Background: MicroRNA biogenesis is a multistep process regulated by RNA-binding proteins.

Results: Sjögren syndrome antigen B (SSB)/La binds stem-loop precursor microRNAs (pre-miRNA) and is required for microRNA expression.

Conclusion: La/SSB promotes global microRNA expression by stabilizing pre-miRNAs from nuclease-mediated decay.

Significance: This study reveals a novel concept of pre-miRNA holding complex that protects and escorts pre-miRNAs in microRNA biogenesis pathway.

Keywords: Autoimmune Diseases, Dicer, MicroRNA, RNA Processing, RNA-binding Proteins, Autoantigen La/SSB, MCPIP1, Pre-miRNA, Stem-Loop Recognition

Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNA) control numerous physiological and pathological processes. Typically, the primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) transcripts are processed by nuclear Drosha complex into ∼70-nucleotide stem-loop precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNA), which are further cleaved by cytoplasmic Dicer complex into ∼21-nucleotide mature miRNAs. However, it is unclear how nascent pre-miRNAs are protected from ribonucleases, such as MCPIP1, that degrade pre-miRNAs to abort miRNA production. Here, we identify Sjögren syndrome antigen B (SSB)/La as a pre-miRNA-binding protein that regulates miRNA processing in vitro. All three RNA-binding motifs (LAM, RRM1, and RRM2) of La/SSB are required for efficient pre-miRNA binding. Intriguingly, La/SSB recognizes the characteristic stem-loop structure of pre-miRNAs, of which the majority lack a 3′ UUU terminus. Moreover, La/SSB associates with endogenous pri-/pre-miRNAs and promotes miRNA biogenesis by stabilizing pre-miRNAs from nuclease (e.g. MCPIP1)-mediated decay in mammalian cells. Accordingly, we observed positive correlations between the expression status of La/SSB and Dicer in human cancer transcriptome and prognosis. These studies identify an important function of La/SSB as a global regulator of miRNA expression, and implicate stem-loop recognition as a major mechanism that mediates association between La/SSB and diverse RNA molecules.

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs)3 are ∼21-nucleotide (nt) cellular RNAs that govern numerous biological and disease processes by directing degradation and translational repression of cognate mRNAs (1–3). It is estimated that human genome encodes up to one thousand miRNAs (1, 3, 4), which are transcribed either as independent genes, or imbedded in other genes. The majority of miRNAs are generated by sequential processing by two RNase III enzymes: Drosha and Dicer. In the nucleus, the primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) transcripts are processed by the Drosha·DGCR8/Pasha complex into ∼70-nt stem-loop precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) (5–8). The pre-miRNAs are exported by Exportin 5·Ran:GTP to the cytoplasm (9, 10), and are further cleaved into mature miRNAs by the Dicer-1·Loqs-PB complex in Drosophila melanogaster (11–13), or by the Dicer·TRBP complex in mammals (14–17). Both DGCR8/Pasha or TRBP/Loqs-PB are dsRNA-binding proteins that promote miRNA processing by stabilizing Drosha and Dicer and by facilitating their interaction with pri-miRNAs and pre-miRNAs, respectively (18–20). A number of post-transcriptional regulators of miRNA biogenesis have recently been characterized, including Lin28, KSRP, hnRNP A1, and SMAD (21–27). All of these miRNA regulators modulate the production of a small subset of miRNAs through recognition of specific sequences of pri- and/or pre-miRNAs (22, 23, 28).

In many RNA maturation processes, the precursor molecules are often bound by RNA-binding proteins or chaperones to protect them from nuclease-mediated decay and to ensure the correct processing by specific ribonucleases. In the current model, however, newly synthesized pri-/pre-miRNAs are described as unprotected and delivered directly to Drosha or Dicer enzymes for processing. It has recently been suggested that the processing of pri-miRNAs by Drosha occurs co-transcriptionally on chromatin (29, 30). In contrast, nascent pre-miRNAs embark a long and perilous journey from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, in which they are vulnerable to degradation by many nucleases. For example, the monocyte chemotactic protein-induced protein 1 (MCPIP1)/ZC3H12A, a ribonuclease and deubiquitinase that suppresses inflammatory response (31, 32), was recently reported to antagonize Dicer by degrading pre-miRNAs to abort miRNA production (33).

Sjögren syndrome antigen B (SSB), also known as autoantigen La, is commonly associated with autoimmune disorders such as Sjögren syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus (34). The La/SSB protein is evolutionarily conserved from yeast to human, exists abundantly in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, and plays fundamental roles in diverse processes of RNA metabolism (35). A well known function of La/SSB is its association with nascent transcripts of RNA polymerase III, including precursors of tRNAs (pre-tRNAs), through recognition of the characteristic 3′ UUU termini. The binding of La/SSB protects pre-tRNAs from nonspecific exonuclease digestion and ensures correct processing of the 5′ and 3′ leader sequences of pre-tRNAs by specific ribonucleases, such as RNase P and RNase Z (36–38).

Both Drosophila and human La/SSB contain three RNA-binding motifs, a highly conserved La motif (LAM) (39), a canonical RNA recognition motif (RRM1), and an atypical RRM2, as well as a variable carboxyl (C) terminus. It has previously been shown that the amino (N)-terminal LAM-RRM1 domain of La/SSB is responsible for 3′ UUU recognition (40–42). Although La/SSB is dispensable for yeast viability (43, 44), it is essential in higher eukaryotes such as Drosophila and mice (45, 46). The molecular basis for this discrepancy is currently unclear. Here, we have uncovered an important function for La/SSB in promoting global miRNA expression by binding and stabilizing pre-miRNAs. Moreover, we showed that La/SSB interacts with pre-miRNAs by stem-loop recognition rather than 3′ UUU recognition. These significant findings provide fresh insights into the basic process of miRNA biogenesis, the diverse functions of La/SSB in RNA metabolism, and possibly the pathogenesis of cancer and autoimmune diseases.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

General Reagents and Antibodies

General RNA reagents were purchased from Ambion and Promega, and DNA oligos or siRNAs were synthesized by IDT. Both Dicer and human La/SSB antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, whereas actin, tubulin, and anti-FLAG antibodies were obtained from Sigma. Recombinant Drosophila Dicer-1·Loqs-PB and human Dicer·TRBP complexes were generated in insect cells as previously described (12, 17). Recombinant Drosophila and human La/SSB were produced in Escherichia coli and purified by nickel affinity and ion-exchange chromatography. Recombinant FLAG-tagged MCPIP1 and Drosha·DGCR8 complex was affinity purified from 293T cells following transient transfection (47).

Purification of La/SSB from S2 Extract

The cytoplasmic extract (S100) of Drosophila S2 cells (48) was precipitated by ammonium sulfate at 60% saturation. After a 30-min, 20,000 × g centrifugation step, the supernatant was dialyzed overnight in Buffer A (10 mm KOAc, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 2 mm Mg(OAc)2, 2.5 mm DTT), loaded onto a Mono S column, and eluted with a 300–600 mm NaCl gradient. The fractions with peak activity were dialyzed for 4 h, loaded onto a Mono Q column, and eluted with a 0–300 mm NaCl gradient. Finally, the peak fractions were directly loaded on a Smart Mono S column and eluted with a 300–600 mm NaCl gradient.

Immunoprecipitation of La/SSB Complexes

HeLa cell extract was prepared in RIPA buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm EDTA) freshly supplemented with protease inhibitors. HeLa extract was incubated with anti-human La/SSB monoclonal antibody or mouse IgG for 1 h at 4 °C, and protein G-Sepharose beads were added and rotated for another 4 h. After extensive wash of the beads (4 times in RIPA buffer, 3 times in RIPA buffer with 0.5 m NaCl, and once with buffer III (0.25 m LiCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% deoxycholate, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0), associated RNA was extracted from the beads by TRIzol and precipitated by ethanol.

Cross-linking and Immunoprecipitation Assay

To demonstrate in vivo association between La and pre-miRNAs, we transfected HeLa cells with a empty vector or FLAG-hLa/SSB expression construct. Thirty-six hours after transfection, HeLa cells were either untreated or treated with 1.0% formaldehyde before making protein extracts in RIPA buffer (49). The FLAG-La RNP complexes were immunoprecipitated from lysates using anti-FLAG (M2) antibody-conjugated affinity gel (Sigma). After extensive washing in a highly stringent condition (RIPA buffer containing 1 m NaCl and 4 m urea), the beads were resuspended in reversal buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.0, 5 mm EDTA, 10 mm DTT, and 1% SDS) and cooked at 70 °C for 1 h. Associated RNA was extracted by TRIzol (Invitrogen), and followed by RT-PCR to detect endogenous pre-miRNAs. The PCR primers for amplifying pri/pre-miRNAs were listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

