Abstract

The study examined the efficacy of a brief theory-based counseling intervention to reduce sexual HIV risk behaviors among STI clinic patients in St. Petersburg, Russia. Men and women (n=307) were recruited to receive either: (1) a 60-minute motivational/skills-building counseling session dealing with sexual HIV risk reduction, or (2) written HIV prevention information material. Participants completed baseline and three- and six-month assessments in the period between July 2009 and May 2011. Compared to the control group, the face-to-face counseling intervention showed significant increases in the percentage of condom use and consistent condom use, and significant decreases in the number of unprotected sexual acts and frequency of drug use before sex at three-months follow-up. Intervention effects dissipated by six months. The brief counseling intervention may effectively reduce HIV sexual risk behaviors and enhance protective behaviors among STI clinic patients in Russia. Short-term positive effects were achieved with a single one hour counseling session.

Keywords: STI clinic patients, sexual HIV prevention intervention, randomized controlled trial, brief counseling intervention, sexual risk reduction, HIV risk reduction

INTRODUCTION

Russia’s HIV epidemic is one of the worst in Europe and Central Asia. Although the HIV prevalence among the general population remains below 1% [1], the number of officially registered people with HIV increased from 1,000 to more than 438,000 from 1996 to 2008 [2]. In one report, the number of newly diagnosed HIV infection cases and the number of deaths due to HIV-related causes during 2009 were estimated to be approximately 67,000 and 35,000, respectively [3]. To date, the majority of HIV cases in Russia have been diagnosed among injection drug users [3]. However, the proportion of cases reporting heterosexual contact as the only exposure increased from 6% in 2001 to 25% in 2004 [4] and has steadily increased since 2004 [5, 6]. Thus, concerns about a sexual spread of HIV to a non-drug using population [5, 7] have made the development of interventions to reduce levels of sexual risk behaviors in populations vulnerable to HIV of greater public health importance in Russia.

The current study is an initial efficacy test of a counseling intervention designed to reduce HIV sexual risk behaviors grounded in the Information-Motivation-Behavior (IMB) model [8] and adapted for use among Russian STI clinic patients. The IMB theory of behavioral change has been shown to successfully promote the adoption of protective sexual behaviors and the reduction in HIV risk behaviors among STI clinic patients in different countries such as South Africa and the United States [9, 10] but has not been tested among STI clinic patients in Russia. This model has the advantage of having a theoretical frame that can be individually tailored to highlight a population’s underlying risk factors that may promote and reinforce sexual risk behaviors, such as substance use and alcohol misuse.

The use of an intervention model that allows for the inclusion of components to addresses substance use is important given the diversity of risk behaviors presented by the population targeted in this study, which may or may not consume alcohol, inject drugs or use other substances. For example, in studies conducted at two STI clinics in St. Petersburg, a small proportion (usually below five percent) of the participants self reported injection drug use [11, 12]. Another study among non injectors whose sexual partners injected drugs in St. Petersburg, Russia revealed a prevalence of 11% of methamphetamine use consumed in non injectable form, which was associated with unprotected sex among participants [13]. Although a study in an STI clinic revealed a proportion of 11% of participants abstaining from alcohol [14], up to 50% showed evidence of alcohol misuse [14], and the misuse of alcohol may play a role sexual risk behaviors that place individuals at risk for HIV in Russia [15], such as having multiple sexual partners [13, 15] and engaging in unprotected sex [13, 16].

The exercises for proper condom use were also a relevant factor for the choice of the intervention model. Studies in Russia show low rates of STI preventive and contraceptive behavior among a female general population where the proportion of women who report having had an abortion may reach 50% or more [17–19]. Rates of unprotected sex at last sexual intercourse can reach 70% among people at high risk for HIV, such as sexual partners of IDUs [13], and in a study of female STI clinic patients who reported having casual or multiple sexual partners in the prior three months, 26% claimed to “never have used condoms” during that time period [16]. While condoms may provide protection against STIs and unwanted pregnancies, they are only effective when used consistently and correctly; this highlights the importance of using an intervention model which allows for condom use skills building exercises.

