Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to compare an Exercise Training Group (EX) with an Attention-Control Group (AT-C) to more specifically assess the impact of exercise training on individuals with heart failure (HF).

Methods

Forty-two individuals with HF were randomized to AT-C or EX that met with the same frequency and format of investigator interaction. Baseline, 12- and 24-week measurements of B-type naturetic peptide (BNP), 6-minute walk test (6-MWT), and the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) were obtained.

Results

BNP tended to increase in the AT-C while remaining stable in the EX over time. A clinically significant increase in 6-MWT was demonstrated by the EX but not the AT-C. The EX achieved a clinically significant change on the KCCQ at 12 weeks, with further improvement by 24 weeks, while the AT-C demonstrated a clinically significant change at 24 weeks.

Conclusions

Attention alone was inadequate to positively impact BNP levels or 6-MWT distances, but did have a positive impact on quality of life after 24 weeks. Although exercise offers enhanced benefits, individuals with HF unable to participate in an exercise program may still gain quality of life benefits from participation in a peer-support group that discusses topics pertinent to HF.

Key Words: heart failure, attention, exercise

INTRODUCTION

The hallmark symptoms associated with heart failure (HF) are dyspnea, fatigue, and exercise intolerance that impair the functional abilities and quality of life (QoL) of individuals.1 The decrease in physical activity tolerance has been attributed physiologically to a combination of central and peripheral factors.2 Physical inactivity leads to physical deconditioning that further compromises physical activity tolerance. As a result, individuals with HF face numerous lifestyle changes as a consequence of their decreased physical capacity and diminished QoL.

While the overall medical management of individuals with HF is still a work in progress, the guidelines for pharmacological therapy are now more clearly established.1,2 However, the role of nonpharmacological interventions is an area of active investigation, particularly with regard to exercise training. The HF-ACTION trial (Heart Failure: A Controlled Trial Investigating Outcomes of Exercise Training) has demonstrated the efficacy and safety of aerobic exercise training for individuals with HF along with a positive impact on QoL.3,4 The updated guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association1 and the Heart Failure Society of America2 acknowledge the potential benefits of exercise training for select individuals with HF. Furthermore, dynamic resistance exercise training has been shown to be well tolerated and is assumed to be as safe as aerobic exercise.5

Many exercise studies in HF have compared exercise training to usual care. Since sustained participation in an exercise program also requires attention to foster a change in health behavior, consideration needs to be given to designing studies that can elucidate more specifically the effect of the exercise component of the intervention from the effect of attention as a confounding factor.6 Attention may encompass face-to-face meetings, group sessions, periodic follow-up by telephone or other means of one-on-one interaction, such as email or letter correspondences, that may not be part of typical usual care. The impact of attention can blur the true effect of the intervention component of concern when the amount of attention provided to the intervention group is not taken into account.7 Therefore, careful consideration of the comparison group is necessary to account for the amount of attention, which should be provided concurrently and equivalently with the intervention group.6 This provides for a more critical assessment of the impact of the exercise component of the intervention on individuals in the exercise arm of studies. Comparisons of exercise groups to attention control groups have been performed in other patient populations but to our knowledge have not been reported in individuals with HF.8,9,10

The HEART CAMP (Heart failure Exercise And Resistance Training CAMP) intervention was designed to educate and empower individuals with HF about how to exercise and self-manage exercise behavior over time.11 Comparisons were made of the intervention group's outcomes to an attention control group's outcomes. This current study is a secondary analysis of the HEART CAMP intervention and reports the impact of exercise training, versus attention, on individuals with HF using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) to assess QoL, the 6-minute walk test (6-MWT) to assess physical function and the biomarker B-type naturetic peptide (BNP) to assess cardiac stress. Other HEART CAMP results relating self-efficacy to exercise, symptoms of dyspnea and fatigue, physical functioning measured by self-report and adherence to exercise have been previously reported.11,12

