Abstract

The process of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) which is required for cancer cell invasion is regulated by a family of E-box binding transcription repressors which include Snail (SNAI) and Slug (SNAI2). Snail appears to repress the expression of the EMT marker E-cadherin by epigenetic mechanisms dependent on the interaction of its N-terminal SNAG domain with chromatin modifying proteins including lysine specific demethylase 1 (LSD1/KDM1A). We assessed whether blocking Snail/Slug-LSD1 interaction by treatment with Parnate, an enzymatic inhibitor of LSD1, or TAT-SNAG, a cell-permeable peptide corresponding to the SNAG domain of Slug, suppresses the motility and invasiveness of cancer cells of different origin and genetic background. We show here that either treatment blocked Slug-dependent repression of the E-cadherin promoter and inhibited the motility and invasion of tumor cell lines without any effect on their proliferation. These effects correlated with induction of epithelial and repression of mesenchymal markers and were phenocopied by LSD1 or Slug down-regulation. Parnate treatment also inhibited bone marrow homing/engraftment of Slug-expressing K562 cells. Together, these studies support the concept that targeting Snail/Slug-dependent transcription repression complexes may lead to the development of novel drugs selectively inhibiting the invasive potential of cancer cells.

Introduction

Metastases represent the end point of a multistep process, the invasion-metastasis cascade, which leads to the dissemination of cancer cells to anatomically distant organs (1,2). Whereas surgical resection and adjuvant therapy can cure well-confined primary tumors, metastatic disease is largely incurable because of its systemic nature and resistance to cytotoxic drugs, accounting for >90% of cancer mortality (1–3). The ability of tumor cells to become “invasive” depends on the activation of an evolutionarily conserved developmental process known as EMT through which tumor cells lose homotypic adhesion, change morphology and acquire migratory capacity (4,5). The EMT program involves the dissolution of adherent and tight junctions, loss of cell polarity and dissociation of epithelial cell sheets into individual cells that exhibit multiple mesenchymal attributes, including heightened invasiveness (6), setting the stage for tumor cells to invade locally and spread to distant organs. EMT is thought to contribute to tumor progression and aberrant expression of EMT regulator/inducers in cancer cells correlates with poor clinical outcomes and tumor aggressiveness (7–10). In addition to its clinical significance, altered expression of EMT regulators in cancer may identify new drug targets for development of novel anti-cancer therapies.

Features of EMT have been observed in breast (11), ovarian (12), colon (13), esophageal cancer (14) and in melanoma (15), and inducers of EMT in cancer cell lines include Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β), Wnt, Snail/Slug, Twist, Six1, Zeb1/Zeb2 (16).

Down-regulation of E-Cadherin expression is a key event during EMT. The human E-Cadherin promoter contains E-box elements that are required for regulation of its transcription (17,18). Several zinc-finger transcription factors such as Snail (19,20) and Slug (21) can bind directly to these E-boxes to repress E-Cadherin transcription.

The Snail family of transcription factors that includes Snail, Slug, and Smug is involved in physiological and cancer-associated EMT. Slug contributes to invasion in melanomas (22) and in malignant mesotheliomas (23), its silencing inhibits neuroblastoma invasion in vitro and in vivo (24), its induction is required for the ability of Twist1 to promote invasion and metastasis and the entire EMT process is blocked in the absence of Slug (25). Slug is overexpressed in numerous cancers, including leukemia, lung, esophageal, gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, breast, ovarian, prostate cancer, malignant mesothelioma, cholangiocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma and glioma (26). Elevated expression of Slug is associated with reduced E-Cadherin expression, high histologic grade, lymph node metastasis, post-operative relapse, and shorter patients’ survival in a variety of cancers (26–28).

Together, these studies imply that pharmacological inhibition of Snail/Slug-regulated transcription repression would block migration and invasion of tumor cells. Since the effects of Slug on transcription may depend on the interaction of its N-terminal SNAG repressor domain with chromatin-modifying proteins such as lysine specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) (29), we assessed whether treatment with Parnate, an enzymatic inhibitor of LSD1, or TAT-SNAG, a cell-permeable peptide corresponding to the SNAG domain of Slug, blocks Slug-dependent repression of the E-Cadherin promoter and inhibits the motility and invasion of tumor cell lines. We provide here proof of principle for the concept that pharmacological inhibition of Slug-dependent transcription repression suppresses the expression of morphological and molecular markers of EMT and blocks the migration and invasion of tumor cells of different histological and genetic backgrounds.

Material and Methods

Plasmids and Antibodies

E-Cadherin promoter-LUC: the human E-Cadherin promoter (−233 to −1 from the ATG start site; E-box at nt −204 to −198) was cloned by blunt-end ligation in the SmaI site of pGL3-basic plasmid by PCR with forward (FW) (5′-ggtccgcgctgctgattggc-3′) and reverse (RV) (5′-ggctggccggggacgc-3′) primers. pcDNA3-Slug: this plasmid was generated by PCR amplification of human Slug coding sequence with Slug-CDS-FW (5′-ctggttgggatccatgccgcgctccttcc-3′) and Slug-CDS-RV (5′-tcagtgtgctacacagcagcc-3′) primers and subcloning the PCR product into the BamHI/EcoRV-linearized pcDNA3.1(+) plasmid. HA-LSD1-Flag was a kind gift of Dr. Yang Shi (Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA). Antibodies were purchased from: anti-HA, Covance (#MMS-101P); anti-Slug, Abgent (#AP2053a); anti-p53, Calbiochem (#OP09); anti-E-cadherin and anti-β-catenin, BD Transduction Laboratories (#610181 and #610153, respectively); anti-LSD1, Abcam (#ab17721); anti-CD44, e-Biosciece (#11-0441-82); anti-β-Actin, Santa Cruz Biotechnology (#sc-47778).

pTAT plasmids and protein purification

The pTAT-SNAG plasmid was generated by inserting oligodeoxynucleotides encoding the highly conserved nine amino acid sequence MPRSFLVKK of the SNAG domain, flanked by engineered XhoI and EcoRI sites, into the XhoI-EcoRI sites of pTAT-HA vector (kind gift of Dr SF Dowdy). The pTAT-HA vector alone was used as negative control.

