SUMMARY

The low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor family is a large evolutionarily conserved group of transmembrane proteins. It has been shown that LDL receptor family members can also function as direct signal transducers or modulators for a broad range of cellular signalling pathways. We have identified a novel mode of signalling pathway integration/coordination that occurs outside cells during development that involves an LDL family member. Physical interaction between an extracellular protein (Wise) that binds BMP ligands and an Lrp receptor (Lrp4) that modulates Wnt signalling, acts to link these two pathways. Mutations in either Wise or Lrp4 in mice produce multiple, but identical abnormalities in tooth development that are linked to alterations in BMP and Wnt signalling. Teeth, in common with many other organs, develop by a series of epithelial - mesenchymal interactions, orchestrated by multiple cell signalling pathways. In tooth development, Lrp4 is expressed exclusively in epithelial cells and Wise mainly in mesenchymal cells. Our hypothesis, based on the mutant phenotypes, cell signalling activity changes and biochemical interactions between Wise and Lrp4 proteins, is that Wise and Lrp4 together act as an extracellular mechanism of coordinating BMP and Wnt signalling activities in epithelial-mesenchymal cell communication during development.

Keywords: Lrp4, Wise, grooved incisor, Tooth development, Tooth number, Supernumerary tooth, Fusion tooth, Shh, Bmp, Wnt, Palatal rugae

INTRODUCTION

All ectodermal appendages (e.g. hair, teeth, nails, feathers, scales and glands) are derivatives of the embryonic ectoderm and develop through epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. Despite the diversity and the highly specialized functions of these organs, they share common features during early stages of development where epithelium thickens to form placodes and the underlying mesenchymal cells condense [Thesleff et al., 1995; Pispa and Thesleff 2003; Mikkola 2007]. In addition to structural features, these organs also utilize similar signalling pathways including Wnt, Shh, Bmp and Fgf during early stages of their development [Thesleff et al., 1995; Pispa and Thesleff 2003; Mikkola 2007].

The low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor family is a large, evolutionarily conserved group of transmembrane proteins [for reviews, see Nykjaer et al., 2002; Herz and Bock 2002]. The LDL receptor was first identified as an endocytic receptor that transports lipoprotein into cells by receptor-mediated endocytosis. In this process, specific ligands are internalized after binding to their receptors on the cell surface from where they are moved to an intracellular vesicle (endosome) and then discharged to other compartments inside the cell. The LDL receptor mainly regulates the concentration of lipoproteins in the extracellular fluids and delivers them to cells (i.e. for uptake of cholesterol). Recent findings have shown that LDL receptor family members can also function as direct signal transducers or modulators for a broad range of cellular signalling pathways. Lrp5 and Lrp6 for example, function as co-receptors in the Wnt signalling cascade [Pinson et al., 2000; Tamai et al., 2000; Wehrli et al., 2000].

Lrp4 (also called Megf7) belongs to the LDL receptor family. It is initially discovered by Nakayama et al. [1998] from proteins identified with multiple EGF-like motifs during motif-trap screening in mammalian cells, and was also identified in Drosophila [Adams et al. 2000]. Lrp4 is intermediary in size and complexity between the smaller LDL receptors, Ldlr, Apoer2 and Vldlr, and the larger Lrp1, Lrp1b and megalin [Herz and Bock, 2002; Herz et al., 2009].

A secreted BMP antagonist, Wise (also known as USAG-1, Sosdc1 and Ectodin) contains a cystine-knot motif, a structure seen in other secreted molecules such as Tgfβ, Dan and CCN-family members. Wise shows relatively high homology with Sclerostin and moderate homology to Dan and other CCN-family members. These molecules have been shown to be associated with the Wnt signalling pathway [Ellies et al., 2006; Li et al., 2005; Mercurio et al., 2004; Semehov et al., 2005]. Previous studies in Xenopus showed binding of Wise to an extracellular domain of Lrp5/6 that also binds Wnt ligands. Wise acts either positively or negatively on the Wnt pathway depending on the context [Itasaki et al., 2003]. Presence (or overexpression) of Lrp4 inhibits canonical Wnt signals [Johnson et al., 2005]. A consequence of these events is displacement of Wnt ligands and repression of Wnt activity in cells that either express Lrp4, are exposed to Wise, or both. Lrp4 has an extracellular domain structure similar to that of Lrp5 and Lrp6. Using two different biochemical assays we have shown that Wise binds to a domain of Lrp4 that is conserved in Lrp5/6 [Ohazama et al., 2008].

In this review we discuss recent work that identifies an interaction between Wise and Lrp4, that provides a novel method of extracellular communication between mesenchymal and epithelial cells based on the integration of Wnt and Bmp pathways. This integration occurs in the context of epithelial-mesenchymal signaling controlling processes that regulate the development of craniofacial organs, especially teeth.

Expression of Lrp4/Wise and mouse mutants

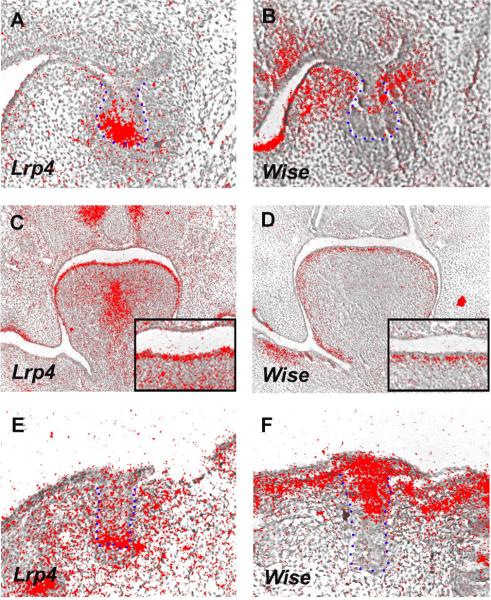

Lrp4 and Wise are expressed during development of many organs including the limb, tooth, lung, kidney and hair [Laurikkala et al., 2003; Yanagita et al., 2004; Wheatherbee et al., 2006; Kassai et al., 2005; Shigetani and Itasaki 2007; Ohazama et al., 2008]. Lrp4 is expressed in the brain, bone and mammary buds, the dorsal neural tube, floorplate and in the post-synaptic endplate region of muscles [Wheatherbee et al., 2006; Choi et al., 2009]. Wise expression is observed in the trigeminal nerves in the testis and spinal ganglia [Laurikkala et al., 2003; Wheatherbee et al., 2006; Shigetani and Itasaki 2007]. Lrp4 and Wise are expressed in a complementary manner in teeth, tongue papillae and hair development (Fig. 1) [Ohazama et al., 2008] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The expression patterns of Lrp4 and Wise.

