Abstract

Study objective

We describe the availability of preventive health services in US emergency departments (EDs), as well as ED directors’ preferred service and perceptions of barriers to offering preventive services.

Methods

Using the 2007 National Emergency Department Inventory (NEDI)–USA, we randomly sampled 350 (7%) of 4,874 EDs. We surveyed directors of these EDs to determine the availability of (1) screening and referral programs for alcohol, tobacco, geriatric falls, intimate partner violence, HIV, diabetes, and hypertension; (2) vaccination programs for influenza and pneumococcus; and (3) linkage programs to primary care and health insurance. ED directors were asked to select the service they would most like to implement and to rate 5 potential barriers to offering preventive services.

Results

Two hundred seventy-seven EDs (80%) responded across 46 states. Availability of services ranged from 66% for intimate partner violence screening to 19% for HIV screening. ED directors wanted to implement primary care linkage most (17%) and HIV screening least (2%). ED directors “agreed/strongly agreed” that the following are barriers to ED preventive care: cost (74%), increased patient length of stay (64%), lack of follow-up (60%), resource shifting leading to worse patient outcomes (53%), and philosophical opposition (27%).

Conclusion

Most US EDs offer preventive services, but availability and ED director preference for type of service vary greatly. The majority of EDs do not routinely offer Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–recommended HIV screening. Most ED directors are not philosophically opposed to offering preventive services but are concerned with added costs, effects on ED operations, and potential lack of follow-up.

INTRODUCTION

Background

Many emergency departments (EDs) treat a high proportion of patients with unmet primary care needs or with illnesses related to unhealthy behaviors.1 Accordingly, there has been increasing interest in complementing acute care in the ED with some elements of preventive care.1–3 During the last 3 decades, more than 40 types of ED preventive services have been reported in the peer-reviewed literature.4 However, given that most reports on ED preventive services come from academic centers (which account for only 6% of US EDs), nationwide data on the availability of ED preventive services are sparse.3 This is of particular importance since the release of the 2006 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines calling for HIV screening in all EDs.

Importance

Characterization of the availability of preventive services in US EDs would provide a frame of reference for the ongoing debate about the appropriate role of these services in ED operations among many other competing priorities for ED resources. Because ED directors generally determine which services are actually implemented, describing ED directors’ preferences for preventive services and perceived barriers to implementation would be informative for policymakers and investigators.

Goals of This Investigation

The objectives of this study were to determine (1) the availability of 11 different preventive health services in US EDs, and (2) the services that ED directors’ would prefer to implement and their perception of barriers to offering preventive services in the ED.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

The current study was a survey of ED directors from a nationally representative sample of US EDs. Surveys were mailed to ED directors up to 3 times from September 2008 to February 2009. Nonresponders were contacted through April 2009 by telephone and either faxed or e-mailed copies of the survey. The institutional review board at Stanford University School of Medicine approved this study, with a waiver of written informed consent.

Selection of Participants

The sampling frame was the 2007 National Emergency Department Inventory (NEDI), which is developed and maintained by the Emergency Medicine Network (http://www.emnet-usa.org). We randomly selected 350 (7%) of the 4,874 US EDs from the 2007 NEDI-USA database. We excluded EDs that closed after NEDI-USA 2007 was completed (n=2), which resulted in a final sample of 348 EDs.

Methods of Measurement

Eleven preventive services were chosen. Nine of the 11 services were selected from the only systematic review on ED preventive services, which was published by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Public Health and Education Task Force in 2000.2 This included the 6 services the task force recommended as having sufficient evidence of effectiveness (alcohol, HIV, and hypertension screening; pneumococcal vaccination; primary care linkage; and tobacco cessation counseling). Four services reviewed but not recommended by the task force (intimate partner violence, geriatric fall risk, and diabetes screening and insurance linkage) were included because of recent literature demonstrating some effectiveness in the ED setting.5–9 The authors selected one service not included in the systematic review (influenza vaccination) according to a recent study demonstrating effectiveness in the ED and increasing concerns about pandemic influenza.9

The survey instrument was developed in consultation with investigators of these preventive services from outside institutions. We refined the survey questions with feedback from the ED directors and emergency medicine attending physicians from the authors’ affiliated institutions (Appendix E1, available at http://www.annemergmed.com).

For each service, respondents were asked:, “Is there a system in place that routinely performs this service in your ED?” We chose this question to account for the possibility that EDs may have the capability to offer a certain service but may not routinely offer it in a systematic way.

Respondents were asked, “Of the services not available in your ED, which service would you most like to offer?” To minimize the bias of selecting a service according to order of presentation, half of the respondents received surveys with the services listed in alphabetical order, and the other half, in reverse alphabetical order.

