Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Gastro-Intestinal Stromal Tumours (GISTs) are rare with an estimated incidence of only 11–15 per million. In pregnancy, GISTs are an extremely rare occurrence and are thus complex to manage from an ethical, surgical and oncological perspective.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

We present the first reported case in the literature of a successful combined lower segment caesarean section (LSCS) and a tumour resection in a 31-year-old pregnant patient presenting with a small bowel GIST.

DISCUSSION

We compare and contrast our case with other reported cases of GIST resection in pregnancy and discuss the challenges faced by both patients and clinicians.

CONCLUSION

Our case demonstrates that a combined LSCS and GIST resection is feasible. In addition, our case highlights the importance of both the multidisciplinary setting and the consideration of patients’ wishes in the successful management of this complex group of patients.

Keywords: GIST, Gastro-Intestinal Stromal Tumour, Pregnancy

1. Introduction

Gastro-Intestinal Stromal Tumours (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumours of the gastro-intestinal tract.1 They are rare with an estimated annual incidence of only 11–15 per million.2,3 GISTs are found equally in both genders and commonly present in the fifth to seventh decade.4,5 They thus present very rarely in pregnancy. The exact incidence in pregnancy is unknown as there are few reported cases in the literature. The management of pregnant patients presenting with GISTs poses a challenge to both general surgeons and obstetricians. We present the first case report in the literature to describe a combined lower segment caesarean section and a tumour resection in a pregnant women presenting with a GIST.

2. Presentation of case

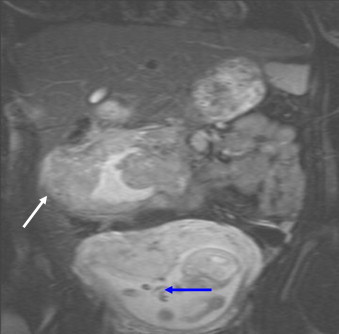

A 31-year-old woman of Chinese origin, gravida 2 para 0, presented at 18 weeks gestation to the antenatal clinic complaining of lethargy, dizziness and shortness of breath on exertion. She had no significant past medical history, normal antenatal consultations to date, and was not on regular medications. Routine investigations demonstrated a microcytic anaemia; haemoglobin 7.8 g/dl, MCV 72.9 fl, platelets 539, and serum ferritin of 13 μg/l. On examination, her uterus was consistent for the date of gestation. Per vaginal examination revealed a large palpable mass in the right adnexa. A subsequent ultrasound demonstrated an ‘irregular mass of mixed echogenicity measuring 106.4 mm × 68.7 mm × 109.5 mm’ suggestive of a fibroid or an ovarian pathology. A Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan of the abdomen and pelvis was thus organised and demonstrated an irregular 12 cm soft tissue mass in the right upper quadrant (Fig. 1). The mass appeared to involve the transverse mesocolon as well as part of the small bowel mesentery with associated extensive necrosis (Fig. 1). An ultrasound guided biopsy of the soft tissue mass was organised at 30 weeks gestation, confirming a GIST of uncertain malignant potential (Fig. 2). It was decided at a multidisciplinary meeting to perform an elective combined caesarean section and tumour resection.

Fig. 1.

Coronal MRI demonstrating intrauterine foetus (blue arrow) and intraabdominal GIST (white arrow). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

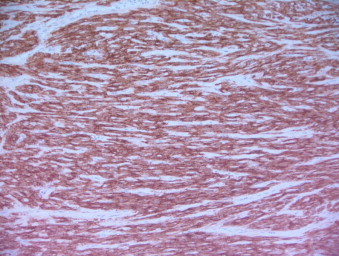

Fig. 2.

CD-117-labelled immunohistochemistry of resected tumour, confirming GIST (200× magnification).

