Abstract

Context:

Fat distribution differs in men and women, but in both sexes, a predominantly gluteal-femoral compared with abdominal (central) fat distribution is associated with lower metabolic risk. Differences in cellular characteristics and metabolic functions of these depots have been described, but the molecular mechanisms involved are not understood.

Objective:

Our objective was to identify depot- and sex-dependent differences in gene expression in human abdominal and gluteal sc adipose tissues.

Design and Methods:

Abdominal and gluteal adipose tissue aspirates were obtained from 14 premenopausal women [age 27.5 ± 7.0 yr, body mass index (BMI) 27.3 ± 6.2 kg/m2, and waist-to-hip ratio 0.82 ± 0.04] and 21 men (age 29.7±7.4 yr, BMI 27.2 ± 4.5 kg/m2, and waist-to-hip ratio 0.91 ± 0.07) and transcriptomes were analyzed using Illumina microarrays. Expression of selected genes was determined in isolated adipocytes and stromal vascular fractions from each depot, and in in vitro cultures before and after adipogenic differentiation.

Results:

A total of 284 genes were differentially expressed between the abdominal and gluteal depot, either specifically in males (n = 66) or females (n = 159) or in both sexes (n = 59). Most notably, gene ontology and pathway analysis identified homeobox genes (HOXA2, HOXA3, HOXA4, HOXA5, HOXA9, HOXB7, HOXB8, HOXC8, and IRX2) that were down-regulated in the gluteal depot in both sexes (P = 2 × 10−10). Conversely, HOXA10 was up-regulated in gluteal tissue and HOXC13 was detected exclusively in this depot. These differences were independent of BMI, were present in both adipocytes and stromal vascular fractions of adipose tissue, and were retained throughout in vitro differentiation.

Conclusions:

We conclude that developmentally programmed differences may contribute to the distinct phenotypic characteristics of peripheral fat.

The initial reports of J. Vague (1) over 60 yr ago made clear that in addition to total fat mass, a central android rather than a peripheral gynoid pattern of fat deposition is independently linked to increased disease risk. Much of the subsequent work focused on the detrimental role of visceral adipose tissue (2) and its metabolic and endocrine function (3). To a lesser extent, the heterogeneity between the different sc depots has also been investigated, and clinical and epidemiological data have clearly established that the gluteal-femoral adipose tissue acts as a protective energy store (4). In contrast, excessive abdominal sc fat is associated with deleterious metabolic consequences (5).

In both sexes, the gluteal-femoral depot is characterized by lower stimulated (in vitro by noradrenaline and in vivo by exercise) lipolysis, due to higher numbers of adipocyte α2-adrenergic receptors (6–8). However, the lipolytic response in the gluteal-femoral fat is not different between sexes, and thus, the current consensus in the literature is that lipolysis does not contribute essentially to the peripheral fat deposition seen preferentially in females (9). Rather, mechanisms that regulate fatty acid and glucose uptake are different according to depot and sex; in premenopausal women, gluteal adipocytes are larger, have higher lipoprotein lipase activity, and are more sensitive to the antilipolytic effect of insulin in vitro compared with men (10–14). In addition, the gluteal-femoral adipose tissue of women is more efficient at directly taking up circulating fatty acids in the postabsorptive state, both compared with the abdominal depot in women and compared with men (15, 16).

There are also sex and depot differences in adipose tissue growth. The femoral adipose tissue, particularly of women, contains more early-differentiated adipocytes, and in response to overfeeding, it is able to expand by hyperplasia, in contrast to the hypertrophic response seen in the abdominal sc fat (17, 18); no data are currently available regarding the gluteal fat.

At least some of the differences between sc and visceral fat depots are cell autonomous and retained in long-term in vitro cultures (19). Limited evidence indicates that such inherent depot features may stem from differences in developmental genes, like the homeobox (HOX) genes (20–22). Most differences between omental (visceral) and abdominal sc adipose tissue in HOX gene expression are detected in both sexes, [Shox (short stature homeobox) 2, En1 (Engrailed) 1, HOXA5, HOXC8, Thbd (thrombomodulin)], whereas others are detected only in females (HOXC9). Intriguingly, a recent genome-wide association study identified a number of developmental genes that are associated with waist-to-hip ratio [HOX C13, ZNRF (zinc and ring finger) 3, TBX (T-Box) 15], especially in women (23). A few recent studies have investigated differences in the transcriptome between the gluteal-femoral and the abdominal sc tissue, but they did not take into account the role of sex (24, 25).

The goal of this investigation was to explore the differences in gene expression in abdominal vs. gluteal sc adipose tissues of men and women to identify novel pathways that regulate adipose tissue distribution in a sex-dependent or -independent fashion. Using adipose tissue samples collected under standardized experimental conditions and in males with typical android or females with gynoid fat distribution, we identified mRNAs that vary in a sex- and depot-specific fashion. Our data support the hypothesis that cell autonomous differences exist between abdominal and gluteal sc depots of humans, most likely determined through epigenetic programming.

Materials and Methods

Twenty-one men and 14 women were recruited through flyers, postcards, and websites to participate in a multicenter translational research protocol conducted at three sites (University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD; Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA; and University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA) after approval by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards. A single research protocol and standardized procedures were used to harmonize data collection for both clinical procedures and adipose sample collection. For the latter, a manual of procedures was implemented during a baseline training session for all staff.

