Background: The intensity and duration of phosphorylation levels of R-Smads are required for precise control of BMP signaling.

Results: MTMR4 associated with and dephosphorylated the activated R-Smads in cytoplasm.

Conclusion: MTMR4 attenuates BMP signaling via its DUSP activity.

Significance: This study describes a novel role of MTMR4 as a negative modulator essentially involved in homeostatic BMP signaling.

Keywords: Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP), Drosophila, Phosphatase, Serine Threonine Protein Phosphatase, Signal Transduction, MTMR4, Smads

Abstract

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) signaling essentially regulates a wide range of biological responses. Although multiple regulators at different layers of the receptor-effectors axis have been identified, the mechanisms of homeostatic BMP signaling remain vague. Herein we demonstrated that myotubularin-related protein 4 (MTMR4), a FYVE domain-containing dual-specificity protein phosphatase (DUSP), preferentially associated with and dephosphorylated the activated R-Smads in cytoplasm, which is a critical checkpoint in BMP signal transduction. Therefore, transcriptional activation by BMPs was tightly controlled by the expression level and the intrinsic phosphatase activity of MTMR4. More profoundly, ectopic expression of MTMR4 or its Drosophila homolog CG3632 genetically interacted with BMP/Dpp signaling axis in regulation of the vein development of Drosophila wings. By doing so, MTMR4 could interact with and dephosphorylate Mothers against Decapentaplegic (Mad), the sole R-Smad in Drosophila BMP pathway, and hence affected the target genes expression of Mad. In conclusion, this study has suggested that MTMR4 is a necessary negative modulator for the homeostasis of BMP/Dpp signaling.

Introduction

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs)4 belong to the TGFβ super family, and have a diverse array of functions in the development of mutilcellular organisms (1). Recent evidence has also shown that BMP signaling regulates the self-renewal and proliferation of stem cells (2, 3), and prolongs the lifespan of stem cells (4). The hierarchy and function of BMP signaling pathway are highly conserved in the metazoan organisms (5–7). After binding to BMPs, the serine-threonine kinase transmembrane receptors activate a signal cascade through intracellular regulatory Smad proteins (R-Smads). Phosphorylated R-Smads form a ternary complex with the common partner Smad (Co-Smad) and translocate to the nucleus to activate transcription of a spectrum of effector genes (8). There are two members of BMPs in Drosophila. Decapentaplegic (Dpp) is the homolog of BMP2/4 (9) and glass bottom boat (Gbb) is the homolog of BMP5/6/7 (10). These two Drosophila BMP members play a major role in cell proliferation and/or cell survival (11), and are required for the vein formation (12) during Drosophila wings development (13). Thickveins (tkv) serves as the type I BMP receptor that mediates Dpp signaling during wing morphogenesis and other stages of fly development (11, 14, 15), and Mathers against Decapentaplegic (Mad) turns out as the sole R-Smad in BMP signaling of Drosophila (16, 17).

The intensity and duration of phosphorylation levels of BMP receptors and R-Smads are required for precise control of BMP signaling (18, 19). A few nuclear phosphatases for R-Smads have thus far been identified, such as pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase (PDP), PPM1A (protein phosphatase magnesium-dependent 1A), and small C-terminal domain phosphatase (SCP2/Os4) (19–21). However, the existence and roles of cytoplasmic phosphatases have remained elusive; it has been recently revealed by us that a new endosomal phosphatase, myotubularin-related protein 4 (MTMR4), can specifically temper TGFβ signaling (22). MTMR4 belongs to myotubularin family and contains tyrosine/dual-specificity phosphatase (DUSP) activity (23) and functions in early endosomes (22, 24). MTMR4 specifically interacts with and dephosphorylates the activated R-Smads to keep TGFβ signaling in homeostasis (22). It therefore would be highly interesting to determine whether MTMR4 is also critically involved in BMP signaling.

In this study, we managed to demonstrate that MTMR4 is also an essential negative regulator of BMP signaling pathway. MTMR4 directly bound to and dephosphorylated the activated Smad1 via the DUSP enzymatic domain. Thus, overexpression of MTMR4 inhibited BMP-induced gene expression by accelerating Smad1 dephosphorylation, whereas knockdown of MTMR4 by siRNA enhanced BMP signaling with sustained Smad1 phosphorylation. We further demonstrated in vivo that MTMR4 and its Drosophila homologous gene CG3632 critically modulated the vein formation of Drosophila wings, by specifically targeting Mad activation. Therefore, MTMR4 may possess a conserved attenuator activity on R-Smads activation that is required for homeostatic BMP/Dpp signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

Expression of plasmids for YFP-tagged MTMR4 and its truncations/point mutation (MTMR4C407S) has been previously described (22). pCMV-Flag-Smad1, pCMV-HA-Smad5, GCCG-luc, and BRE-luc were described elsewhere (19, 25, 26). HA-MAD (27) was kindly provided by Dr Xin-hua Feng. The various truncations of Smad1 (pCMV-Flag- Smad1N/L/C) were obtained by PCR and cloned inbetween BglII (5′) and KpnI (3′) sites of the pCMV-HA-Flag vector derived from pCMV-HA (Clontech, Japan). Each derivative clone was verified by DNA sequencing analysis. pAGW-MTMR4 was constructed by the Gateway cloning technique (Invitrogen).

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Reporter Assays

HEK293T, HeLa, and HepG2 cells were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen), and S2 cells were cultured in Schneider's insect medium (Sigma). All media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Invitrogen), 1% penicillin, and streptomycin (Invitrogen). The lipofectamine method (Invitrogen) was used to transfect HeLa and Drosophila S2 cells and calcium-phosphate method for 293T cells. Transient co-transfection and Luciferase reporter assays were performed as previously described (28). Data represent the average of triplicate experiments (mean ± S.D.). Recombinant BMP2 and Dpp ligand proteins were purchased from R&D (Minneapolis, MN).

