr4 at 144.1 cM (P=0.0015), chr13 at 13.4 cM (P=0.004), and at chr15 at 74.8 cM (P=0.011), in addition to chr6q26 (see Supplementary Table 1 for a complete list of LOD Scores > 1 associated with the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score).

Figure 2.

Multipoint LOD score (y axis) for Rasch modeled nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score by chr6 cM location (x axis) in the SMOFAM sample. Vertical line at 147.9 cM indicates location of OPRM1 locus.

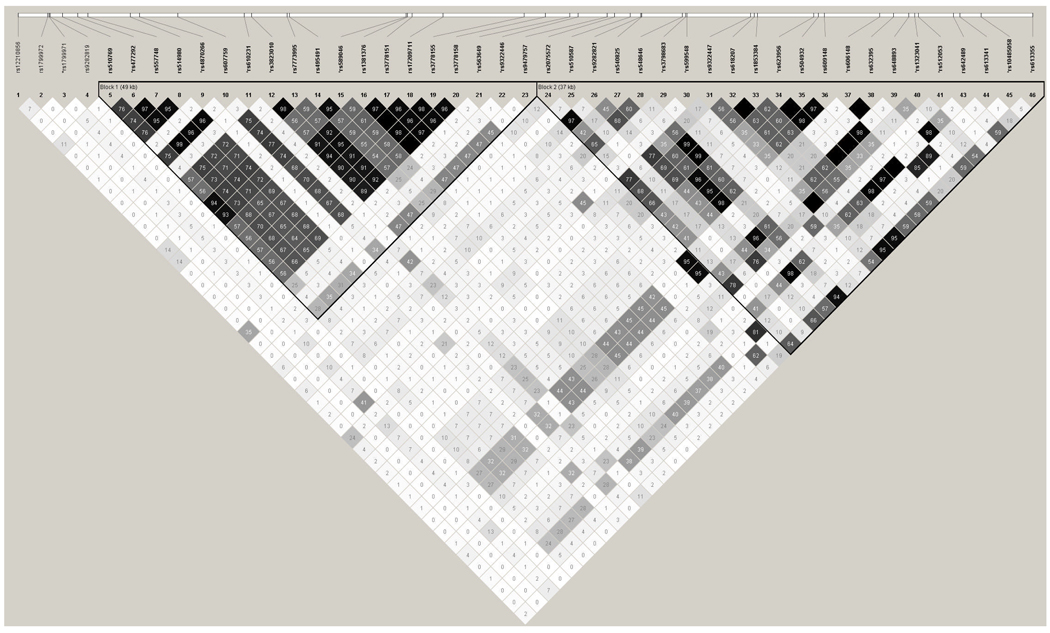

Forty-six genotyped SNPs covering the OPRM1 genetic region in the SMOFAM sample were available for analysis (Figure 3). SNPs in intervening sequence 1 (IVS1) of OPRM1 and SNPs in IVS3 through IVS5 are in significant LD in this sample, where SNPs in IVS2 appear to be in LD with SNPs in either the 5’ or 3’ LD block (Figure 3). Because there was substantial pair-wise LD between adjacent markers and to reduce redundant multiple testing, a subset of 21 SNPs that captured 85% of all SNPs in the region (MAF ≥ 0.05) at r2 > 0.8 were selected (Figure 3). Three SNPs with minor allele frequencies < 0.05 (rs12210856, rs1799972, and rs9282819) and seven subjects with genotypes inconsistent with Mendelian inheritance were removed from the dataset prior to FBAT analyses. In this FBAT analysis, there were 172 pedigrees (N=419 subjects) with complete OPRM1 SNP genotypes and nicotine withdrawal sensitivity scores. Eight of eighteen SNPs evaluated for family based association with the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score had global P-values of less than 0.05 (Table 2). All eight SNPs with P-values < 0.05 have Q-values < 0.06. Five of these eight SNPs are located in IVS1, with one each in IVS3, IVS4 and IVS5. The non-synonymous SNP rs1799971, which has been investigated in numerous studies of substance dependence, has a P-value = 0.07 and a Q-value = 0.08 in this analysis.

Figure 3.