To participate, volunteers needed to be between the age of 18 and 40 with percent body fat of 20–50%. At screening, volunteers were excluded for significant medical illness, glucocorticoid use, smoking, or substance/alcohol abuse, and women needed to have normal menstrual cycles. Oral contraceptive pills were not allowed. Waist circumference less than 88 cm for women was used to enrich the population with those with a normal/gynoid fat distribution. The entire cohort was recruited based on these criteria, and a goal was set to enroll both lean and overweight/obese subjects. The characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Variable | Females | Males | P value | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 14 | 21 | 35 | |

| Age (yr) | 27.5 ± 7.0 | 29.7 ± 7.4 | NS | 28.8 ± 7.2 |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian/African-American/other) | 12/2/0 | 16/4/1 | NS | 28/6/1 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.3 ± 6.2 | 27.2 ± 4.5 | NS | 27.3 ± 4.9 |

| Body fat (%) | 35.3 ± 10.4 | 24.1 ± 7.8 | <0.001 | 28.6 ± 10.4 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.82 ± 0.04 | 0.91 ± 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.07 |

After an overnight fast, blood samples were collected, accessioned, aliquoted, frozen, and then shipped to the Pennington Biomedical Research Center Clinical Chemistry Laboratory for analysis. Body composition was measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (Hologic QDR 4500A; Hologic, Waltham, MA; or LUNAR GE version 7.53.002).

Adipose tissue biopsies were collected with a three-hole 2.5-mm liposuction cannula from the midabdomen approximately 5–8 cm lateral to the umbilicus using percutaneous liposuction (Unitech Instruments, Fountain Valley, CA). Gluteal adipose tissue was collected from the lateral aspect of the lower extremity just below the gluteal crease. Samples were cleaned at bedside according to the manual of procedures, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 C for downstream analysis.

Total RNA was isolated using a single protocol in the laboratory of Dr. S. R. Smith (Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA) with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The quantity and integrity of the RNA was confirmed with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Quantification was performed using NanoDrop.

Microarray

Near-whole-genome transcriptome analysis was performed using the Illumina bead-based technology and Sentrix Human-6 V2 Expression BeadChip (part number BD-25-113; Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA).

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was reverse transcribed using Transcriptor First-Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed on a LightCycler 480 (Roche) with commercially available TaqMan probes (Roche) using the following parameters: one cycle of 95 C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles at 95 C for 10 sec and 60 C for 1 min. For each gene, a standard curve was generated with cDNA prepared from pooled RNA samples. Cyclophilin A (PPIA) was used as reference gene, and relative expression levels were calculated using LightCycler 480 relative quantification software (Roche).

Isolation of adipose fractions and in vitro experiments

Eleven subjects [eight males and three females, age 27.5 ± 7.3 yr, body mass index (BMI) 28.6 ± 5.1 kg/m2, and waist-to-hip ratio 0.88 ± 0.07] were recruited at Boston University Medical Center, Boston, MA, after approval of the study by the Institutional Review Board of the Boston Medical Center and abdominal and gluteal adipose tissue biopsies were obtained with the same technique. Adipocytes and stromal-vascular fractions were isolated with collagenase digestion with 1 mg/ml collagenase type 1 (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood Township, NJ) in Hanks' balanced salt solution shaken for 2 h at 37 C and used for RNA extraction.

Isolated stromal-vascular fractions were also plated, grown, and subcultured at 70–80% confluence in α-MEM (GIBCO, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. At passage 4, cells were seeded and differentiated as previously described (26). Briefly, 2-d postconfluency cells were induced to differentiate in DMEM/Ham's F12 (1:1) containing isobutylmethylxanthine (0.5 mm), rosiglitazone (1 μm), dexamethasone (100 nm), insulin (100 nm), T3 (2 nm), and transferrin (10 μg/liter) for 8 d and then maintained in DMEM/F12 containing only insulin (10 nm) and dexamethasone (10 nm) until d 14. Cells were harvested across differentiation (d 0–14), RNA was extracted, and target genes were measured as described above.

Statistical analyses and bioinformatics

Raw microarray data were imported into SAS version 9.2 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC), and low-quality data, specifically probes not above background or with high background intensities, were excluded based on the Illumina platform scanning software metric Detection Value (P < 0.05). Box plots were used to visualize the transcriptome data before and after normalization of the data. Normalization of the raw data was accomplished using SAS code written to implement a quantile normalization procedure as described previously (27). The data were additionally filtered because some genes were not expressed in all samples; genes that were determined as present in fewer than 14 of the 70 samples were excluded. Missing data were imputed using an Markov Chain Monte Carlo procedure (28). We performed a separate search for genes that might be present in only one depot (e.g. only in gluteal or only in abdominal depot within a subject).

The significance of the fold change of the depot and sex effect was tested for each gene using ANOVA (PROC MIXED in SAS). Also, the false discovery rate was calculated for each gene with a cut point at P < 0.05. We compared the lists of genes that differed significantly between abdominal and gluteal fat in males and females and identified groups of depot-different genes that were either shared between sexes or were sex specific. Gene Ontology and pathway analyses were based on this grouping (GOTERM_BP_ALL, KEGG_PATHWAY and Gene Functional Classification tools of the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery, DAVID version 6.7) (29).

