Abstract

Background

Glycopeptidolipids (GPLs) are among the major free glycolipid components of the outer membrane of several saprophytic and clinically-relevant Mycobacterium species. The architecture of GPLs is based on a constant tripeptide-amino alcohol core of nonribosomal peptide synthetase origin that is N-acylated with a 3-hydroxy/methoxy acyl chain synthesized by a polyketide synthase and further decorated with variable glycosylation patterns built from methylated and acetylated sugars. GPLs have been implicated in many aspects of mycobacterial biology, thus highlighting the significance of gaining an understanding of their biosynthesis. Our bioinformatics analysis revealed that every GPL biosynthetic gene cluster known to date contains a gene (referred herein to as gplH) encoding a member of the MbtH-like protein family. Herein, we sought to conclusively establish whether gplH was required for GPL production.

Results

Deletion of gplH, a gene clustered with nonribosomal peptide synthetase-encoding genes in the GPL biosynthetic gene cluster of Mycobacterium smegmatis, produced a GPL deficient mutant. Transformation of this mutant with a plasmid expressing gplH restored GPL production. Complementation was also achieved by plasmid-based constitutive expression of mbtH, a paralog of gplH found in the biosynthetic gene cluster for production of the siderophore mycobactin of M. smegmatis. Further characterization of the gplH mutant indicated that it also displayed atypical colony morphology, lack of sliding motility, altered capacity for biofilm formation, and increased drug susceptibility.

Conclusions

Herein, we provide evidence formally establishing that gplH is essential for GPL production in M. smegmatis. Inactivation of gplH also leads to a pleiotropic phenotype likely to arise from alterations in the cell envelope due to the lack of GPLs. While genes encoding MbtH-like proteins have been shown to be needed for production of siderophores and antibiotics, our study presents the first case of one such gene proven to be required for production of a cell wall component. Furthermore, our results provide the first example of a mbtH-like gene with confirmed functional role in a member of the Mycobacterium genus. Altogether, our findings demonstrate a critical role of gplH in mycobacterial biology and advance our understanding of the genetic requirements for the biosynthesis of an important group of constituents of the mycobacterial outer membrane.

Background

The cell envelope of members of the Mycobacterium genus contains a unique array of structurally-complex free lipids thought to be non-covalently bound to the mycolic acid layer of the cell wall [1-3]. These free lipids are believed to form a membrane outer leaflet that partners with a mycolic acid-based membrane inner leaflet to form an asymmetric lipid bilayer-like structure. This lipid bilayer constitutes the distinctive outer membrane of the mycobacterial cell envelope. The documented role of some of these free lipids as mycobacterial virulence effectors highlights the enzymes involved in their production as potential target candidates for exploring the development of novel drugs that could assist conventional antimicrobial therapy in the control of mycobacterial infections. Notably, the first inhibitor of the biosynthesis of a group of these free lipids (i.e., phenolic glycolipids [3]) has been recently reported [4]. The inhibitor works in a manner analogous to that of the first reported inhibitor of siderophore (iron chelator) biosynthesis [5,6], and it blocks the production of phenolic glycolipids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other mycobacterial pathogens [4].

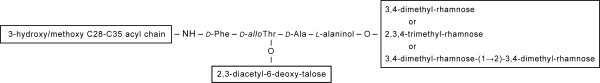

Glycopeptidolipids (GPLs) are among the major free glycolipid components of the outer membrane of several Mycobacterium species [7,8] (Figure 1). The GPL-producing species include saprophytic mycobacteria, such as Mycobacterium smegmatis (Ms), and many clinically-relevant nontuberculous mycobacteria. The members of the Mycobacterium avium-Mycobacterium intracellulare complex (MAC) are among the GPL producers of clinical significance. MAC infections cause pulmonary and extrapulmonary diseases in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals [9,10]. Importantly, GPLs have been implicated in many aspects of mycobacterial biology, including host-pathogen interaction [11-17], sliding motility [18,19], and biofilm formation [18,20]. An altered expression profile of GPLs has been observed in drug-resistant clinical isolates of MAC [21], a finding that raises the possibility that GPL production might have an impact on drug susceptibility as well. Thus, elucidation of the GPL biosynthetic pathway is important not only because it will expand our understanding of cell wall biosynthesis in mycobacteria, but it may also illuminate potential routes to alternative therapeutic strategies against infections by MAC and other opportunistic mycobacterial human pathogens.

Figure 1.

Representative structures of glycopeptidolipids. The depicted GPLs correspond to those found in Mycobacterium smegmatis.

Structures of GPLs from several mycobacteria have been characterized (reviewed in references [7,8]). In brief, GPL molecules are composed of an N-acylated lipopeptide core decorated by a variable pattern of glycosylation that is built from O-methylated and O-acetylated sugar units. The peptide moiety is the tripeptide-amino alcohol D-phenylalanine-D-allothreonine-D-alanine-L-alaninol (D-Phe-D-alloThr-D-Ala-L-alaninol). This tripeptide-amino alcohol is assembled by nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) designated Mps1 and Mps2 in Ms[22-25], whereas biosynthesis of the lipid substituent (3-hydroxy/methoxy C28-C35 acyl chain) is believed to require a dedicated polyketide synthase (PKS) [24]. NRPSs and PKSs are two large families of enzymes that are best known for their involvement in the synthesis of natural products with pharmacological activities of clinical significance [26,27] and microbial siderophores [28,29]. N-acylation of the tripeptide-amino alcohol of Ms GPLs has been proposed to require the protein PapA3 [24], a member of the polyketide-associated protein (Pap) family of acyltransferases [30,31]. Lastly, various glycosyltransferases, methyltransferases and acetyltransferases have been implicated or are suspected to be involved in the building of the glycosyl portion of GPLs [7,8,24,32].

Despite the increasingly recognized widespread presence of GPLs in mycobacteria and the relevance of these compounds in MAC and other mycobacteria of clinical significance, the GPL biosynthetic pathway remains incompletely understood. The individual involvement of several genes suspected to be required for GPL production remains to be experimentally probed. In particular, the involvement of a gene encoding a member of the MbtH-like protein family (NCBI CDD pfam 03621) [33,34] and clustered with the NRPS-encoding genes required for D-Phe-D-alloThr-D-Ala-L-alaninol assembly in GPL production has been hypothesized [23-25,35], but not conclusively demonstrated. MbtH-like proteins form a family of small proteins (60–80 amino acids) linked to secondary metabolite production pathways involving NRPSs [34]. The founding member of this protein family is MbtH, a protein encoded in the mycobactin siderophore biosynthetic gene cluster of M. tuberculosis[33].

Recent seminal biochemical studies have established that MbtH-like proteins activate amino acid adenylation domains of NRPSs [36-40]. Genes encoding MbtH-like proteins have been shown to be required for production of siderophores or antibiotics by mutational analysis [41-44]. Interestingly, however, we have recently shown by mutational analysis that the mbtH orthologue in the mycobactin biosynthetic gene cluster of Ms (MSMEG_4508) is not essential for mycobactin production [35]. Similarly, the mbtH-like gene in the biosynthetic gene cluster of the balhimycin glycopeptide antibiotic has been shown not to be required for antibiotic production [45]. These findings illustrate the well-recognized limitations of bioinformatics-based genetic predictions in complex biosynthetic pathways and highlight the need for probing gene involvement by unconfounded mutational analysis. In this study, we provide evidence unequivocally establishing that the conserved mbtH-like gene (herein referred to as gplH) located in the GPL biosynthetic gene locus of Ms is essential for GPL production. This finding presents the first case of a mbtH-like gene required for biosynthesis of a cell wall component and provides the first example of a mbtH-like gene with confirmed functional role in a member of the Mycobacterium genus. Moreover, we show that loss of gplH leads to a mutant with atypical colony morphology, lack of sliding motility, reduced biofilm formation capacity, and increased antimicrobial drug susceptibility. Altogether, this study demonstrates a critical role for gplH in mycobacterial biology and advances our understanding of the genetic requirements for the biosynthesis of an important group of constituents of the unique mycobacterial outer membrane.

