Abstract

The persistence of minimal residual disease (MRD) during therapy is the strongest adverse prognostic factor in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). We developed a high-throughput sequencing method that universally amplifies antigen-receptor gene segments and identifies all clonal gene rearrangements (ie, leukemia-specific sequences) at diagnosis, allowing monitoring of disease progression and clonal evolution during therapy. In the present study, the assay specifically detected 1 leukemic cell among greater than 1 million leukocytes in spike-in experiments. We compared this method with the gold-standard MRD assays multiparameter flow cytometry and allele-specific oligonucleotide polymerase chain reaction (ASO-PCR) using diagnostic and follow-up samples from 106 patients with ALL. Sequencing detected MRD in all 28 samples shown to be positive by flow cytometry and in 35 of the 36 shown to be positive by ASO-PCR and revealed MRD in 10 and 3 additional samples that were negative by flow cytometry and ASO-PCR, respectively. We conclude that this new method allows monitoring of treatment response in ALL and other lymphoid malignancies with great sensitivity and precision. The www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier number for the Total XV study is NCT00137111.

Introduction

The clinical management of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) relies on accurate prediction of relapse hazard to determine the intensity of therapy and to avoid over- or undertreatment.1,2 Traditional prognostic factors include presenting clinical and biologic features such as age, blast count at diagnosis, immunophenotype, and genetic abnormalities.1,2 Based on a large body of evidence involving thousands of patients, the measurement of residual leukemia levels, “minimal residual disease” (MRD), during therapy has now emerged as the most important predictor of outcome in ALL.3,4 As a result, risk-classifications based on MRD assessment are now a critical component of ALL clinical treatment protocols.

Current methodologies to monitor MRD in ALL include flow cytometric detection of aberrant immunophenotypes, which can detect 1 leukemic cell among 10 000 (0.01%) normal cells, and allele-specific oligonucleotide PCR (ASO-PCR) amplification of immunoglobulin (Ig) and T-cell receptor (TCR) genes, which has a sensitivity of 0.001%.3–5 Although these methods have proven to be reliable in a clinical setting, they have limitations. Flow cytometry requires a high level of expertise to interpret results proficiently. ASO-PCR requires the development of reagents and assay conditions for each individual patient, which is laborious and time-consuming. Moreover, these methods have limited or no capacity to monitor the evolution of different leukemic subclones during treatment, with the potential of false-negative results. Finally, patients who achieve MRD− status by standard criteria but have very low levels of persistent leukemia have a higher risk of relapse than those with no detectable MRD,6 suggesting that improvements in sensitivity of MRD monitoring methods might improve precision in predicting relapse.

We developed a novel, sequencing-based method to identify cells with specific molecular signatures. The method employs consensus primers to universally amplify rearranged Ig and TCR gene segments in a sample and relies on high-throughput sequencing and specifically designed algorithms to identify clonal gene rearrangements in diagnostic samples and quantify these rearrangements in follow-up MRD samples. In the present study, we assessed the suitability of this method to monitor MRD in ALL. We determined its sensitivity and specificity, delineated the extent of genetic diversity (including clonal evolution) present at diagnosis, and compared its capacity to measure MRD with that of flow cytometry and ASO-PCR in follow-up samples from more than 100 patients with ALL.

Methods

Clinical samples

BM samples were collected at diagnosis and during treatment from 110 children with newly diagnosed B-lineage ALL, representing 22.1% of the 498 patients enrolled in the Total XV study at St Jude Children's Research Hospital.7 The sample selection for this study was based on the demonstrated presence of an immunoglobulin heavy chain locus (IGH@, IgH) clonal rearrangement at diagnosis, ASO-PCR MRD data in a follow-up sample, and abundant surplus DNA available. This study was conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki principles, was approved by the St Jude Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of each child (and assent from the patients as appropriate).

MRD measurements by ASO-PCR and flow cytometry

ASO-PCR MRD studies were performed as described previously, with MRD quantification performed by limiting-dilution (n = 34) or real-time PCR (n = 76). Briefly, we made 10-fold serial dilutions of diagnostic DNA in pooled peripheral blood DNA extracted from mononuclear cells of 4-6 healthy donors and analyzed each dilution in duplicate (in quadruplicate for the single-copy dilution). For the limiting dilution method, we used either a 2-round (semi-nested or with the same patient-specific and consensus primer in both rounds) or a 1-round PCR assay with an initial touchdown phase and quantitated MRD using Poisson statistics. Real-time PCR analysis was performed by a single PCR amplification with sequence-specific TaqMan hydrolysis probes on an ABI PRISM Sequence Detection System 7700 (Applied Biosystems).6 MRD studies by flow cytometry were performed using a combination of markers identified at diagnosis, as described previously.8

MRD measurements with the Sequenta LymphoSIGHT method

Genomic DNA, isolated using AllPrep DNA mini and/or micro kits (QIAGEN), was amplified using locus-specific primer sets for IgH@ complete (VHDJH), IgH@ incomplete (DJH), and TCRs including TRB@, TRD@, and TRG@, which were designed to allow for the amplification of all known alleles of the germline IgH and TCR sequences (for a description of the primer design and amplification and sequencing reactions, see supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).9 A clonotype was defined when at least 2 identical sequencing reads were obtained (see supplemental Methods).

