Abstract

The study objective was to investigate whether women who frequently attend religious services are more likely to have breast cancer screening—mammography and clinical breast examinations—than other women. Multivariate logistic regression models show that white women who attended religious services frequently had more than twice the odds of breast cancer screening than white women who attended less frequently (Odds Ratio (OR) = 2.61; 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = 1.12, 6.06). The behavior of white women was different from African American women (religious attendance-race interaction term p-value = 0.008); African American women who attended religious services frequently were possibly less likely to have breast cancer screening (OR 0.49; CI = 0.19–1.31).

Keywords: breast cancer, religion, screening, race, African Americans

The maturity of an area of scientific research is often signaled by the appearance of a synthetic work that documents past accomplishments and identifies as yet unanswered questions. Epidemiological research into the relation between religiousness and health now has such a vade mecum in the recently published Handbook of Religion and Health by Koenig, McCullough, and Larson. The study reported here addresses one issue for which they say there is currently little relevant research. These authors opine: “Because of the strong relationship between religious attendance and social support, and the strong relationship between social support and medical compliance and screening, organizational types of religious involvement probably increase the likelihood of early cancer detection and treatment” (Koenig, McCullough, & Larson, 2001). Since a previous study by two of us has investigated the relationship between mammography screening and stage at diagnosis (Jones, Kasl, Curnen, Owens, & Dubrow, 1995), this report will concentrate on the hypothesis that religiousness, and specifically, frequent attendance at religious services, is associated with higher rates of breast cancer screening involving mammography and clinical breast examinations.

In a recent study Paskett et al. investigated the associations between several measures of religiousness and rates of cervical and breast cancer screening in a mostly African American sample (Paskett, Case, Tatum, Velez, & Wilson, 1999). In multivariate logistic regression analyses they reported no significant associations between religious predictors and either Pap smear or mammogram outcomes but they did report that being African American was associated with a higher probability of obtaining a Pap smear. Results given below present a different picture. There are several ways in which our study overcomes limitations in the Paskett study. Ours is a statewide population-based study. We control for important biomedical covariables and test for interactions between the predictor of religious attendance and race and socioeconomic covariables. Finally, the hypotheses tested are few and focused so that results are less vulnerable to challenge on the grounds of multiple comparisons.

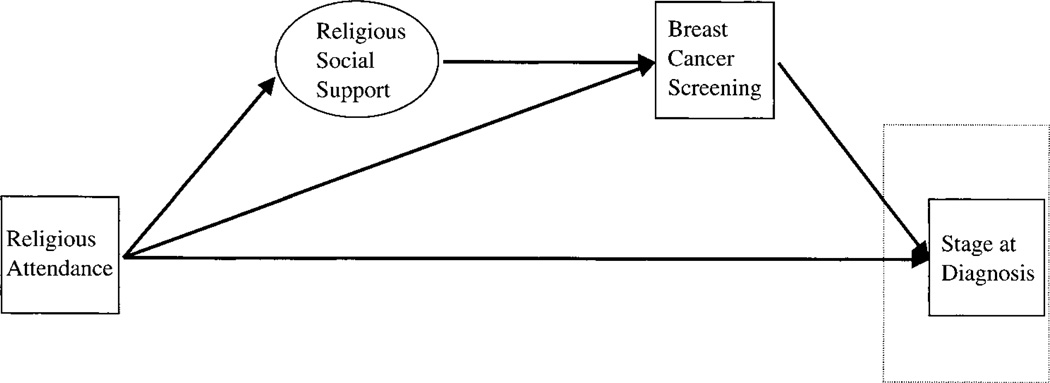

The primary hypothesis for this study is that frequency of religious attendance is positively associated with rates of breast cancer screening. A secondary hypothesis is that levels of social support mediate the effect of religious attendance on breast cancer screening. These two hypotheses reflect the thinking of Koenig, McCullough, and Larson (see Diagram 1). Our own point of view is that race and socioeconomic status may be modifiers of the religious attendance/screening relationship as they are of some other known predictors of breast cancer screening (Pearlman, Rakowski, B., & Clark, 1996) (Phillips & Wilbur, 1995) (Freeman, 1989). Also, our previous study of religion and breast cancer survival in this sample showed race to be an important covariable (Van Ness, Kasl, & Jones). Accordingly, it is appropriate that we test the above hypotheses in a data set originally assembled for the purpose of detecting race differences.

