Abstract

Background: Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) represents one of the most frequently psychiatric sequelae to earthquake exposure. Increasing evidence suggests the onset of maladaptive behaviors among veterans and adolescents with PTSD, with specific gender differences emerging in the latter. Aims of the present study were to investigate the relationships between maladaptive behaviors and PTSD in earthquake survivors, besides the gender differences in the type and prevalence of maladaptive behaviors and their association with PTSD. Methods: 900 residents of the town of L’Aquila who experienced the earthquake of April 6th 2009 (Richter Magnitude 6.3) were assessed by means of the Trauma and Loss Spectrum-Self Report (TALS-SR). Results: Significantly higher maladaptive behavior prevalence rates were found among subjects with PTSD. A statistically significant association was found between male gender and the presence of at least one maladaptive behavior among PTSD survivors. Further, among survivors with PTSD significant correlations emerged between maladaptive coping and symptoms of re-experiencing, avoidance and numbing, and arousal in women, while only between maladaptive coping and avoidance and numbing in men. Conclusions: Our results show high rates of maladaptive behaviors among earthquake survivors with PTSD suggesting a greater severity among men. Interestingly, post-traumatic stress symptomatology appears to be a better correlate of these behaviors among women than among men, suggesting the need for further studies based on a gender approach.

Keywords: PTSD, post-traumatic stress symptoms, earthquake, maladaptive behaviors, gender

Introduction

Earthquakes are one of the most frequent natural disasters occurring across the world and, among exposed individuals, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) represents the most frequently occurring psychiatric sequelae (Maj et al., 1989; Armenian et al., 2002; Lai et al., 2004; Jahangiri et al., 2010; Dell’Osso et al., 2011a; Hussain et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011; Ali et al., 2012).

There is increasing evidence in the literature on the specific clinical and neurobiological correlates of PTSD and particularly, on the specific gender differences in PTSD prevalence rates, with women being more affected than men across different cultures and at different ages (Armenian et al., 2000; Kessler, 2000; Green, 2003; Cohen, 2008; Liberzon and Sripada, 2008; Alhasnawi et al., 2009; Dell’Osso et al., 2010, 2011a,b; Pratchett et al., 2010; Friedman et al., 2011; Rabinak et al., 2011; Sherin and Nemeroff, 2011; Xu and Song, 2011). Increasing data agree on the tendency to a chronic course, higher incidence of alcohol and substance abuse and heightened risk for suicide in PTSD patients (Kessler, 2000; Krysinska and Lester, 2010; McFarlane, 2010; Jessup et al., 2012; Pietrzak et al., 2012). However, data on mass trauma survivors, particularly on earthquake victims, are scarce (Shimizu et al., 2000; Vlahov et al., 2002; Chang et al., 2005; Vehid et al., 2006; Cerdá et al., 2011; Dell’Osso et al., 2011a; Pollice et al., 2011; Stratta et al., 2012) and little is known on other possible maladaptive behaviors that may be developed and on any eventual gender differences (McMillen et al., 2000; Bal and Jensen, 2007; Goenjian et al., 2009; Cairo et al., 2010; Dell’Osso et al., 2011a, 2012).

Maladaptive behaviors are defined as volitional behaviors whose outcome is uncertain and which entail negative consequences that impact everyday activities (Irwin, 1990; Pat-Horenczyk et al., 2007; Hartley et al., 2008; Dell’Osso et al., 2012). Anecdotal data have been reported on maladaptive behaviors, such as risk-taking behaviors, dangerous driving, or promiscuous sex emerging in patients with PTSD. Aggressive and unsafe driving has been reported amongst male veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, with PTSD severity being associated to aggressive driving but not other forms of unsafe driving (Kuhn et al., 2010). Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans with PTSD also showed significantly higher rates of aggressive traits, including violent behaviors, compared to those without PTSD (Jakupcak et al., 2007; Elbogen et al., 2010). More data have been reported on risk-taking behaviors, such as smoking, alcohol, and substance use, car racing, weapon carrying, violence, and delinquency among adolescents and young adults with PTSD due to terrorism, fire, or violence. Interestingly, in these studies higher rates have been reported in victims with PTSD compared to non-affected subjects, with boys reporting significantly higher rates than girls (Glodich and Allen, 1998; Sugar, 1999; Gore-Feltun and Koopman, 2002; Steven et al., 2003). Considering the relevance of these conditions, particularly that of substance use disorders when co-occurring with mood or anxiety disorders (Sbrana et al., 2005; Bizzarri et al., 2007; Maremmani et al., 2012), further studies are warranted on PTSD.

