Abstract

Cellular events that occur across the seminiferous epithelium of the mammalian testis during spermatogenesis are tightly coordinated by biologically active peptides released from laminin chains. Laminin-γ3 domain IV (Lam γ3 DIV) is released at the apical ectoplasmic specialization (ES) during spermiation and mediates restructuring of the blood-testis barrier (BTB), which facilitates the transit of preleptotene spermatocytes. Here we determine the biologically active domain in Lam γ3 DIV, which we designate F5-peptide, and show that overexpression of this domain, or the use of a synthetic F5-peptide, in Sertoli cells with an established functional BTB reversibly perturbs BTB integrity in vitro and in rat testis in vivo. This effect is mediated via changes in protein distribution at the Sertoli and Sertoli-germ cell-cell interface and by phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase at Tyr407. The consequences are perturbed organization of actin filaments in Sertoli cells, disruption of the BTB and spermatid loss. The impairment of spermatogenesis suggests that this laminin peptide fragment may serve as a contraceptive in male rats.

Introduction

During the seminiferous epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis in the mammalian testis, such as in rats, multiple cellular events take place across the seminiferous epithelium, which include spermatogonial self-renewal via mitosis, meiosis, spermiogenesis, and spermiation, which are supported by Sertoli cells.1–9 Although these cellular events are tightly coordinated and regulated, the underlying regulatory mechanisms remain unknown. A recent report has shown that fragments of the laminin-β3 and -γ3 chains that are expressed by elongating/elongated spermatids and are components of the α6β1-integrin/laminin-α3β3γ3 adhesion protein complex at the apical ES,10,11 a testis-specific actin-based adherens junction (AJ)12,13), are likely generated at spermiation via the action of metalloprotease-214 as the result of apical ES disruption/degeneration at the adluminal edge of the tubule lumen act as the biologically active, autocrine peptides to induce BTB restructuring to facilitate the transit of preleptotene spermatocytes across the BTB.15 In short, these two cellular events, namely spermiation and BTB restructuring, that occur at the opposite ends of the seminiferous epithelium are coordinated by biologically active laminin fragments. This observation prompted us to hypothesize the presence of an apical ES-BTB functional axis15 which coordinates cellular events that occur at different cellular compartments in the seminiferous epithelium.12 Studies from other epithelia have also demonstrated that laminin fragments are biologically active, capable of altering cellular function, including cell movement and cell adhesion.13,16–19 In addition, the concept of an apical ES-BTB functional axis is supported by recent studies using the phthalate-induced Sertoli cell injury model.20–22 Moreover, we have recently shown that the activated FAK, p-FAK-Tyr407, appears to be a crucial signaling molecule that serves as a “molecular switch” in this axis via its restrictive spatiotemporal expression at the apical ES and the BTB sites to regulate this functional axis.23

We here report the identification of the biologically active domain residing in laminin-γ3 chain. Overexpression of this domain in Sertoli cells was found to perturb the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier function in vitro, and the use of a synthetic peptide based on this domain also perturbed BTB function reversibly both in vitro and in vivo. The peptide induced germ cell loss from the testis, thereby impairing spermatogenesis. We also identified a mechanism by which this peptide might exert its effects, which involves phosphorylation of FAK-Tyr407.

Results

Laminin fragments regulate Sertoli cell TJ function

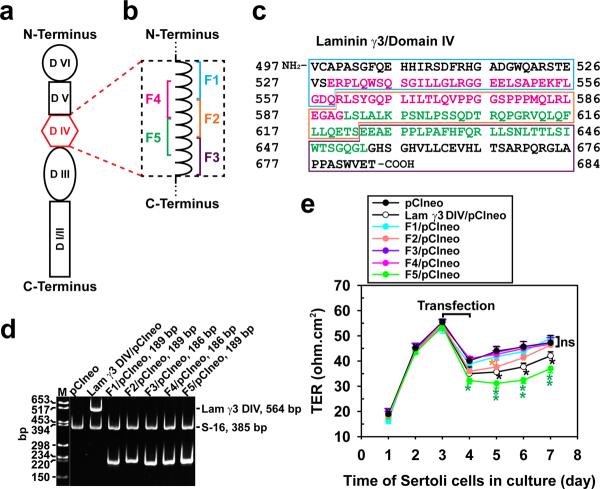

Studies in vitro were performed with a Sertoli cell culture system by using primary Sertoli cells with negligible Leydig and germ cell contamination as earlier described,24 which also formed a functional TJ-permeability barrier with ultrastructures of TJ, basal ES, gap junction and desmosome under electron microscopy25–27 that mimicked the BTB in vivo.2 This system is widely used by investigators in the field to study the BTB function and its regulation.28–30 In short, DNA constructs corresponding to the entire or portions of domain IV of laminin-γ3 chain were cloned into pCIneo vector (Fig. 1a–c), which were used to transfect Sertoli cells that had been cultured alone for 3 days (Fig. 1d) with an established functional TJ-permeability barrier (Fig. 1e) with a transfection efficiency of ~15–20% (see Supplementary Methods). Since Sertoli cells did not express laminin γ3 chain nor its fragment because laminin-γ3 is a spermatid protein at the apical ES in the rat testis10,15, expression of laminin γ3 DIV and the corresponding fragments F1–F5 in these Sertoli cell cultures (Fig. 1d) thus illustrate transient overexpression of these genes when cells were harvested 48 hr after transfection for RT-PCR using primers specific to these genes (Supplementary Table S1). It was noted that besides laminin-γ3 DIV, which was earlier shown to be biologically active to disrupt Sertoli cell TJ-barrier function,15 only F2 and F5 were capable of perturbing the Sertoli cell BTB function, but the F5 fragment was more potent in perturbing the TJ-barrier (Fig. 1e), illustrating the biologically active domains are residing in F5, perhaps also in part in F2 (see Fig. 1b, c). Attempts were made to further define the biologically active domain residing in the overlapping F2 and F5 fragments by preparing 3 additional cDNA constructs designated F6, F7 and F8 (see Fig. Supplementary Fig. S1); however, overexpression of these constructs in Sertoli cells showed that they were biologically inactive, incapable of perturbing the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier function or of reducing the expression of TJ- (e.g., occludin) and/or basal ES- (e.g., N-cadherin, β-catenin) at the Sertoli cell BTB (Supplementary Fig. S1a–e), indicating stretches of sequences in these two overlapping fragments are crucial to confer biological activity to perturb the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier.

