Abstract

The bacteriophage P22 virion is assembled from identical coat protein monomers in a complex reaction that is generally conserved among tailed, double-stranded DNA bacteriophages and viruses. Many coat proteins of dsDNA viruses have structures based on the HK97 fold, but in some viruses and phages there are additional domains. In the P22 coat protein a “telokin-like” domain was recently identified, whose structure has not yet been characterized at high-resolution. Two recently published low-resolution cryo-EM reconstructions suggest markedly different folds for the telokin-like domain, that lead to alternative conclusions about its function in capsid assembly and stability. Here we report 1H, 15N, and 13C NMR resonance assignments for the telokin-like domain. The secondary structure predicted from the chemical shift values obtained in this work shows significant discrepancies from both cryo-EM models but agrees better with one of the models. In particular, the functionally important “D-loop” in one model shows chemical shifts and solvent exchange protection more consistent with β-sheet structure. Our work will set the basis for a high-resolution NMR structure determination of the telokin-like domain that will help improve the cryo-EM models, and in turn lead to a better understanding of how coat protein monomers assemble into the icosahedral capsids required for virulence.

Keywords: capsid, procapsid, virus assembly, icosahedron, extra-density domain, D-loop

The capsid assembly process of P22, a bacteriophage that infects Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, serves as a model for higher-order dsDNA viruses such as Herpesviruses. In P22, the T=7 capsid is composed of 415 identical coat protein monomers, a dodecameric portal complex, and other minor proteins. To assemble the metastable procapsid, coat protein monomers copolymerize with scaffolding proteins in a nucleation-limited reaction. In order for the mature virus to be generated, the DNA must be packaged, a process during which the coat protein subunits undergo a conformational rearrangement to form the faceted architecture of the virion. Concomitantly, the scaffolding proteins exit and are recycled. Finally, the DNA is stabilized within the capsid by plug proteins, and the tailspikes and tail needle are attached (Johnson 2010, Teschke and Parent 2010).

Two independently-derived models of the P22 procapsid and capsid based on cryo-EM reconstructions have shown that the conserved HK97-fold forms the core of the coat protein structure (Chen et al. 2011, Parent et al. 2010). These independent models both identified an additional domain called the “telokin-like (TL) domain” (Parent et al. 2010) or alternatively the “extra-density domain” (Chen et al. 2011). While the two cryo-EM models agree for the core HK97 structure, the “extra” TL-domain unique to the P22 coat protein shows marked differences between the models. The differences in the models have lead to divergent interpretations of the TL-domain’s biological function. In the model of Chen et al. (2011), based on a cryoreconstruction computed to 4 Å resolution, a large segment containing a high density of positively charged residues called the “D-loop” (residues 257–277) within the TL-domain, was suggested to make inter-capsomer contacts with a pocket of negative charges in an adjacent coat protein monomer of the procapsid and mature virion. These charge interactions were hypothesized to provide additional thermodynamic stability to the assembled structure (Chen et al. 2011) in lieu of the crosslinks or auxiliary proteins which serve this role in many other viruses and phages (Parent et al. 2010). By contrast, in the model of Parent et al. (2010), based on a cryoreconstruction computed to 8 Å resolution, the TL-domain is hypothesized to be the folding nucleus and contribute to the stability of the coat protein monomers (Teschke and Parent 2010).

The TL-domain appears to be functionally important because the majority of the mutations that cause a temperature-sensitive folding phenotype in coat protein, are localized to this part of the molecule (Teschke and Parent 2010, Chen et al. 2011). Furthermore, the TLdomain has been implicated in size determination of P22 phage capsids (Suhanovsky and Teschke 2011). The resonance assignments reported herein set the foundation for NMR structural studies, that will resolve the role of the TL-domain in the assembly and stability of bacteriophage P22 virions.

Experimental Procedures

Expression and purification

The gene encoding amino acids S223-V345, corresponding to the TL-domain from the coat protein of bacteriophage P22, was cloned into a pET30b plasmid (Novagen, Madison, WI). A His6 metal affinity tag for purification was inserted before the recombinant gene followed by a thrombin cut site (LVRPG). The sequence of the designed gene was confirmed by Genewiz (South Plainfield, NJ).