Despite the fact that literature has been increasingly focused on post-traumatic stress reactions emerging in general population samples of earthquake adult survivors, to the best of our knowledge no study has yet explored gender differences in maladaptive behaviors occurring in these patients. On April 6th 2009, at 3:32 a.m., an earthquake of magnitude 6.3 on the Richter scale struck L’Aquila, Italy, a town with a population of 72,000 inhabitants, with a massive destroying effect on buildings, inducing the death of 309 people and the injury of more than 1,600. Furthermore, after this event continuous tremors have been going on in the town of L’Aquila and still present today. In a previous study on 512 students who survived the earthquake 10 months earlier (Dell’Osso et al., 2011a), we reported PTSD prevalence rates as high as 37.5%, with significantly higher rates of maladaptive behaviors among boys compared to girls.

Aims of the present study were to investigate the relationships between maladaptive behaviors and PTSD in earthquake survivors, besides the gender differences in the type and prevalence of maladaptive behaviors and their association with PTSD. With these aims in view, we investigated 900 L’Aquila residents who experienced the earthquake of April 6th 2009.

Materials and Methods

Study participants

The target population included residents of the town of L’Aquila, who lived in the urban area of the town and experienced the earthquake of April 6th 2009. Ten months earlier, all residents of the town of L’Aquila were directly exposed to the disaster, had received assistance in the emergency conditions that prevailed and were displaced in locations within a 150 km area from the town or in tents located in the urban area. Even 10 months after the earthquake, only 25% of the inhabitants were able to return to their homes.

The instruments were administered to an original sample of 939 subjects but complete data were available for 900 subjects, 446 women and 454 men. Within the whole sample, 372 survivors reported PTSD, 122 men and 250 women. Patients with PTSD had a mean age of 24.90 ± 12.15, 26.17 ± 13.6, 24.28 ± 11.35 years in the total sample and among men and women respectively.

Symptoms of post-traumatic stress related to the earthquake were explored on the Trauma and Loss Spectrum-Self Report (TALS-SR, Dell’Osso et al., 2008, 2009).

The Ethics Committee of the University of L’Aquila approved all recruitment and assessment procedures. Eligible subjects provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study and having an opportunity to ask questions.

Instruments and assessments

The TALS-SR was developed by researchers who comprise the Italian-American team belonging to the so-called Spectrum-Project (Frank et al., 1998; Cassano et al., 1999). The TALS-SR includes 116 items exploring the lifetime experience of a range of loss and/or traumatic events and lifetime symptoms, behaviors and personal characteristics that might represent manifestations and/or risk factors for the development of a stress response syndrome. Items responses are coded dichotomously (yes/no). The instrument is organized into nine domains and domain scores are obtained by counting the number of positive answers. In accordance with the aims of the present study subjects were asked to fulfill domains V, VI, VII, and VIII, referring symptoms that occurred after earthquake exposure. Domain V (“Re-experiencing”), domain VI (“Avoidance and numbing”), and domain VIII (“Arousal”) include re-experiencing, avoidance and numbing, and arousal symptoms respectively. Domain VII (“Maladaptive copying”) targets maladaptive coping and behaviors including: no self-care, scarce adherence to on-going medications, alcohol or drug abuse, risk-taking behaviors (dangerous driving, promiscuous sex, etc.), thoughts of death, suicidal ideations, and attempts. Each items explores whether these occurred after exposure to loss or trauma.

The presence of PTSD was assessed by means of the TALS-SR items corresponding to DSM-IV-TR criteria for PTSD diagnosis (Dell’Osso et al., 2011a,b). A diagnosis of partial PTSD was assessed when criteria B and or C or D for DSM-IV were satisfied. According to the aim of the present study we also analyzed the prevalence rates of endorsement of the items of the TALS-SR on domain VII.

In order to explore the association between maladaptive behaviors, gender, and PTSD, we adopted also a dichotomic variable indicating the presence of at least one of the maladaptive behaviors in each subject.

Statistical analyses

We utilized the Chi-Square test to examine PTSD and gender differences in the rates of endorsement of maladaptive behaviors. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to: (1) study the association between gender and PTSD and their possible interaction in predicting the presence of at least one maladaptive behavior; (2) identify the maladaptive behaviors items that best predicted gender.