Figure 1. Preparation of laminin-γ3 domain IV cDNA constructs to assess their biological activity.

(a) Schematic drawing illustrating different functional domains of laminin-γ3 chain. Laminin-γ3 domain IV (DIV, in red) was selected based on earlier studies that this domain is biologically active in regulating BTB dynamics,15 and it was further divided into 5 fragments of F1–F5 as shown in (b) to assess their effects on BTB function. (c) cDNA-deduced amino acid sequence of laminin-γ3 DIV (GenBank accession code XM_231139) is shown, illustrating the sequences of F1 (blue boxed area), F2 (orange boxed area), F3 (purple boxed area), F4 (pink colored text) and F5 (green colored text). (d) RT-PCR illustrating the expression of laminin-γ3 DIV and the five different fragments (see a) in Sertoli cells after transfection with corresponding vectors versus pCIneo alone for 3 days. Cells transfected with pCIneo alone served as a negative control since Sertoli cells per se did not express laminin-γ3 chains, which are exclusively expressed by elongating/elongated spermatids.10 S-16 served as an internal PCR control. Identity of the PCR product was confirmed by direct nucleotide sequencing at GeneWiz Inc (South Plainfield, NJ). M, DNA markers; bp, base-pair. (e) Changes in the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier function following transient expression of different fragments of laminin-γ3 DIV versus DIV (positive control) and pCIneo alone (negative control) on day 3 for 24-hr by quantifying TER across the Sertoli cell epithelium in bicameral units (n = 3). This experiment was repeated three times during different batches of Sertoli cells and yielded similar results. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01.

Laminin-γ3 fragments regulate protein expression at the BTB

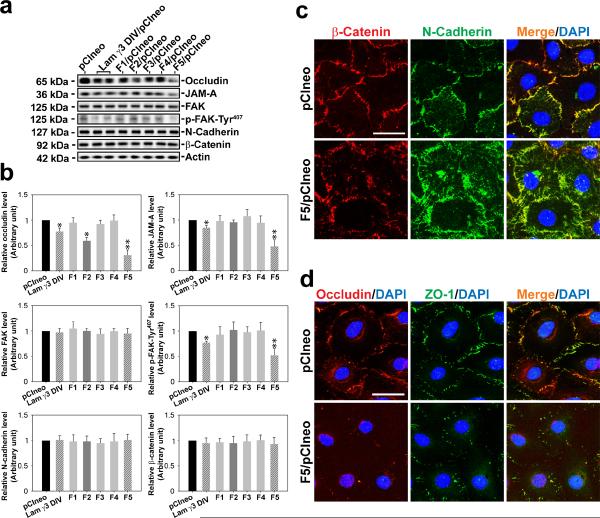

The biological effects of F2 and F5 fragments and the laminin-γ3 DIV versus control and other non-active fragments as noted in Fig. 1 were further assessed by their ability to modulate the steady-state levels of TJ- (e.g., occludin, JAM-A), TJ regulatory- (e.g., FAK, p-FAK-Tyr407), and basal ES- (e.g., N-cadherin, β-catenin) proteins at the Sertoli cell BTB on day 3 after transfection (i.e., day 6 after cell plating) (Fig. 2a, b). The steady-state protein levels of occludin, JAM-A and p-FAK-Tyr407, but not FAK, N-cadherin and β-catenin were found to be significantly reduced in Sertoli cell epithelium following overexpression of F5-peptide and laminin-γ3 DIV (Fig. 3A). The finding that the expression of p-FAK-Tyr407 was down-regulated by these fragments was significant since p-FAK-Tyr407 is a crucial BTB regulatory protein23. F2 fragment was also active, but its biological effect in disrupting Sertoli cell BTB protein expression was considerably lower versus F5 (Fig. 2a,b), consistent with data shown in Fig. 1e. Similarly, F6, F7 and F8 also had no apparent effects in perturbing the steady-state level of occludin in the Sertoli cell epithelium (Supplementary Fig. S1e).

Figure 2. Laminin-γ3 fragments affect protein expression and localization at the Sertoli cell BTB.

(a) On day 3, Sertoli cells with a functional BTB were transfected with different expression vectors for 24 hr and terminated 48 hr thereafter for immunoblotting, illustrating changes in the levels of integral membrane proteins (e.g., occludin, JAM-A, N-cadherin), adaptor protein (e.g., β-catenin) and regulatory proteins (e.g., FAK, p-FAK-Tyr407). (b) Bar graphs summarize results shown in (a). Each bar is a mean±SD of n = 5 experiments, and data were normalized against actin. The protein levels in cells transfected with pCIneo alone were arbitrarily set at 1, against which one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's test were performed. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (c) Overexpression of F5-peptide in Sertoli cells caused considerable re-distribution of basal ES-proteins at the BTB: β-catenin (red) and N-cadherin (green) at the Sertoli cell-cell interface, moving from cell surface into cell cytosol on day 3 after transfection. Overexpression of F5-peptide also changed localization and/or distribution of TJ proteins at the BTB: occludin (red) and ZO-1 (green) at the Sertoli cell-cell interface. Co-localized proteins appeared as “orange” in merged images. Nuclei were visualized by DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 10 μm in c and d, which applies to all images in both panels.

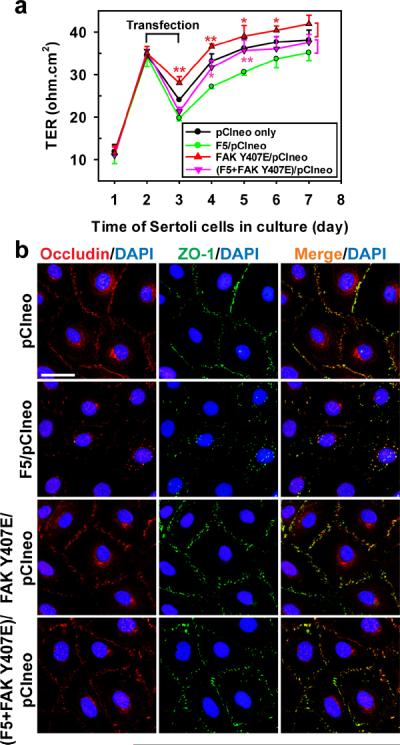

Figure 3. Laminin F5-peptide perturbs Sertoli cell TJ function via p-FAK-Tyr407.