Pairwise linkage disequilibrium between 46 genotyped OPRM1 SNPs in the SMOFAM sample. Within each cell is the pair-wise estimation of the correlation coefficient between pairs of SNPs (r2). SNPs preceded by a “*” were used in OPRM1 SNP association analyses.

Table 2.

OPRM1 SNPs and association with Rasch modeled nicotine withdrawal sensitivity

| Name | Position* | Genomic† | MAF‡ | Chisq | Global P | FDR Q |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1799971 | 154452910 | Ex1−173 | 0.13 | 3.28 | 0.0702 | 0.0821 |

| rs477292 | 154455500 | IVS1+2418 | 0.226 | 5.73 | 0.0167 | 0.0586 |

| rs4870266 | 154461111 | IVS1+8029 | 0.066 | 0.018 | 0.8937 | 0.5534 |

| rs610231 | 154470590 | IVS1+17508 | 0.113 | 2.19 | 0.1390 | 0.1463 |

| rs3823010 | 154471265 | IVS1+18183 | 0.178 | 4.14 | 0.0418 | 0.0599 |

| rs589046 | 154485251 | IVS1−17823 | 0.261 | 5.90 | 0.0152 | 0.0586 |

| rs563649 | 154500080 | IVS1−2994 | 0.085 | 0.39 | 0.5316 | 0.5082 |

| rs9322446 | 154500815 | IVS1−2259 | 0.136 | 4.79 | 0.0286 | 0.0599 |

| rs510587 | 154505541 | IVS3+711 | 0.054 | 4.00 | 0.0455 | 0.0599 |

| rs9282821 | 154506488 | IVS3−30 | 0.413 | 0.13 | 0.7173 | 0.5188 |

| rs3798683 | 154510527 | IVS4+3759 | 0.194 | 4.29 | 0.0384 | 0.0599 |

| rs599548 | 154510674 | IVS4+3906 | 0.133 | <0.01 | 0.9562 | 0.5592 |

| rs623956 | 154522138 | IVS4−9792 | 0.238 | 0.24 | 0.6276 | 0.5082 |

| rs606148 | 154528099 | IVS4−3831 | 0.099 | 4.29 | 0.0383 | 0.0599 |

| rs1323041 | 154531293 | IVS4−637 | 0.463 | 0.07 | 0.7886 | 0.5188 |

| rs512053 | 154531629 | IVS4−301 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.7679 | 0.5188 |

| rs10485058 | 154537327 | IVS5+4908 | 0.121 | 5.77 | 0.0164 | 0.0586 |

| rs613355 | 154541962 | IVS5+9543 | 0.347 | 0.24 | 0.6234 | 0.5082 |

Chromosome positions are based on NCBI Human Genome Assembly, chr6.

Genomic annotation obtained at genewindow.nci.nih.gov.

MAF is the minor allele frequency of the SNP in the SMOFAM sample.

DISCUSSION

Our analyses of a multiplex smoking pedigree sample identified an increased risk of relapse associated with nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score. We found suggestive evidence for autosome-wide linkage with nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score. We identified significant association and a nominal FDR between common sequence variants at the MOR gene locus, OPRM1, and nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score.

In a study that characterized nicotine dependence and nicotine withdrawal symptoms among adolescent smokers, seven withdrawal symptoms were more common among persons who had not successfully quit smoking than among successful quitters (43). In a Dutch sample of adolescent smokers, higher levels of nicotine craving at the beginning of the prequit week and on the target quit day decreased the odds of being abstinent during the last week of the study (3). In another Rasch model analysis of nicotine withdrawal sensitivity, increased nicotine withdrawal scores were associated with a shorter duration of quitting and with measures of nicotine dependence (11). In our analysis of nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score in a sample of multiplex smoking pedigrees (16), an increased nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score was associated with a greater likelihood of relapse.

