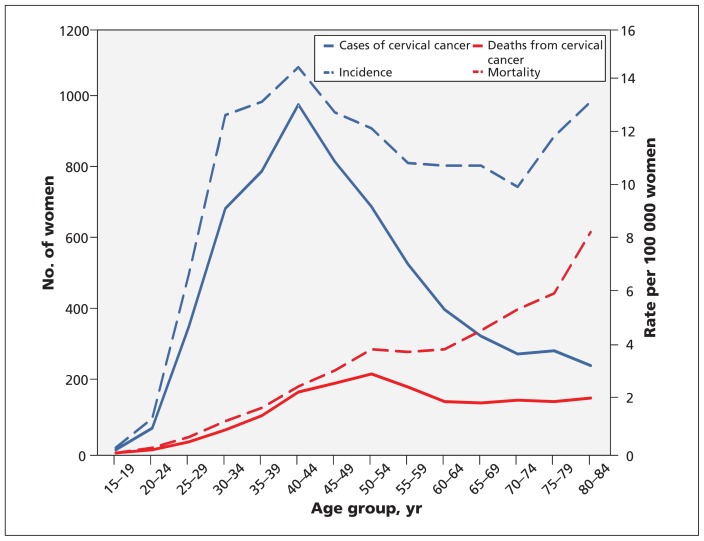

In 2011, an estimated 1300 new cases of cervical cancer were diagnosed in Canada, with about 350 deaths.1 The number of cases of diagnosed cervical cancer increases among women aged 25 years and older, peaking during the fifth decade of life (Figure 1). The incidence of and mortality due to cervical cancer in Canada have decreased substantially in the past 50 years,2,3 and long-term survival rates after treatment are high. Lifetime incidence was 1.5% in 1972, and is now 0.7%; risk of death from cervical cancer is now 0.2%.3 Most advanced cervical cancer (and associated mortality) occurs among women who have never undergone screening or who have had a long interval between Papanicolaou (Pap) tests.2

Figure 1:

Cases of and deaths from cervical cancer, with associated incidence and mortality (rates per 100 000 women), among Canadian women (2002–2006) by age group. Data are from the Canadian Cancer Registry and the vital statistics databases at Statistics Canada.

Screening for cervival cancer using the Pap test detects precursor lesions, thereby allowing earlier and potentially less invasive treatment than is required for disease that causes symptoms. The benefits of such screening on the incidence of invasive disease4 and death due to cervical cancer5 have been consistently shown in cohort and case–control studies.6

It is likely that much of the change seen in the incidence of cervical cancer in Canada is due to screening, but early and frequent (often annual) cervical screening is unnecessary: other countries have achieved similar outcomes with less frequent testing and starting screening at older ages.7 The similar levels of success with different approaches highlights uncertainties regarding the best ages at which to start and stop screening, screening intervals and screening methods. Furthermore, the benefits of screening must be balanced against its potential harms, such as additional follow-up tests for abnormal results and unnecessary treatment (e.g., owing to false-positives and overdiagnosis).

The likelihood of abnormal Pap test results is highest for young women, and decreases with increasing age.8 Because the prevalence of high-grade abnormalities declines steadily with age, although the incidence of cancer is higher, the proportion of abnormal results that represent serious abnormalities is greater among older women.8

Women whose initial Pap test result is abnormal may be asked to undergo a repeat test or have a colposcopy. The colposcopist may then biopsy the cervix. If the biopsy shows cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, the colposcopist may then treat the cervix by excising the transformation zone using various methods. These procedures cause short-term pain, bleeding and discharge,9 and may cause early loss of future pregnancies or premature labour.10 It is likely that many of these procedures can be considered overtreatment,11 because fewer than one-third of even high-grade abnormalities progress to cancer.12–14

This guideline provides updated recommendations for screening for cervical cancer in Canada based on new information about the epidemiology and diagnosis of cervical cancer and a new systematic search of the literature.11 This guideline updates the recommendations of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care that were last revised in 1994.15

Recommendations are presented for the use of Pap tests for women with no symptoms of cervical cancer who are or who have been sexually active, regardless of sexual orientation. Separate recommendations are provided for screening in women in the following age categories: younger than 20 years, 20–24 years, 25–29 years, 30–69 years and 70 years or older. Recommendations do not apply to women with symptoms of cervical cancer or previous abnormal test results on cervical screening (unless they have been cleared to resume normal screening); to women who have had complete surgical removal of the cervix; to women who are immunosuppressed by HIV, organ transplantation, chemotherapy or chronic use of corticosteroids; or to women who have limited life expectancy such that they would not benefit from screening. The recommendations do not address the management of abnormal test results or cervical cancer. Furthermore, they do not address screening through testing for human papilloma virus (HPV), either alone or in combination with Pap testing. The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care felt that it was premature to make recommendations on such screening until the evidence in this area is further developed.

Methods

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care is an independent panel of clinicians and methodologists that makes recommendations about clinical manoeuvres aimed at primary and secondary prevention (www.canadiantaskforce.ca). Work on each set of recommendations is led by a workgroup of 2 to 6 members of the task force. Each workgroup establishes the research questions and analytical framework for the guideline.

The development of these recommendations was led by a workgroup of 5 members of the task force, in collaboration with 2 members of the Pan-Canadian Cervical Screening Initiative and supported by scientific officers from the Public Health Agency of Canada.