The survey asked ED directors to state their agreement on a 5-point Likert scale with statements that convey 5 commonly perceived barriers to offering preventive services.1,4 These included increased length of stay, additional cost, lack of primary care follow-up, philosophical opposition to ED preventive care in general, and resource shifting away from acute care, leading to worse outcomes for ED patients.

For each ED surveyed, baseline characteristics were obtained from NEDI-USA 2007. These included annual visit volume, US geographic region, urban influence code, teaching hospital status, and critical access hospitals. Level I to II trauma centers were identified by cross-referencing the National Trauma Information Exchange Program. We asked respondents about additional site characteristics, including social work availability in the ED, self-reported percentage of uninsured ED patients, and measures of ED crowding used by the CDC.10

Primary Data Analysis

Research assistants double entered data to improve accuracy. Our primary data analyses included tabulations of hospital responses and descriptive statistics. All analyses were performed with Stata (version 10.0; StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Among the 348 EDs surveyed, 277 responded from 46 states, representing an 80% response rate. Overall, EDs that responded were similar to EDs nationally (Table). The only differences among nonresponders were that there were fewer teaching hospitals (1%) and trauma centers (4%) represented compared with the responders (data not shown).

Table.

Characteristics of EDs.*

| Characteristics | Responders, n=77 (80%) | 2007 NEDI-USA, n=4,874 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median annual visit volume (interquartile range) | 21,024 (7,884–37,668) | 18,903 (7,812–35,252) | |

| Hospital type | |||

| Teaching hospital | 8 | 4–11 | 6 |

| Trauma center (Level I–II)† | 13 | 9–17 | 10 |

| Critical access hospital | 26 | 21–32 | 26 |

| Urban influence code | |||

| Urban | 57 | 51–63 | 58 |

| Close to urban | 24 | 19–29 | 23 |

| Rural (large town) | 7 | 4–10 | 6 |

| Rural (small town) | 12 | 8–16 | 12 |

| US region | |||

| Northeast | 13 | 9–17 | 14 |

| South | 28 | 23–34 | 29 |

| Midwest | 41 | 35–47 | 38 |

| West | 18 | 13–23 | 19 |

| Uninsured patients >25%‡ | 34 | 29–39 | 18 |

| Crowded by CDC criteria§ | 46 | 40–52 | 45 |

| ED social worker available | 76 | 71–81 | NA |

NA, Not available.

Data are percentage with 95% confidence interval unless otherwise indicated. NEDI-USA includes all US EDs in operation. Critical access hospital, Medicare designation as being a “necessary provider” of health care services and location greater than 35 miles from nearest hospital; urban influence code, a county-based measure of urban-rural status from the US Department of Agriculture, 2003.

Trauma center data are from the Trauma Information Exchange Program (TIEP), American Trauma Society, 2009.

According to the ED director. National data are from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) 2004.10

Presence of at least 1 of the 3 following criteria, as reported by the ED director: average waiting time of 1 hour or greater, left without being seen rate of 3% or greater, or any annual time on ambulance diversion. National data are from NHAMCS 2004.10

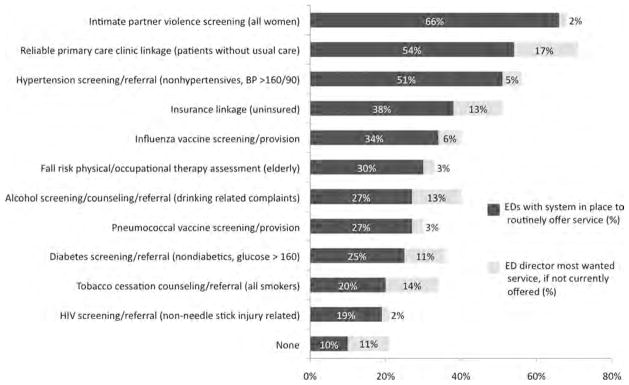

Figure 1 displays the current availability of ED preventive services. Intimate partner violence screening and referral was the most available among the 11 services (66% of EDs). In contrast, HIV screening was the least available, with only 19% of EDs routinely offering this service. Overall, 10% of the EDs did not offer any of the services. The median number of services offered for all EDs that responded was 4 (interquartile range 2 to 5).

Figure 1.

Availability and preference for ED preventive services according to ED directors.

Of all the services they did not already offer, ED directors most wanted to offer primary care linkage (17%) (Figure 1). In contrast, only 2% of ED directors most wanted HIV screening. Despite being offered in only 27% of EDs, smoking cessation counseling was the second most desired service among ED directors (14%).