Statistical analysis for the qPCR and cell culture data were performed using JMP Pro version 9 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) or GraphPad Prism version 5.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Depot differences within sex were determined by paired t tests, and sex differences were tested with unpaired t tests. Multivariate ANOVA was used to determine whether BMI affected depot or sex differences. All values in figures and tables are presented as mean ± sem. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Subject characteristics

The demographic and anthropometric characteristics of the participating subjects are shown in Table 1. All subjects had normal fasting glucose and insulin levels. As expected from known sex differences, female subjects were characterized by higher percent body fat and a lower waist-to-hip ratio compared with males.

A total of 284 genes are differentially expressed between abdominal and gluteal sc fat

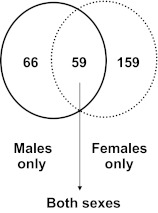

In the microarray analysis, 11,679 probes were consistently expressed in abdominal and gluteal adipose tissues of both men and women (detection P < 0.05). Among those, 305 probes (2.6%), corresponding to 284 unique Entrez Gene IDs, differed significantly between the two depots. Of these 284 genes, 66 genes (23%) were differentially expressed only in men and 159 (56%) only in women, and 59 (21%) were different in both sexes (Fig. 1 and Supplemental Table 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://jcem.endojournals.org). Differences between abdominal and gluteal adipose tissue were generally modest, with fold changes between 1.3-fold (set as lower limit of likely biological importance) and 4-fold; most were in the range of 1.5- to 2-fold.

Fig. 1.

Depot differences in gene expression specific in males or in females or common in both sexes. Venn diagram depicts number of genes that were differentially expressed between gluteal and abdominal sc adipose tissue, either in a sex-specific way (only in males or only in females) or in both sexes.

Genes that were depot specific in both sexes

We used Gene Ontology and Pathway Analysis [Kyoto Encyclopedia for Genes and Genomes (KEGG)] to identify biological functions that differ between the two depots either in both sexes or in a sex-specific manner. The 59 genes that were depot specific in both sexes (23 up-regulated and 36 down-regulated in the gluteal depot, Fig. 1) showed very highly significant associations with Gene Ontology terms related to embryonic development and pattern specification (P = 1.7 × 10−10, Table 2). The related genes were homeobox genes: HOXA2, HOXA3, HOXA4, HOXA5, HOXA9, HOXA10, HOXB7, HOXB8, HOXC8, HOXD4, and IRX2, transcription factors that drive embryonic development.

Table 2.

Enriched Gene Ontology terms among depot-specific genes

| Category | Term | Count | % | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common in both sexes | ||||

| GO:0048706 | Embryonic skeletal system development | 9 | 16.1 | 1.7 × 10−10 |

| GO:0009952 | Anterior/posterior pattern formation | 10 | 17.9 | 8.4 × 10−10 |

| GO:0048598 | Embryonic morphogenesis | 12 | 21.4 | 4.5 × 10−9 |

| GO:0001501 | Skeletal system development | 12 | 21.4 | 6.7 × 10−9 |

| GO:0003002 | Regionalization | 10 | 17.9 | 1.7 × 10−8 |

| GO:0048704 | Embryonic skeletal system morphogenesis | 7 | 12.5 | 3.5 × 10−8 |

| GO:0048705 | Skeletal system morphogenesis | 8 | 14.3 | 9.1 × 10−8 |

| GO:0007389 | Pattern specification process | 10 | 17.9 | 2.3 × 10−7 |

| GO:0048562 | Embryonic organ morphogenesis | 8 | 14.3 | 2.9 × 10−7 |

| GO:0043009 | Chordate embryonic development | 10 | 17.9 | 1.4 × 10−6 |

| GO:0009792 | Embryonic development ending in birth or egg hatching | 10 | 17.9 | 1.5 × 10−6 |

| GO:0048568 | Embryonic organ development | 8 | 14.3 | 1.7 × 10−6 |

| GO:0006355 | Regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | 14 | 25.0 | 5.0 × 10−3 |

| GO:0051252 | Regulation of RNA metabolic process | 14 | 25.0 | 6.0 × 10−3 |

| GO:0001568 | Blood vessel development | 5 | 8.9 | 9.4 × 10−3 |

| GO:0001944 | Vasculature development | 5 | 8.9 | 1.0 × 10−2 |

| GO:0048732 | Gland development | 4 | 7.1 | 1.1 × 10−2 |

| GO:0006350 | Transcription | 14 | 25.0 | 2.0 × 10−2 |

| GO:0050678 | Regulation of epithelial cell proliferation | 3 | 5.4 | 2.4 × 10−2 |

| GO:0048514 | Blood vessel morphogenesis | 4 | 7.1 | 3.5 × 10−2 |

| GO:0048010 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor signaling pathway | 2 | 3.6 | 3.7 × 10−2 |