(A, B) Molar tooth germ. Lrp4 (A) is expressed in enamel knots whereas Wise (B) expression is observed in both epithelium and mesenchyme but is absent from primary enamel knots. (C, D) Developing tongue. Lrp4 (C) is expressed in tongue papilla epithelium whereas Wise (D) expression is found in mesenchyme facing to epithelium. Insets are high magnification of tongue papillae (E, F) Developing hair follicle. Lrp4 (E) is expressed in tip of hair epithelium whereas Wise (F) expression is found in hair epithelium but is absent from the tip of epithelium. Epithelium outlined in blue in developing tooth and hair. Radioactive in situ hybridisation on frontal sections showing Lrp4 and Wise expression in embryo heads at E13.5. A and B are modified from Ohazama et al., 2008.

ENU-induced Lrp4 null mutants die at birth from a failure to expand the air passages in their lungs and also show paralysis due to an early block in the development of a specialized synapse, the neuromuscular junction [Wheatherbee et al., 2006]. However, several other allelic mutations at the Lrp4 locus have been reported that survive [Johnson et al., 2005; Simon-Chazottes et al., 2006; Drogemuller et al., 2007]. A retroviral-derived allele appears to be hypomorphic, because wild-type transcripts are present in these mutants [Simon-Chazottes et al., 2006]. A second allele was generated by targeted mutation by introducing a stop codon just upstream of the transmembrane domain. This allele is also assumed to be hypomorphic, since it has an identical phenotype to the retrovirally-derived alleles [Johnson et al., 2005; Wheatherbee et al., 2006; Simon-Chazottes et al., 2006]. Both null and hypomorphic mutations of Lrp4 result in polysyndactyly and fusion of digits [Johnson et al., 2005; Simon-Chazottes et al., 2006; Wheatherbee et al., 2006]. Lrp4 mutant mice also have shortened femur length and reduced bone volume [Choi et al., 2009]. Wise mutants are viable, fertile, and appear healthy although they do have defects in several organs [Kassai et al., 2005; Yanagita et al., 2004; Murashima-Sugino et al., 2007; Ohazama et al., 2008]. Both Lrp4 and Wise mutant mice exhibit kidney abnormalities [Yanagita et al., 2004; Wheatherbee et al., 2006].

Wise and Lrp4 are co-expressed during early development of many craniofacial organs (Fig. 1) [Laurikkala et al., 2003; Weatherbee et al., 2006; Ohazama et al 2009]. In both Wise and Lrp4 mutant mice, the orofacial region show a variety of abnormalities including supernumerary incisors and molars, fused molars, grooved incisors, increase number of molar cusps, calcified tissues in pulp cavity and disorganized palatal rugae [Kassai et al., 2005; Shigetani and Itasaki 2007; Ohazama et al., 2008].

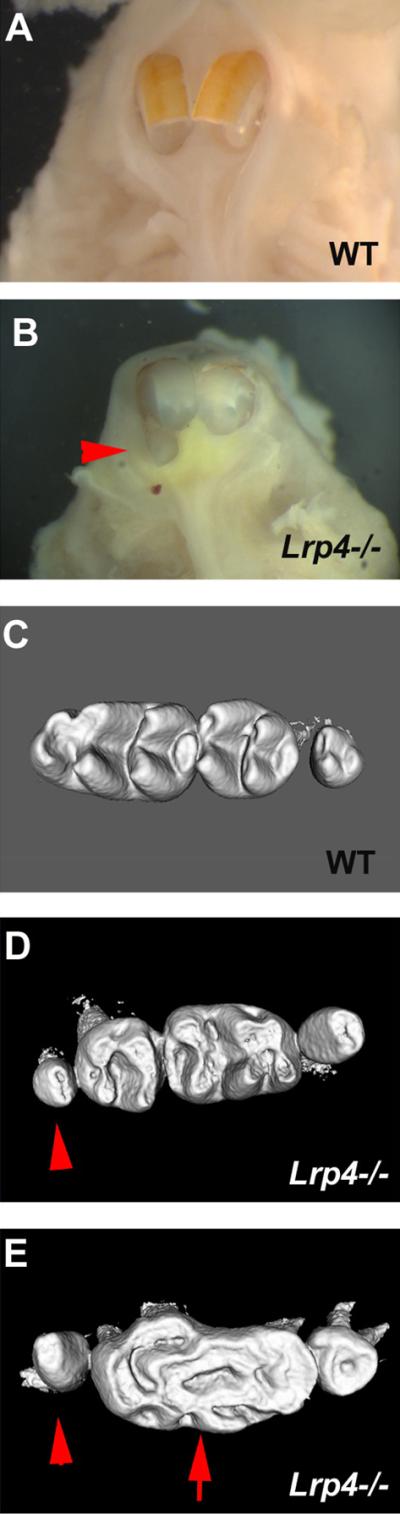

Supernumerary incisor teeth

Mice have only one incisor in each jaw quadrant, however supernumerary incisors are observed in both the maxilla and mandible in Lrp4 mutants (Fig. 2). An identical incisor phenotype is also seen in Wise mutants [Murashima-Sugino et al., 2007; Ohazama et al., 2008]. Supernumerary maxillary incisors have also been reported in humans but are rare [Tsai et al., 1998; Lourenco Ribeiro et al., 2003]. It has been suggested that the failure of facial process fusion results in the supernumerary incisor formation [Kriangkrai et al., 2006]. However, Lrp4 and Wise mutants show no cleft palate and also have supernumerary incisors in the mandible.

