Background: Dopamine transporter (DAT) activity is regulated by PKC.

Results: We identify Ser-7 as a PKC phosphorylation site on DAT and show that phosphorylation conditions and Ser-7 mutation alter cocaine analog binding characteristics.

Conclusion: Ser-7 phosphorylation affects cocaine analog binding by altering DAT conformational equilibrium.

Significance: Ser-7 phosphorylation of DAT may impact recognition and action of cocaine.

Keywords: Calcium-Calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase (CaMK), Mass Spectrometry (MS), Protein Conformation, Protein Kinase A (PKA), Protein Kinase C (PKC), Peptide Mapping, Zinc Binding

Abstract

As an approach to elucidating dopamine transporter (DAT) phosphorylation characteristics, we examined in vitro phosphorylation of a recombinant rat DAT N-terminal peptide (NDAT) using purified protein kinases. We found that NDAT becomes phosphorylated at single distinct sites by protein kinase A (Ser-7) and calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (Ser-13) and at multiple sites (Ser-4, Ser-7, and Ser-13) by protein kinase C (PKC), implicating these residues as potential sites of DAT phosphorylation by these kinases. Mapping of rat striatal DAT phosphopeptides by two-dimensional thin layer chromatography revealed basal and PKC-stimulated phosphorylation of the same peptide fragments and comigration of PKC-stimulated phosphopeptide fragments with NDAT Ser-7 phosphopeptide markers. We further confirmed by site-directed mutagenesis and mass spectrometry that Ser-7 is a site for PKC-stimulated phosphorylation in heterologously expressed rat and human DATs. Mutation of Ser-7 and nearby residues strongly reduced the affinity of rat DAT for the cocaine analog (−)-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-fluorophenyl) tropane (CFT), whereas in rat striatal tissue, conditions that promote DAT phosphorylation caused increased CFT affinity. Ser-7 mutation also affected zinc modulation of CFT binding, with Ala and Asp substitutions inducing opposing effects. These results identify Ser-7 as a major site for basal and PKC-stimulated phosphorylation of native and expressed DAT and suggest that Ser-7 phosphorylation modulates transporter conformational equilibria, shifting the transporter between high and low affinity cocaine binding states.

Introduction

The dopamine (DA)5 transporter (DAT) is a phosphoprotein that drives reuptake of extracellular DA following transmitter release and is a target for abused psychostimulants, including amphetamine (AMPH), methamphetamine (METH), and cocaine, as well as for agents used to monitor and treat dopaminergic diseases (1). DAT belongs to the neurotransmitter sodium symporter family of transporters that consist of 12 transmembrane (TM) domains with large intracellularly oriented N and C termini (2). Neurotransmitter sodium symporter proteins translocate substrates by an alternating access mechanism in which transporters cycle between outwardly facing, occluded, and inwardly facing states (3). The uptake inhibitor cocaine binds to the outwardly facing form of DAT and prevents structural rearrangements needed for transport, whereas AMPH and METH promote reverse transport (efflux) of preloaded substrate (4–10). Forward and reverse DA transport are regulated by interactions of DAT with associated proteins, including syntaxin 1A (syn 1A) (11–13), and by several kinases, including protein kinase C (PKC), calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (14, 15). The overall capacity for DAT-mediated DA clearance is thus established through the integration of multiple molecular inputs, and dysregulation of these processes may play a role in drug addiction and other DA disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and schizophrenia (16, 17).

Several properties of DAT, including forward and reverse transport, endocytosis, and phosphorylation, are affected by PKC and AMPH/METH exposure (18–20), and AMPH/METH-stimulated DA efflux has also been linked to Ca2+ and CaMKII (7, 21, 22). Removal of DAT phosphorylation sites does not affect PKC- or AMPH-induced transporter endocytosis or down-regulation (20, 23, 24) but has been reported to prevent AMPH-induced efflux (6), suggesting that reverse transport requires transporter phosphorylation. However, our laboratory has found that deletion of the PKC phosphorylation domain does not impair AMPH-stimulated efflux (25), leaving the mechanistic requirements for phosphorylation in this process unclear. Thus, although numerous findings support the involvement of PKC and CaMKII in DA transport down-regulation and DA efflux, it remains to be established if these events are dependent upon phosphorylation of DAT by these kinases.

To further explore the role of phosphorylation in DAT regulatory functions, we have sought to identify specific DAT phosphorylation sites and to determine whether regulatory kinases act on DAT directly or induce effects indirectly. The phosphorylation pattern of rat (r) DAT is complex, occurring on serine (Ser) and threonine (Thr) at a ratio of ∼90 to 10% (26, 27). Threonine phosphorylation occurs on Thr-53, present in a proline-directed motif close to the intracellular end of TM1 (28, 29), whereas the majority of basal, PKC-induced, and AMPH-induced phosphorylation occurs in a cluster of serines present within the first 21 N-terminal residues (20, 24, 27). PKC-induced phosphorylation likely occurs at multiple sites, as individual Ser to Ala mutagenesis of distal N-terminal serines does not eliminate 32PO4 labeling (30). Efforts to identify the specific residues phosphorylated within this cluster using site-directed mutagenesis have been extremely problematic due to the difficulties of quantifying partial phosphorylation reductions in the context of different transporter levels. Finally, it is not known if PMA-stimulated phosphorylation of N-terminal serines is catalyzed directly by PKC or by downstream kinases or if DAT is also phosphorylated by other kinases that regulate transport and efflux.

As one approach to examining these issues, we developed an in vitro phosphorylation assay that uses the recombinant rDAT N-terminal tail sequence (NDAT) as a substrate for purified protein kinases (28). We previously showed that NDAT is an excellent substrate for multiple kinases that regulate DAT activity and phosphorylation (28). Here, we identify the NDAT residues phosphorylated by protein kinase A (PKA), CaMKII, and PKCα, and we extend our findings to the full-length transporter, identifying Ser-7 as a PKC-dependent phosphorylation site in rat striatal DAT and heterologously expressed rat and human DAT. Unexpectedly, we found that mutation of Ser-7 strongly decreased the binding affinity of DAT for the cocaine analog (−)-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-fluorophenyl) tropane (CFT) and impacted zinc modulation of CFT binding. Conversely, we found in rat striatal tissue that treatments that stimulate transporter phosphorylation increase the affinity of DAT for CFT. These results identify Ser-7 as a major phosphorylation site on DAT and support Ser-7 phosphorylation as a mechanism for regulation of transporter conformational equilibrium and cocaine binding.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals and Materials

Carrier-free radiolabeled inorganic phosphate (32PO4) and [γ-32P]ATP (7000 Ci/mmol) were purchased from MP Biomedicals (Irvine, CA). [3H]CFT (76 Ci/mmol) was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. [3H]Dopamine (45 Ci/mmol), protein A-Sepharose, and Hyperfilm MP were from GE Healthcare. (−)-Cocaine, CFT, mazindol, dopamine, thermolysin, molecular weight markers, and alkaline phosphatase-linked anti-mouse IgG were from Sigma. Trypsin was from Waters (Milford, MA). PMA, okadaic acid (OA), oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG), PKA catalytic subunit, CaMKII, and PKCα were from Calbiochem-EMD Biosciences. Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay reagent was from Thermo Scientific. Complete mini protease inhibitor was from Roche Applied Science. IMPACT-CN kit (Intein expression vectors, etc.) was obtained from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Site-directed mutagenesis QuikChange® kit was from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). Synthesized oligonucleotides were from MWG Biotech, Inc. (High Point, NC). The anti-GFP antibody was from Invitrogen. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma or Fisher. Rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and were maintained in compliance with the guidelines established by the University of North Dakota Institutional Animal Care and Use committee and the National Institutes of Health.

NDAT Production and Phosphorylation

Site-directed mutagenesis of NDAT was performed on a PTYB plasmid containing WT NDAT (New England Biolabs) using appropriate primers (MWG Biotech) and the Stratagene QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis kit as described previously (28). Mutations were verified by sequencing (Alpha Biolaboratories, Inc.). In vitro phosphorylation of NDAT with PKA catalytic subunit, CaMKII, and PKCα was performed as described previously (28) using equal amounts of WT and mutant NDAT protein (1.6 μg) for all experiments. 32P levels were quantified by densitometry; WT levels were set to 100%, and mutant levels were expressed as a fraction of WT. Statistical evaluation of phosphorylation levels was performed by ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. Unless indicated otherwise, the results were replicated in three or more independent experiments.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting of rDAT and NDAT were performed as described previously using polyclonal Ab16 or monoclonal antibody 16 (mAb16) directed against rDAT amino acids 42–59 (27, 31). NDAT and DAT samples were run on 10–20 or 4–20% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, respectively.

Site-directed Mutagenesis and Stable Cell Expression

Site-directed mutagenesis of rDAT was performed as described above (QuikChange®, Stratagene), and all mutations were verified by dideoxy sequencing. WT and mutant rDATs were subcloned into the LZRS-MS-neo vector. Stable expressing DAT lines were generated as described previously (32). Briefly, Phoenix cells (5 × 105) were plated and transfected (FuGENE 6, Roche Applied Science) followed by selection (48 h) with 4 μg/ml puromycin. After verification of rDAT expression via DA transport assay, Phoenix cells were plated (5 × 106/100-mm dish) in regular medium for viral harvest. After 24 h at 32 °C, the medium containing virus was collected and filtered (45 μm). Viral supernatant with 4 μg/ml Polybrene was added to LLC-PK1 target cells and incubated for 6 h at 32 °C. Viral supernatant was then removed, and cells were incubated overnight at 37 °C followed by viral incubation a second time the next day. After ∼48 h, regular medium was replaced with medium supplemented with G418 (250 μg/ml) to select for cells with a stable integration of WT or mutant rDAT. Expression of rDAT was confirmed by Western blot analysis.