| GO:0035295 | Tube development | 4 | 7.1 | 3.9 × 10−2 |

| GO:0030878 | Thyroid gland development | 2 | 3.6 | 4.0 × 10−2 |

| GO:0030324 | Lung development | 3 | 5.4 | 4.5 × 10−2 |

| GO:0045449 | Regulation of transcription | 15 | 26.8 | 4.6 × 10−2 |

| GO:0030323 | Respiratory tube development | 3 | 5.4 | 4.7 × 10−2 |

| GO:0042127 | Regulation of cell proliferation | 7 | 12.5 | 4.9 × 10−2 |

| GO:0060541 | Respiratory system development | 3 | 5.4 | 5.0 × 10−2 |

| Specific in males | ||||

| GO:0042127 | Regulation of cell proliferation | 8 | 13.1 | 1.0 × 10−2 |

| GO:0034109 | Homotypic cell-cell adhesion | 2 | 3.3 | 2.0 × 10−2 |

| Specific in females | ||||

| GO:0009896 | Positive regulation of catabolic process | 4 | 2.6 | 7.9 × 10−3 |

| GO:0009894 | Regulation of catabolic process | 5 | 3.2 | 8.5 × 10−3 |

| GO:0030162 | Regulation of proteolysis | 4 | 2.6 | 9.8 × 10−3 |

| GO:0031329 | Regulation of cellular catabolic process | 4 | 2.6 | 1.4 × 10−2 |

| GO:0001701 | In utero embryonic development | 6 | 3.9 | 1.6 × 10−2 |

| GO:0043009 | Chordate embryonic development | 8 | 5.2 | 2.1 × 10−2 |

| GO:0009792 | Embryonic development ending in birth or egg hatching | 8 | 5.2 | 2.2 × 10−2 |

| GO:0017038 | Protein import | 5 | 3.2 | 2.4 × 10−2 |

| GO:0010604 | Positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process | 14 | 9.1 | 2.6 × 10−2 |

| GO:0007507 | Heart development | 6 | 3.9 | 3.4 × 10−2 |

| GO:0006605 | Protein targeting | 6 | 3.9 | 3.4 × 10−2 |

| GO:0006694 | Steroid biosynthetic process | 4 | 2.6 | 3.4 × 10−2 |

| GO:0045449 | Regulation of transcription | 31 | 20.1 | 3.5 × 10−2 |

| GO:0006606 | Protein import into nucleus | 4 | 2.6 | 3.5 × 10−2 |

| GO:0031331 | Positive regulation of cellular catabolic process | 3 | 1.9 | 3.6 × 10−2 |

| GO:0035113 | Embryonic appendage morphogenesis | 4 | 2.6 | 3.6 × 10−2 |

| GO:0030326 | Embryonic limb morphogenesis | 4 | 2.6 | 3.6 × 10−2 |

| GO:0051170 | Nuclear import | 4 | 2.6 | 3.7 × 10−2 |

| GO:0008286 | Insulin receptor signaling pathway | 3 | 1.9 | 3.8 × 10−2 |

| GO:0006999 | Nuclear pore organization | 2 | 1.3 | 4.1 × 10−2 |

| GO:0034504 | Protein localization in nucleus | 4 | 2.6 | 4.4 × 10−2 |

| GO:0033194 | Response to hydroperoxide | 2 | 1.3 | 4.9 × 10−2 |

| GO:0035107 | Appendage morphogenesis | 4 | 2.6 | 5.0 × 10−2 |

| GO:0035108 | Limb morphogenesis | 4 | 2.6 | 5.0 × 10−2 |

Genes that were depot specific only in males

The 66 genes that were depot specific only in males (32 up-regulated and 34 down-regulated in the gluteal depot, Fig. 1) were enriched in Gene Ontology terms associated with cell proliferation and cell adhesion (Table 2). In addition, KEGG analysis identified three genes, as part of the calcium signaling pathway: CAMK2D (calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIδ), which was lower in the gluteal, and PDE1A (phosphodiesterase 1A, calmodulin-dependent) and PLCD4 (phospholipase C, δ4) which were higher in the gluteal compared with abdominal fat.

Genes that were depot specific only in females

This group contained more genes in accordance with the more prominent phenotypic differences between depots in females (159 total, 34 up-regulated and 125 down-regulated in the gluteal fat, Fig. 1). Enriched Gene Ontology terms were associated with catabolic processes, development, and protein import to the nucleus (Table 2). KEGG analysis identified five genes of the insulin signaling pathway: MAPK10, PHKG1 [phosphorylase kinase, γ1 (muscle)], CBLB (Cbl proto-oncogene, E3 ubiquitin protein ligase B), INS-IGF2 (insulin-IGF-II readthrough) and IRS2 (insulin receptor substrate 2), all with lower expression in the gluteal compared with abdominal fat.