Pearson correlation coefficients were adopted to explore the association between PTSD symptoms, determined by means of the TALS-SR domains IV, V, and VI total scores, and maladaptive behaviors, determined by means of the TALS-SR domain VII total score.

All statistical analyses were carried out using Statistical Package for Social Science, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago 2010).

Results

Earthquake survivors with PTSD reported significantly higher prevalence rates of maladaptive behaviors than those without PTSD (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Maladaptive behaviors (TALS-SR Domain VII) prevalence rates in 900 L’Aquila earthquake survivors: PTSD vs. No PTSD.

| TALS-SR domain VII (maladaptive copying) | PTSD (N = 372) N (%) | No PTSD (N = 528) N (%) | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 97. …Stop taking care of yourself, for example, not getting enough rest or not eating right? | 164 (44.1) | 59 (11.2) | 125.07 | <0.001 |

| 98. …Stop taking prescribed medications or fail to follow-up with medical recommendations, such as appointments, diagnostic tests, or a diet? | 39 (10.5) | 14 (2.7) | 22.77 | <0.001 |

| 99. …Use alcohol or drugs or over-the-counter medications to calm yourself or to relieve emotional or physical pain? | 87 (23.4) | 59 (11.2) | 22.94 | <0.001 |

| 100. …Engage in risk-taking behaviors, such as driving fast, promiscuous sex, hanging out in dangerous neighborhoods? | 55 (14.8) | 44 (8.3) | 8.63 | =0.003 |

| 101. …Wish you hadn’t survived? | 64 (17.2) | 34 (6.4) | 24.97 | <0.001 |

| 102. …Think about ending your life? | 32 (8.6) | 15 (2.8) | 13.57 | <0.001 |

| 103. …Intentionally scratch, cut, burn, or hurt yourself? | 34 (9.1) | 15 (2.8) | 15.62 | <0.001 |

| 104. …Attempt suicide? | 19 (5.1) | 10 (1.9) | 6.27 | =0.012 |

A multiple logistic regression showed a statistically significant interaction gender * PTSD in predicting the presence of at least one maladaptive behavior (see Table 2). Indeed, the prevalence of at least one of the maladaptive behaviors is significantly higher in men than in women among survivors with PTSD only (69.4% vs. 56.6%, p = 0.024).

Table 2.

Binary logistic regression analysis (PTSD and gender as predictors of at least one maladaptive behavior) applied to 372 L’Aquila earthquake survivors with PTSD.

| B (SE) | Odds ratio | C.I.95% | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −0.98 (0.13) | <0.001 | ||

| PTSD | 1.80 (0.23) | 6.06 | 3.84–9.58 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 0.13 (0.20) | 1.14 | 0.77–1.68 | =0.509 |

| PTSD by Gender | −0.68 (0.31) | 0.51 | 0.28–0.92 | =0.026 |

(χ2 = 101.60, p < 0.001, Cox R2 = 0.11, Negelkerke R2 = 0.14).

O.R., odds ratio; C.I., coefficient interval.

In particular, men reported statistically significant higher endorsement rates in items N = 98 (“Stop taking prescribed medications or fail to follow-up with medical recommendations…?,” χ2 = 7.73; p = 0.005), N = 99 (“Use alcohol or drugs or over-the-counter medications to calm yourself …?,” χ2 = 8.19; p = 0.004), N = 100 (“Engage in risk-taking behaviors…?,” χ2 = 29.52; p < 0.001), N = 103 (“Intentionally scratch, cut, burn or hurt yourself…?,” χ2 = 12.84; p < 0.001), and N = 104 (“Attempt suicide…?,” χ2 = 26.80; p < 0.001) of the TALS-SR (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Maladaptive behaviors (TALS-SR Domain VII) prevalence rates in 372 L’Aquila earthquake survivors with PTSD: gender differences.

| TALS-SR Domain VII (Maladaptive copying) | Men (N = 122) N (%) | Women (N = 250) N (%) | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 97. …Stop taking care of yourself, for example, not getting enough rest or not eating right? | 51 (41.8) | 113 (45.2) | 0.26 | 0.611 |

| 98. …Stop taking prescribed medications or fail to follow-up with medical recommendations, such as appointments, diagnostic tests, or a diet? | 21 (17.2) | 18 (7.2) | 7.73 | 0.005 |

| 99. …Use alcohol or drugs or over-the-counter medications to calm yourself or to relieve emotional or physical pain? | 40 (32.8) | 47 (18.8) | 8.19 | 0.004 |