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

Immunoprecipitation was carried out exactly as previously described (22). Antibodies against pSmad1/5/8 (phosphor-SXS) and Smad1 were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). GFP antibody was from Zymed Laboratories Inc. (San Diego, CA) and MTMR4 antibody from Abgent (San Diego, CA). Flag and β-actin antibodies were from Sigma.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) from HeLa or S2 cells treated with or without BMP2/DPP for the times indicated. Quantitative RT-PCR (ABI7500, Invitrogen) was carried out as previously described (22) using GAPDH or rp49 as the internal controls, respectively. Primer sequences for p21, forward: 5′-GGCAGACCAG CATGACAGATT-3′; reverse: 5′-GCGGATTA GGGCTTCCTCTT-3′; Id1, forward: 5′-AACCGCAAGGTGAGCAAGGTGG-3′; reverse: 5′-ACGCATGCCGCCTCGGC-3′; GAPDH, forward: 5′-CTGGGCTACACTGAGCACCAG-3′; reverse: 5′-CCAGCGTCAAAGGTGGAG-3′; Brinker, forward: 5′-CGGCAATCAACGAACAAAGG-3′; reverse: 5′-TGAAAGCTGCTGGTGATCGA-3′; Omb, forward: 5′-AAGTGCGTAAAGTGTGGAGT-3′; reverse: 5′-ATATTCTTTGGACCTCCCAC-3′; Rp49, forward: 5′-AGATCGTGAAGAAGCGCACCAAG-3′; reverse: 5′-CACCAGGAACTTCTTGAATCCGG-3′. Data represent the average of three independent experiments (mean ± S.D.).

RNA Interference

The 21-nucleotide siRNA duplexes targeting MTMR4 and scrambled siRNA were synthesized and purified as previously described (22). The efficiency was measured by Western blot using MTMR4 antibody.

Fluorescence Microscopy

S2 cells in 35-mm plates were transfected with various RFP/GFP fusion plasmids indicated (1 μg each). After 36 h, the transfectants were seeded at 80% confluence on glass bottom tissue culture dishes and serum-starved overnight. Cells were then exposed to Dpp (40 ng/ml) for 2 h before fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Images were taken using a Zeiss fluorescent microscope (Observer Z1, Germany) and analyzed by Imag J software. DAPI (1:1000 dilution) was used to counter stain the nuclei.

Drosophila Stocks and Experimental Genotypes

All stocks were cultured at room temperature in standard cornmeal/molasses/agar media. The Drosophila stocks used in this study were as follows: UAS-gbb and UAS-dpp (described in Flybase), UAS-tkvRNAi (II), UAS-tkvRNAi (III), and vg-gal4 (kind gifts from Matthew Gibson, Stowers Institute for Medical Research). The Gateway cloning system (Invitrogen) was used to generate UAS-CG3632, UAS-MTMR4, and UAS-MTMR4C407S constructs according to manufacturer's manual, after cg3632, mtmr4, and mtmr4-C407S gene fragments were PCR amplified. Different plasmid constructs were injected into w1118 embryos to generate transgenic lines. To determine whether a moderate reduction of BMP signaling and overexpression of MTMR4 has any effect on Drosophila wing patterning, the vg-gal4 virgins were crossed with UAS-tkvRNAi (II), UAS-tkv RNAi (III), UAS-CG3632, UAS-MTMR4, UAS- MTMR4C407S, and w1118 males. To investigate how gbb overexpression affects wing pattern formation, the vg-gal4 virgins were crossed with UAS-gbb males. To test whether MTMR4, MTMR4-C407S could interfere with BMP signaling, the vg-gal4 virgins were crossed with UAS-CG3632/Cyo;UAS-tkvRNAi(III)/TM6, UAS-MTMR4/Cyo;UAS-tkvRNAi(III)/TM6, UAS-MTMR4C407S/Cyo;UAS-tkvRNAi(III)/TM6, UAS-gbb/FM7;UAS-CG3632/Cyo, UAS-gbb/FM7;UAS-MTMR4/Cyo, UAS-gbb/FM7;UAS-MTMR4C407S/Cyo males. All wings demonstrated here are from adult females and were mounted in Hoyer's medium.

RESULTS

MTMR4 Attenuates BMP Signaling

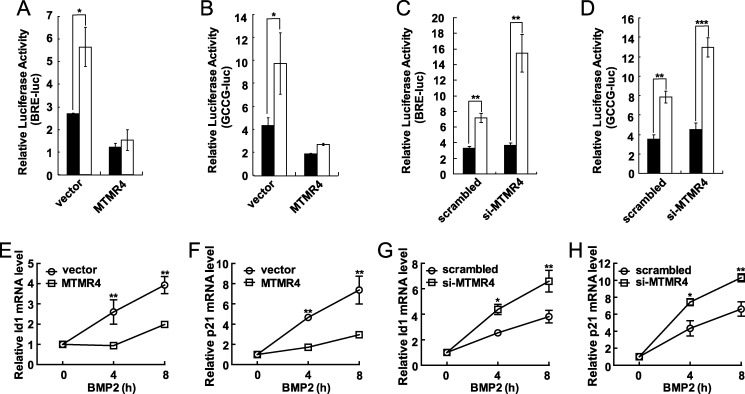

Because BMP and TGFβ both belong to TGFβ superfamily, that MTMR4 attenuates R-Smads activation in TGFβ pathway (22) prompted us to test whether the conserved DUSP activity of MTMR4 would also play a role in BMP signaling. To test this hypothesis, first we transiently transfected two BMP-responsive luciferase reporters in HeLa cells, namely BRE-lux and GCCG-lux which contained multiple BMP-specific R-Smads binding elements GCCG (25, 29). The R-Smad responsive reporter activities increased by ∼2.5-fold post-BMP2 treatment for 16 h, which was effectively suppressed by co-expressed MTMR4 (Fig. 1, A and B; supplemental Fig. S1A for expression levels of MTMR4 in transfectants). This result thus suggested that MTMR4 plays an inhibitory role in BMP signaling. Moreover, when we knocked down the endogenous MTMR4 gene expression by siRNA (supplemental Fig. S1B for the knockdown efficiency), as expected, cells became more responsive to BMP2, as demonstrated by much higher BRE/GCCG reporter activities than those treated with scrambled RNAi (Fig. 1, C and D). Therefore, MTMR4 would be required to attenuate BMP signaling. To substantiate this notion, we went on to further test whether MTMR4 affects the expression of BMP target genes. For this purpose, we examine the transcriptional levels of Id-1, a regulator of cell proliferation and differentiation (26, 30), and p21, a cell cycle inhibitor (31), both of which are well-known target genes of BMP/R-Smads signaling. Quantitative PCR analysis showed that the expression levels of Id1 and p21 was effectively suppressed by overexpressed MTMR4 (Fig. 1, E and F) and enhanced by knockdown of endogenous MTMR4 (Fig. 1, G and H) after BMP2 stimulation. Taken together, these results suggested that MTMR4 could attenuate BMP signaling, possibly via directly interrogating R-Smad activation.

FIGURE 1.