The workgroup established the research questions and analytical framework for the guideline (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.121505/-/DC1), which were incorporated into the search protocol. The task force chose to focus on the critically important outcomes: incidence of invasive cervical cancer and mortality. Studies describing only high-grade cervical abnormalities (i.e., cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 and 3, including carcinoma in situ) were not used, since these were considered intermediate outcomes.16 Rates of these diagnoses are highly variable between age groups and screening programs,6 and most of these lesions do not progress to invasive cervical cancer or lead to death from cervical cancer.12–14

The Evidence Review and Synthesis Centre at McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario) conducted a systematic review of the available evidence according to the final, peer-reviewed protocol. The task force used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system to determine the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations (Box 1).17 More information about the task force’s methods can be found elsewhere18 and on the task force’s website (www.canadiantaskforce.ca/methods-manual-2011.html), as well as in Appendices 1 and 2 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.121505/-/DC1).

Box 1: Grading of recommendations.

Recommendations are graded according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system.17 GRADE offers 2 strengths of recommendation: strong and weak. The strength of recommendations is based on the quality of supporting evidence, the degree of uncertainty about the balance between desirable and undesirable effects, the degree of uncertainty or variability in values and preferences, and the degree of uncertainty about whether the intervention represents a wise use of resources.

Strong recommendations are those for which the task force is confident that the desirable effects of an intervention outweigh its undesirable effects (strong recommendation for an intervention) or that the undesirable effects of an intervention outweigh its desirable effects (strong recommendation against an intervention). A strong recommendation implies that most people will be best served by the recommended course of action.

Weak recommendations are those for which the desirable effects probably outweigh the undesirable effects (weak recommendation for an intervention) or undesirable effects probably outweigh the desirable effects (weak recommendation against an intervention) but appreciable uncertainty exists. A weak recommendation implies that most people would want the recommended course of action, but many would not. For clinicians, this means they must recognize that different choices will be appropriate for individual women, and they must help each woman arrive at a management decision consistent with her own values and preferences. Policy-making will require substantial debate and involvement of various stakeholders. Weak recommendations result when the balance between desirable and undesirable effects is small, the quality of evidence is lower, and there is more variability in the values and preferences of patients.

Evidence is graded as high, moderate, low or very low, based on how likely further research is to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Recommendations

A summary of the recommendations for clinicians and policy-makers is shown in Box 2. More detailed explanations of the evidence base of the recommendations are available in Appendix 3 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.121505/-/DC1).

Box 2: Summary of recommendations for clinicians and policy-makers.

Recommendations are presented for the use of cervical cytology (Papanicolaou [Pap] tests) for women with no symptoms of cervical cancer who are or have been sexually active, regardless of sexual orientation. The recommendations do not apply to women with symptoms of cervical cancer (e.g., abnormal vaginal bleeding), women with previous abnormal results on screening (unless they have been cleared to return to normal screening), women who do not have a cervix (because of hysterectomy), women who are immunosuppressed (e.g., as a result of organ transplantation, chemotherapy, chronic corticosteroid treatment, HIV infection) or women who have limited life expectancy such that they would not benefit from screening.

The recommendations do not address screening with human papilloma virus (HPV) testing (alone or in combination with Pap testing). In our judgment, such a recommendation would be premature until the evidence in this area is further developed.

Cytology (conventional or liquid-based, manual or computer-assisted)

For women aged less than 20 years, we recommend not routinely screening for cervical cancer. (Strong recommendation; high-quality evidence)

For women aged 20–24 years, we recommend not routinely screening for cervical cancer. (Weak recommendation; moderate-quality evidence)

For women aged 25–29 years, we recommend routine screening for cervical cancer every 3 years. (Weak recommendation; moderate-quality evidence)

For women aged 30–69 years, we recommend routine screening for cervical cancer every 3 years. (Strong recommendation; high-quality evidence)

For women 70 years of age or older who have undergone adequate screening (i.e., 3 successive negative Pap test results in the last 10 yr), we recommend that routine screening may stop. For all other women 70 years of age or older, we recommend continued screening until 3 negative test results have been obtained. (Weak recommendation; low-quality evidence)

Cytology

The following recommendations refer to cytologic screening, using either conventional or liquid-based methods, whether manual or computer-assisted.

Women aged less than 20 years

For women younger than 20 years of age, we recommend not routinely screening for cervical cancer. (Strong recommendation; high-quality evidence.)

Our evidence review did not find any studies that examined the effectiveness of screening in women younger than 20 years of age. Instead, epidemiological estimates were used to determine the potential (maximum) benefit of screening for women in this age group.

Although many Canadian women in this age group undergo screening (42.2% of women aged 18 and 19 years report having undergone screening at least once within the previous 3 yr),19 the incidence of cervical cancer for these women is very low (0.2 cases per 100 000 from 2002 to 2006) (Figure 1). No deaths from cervical cancer were reported among Canadian women in this age group between 2002 and 2006 (Figure 1 and Appendix 4, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.121505/-/DC1).

Although it is thought that providing screening to women in this age group may help prevent death from cervical cancer at older ages, we identified no evidence to support this argument. We found no national Canadian data on the prevalence of abnormal screening results among women in this age group. However, data from Alberta show that, between 2006 and 2008, 10% of women who underwent screening before 20 years of age were referred for colposcopy, with a potential for harms such as pain, bleeding or discharge,20 compared with lower rates of these harms at older ages.9 Data from British Columbia also show the highest rates of cytological abnormality among young women.21

Our recommendation is based on a very low incidence of and mortality due to cervical cancer in this age group, no studies addressing effectiveness for this age group, and evidence of minor harms to about 10% of women who undergo screening and more serious harms for some women who go on to further treatment. A strong recommendation against screening reflects our judgment that the potential harms of screening for women in this age group outweigh the benefits.

Women aged 20–29 years

For women aged 20–24 years, we recommend not routinely screening for cervical cancer. (Weak recommendation; moderate-quality evidence.) For women aged 25–29 years, we recommend routine screening for cervical cancer every 3 years. (Weak recommendation; moderate-quality evidence.)

