Abstract

Background

The low level of response (LR) to alcohol is an endophenotype that predicts future heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders (AUDs). LR can be measured by laboratory-based alcohol challenges or by the retrospective Self-Report of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE) questionnaire. This paper reports the relationships among these two measures and how each related to both recent and future drinking quantities and problems across 15 years in 235 men.

Methods

Probands from the San Diego Prospective Study (SDPS) participated in alcohol challenges to determine their LR at age 20, and subsequently at ages 35, 40, 45 and 50 filled out an SRE regarding the number of standard drinks needed for up to four effects early in life (SRE5) and across early, recent, and heaviest drinking life epochs (SRET). Changes in SRE scores across time were evaluated with ANOVAs and Pearson correlations were used to evaluate how SRE5, SRET and earlier alcohol challenge-based LRs related to prior five-year drinking histories and future alcohol involvement.

Results

While SRE scores decreased 9% over the 15 years, the relationships between SRE values with prior five-year drinking parameters and with future alcohol intake and problems remained robust, and even improved with advancing age. A similar pattern was seen for correlations between SRE and alcohol challenge-based LRs 15 to 30 years previously.

Conclusions

Alcohol challenge and SRE-based LRs related to each other, to alcohol use patterns, and to future alcohol problems across age 35 to 50 in the men studied here.

Keywords: alcohol, alcohol sensitivity, alcohol course, predictors

1. INTRODUCTION

A low level of response (LR) to alcohol is one of the more extensively studied of the preexisting phenotypes that predispose a person toward alcohol problems (Ehlers et al., 2010; Morean and Corbin, 2010; Newlin and Renton, 2010; Quinn and Fromme, 2011; Ray et al., 2011). Early evaluations of LR used challenges with alcohol where changes from baseline to a given blood alcohol concentration (BAC) were documented through alterations in hormones, electrophysiology, motor performance, and subjective feelings of intoxication (Schuckit, 2009; Schuckit and Gold, 1988). Lower responses to alcohol were seen in groups at high risk for future alcohol use disorders (AUDs), including those with a family history of AUDs, Native Americans and Koreans, while high LRs have been observed in groups with lower vulnerabilities toward alcohol problems, including Jewish subjects and Asian individuals with the alcohol-related flush (Duranceaux et al., 2006, 2008; Ehlers et al., 2004; Garcia-Andrade et al., 1997; Luczak et al., 2011; Monteiro et al., 1991). All longitudinal studies to date have reported that low LR’s documented through alcohol challenges predicted later heavy drinking and alcohol problems (e.g., Heath et al., 1999; Schuckit and Smith, 1996; Volavka et al., 1996).

Alcohol challenges, however, are labor intensive, costly, and can only be implemented in healthy nonalcoholic subjects old enough to give informed consent (Ehlers et al., 2010; Schuckit et al., 1997a, b). To expand the number and diversity of individuals who can be evaluated for LR, our group developed the 12-item Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE) Questionnaire where subjects estimate the number of standard (10–12 gm of ethanol) drinks required to produce up to four effects they actually experienced at three different epochs of their lives (Schuckit et al., 1997a, b). The most often used SRE timeframes include estimations regarding the approximate first five times of consuming at least one full alcoholic drink (SRE5), and a SRE total value (SRET) that combines SRE5 with scores for the periods of heaviest drinking and recent three months. Compared to SRET, SRE5 depends solely on a person’s recollection of alcohol effects in the more distant past, and incorporating information from more recent alcohol experiences broadens the perspective the individual brings to the SRET evaluation. Higher SRE scores, indicating a lower LR per drink, have been documented among heavier drinkers as young as age 12, individuals with higher current and past alcohol problems, and those with family histories of AUDs (Daeppen et al., 2000; Kalu et al., 2012; Pederson and McCarthy, 2003; Ray et al., 2009, 2011; Schuckit and Smith, 2004; Schuckit et al., 1997a,b, 2006, 2008, 2009a). Correlations of SRE5 values with drinking quantities over the subsequent one to five years have ranged between .20 and .41, and with alcohol problems or AUDs .21 and .28 (Chung and Martin, 2009; Schuckit et al., 2007, 2008, 2009b).

Alcohol challenge-based and SRE-based LR values overlap 60% in predicting alcohol outcomes (Schuckit et al., 2009a, b), and operate similarly when used to identify low and high LR subjects for further study (Trim et al., 2010). Furthermore, SRE- and alcohol challenge-generated LRs operate similarly when placed in the context of additional risk factors predicting outcomes in structural equation models (Schuckit et al., 2010, 2011). When the same individuals were given alcohol challenges and retrospective SREs at the same time, with correlations between the two LR measures of > −.20, a finding generally consistent with correlations and beta weights reported in another evaluation in the literature (Pederson and McCarthy, 2009; Schuckit et al., 2009b).