The frequency of each clonotype in a sample was determined by calculating the number of sequencing reads for each clonotype divided by the total number of passed sequencing reads in the sample. To define leukemic gene rearrangements in samples obtained at diagnosis, we used a frequency threshold of 5% (ie, any clonotype present at a frequency of > 5% was regarded as originating from the leukemic clone). In preliminary studies, the frequency of individual clonotypes among normal B-cell populations was consistently below this threshold.

We used the following criteria to identify any clonotypes present in the same diagnostic sample that might have evolved from the leukemic clone through VH replacement: (1) identical J and D segments, (2) identical J segment deletion size, (3) identical D segment deletion size (the side next to the J segment), (4) random N base insertions between the J and D segments, and (5) different V segments.

The leukemia-derived sequences identified at diagnosis were used as a target to assess the presence of MRD in follow-up samples. For MRD quantitation, we generated multiple sequencing reads for each rearranged B cell in the reaction. For example, in cells containing an IgH rearrangement (ie, B cells), the MRD assay was designed to achieve approximately 10× coverage per B cell.

To determine the absolute measure of the total leukemia-derived molecules present in the follow-up sample, we added a known quantity of reference IgH sequence into the reaction and counted the associated sequencing reads. The known quantity of reference IgH sequence was derived from a pool of plasmids containing 3 unique IgH clonotypes quantitated using standard RT-PCR methods. The resulting factor (ie, the number of molecules per sequence read) was then applied to the leukemia-associated clonal rearrangement reads to obtain an absolute measure of the total leukemia-derived molecules in the reaction. A similar calculation can be performed to assess the total number of rearranged IgH molecules or B-lineage cells in the reaction. Finally, we calculated the total leukocytes in the reaction by measuring the total DNA using standard PicoGreen methods and RT-PCR using genomic markers such as β-actin DNA.

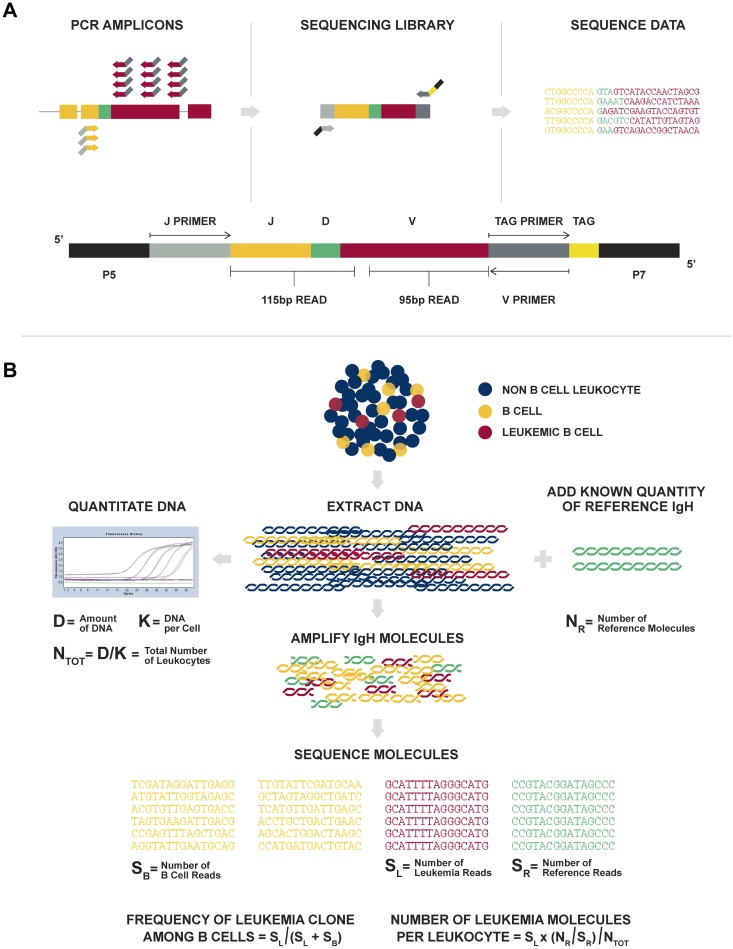

These metrics were combined to calculate a final MRD measurement, which is the number of leukemia-derived molecules divided by the total leukocytes in the sample. In cases in which there were are multiple index clones, we used the highest frequency index clone to calculate the percentage of MRD in follow-up samples. This quantitation scheme is illustrated schematically in Figure 1B.