Fusion peptides were produced by Escherichia coli strain (DE3)pLysS (Novagen) after a 3-h 1mM IPTG induction at 37°C. The cell pellet was lysed in 50mM NaH2PO4, 300mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0 and sonicated. Fusion peptides were purified from clear lysates using the batch/gravity-flow method with NiNTA Agarose (Qiagen) and eluted from the resin with lysis buffer containing 200mM imidazole. Buffer exchange in PBS was performed on purified peptides using PD-10 Desalting Columns (GE Healthcare); peptides were stored at −80°C.

Cell lines and treatments

Cell lines used in this study were tested for mycoplasma contamination (PCR Mycoplasma detection set, Takara Bio Inc) every three months. 293T and HTLA230 (human neuroblastoma) cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Invitrogen); parental and p53-null HCT116 (human colon carcinoma) and parental or derivative (pBabe-puro or pBABE-Slug) Colo205 (human colon carcinoma) cell lines (8) were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Cell lines 293T, HCT-116 and Colo205 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and characterized by DNA fingerprinting and isozyme detection; cell line HTLA230 was obtained from Dr Raschella’s laboratory and was previously described (24). The HCT116 p53-null cell line was kindly provided by Dr. B. Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). HTLA230 cells lentivirally transduced with pLKO-shGFP or pLKO-shSlug were previously described (24). LSD1-silenced HCT116 cells were generated by lentiviral transduction with plasmid pGIPZ-shLSD1-H6 (Open Byosystems).

Cells were treated with 100 μM trans-2-Phenylcyclopropylamine hydrochloride (Parnate; PCPA), a non-selective monoaminoxidase (MAO-A/B) inhibitor and a LSD1 enzymatic inhibitor (#P8511, Sigma Aldrich), or with 50nM pTAT-SNAG or pTAT peptides.

Immunofluorescence

Five x 104 cells for each time point were seeded on a glass cover in a 12-well microtiter plate. At the end of the treatment with Parnate, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized by incubation with PBS + 0.01% Triton X-100 (Sigma) for 5 min, and stained with anti-E-cadherin or anti-β-catenin antibody (#610181 and #610153, respectively; BD Transduction Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ USA) in PBS + 5% horse serum for 1 hour. Secondary antibody was Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti mouse antibody (# A11001; Invitrogen) in PBS + 5% horse serum. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Photographs were taken using a Zeiss Axiophot fluorescence microscope equipped with Axiovision software version 4.6 (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Immunoprecipitation

For immunoprecipitation, a 70–90% confluent 100 mm dish (106–107 cells) of 293T cells transfected with HA-LSD1-Flag and 3 pcDNA3-Slug expression plasmids (3 μg each) were lysed in 1 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4, with 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% TRITON X-100, and protease inhibitors). Cell lysate (3mg) was incubated at 4°C with 60 μl of anti-Flag M2 Affinity Gel resin (#A2220, Sigma Aldrich) prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PCPA (100 μM) or pTAT-SNAG/pTAT peptide (10μg/ml) was added to the immunoprecipitation buffer and the IP performed after overnight (PCPA experiment) or 2-h (pTAT peptides experiment) incubation.

Beads were then washed with lysis buffer and the immunoprecipitated protein complexes were resolved by 8% SDS–PAGE in absence of 2-mercaptoethanol.

Luciferase Assay

293T and HCT116 cells were transiently transfected using, respectively, ProFection Mammalian Transfection System-Calcium Phosphate (Promega) or SuperFect Transfection Reagent (Qiagen), with 3 μg of reporter plasmid E-Cadherin promoter-LUC, 1 μg of pcDNA3 empty vector or pcDNA3-Slug expression plasmid, and 1/50 Renilla luciferase plasmid to account for variation in transfection efficiencies. 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with 100 μM PCPA for 24 h, or with 50nM of pTAT peptides for 6h. Firefly and renilla luciferase activity was recorded on a luminometer using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Results are expressed as luciferase activity normalized for Renilla activity and represent the means ± S.D. of three (PCPA) or two (pTAT-SNAG or pTAT peptide) experiments.

Migration and Invasion Assay

For the wound healing assay, cells were plated to confluence in a 6-well plate and the cell surface was scratched using a pipette tip. Then, cells were treated with 100 μM PCPA or with 50nM pTAT-SNAG or pTAT added at 2h intervals for 12 hours followed by a final dose 24 hours after scratching the cell surface, allowed to repopulate the scratched area for 3 days, and photographed using a digital camera mounted on an inverted microscope (magnification 5X). Accurate wounds measurements were taken at 0 and 72h to calculate the migration rate according to the equation: percentage wound healing = [(wound length at 0 h)−(wound length at 72 h)]/(wound length at 0 h) X 100. Two independent experiments were performed.

For invasion assays, cells were plated (105 cell/chamber) in BD BioCoat Matrigel invasion chambers (BD Biosciences). In the upper chamber, medium was supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated FBS. In the lower chamber, 20% FBS was used as chemoattractant. 100μM PCPA or 50nM pTAT-SNAG or pTAT (at 2-h intervals for 12 hours) was added in the upper chamber. After 24 h, medium was removed and chambers washed twice with PBS; non-invading cells were removed from the upper surface of the membrane by scrubbing with a cotton tipped swab; invading cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 2 min, washed with PBS twice, permeabilized with methanol for 20 min, washed twice with PBS, stained with 0.05% crystal violet for 15 min, and washed twice with PBS. 10 fields for each chamber were photographed using a digital camera mounted on an inverted microscope (magnification 10X) and invading cells were counted in each field. Experiments were carried out in duplicate and repeated twice.

