Abstract

Bowel Injuries are uncommonly associated with traumatic abdominal injuries. However, they are associated with significant morbidity and mortality and require operative intervention unlike solid organ injuries. Hence, early diagnosis is of paramount importance. Computed tomographic (CT) scan is a well-established and highly accurate imaging modality for the detection of solid organ injury after blunt abdominal trauma. However, its role in diagnosing hollow viscus injury remains controversial. The aim of our study was to analyze the accuracy of multidetector CT (MDCT) in the diagnosis of bowel injury. Imaging features of surgically proven cases of bowel injury were identified over 8-year period (i.e., from January 2003 to December 2010) and were retrospectively analyzed. There were 32 patients with age range of 3–90 years. There was only one female. Sensitivity of various CT signs specific to bowel injury (i.e., extravasation of contrast and discontinuity of bowel wall) was 15.62, and 28.12%, respectively. While that of signs suggestive of bowel injury were pneumoperitoneum, 62.5%; gas in the vicinity, 40.62%; bowel wall hematoma, 21.87%; bowel wall thickening, 75%; ascites, 78.12%; mesenteric hematoma, 46.87%; and mesenteric stranding, 40.62%. Based on the major and minor signs, a diagnosis of bowel injury could be made in all patients except one. The minor signs showed a higher sensitivity than the major signs. Hence, we recommend that multidetector CT should be used as the modality of choice in case of patients with suspected bowel injury. We also suggest that the minor signs should be given as much importance as the major signs.

Keywords: MDCT, Missed injuries, Minor signs

Introduction

Traumatic injuries remain the leading cause of death among patients aged 12–45 years and continue to account for substantial morbidity in this population. Over 41,000 people died from injuries in motor vehicle crashes in 2000 [1]. Blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries (BBMIs) occur in approximately 1–5% of patients suffering from blunt abdominal trauma [2, 3]. Although these occur rarely, there is significant associated morbidity, including fatal peritonitis, sepsis, and life-threatening hemorrhage. Clinically, findings of physical examination may initially be benign, with delayed onset of peritoneal signs [2]. Detection of these injuries is of importance as, in contradistinction to the trend of nonoperative management of solid intra-abdominal organ injuries, the optimal treatment of bowel and mesenteric injuries remains early surgical repair. A delay in diagnosis and hence treatment increases morbidity and mortality [4, 5]. In fact, one recent study has demonstrated an association between increased morbidity and mortality with a delay as brief as 5 h in the surgical treatment of small bowel injury [6].

In alert patients, physical examination is the method that is regarded best for detecting significant abdominal injury. However, in hemodynamically stable blunt trauma patients with altered mental status, abdominal/pelvic computed tomographic (CT) scan is the modality of choice. These injuries can be missed on diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) in case of small perforations walled off by other loops of bowel or by the omentum and minimal peritoneal contamination [7]. CT scan with oral and intravenous contrast began to be used in the early 1980s to evaluate the victims of blunt abdominal trauma. Now, it is well established as a highly accurate imaging modality for the detection of solid organ injury after blunt abdominal trauma. However, its role in diagnosing hollow viscus injury remains controversial with a false-negative rate of 15% [8]. The aim of our study was to analyze the accuracy of multidetector CT (MDCT) in the diagnosis of bowel injury.

Material and Method

Over an 8-year period (January 2003 to December 2010), 32 surgically proven cases with bowel involvement following blunt abdominal trauma were identified. These were retrospectively reviewed for demographic characteristics and mode of injury. Retrospective blinded review of the CT scan of these patients was also performed by two radiologists individually having an experience of 11 years and 7 years in the related field, and the findings were tabulated. All CT scans were performed on four-detector CT scan.

