Abstract

In developing an vivo drug-interception therapy to treat cocaine abuse and hinder relapse into drug seeking provoked by re-encounter with cocaine, two promising agents are: 1) a cocaine hydrolase enzyme (CocH) derived from human butyrylcholinesterase and delivered by gene transfer: 2) an anti-cocaine antibody elicited by vaccination. Recent behavioral experiments showed that antibody and enzyme work in a complementary fashion to reduce cocaine-stimulated locomotor activity in rats and mice. Our present goal was to test protection against liver damage and muscle weakness in mice challenged with massive doses of cocaine at or near the LD50 level (100 to 120 mg/kg, i.p.). We found that, when the interceptor proteins were combined at doses that were only modestly protective in isolation (enzyme, 1 mg/kg; antibody, 8 mg/kg), they provided complete protection of liver tissue and motor function. When the enzyme levels were ~ 400-fold higher, after in vivo transduction by adeno-associated viral vector, similar protection was observed from CocH alone.

1. INTRODUCTION

In vivo drug-interception by antibodies or enzymatic destruction is emerging as a potential treatment for substance abuse, with the concept of preventing addiction relapse in recovering users who re-encounter their particular drug of choice [1, 2]. Cocaine abuse is a promising target because cocaine is subject to one-step enzymatic inactivation, and because a cocaine vaccine has already shown some success in a clinical trial [3]. We are investigating a cholinesterase-derived cocaine hydrolase (CocH) for possible synergy with anti-cocaine antibodies, since both agents reduce the drug’s access to brain. Enzymes destroy limitless quantities in time, while antibodies bind rapidly but can be saturated by large or repeated drug doses. These complementary properties led to the idea that combined treatments would be particularly efficient [4]. In theory, when both agents are present, antibody can sequester part of a drug bolus while enzyme hydrolyzes free molecules. As the equilibrium shifts, drug will off-load from the antibody to be destroyed in turn, restoring the original state. Thus, these agents might act synergistically to shield the brain (reducing addiction liability) and also protect peripheral tissues, such as liver, that are direct targets of cocaine toxicity [5-7]. We recently presented supportive behavioral evidence for this idea [8]. The current study was designed to extend those observations by determining whether anti-cocaine antibody and cocaine hydrolase would also cooperate to reduce the toxic effects of cocaine in mice, with particular respect to muscle impairment and liver damage. Here we present key findings from initial experiments on the potential for additive or synergistic therapeutic effects from CocH and anti-cocaine antibodies.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Drug Source

Cocaine HCl was obtained from NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda MD). Purified CocH, a quadruple mutant of human butyrylcholinesterase (A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G) first reported by Pan et al [9] and characterized further by Yang et al [10], was obtained in the form of a C-terminal fusion with human serum albumin (D. LaFleur, Cogenesys Inc.) from clonal lines of stably transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells. The enzyme was purified on DEAE Sepharose followed by ion exchange chromatography as previously described [11] and stored at −80°C until used.

2.2 Animals

Balb/c male mice obtained at 6 to 7 weeks of age from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Madison WI) were housed in plastic cages with free access to water and food (Purina Laboratory Chow, Purina Mills, Minneapolis, MN, USA) in rooms controlled for temperature (24 °C), humidity (40-50%), and light (light/dark, 12/12-h with lights on at 6:00 a.m.). The animal use protocol (A4309) was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Care and Use Committees. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care in laboratories accredited by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

2.3 Antibody and vaccine

Anti-cocaine antibodies with sub-micromolar affinity and 8100-1 KLH SNC vaccine (norcocaine hapten-conjugated keyhole limpet hemocyanin) were prepared at Baylor College of Medicine as previously described [12]. The vaccine was injected at a volume of 80 μl into the upper thigh of each hind leg, in a total dose of 100 μg/mouse. After three weeks the same dose was given as a booster immunization. To determine levels of specific anti-cocaine antibodies, a ~ 50 μl blood sample was taken from each mouse, plasma was obtained after centrifugation, and diisopropylfluorophosphate (10−5 M) was added to inactivate cocaine hydrolysis. Samples were then incubated 50 min with 3H-cocaine in near saturating concentration (5 μM), 50 μl aliquots were centrifuged on a Centricon Sepharose spin-column at 1000 × g for 4 min, and 30 μl of the void volume fraction was mixed for scintillation counting in 4 ml “BioSafe” fluor (RPI Inc, Mt Prospect IL). Validation experiments showed that > 80% of the sample protein (including IgG with bound cocaine) passed into the collection tube, while >98% of free cocaine remained on the column. Assay signals (counts per min) were linearly proportional to IgG concentration over a wide range and were calibrated with reference to a known quantity of purified anti-cocaine IgG run alongside the test samples.