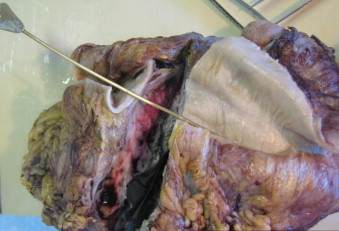

At 36 weeks gestation, a healthy baby girl weighing 2.15 kg was delivered by a lower segment caesarean section through a midline laparotomy. The tumour was found to arise from the mid jejunum and also involved the ascending colon. There was no evidence of intra abdominal metastasis. An extended right hemicolectomy and segmental resection of the jejunum with an end-to-side ileocolic and a jejunojejunal anastomoses were successfully performed. The resected tumour weighed 2.5 kg (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Macroscopic appearance of resected tumour and adherent large bowel.

Histology confirmed a GIST arising from the small bowel wall with infiltration into the serosal aspect of colon but no muscular invasion. All resection margins were clear. Immunohistochemistry confirmed strong positivity for CD117 (c-kit) and focal strong positivity of CD34 with a mitotic rate of >50/50 HPF (high power field). Subsequent gene mutation analysis demonstrated a large deletion in exon 11 C-KIT gene.

The patient made an uneventful post-operative recovery and was successfully discharged. She was commenced on a 2-year course of adjuvant Imatinib. At a 2-year follow up, the patient was asymptomatic with no evidence of recurrence on computed tomography (CT) imaging.

3. Discussion

GISTs are known to arise from KIT positive Cajal cells, that are spindle cells located close to the Auerbach plexus.6,7 C-KIT is a tyrosine kinase receptor for stem cell factor and it is the mutation of this receptor that is thought to be crucial in the development of GISTs.6 Exon 11 deletions, as was encountered in our case, are the most common form of KIT mutation found in small bowel GISTS.6

The finding of an intra-abdominal GIST in pregnancy is extremely rare with only three other cases describing this finding in the literature (Table 1).8–10 The most common sites of gastrointestinal tract GISTs are the stomach (60–75%) followed by the small intestine (20–30%).11,12 Interestingly, perhaps due to the limited number of studies, there was no evident difference in incidence of gastric and small intestine GISTs in the reported cases (Table 1). The tumour size, upon presentation, can vary considerably ranging from anywhere between 2 and 20 cm.5 This is consistent with the reported cases of GISTs in pregnancy with the tumour sizes ranging between 4 and 17 cm (Table 1). Metastatic spread is rare, usually occurring by either trans-coelomic or haematogenous spread to organs such as the liver, lung and bone.4,5

Table 1.

Reported cases of GISTs presenting during pregnancy.

| Author | Age | Signs and symptoms | Site of GIST | Diagnostic investigations | Surgery and mode of delivery | Post-operative complications | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valente et al.8 | 32 | Abdominal pain, ascites | Lesser curvature of stomach, peritoneum | 1. US | Exploratory Laparotomy, followed by ELSCS (28/40) | Post-operative foetal distress, Premature delivery | None – at 9 months |

| Lanzafame et al.9 | 29 | Abdominal pain, ascites | Stomach wall | 1. US | Laparotomy – gastric wedge resection (method of delivery not specified) | – | – |

| 2. Paracentesis | |||||||

| Scherjon et al.10 | 25 | Large for dates | Jejunum, appendix, rectouterine pouch, spleen | 1. US | 1. GIST resection en bloc, including jejunum, appendix and spleen | 2 further laparotomies | Yes – at 6 years |

| 2. Doppler | 2. (SVD 41/40) | ||||||

| 3. Gastroscopy | |||||||

| Our case | 31 | Tiredness, breathlessness, dizziness | Mid-jejunum infiltrating ascending colon | 1. MRI | Combined LSCS and extended right hemicolectomy/small bowel resection (36/40) | Pre-term delivery | None – at 2 years |

| 2. US guided biopsy |

US, ultrasound; MRI, Magnetic Resonance Imaging; ELSCS, emergency lower segment caesarean section; SVD, Spontaneous Vaginal Delivery; LSCS, lower segment caesarean section.