siRNA targets, primer sequences, and Northern probes

| Primer sequences | |

|---|---|

| siLa1 (human) target sequence | 5′-GGUCGUAGAUUUAAAGGAA-3′ |

| siLa2 (human) target sequence | 5′-GGUUAGAAGAUAAAGGUCA-3′ |

| Cyclophillin (human) forward | 5′-TGCCATCGCCAAGGAGTAG-3′ |

| Cyclophillin (human) reverse | 5′-TGCACAGACGGTCACTCAAA-3′ |

| pri-let-7a (human) forward | 5′-CTCATTACACAGGAAACCGGAA-3′ |

| pri-let-7a (human) reverse | 5′-CCTCATCCCACAGTGAAGAGAA-3′ |

| pri-miR-16 (human) forward | 5′-CTGACATGCTTGTTCCACTCTAGC-3′ |

| pri-miR-16 (human) reverse | 5′-CCTGTCACACTAAAGCAGCACAAT-3′ |

| pri-miR-17 (human) forward | 5′-GTTGTTAGAGTTTGAGGTGTT-3′ |

| pri-miR-17 (human) reverse | 5′-AGCACTCAACATCAGCAGG-3′ |

| pri-miR-21 (human) forward | 5′-TACCATCGTGACATCTCCA-3′ |

| pri-miR-21 (human) reverse | 5′-CAGACAGAAGGACCAGAGTT-3′ |

| pri-miR-23b (human) forward | 5′-CAGTGTGTGCAGACAGCAC-3′ |

| pri-miR-23b (human) reverse | 5′-GTTCTCCAATCTGCAGTGA-3′ |

| pre-let-7a (human) forward | 5′-TGGGATGAGGTAGTAGGTTGT-3′ |

| pre-let-7a (human) reverse | 5′-TAGGAAAGACAGTAGATTGTATAGTT-3′ |

| pre-miR-21 (human) forward | 5′-TAGCTTATCAGACTGATGTTGA-3′ |

| pre-miR-21 (human) reverse | 5′-CGACTGCTGTTGCCATGAG-3′ |

| pre-miR-23b (human) forward | 5′-CAGGTGCTCTGGCTGCTT-3′ |

| pre-miR-23b (human) reverse | 5′-GTGGTAATCCCTGGCAATGT-3′ |

| Anti-5.8S (human) | 5′-TCCTGCAATTCACATTAATTCTCGCAG-3′ |

| Anti-5S (human) | 5′-CCGACCCTGCTTAGCTTCCGAGATCA-3′ |

| Anti-U6S (human) | 5′-CGTTCCAATTTTAGTATATGTGCTGCC-3′ |

| Anti-miR-16 | 5′-CGCCAAUAUUUACGUGCUGCUA-3′ |

| Anti-miR-17 | 5′-CUACCUGCACUGUAAGCACUUUG-3′ |

| Anti-miR-20 | 5′-CUACCUGCACUAUAAGCACUUUA-3′ |

| Anti-miR-21 | 5′-UCAACAUCAGUCUGAUAAGCUA-3′ |

| Anti-miR-23b | 5′-GGUAAUCCCUGGCAAUGUGAU-3′ |

| Anti-miR-30 | 5′-CUUCCAGUCGAGGAUGUUUACU-3′ |

| Anti-let-7a | 5′-AACUAUACAACCUACUACCUCA-3′ |

RNAi Knockdown

For siRNA-mediated knockdown in HeLa cells, 1 × 106 of cells were plated in a 10-cm dish and transfected with different siRNAs (siGFP, siLa1, or siLa2) by Lipofectamine RNAi Max (Invitrogen). After 2 days, transfected cells were replated at 1 × 106 cells/10-cm dish followed by a second siRNA transfection. Three days later, cells were harvested and total RNA was extracted by TRIzol. To generate the Teton-inducible La knockdown cells, we stably integrated a transgene that encodes four copies of a small hairpin RNA (shLa, same target sequence as siLa 2, Table 1) under control of an inducible H1 promoter, into U2OS cells expressing Tet repressor (Oligoengine). Doxycycline was added to the medium (2 μm final concentration) to induce the expression of small hairpin RNA (shLa). The U2OS/shLa (FLAG-dLa) rescue cell line was constructed by stable integration of a FLAG-tagged Drosophila La cDNA transgene into the U2OS/shLa cell line. Both HeLa and U2OS cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin.

Quantitative Analysis of miRNA Expression

Northern blotting for pre-miRNA and miRNA detection was performed essentially as described (50). Typically, 30 μg of total RNA was resolved by 12% urea-PAGE and transferred to GT membrane (Bio-Rad) followed by UV cross-linking. All miRNA probes are 21-nt ssDNA or RNA oligos (IDT) that are complementary to miRNA sequences provided by miRBase. The 5S, 5.8S, and U6 probe sequences are listed in Table 1. All probes were 5′ radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP by T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). Hybridization was conducted in ultrasensitive hybridization buffer (Ambion) at 40 °C overnight. The membrane was washed 3 times at 40 °C in 2× SSC, 0.5% SDS, and exposed to x-ray film.

Global miRNA Profiling

For RT-PCR, cDNAs were generated using the reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) and amplified by PCR with Taq polymerase. The primer sequences are listed in Table 1. TaqMan qPCR was performed to measure the levels of specific miRNAs or pri-miRNAs according to the manufacturer's protocol (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantities were calculated using the ΔΔCt method. 18S rRNA served as a loading control. Global miRNA profiling was performed using MegaPlex RT Primers and TaqMan Array microRNA Cards (Applied Biosystems, Human Pool A version 2.1 MegaPlex RT primers and Human MicroRNA A Cards version 2.0) according to the manufacturer's protocols. 750 ng of total RNA was used in Megaplex RT without pre-amplification. U6 snRNA served as the endogenous control as the average Ct varied by ≤0.2 between control and experimental treatments. Threshold was held constant at 0.2 ΔRn and baseline was set from cycles 3 to 16 for all miRNA. miRNA with average Ct ≥35 or abnormal amplification curves in control and experimental treatments were omitted and considered as not expressed. Average relative quantities were calculated among replicates and a t test was used to identify miRNA differentially expressed based on a p value threshold of p ≤ 0.05.

Native Gel-shift Assays

Synthetic pre-miRNAs were 5′ radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP by T4 polynucleotide kinase followed by G-25 column (Ambion) purification. The pri-let-7a-1 construct, a gift from Dr. Narry Kim, was used to generate uniformly radiolabeled pri-miRNA substrate by in vitro transcription followed by PAGE purification. Typically, recombinant proteins and radiolabeled RNA were incubated at 37 (human proteins) or 30 °C (Drosophila proteins) for 30 min in a 10-μl reaction (100 mm KOAc, 15 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 2.5 mm EDTA, 2.5 mm DTT, pH 7.4). The reaction mixture was resolved by a 5% native PAGE and exposed to x-ray film.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

Gene expression profiling data of breast cancer patients were obtained from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE7390) and bioinformatics.nki.nl/data.php. The expression levels of Dicer, La/SSB, or MCPIP1 were evaluated by the corresponding probes. Genes negatively or positively associated with Dicer expression (“Dicer high/low down-regulated or up-regulated genes”) were defined as 200 of the most differentially expressed genes between the top 30 cases with high and low Dicer expression. After dividing all cases into halves according to La expression, GSEA was performed with GSEA software available from the Broad Institute (51). Survival analysis was performed using the survival package of R, the survfit function, and the survdiff function. Classification of high or low expression of Dicer, La/SSB, and MCPIP1 was performed as previously described (52).

RESULTS

Purification and Reconstitution of La/SSB as a Regulator of Pre-miRNA Processing in Vitro

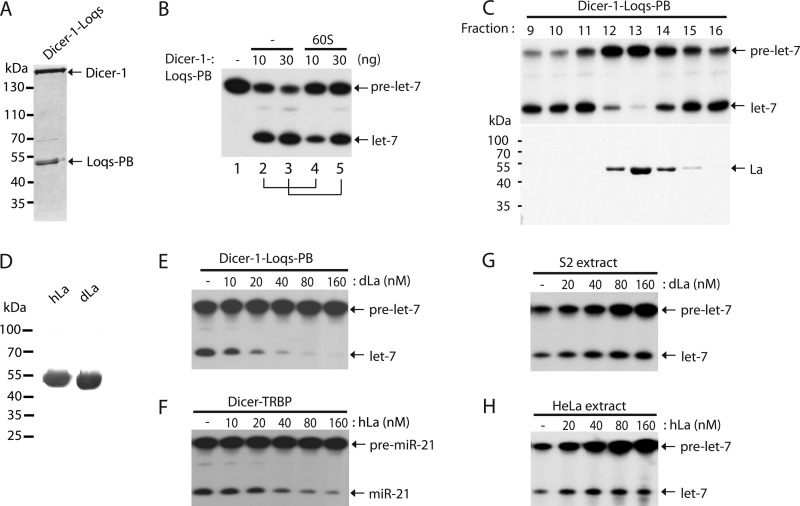

We took an unbiased biochemical approach to identify new regulators of miRNA biogenesis by supplementing recombinant Dicer-1·Loqs-PB complex (Fig. 1A) with the fractions of cytoplasmic extract (S100) of Drosophila S2 cells. We observed an inhibitory activity of pre-miRNA processing in the supernatant after 60% saturation of ammonium sulfate precipitation of S2/S100 (Fig. 1B). This factor was further purified to homogeneity by sequential chromatographic fractionation (Fig. 1C). At the final purification step, only a single protein of ∼50 kDa appeared on the silver-stained polyacrylamide gel (PAGE), and correlated closely with the miRNA regulatory activity (Fig. 1C). This protein was identified as the Drosophila homolog of La/SSB by mass spectrometric analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Purification and reconstitution of La/SSB as a regulator of pre-miRNA processing. A, Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE showing recombinant Drosophila Dicer-1·Loqs-PB complex purified from insect cells. B, the pre-miRNA processing assay was performed in buffer (lane 1) or with 10 or 30 ng of recombinant Dicer-1·Loqs-PB complex in the absence (lanes 2 and 3) or presence (lanes 4 and 5) of 60% ammonium sulfate supernatant (60S) of S2 extract. C, purification of endogenous La/SSB from S2 extract by sequential chromatographic fractionation. At the final Mono S step, individual fractions were assayed with recombinant Dicer-1·Loqs-PB complex for pre-miRNA processing activity (top) or resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining (bottom). D, Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE showing purified Drosophila (dLa) or human (hLa) La/SSB. E, the pre-miRNA processing assays were performed using ∼10 nm recombinant Dicer-1·Loqs-PB complex with increasing concentrations of recombinant dLa. F, the pre-miRNA processing assays were conducted using ∼10 nm recombinant Dicer·TRBP complex with increasing concentrations of recombinant hLa. G, the pre-miRNA processing assays were conducted using 10 μg of crude S2 extract with increasing concentrations of recombinant dLa. H, the pre-miRNA processing assays were conducted using 10 μg of HeLa extract with increasing concentrations of recombinant hLa.