DIAGRAM 1.

Schematic Representation of Hypothesis of Koenig et al. Regarding the Association of Religious Attendance and Breast Cancer Screening

Methods

Population

Subject enrollment and study design have been described previously (Jones et al., 1995) (Jones, Kasl, Curnen, Owens, & Dubrow, 1997). Briefly, cases were identified through active surveillance of 22 Connecticut hospitals. Data from the Connecticut Tumor Registry for 1984–1985 indicated that approximately 98% of African-American and 84% of White breast cancer cases had been diagnosed in the participating hospitals. The study population was composed of 145 (45%) African-American women and 177 (55%) White women diagnosed with a first primary breast cancer in Connecticut between January 1987 and March 1989. All eligible African-American breast cancer cases diagnosed in these hospitals were selected for possible interview. A White breast cancer case was randomly selected using a computerized random digit generator from among all eligible White breast cancer cases, diagnosed in the same hospital, and within the same one to three week period, as the eligible African-American case. A 1:1 ratio of African-American and White cases was sought in order to meet the original objective of identifying factors explaining race differences in stage at diagnosis.

Ineligibility criteria included previous malignancy (same or different site), race other than African-American or White, race unknown, and age greater than 79. The respondent verified race at the time of the interview. Participants were interviewed in their homes using a standardized instrument, administered by trained interviewers. The instrument was a modified version of the questionnaire used in the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Black/White Cancer Survival Study and covered a wide range of demographic, health history, medical care, and psychosocial factors (Ries, Pollack, & Young, 1983). Among eligible subjects selected for enrollment the participation rate was 76 percent and did not differ significantly by race. Non-participants included persons who refused (including physician refusals to allow contact), moved, died before they could be interviewed, or were too ill to be interviewed.

Active surveillance identified the hospitals at which cases were diagnosed. Hospital medical records were abstracted for each case to provide complete information on medical history. Photocopies of pathology, operative, and staging reports, admission notes, discharge summaries, and referral correspondence were obtained. Further information was obtained when necessary from physicians’ office records. Since cases were population-based and were identified by active surveillance, and since we considered only screening rather than diagnostic examinations, the screening experience of breast cancer cases should be representative of screening experience in the general population.

Predictors

Three measures of religiousness were used as predictor variables. One inquired about religious denominational preference and is reported here as Protestant, Roman Catholic, Pentecostal, Jewish, and no denominational affiliation. The Pentecostal grouping combines the responses “Pentecostal” or “Holiness.” This combination is justified by the similar historical origins of the two groups and by their enduring emphasis on the gifts of the Holy Spirit including healing (Marty, 1997) (Raboteau, 1998). A second measure inquired about religious attendance (less than weekly vs. weekly or more frequently). A third, representing the respondent’s religious social network, measured the number of congregants known personally (none or a few vs. almost all).

Outcomes

The primary outcome variable was breast cancer screening status prior to diagnosis. It recorded whether or not a respondent followed public health recommendations that women receive periodic mammograms and breast examinations from a physician (Breast Cancer Facts and Figures, 2000–2001, 2001). A respondent was counted as having received breast cancer screening if she answered affirmatively to both of two inquiries, one asking “Did you have a mammogram within the last three years?” and the other asking “Did you have a breast exam by a doctor within the last two years?”