Figure 1.

Overview of the LymphoSIGHT method. (A) Schematic of the PCR primer strategy and sequencing assay. (B) Schematic of the MRD quantitation scheme.

Assessment of Sequenta LymphoSIGHT platform technical performance

Diagnostic samples from 12 ALL patients were used for technical assessment of the LymphoSIGHT platform. The selected samples had a > 95% clonal rearrangement frequency among B-lineage cells. In addition, the samples were almost exclusively composed of leukemic B-lineage cells based on equivalence between the total number of rearranged IgH molecules and leukocytes in each sample.

Serial dilutions of the 12 selected samples were prepared in duplicate in normal PBMCs at a range between 1 in 1 million and 1 in 1000 cells. Dilutions were then subjected to amplification and sequencing in 2 replicate experiments. Correction factors for sample purity and dilution preparations were applied and RT-PCR based measurements of the sample concentration were used for increased accuracy. We compared expected and measured frequencies in log space. For correlation and slope, the lowest dilution was excluded because some values were 0.

Results

Sensitivity, precision, and quantitative capacity of the immune repertoire sequencing assay

Figure 1 provides an overview of the Sequenta LymphoSIGHT method. Using universal primer sets, we first amplified IgH@ and TCR sequences from genomic DNA in a 2-stage PCR. The amplified product was sequenced to obtain a high number of reads (eg, 106 reads; Figure 1A). Typically, the number of reads exceeded the number of starting molecules, allowing every starting molecule to be sampled. The sequence reads were analyzed to determine similar sequences that form a clonotype. After clonotype determination, a standard quantitation scheme was used to calculate MRD metrics (Figure 1B, “Methods”), including clonotype frequency, number of leukemia-associated molecules in the reaction, number of total leukocytes in the reaction, and MRD level.

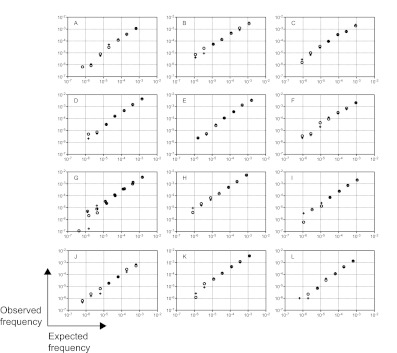

We assessed the technical performance of the method using diagnostic samples from 12 of the 110 ALL patients included in the study who carried 13 leukemic IgH clonotypes. Serial dilutions of leukemic cells in normal PBMCs, ranging from < 1 in 1 million to > 1 in 1000 cells, were prepared and analyzed in duplicate. The high precision of the assay was demonstrated by the low average relative SDs (range, 4.1%-7.6%) at clonotype frequencies at or above 3 × 10−5 (supplemental Table 1). Therefore, the assay is highly quantitative for frequencies above 10−5. Random error increased at clonotype frequencies below 10−5, as expected from Poisson statistics with low number of input molecules in the reaction (supplemental Table 1). For each clonotype, the assay showed high r2 values with a range of 0.977 to 0.996 (mean 0.988 and median 0.991) between each of the expected and the measured clonotype frequencies (Figure 2 and supplemental Table 2). The slopes ranged from 0.878 to 1.14 (mean 1.00 and median 0.977), illustrating the quantitative nature of the assay over at least 3 orders of magnitude.

Figure 2.

Technical performance of immune repertoire sequencing assay. Diagnostic samples from 12 ALL patients containing 13 leukemic IgH clonotypes were used for technical performance studies. Serial dilutions of leukemic cells in normal PBMCs, ranging from < 1 in 1 million to > 1 in 1000 tumor cells, were prepared and analyzed in duplicate. The 7 duplicated dilutions were then subjected to amplification and sequencing in 2 replicate experiments. The expected and observed frequencies were compared on a logarithmic scale. Replicate 1 is represented by circles and replicate 2 is represented by crosses in all panels. Panel G shows the results from 2 cancer clones that were present in this tumor.