The study was conducted in a public STI clinic of the city of St. Petersburg, Russia. HIV is prevalent throughout Russia, but a relatively small number of regions suffer a disproportionately high official incidence of HIV [20]. While the incidence of HIV infection in the Russian Federation grew three times, from 13.5 to 40.8 per 100,000 people from 1999 to 2009, the incidence of HIV in the Leningrad region increased more than 25 times, from 3.2 to 86.0 per 100,000 during this period [21]. St. Petersburg is part of the Leningrad region, where the HIV epidemic is considered the third highest among the 83 federal territories of the Russian Federation [21]. With a population of nearly five million people, it was considered a suitable site to conduct a randomized clinical trial to test the potential efficacy of an HIV sexual risk reduction counseling intervention.

The main hypothesis of this intervention trial was that the brief HIV prevention counseling intervention would demonstrate significant improvement in safer practices (greater proportion of condom use, and more frequent consistent condom use) and reduction in sexual risk behaviors (fewer sexual partners, fewer unprotected sexual acts) compared to the controlled condition.

METHODS

Participants and setting

The study was conducted among patients receiving services at a public STI clinic located at the Kalininsky district of St. Petersburg, Russia. The city is comprised of 18 districts, and nearly all contain a public STI clinic. These clinics provide services free of charge or for a nominal fee to local residents. This clinic was chosen as the study site because the Kalininsky district, with more than 500,000 residents, is the second largest district of the city of St. Petersburg in terms of population size. Also, the clinic is convenient to reach and had space available to rent for the study.

Recruitment procedures

The study activities occurred between July 2009 and May 2011. Potential participants were STI patients referred by the STI physician to participate in a prevention study that involved a single counseling session and complete baseline and follow-up assessments over a period of six months. All patients who had seen an STI physician were referred to the study staff, including patients seeking STI counseling, testing and/or treatment, whether or not they reported STI symptoms or were diagnosed with an STI. The eligibility criteria included being 18 years or older, having two or more sexual partners or at least one casual partner in the three months prior to the interview, having had unprotected sex with at least one of these partners, and planning to stay in the city over the next seven months. Although all patients seeking STI counseling or care are potentially at risk for STI/HIV, patients who consistently used condoms or who only had one main sexual partner were excluded from participation because they would have little benefit from a study focusing on reducing the number of sexual partnerships they enter into and on increasing their condom use (the two main outcomes of the study). Potential participants were informed of the purpose of the study and were assured that the study was confidential and voluntary. Signed informed consent was obtained for the patients who agreed to participate. Both of the institutional review boards (the Biomedical Center in St. Petersburg, Russia and Yale University in Connecticut, United States) approved the study.

Participant randomization, study treatments, and data collection

Patients elected to enroll in the study were scheduled for, and completed, a computerized baseline assessment performed with individual assistance and a single counseling session. All measures were administered in Russian. Assessment staff members were blinded to the study conditions. Subjects were assigned randomly to either (a) a written HIV prevention information control group or (b) a single one hour face-to-face HIV and alcohol-related risk reduction skills intervention group.

Participants were followed-up at three and six months after baseline assessment. All participants received a gift certificate of 500 rubles (equivalent to approximately 17 USD) and a package containing condoms, lubricants and HIV/STI information sheets after completing each of the assessments (baseline, and then three and six months). Participants were not paid for their time in counseling sessions. No adverse event occurred due to participation in the study.

The control condition

The control group received the same written HIV prevention information material as was provided to the intervention group. These study information materials are usually not provided to patients receiving STI care and were disseminated to participants to ensure that they at least received some enhanced health information for being part of the study. The written information material included descriptive information about HIV/STI prevalence and transmission risks in Russia, measures to prevent HIV/STI transmission, and instructions for proper condom use.

HIV risk reduction intervention

An adapted version of a social cognitive model of health behavior change was used as the theoretical framework for the risk reduction skills intervention developed and tested in this research [9, 22]. Specifically, a one hour risk reduction counseling intervention for use with STI clinic patients was translated and culturally adapted for use in Russian STI clinics. The elements of the intervention were unchanged, and all the intervention activities and materials were reformatted to meet the needs and specific characteristics of the Russian STI clinic patients.