We found no evidence assessing the effectiveness of screening on decreasing mortality for women in this age group.11 The only study we found that specifically examined screening for women aged 20–24 years22 showed that screening at ages 20–21 years (odds ratio [OR] 1.5, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.0–2.4) or 22–24 years (OR 1.1, 95% CI 0.8–1.5) had no significant impact on the incidence of cervical cancer at ages 25–29 years. There has been no reduction in mortality due to cervical cancer among women aged 20–24 years in Canada since the 1970s, when screening became widespread (Appendix 4).

We found little information on the harms of screening for cervical cancer stratified by age group. However, the evidence review identified 22 studies that reported test accuracy in precancerous lesions.11 Specificity for precancerous lesions tends to be lower, and the risk of false-positive tests higher, for women less than 30 years of age, leading to more unnecessary diagnostic and treatment procedures in younger women.

Rates of abnormal Pap test results are highest among young women and decrease with age. In Canada, 9.8% of women aged 20–29 years had abnormal test results; this number declines to 1.6% for women aged 60–69 years.8 A high-grade lesion was found in 1.5% of women aged 20–29 years;8 these women are then referred for colposcopy and possible biopsy, and more than 50% of them will likely receive further treatment. Thus, there is a high incidence of minor harms9 and the potential for future early pregnancy loss or premature labour for women in this age group.23–26

Our recommendation for women aged 20–24 years not to undergo screening reflects the low incidence of cervical cancer and associated mortality in this age group (from 2002–2006, incidence 1.3 per 100 000 population, mortality 0.2 per 100 000 population [Appendix 4]); the uncertain benefit of screening for women in this age group, either immediately or at older ages; and the higher risk of false-positive test results (and their associated harms) compared with older women. We conclude that the harms of screening for cervical cancer in women aged 20–24 years outweigh any potential benefits, but we have assigned a weak recommendation given the uncertainty of the evidence.

Our recommendation for women aged 25–29 years to undergo screening shows our concern for the higher incidence of and mortality due to cervical cancer in this age group than in younger women (Appendix 4), which suggests that the benefit of screening for these women could be greater. However, the limitations of Pap testing for these women are similar to those for women aged 20–24 years. Therefore, we have assigned a weak recommendation for this age group, reflecting our concerns about the rate of false-positive results and the harms of overtreatment.

The weak recommendation implies that, although most women would want to follow the recommended course of action, many would not. Women who place a relatively higher value on avoiding invasive cervical cancer and a relatively lower value on the potential harms of screening will be more likely to choose screening. Therefore, clinicians should discuss the potential benefits and harms of screening with their patients and help each woman make a decision that is consistent with her values, preferences and exposure to risk.

Women aged 30–69 years

For women aged 30–69 years, we recommend routine screening for cervical cancer every 3 years. (Strong recommendation; high-quality evidence.)

National cohort studies show a strong association between the introduction of screening and reduced incidence of cervical cancer.6,27 The effect of screening on incidence of invasive cervical cancer is shown in Appendix 5 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.121505/-/DC1). A meta-analysis of 12 case–control studies28–39 showed that the odds of having undergone at least 1 Pap test were lower among women with invasive cervical cancer (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.3–0.4, Appendix 5) than among women who did not have cervical cancer. A cohort study with a 3-year follow-up found that screening was associated with a decrease in incidence of cervical cancer (relative risk 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–0.6),38 whereas a randomized controlled trial (RCT) from rural India found a nonsignificant effect of screening on incidence.40 This RCT also found a single lifetime cytologic test had a nonsignificant effect on 8-year mortality (age-adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0.9, 95% CI 0.6–1.3).40

In recent Canadian data, the prevalence of abnormal results among women who have undergone screening declined with age and was reported to be 4.5% between the ages of 30 and 39 years, 3.5% for ages 40–49 years, 2.4% for ages 50–59 years and 1.6% for ages 60–69 years.8 The proportion of high-grade lesions also declined with age (Appendix 6, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.121505/-/DC1).8 Thus, the rates of biopsy and subsequent treatment decrease with increasing age, although the rate at which cancer is detected remains steady after 40 years of age. Pregnancy-related harms become less important as women complete their childbearing.

This recommendation places a high value on the evidence for the effectiveness of screening, as well as higher cervical cancer incidence and mortality among women in this age group, balanced against the lower rates of potential harms compared with younger women. The strong recommendation is based on our confidence that the desirable effects of screening outweigh the undesirable effects and that most women would be best served by the recommended course of action.

Women aged 70 years or older

For women aged 70 years and older who have undergone adequate screening (i.e., 3 successive negative Pap test results in the previous 10 years), we recommend that routine screening may end. For women aged 70 years and older who have not undergone adequate screening, we recommend continued screening until 3 negative test results have been obtained. (Weak recommendation; low-quality evidence.)

There is little evidence regarding at what age to stop screening, although other countries have a policy to stop screening women over the ages of 65 or 70 years given adequate previous screening.41–43 Evidence for the definition of adequate previous screening is unclear. The US combined societies report44 acknowledged the lack of evidence and used a modelling study45 that suggested that, for women who had not undergone screening, “a few” screens resulted in extra life expectancy. European policy advises that 2 tests with negative results are sufficient.7 Limited evidence suggests that the protective effect of screening remains strong in women aged 70 years and older. One study34 reported lower odds of screening among women in this age group with cervical cancer (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–0.5), compared with women who did not have cervical cancer. A second study35 reported that women aged 65–74 years with invasive cervical cancer had lower rates of previous screening than women who did not have cancer (32% v. 40%), but found no difference among women aged 75 years and older.

Mortality from cervical cancer in Canada increases with age, as does incidence until ages 40–44 years, and remains high (Figure 1). Although there is limited evidence for the benefits of screening in older women, this is largely because of the exclusion of this age group from most of the studies reviewed. The persistent high incidence of and mortality due to cervical cancer among Canadian women aged 70 years and older may be due to low screening rates in older age groups, or may reflect the incidence of disease among women who have never undergone screening. Given these possibilities, healthy women in this age group may derive some benefit from screening if they have not undergone adequate screening previously.