We generated His-tagged Drosophila (dLa) and human (hLa) La/SSB recombinant proteins (Fig. 1D). Addition of dLa efficiently suppressed the ability of the recombinant Dicer-1·Loqs-PB complex to process pre-miRNA into miRNA in vitro (Fig. 1E). Likewise, hLa could inhibit pre-miRNA processing by the recombinant Dicer·TRBP complex (Fig. 1F). Intriguingly, we obtained a strikingly different result when performing pre-miRNA processing assays using crude cell extracts. Addition of La/SSB could instead stabilize pre-miRNA and enhance miRNA production in both S2 and HeLa cell extracts (Fig. 1, G and H). The degree of miRNA increase was smaller than that of the pre-miRNA increase, suggesting a combined effect of pre-miRNA stabilization and sequestration at work.

La/SSB Is a Pre-miRNA-binding Protein

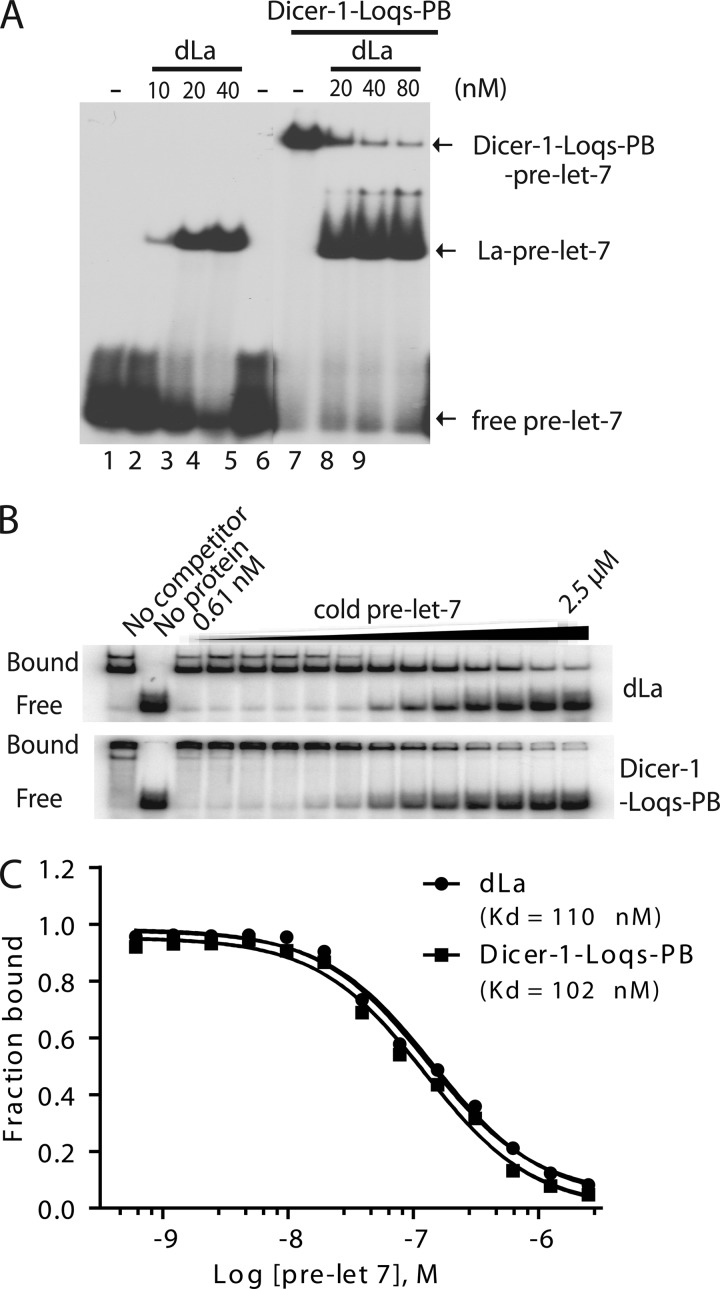

Recombinant dLa could efficiently bind pre-miRNA and compete with Dicer-1·Loqs-PB complex for pre-miRNA binding in vitro (Fig. 2A), suggesting that the binding of pre-miRNA by dLa is incompatible with that of the Dicer complex. Furthermore, recombinant dLa and Dicer-1·Loqs-PB exhibited comparable binding affinity for pre-miRNA in vitro (Fig. 2, B and C). A similar phenomenon was observed for recombinant hLa and Dicer·TRBP complex (data not shown). These results suggest that pre-miRNAs could be readily exchanged between La/SSB and the Dicer complex. Therefore, in a recombinant system, La/SSB could suppress miRNA production by sequestering pre-miRNA away from Dicer. However, in the crude extract or live cells, we hypothesized that La/SSB might promote miRNA expression by protecting pre-miRNAs from nuclease-mediated decay to allow for productive processing by Dicer.

FIGURE 2.

La/SSB binds pre-miRNA to regulate pre-miRNA processing in vitro. A, native gel-shift assays by incubating 5′ radiolabeled pre-let-7 in buffer (lanes 1 and 5), recombinant dLa (lanes 2–4), Dicer-1·Loqs-PB complex alone (lane 6) or together with various concentrations of dLa (lanes 7–9). B, the competition binding assays were performed by incubating equivalent recombinant dLa or Dicer-1·Loqs-PB complex with radiolabeled pre-let-7 in the presence of increasing concentrations of cold pre-let-7. C, quantitative analysis of the data in B, and relative Kd value was measured by GraphPad Prism 5 software.

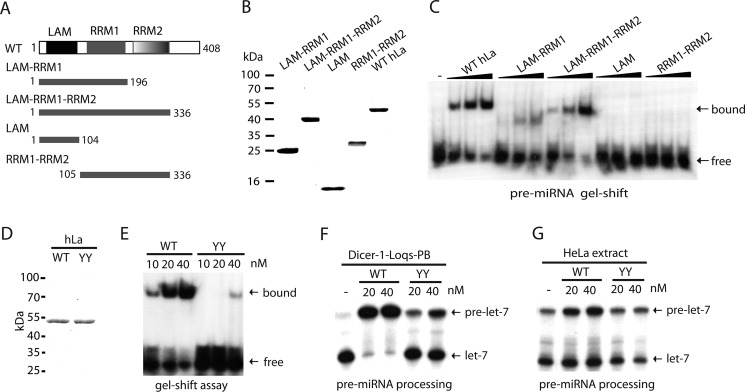

The LAM, RRM1, and RRM2 Motifs of La/SSB Are All Required for Efficient Pre-miRNA Binding

To map which domains of La/SSB are important for binding pre-miRNA, we generated a series of truncated human La/SSB recombinant proteins (Fig. 3, A and B), and compared their pre-miRNA binding by gel-shift assays. Although LAM-RRM1 showed weak binding to pre-miRNA, neither LAM nor RRM1-RRM2 was able to bind pre-miRNA (Fig. 3C). In contrast, LAM-RRM1-RRM2 could bind pre-miRNA almost as efficiently as full-length La/SSB (Fig. 3C). Thus, the LAM, RRM1, and RRM2 motifs of La/SSB are all required for efficient binding of pre-miRNA. This mode of interaction is clearly distinct from the previously established mode of 3′ UUU recognition by LAM-RRM1 (40–42).

FIGURE 3.

The LAM, RRM1, and RRM2 motifs of La/SSB are all required for efficient pre-miRNA binding. A, schematic domain structures of full-length and truncated human La/SSB. B, Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE showing various purified recombinant La/SSB. C, native gel-shift assays comparing the binding of various recombinant La/SSB to 5′ radiolabeled pre-let-7. D, Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE showing wild-type (WT) and Y23A,Y24A (YY) mutant hLa recombinant proteins. E, native gel-shift assays comparing the ability of WT and YY mutant hLa to bind radiolabeled pre-let-7a-1. F, the pre-miRNA processing assays were performed with recombinant Dicer-1·Loqs-PB complex alone or together with WT or YY mutant hLa. G, the pre-miRNA processing assays were performed with 10 μg of HeLa extract alone or together with recombinant WT or YY mutant hLa.

La/SSB Regulates Pre-miRNA Processing by Binding Pre-miRNA

Two tyrosines (Tyr-23, Tyr-24) in the LAM of human La/SSB have previously been shown to be critical for 3′ UUU binding (34). In our assays, mutations of Tyr-23 and Tyr-24 to alanine (YY) diminished the ability hLa to bind pre-miRNA (Fig. 3, D and E). Accordingly, the YY mutant also lost its ability to either inhibit pre-miRNA processing by recombinant Dicer-1·Loqs-PB complex (Fig. 3F), or stabilize pre-miRNA and enhance miRNA production in HeLa extract (Fig. 3G). These results suggest that the activity of La/SSB to regulate pre-miRNA processing is dependent on its ability to bind pre-miRNA.