The immune repertoire sequencing assay unequivocally detected leukemic signatures in all dilutions with expected concentration of at least 1 leukemic cell in 1 million leukocytes (a sensitivity of 10−6; Figure 2). We also tested the sensitivity of the assay to detect levels of leukemic cells below 1 in 1 million leukocytes (Figure 2). We detected an average expected concentration of 7.4 × 10−7 and expected number of molecules of 5. We did not detect leukemia signals in 2 cases with low expected concentrations (4.2 × 10−7 and 6.7 × 10−7 with 2 and 4 expected molecules, respectively), a result that was likely caused by insufficient leukemia-derived molecules in the reaction and is consistent with Poisson sampling.

Analysis of all clonotypes together reflects multiple sources of error, including error associated with quantitation of the original leukemic DNA, pipetting error in the dilution preparations, error in measurement of the original sample purity (ie, samples may not have been composed of 100% leukemic B cells), and random and systematic error associated with the assay. Despite these potential sources of error, we measured an r2 value of 0.94 and a slope of 1.01 between the expected and measured clonotype frequencies. Therefore, the cell dilution experiments clearly demonstrated the immune repertoire sequencing assay to be precise and quantitative with sensitivity levels at or below 1 leukemic cell per 1 million leukocytes.

Detection of clonal rearrangements of multiple receptor genes in diagnostic samples

We used the sequencing assay to detect rearrangements of immune cell receptor genes, IgH@ complete (VHDJH), IgH@ incomplete (DJH), TRB@, TRD@, and TRG@, in diagnostic BM samples from 100 of the 110 ALL patients known to have IgH rearrangements. An additional 10 samples were only assayed for IgH VHDJH and were not included in this clonal gene rearrangement analysis. As expected, all 100 diagnostic samples demonstrated a high-frequency clonal rearrangement for at least one receptor, herein referred to as a “calibrating receptor.” The majority (n = 94) had at least 2 calibrating receptors, with 51 having 3 or more.

The IgH complete VHDJH assay was the most frequent gene rearrangement: at least one IgH VHDJH clonal rearrangement was detected in 96 of the diagnostic ALL samples (Table 1). TRD@ was the second most informative receptor, and at least one TRD@ clonal rearrangement was detected in 63 of the samples (Table 1). In contrast, TRB@ clonal rearrangements were only identified in 16 samples (Table 1). Concomitant clonal rearrangements of IgH (mature and/or immature) and at least 1 TCR gene were found in 86 of 100 samples collected at diagnosis.

Table 1.

No. of patients by no. of calibrating clones in each receptor

| Receptor | No. of index clones |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 11 | |

| IGH@-VDJ | 4 | 51 | 35 | 9 | 1 | |||||

| IGH@-DJ | 67 | 22 | 9 | 2 | ||||||

| TRB@ | 84 | 13 | 3 | |||||||

| TRD@ | 37 | 41 | 13 | 9 | ||||||

| TRG@ | 47 | 29 | 24 | |||||||

| All receptors | 0 | 2 | 18 | 29 | 21 | 16 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

We also assessed the cumulative number of clonal gene rearrangements that were present in each sample, because more than one clonal rearrangement could be detected with one receptor. Among the 100 diagnostic samples studied, 98, 80, and 51 had 2 or more, 3 or more, and 4 or more clonal rearrangements across all receptors, respectively (Table 1).

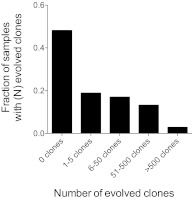

One advantage of our method is that all rearranged genes are captured, enabling the comprehensive delineation of the landscape of IgH genetic diversity and clonal selection that occurred during the leukemogenic process.10 We analyzed 106 of the 110 diagnostic ALL samples with complete IgH VHDJH gene rearrangements for evidence of IgH clonal evolution because of ongoing secondary recombination events during disease progression. The evolved clonotypes were identified by virtue of their sequence relatedness to the high-frequency clonal rearrangement. The number of evolved clones per ALL sample varied widely from 0-6933 clonotypes. Fifty-six of 106 samples (53%) demonstrated VHDJH to VHDJH evolution, which is consistent with a VH replacement model.11–16 These samples could be categorized into 5 groups based on the number of evolved clones present, with 39 patients (37%) having 1-50 evolved clones and 17 patients (16%) having a high degree of evolution (> 50 evolved clones; Figure 3). These data show that the sequencing assay captured the extensive evolution that is present in diagnostic samples, a potential cause of false-negative results during MRD monitoring by ASO-PCR focusing on selected gene rearrangements.

Figure 3.

Clonal evolution mechanisms at the IgH gene locus. Diagnostic samples containing a clonal gene rearrangement, as determined using the VDJ (n = 106) assay were categorized into 5 groups based on the number of evolved clones present in the diagnostic sample. The fraction of all samples having a given number of evolved clones is shown.