In our case and those previously reported, the presentation and symptoms of GISTs in pregnancy have been non-specific (Table 1). In general, small asymptomatic GISTs are usually diagnosed incidentally during endoscopy or surgery for other indications.11 Symptoms usually occur as a result of the ‘mass effect’ of the tumour but can occasionally present with microcytic anaemia or haematochesia as a result of gastrointestinal bleeding.11,13 Rarely, patients may present acutely due to either an obstruction or a perforation of a viscus.14 Constitutional symptoms are not uncommon in pregnancy and thus the presentation of GISTs in pregnancy can pose a diagnostic challenge.8

Attaining a diagnosis in pregnancy is difficult, as it is normally recommended that computed tomography is undertaken to accurately stage the tumour.11,15 Ultrasound is safe in pregnancy and was used in all the reported cases to initially assess the tumour (Table 1). However, ultrasound imaging is non-specific. MRI scanning is recognised as a helpful imaging modality in the diagnosis of GISTs and in pregnancy this is the imaging of choice.11 A tissue biopsy will stain positive on immunohistochemistry for CD117 and CD34 in 90% and 70% of GISTs respectively.12 However, care must be taken as there is a theoretical risk of tumour cell seeding and it should only really be undertaken if there is a clear diagnostic uncertainty.11 Once the diagnosis of a GIST has been confirmed in the absence of metastatic disease, a surgical resection remains the only curative option.1,11 There remains some controversy about GISTs smaller than two cm with current European guidelines recommending close follow up for gastric or duodenal lesions less than two centimetres and resecting only if there is an increase in size.15

Surgical management of small bowel GISTS, as was found in our case, should include an exploratory laparotomy at the time of surgery to exclude metastases.11 Small bowel GISTs can be safely excised using a segmental resection due to the fact that GISTs rarely metastasise lymphatically.11 During tumour resection, care should be taken to ensure that the pseudo-capsule remains intact to prevent the spread of tumour cells.11 The difficulty in the surgical management of pregnant patients presenting with GISTs is deciding the optimal timing of the surgery; the balance of good oncological repsonse and minimising injury to the foetus. Unfortunately, due to the rarity of the condition there are no current guidelines for the management of GISTs in pregnancy. In the other reported cases, the tumour resection was performed antenatally (Table 1). However, one of the antenatal resections resulted in an emergency LSCS 1 h post operatively due to foetal distress (Table 1). The timing of surgery in our case was largely dictated by the patient's wishes, as she did not want to have an antenatal resection, and thus it was decided in a multi-disciplinary setting, to perform a LSCS followed by a resection of the tumour in one sitting. It is clear that there is no definitive answer to the question of what constitutes the optimal timing of surgery in these patients and thus any key management decisions should be made in a multidisciplinary (MDT) setting involving oncologists, general surgeons and obstetricians whilst also taking into account the patients’ wishes.

The use of Imatinib in a neo-adjuvant and adjuvant setting for GISTs remains controversial with limited survival data available from current trials.1 Neo-adjuvant Imatinib is currently recommended if a RO resection cannot be attained or where reduction of the tumour size will reduce the risk of mutilating surgery.1 However as little is known on the teratogenic effects of Imatinib, its use during gestation should only be used on a case to case basis.16 Adjuvant Imatinib is recommended for localised GISTs where there is a high risk of recurrence.1 The risk of recurrence is stratified according to the size and mitotic count of the tumour.1 Furthermore, the site of the GIST is also a contributing factor in determining the risk of recurrence with small bowel GISTs having a higher risk than gastric GISTs.1,11 A size greater than five cm with a mitotic count greater than 5/50, as was found in our case, stratifies a GIST as ‘high’ risk and therefore adjuvant Imatinib therapy was commenced.

There are no clear international or national guidelines on the optimal follow up for patients with GISTs.1,15,17 Most recurrences occur in the liver or the peritoneum and will thus be best detected with CT scanning at appropriate interval follow up.15

4. Conclusion

This is the first reported case of a combined successful delivery and GIST resection in a pregnant patient. Our case demonstrates the complexity of managing pregnant patients presenting with GISTs from an ethical, surgical and oncological perspective. There are no guidelines on the optimal timing of the tumour resection in pregnancy and thus key management decisions should be taken in a MDT setting whilst taking into account the patient's wishes.