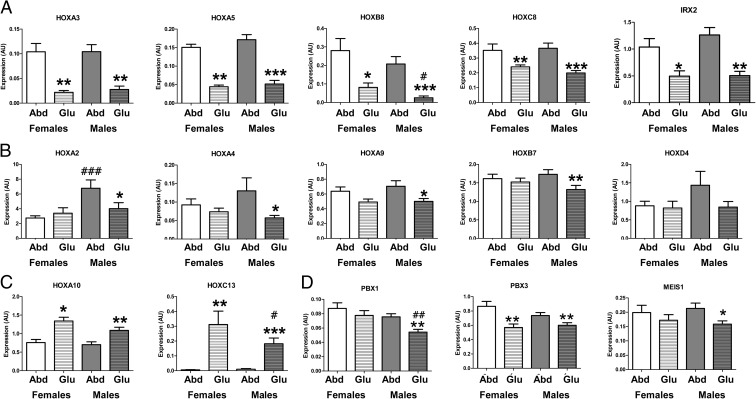

HOX gene expression is depot specific

As shown in Fig. 2, we verified by qPCR that expression of multiple HOX genes was higher in the abdominal depot in both sexes (HOXA3, HOXA5, HOXB8, HOXC8, and IRX2), or only in males (HOXA2, HOXA4, HOXA9, and HOXB7). HOXA10 was the only gene in this group that was higher in the gluteal depot. Differences in expression of HOXD4 were not statistically significant by qPCR. The expression of these HOX genes did not correlate with BMI in either of the depots, except gluteal HOXD4 expression (r = 0.53, P = 0.004). Also, BMI had no influence on the depot and sex differences noted (multivariate ANOVA). This study was not powered to detect race differences, but exclusion of the six African-American subjects did not change the results, with the exception of the depot difference in HOXA4 (P = 0.11).

Fig. 2.

Expression of HOX genes and HOX gene cofactors in abdominal (Abd) and gluteal (Glu) sc adipose tissue. A and B, Predominantly abdominal HOX genes: A, expression of HOXA3, HOXA5, HOXB8, HOXC8, and IRX2 was higher in the abdominal compared with gluteal adipose tissue in both sexes; B, expression of HOXA2, HOXA4, HOXA9, and HOXB7 was higher in the abdominal compared with gluteal adipose tissue in males only, and expression of HOXD4 was not statistically different between depots. C, Predominantly gluteal HOX genes: expression of HOXA10 and HOXC13 was higher in the gluteal compared with abdominal adipose tissue in both sexes. D, Expression of the HOX genes cofactors PBX1, PBX3, and MEIS1 in the abdominal and gluteal adipose tissue of men and women. Data are presented as mean ± sem of females (n = 14) and males (n = 21). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 compared with Abd of same sex; #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01; ###, P < 0.001 compared with same depot of females.

Genes that were undetectable in one depot could have been excluded from the initial analysis, so as a next step we searched the microarray data for HOX genes that scored as absent in one depot and present in the other. HOXC13 was found to be expressed exclusively in the gluteal depot. RT-qPCR confirmed that HOXC13 was undetectable in the majority of the abdominal samples of both men and women (25 of 35) with very low expression in the remaining samples (cycle threshold > 36), but present in all gluteal samples (cycle threshold 32–36) (Fig. 2).

Microarray data on the expression of all 39 human HOX genes and of the related genes in the HOX-linked subclass of homeobox genes (which in total exceed 250) (30) are included in Supplemental Table 2.

Expression of HOX gene cofactors is also depot specific

HOX gene cofactors restrict binding and the activity of HOX to specific DNA targets. Three of these cofactors [PBX (pre-B-cell leukemia homeobox) 1 and 3 and MEIS (myeloid ecotropic viral integration site homolog) 1] were depot-specifically expressed in the microarray (Supplemental Table 2). qPCR confirmed that expression of PBX1 and MEIS1 is higher in the abdominal compared with the gluteal depot in male subjects, independent of BMI, whereas PBX3 is higher in both males and females (Fig. 2). Interestingly, PBX1 mRNA levels in both depots correlated negatively with BMI in men [abdominal r = −0.66 (P = 0.001), and gluteal r = −0.57 (P = 0.01)], with a similar trend in the abdominal depot of women (r = −0.51, P = 0.07).

Sex differences in the expression of HOX genes and their cofactors

Expression of the majority of HOX genes was comparable between males and females in both depots. Males presented with higher HOXA2 expression in the abdominal depot (P < 0.001) and lower HOXB8, HOXC13, and PBX1 expression in the gluteal depot compared with females (P < 0.05, P < 0.05, and P < 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 2). These differences were independent of BMI.

Depot differences in HOX gene expression are present in both isolated adipocytes and stromal-vascular fraction and persist during in vitro differentiation

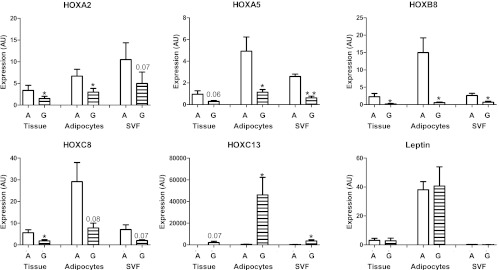

A second group of volunteers was recruited to investigate whether the differential expression of HOX genes is due to alterations in adipocytes and/or the stromal-vascular cells and to obtain preadipocytes for in vitro cultures. The differences between abdominal and gluteal tissue were replicated in this group (n = 11, eight males and three females). As shown in Fig. 3, HOX genes were expressed in both isolated adipocyte and stromal-vascular fractions, and the depot differences were apparent in both fractions (leptin expression was used as control, n = 3, two males and one female). Results were similar in the female subject.

Fig. 3.

Expression of selected HOX genes in adipose tissue fractions. Expression of selected HOX genes is depot specific in both isolated adipocytes and stromal-vascular fraction (SVF) (n = 11 for paired abdominal (A) and gluteal (G) tissue samples, n = 3 for isolated adipocytes and stromal-vascular fractions). Data are presented as mean ± sem. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 compared with abdominal (paired t test).