Results

Thirty-two cases were identified. Age range was 3–90 years (mean 34 years and median 28 years). There was only one female. Road traffic accident was the commonest cause seen in 27/32 cases. The rest of the causes included handle bar injury, fall from swing, fall from height, fall from scooter, and tube well engine belt injury in one case each. Signs specific for bowel injury, which include extravasation of contrast, were seen in 5/32 cases (sensitivity of 15.62%) (Fig. 1); discontinuity of the bowel wall was seen in 9/32 cases (28.12%) (Figs. 1 and 2). Signs suggestive of bowel injury, which include mesenteric hematoma, were seen in 15/32 (sensitivity of 46.87%) (Fig. 3); mesenteric stranding in 13/32 (sensitivity of 40.62%); pneumoperitoneum in 20/32 (sensitivity of 62.5%); gas in the vicinity in 13/32 (sensitivity of 40.62%) (Fig. 3); bowel wall hematoma in 7/32 (sensitivity of 21.87%) (Fig. 4); bowel wall thickening in 24/32 (sensitivity of 75%) and ascites in 25/32 (sensitivity of 78.12%). Loculated collection was seen 7 patients.

Fig. 1.

Axial contrast enhanced CT scan of a 10 year old female child who reported 7 hrs following handle bar injury, reveals injury to the first part of the duodenum with extravasation of contrast. There is associated massive disruption of the pancreatic head

Fig. 2.

Axial contrast enhanced CT scan of a 60 year old male patient who presented 10 hrs following road traffic accident, reveals break in the continuity of descending colon and massive pneumoperitoneum

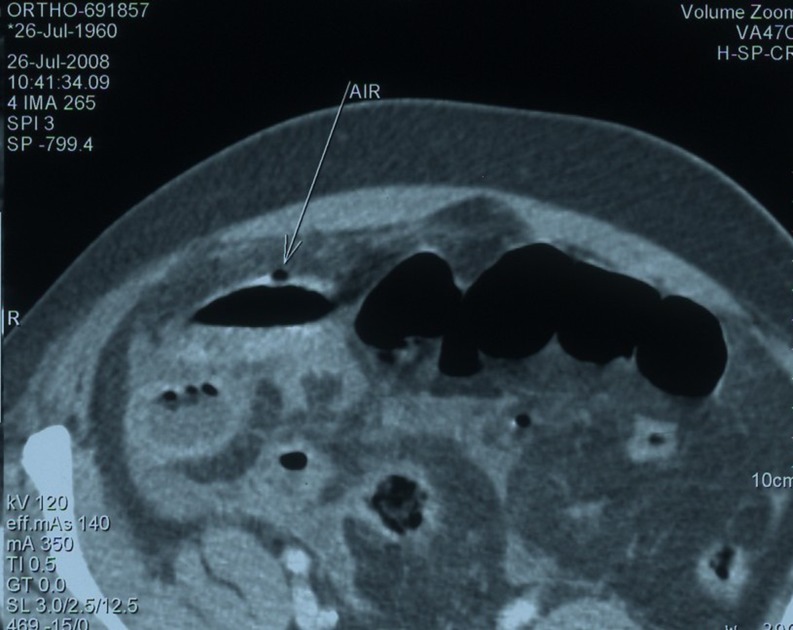

Fig. 3.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan of a 48 year old Male patient reveals air in the viscinity of bowel with mesenteric hematoma and stranding. Pre-operatively there was mesenteric tear and resultant ileal gangrene