Results and discussion

Conservation of a MbtH homologue in the GPL biosynthetic pathway

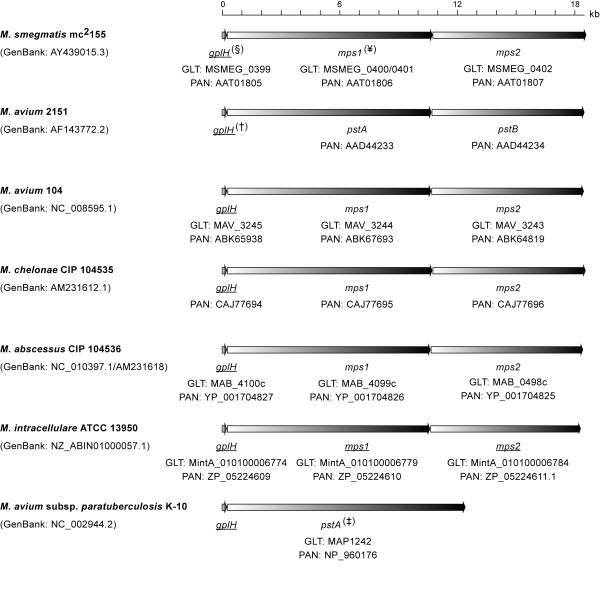

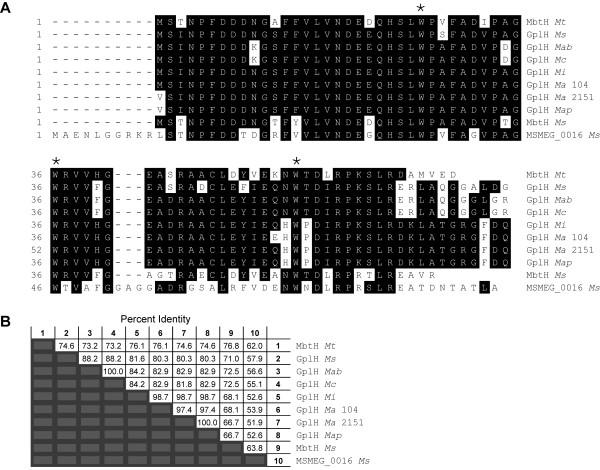

MbtH is a protein encoded in the mycobactin siderophore biosynthetic gene cluster of M. tuberculosis and the founding member of the MbtH-like protein family (NCBI CDD pfam 03621) [33]. Our analysis of available genome sequences of GPL producers revealed that every GPL biosynthetic gene cluster known to date contains a mbtH-like gene located upstream of NRPS-encoding genes required for D-Phe-D-alloThr-D-Ala-L-alaninol assembly (Figure 2). The MbtH-like protein orthologues encoded by these mbtH-like genes are comprised of 69–93 amino acids and have remarkable sequence identity (80-100%) (Figure 3). This sequence identity extends to the three fully conserved tryptophan residues that are a hallmark of the protein family (NCBI CDD pfam 03621) [33] (Figure 3A). The open reading frame corresponding to the mbtH-like gene of M. avium 2151 (Figure 2) has not been previously annotated; however, our genome sequence analysis revealed its presence. The MbtH-like protein encoded by this gene is shown in the protein alignment (Figure 3A). The orthologous mbtH-like genes or MbtH-like proteins in the other species shown in Figure 2 have been annotated each as mbtH or MbtH, respectively [24,46], presumably due to their sequence relatedness with M. tuberculosis MbtH. This name assignment is misleading as these genes are not orthologues of mbtH, the gene of the mycobactin biosynthetic pathway present in many mycobacteria, including M. smegmatis, M. abscessus, and M. avium[33,35]. This name assignment leads to gene nomenclature confusion by resulting in more than one gene named mbtH in the same species. We proposed herein to name all the orthologous mbtH-like genes associated with GPL production as gplH, a name derived from glycopeptidolipid and mbtH and not previously assigned to any mycobacterial gene.

Figure 2.

Orthologous mbtH-like gene (gplH)-nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene loci involved in GPL production.§ Nucleotide sequence accession numbers (GenBank) of analyzed sequences, protein accession numbers (PAN), available genomic locus tags (GLT), and gene names are shown. Underlined gene names are proposed herein. ¥M. smegmatis sequence submission AY439015.3 shows a single gene (mps1) where the annotated complete genome (GenBank: CP000480.1) shows two contiguous genes (MSMEG_0400 and MSMEG_0401). Our sequence comparison revealed that CP000480.1 has an insertion of a “C” and a deletion of an “A” relative to AY439015.3. The events (112-bp apart) create a transient frameshift that splits mps1 into MSMEG_0400 and MSMEG_0401. We resequenced the region containing the discrepancies and found that our sequence matched that of AY439015.3. Based on this and the conservation of mps1 across species, we conclude that the correct gene organization is as shown herein. †The open reading frame corresponding to this gene has not been previously annotated. ‡Our sequence analysis (not shown) indicates that the pstA appears to have originated from an mps1 and mps2 deletion-fusion rearrangement relative to the canonical mps1 and mps2 seen in M. avium strains 104 and 2151 and other GPL-producing species. This rearrangement leads to a gene encoding a 4,027-amino acid protein that appears to have segments derived from both Mps1 and Mps2. This protein would not be competent for D-Phe-D-alloThr-D-Ala-L-alaninol synthesis, a defect that alone would explain the known GPL-deficiency of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis K-10.

Figure 3.

Sequence relatedness of GplH orthologues and related homologues. (A) Protein alignment and (B) table of percentage of amino acid identity. Conserved amino acids that match consensus are highlighted in white font over black background. The three conserved tryptophan residues that are the hallmark of the MbtH-like protein family are marked (*). The protein alignment and identity determination were performed with ClustalW (Lasergene software, DNASTAR, Inc). Mab, M. abscessus; Ma, M. avium; Map, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis; Mc, M. chelonae; Mi, M. intracellulare; Ms, M. smegmatis; Mt, M. tuberculosis.

Deletion of gplH in M. smegmatis

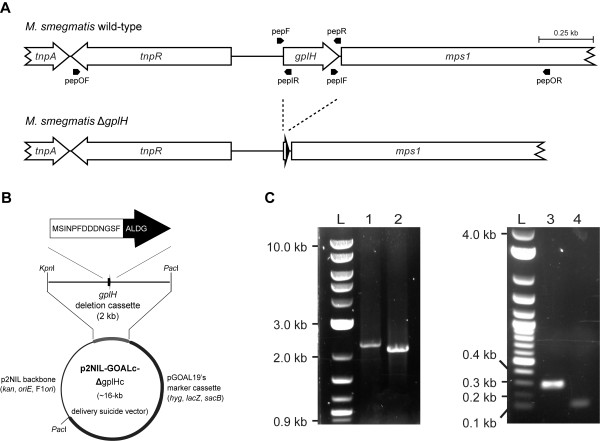

Our bioinformatics analysis revealed that every GPL biosynthetic gene cluster known to date contains a mbtH-like gene, gplH. The involvement of this conserved gene in GPL production remains unproven. Herein, we sought to conclusively establish whether gplH was required for GPL production. To this end, we engineered Ms ΔgplH, a mutant with an unmarked, in-frame deletion of gplH (Figure 4A), the Ms gene upstream of the NRPS-encoding gene mps1 (Figure 2), and assessed the ability of this mutant to produce GPLs as described below. Ms was selected as a representative prototype of GPL producers for the studies presented herein due to its superior experimental tractability compared with other GPL producers (e.g., MAC members).