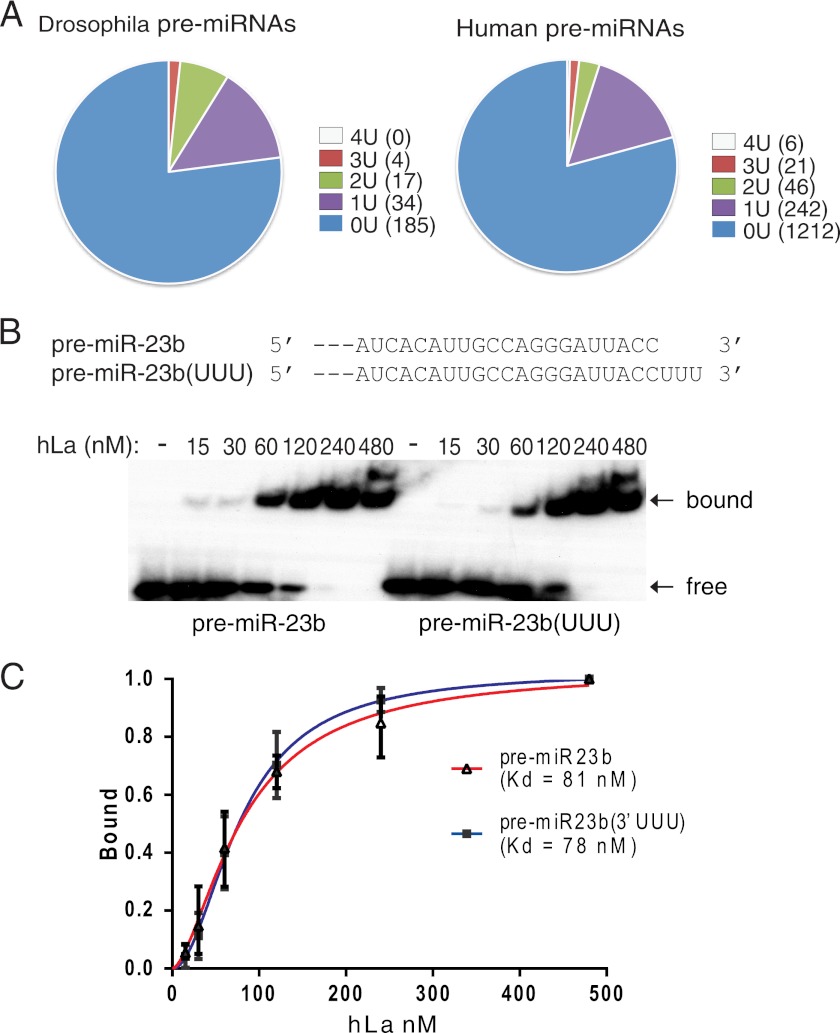

La/SSB Binds Pre-miRNAs via a 3′ UUU-independent Mechanism

Profiling of the miRNA database found that the majority of Drosophila and human pre-miRNAs lack the 3′ UUU terminus (Fig. 4A). Among the 240 fly pre-miRNAs, only three have 3 Us out of the last four nucleotides. Among the 1,527 human pre-miRNAs, only six carry a 3′ UUUU tail and 21 have 3 Us within the last four nucleotides. Accordingly, recombinant hLa could efficiently bind a number of synthetic pre-miRNAs lacking 3′ UUU (data not shown). Moreover, we carefully compared the binding of hLa to mouse pre-miR-23b (lacking 3′ UUU) and a modified pre-miR-23b that carried 3′ UUU (Fig. 4, B and C). These experiments showed that addition of 3′ UUU made little or no change to the binding of La/SSB to pre-miR-23b. Taken together, these studies suggest that La/SSB primarily binds pre-miRNAs via a 3′ UUU-independent mechanism.

FIGURE 4.

La/SSB binds pre-miRNA independent of 3′ UUU terminus. A, bioinformatic analysis of the number of Us in the 3′ terminal four nucleotides among the Drosophila (left) or human (right) pre-miRNAs in the miRNA database. B, native gel-shift assays comparing the binding of recombinant hLa/SSB to mouse pre-miR-23b and a modified pre-miR-23b(UUU). The 3′ sequences of pre-miRNAs are listed above. C, quantitative analysis of the data in B, and the relative Kd value was measured by GraphPad Prism 5 software.

La/SSB Recognizes the Stem-Loop Structure of Pre-miRNAs

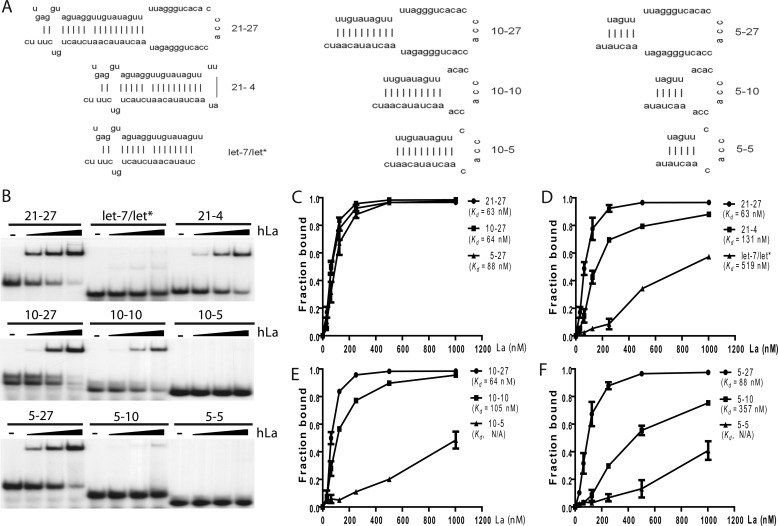

Because all pre-miRNAs share a stem-loop structure, we hypothesized that La/SSB could recognize the common stem-loop structure rather than specific sequences of pre-miRNAs. To test this idea, we synthesized a series of truncated forms of human pre-let-7a-1, which consists of a 21-bp imperfect double-stranded stem and a 27-nt single-stranded loop (21–27) (Fig. 5A). Shortening the loop of pre-let-7a-1 from 27 to 4 nt reduced the binding of hLa, whereas deleting the loop abolished the binding of hLa to pre-let-7a-1, as in the case of let-7a/let* miRNA duplex (Fig. 5, B and D). Thus, the loop of pre-miRNA is critical for La/SSB binding, but in a sequence-independent manner as the binding of pre-let-7a-1 was not affected by substituting its loop with antisense sequence (data not shown). However, the La/SSB-pre-miRNA interaction cannot be explained by the loop binding alone because the binding of pre-let-7a-1 could not be competed off with an excess amount of ssRNA (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

La/SSB recognizes the characteristic stem-loop structure of pre-miRNA. A, schematic representation of the stem-loop structures of full-length and various truncated human pre-let-7a-1. B, native gel-shift assays were performed to compare the binding of recombinant hLa to 5′ radiolabeled full-length or truncated pre-let-7a-1. C–F, quantitative analysis comparing the relative binding affinity of recombinant hLa for full-length and various truncated mutants of human pre-let-7a-1. Values represent mean ± S.D., n = 3.

Surprisingly, shortening the double-stranded stem of pre-let-7a-1 had little impact on the binding of hLa as shown by the similar dissociation constant (Kd) among the 21–27, 10–27, and 5–27 forms of pre-let-7a-1 (Fig. 5, B and C). Notably, removing 3′ UUUC from pre-let-7a-1 did not affect hLa binding, either. However, a clear combinatorial effect was observed when both the stem and loop of pre-let-7a-1 were shortened at the same time. For example, recombinant hLa could efficiently bind the 10–27 (Kd = ∼64 nm) or 10–10 (Kd = ∼105 nm) mutants, but the binding of 10–5 mutant was greatly diminished (Fig. 5, B and E). Likewise, hLa showed strong binding to the 5–27 (Kd = ∼88 nm) mutant, but not to the 5–10 (Kd = ∼357 nm) or 5–5 mutants (Kd was too big to be accurately measured) (Fig. 5, B and F). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that La/SSB recognizes the characteristic stem-loop structure of pre-miRNAs.