The IMB model contains three main components: HIV prevention information, HIV prevention motivation, and HIV prevention behavioral skills [8]. The STI/HIV prevention information and education component discussed the local prevalence of HIV, clarified misconceptions, dispelled myths about STI/HIV infection and AIDS using a myth-facts game, and described HIV antibody testing and the role of STIs in the sexual transmission of HIV. The HIV prevention motivating skill enactments reviewed lapses to unsafe behavior frequently involving the use alcohol or other substances and triggers (e.g., settings and moods). Decisional balance exercises, including self-confidence ratings for reducing alcohol-related risks, were used to elicit motivating statements from participants. The final component of the intervention engaged participants in a functional analysis of risk behaviors by having participants discuss risk situations and cues related to their own sexual risks. The counselors discussed the concept of triggers, such as environmental and cognitive affective cues for high-risk situations including mood states, substance use, settings, and sexual partner characteristics. Alcohol was elaborated as a major trigger for risk behaviors. Participants were asked to think of ways to manage triggers to reduce their risks and discussed methods of rearranging their environment and strategies to reduce their risks by performing specific acts, redirecting sexual activities toward safer sex alternatives, carrying condoms, and avoiding sex after drinking or substance use. Practice was conducted in role-playing situations between the counselor and the participant. This was done to increase risk reduction skills and to build self efficacy for enacting behavioral skills in sexual encounters. Male condom use was also instructed and modeled, allowing participants to practice condom application with corrective feedback from the counselor. The counseling session ended with a goal setting exercise.

Training of Counselors and Intervention Quality Assurance

The study counselors consisted of two Russian women who had previous experience with motivational interviewing counseling outside the study protocol. The counseling sessions were conducted in Russian. The counselors were trained using an interactive skills building approach. U.S. and Russian project managers with experience conducting IMB HIV prevention interventions conducted the training over a three week period that included practice and debriefing sessions. To help protect against counselors’ drift and to maintain fidelity, the intervention was manual, and an A4-size flip chart was used to guide the counselors through the session content. The counselors attended bimonthly supervision meetings with the project manager and a training psychologist to debrief their sessions and discuss their adherence to the protocol. The study manager, who reviewed session guides with counselors and debriefed counselors each week also monitored fidelity to the intervention.

Measures

Demographic and risk characteristics

Participants reported their age, sex, marital status, education level, employment status, and monthly income. Participants indicated whether they had ever given or received money or other material gains in exchange for sex and whether they had ever injected illicit drugs.

Sexual behaviors

Participants were asked the number of male and female sexual partners they had in the last three months. Any participants who reported having two or more sexual partners during this period were classified as having multiple partners.

Condom use during the last sexual encounter was determined by answers to the question, “When I had sex last time, I used condoms.” During the assessment, participants were also asked for the following information: 1) the number of vaginal and anal sexual intercourses with a condom in the past three months, and 2) the number of vaginal and anal sexual intercourses without a condom in the past three months. We then calculated the percentage of times a condom was used by dividing the total number of vaginal and anal sexual intercourses with a condom by the total number of vaginal and anal sexual intercourses that they had during the past three months. We defined a proportion of zero as having never used condom in the past three months and a proportion of 100% as consistent condom use. Questions about overall condom use were asked independent of partner type.

Substance use in sexual contexts

Alcohol use before sex was based on the question regarding the number of times participants consumed alcohol before sex in the past three months. A number of ≥ 1 was defined as alcohol use before sex. Drug use before sex was based on the question regarding the number of times that participants consumed drugs before sex in the past three months, and a number of ≥ 1 was defined as drug use before sex. Based on a need to limit the time required to complete the assessment to approximately one hour, questions designed to identify the type of drugs used before sex, and whether these drugs were injected, were not asked.

Statistical analysis

A Chi-square test was used to compare differences in demographic characteristics between the intervention and control groups. Continuous variables that were significantly skewed (i.e., number of protected and unprotected sex acts) were further transformed using the formula ln (x + 1), with nontransformed observed values presented in the tables.

The effectiveness of the HIV intervention was analyzed over the entire six-month period (from baseline to the six-month assessment) using logistic and linear generalized estimating equation (GEE) models. The GEE designed to deal with correlated data such as repeated measurements within subjects allows for a differential number of observations on subjects over a longitudinal course of observation. These models were adjusted for the corresponding baseline measure for each outcome and other covariates (i.e., age, gender, education, marital status, monthly income, and employment status). Moreover, an indicator for the time period was included in the model to control for any unaccounted temporal effects. For outcomes with a significant intervention effect, post-hoc tests (logistic regression for dichotomized outcomes and linear regression for continuous outcomes, adjusting for the corresponding baseline measure for each outcome and other covariates) were further conducted to examine whether a specific period contributed to the significant overall intervention effect. The significance level was defined as p < 0.05, and data were analyzed using SAS software (version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Recruitment and participants’ socio-demographic characteristics