Figure 4.

Construction of M. smegmatis ΔgplH. (A) Scheme illustrating the deletion in the chromosome of Ms ΔgplH. The position of each primer used in this study is shown. (B) Scheme of the gplH deletion cassette-delivery suicide vector used for construction of Ms ΔgplH. The gplH deletion leaves behind a gene remnant coding for only the first 13 (black print) and last 4 (white print) amino acids of GplH. This gene remnant in ΔgplHc is flanked by ~1 kb of downstream and upstream WT sequence for homologous recombination with the chromosome. (C) Agarose gel electrophoresis showing PCR-based confirmation of the gplH deletion in Ms ΔgplH. Lanes: 1, Ms WT (2,239-bp amplicon expected with primers pepOF and pepOR); 2, Ms ΔgplH (2,068-bp amplicon expected with primers pepOF and pepOR); 3, Ms WT (278-bp amplicon expected with primers pepF and pepR); 4, Ms ΔgplH (101-bp amplicon expected with primers pepF and pepR); L, DNA ladder marker.

The gplH deletion was engineered using the gplH deletion cassette-delivery suicide vector p2NIL-GOALc-ΔgplH c(~16 kb, Figure 4B) in a homologous recombination- and counter selection-based approach that replaced gplH by a 17-codon gene remnant cloned into the vector. The deletion in Ms ΔgplH encompassed 59 central amino acids of the predicted MbtH-like protein encoded by gplH (GplH, MSMEG_0399; 76 amino acids, Figure 3A). The deletion was verified by PCR using primer pairs that produced amplicons of different sizes depending on whether the genomic DNA used as PCR template was wild type (WT) or carried the gene deletion (Figure 4C). The successful engineering of Ms ΔgplH set the stage for probing the involvement of gplH in GPL production.

The gene gplH is essential for GPL production

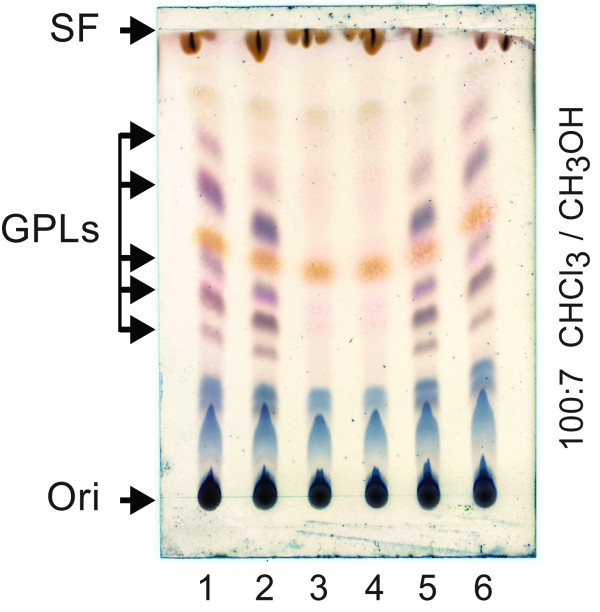

We investigated the effect of the gplH deletion in Ms ΔgplH on GPL production using TLC and MS analyses. In addition, a control strain for genetic complementation analysis was constructed (Ms ΔgplH + pCP0-gplH), and the ability of this strain and that of Ms WT controls to produce GPLs was investigated. Representative results from the TLC analysis are shown in Figure 5. The analysis of lipid extracts from the parental Ms WT strain, or Ms WT bearing the empty pCP0 vector, revealed the expected production of GPLs in these WT controls. Conversely, analysis of lipid extracts from Ms ΔgplH did not reveal detectable amounts of GPLs. Transformation of Ms ΔgplH with pCP0-gplH (a pCP0-based plasmid expressing gplH) rendered the strain Ms ΔgplH + pCP0-gplH, for which TLC analysis demonstrated that production of GPLs was restored to levels comparable to those seen in the WT controls. In contrast, Ms ΔgplH retained its GPL deficient phenotype after transformation with empty pCP0 vector (strain Ms ΔgplH + pCP0). The results of our complementation analysis rule out the possibility that the GPL deficient phenotype observed in Ms ΔgplH is due to a polar effect of the gplH deletion on downstream genes required for GPL production (i.e., mps1 and mps2; Figure 2).

Figure 5.

Deletion of gplH leads to GPL deficiency. Representative TLC analysis of lipid samples from: Ms WT; 2, Ms WT + pCP0; 3, Ms ΔgplH; 4, Ms ΔgplH + pCP0; 5, Ms ΔgplH + pCP0-gplH; and 6, Ms ΔgplH + pCP0-mbtHMs. The TLC solvent system is indicated. Ori, origin; SF, solvent front.

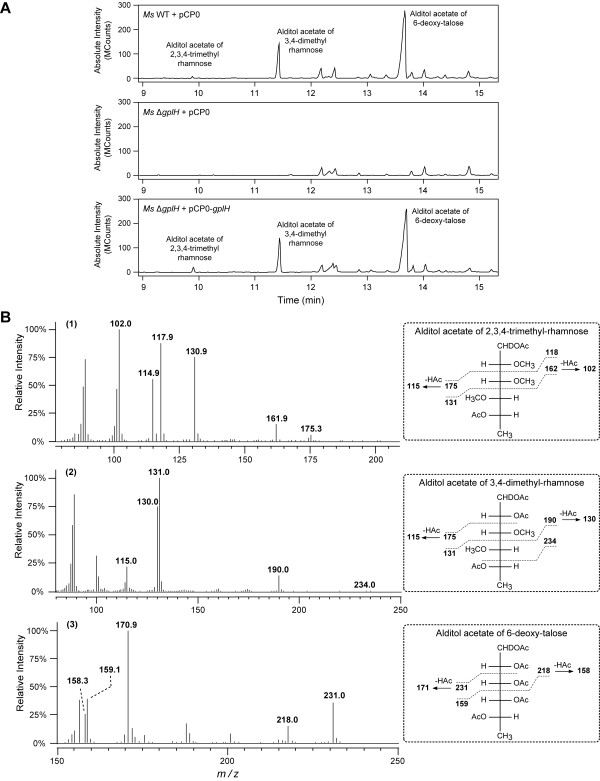

The presence of GPLs was probed for in lipid samples from Ms WT + pCP0, Ms ΔgplH + pCP0, and Ms ΔgplH + pCP0-gplH (complemented strain) by GC-MS analysis as well. The pCP0-bearing strains, Ms WT + pCP0 and Ms ΔgplH + pCP0, rather than their respective plasmid-free parental strains, were used in these experiments so that the WT, the mutant, and the complemented strain could all be cultured under identical conditions (i.e., kanamycin-containing growth medium) for comparative analysis by GC-MS. Representative results from the GC-MS analysis are shown in Figure 6. This analysis probed for the presence of the alditol acetate derivatives of the characteristic glycosyl residues of Ms GPLs as a fingerprint indicator of the presence of GPLs in the lipid samples analyzed [47]. The GC-MS analysis of samples from Ms WT + pCP0 revealed the expected m/z peak array consistent with the characteristic presence of alditol acetate derivatives of the 2,3,4-trimethyl-rhamnose, 3,4-dimethyl-rhamnose and 6-deoxy-talose components of GPLs [7,8,47]. Conversely, these alditol acetate derivatives were not detected by GC-MS analysis of samples from Ms ΔgplH + pCP0. The samples from the complemented strain, Ms ΔgplH + pCP0-gplH, displayed an m/z peak array comparable to that of Ms WT + pCP0 and consistent with the presence of the alditol acetate derivatives originating from GPLs (not shown). Overall, the results of the GC-MS analysis and the results of the TLC analysis are in agreement with each other and, coupled with our genetic complementation-controlled analysis, conclusively demonstrate that gplH is essential for production of GPLs.