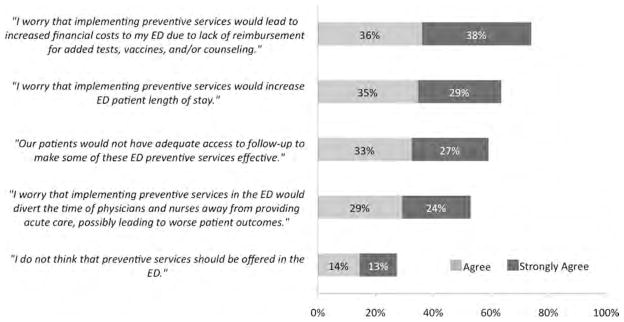

ED directors’ opinions of commonly perceived barriers to implementing preventive services in the ED are listed in Figure 2. Seventy-four percent of ED directors believed that implementing preventive services would lead to unreimbursed costs. Increased patient length of stay (64%), lack of follow-up (60%), and resource shifting away from acute care (53%) were also concerns of at least half of the ED directors. However, only 27% of the ED directors believed that preventive services should not be offered in the ED.

Figure 2.

ED director perceptions of commonly cited barriers to implementing ED preventive services. The light gray bars represent the proportion of ED directors who agree with listed statements. The dark gray bars represent the proportion of ED directors who strongly agree with listed statements.

LIMITATIONS

Although the results of this survey may be generalizable to US EDs as a whole, they may not be generalizable to high-volume urban EDs, which treat the highest proportion of patients at risk. In addition, the small sample size precluded subgroup analyses by different hospital characteristics.

The study is limited because the survey questions and terminology on availability of ED preventive services have not been validated in previous research. The research participants may have different interpretations of the definition of each service described in the survey, particularly of services that are generally part of routine ED operations (such as referral of incidentally discovered hypertension and hyperglycemia to follow-up care). Therefore, estimates of the availability of these types of services may be underestimated.

This survey reflects ED director preferences for preventive services and perceptions of barriers, and not actually their view on relative effectiveness, nor the degree to which each barrier inhibits implementation of the services. Because of space and time limitations, barriers were asked generically rather than for each service. Perceived barriers may vary across services.

Although our survey’s response rate was 80%, our estimates of the availability of some preventive services may be overestimated if a hospital that did not offer any preventive services declined to participate. Furthermore, the proportion of ED directors who do not think preventive services should be offered could also be biased if ED directors who are against ED preventive care declined to respond to the survey. However, even if all the nonresponders agreed that preventive care should not be offered in the ED, less than half of this national, random sample of ED directors would still be opposed to offering preventive care in the ED.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to provide a snapshot of the scope of preventive care offered in US EDs beyond high-volume, urban academic centers. Most (90%) EDs offered preventive services, although there was large variability in which services were offered. It is also the first to define ED director priorities for preventive services, as well as perceived barriers to implementation.

HIV screening was the least prevalent of the 11 selected services, available in only 19% of EDs surveyed, suggesting that the majority of US EDs were not offering routine HIV screening, as recommended by the 2006 CDC guidelines (all patients aged 13 to 64 years). We also found low interest in offering HIV screening among ED directors relative to other preventive health services. Thus, proponents of ED HIV screening, such as the CDC, will need to demonstrate that HIV screening is not just a worthy priority among the competing priorities for acute care but also a priority among the other preventive services that ED directors appear to prefer.

Intimate partner violence screening was the most prevalent of the 11 services, available in two thirds of EDs surveyed. Although high, this prevalence fell surprisingly short of national mandates and targets. Our study suggests that one third of the nation’s EDs may not be compliant with The Joint Commission mandate, which has required policies and procedures for intimate partner violence screening in hospitals and clinics since 1992.

Our survey is also the first to provide baseline estimates of the prevalence of 9 other services. Even if the absolute percentages were estimated with imprecision, the use of similar surveys over time could uncover important secular trends. Given that most of these services are not currently reimbursable, documentation of actual ED practice, rather than analysis of billing data, would also be useful to validate our study’s results.

Three quarters of ED directors are concerned that offering preventive services would lead to unreimbursed costs. Our findings imply that more widespread dissemination of ED preventive services will likely be contingent on improved reimbursement. ED directors were also concerned about the potential for increased patient length of stay and resource shifting away from acute care, both of which can lead to ED crowding, which is associated with worse patient outcomes. Finally, most ED directors cited inadequate access to follow-up as a reason why preventive services may not be effective in the ED. It can be argued that it is imprudent to screen patients for asymptomatic diseases if they do not have follow-up. Thus, it is not surprising that primary care linkage was the most desired service by ED directors.

