Abstract

Deep brain stimulation of the ventral striatum is an effective treatment for a variety of treatment refractory psychiatric disorders yet the mechanism of action remains elusive. We examined how five days of stimulation affected rhythmic brain activity in freely moving rats in terms of oscillatory power within, and coherence between, selected limbic regions bilaterally. Custom made bipolar stimulating/recording electrodes were implanted, bilaterally, in the nucleus accumbens core. Local field potential (LFP) recording electrodes were implanted, bilaterally in the prelimbic and orbitofrontal cortices and mediodorsal thalamic nucleus. Stimulation was delivered bilaterally with 100μs duration constant current pulses at a frequency of 130Hz delivered at an amplitude of 100μA using a custom-made stimulation device. Synchronized video and LFP data were collected from animals in their home cages before, during and after stimulation. Signals were processed to remove movement and stimulation artifacts, and analyzed to determine changes in spectral power within, and coherence between regions. Five days stimulation of the nucleus accumbens core yielded temporally dynamic modulation of LFP power in multiple bandwidths across multiple brain regions. Coherence was seen to decrease in the alpha band between the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus and core of the nucleus accumbens. Coherence between each core of the nucleus accumbens bilaterally showed rich temporal dynamics throughout the five day stimulation period. Stimulation cessation revealed significant “rebound” effects in both power and coherence in multiple brain regions. Overall, the initial changes in power observed with short-term stimulation are replaced by altered coherence, which may reflect the functional action of DBS.

Keywords: deep brain stimulation, local field potential, ventral striatum, obsessive-compulsive disorder, nucleus accumbens

Introduction

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the ventral striatum is an effective treatment for patients with treatment refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) [1]. Despite this the mechanisms by which DBS effects its therapeutic benefit remains poorly understood. The original “functional lesion” hypothesis, drawn largely from the clinically analogous outcomes in ablative surgical procedures, is insufficient to account for the broad spectrum of effects reported in both the stimulation target [2-6], the regions to which it projects [2, 7-9] and the regions from which it receives projections [10-12]. It is clear that the mechanism of action is necessarily complex, plausibly including local effects on principal neurons, interneurons and glia [13], long term plastic changes, antidromic and orthodromic activation, effects on fibers of passage, long term potentiation and even changes in neurogenesis.

Models of OCD propose dysfunction in fronto-cortical-basal-ganglial circuits including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, basal ganglia and thalamus [14]. Hyperactivity in fronto-cortical-basal-ganglial circuits declines following successful treatment [15] leading to the hypothesis that dysfunctional orbitofrontal-basal-ganglial circuits may drive OCD symptoms [16]. Consistent with this, OCD patients improve after frontocortical-basal-ganglial circuit lesions [17, 18]. The junction of the ventral anterior capsule and ventral striatum is a key node in this network and imaging studies demonstrate that acute stimulation of this region modulates fronto-cortical-basal-ganglial circuits in patients [19]. This original clinical target has evolved, becoming more posterior and stimulation is now performed in the region at which there is a confluence of cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical fibers [1]; the core of nucleus accumbens in the rat is the site that most closely approximates this site in humans.

The therapeutic effects of stimulation of the ventral striatum also take considerable time to appear [20]. Despite this many preclinical studies seek to determine the “mechanism of action” by considering acute DBS in periods ranging from minutes to hours but typically merely for the period of measurement [21-25]. Oscillatory changes in rats take significant time to appear [10, 12]. Therefore, in the current work, these findings are extended to examine the time course over which changes continue to accumulate through analysis of spontaneous local field potentials, which are thought to better reflect ongoing activity than do recordings of spiking activity within and between the prelimbic cortex, the orbitofrontal cortex, the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus and the core of the nucleus accumbens over the course of five days of continuous high frequency stimulation.

Materials & Methods

All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines out-lined in the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh.

Electrodes

LFP electrodes were fabricated from 200μm, polyimide insulated, stainless steel wire (Plastics 1). Dual recording/stimulating bipolar-concentric electrodes were fabricated by feeding 125μm, polymide insulated, stainless steel wire through 26G stainless steel tubing. A third 125μm LFP recording electrode was affixed to the outside of the tubing to allow simultaneous stimulation and recording from the same site. The stainless steel tubing was insulated with miniature heatshrink tubing (Plastics 1).

Animals and surgery

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 380-519g (mean = 461g, n = 9 per group/18 total) were anesthetized with isoflurane (induction: 5%, maintenance: 2% in oxygen) and mounted in a stereotaxic frame. Carprofen (Rimaydyl™) was administered for analgesia (5mg/kg s.c.). Body temperature was maintained with a small heating pad (Fintronics Inc.). The scalp was incised, the skull exposed and burr holes drilled. LFP electrodes were implanted bilaterally into the prelimbic cortex (RC1: +3.4, ML: ±0.7mm, DV: −4.0mm), orbitofrontal cortex (RC: +3.2, ML: ±3.4mm, DV: −5.0mm) and mediodorsal thalamic nucleus (RC: −3.3, ML: ±0.7mm, DV: −5.5mm). Prelimbic and thalamic electrodes were implanted at 10° to the perpendicular. Dual recording/stimulating electrodes were implanted, bilaterally, in the core of the nucleus accumbens (RC: +1.2, ML: ±2.0mm, DV: −7.5mm). A ground screw was affixed at lambda and 6 additional stainless steel screws fixed in the skull. All electrodes and connectors (E363, Plastics 1) were secured with dental cement and the incision sutured tightly around the implant. Animals were housed singly following surgery, given free access to rat chow softened with children’s Tylenol for the first 2 days and allowed to recover for a week before beginning recordings.

Recording

For LFP acquisition animals were tethered to the recording system via a 12 channel cable and commutator (Plastics 1). All recordings were made against a ground screw affixed above the cerebellum at lambda. LFPs were amplified (gain = 10k), AC coupled at 1Hz, low pass filtered at 5kHz (A-M Systems model 1700) and sampled at 10kHz (to facilitate stimulation artifact removal). Time-synchronized video was also recorded (AD Instruments Powerlab). Animals exhibited spontaneous behaviours including, ambulation, grooming, rearing and remaining stationary. Due to the large movement artifacts recorded during periods of motion, stationary periods were selected for further analysis. Given these periods were brief and interspersed amongst periods of motion it was assumed that the animals were in a state of resting wakefulness rather than simply being asleep. Animals were habituated to the experimental rig (jackets, devices and connection to the recording apparatus) over 3 days. Recordings were made in their home cages starting 15 minutes after the experimenter had left the room and lasting 10 minutes. LFPs were collected for 3 days with DBS OFF. On day 4 DBS was turned on in half the animals (STIM group). Acute recordings were made immediately after turning devices ON and again at 6 hours later. DBS was constant for the subsequent 5 days with multi-site LFP recorded daily. DBS was then switched off in the STIM group and LFPs collected immediately following the cessation of DBS. Additional recordings were made 1 hour, 1 day and 2 days following the cessation of DBS.