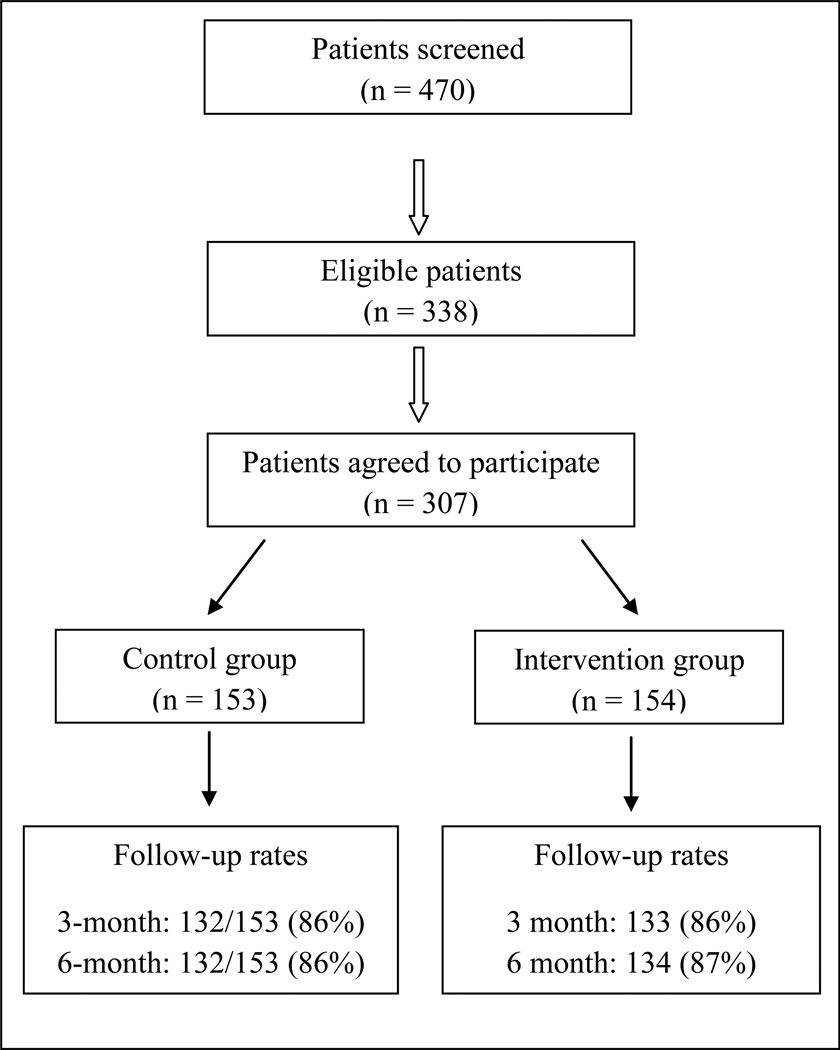

Among 470 patients approached, 338 met the study entry criteria and were invited to participate (Figure 1). In total, 31 patients refused to participate. A total of 307 individuals (87 women and 220 men) agreed to participate. Among 153 participants in the control group, 132 (86%) participated in the three- and six-month follow-ups; among 154 participants in the intervention group, 133 (86%) and 134 (87%) participated in the three- and six-month follow-ups, respectively. The mean (standard deviation [SD], range) age of the patients who refused to participate and those who participated were 29.1 (9.1, 19–49) and 26.9 (7.7, 18–56) years old, respectively (p = 0.16 for the difference of mean age between patients who refused to participate and those who participated).

Figure 1.

Flow of study participants in St. Petersburg, Russia, 2019–2011

The mean (SD, range) age among participants in the control and intervention groups were 27.0 (7.9, 18–56) and 26.8 (7.4, 18–53) years respectively (Table 1). In the control group, 75% of the participants were male, and this proportion was 68% in the intervention group (Chi-square = 1.84, p = 0.17). About one-fifth of the participants were married (20% in the control group vs. 21% in the intervention group, Chi-square = 0.06, p = 0.80), and at least half of the participants had some higher education experience (49% in the control group vs. 52% in the intervention group, Chi-square = 0.26, p = 0.61). About 54% of participants in the control group and 49% of participants in the intervention group were employed on a full-time basis (Chi-square = 0.74, p = 0.39).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants in St. Petersburg, Russia (n = 307)