The recommendation to end screening at 70 years of age places high value on the limited evidence that adequate screening until this age detects early changes and prevents the development of invasive cancer, balanced against the evidence of fewer harms to women in this age group.

The recommendation to ensure that women who have previously not undergone screening do so places relatively high value on the limited evidence for the effectiveness of screening, on the persisting incidence and increasing mortality at older ages, and on the potential to detect and treat cervical cancer in this age group. That the recommendation is weak implies that the potential benefits of screening should be discussed with each woman in relation to her individual preferences and the value she places on the potential reductions in risk.

Recommended screening interval

Thirteen case–control studies34–39,46–52 and 2 cohort studies53,54 suggest that screening intervals of 5 years or less appear to offer women substantial protection against cervical cancer. A greater benefit was seen with shorter intervals in some of these studies. In the judgment of the task force, the recommended 3-year interval balances the small incremental potential for benefit from shorter intervals against the greater potential for harm from increased testing and procedures with more frequent screening. Most countries outside North America use 3- or 5-year intervals.55

Human papilloma virus testing

Most studies of HPV testing have shown reductions in precancerous lesions rather than in the incidence of or mortality due to cervical cancer. Only 2 studies included in the search have measured these final outcomes.40,56 One RCT that reported the effectiveness of HPV testing on reducing the incidence of and mortality associated with invasive cervical cancer and mortality studied the effect of a single lifetime screen among Indian women over 30 years of age who had previously not undergone screening; thus, the applicability of its findings to Canadian women is uncertain.40 A second trial, from Finland, did not find HPV testing to significantly further reduce the incidence of cervical cancer.56

Tests for HPV are not currently offered in all provinces and are more costly than cytologic testing. Although HPV testing may be more sensitive than cytology,57–59 which could allow for a longer screening interval and result in fewer tests, there may be an initial higher incidence of positive test results requiring follow-up colposcopy. Some provinces recommend a combination of HPV and cytologic testing.60,61 Pap testing is already very effective, and there is some evidence that adding HPV testing in a cotesting program may provide a small additional benefit in terms of reducing the rate of cervical cancer.62 However, there are many different technologies available for HPV testing, and there are several ongoing clinical trials that may clarify the preferable method of incorporating it into the screening process. Given these uncertainties, the task force felt it premature to make a recommendation on the use of HPV testing in screening (either alone or in combination with Pap testing). However, we will revisit this issue as new data become available.

Considerations for implementation

Evidence from countries that begin screening at an older age and with a longer interval between screens than is usual in Canada suggests that organized screening is more effective than opportunistic screening.56,63–66 Some Canadian provinces have established such programs, and the rest are developing them.8 Most provinces have recently revised their guidelines. Previously, some provinces recommended annual screening starting at early ages, but all have now increased the starting age and intervals between screens. Doctors in each province will need to consider their population and resources in applying the task force’s recommendations.

One randomized trial67 found no significant differences in the incidence of or mortality due to cervical cancer between women undergoing conventional cytologic screening (manual reading of screens) and computer-assisted screening (computer-assisted reading of screens). Based on this evidence, either reading technique may be used for women of any age for whom Pap tests are recommended. Although no identified studies compared liquid-based to conventional cytology in terms of incidence of and mortality due to cervical cancer, the sensitivity and specificity of liquid-based and conventional cytology are similar.11

Increased or decreased screening may be appropriate for women with different risk profiles. Women who have had a complete hysterectomy for benign disorders no longer need to undergo screening, whereas women who are immunocompromised may benefit from more frequent screening.7 There is very limited evidence available as to the benefits of screening among women who have sex with women; however, because this group is at risk for cervical cancer, they should be advised to undergo screening according to these recommendations.68 We found no evidence to recommend a specific interval between first sexual activity (with potential for HPV infection) and first need for screening, nor for more frequent screening for women at increased risk owing to multiple sexual partners.

Practitioners should be aware of women’s values, preferences and beliefs about screening and discuss these in the context of the potential benefits and harms of the screening process. Certain subgroups of women are less likely to receive adequate screening, including immigrant groups,69,70 Aboriginal women71 and women with very low socioeconomic status.69,72 Many women prefer female health care providers to perform screening.73–76 In addition, cultural views on screening may affect a woman’s willingness to undergo the procedure,77,78 as might misconceptions regarding Pap testing.79–81 Other factors affecting the willingness to undergo screening include fear, fatalistic attitudes, embarrassment, fear of pain or discomfort, anxiety and stress related to diagnosis, distrust of the health care system and the belief that screening is not necessary without illness.11

The limited evidence regarding patient preferences for screening intervals82,83 suggests that women who are used to undergoing frequent screening prefer the feeling of security provided by shorter rather than longer screening intervals, and that they are concerned that recommendations for longer intervals between screens are primarily a means to save costs.84 Therefore, the potential harms and benefits should be discussed between patient and provider for informed decision-making.

Evidence concerning the performance of Pap tests by different types of health care professionals was limited. Our search found only 1 case–control study,85 which reported that nongynecologist physicians were twice as likely as gynecologists to collect unsatisfactory cervical specimens in a US teaching hospital. However, results at this centre may not be generalizable. In the UK, where practice nurses obtain cervical specimens, better training improved both the quality of the specimens and policy adherence.86

Suggested performance measures for implementation

Recommended indicators are designed to measure Pap testing at the level of individual primary care practices. Suggested performance measures include rates of discussion about cervical cancer screening, actual rates of testing and subsequent follow-up (Appendix 7, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.121505/-/DC1). The incidence of and mortality due to cervical cancer should continue to be monitored at the provincial, territorial and national levels.