Only one study evaluated whether SRE values changed significantly as individuals aged (Schuckit and Smith, 2004), and none have determined how SRE scores at different times related to recent drinking characteristics and predicted future alcohol intake and problems. That prior study documented a 6% decrease in SRE values (an increase in LR per drink) over five years, reflecting a general increase in sensitivity to this depressant drug as people age (Kalant, 1998; Lynskey et al., 2003; Schuckit and Smith, 2004). However, no data were available regarding the relationships of the age-related alterations in SRE values to current or future drinking.

To expand upon the earlier work, the current study presents data on SRE values over a 15-year period, along with information regarding the correlations between SRE scores and recent drinking-related parameters, and future outcomes over time. Based on the prior studies, we hypothesized that: 1) the SRE scores will be relatively stable over time, with only a small decrease in the number of drinks needed for effects with age; 2) as the time increases between filling out the SRE and the actual first five times of drinking and a prior alcohol challenge, the relationship of the SRE to current drinking parameters and the alcohol challenge will diminish; however, 3) the relationship between SRE values and future drinking-related outcomes over the 15 years of follow-up will be robust enough to remain significant for both SRE5 and SRET.

2. METHODS

2.1 Subjects

These evaluations focused on 235 probands from the San Diego Prospective Study (SDPS) who participated in all follow-up evaluations at 15 years (T15), 20 years (T20), 25 years (T25) and 30 years (T30) after their baseline (T1) alcohol challenge protocol at about age 20 (Schuckit and Smith, 2011). As shown below, these men represent the large majority of the 65% of subjects who were eligible to date for follow-up at the 30 year epoch in the prospective study. Subjects had originally been chosen as matched pairs of men who were family history positive and negative for AUDs from among respondents to questionnaires distributed each year to students and non-academic staff at our university between 1978 and 1988. Drinking but not alcohol-dependent 18-to-25-year-old White males with no lifetime substance dependence and no significant current medical or psychiatric disorders were asked to participate in an alcohol challenge to evaluate their LR to alcohol. Subjects received oral alcohol (e.g., 0.75 ml/kg as a 20% solution with a sugar free carbonated beverage with a peak BAC of ~.06 g/dL) and a placebo session, with the drinks consumed over 10 minutes through a straw that passed through a 1 ml reservoir of absolute alcohol attached to a closed container (Mendelson et al., 1984; Schuckit and Gold, 1988; Schuckit and Smith, 1996). The intensity of their alcohol response was evaluated using their subjective feelings of intoxication, alcohol-related changes in cortisol, and alterations in body sway (e.g., Schuckit and Gold, 1988). The results of each test were converted to z-scores and combined into an overall LR based on the changes from baseline to the usual time of the peak BAC at about 60 minutes after drinking.

2.2 Procedures

The men were subsequently followed up with semi-structured interviews at T15 (98% of surviving subjects), T20 (97%), T25 (94%), and T30 (an estimated 90%). Evaluations of outcomes used interviews originally based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) and modified for additional diagnostic systems using the subsequent Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA) interview (Bucholz et al., 1994; Hesselbrock et al., 1999; Spitzer et al., 1992). Information was extracted at each follow-up regarding the usual and maximum number of standard drinks consumed per occasion during the ~five-year follow-up interval, the number of 22 possible alcohol problems reported to have occurred during that period, and whether the person met criteria for DSM-IV alcohol abuse or dependence during the epoch (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The problems included the 11 DSM-IIIR and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence items along with non-diagnostic problems such as alcohol-related blackouts and job or marital problems.

Beginning at T15 (the evaluation for which the SRE had first been developed), at each follow-up subjects filled out this retrospective report to generate SRE5 and SRET scores (Cronbach α >.90, 2-to-12-month reliabilities of .6 to .8; Ray and Hutchison, 2009; Schuckit et al., 1997a, b). They were asked to relate the number of standard drinks required for each of up to 4 effects (first feeling effects, slurring speech, impairing coordination, and passing out) actually experienced during the approximate first five times of drinking, with the average drinks across effects used for SRE5. The SRET score included SRE5 along with scores for the life epoch of heaviest alcohol consumption, and the most recent three months.