Phosphorylation of DAT in Heterologously Expressing Cells

LLC-PK1 cells stably expressing WT or mutant rDATs were grown and used for 32PO4 phosphorylation as described previously (20). Briefly, plated cells were labeled with phosphate-free medium containing 1 mCi/ml 32PO4 for 2 h at 37 °C, followed by application of 1 μm PMA for 30 min. Cells were washed, collected by scraping, and pelleted by centrifugation at 2000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The cells were lysed with 10 mm triethanolamine/acetate buffer, pH 7.8, containing 2 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.1% Triton X-100, and lysates were centrifuged at 4000 × g for 2 min. The resulting supernatants were supplemented with SDS to a final concentration of 0.5% and further centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min to remove insoluble material. Aliquots were assessed by immunoblotting with MAb16 to determine total DAT levels, and equal amounts of DAT were immunoprecipitated with Ab16 followed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography using Hyperfilm MP. Band densities were determined by densitometry using images within the linear range of intensities, and stimulated and mutant values were expressed as a fraction of WT basal level set to 100% as described previously (20). Phosphorylation values were assessed statistically by ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc test.

Phosphorylation of DAT in Striatal Slices

Metabolic phosphorylation of DAT in rat striatal slices was performed by labeling tissue with 1–5 mCi/ml 32PO4 for 2 h and treating with vehicle or 10 μm OAG plus 1 μm OA for 30 min as described previously (27). Tissue was lysed with 1% SDS and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min. The soluble fraction was collected, diluted to 0.1% SDS, and immunoprecipitated with Ab16 followed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Peptide Mapping

NDAT samples phosphorylated in vitro by PKA, CaMKII, or PKCα with [γ-32P]ATP and rat striatal DAT metabolically phosphorylated with 32PO4 were immunoprecipitated with Ab16 (33) and subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. 32P-Labeled proteins were excised from the gel, electroeluted, and dialyzed overnight against water. Samples were acetone-precipitated, reduced and alkylated, and digested with 20 μg of thermolysin for 2 h at 60 °C followed by addition of 20 μg of trypsin at 37 °C and incubated for 24 h. Peptides were suspended in pH 1.9 electrophoresis buffer (acetic acid 7.8%, formic acid 2.5%), spotted onto TLC plates, and separated in the first dimension by electrophoresis for 35 min at 1500 V. Plates were dried and peptides resolved in the second dimension by ascending chromatography, dried, and exposed to x-ray film (34).

Tandem Mass Spectrometry Analysis (LC-MS/MS)

HEK293-hDAT cells were used that stably express YFP-tagged human (h) DAT as published previously (35). The tag at the N-terminal end of both transporters does not alter their functional characteristics (35, 36). The cells were cultivated on 10-cm dishes in DMEM complemented with fetal calf serum (10%), l-glutamine (1%), glucose (4.5 g·liter−1), and gentamycin (50 μg·ml−1) at 37 °C, 95% humidity, and 5% CO2. The cells were treated with 0.25 μm OA for 2 h and subsequently solubilized in lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 5 mm sodium fluoride, 5 mm sodium pyrophosphate and a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science) on a tube rotator for 2 h at 4 °C. After centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was collected and incubated overnight with a rabbit anti-GFP polyclonal antibody. Immune complexes were collected with protein G-Sepharose and washed extensively, and bound proteins were eluted in Laemmli buffer (63 mm Tris-HCl, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 3% 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 mm dithiothreitol, 0.0025% bromphenol blue, pH 6.8) at 95 °C for 3 min. Eluted proteins were size-fractionated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining, and the indicated band was excised. Gel pieces were destained with 50% acetonitrile in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate and dried in a speed vacuum concentrator. After reduction and alkylation of cysteine residues, gel pieces were washed and dehydrated. Dried gel pieces were rehydrated with 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0, containing 10 ng/μl trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI), and incubated for 18 h at 37 °C. The digested peptide mixtures were extracted with 50% acetonitrile in 5% formic acid and concentrated in a speed vacuum concentrator for LC-MS/MS. An ion trap mass spectrometer (HCT, BrukerDaltonics, Bremen, Germany) coupled with an Ultimate 3000 nano-HPLC system (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) was used for LC-MS/MS data acquisition. A PepMap100 C-18 trap column (300 μm × 5 mm) and PepMap100 C-18 analytic column (75 μm × 150 mm) were used for reverse phase chromatographic separation with a flow rate of 300 nl/min. The two buffers used for the reverse phase chromatography were 0.1% formic acid/water (buffer A) and 0.08% formic acid/acetonitrile (buffer B) with a 125-min gradient (4–30% buffer B for 105 min, 80% buffer B for 5 min, and 4% buffer B for 15 min). Eluted peptides were then directly sprayed into the mass spectrometer to record peptide spectra over the mass range of m/z 350–1500 and MS/MS spectra in information-dependent data acquisition over the mass range of m/z 100–2800. Repeatedly, MS spectra were recorded followed by three data-dependent CID MS/MS spectra generated from the four highest intensity precursor ions. The MS/MS spectra were interpreted with the Mascot search engine (Matrix Science, London, UK). Database searches through Mascot were performed with a mass tolerance of 0.5 Da, a MS/MS tolerance of 0.5 Da, three missing cleavage sites, and carbamidomethylation on cysteine, oxidation on methionine, and phosphorylation on serine/threonine were allowed. Each filtered MS/MS spectrum exhibiting possible phosphorylation was manually checked and validated (37, 38).

[3H]CFT Binding in Cells

LLC-PK1 cells stably expressing WT and mutant rDATs were grown to 80–90% confluence and washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution. Cells were incubated with 0–300 nm [3H]CFT in KRH buffer for 2 h at 4 °C for saturation analysis or incubated with 1–50 μm ZnCl2 plus 5 nm [3H]CFT for 2 h at 4 °C for zinc dose-response assays. All binding was performed in triplicate with nonspecific binding determined in the presence of 10 μm mazindol. At the end of the incubation, cells were washed twice with KRH buffer and lysed with 1% Triton X-100, and samples were assessed for radioactivity by liquid scintillation counting. For saturation analyses, Bmax and Kd values were determined by nonlinear regression using Prism 3 software, and data were analyzed for statistical significance using Student's t test. For Zn2+ studies, control binding values for each cell type were normalized to 100%, and binding levels for treatment conditions were converted to percent control. Values were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

[3H]CFT Binding in Rat Striatal Membranes

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (175–300 g) were decapitated and the striata rapidly removed and weighed. The tissue was sliced into 350-μm slices using a McElvain Tissue Chopper and placed into wells of a 12-well culture plate containing oxygenated Krebs-bicarbonate buffer (25 mm NaHCO3, 125 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1.5 mm CaCl2, 5 mm MgSO4, and 10 mm glucose, pH 7.3). Slices were preincubated for 30 min at 30 °C, with shaking at 105 rpm, followed by treatment with vehicle or 1 μm OA plus 10 μm OAG for an additional 30 min. Oxygen (95% O2, 5% CO2) was gently blown across the top of the plate during the incubation. The slices were homogenized with a Polytron PT1200 homogenizer (Kinematica, Basel, Switzerland) for 8 s and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 3 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 17,000 × g for 12 min, and the pellet was resuspended in modified Krebs phosphate buffer (126 mm NaCl, 4.8 mm KCl, 16 mm potassium phosphate, 1.4 mm MgSO4, 10 mm glucose, 1.1 mm ascorbic acid, and 1.3 mm CaCl2, pH 7.4) to 20 mg/ml original wet weight. Triplicate samples of membranes were incubated on ice with 1–300 nm [3H]CFT in modified Krebs phosphate buffer for 2 h at 4 °C followed by rapid vacuum filtration using a Brandel tissue harvester over Whatman GF/B glass fiber filters soaked for 1 h in 0.1% BSA. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 100 μm cocaine. Filtered samples were assessed for radioactivity by liquid scintillation counting. Bmax and Kd values were determined using Prism 3 software by nonlinear regression, and values were analyzed for statistical significance using Student's t test.

RESULTS

Identification of PKA, CaMKII, and PKCα Phosphorylation Sites on NDAT

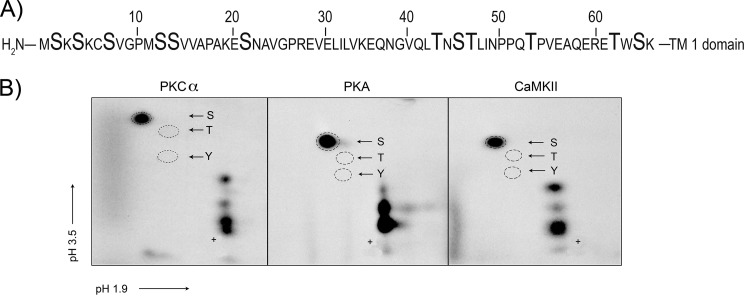

Fig. 1A shows the amino acid sequence of NDAT, which contains all of the residues in the intracellular N-terminal domain of rDAT up to the beginning of TM1. We previously showed that NDAT is robustly phosphorylated in vitro by PKA, CaMKII, and PKCα, and here we undertook the identification of the phosphorylation sites for these kinases. Because of the large number of potential phosphate acceptors in the sequence (8 Ser and 4 Thr), we first determined the phosphoamino acid content for each condition using two-dimensional TLC. Results show that each of these kinases phosphorylate NDAT exclusively on serine (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Phosphoamino acid analysis of NDAT phosphorylated by PKCα, PKA, and CaMKII. A, amino acid sequence of NDAT, residues 1–65 of the rDAT cytoplasmic N-terminal domain up to the presumed beginning of the first transmembrane spanning helix. Ser and Thr residues that represent potential sites of phosphorylation are indicated in boldface type. B, NDAT samples phosphorylated in vitro with PKCα, PKA, or CaMKII in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP were subjected to phosphoamino acid analysis by two-dimensional TLC and autoradiography. Phosphoamino acid standards are indicated with circles (S, phosphoserine, T, phosphothreonine, Y, phosphotyrosine). +, origin.