La/SSB Associates with Cellular Pre-miRNAs in Vivo

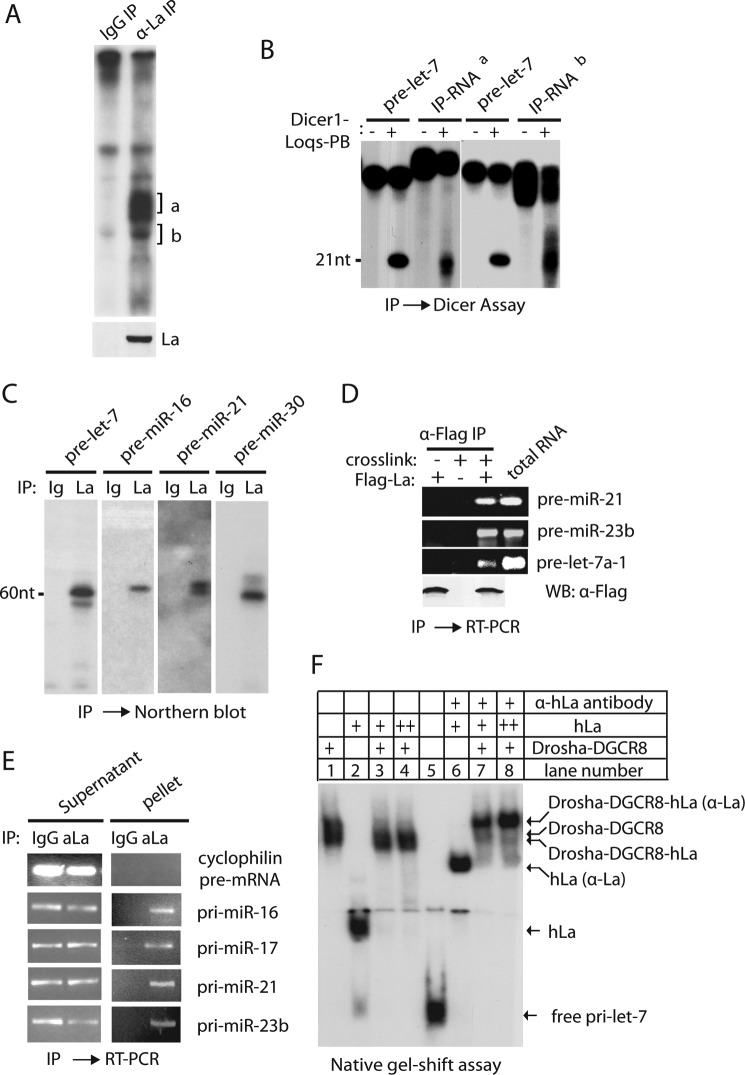

We employed a monoclonal anti-hLa/SSB antibody to immunoprecipitate (IP) the endogenous La/SSB RNA·protein (RNP) complexes from HeLa cell extract. By 5′ radiolabeling of associated RNA, we detected abundant ∼60–80-nt RNA species in the IPs of anti-hLa/SSB antibodies, but not in the IPs of control IgG (Fig. 6A). The La/SSB-associated RNAs likely contained pre-miRNAs because they could be efficiently cleaved by the Dicer-1·Loqs-PB complex into ∼21-nt small RNA (Fig. 6B). The interaction between endogenous La/SSB and pre-miRNAs was further confirmed by Northern blotting (Fig. 6C). To eliminate the possibility that La/SSB only associated with pre-miRNAs after cell lysis, we demonstrated in vivo association between FLAG-La and pre-miRNAs by cross-linking of live HeLa cells followed by co-IPs (CLIP) under stringent washing conditions that only tolerated covalent RNA-protein linkage (Fig. 6D) (49).

FIGURE 6.

La/SSB associates with cellular pri-/pre-miRNAs in vivo. A, after IP of HeLa extract by mouse IgG or anti-hLa/SSB monoclonal antibodies, associated RNAs were extracted and 5′ radiolabeled, resolved by 10% urea-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography. B, two bands of La/SSB-associated RNA were recovered from urea-PAGE in A and incubated with recombinant Dicer-1·Loqs-PB complex to assay for miRNA production. Synthetic pre-let-7 was used as a positive control. C, Northern blotting specifically detected a number of pre-miRNAs in the IPs of anti-hLa/SSB antibodies. D, after transfection of a vector or FLAG-hLa construct, HeLa cells were treated with formaldehyde cross-linking before cell lysis. Immunoprecipitation of FLAG-La from lysates was carried out with stringent washing conditions followed by RT-PCR to detect the presence of endogenous pre-miRNAs in the FLAG-La RNP complexes. E, after immunoprecipitation of HeLa nuclear extract by mouse IgG or anti-hLa/SSB antibodies, associated RNAs were extracted from both pellets and supernatants, and followed by RT-PCR to detect the presence of pri-miRNA transcripts or cyclophilin pre-mRNA. F, native gel-shift assays were performed by incubating radiolabeled pri-let-7a-1 with buffer (lane 5), Drosha-DGCR8 complex (lane 1), hLa (lane 2), hLa + Drosha-DGCR8 (lanes 3 and 4), hLa + anti-La antibody (lane 6), hLa + Drosha-DGCR8 + anti-hLa antibody (lanes 7 and 8).

La/SSB Associates with Pri-miRNAs in Vitro and in Vivo

We also examined the association of endogenous La/SSB and pri-miRNA transcripts in the nuclear extract of HeLa cells. The presence of pri-miRNAs, but not cyclophilin pre-messenger RNA, was specifically detected by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR in the La/SSB RNP complexes (Fig. 6E). Furthermore, recombinant hLa could directly bind radiolabeled pri-miRNA in vitro as shown by native gel-shift assay (Fig. 6F). Interestingly, the binding of hLa to pri-miRNA appeared compatible with that of the Drosha·DGCR8 complex (Fig. 6F, compare lanes 1–4). This was confirmed by the supershift of the complex of hLa, Drosha·DGCR8, and pri-miRNA caused by anti-hLa/SSB antibodies (Fig. 6F, compare lanes 7 and 8 to lanes 3, 4, and 6). Accordingly, addition of hLa had little effect on in vitro pri-miRNA processing by recombinant Drosha·DGCR8 complex (data not shown). Collectively, these studies indicate that La/SSB associates with cellular pri-/pre-miRNAs in vivo.

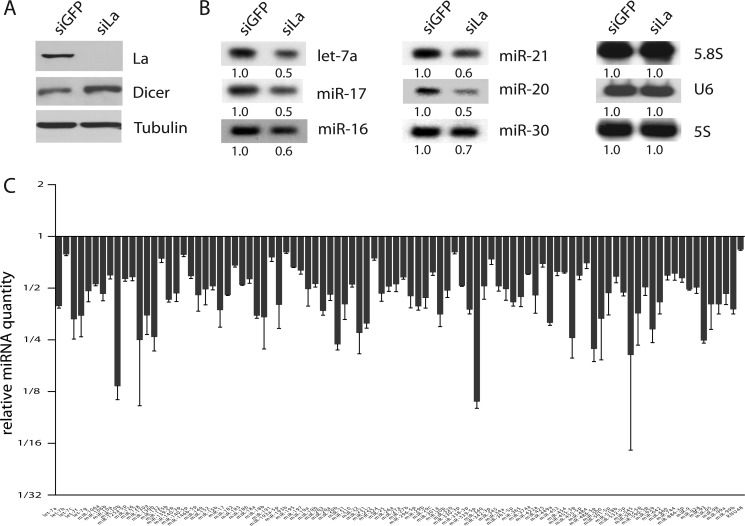

La/SSB Is Required for Global miRNA Expression in Vivo

To determine whether La/SSB regulates miRNA expression in vivo, we performed siRNA-mediated knockdown of La/SSB expression in HeLa cells (Fig. 7A), and followed with Northern blotting to measure the levels of six endogenous miRNAs. Consistent with our hypothesis that La/SSB promotes miRNA expression by stabilizing pre-miRNAs, there was a substantial reduction of all six miRNAs in La/SSB-depleted cells as compared with the control siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 7B). In contrast, the levels of 5.8S or 5S rRNA and U6 RNA remained unchanged (Fig. 7B), suggesting that the lack of La/SSB had a specific impact on miRNA expression.

FIGURE 7.

La/SSB is required for global miRNA expression in vivo. A, Western blots comparing the levels of La/SSB, Dicer, and α-Tubulin proteins between GFP-siRNA (siGFP) and La-siRNA (siLa1)-treated HeLa cells. B, Northern blots comparing the levels of six endogenous miRNAs, U6 snRNA, and 5.8S or 5S rRNA between siGFP- and siLa-treated HeLa cells. C, quantitative analysis of global miRNA expression between siGFP- and siLa-treated HeLa cells. The levels of miRNAs were measured by TaqMan qPCR microRNA low density arrays and normalized to U6 snRNA (≤0.2 Ct difference among all samples). The relative miRNA quantity was calculated as the ratio of siLa/siGFP samples. Values represent mean ± S.D., n = 3.

Furthermore, we examined the global effect of La/SSB knockdown on miRNAs by profiling the expression of 377 mature miRNAs by TaqMan qPCR in control and La/SSB siRNA-treated HeLa cells (Fig. 7C). Approximately 58% (94 of 161) of the expressed miRNAs displayed a statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) reduction in the La/SSB-deficient cells, whereas U6 RNA expression was unchanged. The remainder of expressed miRNAs displayed either low (Ct > 32) or variable (p > 0.05) expression. None of the miRNAs exhibited increased expression in repeated experiments. These findings were further validated by individual TaqMan qPCR of randomly selected miRNAs (data not shown). These results suggest that La/SSB is required for global miRNA expression in vivo.