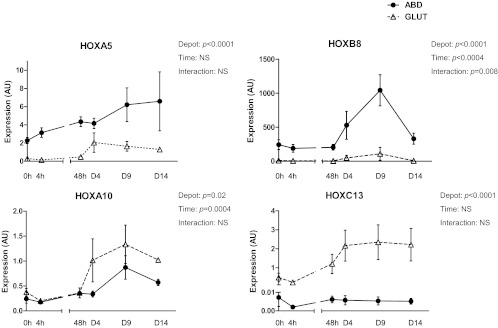

To establish whether the depot differences in HOX gene expression are maintained ex vivo and/or are regulated by differentiation, preadipocytes derived from the abdominal and the gluteal depot were studied before and after in vitro differentiation (n = 4, three males and one female). As shown in Fig. 4, expression of HOX genes increases during differentiation by 2- to 4-fold. Reflecting the differences in tissue expression, expression of HOXA5 and HOXB8 was significantly higher in stromal cultures from the abdominal depot throughout the course of differentiation. Also similar to tissue data, expression of HOXA10 was higher in the gluteal preadipocytes and adipocytes, and expression of HOXC13 was restricted exclusively to the gluteal cells. The results in the cells from the female subject were similar to those from the males.

Fig. 4.

Expression of selected HOX genes during in vitro differentiation of human primary preadipocytes. Graphs depict expression of predominantly abdominal (HOXA5 and HOXB8) and predominantly gluteal (HOXA10 and HOXC13) HOX genes during in vitro differentiation of paired abdominal (ABD) and gluteal (GLUT) human primary preadipocytes (n = 4). Data are presented as mean ± sem and analyzed with repeated-measures ANOVA. AU, Arbitrary units; NS, not significant.

Discussion

Our data suggest that developmental factors may contribute to functional and morphological differences between lower body and upper body sc adipose tissues and to sex differences in adipose tissue distribution. In accordance with their rostral-caudal distribution, multiple anterior HOX genes were expressed at higher levels in abdominal than in gluteal adipose tissue. Most intriguingly, HOXC13 was expressed exclusively in the gluteal depot (in both sexes). Notably, a single-nucleotide polymorphism in this gene was associated with waist-to-hip ratio in a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies, with a stronger effect in women (23). HOXA10 was the only other homeobox gene higher in gluteal than abdominal adipose tissue (by <2-fold). These depot differences coexisted with subtler sex differences; gluteal HOXC13 and HOXB8 were higher in females compared with males, and abdominal HOXA2 was higher in males. There was also a clear male signature of depot differences; HOXA2, -A4, -A9, and -B7 were significantly higher in abdominal than gluteal samples of males only. Finally, the depot differences in HOX gene expression were maintained in cultured preadipocytes and in vitro differentiated adipocytes, suggesting an epigenetic origin that is programmed during early development and may be further modified in response to sex steroids (31–35).

HOX genes exist within four clusters (A–D) and are expressed in a specific sequence to determine the anterior-posterior and rostral-caudal axes during embryo development (36). Among the HOX genes that we identified as sex or depot different, several are known to be regulated by sex steroids: HOXA5 (34), HOXA9, HOXA10 (31, 32), HOXB7 (35), and HOXC13 (33). Of special interest is the observation that mixed-lineage leukemia histone methylases mediate the estrogen regulation of HOXC13 (33), suggesting a potential mechanism for programming the metabolic profile of gluteal adipose tissue. HOXA10 is also well established to be regulated by estrogen and to confer cell-type-specific estrogen sensitivity (32). The HOX cofactors PBX1, PBX3, and MEIS1 also differed between depots and in the case of PBX1 between sexes. Although the interactions of HOX with their cofactors are complex, the patterns of expression we demonstrate may contribute to depot-specific differences in adipocyte functional capacities.

The current data are consistent with previous work pointing to the importance of developmental, specifically HOX, genes in the depot-specific biology of human adipose tissues. HOXA10 was identified earlier as a gene that was expressed at a lower level in visceral compared with abdominal sc adipose tissue (20, 21). We further show that HOXA10 is higher in gluteal than abdominal adipose tissue. Interestingly, HOXA10 interacts with PBX1, a cofactor that was lower in gluteal than abdominal adipose tissue of males (not females). Because PBX1 is reported to suppress HOXA10 activity at promoters of genes involved in osteogenesis (37), it is tempting to speculate that the relative abundance of these factors promotes differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells toward an adipogenic fate.

Our data draw special attention to HOXC13, the only HOX gene exclusively expressed in the gluteal depot and at higher levels in females, the latter finding being consistent with previous genetic studies (23). In mice, HOXC13 is expressed in the nails and tail but also in hair follicles throughout the body. Disruption of its function and overexpression of HOXC13 lead to alopecia and skin defects (38), possibly through interactions with forkhead box transcription factors Foxn1 and Foxq1 (39). Interestingly, HOXC13 deletion in mouse skin leads to altered leptin expression; whether this is also the case in adipocytes remains to be examined, but it suggests the potential of HOXC13 to modulate fundamental adipocyte functions (39).