Figure 6.

GC-MS analysis of alditol acetate derivatives of the glycosyl residues of GPLs. (A) Total ion count chromatographs displaying the presence or absence of alditol acetates in extracted lipid samples from the strains indicated. (B) Mass spectra showing fragmentation pattern fingerprints demonstrating alditol acetate identity in peaks labeled 2,3,4-trimethyl- rhamnose (1), 3,4-dimethyl-rhamnose (2), and 6-deoxy-talose (3) from Ms WT + pCP0. Equivalent spectra were observed for the samples of Ms ΔgplH + pCP0-gplH (not shown). The selective ion monitoring MS analysis of the mutant strain Ms ΔgplH revealed that the strain lacks the alditol acetate derivatives. For illustration clarity, only the m/z values of selected diagnostic molecular ions are indicated in the spectra. These molecular ions arise from the fragmentation patterns of the corresponding alditol acetates as displayed next to each spectrum.

Based on the recent elucidation of the function of MbtH-like proteins as amino acid adenylation domain activators [36-40], it is reasonable to propose that GplH is required for the assembly of the D-Phe-D-alloThr-D-Ala-L-alaninol core moiety of GPLs by the Mps1-Mps2 NRPS system. GplH might act as a critical activator of the amino acid adenylation activity of one or more of the four amino acid adenylation domains predicted by sequence analysis of the Mps1-Mps2 NRPS system [22,23]. Biochemical studies will be required to investigate this possibility.

MbtH-mediated cross-talk between GPL biosynthesis and mycobactin biosynthesis

We noted that Ms has two potential mbtH-like genes located outside the GPL biosynthetic gene cluster. One of these genes is the mbtH orthologue in the mycobactin biosynthetic gene cluster of Ms mentioned above [35]. The second gene, MSMEG_0016, is clustered with genes implicated in the production of the siderophore exochelin [48-50]. The protein products of these two Ms gplH paralogues have considerable amino acid sequence identity between themselves and with GplH and M. tuberculosis MbtH (Figure 3B). The GPL deficiency of Ms ΔgplH indicates that neither of these two Ms gplH paralogues can support the production of GPLs in Ms ΔgplH to a meaningful level under our culturing conditions.

It is worth noting that Ms mbtH and MSMEG_0016 are associated with siderophore production pathways known to be repressed during growth under iron-rich conditions [51,52]. This fact raises the possibility that neither of these genes is expressed (or they are poorly expressed) in the iron-rich standard Middlebrook media used in our studies. With this consideration in mind, we explored whether an increase in expression of Ms mbtH (encoding the paralogue with the higher homology to GplH, Figure 3) could complement the GPL deficiency of Ms ΔgplH. To this end, we evaluated GPL production in Ms ΔgplH after transformation of the mutant with pCP0-mbtHMs (expressing Ms mbtH). TLC analysis of lipid extracts from the transformant revealed the presence of GPLs, thus indicating that plasmid-directed constitutive expression of Ms mbtH complements the GPL deficient phenotype of Ms ΔgplH (Figure 5). Thus, it appears that Ms MbtH has the potential to functionally replace GplH if present in sufficient quantities. This cross-complementation phenomenon is in line with recent cell-based studies demonstrating MbtH-like protein-mediated cross-talk between NRPS systems [41,44]. Our finding is also consistent with reported in vitro enzymology indicating that, at least in some cases, the activity of amino acid adenylation domains of NRPSs can be stimulated not only by bona fide MbtH-like protein partners, but also by MbtH-like protein homologues from disparate natural product biosynthetic pathways [39,40].

Deletion of gplH leads to a pleiotropic phenotype

Colony morphotype, biofilm formation and sliding motility are properties that have been shown to be altered in GPL deficient mutants [18-20,23]. Loss of GPL also perturbs bacterial surface properties [19,32] and reduces the cell-wall permeability barrier to chenodeoxycholate uptake [19]. Interestingly, an altered profile of GPLs has been observed in drug-resistant MAC isolates [21]. This finding raises the possibility that GPL production might have an impact on antimicrobial drug susceptibility as well. We investigated whether deletion of gplH had an effect on all these properties. Ms WT + pCP0 and Ms ΔgplH + pCP0, rather than their respective plasmid-free parental strains, were used in the experiments so that the WT, the mutant, and the complemented Ms ΔgplH + pCP0-gplH strain could all be cultured under identical conditions (i.e., kanamycin-containing growth media) for comparative analysis. Representative results from these studies are shown in Figure 7.

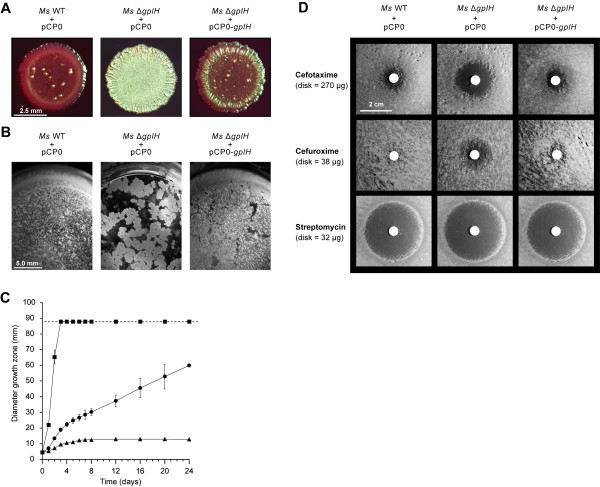

Figure 7.

Pleiotropic phenotype of M. smegmatis ΔgplH. (A) Morphotype on the congo red agar plate assay. (B) Formation of biofilm at the liquid-air interface. (C) Sliding motility analysis. (▄) Ms WT + pCP0, (●) Ms ΔgplH + pCP0-gplH, (▲) Ms ΔgplH + pCP0. Data points are means of duplicates ± SEM. The dashed line marks the diameter of the agar plate. (D) Antimicrobial drug susceptibility. Results shown are representative of four determinations.