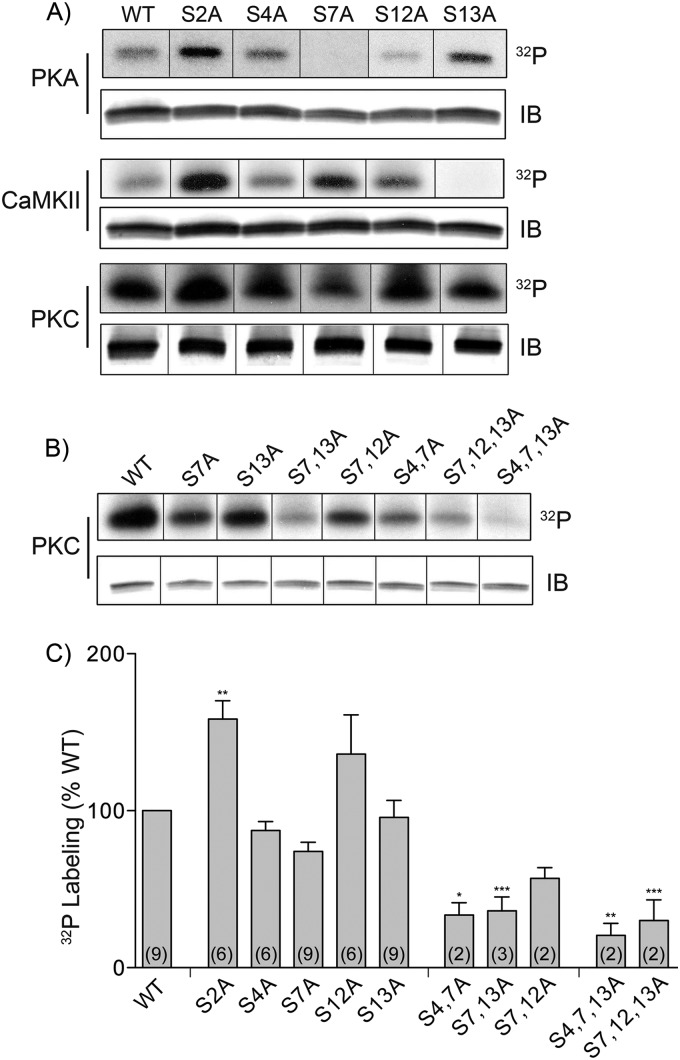

To identify the specific serines phosphorylated, we generated NDATs possessing individual Ser → Ala mutations at residues 2, 4, 7, 12, and 13, focusing on the N-terminal Ser cluster phosphorylated in vivo (20, 27). Phosphorylation of NDAT by PKA was eliminated in the S7A mutant, and phosphorylation by CaMKII was eliminated in the S13A mutant (Fig. 2A), strongly suggesting that PKA and CaMKII phosphorylate NDAT exclusively on Ser-7 and Ser-13, respectively. PKCα phosphorylation of NDAT was more complex, as 32P labeling was not abolished by any of the individual Ser → Ala mutations (Fig. 2A). Quantification of band intensities relative to the WT protein showed no statistically significant reduction in phosphorylation for any of the mutants, although trends toward reduction were seen for S4A (87 ± 6% of WT) and S7A (74 ± 6% of WT).

FIGURE 2.

Phosphorylation of Ser → Ala NDAT mutants. A and B, equal amounts of indicated NDAT WT and Ser → Ala mutants were phosphorylated in vitro by PKA, CaMKII, or PKCα, immunoprecipitated, and subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (upper panels) or immunoblotting (IB) (lower panels). C, histogram showing PKC-induced phosphorylation levels of WT and NDAT Ser → Ala mutants, expressed as percent of WT phosphorylation (means ± S.E.; n as indicated in parentheses). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 relative to WT (ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test).

Accordingly, we generated various NDAT double and triple Ser → Ala combinations for further PKCα phosphorylation analysis (Fig. 2, B and C). Phosphorylation levels were significantly reduced for S4A,S7A NDAT (34 ± 8% of WT) (p < 0.05), S7A,S13A NDAT (36 ± 9% of WT) (p < 0.001), S4A,S7A,S13A NDAT (20 ± 8% of WT) (p < 0.01), and S7A,S12A,S13A (30 ± 13% of WT) (p < 0.001). These results indicate that a large fraction of NDAT in vitro phosphorylation by PKCα occurs on serines 4, 7, and 13, although we cannot eliminate the possibility that mutation of these serines indirectly inhibits phosphorylation of other residues. In addition, the small amount of radioactivity remaining on S4A,S7A,S13A indicates the presence of phosphorylation on additional serines.

We also consistently found increased phosphorylation of S2A NDAT by all three kinases, with the PKCα phosphorylation level reaching 158 ± 12% of WT (p < 0.001), indicating that Ser-2 is not a phosphorylation site but that its mutation alters the in vitro phosphorylation of other NDAT residues.

NDAT Phosphopeptide Mapping Analysis

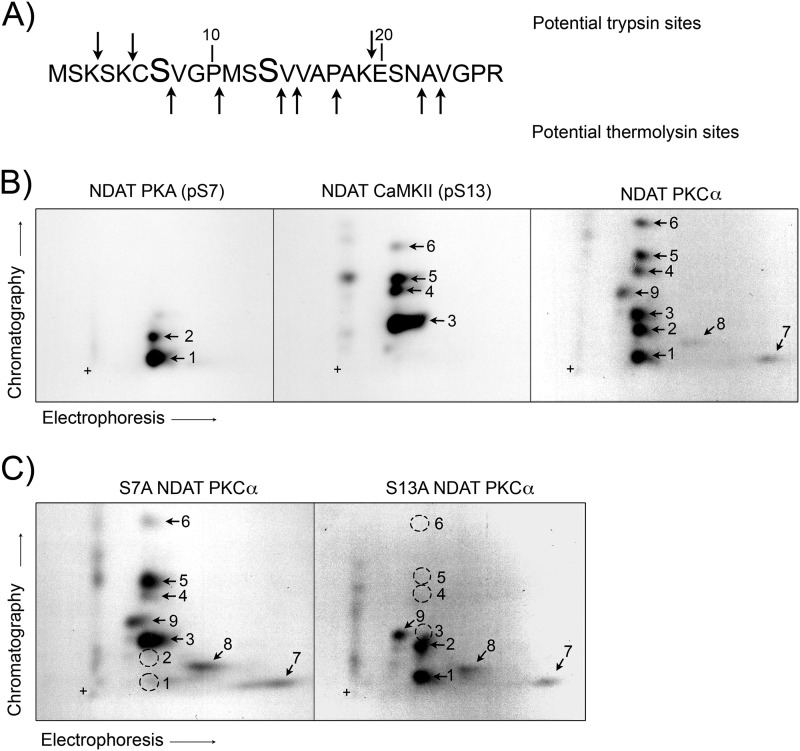

Because NDAT is exclusively phosphorylated by PKA at Ser-7 and by CaMKII at Ser-13, we developed a strategy to use phosphopeptides derived from these samples as markers in two-dimensional TLC to identify phosphorylation sites on native transporters. To characterize the two-dimensional TLC patterns of NDAT phosphopeptides, 32P-labeled samples phosphorylated by PKA, CaMKII, or PKCα were immunoprecipitated, gel-purified, proteolytically digested, and subjected to two-dimensional TLC in parallel. Proteolysis was performed with trypsin, which cleaves on the C-terminal side of lysine and arginine, plus thermolysin, which cleaves on the N-terminal side of aromatic and bulky hydrophobic residues, to separate all Ser with the exception of Ser-12 and Ser-13 (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Phosphopeptide maps of NDAT. A, residues 1–27 of NDAT showing potential trypsin and thermolysin cleavage sites (arrows). Ser-7 and Ser-13 are indicated in boldface type. B, WT NDAT samples phosphorylated in vitro by PKA, CaMKII, or PKCα. C, S7A and S13A NDATs phosphorylated in vitro by PKCα were subjected to two-dimensional TLC peptide mapping and autoradiography exactly in parallel. Dotted circles indicate position of phosphopeptide spots that were present in WT samples but are absent in mutants. +, origin.

In three independent experiments, we found that Ser(P)-7 and Ser(P)-13 NDAT peptides generated from PKA and CaMKII phosphorylation migrated with clearly distinct patterns (Fig. 3B, left and center panels). Although these NDAT samples are phosphorylated on single serines, two to three major and occasional minor fragments were typically generated, indicative of incomplete proteolysis. PKA phosphorylated NDAT peptides containing Ser(P)-7 were numbered 1 and 2, and CaMKII phosphorylated NDAT peptides containing Ser(P)-13 were numbered 3–6.

The right panel in Fig. 3B shows a representative phosphopeptide map of PKCα-phosphorylated NDAT, which contained nine reproducible spots. The spectrum of fragments was consistent with a combination of Ser(P)-7 peptides (spots 1 and 2) and Ser(P)-13 peptides (spots 3–6), based on alignment of these spots with those from PKA and CaMKII samples, and as supported by Ser-7 and Ser-13 mutagenesis data. The presence of spots 7–9 not seen in the PKA- and CaMKII-NDAT maps supports PKCα phosphorylation of one or more additional residues, possibly Ser-4, as indicated by mutagenesis.

Although the NDAT phosphopeptide maps produced in each kinase condition and across multiple experiments showed significant qualitative similarities, slight variations in fragment migration typical of two-dimensional TLC were occasionally seen. Thus, to further validate the identity of these peptides and to assess the completeness of digestion with respect to separation of serines, we analyzed PKCα-phosphorylated S7A and S13A NDATs in parallel with PKA-, CaMKII-, and PKCα-phosphorylated WT NDAT samples. In the S7A NDAT sample, spots 1 and 2 were absent (dotted circles), whereas spots 3–9 remained present (Fig. 3C, left panel). The findings that spots 1 and 2 align in PKCα- and PKA-phosphorylated NDAT maps and are absent in PKCα-phosphorylated S7A NDAT strongly support the presence of Ser(P)-7 in these peptides and importantly demonstrate that fragments 1 and 2 contain only Ser(P)-7 and are not incompletely digested peptides that possess additional phosphorylated residues (e.g. Ser-4 or Ser-13). Similarly, in PKCα-phosphorylated S13A NDAT, spots 3–6 were absent (dotted circles), whereas spots 1, 2, and 7–9 remained present, indicating that fragments 3–6 are phosphorylated only on Ser-13 and do not contain Ser-7 or other phosphorylated residues (Fig. 3B, right panel). The retention of spots 7–9 in both the S7A and S13A samples further verifies the phosphorylation of other NDAT serines.