(a) To examine the mechanism by which the F5-peptide perturbs the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier function as shown in Figs. 1 and 2, p-FAK-Tyr407, a molecular “switch” in the apical ES-BTB axis to regulate BTB restructuring and apical ES adhesion,23 was expressed either alone as a phosphomimetic mutant (FAK Y407E/pCIneo) or co-expressed with F5 [(F5+FAK Y407E)/pCIneo]. Co-expression of FAK phosphomimetic mutant FAK Y407E with F5-peptide in Sertoli cells blocked the F5-induced TJ-barrier disruption, which is likely mediated by the ability of p-FAK-Tyr407 to promote the distribution of occludin and ZO-1 at the Sertoli cell-cell interface shown in (b), thereby stabilizing the Sertoli TJ-barrier. Each data point is a mean±SD of n = 4 of a representative experiment, and this experiment was repeated 3 times which yielded similar results. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 Scale bar = 10 μm, which applies to all remaining micrographs.

Overexpression of F5 fragment affects protein distribution

Sertoli cells cultured alone for 3 days with an established TJ-permeability barrier were transfected with F5/pCIneo plasmid DNA versus pCIneo vector alone (control), 24 h thereafter, transfection mixture was removed and cells were cultured for an additional 2 days before being subjected to dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis using corresponding antibodies (see Supplementary Table S2). In control cells, basal ES-proteins N-cadherin (green) and β-catenin (red), and TJ proteins occludin (red) and ZO-1 (green) were co-localized mostly at the Sertoli cell-cell interface (Fig. 2c, d). In cells transfected with the F5 fragment, the localization of both N-cadherin and β-catenin became disorganized, as both proteins seemed to move from the cell surface into cell cytosol (Fig. 2c). However, we found a considerable loss of occludin and ZO-1 at the Sertoli cell-cell interface (Fig. 2d), consistent with a reduction in the steady-state level of occludin in these cells (see Fig. 2d, b). Overexpression of F5-peptide fragment also caused a loss in the co-localization of adhesion protein complexes N-cadherin/β-catenin and occludin-ZO-1 (Fig. 2c, d). These findings (Fig. 2) support results shown in Fig. 1e, illustrating that the disruption of the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier following F5-peptide overexpression in Sertoli cells is mediated by changes in protein distribution at the Sertoli cell-cell interface.

FAK Y407E blocks F5-peptide-induced TJ disruption

Phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr407 (p-FAK-Tyr407) is known to regulate BTB dynamics by increasing the tightness of the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier.23 As shown in Fig. 2a, overexpression of the F5-fragment in Sertoli cells that perturbed the TJ-barrier function (see Fig. 1e) down-regulated the expression of p-FAK-Tyr407. Overexpression of a phosphomimetic mutant FAK Y407E, however, promoted the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier, making it “tighter”, and its co-expression with F5 fragment (F5/pCIneo) was capable of blocking the F5 induced TJ-barrier disruption (Fig. 3a), illustrating p-FAK-Tyr407 is a crucial signaling molecule downstream of the biologically active laminin fragment in the apical ES-BTB axis. Studies by dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis also demonstrated that co-expression of FAK Y407E mutant prevented the F5 fragment mediated mis-distribution of occludin and ZO-1 at the Sertoli cell-cell interface (Fig. 3b), thereby illustrating p-FAK-Tyr407 is an important signaling partner of the laminin fragment in regulating the apical ES-BTB axis.

F5-peptide perturbs Sertoli cell TJ-function in vitro

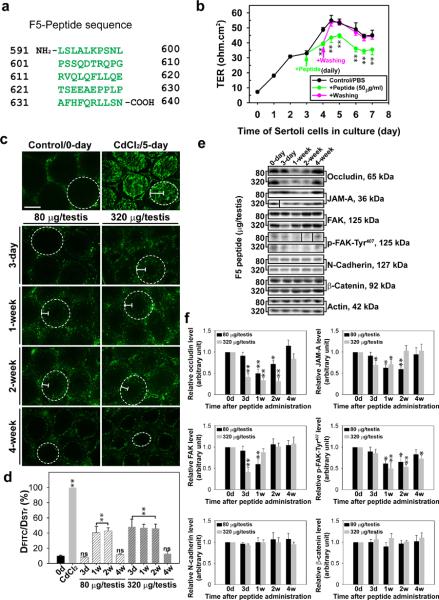

We next added a synthetic peptide corresponding to the first 50 amino acids of F5 fragment designated F5-peptide (Fig. 4a) to the bicameral units on day 3 when a functional TJ-barrier was established (Fig. 4b). We found that the presence of the synthetic F5-peptide perturbed the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier (Fig. 4b). This disruptive effect was reversible since its removal by washing Sertoli cells with F12/DMEM without the synthetic peptide allowed the disrupted TJ-barrier to be `resealed' (Fig. 4b). However, the 22-amino acid myotubularin-related protein 2 (MTMR2) had no apparent effects on the TJ-barrier, similar to PBS control (Fig. 4b), consistent with an earlier report.31

Figure 4. Laminin F5-peptide reversibly perturbs BTB function in vitro and in vivo.