Devices

Custom designed and constructed DBS devices (available soon from Digitimer) were fabricated for the continuous delivery of long-term DBS in the rat. Devices were configured to stimulate with square, monophasic, anodic, constant current 100μs pulses at a frequency of 130Hz delivered at an amplitude of 100μA. Devices were carried by the animals via rodent jackets (Harvard Apparatus) and connected to the electrodes via an external cable.

Signal processing

LFPs were processed to first identify a single continuous block of signal, 100s in duration, which was free of movement artifacts. Animals exhibited spontaneous waking behaviors throughout the recording session (ambulation, walking, rearing, etc). Periods in which the animal may have been sleeping were rejected.

These signals were then processed to remove electrical artifacts caused by stimulation using custom written algorithms based on those developed by others [26]. Briefly, the evoked potentials are averaged and subtracted from each stimulation period. The remaining artifact was removed by an offline sample and hold algorithm. The algorithm detects stimulus artifacts by thresholding the first derivative of the signal and deleting a user-defined period which encompasses this artifact. This “gap” in the signal is then filled with a linear interpolation and the signal smoothed by downsampling to 1kHz. To account for potential “processing artifacts” simulated artifacts were imposed on non-stimulated LFPs and then removed by the same algorithm. The artifact-free signals were then processed by Fourier methods (Welch’s modified periodogram method) to determine band power within regions and coherence (magnitude-squared) between regions for the whole epoch (delta (1-4Hz), theta (>4-8Hz), alpha (>8-12Hz), beta (>12Hz-30Hz) and gamma (30-58Hz)). Signal processing was performed using GNU Octave.

Electrode localization, exclusions and statistical analysis

Animals were re-anesthetized with isoflurane and electrode locations marked by driving a 200μA constant current through each electrode for 10s. Brains were then removed and fixed in 8% paraformaldehyde with added potassium ferrocyanide. Animals with incorrectly placed electrodes were excluded from the analysis. Animals in which the implant or device failed before completion of the experiment were also excluded since electrode location marking was no longer possible. Additional exclusions were made for 2 animals in the stimulated group since it was determined that the accumbens LFP was not recoverable (>30% of the raw signal was lost to amplifier saturation). These exclusions left the following final group sizes; nsham = 6, nstim = 4. Data were analyzed using a repeated measures ANOVA over 3 subdivisions of the entire data set. The first indicates the effects of initiating DBS by analyzing the time points immediately prior to DBS, at DBS ON and at 6 hours following the initiation of DBS. The second indicates the effects of ongoing DBS from 6 hours to 5 days stimulation. The final period indicates either effects sustained into the post-stimulation period or caused by cessation of DBS (simulated device failure). Data are presented as a percentage of the baseline value determined by averaging the 4 baseline measurements. Statistical tests were performed on normalized data for determining changes in power and coherence.

Signals were recorded bilaterally. In the interests of brevity the results are only presented from a single hemisphere (left) unless the results refer to coherence between the same region bilaterally. Equivalence of the effects in each hemisphere were tested by determining the 95% confidence interval for the difference between the variable of interest in each hemisphere bilaterally (unless the variable was an observation of interhemispheric coherence between the same regions bilaterally). These intervals all spanned zero indicating that there was no difference between variables recorded in either hemisphere at any time point. All analyses were performed using GNU Octave.

Results

Power

Effects of stimulation initiation

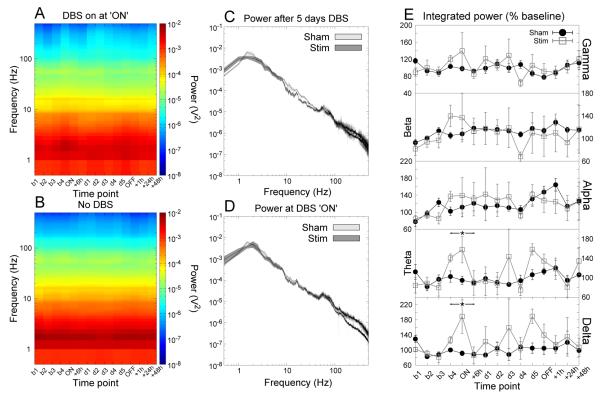

During the initial period of stimulation of the core of the nucleus accumbens there was an increase in low frequency power (delta and theta) in the prelimbic cortex at the onset of stimulation, indicated by significant effects of time and the significant group interactions (F2,14 > 3.78, p < 0.05 for both effects, Fig.1).

Figure 1.

Accumbens stimulation produced significant increases in prelimbic delta and theta LFP power that returned to baseline following 6 hours of stimulation. (A,B) Time-frequency spectrograms for stimulated and sham-stimulated animals respectively. (C,D) Grand averaged power spectra for the time points “day 5” and “ON” respectively. The shaded region indicates the SEM. (E) Power in each bandwidth as a percentage of baseline at each time point (mean ±SEM). * indicates a significant effect of stimulation.

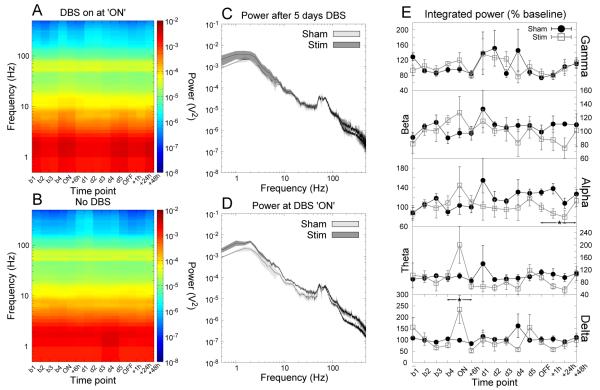

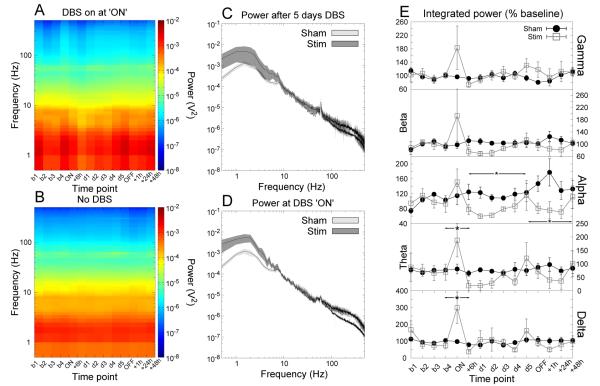

Similar changes were observed in the orbitofrontal cortex and the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus with increases in delta power in the orbitofrontal cortex (significant effects of time with a significant interaction, F2,14 > 7.25, p < 0.007 for both effects, Fig.2 and in both delta and theta bands in the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus (significant effects of time with a significant interaction, F2,14 > 4.40, p < 0.03 both effects over each bandwidth, Fig.3).