Ms is known to develop into smooth, reddish colonies with a glossy and translucent appearance when grown on low carbon source congo red agar plates [23]. As expected, Ms WT + pCP0 displayed this characteristic morphotype in our congo red agar plate assay (Figure 7A). Ms ΔgplH + pCP0, however, had a drastically different morphotype. The mutant was characterized by rough, whitish colonies with a non-translucent and dried appearance. The strain Ms ΔgplH + pCP0-gplH had a morphotype more similar to WT than to that of the mutant, indicating partial complementation by episomal expression of gplH in the congo red agar assay. Deletion of gplH also altered the ability of Ms to form biofilms (Figure 7B). Ms WT + pCP0 formed a continuous, thin biofilm at the liquid-air interface, as expected based on previous reports [53,54]. In contrast, Ms ΔgplH + pCP0 failed to develop such a biofilm and instead grew as chunky patches on the liquid surface. The strain Ms ΔgplH + pCP0-gplH produced biofilms comparable to those seen with Ms WT + pCP0. Sliding motility was also compromised in Ms ΔgplH + pCP0 (Figure 7C). The mutant did not show sliding motility, whereas Ms WT + pCP0 was highly active in the motility assay. Ms ΔgplH + pCP0-gplH also displayed sliding motility, although the motility was somewhat reduced compared to WT. This observation indicates partial complementation by episomal expression of gplH. Overall, these results clearly indicate that deletion of gplH has a profound impact on colony morphotype, biofilm formation, and sliding motility. These mutant phenotypes have previously been associated with other GPL deficient strains and attributed to alterations of the properties of the cell surface due to lack of GPLs. Thus, it is likely that the phenotypes observed in the gplH mutant arise from its GPL deficiency.

In contrast to the drastic impact of the gplH deletion on colony morphotype, biofilm formation and sliding motility, lack of gplH had a relatively minor effect on antimicrobial drug susceptibility. When compared with Ms WT + pCP0 (control strain), Ms ΔgplH + pCP0 showed a slight, yet consistent, increase in susceptibility to only two drugs (cefuroxime and cefotaxime) from a panel of 15 drugs of different classes tested in standard disk diffusion assays.

Interestingly, these two drugs belong to the cephalosporin class, suggesting that the hypersusceptibility of the mutant is antibiotic-class dependent. Representative results illustrating the hypersusceptibility of the mutant to these cephalosporins are shown in Figure 7D.

Streptomycin susceptibility results are also shown in Figure 7D. The streptomycin susceptibility is presented as an example of those drugs to which the mutant had no meaningful difference in susceptibility relative to the WT control. The Ms ΔgplH + pCP0-gplH strain showed a drug susceptibility pattern similar to that of Ms WT + pCP0, indicating that the hypersusceptible phenotype of the mutant was complemented by episomal expression of gplH.

The molecular mechanism behind the cephalosporin hypersusceptibility arising from the lack of gplH remains obscure. It is generally believed that the permeability barrier imposed by the mycobacterial outer membrane reduces antibiotic susceptibility by decreasing compound penetration. Thus, it is tempting to hypothesize that the observed cephalosporin hypersusceptibility arises from an alteration in the permeability barrier of the outer membrane of the gplH mutant due to the lack of GPLs. The observation that lack of GPLs correlates with a reduction in the permeability barrier to chenodeoxycholate uptake [19] is in line with this hypothesis. The absence of GPLs might produce structural or fluidity changes in the membrane that lead to an increase in cephalosporin penetration. The fact that Ms ΔgplH displays only a modest increase in antibiotic susceptibility suggests, however, that the lack of GPLs in the outer membrane of the mutant does not have a profound effect on the permeability barrier that this cell envelope structure presents to drug penetration. Thus, our results support the view that GPLs are not critical contributors to the physical integrity of the permeability barrier of the mycobacterial cell envelope.

Conclusions

Our results unambiguously demonstrate that the conserved gene gplH is required for GPL production and its inactivation leads to a pleiotropic phenotype. While genes encoding members of the MbtH-like protein family have been shown to be required for production of siderophores or antibiotics [41-44], our findings present the first case of one such gene required for biosynthesis of a cell wall component. Furthermore, gplH is the first mbtH-like gene with proven functional role in a member of the Mycobacterium genus. Altogether, this study formally demonstrates a critical role for gplH in mycobacterial biology and advances our understanding of the genetic requirements for the biosynthesis of an important group of constituents of the unique mycobacterial outer membrane.

Methods

Culturing conditions and recombinant DNA manipulations

Ms strain mc2155 (ATCC 700084) and its derivatives were routinely cultured under standard conditions (37°C, 225 rpm) in Middlebrook 7H9 (Difco) supplemented with 10% ADN (5% BSA, 2% dextrose, 0.85% NaCl), 0.2% glycerol and 0.05% Tween-80 (supplemented 7H9) or in Middlebrook 7H11 (Difco) supplemented with 10% ADN (supplemented 7H11) [55]. E. coli DH5α (Invitrogen) was cultured under standard conditions in Luria-Bertani media [56]. When required, kanamycin (30 μg/ml), hygromycin (50 μg/ml), sucrose (2%) and/or X-gal (70 μg/ml) were added to the media. General recombinant DNA manipulations were carried out by standard methods and using E. coli as the primary cloning host [56]. Molecular biology reagents were obtained from Sigma, Invitrogen, New England Biolabs, Novagen, QIAGEN, or Stratagene. Oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. PCR-generated DNA fragments used in plasmid constructions were sequenced to verify fidelity. Chromosomal DNA isolation from and plasmid electroporation into mycobacteria were carried out as reported [55]. Table 1 lists the plasmids and oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

Table 1.

Plasmids and oligonucleotide primers

| Plasmid | Characteristics | Source or Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pCR2.1-TOPO |

Cloning vector, kanamycin resistance and ampicillin resistance genes |

Invitrogen |

| pCP0 |

Vector for gene expression in mycobacteria, kanamycin resistance gene |

[4] |

| pCP0-gplH |

pCP0 expressing M. smegmatis gplH |

This study |

| pCP0-mbtHMs |

pCP0 expressing M. smegmatis mbtH (MSMEG_4508) |

[35] |

| p2NIL |

Kanamycin resistance gene and OriE |

[57] |

| pGOAL19 |

Hygromycin resistance gene, sacB-lacZ PacI cassette, and OriE |

[57] |

| p2NIL-GOALc-ΔgplHc |

Delivery vector carrying a gplH deletion cassette (ΔgplHc) |

This study |

|

Oligonucleotide |

Sequence (5’ to 3’) |

Characteristics |

| pepOF |

GGTACCTGTTCAACGCGGCCAGAGCGTCATTGGTCTCGGCCA |

KpnI |

| pepOR |

TTAATTAATGTTGCAACAGCTCCCTGATCCGGATGTCGACGTGCTTG |

PacI |

| pepIR |

TCAGCCGTCAAGAGCAAAGCTGCCGTTGTCGTCATCGAACGGGTTGAT |

SOE PCR |

| pepIF |

CGACAACGGCAGCTTTGCTCTTGACGGCTGAGTCAAATAGTCTGTTG |

SOE PCR |

| pepF |

CTGCAGTGAACAGCCGGGAGAAACGT |

PstI |

| pepR | AAGCTTCCCAACAGACTATTTGACTCAGCCG | HindIII |

Construction of M. smegmatis ΔgplH

Ms ΔgplH was engineered using the p2NIL/pGOAL19-based flexible cassette method [57] as previously reported [4,31,35,58]. A suicide delivery vector (p2NIL-GOALc-ΔgplHc, see below) carrying a gplH (MSMEG_0399) deletion cassette (ΔgplHc) was used to generate Ms ΔgplH. The vector was electroporated into Ms and transformants with a potential p2NIL-GOALc-ΔgplHc integration via a single-crossover event (blue colonies) were selected on supplemented 7H11 containing hygromycin, kanamycin, and X-gal. The selected transformants were then grown in antibiotic-free supplemented 7H9, and subsequently plated for single colonies on supplemented 7H11 containing sucrose and X-gal. White colonies that grew on the sucrose plates were re-streaked onto antibiotic-free and antibiotic-containing supplemented 7H11 plates to identify clones that lost drug resistance, a trait indicating a possible double-crossover event with consequent loss of gplH or reversion to WT. The deletion of gplH in antibiotic sensitive clones was screened for and confirmed by PCR. Towards this end, chromosomal DNA isolated from mutant candidates was used as template along with primer pairs (pepOF and pepOR, pepF and pepR) that produced diagnostic amplicons permitting differentiation between the mutant and WT genotypes.