METHODS

Appropriately identified individuals from a regional HF clinic in the Midwestern United States were invited to participate in this study by their cardiologist or nurse practitioner. Forty-two individuals with HF and New York Heart Association Class II-IV volunteered for this study. Inclusion criteria included: (1) ≥ 21 years of age; (2) oriented to person, place, and time; (3) able to speak and read English; (4) resting left ventricular ejection fraction ≤ 40%; and (5) stable on optimal medical therapy for at least 30 days. Exclusion criteria included: (1) clinical evidence of decompensated HF; (2) unstable angina pectoris; (3) myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass surgery, or biventricular pacemaker < 3 months ago; (4) orthopedic or neuromuscular limitations preventing participation in aerobic or resistance exercise training; and (5) participation in an aerobic exercise program during the past 12 months. The sample size of 42 was chosen as sufficient for the study's goals of evaluating the feasibility of HEART CAMP and obtaining necessary information to estimate effect sizes for a larger study. All individuals gave informed consent to participate in this study and the rights of the subjects were protected. Following admission to the study, individuals were randomized to one of two groups, the Attention Control Group (AT-C) or the Exercise Intervention Group (EX). This study was approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center's Institutional Review Board and the Bryan-LGH Hospital's Institutional Review Board.

The study was conducted in two sequential 12 week phases. Phase 1 involved separate weekly group meetings of the AT-C and EX groups during weeks 1-3, then separate biweekly meetings during weeks 4-12. Phase 2 involved following the groups for an additional 12 weeks without group sessions.

Attention Control Group

The attention control aspect for this group involved contact with the investigators at the same frequency and duration as the EX group, and educational sessions with topics pertinent to HF (eg, medications, HF symptoms, sodium and fluid restrictions). Educational content was identical between groups with the exception of exercise specific content that was delivered to the EX group. As previously described, these topics were adapted from the educational modules from the Heart Failure Society of America.11 The AT-C group was provided with instructions to continue with their normal level of activity. No instructions were given to withhold activity or stop activity. During the AT-C group sessions participants discussed the education topics and their concerns with peers and the study investigators. Education regarding exercise was not provided to the AT-C group after the 24 week study period since these participants had not been cleared for activity through a graded exercise test.

Exercise Intervention Group

Individuals randomized to the EX group underwent a maximal effort cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) using a ramping protocol to assess for electrocardiographic and hemodynamic abnormalities to exercise.13 The individualized exercise programs for these subjects included both aerobic and resistance training components. The aerobic component consisted of exercising at an intensity of 40% to 70% heart rate reserve (HRR), based on the CPET, or at a Rating of Perceived Exertion of 11-14 on the Borg category scale. Aerobic exercise duration was for 30 minutes at the prescribed exercise intensity plus a 15 minute warm-up and 15 minute cool-down. Individuals were given personal heart rate monitors to use throughout the study to monitor their exercise intensity during training sessions. Prescribed frequency for aerobic exercise was 3 days per week. Resistance training included 8 to 10 exercises (upper and lower extremity) performed for one set of 10 to 15 repetitions, 2 days per week, using weight machines, free weights or elastic bands based on their exercise preferences. Individuals were also instructed in keeping an exercise diary, including exercise modes, duration and intensity, which was reviewed weekly with feedback provided to them from an investigator. To enhance self-efficacy and to test adherence to an exercise program, participants were only directly supervised for the first 3 weeks during their exercise program. The subjects were then oriented to the hospital's wellness center where they could continue their exercise training programs independently; alternatively, after orientation, they could perform their training programs at home.

Individuals randomized to the EX arm of the study participated in group meetings that addressed the same education topics as the AT-C group but in addition included information on problem solving barriers to exercise, relapse management, and symptoms experienced during exercise. Participants discussed concerns with their peers and the study investigators and received individual feedback data.