Comparison of MRD results by immune repertoire sequencing with those by standard MRD assays

We assessed MRD using the sequencing assay in follow-up samples collected during therapy from 106 patients with newly diagnosed B-lineage ALL and IgH VHDJH clonal gene rearrangements at diagnosis. In addition to the previously demonstrated presence of IgH gene rearrangements at diagnosis, the main criteria for inclusion in the study was the availability of abundant surplus DNA collected during follow-up. In the Total XV trial, MRD was measured by flow cytometry and ASO-PCR during and at the end of remission induction therapy (on days 19, 26, and 46), during continuation therapy (at weeks 7, 17 and 48), and at the end of therapy (at week 120 for girls and week 146 for boys).7 Of the 106 samples studied, 45 were collected during induction therapy (n = 18) or at the end of remission induction therapy (n = 27), 44 during continuation therapy, and 17 at the end of therapy (supplemental Table 3), thus providing a full representation of the different types of BM cellularity found during ALL treatment.

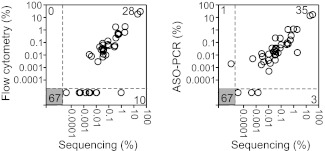

We first analyzed concordance between MRD results obtained by our assay and flow cytometry, which was used to monitor MRD in 105 of the 106 cases. The sequencing test was performed without knowledge of the results of flow cytometry testing. The 2 methods gave concordant MRD+ or MRD− results in 95 of 105 (90%) samples (Figure 4A and supplemental Table 3). In 10 of 105 samples (10%), MRD was positive by sequencing, but undetectable by flow cytometry (Figure 4A and Table 2); 7 of these 10 samples were also positive by ASO-PCR. Most of the discordance between the sequencing assay and flow cytometry can be explained by the sensitivity limitations of flow cytometry. For example, MRD levels ranged between 0.00004% and 0.011% by sequencing in 9 of the 10 discordant samples (Table 2). MRD was undetectable by flow cytometry and measured at 0.96% and 1.2% by sequencing and ASO-PCR, respectively, in the final discordant sample (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Comparison of MRD results obtained by sequencing, flow cytometry, and ASO-PCR. MRD results obtained using the sequencing method were compared with flow cytometry results for 105 ALL patients (left) and with ASO-PCR results for 106 ALL patients (right). In each panel, the numbers of concordant measurements are shown in the lower left and upper right and the number of discordant measurements are shown in the upper left and lower right.

Table 2.

Summary of discordant MRD results for the sequencing, flow cytometry, and ASO-PCR methods

| Patient ID | Input cells, n | % MRD |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing | Flow cytometry | PCR | ||

| 9 | 248 496 | 0.00004 | UD | UD |

| 12 | 133 669 | 0.0027 | UD | 0.0017 |

| 25 | 142 310 | 0.0106 | UD | 0.0005 |

| 30 | 120 307 | 0.0032 | UD | 0.0076 |

| 31 | 1 109 253 | 0.0014 | UD | UD |

| 41 | 626 380 | 0.0005 | UD | 0.0051 |

| 58 | 171 326 | 0.0102 | UD | 0.0120 |

| 73 | 983 289 | 0.0004 | UD | UD |

| 98 | 162 217 | 0.0097 | UD | 0.0038 |

| 29 | 161 142 | 0.9607 | UD | 1.2000 |

| 36 | 1 070 242 | UD | UD | 0.0020 |

UD indicates undetectable.

We next compared the MRD results obtained by immune repertoire sequencing and ASO-PCR. Again, the sequencing test was performed without knowledge of the previously collected results by ASO-PCR. Results were concordant in 102 of 106 follow-up samples (96%): 35 (33%) were MRD+ and 67 (63%) were MRD− by both methods (Figure 4B and supplemental Table 3). In 3 of 106 samples, MRD was positive by sequencing (0.0014%, 0.0004%, and 0.00004%), but undetectable by ASO-PCR (Figure 4B and Table 2), a result that could be explained by the fact that these levels of MRD would be outside of the quantitative range of ASO-PCR.5 In the remaining sample, a faint signal corresponding to 0.0020% MRD was detected by ASO-PCR (performed by a limiting-dilution assay), but MRD was undetectable by sequencing (Figure 4B and Table 2). The reason for this discrepancy is unclear. The DNA analyzed by the sequencing test in this sample corresponded to 1.07 million input cells. Therefore, if the ASO-PCR estimate was correct, DNA from approximately 20 ALL cells should have been present in the sample and this number of clonal rearrangements should have been easily detectable by the sequencing assay. However, MRD estimates by ASO-PCR can be inaccurate at such extremely low levels, and it is possible that the sample analyzed by sequencing did not contain any leukemic DNA at all. Alternatively, the ASO-PCR signal may have been an artifact. This discrepancy notwithstanding, these comparisons with the gold standard MRD assays provide strong evidence of the reliability and sensitivity of the sequencing assay when applied to clinical samples collected from patients undergoing chemotherapy.