Only 27% of ED directors thought that preventive services should not be offered in the ED, which implies that 3 of 4 ED directors are not philosophically opposed to offering preventive care in the ED. Thus, if the other concerns can be addressed, then ED directors may be more willing to implement preventive services.

In summary, most US EDs offer preventive services, but the individual availability and ED director preference for type of service vary considerably. Given these new data, champions of individual ED preventive services will have to justify their service not only among competing acute care priorities but also as a priority among the other preventive services that ED directors seem to prefer. Although most ED directors are not opposed to providing preventive care in the ED, increasing reliable linkage to primary care remains a top priority. Future research to determine the comparative effectiveness of ED preventive services should also analyze their effect on costs, patient flow, and safety, which are concerns for the majority of ED directors. This critical knowledge would guide policymakers and ED directors on implementing the most cost-effective services (acute or preventive) for improving the overall health of ED patients.

Editor’s Capsule Summary.

What is already known on this topic

A number of preventive health services have been advocated for the emergency department (ED) setting, but little is known about their routine availability.

What question this study addressed

Two hundred seventy-seven of 350 surveyed ED directors responded to questions about ongoing and desired preventive ED care services and barriers to their implementation.

What this study adds to our knowledge

Although most directors reported that their ED offered at least 1 preventive health service, services varied widely. Cost, increased ED length of stay, resource allocation, and inadequate access to follow-up are barriers to implementation.

How this is relevant to clinical practice

Efforts to increase preventive health services in EDs should focus on prioritization and barriers to implementation, especially resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Anna West and Ahmed Elrefaie for assistance with data collection, Janice Espinola, MPH, (Emergency Medicine Network) and Anthony Carlini, MS, (Trauma Information Exchange Program) for logistic support, Kristin Sainani, PhD, (Stanford) for critical review of the article, and Steven Bernstein, MD, (Yale University), Karin Rhodes, MD, MS (University of Pennsylvania), Michael Lyons, MD (University of Cincinnati), and Robert Rodriguez, MD (University of California San Francisco) for providing feedback on the survey instrument.

Funding and support: This research was supported by Agency for Health Care Research and Quality training grant T32HS00028 to the Center for Primary Care and Outcomes Research, Stanford University (Dr. Delgado), the Stanford-Kaiser Emergency Medicine Residency (Dr. Delgado), and National Institutes of Health grant 1K23HD051595-01A2 (Dr. Wang).

Footnotes

Author contributions: MKD, AAG, and CAC conceived and designed the study. MKD, NEW, and MCS supervised the conduct of data collection. MKD, CDA, and YSK collected and managed the data, including quality control. MKD and CDA analyzed the data. MKD drafted the article, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. MKD takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Presented at the Research Forum, California Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians, June 2009, Palm Springs, CA; and as a poster at the Research Forum, Scientific Assembly, American College of Emergency Physicians, October 2009, Boston, MA.

By Annals policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article that might create any potential conflict of interest. See the Manuscript Submission Agreement in this issue for examples of specific conflicts covered by this statement.

Reprints not available from the authors.

References

- 1.Rhodes KV, Gordon JA, Lowe RA Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Public Health and Education Task Force Preventive Services Work Group. Preventive care in the emergency department, part I: clinical preventive services—are they relevant to emergency medicine? Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1036–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irvin CB, Wyer PC, Gerson LW. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Public Health and Education Task Force Preventive Services Work Group. Preventive care in the emergency department, part II: clinical preventive services—an emergency medicine evidence-based review. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1042–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein SL, D’Onofrio G. Public health in the emergency department: Academic Emergency Medicine consensus conference executive summary. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1037–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelen GD. Public health initiatives in the emergency department: not so good for the public health? Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:194–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trautman DE, McCarthy ML, Miller N, et al. Intimate partner violence and emergency department screening: computerized screening versus usual care. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:526–534. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gates S, Fisher JD, Cooke MW, et al. Multifactorial assessment and targeted intervention for preventing falls and injuries among older people in community and emergency care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:130–133. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39412.525243.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charfen MA, Ipp E, Kaji AH, et al. Detection of undiagnosed diabetes and prediabetic states in high-risk emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:394–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acosta C, Dibble C, Giammona M, et al. A model for improving uninsured children’s access to health insurance via the emergency department. J Healthc Manag. 2009;54:105–115. discussion 115–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rimple D, Weiss SJ, Brett M, et al. An emergency department-based vaccination program: overcoming the barriers for adults at high risk for vaccine-preventable diseases. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:922–930. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burt CW, McCaig LF. Staffing, capacity, and ambulance diversion in emergency departments: United States, 2003–04. Adv Data. 2006;(376):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]