Covariables

The demographic covariables included in descriptive and multivariate analyses were: age (continuous); race (White vs. African American); marital status (married vs. not married); socioeconomic status: education (<12 vs. ≥12 years), family income (<$25,000 vs. ≥$25,000 per year), and occupational rank (an adaptation of the Duncan Socioeconomic Index using a combined spouse-pair score, dichotomized at the median).

Height and weight assessments were taken from the medical record to compute a body mass index (BMI) (weight in kilograms/(height in meters)2). Severe obesity was defined as BMI greater than or equal to 32.3. This value corresponds to the 95th percentile of the body mass distribution of women, ages 20–29, and was used by the National Center for Health Statistics to classify “severely overweight” adult females (Najjar & Rowland, 1987). (This older classification was used in order to make comparisons with other papers (Jones et al., 1995) (Jones et al., 1997) (Van Ness et al.) The comorbidity index was created from interview responses to questions regarding 22 common conditions. Specifically, respondents were asked if a doctor had told them in the year before their diagnosis that they had any of 22 common conditions. The variable for self-rated health consisted of levels of poor, fair, good, and excellent.

Respondents were asked whether or not they occasionally drank any kind of alcoholic beverage, and whether they had ever regularly smoked cigarettes for more than six months and whether they smoked regularly when interviewed. Two medical care covariables were examined. One recorded whether or not the respondent had a usual source of care. Several questions inquired about a respondent’s insurance coverage. An index was created from the responses and then was dichotomized as those having no or poor insurance coverage versus those having adequate insurance coverage. A social support variable was created to account for the mediating role proposed for it by Koenig et al. Respondents were identified as having a high degree of social support if they said that they knew all or almost all of the members of their congregation and if they agreed with the statement that they were able to talk with their friends about cancer.

Statistical analysis

Hypotheses were examined using multivariate logistic regression. Predictor variables were forced into multivariate models. Control variables were included only if they approached significance (p < 0.25) or had conceptual relevance. Model pruning was done in order to avoid collinearity and over-fitting. The model fitting approach used was manual backward elimination. Linearity tests were performed for continuous variables, i.e., age, education, self-rated health, and the comorbidity index, to ensure that there was a generally linear relationship between the predictor and outcome variables. In the absence of a linear relationship the education variable was dichotomized at 12 years.

A supplementary analysis involved a weighted logistic regression model. Weights were assigned to each White respondent in order to compensate for the oversampling of African Americans in the original data set. Specifically, African American respondents received a weight of 1 and White respondents received a weight of 14 in order to compensate for the fact that only some of the White cases of breast cancer reported in Connecticut during the enrollment period were randomly selected for inclusion in the study. The sampling weight of 14 for Whites is warranted given that participation rates for African Americans were somewhat lower and incidence rates of breast cancer for African Americans are somewhat lower than for Whites (Kelsey & Bernstein, 1996). The 1990 census records a 10.43 to 1 ratio of Whites to African Americans in Connecticut (The 1990 Census, 1990).

Stratification and clustering were not included as part of the original sampling design. However, control variables for the hospitals from which cases were recruited were added to multivariate models. These variables were either not significant or had no appreciable impact on the main predictor variables and were deleted from reported models. The SAS software program, version 8.0, was used in all statistical analyses (SAS/STAT User’s Guide, 1999).

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive characteristics of the study population. The first column gives the number of respondents belonging to the groups that are the values of a specific variable and the second provides the percentage of the total number of respondents for this variable that the preceding number constitutes. The third column gives the unadjusted odds ratio for the association of the variable with the outcome of breast cancer screening. An odds ratio of 1.00 is used to represent the reference group to which other groups of a variable are compared. Variables without a null reference level of 1.00 are treated as continuous scales.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Breast Cancer Cases in Connecticut, January 1987 to March 1989 including Unadjusted Associations with Breast Cancer Screening (Odds Ratios as Measure of Association)

| Variable | # | % | OR | Variable | # | % | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious | Biomedical | ||||||