| 100. …Engage in risk-taking behaviors, such as driving fast, promiscuous sex, hanging out in dangerous neighborhoods? | 36 (29.5) | 19 (7.6) | 29.52 | <0.001 |

| 101. …Wish you hadn’t survived? | 23 (18.9) | 41 (16.4) | 0.20 | 0.658 |

| 102. …Think about ending your life? | 15 (12.3) | 17 (6.8) | 2.451 | 0.117 |

| 103. …Intentionally scratch, cut, burn, or hurt yourself? | 21 (17.2) | 13 (5.2) | 12.84 | <0.001 |

| 104. …Attempt suicide? | 17 (14.0) | 2 (0.8) | 26.80 | <0.001 |

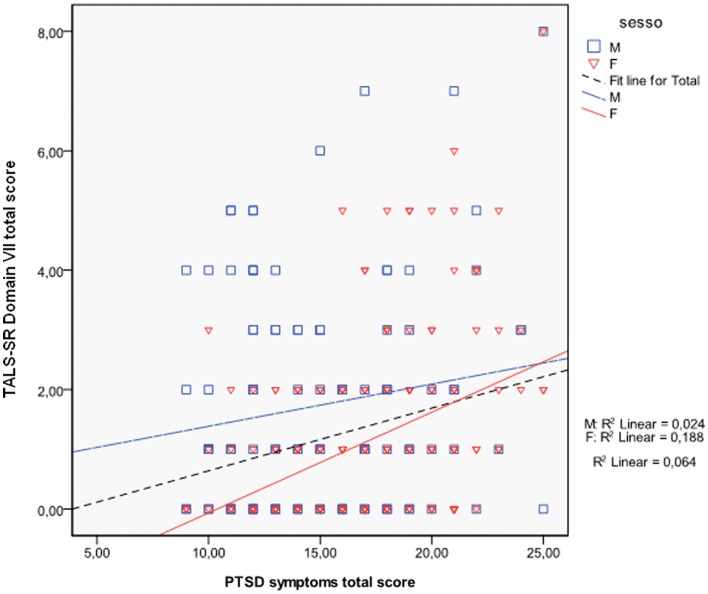

The Scattergram reported in Figure 1 shows the differential association between maladaptive behaviors, evaluated by adopting TALS-SR domain VII total scores, gender, and PTSD symptoms, evaluated by the sum of TALS-SR domains V (Re-experiencing), VI (Avoidance and numbing), and VIII scores (Arousal). In particular, a moderate Pearson correlation coefficient with PTSD symptoms, between moderate and good, emerged in women (r = 0.43, p < 0.001) but not in men (r = 0.15, p = 0.097). To note, in women significant correlations also emerged between maladaptive coping and each of the total scores of the three symptomatological domains (domain V Re-experiencing, r = 0.23, p < 0.001; domain VI Avoidance and numbing, r = 0.44, p < 0.001; domain VIII Arousal, r = 0.25, p < 0.001) while in men, a significant correlation emerged with domain VI only (r = 0.31 p = 0.001).

Figure 1.

Gender differences in the correlations between post-traumatic stress symptoms and TALS-SR domain VII total score.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first population-based study exploring gender impact on the maladaptive behavioral sequelae of a major earthquake. Unlike other studies that have explored maladaptive behaviors in special populations, such as veterans or adolescents (Glodich and Allen, 1998; Sugar, 1999; Gore-Feltun and Koopman, 2002; Steven et al., 2003; Jakupcak et al., 2007; Pat-Horenczyk et al., 2007; Elbogen et al., 2010; Kuhn et al., 2010; Dell’Osso et al., 2011a), we examined a sample of Italian civilian survivors to the earthquake that massively affected the town of L’Aquila in April 2009.

Our results indicate an alarming rate of self-reported maladaptive behaviors by L’Aquila earthquake survivors 10 months after the event occurred, with significantly higher rates among victims reporting PTSD compared to those without. In an exploration of substance abuse among young people exposed to this same event, Pollice et al. (2011) brought to light a marked increase in levels of abuse compared to prior to the trauma. Our data show significantly higher rates of alcohol or drug abuse in earthquake survivors with PTSD, reported in the aftermath of the event, with rates as high as more than 20%, compared to survivors who did not report PTSD presenting rates around 10%. Almost half of PTSD survivors also reported a decrease in self-care (e.g., not getting enough rest, not eating properly), with more than 10% reporting suspension of on-going treatments or medical recommendations. In line with previous studies on war veterans and adolescents (Glodich and Allen, 1998; Sugar, 1999; Gore-Feltun and Koopman, 2002; Steven et al., 2003; Jakupcak et al., 2007; Cepeda et al., 2010; Elbogen et al., 2010) we found significantly higher rates of risk-taking behaviors (such as unsafe driving, promiscuous sex) among survivors with PTSD. Further, more than one third of these subjects also reported at least one endorsement among items exploring suicidal ideation or attempts.