Rat Striatal DAT Phosphopeptide Mapping

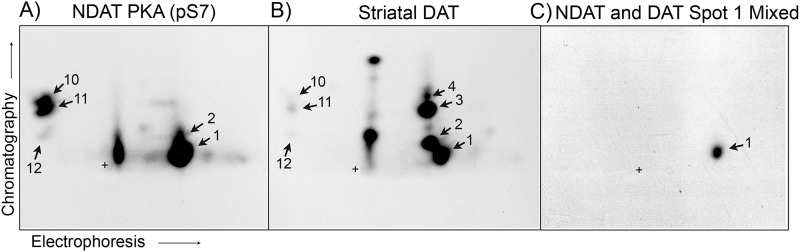

We then used phosphopeptides obtained from PKA- and CaMKII-phosphorylated NDATs as markers in two-dimensional TLC for identification of phosphorylation sites on rat striatal DAT. Phosphorylated DATs were prepared from 32PO4-labeled rat striatal slices treated with the diacylglycerol analog OAG to stimulate PKC-dependent transporter phosphorylation plus the phosphatase inhibitor OA to inhibit transporter dephosphorylation (27). 32P-Labeled NDAT and rat striatal DAT samples were immunoprecipitated, gel-purified, and subjected to proteolysis, two-dimensional TLC, and autoradiography exactly in parallel (Fig. 4). PKA-phosphorylated NDAT displayed characteristic fragments 1 and 2, and in some experiments three additional fragments (numbered 10–12) that presumably arose from less complete digestion than previous samples (Fig. 4A). A matched phosphopeptide map from rat striatal DAT (Fig. 4B) contained three major and several minor fragments that showed strong similarities to NDAT PKA and CaMK phosphopeptides and were numbered 1–4 (and 10–12 when present) based on these similarities. In four independent experiments, alignment of films from DAT and NDAT digests showed essentially complete overlap of major DAT fragments 1 and 2 and minor fragments 10–12, strongly suggesting the identity of these peptides.

FIGURE 4.

Comigration of DAT peptide 1 and NDAT Ser(P)-7 peptide 1. 32P-Labeled PKA-phosphorylated NDAT (A) and rat striatal DAT (B) were immunoprecipitated, gel-purified, and digested with trypsin plus thermolysin, and the resulting fragments were subjected to two-dimensional TLC and autoradiography. C, material in spot 1 from each sample was scraped from the TLC plate and eluted from the cellulose matrix. Equal amounts of radioactivity were mixed together and reanalyzed on a second two-dimensional TLC plate. +, origin.

To further assess the similarity of these DAT and NDAT phosphopeptides, fragment 1 from each sample was collected from the TLC plate by scraping the cellulose backing corresponding to the spot and eluting the radioactivity from the matrix. Samples were subjected to Cerenkov counting, and equal amounts of radioactivity were mixed together and run on a second TLC plate. In three independent experiments, we found that the mixed sample chromatographed as a single discrete spot (Fig. 4C). Because peptides that differ by single amino acids or post-translational modifications can migrate with distinct mobilities in two-dimensional TLC (39), this result provides extremely strong evidence that spot 1 from PKA-phosphorylated NDAT and from metabolically labeled rat striatal DAT contain identical peptides phosphorylated on Ser-7.

Fragment 2 in DAT and NDAT samples also showed strong similarity, suggestive of their identity as peptides phosphorylated on Ser-7; however, we did not perform mixing experiments for these fragments. Peptide 3 from striatal DAT migrated with a clearly distinct mobility from NDAT peptides 1 or 2, suggesting that it represents a distinct phosphopeptide. Migration of DAT peptide 3 was most similar to that of Ser(P)-13-containing peptide 3 from CaMKII-phosphorylated NDAT analyzed in parallel (data not shown), but in mixing experiments the two fragments separated into closely migrating but distinct species. Thus, although we were unable to determine the identity of DAT phosphopeptide 3, its presence and differential mobility from Ser(P)-7 NDAT peptides strongly suggest that PKC-stimulated phosphorylation of striatal DAT occurs on at least two residues.

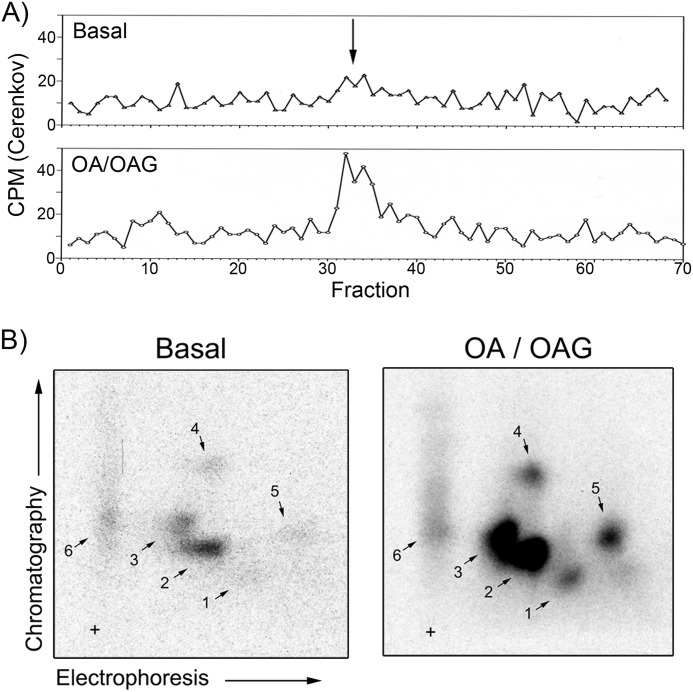

Basal and PKC-induced DAT Phosphorylation Occur on the Same Residues in Neurons

Whereas the preceding experiments were performed using PKC-stimulated DAT samples, we also sought to determine whether basal and stimulated DAT phosphorylation occur on the same or different residues. To address this question, we performed two-dimensional TLC of phosphopeptides obtained from rat striatal DATs prepared under basal and PKC stimulation conditions. 32P-Labeled DATs prepared from rat striatal slices treated with vehicle or OA plus OAG were immunoprecipitated, gel-purified, digested with trypsin, and desalted by C18 reverse phase HPLC. The majority of basal and stimulated Cerenkov radioactivity was found in fractions 31–36 (Fig. 5A, arrow). These fractions were pooled, concentrated, and subjected to two-dimensional TLC and autoradiography (Fig. 5B). Note that because these samples were digested with trypsin alone, the pattern is not directly comparable to that of the striatal sample in Fig. 4.

FIGURE 5.

Phosphopeptide maps of basal and PKC-stimulated rat striatal DAT. 32PO4-Labeled DATs from rat striatal slices given the indicated treatments were immunoprecipitated, gel-purified, and digested with trypsin. A, tryptic digests of DAT were chromatographed on C18 reverse phase HPLC, and fractions were counted by Cerenkov counting. B, fractions 31–36 from each condition were pooled and subjected to two-dimensional TLC and autoradiography. Results are representative of two independent experiments. +, origin.

The digests of basal and stimulated DAT each contained six major phosphopeptides that migrated with essentially identical patterns, with the fragments from treated tissue showing 32P levels that were increased 2.5–4-fold compared with the analogous fragments from the basal sample, as determined by densitometry. The stimulated sample contained no novel fragments compared with the basal sample, and no fragments seen in the basal sample were absent from the stimulated sample. Because stimulated phosphorylation of one or more previously unused sites would result in production of novel phosphopeptides and/or alteration in the charge and thus mobility of fragments compared with the basal state, the similar basal and stimulated phosphopeptide patterns obtained in these experiments strongly indicate that stimulated phosphorylation of striatal DAT occurs on residues that are used under basal conditions. These results thus provide strong evidence that increased phosphorylation of DAT by PKC results from modification of increased numbers of transporters at tonically used sites rather than by de novo phosphorylation of distinct sites.

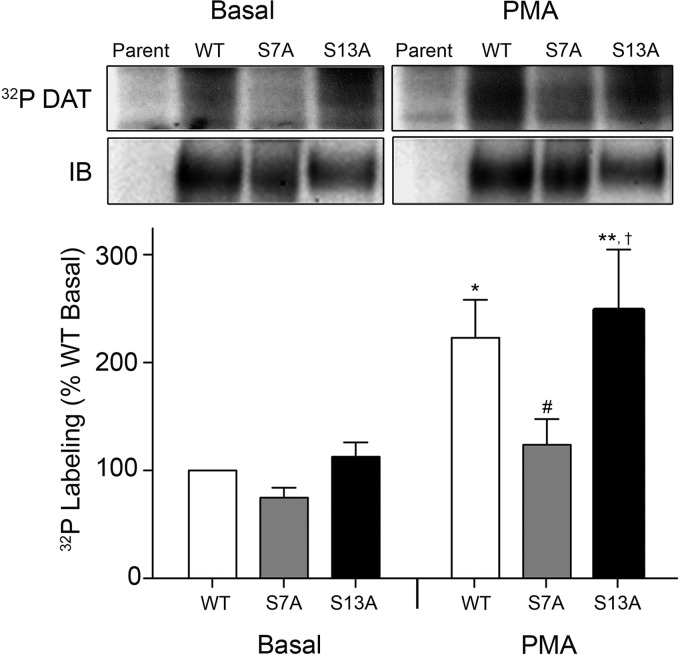

Identification of Ser-7 Phosphorylation in Expressed rDAT by Site-directed Mutagenesis

As a further method to determine whether Ser-7 or Ser-13 was phosphorylated, we generated S7A and S13A rDATs for stable expression in LLC-PK1 cells. Both mutants were expressed as full-length mature proteins, and surface biotinylation analyses showed that the total to surface ratios for S7A and S13A forms were comparable with the WT protein (data not shown), indicating that the mutants were not defective in surface presentation or maturation. For phosphorylation analyses, cells were metabolically labeled with 32PO4 and treated with vehicle or PMA. Because the DAT expression level in each of these cell lines was significantly different, we immunoblotted multiple volumes of each lysate to identify amounts containing equal DAT protein so as to minimize the extent of arithmetical correction needed to normalize phosphorylation intensities to total DAT protein. The selected volumes were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE/autoradiography to determine DAT phosphorylation intensities and were re-blotted to confirm equal DAT levels.

