People shopping for a psychiatric disorder, or psychiatrists looking to expand their scope of practice and billing codes, will need look no further than the forthcoming fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V), critics say.

Revisions to the long overdue “bible of psychiatry” were approved by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) in late November after “a decade of arduous work and tens of thousands of pro-bono hours from more than 1,500 experts,” Dr. Dilip Jeste, the association’s president announced in a Dec. 1 letter to the psychiatric community (www.psychnews.org/files/DSM-message.pdf). After missing two previous publication deadlines (www.cmaj.ca/content/182/1/15.full), the new catechism will finally hit the shelves in May 2013 and the early reviews indicate that huge controversies and divides will remain.

“I’m cringing at this new DSM. How can someone trust a manual that is pathologizing bereavement?” asks Dr. Roger McIntyre, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit at the University of Toronto in Ontario.

The former editor of the DSM-IV, Dr. Allen Frances, appears no less aghast.

“Most of the changes made to the DSM-V are based on limited data, the evidence is remarkably weak for changing anything,” he says. “DSM-V opens up the possibility that millions and millions of people currently considered normal will be diagnosed as having a mental disorder and will receive medication and stigma that they don’t need.”

It is, indeed, a long way from the first edition of the DSM, which was published in 1952 and intended to be primarily a compendium of statistical information on mental disorders. Created in response to the needs of the time — military personnel returning from World War II suffered from a slew of mental disturbances that caused impairments similar to physical conditions — it was 130 pages long and listed 106 mental disorders. Although relatively insignificant, and having little impact on the field, the manual was used to quantify the growing public health problem that was mental illness (Am J Psychiatry 1991;148[4]:421–31).

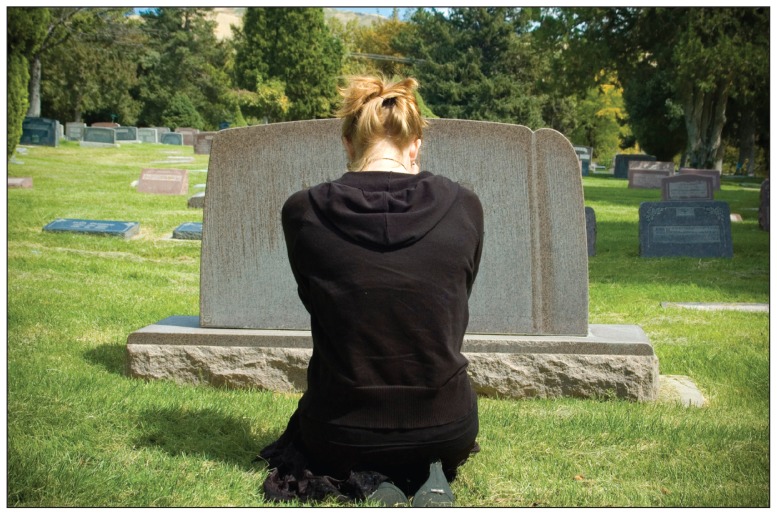

Mourning the loss of a loved one may put someone at risk of being called mentally ill under revisions to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, an expert says.

Image courtesy of © 2013 Thinkstock

By the 1960s and ‘70s, the DSM began to become inadvertently embroiled in a psychiatric civil war, a fierce ideological dispute between a camp of Freudian psychoanalysts, who believed mental illness was the result of intrapsychic conflict, and disciples of German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin, who believed that psychiatric disease was a function of biological and genetic malfunction. Rarely did either camp agree on anything (Am J Psychiatry 1969; 10:Suppl:21–9).

Psychiatry giant Dr. Robert Spitzer, who many call the “architect of the modern classification of mental disorders,” proposed a compromise solution that purposely ignored etiological ideologies. “Little progress has been made toward understanding the pathophysiological processes and etiology of mental disorders. If anything, the research has shown the situation is even more complex than initially imagined, and we believe not enough is known to structure the classification of psychiatric disorders according to etiology,” he later explained (JAMA 2005; 294:1898–99).

And thus was born the 494-page DSM-III in 1980, replete with 265 diagnostic categories.

“Spitzer adopted a system that was designed to particularly remove inference, relying solely on what you see,” Frances says. “This was intended to increase reliability and agreement. DSM-III sacrificed validity in some instances for agreement. Reliability after all is an absolute prerequisite for validity.”

But the creation of a “cookbook” style DSM also served as a virtual invitation to whip up new psychiatric concoctions, France adds. By 1994, the next edition, DSM-IV, had swelled to 297 disorders in 886 pages. “Diagnostic inflation became rampant, now 50% of adults by age 32 will have an anxiety disorder, we’ve had a tripling of ADD [attention deficit disorder] in the last 10 years. … The book as written may be very different than the book as used.”

The APA cited the need to contain diagnostic inflation, and the need to address the “wealth” of advances in neurosciences, as the rationale for another overhaul of the DSM (www.psychnews.org/files/DSM-message.pdf).

But Frances argues that the new edition will have precisely the opposite effect, in terms of containing diagnostic inflation. “Instead of it making it harder to get a diagnosis, the new DSM is going to make it much easier.”

As for the incorporation of advances of neurosciences, McIntyre is skeptical. “Neuroscience hasn’t made its way into clinical psychiatry, so these advances were never incorporated in the new DSM,” he says. “We most certainly do not have enough data to inform any of these new categories.”

Like others, McIntyre is puzzled by some of the new categories, and a number of controversial category changes (www.psych.org/File%20Library/Advocacy%20and%20Newsroom/Press%20Releases/2012%20Releases/12-43-DSM-5-BOT-Vote-News-Release--FINAL--3-.pdf).

Bereavement, for example, was once an exclusion criterion to the diagnosis of major depressive disorder, but it has now been removed, he notes. “The implications of this removal remain unclear. But implicitly this means that anyone mourning the loss of a loved one may be at risk for being called mentally ill.”

Similarly, Frances notes that anyone who feasts on food just once in a month is a candidate to be diagnosed with a binge eating disorder. Other controversial changes, he adds, include the removal of Asperger syndrome and the addition of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (essentially, temper tantrums), the latter added to combat the growing “epidemic” of child bipolar disorder.

But Dr. David J. Kupfer, chair of the DSM-5 Task Force, dismissed suggestions that the forthcoming revisions were a case of diagnostic inflation run amok. “We have sought to be conservative in our approach to revising DSM-5. Our work has been aimed at more accurately defining mental disorders that have a real impact on people’s lives, not expanding the scope of psychiatry,” he stated in an APA press release (www.psych.org/File%20Library/Advocacy%20and%20Newsroom/Press%20Releases/2012%).

The manual will include approximately the same number of disorders that were included in DSM-IV. But Frances argues that having an equivalent number of disorders to previous editions is a moot point, as often broader definitions allow any manner of symptoms to be classified under the rubric of one disorder or another. “The new DSM-V is built on dimensional and spectrum assessment. These definitions have not yet been field-tested, we have no idea what the impact will be on rates of mental illness, or who will now get medicated,” he notes.

McIntyre isn’t convinced that anything positive will come out of the new psychiatric bible. “Phenomenological revisions are stale,” he says. “I think it was premature to put out a revision at this time.”

Will it ultimately prove to be the equivalent of four blind men describing an elephant? Without an understanding of how the brain works, or what causes mental illness, how do we know we are not just describing different symptom complexes of the same disease?

“We don’t,” Frances responds. “And in fact, each expert has the tendency to inflate the part of the elephant (he/she) studies. To me, it is clear the world would be a better place if we were still using the DSM-III.”