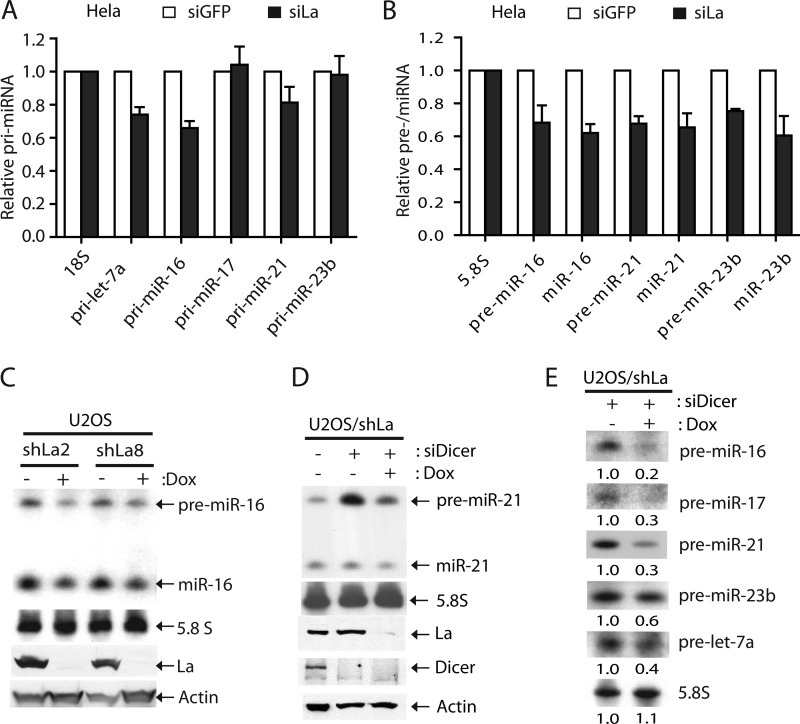

La/SSB Promotes miRNA Expression by Stabilizing Pre-miRNAs

We compared the levels of pri-, pre-, and mature miRNAs between control and La/SSB-depleted HeLa cells by TaqMan qPCR and Northern blotting. Although the levels of some pri-miRNAs remained the same, others were slightly decreased upon La/SSB depletion (Fig. 8A). In general, we detected a more substantial reduction of pre-miRNAs that was consistent with the degree of miRNA reduction in La/SSB-deficient cells (Fig. 8, A and B, and data not shown). Notably, although the level of pri-miR-23b remained unchanged, both pre-miR-23b and mature miR-23b were reduced by ∼30% when La/SSB was depleted (Fig. 8, A and B). A similar phenomenon was observed in Teton-inducible La/SSB knockdown osteosarcoma (U2OS) cells. In these cells, induction of a short hairpin RNA (shLa) could effectively silence endogenous La/SSB expression, resulting in the concomitant reduction of pre-miRNAs and miRNAs (Fig. 8C). In another set of experiments, we also knocked down the expression of Dicer to allow for accumulation of pre-miRNAs in U2OS/shLa cells. In this case, we observed a much more dramatic reduction of pre-miRNAs when both La/SSB and Dicer were depleted (Fig. 8, D and E). Collectively, these results suggest that La/SSB promotes miRNA expression by stabilizing pre-miRNAs in mammalian cells.

FIGURE 8.

La/SSB promotes miRNA expression by stabilizing pre-miRNAs. A, quantitative analysis of pri-miRNA expression between siGFP- and siLa-treated HeLa cells by TaqMan PCR. 18S rRNA was used as a loading control. B, quantitative analysis of pre-miRNA and miRNA expression between siGFP- and siLa-treated HeLa cells by Northern blotting. 5.8S rRNA was used as loading control. C, Northern analysis of pre-miR-16 and miR-16 expression in two U2OS/shLa cell lines cultured in the absence or presence of 2 μm doxycycline. Western blotting was performed to compare the levels of La/SSB or actin protein. D, Northern analysis of pre-miR-21 and miR-21 expression in U2OS/shLa cells, in which La/SSB, Dicer, or both were knocked down by RNAi. Western blotting was performed to compare the levels of La/SSB, Dicer, or actin protein. E, Northern analysis of the levels of various pre-miRNAs in U2OS/shLa cells, in which expression of La/SSB and/or Dicer was knocked down.

La/SSB Protects Pre-miRNA from MCPIP1-mediated Degradation

In further support of this idea, we found that radiolabeled pre-miRNA was much less stable in the La/SSB-depleted extract than in the control extract (Fig. 9A). Thus, the lack of La/SSB likely rendered pre-miRNAs more vulnerable to degradation by ribonucleases other than Dicer. The first example of such ribonucleases is MCPIP1, which was recently identified to inhibit miRNA production by cleaving the loop region of specific pre-miRNAs (33). Here, we showed that addition of hLa protected pre-miRNA from recombinant MCPIP1-mediated degradation in vitro (Fig. 9B). Furthermore, co-expression of hLa could antagonize the negative effect of MCPIP1 overexpression by stabilizing pre-miRNAs to enhance miRNA expression (Fig. 9C). Finally, the levels of both pre-miRNAs and miRNAs could be restored in La/SSB-deficient U2OS/shLa cells by expression of a FLAG-tagged Drosophila La/SSB transgene (Fig. 9, D–F). This experiment not only confirms that the miRNA phenotype is specifically due to the La/SSB deficiency, but also suggests that La/SSB plays an evolutionarily conserved role in miRNA regulation from flies to human. Therefore, our genetic and biochemical studies demonstrate that La/SSB promotes global miRNA expression by stabilizing pre-miRNAs from nuclease (e.g. MCPIP1)-mediated degradation.

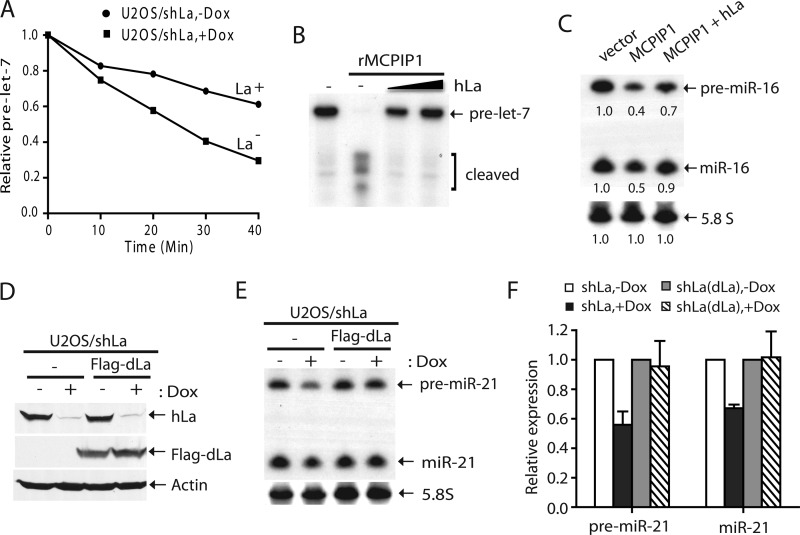

FIGURE 9.

La/SSB protects pre-miRNAs from nuclease (e.g. MCPIP1)-mediated decay. A, a time course experiment comparing stability of a 5′ radiolabeled pre-miRNA in La+ versus La− extract prepared from U2OS/shLa cells cultured without (La+) or with doxycycline (La−). B, in vitro RNase assay showing that addition of hLa protects 5′ radiolabeled pre-miRNA from recombinant MCPIP1-mediated degradation. C, Northern analysis of pre-miR-16 and miR-16 expression in 293T cells transiently transfected with a pri-miR-16 expression construct and vector, FLAG-MCPIP1 and/or FLAG-hLa constructs. D, Western blotting was performed to detect endogenous hLa, transgenic FLAG-dLa, and actin in U2OS/shLa or U2OS/shLa (+FLAG-dLa) cells. E, Northern analysis of pre-miR-21 and miR-21 expression in U2OS/shLa or U2OS/shLa (+FLAG-dLa) cells cultured without or with doxycycline. F, quantitative analysis of the data in E for four independent sets of experiments.

Cooperative Relationships between La/SSB and Dicer in Human Cancers

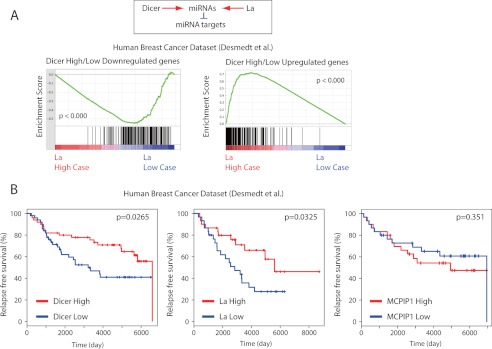

It was previously reported that MCPIP1 and Dicer are in a antagonistic relationship in the transcriptome data of lung cancer patients (33). Thus, we analyzed the functional relationship between Dicer and La/SSB in human malignancies. To this end, we performed GSEA (51) to examine whether genes associated negatively or positively with Dicer expression status are overexpressed or underexpressed along with La/SSB expression status, using several public gene expression datasets of human malignancies. Intriguingly, we observed a potential cooperative relationship between Dicer and La/SSB in human breast cancer datasets (53). In this dataset, the Dicer high/low down-regulated genes are enriched in patients with low La/SSB expression (“La low case”) (Fig. 10A). Conversely, the Dicer high/low up-regulated genes are enriched in patients with high La/SSB expression (”La high case”) (Fig. 10A). This cooperative relationship between Dicer and La/SSB is opposite to the antagonistic relationship between Dicer and MCPIP1 in human cancer transcriptome (33).

FIGURE 10.

Cooperative relationships between La/SSB and Dicer in human cancers. A, GSEA for genes negatively or positively associated with Dicer expression (Dicer high/low down-regulated or up-regulated genes), along with patients with high and low La/SSB expression (La high case versus La low case), in the cohort of breast cancer patients. B, Kaplan-Meier plots representing the survival probability in this dataset, according to low or high expression levels of Dicer, La/SSB, and MCPIP1. The log-rank test p value reflects the significance of the association between low expression and Dicer and La/SSB and poor prognosis.

Furthermore, low levels of La/SSB and Dicer were both associated with poor clinical outcome in breast cancer patients (Fig. 10B). Conversely, a high level of MCPIP1 is associated with worse prognosis. Although we failed to detect statistical significance in the latter case, the general trend is similar to what was previously reported in lung cancer patients (33). We also observed similar correlations in another dataset of breast cancer patients (54) (data not shown). Thus, these results highlight an interesting tripartite relationship among Dicer, La/SSB, and MCPIP1 in the context of human malignancies. Taken together, these studies suggest that consistent with their critical roles in miRNA expression, the expression status of Dicer and La/SSB might have cooperative effects on the transcriptome and prognosis of certain human cancers.