Real-Time Q-PCR analyses

For real time quantitative-PCR, total RNA was isolated from Parnate or TAT-SNAG-treated cells using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). After digestion with RNase-free DNase (Roche Applied Science), RNA (4 μg) was reverse-transcribed using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen), and first-strand cDNA used as PCR template. Reactions were done in triplicate and RNA was extracted from two separate experiments.

Primer pairs of analyzed genes (Desmoplakin: FW 5′-gctaaacgccgccaggat-3′, RV 5′-ccgcatgactgtgttggaat-3′; Occluding: FW 5′-gccggttcctgaagtggtt-3′, RV 5′-cgaggctgcctgaagtcatc-3′; E-Cadherin: FW 5′-ccgctggcgtctgtaggaagg-3′, RV 5′-ggctctttgaccaccgctctcc-3′; N-Cadherin: FW 5′-ctgtgggaatccgacgaatgg-3′, RV 5′-gtcattgtcagccgctttaagg-3′; Vimentin: FW 5′-ccagccgcagcctctacg-3′, RV 5′-gcgagaagtccaccgagtcc-3′; HPRT: FW 5′-agactttgctttccttggtcagg-3′, RV 5′-gtctggcttatatccaacacttcg-3′; Slug: FW 5′-tgtgtggactaccgctgctc-3′, RV 5′-gagaggccattcggtagctg-3′) were designed using Beacon Design software. Real time Q-PCR was performed using GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega) on a MyIQ thermocycler (Bio-Rad) and quantified using MyIQ software (Bio-Rad) that analyzes the Ct value of real-time PCR data with the ΔΔCt method. HPRT, a housekeeping gene with constant expression, was used as an internal control to normalize input cDNA.

Homing/engraftment assay of K562 cells in NOD/SCID mice

For the homing/engraftment assay, NOD/SCID mice (NOD.CB17-Prkdc scid/J, Charles River Laboratories International, Inc. Wilmington, MA) (five/group) were injected (2 × 106 cells/mouse) with untreated or PCPA-treated (16h, 100 μM) Slug-K562 cells. 24 h later, mice were sacrificed, bone marrow harvested, and number of K562 cells determined by GFP positivity and by methylcellulose colony formation assays (50,000 cells/plate) in the absence of hemopoietic cytokines to allow growth of K562 cells only.

Statistical Analyses

Data (means ± S.D., two or three experiments) were analyzed for statistical significance by unpaired, 2-tailed Student’s t test. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Effect of Parnate on the Slug-regulated E-Cadherin promoter

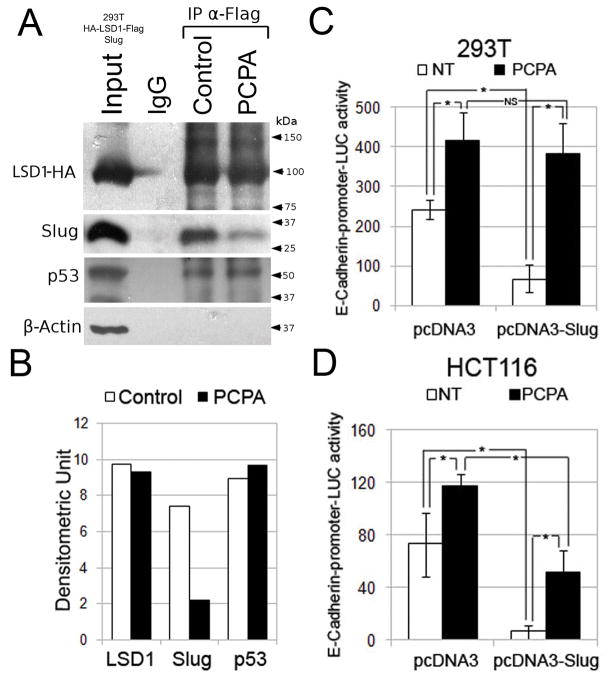

Previous studies have shown that LSD1 interacts with the SNAG domain of Snail (29–31) through its C-terminal amine oxidase domain (29); thus, we first assessed whether the monoamine oxidase/LSD1 inhibitor Parnate blocks the interaction between Slug and LSD1 in 293T cells co-transfected with expression vectors encoding human HA-Flag-LSD1 and Slug. As shown in Figure 1A and B, LSD1 and Slug readily interacted in the absence of Parnate but their association was suppressed when the cell lysate was treated with this compound; the effect of Parnate was specific because it did not block the interaction of LSD1 with endogenous p53 (32) (Figure 1A and B). Since the Snail-LSD1 interaction may be necessary for Snail-dependent repression of the E-cadherin promoter (29–31), we performed luciferase assays in 293T and HCT116 colon cancer cells to test whether ectopically expressed Slug represses the activity of the E-cadherin promoter and if treatment with Parnate blocks the effect of Slug. Indeed, E-cadherin promoter-driven luciferase activity was repressed by Slug in both cell lines and treatment with Parnate blocked the effect of Slug (Figure 1C and D); the activity of the E-cadherin promoter was also enhanced in cells treated with Parnate only (Figure 1C and D), probably due to inhibition of endogenous Snail/Slug proteins.

Figure 1. Effect of Parnate on Slug-LSD1 interaction and Slug-dependent repression of the E-cadherin promoter.