Recombinant TL-domain was expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3). Cells were grown at 37 °C to mid-log phase, in M9 media containing 40 µg/mL kanamycin. Protein expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 16 hours at 30 °C. Isotopic labels were incorporated by growing the cells in M9 minimal media supplemented with 3g/L 13C-glucose and/or 1g/L 15NH4Cl. (Cambridge Isotopes, Andover, MA).

After induction the cells were harvested by sedimentation at 8000 rpm in a Sorvall SLC-6000 rotor for 20 minutes. The cells were disrupted by resuspension in 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.6) containing 0.1% w/v Triton X-100, lysozyme (200 µg/mL), and a 1:100 dilution of EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), followed by lysis using a French press operating at 20000 psi. The lysate was brought to 5 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM PMSF, and treated with DNase and RNase (100 µg/mL each) for 30 min to digest nucleic acids. Cell debris was removed by sedimentation in a Sorvall F18-12x50 rotor at 18500 rpm for 30 minutes. The supernatant was loaded onto a Talon metal-affinity column (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) for purification of the TL-domain via the engineered N-terminal His6-tag. Fractions containing the TL-domain were pooled and dialyzed three times against 20 mM phosphate, pH 7.6. The protein was precipitated with ammonium sulfate at 4° C, and the fraction between 45% and 57.5% saturation was saved. The His6-tag was removed by overnight digestion with human thrombin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 25 °C, using 2U thrombin/mg in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2 buffer at pH 8.4. The thrombin was removed using p-aminobenzamidine agarose as described by the manufacturer (Sigma St. Louis, MO). The purified TL-domain was dialyzed three times against 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), and concentrated using a Centricon 10K nominal molecular weight cut-off filter from Millipore (Billerica, MA).

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR experiments were performed on 1.5 mM protein samples dissolved in 90% H2O /10% D2O or 99.8% D2O, buffered to pH 6.0 with sodium phosphate, and containing 0.2% w/v sodium azide. Typically, 300 µL sample volumes contained in Shigemi microcells were used for NMR experiments. Spectra were recorded at a temperature of 37 °C on a 600 MHz Varian INOVA spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic probe. The data were processed using the FELIX-NMR program (San Diego, CA) and analyzed with CCPNmr Analysis (Vranken et al. 2005). Proton signals were referenced against DSS. Carbon and nitrogen signals were referenced indirectly as described in the literature (Wishart et al. 1995b).