2.3 Analyses

Data analyses evaluated the pattern of SRE5 and SRET across the four time points for all 235 men from T15 through T30 using repeated measures ANOVAs. SRE values were corrected for outliers and some analyses focused on the subset of subjects in the upper and lower thirds of SRE scores, as small deviations from the mean of LR do not offer as clear information regarding future drinking outcomes (Schuckit and Smith, 1996; Schuckit et al., 2010, 2012b). The relationships of these SRE5 and SRET values to the most recent five-year pattern of drinking and related problems and to the alcohol challenge LR from ~age 20 were evaluated with Pearson Product-Moment correlations. Similar correlations were used to study the link between T15 SRE values and outcomes over the subsequent 15 years between T15 and T30; T20 SRE scores as predictors of the outcomes over the subsequent 10 years; as well as SRE scores from T25 as predictors of alcohol-related outcomes during the subsequent five years. Simultaneous multiple regression analyses were then used to evaluate how well the baseline alcohol challenge LR and the earliest SRE values gathered at T15 predicted the range of alcohol quantities and problems across the 15 years of T15 to T30.

3. RESULTS

The ages for the 235 White male probands at each follow-up from T15 to T30 were 37.1 (SD = 3.02), 41.8 (3.06), 46.8 (3.20), and 51.4 (3.72), respectively, and by T30 they had completed an average of 17.6 (2.16) years of education. Reflecting the selection criteria used at T1 (Schuckit and Gold, 1988), about half (49.4%) of these probands had a father or mother with an AUD (41.7% of fathers and 15.3% of mothers). Across the 15 years from T15 to T30, the subjects reported 3.1 (2.38) drinks per drinking day on average, 9.0 (5.79) maximum drinks per occasion, and 59.6% gave a history of one or more of the 22 possible alcohol-related problems, with an average of 2.6 (3.98) problems per individual. For these SDPS probands, 39.6% fulfilled criteria for an AUD during their follow-up, including 24.3% with dependence and 15.3% with alcohol abuse only.

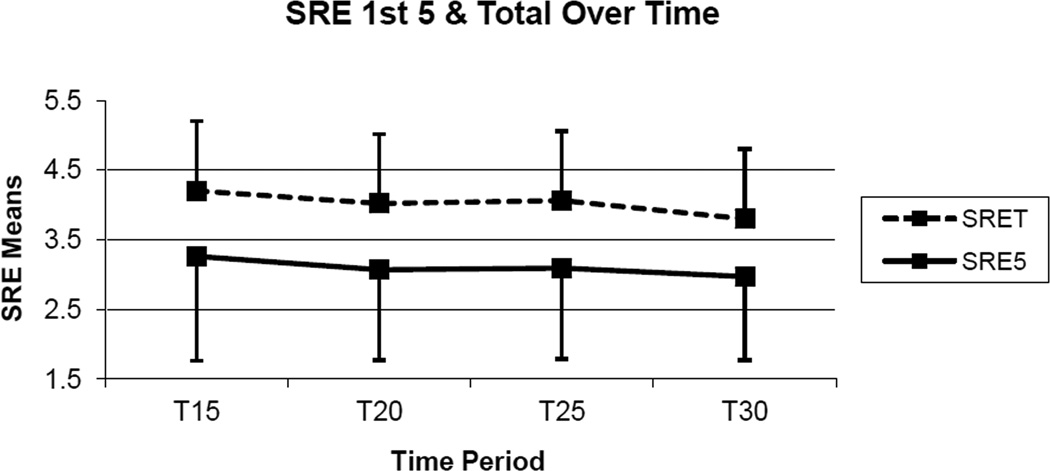

Figure 1 demonstrates the SRE5 and the SRET scores over time for the full sample of 235 men. From T15 through T30 the SRE5 average scores were 3.3 (1.49), 3.1 (1.34), 3.1 (1.32), and 3.0 (1.16) (Time effect: F = 4.00, p <.008). The SRET values across those same time points were 4.2 (1.70), 4.0 (1.61), 4.1 (1.72), and 3.8 (1.41) (Time effect: F = 7.74, p <.001). Thus, both SRE5 and SRET scores decreased slightly over time, indicating the individual’s perception as they grew older that fewer drinks had been required for effects (i.e., they perceived more effect per drink) the first few times of drinking as well as for their SRET that included more recent timeframes. However, the change over the 15 years was a relatively modest ~9% for both SRE measures. The average correlation between SRE5 values across the four time points were .50 (p <.001), and for the SRET were .75 (p <.001).

Figure 1.