When present in the detection range, MRD levels measured by flow cytometry are typically accurate, because this method directly counts leukemic cells among normal cells.4,17 In the 29 samples with detectable MRD in all 3 platforms, MRD levels measured by the sequencing assay were highly correlated with those of flow cytometry. Specifically, the MRD level measured by the 2 platforms showed an r2 of 0.83 and a slope of 1.03, supporting the quantitative accuracy of the sequencing assay. ASO-PCR versus flow cytometry MRD results showed an r2 of 0.75 and a slope of 1.04.

We tested the concordance between MRD results using the IgH VHDJH sequencing assay and other receptor rearrangement sequencing assays (ie, IgH DJH and TCR assays) in a subset of 9 samples that had previously been identified as having non-IgH recombinations. In all cases, results were concordant with the previously observed data. Specifically, 7 samples were MRD− according to both the IgH VHDJH and a second receptor, and 2 samples were MRD+ according to the IgH VHDJH and a second receptor (supplemental Table 4).

Discussion

We developed a novel approach to monitoring response to treatment in patients with leukemia. The method employs consensus primers and high-throughput sequencing to universally amplify and sequence all rearranged IgH and TCR gene segments present in a leukemic clone. It also allows the identification of all clonal gene rearrangements in diagnostic samples and enables tracking of their evolution during therapy. A previous study demonstrated the utility of high-throughput sequencing for MRD quantitation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia.18 In addition, while this manuscript was in preparation, Wu et al reported the use of high-throughput sequencing to detect MRD in patients with T-lineage ALL; their results compared favorably with those of flow cytometry, but no comparison was made with ASO-PCR.19 In the present study, we have shown that the sequencing assay is precise, quantitative, and sensitive when applied to BM samples collected throughout treatment in patients with B-lineage ALL. Our method is quantitative at frequencies above 10−5 and the lower limit of detection is below 10−6. Moreover, the technical performance data presented herein demonstrate that the sequencing assay sensitivity is limited only by the number of input cells and thus can detect residual disease at levels well below 1 in 1 million leukocytes (0.0001%). This represents at least 1-2 orders of magnitude higher sensitivity than standard ASO-PCR and flow-cytometric methods, respectively.

Comparisons with gold standard MRD assays provide strong evidence of the reliability and sensitivity of the sequencing assay when applied to clinical samples collected from patients undergoing chemotherapy. Our assay offers potential advantages over ASO-PCR, the standard method to target IgH and TCR genes for MRD studies. First, it allows monitoring of all leukemic rearrangements regardless of their prevalence at diagnosis. This feature should abrogate the risk of false-negative MRD results due to clonal evolution during the course of the disease, in which subclones representing a minority of antigen-receptor gene rearrangements might be neglected at diagnosis but become predominant at relapse.14,20–25 We observed that the majority of samples studied at diagnosis already had a high degree of genetic diversity at the IgH locus, which is in agreement with the results of another study focusing on the immune repertoire sequencing method to determine the prevalence of clonal evolution in diagnostic samples from patients with B-lineage ALL.26 Second, current ASO-PCR assays require the development of customized primer sets and assay conditions for the detection of each individual clonal gene rearrangement in each patient, a laborious and time-consuming process that becomes increasingly so if multiple receptors and/or clonal rearrangements are assayed. Because the sequencing assay uses a set of universal primers, it can assess multiple clonal rearrangements in every patient without the need for individualized procedures. We currently estimate that the assay will have a turnaround time of approximately 7 days for MRD detection. A schematic diagram of the analysis and workflow of our method when performed prospectively is shown in Figure 5. Finally, there is evidence suggesting that MRD positivity below 0.01% has prognostic implications,6 although it remains to be determined whether the enhanced sensitivity of the immune repertoire sequencing approach will provide additional clinical information in the context of current chemotherapy and allogeneic stem cell transplantation protocols for ALL. Conceivably, a high sensitivity of MRD detection before transplantation could be useful in improving the timing of the procedure27; after transplantation, it should allow for early intervention to avoid relapse.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of sequencing analysis and work flow for prospective sample collection.