Figure 2. Tooth phenotype of Lrp4 mutants.

(A, B) Upper incisors. supernumerary incisors in Lrp4 mutants (arrohead in B). (C–E) Upper molars. Supernumerary molar (arrowheads in D, E) and fusion molar (arrow in E) in Lrp4 mutant mice. Occlusal view of teeth in wild-type (A, C) and Lrp4 mutant mice (B, D, E). Fig.2 is modified from Ohazama et al., 2008.

In wild-type mice embryos, vestigial tooth germs are found in the incisor region that degenerate by apoptosis during development [Peterkova et al., 2002]. The supernumerary incisors in Wise mutants are thought to form as a result of the successive development of the rudimentary tooth germs, since apoptosis is reduced in the incisor region [Murashima-Suginami et al., 2007]. Ectopic Shh expression in developing incisor regions of Lrp4 and Wise mutants is indicative of the survival of rudimentary tooth germs [Hardcastle et al., 1998]. It has been shown that dental mesenchyme can inhibit supernumerary incisor tooth induction by regulating Bmp and Wnt signaling and Wise has been proposed to be a central modulator of this inhibitorial potential of dental mesenchyme [Munne et al., 2009].

Supernumerary molar teeth

Both Lrp4 and Wise mutants have supernumerary teeth in the diastema region, mesial to the first molars (Fig. 2) [Kassai et al., 2005; Ohazama et al., 2008]. The formation of supernumerary teeth (mesial) anterior to the first molars, in the position of a premolar, has been described in several different mice with mutations that affect Fgf, Eda, Bmp and Shh signaling (Coubourne and Sharpe 2010).

The supernumerary teeth in Lrp4 mutants closely resemble those found in Wise mutants and their development can be first visualised by an ectopic patch of Shh expression in the diastema at E14.5 [Ohazama et al., 2008]. Interestingly at this same stage, the expression of Shh in the developing molars, located a few microns more proximally, is significantly reduced in Lrp4 mutant embryos. This suggests parallels with the context-dependent role of Wise in Wnt signalling described in Xenopus where it can either activate or antagonise Wnt signalling [Itasaki et al., 2003]. Primary cilia protrude from the cell surface into the extracellular space and are found in virtually all eukaryotic cells where they are thought to function as chemosensors and/or mechanosensors in many tissues. Primary cilia have been recently found to mediate Hh signalling and mutations in their protein components affect Hh activity. Intraflagellar transport (IFT) proteins are highly conserved in all ciliated eukaryotic cells, and mutation of the proteins that comprise the IFT process result in defects in cilia formation in all organisms studied to date [Rosenbaum and Witman, 2002; Pan et al., 2005; Scholey and Anderson, 2006]. Mice with null mutations in the IFT88 gene, which encodes the IFT protein Polaris, lack cilia on all cells and die mid-gestation with severe defects in neural tube patterning and closure, polydactyly, and left-right axis determination [Murcia et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2003]. Tg737orpk is a hypomorphic allele of Polaris and homozygous Tg737orpk mice exhibit supernumerary teeth in the diastema, that is caused by the ectopic activation of Shh signalling [Ohazama et al., 2009]. Mutants in the Shh regulatory protein, Gas1 also develop diastema teeth as a result of ectopic Shh activity in diastema mesenchyme [Ohazama et al., 2009]. Therefore, in the context of control of tooth number, Shh activity is repressed in the wild-type diastema.

Eda and Edar belong to the TNF family and have been shown to regulate tooth morphogenesis by inducing the NF-κB pathway [Ohazama and Sharpe, 2004]. Eda heterozygous mutant mice as well as mice overexpressing Eda and Edar under Keratin 14 (K14) also show a supernumerary tooth anterior to the first molar [Mustonen et al., 2003; Tucker et al., 2004; Peterková et al., 2005]. Ectopic Shh expression in front of the forming first molar is also observed in these transgenic mice [Mustonen et al., 2004]. Interestingly, Lrp4 is involved in Eda/NF-kB pathways in hair development [Fliniaux et al., 2008].

The Sprouty (Spry) family containing four Spry genes (Spry 1–4) has been shown to be a negative feedback regulator of FGF and other receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signalling pathways [Hacohen et al., 1998; Kim & Bar-Sagi, 2004]. Sprouty genes are required for the development of several organs [Zhang et al., 2001]. During tooth development, different Sprouty genes are expressed in different tissue compartments. Spry2 is deployed in the dental epithelium while Spry4 is expressed in the mesenchyme. Spry2 and Spry4 deficient mice also show a supernumerary tooth in the diastema region. [Klein et al., 2006]. It has been demonstrated that Spry2 and Spry4 prevent tooth buds formation in the diastema region via regulation of FGF signalling. We have found a change in Fgf signalling in molar regions of Lrp4 mutants (Sharpe lab unpublished data). It has been shown that the inhibition of Fgf signalling has no effect on the Bmp4 and Shh expression in tooth development (Mandler and Neubuser 2001). The possible primary role of Fgf signalling in supernumerary tooth formation in Lrp4 mutants however remains unclear but is likely to lie downstream of the Bmp/Shh interactions. In addition to supernumerary molars, small lingual peg-shaped extra teeth were also evident in Lrp4 and Wise mutant [Kassai et al., 2005; Ohazama et al., 2008].