Outcome Measures

Individuals in both the AT-C and EX groups were tested at baseline, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks, using the identical outcome measures and procedures for each group. The BNP is a cardiac hormone produced and secreted by the ventricles in response to increased wall stress, has been shown to be elevated in proportion to the severity of HF14,15,16 and is correlated with measures of functional capacity.17,18,19 All blood samples obtained on subjects were analyzed for BNP within 10 minutes of collection using a commercially available immunoflurometric assay (Triage BNP, Biosite Diagnostics, San Diego CA) and reported in pg/ml. Each individual also performed a single 6-MWT at each test point using a standardized protocol adapted from the American Thoracic Society guidelines.20 A 50 foot distance was measured and clearly marked in a hospital corridor. Individuals were instructed to walk from one end of the marked distance to the other end and back, at their own pace, trying to cover as much distance as possible. The test was supervised by an investigator with standardized verbal encouragement provided every minute. Total distance covered in 6 minutes was measured and recorded. The KCCQ overall summary score, which includes the physical limitation, symptoms, social limitation, and quality of life subscales, was used in this study for comparisons.21 This instrument has been found to be valid and reliable (Cronbach's alpha= 0.93-0.95), and sensitive to changes in clinical status of individuals with HF.4,22,23,24

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons of group baseline measures were performed by chi-square and t-test analyses. Within each intervention group, distributions of each outcome at each measurement time were evaluated for non-normality and outliers. A logarithmic transformation was applied to BNP to normalize the distributions.

Because this study was planned and funded as a pilot/feasibility study, it was not fully powered to detect a meaningful effect size. Although setting α ≤ .05 is the conventional practice, some researchers have argued that in applied research, especially with small samples, less stringent control of Type I error can be justified when weighed against the risk of prematurely dismissing a potential effective intervention.25,26,27,28 We believe this to be the case in this study and so used a liberal α level of .10 in all statistical analyses, along with consideration of the practical importance of the observed effect sizes.

Patients in both the EX and AT-C conditions were assigned to small groups that completed the study as a cohort. To take into account that individuals within the same small group can be expected to influence each other, change over time in the intervention conditions was compared using a traditional repeated-measures ANOVA with small-group assignment as a nested random factor. The effect of Group X Time was tested by creating a quasi-F statistic using the interaction of the nested factor with time as an error term. Additional details of the analysis are reported elsewhere.11 Significant interactions were followed up using tests of simple main effects of time within group, with cohort retained as a nested random factor. The formal statistical tests were supplemented with boxplots of differences from baseline to 12 weeks and baseline to 24 weeks to aid interpretation of the clinical importance of the changes on the individual level.

RESULTS

Of the 42 subjects (AT-C: n=20 and EX: n=22) recruited, 40 completed the 24-week protocol (AT-C: n=20 and EX: n=20). Two subjects in the EX group were lost to follow up at 24 weeks; one subject died of a cause unrelated to his HF, and a second subject stopped participating and did not respond to our follow up contact efforts. Subject demographics are summarized in Table 1, with no significant differences noted between groups. As previously published, participants in the EX group demonstrated a 73% adherence rate over the 24-week period to the exercise sessions and maintained their exercise duration and intensity at or slightly above goal level, while completing training sessions on average of 3.6 days per week.12

Table 1.

Subject Demographics

| Subjectsc (n=40) | Control Group Mean (± SEM) | Exercise Group Mean (± SEM) | Test Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Males/Females) | 12/8 | 11/9 | χ2 = < .005 | 1.00 |

| Age (yrs) | 63.0 (± 3.4) | 56.0 (± 2.7) | t = 1.63 | .11 |

| LVEF(%) | 32.3 (± 1.2) | 34.0 (± 1.4) | t = .95 | .35 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 33.2 (± 1.7) | 33.0 (± 1.9) | t = .10 | .92 |

LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction, BMI = body mass index