Construction of p2NIL-GOALc-ΔgplHc and pCP0-gplH

The plasmid p2NIL-GOALc-ΔgplHc used in the construction of Ms ΔgplH carried the gplH deletion cassette ΔgplHc. The deletion cassette contained: 995-bp segment upstream of gplH + gplH’s first 13 codons (5 fragment) followed by gplH’s last 4 codons + stop codon + 1,000-bp segment downstream of gplH (3 fragment). ΔgplHc was built by the joining of the 5' fragment and the 3' fragment using splicing-by-overlap-extension (SOE) PCR [59]. Each fragment was PCR-generated from chromosomal DNA. Primer pair pepOF and pepIR and primer pair pepIF and pepOR were used to generate the 5’ and 3’ fragments, respectively. The fragments were then used as template for PCR with primers pepOF and pepOR to fuse the fragments and create ΔgplHc (2,061 bp). The PCR-generated ΔgplHc was first cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen). ΔgplHc was subsequently excised from the pCR2.1-TOPO construct using KpnI and PacI, and the excerpt was ligated to p2NIL [57] linearized by KpnI-PacI digestion. The resulting p2NIL-ΔgplHc plasmid and plasmid pGOAL19 [57] were digested with PacI, and the PacI cassette (GOALc, 7,939 bp) of pGOAL19 was ligated to the linearized p2NIL-ΔgplHc to create p2NIL-GOALc-ΔgplHc. To create pCP0-gplH, the plasmid used for complementation analysis, a DNA fragment (266 bp) encompassing gplH and its predicted ribosome binding site (RBS) was PCR-amplified from genomic DNA with primer pair pepF and pepR and cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO. The RBS-gplH fragment was subsequently excised from the pCR2.1-TOPO construct using PstI and HindIII and ligated to plasmid pCP0 [4] linearized by PstI-HindIII digestion to create pCP0-gplH. The cloning placed gplH under the control of the hsp60 promoter of pCP0 for gene expression in mycobacteria.

Extraction and thin layer chromatography (TLC) analysis of GPLs

GPLs were extracted and analyzed by TLC by reported methods [22,60]. Cells from cultures (5 ml, OD600 of 1.3-1.6) grown in supplemented 7H9 as described above were collected by centrifugation (4,700 × g, 15 min), washed with cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 1 ml), and processed for GPL extraction. GPLs were extacted with 2:1 CHCl3/CH3OH (20 μl/mg wet weight) by incubation overnight at room temperature in a rocking shaker. After incubation, insoluble material was removed by centrifugation (18,400 × g, 10 min), and the CHCl3/CH3OH supernatant was recovered and mixed with 0.2 volumes of 0.9% NaCl. After vigorous vortexing, the mixture was centrifuged (1,150 × g, 5 min) and the organic phase (containing GPLs) was collected and evaporated to dryness. The dried lipid extracts were dissolved in 20 μl of CHCl3/CH3OH (2:1) and subjected to TLC using aluminum-backed, 250-μm silica gel F254 plates developed with CHCl3/CH3OH (100:7). After chromatography, TLC plates were sprayed with orcinol/sulfuric acid (0.1% orcinol in 40% sulfuric acid) and glycolipids were detected by charring at 140°C.

Preparation and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis of alditol acetate derivatives

Alditol acetate derivatives of glycosyl units from GPLs were prepared and analyzed as reported [47,61]. Briefly, lipid samples prepared by extraction as noted above were acid-hydrolyzed in 250 μl of 2 M trifluoroacetic acid for 2 hr at 120°C. After cooling down to room temperature, samples were hexane-washed (250 μl) and dried on air bath after adding 1 μg of 3,6-O-dimethyl-glucose as an internal standard. The hydrolyzed sugars were reduced overnight at room temperature by adding 250 μl of NaBD4 (prepared at 10 mg/ml in 1 M NH4OH in C2H5OH). After reduction, glacial acetic acid (20 μl) was added to remove excess NaBD4 and the samples were dried. CH3OH (100 μl) was added to each sample, and after resuspension the solvent was evaporated to dryness (this step was repeated twice). The samples were per-O-acetylated with 100 μl of acetic anhydride at 120°C for 2 hr. After cooling, the samples were dried on air bath and suspended in 3 ml of CHCl3/H2O (2:1) by vortexing. The organic layer was extracted after centrifugation (2,500 × g, 5 min, 4°C) and dried on air bath. GC-MS analysis was performed using a Varian CP-3800 gas chromatograph (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA) equipped with a MS-320 mass spectrometer and using helium gas. The alditol acetate derivatives were dissolved in 50 μl of CHCl3 before injection on a DB 5 column (30 m × 0.20 mm inner diameter) with an initial oven temperature of 50°C for 1 min, followed by an increase of 30°C/min to 150°C and finally to 275°C at 5°C/min.

Congo red agar plate assay

The assay was carried out using reported methodologies [23]. Briefly, mycobacterial cultures (5 ml, OD600 = 1.5) were shortly vortexed with glass beads to increase homogeneity and then centrifuged (4,700 × g, 15 min) for cell collection. The collected cells were washed with PBS (5 ml) and subsequently resuspended in PBS to an OD600 of 1. The cell suspensions were spotted (2 μl) on congo red agar plates [23] (7H9 basal medium, 1.5% agar, 100 μg/ml congo red (sodium salt of 3,3'-([1,1'-biphenyl]-4,4'-diyl)bis(4-aminonaphthalene-1-sulfonic acid), Sigma Aldrich Co.), 0.02% glucose, 30 μg/ml kanamycin). Colony morphology was examined using an Olympus SZX7 stereo microscope after plate incubation (37°C, 3 days).

Sliding motility test

The test was performed by standard methods [19]. Briefly, mycobacterial cell suspensions in PBS prepared as noted above were spotted (2 μl) on sliding motility assay plates [19] (7H9 basal medium, 0.3% agarose, 30 μg/ml kanamycin). The sliding motility plates were incubated at 37°C and the degree of spreading (diameter of growth zone) was determined at the time points indicated in results.

Biofilm formation assay

The liquid-air interface biofilm assay was conducted based on reported methods [53]. Overnight mycobacterial cultures (5 ml) grown in supplemented 7H9 as noted above were centrifuged (4,700 × g, 15 min) for cell collection. The cells were washed twice with 5 ml of supplemented 7H9 without Tween-80. After washing, the cells were resuspended in supplemented 7H9 without Tween-80 to a calculated OD600 of 10. A 25 μl aliquot of each suspension was inoculated onto the surface of 2.5 ml of supplemented 7H9 without Tween-80 loaded into a well of a 12-well polystyrene plate. The plate was incubated for 4 days without shaking at 37°C before examination for biofilm formation.