Our approach relies on high-throughput sequencing to identify leukemia-associated gene rearrangements at diagnosis and to measure their prevalence during treatment. Although the costs of the sequencing process were historically prohibitive for routine application, they have been steadily decreasing by a factor of approximately 20 000 over the past decade. The current sequencing costs for rearranged antigen-receptor genes are comparable to those of flow cytometry and ASO-PCR and are predicted to decrease substantially with further advances in sequencing technology. High-throughput sequencing data may be complex to interpret, but, as shown by our results, the analytic algorithms that we designed allow unequivocal detection and accurate quantitation of leukemia-derived sequences. The prognostic power of MRD during treatment has been amply demonstrated in numerous correlative studies performed in patients with newly diagnosed childhood and adult ALL6,7,17,28–37 or relapsed ALL,38–40 and in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.27,41 Monitoring of MRD has become a central component of the modern management of patients with ALL7 and is beginning to be introduced as a criterion for testing novel antileukemic agents.42 The sensitivity, universal applicability, and capacity to capture clonal evolution of the method described herein, together with the results of our comparison with standard MRD assays in clinical samples, strongly support its potential as a next-generation MRD test for ALL. Although we limited our study to the most common form of ALL, B-lineage, the same approach could also be applied to T-lineage ALL or other lymphoid malignancies such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and multiple myeloma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants CA60419 and CA21765 from the National Cancer Institute, by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities, and by research funding from Sequenta Inc. (to M.F., J.Z., M.M., and V.E.H.C.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: M.F., J.Z., M.M., and V.E.H.C. performed the sequencing assays and analyzed and interpreted the data; P.S. and E.C.-S. provided the ASO-PCR and flow cytometry MRD data; C.-H.P. led the clinical trial under which the samples were collected for MRD studies; M.F. and D.C. designed the research, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; and all authors provided input on and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.F., J.Z., M.M., and V.E.H.C. are employees of and stockholders in Sequenta Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Malek Faham, MD, PhD, 400 E Jamie Ct, Ste 301, South San Francisco, CA 94080; e-mail: malek.faham@sequentainc.com.