In addition to their extensively researched role in the embryo, HOX genes are retained in adult tissues where they serve unclear roles possibly related to plasticity (40). We have shown that key HOX genes of interest are expressed in both adipocytes and preadipocytes and vary to a moderate extent during in vitro differentiation. Additional studies are needed to investigate whether the sex differences in HOX gene expression observed in tissue are retained after ex vivo culture and whether the HOX network modulates either differentiation of preadipocytes or the functional properties of mature adipocytes of both men and women. Future studies should also determine the exact cell types within the nonadipocyte fraction of adipose tissue that exhibit depot-specific gene expression signatures, because adipose endothelial cells, macrophages, or other cells can affect the microenvironment within a specific sc adipose tissue depot and hence its functional properties. Because our study focused on differences between men and women with peripheral fat distribution, it remains to be determined whether fat distribution influences sex and depot differences in gene expression profiles and whether depot differences in HOX gene expression may contribute to racial differences in fat distribution.

In summary, HOX genes differ in human gluteal compared with abdominal adipose tissue. These results establish the unique developmental roots of the known differences among the two major sc adipose tissue depots. We anticipate that epigenetic regulation of HOX genes determines depot-specific properties during development and eventually depot-specific functional characteristics and that sex steroids serve modulatory roles at critical periods of development and throughout life.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the ISIS network and the members of the ISIS group, Jennifer Lovejoy, Nori Geary, Joel Elmquist, Philipp Scherer, Randy Seeley, and Richard Simerly, for their support of this research.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK072476, R24DK087669, and P30DK46200; the Society for Women's Health Research Interdisciplinary Studies on Sex Differences (ISIS) Network on Metabolism; the Evans Center for Interdisciplinary Biomedical Research Affinity Research Collaborative on Sex Differences in Adipose Tissue at Boston University School of Medicine; the Genomics Core Facility at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center; and the Geriatric Research Education Clinical Center, Baltimore Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

- BMI

- Body mass index

- HOX

- homeobox

- KEGG

- Kyoto Encyclopedia for Genes and Genomes

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR.