Figure 2.

Accumbens stimulation produced significant increases in orbitofrontal delta LFP power that returned to baseline following 6 hours of stimulation. There is also a significant reduction in alpha power following the cessation of stimulation. (A,B) Time-frequency spectrograms for stimulated and sham-stimulated animals respectively. (C,D) Grand averaged power spectra for the time points “day 5” and “ON” respectively. The shaded region indicates the SEM. (E) Power in each bandwidth as a percentage of baseline at each time point (mean ±SEM). * indicates a significant effect of stimulation.

Figure 3.

Accumbens stimulation produced significant increases in mediodorsal thalamic nucleus delta and theta LFP power that returned to baseline following 6 hours of stimulation. A reduction in alpha power was also seen in the MD during long-term stimulation and following the cessation of stimulation. (A,B) Time-frequency spectrograms for stimulated and sham-stimulated animals respectively. (C,D) Grand averaged power spectra for the time points “day 5” and “ON” respectively. The shaded region indicates the SEM. (E) Power in each bandwidth as a percentage of baseline at each time point (mean ±SEM). * indicates a significant effect of stimulation.

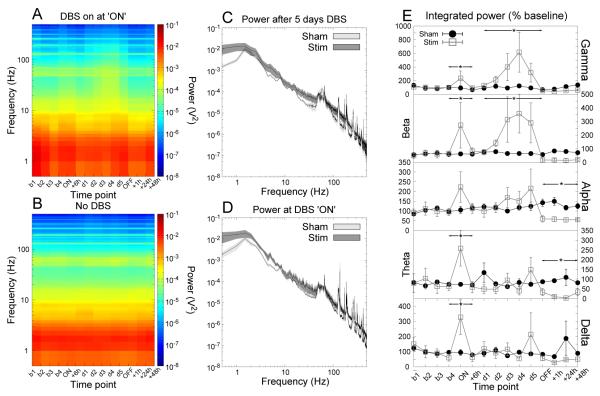

Increases in low frequency (delta and theta) power were seen in the core of the nucleus accumbens (significant effects of time with significant interactions, F2,14 > 4.01, p < 0.04 for both effects, Fig.4). Increases in high frequency (beta and gamma) power were also seen at the initiation of stimulation (significant effects of group, F1,14 > 5.81, p < 0.05 for both bandwidths, Fig.4). Despite these robust changes in power they were transient in nature and were no longer apparent following 6 hours of continuous stimulation.

Figure 4.

Accumbens stimulation produced significant increases in accumbens delta, theta, beta and gamma LFP power that returned to baseline following 6 hours of stimulation. Ongoing stimulation (>6h) yielded increases in high frequency (beta and gamma) oscillations. Cessation of stimulation yielded reductions in theta and alpha power which were no longer apparent following a further 48 hours. (A,B) Time-frequency spectrograms for stimulated and sham-stimulated animals respectively. (C,D) Grand averaged power spectra for the time points “day 5” and “ON” respectively. The shaded region indicates the SEM. (E) Power in each bandwidth as a percentage of baseline at each time point (mean ±SEM). * indicates a significant effect of stimulation.

Effects of ongoing stimulation

During the period of 5 days of continuous stimulation of the core of the nucleus accumbens there was a significant reduction in alpha power in the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus as indicated by significant effects of group (F1,14 > 6.70, p < 0.04, Figs.3). In addition there were increases in high frequency (beta and gamma) power within the core of the nucleus accumbens (significant effects of group, F1,35 > 6.08, p < 0.04 for both bandwidths, Fig.4).

Effects of stimulation cessation

Significant “rebound” effects were seen following the cessation of DBS in the orbitofrontal cortex, mediodorsal thalamic nucleus and the core of the nucleus accumbens. Significant reductions in alpha power were seen in the orbital frontal cortex and the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus which were no longer apparent 48 hours later (significant effect of group, F1,21 > 8.16, p < 0.03, Fig.2 and 3). In addition there were reductions in low/mid (theta and alpha) frequency ranges in the core of the nucleus accumbens (significant effects of group, F1,21 > 11.14, p < 0.01 for both bandwidths, Fig.4). Significant effects of time with significant interactions (F3,21 > 3.67, p < 0.03) indicate that this rebound effect returned to baseline levels 48 hours following the cessation of stimulation (Fig.4).

Summary

Short-term stimulation lead to increases in power across multiple brain regions in predominantly low (delta and theta) frequency bands. With sustained stimulation these effects were replaced by decreases in alpha in the mediodorsal thalamus, and increases in high frequency (beta and gamma) power within the stimulation site. At the cessation of stimulation there were several rebound reductions in power that returned to baseline by 48 hours post-stimulation.

Coherence

Effects of stimulation initiation

Despite the widespread increases in low frequency power throughout the network at the initiation of stimulation, there were no changes in coherence between any of its nodes as indicated by an absence of significant effects of group or time and or significant group interactions (p > 0.05 for all effects in all bandwidths).