MTMR4 inhibits BMP2-induced reporter activities and target genes activation. A and B, ectopic expression of MTMR4 inhibited BMP2 signaling. HeLa cells were co-transfected with pEGFP vector or pEYFP-MTMR4 and BRE-Luc or GCCG-Luc reporter. pEGFP parental vector was used as a control. BMP2 (100 ng/ml) was added for 12 h before luciferase activities were measured. C and D, knockdown of MTMR4 in HeLa cells enhanced BMP2 signaling. HeLa cells were transfected with RNAi for MTMR4 or scrambled control for 72 h before cells were treated with BMP2 (100 ng/ml) for additional 12 h. All reporter assays were normalized to co-expressed Renilla activities. ■, w/o BMP2 stimulation; □, with BMP2 stimulation. E–H, MTMR4 affected BMP2 target genes expression. Hela cells were transfected with pEYFP-MTMR4 (E and F) for 48 h or MTMR4 RNAi (44) for 72 h before treated with BMP2 (100 ng/ml) for 0, 4, 8 h. Quantitative RT-PCR were performed for induction of Id1 (E, G) and p21 (F, H) gene expression. All data represent the average of triplicate independent experiments (mean ± S.E.). ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05, Student's t test.

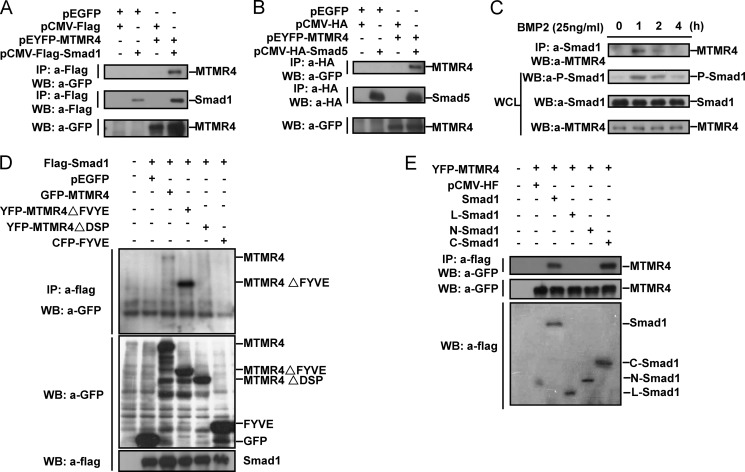

MTMR4 Physically Interacts with Smad1/5

To validate the aforementioned hypothesis, we set out to examine whether MTMR4 interacts with those R-Smads of BMP pathway. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed that YFP-MTMR4 transiently expressed in 293T cells readily associated with Flag-Smad1 (Fig. 2A) or HA-Smad5 (Fig. 2B), two of R-Smads in BMP signaling pathway. Such intermolecular interactions also occurred under physiological conditions since the endogenous MTMR4 and Smad1 associated with each other, and interestingly enough, only after BMP2 stimulation (Fig. 2C). Moreover, the amount of MTMR4 associated with Smad1 reduced proportionally to the phosphorylation levels of Smad1, suggesting that MTMR4 might preferentially interact with the activated Smad1 (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

MTMR4 interacted with R-Smad proteins of BMP signaling. A and B, MTMR4 interacted with Smad1 and Smad5. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with pEYFP-MTMR4 and pCMV-Flag-Smad1 (A) or pCMV-HA-Smad5 (B) for 48h. Indicated parental vectors were transfected as negative control. YFP-MTMR4 was co-immunoprecipitated with Flag (A) or HA (B) antibody and visualized with GFP antibody. Protein expression levels were verified by Flag, HA, or GFP antibodies as indicated. C, endogenous MTMR4 and Smad1interacted depending upon BMP2 stimulation. HepG2 cells at 90% confluency were treated with BMP2 (25 ng/ml) for indicated time. Whole cell lysates (WCL, 300 μg total proteins) were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-Smad1 antibody. MTMR4 antibody was then used for immunoblotting of MTMR4. The WCL was immunoblotted with phosphor-Smad1, Smad1 or MTMR4 anitbody, respectively, for loading control. D, DUSP domain of MTMR4 was required for interaction with Smad1. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with pCMV-Flag-Smad1 and pEYFP-MTMR4 or its mutant derivatives as indicated for 48 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 Flag antibody and visualized with GFP antibody (top panel). Expression levels of Flag-Smad1 (middle) and YFP-MTMR4 and various mutants (bottom) are also shown. E, MH2 domain of Smad1 was required for interaction with MTMR4. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with pEYFP-MTMR4 and pCMV-Flag-Smad1 or its mutant derivatives as indicated for 48 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 Flag antibody and blotted with anti-GFP antibody (top panel). Expression levels of YFP-MTMR4 (middle) and Flag-Smad1 and various mutants (two bottom panels) are also shown.

To map the regions of contact between MTMR4 and Smad1, we further performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments using an array of truncational mutants of MTMR4 and Smad1 that transiently co-expressed in 293T cells (supplemental Fig. S2, A and B for the scheme of different mutants). The results showed that MTMR4 utilized its N-terminal region (MTMR4ΔFYVE, amino acids 1–591), which contains the conserved DUSP phosphatase domain, to contact Smad1 (Fig. 2D). Reciprocally, the MH2 domain, but not MH1 domain or linker region, of Smad1 was involved in contact with MTMR4 (Fig. 2E). These results suggested that the phosphorylated MH2 domain of Smad1 might serve as a physiological substrate of MTMR4.

MTMR4 Accelerates Smad1 Dephosphorylation

The aforementioned physical interaction between MTMR4 and the activated Smad1 suggested that BMP signaling could be modulated by MTMR4 via targeting Smad1 phosphorylation. To test this hypothesis, HeLa cells were co-transfected with MTMR4 and Smad1, and the phosphorylation status of Smad1 was measured by a phosphor-SXS antibody specific to phosphorylated S463/S465 residues in the MH2 domain of Smad1, which are essential for Smad1 activation (6). In the absence of MTMR4, Smad1 was phosphorylated rapidly, and it reached a peak around 30 min post-BMP2 treatment. Then the phosphorylation levels of Smad1 gradually decayed up to 4 h. Overexpression of MTMR4 did not alter the onset of Smad1 phosphorylation, however, it accelerated Smad1 dephosphorylation just after the peak time (30 min) of BMP2 treatment (Fig. 3A). This enhanced dephosphorylation of Smad1 was not due to its proteasomal degradation, because the levels of Smad1 protein remained the same in the presence or absence of overexpressed MTMR4 (Fig. 3A). Moreover, siRNA knockdown of the endogenous Mtmr4 gene in HeLa cells significantly attenuated Smad1 dephosphorylation when compared with the scrambled siRNA control (Fig. 3B). Consistent with the action of MTMR4 after phosphorylation of Smad1, overexpressed MTMR4 affected little BMP-target gene expression in the early time points and became more inhibitive in the later phase (supplemental Fig. S3). Therefore, these results suggested that MTMR4 control the velocity of Smad1 dephosphorylation, which could serve as a necessary mechanism to keep BMP activation signaling in homeostasis.