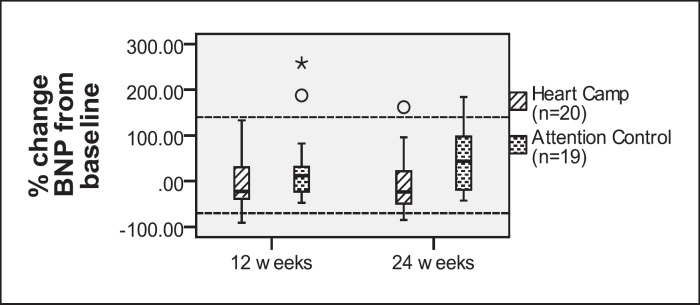

The mean log transformed BNP levels obtained at baseline, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks for both groups are listed in Table 2. The Group X Time interaction was significant (p = .07). Simple main effects tests showed significant change for the EX [F (2, 4) = 10.00, p = .03], but not for the AT-C [F (2, 4) = 1.00, p = .44]. To further categorize the changes in BNP over time, we calculated the percent change from baseline to 12 weeks and baseline to 24 weeks; the results are displayed in Figure 1. The AT-C group demonstrated an increasing trend over time with median BNP increasing at 12 weeks and again at 24 weeks when compared to baseline. The BNP levels remained more stable over time in the EX group with the majority of patients showing a slight decrease in BNP over time compared to baseline.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Results of RM-ANOVA for 6 Minute Walk Test, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire and B-type Naturetic Peptide

| 6 MWT* | n | Baseline Mean ± SD (m) | 12 week Mean ± SD | 24 week Mean ± SD | Fa | p | η2b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX* | 19 | 408.3 ± 59.8 | 448.4 ± 68.9 | 463.0 ± 63.0 | |||

| AT-C* | 20 | 352.3 ± 80.0 | 378.4 ± 89.1 | 384.6 ± 91.7 | |||

| Time | 14.37 | <.01 | .38 | ||||

| Group X Time | .99 | .41 | .03 | ||||

| Cohort (Group) X Time | 1.46 | .19 | .01 | ||||

| KCCQ* (total score) | |||||||

| EX | 19 | 69.7 ± 20.2 | 78.1 ± 18.1 | 81.0 ± 18.2 | |||

| AT-C | 18 | 72.8 ± 15.6 | 76.0 ± 17.0 | 77.9 ± 11.6 | |||

| Time | 17.58 | <.01 | .23 | ||||

| Group X Time | 1.98 | .20 | .03 | ||||

| Cohort (Group) X Time | .60 | .78 | .05 | ||||

| BNP* (log transformed)c | |||||||

| EX | 20 | 1.80 ± .46 | 1.68 ± .53 | 1.68 ± .52 | |||

| AT-C | 19 | 1.99 ± .53 | 2.02 ± .51 | 2.09 ± .49 | |||

| Time | 1.00 | .41 | .02 | ||||

| Group X Time | 3.91 | .07 | .08 | ||||

| Cohort (Group) X Time | .87 | .55 | .09 | ||||

* 6-MWT = 6 Minute Walk Test, KCCQ = Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, BNP = B-type Naturetic Peptide, EX = Exercise Intervention Group, AT-C = Attention Control Group

aThe Time and Group X Time effects are each tested using the mean square of the Cohort (Group) X Time effect as the denominator (df=2,8). The Cohort (Group) X Time effect was tested using the residual mean square error (dfnumerator = 8, dfdenominator ranged from 62 to 66).

bEstimate of effect size: η2 calculated using total within-subjects sum-of-squares as the denominator.

cRaw BNP means (SD) at baseline, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks for Heart Camp: 103.2 (108.5), 83.7 (85.3), 90.4 (102.9); for Attention Control: 175.1 (182.2), 162.5 (157.9), 201.8 (214.7).

Figure 1.