WT DAT showed a basal level of phosphorylation that was stimulated ∼2-fold (223 ± 35% of basal) by PMA (p < 0.05), similar to findings we have previously reported. In six independent experiments, we found that S7A DAT showed a trend toward reduced basal phosphorylation (75 ± 9% of WT basal level), a lack of stimulation by PMA treatment (124 ± 24% of WT basal, p > 0.05), and a significantly reduced level of PMA-stimulated phosphorylation compared with that of the WT DAT (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6), strongly indicating that Ser-7 represents a major site of PKC-dependent phosphorylation on DAT. Conversely, although our two-dimensional TLC findings for striatal DAT were somewhat suggestive of Ser-13 usage, analysis of S13A DAT revealed no consistent reduction of phosphorylation intensity in either basal (113 ± 13% of WT basal level, p > 0.05) or PMA treatment conditions (248 ± 56% of WT basal level) (p > 0.05 relative to WT PMA). Thus, although the significant level of 32P labeling remaining on S7A DAT protein in both basal and stimulated conditions demonstrates the presence of phosphorylation on one or more additional residues, these experiments do not support phosphorylation of Ser-13, and the identity of the other phosphorylated residue(s) remains unknown.

FIGURE 6.

S7A rDAT displays reduced phosphorylation. Upper panel, LLC-PK1 cells not transfected with DAT (parent) or expressing WT, S7A, or S13A DATs were labeled in parallel with 32PO4 for 2 h at 37 °C, followed by application of vehicle or 1 μm PMA for 30 min at 37 °C. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with Ab16 and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography or immunoblotting. Lower panel, histogram showing DAT phosphorylation level normalized for DAT protein, expressed as means ± S.E. of WT basal level set to 100%. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 WT PMA or S13A PMA versus WT basal; †, p < 0.05, S13A PMA versus S13A basal; #, p < 0.05 S7A PMA versus WT PMA or S13A PMA (ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc test). (S7A n = 6, S13A n = 8).

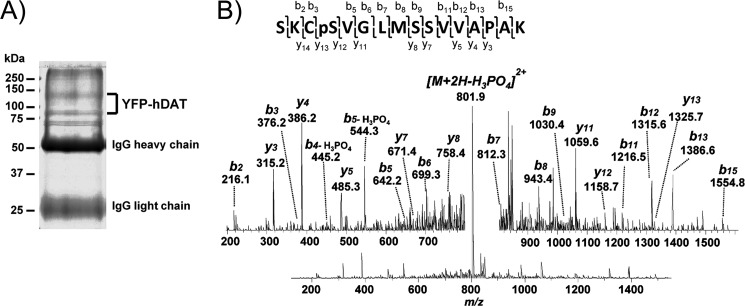

Identification of Ser-7 Phosphorylation in Expressed hDAT by Mass Spectrometry

To determine whether hDAT is also phosphorylated on Ser-7, we immunopurified YFP-hDAT from hDAT-HEK293 cell lysates and size-fractionated purified proteins by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 7A). The indicated Coomassie Blue-stained bands were subjected to trypsin in-gel digestion, and the resulting peptides were subjected to LC-MS/MS. Phosphorylated serine at position 7 was unambiguously and repeatedly identified within the MS/MS spectra of the tryptic peptide spanning amino acids 4–19 (SKCpSVGLMSSVVAPAK) (Fig. 7B). In multiple independent experiments, we identified Ser-7 from cells treated with OA to inhibit transporter dephosphorylation, whereas little Ser(P)-7 was seen without this treatment, similar to findings of robust OA-stimulated phosphorylation obtained with rDAT. Together with mutagenesis findings, these results confirm the use of Ser-7 as a site for basal and PKC/OA-stimulated phosphorylation of heterologously expressed rat and human DAT.

FIGURE 7.

Mass spectrometry of hDAT Ser-7 phosphorylation. HEK293-YFP-hDAT cells were treated with 0.25 μm OA followed by detergent lysis and immunopurification of DAT. A, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel showing position of YFP-hDAT. Molecular mass markers are indicated on left. B, MS/MS spectrum obtained from doubly charged tryptic peptide at m/z 850.94 described the sequence SKCpSVGLMSSVVAPAK (amino acids 4–19) in hDAT.

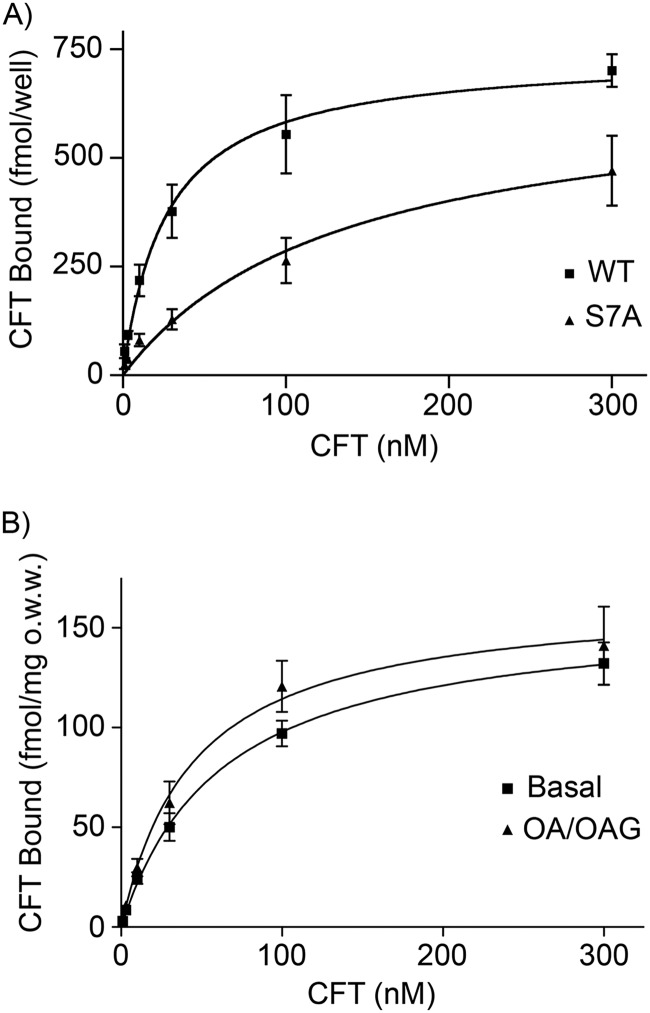

CFT Affinity Is Reduced by Mutation of Ser-7 and Increased by DAT Phosphorylation Conditions

We next examined mutations of Ser-7 and several other N-terminal residues (listed in Table 1) for impacts on various DAT functions. All transporters analyzed showed expression of mature protein by immunoblotting, were active for [3H]DA transport, and displayed PMA-stimulated down-regulation (data not shown), indicating no major defects in surface presentation, transport activity, or regulation. Unexpectedly, however, we found that S7A DAT showed significantly reduced binding affinity for the cocaine analog [3H]CFT (Kd 134 ± 60 nm) compared with the WT protein (Kd 32 ± 8 nm) (p < 0.01) (Fig. 8A and Table 1), indicating that Ser-7 and/or its phosphorylation state function to promote high affinity CFT binding. Binding for both forms showed better fit to one-site versus two-site models. Significant reductions in CFT affinity were also observed with the phosphomimetic substitution of Ser-7 to aspartic acid (S7D), and with the S4A and C6A mutations (Table 1), further supporting a role for Ser-7 and suggesting that nearby residues also participate in promotion of binding affinity or that their mutations impact Ser-7 function. CFT affinity was not altered for S2A, S13A, or T53A DATs, demonstrating a degree of specificity for residues near Ser-7 for this effect. Interestingly, Δ21 DAT, a truncation mutant lacking the first 21 N-terminal residues, showed no reduction of CFT affinity, suggesting that Ser-4, Cys-6, and Ser-7 are not required per se for maintenance of high CFT affinity, but rather they modulate this property in conjunction with other residues within this domain. Bmax of CFT binding was not changed for S2A, C6A, or S7A DATs, but it was reduced up to 2-fold in other mutants (Table 1), possibly due to expression level differences.

TABLE 1.

[3H]CFT binding characteristics of WT and mutant rDATs

Results shown are means ± S.E. from three or more experiments.

| rDAT form | Bmax | Kd |

|---|---|---|

| fmol/well | nm | |

| WT | 681 ± 52 | 32 ± 8 |

| S2A | 945 ± 334 | 33 ± 40 |

| S13A | 336 ± 30a | 30 ± 9 |

| T53A | 348 ± 63b | 73 ± 37 |

| Δ21 | 255 ± 62a | 72 ± 32 |

| S4A | 247 ± 75a | 190 ± 37c |

| C6A | 551 ± 296 | 191 ± 57a |

| S7A | 670 ± 130 | 134 ± 60a |

| S7D | 372 ± 175b | 232 ± 108b |

a p < 0.01, relative to WT values by Student's t test.

b p < 0.05, relative to WT values by Student's t test.

c p < 0.001, relative to WT values by Student's t test.

FIGURE 8.

Phosphorylation conditions regulate DAT affinity for CFT. A, [3H]CFT saturation analysis of LLC-PK1 cells stably expressing WT or S7A rDAT. Values shown are means ± S.E. of results from four independent experiments. B, [3H]CFT saturation analysis of membranes from rat striatal slices treated with vehicle or OA/OAG. Values shown are means ± S.E. of results from three independent experiments. Bmax and KD values were determined by nonlinear regression analysis using Prism 3 software, and data were analyzed using Student's t test.