FIGURE 3.

MTMR4 accelerated the dephosophorylation of activated Smad1. A, MTMR4 dephosphorylated the activated Smad1. HeLa cells were pre-transfected with YFP-MTMR4 for 48 h before stimulated with BMP2 (100 ng/ml) for indicated time. WCL (30 μg total proteins) was separated by SDS-PAGE and endogenous Smad1 was immunoblotted with phosphor-Smad1 antibody (top panel), Smad1 antibody (middle panel), or anti-GFP antibody for expression of YFP-MTMR4 (bottom panel). B, down-regulation of MTMR4 resulted in sustained Smad1 phosphorylation. The experiment was performed as A, except that cells were transfected with MTMR4-specific siRNA or scrambled siRNA. C, endosomes localized DUSP activity of MTMR4 was responsible for Smad1 dephosphorylation. Hela cells were transiently expressed with pEYFP-MTMR4-C407S or pEYFP-MTMR4-ΔFYVE for 48 h. Immunoblotting was performed as in A to detect Smad1 phosphorylation. Protein loadings for endogenous Smad1 and exogenous YFP-MTMR4/C407S/ΔFYVE were performed as in A. D-E, endosomes localized DUSP activity of MTMR4 was required for Smad1 responsive gene activation. MTMR4-C407S and MTMR4ΔFYVE were transiently expressed in Hela cells as in C, and BRE-luc (D), and GCCG-luc (E) reporter activities were measured as in Fig. 1, A and B. All data represent the average of triplicate independent experiments (mean ± S.E.). ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05, Student's t test.

To further detect the function of MTMR4 in dephosphorylation of Smad1, we then transiently expressed the “phosphatase dead” mutant (MTMR4-C407S) or the mutant defective in early endosome localization (MTMR4ΔFYVE) of MTMR4 (supplemental Fig. S2, A and C for the scheme of different mutants). Measurement of phosphorylation levels of Smad1 upon BMP2 stimulation indicated that neither the onset nor the decay of Smad1 phosphorylation was affected by MTMR4-C407S or MTMR4ΔFYVE (Fig. 3C). Indeed, both BRE and GCCG reporter assays showed that overexpressed MTMR4-C407S or MTMR4ΔFYVE (Fig. 3, D and E) could no longer suppress BMP activation as compared with wild type MTMR4 (Fig. 1, A and B). These results therefore suggested that Smad1 dephosphorylation would require an endosome-localized phosphatase activity of MTMR4.

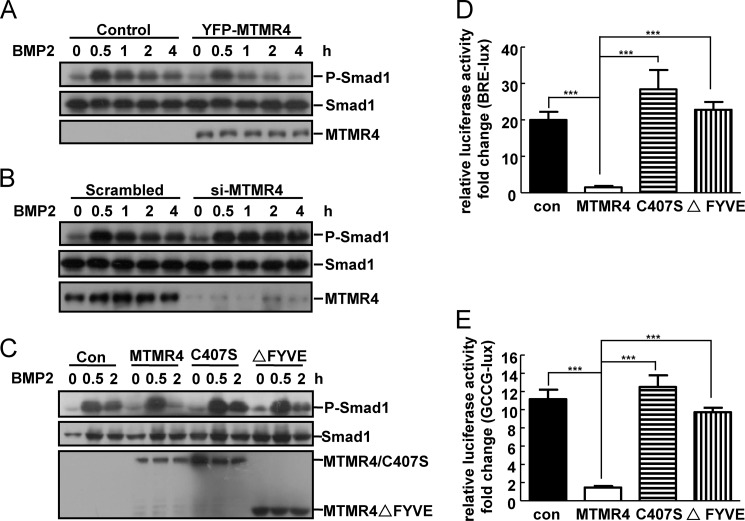

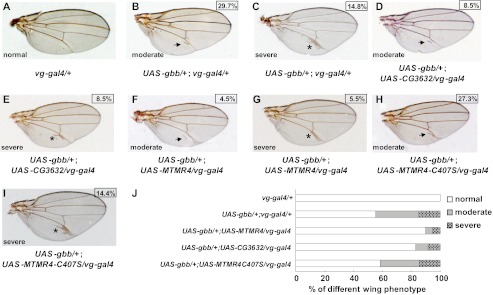

MTMR4 Impacts Vein Formation of Drosophila Wings

The regulatory specificity of BMP signaling can be conveniently scored by visual phenotypes of vein formation in Drosophila wings (13). Thus, to emphasize the biological significance of MTMR4 in the control of BMP signaling in vivo, we then assessed whether ectopically expressed MTMR4 might affect BMP signaling in the development of Drosophila wings. First we tissue-specifically knocked down BMP type I receptor tkv expression in wings by UAS-tkvRNAi driven by vg-gal4 (32). Roughly 63% (n = 189) of vg-gal4/+;UAS-tkvRNAi(III)/+ wings (Fig. 4B) showed branches at posterior crossvein (PCV) compared with normal wings of vg-gal4/+ (Fig. 4A) or UAS-tkvRNAi(III)/+ (supplemental Fig. S4A) controls (Fig. 4J for statistical analysis). The same branching phenotype was obtained in another independent strain, UAS-tkvRNAi(II)/vg-gal4 (81% (n = 200), supplemental Fig. S4B, F for representative phenotype). These results would represent the first line of evidence that tkv was required for vein development in wings. We then generated three lines of transgenic flies, UAS-MTMR4, UAS-MTMR4-C407S, and UAS-CG3632, respectively. CG3632 is a Drosophila homologue of MTMR4 that shares all the conserved functional domains including the phosphatase domain (supplemental Fig. S2C) typified for the catalytic subgroup of MTM super family (23). Interestingly, wings containing overexpressed mtmr4 (UAS-MTMR4/vg-gal4) or cg3632 (UAS-CG3632/vg-gal4) also developed the similar branched PCV as to those in tkv knockdown lines, albeit at slightly lower rates (20.6% (n = 126) for UAS-CG3632/vg-gal4 and 24.2% (n = 120) for UAS-MTMR4/vg-gal4, respectively) (Fig. 4, C, D, and J). In contrast, the wings developed normally in the UAS-MTMR4-C407S/vg-gal4 line (Fig. 4E, J, n = 150). The phenotypic similarity in PCV development would suggest that MTMR4 might play a role in tkv signaling, and more importantly, by tempering Dpp activation signaling when MTMR4 was overexpressed.

FIGURE 4.