| Denomination | Self-Rated Health | 2.78 | 0.81 | 1.47* | |||

| Protestant | 165 | 52.5 | 1.00 | (Mean) | (S.D.) | ||

| Roman Catholic | 102 | 32.5 | 0.97 | 1: Poor | 22 | 7.0 | |

| Jewish | 11 | 3.5 | 2.10 | 2: Fair | 78 | 24.9 | |

| Pentecostal | 25 | 8.0 | 0.66 | 3: Good | 159 | 50.8 | |

| None | 11 | 3.5 | 3.03 | 4: Excellent | 54 | 17.3 | |

| Attendance | Severe Obesity | ||||||

| <Weekly | 137 | 44.9 | 1.00 | No | 271 | 84.7 | 1.00 |

| ≥Weekly | 168 | 55.1 | 1.08 | Yes | 49 | 15.3 | 0.89 |

| Demographic | |||||||

| Age | 55.36 | 12.33 | 0.97** | Comorbidity | 2.83 | 2.11 | 1.06 |

| (Mean) | (S.D.) | Index | (Mean) | (S.D.) | |||

| Race | Behavioral | ||||||

| White | 177 | 55.0 | 1.00 | Alcohol Drinker | |||

| African American | 145 | 45.0 | 0.74 | No | 92 | 28.9 | 1.00 |

| Marital Status | Yes | 226 | 71.1 | 2.13* | |||

| No | 162 | 50.3 | 1.00 | Smoking | |||

| Yes | 160 | 49.7 | 1.41 | Never | 138 | 43.4 | 1.00 |

| Education (years) | Past | 114 | 36.2 | 1.97* | |||

| <12 | 79 | 24.5 | 1.00 | Current | 65 | 20.4 | 1.05 |

| ≥12 | 243 | 75.5 | 2.67** | Social Support | |||

| Income | Low | 177 | 56.4 | 1.00 | |||

| Low | 152 | 47.2 | 1.00 | High | 137 | 43.6 | 0.89 |

| High | 133 | 41.3 | 1.91* | Medical Care | |||

| Missing | 37 | 11.5 | 0.81 | Insurance | |||

| Occupational Rank | None/Poor | 176 | 55.3 | 1.00 | |||

| Below Median | 156 | 51.2 | 1.00 | Good | 142 | 44.7 | 1.46 |

| Above Median | 149 | 48.8 | 1.79* | Usual Care | |||

| Outcome | No | 106 | 33.5 | 1.00 | |||

| Screening | Yes | 210 | 66.5 | 4.42*** | |||

| No | 222 | 70.5 | —a | ||||

| Yes | 93 | 29.5 | —a |

This is the outcome variable for which other variables are predictors.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Bivariate analysis provides little evidence that religious attendance is a significant predictor of breast cancer screening (Table 2). The unadjusted odds ratio (OR = 1.08) and the correlation coefficient (r = 0.02) are in the hypothesized direction but clearly lack statistical significance, i.e., lack p-values less than 0.05. If there are potent modifiers of the association, however, the hypothesis could still be supported but only for a subgroup. Although social support is significantly associated with religious attendance—which one would expect because the coding of the variable reflects religious social networks—its association with breast cancer screening is not significant and even lacks the direction proposed by Koenig et al. (OR = 0.89, r = −0.03).

TABLE 2.