(a) Amino acid residues (green) of the synthetic F5-peptide based on laminin-γ3 DIV. Numerals in “black” denote the sequence of laminin-γ3 chain (see Fig. 1a–c). (b) Effects of the synthetic F5-peptide on the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier. Peptide at 50 μg/ml (~10 μM) was added on day 3 (“green” arrow), which was either included in the daily replacement medium (“green”) (n = 3) or removed by washing on day 4 (“pink” arrow) in medium without peptide (“pink”) versus PBS control. When F5-peptide was removed, the disrupted TJ-barrier was “resealed”, illustrating the disruptive effect was reversible. Each data point is a mean±SD of n = 3 of a representative experiment, and this experiment was repeated 3 times which yielded similar results. **, P < 0.01. (c) BTB integrity assay was performed to assess the ability of an intact BTB to block the movement of FITC-inulin across the BTB from the basal compartment near the basement membrane (annotated by “white” dotted line) to the adluminal compartment. Results of the BTB integrity assay are shown in normal testes (control) versus rats treated with CdCl2 and different peptide treatment groups: 80 μg per testis (or ~10 μM) and 320 μg per testis (~40 μM). Scale bar = 150 μm in c, which also applies to all remaining micrographs. (d) Histograms summarizing data based on findings shown in c by comparing the distance of FITC-inulin diffused into the epithelium (DFITC) (annotated by the “white bracket”) vs. the radius of a seminiferous tubule (DSTr) (average of the longest and shortest axes for sections of oval-shaped tubules) (n = 200 tubules from testes of 3 rats in each group). **, P < 0.01; ns, not significantly different. (e) Immunoblot analysis of different target proteins at the BTB in adult rat testes at different time points after peptide administration. (f) Histograms summarizing data shown in e with n = 3 rats for each time point. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01.

F5-peptide reversibly disrupts BTB integrity in vivo

To validate if the findings shown in Fig. 4a, b are physiologically relevant, we sought to examine effects of the synthetic F5-peptide on the BTB integrity in vivo by treating rats with increasing doses of synthetic F5-peptide via intratesticular injection. In control rat testes (Fig. 4c), administration of FITC-inulin (green fluorescence) to rats at the jugular vein was found to be excluded from entering the adluminal compartment of the epithelium, consistent with the presence of a functional BTB located near the basement membrane (Fig. 4c). However, when rats were treated with CdCl2, which perturbs BTB integrity,32–34 a FITC signal was readily detected in the entire seminiferous epithelium beyond the BTB, including tubule lumen by day 5 (Fig. 4c). However, in rats treated with F5-peptide at doses of 80 (low-dose, ~10 μM) or 320 (high-dose, ~40 μM) μg per testis, BTB integrity was compromised dose-dependently over the next 4 weeks (Fig. 4c), even though this damage was not as severe as the CdCl2-induced irreversible BTB disruption. More importantly, the disrupted BTB induced by the synthetic F5-peptide was `resealed' after 4 weeks in both the low- and high-dose groups (Fig. 4c). Findings shown in Fig. 4c were further analyzed semi-quantitatively by comparing the distance traveled by FITC-inulin beyond the BTB near the basement membrane (DFITC) versus the radius of the seminiferous tubule (DSTr) (Fig. 4d). These findings also confirm results shown in Fig. 1e, Fig. 2c, d and Fig. 4b. When lysates from these rat testes were used for immunoblot analysis to quantify changes in the steady-state levels of TJ-proteins (e.g., occludin, JAM-A), TJ-regulatory proteins (e.g., FAK and p-FAK-Tyr407) and basal ES proteins (e.g., N-cadherin, β-catenin), a dose-dependent down-regulation on the expression of the TJ- and TJ-regulatory proteins, but not the basal ES proteins, was noted (Fig. 4e, f). For instance, a transient down-regulation of p-FAK-Tyr407 was noted (Fig. 4e, f \), consistent with findings in vitro shown in Fig. 2a, b)