Because these results were compatible with a role for a demonstrated phosphorylation site in regulating CFT affinity, we then tested the ability of phosphorylation conditions to modulate CFT binding. Similar to some previous reports from heterologous cell systems (40, 41), we found that treatment of rDAT LLC-PK1 cells with PMA caused no change in CFT affinity (control Kd, 77 ± 18 nm; PMA Kd, 81 ± 21 nm; p > 0.05) or Bmax (control, 804 ± 74 fmol/well; PMA, 732 ± 79 fmol/well; p > 0.05). However, treatment of rat striatal slices with OA/OAG, which induces the strongest known stimulation of DAT phosphorylation (27), resulted in a modest but statistically significant increase in CFT binding affinity (Kd 45 ± 12 nm) relative to binding obtained from tissue treated with vehicle (Kd 63 ± 11 nm) (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8B). No change in binding Bmax was observed (OA/OAG, 166 ± 14 fmol/mg original wet weight; basal, 159 ± 9 fmol/mg original wet weight; p > 0.05), and binding in both conditions was better fit to one-site versus two-site models. The findings that Ser-7 is phosphorylated in both rat striatal tissue and heterologous cells, that phosphorylation conditions increase CFT affinity in rat striatal tissue, and that mutations preventing Ser-7 phosphorylation reduce CFT affinity strongly support phosphorylation of Ser-7 as the mechanism producing these results.

Mutation of Ser-7 Affects Zinc Regulation of DAT Conformational Equilibrium

The binding of CFT to DAT is presumed to reflect the conformational equilibrium of the protein, with the ligand preferentially binding to outwardly facing forms (4, 42–44). The findings that CFT affinity is decreased by mutation of Ser-7 and nearby residues but increased by DAT phosphorylation conditions thus suggest that the distal N terminus exerts a phosphorylation-dependent role over the DAT conformational equilibrium that impacts CFT binding. To further explore this possibility, we examined the effect of Ser-7 mutations on Zn2+ modulation of CFT binding, as Zn2+ binding to DAT leads to dose-dependent augmentation of CFT binding that is thought to reflect stabilization of outwardly facing transporter forms (45, 46).

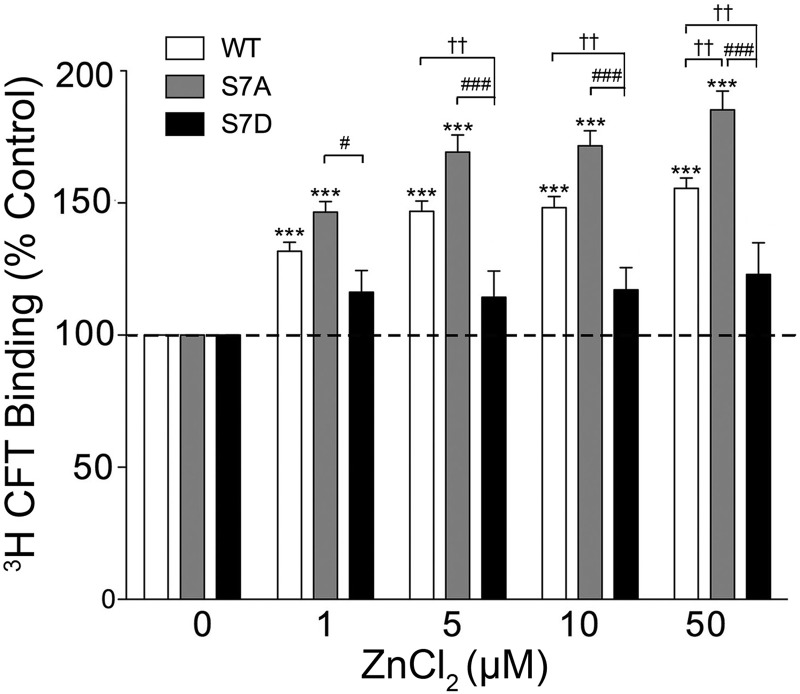

For these experiments, LLC-PK1 cells expressing WT, S7A, or S7D rDAT were treated with 1–50 μm Zn2+ and assayed for [3H]CFT binding (Fig. 9). In WT DAT, binding was increased by 1–50 μm Zn2+ (p < 0.001 relative to control at all doses), reaching a final level of 156 ± 4% of control at 50 μm Zn2+, comparable with previous findings (46). S7A DAT also showed increased [3H]CFT binding with Zn2+ treatment (p < 0.001 relative to control at all doses), with increases trending toward higher levels than the WT protein at 1, 5, and 10 μm Zn2+ and reaching a statistically greater level than WT DAT (185 ± 7% of control value) at 50 μm Zn2+ (p < 0.01). In contrast, [3H]CFT binding to S7D DAT was not statistically increased at any Zn2+ concentration (all doses p > 0.05) and was significantly different from WT DAT at 5, 10, and 50 μm Zn2+ (p < 0.01) and from S7A DAT at all Zn2+ concentrations (p < 0.001) (Fig. 9). These results further support a role for Ser-7 in regulating CFT binding to DAT, with the opposing directions of S7A and S7D effects supporting a functionality of Ser-7 phosphorylation indictating inward and outward conformational equilibria.

FIGURE 9.

Ser-7 mutation of DAT affects zinc regulation of CFT binding. WT, S7A, or S7D rDAT LLC-PK1 cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of ZnCl2 followed by [3H]CFT binding. The histogram shows [3H]CFT binding expressed as means ± S.E. of controls set to 100% for each DAT form. ***, p < 0.001 WT or S7A relative to control; ††, p < 0.01 S7A or S7D versus WT within the indicated ZnCl2 dose; #, p < 0.05; ###, p < 0.001 S7D versus S7A within the indicated ZnCl2 dose (ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test, n = 16).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identify Ser-7 as a PKC phosphorylation site on both rat and human DAT, and obtain evidence for a previously unsuspected role for the N-terminal domain and its phosphorylation state in regulating cocaine analog binding. Although the distal end of the N-terminal tail has been well characterized as the major PKC phosphorylation domain on DAT (20, 24, 27), the large number, close spacing, and modification of multiple residues in this region have hampered identification of specific phosphorylation sites. Our findings now support basal and PKC-stimulated phosphorylation of Ser-7 in both striatal tissue and model cells, as well as demonstrating that significant levels of phosphorylation occur on additional residues that remain currently unknown. Importantly, the identification of Ser(P)-7 in both human and rat transporters indicates the conservation of regulatory functions via this site, supporting the appropriateness of rat models for analyses of phosphorylation-dependent functions. We also found no evidence in these studies for phosphorylation of residues not used basally, indicating that functional regulation of DAT by PKC-dependent phosphorylation is achieved by modification of increased numbers of transporters at sites used under basal conditions.

Although DAT phosphorylation has been investigated primarily for its potential role in PKC-dependent transport of down-regulation and AMPH-stimulated efflux (6, 14, 15, 23, 24, 26, 47), our findings that CFT affinity is decreased by Ser-7 mutations and increased by conditions that stimulate Ser-7 phosphorylation now adds cocaine binding to this list of functions. Other residues near Ser-7 may also participate in this activity, and full investigation of the remaining residues in this region is warranted. Regulation of CFT affinity by PKC-linked inputs thus suggests a mechanism that could potentially impact cocaine binding in vivo and underlie individual responsiveness to cocaine.

Our current understanding of the DAT structure indicates that the protein transitions between outwardly facing, occluded, and inwardly facing forms as substrate is transported, with the empty protein returning to the outwardly facing form. Cocaine and its analogs are thought to bind preferentially to outwardly facing conformations within a pocket near the substrate-active site generated by residues in TM1, -3, -6, and -8 (42, 48, 49). Based on this model, the CFT affinity reductions induced by Ser-7 mutagenesis and CFT affinity increases induced by phosphorylation could be explained by alterations in DAT conformational equilibria that stabilize inwardly or outwardly facing forms. The finding that both S7A and S7D DATs show reduced affinity relative to WT and phosphorylated transporters indicates that although the putative phosphomimetic S7D mutation alters DAT conformation, it does not impart genuine phosphorylation functionality for this activity. In addition, the interpretation that phosphorylation promotes an outwardly facing equilibrium is opposite the current paradigm that postulates promotion of inward conformations by phosphorylation to explain the stimulation of DA efflux by PKC and AMPH (6, 21, 50–52), and further work will be necessary to clarify this issue.

Although mutation of several human DAT residues, including Thr-62, Trp-84, Lys-264, Asp-313, Tyr-335, Asp-345, and Asp-436, leads to altered CFT affinity attributed to promotion of outwardly or inwardly facing transporter conformations (43, 50, 53, 54), these residues are located in active site helices and adjacent loops, such that their mutations stabilize intermediate transporter conformations by interfering with TM mobility. Our data now demonstrate that cytoplasmic N-terminal residues that are separated from the active site by both protein and lipid bilayer structure can also impact the binding pocket, and importantly, they demonstrate the potential for these effects to be regulated physiologically via Ser-7 phosphorylation. Because our binding studies were performed in membranes and in cells held on ice, conditions in which enzyme activities are suppressed and DAT cannot traffic, these results provide strong evidence that DAT kinetic characteristics can be directly impacted by N-terminal phosphorylation.

Additional support for the idea that phosphorylation impacts DAT conformational equilibrium was obtained by our demonstration that Ser-7 mutations induced pronounced effects on Zn2+ regulation of CFT binding. Zn2+ stimulation of CFT binding to DAT is believed to occur by stabilization of outwardly facing transporter conformations (45, 46). If the reduced CFT affinity of S7A DAT occurs via promotion of more inwardly facing equilibria relative to the WT protein, its increased stimulation of CFT binding relative to WT DAT by Zn2+ could be consistent with a larger fraction of proteins undergoing inward-to-outward reorientation. The reduced CFT affinity of S7D DAT is also consistent with the mutant possessing a more inwardly facing equilibrium relative to the WT protein. However, lack of S7D DAT responsiveness to Zn2+ indicates that this mutation produces a more pronounced effect than S7A mutation on transporter conformation that cannot be overcome with Zn2+. Although additional studies will be necessary to fully understand the mechanisms underlying the effects of these mutations, the findings nevertheless demonstrate a clear effect of negative charge introduction at Ser-7, further supporting a phosphorylation-related role for this residue in regulating the transporter active site.