SRE5 (SRE first 5 or estimate of the standard drinks required for up to four effects the approximate first five times of drinking) and SRET (SRE Total representing SRE5 and SRE values for the recent three months and period of heaviest drinking) mean values with one direction standard deviation bars for each of the 5-year follow-up evaluations at T15 (15 years; age 37.1), T20 (20 years; age 41.8), T25 (25 years; age 46.8), and T30 (30 years; age 51.4).

Table 1 presents the results of evaluations of how the SRE5 and SRET values at each time point correlated with the prior five-year drinking parameters and with the T1 alcohol challenges for the subjects in the upper and lower thirds on SRE values. The number of subjects in these groups varied between 158 and 159 across epochs as a reflection of the SRE cut points for upper and lower thirds on SRE scores at each timeframe. Regarding the subjects in the middle third of the SRE values who were not included in these analyses, their SRE5 and SRET scores were similar to the average across the combined upper and lower thirds of subjects in Table 1. The excluded subjects were not significantly different from the remaining men on demography, substance use, or family histories. All the correlations for SREs with alcohol-related variables were in the positive direction, indicating that the need for a greater number of drinks for effects (a lower LR per drink) was related to higher alcohol intake, problems, and rates of AUDs. At T15, the SRE5 correlations to alcohol variables ranged from .15 (p=.06) to .24; at T20 and T25 correlations ranged from .10 to .24; and T30 values were between .29 and .35. For the SRET the cross-sectional relationships with adverse alcohol characteristics ranged from .29 to .53. The data at the bottom of the table report the correlations of the two SRE values at each time point with the alcohol challenge LR results from ~age 20. Despite the passage of 15 to 30 years, all correlations for SRE5 and SRET with the original alcohol challenge were in the predicted negative direction (a need for more drinks for effects on the SRE reflects a lower response at a set BAC on alcohol challenges). For SRE5 these ranged from −.08 to −.22, while for SRET values were between −.19 and −.32. While not shown in Table 1, the SRE scores did not correlate significantly with a subject’s endorsement of tolerance. The data were re-evaluated after excluding individuals who met criteria for an AUD during a relevant follow-up period, with results that were similar to those shown in the table.

Table 1*.

Correlations of SRE5 and SRET Values across T15-T30 with Prior 5-Year Drinking Quantities, Problems, and Diagnoses and with T1 Alcohol Challenge LR

| SRE5 | SRET | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | T15 | T20 | T25 | T30 | T15 | T20 | T25 | T30 |

| Quant Usual Maximum |

.16a .24a |

.18a .19a |

.18a .24b |

.29c .35c |

.29c .41c |

.39c .49c |

.37c .48c |

.44c .52c |

| # Probs | .15t | .20b | .10 | .33c | .29c | .47c | .40c | .48c |

| AUD | .16a | .21a | .21b | .30c | .33c | .45c | .47c | .53c |

| T1 Challenge | −.11 | −.08 | −.22b | −.18a | −.19b | −.21b | −.32c | −.24c |

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

SRE5 = Level of response (LR) to alcohol measured by the Self Report of the Effects of Alcohol questionnaire for ~first 5 times drinking; SRET = Level of response to alcohol measured by the Self Report of the Effects of Alcohol questionnaire averaged for ~first 5 times drinking, the life epoch of heaviest alcohol consumption, and the most recent 3 months; Quant = quantity as number of standard drinks in a day (24-hour period); Usual = usual number of drinks; Maximum = maximum number of drinks; #Probs = number of 22 alcohol problems (11 DSM-IIIR and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence items along with 11 non-diagnostic items); AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder of abuse or dependence; T1 Challenge = baseline (~age 20) alcohol challenge LR results; T15, T20, T25, and T30 = following T1 baseline assessment, the time periods of about 15, 20, 25, and 30 years.

Table 2 evaluates the prediction of alcohol outcomes across 15 years by T15 SREs, predictions across 10 years for T20 SREs, and across five years by T25 SREs, with all correlations in the positive direction. For the T15 SRE5 predicting outcomes over the next 15 years, correlations with alcohol quantities and problem outcomes ranged from .12 to .18, T20 SRE5 correlations with later outcomes ranged from .12 to .21, while correlations for the T25 prediction of T30 outcomes ranged from .15 (p = .06) to .29. For SRET, correlations were more robust (from .29 to .53).

Table 2*.