Synthetic F5-peptide impairs spermatogenesis in rats

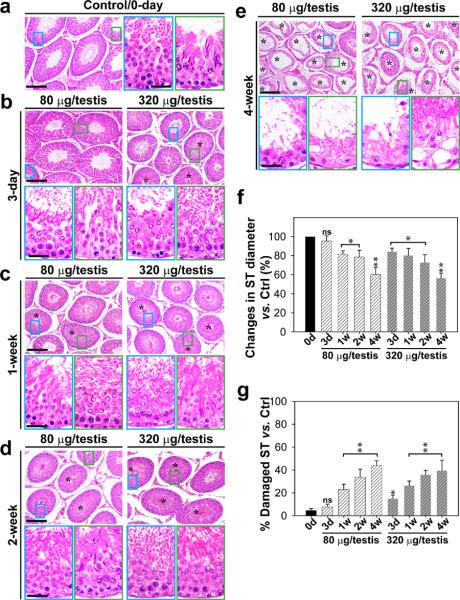

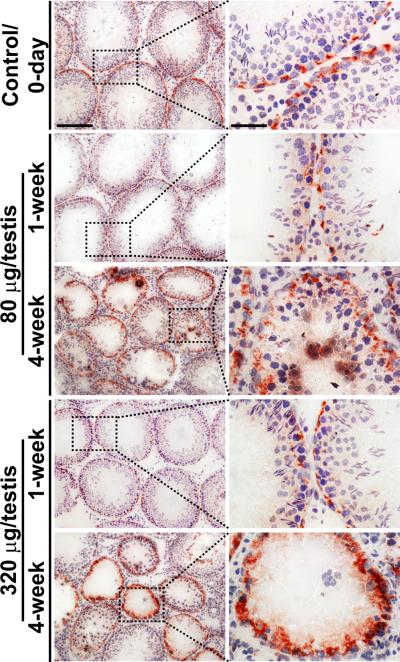

To test if local administration of peptide that perturbed the BTB in vivo would affect the status of spermatogenesis in the seminiferous epithelium, synthetic F5-peptide at doses of 80 (low-dose, 10 μM) or 320 (high-dose, 40 μM) μg per testis was administered via intratesticular injection, and histological analysis was performed following hematoxylin and eosin staining using cross-sections of paraffin-embedded testes (Fig. 5a–e). Although this treatment did not elicit statistically significant changes in testis weight over the 16-week experiment period since cell adhesion was affected in only ~40% of the tubules examined (Fig. 5f, g), possibly the result of limited access of the F5-peptide to all tubules via local administration, histological analysis of these testes revealed the synthetic F5-peptide caused germ cell depletion from the epithelium, mostly on elongated, elongating or round spermatids and some late spermatocytes in treatment versus control groups (Fig. 5a–g; Supplementary Fig. S2). This disruptive effect on germ cell adhesion was detectable 3 days after treatment in the high-dose group, and the progressive damage on the seminiferous epithelium in both groups was clearly visible (Fig. 5b–e) and quantifiable (Fig. 5f, g), illustrating the scope of damage in the epithelium following synthetic F5-peptide administration. For instance, the tubule diameter was reduced by ~40% (Fig. 5f, g) in ~40% of the tubules randomly scored, consistent with the observations shown in Fig. 5a–e. The disruptive effects of the F5-peptide on the status of spermatogenesis were reversible, since spermatogenesis gradually rebounded 16 weeks after treatment in the low-dose group (Supplementary Fig. S2). In a second control group, in which rats were treated with MTMR2 peptide at 50 μM (200 μg peptide/testis) (see Supplementary Methods), no alterations on the status of spermatogenesis were noted at 1-, 4- and 8-wk post treatment, consistent with an earlier report,31 illustrating the specificity of the F5-peptide in disrupting spermatogenesis.

Figure 5. Laminin F5-peptide impairs spermatogenesis and induces germ cell loss from the testis.

Peptide or vehicle control (0.89% NaCl, see a) was injected into each testis of a group of adult rats (~300–350 gm b.w.) with n = 3 rats per time point in each treatment group versus controls Rats were terminated at specific time points at 3-day and 1-, 2- or 4-wk thereafter. (b–e) Representative photographs of paraffin sections of testes stained with hematoxylin and eosin from rats treated with the synthetic F5-peptide at either 80 or 320 μg/testis. Vehicle control is shown in a. Morphometric changes [e.g., shrinkiage of tubule, and % of damaged seminiferous tubules (ST) manifested by germ cell exfoliation – annotated by asterisks in tubules] of the tubules (n = 200 tubules from 3 rat testes) are summarized in the bar graphs shown in f and g. Bar = 150 μm in a, and the micrographs on the left panels in b–e, which applies to the micrographs on the right panels b–e. Bar = 50 μm in micrograph encircled in “blue” which applies to all micrographs encirculed in and “green” in a–e. The “blue” and “green” encircled micrographs are magnified images of the corresponding boxed areas of the lower magnification. ns, not significantly different by ANOVA; *, P < 0.05; and **, P < 0.01 when compared to normal control rats at time 0.

F5-peptide affects protein localization in the testis

Findings shown in Figs. 3–5 thus illustrate that the synthetic F5-peptide is capable of inducing BTB disruption and germ cell loss in vivo after its intratesticular administration. We next used immunohistochemistry to assess any changes on the localization of TJ-proteins, such as occludin, at the BTB in the seminiferous epithelium (Fig. 6). Occludin was selected as a BTB marker protein because this integral membrane protein is abundantly found in the rat testis but its expression is restricted to the BTB.9 Furthermore, its KO in mice (occludin−/−) led to infertility by 36–60 week of age in which tubules were devoid of all spermatocytes and spermatids35,36 (but rats remained fertile by 6-35 to 10-36 week of age when other TJ-proteins, such as claudin-3, claudin 3, and JAM-A, apparently could supersede and transiently maintain the BTB integrity). In normal (control) rat testes, occludin was detected near the basal compartment of the epithelium, localized close to the basement membrane, consistent with its localization at the BTB in seminiferous tubules (Fig. 6). However, by 1-week in both the low-and high-dose F5-peptide treated groups, the expression of occludin was down-regulated (Fig. 6), consistent with immunoblotting data shown in Fig. 4e when the BTB was transiently disrupted at this time (Fig. 4c, d). However, by 4-week in both F5-peptide treated groups, the expression of occludin had rebounded, consistent with immunoblotting data shown in Fig. 4e, it was still found near the basement membrane, but it “diffusely” localized surrounding the base of the tubule (Fig. 6). In some seminiferous tubules in rats from the low- and more tubules in the high-dose groups by 4-week, occludin was found to be very intensely localized at the BTB in tubules that were completely devoid of germ cells (Fig. 6), analogous to a Sertoli cell-only syndrome.

Figure 6. Laminin F5-peptide perturbs occludin disruption at the BTB.

Normal rat testis (control, at time 0-day), displaying normal distribution of occludin at the BTB. versus rats received either 80 μg (~10 μM) or 320 μg (~40 μM) F5-peptide per testis by 1- and 4-week with noticeable germ cell loss in the tubules. Micrographs on the right panel are the corresponding magnified images of the boxed area shown on the left panel. Bar = 150 μm in the first micrograph on the left panel and scale bar = 50 μm in the first micrograph on the right panel, which apply to remaining micrographs in the same panel.

For basal ES proteins N-cadherin and β-catenin at the BTB,12,37 both proteins were found to co-localize at the BTB in control rat testes, forming a “belt-like” ultrastructure surrounding the base of the entire seminiferous tubule (Fig. Supplementary S3A–E). However, in testes obtained from rats by 4-week in either the low- or the high-dose synthetic F5-peptide treated group, while these two basal ES proteins remained co-localized at the BTB even when tubules were shrunk by ~40% and the BTB was disrupted (see also Figs. 4 and 5), both N-cadherin and β-catenin were found to be mis-localized, analogous to occludin shown in Fig. 6 and also data shown in Fig. 2c, d regarding their mis-localization, since these proteins no longer confined to the BTB in the seminiferous epithelium, instead, they were mis-localized, associated with apical junctions, and abnormally distributed (Supplementary Fig. S3).