2.4 Drug and protein injections

Cocaine HCl was delivered i.p. (100 mg/kg or 2 doses of 60 mg/kg spaced 10 min apart). Protein pretreatments, 2 hr prior to cocaine, were: a) CocH, 1 mg/kg or b) cocaine antiserum equivalent to 8 or 16 mg/kg anti-cocaine IgG. Delivery was initially i.v. but, where indicated (see Results) later experiments used i.p. injection as it was less stressful and yielded similar plasma levels at the time of cocaine injection. Blood samples (< 100 μl) were collected at appropriate times from the tail vein. Plasma was separated by centrifugation for 10 min at 8000 g and then immediately used for enzyme determinations or stored at −20° C pending analysis.

2.5 Viral gene transfer

Gene transfer utilized an adeno-associated viral vector, pAAVio-CASI-CocH C-W-SV40 provided by Drs. Alejandro B Balazs and David Baltimore, Cal. Tech, Pasadena CA). This vector was modified to incorporate cDNA for C-terminally truncated CocH (enzyme sequence only, lacking the final 52 residues). The AAV8 virus was then prepared by co-transfecting this vector along with pHelper and pAAV2/8 vectors, provided by Dr. Stephen J. Russell at Mayo Clinic, into HEK293T cells. Viral genome copy numbers were determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QPCR) assays using a forward primer targeting upstream viral DNA and a reverse primer targeting the N-terminal region of the CocH (human butyrylcholinesterase) sequence. Vector delivery was accomplished by rapid injection of 1013 viral genome copies through the tail vein in an initial volume of 0.1 ml followed by 0.1 ml of 0.9% sterile NaCl solution.

2.6 Grip strength and functional observations

After cocaine challenge locomotor activity and gait were assessed with a functional observational battery, and muscle strength was measured with a strain gauge (model GS3, BIOSEB, Vitrolles Cedex, France). Body weight, determined before testing because of possible effects on the outcome, did not differ among treatment groups. For strength determinations mice were held by the tail above the wire grid of the apparatus, gently lowered until all four legs grasped the grid, and then pulled away along the horizontal axis. Maximal achieved force was displayed and recorded. The procedure was repeated three times on each test day, and mean peak force was used for statistical analysis.

2.7 Liver function and pathology

To assess liver status, plasma alanine transaminase activity (ALT) was measured by the method of Bergmeyer et al. [13 ] using a kit from Thermo Scientific (Middletown, VA) with positive and negative controls. For postmortem pathology mice were euthanized with sodium pentobarbital 200 mg/kg (“Sleepaway”, Fort Dodge Animal Health, IA) followed by intracardial perfusion with 50ml isotonic NaCl. Livers were then harvested and stored at −80 degrees C. Frozen sections (14 μm) were later cut on a Leica cryostat and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) according to standard procedures [14]. Areas of lobular necrosis were traced and analyzed with the NIH Image-J image-processing program by an observer blinded to treatment conditions.

2.8 Statistics

Statistical significance was evaluated by ANOVA with Fisher’s PLSD as a post-hoc test.