Although Ser-7 impacts on conformational equilibria might be expected to affect substrate transport characteristics, we did not see Km alterations for S7A DAT (S7A 2.9 ± 0.5 μm, WT 3.4 ± 0.6 μm, p > 0.05) or for WT DATs under PKC conditions (26, 55). It is possible that the transporter does not reside in specific substrate-bound states for a sufficient duration to allow such alterations to be detected with [3H]DA transport assays, and higher resolution approaches may be useful for testing this. We did note that the degree of affinity change induced by phosphorylation conditions in rat striatum (30% increase) was less than for Ser-7 mutation (4-fold reduction), and we hypothesize that these differences reflect the stoichiometry of modification, which is 100% for mutation but likely to be considerably lower for phosphorylation. Our finding that PMA treatment of rDAT-LLCPK1 cells did not produce the CFT affinity increases observed in striatal tissue suggests the presence of mechanistic differences between these systems, potentially including DAT phosphorylation characteristics (sites, stoichiometry, and dynamic range), binding partner interactions, or membrane lipid/membrane raft properties (56), and cell lines with more neuronal characteristics may provide superior model systems for clarifying these issues.

The mechanism by which the DAT distal N terminus could affect transporter conformational equilibrium is not known, as the three-dimensional structure of this domain and its orientation relative to the intracellular loops have not been determined. One possibility is that the distal N terminus is positioned in close proximity to intracellular loops where it could impact molecular interactions that occur during the transport cycle. For example, residues Arg-60, Ser-334, Tyr-335, and Asp-436 in the proximal N-terminal tail and internal loops 3 and 4 interact through ionic and hydrogen bonds to stabilize the intracellular gate and promote outwardly facing transporter conformations (50, 57). It is possible that hydrogen bonds from Ser-4, Cys-6, and Ser-7 side groups and/or negative charges from Ser phosphoryl moieties interact with these residues to modulate gate closure and impact transporter equilibrium. Consistent with this idea, recent structural studies on the homologous bacterial transporter LeuT support the generation of an inwardly facing conformation upon transport-induced breakage of the analogous Arg-Asp intracellular gate salt bridge (58). Alternatively, the distal N terminus could potentially regulate binding and/or conformational equilibrium by other mechanisms such as impacting the orientation of TM1, which contains residues crucial for cocaine binding (49), or by regulating interactions with DAT binding partners. For example, syn 1A, which regulates DAT transport, efflux, and channel activity (11–13), interacts with DAT via the distal N terminus (12) and regulates the transporter phosphorylation level (11). The ability of syn 1A to concomitantly affect DAT phosphorylation and uptake capacity suggests its potential to mechanistically link phosphorylation signals to transport kinetic steps. Other DAT N-terminal binding proteins related to phosphorylation such as the receptor for activated C kinase-1 (59) could also represent potential integrators of transporter conformation and phosphorylation.

With respect to the issue of direct versus indirect kinase actions on DAT, we previously identified many striking similarities between metabolic phosphorylation of DAT and in vitro phosphorylation of NDAT by both PKC and proline-directed kinases (28, 29), supporting NDAT as a good model for elucidating DAT phosphorylation characteristics. In this study, we further elucidate multiple NDAT and DAT similarities related to PKC, including the bulk of phosphorylation occurring in the distal N-terminal Ser cluster, phosphorylation occurring on multiple sites within the Ser cluster, and phosphorylation occurring specifically at Ser-7. In conjunction with the presence of Ser-7 in a canonical PKC motif (RXS) (Fig. 1A), these findings strongly support the ability of PKC to directly phosphorylate Ser-7 in vivo and indicate this as a mechanism underlying one or more PKC-dependent responses of DAT.

Although direct demonstration of DAT phosphorylation by PKA and CaMKII has not been shown, DAT is regulated by both of these enzymes (60–63), and the robust phosphorylation of NDAT by these kinases supports their potential to phosphorylate DAT. If this occurs, the phosphorylation of NDAT Ser-7 by both PKA and PKC suggests the possibility for this residue to serve as a site for integration of signals from these pathways for regulation of cocaine binding and/or other properties. Similarly, because AMPH-induced DA efflux has been linked to both CaMKII and PKC (21, 64), the phosphorylation of NDAT Ser-13 by these kinases strongly implicates this residue as a mechanistic locus for efflux and a site for integration for CaMKII and PKC signals. Although we found no reduction of S13A DAT phosphorylation during our 32P labeling analyses, the conditions used were focused on PKC activation, and it is possible that examination of CaMKII conditions may be more relevant for characterization of this residue as a phosphorylation site.

Numerous studies have now identified the DAT cytoplasmic N terminus as a major regulatory domain for various transporter functions. Our demonstration of differential phosphorylation of the N terminus by PKC and proline-directed kinases (28, 29) establishes the capacity for distinct kinases to exert effects on DAT and provides a mechanism for integration of signals from multiple pathways. The DAT N terminus thus represents a major target for regulatory enzymes that impact multiple transporter properties, and further analysis of this region and its complex regulation may provide targets for therapeutic manipulation of transporter function in disease states.

Acknowledgments

We thank Steven Adkins and Qiao Han for excellent technical assistance and Drs. Gert Lubec and Wei-Qiang Chen for generous support with mass spectrometry. The University of North Dakota was recipient of National Institutes of Health COBRE Program Grant P20 RR017699 from NCRR.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DA13147 (to R. A. V.) and P20 RR01769 (to U. N. D.), Predoctoral Fellowship MH067472 (to M. S. M.-R.), and Grant DA07390 (to R. D. B.). This work was also supported by North Dakota EPSCoR IIG (to R. A. V. and J. D. F.), North Dakota EPSCOR Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship (to B. K. G.), and the Austrian Science Fund SFB3506 (to H. H. S.) and P23670-B09 (to J. W. Y.)

- DA

- dopamine

- DAT

- dopamine transporter

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- OAG

- oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol

- OA

- okadaic acid

- METH

- methamphetamine

- AMPH

- amphetamine

- CaMKII

- Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- NDAT

- recombinant DAT N-terminal tail protein

- hDAT

- human DAT

- rDAT

- rat DAT

- β-CFT

- (−)-2-β-carbomethoxy-3-β-(4-fluorophenyl) tropane)