Our linkage analyses identified a MLS of 3.15 at 164.5 cM on chr6q26 for the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score. Swan et al previously found a MLS of 2.7 at 159 cM on chr6q26 for withdrawal severity (the summation of nine withdrawal symptom scores, rated on a 4-point scale; 0, not at all to 3, severe, with range 0 to 27) in the SMOFAM sample (14). The use of the Rasch modeled nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score constructed from eight nicotine withdrawal symptoms as the phenotype in the present analysis resulted in an increase in the multipoint MLS of 0.45 units over the use of the sum of nine withdrawal symptoms as the phenotype in the previous analysis (14). This suggests that the use of the Rasch model using eight withdrawal symptoms may be a more precise measure of a nicotine withdrawal trait linked to chr6q26. The multipoint P and the empirical P suggest that a linkage analysis result of this magnitude is expected by chance approximately 5% of the time in this sample (44). Existing linkage studies using nicotine withdrawal symptoms include only the studies of Swan et al., and a linkage study in two European ancestry populations that identified a genome-wide significant linkage on chr11p15 in the region of several monamine and nicotinic acetylcholine candidate genes, as well as two other regions of interest on chromosomes 6p and 11q (45). Other linkage analyses have identified suggestive linkage evidence (44) for smoking related behaviors on chr6q. Evidence of suggestive linkage was found for a combined dependence phenotype for any drug class and / or regular tobacco usage (every day for at least 1 month), analyzed as a threshold or continuous trait (LOD=2.54 or LOD=3.3) in a linkage sample of 49 pedigrees at 157 cM on chr6q25.3 (46), using the same linkage scan panel as used in this analysis. Analysis of a combined trait of BMI, drug dependence and / or regular tobacco use in the same sample reached a MLS of 4.1 at 151 cM on chr6q25.2. A search of the Sullivan Lab Evidence Project psychiatric genetics database (47) for genome wide linkage and association findings in the 2 LOD support interval flanking our MLS annotates findings with bipolar, schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, ADHD, and autism disorders (Supplementary Table 2). Psychiatric disorders are well-known to be comorbid with cigarette smoking; it has been estimated that the majority of cigarettes smoked in the United States are smoked by individuals fulfilling standardized criteria for nicotine dependence and a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder (48).

Our candidate gene analysis suggest possible association with the OPRM1 A118G non-synonymous (N40D) SNP rs1799971 and the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score (P = 0.07, Q = 0.08). This SNP has been associated with functional differences in physiological (49) or therapeutic (50–51) responses to opioids in vivo and in vitro (52), although there are negative studies (53–54). In addition to increased affinity for endorphin, an endogenous MOR ligand, and increased post-synaptic potassium current (52), differential allelic expression of the gene has been another mechanism hypothesized to account for potential functional differences between alleles (55). A meta analysis of rs1799971 allelic association utilizing 28 samples of individuals fulfilling DSM-III, DSM-IV or ICD-10 critieria for alcohol, opioid, methamphetamine or mixed substance dependence reported no association (56). Because no exclusions for smoking behaviors were made in case or control samples, this particular meta analysis may not be informative for substance dependence that involves nicotine dependence alone or in combination with other substance dependence. rs1799971 is not significantly associated with nicotine dependence in some population based (20, 57) or treatment seeking smoker (28) samples. With respect to smoking related behaviors, the OPRM1 SNP rs1799971 minor allele (A) homozygote has been associated with an increased reinforcing value of nicotine in women and a tendency to prefer nicotine versus denicotinized cigarettes in both sexes (2), and with endorsing cigarette liking after negative mood induction (58). In a clinical trial studying the effects of transdermal nicotine and nicotine nasal spray, smokers with one or more copies of the major allele (G) were more likely to be abstinent and experienced less mood disturbance and short-term weight gain compared to smokers with two copies of the minor allele (59). The study also found that the genotype effect on treatment outcome was most pronounced in smokers receiving transdermal nicotine (59). Note however that the minor allele homozygote has been associated with increased long-term smoking cessation with the use of transdermal nicotine patch versus placebo (18).