Correlation Matrix of Variables Relevant to the Hypothesis Regarding the Association of Religious Attendance and Breast Cancer Screening

| Variablea | Religious Attendance |

Race | Social Support |

Screening |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious Attendance (≥Weekly vs. <Weekly) | 1.00 | 0.16** | 0.37*** | 0.02 |

| Race (African American vs. White) | 0.16** | 1.00 | 0.12* | −0.07 |

| Social Support (High vs. Low) | 0.37*** | 0.12* | 1.00 | −0.03 |

| Breast Cancer Screening (Yes vs. No) | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.03 | 1.00 |

For these dichotomous variables the first category is coded as 1 and the second as 0.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

A multivariate logistic regression model of the religious attendance and breast cancer screening relationship shows that the religious attendance-race interaction term is significant (p = 0.008) (Table 3). In this same model religious attendance and race variables are included. Thus, with adjustment for other factors, there is evidence that the association between religious attendance and breast cancer screening is different for Whites and African Americans. Religious attendance interactions with education, income, and occupational rank, however, are not significant. When a second model is run with the religious attendance, and religious attendance-race interaction terms removed and indicator variables for White religious attendance and African American religious attendance substituted for them, then the association of White religious attendance and screening has an odds ratio elevated above the null value of 1 (OR = 2.61; 95% CI = 1.12–6.06) and African Americans have a lowered odds ratio (OR = 0.49; 95% CI = 0.19–1.31). Whites who attend religious services have more than two and a half times the odds of having had breast cancer screening than Whites who attend religious services less frequently. The odds ratio for African Americans suggests that those who attend religious services regularly are about one-half as likely to receive breast cancer screening as are those African Americans who attend less regularly. Unlike the odds ratio for the Whites this last cited odds ratio does not meet the 0.05 level of statistical significance. Again, social support is not significantly related to breast cancer screening.

TABLE 3.

Multivariate Analysis of the Association Between Religious Attendance and Breast Cancer Screening

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Religious | |||

| Religious Attendance-Race Interaction | —a | ----a | 0.008 |

| Religious Attendance (≥Weekly vs. <Weekly) |

—a | ----a | —b |

| Among Whites | 2.61 | 1.12–6.06 | 0.026 |

| Among African Americans | 0.49 | 0.19–1.31 | 0.157 |

| Religious Denominationc | |||

| Catholic | 0.79 | 0.37–1.71 | 0.553 |

| Jewish | 4.17 | 0.79–22.13 | 0.094 |

| Pentecostal | 0.56 | 0.16–1.94 | 0.363 |

| Demographic | |||

| Age (Continuous Scale) | 0.94 | 0.91–0.97 | 0.001 |

| Race (African American vs. White) | —a | ----a | —b |

| Marital Status (Yes vs. No) | 0.69 | 0.35–1.38 | 0.292 |

| Education (≥12 vs. <12) | 1.21 | 0.52–2.80 | 0.663 |

| Income (High vs. Low) | 1.22 | 0.58–2.55 | 0.607 |

| Biomedical | |||

| Comorbidity Index (Continuous Scale) | 1.21 | 1.04–1.42 | 0.016 |

| Self-Rated Health (Continuous Scale) | 1.45 | 0.96–2.19 | 0.074 |

| Behavioral | |||

| Social Support (High vs. Low) | 0.90 | 0.48–1.71 | 0.754 |

| Smokingd | |||

| Past | 1.62 | 0.84–3.14 | 0.150 |

| Current | 0.73 | 0.31–1.73 | 0.477 |

| Medical Care | |||

| Insurance (Good vs. None/Poor) | 1.50 | 0.83–2.74 | 0.183 |

| Usual Care (Yes vs. No) | 4.22 | 1.99–8.91 | 0.001 |

Odds ratios are not calculable for these terms.

P-values are not individually meaningful for these terms.

The reference group for the denomination indicator variable is the non-Pentecostal Protestant group.

The reference group for the smoking indicator variables is the never smoked group.

When the same logistic regression model is run for a weighted sample that approximates the 1990 ratio of Whites and African Americans in the Connecticut population, the religious attendance-race interaction term is no longer significant because of the high proportion of Whites. (The more appropriate test for race as an effect modifier is contained in the previously reported model in which White and African American groups are approximately equal in size.) When the interaction term is removed, the religious attendance variable is still associated with breast cancer screening in a significant way (OR = 2.41; 95% CI = 1.21–4.82). Again, this odds ratio mostly reflects the experience of Whites who are represented heavily in the sample. This association is maintained for White weighting ranging from 10 to 14. Thus the positive association of frequent religious attendance and high rates of breast cancer screening is present in this more representative weighted sample that accords better with the general character of the hypothesis of Koenig et al.