Fused molars

Lrp4 and Wise mutants have large molar crowns that form from a fusion of first and second molars with a anterior supernumerary tooth (Fig. 2) [Ohazama et al., 2008]. Increased Wnt and Bmp signalling and reduced Shh signalling, as a result of loss of either Wise or Lrp4, are found in the fusion of molar teeth. This fusion occurs when the epithelial cells in junctional regions between the individual tooth germs, differentiate into inner enamel epithelial cells. The reduction in Shh signalling that accompanies the increase in Bmp/Wnt activity is functionally important since conditional loss of Shh in dental epithelium also produces similar molar tooth fusions [Gritli-Linde et al., 2002; Dassule et al., 2000]. Another member of the LDL receptor family, Megalin, has been reported to bind Shh and loss of Megalin results in reduction of Shh expression in ventral forebrain development [McCarthy et al., 2002; Spoelgen et al., 2005]. It has been shown that proteases interact with LRPs to antagonize SHH-induced cell proliferation and that it inhibits the Shh signalling activity in cerebellum, suggesting that there may be direct interaction between Lrp4 and Shh [Vaillant et al., 2007]. However, the overexpression of Bmp4 inhibits Shh expression in molars and Shh signalling depends on the Wnt pathway in tongue papillae development [Zhao et al., 2000; Iwatsuki et al., 2007]. These results suggest that changes of other downstream signalling pathways inhibit Shh activity. This common morphogenetic pathway may also include limb development since Lrp4 mutants exhibit polysyndactyly with digit fusions and molecular changes that include reduction in Shh signalling [Johnson et al., 2005].

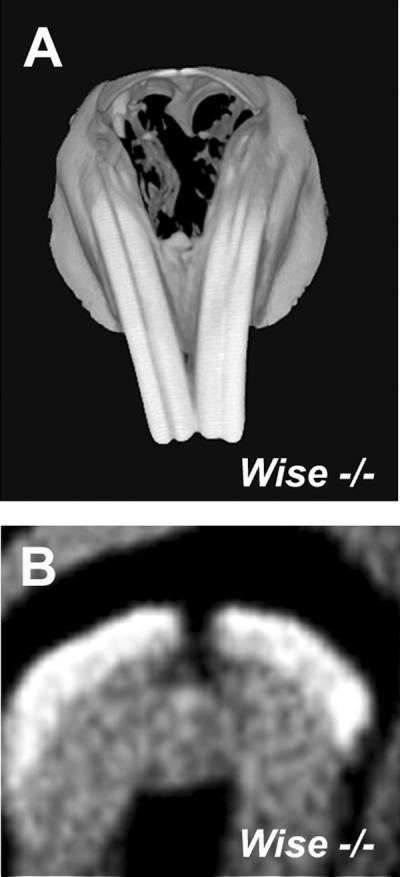

Grooved incisors and tooth cusp formation

Vertical grooves are detected on the labial surface of maxillary incisors in Lrp4 and Wise mutants, rabbits and some wild-type rodents also show grooved incisors. Downregulation of Shh and Bmp signalling occurs during groove formation in Lrp4 mutants. We have shown that the groove is equivalent to the enamel-free zone located at the tips of cusps of mouse molars [Ohazama et al 2010]. The vertical grooved incisors are also observed in Wise mutants (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Grooves in incisors of Wise mutant mice.

Grooved incisors are found in Wise mutant. (B) Cross sections of incisors showed that grooves are caused by lack of enamel. 3D reconstructions (A) and cross section (B) based on micro-CT scans.

Calcified tissues in pulp cavity

Lrp4 mutants occasionally show calcified tissues in the pulp cavity of incisors (Fig. 4). One type of calcified tissue that can form in pulp cavites is “dens in dente” (tooth within tooth) that are fully erupted teeth with extremely deep pits that commonly affects the maxillary lateral incisor. This condition results from either downward proliferation of a portion of the internal enamel epithelium of the enamel organ into the dental papilla or from retarded growth of part the tooth germ [Berkovitz et al., 2002; Mupparapu and Sinqer 2006; Hulsman 1997].

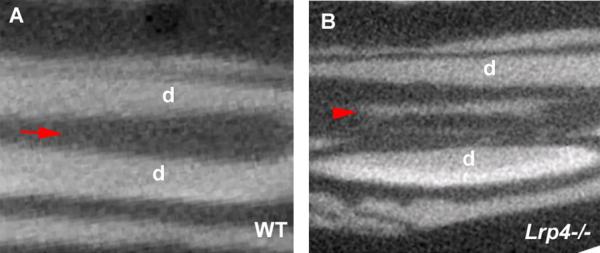

Figure 4. Calcified tissues in pulp cavity of Lrp4 mutants.

(A, B) Upper incisors. Calcified tissue in pulp cavity of Lrp4 mutants (B). Incisor of wild-type (A). Cross section as sagittal plane based on micro-CT scans of maxillary incisors. Arrow indicates the pulp cavity of wild-type. Arrowhead show Calcified tissues in pulp cavity of Lrp4 mutants.

Disorganized palatal rugae

Palatal rugae are corrugated structures of the hard palate that are thought to assist the holding and crushing food between the tongue and the palate and in aiding the tongues correct placement for the production of certain speech sounds. Numerous nerve fibers are found to assemble in the rugae, which are considered to respond to touch and pressure on the palate during chewing, swallowing and speech [Mitsui et al. 2000; Ichikawa et al., 2001; Kido et al., 2003; Nunzi et al., 2004]. Although rodent palatal rugae development is under strict genetic control, since their number and the patterns are species specific, the molecular mechanisms regulating their development are largely unknown. Wise and Lrp4 mutant mice showed highly disorganized palatal rugae [Welsh and O'Brien, 2009; Sharpe lab unpublished data]. Increased Bmp and Wnt signalling and reduced Shh expression are found in palatal rugae in both mutants (Sharpe lab unpublished data).

The interaction between Lrp4 and Lrp5/6

Recently, an interaction between Lrp4 and Lrp5/6 has been identified in bone biology. The Sost gene, which encodes for the osteocyte secreted protein sclerostin, has been identified as a secreted antagonist of both Bmp and Wnt signalling pathway [Kusu et al., 2003; Winkler et al., 2003; 2005; Li et al., 2005]. Sclerostin shows a high homology with Wise and directly binds to Lrp5 and Lrp6 [Li et al., 2005; Ellies et al., 2006]. Another soluble inhibitor of Wnt signaling, Dkk1 that binds to Lrp5 and Lrp6, can displace sclerostin from the sclerostin/Lrp5 complex [Balemans et al., 2008]. Lrp4 binds Dkk1 and sclerostin and Lrp4 mutants have reduced bone volume whereas Sost mutation leads to increased bone formation [Winkler et al., 2003; Loots et al., 2005; Choi et al., 2009] Lrp4 may thus compete with Lrp5 and Lrp6 for sclerostin and Dkk1 or cooperate with Lrp5 and Lrp6 by ligands in bone [Choi et al., 2009].