Effects during ongoing stimulation

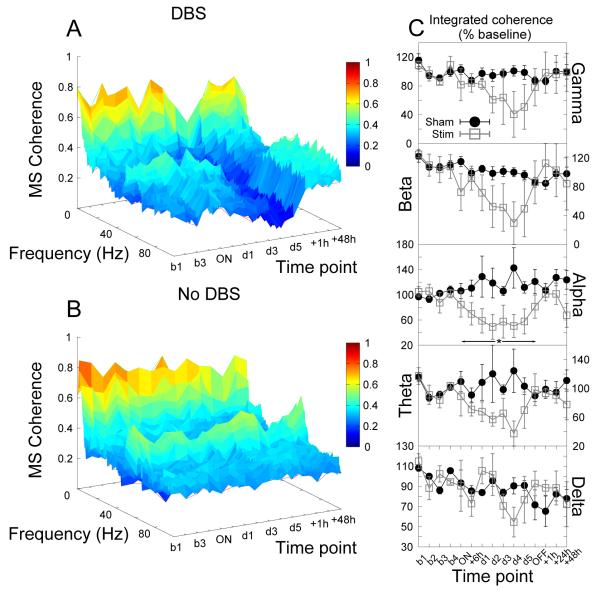

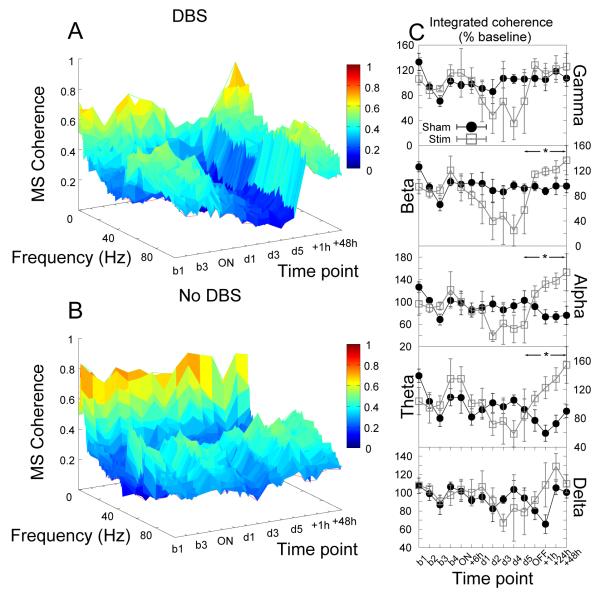

During long-term stimulation of the core of the nucleus accumbens there were significant reductions in alpha coherence between the core of nucleus accumbens and the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus (significant effect of group, F1,35 = 5.88, p = 0.04, see Fig.5).

Figure 5.

Accumbens stimulation produced significant reductions in alpha coherence between the core of the nucleus accumbens and the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus. (A,B) Time-frequency coherograms for stimulated and sham-stimulated animals respectively. (C) Power in each bandwidth as a percentage of baseline at each time point (mean ±SEM). * indicates a significant effect of stimulation.

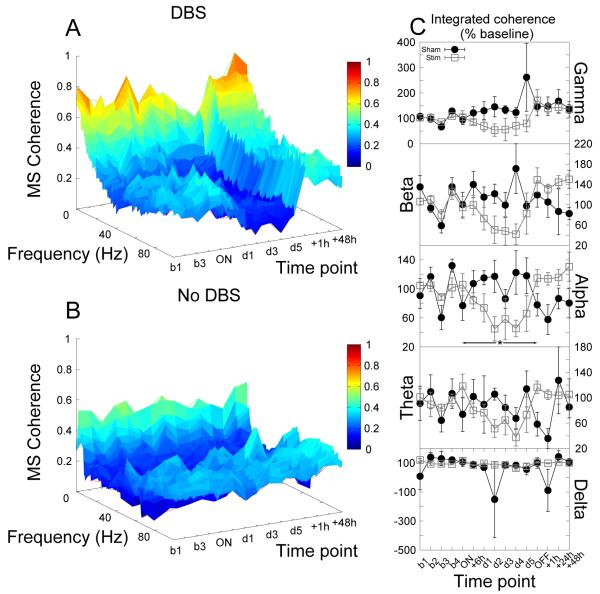

A similar reduction in alpha coherence was also observed between the orbitofrontal cortex and the core of the nucleus accumbens (significant effect of group, F1,35 = 7.27, p = 0.03, Fig.6).

Figure 6.

Accumbens stimulation produced significant reductions in alpha coherence between the core of the nucleus accumbens and the orbitofrontal cortex. (A,B) Time-frequency coherograms for stimulated and sham-stimulated animals respectively. (C) Power in each bandwidth as a percentage of baseline at each time point (mean ±SEM). * indicates a significant effect of stimulation.

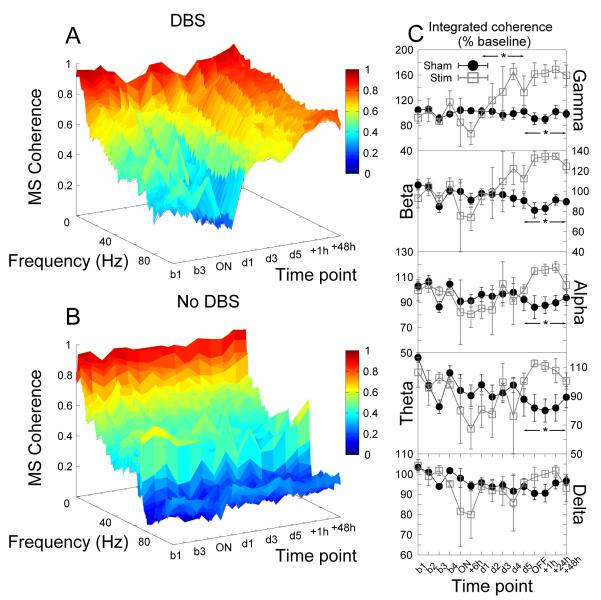

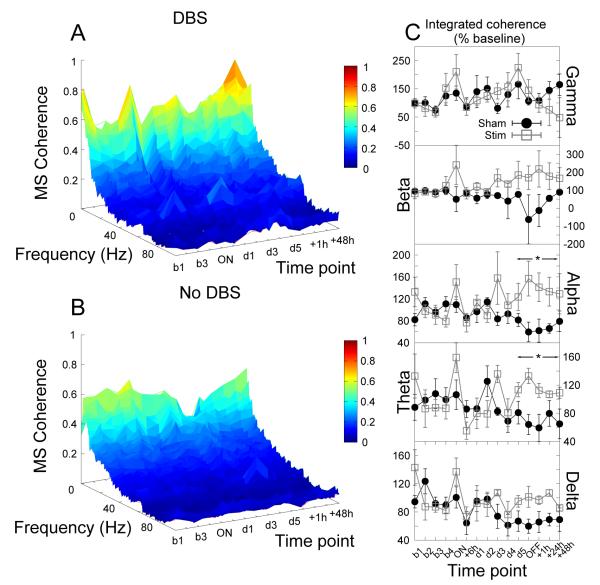

Coherence between the cores of the nucleus accumbens bilaterally exhibited a significantly complex temporal dynamic characterized by an initial decrease in high frequency (gamma) coherence (up to 6 hours) followed by an increasing (and ultimately increased) coherence (significant effect of time, F5,35 = 2.62, p = 0.04, Fig.7).