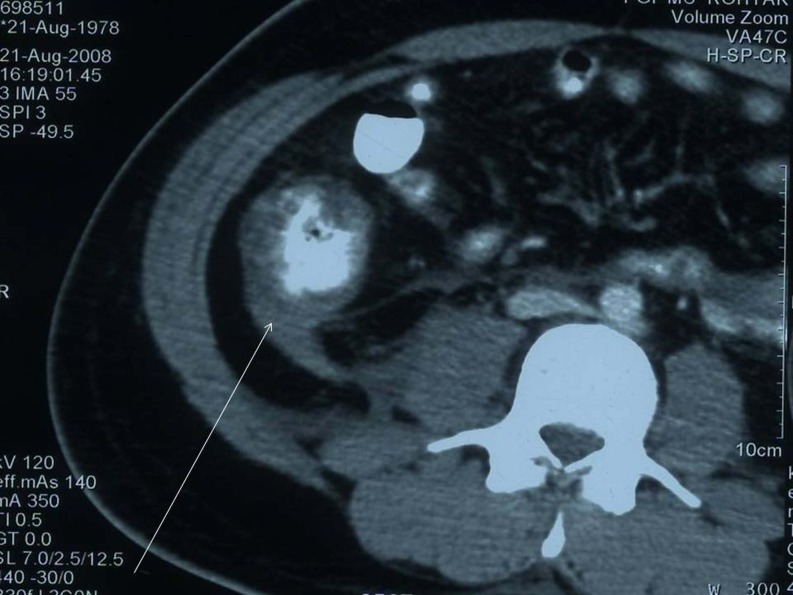

Fig. 4.

Patient of head trauma with no illicitable abdominal signs was found to have gut wall hematoma of the caecum and ascending colon with hematoma of mesocolon and retroperitoneal fluid, on CT scan examination. Preoperatively there was tear in mesocolon with Gangrene of ascending colon

On CT scan the site of injury was identified as jejunal in 11/32 cases, which was confirmed on surgery; however, in one case sigmoid colon was also involved, which was missed on CT.

Duodenum was involved in 6/32 patients. Preoperatively, one of the cases had involvement of the duodenojejunal flexure. This patient also had injury to the transverse colon, which was missed. One of the remaining five cases was a young girl with grade V injury and associated injury to the pancreas.

Ileum was involved in 8/32 cases on CT. On operation two ileal sites were involved in one patient with complete transaction at one site and ileal gangrene due to mesenteric tear seen at the other site. One patient had multiple lacerations of terminal ileum with herniation of ileum into sigmoid colon mesenteric tear, and one patient had a large 2 cm × 1 cm perforation, 2 cm proximal to the ileocecal junction. While in the rest of the patients, mesenteric tear with ileal gangrene was seen in two patients and mesenteric tear with jejunal gangrene was seen in one patient. The patient with jejunal gangrene was misdiagnosed as ileal injury.

Large bowel was involved in 4/32 cases on CT. Out of this one patient revealed cecal gangrene due to distal mesenteric tear. In another case of transverse colon injury, hematoma stomach was missed on CT. Massive pneumoperitoneum was seen in the third case with injury to the descending colon. One case of ascending colon injury was missed on CT. This patient had injury of the ipsilateral iliac blade, which had got embedded into the right iliac fossa, and the air in this region on CT was thought to be from external source.

One patient had perforation located in the antropyloric region of the stomach with massive pneumoperitoneum. The site of injury could not be identified in this patient on imaging.

One patient only presented with intestinal hernias into rectus sheath and left psoas (Fig. 5). At operation additional hernia was noted into the lesser sac through a mesenteric tear which could not be diagnosed on CT. One patient also had lumbar hernia on the right side with herniation of only peritoneum and large gut.

Fig. 5.

Axial contrast enhanced CT scan of a 12 year old male child who presented 6 hrs following road traffic accident, reveals herniation of small bowel loops into the left Psoas muscle

Associated solid organ injury was seen in 9/32 cases. Pancreas was involved in four cases; out of these one was not identified on CT. Spleen was involved in one case, while liver was involved in four cases. In one of the cases involving liver, there was injury to the right-sided diaphragm as well. Right ureter was thick walled and enhancing and gangrene of the gall-bladder was seen in one patient each. In one patient gangrene of gall bladder was seen.

Fracture of the sacrum was seen in one patient, and in one patient iliac fracture was seen with ascending colon injury, which was missed on CT.

CT scan was performed within 6–12 h in 13 patients, between 12 and 24 h in 12 patients, and more than 24 h in 7 patients. Out of these, 10 patients were operated within 8 h, 13 within 8–24 h, and 9 more than 24 h from the time of trauma. Delay in most cases was because of transportation and referral of patients to our center. There were three deaths (9.37%), 1/13 (7.69%) in patient operated within 8–24 h and 2/09 (22.22%) in patients operated after 24 h. Two patients developed wound dehiscence, one each in 8–24-h group and more than 24-h group. Mean length of stay was 15 days with longer stays in cases of delayed time to operative interval of more than 8 h. All deaths were attributable to abdominal sepsis. One patient who developed abdominal sepsis in 8–24-h group was successfully managed.