Correlations of SRE5 and SRET Values across T15-T30 and of T1 Alcohol Challenge LR with Future Drinking Quantities, Problems, and Diagnoses

| SRE5 | SRET | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | T1 Challenge | T15 | T20 | T25 | T15 | T20 | T25 |

| Quant Usual Maximum |

−.19a −.25b |

.12 .13 |

.12 .16a |

.15t .16a |

.22b .34c |

.34c .41c |

.39c .44c |

| # Probs | −.19a | .16a | .17a | .18a | .28c | .42c | .45c |

| AUD | −.18a | .18 a | .21a | .29c | .33c | .43c | .48c |

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

See legend for Table 1. Additionally here, the T1 Challenge column presents correlations between the alcohol challenge LR values from age 20 and alcohol outcomes during the 15 years between T15 and T30; the two T15 columns present correlations between SRE5 or SRET and outcomes over the 15 years between T15 and T30; the two T20 columns present correlations between SRE5 or SRET at T20 and the outcomes over the 10 years between T20 and T30; the T25 columns present the correlations between SRE5 or SRET and the 5 years to T30 outcomes.

To place the SRE values into perspective, the first column of Table 2 presents the correlations of the T1 alcohol challenge LR values with the alcohol outcomes across the combined T20, T25, and T30 follow-ups. These correlations ranged from −.18 to −.25, and all were significant. Finally regarding Table 2, when individuals who met criteria for an AUD in the relevant time period were excluded from the analyses, the results for the nonalcoholic subjects regarding alcohol outcomes looked similar to those reported in Table 2, or were even a bit higher.

The data in Table 3 evaluate how the SRE5 and SRET values at T15 and the alcohol challenge scores from T1 functioned when combined in a series of simultaneous-entry multiple regression analyses relating to the four alcohol-related outcomes (usual and maximum quantities, alcohol problems, and AUDs) across T20 to T30. As expected, the relationships of SRE to all four outcomes were positive and the sign for alcohol challenges were all negative in valence. For SRE5, R2 values, or the proportion of the variance explained, ranged from .04 to .07; SRE5-associated β weights in the equations were from .10 to .17; while alcohol challenge-related β weights ranged from −.17 to −.23. For SRET, R2s were between .07 and .15; SRET-associated β weights were from .20 to .31; while alcohol challenge-related β weights ranged from .12 to .19.

Table 3*.

Simultaneous Entry Multiple Regressions Regarding How T15 SRE and T1 Alcohol Challenge Results Related to Alcohol Characteristics across the Next 15 years [T20,T25,T30] (β weights**)

4. DISCUSSION

These analyses assessed SRE5 and SRET values every five years over 15 years from the same subjects, and related those results to drinking characteristics both cross-sectionally and prospectively. The findings support two of the three original hypotheses, and offer insights into some attributes of the SRE that may be useful to both researchers and clinicians.

Consistent with Hypothesis 1 and with a prior short-term follow-up (Schuckit and Smith, 2004), the SRE5 and SRET values were fairly stable over 15 years, with both scores decreasing slightly with increasing age, perhaps reflecting the subjects’ more recent alcohol experiences and their need for fewer drinks for effects as they grew older (Kalant, 1998). Thus, while the SRE may be sensitive to additional life experiences, those effects may be relatively small, and are of similar magnitude for SRE5 and SRET. The latter finding might reflect the incorporation of SRE5 scores into SRET. Thus, the core of the relationship of SRE-based LR results to drinking parameters remained intact over the years.

Regarding Hypothesis 2, contrary to our projection of a decreasing relationship of SRE scores with recent drinking parameters as subjects age, the reverse pattern was observed. For SRE5, the correlations with past five-year alcohol quantities, problems and AUD diagnoses were more, rather than less, robust at T30 than at T15. Increases in correlations from T15 to T30 were also observed for SRET, and the relationships with drinking parameters were higher for the total SRE than for SRE5. This differential may relate to the fact that SRET considers more time points than SRE5, including the recent three-month period which might have partially reflected recent acquired tolerance for some subjects. While Hypothesis 2 also projected a decrease across time for relationships of the SRE to the alcohol challenge LR values from T1, those correlations were actually higher at T25 and T30 than at T15.

There are several possible reasons for these higher correlations with drinking parameters and age-20 alcohol challenges as subjects grew older. These improved relationships might reflect a person’s more extensive experience with alcohol with age, with resulting more accurate insights into their early drinking experiences. Or, perhaps subjects became more familiar with the SRE questions with each subsequent interview, and gave greater thought to what their sensitivity to alcohol had actually been earlier in life. It is also possible that at age 35 (T15) these male subjects were more likely to think about their earlier alcohol experiences with a tinge of bravado regarding how well they were able to “handle their liquor” as young men compared to their reflections at age 50 (T30).