Figure 7.

Accumbens stimulation produced dynamic changes in coherence between the cores of the nucleus accumbens bilaterally resulting, after 5 days, in a significant elevation in gamma coherence which was sustained well into the post stimulation period. (A,B) Time-frequency coherograms for stimulated and shamstimulated animals respectively. (C) Power in each bandwidth as a percentage of baseline at each time point (mean ±SEM). * indicates a significant effect of stimulation.

Effects of stimulation cessation

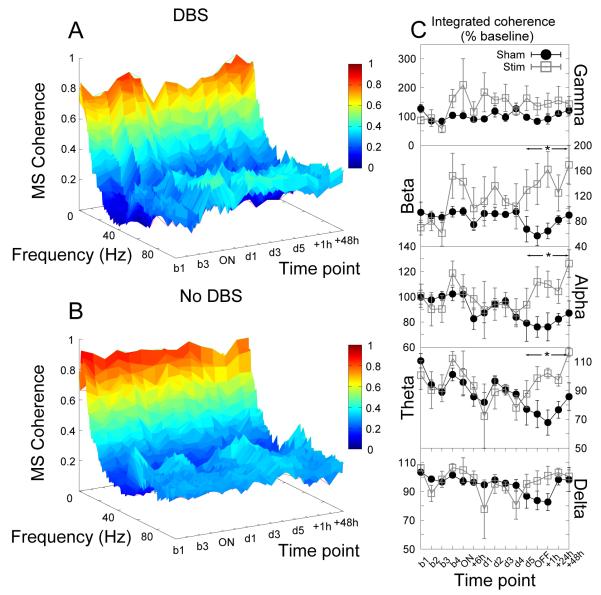

Significant rebound effects were seen following the cessation of stimulation in coherence between multiple brain regions. There were increases in theta, alpha and beta coherence between the prelimbic cortices bilaterally in stimulated animals when compared with their sham-treated controls as indicated by significant effects of group (F1,21 > 7.63, p < 0.03 for all bandwidths, Fig.8).

Figure 8.

Cessation of accumbens stimulation produced significant increases in theta, alpha and beta coherence between the prelimbic cortices bilaterally. (A,B) Time-frequency coherograms for stimulated and sham-stimulated animals respectively. (C) Power in each bandwidth as a percentage of baseline at each time point (mean ±SEM). * indicates a significant effect of stimulation.

Similar effects were seen in coherence between the prelimbic cortex and the accumbens with increases in theta, alpha and beta coherence following the cessation of stimulation (significant effect of group, F1,21 > 7.75, p < 0.03 for all bandwidths, Fig.9).

Figure 9.

Cessation of accumbens stimulation produced significant increases in theta, alpha and beta coherence between the prelimbic cortex and the core of the nucleus accumbens. (A,B) Time-frequency coherograms for stimulated and sham-stimulated animals respectively. (C) Power in each bandwidth as a percentage of baseline at each time point (mean ±SEM). * indicates a significant effect of stimulation.

Increases in theta and alpha coherence between the orbitofrontal cortices bilaterally were also seen in stimulated animals (significant effect of group, F1,21 > 6.03, p < 0.04 for all bandwidths, Fig.10).

Figure 10.

Cessation of accumbens stimulation produced significant increases in theta and alpha coherence between the orbitofrontal cortices bilaterally. (A,B) Time-frequency coherograms for stimulated and sham-stimulated animals respectively. (C) Power in each bandwidth as a percentage of baseline at each time point (mean ±SEM). * indicates a significant effect of stimulation.

Increases in theta, alpha, beta and gamma coherence between the cores of the nucleus accumbens bilaterally were observed (significant effect of group, F1,21 > 10.90, p < 0.01 for all bandwidths) although in the gamma range at least it appears that this may not represent a rebound effect but instead may be an extension of the approach to this state that began before the cessation of stimulation (Fig.7).

Summary

At the onset of stimulation, there were no changes in coherence despite increases in power. With maintained stimulation there were decreases in alpha band coherence across regions and an increase in gamma coherence in the nucleus accumbens bilaterally. Cessation of stimulation caused multiple rebound increases in coherence between multiple regions and across multiple bandwidths.

Discussion

Studies of the effects of DBS in animals have typically relied on shortduration stimulation paradigms, with the effects extrapolated to represent the results observed clinically with much longer-duration stimulation periods. However, in this study we demonstrate that this may not be an accurate representation, since the responses to DBS change over extended periods of time, showing alterations throughout the 5-day stimulation period. Thus, DBS of the nucleus accumbens core produced multiple and specific effects across brain regions; moreover, these responses changed over time. These time-dependent changes reinforce the necessity of carrying out stimulation paradigms of su cient length in order to observe the long-term changes in interactions among these systems. Such delayed actions are consistent with the delayed effects of DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. High frequency bilateral stimulation of the core of the nucleus accumbens produces acute (coincident with the initiation of stimulation) and transient (no longer apparent after 6 hours) increases in the power of low frequency oscillations (delta and theta) in multiple brain regions (prelimbic and orbitofrontal cortices, the core of the nucleus accumbens and the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus) in stimulated animals when compared with sham-treated controls. This apparent “synchronization” of the network at stimulation onset is not reflected in the analysis of coherence between regions suggesting that this system-wide increase in low frequency oscillatory power does not affect coordinated activity between these interconnected regions. In addition, the core of the nucleus accumbens itself exhibits significant increases in the power of high frequency bandwidths (beta and gamma) at the onset of stimulation: an increase that was also no longer apparent after 6 hours only to reemerge some 24 hours later, at which point the increase is maintained for the remainder of the stimulation period.