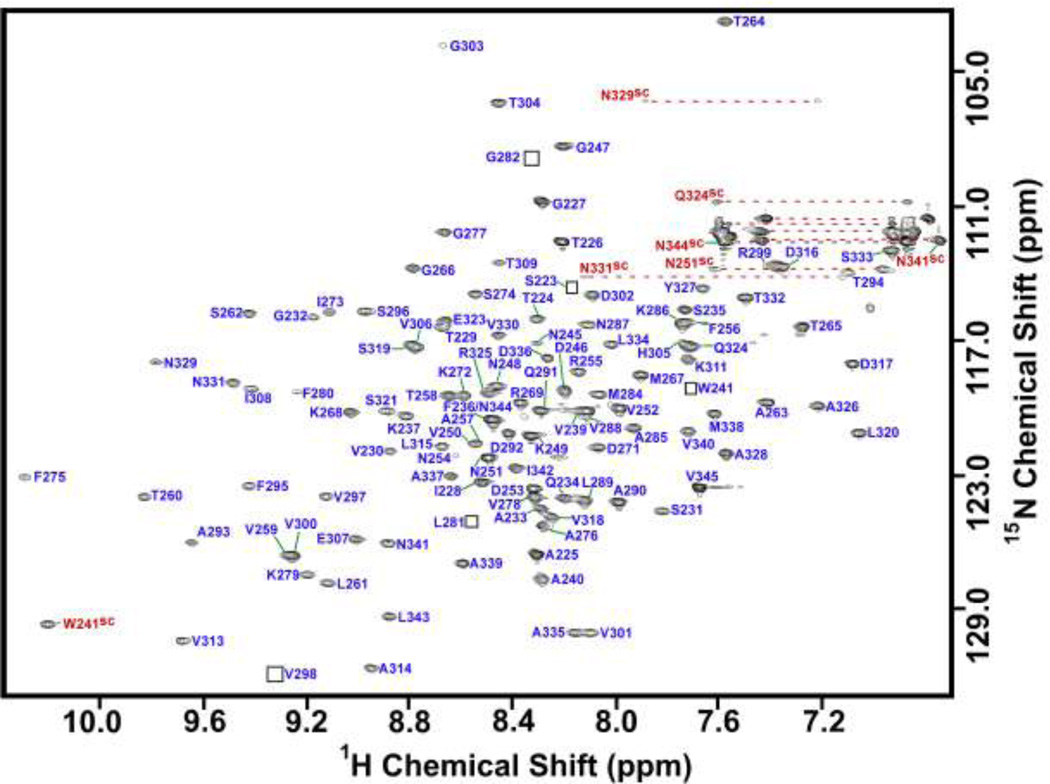

Resonance assignments (Figure 1) were obtained from 2-D and 3-D NMR experiments (Cavanagh et al. 1996) implemented from the Varian ProteinPack software suite. The 3D HNCACB/HNCA/HN(CO)CA and HNCO/HN(CA)CO sets of triple-resonance experiments were used to obtain non-redundant sequential connectivities for the backbone nuclei. Aliphatic side-chain assignments were made using 1H-15N TOCSY-HSQC, HNHA, HNHB, H(CCO)NH, and C(CO)NH spectra. Stereo-specific resonance assignments for methylene carbons were obtained using a 1H-15N TOCSY-HSQC, HNHB, and a short 50 ms mixing time 2-D NOESY experiment (Case et al. 1994). Aromatic resonances were assigned using 2-D 1H-13C HSQC, 1HDFQ-COSY, 1H-TOCSY, and 1H-NOESY data. Side-chain amide groups were assigned using intra-residue NOE peaks in a 1H-15N NOESY-HSQC.

Figure 1.

Assigned 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of the TL-domain. The spectrum was collected on a 1.5 mM sample of the TL-domain in 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, at a temperature of 37 °C. The amino acid sequence numbering scheme is that of the full-length P22 coat protein. Backbone resonance assignments are indicated in blue and side chain amide resonances with red labels and the superscript SC. Peaks that are visible only at lower contour levels than shown are indicated by squares.