Discussion

Bowel and mesenteric injuries from blunt abdominal trauma are infrequent and difficult to diagnose. An analysis of more than 275,000 patients with blunt abdominal trauma enrolled in the EAST Multi-Institutional Hollow Viscus Injury Research Group study, the largest retrospective hollow viscus injury to date, found the incidence of blunt colonic injury to be 0.3% and the incidence of blunt small bowel injury to be 1.1%. The most common site of full thickness injury is the jejunum and ilium, with an incidence of 81%, followed by Colon and rectum, duodenum, and stomach. The accuracy of conventional or single slice helical CT in detecting blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries has been shown in prior studies to range from 84% to 94% [9].

Motor vehicle accidents are the most common cause of these injuries. Child abuse, fall from height, sports, industrial accidents and even Heimlich manoeuvre also have been implicated in bowel and mesentery injury [5]. In our series also motor vehicle accidents were the most common cause (in 27/32 cases). The other causes were fall from height, assault and agriculture injuries etc.

The pathophysiology of injury to the small bowel & mesentery was first described by Metz. He postulated three types of trauma (1) crush injury, (2) shearing forces of bowel and mesentery at fixed point of attachment and (3) burst injury caused by increased intraluminal pressure. Approximately 25% of patients requiring surgical treatment for bowel trauma have more than one bowel injury and likely more than one mechanism [4, 5].

Bowel injuries vary from minor hematoma to perforation. Small perforations may go clinically unrecognized. Abdominal pain and peritoneal irritation may be present early after major perforations or develop slowly because bowel contents, particularly jejunal contents, are not enzymatically active and have low pH & bacterial counts. Although mesenteric lacerations can lead to significant hemorrhage and hypertension, there are also secondary effects. One quarter of cases where small bowel requires surgical treatment are the result of devascularization from mesenteric injury. Even delayed internal hernias from untreated mesenteric lacerations and strictures from scar formation can occur [5].

The greater the number of organs injured, the more likely there is associated bowel and mesenteric injury and in one third of the patients bowel and mesenteric injury coexists with pancreatic or other solid organs [5]. In our series, associated viscera injury was seen in 10/32 cases.

Yoshii et al. [10] concluded from their study that ultrasound has poor sensitivity for intestinal injuries and found that the sensitivity, specificity and accuracy were 34.7, 99.9 and 97.3% respectively. Similarly Malhotra et al. [8] stated that ultrasound fails in the diagnosis of specific injury causing the fluid and is poor in the detection of hollow viscus injury. In our series also, ultrasound detected bowel injury in 04 cases and hence the sensitivity was 12.5%.

Bowel trauma can be classified as a partial or full-thickness injury. Partial thickness bowel injury results in contusion of the bowel wall and can be seen on MDCT as a focal region of bowel wall thickening, usually greater than 3–4 mm in thickness. Although most cases of bowel wall contusion resolve spontaneously, serial physical examination or follow-up MDCT in 4–6 h are useful to demonstrate healing of this injury [9].

CT findings considered specific to full thickness bowel injury include: extraluminal oral contrast or luminal content extravasation and discontinuity of hollow viscus wall. While, CT findings considered suggestive of bowel injury consisted of: pneumoperitoneum, gas bubbles close to the injured hollow viscus, thickened (>4–5 mm) bowel wall, bowel wall hematoma, intraperitoneal fluid of unknown source [11].

In the study by Scaglione et al. [11] there were 13 surgically proven cases of bowel injury. These occured in the duodenum (03 cases), ileum (02 cases), jejunum (02 cases) colon (03 cases) and stomach (03 cases). Extravasation of intraluminal contrast was seen in 04 cases, discontinuity of hollow viscus wall was seen in 01 case. In the remaining 8/13 CT findings suggestive of bowel injury were seen and these consisted of pneumoperitoneum (06), gas bubbles close to the injured hollow viscus (03), thickened bowel wall (05), bowel wall hematoma (03) and intraperitoneal fluid of unknown source (03).