Lrp4-Wise interaction – a role in extracellular signaling integration

The accepted view of cell signaling by secreted proteins is that cell-cell communication is mediated by ligands binding to specific cell surface receptors that transmit an intracellular response. Secreted antagonists may also bind to the ligands to prevent pathway activation and presumably the ligands must be removed from the extracellular environment, possibly by endocytosis. This removal of ligands is of critical importance in signaling in epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in development. In tooth development for example, the same ligands are repeatedly used as epithelial signals and mesenchymal signals at different times and this can only work if the ligands are removed very rapidly and effectively.

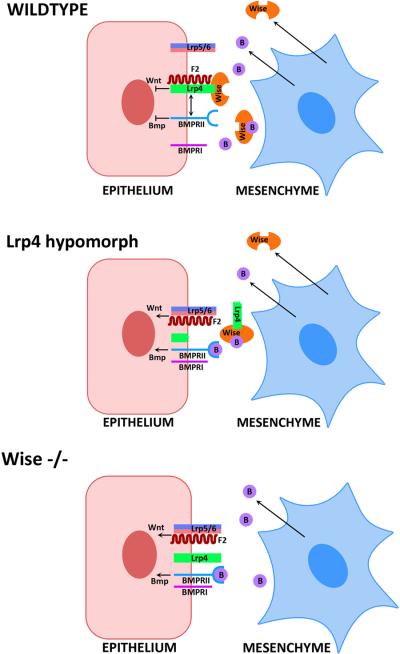

We have shown that the Wnt co-receptor, Lrp4 and a secreted BMP antagonist, Wise, are interacting proteins that when mutated produce identical orofacial phenotypes and downstream molecular changes [Ohazama et al. 2008]. A mutation of the Wnt co-receptor, Lrp4 that results in the extracellular domain being cleaved from the cell surface and a null mutation in the secreted BMP antagonist, Wise, produce an identical spectrum of tooth (and other) phenotypes [Ohazama et al 2008]. In both Wise and Lrp4 mutants, a similar upregulation of BMP and canonical Wnt activity in target, Lrp4 expressing cells, has been identified during tooth and palate development [Ohazama et al 2008]. Thus, loss of Wise or Lrp4 function results in the same localized increases in BMP and Wnt activities. Previous studies in Xenopus showed binding of Wise to an extracellular domain of Lrp5/6 that also binds Wnt ligands [Ellis et al 2006]. Similarly, presence (or overexpression) of Lrp4 inhibits canonical Wnt signals [Johnson et al 2005]. A consequence these events is either, in the first case, displacement of Wnt, or in the second case of Lrp5/6 in the Wnt-Lrp5/6-Frizzled complex, resulting in the repression of Wnt activity in cells that either express Lrp4, are exposed to Wise, or both. Using two different biochemical assays we have shown that Wise binds to a domain of Lrp4 that is conserved in Lrp5/6 [Semenov et al 2005; Ohazama et al., 2008]. Furthermore in situ hybridization shows highly restricted complementary expression of Lrp4 in tooth germ epithelial cells and of Wise in mesenchymal cells (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Schematic representation of Lrp4 and Wise.

Schematic representation of the cell signalling changes observed in wildtype, Wise null mutant and Lrp4 hypomorphic mutant during epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in tooth development.

Our conclusions from these findings are that the Wnt activity inhibitory action of Lrp4 requires binding of Wise and that the inhibitory action of Wise on BMP signalling requires Lrp4. In addition this also means that rather than being a simple secreted BMP antagonist, Wise itself acts as a secreted signal modulator between mesenchyme and epithelium. In doing so it integrates BMP and Wnt signalling outside the cell. It has been shown that Wise has separate domains for the physical interaction between BMP4 and LRP6 [Lintern et al., 2009]. In the absence of Wise, BMP activity increases, since the antagonist is lost and Wnt activity increases in epithelial cells since Wise is not present to interact with Lrp4. The fact that loss of Lrp4 produces the same phenotype and molecular changes as loss of Wise, suggests that Wise may require Lrp4 in order to function as a BMP antagonist. Significantly in vitro, excess Lrp6 prevents Wise inhibition of BMPs while in vivo, BMPs are downstream of Wnt /β-catenin in skin [Narhi et al., 2008; Lintern et al 2009].

In wild-type Lrp4 expressing cells, both Wnt and BMP activities are repressed by the action of the binding of Wise, despite the presence of Wnt and BMP ligands. These ligands are presumed to be free to act on other target cells (eg. mesenchyme) not expressing Lrp4. In this way signal responses can be specifically blocked in one cell type while retained in another, an important feature of reciprocal epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. Central to the integrated action of Lrp4 and Wise is the ability of Wise binding to Lrp4 to repress both Wnt and BMP activities in the same cell. Current understanding of Wnt and BMP pathways cannot explain this, nor why Lrp4 appears to be essential for Wise to function as a BMP antagonist. This highlights a major gap in our knowledge of these pathways, particularly in events at the plasma membrane. Based on the developmental significance of regulation of signal directionality and the obvious, newly uncovered role of Lrp4 in Wnt and BMP signalling, it is important that the mode of action of the Lrp4-Wise complex at the plasma membrane is understood.