Boxplot depicting the Heart Camp and Attention Control Groups % Change in BNP. The bottom and top of the box are the 25th and 75th percentile (the lower and upper quartiles, respectively), and the dark line within the box represents the 50th percentile (median). The ends of the whiskers indicate the lowest datum still within 1.5 times the interquartile range of the lower quartile, and the highest datum still within 1.5 times the interquartile range of the upper quartile. Circles indicate outliers with values between 1.5 and 3 boxlengths outside the box. Stars indicate extreme values > 3 box lengths outside the box. The upper dashed reference line at 140% indicates a clinically important decline and lower dashed reference line at −70% indicates a clinically important improvement.

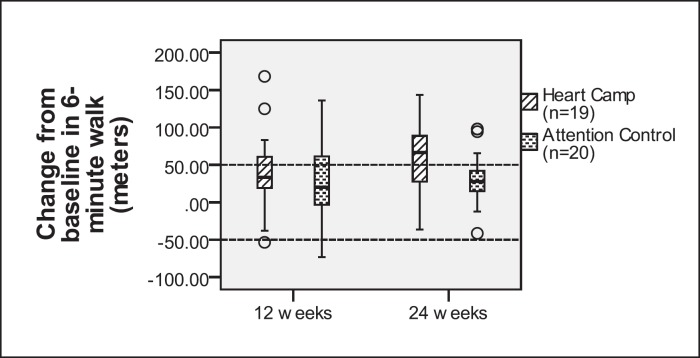

The pattern of change in the 6-MWT distances from baseline through 24 weeks was not significantly different for the AT-C and EX groups (p = .41). The mean distance increased significantly in both groups (Table 2). However, on average, the improvement by 24 weeks in the EX group did reach a clinically important level (55.7 meters) of change while the mean in the AT-C group did not (32.3 meters). The boxplots in Figure 2 suggest that many individuals in the EX group improved function from 12 to 24 weeks, while those in the AT-C group tended to plateau.

Figure 2.

Boxplot depicting the Heart Camp and Attention Control Groups Change in 6-Minute Walk Test. The bottom and top of the box are the 25th and 75th percentile (the lower and upper quartiles, respectively), and the dark line within the box represents the 50th percentile (median). The ends of the whiskers indicate the lowest datum still within 1.5 times the interquartile range of the lower quartile, and the highest datum still within 1.5 times the interquartile range of the upper quartile. Circles indicate outliers with values between 1.5 and 3 boxlengths outside the box. The dashed reference lines at +/− 50 meters represent clinically important improvement or decline.

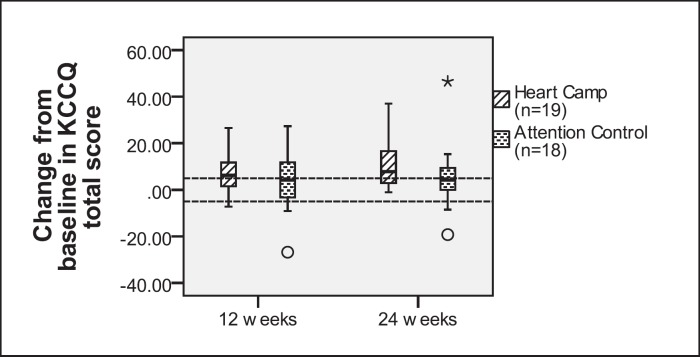

The serial changes in health related quality of life based on the KCCQ summary score were significant (Table 2), but the amount of change did not differ statistically between the two groups (interaction p = .20). Descriptively, the increase in mean score for the EX group was approximately 11 points compared to 5 points in the AT-C group. Distributions of individual changes are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Boxplot depicting the Heart Camp and Attention Control Groups Change in KCCQ Total Score. The bottom and top of the box are the 25th and 75th percentile (the lower and upper quartiles, respectively), and the dark line within the box represents the 50th percentile (median). The ends of the whiskers indicate the lowest datum still within 1.5 times the interquartile range of the lower quartile, and the highest datum still within 1.5 times the interquartile range of the upper quartile. Circles indicate outliers with values between 1.5 and 3 boxlengths outside the box. Stars indicate extreme values > 3 box lengths outside the box. The dashed reference lines at +/− 5 points represent clinically important improvement or decline.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the HEART CAMP intervention in individuals with HF using a design intended to control for the nonspecific treatment effect of attention. Our findings allowed us to more specifically assess the effect of exercise on cardiac stress, physical function, and quality of life.