MTMR4 and CG3632 potentiated Tkv knockdown in the vein formation. A, representative genetic control wing (vg-gal4/+) with normal morphology. Longitudinal veins (L1, L2, L3, L4, and L5), anterior (ACV) and posterior crossveins (PCV) were indicated. B–D, MTMR4 and CG3632 transgenic flies had the similar vein abnormality to Tkv knockdown flies. Representative defective wings of vg-gal4/+; UAS-tkvRNAi(III)/+(n = 189), UAS-CG3632/vg-gal4 (n = 126), and UAS-MTMR4/vg-gal4 (n = 120) flies were shown, and the aberrant branches at PCV were marked by asterisks. Corresponding branching percentage derived from Fig. 3J are shown in boxes. E, loss of DUSP activity of MTMR4 failed to affect vein development. The representative wing of UAS-MTMR4-C407S/vg-gal4 (n = 150) flies were shown, and the corresponding percentage of normal veins is shown in the box. F–H, MTMR4 and CG3632 enhanced vein abnormality of Tkv knockdown flies. Representative enhanced defective wings of UAS-CG3632/vg-gal4; UAS-tkvRNAi(III)/+ (n = 110) and UAS-MTMR4/vg-gal4; UAS-tkvRNAi(III)/+ (n = 105) flies were shown for branches at PCV (asterisk), partial duplicated vein of L5 (white arrowhead), and gaps at L5 vein junctions of the margin (black arrowhead). The representative wing of UAS-MTMR4/vg-gal4; UAS-tkvRNAi(III)/+ (n = 105) flies with severe vein abnormality was shown in H for an increased number and places of branches (asterisks) and duplications (white arrowheads). Corresponding enhanced or severe percentage scores derived from Fig. 3J are shown in boxes. I, loss of DUSP activity of MTMR4 partially rescue Tkv knockdown in vein development. The representative defective wing of UAS-MTMR4-C407S/vg-gal4; UAS-tkvRNAi(III)/+ flies (n = 129) exhibit fewer branched PCV (asterisks) and none enhanced or severe phenotypes. Corresponding branching percentage derived from Fig. 3J is shown in the box. J, statistics of various phenotypes of vein development of all flies in A–I is plotted in the bar graph.

To substantiate this notion, we went on to assess whether overexpression of MTMR4 or CG3632 could synergize wing patterning deficiency in the background of the reduced tkv expression. As expected, vg-gal4-driven simultaneous expression of CG3632 and tkvRNAi(III) in wings (UAS-CG3632/vg-gal4; UAS-tkvRNAi(III)/+) caused 51.8% branched veins in PCV (n = 110, supplemental Fig. S5A). More profoundly, 14% showed intense deformity (classified as “enhanced” phenotype) with partial duplications and gaps (Fig. 4, F, J, and supplemental Fig. S5B). Similarly, UAS-MTMR4/vg-gal4; UAS-tkvRNAi (III)/+ wings not only had the branched PCV (55.2%, n = 105, supplemental Fig. S5C) and enhanced phenotype (18.1%, n = 105, Fig. 4, G and J and supplemental Fig. S5D), but also displayed more severe deformation (4.8%, n = 105) with longer branches at PCV and L2 and partial duplications of L2 and L3 (Fig. 4, H and J and supplemental Fig. S5E) (classified as “severe” phenotype). To the contrary, only 25.8% (n = 129) UAS-MTMR4-C407S/vg-gal4; UAS-tkvRNAi(III)/+ wings exhibited the branched PCV (Fig. 4, I and J), a much lower rate than that in vg-gal4/+; UAS-tkvRNAi(III)/+ line (63%, Fig. 4, B and J). Provided that MTMR family proteins usually homo- or heterodimerize for function (33), a possible explanation could be that the null mutation of DUSP catalytic site (MTMR4-C407S) might inactivate the endogenous CG3632, which led to constitutive activation of R-Smads to partially rescue tkv deficiency. That overexpressed MTMR4 or CG3632 potentiated Tkv deficiency in wing development would suggest that these DUSPs could temper otherwise overactivated BMP signaling.

To address this issue, we first analyzed vein development with BMP signaling over-activated in wings by tissue-specific expression of Dpp or Gbb. To our disappointment, all of vg-gal4/+; UAS-dpp/+ lines showed too severe phenotypes with round and blistered adult wings, probably due to the lack of adhesion of the dorsal and ventral wing compartments (supplemental Fig. S6B), to further analyze vein formation. Fortunately, UAS-gbb/+; vg-gal4/+ strain was relatively milder with 29.7% (n = 155) wings showing moderate (ectopic vein branches near PCV and L5, Fig. 5, B and J) and 14.8% (n = 155) wings having severe defects (ectopic vein tissues nearby L5; Fig. 5, C and J and supplemental Fig. S6D). The ectopic vein tissue may be caused by abnormal cell proliferation induced by Gbb (34). We then co-expressed UAS-gbb with UAS-CG3632 or UAS-MTMR4 in wings using vg-gal4 driver. The percentage of moderate defective wings was reduced from 29.7% (n = 155) in UAS-gbb/+;vg-gal4/+ to 8.5% (n = 106) in UAS-gbb/+; UAS-CG3632/vg-gal4, and 4.5% (n = 110) in UAS-gbb/+; UAS-MTMR4/vg-gal4, respectively (Fig. 5, B, D, F, and J). Accordingly, the severe percentage was down from 14.8% (n = 155) to 8.5% (n = 106) and 5.5% (n = 110), respectively (Fig. 5, C, E, G, and J). In contrast, ectopically co-expression of MTMR4-C407S (UAS-gbb/+; UAS-MTMR4- C407S/vg-gal4) barely interfered with the Gbb overexpression phenotypes (27.3% (n = 139) with moderate defects (Fig. 5, H and J) and 14.4% severe defects (Fig. 5, I and J)). Together, these results suggested that MTMR4/CG3632 might be a functional component of BMP signaling and negatively controlled BMP/Tkv activation using its DUSP activity.

FIGURE 5.

MTMR4 and CG3632 ameliorate vein defectiveness induced by forced Gbb signaling. A, representative genetic control wing (vg-gal4/+) with normal morphology. B and C, overexpression of Gbb caused deformity of vein development. Representative wings of UAS-gbb/+; vg-gal4/+ flies (n = 155) showed moderate (B) and severe (C) vein defects. D and E, co-expression of CG3632 antagonized Gbb. Representative moderate (D) and severe (E) defective wings of UAS-gbb/+; UAS-CG3632/vg-gal4 (n = 106) flies were shown. F and G, co-expression of MTMR4 antagonized Gbb. Representative moderate (F) and severe (G) defective wings of UAS-gbb/+; UAS-MTMR4/vg-gal4 (n = 110) flies are shown. H and I, loss of DUSP activity of MTMR4 failed to antagonize Gbb. Representative wings of UAS-gbb/+; UAS-MTMR4-C407S/vg-gal4 flies (n = 139) are shown for moderate (H) and severe (I) vein deformity. In the aforementioned figures, the black arrow indicates ectopic vein branches near PCV and L5, and the asterisk indicated ectopic vein tissue. Corresponding moderate or severe percentage scores derived from Fig. 4J are shown in boxes. J, statistics of various phenotypes of vein development of all flies in A–I is plotted in the bar graph.