Conflict of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author's contributions

Dr. Nora Haloob is a writer and assistant in theatre for the case in question. Mr. Alistair Slesser is a co-writer. Mr. Abdul Rahim Haloob is an obstetrician and main clinician responsible for patient care. Mr. Farrukh Khan is an upper GI surgeon and allied clinician responsible for patient care. Dr. Bostanci, locum consultant histopathologist, is responsible for slicing and analysing surgical specimen. Dr. Abdulla is a consultant histopathologist and clinical lead responsible for obtaining the histopathological slides as the images seen in this paper.

References

- 1.Blay J.Y., von Mehren M., Blackstein M.E. Perspective on updated treatment guidelines for patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer. 2010;116(November (22)):5126–5372. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nilsson B., Bümming P., Meis-Kindblom J.M., Odén A., Dortok A., Gustavsson B. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era – a population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer. 2005;103(February (4)):821–829. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tryggvason G., Gíslason H.G., Magnússon M.K., Jónasson J.G. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in Iceland, 1990–2003: the icelandic GIST study, a population-based incidence and pathologic risk stratification study. International Journal of Cancer. 2005;117(November (2)):289–299. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miettinen M., Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours-definition, clinical, histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic features and differential diagnosis. Virchows Archiv. 2001;438(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s004280000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graadt van Roggen J., Van Velthuysen M.L.F., Hogendoorn P.C.W. The histopathological differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal tumours. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2001;54(2):96–103. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.2.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miettinen M., Lasota J. Histopathology of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2011;104(December (8)):865–873. doi: 10.1002/jso.21945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kindblom L.G., Remotti H.E., Aldenborg F., Meis-Kindblom J.M. Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT): gastrointestinal stromal tumors show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. American Journal of Pathology. 1998;152(May (5)):1259–1269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanzafame S., Minutolo V., Caltabiano R., Minutolo O., Marino B., Gagliano G. About a case of GIST during Pregnancy with immunohistochemical expression of epidermal growth factor receptor and progesterone receptor. Pathology, Research and Practice. 2006;202(2):119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scherjon S., Lam W.F., Gelderblom H., Jansen F.W. Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor in Pregnancy: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2009. 2009:456402. doi: 10.1155/2009/456402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valente P.T., Fine B.A., Parra C., Schroeder B. Gastric Stromal tumour with peritoneal nodules in Pregnancy: tumour spread or rare variant of difuse leimyomatosis. Gynecologic Oncology. 1996;63(December (3)):392–397. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frankel T.L., Wong S.L. Surgical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Current Problems in Cancer. 2011;35(September–October (5)):271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fletcher C.D., Berman J.J., Corless C., Gorstein F., Lasota J., Longley B.J. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Human Pathology. 2002;33(May (5)):459–465. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.123545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das A., Wilson R., Biankin A.V., Merrett N.D. Surgical therapy for gastrointestinal stromal tumours of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2009;13(July (7)):1220–1225. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0885-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miettinen M., Sarlomo-Rikala M., Sobin L.H., Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors and leiomyosarcomas in the colon: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 44 cases. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2000;24(October (10)):1339–1352. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200010000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casali P.G., Blay J.Y. ESMO/CONTICANET/EUROBONET Consensus Panel of Experts, Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology. 2010;21(May (Suppl. 5)):v98–v102. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali R., Ozkalemkas F., Kimya Y., Koksal N., Ozkocaman V., Gulten T. Imatinib use during pregnancy and breast feeding: a case report and review of the literature. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2009;280(August (2)):169–175. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0861-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grotz T.E., Donohue J.H. Surveillance strategies for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2011;104(December (8)):921–927. doi: 10.1002/jso.21862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]