In order to try to understand the reasons for the religious attendance-race interaction two additional variables were examined. A strong positive predictor of breast cancer screening is whether or not physicians recommend that patients receive such care (Mandelblatt, Traxler, Lakin, Kanetsky, & Kao, 1992) (Vernon et al., 1992) (Stein, Fox, & Murata, 1991). (In our data the unadjusted OR = 9.33 and the 95% CI = 4.47, 19.49; this variable is not associated with religious attendance in the total sample and so is not a potential confounder of the religious attendance/breast cancer screening association.) In responding to the question as to whether or not they had received a physician’s recommendation for a mammogram, 68.4% of the Whites and 53.5% of the African Americans responded affirmatively (χ2 = 7.45, p = 0.006). Thus Whites were recommended for mammograms at a significantly higher rate than African Americans. Furthermore, for Whites physician recommendations were virtually the same for religious service attendees and nonattendees; however, for African Americans religious service nonattendees were more likely to get physician recommendations for mammography than were attendees (62.0% versus 50.0%). These differences are compatible with physician recommendations partially explaining the religious attendance-race interaction.

A strong negative predictor of cancer screening is a question that measures fatalism about the occurrence and outcome of cancer (In our data the unadjusted OR = 0.38 and the 95% CI = 0.20, 0.73; this variable is not associated with religious attendance in the total sample and so is not a potential confounder of the religious attendance/breast cancer screening association.) Some might speculate that African American religiousness engenders greater fatalism when women contemplate and confront breast cancer. Although there may be some evidence to support it (Matthews, Lannin, & Mitchell, 1994) (Lannin et al., 1998) (Gregg & Curry, 1994), this speculation is not in accord with the overall tenor of African American Christianity that has generally been an empowering force for the African American community (Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990). It is also not supported by respondents’ answers to the above-cited question measuring fatalism. Specifically, they were asked whether they agreed with the statement “Before my illness, I thought that if I’m going to get cancer, I’m going to get it, so I pretty much ignored it.” In answer to this question 28.9% of Whites agreed while only 21.6% of African Americans agreed (χ2 = 2.17, p = 0.141). Furthermore, among Whites 32.9% of attendees but only 25.9% of nonattendees agreed with the fatalistic sentiments of the question. Yet among African Americans 18.2% of attendees affirmed fatalistic sentiments while 25.5% of the nonattendees did. These differences are opposite to what might explain the religious attendance-race interaction.

Discussion

The results of this study provide some support for the hypothesis of Koenig et al. that higher levels of organized religiousness are associated with higher rates of cancer screening, thereby offering the possibility of earlier detection and treatment. This support is qualified, though, by the role of race as a significant effect modifier. Only Whites attending religious services frequently show the desirable outcome of increased rates of breast cancer screening. The authors’ above quoted hypothesis is further qualified by the absence of evidence that social support is a mediator of the religious attendance/breast cancer screening association. It is possible that the measure of social support employed was not sufficiently detailed or appropriate to detect this effect. Hence the lack of evidence for mediation reported here does not preclude that some other measure of social support might yield different results.

Additional analyses suggest that lower rates of breast cancer screening among African Americans religious attendees are accompanied by lower levels of physician mammography recommendations for African American women generally and especially for African American women attending religious services frequently. On the other hand, there is no evidence that lower rates of breast cancer screening among African American women are accompanied by religious fatalism. In fact, African American women seemed less likely to give fatalistic responses than White women and frequent African American church attendees were less fatalistic that similarly religious Whites to a statistically significant degree.