Economic implications of screening

Most of the economic studies reviewed did not assess the relative cost-effectiveness of cytologic or HPV testing alone. Available data from a Canadian economic modelling study87 suggest that screening with either cytology (every year or every 3 years) or HPV testing (every 3 years) is highly cost-effective compared with no screening.

Other guidelines

The current guideline differs from previous recommendations of the task force in that routine screening is not recommended for sexually active women who are less than 25 years of age, and screening is now explicitly recommended for women older than 69 years if previous screening has not been adequately performed. A summary of the current guideline has been prepared for use by family physicians and other health care professionals (Appendix 8, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.121505/-/DC1).

A comparison of recommendations for cervical screening from several other organizations is in Table 1.15,41–43,88–90 Notably, although the US task force supported the use of HPV testing for women 30 years of age and older at 5-year intervals, it noted that the evidence is still evolving and that this approach may increase the rates of investigation and overtreatment.

Table 1:

Comparison of recommendations for screening for cervical cancer

| Organization or country | Recommendation by age, yr | HPV testing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 20 | 20–24 | 25–29 | 30–69 | ≥ 70 | ||

| Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (current)* | Recommend against routine screening | Recommend against routine screening | Every 3 yr with cervical cytology | Every 3 yr with cervical cytology | Every 3 yr with cervical cytology if previous screening inadequate and until 3 negative results have been received; otherwise, screening may stop | No recommendation; will revisit the issue as new data become available |

| Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (1994)15 | Every year with cervical cytology after start of sexual activity or at age 18 yr | After 2 normal Pap results, every 3 yr to age 69 yr; frequency may be increased in the presence of risk factors | After 2 normal Pap results, every 3 yr to age 69 yr; frequency may be increased in the presence of risk factors | After 2 normal Pap results, every 3 yr to age 69 yr; frequency may be increased in the presence of risk factors | Not recommended | Not applicable |

| US Preventive Services Task Force (2012)42 | Recommend against routine screening under age 21 yr | Recommend against routine screening under age 21 yr Every 3 yr with Pap testing ages 21–65 yr | Every 3 yr with Pap testing ages 21–65 yr | Every 3 yr with Pap testing ages 21–65 yr Recommend against screening for women older than age 65 yr who have had adequate prior screening and are not otherwise at high risk | Recommend against screening for women older than age 65 yr who have had adequate prior screening and are not otherwise at high risk | In combination with cytology (cotesting), every 5 yr for women ages 30–65 yr who want to lengthen the screening interval |

| Government of Australia (2011)43 | First Pap test at about 18–20 yr or 1 or 2 yr after first having sex, whichever is later | Every 2 yr with Pap testing | Every 2 yr with Pap testing | Every 2 yr with Pap testing | Practitioner may advise that it is safe to stop Pap testing if previous results have been normal | No recommendation |

| National Health Service Cervical Screening Program, UK (2011)41 | Not invited to screen | Not invited to screen | Every 3 yr with cytology for women aged 25–49 yr | Every 3 yr with cytology for women aged 25–49 yr Every 5 yr with cytology for women aged 50–64 yr Women aged ≥ 65 yr to undergo screening only if they have not had screening since age 50 yr, or they have had recent abnormal test results |

Women aged ≥ 65 yr to undergo screening only if they have not had screening since age 50 yr, or they have had recent abnormal test results | Additional (triage) HPV testing is recommended for women ≥ 25 yr with abnormal test results in some circumstances |

| Health Council of the Netherlands (2011)88 | Not invited to screen | Not invited to screen | Not invited to screen | Every 5 yr for women aged 30–40 yr Every 10 yr for women aged 50–60 yr |

Not invited to screen | HPV should replace cytology as the primary screening method; if using Pap test, triage HPV testing is recommended for women ≥ 30 yr with abnormal test results in some circumstances |

| National Cancer Screening Service, Ireland (2011)89 | Not invited to screen | Not invited to screen | Every 3 yr for women aged 25–44 yr Every 5 yr for women aged 45–60 yr (regardless of age at first screening, women must have 2 normal results 3 yr apart before moving to a 5-yr interval) |

Every 3 yr for women aged 25–44 yr Every 5 yr for women aged 45–60 yr (regardless of age at first screeing, women must have 2 normal results 3 yr apart before moving to a 5- yr interval) |

Not invited to screen | No recommendation |

| National Health Service, Scotland (2010)90 | Not invited to screen | Every 3 yr for women aged 20–60 yr | Every 3 yr for women aged 20–60 yr | Every 3 yr for women aged 20–60 yr | Not invited to screen | No recommendation |

Note: HPV = human papilloma virus, Pap = Papanicolaou.

Recommendations made for women who were ever sexually active. Recommendations do not apply to women with symptoms of cervical cancer or previous abnormal screening results, to women who do not have a cervix or to women who are immunocompromised.

Gaps in knowledge

More research is needed on the effectiveness and optimal use of HPV screening in decreasing the incidence of and mortality due to cervical cancer, the optimum screening interval and the optimal ages at which to start and stop screening. It would also be helpful to obtain better information concerning how long screening can be delayed after first sexual activity and whether women with certain risk profiles require different screening protocols.

Although there are high rates of “low-grade” lesions, greatest among women at young ages (i.e., age < 30 yr), evidence on the psychological and pregnancy-related harms of these lesions is limited. Given the variation in populations and methods used, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions from the available data. Canadian population-based estimates of the downstream harms of treating precancerous lesions are inadequate to inform policy, particularly for women in this age group.

Although there is a cohort of younger women who have received vaccination against HPV, reducing their risk of infection by 2 of the most common oncogenic strains of the virus, the vaccine is recent and there is currently insufficient evidence on which to base recommendations for screening for this group. For now, these women should continue to undergo screening as per the recommendations for their age group.