Drug susceptibility assay

Standard disk-diffusion assays were carried out as reported [58,62]. Exponentially growing cultures (OD600 = 0.6) in supplemented 7H9 were diluted in fresh medium to an OD600 of 0.05, and 100 μl of diluted culture were used to seed 7H11 plates (20 ml agar/plate). Antibiotic disks were placed onto the inoculated agar and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 days before analysis. The antibiotics tested were doxycycline, isoniazid, streptomycin, tetracycline, cefuroxime, erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ethambutol, ethionamide, rifampicin, clarithromycin, cefuroxime, cephalexin, and cefotaxime. The antibiotics were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich, Fisher Scientific, Tokyo Chemical Industry, or Calbiochem Biochemicals.

Abbreviations

GC-MS: Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry; GPL: Glycopeptidolipid; MAC: Mycobacterium avium-Mycobacterium intracellulare complex; Ms: Mycobacterium smegmatis; NRPS: Nonribosomal peptide synthetase; PBS: Phosphate buffered saline; PKS: Polyketide synthetase; TLC: Thin layer chromatography.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LQ conceived the study. ET, SC, PM, UE and SA carried out the experiments. LQ, ET, SC, and DC analyzed results and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Tatham, Email: etatham@optonline.net.

Sivagami sundaram Chavadi, Email: Chavadi@brooklyn.cuny.edu.

Poornima Mohandas, Email: pmohandas@gc.cuny.edu.

Uthamaphani R Edupuganti, Email: Uthama@brooklyn.cuny.edu.

Shiva K Angala, Email: Shiva.Angala@ColoState.edu.

Delphi Chatterjee, Email: Delphi.Chatterjee@colostate.edu.

Luis E N Quadri, Email: LQuadri@brooklyn.cuny.edu.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH Grant R01AI075092 to LQ and NIH Grant RO1 AI37139 to DC. LQ acknowledges the endowment support from Carol and Larry Zicklin.