Significant gender differences emerged among survivors with PTSD, with men reporting significantly higher rates of maladaptive behaviors than women. In particular, we found that men reported significantly more than women interruption of on-going treatments, alcohol, or drug abuse, or over-the-counter medication use to calm themselves, risk-taking behaviors, including self-injuring and suicide attempts. In a previous study, some of our group (Rossi et al., 2011) compared the rates of new psychopharmacological prescriptions in the 6 months after the L’Aquila 2009 earthquake to the same period 1 year before, showing a 37% increase of new prescriptions for antidepressants and a 129% increase for antipsychotic prescriptions, with older age and female gender associated with the increased number of prescriptions.

Our results also suggest a significant association between some specific maladaptive behaviors, such as engagement in risk-taking behaviors and suicide attempts, and male gender in PTSD survivors. In this regard, in a sample of 409 Israeli adolescents exposed to recurrent terrorism, Pat-Horenczyk et al. (2007) reported significantly higher maladaptive behaviors, as a manifestation of functional impairment, in victims with PTSD, particularly among boys. Virtually all studies of the psychological effects of trauma indicate that women are more inclined to report anxiety and mood symptoms (Green, 2003; Shaw, 2003; Lai et al., 2004; Bal and Jensen, 2007; Cohen, 2008; Goenjian et al., 2009; Pratchett et al., 2010; Xu and Liao, 2011; Xu and Song, 2011; Zhang et al., 2011; Ali et al., 2012) and are at higher risk for developing post-traumatic distress than men (Davis and Siegel, 2000). However our data suggest that men tend to manifest more disruption in their behavioral adaption. Some authors in fact interpreted similar results in adolescents, suggesting that men tend to express psychological disturbances through acting out and external behavior, whereas women tend to express their distress by turning their feelings inwards, leading to depression and anxiety (Ostrov et al., 1989; Hirschberger et al., 2002; Pat-Horenczyk et al., 2007; Xu and He, 2012).

When looking at the possible associations between post-traumatic stress symptomatology and maladaptive behaviors significant correlations emerged in women, with each of the TALS-SR symptomatological domains, while the same was confirmed only for avoidance and numbing symptoms in men. Pat-Horenczyk et al. (2007) reported post-traumatic stress symptoms, including fear, re-experiencing, avoidance, and functional impairment, to be significant predictors of the severity of risk-taking behaviors beyond gender and level of exposure. Our results do not replicate these data as a significant association with post-traumatic stress symptoms emerged in women while in men this was confirmed for avoidance and numbing only.

Some important limitations of the study should be kept in mind before interpreting the results: first the limited number of subjects; second, the use of self-report instruments, instead of the rating of the clinician, in order to detect PTSD symptoms and even diagnosis. A self-report of PTSD symptoms may be, in fact, considered less accurate. The third limitation is the lack of information on the presence of Axis I psychiatric comorbidities and this may account for the answers on domain VII question regarding alcohol or drug abuse. Fourthly, in the present investigation we did not assess social support, though such support is generally believed to be high in Italy due to the closely knit family structure, and gender differences may also occur in this regard.