Similar to relationships observed in prior studies (Schuckit et al., 1997b, 2009b), SRE5 and SRET values at T25 and T30 correlated with alcohol challenge LRs at −.20, underscoring the fact that the SRE and alcohol challenge measures appear to be two overlapping, but not identical, aspects of LR. The lack of perfect concordance may reflect the fact that the alcohol challenges directly measure how intensely a person responds to alcohol in a laboratory setting at closely monitored BACs, while the SRE asks them to recall their overall general response across what were likely to be many actual drinking experiences at different epochs of their lives. Both LR measures relate to recent drinking, both predict later heavier alcohol consumption and related problems, both LR values appear to be genetically influenced (Dick et al., 2006; Ehlers et al., 2010; Hinkers et al., 2006; Hu et al, 2005; Joslyn et al., 2010; Kramer et al., 2008), but alcohol challenge and SRE-based LRs do not reflect identical phenomena.

The results in Table 2 support Hypothesis 3 that the SRE values will continue to predict alcohol-related adverse outcomes as subjects age. Here, SRE5 values at T15 predicted more alcohol problems and a greater probability of carrying an AUD diagnosis over T20, T25, and T30 follow-ups, with similar results regarding the ability of T20 and T25 SRE5 to predict the subsequent 10- and five-year outcomes. Similar patterns were seen for maximum drinks, although these were only significant at T20 and T25. Predictions based on SRET were all significant and were greater in magnitude than for the SRE5. Thus, not only did a lower LR per drink as indicated by the SRE maintain its ability to predict more adverse alcohol outcomes as these men grew older, but, as was seen with cross-sectional relationships of SRE scores to alcohol-related parameters, the predictions became more robust with advancing age. The latter could reflect the shorter period of time inherent in the T20 and T25 predictions compared to T15, or the greater level of experience with alcohol that went into the SRE estimates with advancing age. Also, as was reported in a recent paper where a low LR from alcohol challenges predicted even late onset AUDs (Schuckit and Smith, 2011), the alcohol challenge results from age 20 in Table 2 significantly predicted all four adverse alcohol outcomes over the period between age 35 and 50.

The results in Table 3 address more about how SRE and alcohol challenge LR values overlap regarding future drinking parameters. When both T15-based SRE5 scores and T1 alcohol challenge results were entered into regressions predicting the outcomes across T20 through T30, the R2s were a modest .04 to .07, but all were significant. Alcohol-related outcomes are affected by many things, including changes in jobs and relationships as well as health concerns and medical treatment, and explaining ~5% of the variance across 15 years is noteworthy. Regarding regressions that included SRE5, alcohol challenge values significantly contributed to each outcome, while SRE5 contributed to future AUD status, with a trend (β = .14, p <.09) for alcohol problems. For regressions that included SRET, R2 values were higher (.07 to .15) and the SRE contributed to all four regressions with alcohol challenge values contributing significantly to regressions for maximum drinks, with trends for usual drinks (β = −.15, p=.054) and problems (β = −.14, p=.07). Thus, the two SRE and alcohol challenge-based LRs appear to complement each other in their ability to predict alcohol outcomes, with both measures often contributing significantly to regressions.

These analyses have some potential implications for research and clinical settings, as well as for prevention efforts (Schuckit et al., 2012a). Researchers may benefit from the finding that the SRE is tapping upon an important risk factor for future adverse alcohol outcomes throughout adulthood, and that there is no evidence that the information associated with this questionnaire diminishes greatly between age 35 (T15) and age 50 (T30). It is also important to recognize that studies may benefit from including both alcohol challenge and SRE measures of LR in their protocol whenever possible, as the genes and environmental factors associated with each could vary, and more research is required to flush out such potential differences. The data also raise the possibility that clinicians may find that the simple and inexpensive SRE questionnaire might be useful as a correlate and predictor of future alcohol problems in their patients. Thus, while more study is needed, perhaps the SRE might be used to identify patients likely to have current alcohol problems, even when they are reluctant to report the problematic drinking itself.