Based on all the evidence available we propose that Wise binding to Lrp4 acts to recruit Lrp4 into the Fz/Lrp5/6 Wnt receptor complex and in doing so replaces the Lrp5/6 Wnt co-activators in the complex, resulting in a repression of Wnt activity. The accompanied repression of BMP activity could be explained by coincident recruitment of BMP Type II receptors into the complex, resulting in loss of dimerization with BMPRI. We view this mechanism as having similarities to the role of primary cilia in Hedgehog signalling where the cilium acts as a focus (antenna) for the recruitment of plasma membrane proteins involved in activation of the hedgehog pathway [Eggenschwiler and Anderson 2007; Simpson et al., 2009]. Lrp4 is known to be an antagonist of Wnt signalling, unlike Lrp5/6 which are Wnt co-activators, since increasing Lrp4 expression relative to Lrp5/6 suppresses Wnt signalling and because Lrp4 lacks an intracellular Axin binding domain [Pinson 2000, Tamai et al 2000, Herz 2001, Mao et al 2001, Weatherbee et al 2006]. In addition, Lrp4 is known to interact with the Lrp5/6-Frz receptor complex to alter (titrate) the cell response to Wnt ligands [Johnson et al 2005].

Wise, Bmp, Wnt and Lrp4 thus function together to act as a multivalent, dynamically coupled and cell-type specific sensor for Bmp and Wnt ligand activity by regulating the composition of the Wnt and BMP signaling complexes. Restriction of the location of Lrp4 in this case to epithelial cells creates the directionality necessary for signal exchange between mesenchyme and epithelium. The presence of Lrp4 on a particular cell and the concentration of Wise in the extracellular space determines if BMP signaling is activated or repressed on that particular cell, and to what degree Wnt signals can be repressed by Wise.

Aknowledgements

Work in P.S.'s laboratory is funded by the MRC. A.O. is an RCUK Fellow. T.P. is supported by W J B Houston Research Scholarship (Europen Orthodontic Society).