The most specific sign of full-thickness bowel wall injury was extraluminal oral contrast material with a specificity of 100%. However this was seen in only 2 of 25 patients in a study by Killeen et al., as most patients have inadequate bowel wall opacification because of the often urgent nature of the CT scan examination [12]. While in a study by Brofman et al. [13] it was seen in only 3/54 (6%) of patients.

Several reports associate oral contrast with adverse events. These include a delay to CT imaging while awaiting contrast transit to the proximal small bowel and the risk of vomiting and aspiration with or without a nasogastric tube [14, 15]. Allen et al. [15] found in their study of Computed tomographic scanning without oral contrast solution for blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries in abdominal trauma that the sensitivity and specificity of CT were 95.0% and 99.6%, respectively.

Bowel wall discontinuity was seen in 4/54 (7%) patients in a study by Brofman et al. They postulated that the relative infrequency of observations of this feature is likely due to small size of the discontinuities, which are evident at surgery only with careful inspection [13].

Gastric perforations are usually evident by large pneumoperitoneum on plain radiographs. In contrast, the small intestine normally contains little air and therefore pneumoperitoneum resulting from small bowel perforation is rarely detected on plain radiographs [7]. Whereas extraluminal gas was an infrequent finding in full-thickness bowel injury in previous reports [2, 16], presence of pneumoperitoneum is strongly suggestive of full thickness bowel injury in the correct clinical setting. Brofman et al. [13] stated that it was highly specific for the diagnosis of bowel perforation. It can also result from air introduced into the peritoneal cavity during diagnostic peritoneal lavage or Foley catheter placement in patients with intraperitoneal bladder rupture. Extra-alveolar air may also decompress from the thorax into the peritoneal cavity, leading to false positive diagnosis of full-thickness bowel injury [5].

Less specific signs include focal bowel wall thickening, mesenteric fat stranding with focal fluid and hematoma, and intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal fluid. When only these signs were present correlation with clinical findings is necessary. Scaglione et al. [11] found CT findings considered suggestive of bowel injury in 8/13 patients. These consisted of: pneumoperitoneum (six), gas bubbles close to the injured hollow viscus (three), thickened (>4–5 mm) bowel wall (five), bowel wall hematoma (three), intraperitoneal fluid of unknown source (three). Mesenteric injury (23 cases) was surgically observed at the level of the mesenteric vessels (17 cases), legament of Treitz (two cases), gastro-duodenal artery (one case), transverse (one case) and sigmoid mesocolon (one case).

The presence of free intraabdominal or intrapelvic fluid is usually attributed to solid organ injury when one is present. However, if free fluid is present without concomitant CT scan evidence of solid organ injury, its etiology should be evaluated and other CT signs of GI perforation should be searched for [7]. Free fluid without solid organ injury was found by Fakhry and coworkers to be associated with an 84.2% incidence of small bowel injury [17]. The combination of free fluid and pneumoperitoneum increased the sensitivity in detecting perforated small bowel injury to 97% [9]. Rodriguez et al. [18] performed meta-analysis of articles concerning the incidence and significance of free intra-abdominal fluid on CT scan of blunt trauma patients without solid organ injury and concluded that isolated finding of free intra-abdominal fluid on CT scan in patients with blunt trauma and no solid organ injury does not warrant laparotomy. Alert patients may be followed with physical examination. Patients with altered mental status should undergo diagnostic peritoneal lavage.

Albanese et al. [7] surmised from their study that the timing of the CT scan bears little relationship to the probability of an abnormal CT scan. They believed that serial physical examinations are the gold standard for diagnosing GI perforation from blunt abdominal trauma.

Killeen et al. [12] found a high level of accuracy for detection of bowel injuries, with an accuracy of 86%, sensitivity of 94%, and a positive predictive value of 92% [8]. They found the ability to predict the presence of a full thickness bowel injury was very good with accuracy of 86%, sensitivity of 92%, and specificity of 97%. The negative predictive value for detecting a full-thickness bowel injury was 96%. They found extraluminal gas in 19/25 patients with full thickness injuries (sensitivity 75%, specificity 98%, accuracy 91%. Free fluid was also a common finding of full thickness bowel injury, with a sensitivity of 76%. However the specificity of free fluid was only 39%. Janzen et al. [19] also suggest reasonable accuracy for detection of both bowel and mesenteric injuries with accuracy of 84% and 77% respectively.