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- TM

- transmembrane

- hDAT

- human DAT.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jayanthi L. D., Ramamoorthy S. (2005) Regulation of monoamine transporters: influence of psychostimulants and therapeutic antidepressants. AAPS J. 7, E728–E738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amara S. G., Kuhar M. J. (1993) Neurotransmitter transporters. Recent progress. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 73–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Forrest L. R., Rudnick G. (2009) The rocking bundle. A mechanism for ion-coupled solute flux by symmetrical transporters. Physiology 24, 377–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Loland C. J., Desai R. I., Zou M. F., Cao J., Grundt P., Gerstbrein K., Sitte H. H., Newman A. H., Katz J. L., Gether U. (2008) Relationship between conformational changes in the dopamine transporter and cocaine-like subjective effects of uptake inhibitors. Mol. Pharmacol. 73, 813–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khoshbouei H., Wang H., Lechleiter J. D., Javitch J. A., Galli A. (2003) Amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux. A voltage-sensitive and intracellular Na+-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 12070–12077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khoshbouei H., Sen N., Guptaroy B., Johnson L., Lund D., Gnegy M. E., Galli A., Javitch J. A. (2004) N-terminal phosphorylation of the dopamine transporter is required for amphetamine-induced efflux. PLoS Biol. 2, E78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goodwin J. S., Larson G. A., Swant J., Sen N., Javitch J. A., Zahniser N. R., De Felice L. J., Khoshbouei H. (2009) Amphetamine and methamphetamine differentially affect dopamine transporters in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 2978–2989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robertson S. D., Matthies H. J., Galli A. (2009) A closer look at amphetamine-induced reverse transport and trafficking of the dopamine and norepinephrine transporters. Mol. Neurobiol. 39, 73–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gnegy M. E. (2003) The effect of phosphorylation on amphetamine-mediated outward transport. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 479, 83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sitte H. H., Huck S., Reither H., Boehm S., Singer E. A., Pifl C. (1998) Carrier-mediated release, transport rates, and charge transfer induced by amphetamine, tyramine, and dopamine in mammalian cells transfected with the human dopamine transporter. J. Neurochem. 71, 1289–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cervinski M. A., Foster J. D., Vaughan R. A. (2010) Syntaxin 1A regulates dopamine transporter activity, phosphorylation and surface expression. Neuroscience 170, 408–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Binda F., Dipace C., Bowton E., Robertson S. D., Lute B. J., Fog J. U., Zhang M., Sen N., Colbran R. J., Gnegy M. E., Gether U., Javitch J. A., Erreger K., Galli A. (2008) Syntaxin 1A interaction with the dopamine transporter promotes amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux. Mol. Pharmacol. 74, 1101–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carvelli L., Blakely R. D., DeFelice L. J. (2008) Dopamine transporter/syntaxin 1A interactions regulate transporter channel activity and dopaminergic synaptic transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14192–14197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Foster J. D., Cervinski M. A., Gorentla B. K., Vaughan R. A. (2006) Regulation of the dopamine transporter by phosphorylation. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 175, 197–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ramamoorthy S., Shippenberg T. S., Jayanthi L. D. (2011) Regulation of monoamine transporters. Role of transporter phosphorylation. Pharmacol. Ther. 129, 220–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miller G. W., Gainetdinov R. R., Levey A. I., Caron M. G. (1999) Dopamine transporters and neuronal injury. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 20, 424–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kahlig K. M., Galli A. (2003) Regulation of dopamine transporter function and plasma membrane expression by dopamine, amphetamine, and cocaine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 479, 153–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vaughan R. A. (2004) Phosphorylation and regulation of psychostimulant-sensitive neurotransmitter transporters. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 310, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schmitt K. C., Reith M. E. (2010) Regulation of the dopamine transporter: aspects relevant to psychostimulant drugs of abuse. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1187, 316–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cervinski M. A., Foster J. D., Vaughan R. A. (2005) Psychoactive substrates stimulate dopamine transporter phosphorylation and down-regulation by cocaine-sensitive and protein kinase C-dependent mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 40442–40449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fog J. U., Khoshbouei H., Holy M., Owens W. A., Vaegter C. B., Sen N., Nikandrova Y., Bowton E., McMahon D. G., Colbran R. J., Daws L. C., Sitte H. H., Javitch J. A., Galli A., Gether U. (2006) Calmodulin kinase II interacts with the dopamine transporter C terminus to regulate amphetamine-induced reverse transport. Neuron 51, 417–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Steinkellner T., Yang J. W., Montgomery T. R., Chen W. Q., Winkler M. T., Sucic S., Lubec G., Freissmuth M., Elgersma Y., Sitte H. H., Kudlacek O. (2012) αCaMKII controls the activity of the dopamine transporter: implications for Angelman syndrome. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 29627–29635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chang M. Y., Lee S. H., Kim J. H., Lee K. H., Kim Y. S., Son H., Lee Y. S. (2001) Protein kinase C-mediated functional regulation of dopamine transporter is not achieved by direct phosphorylation of the dopamine transporter protein. J. Neurochem. 77, 754–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Granas C., Ferrer J., Loland C. J., Javitch J. A., Gether U. (2003) N-terminal truncation of the dopamine transporter abolishes phorbol ester- and substance P receptor-stimulated phosphorylation without impairing transporter internalization. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4990–5000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Foster J. D., Zhen J., Reith M. E., Zhang M., Gnegy M. E., Mazei-Robinson M. S., Blakely R. D., Vaughan R. A. (2010) Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner, Society for Neuroscience Program No. 546.8, San Diego [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vaughan R. A., Huff R. A., Uhl G. R., Kuhar M. J. (1997) Protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation and functional regulation of dopamine transporters in striatal synaptosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 15541–15546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Foster J. D., Pananusorn B., Vaughan R. A. (2002) Dopamine transporters are phosphorylated on N-terminal serines in rat striatum. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25178–25186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gorentla B. K., Moritz A. E., Foster J. D., Vaughan R. A. (2009) Proline-directed phosphorylation of the dopamine transporter N-terminal domain. Biochemistry 48, 1067–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Foster J. D., Yang J. W., Moritz A. E., Challasivakanaka S., Smith M. A., Holy M., Wilebski K., Sitte H. H., Vaughan R. A. (2012) Dopamine transporter phosphorylation site threonine 53 regulates substrate reuptake and amphetamine-stimulated efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 29702–29712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Foster J. D., Blakely R. D., Vaughan R. A. (2003) Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner, Society for Neuroscience Program No. 167.12, Washington, D. C [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gaffaney J. D., Vaughan R. A. (2004) Uptake inhibitors but not substrates induce protease resistance in extracellular loop two of the dopamine transporter. Mol. Pharmacol. 65, 692–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pear W. S., Nolan G. P., Scott M. L., Baltimore D. (1993) Production of high-titer helper-free retroviruses by transient transfection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 8392–8396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vaughan R. A., Kuhar M. J. (1996) Dopamine transporter ligand binding domains. Structural and functional properties revealed by limited proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21672–21680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Boyle W. J., van der Geer P., Hunter T. (1991) Phosphopeptide mapping and phosphoamino acid analysis by two-dimensional separation on thin-layer cellulose plates. Methods Enzymol. 201, 110–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Egaña L. A., Cuevas R. A., Baust T. B., Parra L. A., Leak R. K., Hochendoner S., Peña K., Quiroz M., Hong W. C., Dorostkar M. M., Janz R., Sitte H. H., Torres G. E. (2009) Physical and functional interaction between the dopamine transporter and the synaptic vesicle protein synaptogyrin-3. J. Neurosci. 29, 4592–4604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schmid J. A., Scholze P., Kudlacek O., Freissmuth M., Singer E. A., Sitte H. H. (2001) Oligomerization of the human serotonin transporter and of the rat GABA transporter 1 visualized by fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy in living cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 3805–3810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yang J. W., Vacher H., Park K. S., Clark E., Trimmer J. S. (2007) Trafficking-dependent phosphorylation of Kv1.2 regulates voltage-gated potassium channel cell surface expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 20055–20060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zheng J. F., Patil S. S., Chen W. Q., An W., He J. Q., Höger H., Lubec G. (2009) Hippocampal protein levels related to spatial memory are different in the Barnes maze and in the multiple T-maze. J. Proteome Res. 8, 4479–4486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meisenhelder J., Hunter T., van der Geer P. (2001) Phosphopeptide mapping and identification of phosphorylation sites. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. Chapter 13, Unit 13.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kitayama S., Dohi T., Uhl G. R. (1994) Phorbol esters alter functions of the expressed dopamine transporter. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 268, 115–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang L., Coffey L. L., Reith M. E. (1997) Regulation of the functional activity of the human dopamine transporter by protein kinase C. Biochem. Pharmacol. 53, 677–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen N., Justice J. B., Jr. (1998) Cocaine acts as an apparent competitive inhibitor at the outward-facing conformation of the human norepinephrine transporter. Kinetic analysis of inward and outward transport. J. Neurosci. 18, 10257–10268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Loland C. J., Norregaard L., Litman T., Gether U. (2002) Generation of an activating Zn2+ switch in the dopamine transporter. Mutation of an intracellular tyrosine constitutively alters the conformational equilibrium of the transport cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 1683–1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hong W. C., Amara S. G. (2010) Membrane cholesterol modulates the outward facing conformation of the dopamine transporter and alters cocaine binding. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 32616–32626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Richfield E. K. (1993) Zinc modulation of drug binding, cocaine affinity states, and dopamine uptake on the dopamine uptake complex. Mol. Pharmacol. 43, 100–108 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Norregaard L., Frederiksen D., Nielsen E. O., Gether U. (1998) Delineation of an endogenous zinc-binding site in the human dopamine transporter. EMBO J. 17, 4266–4273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sitte H. H., Freissmuth M. (2010) The reverse operation of Na+/Cl−-coupled neurotransmitter transporters–why amphetamines take two to tango. J. Neurochem. 112, 340–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yamashita A., Singh S. K., Kawate T., Jin Y., Gouaux E. (2005) Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of Na+/Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporters. Nature 437, 215–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Beuming T., Kniazeff J., Bergmann M. L., Shi L., Gracia L., Raniszewska K., Newman A. H., Javitch J. A., Weinstein H., Gether U., Loland C. J. (2008) The binding sites for cocaine and dopamine in the dopamine transporter overlap. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 780–789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guptaroy B., Zhang M., Bowton E., Binda F., Shi L., Weinstein H., Galli A., Javitch J. A., Neubig R. R., Gnegy M. E. (2009) A juxtamembrane mutation in the N terminus of the dopamine transporter induces preference for an inward-facing conformation. Mol. Pharmacol. 75, 514–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Guptaroy B., Fraser R., Desai A., Zhang M., Gnegy M. E. (2011) Site-directed mutations near transmembrane domain 1 alter conformation and function of norepinephrine and dopamine transporters. Mol. Pharmacol. 79, 520–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sucic S., Dallinger S., Zdrazil B., Weissensteiner R., Jørgensen T. N., Holy M., Kudlacek O., Seidel S., Cha J. H., Gether U., Newman A. H., Ecker G. F., Freissmuth M., Sitte H. H. (2010) The N terminus of monoamine transporters is a lever required for the action of amphetamines. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 10924–10938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen N., Zhen J., Reith M. E. (2004) Mutation of Trp-84 and Asp-313 of the dopamine transporter reveals similar mode of binding interaction for GBR12909 and benztropine as opposed to cocaine. J. Neurochem. 89, 853–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chen N., Rickey J., Berfield J. L., Reith M. E. (2004) Aspartate 345 of the dopamine transporter is critical for conformational changes in substrate translocation and cocaine binding. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5508–5519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Huff R. A., Vaughan R. A., Kuhar M. J., Uhl G. R. (1997) Phorbol esters increase dopamine transporter phosphorylation and decrease transport Vmax. J. Neurochem. 68, 225–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Foster J. D., Adkins S. D., Lever J. R., Vaughan R. A. (2008) Phorbol ester induced trafficking-independent regulation and enhanced phosphorylation of the dopamine transporter associated with membrane rafts and cholesterol. J. Neurochem. 105, 1683–1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kniazeff J., Shi L., Loland C. J., Javitch J. A., Weinstein H., Gether U. (2008) An intracellular interaction network regulates conformational transitions in the dopamine transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17691–17701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Krishnamurthy H., Gouaux E. (2012) X-ray structures of LeuT in substrate-free outward-open and apo inward-open states. Nature 481, 469–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lee K. H., Kim M. Y., Kim D. H., Lee Y. S. (2004) Syntaxin 1A and receptor for activated C kinase interact with the N-terminal region of human dopamine transporter. Neurochem. Res. 29, 1405–1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Page G., Barc-Pain S., Pontcharraud R., Cante A., Piriou A., Barrier L. (2004) The up-regulation of the striatal dopamine transporter's activity by cAMP is PKA-, CaMK II-, and phosphatase-dependent. Neurochem. Int. 45, 627–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Park Y. H., Kantor L., Guptaroy B., Zhang M., Wang K. K., Gnegy M. E. (2003) Repeated amphetamine treatment induces neurite outgrowth and enhanced amphetamine-stimulated dopamine release in rat pheochromocytoma cells (PC12 cells) via a protein kinase C- and mitogen activated protein kinase-dependent mechanism. J. Neurochem. 87, 1546–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pristupa Z. B., McConkey F., Liu F., Man H. Y., Lee F. J., Wang Y. T., Niznik H. B. (1998) Protein kinase-mediated bidirectional trafficking and functional regulation of the human dopamine transporter. Synapse 30, 79–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Batchelor M., Schenk J. O. (1998) Protein kinase A activity may kinetically up-regulate the striatal transporter for dopamine. J. Neurosci. 18, 10304–10309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Johnson L. A., Guptaroy B., Lund D., Shamban S., Gnegy M. E. (2005) Regulation of amphetamine-stimulated dopamine efflux by protein kinase Cβ. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10914–10919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]