Despite these limitations, our results confirm the pervasive effects of a disaster, such as an earthquake, not only for mental health in the general population exposed, but also for the possible development of risk-taking behaviors that may affect men and women differently. In this regard, our results highlight the need to investigate such behaviors among earthquake exposed populations more in detail, with particular attention to gender differences, in order to get a more accurate understanding of post-traumatic stress psychopathology. Previous research (Armenian et al., 2000, 2002) has shown depression to be one of the major complications of earthquakes, possibly as a result of the multiple losses sustained. Given that women are vulnerable not only to PTSD, but also to anxiety disorders and major depression that can interfere and delay the recovery of the former, therapeutic intervention should be broadened beyond PTSD. Finally, the difference in maladaptive behaviors in men and women might be a correlate of the predominance of anxious-depressive symptomatology in women. In other words anxious depression might serve as a “break” on maladaptive behavior in women. These hypotheses deserve investigation in future analyses and studies.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Alhasnawi S., Sadik S., Rasheed M., Baban A., Al-Alak M. M., Othman A. Y., et al. (2009). Iraq mental health survey study group. The prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the Iraq mental health survey (IMHS). World Psychiatry 8, 97–109 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M., Farooq N., Bhatti M. A., Kuroiwa C. (2012). Assessment of prevalence and determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of earthquake in Pakistan using Davidson trauma scale. J. Affect. Disord. 136, 238–243 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenian H. K., Morikawa M., Melkonian A. K., Hovanesian A., Akiskal K., Akiskal H. S. (2002). Risk factors for depression in the survivors of the 1988 earthquake in Armenia. J. Urban Health 79, 373–382 10.1093/jurban/79.3.373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenian H. K., Morikawa M., Melkonian A. K., Hovanesian A. P., Haroutunian N., Saigh P. A., et al. (2000). Loss as a determinant of PTSD in a cohort of adult survivors of the 1988 earthquake in Armenia: implications for policy. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 102, 58–64 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102001058.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal A., Jensen B. (2007). Post-traumatic stress disorder symptom clusters in Turkish child and adolescent trauma survivors. Psychiatry 16, 449–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizzarri J. V., Rucci P., Sbrana A., Gonnelli C., Massei G. J., Ravani L., et al. (2007). Reasons for substance use and vulnerability factors in patients with substance use disorder and anxiety or mood disorders. Addict. Behav. 32, 384–391 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairo J. B., Dutta S., Nawaz H., Hashmi S., Kasl S., Bellido E. (2010). The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among adult earthquake survivors in Peru. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 4, 39–46 10.1001/dmp.2010.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassano G. B., Dell’Osso L., Frank E., Miniati M., Fagiolini A., Shear K., et al. (1999). The bipolar spectrum: A clinical reality in search of diagnostic criteria and an assessment methodology. J. Affect. Disord. 54, 319–328 10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00158-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda A., Valdez A., Kaplan C., Hill L. E. (2010). Patterns of substance use among hurricane Katrina evacuees in Houston, Texas. Disasters 34, 426–446 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01136.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdá M., Tracy M., Galea S. (2011). A prospective population based study of changes in alcohol use and binge drinking after a mass traumatic event. Drug Alcohol Depend. 115, 1–8 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. M., Connor K. M., Lai T. J., Lee R. (2005). Predictors of post-traumatic outcomes following the 1999 Taiwan earthquake. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 193, 40–46 10.1097/01.nmd.0000149217.67211.ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A. (2008). Helping adolescents affected by war, trauma, and displacement. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 47, 981–982 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31817eed8c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis L., Siegel L. J. (2000). Post traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: a review and analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 3, 135–154 10.1023/A:1009564724720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Osso L., Carmassi C., Conversano C., Massimetti G., Corsi M., Stratta P., et al. (2012). Post traumatic stress spectrum and maladaptive behaviour (drug abuse included) after catastrophic events: L’Aquila 2009 earthquake as case study. Heroin Addict. Relat. Clin. Probl. 14, 95–104 [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Osso L., Carmassi C., Massimetti G., Daneluzzo E., Di Tommaso S., Rossi A. (2011a). Full and partial PTSD among young adult survivors months after the L’Aquila 2009 earthquake: gender differences. J. Affect. Disord. 131, 79–83 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Osso L., Carmassi C., Massimetti G., Conversano C., Daneluzzo E., Riccardi I., et al. (2011b). Impact of traumatic loss on post-traumatic spectrum symptoms in high school students after the L’Aquila 2009 earthquake in Italy. J. Affect. Disord. 