Various new features of Bowel and mesenteric injury on CT have been recognized and most recent of them is beading and termination of mesenteric vessels which indicates surgically important mesenteric injury [20]. We did not identify this sign in our patients because of lack of knowledge of this sign at the time of performance of CT as ours was a retrospective study.

Delays in diagnosis of as much as 8 h [21], or in one study 5 h [6] is responsible for increased morbidity and mortality in patients with bowel and mesenteric injury. However, Thompson et al. [22] report no such findings in a study of 13 children out of which 09 were because of motor vehicular accidents. There were 9.37% deaths attributable to delayed time to operative intervention i.e of more than 08 h, in our study.

The use of the results of clinical assessment as the sole indication for surgery has led to negative laparotomy rate as high as 40%. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) has sensitivity greater than 90% for the detection of hemoperitoneum, but it is not specific and not reliable for the assessment of retroperitoneal injuries. Focused assessment with US in the trauma setting has a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 98% for the detection of free intra-abdominal fluid, but it is nonspecific with regard to organ injury [13].

Atri et al. [23] found the sensitivities of three reviewers in the diagnosis of surgically important bowel and/or mesenteric injury by four-detector CT scan ranged from 87% to 95% and specificities ranges from 48% to 84%. Ekeh et al. [24] found that missed injuries remain common in BBMI even in the current era of multislice CT scanner. According to them free fluid without solid organ injury, though not specific, continues to be an important finding and adjuncts to CT continue to be necessary for the optimal diagnosis of bowel injury. However, Yu et al. [20] state that clinical management of patients with trace amount of isolated intraperitoneal fluid is still controversial.

In this era of sophisticated equipment and trauma scan missed injuries remain common and Lawson et al. [25] in their review of trauma patients for delayed diagnosis found that the most common missed injury is bowel injury so a high index of suspicion and tertiary survey remain a mainstay of therapy. In our study 03 cases of colonic injuries, 01 of stomach, 01 of pancreas and 2 cases of internal hernias were missed which accounts for 21.8% of all patients.

Conclusion

Based on the major and minor signs a diagnosis of bowel injury could be made in all patients except one. The drawback of our study is that only surgically proven bowel injury cases were used which was possibly a source of bias and the cause of such high accuracy of MDCT in our study. The minor signs showed a higher sensitivity than the major signs. Hence, we recommend that multidetector CT be used as the modality of choice in case of patients with suspected bowel injury. We also suggest that the minor signs be given as much importance as the major signs.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