Addressing health promotion programs to religious communities is an increasingly common public health practice (Ransdell & Rehling, 1996). Researchers have not been quick to observe or appreciate this development; for instance, the new Institute of Medicine report on public health interventions extols multi-level, community strategies yet fails to mention religion or religious communities in their recommendations and rarely mentions them in accompanying commentary (Smedley & Syme, 2000). Textbook authors most often mention religion in the context of health promotion efforts in minority communities (Emmons, 2000) (Wingood & Keltner, 1999). In their recent review of Church-Based Health Promotion (CBHP) programs Ransdell and Rehling also report that “the majority of published papers described comprehensive programs within the African American community.” Decisions to locate health promotion and screening programs in African American churches do not appear to be based upon clear evidence of a positive association between some aspect of African American religiousness and rates of cancer screening. Results from this study, however, provide evidence that efforts to promote breast cancer screening might find a positive response among Whites attending religious services frequently because they engage in breast cancer screening more than their counterparts who attend less frequently or not at all. Further gains in breast cancer screening or in related preventive health practices would likely be attained if public health practitioners mount informative and sensitive health promotion efforts for this community.

Study results also indicate the need to understand the demonstrated disparity in breast cancer screening rates between African Americans and Whites who attend religious services frequently. If the low rates of breast cancer screening among African American women who attend religious services frequently are not due to some aspect of their religiousness, e.g., religious fatalism, but are partially explained by an aspect of the patient-physician interaction, e.g., low level of physician recommendations for such screening, then it is possible that a culturally sensitive and specific health promotion effort directed toward African American religious communities could be successful in raising screening rates. Efforts to measure the effectiveness of church-based breast cancer education programs are just beginning (Davis et al., 1994) (Dacey Allen, Sorensen, Peterson, Stoddard, & Colditz, 2001).

The major strength of this study is that the data set allows for an analysis of racial differences in breast cancer screening behavior. A second strength of the study is that it provides data to carry out supplementary analyses examining the possible roles of physician recommendations for mammography and fatalistic attitudes—two strong influences on breast cancer screening. The sample size of the study is modest, limiting the ability to perform subgroup analyses other than White/African American comparisons. Examining only the screening experience of women diagnosed with breast cancer might be a limitation but in this case it allows for comparisons with other studies of the same cohort dealing with stage at diagnosis and survival outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge with appreciation the assistance of Fenghai Duan.

The research was partially supported by a National Institute of Mental Health grant MH14235-24. It was also supported by National Cancer Institute program policy grant 5-PO1-CA42101, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research grant HS 06910-01, Research Training in the Epidemiology of Aging Grant 2-T32-Ag00153.

The authors thank the following Connecticut institutions for their participation in the study. Hartford Hospital, Yale-New Haven Hospital, Bridgeport Hospital, Waterbury Hospital, Hospital of St. Raphael, New Britain General Hospital, Norwalk Hospital, St. Vincent’s Medical Center, The Stamford Hospital, Middlesex Hospital, Mt. Sinai Hospital, St. Mary’s Hospital, Lawrence & Memorial Hospital, Manchester Hospital, Greenwich Hospital Association, Veterans Memorial Medical Center, Bristol Hospital, St. Francis Hospital and Medical Center, St. Joseph Medical Center, University of Connecticut Health Center/John Dempsey Hospital, Park City Hospital, and William W. Backus Hospital.

References

- The 1990 Census. United States Census Bureau 1990. [cited. Available from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen1990/cp1/cp-1-8.pdf.