The acute effects subside rapidly with no further modulation of oscillatory power in regions of the prelimbic and orbitofrontal cortices during stimulation. In the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus this transient increase in low frequency power is replaced by a sustained reduction in mid-frequency (alpha) oscillatory power. The alpha band is further implicated through significant reduction in this bandwidth in the orbitofrontal cortex of stimulated animals following the cessation of stimulation. It is also the alpha band which shows the most significant reductions in coherence between the orbitofrontal cortex and core of the nucleus accumbens, developing with greater than 6 hours of stimulation. A similar reduction in alpha coherence is seen between the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus and the accumbens but not between the prelimbic cortex and the accumbens. It is interesting to note that aberrant alpha rhythmicity has been implicated as a potential marker for the frontal hypofunction associated with schizophrenia [27]. The prelimbic cortex does not remain unaffected by this stimulation paradigm. Cessation of stimulation results in significant increases in coherence between the left and right prelimbic cortices across multiple bandwidths (theta, alpha and beta). Similar changes are also seen in coherence between the prelimbic cortex and the accumbens following the cessation of DBS. Similar elevations in bilateral cortico-cortical coherence are seen in the orbitofrontal cortex following the cessation of stimulation. During stimulation there are significant increases in inter-hemispheric accumbens coherence, particularly at high frequencies and, while it is difficult to reconcile human EEG with rodent LFP, it is interesting to note that OCD is associated with a decrease in inter-hemispheric coherence [28].

These data indicate that long-term high frequency stimulation of the core of the nucleus accumbens leads to an increase in high frequency activity in the stimulated region. Such activity is associated with synchronous inhibition within interneuron networks. This increase in high frequency activity may drive heightened local inhibition and underpin the reduction in alpha coherence seen between the core of the nucleus accumbens and the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus, and between the accumbens and the orbitofrontal cortex. These changes appear to take time to manifest yet revert rapidly following the cessation of stimulation, which is consistent with the clinical response to DBS in OCD patients [20]. Changes in coherence occur over similar timescales as the changes in power seen within the stimulated nucleus, arguably indicating that changes within the stimulated region may drive changes in connectivity between regions linked with the stimulation target. Whereas some of these changes revert rapidly following the cessation of stimulation, changes in coherence between the left and right accumbens persist well into the post stimulation period, implicating a role for long term, plastic changes in the affected system.

It is plausible that DBS may drive increased local inhibition through activation of local GABAergic interneuron networks [10, 12]. The inhibition would provide a rough physiological correlate for the analogous outcomes commonly seen with ablative procedures. This inhibition may then underpin the “functional disconnectivity” seen between the orbitofrontal cortex and the core of the nucleus accumbens, and the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus and the nucleus accumbens. This “functional dysconnectivity” is reminiscent of the “functional dea erentation” commonly reviewed [29-31] and may reconcile the “functional lesion” hypothesis with those data which demostrate modulation of afferent/efferent regions. The fact that the DBS-mediated inhibition does more than just attenuate activity, but also changes coherence between regions, suggests that the resultant alteration may have a more comprehensive therapeutic benefit by restoring normal filtering processes, rather than simply shutting down communication between regions. In particular, the increased coherence between orbitofrontal cortices may increase communication between these structures, thereby contributing to the ability of OCD patients to discount stimulus importance in response to sensory input; a function that is believed to be mediated by the orbitofrontal cortex [32] but is disrupted in OCD patients.

All of the effects reported here display complicated temporal dynamics with transient acute effects in response to the initiation of stimulation, delayed effects during long-term stimulation and rebound effects following interruption of stimulation. The observation that there are changes in power across bands and in multiple brain regions initially, which were no longer apparent with more than 6 hours of stimulation, is an interesting consequence that may have functional implications. Sustained increases in power in individual regions may reflect changes in activity or interneuron control, but the lack of altered coherence likely means that such changes do not affect system-wide alteration in information processing. However, the observation that the changes in power appear to be “replaced” by changes in coherence suggests that the altered coherence may be a compensatory change taking place in the presence of continued stimulation that enables the power to return to a baseline state. Indeed, one may predict that changes in coherence between regions will have a greater impact on information processing than will altered power within single regions.

Caveats

The data reported here show that DBS of the core of the nucleus accumbens acts to alter activity within regions connected with the stimulated region and to alter coordinated activity between regions connected with the stimulated region. The results reported here are unlikely to reflect effects of either electrode insertion or any possible lesioning effect caused by stimulation itself.

The effects coincide with the initiation and cessation of stimulation indicating a precise coincidence with stimulation and cannot be explained purely by electrode insertion. However the effects develop with continued stimulation and such progressive effects may be indicative of a progressive lesion caused by continuous stimulation. Indeed driving electric currents through steel causes electrolytic effects resulting in iron deposition at the electrode tip. This process was used for electrode localization and for these reasons stainless steel is obsolete in human DBS [33]. However, if the effects were to be attributed to a progressive lesion then it would be expected that the lesion - and any effects associated with it - would persist into the post-stimulation period.

In fact what is observed are effects that revert with the cessation of stimulation or rebound effects which revert 48 hours after the cessation of stimulation. Similarly the effects are unlikely to be attributable to significant changes in behavioral state. Data was acquired daily with animals well habituated to the recording procedure and selected randomly to negate any circadian effects. Animals were not engaged in any particular task and data was selected during similar behavioral states (waking restfulness).

The effects described are observations from normal animals, as has been the case in the majority of studies conducted to date [34, 24, 25]. It is reasonable to expect that the oscillatory state of a brain network reflects the pathology of the network. Thus it may be problematic to extrapolate between changes seen in a normal brain network and those arising in a pathological one. None-the-less, these changes indicate the complex temporal dynamics of network activity as a result of continuous deep brain stimulation and highlight the need for chronic stimulation in validated models of disease states in rodents in order to understand mechanisms of action.

Furthermore these data may indicate the need for even greater stimulation periods than those examined here. Even following 5 days of continuous stimulation it is not clear that the effects have reached a steady state. It is possible with longer periods of stimulation that these changes may continue to evolve and chronic stimulation studies should seek to identify this new steady state and the time required to achieve it. In addition, the rapid changes occurring at stimulation initiation and cessation could also yield information relevant to the neural mechanisms involved.

Implications

The thalamus has been proposed as a significant generator of the alpha rhythm [35, 36] and here we show a sustained reduction in alpha rhythmicity in the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus. In addition intracortical networks are thought to generate their own alpha rhythms which may be significantly modulated by specific thalamo-cortical pathways [37]. Here, stimulation lead to a reduction in thalamic alpha power with concurrent reductions in coherence between the orbitofrontal cortex and the accumbens and the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus and the accumbens in the same bandwidth. Arguably, this reduction in alpha coherence throughout the orbitofrontal-striatal-thalamo-cortical pathway may have a significant impact on information processing within this loop given the association between desynchronisation of this rhythm and both the selective attention demands of a task and the novelty of a stimulus [38]. The orbitofrontal cortex is thought to play a critical role in decision making particularly in flexibly representing and updating the value of a stimulus as it guides behaviour [32]. It has been argued that in OCD, patients cannot use sensory feedback to disengage from an action or to extinguish behaviors that are not salient to achieving a goal. Such a condition could arise from a dysfunction within these orbito-striatal-thalamic circuits and their respective roles in regulating function. Here we have shown modulation of information processing in regions - and in a bandwidth - associated with selecting attention and modulation of this bandwidth may underpin some of the clinical benefits observed in OCD patients during DBS.