(A and B) Western blot and densitometry of HA-tagged LSD1, Slug, p53 and β-Actin expression in total lysate or anti-FLAG-LSD1 IPs from 293T cells co-expressing LSD1 and Slug; histograms show E-cadherin-driven luciferase activity in untreated and Parnate-treated 293T (C) and empty vector-transfected or Slug-expressing HCT116 (D) cells. Representative of three experiments performed in triplicate; * denotes p values < 0.05.

Effect of Parnate on migration and invasion of tumor cell lines

We then asked whether treatment with Parnate impairs the migration and invasion of tumor cell lines. In a wound healing assay, untreated colon cancer HCT116 and neuroblastoma HTLA230 cells filled almost completely the wounded area three days after scratching the cell monolayer, whereas treatment with different doses of Parnate markedly suppressed repair of the wound (Figure 2A and B). The inhibitory effect of Parnate on repopulation of the wounded area was not due to decreased proliferation because growth of untreated and Parnate-treated tumor cells was undistinguishable (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Effect of Parnate on migration, invasion and proliferation of tumor cell lines.

(A and B) microphotographs show repopulation of wounded area of untreated and Parnate-treated HCT116 and HTLA230 cells; on the right, histograms represent accurate wound measurements taken at 0 and 72h for each treatment to calculate the migration rate; data are presented as means ± S.D. from two independent experiments; (C) histograms show invasion inhibition (expressed as % of untreated cells taken as 100) by Parnate treatment; microphotographs show representative fields of Giemsa-stained lower membranes of the Boyden chambers; (D) histograms show number of untreated and Parnate-treated cells counted by trypan blue exclusion; representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (p<0.05, Student’s t test).

The effect of Parnate on cell invasion was tested using Matrigel-coated Boyden chambers; Parnate-treated HCT116, HTLA230 and Colo205 colon cancer cells (parental and Slug-expressing) were markedly less invasive of the untreated counterpart (20 to 38% residual invasion) (Figure 2C), but their proliferation rates were identical (Figure 2D, right panel). Because the cell lines used in the invasion assays have a wild type p53 gene and the p53-null genotype promotes the invasiveness of cancer cells (33,34), we assessed whether treatment with Parnate also suppressed the migration and invasion of p53−/−HCT116 cells (35). Indeed, migration and invasiveness of these cells was also markedly inhibited by Parnate treatment (Supplementary Figure 1).

The concept that the effects of Parnate depend on disruption of LSD1 and Snail/Slug activity was validated in LSD1- and Slug-silenced tumor cell lines; as shown in Supplementary Figure 2, LSD1-silenced HCT116 cells exhibited lower migration and invasion than control HCT116-shGFP cells; likewise, Slug-silenced HTLA230 cells were markedly less invasive than HTLA230-shGFP cells; moreover, they expressed higher levels of the epithelial markers E-Cadherin, Occludin and Desmoplakin and lower levels of the mesenchymal markers Vimentin and N-Cadherin (Supplementary Figure 3).

Effect of Parnate on homing/engraftment of K562 cells

We showed recently that expression of Slug is required for the homing/engraftment of Philadelphia1 K562 cells to the bone marrow (36); thus, we assessed whether treatment with Parnate suppresses the interaction between Slug and LSD1 in Slug-overexpressing K562 cells and inhibits the homing/engraftment of these cells to the bone marrow of NOD/SCID mice. As shown in Figure 3A, anti-Slug western blotting of LSD1 IPs from untreated and Parnate-treated Slug-K562 cells indicate that the amount of Slug in complex with LSD1 was markedly reduced after treatment with Parnate; we assessed bone marrow homing/engraftment of untreated and Parnate-treated (16h) Slug-expressing K562 cells 24h after injection in NOD/SCID mice (2 × 106 cells/mouse; five mice/group) by measuring GFP positivity and colony formation in methylcellulose plates not supplemented with cytokines. As shown in Figure 3B and C, treatment with Parnate caused a decrease (approximately 50%) in the number of GFP-positive Slug-K562 cells migrating to the bone marrow (panel B) and of cytokine-independent clonogenic K562 cells (panel C). Since the hyaluronan receptor CD44 is required for the bone marrow homing/engraftment of BCR-ABL-expressing cells (37), we assessed CD44 levels in untreated and Parnate-treated K562 cells; as shown in Figure 3D, Slug-K562 cells express higher levels of CD44 than parental cells; however, treatment with Parnate had no effect on CD44 expression, suggesting that the effect of Parnate on K562 homing/engraftment might be CD44-independent.

Figure 3. Effect of Parnate on Slug-LSD1 interaction and bone marrow homing of Slug-expressing K562 cells.

(A) western blots (left) and densitometry (right) of Slug expression in total lysate (at shorter exposure’s time) and anti-LSD1 IPs of untreated and Parnate-treated Slug-K562 cells; (B and C) histograms show: number of GFP-positive (B) and clonogenic (C) cells in the bone marrow of NOD/SCID mice (n=5) 24 h after injection with untreated or Parnate-treated (16 h, 100μM) Slug-K562 cells (2 × 106 cells/mouse). For colony formation assays, 5 × 104 cells/plate (in triplicate) were plated in methylcellulose medium without cytokines to allow growth of K562 cells only. Colonies were counted five days after plating. Data are reported as the mean + S.D. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (p<0.05, Student’s t test); (D) histogram shows CD44 levels (detected by flow cytometry) in untreated and Parnate-treated parental and Slug-K562 cells. Representative of two experiments; inset shows Slug expression in parental and Slug-expressing K562 cells.