References

- 1.Gökbuget N, Hoelzer D. Treatment of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2009;46(1):64–75. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pui CH, Carroll WL, Meshinchi S, Arceci RJ. Biology, risk stratification, and therapy of pediatric acute leukemias: an update. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(5):551–565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brüggemann M, Schrauder A, Raff T, et al. Standardized MRD quantification in European ALL trials: proceedings of the Second International Symposium on MRD assessment in Kiel, Germany, 18-20 September 2008. Leukemia. 2010;24(3):521–535. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campana D. Minimal residual disease in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:7–12. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Velden VH, Cazzaniga G, Schrauder A, et al. Analysis of minimal residual disease by Ig/TCR gene rearrangements: guidelines for interpretation of real-time quantitative PCR data. Leukemia. 2007;21(4):604–611. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stow P, Key L, Chen X, et al. Clinical significance of low levels of minimal residual disease at the end of remission induction therapy in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(23):4657–4663. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pui CH, Campana D, Pei D, et al. Treating childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2730–2741. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coustan-Smith E, Song G, Clark C, et al. New markers for minimal residual disease detection in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2011;117(23):6267–6276. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-324004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faham M, Willis T. Monitoring health and disease status using clonotype profiles. US patent application 2011/0207134A1. 2011 Aug 25; [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greaves M, Maley CC. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature. 2012;481(7381):306–313. doi: 10.1038/nature10762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenquist R, Thunberg U, Li AH, et al. Clonal evolution as judged by immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangements in relapsing precursor-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Eur J Haematol. 1999;63(3):171–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1999.tb01765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitchingman GR. Immunoglobulin heavy chain gene VH-D junctional diversity at diagnosis in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1993;81(3):775–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steenbergen EJ, Verhagen OJ, van Leeuwen EF, von dem Borne AE, van der Schoot CE. Distinct ongoing Ig heavy chain rearrangement processes in childhood B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1993;82(2):581–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi Y, Greenberg SJ, Du TL, et al. Clonal evolution in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia by contemporaneous VH-VH gene replacements and VH-DJH gene rearrangements. Blood. 1996;87(6):2506–2512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Z, Burrows PD, Cooper MD. The molecular basis and biological significance of VH replacement. Immunol Rev. 2004;197:231–242. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koralov SB, Novobrantseva TI, Konigsmann J, Ehlich A, Rajewsky K. Antibody repertoires generated by VH replacement and direct VH to JH joining. Immunity. 2006;25(1):43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coustan-Smith E, Behm FG, Sanchez J, et al. Immunological detection of minimal residual disease in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 1998;351(9102):550–554. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Logan AC, Gao H, Wang C, et al. High-throughput VDJ sequencing for quantification of minimal residual disease in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and immune reconstitution assessment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(52):21194–21199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118357109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu D, Sherwood A, Fromm JR, et al. High-throughput sequencing detects minimal residual disease in acute T lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(134):134ra63. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szczepański T, Willemse MJ, Brinkhof B, van Wering ER, van der Burg M, van Dongen JJ. Comparative analysis of Ig and TCR gene rearrangements at diagnosis and at relapse of childhood precursor-B-ALL provides improved strategies for selection of stable PCR targets for monitoring of minimal residual disease. Blood. 2002;99(7):2315–2323. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li A, Zhou J, Zuckerman D, et al. Sequence analysis of clonal immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene rearrangements in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia at diagnosis and at relapse: implications for pathogenesis and for the clinical utility of PCR-based methods of minimal residual disease detection. Blood. 2003;102(13):4520–4526. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Haas V, Verhagen OJ, von dem Borne AE, Kroes W, van den Berg H, van der Schoot CE. Quantification of minimal residual disease in children with oligoclonal B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia indicates that the clones that grow out during relapse already have the slowest rate of reduction during induction therapy. Leukemia. 2001;15(1):134–140. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi S, Henderson MJ, Kwan E, et al. Relapse in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia involving selection of a preexisting drug-resistant subclone. Blood. 2007;110(2):632–639. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-067785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konrad M, Metzler M, Panzer S, et al. Late relapses evolve from slow-responding subclones in t(12;21)-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: evidence for the persistence of a preleukemic clone. Blood. 2003;101(9):3635–3640. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson MJ, Choi S, Beesley AH, et al. Mechanism of relapse in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(10):1315–1320. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.10.5885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gawad C, Pepin F, Carlton V, et al. Massive evolution of the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus in children with pediatric B precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia [published online ahead of print August 28, 2012]. Blood. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-429811. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-429811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leung W, Campana D, Yang J, et al. High success rate of hematopoietic cell transplantation regardless of donor source in children with very high-risk leukemia. Blood. 2011;118(2):223–230. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-333070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cavé H, van der Werff ten Bosch J, Suciu S, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer–Childhood Leukemia Cooperative Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(9):591–598. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808273390904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Dongen JJ, Seriu T, Panzer-Grumayer ER, et al. Prognostic value of minimal residual disease in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in childhood. Lancet. 1998;352(9142):1731–1738. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dworzak MN, Froschl G, Printz D, et al. Prognostic significance and modalities of flow cytometric minimal residual disease detection in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2002;99(6):1952–1958. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brüggemann M, Raff T, Flohr T, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease quantification in adult patients with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2006;107(3):1116–1123. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raff T, Gokbuget N, Luschen S, et al. Molecular relapse in adult standard-risk ALL patients detected by prospective MRD monitoring during and after maintenance treatment: data from the GMALL 06/99 and 07/03 trials. Blood. 2007;109(3):910–915. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-037093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou J, Goldwasser MA, Li A, et al. Quantitative analysis of minimal residual disease predicts relapse in children with B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia in DFCI ALL Consortium Protocol 95-01. Blood. 2007;110(5):1607–1611. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-045369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borowitz MJ, Devidas M, Hunger SP, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and its relationship to other prognostic factors: a Children's Oncology Group study. Blood. 2008;111(12):5477–5485. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bassan R, Spinelli O, Oldani E, et al. Improved risk classification for risk-specific therapy based on the molecular study of minimal residual disease (MRD) in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Blood. 2009;113(18):4153–4162. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-185132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conter V, Bartram CR, Valsecchi MG, et al. Molecular response to treatment redefines all prognostic factors in children and adolescents with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results in 3184 patients of the AIEOP-BFM ALL 2000 study. Blood. 2010;115(16):3206–3214. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-248146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schrappe M, Valsecchi MG, Bartram CR, et al. Late MRD response determines relapse risk overall and in subsets of childhood T-cell ALL: results of the AIEOP-BFM-ALL 2000 study. Blood. 2011;118(8):2077–2084. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-338707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coustan-Smith E, Gajjar A, Hijiya N, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia after first relapse. Leukemia. 2004;18(3):499–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paganin M, Zecca M, Fabbri G, et al. Minimal residual disease is an important predictive factor of outcome in children with relapsed ‘high-risk’ acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22(12):2193–2200. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raetz EA, Borowitz MJ, Devidas M, et al. Reinduction platform for children with first marrow relapse of acute lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Children's Oncology Group Study[corrected]. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(24):3971–3978. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bader P, Kreyenberg H, Henze GH, et al. Prognostic value of minimal residual disease quantification before allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the ALL-REZ BFM Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(3):377–384. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.6065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Topp MS, Kufer P, Gokbuget N, et al. Targeted therapy with the T-cell-engaging antibody blinatumomab of chemotherapy-refractory minimal residual disease in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients results in high response rate and prolonged leukemia-free survival. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(18):2493–2498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.