The data suggest temporarily dynamic alterations in LFP activity with observably different effects during the acute, long-term and withdrawal phases of DBS. The acute effects may indicate a physiological mechanism for some of the side effects reported in the clinic [20]. The sustained effects during the long-term phase of DBS indicate a “functional disconnectivity” between the stimulated region and its afferent and efferent targets. Such a functional disconnectivity may provide a physiological correlate for the commonly reported similarities between lesion treatments and DBS. However, it is now well accepted that DBS does not simply create a “functional lesion” and striatal DBS elicits different effects than those generated by a lesion [39]. These data support and contribute to the evidence indicating significant modulation of neural activity in regions distal to the stimulation target. Further, these data indicate significant changes occurring as a consequence of cessation of DBS providing a possible physiological correlate of some of the effects reported to occur after device failure [20, 40]. The temporal specificity of these changes poses significant challenges to contemporary DBS study design. Too few studies have explored the consequences of long-term DBS yet these studies [41-43] concur with the data presented here that the duration of stimulation plays a significant role in the effects observed. In many behavioral studies acute DBS is the norm raising concerns as to whether the effects reported reflect a clinically relevant effect or an acute side-effect. In many electrophysiology studies analysis is often confined to the post-stimulation period to avoid signal contamination by stimulation artifacts [2, 44] leading some investigators to question the validity of these observations when considering the effects during stimulation [45]. Therefore, there is reason to be cautious about interpreting results as reflective of a clinically relevant effect or a rebound effect caused by the cessation of DBS rather than an effect of DBS itself.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