3. RESULTS and DISCUSSION

3.1 Protection of muscular strength and function

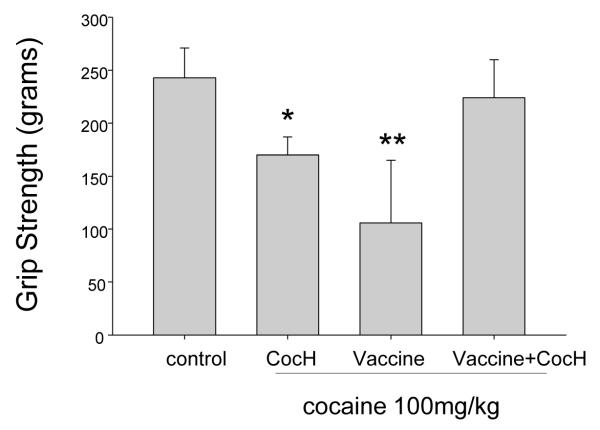

Low doses of cocaine provide at least subjective enhancement of motor performance [15], but high doses impair it and are directly toxic to skeletal muscle [16]. We examined whether treatment with CocH or anti-cocaine vaccine would preserve hind limb grip strength in mice given high-dose cocaine (100 mg/kg, i.p.). Unprotected mice were not tested because this cocaine dose was near the LD50 [17]. Either enzyme or vaccine treatment allowed all mice to survive the cocaine challenge, but at the doses delivered neither by itself was able to prevent reduced grip strength (Fig 1). Combined treatment in identical amounts, however, fully protected muscle function, at least by this measure, and also prevented tremors and other outward signs of dysfunction seen in singly treated mice. These encouraging results warrant further studies with other muscle biomarkers and a histological analysis in order to confirm our tentative conclusion that muscle toxicity was completely abrogated.

Fig. 1.

Grip strength after cocaine challenge. Indicated treatments are: control (n = 10, saline, i.p.), CocH (n = 8, enzyme, 1 mg/kg i.p.), vaccine (n = 10, see Methods), and vaccine plus CocH (n = 10). All pretreatments except vaccine were delivered 1 hr before the drug challenge (100 mg/kg i.p.). Four-paw grip strength was determined 20 min after cocaine administration (units are grams). Animals with no pretreatment did not survive. Statistical significance: * (p < 0.01 vs control and vaccine + CocH); ** (p < 0.001 vs control and vaccine + CocH).

3.2 Protection against cocaine induced liver damage

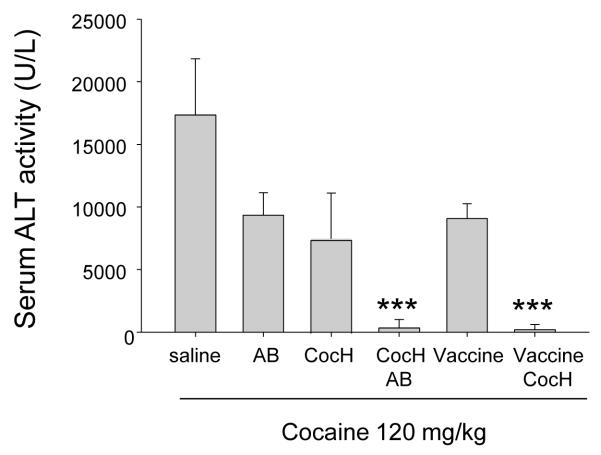

As cocaine is hepatotoxic, especially in mice [18, 19], it was important to determine whether gene transfer with hepatotropic viral vectors would enhance or reduce liver toxicity. As a biochemical marker of liver damage we measured plasma levels of the hepatic enzyme, alanine transaminase (ALT). Mouse plasma ALT activity rises dramatically after toxic insults from high levels of cocaine and is a reliable surrogate for chemical-induced hepatic necrosis [20]). In order to determine the effectiveness of anti-cocaine antibodies and cocaine hydrolase against a major toxic challenge, we obtained blood samples before and 24 hours after a still larger dose of cocaine (120 mg/kg). A pilot study established that this dose was not lethal when administered as two separate 60 mg/kg injections10-min apart, though it caused profound prostration. Before cocaine exposure, plasma ALT levels ranged from 10 to 18 U/ml in all groups. Twenty-four hr after exposure, unprotected mice showed levels more than 1000-fold higher (Fig 2). Pretreatment 3 hr before with modest doses of antibody (8 mg/kg, i.p.) or CocH (1 mg/kg, i.p.) reduced the surge of marker-enzyme activity by about half (p < 0.01). Remarkably, however, mice with CocH plus antibody, or CocH plus vaccination, showed almost no rise of plasma ALT after the cocaine overdose. This enhanced outcome was taken as a sign of synergistic therapeutic action.

Fig. 2.