Effect of Parnate on expression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers

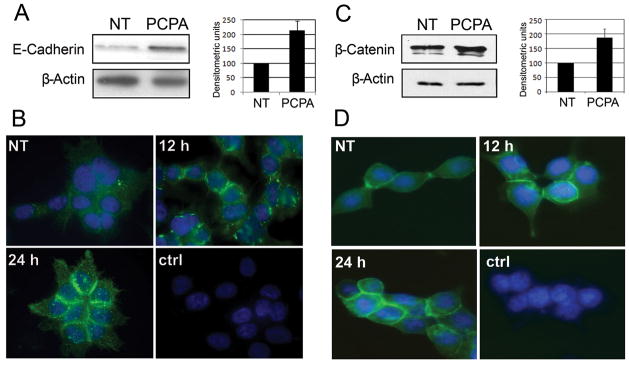

Parnate treatment of cancer cell lines should phenocopy the changes in the expression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers induced by Slug down-regulation (Supplementary Figure 3); indeed, Parnate treatment of HCT116, Colo205 and HTLA230 cells induced an increase in the expression of the epithelial markers E-Cadherin, Occludin and Desmoplakin detected by real time Q-PCR (Figure 4). In HTLA230 cells, Parnate treatment induced also a decrease in the expression of the mesenchymal markers Vimentin and N-Cadherin (Figure 4), while expression of these two markers in HCT116 and Colo205 cells was too low to be affected by the treatment (not shown). Expression of members of the miR-200 family which regulate EMT via ZEB1 and is suppressed by ZEB1 (at least in the case of miR-200c) (6)did not show significant variations after Parnate treatment of HCT116 cells (not shown). In Parnate-treated HCT116 cells, the increase in E-Cadherin mRNA transcripts was accompanied by a corresponding increase (at least two-fold) in protein levels (Figure 5A). Immunofluorescence microscopy confirmed such increase and revealed a distinctive “zipper-like” pattern of E-Cadherin expression which is indicative of adherens junctions’ formation between neighboring cells (Figure 5B; compare untreated and Parnate-treated cells).

Figure 4. Expression of EMT markers detected by real time Q-PCR in Parnate-treated (12 hours) tumor cells.

Data represent the mean + SD of two experiments. Changes in the expression induced by Parnate treatment are all statistically significant except for those of Occludin and Desmoplakin in Colo205 cells.

Figure 5. Expression of E-cadherin and β-Catenin in Parnate-treated HCT116 cells.

(A,C) Western blot (left) and densitometry (right) of E-Cadherin (A) and β-Catenin (C) expression in untreated (NT) and Parnate-treated (100 μM, 24 h) HCT116 cells. Levels of β-actin were measured as loading control; (B,D) Immunofluorescence micrographs of E-Cadherin (B) and β-Catenin (D) expression in untreated (NT) and Parnate-treated (12 and 24 h) HCT116 cells. Ctrl represents cells treated only with the fluorescent secondary antibody. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Original magnification was 100X.

Treatment with Parnate also induced an increase in the expression of β-Catenin as revealed by western blotting and immunofluorescence (Figure 5C and 5D, respectively).

Effect of a cell-permeable SNAG domain Slug peptide

The role of the SNAG domain of Slug for migration and invasion of cancer cells was also investigated upon treatment with a cell-permeable SNAG domain Slug peptide (TAT-SNAG) expected to function as a competitive inhibitor of the interaction between Slug and LSD1. Upon treatment with a single dose of 10μM, the TAT-SNAG peptide was readily taken up by HCT116 cells exhibiting a half-life of approximately 120 min (not shown).

First, we assessed whether the TAT-SNAG peptide added to the cell lysate of 293T cells co-expressing Slug and LSD1 blocked the interaction of these two proteins; as shown in Figure 6A, the TAT-SNAG peptide markedly reduced the amount of Slug in complex with LSD1 while the TAT peptide alone had only a modest effect. Then, we performed luciferase assays in HCT116 cells to test whether treatment with the TAT-SNAG peptide suppressed the inhibitory effect of Slug on the activity of the E-cadherin promoter; as expected, ectopically expressed Slug repressed E-cadherin promoter-driven luciferase activity and treatment with the TAT-SNAG peptide blocked the effect of Slug (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Effect of TAT-SNAG peptide on: Slug-LSD1 interaction, Slug-dependent repression of the E-cadherin promoter, migration, invasion, proliferation and EMT marker levels of HCT116 cells.

(A) Western blot (left) and densitometry (right) of HA-tagged LSD1, Slug and p53 expression in total lysate or peptide (TAT or TAT-SNAG)-treated anti-FLAG-LSD1 IPs from 293T cells co-expressing LSD1 and Slug; (B) histogram shows E-Cadherin-driven luciferase activity in HCT116 cells, untreated or treated with the TAT-SNAG or the TAT peptide. Data (mean ± S.D. of two experiments performed in duplicate) are presented as % change in luciferase activity compared to that of cells transfected with the empty vector only taken as 100. * indicates that the increase in luciferase activity of TAT-SNAG-treated cells is statistically significant; (C) microphotographs show repopulation of wounded area of TAT-SNAG- or TAT peptide-treated cells; on the right, histograms represent accurate measure of wounds taken at 0 and 72h for each treatment to calculate the migration rate; data are means ± S.D. from two independent experiments; (D) histogram shows invasion inhibition (expressed as % of untreated (NT) cells taken as 100) in TAT-SNAG- or TAT-peptide-treated HCT116 cells; microphotographs show representative fields of Giemsa-stained lower membranes of the Boyden chambers; (E) histogram shows number of untreated and TAT-SNAG- or TAT-peptide-treated cells counted by trypan blue exclusion; representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate; (F) expression of EMT markers detected by real time Q-PCR in untreated (NT) and TAT-SNAG-treated (12 hours) HCT116 cells. Data represent the mean + SD of two experiments. Changes in RNA levels induced by TAT-SNAG treatment are all statistically significant (p<0.05; Student’s t test); (G) E-Cadherin expression in TAT-SNAG-treated HCT116 cells. Western blot (left) and densitometry (right) of E-Cadherin levels in untreated (NT) and TAT-SNAG-treated (24 h) HCT116 cells. Expression of β-actin was measured as loading control.