Conclusion

Our recommendations aim to balance the benefits of screening for cervical cancer with its potential harms for women of different ages. High-quality evidence for women aged 30–69 years leads to a strong recommendation for routine screening. The evidence for the value of screening and the balance of benefits and harms for women outside of this age group is unclear, leading to weaker recommendations for routine screening (women aged 25–29 yr) and against screening (women aged 20–24 yr or ≥ 70 yr).

Key points

High-quality evidence shows that screening for cervical cancer with Papanicolaou (Pap) tests reduced mortality and morbidity among women aged 30–69 years; the task force strongly recommends screening for women in this age group at 3-year intervals.

Moderate-quality evidence shows that screening with Pap tests may have a small effect in reducing mortality and morbidity associated with cervical cancer among women aged 25–29 years; however, among women less than 25 years of age, we found no benefit to outweigh the potential harms.

Screening may stop in women aged 70 years and older after 3 successive negative Pap test results.

Where the recommendations are weak, health care providers should discuss the balance between the potential benefits and harms of screening with Pap tests to help each woman make an informed decision about screening that is consistent with her values and preferences.

These updated recommendations do not address screening with tests for human papilloma virus, because there is not yet sufficient data on its effect on mortality and incidence of invasive carcinoma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the staff at the Task Force Office of the Public Health Agency of Canada (Sue Pollock, who worked on the development of the research questions and the analytic framework for the research protocol; Lesley Dunfield, for her work on developing and implementing the research protocol; and Amanda Shane for her work on editing the guideline document); the peer reviewers (both named and anonymous) whose thoughtful comments helped to improve the quality of this manuscript (Jon Kerner and Heather Bryant, Canadian Partnership Against Cancer; Margaret Czesak, Barbara Foster and Gilles Plourde, Health Canada; Erica Weir, University of Toronto and Queen’s University; Louise Pelletier, Public Health Agency of Canada; Robert Nuttall, Canadian Cancer Society; Chris Del Mar, Bond University; Gina Ogilvie, British Columbia Centre for Disease Control and University of British Columbia; and Julietta Patnick, National Health Services Cancer Screening Programmes).

See related commentary by Dollin on page 13 and at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.121781

Footnotes

Competing interests: None of the members of the guidelines writing group (listed at the end of the article) have declared competing interests.

The list of current members of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care is available at www.canadiantaskforce.ca/members_eng.html

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All of the authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the article, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Funding: Funding for the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care is provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The views of the funding body have not influenced the content of the guideline; competing interests have been recorded and addressed. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent those of the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Guidelines writing group: James Dickinson, Eva Tsakonas, Sarah Connor Gorber, Gabriela Lewin, Elizabeth Shaw, Harminder Singh, Michel Joffres, Richard Birtwhistle, Marcello Tonelli, Verna Mai and Meg McLachlin.

References

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee on Cancer Statistics Canadian cancer statistics. Toronto (ON): the Society; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franco EL, Duarte-Franco E, Ferenczy A. Cervical cancer: epidemiology, prevention and the role of human papillomavirus infection. CMAJ 2001;164:1017–25 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickinson JA, Stankiewicz A, Popadiuk C, et al. Reduced cervical cancer incidence and mortality in Canada: national data from 1932 to 2006. BMC Public Health 2012;12:992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walton RJ. Cervical cancer screening programs (DNH&W report). CMAJ 1976;114:1003–12 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller AB, Lindsay J, Hill GB. Mortality from cancer of the uterus in Canada and its relationship to screening for cancer of the cervix. Int J Cancer 1976;17:602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Agency for Research on Cancer and World Health Organization Cervix cancer screening. In: Handbooks on cancer prevention, volume 10. Lyon (France): IARC Press; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Agency for Research on Cancer European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening 2nd edition Lyon (France): the Agency; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canadian Partnership Against Cancer Cervical cancer screening in Canada monitoring program performance. Toronto (ON): the Partnership; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 9.TOMBOLA (Trial of Management of Borderline and Other Low-grade Abnormal smears), Sharp L, Cotton S, Cochran C, et al. After-effects reported by women following colposcopy, cervical biopsies and LLETZ: results from the TOMBOLA trial. BJOG 2009;116:1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Founta C, Arbyn M, Valasoulis G, et al. Proportion of excision and cervical healing after large loop excision of the transformation zone for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. BJOG 2010;117:1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peirson L, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Ciliska D, et al. Screening for cervical cancer. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care; 2012. Available: www.canadiantaskforce.ca (accessed 2012 Nov. 29). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holowaty P, Miller AB, Rohan T, et al. Natural history of dysplasia of the uterine cervix. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:252–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCredie MR, Sharples KJ, Paul C, et al. Natural history of cervical neoplasia and risk of invasive cancer in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:425–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barken SS, Rebolj M, Andersen ES, et al. Frequency of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia treatment in a well-screening population. Int J Cancer 2012;130:2438–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison BJ. Screening for cervical cancer. In: Canadian guide to clinical preventive health care. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yudkin JS, Lipska KJ, Montori VM. The idolatry of the surrogate. BMJ 2011;343:d7995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schünemann H, Brozek J, Oxman A, editors. Grade handbook for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations; Version 3.2 [updated March 2009]. The GRADE Working Group; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connor Gorber S, Singh H, Pottie K, et al. Process for guideline development by the reconstituted Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. CMAJ 2012;184:1575–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Table 105-0442: Pap smear by age group, females aged 18–69 years, Canada, provinces, territories, health regions (June 2005 boundaries) and peer groups, every 2 years. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2006. Available: www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?Lang=eng&retrLang=eng&id=1050442%20&paSer=&pattern=&stByVal=1&p1=1&p2=-1&tabMode=dataTable&csid= (accessed 2012 Feb. 23). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Towards Optimized Practice Program Guideline for screening for cervical cancer. Edmonton (AB): The Program; 2006. Available: www.topalbertadoctors.org/download/587/cervical+cancer+guideline.pdf (accessed 2012 Dec. 10). [Google Scholar]