Cocaine-induced liver dysfunction. Plasma ALT activity was determined 24 hr after challenge with 120 mg/kg cocaine, i.p (two 60-mg/kg doses 10 min apart). Pretreatment groups were: saline (n = 5), and (n = 8 for all) antibody (AB, 16 mg/kg), enzyme (CocH, 1 mg/kg), vaccine, enzyme plus antibody (CocH + AB) and enzyme plus vaccine (CocH + vaccine). ALT activity in each of the double-treatment groups (CocH + AB and CocH + vaccine) was significantly lower than in all other groups *** (p < 0.0001).

Complementary antibodies were not necessary in 4 AAV-vector-treated mice, which were tested in a follow up experiment. At the time of testing, 3 months after initial treatment, cocaine hydrolase activity in these mice averaged 145 ± 20 U/ml, approximately 400 times higher than measured 3 hr after delivering CocH, 1 mg/kg, by direct injection (0.37 ± 0.2 U/ml). Vector by itself caused no measurable change in baseline ALT activity, which was 14 ± 2 U/ml in the treated mice versus 16 ± 2.7 U/ml in untreated controls. That outcome is already noteworthy because viral gene copies accumulated to substantial levels in the liver, driving very high local enzyme production. More strikingly, the vector-treated mice gave no external response to the massive cocaine exposure, and ALT activity in the 24-hr plasma sample remained at 15 ± 2.4 U/ml, vs 18,000 ± 1500 U/ml in the unprotected animals. In short, the treated animals resembled control mice not given cocaine.

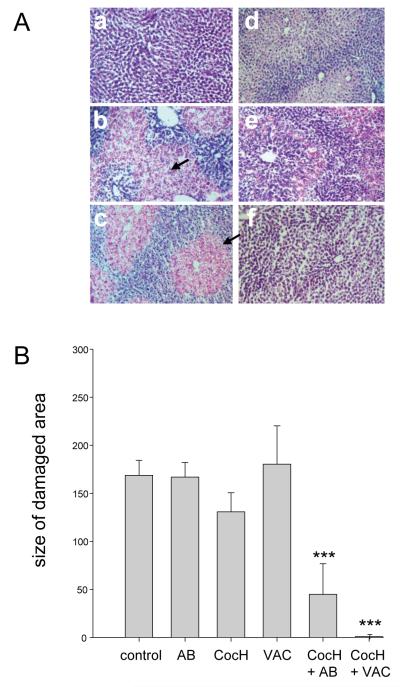

In order to confirm the completeness of protection against cocaine hepatotoxicity, we euthanized mice 24 hr after their cocaine challenge and took postmortem liver samples (vector-treated animals were not included). Histological examination of frozen sections (Fig 3A) yielded a qualitative picture completely in line with the ALT data. Thus, in H&E stains, control samples showed uniformly healthy tissue, while samples from unprotected mice given cocaine showed pervasive centrilobular foci of necrosis crowded with pale and swollen hepatocytes. The extent of necrosis appeared slightly reduced in animals pretreated with any single one of the three interception agents, CocH, AB, anti-cocaine vaccine, but objective morphometry of the histological material showed no significant reduction in the area of damage (Fig. 3B). On the other hand, livers from mice given CocH in addition to cocaine-AB or vaccine were both qualitatively and quantitatively normal. Hence, combined delivery of these two proteins appeared to protect hepatic structure fully.

Fig. 3.

Liver Pathology. A) H&E-stained liver sections from control mice (a), and mice given cocaine, 120 mg/kg, after the following pretreatments: b) none; c) anti-cocaine antibody; d) anti-cocaine vaccine; e) CocH; f) CocH + vaccine. Arrows indicate red-stained areas of centrilobular necrosis. B) Quantitative analysis of histological outcomes: cross sectional areas of damaged zones in arbitrary units (mean ± SEM, n = 5-8). Statistical significance: *** p < 0.001 vs all “no-asterisk” groups.

These results are consistent with the existing literature on cocaine toxicity. There is evidence that cocaine-induced hepatotoxicity in rodents and humans involves the production of norcocaine by cytochrome P450 and its subsequent conversion to nitroxide metabolites [21]. This hepatotoxicity is known to be exacerbated by agents that inhibit esterases [21]. Delivery of an exogenous esterase such as CocH might therefore be beneficial for two reasons: 1) by diverting cocaine from p450-based metabolic pathways, and 2) by rapidly hydrolyzing norcocaine generated by those pathways and preventing the accumulation of its reactive nitroxides.