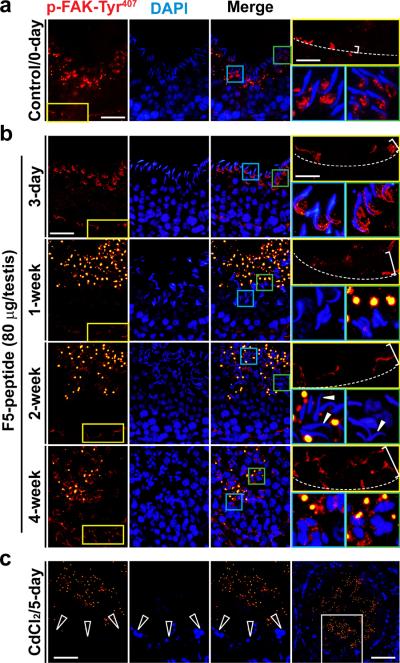

F5-peptide exerts its effects via p-FAK-Tyr407

A recent report has shown that p-FAK-Tyr407 promotes adhesion at the apical ES and the BTB via its restrictive spatiotemporal expression during the epithelial cycle.23 During the F5-peptide induced BTB disruption, a mis-localization of p-FAK-Tyr407 and its down-regulation at the BTB were detected, in which p-FAK-Tyr407 no longer tightly associated with the BTB, instead it was diffusing away from the site of the BTB in the seminiferous epithelium and its expression was down-regulated in some tubules (Fig. 7a, b). Interestingly, the expression of p-FAK-Tyr407 was almost abolished at the BTB in CdCl2-treated rats when the BTB was badly damaged (Fig.7c; Fig. 4c). Prominent changes in the localization of p-FAK-Tyr407 at the apical ES was initially detected by 3-day in the F5-peptide treated rats where p-FAK-Tyr407 no longer restricted to the concave side of the elongating spermatid heads, instead, p-FAK-Tyr407 was found to engulf both the concave and convex sides of the spermatid heads (Fig. 7). By 1- and 2-week, p-FAK-Tyr407 staining at the apical ES considerably diminished, almost non-detectable in most elongating spermatids and many of these spermatids lost their polarity with their heads pointing randomly to all directions instead of toward the basement membrane (see “white” arrowheads in Fig. 7) as seen in control rats. By 4-week, virtually no elongating/elongated spermatids were found in the affected tubules; instead, p-FAK-Tyr407 was found in vesicular structures (Fig. 7), which appeared to be cytoplasmic droplets as reported.23 These findings thus illustrate that the F5-peptide mediated its effects by down-regulating and/or redistributing p-FAK-Tyr407 in the seminiferous epithelium along the apical ES-BTB axis, which in turn, perturbed cell adhesion at the apical ES and the BTB, leading to germ cell loss (Fig. 5a, b, Supplementary Fig. S2) and BTB disruption (Fig. 4).

Figure 7. Laminin F5-peptide disrupts BTB and spermatid adhesion via p-FAK-Tyr407.

Testes received vehicle (control) at time 0 (a) versus synthetic F5-peptide at 80 μg/testis (~10 μM), and terminated at 3-day, and 1-, 2- and 4-week (b), and positive control where rats were treated with CdCl2 (5 mg/kg b.w., i.p., for 5 days) (c). In control testes, p-FAK-Tyr407 was localized near the basement membrane consistent with its localization at the BTB [see “yellow” boxed area in the micrograph on the left, which was magnified in the right panel (top) in each row with the relative BTB location annotated by the “broken white-line”]; p-FAK-Tyr407 was also found in the adluminal compartment, restricted almost exclusively to the concave side of the spermatid head at the apical ES [see “blue” and “green” boxed areas in the micrograph on the third column, which were magnified in the right panel (bottom) in each row]. Following F5-peptide treatment, p-FAK-Tyr407 was down-regulated and mis-localized at the BTB, since it no longer restricted to the BTB, but diffused away (see “white” bracket on the top right panel of each column in treatment groups vs. control rats, which was widened over time in treatment groups). p-FAK-Tyr407 was also down-regulated and its localization at the apical ES also shifted from the concave to cover the convex side of the spermatid head by 3-day, and p-FAK-Tyr407 no longer associated with the apical ES in most elongated spermatids by 1- and 2-week, and by 4-week as elongated spermatids were not found in most tubules. In CdCl2-treated rat testes (c), p-FAK-Tyr407 was no longer detectable at the BTB (see “open” white arrowheads), which was the magnified image of the “white” boxed area of the testis in the right column in (c), and p-FAK-Tyr407 was also considerably diminished. p-FAK-Tyr407 appeared as vesicle-like structures near the tubule lumen in rats after treatment (and also in CdCl2-treated rats), representing cytoplasmic droplets from p-FAK-Tyr407-positive materials engulfed by Sertoli cells.23 Scale bar = 50 μm in (a–c), which applies to all micrographs in the first three columns in (a–c), ; scale bar in the “yellow” boxed micrograph = 20 μm, which applies to all “blue” and “green” boxed micrographs in (a, b); scale bar in the last micrograph in (c) = 80 μm.

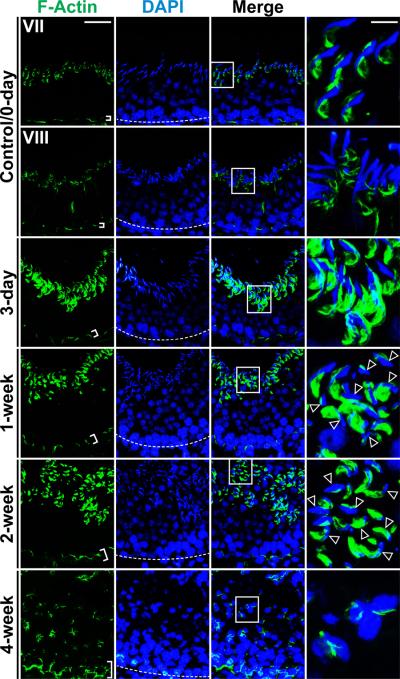

F5-peptide perturbs cell adhesion via F-actin organization

It was recently shown that p-FAK-Tyr407 mediated its effects via Arp-3 of the Arp-2/3-N-WASP complex, modulating branched actin polymerization, causing F-actin reorganization in Sertoli cells, thereby regulating cell adhesion at the BTB in the rat testis.23 Since overexpression of the F5 fragment in Sertoli cell epithelium (Fig. 2a, b) or administration of F5-peptide into testis (Fig. 4e, f) also down-regulated and/or induced mis-localization of p-FAK-Tyr407 (Fig. 7), we next investigated changes in the distribution of actin filament bundles in the seminiferous epithelium by staining F-actin using phalloidin-FITC. While the total actin determined by immunoblotting in both treatment groups versus controls were similar (see Fig. 4e), significant changes in the distribution and/or localization of F-actin at the apical ES and the BTB in the seminiferous epithelium following F5-peptide treatment were detected (Fig. 8). Specifically, actin filaments (i.e., F-actin) no longer tightly packed at the BTB, but it was mis-localized, moving away from the Sertoli cell-cell interface at the BTB (Fig. 8), and because of the peptide-induce depletion of elongated/elongating spermatids from the epithelium, F-actin at the apical ES site was also mis-localized (Fig. 8). These changes in F-actin organization thus contribute to an alteration of occludin localization at the BTB (see Fig. 6), destabilizing cell adhesion at the Sertoli-Sertoli cell interface, leading to BTB disruption (Fig. 4c–e), and premature release of spermatids (Fig. 5a–e, , Supplementary Fig. S2) from the epithelium.