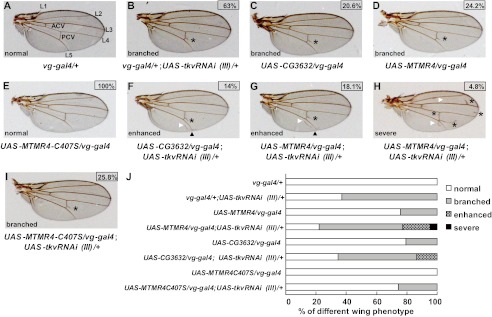

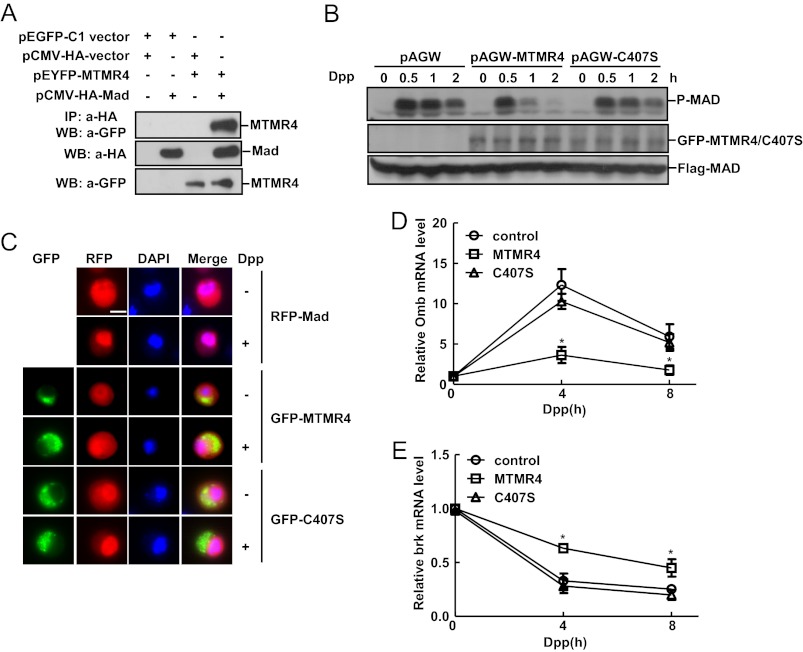

MTMR4 Is a Conserved BMP Attenuator

The genetic interaction between MTMR4 and Gbb/Tkv signaling pathway promoted us to test whether MTMR4 could interact with Mad, the only R-Smad in Drosophila BMP pathway. We transiently co-transfected HEK293T cells with YFP-MTMR4 and HA-Mad. Co-immunoprecipitation showed that there was indeed a intermolecular interaction between Mad and MTMR4 (Fig. 6A). We then analyzed whether the phosphorylation levels of the endogenous Mad was affected by MTMR4 in Drosophila S2 cells. Immunoblotting with a phosphor-Smad1 antibody showed that Mad phosphorylation peaked at 30 min after Dpp treatment of S2 cells, and gradually decreased till 2 h (Fig. 6B). Overexpression of MTMR4 carried by a Drosophila expression vector (pAGW-MTMR4) did not apparently affect the onset of Mad phosphorylation. However, it enhanced Mad dephosphorylation in response to Dpp stimulation (Fig. 6B). Co-transfection of the DUSP null mutant of MTMR4 (pAGW-C407S), as expected, failed to alter the activation kinetics of Mad (Fig. 6B). In agreement with the effect of MTMR4 on Mad dephosphorylation, fluorescent microscopy showed that nuclear translocation of RFP-Mad in response to Dpp stimulation (Fig. 6C, top two panels) was inhibited by co-expressed GFP-MTMR4 (middle two panels), but not by GFP- C407S (bottom two panels) in S2 cells. Finally, previous studies have established that gene expression of Drosophila optomotor-blind (omb) is induced by Dpp (35), while brinker (brk) is suppressed by Dpp (36). Overexpression of MTMR4, but not MTMR4-C407S, apparently inhibited omb (Fig. 6D and supplemental Fig. S7B) and promoted brk (Fig. 6E and supplemental Fig. S7A) gene expression, respectively, when S2 cells were treated with Dpp. Therefore, these results suggested that human MTMR4 possessed a conserved phosphatase activity on R-Smads including Drosophila Mad, and more importantly, was able to modulate BMP signaling homeostasis via targeting the activated Smad1 in mammalian cells or Mad in Drosophila cells.

FIGURE 6.

MTMR4 interacts with Drosophila MAD and inhibits Dpp signaling. A, MTMR4 interacted with Mad. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with pCMV-HA-Mad and pEYFP-MTMR4, with each parental expression vectors as control. YFP-MTMR4 was co-immunoprecipitated with HA antibody and visualized by immunoblotting with GFP antibody (top panel). Protein expression levels were verified by anti-HA (middle) or -GFP (bottom) antibodies, respectively. B, MTMR4 dephosphorylated Mad in S2 cells. S2 cells were transiently co-transfected with pAC5.1-FLAG-Mad and pAGW parental vector, or pAGW-MTMR4, pAGW-MTMR4-C407S for 48 h. Dpp (40 ng/ml) was then added for indicated time. Phosphorylation of Mad was detected by immunoblotting with phosphor-Smad1 antibody (top panels). Expression levels of GFP-MTMR4, GFP-MTMR4-C407S, and Flag-Mad was verified with GFP (middle panels) and Flag (bottom panels) antibodies. C, DUSP activity of MTMR4 attenuated nuclear translocation of Mad. S2 cells were transiently co-expressed with RFP-Mad and GFP-MTMR4 or GFP-MTMR4- C407S for 48 h before Dpp (40 ng/ml) was added for an additional 2 h. Mad or MTMR4 was visualized under fluorescent microscopy using RFP and GFP channels, respectively. Scale bar: 5 μm. D and E, MTMR4 affected expression of Dpp target genes. S2 cells were transiently overexpressed with MTMR4 or MTMR4-C407S for 48 h. Dpp (40 ng/ml) was added for the indicated time before Omb (D) and brk (E) mRNA were measured by quantitative RT-PCR. All data represent the average of triplicate independent experiments (mean ± S.E.). ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05, Student's t test.