134, 59–64 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Osso L., Carmassi C., Rucci P., Conversano C., Shear M. K., Calugi S., et al. (2009). A multidimensional spectrum approach to post-traumatic stress disorder: comparison between the structured clinical interview for trauma and loss spectrum (SCI-TALS) and the self-report instrument (TALS-SR). Compr. Psychiatry 50, 485–490 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Osso L., Carmassi C., Stratta P., Rossi A. (2012). Maladaptive behaviors in L’Aquila earthquake survivors: the contribute of a “spectrum” approach to PTSD. Heroin Addict. Relat. Clin. Probl. 14, 49–56 [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Osso L., Da Pozzo E., Carmassi C., Trincavelli M. L., Ciapparelli A., Martini C. (2010). Lifetime manic-hypomanic symptoms in post-traumatic stress disorder: relationship with the 18 kDa mitochondrial translocator protein density. Psychiatry Res. 177, 139–143 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Osso L., Shear M. K., Carmassi C., Rucci P., Maser J. D., Frank E., et al. (2008). Validity and reliability of the structured clinical interview for the trauma and loss spectrum (SCI-TALS). Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 4, 2. 10.1186/1745-0179-4-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen E. B., Wagner H. R., Fuller S. R., Calhoun P. S., Kinner P. M., Beckham J. C. (2010). Correlates of anger and hostility in Iraq and Afghanistan was veterans. Am. J. Psychiatry 167, 1051–1058 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09050739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E., Cassano G. B., Shear M. K., Rotondo A., Dell’Osso L., Mauri M., et al. (1998). The spectrum model: a more coherent approach to the complexity of psychiatric symptomatology. CNS Spectr. 3, 23–34 [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M. J., Resick P. A., Bryant R. A., Strain J., Horowitz M., Spiegel D. (2011). Classification of trauma and stressor-related disorders in DSM-5. Depress. Anxiety 28, 737–749 10.1002/da.20893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glodich A., Allen J. G. (1998). Adolescents exposed to violence and abuse: a review of the group therapy literature with an emphasis on preventing trauma reenactment. J. Child Adolesc. Group Ther. 8, 135–154 10.1023/A:1022988218910 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goenjian A. K., Walling D., Steinberg A. M., Roussos A., Goenjian H. A., Pynoos R. S. (2009). Depression and PTSD symptoms among bereaved adolescents 6(1/2) years after the 1988 Spitak earthquake. J. Affect. Disord. 112, 81–84 10.1016/j.jad.2008.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore-Feltun C., Koopman C. (2002). Traumatic stress experience: harbinger of risk-behavior among HIV-positive adults. J. Trauma Dissociation 3, 121–135 10.1300/J229v03n04_07 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green B. (2003). Post-traumatic stress disorder: symptom profiles in men and women. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 19, 200–204 10.1185/030079902125001353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley S. L., Sikora D. M., McCoy R. (2008). Prevalence and risk factors of maladaptive behaviour in young children with autistic disorder. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 52, 819–829 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01065.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschberger G., Florian V., Mikulinser M., Goldenberg J. L., Pyszczynski T. (2002). Gender differences in the willingness to engage in risky behavior: a terror management perspective. Death Stud. 26, 117–141 10.1080/074811802753455244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain A., Weisaeth L., Heir T. (2011). Psychiatric disorders and functional impairment among disaster victims after exposure to a natural disaster: a population based study. J. Affect. Disord. 128, 135–141 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin C. E. (1990). The theoretical concept of at-risk adolescents. Adolesc. Med. State Art Rev. 1, 1–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahangiri K., Izadkhah Y. O., Montazeri A., Hosseinip M. (2010). People’s perspectives and expectations on preparedness against earthquakes: Tehran case study. J. Inj. Violence Res. 2, 85–91 10.5249/jivr.v2i2.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M., Conybeare D., Phelps L., Hunt S., Holmes H. A., Felker B., et al. (2007). Anger, hostility, and aggression among Iraq and Afganistan war veterans reporting PTSD and subthreshold PTSD. J. Trauma Stress 20, 945–954 10.1002/jts.20258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessup M. A., Dibble S. L., Cooper B. A. (2012). Smoking and behavioral health of women. J. Womens Health (Larchmt.) 21, 783–791 10.1089/jwh.2011.2886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C. (2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder: the burden to the individual and to society. J. Clin. Psychiatry 61, 4–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krysinska K., Lester D. (2010). Post-traumatic stress disorder and suicide risk: a systematic review. Arch. Suicide Res. 14, 1–23 10.1080/13811110903478997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn E., Drescher K., Ruzek J., Rosen C. (2010). Aggressive and unsafe driving in male veterans receiving residential treatment for PTSD. J. Trauma Stress 23, 399–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai T. J., Chang C. M., Connor K. M., Lee L. C., Davidson J. R. (2004). Full and partial PTSD among earthquake survivors in rural Taiwan. J. Psychiatr. Res. 38, 313–322 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2003.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberzon I., Sripada C. S. (2008). The functional neuroanatomy of PTSD: a critical review. Prog. Brain Res. 167, 151–169 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)67011-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maj M., Starace F., Crepet P., Lobrace S., Veltro F., De Marco F., et al. (1989). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among subjects exposed to a natural disaster. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 79, 544–549 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb10301.