In our analysis, there is slightly more evidence for association of OPRM1 SNPs to the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score in OPRM1 introns, where four SNPs are nominally significantly associated with the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score in each of the two linkage OPRM1 linkage blocks commonly observed in European ancestry populations (60). Evidence from other studies also suggests that there are potentially two regions of linkage disequilibrium at OPRM1 that may be associated with smoking related phenotypes. In a study investigating associations between 9 OPRM1 SNPs and nicotine dependence in interaction with gender, rs510769 (IVS1+1050) was significantly associated with dichotomized nicotine dependence (P=0.000416) in a sample of 1,929 unrelated ever-smokers with FTND scores of 0, or 4 or more (57). In a study investigating associations between 11 OPRM1 SNPs and nicotine dependence, rs10485057 (IVS3+538) was significantly associated (P=0.0297) with dichotomized nicotine dependence in a sample of 430 unrelated ever-smokers with Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire (61) scores of 0–2 or 7–11 (20). In addition to studies of OPRM1 variation association with nicotine withdrawal symptoms, dopamine receptor locus sequence variation has been evaluated for association with measures of nicotine withdrawal (62–63): one of two SNPs at the D2 dopamine receptor locus (DRD2) was observed to be significantly associated with acute nicotine withdrawal in interaction with time in a clinical sample of 116 smokers quitting smoking (62); and a trend towards significant association of the DRD4 Exon 3 variable number of tandem repeat polymorphism with the question “Did you feel a strong desire or craving for a cigarette?” was observed in a national probability sample of 204 current and former smokers (63).

Limitations in our analyses include those related to phenotype, linkage and association analyses. The original smoking withdrawal data was collected using a paper-based questionnaire to catalogue respondents’ withdrawal symptoms; respondents may have had trouble recalling their symptoms, and therefore these data may suffer from recall bias. Responses to nicotine withdrawal symptoms were characterized using a 0 to 3 Likert scale and therefore measurement error may exist. It is possible that false positive linkage or association results arose in these analyses, though we assessed the empirical significance of linkage and the likelihood of false positive associations to facilitate the interpretation of significance.

The selection of the OPRM1 gene for study is a limitation as there are other candidate genes located at chr6q25.2-q27 that may also contribute to the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score phenotype. While the map location of OPRM1 is within the proximal region of the 2 lod support interval, OPRM1 is only one of several candidate genes potentially influencing the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score trait located in the interval. Other candidate genes for future investigation in the 2 LOD support interval include the SLC22A1, SLC22A2 and SLC22A3 genes coding for the organic cation transporters that are responsible for cellular uptake of endogenous neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine and monamines, as well as xenobiotics.

Our FBAT analyses focused on a subset of common tagging SNPs at the OPRM1 gene and therefore it is possible that we did not include OPRM1 SNPs that may contribute to the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score phenotype. In our study we employed the use of tagging SNPs and eliminated non-informative SNPs from analysis in order to reduce the likelihood of false associations due to multiple testing. Further examination of OPRM1 variation through use of haplotype analyses, and through analyses of less common and rare variants, in relation to the nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score should be pursued in SMOFAM and additional samples.

While our study presents preliminary data with suggestive (P-values <0.05 and Q-values <0.06) evidence for eight of the eighteen SNPs tested for association with nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score, replication of our results in an independent sample is essential (64). These findings may stimulate future research on the role of variation, linkage disequilibrium, and population differences in genetic architecture at OPRM1 on nicotine withdrawal sensitivity score.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the participants in the SMOFAM study. We acknowledge Judy Andrews, Kirk Wilhemsen, Denise Nishita, Paul Thomas, David Conti, and David Van Den Bergh for their role in pedigree collection and phenotyping, linkage scan genotyping, biospecimen management and preparation, candidate gene selection, candidate gene SNP selection, and candidate gene genotyping.

Supported By: U01DA02830, R01 DA03706 and 7PT2000-2004 from the University of California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program