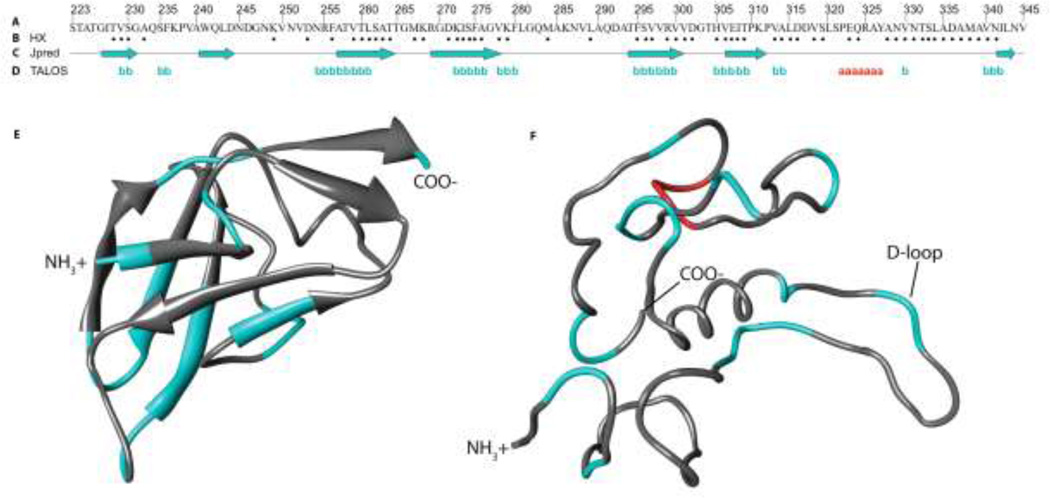

To obtain information on the secondary structure of the TL-domain (Figure 2), we calculated φ and ψ dihedral angles using Talos+ program (Cornilescu et al. 1999) and identified amide protons protected from hydrogen-deuterium solvent exchange. The secondary structure limits delineated by the NMR data agree with the secondary structure predicted by the Jpred-PSSM program (Cole et al (2008), with two exceptions (Fig. 2). The segment from residues 240–245 is found to be in a β-strand by the Jpred-PSSM secondary structure prediction program but the NMR data for this segment is subject to conformational exchange broadening and we are missing assignments for three residues in this region. The segment 323–327 has NMR chemical shifts consistent with α-helical structure but no secondary structure preference was identified by the Jpred-PSSM program. The NMR-derived secondary structure shows differences from both of the cryo-EM models of the TL-domain (Parent et al 2010, Chen et al 2011) but agrees better with the model of Parent et al. (2010). A functionally important difference is that the D-loop in the model of Chen et al. (2011), shows 14 amide protons protected from solvent exchange and chemical shifts consistent with β-sheet secondary structure based on our NMR data, suggesting this segment is unlikely to be in a loop (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Secondary structure of the TL-domain (A) The amino acid sequence of the TL-domain. (B) Amide protons protected from exchange after 2 h in D2O (dots). (C) Secondary structure prediction using the Jpred-PSSM program (Cole et al 2008). (D) Secondary structure calculated with the Talos+ program (Cornilescu et al 1999) based on the backbone chemical shift assignments reported in this work. (E) The cryo-EM model of Parent et al. (2010) for amino acids 229–315 only, colored according to the Talos+ results. Arrows are drawn for the regions assigned to b-strands in the cryo-EM model. (F) The cryo-EM model of Chen et al. (2011), colored according to the Talos+ results. TheChen et al. (2011) structure is a Ca-only model, and no information on secondary structure is available. For both models regions predicted by the Talos+ analysis to be in b-strands are colored in cyan, a-helix in red, and segments for which no prediction was made in grey.

Assignments and Data Deposition

Backbone assignments of the 123-residue TL-domain were achieved to greater than 95% completion. NMR signals from five residues (242Q, 243L 244D, 270G, and 283Q) could not be detected. Most likely, the signals from these residues are broadened by µs-ms conformational exchange processes. Using the statistics generated by Analysis (Vranken et al. 1995) 82% of all protons, 71% of all carbons, and 73% of all nitrogens were assigned. The chemical shifts have been deposited in the BioMagResBank (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu) under BMRB accession number 18566.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01GM076661 to C.M.T. and its supplement to C.M.T. and A.T.A. S.R.S. was supported by a NSF-GRFP fellowship.

Footnotes

Ethical standards

All experiments complied with all laws of the United States of America

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Case DA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Use of chemical shifts and coupling constants in nuclear magnetic resonance structural studies on peptides and proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1994;239:392–416. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)39015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh J, Fairbrother WJ, Palmer AG, III, Skelton NJ. Protein NMR spectroscopy principles and practice. 2nd edn. Elsevier Inc; Amsterdam: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE. Virus particle maturation: insights into elegantly programmed nanomachines. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen DH, Baker ML, Hyrc CF, DiMaio F, Jakana J, Weimin W, Dougherty M, Haase-Pettingell C, Schmid MF, Jiang W, Baker D, King J, Chiu W. Structural basis for scaffolding-mediated assembly and maturation of a dsDNA virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1355–1360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015739108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole C, Barber JD, Barton GF. The Jpred 3 secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W197–W201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent KN, Khayat R, Tu LH, Suhanovsky MM, Cortines JR, Teschke CM, Johnson JE, Baker TS. P22 coat protein structures reveal a novel mechanism for capsid maturation: stability without auxiliary proteins or chemical crosslinks. Structure. 2010;18:390–401. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhanovsky MM, Teschke CM. Bacteriophage p22 capsid size determination: roles for the CP telokin-like domain and the scaffolding protein amino-terminus. Virology. 2011;417:418–429. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teschke CM, Parent KN. ‘Let the phage do the work’: Using the phage P22 coat protein structures as a framework to understand its folding and assembly mutants. Virology. 2010;401:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vranken WF, Boucher W, Stevens TJ, Fogh RH, Pajon A, Llinas M, Ulrich EL, Markley JL, Ionides J, Laue ED. The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins. 1995;4:687–696. doi: 10.1002/prot.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart DS, Bigam CG, Holm A, Hodges RS, Sykes BD. 1H, 13C and 15N random coil NMR chemical shifts of the common amino acidsIInvestigations of nearest-neighbor effects. J Biomol NMR. 1995a;5:67–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00227471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart DS, Bigam CG, Yao J, Abildgaard F, Dyson HJ, Oldfield E, Markley JL, Sykes BD. 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift referencing in biomolecular NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00211777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]