We also investigated the effect of the cell-permeable TAT-SNAG peptide on the migration and invasiveness of HCT116 cells. In a wound healing assay performed as described above, treatment of HCT116 cells with the TAT-SNAG peptide markedly reduced repopulation of the wounded area compared to treatment with the TAT peptide alone (Figure 6C); likewise, HCT116 cells incubated with the TAT-SNAG peptide in the upper part of Matrigel-coated chambers were markedly less invasive of those treated with the TAT peptide alone (Figure 6D). Neither the TAT-SNAG nor the TAT peptide alone had any effect on the proliferation of HCT116 cells (Figure 6E). Like Parnate-treated cells, TAT-SNAG-treated HCT116 cells exhibited a 2- to 3-fold increase in the expression of the epithelial markers E-Cadherin, Desmoplakin and Occludin (Figure 6F and G). Treatment with the TAT-SNAG peptide also inhibited migration and invasiveness, but not proliferation, of p53-null HCT116 cells (Supplementary Figure 4).

Discussion

The Snail and Slug proteins play an essential role in developmental (38) and cancer-associated EMT (19,20,39); mechanistically, the effects appear to be mediated by downregulation of the expression of a number of target genes (eg., E-Cadherin) whose promoters are bound via the C-terminal “zinc fingers” and repressed by chromatin-modifying proteins recruited by the N-terminal “SNAG domain”. The histone demethylase LSD1 protein is one of those recruited to the E-cadherin promoter via the “SNAG domain” of Snail (29–31) and this interaction may be important for the EMT-inducing effects of Snail/Slug proteins because migration and invasion of cancer cells is similarly suppressed by either Snail or LSD1 RNA interference (29). We assessed directly the biological consequences of disrupting protein interactions involving the SNAG domain of Snail/Slug in cancer cells treated with Parnate, an inhibitor of the amine oxidase domain of LSD1 required for its binding to Snail, or exposed to a cell permeable peptide corresponding to a highly conserved segment of the “SNAG domain” which includes amino acids required for transcription repression. Parnate and the TAT-SNAG peptide blocked the interaction of LSD1 with Slug, rescued the Slug-dependent repression of the E-cadherin promoter activity and suppressed the Slug/Snail-regulated motility and invasion of cancer cells of different origin and genetic background. Consistent with the concept that the biological effects of Parnate and the TAT-SNAG peptide depend on disruption of the Slug-LSD1 interaction, silencing of LSD1 or Slug led to decreased migration and invasion of tumor cell lines and modulation of EMT marker levels (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3). Together, these studies support the importance of the SNAG domain-LSD1 interaction for the EMT-inducing effects of Slug/Snail, although it cannot be excluded that Parnate or the TAT-SNAG peptide used in our assays may have functioned through other pathways or blocked other protein-protein interactions required for the biological effects of these E-box binding proteins.

Of interest, neither Parnate nor the TAT-SNAG peptide had any noticeable effect on proliferation of the cancer cell lines utilized in our studies; this indicates that their effects on the motility and invasion of cancer cells are specific and suggests that these compounds (or, more likely, their derivatives) may be used in combination with more conventional cytotoxic drugs or, individually, after surgery or chemotherapy to target residual metastasis-proficient cells. However, potential toxic effects on normal cells need to be examined because both compounds are likely to have pleiotropic effects on gene expression.

Parnate is a monoamine oxidase inhibitor approved by the FDA since 1985 for treatment of severe depression, but its use is limited by serious side effects caused by high concentration of serotonin and dopamine and paradoxical increase of epinephrine and norepinephrine levels. Moreover, the IC50 of Parnate for inhibition of LSD1 appears to be higher than that for monoamine oxidase A and B (40,41), possibly preventing prolonged treatments in cancer patients.

The use described here of the TAT-SNAG peptide to target transcription repression complexes is conceptually similar to that of peptidomimetic inhibitors of the transcription repressor BCL6 which consist of the BCL6-binding domain of the N-CoR and SMRT corepressors (42). One of these, RI-BP1, has shown potent anti-lymphoma and anti-leukemia effects in vitro and in mice (43,44).

In aggregate, our findings raise the possibility that improved approaches to target Snail/Slug-dependent transcription repression complexes may lead to the development of novel drugs selectively inhibiting the invasive potential of cancer cells.

Supplementary Material

(A) microphotographs show repopulation of wounded area of untreated and Parnate-treated cells; on the right, histograms represent accurate measure of wounds taken at 0 and 72h for each treatment to calculate the migration rate; data are means ± S.D. from two independent experiments; (B) histograms show inhibition of invasion (expressed as % of untreated cells taken as 100) by Parnate treatment; microphotographs show representative fields of Giemsa-stained lower membranes of the Boyden chambers; (C) histograms show number of untreated and Parnate-treated cells counted by trypan blue exclusion; representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

(A) Western blot shows LSD1 expression in HCT116 cells lentivirally transduced with pLKO-GFP-sh or pGIPZ-LSD1-sh. Levels of Slug and β-Actin were measured as control of specificity and loading; (B) histogram shows invasion inhibition (expressed as % of HCT116-GFP-sh cells taken as 100 experiments; mean +SD of three experiments) in LSD1-silenced HCT116 cells; (C) microphotographs show repopulation of wounded area of control or LSD1-silenced cells; on the right, histograms represent accurate wound measurements taken at 0 and 72h for each treatment to calculate the migration rate; data are means ± S.D. from two independent experiments.