DISCUSSION

Homeostasis of BMP signaling is critical for numerous biological processes. Among various modulators, phosphorylation-dephosphorylation of R-Smads provides undoubtedly efficient fine tuning. The observations in this work suggest that MTMR4/CG3632 might serve as a critical endosomal phosphatase that controls activation status of R-Smads/Mad in the BMP signaling pathway. MTMR4/CG3632 probably binds to the phosphorylated SXS-motif of R-Smads, and such physical proximity allows DUSP domain to dephosphorylate the activated R-Smads/Mad and consequently, attenuate transcriptional activation of target genes of BMP/Dpp. Intriguingly, just because MTMR4 is early endosome localized, the physical constrain would prohibit MTMR4 from affecting the phosphorylation of R-Smads/Mad in cytosol, or the subsequent translocation and accumulation of phophorylated R-Smads/Mad in endosomes. The supportive evidence was shown by observation that Smad1 or Mad phosphorylation occurred normally (30 min after BMP2/Dpp stimulation) even in the presence of overexpressed MTMR4. Thus, overexpressing MTMR4 does not alter the onset of R-Smads phosphorylation. This indicates that MTMR4 inhibits BMP signaling might be not due to the redistribution of Endofin or related proteins (37) although some MTMs could result in PI3P diminution (33). Such an endosomal attenuator would be advantageous for cells to avoid R-Smads from being overactivated.

BMP activity gradients are critical for Drosophila wing patterning (38, 39). The finding that MTMR4/CG3632 modulated BMP signaling in vein formation strongly suggested that an endosomal DUSP activity would be critical in fine tuning of R-Smad activation status for proper BMP signaling. The precise spectrum of MTMR4/CG3632 target genes remains to be investigated. It is worthy of note that a great proportion of “severe” vein deformity appears in UAS-MTMR4/vg-gal4;UAS-tkvRNAi(III)/+ wings. This is likely that the increased amount of dephosphorylated Mad could activate the canonical Wingless signaling, because Wingless and BMP signal pathways are by large partitioned by the phosphorylation status of Mad (40). Therefore, besides modulating the homeostasis of BMP/Dpp signaling, MTMR4 activity per se has to be tightly controlled to avoid unnecessary crosstalk with other signaling pathways. This speculation has yet to be experimentally confirmed.

The involvement of multiple protein phosphatases at multiple layers of R-Smads activation axis has presented a complex network of TGFβ/BMP signaling. It has become more complicated that some phosphatases are dual functional in both TGFβ and BMP signalings while some are unique to certain pathway. For example, PDP is a Mad-specific phosphatase in Drosophila BMP signaling (21), but with no effect on Smad2 dephosphorylation in TGFβ signaling pathway (21, 41). In contrast, PPM1A can dephosphorylate all R-Smads members in the nucleus (19, 41). MTMR4 functions on both Smad2/3 and Mad, suggesting a PPM1A-like dual player on both TGFβ and BMP pathways. Of course, MTMR4 differs from PPM1A for its subcellular localization, thus provides different checkpoint of BMP activation. Moreover, the new role of MTMR4 on vein development of Drosophila revealed by this study would provide insight into better understanding of hypoxic response that MTMR4 might be involved, such as the malignancy of papillary thyroid cancer (42) and hypertensive fibrogenesis (43).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Xin-hua Feng (Baylor College of Medicine) for kindly providing various constructs, Da-hua Chen (Institute of Zoology, CAS) for S2 cells, Matthew Gibson (Stowers Institute for Medical Research) for vg-gal4 and tkvRNAi fly stocks, Ting Xie (Stowers Institute for Medical Research), Rong-wen Xi (National Institute of Biological Sciences, Beijing), and Dr. Long Miao (Institute of Biophysics, CAS) for technical assistance and stimulating discussions. We are grateful to Dr. Nian Zhan (University of Rochester, NY) for linguistic editing of the manuscript and incisive and helpful comments.

This work was supported in part by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31000403) (to L. P.) and (31200685) (to J. Y.) and from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2011CB946104 and 2011DFG32790) (to H. T.) and (2012CB518900) (to L. P.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1—S7.