Figure 8. Laminin F5-peptide induces spermatid loss via changes in F-actin distribution.

Rat testes received synthetic F5-peptide at 80 μg/testis (~10 μM) at time 0, and terminated at 3-day, and 1-, 2- and 4-week versus control (normal rats). Frozen sections were used to visualize the distribution F-actin in the seminiferous epithelium. Relative location of the BTB was annotated by the “white” broken line in the panel stained for cell nuclei with DAPI. Actin filaments were most abundant at the BTB and the apical ES at the Sertoli-spermatid interface as shown in a stage VII and VIII tubule in control rats at time 0. By 3-day, 1-, 2- and 4-week after F5 peptide treatment, in tubules of stage ~VII–VIII, actin filaments were redistributed, progressively moved away from the BTB site (see the “white” brackets that illustrate the relatively “tightly” packed actin filaments, such as those found in controls, were “unbundled” and the “white” brackets were widened in treat rat testes). While F-actin was also restricted to the apical ES at these time-points, the actin filaments no longer tightly restricted to the Sertoli-spermatid interface at the apical ES as seen in control testes (see “magnified” images in the last column of the “boxed” areas in the third column) and the actin filaments no longer restricted to the elongated spermatids as shown in control testes, but were also found in early elongating spermatids (see “open” arrowheads). This mis-localization of F-actin network at the apical ES no longer supported spermatid adhesion, causing premature “spermiation”. Scale bar = 50 μm in the micrograph in the first column, which applies to all micrographs in the first three columns, scale bar = 20 μm in the micrograph in the fourth column, which applies to all micrographs in this column.

Discussion

Herein, we have identified the biologically active domain in laminin-γ3 DIV of the laminin-γ3 chain from laminin-333 residing at the apical ES, which is comprised of a stretch of 50-amino acid residues designated F5-peptide, and a synthetic F5-peptide was found to be capable of reversibly perturbing the BTB in vivo, leading to germ cell exfoliation from the seminiferous epithelium of adult rat testes. These effects were found to be mediated by perturbing the restrictive spatiotemporal expression and/or localization of p-FAK-Tyr407, which, in turn, affects the distribution of actin filament bundles (i.e., F-actin) at the apical and basal ES in the epithelium. These findings illustrate that a disruption of the apical ES-BTB-basement membrane functional axis can be a novel approach to disrupt spermatogenesis. Other studies in the field also support the concept that biologically active collagen fragments can be used to manipulate the TJ-permeability barrier function in blood-tissue barriers.13,38 For instance, while a 20kDa fragment derived from collagen XVIII, known as endostatin, was ineffective per se to modulate the TJ-permeability barrier of retinal microvascular endothelial cells (RMEC), it was found to induce a significant increase of occludin expression at the RMEC TJ-barrier.39 Furthermore, endostatin was capable of blocking the VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor)-mediated TJ-barrier disruption in RMEC by altering the phosphorylation status of occludin at the blood-retinal barrier39 via an activation of ERK1/ERK2 and p38 MAPK.40 In the testis, collagens, such as collagen α3(IV) chains are abundant at the basement membrane, which is a modified extracellular matrix.2,38 Additionally, other studies have also illustrated that a degradation of laminin 332 by plasmin41 was found to impair keratinocyte adhesion and the assembly of basement membrane at the dermal-epidermal junction. Also, a deletion of collagen XVIII (in Col18α1−/− mice) or an overexpression of its endostatin domain) was found to accelerate or delay cutaneous wound healing, respectively.42 Collectively, these data thus demonstrate unequivocally that collagen and/or laminin fragments, some of these are biologically active peptides, can be generated during in vivo cellular processing to modulate diversified cellular functions. In short, F5-peptide generated at the apical ES during spermiation via cleavage of the laminin-γ3 chain by MMP2 near the apical region of the Sertoli cell epithelium can exert its effects near the basal region of the epithelium to induce BTB restructuring, mediated by changes in the expression and/or localization of p-FAK-Tyr407, to be followed by F-actin distribution and/or localization. Even though the synthetic F5-peptide disrupts the BTB integrity in vivo, the possibility of developing anti-sperm antibodies in these rats is unlikely because virtually all the advanced germ cells, such as post-meiotic spermatids, were depleted from the epithelium at the time of BTB disruption, and the disrupted BTB was “resealed” when spermatogenesis re-initiated.

Since laminin chains at the apical ES are restricted to elongating/elongated spermatids, a question arises regarding the signaling mechanism(s) by which laminin fragment(s) perturbs cell adhesion at the apical and basal ES since these biologically fragments are found outside the Sertoli in the seminiferous epithelium in vivo. Thus, is this an “outside-in” signaling, analogous to biologically active collagen fragments that were found to induce integrin clustering, in other cell epithelia?38,43 Our earlier studies have shown that besides laminin-γ3 chain, laminin-β3 chain also possesses biological activity in its domain I.15 Thus, we prepared two cDNA constructs based on domain I and laminin-β3 chain that did or did not contain the signal peptide (SP) for their transient expression in Sertoli cells in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S4) and to test their effects on the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier function (Supplementary Fig. S5). Interestingly, both constructs were capable of perturbing the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier function by down-regulating occludin expression, illustrating these biologically active fragments were active by inducing either “outside-in” or “inside-out” signaling (Supplementary Fig. S5). However, more work is needed to define the detailed molecular mechanism by which laminin fragments, such as F5-fragment, exert their effects via the “outside-in” signaling, including the identification of the involved receptor(s) in Sertoli cells.