The present results have favorable implications for a proposed cocaine-abuse therapy based on delivering an efficient hydrolase, especially in combination with anti-cocaine antibody. A logical means of sustaining such delivery over the long term needed for recovery would be by cocaine-hapten vaccination together with viral gene transfer of cocaine-metabolizing enzyme. Much additional research is needed, but we regard these findings as grounds for thinking that such treatments will not directly induce musculoskeletal or hepatic toxicity nor will they predispose to tissue damage after frankly myotoxic or hepatotoxic doses of cocaine. Instead, they appear likely to reduce or eliminate such adverse outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Drs D. Baltimore and S. J. Russell for generously providing crucial viral vectors for this research. Our work was supported by NIDA grants DP1 DA031340, R01 DA023979, and R01 DA023979 S1, and by Mayo Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Brimijoin S, Gao Y. Cocaine hydrolase gene therapy for cocaine abuse. Future Med Chem. 2012;4:151–62. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Brimijoin S. Interception of cocaine by enzyme or antibody delivered with viral gene transfer: a novel strategy for preventing relapse in recovering drug users. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2011;10:880–91. doi: 10.2174/187152711799219398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Martell BA, Orson FM, Poling J, Mitchell E, Rossen RD, Gardner T, et al. Cocaine vaccine for the treatment of cocaine dependence in methadone-maintained patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:1116–23. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gao Y, Orson FM, Kinsey B, Kosten T, Brimijoin S. The concept of pharmacologic cocaine interception as a treatment for drug abuse. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;187:421–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Shuster L, Quimby F, Bates A, Thompson ML. Liver damage from cocaine in mice. Life Sci. 1977;20:1035–41. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(77)90291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Perino LE, Warren GH, Levine JS. Cocaine-induced hepatotoxicity in humans. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:176–80. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kanel GC, Cassidy W, Shuster L, Reynolds TB. Cocaine-induced liver cell injury: comparison of morphological features in man and in experimental models. Hepatology. 1990;11:646–51. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840110418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Carroll ME, Zlebnik NE, Anker JJ, Kosten TR, Orson FM, Shen X, et al. Combined Cocaine Hydrolase Gene Transfer and Anti-Cocaine Vaccine Synergistically Block Cocaine-Induced Locomotion. PLoS One. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043536. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pan Y, Gao D, Yang W, Cho H, Yang G, Tai HH, et al. Computational redesign of human butyrylcholinesterase for anticocaine medication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16656–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507332102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yang W, Xue L, Fang L, Chen X, Zhan CG. Characterization of a high-activity mutant of human butyrylcholinesterase against (−)-cocaine. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;187:148–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gao Y, LaFleur D, Shah R, Zhao Q, Singh M, Brimijoin S. An albumin-butyrylcholinesterase for cocaine toxicity and addiction: catalytic and pharmacokinetic properties. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;175:83–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Orson FM, Kinsey BM, Singh RA, Wu Y, Kosten TR. Vaccines for cocaine abuse. Hum Vaccin. 2009;5:194–9. doi: 10.4161/hv.5.4.7457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bergmeyer HU, Scheibe P, Wahlefeld AW. Optimization of methods for aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase. Clin Chem. 1978;24:58–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pearse AD. Histochemistry, Theoretical and Applied. Churchill-Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wagner JC. Abuse of drugs used to enhance athletic performance. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1989;46:2059–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Elnenaei MO, Heneghen MA, Moniz C. Life-threatening hyperkalaemia and multisystem toxicity following first-time exposure to cocaine. Ann Clin Biochem. 2012;49:197–200. doi: 10.1258/acb.2011.011095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Borchard RE, Barnes CD, Eltherington LG. Drug Dosage in Laboratory Animals, A Handbook. Telford Press; Caldwell, New Jersey: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shuster L, Garhart CA, Powers J, Grunfeld Y, Kanel G. Hepatotoxicity of cocaine. NIDA Res Monogr. 1988;88:250–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Evans MA, Harbison RD. Cocaine-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1978;45:739–54. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(78)90167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ramaiah SK. A toxicologist guide to the diagnostic interpretation of hepatic biochemical parameters. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:1551–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ndikum-Moffor FM, Roberts SM. Cocaine-protein targets in mouse liver. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:105–13. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]