| Characteristics | Control group (n = 153) |

Intervention group (n = 154) |

Chi-square (d.f.=1), p- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (25 years or less)a | 74 (48.4%) | 78 (50.7%) | 0.16, 0.69 |

| Being male | 115 (75.2%) | 105 (68.2%) | 1.84, 0.17 |

| Being married | 31 (20.3%) | 33 (21.4%) | 0.06, 0.80 |

| At least having some higher education | 75 (49.0%) | 80 (52.0%) | 0.26, 0.61 |

| Monthly income < 15,000 rubles | 65 (42.5%) | 66 (42.9%) | 0.00, 0.95 |

| Full time employment | 83 (54.3%) | 76 (49.4%) | 0.74, 0.39 |

Mean (SD, range) age for control and intervention group were 27.0 (7.9, 18–56) and 26.8 (7.4, 18–53) years respectively.

Attrition monitoring

No differences in attrition were observed between study conditions at either the three-month or six-month assessment (Figure 1). Additionally, no differences were observed in the baseline variables, including study condition, socio-demographic characteristics, and HIV related behaviors in the participants retained in the trial compared with those unavailable for follow-up (Table 2). Effects of the HIV intervention

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between participants who were fully followed-up and those who were lost to follow-up at least once

| Characteristics | Completely followed-up (n = 252) |

Loss to follow-up once (n = 27) |

Completely loss to follow-up (n = 28) |

Chi-square (d.f.=2), p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | 51.2% | 33.3% | 57.1% | 3.71, 0.16 |

| Age (25 years or less) | 47.6% | 63.0% | 53.6% | 2.50, 0.29 |

| Being male | 70.6% | 74.1% | 78.6% | 0.87, 0.65 |

| Being married | 21.8% | 14.8% | 17.9% | 0.89, 0.64 |

| At least having some higher education | 53.2% | 33.3% | 42.9% | 4.56, 0.10 |

| Monthly income < 15,000 rubles | 42.1% | 48.2% | 42.9% | 0.37, 0.83 |

| Full time employment | 54.4% | 44.4% | 35.7% | 4.15, 0.13 |

| Multiple partners, past 3 months | 71.0% | 77.8% | 78.6% | 1.16, 0.56 |

| Used condom at last sexual intercourse | 42.5% | 33.3% | 28.6% | 2.63, 0.27 |

| Consistent condom use, past 3 months | 12.3% | 0.0% | 14.3% | 3.91, 0.14 |

| Never used condoms, past 3 months | 22.2% | 29.6% | 39.3% | 4.41, 0.11 |

| Alcohol use before sex | 81.8% | 85.2% | 82.1% | 0.20, 0.91 |

| Drug use before sex | 12.7% | 29.6% | 17.9% | 5.84, 0.05 |

Table 3 summarizes the HIV-related behaviors in the control and intervention groups at the baseline and three- and six-month follow-ups among participants. This table also provides the significance test results for the intervention based on the GEE models. Compared to participants in the control group, those in the intervention group showed a higher percentage of condom use (45%, 67%, and 62%, at baseline and three- and six-month follow-ups, respectively, for the intervention group vs. 43%, 55%, and 56% for the control group; Wald Chi-square = 4.74, p = 0.03), were more likely to consistently use condoms (12.3%, 42.9% and 40.3%, respectively, for the intervention group vs. 10.5%, 28.0%, and 34.1% for the control group; Wald Chi-square = 4.74, p = 0.03), and were less likely to use drugs before sex (9.7%, 6.0%, and 3.7%, respectively, for the intervention group vs. 19.1%,15.9%, and 12.1% for the control group; Wald Chi-square = 4.29, p = 0.04), adjusting for the corresponding baseline measure for each outcome and socio-demographic characteristic. In addition, the intervention effect for the number of unprotected sexual acts was at the borderline significance (means (SD) = 18.9 (30.1), 13.3 (21.8), and 15.7 (26.2), respectively, for the intervention group vs. 19.9 (29.0), 16.6 (26.1) and 18.3 (29.9) for the control group, Wald Chi-square = 3.53, p = 0.06).

Table 3.