REFERENCES

- Adams MD, Celniker SE, Holt RA, Evans CA, Gocayne JD, Amanatides PG, Scherer SE, Li PW, Hoskins RA, Galle RF, others The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287(5461):2185–95. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkovitz BKB, Holland GR, Moxham BJ. Oral anatomy, histology and embryology. 3rd ed. Mosby; St Louis: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Balemans W, Piters E, Cleiren E, Ai M, Van Wesenbeeck L, Warman ML, Van Hul W. The binding between sclerostin and LRP5 is altered by DKK1 and by high-bone mass LRP5 mutations. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;82:445–53. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HY, Dieckmann M, Herz J, Niemeier A. Lrp4, a novel receptor for Dickkopf 1 and sclerostin, is expressed by osteoblasts and regulates bone growth and turnover in vivo. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassule HR, Lewis P, Bei M, Maas R, McMahon AP. Sonic hedgehog regulates growth and morphogenesis of the tooth. Development. 2000;127(22):4775–85. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.22.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drogemuller C, Leeb T, Harlizius B, Tammen I, Distl O, Holtershinken M, Gentile A, Duchesne A, Eggen A. Congenital syndactyly in cattle: four novel mutations in the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 gene (LRP4) BMC Genet. 2007;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggenschwiler JT, Anderson KV. Cilia and developmental signaling. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:345–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellies DL, Viviano B, McCarthy J, Rey JP, Itasaki N, Saunders S, Krumlauf R. Bone density ligand, Sclerostin, directly interacts with LRP5 but not LRP5G171V to modulate Wnt activity. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(11):1738–49. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliniaux I, Mikkola ML, Lefebvre S, Thesleff I. Identification of dkk4 as a target of Eda-A1/Edar pathway reveals an unexpected role of ectodysplasin as inhibitor of Wnt signalling in ectodermal placodes. Dev Biol. 2008;320(1):60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritli-Linde A, Bei M, Maas R, Zhang XM, Linde A, McMahon AP. Shh signaling within the dental epithelium is necessary for cell proliferation, growth and polarization. Development. 2002;129(23):5323–37. doi: 10.1242/dev.00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacohen N, Kramer S, Sutherland D, Hiromi Y, Krasnow MA. sprouty encodes a novel antagonist of FGF signaling that patterns apical branching of the Drosophila airways. Cell. 1998;92(2):253–63. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80919-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardcastle Z, Mo R, Hui CC, Sharpe PT. The Shh signalling pathway in tooth development: defects in Gli2 and Gli3 mutants. Development. 1998;125(15):2803–11. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz J. The LDL receptor gene family: (un)expected signal transducers in the brain. Neuron. 2001;29:571–581. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00234-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz J, Bock HH. Lipoprotein receptors in the nervous system. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:405–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz J, Chen Y, Masiulis I, Zhou L. Expanding functions of lipoprotein receptors. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S287–92. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800077-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa H, Matsuo S, Silos-Santiago I, Jacquin MF, Sugimoto T. Developmental dependency of Merkel endings on trks in the palate. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;88(1–2):171–5. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itasaki N, Jones CM, Mercurio S, Rowe A, Domingos PM, Smith JC, Krumlauf R. Wise, a context-dependent activator and inhibitor of Wnt signalling. Development. 2003;130:4295–305. doi: 10.1242/dev.00674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsuki K, Liu HX, Gronder A, Singer MA, Lane TF, Grosschedl R, Mistretta CM, Margolskee RF. Wnt signaling interacts with Shh to regulate taste papilla development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2253–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607399104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EB, Hammer RE, Herz J. Abnormal development of the apical ectodermal ridge and polysyndactyly in Megf7-deficient mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(22):3523–38. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassai Y, Munne P, Hotta Y, Penttila E, Kavanagh K, Ohbayashi N, Takada S, Thesleff I, Jernvall J, Itoh N. Regulation of mammalian tooth cusp patterning by ectodin. Science. 2005;309(5743):2067–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1116848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kido MA, Muroya H, Yamaza T, Terada Y, Tanaka T. Vanilloid receptor expression in the rat tongue and palate. J Dent Res. 2003;82(5):393–7. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Bar-Sagi D. Modulation of signalling by Sprouty: a developing story. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5(6):441–50. doi: 10.1038/nrm1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein OD, Minowada G, Peterkova R, Kangas A, Yu BD, Lesot H, Peterka M, Jernvall J, Martin GR. Sprouty genes control diastema tooth development via bidirectional antagonism of epithelial-mesenchymal FGF signaling. Dev Cell. 2006;11(2):181–90. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriangkrai R, Chareonvit S, Yahagi K, Fujiwara M, Eto K, Iseki S. Study of Pax6 mutant rat revealed the association between upper incisor formation and midface formation. Dev Dyn. 2006;235(8):2134–43. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusu N, Laurikkala J, Imanishi M, Usui H, Konishi M, Miyake A, Thesleff I, Itoh N. Sclerostin is a novel secreted osteoclast-derived bone morphogenetic protein antagonist with unique ligand specificity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24113–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurikkala J, Kassai Y, Pakkasjarvi L, Thesleff I, Itoh N. Identification of a secreted BMP antagonist, ectodin, integrating BMP, FGF, and SHH signals from the tooth enamel knot. Dev Biol. 2003;264(1):91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhang Y, Kang H, Liu W, Liu P, Zhang J, Harris SE, Wu D. Sclerostin binds to LRP5/6 and antagonizes canonical Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(20):19883–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413274200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lintern KB, Guidato S, Rowe A, Saldanha JW, Itasaki N. Characterization of wise protein and its molecular mechanism to interact with both Wnt and BMP signals. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23159–68. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.025478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loots GG, Kneissel M, Keller H, Baptist M, Chang J, Collette NM, Ovcharenko D, Plajzer-Frick I, Rubin EM. Genomic deletion of a long-range bone enhancer misregulates sclerostin in Van Buchem disease. Genome Res. 2005;15:928–35. doi: 10.1101/gr.3437105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenco Ribeiro L, Teixeira Das Neves L, Costa B, Ribeiro Gomide M. Dental anomalies of the permanent lateral incisors and prevalence of hypodontia outside the cleft area in complete unilateral cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2003;40(2):172–5. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_2003_040_0172_daotpl_2.0.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandler M, Neubuser A. FGF signaling is necessary for the specification of the odontogenic mesenchyme. Dev Biol. 2001;240:548–59. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J, Wang J, Liu B, Pan W, Farr GH, 3rd, Flynn C, Yuan H, Takada S, Kimelman D, Li L, Wu D. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-5binds to Axin and regulates the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;7:801–809. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy RA, Barth JL, Chintalapudi MR, Knaak C, Argraves WS. Megalin functions as an endocytic sonic hedgehog receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(28):25660–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercurio S, Latinkic B, Itasaki N, Krumlauf R, Smith JC. Connective-tissue growth factor modulates WNT signalling and interacts with the WNT receptor complex. Development. 2004;131(9):2137–47. doi: 10.1242/dev.01045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkola ML. Genetic basis of skin appendage development. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18(2):225–36. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsui C, Iwanaga T, Yoshida S, Kawasaki T. Immunohistochemical demonstration of nerve terminals in the whole hard palate of rats by use of an antiserum against protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5) Arch Histol Cytol. 2000;63(5):401–10. doi: 10.1679/aohc.63.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munne PM, Tummers M, Jarvinen E, Thesleff I, Jernvall J. Tinkering with the inductive mesenchyme: Sostdc1 uncovers the role of dental mesenchyme in limiting tooth induction. Development. 2009;136:393–402. doi: 10.1242/dev.025064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murcia NS, Richards WG, Yoder BK, Mucenski ML, Dunlap JR, Woychik RP. The Oak Ridge Polycystic Kidney (orpk) disease gene is required for left-right axis determination. Development. 