References

- Brennan PJ, Nikaido H. The envelope of mycobacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:29–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick DC, Quadri LE, Brennan PJ. In: Handbook of Tuberculosis: Molecular Biology and Biochemistry. Kaufmann SHE, Weinheim RR, editor. KgaA: WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co; 2008. Biochemistry of the cell envelope of Mycobacterium tuberculosis; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Onwueme KC, Vos CJ, Zurita J, Ferreras JA, Quadri LE. The dimycocerosate ester polyketide virulence factors of mycobacteria. Prog Lipid Res. 2005;44:259–302. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreras JA, Stirrett KL, Lu X, Ryu JS, Soll CE, Tan DS, Quadri LE. Mycobacterial phenolic glycolipid virulence factor biosynthesis: mechanism and small-molecule inhibition of polyketide chain initiation. Chem Biol. 2008;15:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreras JA, Ryu JS, Di Lello F, Tan DS, Quadri LE. Small-molecule inhibition of siderophore biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Yersinia pestis. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:29–32. doi: 10.1038/nchembio706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadri LEN. Strategic paradigm shifts in the antimicrobial drug discovery process of the 21st century. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:230–237. doi: 10.2174/187152607782110040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee D, Khoo KH. The surface glycopeptidolipids of mycobacteria: structures and biological properties. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:2018–2042. doi: 10.1007/PL00000834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorey JS, Sweet L. The mycobacterial glycopeptidolipids: structure, function, and their role in pathogenesis. Glycobiology. 2008;18:832–841. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field SK, Fisher D, Cowie RL. Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease in patients without HIV infection. Chest. 2004;126:566–581. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.2.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marras TK, Daley CL. Epidemiology of human pulmonary infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23:553–567. doi: 10.1016/S0272-5231(02)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades ER, Archambault AS, Greendyke R, Hsu FF, Streeter C, Byrd TF. Mycobacterium abscessus Glycopeptidolipids mask underlying cell wall phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides blocking induction of human macrophage TNF-alpha by preventing interaction with TLR2. J Immunol. 2009;183:1997–2007. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada K, Takimoto H, Yano I, Kumazawa Y. Involvement of mannose receptor in glycopeptidolipid-mediated inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion. Microbiol Immunol. 2006;50:243–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2006.tb03782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano H, Doi T, Fujita Y, Takimoto H, Yano I, Kumazawa Y. Serotype-specific modulation of human monocyte functions by glycopeptidolipid (GPL) isolated from Mycobacterium avium complex. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:335–339. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve C, Etienne G, Abadie V, Montrozier H, Bordier C, Laval F, Daffe M, Maridonneau-Parini I, Astarie-Dequeker C. Surface-exposed glycopeptidolipids of Mycobacterium smegmatis specifically inhibit the phagocytosis of mycobacteria by human macrophages. Identification of a novel family of glycopeptidolipids. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:51291–51300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve C, Gilleron M, Maridonneau-Parini I, Daffe M, Astarie-Dequeker C, Etienne G. Mycobacteria use their surface-exposed glycolipids to infect human macrophages through a receptor-dependent process. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:475–483. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400308-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow WW, Davis TL, Wright EL, Labrousse V, Bachelet M, Rastogi N. Immunomodulatory spectrum of lipids associated with Mycobacterium avium serovar 8. Infect Immun. 1995;63:126–133. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.126-133.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet L, Singh PP, Azad AK, Rajaram MV, Schlesinger LS, Schorey JS. Mannose receptor-dependent delay in phagosome maturation by Mycobacterium avium glycopeptidolipids. Infect Immun. 2010;78:518–526. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00257-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recht J, Martinez A, Torello S, Kolter R. Genetic analysis of sliding motility in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4348–4351. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.15.4348-4351.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne G, Villeneuve C, Billman-Jacobe H, Astarie-Dequeker C, Dupont MA, Daffe M. The impact of the absence of glycopeptidolipids on the ultrastructure, cell surface and cell wall properties, and phagocytosis of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microbiology. 2002;148:3089–3100. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocincova D, Singh AK, Beretti JL, Ren H, Euphrasie D, Liu J, Daffe M, Etienne G, Reyrat JM. Spontaneous transposition of IS1096 or ISMsm3 leads to glycopeptidolipid overproduction and affects surface properties in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2008;88:390–398. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo KH, Jarboe E, Barker A, Torrelles J, Kuo CW, Chatterjee D. Altered expression profile of the surface glycopeptidolipids in drug-resistant clinical isolates of Mycobacterium avium complex. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9778–9785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billman-Jacobe H, McConville MJ, Haites RE, Kovacevic S, Coppel RL. Identification of a peptide synthetase involved in the biosynthesis of glycopeptidolipids of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1244–1253. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonden B, Kocincova D, Deshayes C, Euphrasie D, Rhayat L, Laval F, Frehel C, Daffe M, Etienne G, Reyrat JM. Gap, a mycobacterial specific integral membrane protein, is required for glycolipid transport to the cell surface. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:426–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripoll F, Deshayes C, Pasek S, Laval F, Beretti JL, Biet F, Risler JL, Daffe M, Etienne G, Gaillard JL, Reyrat JM. Genomics of glycopeptidolipid biosynthesis in Mycobacterium abscessus and M. chelonae. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Kriakov J, Singh A, Jacobs WR Jr, Besra GS, Bhatt A. Defects in glycopeptidolipid biosynthesis confer phage I3 resistance in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microbiology. 2009;155:4050–4057. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.033209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh CT. Polyketide and nonribosomal peptide antibiotics: modularity and versatility. Science. 2004;303:1805–1810. doi: 10.1126/science.1094318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Assembly-line enzymology for polyketide and nonribosomal Peptide antibiotics: logic, machinery, and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3468–3496. doi: 10.1021/cr0503097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosa JH, Walsh CT. Genetics and assembly line enzymology of siderophore biosynthesis in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:223–249. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.2.223-249.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadri LE. Assembly of aryl-capped siderophores by modular peptide synthetases and polyketide synthases. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buglino J, Onwueme KC, Ferreras JA, Quadri LE, Lima CD. Crystal structure of PapA5, a phthiocerol dimycocerosyl transferase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30634–30642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onwueme KC, Ferreras JA, Buglino J, Lima CD, Quadri LE. Mycobacterial polyketide-associated proteins are acyltransferases: Poof of principle with Mycobacterium tuberculosis PapA5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4608–4613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306928101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshayes C, Laval F, Montrozier H, Daffe M, Etienne G, Reyrat JM. A glycosyltransferase involved in biosynthesis of triglycosylated glycopeptidolipids in Mycobacterium smegmatis: impact on surface properties. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:7283–7291. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7283-7291.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadri LE, Sello J, Keating TA, Weinreb PH, Walsh CT. Identification of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene cluster encoding the biosynthetic enzymes for assembly of the virulence-conferring siderophore mycobactin. Chem Biol. 1998;5:631–645. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(98)90291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltz RH. Function of MbtH homologs in nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis and applications in secondary metabolite discovery. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;38:1747–1760. doi: 10.1007/s10295-011-1022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavadi SS, Stirrett KL, Edupuganti UR, Sadhanandan G, Vergnolle O, Schumacher E, Martin C, Qiu WG, Soll CE, Quadri LEN. Mutational and phylogenetic analyses of the mycobacterial mbt gene cluster. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:5905–5913. doi: 10.1128/JB.05811-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heemstra JR Jr, Walsh CT, Sattely ES. Enzymatic tailoring of ornithine in the biosynthesis of the Rhizobium cyclic trihydroxamate siderophore vicibactin. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15317–15329. doi: 10.1021/ja9056008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imker HJ, Krahn D, Clerc J, Kaiser M, Walsh CT. N-acylation during glidobactin biosynthesis by the tridomain nonribosomal peptide synthetase module GlbF. Chem Biol. 2010;17:1077–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felnagle EA, Barkei JJ, Park H, Podevels AM, McMahon MD, Drott DW, Thomas MG. MbtH-like proteins as integral components of bacterial nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Biochemistry. 2010;49:8815–8817. doi: 10.1021/bi1012854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Heemstra JR Jr, Walsh CT, Imker HJ. Activation of the pacidamycin PacL adenylation domain by MbtH-like proteins. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9946–9947. doi: 10.1021/bi101539b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boll B, Taubitz T, Heide L. Role of MbtH-like proteins in the adenylation of tyrosine during aminocoumarin and vancomycin biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:36281–36290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.288092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautru S, Oves-Costales D, Pernodet JL, Challis GL. MbtH-like protein-mediated cross-talk between non-ribosomal peptide antibiotic and siderophore biosynthetic pathways in Streptomyces coelicolor M145. Microbiology. 2007;153:1405–1412. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/003145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake EJ, Cao J, Qu J, Shah MB, Straubinger RM, Gulick AM. The 1.8 Å crystal structure of PA2412, an MbtH-like protein from the pyoverdine cluster of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20425–20434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611833200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RA, Worsley PS, Sawers G, Challis GL, Dilworth MJ, Carson KC, Lawrence JA, Wexler M, Johnston AW, Yeoman KH. The vbs genes that direct synthesis of the siderophore vicibactin in Rhizobium leguminosarum: their expression in other genera requires ECF sigma factor RpoI. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44:1153–1166. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert M, Gust B, Kammerer B, Heide L. Effects of deletions of mbtH-like genes on clorobiocin biosynthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor. Microbiology. 2007;153:1413–1423. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/002998-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegmann E, Rausch C, Stockert S, Burkert D, Wohlleben W. The small MbtH-like protein encoded by an internal gene of the balhimycin biosynthetic gene cluster is not required for glycopeptide production. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;262:85–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biet F, Bay S, Thibault VC, Euphrasie D, Grayon M, Ganneau C, Lanotte P, Daffe M, Gokhale R, Etienne G, Reyrat JM. Lipopentapeptide induces a strong host humoral response and distinguishes Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis from M. avium subsp. avium. Vaccine. 2008;26:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil M, Chatterjee D, Hunter SW, Brennan PJ. Mycobacterial glycolipids: isolation, structures, antigenicity, and synthesis of neoantigens. Methods Enzymol. 1989;179:215–242. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)79123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiss EH, Yu S, Jacobs WR Jr. Identification of genes involved in the sequestration of iron in mycobacteria: the ferric exochelin biosynthetic and uptake pathways. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:557–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb02189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Fiss E, Jacobs WR Jr. Analysis of the exochelin locus in Mycobacterium smegmatis: biosynthesis genes have homology with genes of the peptide synthetase family. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4676–4685. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4676-4685.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Arceneaux JE, Beggs ML, Byers BR, Eisenach KD, Lundrigan MD. Exochelin genes in Mycobacterium smegmatis: identification of an ABC transporter and two non-ribosomal peptide synthetase genes. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:629–639. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadri LEN, Ratledge C. In: Tuberculosis and the Tubercle Bacillus. Cole ST, Eisenach KD, McMurray DN, Jacobs WRJ, editor. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2005. Iron metabolism in the tubercle bacillus and other mycobacteria; pp. 341–357. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez GM, Smith I. Mechanisms of iron regulation in mycobacteria: role in physiology and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:1485–1494. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojha A, Hatfull GF. The role of iron in Mycobacterium smegmatis biofilm formation: the exochelin siderophore is essential in limiting iron conditions for biofilm formation but not for planktonic growth. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:468–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojha A, Anand M, Bhatt A, Kremer L, Jacobs WR Jr, Hatfull GF. GroEL1: a dedicated chaperone involved in mycolic acid biosynthesis during biofilm formation in mycobacteria. Cell. 2005;123:861–873. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish T, Stoker NG, editor. Mycobacteria protocols. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. Third Edition. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Parish T, Stoker NG. Use of a flexible cassette method to generate a double unmarked Mycobacterium tuberculosis tlyA plcABC mutant by gene replacement. Microbiology. 2000;146:1969–1975. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-8-1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavadi SS, Edupuganti UR, Vergnolle O, Fatima I, Singh SM, Soll CE, Quadri LE. Inactivation of tesA reduces cell wall lipid production and increases drug susceptibility in mycobacteria. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:24616–24625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.247601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton RM, Hunt HD, Ho SN, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene. 1989;77:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein TM, Silbaq FS, Chatterjee D, Kelly NJ, Brennan PJ, Belisle JT. Identification and recombinant expression of a Mycobacterium avium rhamnosyltransferase gene (rtfA) involved in glycopeptidolipid biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5567–5573. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5567-5573.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma M, Zurita J, Ferreras JA, Worgall S, Larone DH, Shi L, Campagne F, Quadri LE. Pseudomonas aeruginosa SoxR does not conform to the archetypal paradigm for SoxR-dependent regulation of the bacterial oxidative stress adaptive response. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2958–2966. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2958-2966.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]