DISCUSSION

In summary, we have identified a new housekeeping function of autoantigen La/SSB in promoting global miRNA expression by binding and stabilizing pre-miRNAs. We propose a revised working model for the basic process miRNA biogenesis. In the nucleus, La/SSB associates with nascent pri-miRNA transcripts and is required for the stability of some pri-miRNAs. The binding of La/SSB to pri-miRNAs is compatible with binding of the Drosha complex that processes pri-miRNAs into pre-miRNAs. Nascent pre-miRNAs are protected by La/SSB from degradation by other nucleases, such as MCPIP1. The comparable binding affinity allows pre-miRNAs to be easily transferred from La/SSB to the Dicer complex for processing into mature miRNAs. It is also plausible that this transfer process may be influenced by other proteins or by post-translational modifications. The work reveals a new concept of the pre-miRNA holding complex that protects and escorts nascent pre-miRNAs through the miRNA biogenesis pathway.

The La/SSB protein is well known for its versatile interactions with diverse RNA molecules, including numerous Pol III transcripts, specific cytoplasmic mRNA, and viral-encoded transcripts (35). Most of previous studies have focused on the interaction between La/SSB and 3′ UUU of Pol III transcripts, such as pre-tRNAs. However, a few recent studies have reported that La/SSB associate with specific cellular and viral transcripts through a poorly understood, 3′ UUU-independent mechanism (35). La/SSB has recently been shown to bind the domain IV stem-loop sequence of the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) of hepatitis C Virus mRNA (66). La/SSB recognizes the structure rather than specific sequence of domain IV RNA, and this association requires its three RNA binding motifs (i.e. LAM, RRM1 and RRM2). Herein, we have determined that La/SSB recognizes the typical stem-loop structure of pre-miRNAs. These studies implicate that stem-loop recognition may serve as a new mechanism that mediates association between La/SSB with diverse RNA lacking 3′ UUU.

It is possible that additional sequence features may further modulate the binding of La/SSB to pre-miRNAs. Lin28 recruits terminal uridyltransferase TUT4 to the polyuridylate 3′ end of a small subset of pre-miRNAs, including pre-let-7 (26, 28). In this case, however, 3′ polyuridylation (addition of 5 to 19 Us) of pre-miRNA inhibits Dicer processing and leads to premature pre-miRNA degradation. It is unclear how many endogenous pre-miRNAs are uridylated at the 3′ terminus. Our studies indicate that addition of 3′ UUU to a pre-miRNA have little effect on La/SSB binding. Thus, the interaction between La/SSB and pre-miRNA is primarily mediated by stem-loop recognition. This mode of interaction is similar to the mechanism of how the Dicer complex recognizes pre-miRNAs of diverse sequences.

Although La/SSB is dispensable for yeast viability (43, 44), La/SSB-deficient flies and knock-out mice die at early embryonic stage and La/SSB−/− blastocysts fail to develop into embryonic stem cells in vitro (45, 46). These phenotypes are reminiscent of those displayed by mutant flies or mice lacking key miRNA-generating factors, such as Drosha, Dicer, Loqs, or Pasha/DGCR8 (11, 55–59). Because miRNAs do not exist in the budding or fission yeast, these observations are consistent with our theory that La/SSB plays an essential role in higher eukaryotes through regulation of global miRNA expression.

The previous and current studies suggest a dynamic process where La/SSB, MCPIP1, and Dicer compete to regulate miRNA production by modulating the levels of pre-miRNAs (33). Alterations of miRNA expression are linked to a wide range of pathological processes, including cancer (1, 3). It has been shown that the miRNA machineries can be modified by multiple mechanisms in human cancers. Such aberrant regulations include down-regulation of the miRNA processing enzymes, e.g. Dicer and Drosha (52, 60), and mutations of cofactors, e.g. TRBP, Exportin-5 (63, 64), and possibly La/SSB (this study). In several types of human malignancies, there are clear correlations between impaired miRNA processing, e.g. low expression of Drosha, Dicer, and La/SSB or high expression of MCPIP1, and poor prognosis of cancer patients (33, 60–62). Collectively, these observations strongly suggest that a global reduction in miRNA expression, coupled with overexpresion of specific oncogenic miRNAs, may be a distinct feature for certain, if not all of, human cancers.

Mounting studies indicate that miRNAs play critical roles in maintaining the homeostasis of the immune system and safeguarding autoimmunity (63). Human patients suffering Sjögren syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus frequently produce autoantibodies against specific classes of RNA-binding proteins. These autoantigens include the commonly known La/SSB and Ro, as well as components of the miRNA pathway, such as Dicer, Argonaute, and GW182 (64, 65). Here, we have identified that autoantigen La/SSB also functions as a key regulator of global miRNA expression. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate if inactivation of La/SSB, such as by autoantibodies, down-regulation of expression, and/or phosphorylation, contributes directly to the pathogenesis of these autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Brian Cullen, Narry V. Kim, and Xiaodong Wang for providing useful reagents, Drs. Yi Liu and Nicholas Conrad for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by Grants 23112702 and 24689018 (to H. I. S.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, a grant (I-1608 to Q. L.) from the Welch Foundation, and grants from the National Institute of Health awarded to M. F., P. J., and Q. L.

- miRNA

- microRNA

- SSB

- Sjögren syndrome antigen B

- MCPIP1

- monocyte chemotactic protein-induced protein 1

- nt

- nucleotide(s)