STI/HIV risk behaviors in the control and intervention group at the baseline, 3-and 6-month follow-up in St. Petersburg, Russiaa

| Behaviors | Baseline | 3-month | 6-month | Wald Chi- square, p- valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of protected sex acts (mean [SD]) | 0.16, 0.68 | |||

| Control | 14.3 (37.7) | 16.3 (32.2) | 16.3 (29.9) | |

| Intervention | 12.6 (20.0) | 15.8 (18.4) | 16.9 (24.2) | |

| Number of unprotected sexual acts (mean [SD]) | 3.53, 0.06 | |||

| Control | 19.9 (29.0) | 16.6 (26.1) | 18.3 (29.9) | |

| Intervention | 18.9 (30.1) | 13.3 (21.8) | 15.7 (26.2) | |

| Percentage of condom use (mean [SD]) | 4.74, 0.03 | |||

| Control | 0.43 (0.38) | 0.55 (0.40) | 0.56 (0.41) | |

| Intervention | 0.45 (0.37) | 0.67 (0.38) | 0.62 (0.42) | |

| Multiple partners, past 3 months | 2.67, 0.10 | |||

| Control | 73.9% | 55.3% | 47.0% | |

| Intervention | 70.8% | 47.4% | 36.6% | |

| Used condom at last sexual intercourse | 0.12, 0.73 | |||

| Control | 40.5% | 57.6% | 55.3% | |

| Intervention | 40.3% | 58.7% | 53.0% | |

| Consistent condom use, past 3 months | 4.74, 0.03 | |||

| Control | 10.5% | 28.0% | 34.1% | |

| Intervention | 12.3% | 42.9%* | 40.3% | |

| Never used condoms, past 3 months | 0.40, 0.53 | |||

| Control | 26.1% | 18.9% | 20.5% | |

| Intervention | 22.7% | 13.5% | 18.7% | |

| Alcohol use before sex | 1.72, 0.19 | |||

| Control | 85.0% | 78.0% | 80.3% | |

| Intervention | 79.2% | 67.7% | 73.1% | |

| Drug use before sex | 4.29, 0.04 | |||

| Control | 19.1% | 15.9% | 12.1% | |

| Intervention | 9.7% | 6.0% | 3.7% |

Mean and standard deviation (SD) were provided for continuous variables and proportion was provided for categorical variables.

Generalized estimation equations models were used to test group difference at the follow-ups adjusting for age, gender, education, marital status, monthly income, employment status and baseline outcome

Post hoc analysis

Results from the post hoc tests for outcomes with a significant intervention effect at three- and six-month follow-ups demonstrated that: (1) Participants in the intervention group had a significantly higher percentage of condom use at the three-month follow-up than those in the control group (t-value = 2.89, p = 0.004), and no significant difference was observed at the six-month follow-up (t-value = 1.07, p = 0.29); (2) Participants in the intervention group were more likely to use condoms consistently at the three-month follow-up than those in the control group (Wald Chi-square = 7.25, p = 0.007), and no significant difference was observed at the six-month follow-up (Wald Chi-square = 1.17, p = 0.28); and (3) No significant difference for drug use before sex was observed at either the three- or six-month follow-ups (Wald Chi-square = 2.98, p = 0.08; and Wald Chi-square = 2.36, p = 0.12, respectively). Given the marginal significance, we also examined the three- and six-month effects for the number of unprotected sex acts. (4) Participants in the intervention group were less likely (t-value = 2.10, p = 0.04) to report unprotected sex acts at the three-month follow-up than those in the control group, and no significant difference (t-value = 0.95, p = 0.35) was observed at the six-month follow-up.

DISCUSSION

This study used a randomized design to test the potential efficacy of a brief HIV prevention counseling intervention culturally adapted for use in Russia. To our knowledge, this is the first trial in Russia demonstrating that a single session 60-minute HIV intervention can result in short term reductions in sexual risk behaviors and increase protective behaviors among STI clinic participants. The findings are particularly promising given that a single one hour counseling session intervention on HIV prevention can easily be incorporated into existing medical settings in Russia.

The findings should be interpreted with caution. The trial compared the effects of an experimental intervention against participants receiving written HIV prevention information rather than an attention control condition (i.e., a control condition in which participants receive HIV prevention information from the intervention counselors). This suggests that it is possible that the 60 minute contact time of the counseling session alone may have accounted for the differences between the conditions. Moreover, parallel improvements within the control and intervention groups were observed in certain intervention variables, suggesting that participants of the control group may have been able to reflect on and reduce some of their HIV/STI risk behaviors after receiving the usual standard of care and reading the study’s HIV prevention information material.