Footnotes

References

- 1.Ezzati M, Lopez AD. Regional, disease specific patterns of smoking-attributable mortality in 2000. Tob Control. 2004;13:388–395. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.005215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray R, Jepson C, Patterson F, et al. Association of OPRM1 A118G variant with the relative reinforcing value of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;188:355–363. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Zundert RM, Boogerd EA, Vermulst AA, Engels RC. Nicotine withdrawal symptoms following a quit attempt: an ecological momentary assessment study among adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:722–729. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiffman S, Waters A, Hickcox M. The nicotine dependence syndrome scale: a multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:327–348. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West R, Ussher M, Evans M, Rashid M. Assessing DSM-IV nicotine withdrawal symptoms: a comparison and evaluation of five different scales. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:619–627. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0216-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiffman S, Patten C, Gwaltney C, et al. Natural history of nicotine withdrawal. Addiction. 2006;101:1822–1832. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes JR. Effects of abstinence from tobacco: valid symptoms and time course. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:315–327. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes JR. Measurement of the effects of abstinence from tobacco: a qualitative review. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:127–137. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xian H, Scherrer JF, Madden PA, et al. Latent class typology of nicotine withdrawal: genetic contributions and association with failed smoking cessation and psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35:409–419. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Dinwiddie SH, et al. Nicotine withdrawal in women. Addiction. 1997;92:889–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Javitz HS, Brigham J, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Krasnow RE, Swan GE. Association of tobacco dependence and quit attempt duration with Rasch-modeled withdrawal sensitivity using retrospective measures. Addiction. 2009;104:1027–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strong DR, Kahler CW, Ramsey SE, Brown RA. Finding order in the DSM-IV nicotine dependence syndrome: a Rasch analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;72:151–162. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breteler MH, Hilberink SR, Zeeman G, Lammers SM. Compulsive smoking: the development of a Rasch homogeneous scale of nicotine dependence. Addict Behav. 2004;29:199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swan GE, Hops H, Wilhelmsen KC, et al. A genome-wide screen for nicotine dependence susceptibility loci. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141B:354–360. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hops H, Andrews JA, Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Tildesley E. Adolescent drug use development: A social interacational and contextual perspective. In: Sameroff AJ, Lewis M, editors. Hand book of developmental psychopathology. 2nd ed. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2000. pp. 589–605. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swan GE, Hudmon KS, Jack LM, et al. Environmental and genetic determinants of tobacco use: methodology for a multidisciplinary, longitudinal family-based investigation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:994–1005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bond T, Fox C. Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munafo MR, Elliot KM, Murphy MF, Walton RT, Johnstone EC. Association of the mu-opioid receptor gene with smoking cessation. Pharmacogenomics J. 2007;7:353–361. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan PF, Neale BM, van den Oord E, et al. Candidate genes for nicotine dependence via linkage, epistasis, and bioinformatics. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;126B:23–36. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Kendler KS, Chen X. The mu-opioid receptor gene and smoking initiation and nicotine dependence. Behav Brain Funct. 2006;2:28. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-2-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Javitz HS, Brigham J, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Krasnow RE, Swan GE. Association of tobacco dependence and quit attempt duration with Rasch-modeled withdrawal sensitivity using retrospective measures. Addiction. 2009;104:1027–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun L, Wilder K, McPeek MS. Enhanced pedigree error detection. Hum Hered. 2002;54:99–110. doi: 10.1159/000067666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Connell JR, Weeks DE. PedCheck: a program for identification of genotype incompatibilities in linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:259–266. doi: 10.1086/301904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cookson WO, Cardon LR. Merlin--rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat Genet. 2002;30:97–101. doi: 10.1038/ng786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kong A, Cox NJ. Allele-sharing models: LOD scores and accurate linkage tests. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:1179–1188. doi: 10.1086/301592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benowitz NL. Neurobiology of nicotine addiction: implications for smoking cessation treatment. Am J Med. 2008;121:S3–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergen AW, Conti DV, Van Den Berg D, et al. Dopamine genes and nicotine dependence in treatment-seeking and community smokers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2252–2264. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conti DV, Lee W, Li D, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor beta2 subunit gene implicated in a systems-based candidate gene study of smoking cessation. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2834–2848. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas PD, Mi H, Swan GE, et al. A systems biology network model for genetic association studies of nicotine addiction and treatment. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009;19:538–551. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32832e2ced. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sherry ST, Ward M, Sirotkin K. dbSNP-database for single nucleotide polymorphisms and other classes of minor genetic variation. Genome Res. 1999;9:677–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staats B, Qi L, Beerman M, et al. Gene window: an interactive tool for visualization of genomic variation. Nat Genet. 