- 21.BC Cancer Agency Cervical screening program: 2010 annual report. Vancouver (BC): the Agency; 2011. Available: www.bccancer.bc.ca/NR/rdonlyres/A6E3D1EC-93C4-4B66-A7E8-B025721184B2/57824/CCSP_2011AR_June6.pdf (accessed 2012 Apr. 20). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasieni P, Castanon A, Cuzick J. Effectiveness of cervical screening with age: population based case–control study of prospectively recorded data. BMJ 2009;339:b2968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arbyn M, Kyrgiou M, Simoens C, et al. Perinatal mortality and other severe adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: meta-analysis. BMJ 2008;337:a1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lima AF, Francisco C, Julio C, et al. Obstetric outcomes after treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: six years of experience. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2011;15:276–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poon LC, Savvas M, Zamblera D, et al. Large loop excision of transformation zone and cervical length in the prediction of spontaneous preterm delivery. BJOG. 2012;119:692–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson LF, Rayner JA, King J, et al. Intracervical procedures and the risk of subsequent very preterm birth: a case–control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91:204–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arbyn M, Raifu AO, Weiderpass E, et al. Trends of cervical cancer mortality in the member states of the european union. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:2640–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clarke EA, Anderson TW. Does screening by “Pap” smears help prevent cervical cancer? Lancet 1979;2:1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nieminen P, Kallio M, Anttila A, et al. Organised vs. spontaneous Pap-smear screening for cervical cancer: a case–control study. Int J Cancer 1999;83:55–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Decker K, Demers A, Chateau D, et al. Papanicolaou test utilization and frequency of screening opportunities among women diagnosed with cervical cancer. Open Med 2009;3:e140–7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernández-Avila M, Lazcano-Ponce EC, de Ruiz PA, et al. Evaluation of the cervical cancer screening programme in Mexico: a population-based case–control study. Int J Epidemiol 1998;27:370–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Talbott EO, Norman SA, Kuller LH, et al. Refining preventive strategies for invasive cervical cancer: a population-based case–control study. J Womens Health 1995;4 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aristizabal N, Cuello C, Correa P, et al. The impact of vaginal cytology on cervical cancer risks in Cali, Colombia. Int J Cancer 1984;34:5–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrae B, Kemetli L, Sparén P, et al. Screening-preventable cervical cancer risks: evidence from a nationwide audit in Sweden. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:622–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoffman M, Cooper D, Carrara H, et al. Limited Pap screening associated with reduced risk of cervical cancer in South Africa. Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:573–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiménez Prez M, Thomas DB. Has the use of Pap smears reduced the risk of invasive cervical cancer in Guadalajara, Mexico? Int J Cancer 1999;82:804–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Makino H, Sato S, Yajima A, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of cervical cancer screening: a case–control study in Miyagi, Japan. Tohoku J Exp Med 1995;175:171–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berrino F, Gatta G, d’Alto M, et al. Efficacy of screening in preventing invasive cervical cancer: a case–control study in Milan, Italy. IARC Scientific Publ 1986;76:111–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herrero R, Brinton LA, Reeves WC, et al. Screening for cervical cancer in Latin America: a case–control study. Int J Epidemiol 1992;21:1050–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, et al. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1385–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Health Service NHS cervical screening programme. London (UK): the Service; 2011. Available: www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/cervical (accessed 2012 Apr. 20). [Google Scholar]