(A) Western blot shows expression of Slug in HTLA230 cells lentivirally transduced with pLKO-GFP-sh or pLKO-Slug-sh. Levels of β-Actin were measured as loading control; (B) histogram shows invasion inhibition (expressed as % of HTLA230-GFP-sh cells taken as 100 experiments; mean +SD of three experiments) in Slug-downregulated HTLA230 cells; (C) histograms show expression of EMT markers detected by real time Q-PCR in Slug-silenced HTLA230 cells. Data represent the mean + SD of two experiments. Changes in the expression of EMT markers are all statistically significant (p>0.05; Student’s t test).

(A) microphotographs show repopulation of wounded area of untreated or TAT-SNAG- or TAT-treated cells; on the right, histograms represent accurate measure of wounds taken at 0 and 72h for each treatment to calculate the migration rate; data are means ± S.D. from two independent experiments; (B) histograms show invasion inhibition (expressed as % of untreated cells taken as 100) by TAT-SNAG- or TAT-peptide treatment; microphotographs show representative fields of Giemsa-stained lower membranes of the Boyden chamber; (C) histograms show number of untreated and TAT-SNAG- or TAT-peptide-treated cells counted by trypan blue exclusion; representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by grants of the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Modena, Fondazione Guido Berlucchi, Amici di Lino, and by NCI grant CA095111. GFA was supported by Fellowship of the Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) and is currently supported by Fondazione Angela Serra. ARS and GM are supported by a fellowship of AIRC. SC was supported by fellowships of AIRC and the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Vignola and is currently supported by a fellowship of the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Modena.

We thank Drs Steven McMahon and Andrea Morrione for their critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interests were disclosed.

References

- 1.Steeg PS. Tumor metastasis: mechanistic insights and clinical challenges. Nat Medicine. 2006;12:895–904. doi: 10.1038/nm1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valastyan S, Weinberg RA. Tumor metastasis: molecular insights and evolving paradigms. Cell. 2011;147:275–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta GP, Massagué J. Cancer metastasis: building a framework. Cell. 2006;127:679–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin-Belmonte F, Perez-Moreno M. Epithelial cell polarity, stem cells and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:23–38. doi: 10.1038/nrc3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeisberg M, Neilson EG. Biomarkers for epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1429–37. doi: 10.1172/JCI36183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prasad CP, Rath G, Mathur S, Bhatnagar D, Parshad R, Ralhan R. Expression analysis of E-cadherin, Slug and GSK3beta in invasive ductal carcinoma of breast. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:325. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Logullo AF, Nonogaki S, Pasini FS, Osório CA, Soares FA, Brentani MM. Concomitant expression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition biomarkers in breast ductal carcinoma: association with progression. Oncol Rep. 2010;23:313–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, et al. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCoy EL, Iwanaga R, Jedlicka P, Abbey NS, Chodosh LA, Heichman KA, et al. Six1 expands the mouse mammary epithelial stem/progenitor cell pool and induces mammary tumors that undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2663–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI37691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trimboli AJ, Fukino K, de Bruin A, Wei G, Shen L, Tanner SM, et al. Direct evidence for epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:937–45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vergara D, Merlot B, Lucot JP, Collinet P, Vinatier D, Fournier I, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in ovarian cancer. Cancer Lett. 2010;291:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brabletz T, Hlubek F, Spaderna S, Schmalhofer O, Hiendlmeyer E, Jung A, et al. Invasion and metastasis in colorectal cancer: epithelial-mesenchymal transition, mesenchymal-epithelial transition, stem cells and beta-catenin. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;179:56–65. doi: 10.1159/000084509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Usami Y, Satake S, Nakayama F, Matsumoto M, Ohnuma K, Komori T, et al. Snail-associated epithelial-mesenchymal transition promotes oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma motility and progression. J Pathol. 2008;215:330–39. doi: 10.1002/path.2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura M, Tokura Y. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the skin. J Dermatol Sci. 2011;61:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gavert N, Ben-Ze’ev A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and the invasive potential of tumors. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giroldi LA, Bringuier PP, de Weijert M, Jansen C, van Bokhoven A, Schalken JA. Role of E boxes in the repression of E-cadherin expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241:453–58. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hennig G, Behrens J, Truss M, Frisch S, Reichmann E, Birchmeier W. Progression of carcinoma cells is associated with alterations in chromatin structure and factor binding at the E-cadherin promoter in vivo. Oncogene. 1995;11:475–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Batlle E, Sancho E, Francí C, Domínguez D, Monfar M, Baulida J, et al. The transcription factor Snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:84–89. doi: 10.1038/35000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cano A, Pérez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, et al. The transcription factor Snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajra KM, Chen DY, Fearon ER. The SLUG zinc-finger protein represses E-cadherin in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1613–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta PB, Kuperwasser C, Brunet JP, Ramaswamy S, Kuo WL, Gray JW, et al. The melanocyte differentiation program predisposes to metastasis after neoplastic transformation. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1047–54. doi: 10.1038/ng1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Catalano A, Rodilossi S, Rippo MR, Caprari P, Procopio A. Induction of stem cell factor/c-Kit/slug signal transduction in multidrug-resistant malignant mesothelioma cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46706–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vitali R, Mancini C, Cesi V, Tanno B, Mancuso M, Bossi G, et al. Slug (SNAI2) down-regulation by RNA interference facilitates apoptosis and inhibits invasive growth in neuroblastoma preclinical models. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4622–30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casas E, Kim J, Bendesky A, Ohno-Machado L, Wolfe CJ, Yang J. Snail2 is an essential mediator of Twist1-induced epithelial mesenchymal transition and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:245–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alves CC, Carneiro F, Hoefler H, Becker KF. Role of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulator Slug in primary human cancers. Front Biosci. 2009;14:3035–50. doi: 10.2741/3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shioiri M, Shida T, Koda K, Oda K, Seike K, Nishimura M, et al. Slug expression is an independent prognostic parameter for poor survival in colorectal carcinoma patients. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1816–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shih JY, Tsai MF, Chang TH, Chang YL, Yuan A, Yu CJ, et al. Transcription repressor slug promotes carcinoma invasion and predicts outcome of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8070–78. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin Y, Wu Y, Li J, Dong C, Ye X, Chi YI, et al. The SNAG domain of Snail1 functions as a molecular hook for recruiting lysine-specific demethylase 1. EMBO J. 2010;29:1803–16. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baron R, Binda C, Tortorici M, McCammon JA, Mattevi A. Molecular mimicry and ligand recognition in binding and catalysis by the histone demethylase LSD1-CoREST complex. Structure. 2011;19:212–20. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin T, Ponn A, Hu X, Law BK, Lu J. Requirement of the histone demethylase LSD1 in Snai1-mediated transcriptional repression during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene. 2010;29:4896–04. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang J, Sengupta R, Espejo AB, Lee MG, Dorsey JA, Richter M, et al. p53 is regulated by the lysine demethylase LSD1. Nature. 2007;449:105–8. doi: 10.1038/nature06092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang CJ, Chao CH, Xia W, Yang JY, Xiong Y, Li CW, et al. p53 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stem cell properties through modulating miRNAs. Nature Cell Biology. 2011;13:317–23. doi: 10.1038/ncb2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim T, Veronese A, Pichiorri F, Lee TJ, Jeon YJ, Volinia S, et al. p53 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition through microRNAs targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2. J Exp Med. 2011;208:875–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bunz F, Dutriaux A, Lengauer C, Waldman T, Zhou S, Brown JP, et al. Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science. 1998;282:1497–501. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanno B, Sesti F, Cesi V, Bossi G, Ferrari-Amorotti G, Bussolari R, et al. Slug is regulated by c-myb and is required for invasion and bone marrow homing of cancer cells of different origin. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:29434–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.089045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krause DS, Lazarides K, von Andrian UH, Van Etten RA. Requirement for CD44 in homing and engraftment of BCR-ABL-expressing leukemic stem cells. Nat Medicine. 2006;12:1175–1180. doi: 10.1038/nm1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrallo-Gimeno A, Nieto MA. The Snail genes as inducers of cell movement and survival: implications in development and cancer. Development. 2005;132:3151–61. doi: 10.1242/dev.01907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–28. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee MG, Wynder C, Schmidt DM, McCafferty DG, Shiekhattar R. Histone H3 lysine 4 demethylation is a target of nonselective antidepressive medications. Chem Biol. 2006;13:563–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt DM, McCafferty DG. trans-2-Phenylcyclopropylamine is a mechanism-based inactivator of the histone demethylase LSD1. Biochemistry. 2007;46:4408–16. doi: 10.1021/bi0618621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahmad KF, Melnick A, Lax S, Bouchard D, Liu J, Kiang CL, et al. Mechanism of SMRT corepressor recruitment by the BCL6 BTB domain. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1551–64. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00454-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cerchietti LC, Yang SN, Shaknovich R, Hatzi K, Polo JM, Chadburn A, et al. A peptomimetic inhibitor of BCL6 with potent antilymphoma effects in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2009;113:3397–405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duy C, Hurtz C, Shojaee S, Cerchietti L, Geng H, Swaminathan S, et al. BCL6 enables Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukaemia cells to survive BCR-ABL1 kinase inhibition. Nature. 2011;473:384–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) microphotographs show repopulation of wounded area of untreated and Parnate-treated cells; on the right, histograms represent accurate measure of wounds taken at 0 and 72h for each treatment to calculate the migration rate; data are means ± S.D. from two independent experiments; (B) histograms show inhibition of invasion (expressed as % of untreated cells taken as 100) by Parnate treatment; microphotographs show representative fields of Giemsa-stained lower membranes of the Boyden chambers; (C) histograms show number of untreated and Parnate-treated cells counted by trypan blue exclusion; representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