The percent change in BNP over time was assessed to evaluate the magnitude and direction of change. The reference change value (RCV) represents the magnitude of change needed in order to ascertain a clinically meaningful change.29 For the Triage BNP assay method the RCV has been reported to be approximately 70%.29,30 Thus a 70% decrease in BNP would be needed to indicate a clinical improvement, or an increase of 140% (2 × RCV) to suggest clinical progression of the HF.30 Though this study was under-powered to definitively address the effect of exercise on BNP, a clear trend emerged demonstrating an overall increase in the AT-C group (+ 44%) and decrease in the EX group (-5%) at 24 weeks compared to baseline.

Studies comparing changes in BNP levels following exercise training have demonstrated various results.31,32,33 Passino et al31 found a mean decrease of 34% in BNP level with a 9-month cycling program performed for 30 minutes 3 days a week compared to usual care which increased 7%. Likewise, Parrinello et al32 reported a 19% decrease in BNP levels in their training group performing a 10-week walking program for 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week, compared to a 14% increase in their control group. These studies, like the current study, showed a statistically significant change in BNP, and a trend towards lower BNP levels with training, but did not achieve a percent change as large as the RCV. The findings of this current study showed a similar direction of change in BNP to that reported in the above studies. Butterfield et al33 did not find a significant change in BNP following a 12-week combined aerobic and resistance circuit training program but did observe that the majority of subjects in the exercise group (73%) showed a decrease in BNP while the majority in the control group (67%) exhibited an increase in BNP. Jónsdóttir et al34 found no significant changes in mean BNP in the control (+ 2%) or exercise group (− < 1%) following a 5-month combined aerobic and resistance exercise program. Our findings are consistent with the above investigators’ findings indicating exercise training does not have a deleterious effect on ventricular wall stress. In addition, we found providing attention alone did not have a positive impact on this physiological marker.

The 6-MWT is a valid and responsive measure used t assess changes in functional performance.22,35,36 In a review by Rasekaba et al,37 a change in 6-MWT in excess of 50 meters generally indicates a substantial and clinically significant change in walking capacity for individuals with cardiopulmonary diseases. Spertus et al22 reported that a change of 55 meters was associated with a moderate effect on improvement in clinical status of individuals with HF. Ingle et al36 found an increase in walking distance of 54 meters was associated with a clinically significant improvement in HF symptom score while a decrease of 84 meters was associated with a worsening of symptoms. The study by O'Keefe et al35 reported a minimum clinically significant change of 47 meters on the 6-MWT was associated with a significant improvement in QoL of older individuals with HF. In the current study, attention alone was not adequate to achieve a clinically significant difference in 6-MWT distance, however, exercise training with attention showed a 75% increase over attention alone and achieved the minimum clinically significant level of change.

A 5 point difference on the KCCQ summary score is indicative of a clinically significant change in HF status.22 Serial monitoring has demonstrated a linear relationship to all-cause mortality and hospitalization for each 5 point change in KCCQ summary score.38 In the HF-ACTION study, 3 months of exercise training resulted in a significant increase in the KCCQ summary score (+ 5.21 points) from baseline while the usual care group demonstrated a much smaller increase (+3.28 points).4 The difference in scores within the HF-ACTION groups was statistically significant at 3 months with no further significant changes noted.4

Our findings demonstrated similar results to those reported by Flynn et al.4 At 3 months our EX group had a clinically significant change in KCCQ summary score (+8.4 points) while the AT-C group did not (+3.2 points). However, over the subsequent 3 months the AT-C group's score increased to 5.1 points over baseline indicating a clinically significant improvement and the EX group further increased to 11.3 points over baseline. Though the AT-C group showed a clinically significant change by 24 weeks, the EX group had a mean 6.2 point increase over that of the AT-C group. It appears that attention alone can have a clinically significant impact on QoL, however, the combination of exercise training with attention is superior and can improve QoL at 12 weeks with further clinically significant improvement when sustained for 24 weeks.