- Breast Cancer Facts and Figures, 2000–2001. American Cancer Society; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dacey Allen J., Sorensen G, Peterson K, Stoddard AM, Colditz G. Reach Out for Health: a church-based pilot breast cancer education program, in review. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Davis DT, Bustamante A, Brown CP, Wolde-Tsadik G, Savage EW, Cheng X, Howland L. The urban church and cancer control: a source of social influence in minority communities. Public Health Rep. 1994;109:500–506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons Karen M. Health Behaviors in a Social Context. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman HP. Cancer in the socioeconomically disadvantaged. Ca-A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 1989;39:266–288. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.39.5.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg J, Curry RH. Explanatory models for cancer among African American women at two Atlanta neighborhood health centers: the implications for a cancer screening program. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;39(4):519–526. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones Beth A., Kasl Stanislav V., Curnen Mary G. M., Owens Patricia H., Dubrow Robert. Can mammography screening explain the race difference in state at diagnosis of breast cancer? Cancer. 1995;75.8:2103–2113. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950415)75:8<2103::aid-cncr2820750813>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones Beth A., Kasl Stanislav V., McCrea Curnen Mary G., Owens Patricia H., Dubrow Robert. Severe obesity as an explanatory factor for black/white difference in stage at diagnosis of breast cancer. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;146.5:394–404. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey Jennifer L., Bernstein Leslie. Epidemiology and Prevention of Breast Cancer. Annual Review of Public Health. 1996;17:47–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig Harold G., McCullough Michael E., Larson David B. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lannin Donald R., Mathews Holly F., Mitchell Jim, Swanson Melvin S., Swanson Frances H., Edwards Maxine S. Influence of socioeconomic and cultural factors on racial differences in late-stage presentation of breast cancer. JAMA. 1998;279(22):1801–1807. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.22.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Eric, Mamiya Lawrence H. The Black Church in the African American Experience. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelblatt J, Traxler M, Lakin P, Kanetsky P, Kao R. Mammography and Papanicolaou smear use by elderly poor black women: The Harlem Study Team. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992;40(10):1001–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb04476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty Martin E. Modern American Religion: The Irony of It All (1893–1919) 4 vols. Vol. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews HF, Lannin DR, Mitchell JP. Coming to terms with advanced breast cancer: black women’s narratives from Eastern North Carolina. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;38(6):789–800. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najjar MF, Rowland M. Anthropometric reference data and prevalence of overweight, United States, 1976–1980, Vital and health statistics, Series 11: Data from the National Health Survey, no. 238) Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paskett Electra D., Case L. Douglas, Tatum Cathy, Velez Ramon, Wilson Alma. Religiosity and cancer screening. Journal of Religion and Health. 1999;38(1):39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman DN, Rakowski W, Ehrich B, Clark MA. Breast cancer screening practices among black, Hispanic, and white women: reassessing differences. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1996;12(5):327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JM, Wilbur J. Adherence to breast cancer screening guidelines among African-American women of differing employment status. Cancer Nursing. 1995;18(4):258–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raboteau Albert J. The Afro-American Traditions. In: Numbers RL, Amundsen DW, editors. Caring and Curing: Health and Medicine in the Western Religious Traditions. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ransdell LB, Rehling SL. Church-based health promotion: a review of the current literature. American Journal of Health Behavior. 1996;20(4):195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ries LG, Pollack ES, Young JL., Jr Cancer patient survival: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, 1973–79. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1983;70:693–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS/STAT User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley Brian D., Syme S. Leonard. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. Introduction. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JA, Fox SA, Murata PJ. The influence of ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and psychological barriers on use of mammography. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 1991;32(2):101–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ness Peter H., Kasl Stanislav V., Jones Beth A. Religion, race, and breast cancer survival. doi: 10.2190/LRXP-6CCR-G728-MWYH. in review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon SW, Vogel VG, Halabi S, Jackson GL, Lundy RO, Peters GN. Breast cancer screening behaviors and attitudes in three racial/ethnic groups. Cancer. 1992;69(1):165–174. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920101)69:1<165::aid-cncr2820690128>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood Gina M., Keltner Betty. Sociocultural Factors and Prevention Programs Affecting the Health of Ethnic Minorities. In: Raczynski JM, DiClemente RJ, editors. Handbook of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]