(A) Western blot shows LSD1 expression in HCT116 cells lentivirally transduced with pLKO-GFP-sh or pGIPZ-LSD1-sh. Levels of Slug and β-Actin were measured as control of specificity and loading; (B) histogram shows invasion inhibition (expressed as % of HCT116-GFP-sh cells taken as 100 experiments; mean +SD of three experiments) in LSD1-silenced HCT116 cells; (C) microphotographs show repopulation of wounded area of control or LSD1-silenced cells; on the right, histograms represent accurate wound measurements taken at 0 and 72h for each treatment to calculate the migration rate; data are means ± S.D. from two independent experiments.

(A) Western blot shows expression of Slug in HTLA230 cells lentivirally transduced with pLKO-GFP-sh or pLKO-Slug-sh. Levels of β-Actin were measured as loading control; (B) histogram shows invasion inhibition (expressed as % of HTLA230-GFP-sh cells taken as 100 experiments; mean +SD of three experiments) in Slug-downregulated HTLA230 cells; (C) histograms show expression of EMT markers detected by real time Q-PCR in Slug-silenced HTLA230 cells. Data represent the mean + SD of two experiments. Changes in the expression of EMT markers are all statistically significant (p>0.05; Student’s t test).

(A) microphotographs show repopulation of wounded area of untreated or TAT-SNAG- or TAT-treated cells; on the right, histograms represent accurate measure of wounds taken at 0 and 72h for each treatment to calculate the migration rate; data are means ± S.D. from two independent experiments; (B) histograms show invasion inhibition (expressed as % of untreated cells taken as 100) by TAT-SNAG- or TAT-peptide treatment; microphotographs show representative fields of Giemsa-stained lower membranes of the Boyden chamber; (C) histograms show number of untreated and TAT-SNAG- or TAT-peptide-treated cells counted by trypan blue exclusion; representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.