Limitations of the Study

Due to the small, racially homogenous sample (primarily Caucasians), the generalizability of the findings of this study to the HF population overall may be limited. Though not an inclusion or exclusion criterion, all subjects had systolic HF and therefore the applicability of these findings to individuals with diastolic dysfunction is not known. In addition to limiting the power of the statistical tests, the small sample size restricted options for incorporating the nested aspect of the design into the analysis. A larger sample would allow use of methods such as linear mixed models that would be more flexible in terms of modeling error structures and including partial cases.

CONCLUSIONS/SUMMARY

Comparison of the HEART CAMP intervention to attention alone demonstrated (1) attention alone was inadequate to have a positive effect on the physiological marker plasma BNP, (2) exercise training did not have a deleterious effect on ventricular wall stress, (3) attention alone can have a positive impact on QoL over time, however, the combination of exercise and attention has a much greater impact, and (4) 6-MWT distances increased in both groups but only the EX group achieved a clinically significant improvement. Therefore, individuals with HF who do not wish to participate, or are unable to participate in an exercise training program may possibly gain benefits in their QoL from participation in a peer-support group that discusses topics pertinent to HF. Clinicians should be cognizant of these findings related to QoL and not hesitate to recommend patients to participate in HF support groups. However, exercise training, which was a critical component in the HEART CAMP intervention, is necessary for achieving clinically significant benefits in both physical function and QoL.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was fund by an R-15 AREA Grant from the National Institute of Health (# NR009215-01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American heart association task force on practice guidelines developed in collaboration with the international society for heart and lung transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:e1–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heart Failure Society of America. Lindenfeld J, Albert NM, et al. HFSA 2010 comprehensive heart failure practice guideline. J Card Fail. 2010;16:e1–194. [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, et al. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1439–1450. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flynn KE, Pina IL, Whellan DJ, et al. Effects of exercise training on health status in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1451–1459. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer K. Resistance exercise in chronic heart failure-landmark studies and implications for practice. Clin Invest Med. 2006;29:166–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindquist R, Wyman JF, Talley KM, Findorff MJ, Gross CR. Design of control-group conditions in clinical trials of behavioral interventions. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39:214–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarney R, Warner J, Iliffe S, van Haselen R, Griffin M, Fisher P. The Hawthorne effect: A randomised, controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin JE, Dubbert PM, Cushman WC. Controlled trial of aerobic exercise in hypertension. Circulation. 1990;81:1560–1567. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.5.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckelew SP, Conway R, Parker J, et al. Biofeedback/relaxation training and exercise interventions for fibromyalgia: A prospective trial. Arthritis Care Res. 1998;11:196–209. doi: 10.1002/art.1790110307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penninx BW, Messier SP, Rejeski WJ, et al. Physical exercise and the prevention of disability in activities of daily living in older persons with osteoarthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2309–2316. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.19.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pozehl B, Duncan K, Hertzog M, Norman JF. Heart failure exercise and training camp: Effects of a multicomponent exercise training intervention in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2010;39:S1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan K, Pozehl B, Norman JF, Hertzog M. A self-directed adherence management program for patients’ with heart failure completing combined aerobic and resistance exercise training. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24(4):207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arena R, Humphrey R, Peberdy MA, Madigan M. Predicting peak oxygen consumption during a conservative ramping protocol: Implications for the heart failure population. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2003;23:183–189. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200305000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yasue H, Yoshimura M, Sumida H, et al. Localization and mechanism of secretion of B-type natriuretic peptide in comparison with those of A-type natriuretic peptide in normal subjects and patients with heart failure. Circulation. 1994;90:195–203. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silver MA, Maisel A, Yancy CW, et al. BNP consensus panel 2004: A clinical approach for the diagnostic, prognostic, screening, treatment monitoring, and therapeutic roles of natriuretic peptides in cardiovascular diseases. Congest Heart Fail. 2004;10:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2004.03271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daniels LB, Maisel AS. Natriuretic peptides. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2357–2368. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruger S, Graf J, Kunz D, Stickel T, Hanrath P, Janssens U. Brain natriuretic peptide levels predict functional capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:718–722. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams SG, Ng LL, O'Brien RJ, Taylor S, Li YF, Tan LB. Comparison of plasma N-brain natriuretic peptide, peak oxygen consumption, and left ventricular ejection fraction for severity of chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1560–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Passino C, Poletti R, Bramanti F, Prontera C, Clerico A, Emdin M. Neuro-hormonal activation predicts ventilatory response to exercise and functional capacity in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City cardiomyopathy questionnaire: A new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spertus J, Peterson E, Conard MW, et al. Monitoring clinical changes in patients with heart failure: A comparison of methods. Am Heart J. 2005;150:707–715. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spertus JA, Jones PG, Kim J, Globe D. Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the Kansas City cardiomyopathy questionnaire in anemic heart failure patients. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:291–298. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9302-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eurich DT, Johnson JA, Reid KJ, Spertus JA. Assessing responsiveness of generic and specific health related quality of life measures in heart failure. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:89. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipsey MW. Design Sensitivity: Statistical Power for Experimental Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Judd CM, McClelland GH, Culhane SE. Data analysis: Continuing issues in the everyday analysis of psychological data. Ann Review Psychol. 1995;46:433–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.46.020195.002245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kramer SH, Rosenthal R. Effect sizes and significance levels in small-sample research. Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research. 1999. pp. 59–79.