- 42.US Preventive Services Task Force Screening for cervical cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:880–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Department of Health and Ageing National cervical screening program. Canberra (Australia): Australian Government; Available: www.cancerscreening.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing.nsf/Content/cervical-about (accessed 2012 Apr. 20). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol 2012;137:516–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kulasingam SL, Havrilesky L, Ghebre R, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: a decision analysis for the US preventive services task force. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sasieni PD, Cuzick J, Lynch-Farmery E, et al. Estimating the efficacy of screening by auditing smear histories of women with and without cervical cancer. Br J Cancer 1996;73:1001–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller MG, Sung HY, Sawaya GF, et al. Screening interval and risk of invasive squamous cell cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101:29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sasieni P, Adams J, Cuzick J. Benefit of cervical screening at difference ages: evidence from the UK audit of screening histories. Br J Cancer 2003;89:88–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sasieni P, Castanon A, Cuzick J. Screening and adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Int J Cancer 2009;125:525–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang B, Morrell S, Zuo Y, et al. A case–control study of the protective benefit of cervical screening against invasive cervical cancer in NSW women. Cancer Causes Control 2008;19:569–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zappa M, Visioli CB, Ciatto S, et al. Lower protection of cytological screening for adenocarcinomas and shorter protection for younger women: the results of a case–control study in Florence. Br J Cancer 2004;90:1784–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.La Vecchia C, Franceschi S, Decarli A, et al. “Pap” smear and the risk of cervical neoplasia: quantitative estimates from a case–control study”. Lancet 1984;2:779–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Herbert A, Stein K, Bryant TN, et al. Relation between the incidence of invasive cervical cancer and the screening interval: Is a five year interval too long? J Med Screen 1996;3:140–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rebolj M, van Ballegooijen M, Lynge E, et al. Incidence of cervical cancer after several negative smear results by age 50: prospective observational study. BMJ 2009;338:b1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anttila A, von Karsa L, Aasmaa A, et al. Cervical cancer screening policies and coverage in Europe. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:2649–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anttila A, Nieminen P. Cervical cancer screening programme in Finland with an example on implementing alternative screening methods. Coll Antropol 2007;31:17–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cochand-Priollet B, Le Galès C, de Cremoux CP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of monolayers and human papillomavirus testing compared to that of conventional Papanicolaou smears for cervical cancer screening: protocol of the study of the French society of clinical cytology. Diagn Cytopathol 2001;24:412–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Szarewski A, Mether D, Cadman L, et al. Comparison of seven tests for high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in woman with abnormal smears: the Predictors 2 study. J Clin Microbiol 2012;50:1867–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ronco G, Dalla Palma P, Del Mistro A, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:249–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ontario cervical screening cytology guidelines summary. Toronto (ON): Cancer Care Ontario; 2012. Available: www.cancercare.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=13104 (accessed 2012 Oct. 19). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guidelines on cervical cancer screening in Québec. Québec (QC): Institut national de santé publique du Québec; 2011. Available: www.inspq.qc.ca/pdf/publications/1371_GuidelinesCervicalCancerScreeningQc.pdf (accessed 2012 Oct. 19). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:78–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lynge E, Rebolj M. HPV screening for cervical cancer prevention: results from European trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2009;6:699–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arbyn M, Rebolj M, de Kok IM, et al. The challenges of organising cervical screening programmes in the 15 old member states of the European Union. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:2671–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lynge E, Clausen LB, Guignard R, et al. What happens when organization of cervical cancer screening is delayed or stopped? J Med Screen 2006;13:41–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Kok IM, van der Aa MA, van Ballegooijen M. Trends in cervical cancer in The Netherlands until 2007: Has the bottom been reached? Int J Cancer 2011;128:2174–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anttila A, Pokhrel A, Kotaniemi-Talonen L, et al. Cervical cancer patterns with automation-assisted and conventional cytological screening: a randomized study. Int J Cancer 2011;128:1204–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fish J. Cervical cancer screening in lesbian and bisexual women: a review of the worldwide literature. Leicester (UK): DeMontfort University; 2009. Available: www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/cervical/publications/screening-lesbians-bisexual-women.pdf (accessed 2012 Apr. 20). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lofters AK, Hwang SW, Moineddin R, et al. Cervical cancer screening among urban immigrants by region of origin: a population-based cohort study. Prev Med 2010;51:509–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lofters AK, Moineddin R, Hwang SW, et al. Low rates of cervical cancer screening among urban immigrants: a population-based study in Ontario, Canada. Med Care 2010;48:611–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Demers AA, Kliewer EV, Remes O, et al. Cervical cancer among aboriginal women in Canada. CMAJ 2012;184:743–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Johnston GM, Boyd CJ, MacIsaac MA. Community-based cultural predictors of Pap smear screening in Nova Scotia. Can J Publ Health 2003;95:95–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barghouti FF, Takruri AH, Froelicher ES. Awareness and behavior about Pap smear testing in family medicine practice. Saudi Med J 2008;29:1036–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith AJ, Christopher S, LaFrombroise VR, et al. Apsaalooke women’s experiences with Pap test screening. Cancer Control 2008;15:166–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Johnson CE, Mues KE, Mayne SL, et al. Cervical cancer screening among immigrants and ethnic minorities: a systematic review using the health belief model. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2008;12:232–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thomas VN, Saleem T, Abraham R. Barriers to effective uptake of cancer screening among black and minority ethnic groups. Int J Palliat Nurs 2005;11:564–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.O’Brien BA, Mill J, Wilson T. Cervical screening in Canadian First Nation Cree women. J Transcult Nurs 2009;20:83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang JH, Sheppard VB, Schwartz MD, et al. Disparities in cervical cancer screening between Asian American and Hispanic white women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17:1968–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ji CS, Chen MY, Sun J, et al. Cultural views, English proficiency and regular cervical cancer screening among older Chinese American women. Womens Health Issues 2010;20:272–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chang SC, Woo JS, Gorzalka BB, et al. A questionnaire study of cervical cancer screening beliefs and practices of Chinese and caucasian mother–daughter pairs living in Canada. J Obstet Gynecol Can 2010;32:254–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brotto LA, Chou AY, Singh T, et al. Reproductive health practices among Indian, Indo-Canadian, Canadian east Asian and Euro-Canadian women: the role of acculturation. J Obstet Gynecol Can 2008;30:229–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meissner HI, Tiro JA, Yabroff KR, et al. Too much of a good thing: physician practices and willingness for less frequent Pap test screening intervals. Med Care 2010;48:249–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fiebig DG, Haas M, Hossain I, et al. Decisions about Pap tests: what influences women and providers. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:1766–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sirovich BE, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. Screening for cervical cancer: Will women accept less? Am J Med 2005;118:151–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cole ME, Milam MR, Scott TA, et al. Inadequate screening in patients evaluated by nongynecologists for cervical cancer: a case–control analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:e48–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Faulkner K, Greenwod L, Stamp E. An assessment of smear taker training in the northern & Yorkshire cervical screening programme. J Med Screen 2003;10:201–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vijayaraghavan A, Efrusy MB, Mayrand MH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of high-risk human pappilomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening in Québec, Canada. Can J Publ Health 2010;101:220–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Health Council of The Netherlands Population screening for cervical cancer. The Hague (The Netherlands): the Council; 2011. Available: www.gezondheidsraad.nl/en/publications/population-screening-cervical-cancer (accessed 2012 Apr. 20). [Google Scholar]

- 89.National Cervical Cancer Screening Programme (Ireland) Cervical check. 2011. Available: www.cervicalcheck.ie/about-us/cervicalcheck.84.html (accessed 2012 Nov. 19).

- 90.National Health Service Scotland Cervical screening. 2010. Available: www.healthscotland.com/topics/health-topics/screening/cervical.aspx (accessed 2012 Nov. 19).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.