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maremmani A. G., Rovai L., Rugani F., Pacini M., Lamanna F., Bacciardi S., et al. (2012). Correlations between awareness of illness (insight) and history of addiction in heroin-addicted patients. Front. Psychiatry 3:61. 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane A. C. (2010). The long-term costs of traumatic stress: intertwined physical and psychological consequences. World Psychiatry 9, 3–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen J. C., North C. S., Smith E. M. (2000). What parts of PTSD are normal: intrusion, avoidance, or arousal? Data from the Northridge, California, earthquake. J. Trauma Stress 13, 57–75 10.1023/A:1007768830246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrov E., Offer D., Howard K. I. (1989). Gender differences in adolescent symptomatology: a normative study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 28, 394–398 10.1097/00004583-198905000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pat-Horenczyk R., Peled O., Miron T., Brom D., Villa Y., Chemtob C. M. (2007). Risk taking behaviors among Israeli adolescents exposed to recurrent terrorism: provoking danger under continuous threat? Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 66–72 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.1.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak R. H., Goldstein R. B., Southwick S. M., Grant B. F. (2012). Psychiatric comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder among older adults in the United States: results from wave 2 of the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 20, 380–390 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182107e24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollice R., Bianchini V., Roncone R., Casacchia M. (2011). Marked increase in substance use among young people after L’Aquila earthquake. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 20, 429–430 10.1007/s00787-011-0192-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratchett L. C., Pelcovitz M. R., Yehuda R. (2010). Trauma, and violence: are women the weaker sex? Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 33, 465–474 10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinak C. A., Angstadt M., Welsh R. C., Kenndy A. E., Lyubkin M., Martis B., et al. (2011). Altered amygdala resting-state functional connectivity in post-traumatic stress disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2:62. 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi A., Maggio R., Riccardi I., Allegrini F., Stratta P. (2011). A quantitative analysis of antidepressant and antipsychotic prescriptions following an earthquake in Italy. J. Trauma Stress 24, 129–132 10.1002/jts.20607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbrana A., Bizzarri J. V., Rucci P., Gonnelli C., Doria M. R., Spagnolli S., et al. (2005). The spectrum of substance use in mood and anxiety disorders. Compr. Psychiatry 46, 6–13 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J. A. (2003). Children exposed to war/terrorism. Clin. Child Fam. Psychiatry Rev. 6, 237–246 10.1023/B:CCFP.0000006291.10180.bd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherin J. E., Nemeroff C. B. (2011). Post-traumatic stress disorder: the neurobiological impact of psychological trauma. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 13, 263–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S., Aso K., Noda T., Ryukei S., Kochi Y., Yamamoto N. (2000). Natural disasters and alcohol consumption in a cultural context: the Great Hanshin earthquake in Japan. Addiction 95, 529–536 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9545295.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steven S. J., Murphy B. S., McKnight K. (2003). Traumatic stress and gender differences in relationship to substance abuse, mental health, physical health and HIV risk-taking in a sample of adolescents enrolled in drug treatment. Child Maltreat 8, 46–57 10.1177/1077559502239611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratta P., Capanna C., Riccardi I., Carmassi C., Piccinni A., Dell’Osso L., et al. (2012). Suicidal intention and negative spiritual coping one year after the earthquake of L’Aquila (Italy). J. Affect. Disord. 136, 1227–1231 10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugar M. (1999). “Severe physical trauma in adolescence,” in Trauma and Adolescence, eds Madison S. M. (Conn: International Universities Press; ), 183–201 [Google Scholar]

- Vehid H. E., Alyanak B., Eksi A. (2006). Suicide ideation after the earthquake in Marmara, Turkey. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 208, 19–24 10.1620/tjem.208.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D., Galea S., Resnick H., Ahern J., Boscarino J. A., Bucuvalas M., et al. (2002). Increased use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana among Manhattan, New York, residents after the September 11th terroristic attacks. Am. J. Epidemiol. 155, 988–996 10.1093/aje/155.11.988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., He Y. (2012). Psychological health and coping strategy among survivors in the year following the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 66, 210–219 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2012.02331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Liao Q. (2011). Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic growth among adult survivors one year following 2008 Sichuan earthquake. J. Affect. Disord. 133, 274–280 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Song X. (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder among survivors of the Wenchuan earthquake 1 year after: prevalence and risk factors. Compr. Psychiatry 52, 431–437 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Shi Z., Wang L., Liu M. (2011). One year later: Mental health problems among survivors in hard-hit areas of the Wenchuan earthquake. Public Health 125, 293–300 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]