2000;127(11):2347–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mupparapu M, Sinqer SR. A review of dens invaginatus (dens in dente) in permanent and primary teeth: report of a case in a microdontic maxillary lateral incisor. Quintessence Int. 2006;37:125–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashima-Suginami A, Takahashi K, Kawabata T, Sakata T, Tsukamoto H, Sugai M, Yanagita M, Shimizu A, Sakurai T, Slavkin HC, others Rudiment incisors survive and erupt as supernumerary teeth as a result of USAG-1 abrogation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;359(3):549–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustonen T, Ilmonen M, Pummila M, Kangas AT, Laurikkala J, Jaatinen R, Pispa J, Gaide O, Schneider P, Thesleff I, others Ectodysplasin A1 promotes placodal cell fate during early morphogenesis of ectodermal appendages. Development. 2004;131(20):4907–19. doi: 10.1242/dev.01377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustonen T, Pispa J, Mikkola ML, Pummila M, Kangas AT, Pakkasjarvi L, Jaatinen R, Thesleff I. Stimulation of ectodermal organ development by Ectodysplasin-A1. Dev Biol. 2003;259(1):123–36. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narhi K, Jarvinen E, Birchmeier W, Taketo MM, Mikkola ML, Thesleff I. Sustained epithelial beta-catenin activity induces precocious hair development but disrupts hair follicle down-growth and hair shaft formation. Development. 2008;135:1019–28. doi: 10.1242/dev.016550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunzi MG, Pisarek A, Mugnaini E. Merkel cells, corpuscular nerve endings and free nerve endings in the mouse palatine mucosa express three subtypes of vesicular glutamate transporters. J Neurocytol. 2004;33(3):359–76. doi: 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000044196.45602.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nykjaer A, Willnow TE. The low-density lipoprotein receptor gene family: a cellular Swiss army knife? Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12(6):273–80. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02282-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohazama A, Johnson EB, Ota MS, Choi HY, Porntaveetus T, Oommen S, Itoh N, Eto K, Gritli-Linde A, Herz J, others Lrp4 modulates extracellular integration of cell signaling pathways in development. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e4092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohazama A, Sharpe PT. TNF signalling in tooth development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14(5):513–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohazama A, Haycraft CJ, Seppala M, Blackburn J, Ghafoor S, Cobourne M, Martinelli DC, Fan CM, Peterkova R, Lesot H, others Primary cilia regulate Shh activity in the control of molar tooth number. Development. 2009;136(6):897–903. doi: 10.1242/dev.027979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohazama A, Blackburn J, Porntaveetus T, Ota MS, Choi HY, Johnson EB, Myers P, Oommen S, Eto K, Kessler JA, Kondo T, Fraser GJ, Streelman JT, Pardinas UF, Tucker AS, Ortiz PE, Charles C, Viriot L, Herz J, Sharpe PT. A role for suppressed incisor cuspal morphogenesis in the evolution of mammalian heterodont dentition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:92–97. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907236107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Wang Q, Snell WJ. Cilium-generated signaling and cilia-related disorders. Lab Invest. 2005;85(4):452–63. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterkova R, Lesot H, Viriot L, Peterka M. The supernumerary cheek tooth in tabby/EDA mice-a reminiscence of the premolar in mouse ancestors. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50(2):219–25. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterkova R, Peterka M, Viriot L, Lesot H. Development of the vestigial tooth primordia as part of mouse odontogenesis. Connect Tissue Res. 2002;43(2–3):120–8. doi: 10.1080/03008200290000745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinson KI, Brennan J, Monkley S, Avery BJ, Skarnes WC. An LDL-receptor-related protein mediates Wnt signalling in mice. Nature. 2000;407(6803):535–8. doi: 10.1038/35035124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pispa J, Thesleff I. Mechanisms of ectodermal organogenesis. Dev Biol. 2003;262(2):195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB. Intraflagellar transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3(11):813–25. doi: 10.1038/nrm952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholey JM, Anderson KV. Intraflagellar transport and cilium-based signaling. Cell. 2006;125(3):439–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenov M, Tamai K, He X. SOST is a ligand for LRP5/LRP6 and a Wnt signaling inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(29):26770–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigetani Y, Itasaki N. Expression of Wise in chick embryos. Dev Dyn. 2007;236(8):2277–84. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon-Chazottes D, Tutois S, Kuehn M, Evans M, Bourgade F, Cook S, Davisson MT, Guenet JL. Mutations in the gene encoding the low-density lipoprotein receptor LRP4 cause abnormal limb development in the mouse. Genomics. 2006;87(5):673–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson F, Kerr MC, Wicking C. Trafficking, development and hedgehog. Mech Dev. 2009;126:279–88. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoelgen R, Hammes A, Anzenberger U, Zechner D, Andersen OM, Jerchow B, Willnow TE. LRP2/megalin is required for patterning of the ventral telencephalon. Development. 2005;132(2):405–14. doi: 10.1242/dev.01580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai K, Semenov M, Kato Y, Spokony R, Liu C, Katsuyama Y, Hess F, Saint-Jeannet JP, He X. LDL-receptor-related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature. 2000;407(6803):530–5. doi: 10.1038/35035117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thesleff I, Vaahtokari A, Partanen AM. Regulation of organogenesis. Common molecular mechanisms regulating the development of teeth and other organs. Int J Dev Biol. 1995;39(1):35–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai TP, Huang CS, Huang CC, See LC. Distribution patterns of primary and permanent dentition in children with unilateral complete cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1998;35(2):154–60. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1998_035_0154_dpopap_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker AS, Headon DJ, Courtney JM, Overbeek P, Sharpe PT. The activation level of the TNF family receptor, Edar, determines cusp number and tooth number during tooth development. Dev Biol. 2004;268(1):185–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant C, Michos O, Orolicki S, Brellier F, Taieb S, Moreno E, Te H, Zeller R, Monard D. Protease nexin 1 and its receptor LRP modulate SHH signalling during cerebellar development. Development. 2007;134:1745–54. doi: 10.1242/dev.02840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherbee SD, Anderson KV, Niswander LA. LDL-receptor-related protein 4 is crucial for formation of the neuromuscular junction. Development. 2006;133(24):4993–5000. doi: 10.1242/dev.02696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrli M, Dougan ST, Caldwell K, O'Keefe L, Schwartz S, Vaizel-Ohayon D, Schejter E, Tomlinson A, DiNardo S. arrow encodes an LDL-receptor-related protein essential for Wingless signalling. Nature. 2000;407(6803):527–30. doi: 10.1038/35035110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh IC, O'Brien TP. Signaling integration in the rugae growth zone directs sequential SHH signaling center formation during the rostral outgrowth of the palate. Dev Biol. 2009;336:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler DG, Sutherland MK, Geoghegan JC, Yu C, Hayes T, Skonier JE, Shpektor D, Jonas M, Kovacevich BR, Staehling-Hampton K, Appleby M, Brunkow ME, Latham JA. Osteocyte control of bone formation via sclerostin, a novel BMP antagonist. Embo J. 2003;22:6267–76. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler DG, Sutherland MS, Ojala E, Turcott E, Geoghegan JC, Shpektor D, Skonier JE, Yu C, Latham JA. Sclerostin inhibition of Wnt-3a-induced C3H10T1/2 cell differentiation is indirect and mediated by bone morphogenetic proteins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2498–502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagita M, Oka M, Watabe T, Iguchi H, Niida A, Takahashi S, Akiyama T, Miyazono K, Yanagisawa M, Sakurai T. USAG-1: a bone morphogenetic protein antagonist abundantly expressed in the kidney. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316(2):490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Lin Y, Itaranta P, Yagi A, Vainio S. Expression of Sprouty genes 1, 2 and 4 during mouse organogenesis. Mech Dev. 2001;109(2):367–70. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00526-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Murcia NS, Chittenden LR, Richards WG, Michaud EJ, Woychik RP, Yoder BK. Loss of the Tg737 protein results in skeletal patterning defects. Dev Dyn. 2003;227(1):78–90. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Zhang Z, Song Y, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Hu Y, Fromm SH, Chen Y. Transgenically ectopic expression of Bmp4 to the Msx1 mutant dental mesenchyme restores downstream gene expression but represses Shh and Bmp2 in the enamel knot of wild type tooth germ. Mech Dev. 2000;99:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00467-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]