- LAM

- La motif

- RRM

- RNA recognition motif

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- GSEA

- gene set enrichment analysis

- IP

- immunoprecipitate

- RNP

- ribonucleoprotein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bartel D. P. (2004) MicroRNAs. Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116, 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fabian M. R., Sonenberg N., Filipowicz W. (2010) Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 351–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. He L., Hannon G. J. (2004) MicroRNAs. Small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5, 522–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ambros V. (2004) The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431, 350–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Denli A. M., Tops B. B., Plasterk R. H., Ketting R. F., Hannon G. J. (2004) Processing of primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor complex. Nature 432, 231–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gregory R. I., Yan K. P., Amuthan G., Chendrimada T., Doratotaj B., Cooch N., Shiekhattar R. (2004) The Microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature 432, 235–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Han J., Lee Y., Yeom K. H., Nam J. W., Heo I., Rhee J. K., Sohn S. Y., Cho Y., Zhang B. T., Kim V. N. (2006) Molecular basis for the recognition of primary microRNAs by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex. Cell 125, 887–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee Y., Ahn C., Han J., Choi H., Kim J., Yim J., Lee J., Provost P., Rådmark O., Kim S., Kim V. N. (2003) The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature 425, 415–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lund E., Güttinger S., Calado A., Dahlberg J. E., Kutay U. (2004) Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science 303, 95–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yi R., Qin Y., Macara I. G., Cullen B. R. (2003) Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev. 17, 3011–3016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Förstemann K., Tomari Y., Du T., Vagin V. V., Denli A. M., Bratu D. P., Klattenhoff C., Theurkauf W. E., Zamore P. D. (2005) Normal microRNA maturation and germ-line stem cell maintenance requires Loquacious, a double-stranded RNA-binding domain protein. PLoS Biol. 3, e236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jiang F., Ye X., Liu X., Fincher L., McKearin D., Liu Q. (2005) Dicer-1 and R3D1-L catalyze miRNA maturation in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 19, 1674–1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saito K., Ishizuka A., Siomi H., Siomi M. C. (2005) Processing of pre-microRNAs by the Dicer-1-Loquacious complex in Drosophila cells. PLoS Biol. 3, e235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chendrimada T. P., Gregory R. I., Kumaraswamy E., Norman J., Cooch N., Nishikura K., Shiekhattar R. (2005) TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing. Nature 436, 740–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haase A. D., Jaskiewicz L., Zhang H., Lainé S., Sack R., Gatignol A., Filipowicz W. (2005) Mammalian Dicer finds a partner. EMBO Rep. 6, 961–967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hutvágner G., McLachlan J., Pasquinelli A. E., Bálint E., Tuschl T., Zamore P. D. (2001) A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science 293, 834–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paroo Z., Ye X., Chen S., Liu Q. (2009) Phosphorylation of the human microRNA-generating complex mediates MAPK/Erk signaling. Cell 139, 112–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carthew R. W., Sontheimer E. J. (2009) Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell 136, 642–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim V. N., Han J., Siomi M. C. (2009) Biogenesis of small RNAs in animals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 126–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu Q., Paroo Z. (2010) Biochemical principles of small RNA pathways. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 295–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Trabucchi M., Briata P., Filipowicz W., Ramos A., Gherzi R., Rosenfeld M. G. (2010) KSRP promotes the maturation of a group of miRNA precursors. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 700, 36–42 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Trabucchi M., Briata P., Garcia-Mayoral M., Haase A. D., Filipowicz W., Ramos A., Gherzi R., Rosenfeld M. G. (2009) The RNA-binding protein KSRP promotes the biogenesis of a subset of microRNAs. Nature 459, 1010–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Davis B. N., Hilyard A. C., Lagna G., Hata A. (2008) SMAD proteins control DROSHA-mediated microRNA maturation. Nature 454, 56–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Michlewski G., Cáceres J. F. (2010) Antagonistic role of hnRNP A1 and KSRP in the regulation of let-7a biogenesis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1011–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hagan J. P., Piskounova E., Gregory R. I. (2009) Lin28 recruits the TUTase Zcchc11 to inhibit let-7 maturation in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 1021–1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Heo I., Joo C., Cho J., Ha M., Han J., Kim V. N. (2008) Lin28 mediates the terminal uridylation of let-7 precursor MicroRNA. Mol. Cell 32, 276–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Viswanathan S. R., Daley G. Q., Gregory R. I. (2008) Selective blockade of microRNA processing by Lin28. Science 320, 97–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heo I., Joo C., Kim Y. K., Ha M., Yoon M. J., Cho J., Yeom K. H., Han J., Kim V. N. (2009) TUT4 in concert with Lin28 suppresses microRNA biogenesis through pre-microRNA uridylation. Cell 138, 696–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morlando M., Ballarino M., Gromak N., Pagano F., Bozzoni I., Proudfoot N. J. (2008) Primary microRNA transcripts are processed co-transcriptionally. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 902–909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pawlicki J. M., Steitz J. A. (2008) Primary microRNA transcript retention at sites of transcription leads to enhanced microRNA production. J. Cell Biol. 182, 61–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matsushita K., Takeuchi O., Standley D. M., Kumagai Y., Kawagoe T., Miyake T., Satoh T., Kato H., Tsujimura T., Nakamura H., Akira S. (2009) Zc3h12a is an RNase essential for controlling immune responses by regulating mRNA decay. Nature 458, 1185–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liang J., Saad Y., Lei T., Wang J., Qi D., Yang Q., Kolattukudy P. E., Fu M. (2010) MCP-induced protein 1 deubiquitinates TRAF proteins and negatively regulates JNK and NF-κB signaling. J. Exp. Med. 207, 2959–2973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Suzuki H. I., Arase M., Matsuyama H., Choi Y. L., Ueno T., Mano H., Sugimoto K., Miyazono K. (2011) MCPIP1 ribonuclease antagonizes dicer and terminates microRNA biogenesis through precursor microRNA degradation. Mol. Cell 44, 424–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mattioli M., Reichlin M. (1974) Heterogeneity of RNA protein antigens reactive with sera of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Description of a cytoplasmic nonribosomal antigen. Arthritis Rheum. 17, 421–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wolin S. L., Cedervall T. (2002) The La protein. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 375–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chakshusmathi G., Kim S. D., Rubinson D. A., Wolin S. L. (2003) A La protein requirement for efficient pre-tRNA folding. EMBO J. 22, 6562–6572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fan H., Goodier J. L., Chamberlain J. R., Engelke D. R., Maraia R. J. (1998) 5′ processing of tRNA precursors can be modulated by the human La antigen phosphoprotein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 3201–3211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yoo C. J., Wolin S. L. (1997) The La protein in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. A conserved yet dispensable phosphoprotein that functions in tRNA maturation. Cell 89, 393–402 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bousquet-Antonelli C., Deragon J. M. (2009) A comprehensive analysis of the La-motif protein superfamily. RNA 15, 750–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alfano C., Sanfelice D., Babon J., Kelly G., Jacks A., Curry S., Conte M. R. (2004) Structural analysis of cooperative RNA binding by the La motif and central RRM domain of human La protein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kotik-Kogan O., Valentine E. R., Sanfelice D., Conte M. R., Curry S. (2008) Structural analysis reveals conformational plasticity in the recognition of RNA 3′ ends by the human La protein. Structure 16, 852–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Teplova M., Yuan Y. R., Phan A. T., Malinina L., Ilin S., Teplov A., Patel D. J. (2006) Structural basis for recognition and sequestration of UUU(OH) 3′ temini of nascent RNA polymerase III transcripts by La, a rheumatic disease autoantigen. Mol. Cell 21, 75–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Copela L. A., Chakshusmathi G., Sherrer R. L., Wolin S. L. (2006) The La protein functions redundantly with tRNA modification enzymes to ensure tRNA structural stability. RNA 12, 644–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yoo C. J., Wolin S. L. (1994) La proteins from Drosophila melanogaster and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. A yeast homolog of the La autoantigen is dispensable for growth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 5412–5424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Park J. M., Kohn M. J., Bruinsma M. W., Vech C., Intine R. V., Fuhrmann S., Grinberg A., Mukherjee I., Love P. E., Ko M. S., DePamphilis M. L., Maraia R. J. (2006) The multifunctional RNA-binding protein La is required for mouse development and for the establishment of embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 1445–1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bai C., Tolias P. P. (2000) Genetic analysis of a La homolog in Drosophila melanogaster. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 1078–1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Han J., Lee Y., Yeom K. H., Kim Y. K., Jin H., Kim V. N. (2004) The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev. 18, 3016–3027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Liu Y., Ye X., Jiang F., Liang C., Chen D., Peng J., Kinch L. N., Grishin N. V., Liu Q. (2009) C3PO, an endoribonuclease that promotes RNAi by facilitating RISC activation. Science 325, 750–753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Niranjanakumari S., Lasda E., Brazas R., Garcia-Blanco M. A. (2002) Reversible cross-linking combined with immunoprecipitation to study RNA-protein interactions in vivo. Methods 26, 182–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Liu X., Park J. K., Jiang F., Liu Y., McKearin D., Liu Q. (2007) Dicer-1, but not Loquacious, is critical for assembly of miRNA-induced silencing complexes. RNA 13, 2324–2329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V. K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B. L., Gillette M. A., Paulovich A., Pomeroy S. L., Golub T. R., Lander E. S., Mesirov J. P. (2005) Gene set enrichment analysis. A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15545–15550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Martello G., Rosato A., Ferrari F., Manfrin A., Cordenonsi M., Dupont S., Enzo E., Guzzardo V., Rondina M., Spruce T., Parenti A. R., Daidone M. G., Bicciato S., Piccolo S. (2010) A MicroRNA targeting Dicer for metastasis control. Cell 141, 1195–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Desmedt C., Piette F., Loi S., Wang Y., Lallemand F., Haibe-Kains B., Viale G., Delorenzi M., Zhang Y., d'Assignies M. S., Bergh J., Lidereau R., Ellis P., Harris A. L., Klijn J. G., Foekens J. A., Cardoso F., Piccart M. J., Buyse M., Sotiriou C. (2007) Strong time dependence of the 76-gene prognostic signature for node-negative breast cancer patients in the TRANSBIG multicenter independent validation series. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 3207–3214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. van de Vijver M. J., He Y. D., van't Veer L. J., Dai H., Hart A. A., Voskuil D. W., Schreiber G. J., Peterse J. L., Roberts C., Marton M. J., Parrish M., Atsma D., Witteveen A., Glas A., Delahaye L., van der Velde T., Bartelink H., Rodenhuis S., Rutgers E. T., Friend S. H., Bernards R. (2002) A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 1999–2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hatfield S. D., Shcherbata H. R., Fischer K. A., Nakahara K., Carthew R. W., Ruohola-Baker H. (2005) Stem cell division is regulated by the microRNA pathway. Nature 435, 974–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kanellopoulou C., Muljo S. A., Kung A. L., Ganesan S., Drapkin R., Jenuwein T., Livingston D. M., Rajewsky K. (2005) Dicer-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells are defective in differentiation and centromeric silencing. Genes Dev. 19, 489–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Murchison E. P., Partridge J. F., Tam O. H., Cheloufi S., Hannon G. J. (2005) Characterization of Dicer-deficient murine embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 12135–12140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Park J. K., Liu X., Strauss T. J., McKearin D. M., Liu Q. (2007) The miRNA pathway intrinsically controls self-renewal of Drosophila germline stem cells. Curr. Biol. 17, 533–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang Y., Medvid R., Melton C., Jaenisch R., Blelloch R. (2007) DGCR8 is essential for microRNA biogenesis and silencing of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat. Genet. 39, 380–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Merritt W. M., Lin Y. G., Han L. Y., Kamat A. A., Spannuth W. A., Schmandt R., Urbauer D., Pennacchio L. A., Cheng J. F., Nick A. M., Deavers M. T., Mourad-Zeidan A., Wang H., Mueller P., Lenburg M. E., Gray J. W., Mok S., Birrer M. J., Lopez-Berestein G., Coleman R. L., Bar-Eli M., Sood A. K. (2010) Dicer, Drosha, and outcomes in patients with ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 2641–2650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Melo S. A., Ropero S., Moutinho C., Aaltonen L. A., Yamamoto H., Calin G. A., Rossi S., Fernandez A. F., Carneiro F., Oliveira C., Ferreira B., Liu C. G., Villanueva A., Capella G., Schwartz S., Jr., Shiekhattar R., Esteller M. (2009) A TARBP2 mutation in human cancer impairs microRNA processing and Dicer function. Nat. Genet. 41, 365–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 62. Melo S. A., Moutinho C., Ropero S., Calin G. A., Rossi S., Spizzo R., Fernandez A. F., Davalos V., Villanueva A., Montoya G., Yamamoto H., Schwartz S., Jr., Esteller M. (2010) A genetic defect in exportin-5 traps precursor microRNAs in the nucleus of cancer cells. Cancer Cell 18, 303–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Taganov K. D., Boldin M. P., Baltimore D. (2007) MicroRNAs and immunity. Tiny players in a big field. Immunity 26, 133–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pruijn G. J. (2006) The RNA interference pathway. A new target for autoimmunity. Arthritis Res. Ther. 8, 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jakymiw A., Ikeda K., Fritzler M. J., Reeves W. H., Satoh M., Chan E. K. (2006) Autoimmune targeting of key components of RNA interference. Arthritis Res. Ther. 8, R87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Martino L., Pennell S., Kelly G., Bui T. T. T., Kotik-Kogan O., Smerdon S. J., Drake A. F., Curry S., Conte M. R. (2012) Analysis of the interaction with the hepatitis C virus mRNA reveals an alternative mode of RNA recognition by the human La protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 1381–1394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]