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic proteins

- MTMR4

- myotubularin-related protein 4

- DUSP

- dual-specificity protein phosphatase

- Mad

- Mothers against Decapentaplegic

- Dpp

- Decapentaplegic

- Gbb

- glass bottom boat

- PCV

- posterior crossvein

- ACV

- anterior crossvein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hogan B. L. (1996) Bone morphogenetic proteins: multifunctional regulators of vertebrate development. Genes Dev. 10, 1580–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Qi X., Li T. G., Hao J., Hu J., Wang J., Simmons H., Miura S., Mishina Y., Zhao G. Q. (2004) BMP4 supports self-renewal of embryonic stem cells by inhibiting mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 6027–6032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ying Q. L., Nichols J., Chambers I., Smith A. (2003) BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell 115, 281–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pan L., Chen S., Weng C., Call G., Zhu D., Tang H., Zhang N., Xie T. (2007) Stem cell aging is controlled both intrinsically and extrinsically in the Drosophila ovary. Cell stem cell 1, 458–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Attisano L., Wrana J. L. (2002) Signal transduction by the TGF-β superfamily. Science 296, 1646–1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shi Y., Massagué J. (2003) Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 113, 685–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kheradmand F., Folkesson H. G., Shum L., Derynk R., Pytela R., Matthay M. A. (1994) Transforming growth factor-α enhances alveolar epithelial cell repair in a new in vitro model. Am. J. Physiol. 267, L728–L738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miyazono K., Maeda S., Imamura T. (2005) BMP receptor signaling: transcriptional targets, regulation of signals, and signaling cross-talk. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16, 251–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Padgett R. W., St Johnston R. D., Gelbart W. M. (1987) A transcript from a Drosophila pattern gene predicts a protein homologous to the transforming growth factor-β family. Nature 325, 81–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wharton K. A., Thomsen G. H., Gelbart W. M. (1991) Drosophila 60A gene, another transforming growth factor β family member, is closely related to human bone morphogenetic proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88, 9214–9218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burke R., Basler K. (1996) Dpp receptors are autonomously required for cell proliferation in the entire developing Drosophila wing. Development 122, 2261–2269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sturtevant M. A., Bier E. (1995) Analysis of the genetic hierarchy guiding wing vein development in Drosophila. Development 121, 785–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blair S. S. (2007) Wing vein patterning in Drosophila and the analysis of intercellular signaling. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 293–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xie T., Finelli A. L., Padgett R. W. (1994) The Drosophila saxophone gene: a serine-threonine kinase receptor of the TGF-β superfamily. Science 263, 1756–1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brummel T. J., Twombly V., Marqués G., Wrana J. L., Newfeld S. J., Attisano L., Massagué J., O'Connor M. B., Gelbart W. M. (1994) Characterization and relationship of Dpp receptors encoded by the saxophone and thick veins genes in Drosophila. Cell 78, 251–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Raftery L. A., Twombly V., Wharton K., Gelbart W. M. (1995) Genetic screens to identify elements of the decapentaplegic signaling pathway in Drosophila. Genetics 139, 241–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sekelsky J. J., Newfeld S. J., Raftery L. A., Chartoff E. H., Gelbart W. M. (1995) Genetic characterization and cloning of mothers against dpp, a gene required for decapentaplegic function in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 139, 1347–1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Satow R., Kurisaki A., Chan T. C., Hamazaki T. S., Asashima M. (2006) Dullard promotes degradation and dephosphorylation of BMP receptors and is required for neural induction. Dev. Cell 11, 763–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Duan X., Liang Y. Y., Feng X. H., Lin X. (2006) Protein serine/threonine phosphatase PPM1A dephosphorylates Smad1 in the bone morphogenetic protein signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 36526–36532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Knockaert M., Sapkota G., Alarcón C., Massagué J., Brivanlou A. H. (2006) Unique players in the BMP pathway: small C-terminal domain phosphatases dephosphorylate Smad1 to attenuate BMP signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 11940–11945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen H. B., Shen J., Ip Y. T., Xu L. (2006) Identification of phosphatases for Smad in the BMP/DPP pathway. Genes Dev. 20, 648–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yu J., Pan L., Qin X., Chen H., Xu Y., Chen Y., Tang H. (2010) MTMR4 attenuates transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling by dephosphorylating R-Smads in endosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 8454–8462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laporte J., Bedez F., Bolino A., Mandel J. L. (2003) Myotubularins, a large disease-associated family of cooperating catalytically active and inactive phosphoinositides phosphatases. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12 Spec No 2, R285–R292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Naughtin M. J., Sheffield D. A., Rahman P., Hughes W. E., Gurung R., Stow J. L., Nandurkar H. H., Dyson J. M., Mitchell C. A. (2010) The myotubularin phosphatase MTMR4 regulates sorting from early endosomes. J. Cell Sci. 123, 3071–3083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kusanagi K., Inoue H., Ishidou Y., Mishima H. K., Kawabata M., Miyazono K. (2000) Characterization of a bone morphogenetic protein-responsive Smad-binding element. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 555–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Korchynskyi O., ten Dijke P. (2002) Identification and functional characterization of distinct critically important bone morphogenetic protein-specific response elements in the Id1 promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4883–4891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liang Y. Y., Lin X., Liang M., Brunicardi F. C., ten Dijke P., Chen Z., Choi K. W., Feng X. H. (2003) dSmurf selectively degrades decapentaplegic-activated MAD, and its overexpression disrupts imaginal disc development. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 26307–26310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weng C., Li Y., Xu D., Shi Y., Tang H. (2005) Specific cleavage of Mcl-1 by caspase-3 in tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis in Jurkat leukemia T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10491–10500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Monteiro R. M., de Sousa Lopes S. M., Korchynskyi O., ten Dijke P., Mummery C. L. (2004) Spatio-temporal activation of Smad1 and Smad5 in vivo: monitoring transcriptional activity of Smad proteins. J. Cell Sci. 117, 4653–4663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miyazono K., Miyazawa K. (2002) Id: a target of BMP signaling. Sci STKE 2002, pe40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pardali K., Kowanetz M., Heldin C. H., Moustakas A. (2005) Smad pathway-specific transcriptional regulation of the cell cycle inhibitor p21(WAF1/Cip1). J. Cell. Physiol. 204, 260–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Simmonds A. J., Brook W. J., Cohen S. M., Bell J. B. (1995) Distinguishable functions for engrailed and invected in anterior-posterior patterning in the Drosophila wing. Nature 376, 424–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lorenzo O., Urbé S., Clague M. J. (2006) Systematic analysis of myotubularins: heteromeric interactions, subcellular localisation and endosome related functions. J. Cell Sci. 119, 2953–2959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Khalsa O., Yoon J. W., Torres-Schumann S., Wharton K. A. (1998) TGF-β/BMP superfamily members, Gbb-60A and Dpp, cooperate to provide pattern information and establish cell identity in the Drosophila wing. Development 125, 2723–2734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lecuit T., Brook W. J., Ng M., Calleja M., Sun H., Cohen S. M. (1996) Two distinct mechanisms for long-range patterning by Decapentaplegic in the Drosophila wing. Nature 381, 387–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marty T., Müller B., Basler K., Affolter M. (2000) Schnurri mediates Dpp-dependent repression of brinker transcription. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 745–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shi W., Chang C., Nie S., Xie S., Wan M., Cao X. (2007) Endofin acts as a Smad anchor for receptor activation in BMP signaling. J. Cell Sci. 120, 1216–1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bangi E., Wharton K. (2006) Dpp and Gbb exhibit different effective ranges in the establishment of the BMP activity gradient critical for Drosophila wing patterning. Dev. Biol. 295, 178–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Green J. (2002) Morphogen gradients, positional information, and Xenopus: interplay of theory and experiment. Dev. Dyn. 225, 392–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eivers E., Demagny H., Choi R. H., De Robertis E. M. (2011) Phosphorylation of Mad controls competition between wingless and BMP signaling. Sci. Signal 4, ra68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lin X., Duan X., Liang Y. Y., Su Y., Wrighton K. H., Long J., Hu M., Davis C. M., Wang J., Brunicardi F. C., Shi Y., Chen Y. G., Meng A., Feng X. H. (2006) PPM1A functions as a Smad phosphatase to terminate TGFβ signaling. Cell 125, 915–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jarzab B., Wiench M., Fujarewicz K., Simek K., Jarzab M., Oczko-Wojciechowska M., Wloch J., Czarniecka A., Chmielik E., Lange D., Pawlaczek A., Szpak S., Gubala E., Swierniak A. (2005) Gene expression profile of papillary thyroid cancer: sources of variability and diagnostic implications. Cancer Res. 65, 1587–1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chauvet C. M., Ménard A., Xiao C., Aguila B., Blain M., Roy J., Deng A. Y. (2012) Novel genes as primary triggers for polygenic hypertension. J. Hypertension 30, 81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Staehling-Hampton K., Jackson P. D., Clark M. J., Brand A. H., Hoffmann F. M. (1994) Specificity of bone morphogenetic protein-related factors: cell fate and gene expression changes in Drosophila embryos induced by decapentaplegic but not 60A. Cell Growth Differ. 5, 585–593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]