- 28.Stevens J. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences. 5th ed. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Hanlon R, O'Shea P, Ledwidge M, et al. The biologic variability of B-type natriuretic peptide and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide in stable heart failure patients. J Card Fail. 2007;13:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu AH. Serial testing of B-type natriuretic peptide and NTpro-BNP for monitoring therapy of heart failure: The role of biologic variation in the interpretation of results. Am Heart J. 2006;152:828–834. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Passino C, Severino S, Poletti R, et al. Aerobic training decreases B-type natriuretic peptide expression and adrenergic activation in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1835–1839. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parrinello G, Torres D, Paterna S, Di Pasquale P, Trapanese C, Licata G. Short-term walking physical training and changes in body hydration status, B-type natriuretic peptide and C-reactive protein levels in compensated congestive heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2010;144:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.12.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butterfield JA, Faddy SC, Davidson P, Ridge B. Exercise training in patients with stable chronic heart failure: Effects on thoracic impedance cardiography and B-type natriuretic peptide. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2008;28:33–37. doi: 10.1097/01.HCR.0000311506.49398.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jonsdottir S, Andersen KK, Sigurosson AF, Sigurosson SB. The effect of physical training in chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Keeffe ST, Lye M, Donnellan C, Carmichael DN. Reproducibility and responsiveness of quality of life assessment and six minute walk test in elderly heart failure patients. Heart. 1998;80:377–382. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.4.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ingle L, Shelton RJ, Rigby AS, Nabb S, Clark AL, Cleland JG. The reproducibility and sensitivity of the 6-min walk test in elderly patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1742–1751. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rasekaba T, Lee AL, Naughton MT, Williams TJ, Holland AE. The six-minute walk test: A useful metric for the cardiopulmonary patient. Intern Med J. 2009;39:495–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kosiborod M, Soto GE, Jones PG, et al. Identifying heart failure patients at high risk for near-term cardiovascular events with serial health status assessments. Circulation. 2007;115:1975–1981. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.670901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]