The brief HIV risk counseling intervention demonstrated significant reductions in the number of unprotected sexual acts and the frequency of drug use before sex and a significant increase in the consistent use of condoms and the percentage of occasions where condoms were used. Post hoc analyses revealed that most of the significant effects were of short duration since they were significant three months following the intervention. Results showing improved behaviors six months after the intervention though not measurable at a significant level, suggest that replication of the study with a larger sample size might have detected some effects of longer duration among this study population. However, the lack of difference between the two groups after six months indicates that the effects of the intervention wear off after three months. Effects of short duration have been observed in other similar brief interventions [23] and suggest that for a sustained effect, a longer intervention or booster sessions may be required. Future research will need to improve the long term outcomes of this intervention.

The improvement in consistent condom use among intervention participants may have major public health implications for women because studies in Russia show that females are at greater risk for having STIs compared to men [24], and abortion prevalence, mostly due to unintended pregnancies, can be as high as 50% among women from the general population [18] or those seeking services in STI clinics [16]. Thus, the promotion of consistent condom use should be an integral and essential part of comprehensive HIV prevention, treatment and care programs in Russia. This study did not address the risk for unintended pregnancy among women. Thus, although our sample was limited by the small number of women enrolled in the trial, this study found no indications for differential intervention effects between men and women. Future studies with greater numbers of women will need to confirm the gender related findings and include pregnancy risk prevention as an additional means to promote condom use among women.

The study found substantial reductions in the use of drugs before sex but the use of alcohol prior to sex did not decrease after the intervention. The reduction in drug use prior to sex must be interpreted with caution. There was a significant overall intervention effect for this variable, but the post hoc analyses at three- and six-month follow-ups showed no significant effects. This is probably because the overall analysis uses data from all follow-ups whereas in the post hoc analyses, only half of the data is used; that is, either the three-month or the six-month follow-up data are included. It is therefore likely that the first type of analysis has more statistical power to detect significant effects than the second. Despite these findings, this is still a worthwhile outcome given the significant role that substance use may play in the sexual transmission of HIV in Russia. Substance use, including alcohol, as well as the use of substances prior to sex has been directly associated with sexual risk behaviors among STI clinic patients and other people at risk for HIV in Russia [13, 14]. Interventions to reduce substance use are complex, often requiring multiple sessions [25] and multiple components to address the various needs of the substance users [26]. Possibly for these reasons, a brief intervention to reduce harmful drinking in Russia showed unsuccessful results [27]. Our results suggest that it may be feasible for a brief intervention to reduce substance use prior to sex and that brief interventions to reduce sexual risk behaviors in Russia may benefit from addressing the use of substances prior to sexual intercourse. Future studies will need to investigate the forms of intake and types of drugs that are commonly used prior to sex and whether a reduction in the use of these drugs prior to sex is associated with greater condom use among study participants

The present study has several limitations. Our recruitment method may have limited the generalizability of the study findings to places outside of the St. Petersburg STI clinic or even to a different patient sample from the same clinic. It may not be applicable to patients with different sociodemographic characteristics or risk profiles. The study did not investigate possible interactions between participants; therefore, contamination bias may have occurred. However, this type of bias would have affected the results toward the null. Although our findings are bolstered by the consistent and logical results observed, the study relied on self reported behavior for its primary outcomes. Different outcomes might have been found if the intervention had been compared to a time matched information session. The statistical power and precision of effect estimates may have been limited by the small sample size and missing data. Future studies will require larger samples and longer follow-up periods to yield more precise and stable effect estimates. With these limitations recognized, we believe that HIV risk reduction counseling has the potential to prevent HIV transmission in Russia.

CONCLUSIONS

The brief HIV risk counseling intervention demonstrated significant short term reductions in some HIV sexual risk behaviors and enhancement of protective behaviors. The findings are promising given that brief face-to-face HIV prevention counseling interventions can easily be implemented in resource limited clinical settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND FUNDING

This work was funded by Grant Number R01AA017389 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (PI: N. Abdala).