abbrev. RC, rostrocaudal; ML, mediolateral; DV, dorsoventral

References

- [1].Greenberg BD, Gabriels LA, Malone DA, Rezai AR, Friehs GM, Okun MS, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum for obsessive-compulsive disorder: worldwide experience. Molecular Psychiatry. 2010;15:64–79. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Benazzouz A, Piallat B, Pollak P, Benabid A. Responses of substantia nigra pars reticulata and globus pallidus complex to high frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in rats: electrophysiological data. Neuroscience letters. 1995;189:2–77. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11455-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Beurrier C, Bioulac B, Audin J, Hammond C, Zheng F, Lammert K, et al. High-Frequency Stimulation Produces a Transient Blockade of Voltage-Gated Currents in Subthalamic Neurons High-Frequency Stimulation Produces a Transient Blockade of Voltage-Gated Currents in Subthalamic Neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2001;85:1351–1356. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.4.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Magarinos-Ascone C, Pazo J, Macadar O. High-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus silences subthalamic neurons: a possible cellular mechanism in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience. 2002;115(4):1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Filali M, Hutchison WD, Palter VN, Lozano AM, Dostro-vsky JO. Stimulation-induced inhibition of neuronal firing in human subthalamic nucleus. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Expérimentation cérébrale. 2004;156(3):274–81. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1784-y. doi:10.1007/s00221-003-1784-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Meissner W, Leblois A, Hansel D, Bioulac B, Gross CE, Benazzouz A, et al. Subthalamic high frequency stimulation resets subthalamic firing and reduces abnormal oscillations. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2005;128(Pt 10):2372–82. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh616. doi:10.1093/brain/awh616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Windels F, Bruet N. Effects of high frequency stimulation of subthalamic nucleus on extracellular glutamate and GABA in substantia nigra and globus pallidus. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;12(03):4141–4146. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Windels F, Carcenac C, Poupard A, Savasta M. Pallidal origin of GABA release within the substantia nigra pars reticulata during high-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25(20):5079–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0360-05.2005. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0360-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Winter C, Lemke C, Sohr R, Meissner W, Harnack D, Juckel G, et al. High frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus modulates neurotransmission in limbic brain regions of the rat. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Expérimentation cérébrale. 2008;185(3):497–507. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1171-1. doi:10.1007/s00221-007-1171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].McCracken CB, Grace AA. High-frequency deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens region suppresses neuronal activity and selectively modulates a erent drive in rat orbitofrontal cortex in vivo. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27(46):12601–10. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3750-07.2007. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3750-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li S, Arbuthnott GW, Jutras MJ, Goldberg J.a., Jaeger D. Resonant antidromic cortical circuit activation as a consequence of high-frequency subthalamic deep-brain stimulation. Journal of neurophysiology. 2007;98(6):3525–37. doi: 10.1152/jn.00808.2007. doi:10.1152/jn.00808.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].McCracken CB, Grace AA. Nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation produces region-specific alterations in local field potential oscillations and evoked responses in vivo. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29(16):5354–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0131-09.2009. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0131-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Vedam-Mai V, van Battum EY, Kamphuis W, Feenstra MGP, Denys D, Reynolds B.a., et al. Deep brain stimulation and the role of astrocytes. Molecular psychiatry. 2011:1–8. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.61. doi:10.1038/mp.2011.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rauch S. Neuroimaging and neurocircuitry models pertaining to the neurosurgical treatment of psychiatric disorders. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2003;14:213–223. vii–viii. doi: 10.1016/s1042-3680(02)00114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Saxena S, Brody A, Maidment K, Dunkin J, Colgan M, Alborzian S, et al. Localized orbitofrontal and subcortical metabolic changes and predictors of response to paroxetine treatment in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:683–693. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Greenberg B, Murphy D, Rasmussen S. Neuroanatomically based approaches to obsessivecompulsive disorder. Neurosurgery and transcranial magnetic stimulation. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 2000;23:671–686. xii. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dougherty D, Baer L, Cosgrove G, Cassem E, Price B, Nierenberg A, et al. Prospective long-term follow-up of 44 patients who received cingulotomy for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. The American journal of psychiatry. 2002;159:269–275. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Greenberg B, Price L, Rauch S, Friehs G, Noren G, Malone D, et al. Neurosurgery for intractable obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression: critical issues. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2003;14:199–212. doi: 10.1016/s1042-3680(03)00005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rauch S, Dougherty D, Malone D, Rezai A, Friehs G, Fischman A, et al. A functional neuroimaging investigation of deep brain stimulation in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of neurosurgery. 2006;104:558–565. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.104.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Greenberg BD, Malone D, Friehs GM, Rezai AR, Kubu CS, Malloy PF, et al. Three-year outcomes in deep brain stimulation for highly resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(11):2384–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301165. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].van Kuyck K, Demeulemeester H, Feys H, De Weerdt W, Dewil M, Tousseyn T, et al. Effects of electrical stimulation or lesion in nucleus accumbens on the behaviour of rats in a T-maze after administration of 8-OH-DPAT or vehicle. Behavioural Brain Research. 2003;140(1-2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sesia T, Temel Y, Lim LW, Blokland A, Steinbusch HWM, Visser-Vandewalle V. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens core and shell: opposite effects on impulsive action. Experimental neurology. 2008;214(1):135–9. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.07.015. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.07.015. URL http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18762185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mundt A, Klein J, Joel D, Heinz A, Djodari-Irani A, Harnack D, et al. High-frequency stimulation of the nucleus accumbens core and shell reduces quinpirole-induced compulsive checking in rats. The European journal of neuroscience. 2009;29(12):2401–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06777.x. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sesia T, Bulthuis V, Tan S, Lim LW, Vlamings R, Blokland A, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens shell increases impulsive behavior and tissue levels of dopamine and serotonin. Experimental neurology. 2010;225(2):302–9. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.06.022. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.06.022. URL http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20615406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ran Dijk A, Mason O, Klompmakers A.a., Feenstra MGP, Denys D. Unilateral deep brain stimulation in the nucleus accumbens core does not a ect local monoamine release. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.04.034. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Erez Y, Tischler H, Moran A, Bar-Gad I. Generalized frame-work for stimulus artifact removal. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2010;191(1):45–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.06.005. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Knyazeva MG, Jalili M, Meuli R, Hasler M, De Feo O, Do KQ. Alpha rhythm and hypofrontality in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2008;118(3):188–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01227.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Velikova S, Locatelli M, Insacco C, Smeraldi E, Comi G, Leocani L. Dysfunctional brain circuitry in obsessive-compulsive disorder: source and coherence analysis of EEG rhythms. NeuroImage. 2010;49(1):977–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.015. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Vitek J. Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation: excitation or inhibition. Movement disorders. 2002;17:3–6. doi: 10.1002/mds.10144. doi:10.1002/mds.10144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Garcia L, D’Alessandro G, Bioulac B, Hammond C. High-frequency stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: more or less? Trends in neurosciences. 2005;28(4):209–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.02.005. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Birdno MJ, Grill WM. Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation in movement disorders as revealed by changes in stimulus frequency. Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 2008;5(1):14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.10.067. doi:10.1016/j.nurt.2007.10.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Schoenbaum G, Roesch M, Stalnaker T. Orbitofrontal cortex, decision-making and drug addiction. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Volkmann J, Herzog J, Kopper F, Deuschl G. Introduction to the programming of deep brain stimulators. Movement disorders. 2002;17(S3):S181–S187. doi: 10.1002/mds.10162. doi:10.1002/mds.10162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Quinkert AW, Schi ND, Pfa DW. Temporal patterning of pulses during deep brain stimulation a ects central nervous system arousal. Behavioural brain research. 2010;214(2):377–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.06.009. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Goldman RI, Stern JM, Engel J, Cohen MS. Simultaneous EEG and fMRI of the alpha rhythm. Neuroreport. 2002;13(18):2487–92. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000047685.08940.d0. doi:10.1097/01.wnr.0000047685.08940.d0. URL http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12499854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Schreckenberger M, Lange-Asschenfeldt C, Lange-Asschenfeld C, Lochmann M, Mann K, Siessmeier T, et al. The thalamus as the generator and modulator of EEG alpha rhythm: a combined PET/EEG study with lorazepam challenge in humans. NeuroImage. 2004;22(2):637–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.01.047. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.01.047. URL http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15193592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lopez da Silva F, Vos J, Mooibroek J, Van Rotterdam A. Relative contributions of intracortical and thalamo-cortical processes in the generation of alpha rhythms, revealed by partial coherence analysis. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophsiology. 1980;50:449–456. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(80)90011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Winsun WV, Sergeant J, Geuze R. The functional significance of event-related desynchronization of alpha rhythm in attentional and activating tasks. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophsiology. 1984;58:519–524. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(84)90042-7. URL http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0013469484900427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Rodriguez-Romaguera J, Do Monte FHM, Quirk GJ. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral striatum enhances extinction of conditioned fear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;2012:1–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200782109. doi:10.1073/pnas.1200782109. URL http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1200782109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Vora AK, Ward H, Foote KD, Goodman WK, Okun MS. Rebound symptoms following battery depletion in the NIH OCD DBS cohort: clinical and reimbursement issues. Brain stimulation. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2011.10.004. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bacci JJ, Absi EH, Manrique C, Baunez C, Salin P, Kerkerian-Le Go L. Differential effects of prolonged high frequency stimulation and of excitotoxic lesion of the subthalamic nucleus on dopamine denervation-induced cellular defects in the rat striatum and globus pallidus. The European journal of neuroscience. 2004;20(12):3331–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03792.x. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Meissner W, Guigoni C, Cirilli L, Garret M, Bioulac BH, Gross CE, et al. Impact of chronic subthalamic high-frequency stimulation on metabolic basal ganglia activity: a 2-deoxyglucose uptake and cytochrome oxidase mRNA study in a macaque model of Parkinson’s disease. The European journal of neuroscience. 2007;25(5):1492–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05406.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Oueslati A, Sgambato-Faure V, Melon C, Kachidian P, Gubellini P, Amri M, et al. High-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus potentiates L-DOPA-induced neurochemical changes in the striatum in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27(9):2377–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2949-06.2007. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2949-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wu YR, Levy R, Ashby P, Tasker RR, Dostrovsky JO. Does stimulation of the GPi control dyskinesia by activating inhibitory axons? Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2001;16(2):208–16. doi: 10.1002/mds.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Bar-Gad I, Elias S, Vaadia E, Bergman H. Complex locking rather than complete cessation of neuronal activity in the globus pallidus of a 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-treated primate in response to pallidal microstimulation. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24(33):7410–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1691-04.2004. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1691-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]