The results presented here must be considered in light of our methods. The caveats include the fact the subjects were all well educated White males, half of whom had a family history of AUDs. Thus, the generalizability of the current results to other population groups needs to be established. It is also important to note that the SRE questionnaire had not been developed until these subjects were in their mid thirties, and it will be useful to evaluate how the SRE performs in similar analyses when the form is filled out by younger subjects followed over several decades. In these analyses the SRE scores were corrected for outliers, and only subjects with clearly low and high LR scores were used in some analyses, so it is well to keep in mind that selecting subjects at the extremes of the scores has the potential of inflating correlations. In addition, the low LR is only one of several alcohol reaction measures, and there are other important phenotypes regarding future alcohol problems that were not studied here, including those that relate to impulsivity and associated characteristics, and preexisting psychiatric disorders (Newlin and Renton, 2010; Schuckit, 2009; Yip et al., 2012).

Acknowledgements

Funding Source: Funding for this study was provided in by NIAAA grant R01 AA005526. NIAAA had no role in neither the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, the writing of the report, nor the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors: Both authors materially contributed to the manuscript and participated in the research.

Conflict of Interest: Neither author has any conflict of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: APA; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Reich T, Schmidt I, Schuckit MA. A new semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Martin CS. Subjective stimulant and sedative effects of alcohol during early drinking experiences predict alcohol involvement in treated adolescents. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:660–667. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daeppen J-B, Landry U, Pécoud, Decrey H, Yersin B. A measure of the intensity of response to alcohol to screen for alcohol use disorders in primary care. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35:625–627. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.6.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Plunkett J, Wetherill LF, Xuei X, Goate A, Hesselbrock V, Schuckit M, Crowe R, Edenberg HJ, Foroud T. Association between GABRA1 and drinking behaviors in the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism sample. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2006;30:1101–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duranceaux NCE, Schuckit MA, Eng ME, Robinson SK, Carr LG, Wall TL. Associations of variations in alcohol dehyrogenase genes with the level of response to alcohol in non-Asians. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2006;30:1470–1478. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duranceaux NCE, Schuckit MA, Luczak SE, Eng MY, Carr LG, Wall TL. Ethnic differences in level of response to alcohol between Chinese Americans and Korean Americans. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:227–234. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Gizer IR, Schuckit MA, Wilhelmsen KC. Genome-wide scan of self-rating of the effects of alcohol in American Indians. Psychiatr. Genet. 2010;20:221–228. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32833add87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Phillips E, Wall TL, Wilhelmsen K, Schuckit MA. EEG alpha and level of response to alcohol in Hispanic- and non-Hispanic-American young adults with a family history of alcoholism. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2004;65:16–21. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Andrade C, Wall TL, Ehlers CL. The firewater myth and response to alcohol in Mission Indians. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1997;154:983–988. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Dinwiddie SH, Slutske WS, Bierut LJ, Rohrbaugh JW, Statham DJ, Dunne MP, Whitfield JB, Martin NG. Genetic differences in alcohol sensitivity and the inheritance of alcoholism risk. Psychol. Med. 1999;29:1069–1081. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbrock MN, Easton C, Bucholz KK, Schuckit M, Hesselbrock V. A validity study of the SSAGA—a comparison with the SCAN. Addiction. 1999;94:1361–1370. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinckers AS, Laucht M, Schmidt MH, Mann KF, Schumann G, Schuckit MA, Heinz A. Low level of response to alcohol as associated with serotonin transporter genotype and high alcohol intake in adolescents. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006;60:282–287. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Oroszi G, Chun J, Smith TL, Goldman D, Schuckit MA. An expanded evaluation of the relationship of four alleles to the level of response to alcohol and the alcoholism risk. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2005;29:8–16. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000150008.68473.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joslyn G, Ravindranathan A, Brush G, Schuckit M, White RL. Human variation in alcohol response is influenced by variation in neuronal signaling genes. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2010;34:800–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalant H. Pharmacological interactions of ageing and alcohol. In: Gomberg ESL, Hegedus AM, Zucker RA, editors. Alcohol Problems and Ageing. Res. Mono. No. 33. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1998. pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kalu N, Ramchandani VA, Marshall V, Scott D, Ferguson C, Cain G, Taylor R. Heritability of level of response and association with recent drinking history in nonalcoholic-dependent drinkers. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2012;36:522–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luczak SE, Pandika D, Shea SH, Eng MY, Liang T, Wall TL. ALDH2 and ADH1B interactions in retrospective reports of low-dose reactions and initial sensitivity to alcohol in Asian American college students. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011;35:1238–1245. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Day C, Hall W. Alcohol and other drug use disorders among older-aged people. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2003;22:125–133. doi: 10.1080/09595230100100552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson JH, McGuire M, Mello NK. A new device for administering placebo alcohol. Alcohol. 1984;1:417–419. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(84)90014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro MG, Klein JL, Schuckit MA. High levels of sensitivity to alcohol in young adult Jewish men: a pilot study. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1991;52:464–469. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, Corbin WR. Subjective response to alcohol: a critical review of the literature. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2010;34:385–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlin DB, Renton RM. High risk groups often have higher levels of alcohol response than low risk: the other side of the coin. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2010;34:199–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen SL, McCarthy DM. An examination of subjective response to alcohol in African Americans. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:288–295. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Fromme K. Subjective response to alcohol challenge: a quantitative review. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011;35:1759–1770. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LA, Hart EJ, Chin PF. Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE): predictive utility and reliability across interview and self-report administrations. Addict. Behav. 2011;36:241–243. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LA, Hutchison KE. Associations among GABRG1, level of response to alcohol, and drinking behaviors. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2009;33:1382–1390. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. An overview of genetic influences in alcoholism. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2009;36:S5–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Edenberg HJ, Kalmijn J, Flury L, Smith TL, Reich T, Beirut LJ, Goate A, Foroud T. A genome-wide search for genes that relate to a low level of response to alcohol. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2001;25:323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Gold EO. A simultaneous evaluation of multiple markers of ethanol/placebo challenges in sons of alcoholics and controls. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1988;45:211–216. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800270019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Kalmijn JA, Smith TL, Saunders G, Fromme K. Structuring a college alcohol prevention program on the low level of response to alcohol model: a pilot study. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2012a;36:1244–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. An 8-year follow-up of 450 sons of alcoholic and control subjects. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1996;53:202–210. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. Changes over time in the self-reported level of response to alcohol. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:433–438. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. Onset and course of alcoholism over 25 years in middle class men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP, Pierson J, Hesselbrock V, Bucholz KK, Kramer J, Kuperman S, Dietiker C, Brandon R, Chan G. The ability of the Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE) scale to predict alcohol-related outcomes five years later. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:371–378. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP, Trim R, Bucholz KK, Edenberg HJ, Hesselbrock V, Kramer JJ, Dick DM. An evaluation of the full level of response to alcohol model of heavy drinking and problems in COGA offspring. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2009a;70:436–445. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Heron J, Hickman M, Macleod J, Lewis G, Davis JM, Hibbeln JR, Brown S, Zuccolo L, Miller LL, Davey-Smith G. Testing a level of response to alcohol-based model of heavy drinking and alcohol problems in 1,905 17-year-olds. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011;35:1897–1904. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Tipp JE. The Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE) form as a retrospective measure of the risk for alcoholism. Addiction. 1997a;92:979–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Trim R, Fukukura T, Allen R. The overlap in predicting alcohol outcome for two measures of the level of response to alcohol. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2009b;33:563–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00870.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Trim RS, Heron J, Horwood J, Davis J, Hibbeln J ALSPAC Study Team. The Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol Questionnaire as a predictor of alcohol-related outcomes in 12-year-old subjects. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:641–646. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Trim RS, Tolentino NJ, Hall SA. Comparing structural equation models that use different measures of the level of response to alcohol. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2010;34:861–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Waylen A, Horwood J, Danko GP, Hibbeln JR, Davis JM, Pierson J. An evaluation of the performance of the Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol Questionnaire in 12- and 35-year-old subjects. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2006;67:841–850. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Tapert S, Matthews SC, Paulus MP, Tolentino NJ, Smith TL, Trim RS, Hall S, Simmons A. fMRI differences between subjects with low and high responses to alcohol during a stop signal task. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2012b;36:130–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01590.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Smith TL, Wiesbeck GA, Kalmijn J. The relationship between self-rating of the effects of alcohol and alcohol challenge results in ninety-eight young men. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1997b;58:397–404. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MD. The structured clinical interview for DSM-IIIR (SCID) Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trim RS, Simmons AN, Tolentino NJ, Hall SA, Matthews SC, Robinson SK, Smith TL, Padula CB, Paulus MP, Tapert SF, Schuckit MA. Acute ethanol effects on brain activation in low- and high-level responders to alcohol. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2010;34:1162–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volavka J, Czobor P, Goodwin DW, Gabrielli WF, Jr, Penick EC, Mednick SA, Jensen P, Knop J, Schulsinger F. The electroencephalogram after alcohol administration in high-risk men and the development of alcohol use disorders 10 years later: preliminary findings. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1996;53:258–263. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030080012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip SW, Doherty J, Wakeley J, Saunders K, Tzagarakis C, de Wit H, Goodwin GM, Rogers RD. Reduced subjective response to acute ethanol administration among young men with a broad bipolar phenotype. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1808–1815. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]