None

Sources of Conflict

None

Presentation at Meetings

None

References

- 1.Minino AM, Smith BL. Deaths preliminary data for 2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2001;49:16–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rizzo MJ, Federle MP, Griffiths BG. Bowel and mesenteric injury following blunt abdominal trauma: evaluation with CT. Radiology. 1989;173:143–148. doi: 10.1148/radiology.173.1.2781000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wisner DH, Chun Y, Blaisdell FW. Blunt intestinal injury: keys to diagnosis and management. Arch Surg. 1990;125:1319–1323. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410220103014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan O, Vlahos L, et al. The abdomen and major trauma. In: Sutton D, Robinson PJA, Jenkins JPR, Allan PL, et al., editors. Textbook of radiology and imaging. 7. China: Churchill Livingstone; 2003. pp. 691–709. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanks PW, Brody JM. Blunt injury to mesentry and small bowel: CT evaluation. Radiol Clin N Am. 2003;41:1171–1182. doi: 10.1016/S0033-8389(03)00099-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malinoski DJ, Patel MS, Yakar DO, Green D, Qureshi F, Inaba K, Brown CV, Salim A. A diagnostic delay of 5 hours increases the risk of death after blunt hollow viscus injury. J Trauma. 2010;69:84–87. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181db37f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albanese CT, Meza MP, Gardner MJ, Smith SD, Rowe MI, Lynch JM. Is computed tomography a useful adjunct to the clinical examination for the diagnosis of pediatric gastrointestinal perforation from blunt abdominal trauma in children? J Trauma. 1996;40(3):417–421. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199603000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malhotra AK, Fabian TC, Katsis SB, Gavant ML, Croce MA. Blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries: the role screening computed tomography. J Trauma. 2000;48(6):991–1000. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200006000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller LA, Shanmuganathan K. Multidetector CT evaluation of abdominal trauma. Radiol Clin N Am. 2005;43:1079–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshii H, Sato M, Yamamoto S, et al. Usefulness and limitations of ultrasonography in the initial evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1998;45(1):45–53. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199807000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scaglione M, de Lutio di Castelguidone E, Scilpi M, Merola S, Diettrich AI, Lombardo P, Romano L, Grassi R. Blunt trauma to the gastrointestinal tract and mesentery: is there a role for helical CT in the decision-making process? Eur J Radiol. 2004;50(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Killeen KL, Shanmuganathan K, Polletti PA, Cooper C, Mirvis SE. Helical computed tomography of bowel and mesenteric injuries. J Trauma. 2001;51(1):26–36. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brofman N, Atr M, Epid D, Hanson JM, Grinblat L, Chughtai T, Brenneman F. Evaluation of bowel and mesenteric blunt traum with multidetector CT. Radiographics. 2006;26:1119–1131. doi: 10.1148/rg.264055144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Federle MP. Diagnosis of intestinal injuries by computed tomography and the use of oral contrast medium. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:769–771. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(98)70238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen TL, Mueller MT, Bonk RT, Harker CP, Duffy OH, Stevens MH. Computed tomographic scanning without oral contrast solution for blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries in abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 2002;53:79–85. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200207000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breen DL, Janzen DL, Zwirewich CV, Nagy AG. Blunt bowel and mesenteric injury: diagnostic performance of CT signs. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1997;21:706–712. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199709000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fakhry S, Watts D, Luchette FA, for the EAST Multi-institutional HV1 Research group Current diagnostic approaches lack sensitivity in the diagnosis of perforated blunt small bowel injury: analysis from 275,557 trauma admissions from the EAST Multi-institutinal trial. J Trauma. 2003;54:295–306. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000046256.80836.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez C, Barone JE, Wilbanks TO, Rha C, Miller K. Isolated free fluid on computed tomographic scan in blunt abdominal trauma: a systematic review of incidence and management. J Trauma. 2002;53:79–85. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200207000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenzen DL, Zwirewich CV, Breen DJ, Nagy A. Diagnostic accuracy of helical CT for detection of blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:193–197. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(98)80099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu J, Fulcher AS, Turner MA, Cockrell C, Halvorsen RA. Blunt bowel and mesenteric injury: MDCT diagnosis. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36:50–61. doi: 10.1007/s00261-009-9593-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fakhry SM, Brownstein M, Watts DD, Baker CC, Oller D. Relatively short diagnostic delays (<8 hours) produce morbidity and mortality in blunt small bowel injury: an analysis of time to operative intervention in 198 patients from a multicentre experience. J Trauma. 2000;48:408–415. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200003000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson SR, Holland AJ. Perforating small bowel injuries in children: influence of time to operation on outcome. Injury. 2005;36:1029–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atri M, Hanson JM, Grinblat L, Brofman N, Chughtai T, Tomlinson G. Surgically important bowel and/or mesenteric injury in blunt trauma: accuracy of multidetector CT for evaluation. Radiology. 2008;249:524–533. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2492072055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ekeh AP, Saxe J, Walusimbi M, Tchorz KM, Woods RJ, Anderson HL, 3rd, McCarthy MC. Diagnosis of blunt intestinal and mesenteric injury in the era of multidetctor CT technology—are results better? J Trauma. 2008;65:354–359. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181801cf0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawson C, Daley BJ, Ormsby CD, Enderson B. Missed injuries in the era of the trauma scan. J Trauma. 2011;70:452–456. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182028d71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]