2005;37:109–110. doi: 10.1038/ng0205-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296:2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Bakker PI, Yelensky R, Pe'er I, Gabriel SB, Daly MJ, Altshuler D. Efficiency and power in genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1217–1223. doi: 10.1038/ng1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stata Statistical Software. Release 10 ed. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rabinowitz D, Laird N. A unified approach to adjusting association tests for population admixture with arbitrary pedigree structure and arbitrary missing marker information. Hum Hered. 2000;50:211–223. doi: 10.1159/000022918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Team RDC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genome wide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Storey JD. A direct approach to false discovery rates. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 2002;64:479–498. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Storey JD, Taylor JE, Siegmund D. Strong control, conservative point estimation and simultaneous conservative consistency of false discovery rates: a unified approach. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 2004;66:187–205. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prokhorov AV, Hudmon KS, de Moor CA, Kelder SH, Conroy JL, Ordway N. Nicotine dependence, withdrawal symptoms, and adolescents' readiness to quit smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:151–155. doi: 10.1080/14622200110043068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lander E, Kruglyak L. Genetic dissection of complex traits: guidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat Genet. 1995;11:241–247. doi: 10.1038/ng1195-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pergadia ML, Agrawal A, Loukola A, et al. Genetic linkage findings for DSM-IV nicotine withdrawal in two populations. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B:950–959. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ehlers CL, Wilhelmsen KC. Genomic screen for substance dependence and body mass index in southwest California Indians. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:184–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Konneker T, Barnes T, Furberg H, Losh M, Bulik CM, Sullivan PF. A searchable database of genetic evidence for psychiatric disorders. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:671–675. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, Stinson FS, Dawson DA. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1107–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wand GS, McCaul M, Yang X, et al. The mu-opioid receptor gene polymorphism(A118G) alters HPA axis activation induced by opioid receptor blockade. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:106–114. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oslin DW, Berrettini W, Kranzler HR, et al. A functional polymorphism of the mu-opioid receptor gene is associated with naltrexone response in alcohol-dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1546–1552. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anton RF, Oroszi G, O'Malley S, et al. An evaluation of mu-opioid receptor (OPRM1) as a predictor of naltrexone response in the treatment of alcohol dependence: results from the Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavioral Interventions for Alcohol Dependence (COMBINE) study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:135–144. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bond C, LaForge KS, Tian M, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphism in the human mu opioid receptor gene alters beta-endorphin binding and activity: possible implications for opiate addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9608–9613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gelernter J, Gueorguieva R, Kranzler HR, et al. Opioid receptor gene (OPRM1, OPRK1,and OPRD1) variants and response to naltrexone treatment for alcohol dependence: results from the VA Cooperative Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:555–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beyer A, Koch T, Schroder H, Schulz S, Hollt V. Effect of the A118G polymorphism on binding affinity, potency and agonist-mediated endocytosis, desensitization, and resensitization of the human mu-opioid receptor. J Neurochem. 2004;89:553–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Y, Wang D, Johnson AD, Papp AC, Sadee W. Allelic expression imbalance of human mu opioid receptor (OPRM1) caused by variant A118G. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32618–32624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arias A, Feinn R, Kranzler HR. Association of an Asn40Asp (A118G) polymorphism in the mu-opioid receptor gene with substance dependence: a meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saccone SF, Hinrichs AL, Saccone NL, et al. Cholinergic nicotinic receptor genes implicated in a nicotine dependence association study targeting 348 candidate genes with 3713 SNPs. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:36–49. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perkins KA, Lerman C, Grottenthaler A, et al. Dopamine and opioid gene variants are associated with increased smoking reward and reinforcement owing to negative mood. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:641–649. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32830c367c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lerman C, Wileyto EP, Patterson F, et al. The functional mu opioid receptor (OPRM1) Asn40Asp variant predicts short-term response to nicotine replacement therapy in a clinical trial. Pharmacogenomics J. 2004;4:184–192. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fagerstrom KO. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav. 1978;3:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robinson JD, Lam CY, Minnix JA, et al. The DRD2 TaqI-B polymorphism and its relationship to smoking abstinence and withdrawal symptoms. Pharmacogenomics J. 2007;7:266–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vandenbergh DJ, O'Connor RJ, Grant MD, et al. Dopamine receptor genes (DRD2, DRD3 and DRD4) and gene-gene interactions associated with smoking-related behaviors. Addict Biol. 2007;12:106–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chanock SJ, Manolio T, Boehnke M, et al. Replicating genotype-phenotype associations. Nature. 2007;447:655–660. doi: 10.1038/447655a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.