References

- 1. Vague J. 1956. The degree of masculine differentiation of obesity. A factor determining predisposition to diabetes, atherosclerosis, gout and uric calculus disease. Am J Clin Nutr 4:20–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Björntorp P. 1992. Abdominal fat distribution and disease: an overview of epidemiological data. Ann Med 24:15–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wajchenberg BL. 2000. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: their relation to the metabolic syndrome. Endocr Rev 21:697–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Manolopoulos KN, Karpe F, Frayn KN. 2010. Gluteofemoral body fat as a determinant of metabolic health. Int J Obes (Lond) 34:949–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jensen MD, Haymond MW, Rizza RA, Cryer PE, Miles JM. 1989. Influence of body fat distribution on free fatty acid metabolism in obesity. J Clin Invest 830:1168–1173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wahrenberg H, Lönnqvist F, Arner P. 1989. Mechanisms underlying regional differences in lipolysis in human adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 84:458–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leibel RL, Hirsch J. 1987. Site- and sex-related difference in adrenoceptor status of human adipose tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 64:1205–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arner P, Kriegholm E, Engfeldt P, Bolinder J. 1990. Adrenergic regulation of lipolysis in situ at rest and during exercise. J Clin Invest 85:893–898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jensen MD. 2008. Role of body fat distribution and the metabolic complications of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:S57–S63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fried SK, Kral JG. 1987. Sex differences in regional distribution of fat cell size and lipoprotein lipase activity in morbidly obese patients. Int J Obes 11:129–140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krotkiewski M, Björntorp P, Sjöström L, Smith U. 1983. Impact of obesity on metabolism in men and women: Importance of regional adipose tissue distribution. J Clin Invest 72:1150–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnson JA, Fried SK, Pi-Sunyer FX, Albu JB. 2001. Impaired insulin action in subcutaneous adipocytes from women with visceral obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 280:E40–E49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pedersen O, Hjøllund E, Lindskov HO. 1982. Insulin binding and action on fat cells from young healthy females and males. Am J Physiol 243:E158–E167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Foley JE, Kashiwagi A, Chang H, Huecksteadt TP, Lillioja S, Verso MA, Reaven G. 1984. Sex difference in insulin-stimulated glucose transport in rat and human adipocytes. Am J Physiol 246:E211–E2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shadid S, Kanaley JA, Sheehan MT, Jensen MD. 2007. Basal and insulin-regulated free fatty acid and glucose metabolism in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292:E1770–E1774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koutsari C, Ali AH, Mundi MS, Jensen MD. 2011. Storage of circulating free fatty acid in adipose tissue of postabsorptive humans: quantitative measures and implications for body fat distribution. Diabetes 60:2032–2040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tchoukalova YD, Votruba SB, Tchkonia T, Giorgadze N, Kirkland JL, Jensen MD. 2010. Regional differences in cellular mechanisms of adipose tissue gain with overfeeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:18226–18231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tchoukalova YD, Koutsari C, Votruba SB, Tchkonia T, Giorgadze N, Thomou T, Kirkland JL, Jensen MD. 2010. Sex- and depot-dependent differences in adipogenesis in normal-weight humans. Obesity 18:1875–1880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tchkonia T, Tchoukalova YD, Giorgadze N, Pirtskhalava T, Karagiannides I, Forse RA, Koo A, Stevenson M, Chinnappan D, Cartwright A, Jensen MD, Kirkland JL. 2005. Abundance of two human preadipocyte subtypes with distinct capacities for replication, adipogenesis, and apoptosis varies among fat depots. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 288:E267–E277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vohl MC, Sladek R, Robitaille J, Gurd S, Marceau P, Richard D, Hudson TJ, Tchernof A. 2004. A survey of genes differentially expressed in subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue in men. Obes Res 12:1217–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gesta S, Blüher M, Yamamoto Y, Norris AW, Berndt J, Kralisch S, Boucher J, Lewis C, Kahn CR. 2006. Evidence for a role of developmental genes in the origin of obesity and body fat distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:6676–6681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lau FH, Deo RC, Mowrer G, Caplin J, Ahfeldt T, Kaplan A, Ptaszek L, Walker JD, Rosengard BR, Cowan CA. 2011. Pattern specification and immune response transcriptional signatures of pericardial and subcutaneous adipose tissue. PLoS One 6:e26092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Heid IM, Jackson AU, Randall JC, Winkler TW, Qi L, Steinthorsdottir V, Thorleifsson G, Zillikens MC, Speliotes EK, Mägi R, Workalemahu T, White CC, Bouatia-Naji N, Harris TB, Berndt SI, Ingelsson E, Willer CJ, Weedon MN, Luan J, Vedantam S, Esko T, Kilpeläinen TO, Kutalik Z, Li S, Monda KL, et al. 2010. Meta-analysis identifies 13 new loci associated with waist-hip ratio and reveals sexual dimorphism in the genetic basis of fat distribution. Nat Genet 42:949–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rantalainen M, Herrera BM, Nicholson G, Bowden R, Wills QF, Min JL, Neville MJ, Barrett A, Allen M, Rayner NW, Fleckner J, McCarthy MI, Zondervan KT, Karpe F, Holmes CC, Lindgren CM. 2011. MicroRNA expression in abdominal and gluteal adipose tissue is associated with mRNA expression levels and partly genetically driven. PLoS One 6:e27338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Min JL, Nicholson G, Halgrimsdottir I, Almstrup K, Petri A, Barrett A, Travers M, Rayner NW, Mägi R, Pettersson FH, Broxholme J, Neville MJ, Wills QF, Cheeseman J; GIANT Consortium; MolPAGE Consortium, Allen M, Holmes CC, Spector TD, Fleckner J, McCarthy MI, Karpe F, Lindgren CM, Zondervan KT. 2012. Coexpression network analysis in abdominal and gluteal adipose tissue reveals regulatory genetic loci for metabolic syndrome and related phenotypes. PLoS Genet 8:e1002505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee MJ, Wu Y, Fried SK. 4 May 2012. A modified protocol to maximize differentiation of human preadipocytes and improve metabolic phenotypes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 10.1038/oby.2012.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. 2003. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19:185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fridley B, Rabe K, de Andrade M. 2003. Imputation methods for missing data for polygenic models. BMC Genetics 4(Suppl 1):S42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. 2009. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources. Nat Protoc 4:44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Holland PW, Booth HA, Bruford EA. 2007. Classification and nomenclature of all human homeobox genes. BMC Biol 5:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Block K, Kardana A, Igarashi P, Taylor HS. 2000. In utero diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure alters Hox gene expression in the developing Müllerian system. FASEB J 14:1101–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martin R, Taylor MB, Krikun G, Lockwood C, Akbas GE, Taylor HS. 2007. Differential cell-specific modulation of HOXA10 by estrogen and specificity protein 1 response elements. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:1920–1926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ansari KI, Kasiri S, Hussain I, Mandal SS. 2009. Mixed lineage leukemia histone methylases play critical roles in estrogen-mediated regulation of HOXC13. FEBS J 276:7400–7411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bens S, Ammerpohl O, Martin-Subero JI, Appari M, Richter J, Hiort O, Werner R, Riepe FG, Siebert R, Holterhus PM. 2011. Androgen receptor mutations are associated with altered epigenomic programming as evidenced by HOXA5 methylation. Sex Dev 5:70–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jin K, Kong X, Shah T, Penet MF, Wildes F, Sgroi DC, Ma XJ, Huang Y, Kallioniemi A, Landberg G, Bieche I, Wu X, Lobie PE, Davidson NE, Bhujwalla ZM, Zhu T, Sukumar S. 2012. The HOXB7 protein renders breast cancer cells resistant to tamoxifen through activation of the EGFR pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:2736–2741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Krumlauf R. 1994. Hox genes in vertebrate development. Cell 78:191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gordon JA, Hassan MQ, Saini S, Montecino M, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS, Stein JL, Lian JB. 2010. Pbx1 represses osteoblastogenesis by blocking Hoxa10-mediated recruitment of chromatin remodeling factors. Mol Cell Biol 30:3531–3541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Godwin AR, Capecchi MR. 1998. Hoxc13 mutant mice lack external hair. Genes Dev 12:11–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Potter CS, Pruett ND, Kern MJ, Baybo MA, Godwin AR, Potter KA, Peterson RL, Sundberg JP, Awgulewitsch A. 2011. The nude mutant gene Foxn1 is a HOXC13 regulatory target during hair follicle and nail differentiation. J Invest Dermatol 131:828–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Daftary GS, Taylor HS. 2006. Endocrine regulation of HOX genes. Endocr Rev 27:331–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]