REFERENCES

- 1.United Nations: Department of economic and social affairs, population division, World Population Prospects. The 2008 Revision, Highlights, 2009, Working Paper No. ESA/P/WP-210

- 2.AIDS Foundation East-West: Knowledge centre. [last accessed 09/18/2010];HIV Statistics for Belarus, Moldova, Russia and Ukraine 2008. 2010 http://www.afew.org/knowledge-centre/hivstatistics/

- 3.UNAIDS/WHO. Aids epidemic update | global report. Geneva: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNAIDS/WHO. Aids epidemic update: December 2005. Special section on hiv prevention. Geneva: UNAIDS/WHO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health and Social Development of the Russian Federation. Country progress report of the russian federation on the implementation of the declaration of commitment on hiv/aids. Moscow: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO/Europe. Risk factors impacting on the spread of hiv among pregnant women in the russian federation. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNAIDS/WHO. Aids epidemic update: Eastern europe and central asia: Geneva. Geneva: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing aids-risk behavior. Psychol Bull. 1992;111:455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Skinner D, et al. Theory-based hiv risk reduction counseling for sexually transmitted infection clinic patients in cape town, south africa. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:727–733. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000145849.35655.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crosby RA, Salazar LF, Yarber WL, et al. A theory-based approach to understanding condom errors and problems reported by men attending an sti clinic. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:412–418. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhan W, Hansen NB, Shaboltas AV, et al. Partner violence perpetration and victimization and hiv risk behaviors in st. Petersburg, russia. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25:1–8. doi: 10.1002/jts.21658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhan W, Krasnoselskikh TV, Niccolai LM, et al. Concurrent sexual partnerships and sexually transmitted diseases in russia. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:543–547. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318205e449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdala N, White E, Toussova OV, et al. Comparing sexual risks and patterns of alcohol and drug use between injection drug users (idus) and non-idus who report sexual partnerships with idus in st. Petersburg, russia. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:676. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdala N, Grau LE, Zhan W, et al. Inebriation, drinking motivations and sexual risk taking among sexually transmitted disease clinic patients in st. Petersburg, russia. AIDS Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0091-z. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO. Alcohol use and sexual risk behaviour. A cross-cultural study in eight countries, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse - Geneva. 2005

- 16.Abdala N, Zhan W, Shaboltas AV, Skochilov RV, Kozlov AP, Krasnoselskikh TV. Correlates of abortions and condom use among high risk women attending an std clinic in st petersburg, russia. Reprod Health. 2011;8:28. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regushevskaya E, Dubikaytis T, Laanpere M, et al. The determinants of sexually transmitted infections among reproductive age women in st. Petersburg, estonia and finland. Int J Public Health. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00038-010-0161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regushevskaya E, Dubikaytis T, Nikula M, Kuznetsova O, Hemminki E. Contraceptive use and abortion among women of reproductive age in st. Petersburg, russia. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;41:51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1931-2393.2009.04115109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talykova LV, Vaktskjold A, Serebrjoakova NG, et al. Pregnancy health and outcome in two cities in the kola peninsula, northwestern russia. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007;66:168–181. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v66i2.18249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Twigg J. Commitment, resources, momentum, challenges. Washington D.C: Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS); 2007. HIV/AIDS in Russia. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zagdyn ZM, Kovelenov AU, Semikova SU, et al. Spread of hiv infection in leningrad oblast during 1999–2009. EpiNorth. 2010;11:121–130. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalichman SC, Cain D, Weinhardt L, et al. Experimental components analysis of brief theory-based hiv/aids risk-reduction counseling for sexually transmitted infection patients. Health Psychol. 2005;24:198–208. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, et al. Randomized trial of a community-based alcohol-related hiv risk-reduction intervention for men and women in cape town south africa. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:270–279. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Celentano DD, Mayer KH, Pequegnat W, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative HIVSTDPTG: Prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases and risk behaviors from the nimh collaborative hiv/std prevention trial. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2010;22:272–284. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2010.494092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Rhodes F, Desmond K, Weiss RE. Reducing hiv risks among active injection drug and crack users: The safety counts program. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:658–668. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9606-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Desmond K, Comulada WS, Arnold EM, Johnson M. Reducing risky sexual behavior and substance use among currently and formerly homeless adults living with hiv. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1100–1107. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.121186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen E, Polikina O, Saburova L, McCambridge J, Elbourne D, Pakriev S, Nekrasova N, Vasilyev M, Tomlin K, Oralov A, Gil A, McKee M, Kiryanov N, Leon DA. The efficacy of a brief intervention in reducing hazardous drinking in working age men in russia: The him (health for izhevsk men) individually randomised parallel group exploratory trial. Trials. 2011;12:238. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]