While overexpression of F5-peptide or its direct administration into the rat testis were both found to perturb cell adhesion at the Sertoli cell BTB, perturbing the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier function as well as spermatid adhesion at the apical ES, which was found to perturb spermatogenesis in vivo. However, the efficacy of over-expression was limited to ~20% (see Supplementary Methods) while the efficacy via local administration of F5-peptide in the testis was at ~40%. Thus, an improved delivery methodology remains to be developed, such as involving the use of protein transduction domain,44,45 genetic engineered F5-peptide into an FSH mutant,46 or nanoparticle-based F5-petide.47,48

In summary, we have identified the biologically active domain of laminin-γ3 domain IV, which is highly effective in perturbing the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier function both in vitro and in vivo, mediating its effects via p-FAK-Tyr407, affecting the localization and/or distribution of TJ integral membrane proteins (e.g., occludin) at the site via changes in the organization of F-actin at the Sertoli-Sertoli and Sertoli-spermatid adhesion sites. It was found that the administration of the F5-peptide in the testis that perturbs the apical ES-BTB-basement axis also leads to germ cell exfoliation and impairs spermatogenesis. Additional studies are now warranted to investigate if this peptide can be developed into a male contraceptive. Several other questions also remain to be addressed in future studies. For instance, do other epithelial cells, such as MDCK cells, that establish apical junctions respond to F5-peptide similarly as of Sertoli cells? When F5 peptide was overexpressed in Sertoli cells, do they remain in the cell, or confined in cell cytosol or in membranous compartments? If the peptide fragments are released at spermiation at the apical region of the Sertoli cell, they presume to exert their effects via receptors (such as integrins at the apical ES in Sertoli cells10) and/or signaling molecules (e.g., p-FAK-Tyr397 or -Tyr407) 23at the apical ES that generate a signaling cascade that leads to changes in basal junctions at the BTB. How does administering the peptide basally to Sertoli cells in vivo would have the effects since the receptors would presumably be concentrated above the BTB? We expect that some of these questions will be addressed in the near future.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (20-day-old pups; and adult males at ~275–300 gm b.w.) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Kingston, NY). The use of animals was approved by the Rockefeller University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) with Protocol Numbers 09016 and 12506.

Overexpression of laminin fragments or FAK mutant

Laminin fragments F1-F8 corresponding to different stretches of sequences of laminin γ3 domain IV chain (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S1) were cloned into pCIneo mammalian expression vector (Promega) at the sites between XhoI and SalI by using specific primers (Supplementary Table S1). The authenticity of these clones was confirmed by direct nucleotide sequencing at Genewiz Inc (South Plainfield, NJ). p-FAK phosphomimetic mutant FAKY407E was prepared using a full-length rat FAK clone prepared in our laboratory by site-directed mutagenesis as earlier described23 was also cloned into the MluI/XbaI site of the pCIneo vector. Prior to their use, plasmid DNA was purified using the HiSpeed Plasmid Midi Kit (Qiagen). On day 3, after a functional Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier was established, cells at 0.5 × 106 cells/cm2 in 12-well dishes (with 3-ml F12/DMEM per well) or at 1.2 × 106 cells/cm2 in bicameral units placed in 24-well dishes (with 0.5-ml F12/DMEM each in the apical and basal compartment) were transfected with either 1 or 0.5 μg plasmid DNA by using Effectene Transfection Reagent (Qiagen) at a ratio of 15 μl to 1 μg DNA. Transfection mixture was removed 24 h thereafter and replaced with fresh F12/DMEM. RNA and protein lysates were obtained from these cultures 2 and 3 days thereafter, respectively. The TJ-permeability barrier after transient expression of laminin-γ3 domain IV fragments versus pCIneo vector alone was also assessed by TER measurement across the Sertoli cell epithelium as earlier described.49

Treatment of rat testes with synthetic F5-peptide

Adult rats weighing ~250–275 gm b.w. (body weight) (n = ~5–6 rats per time point in both treatment and control groups) received a single dose of the synthetic peptide at either 80 μg (~10 μM) or 320 μg (~40 μM) per testis (testis weight at ~1.6 gm, assuming a volume of ~1.6-ml) via direct intratesticular injection using a 28-gauge needle in a final injection volume of ~200 μl (in 0.9% saline) as earlier described.31,50 These concentrations of synthetic F5-peptide were selected based on results of the in vitro study in which 50 μg/ml (~10 μM) was found to consistent and reversibly perturb the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier. In some experiments, the right testis received the synthetic F5-peptide and the left testis received vehicle alone (saline alone without synthetic peptide) to serve as negative controls. Rats were terminated on day 3, and 1-, 2- and 4-week thereafter. Rats were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and testes were removed. In selected experiments, testes were either fixed in Bouin's fixative to be used for paraffin embedding and sectioning for hematoxylin and eosin staining for histological analysis as described,27 or snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until used to obtain frozen-sections for immunohistochemistry or immunoblotting. In some experiments, rats at specified time points were subjected to an in vivo assay to assess the BTB integrity. In selected rats, they were treated with the 22-amino acid MTMR2 peptide at 200 μg/testis (~50 μM) and terminated at 1-, 4-, and 8-week for histological analysis (n = 3 rats per time point), and no alterations in the status of spermatogenesis were noted, consistent with an earlier report.31 Thus, these rats were not used for subsequent BTB integrity assay.

Other Materials and Methods pertinent to this report, such as primary Sertoli cell cultures, preparation of cDNA constructs to assess “inside-out” and “outside-in” signaling, BTB integrity assay, dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis, immunohistochemistry, F-actin staining, immunoblot analysis and statistical analysis can be found in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NICHD U54 HD029990, Project 5 to CYC; R01 HD056034 to CYC)

Footnotes

Author contributions: C.Y.C. designed research; L.S., P.P.Y.L., and C.Y.C. performed research; L.S., D.D.M., P.P.Y.L., B.S., and C.Y.C. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; L.S., D.D.M., P.P.Y.L., and C.Y.C. analyzed data; and C.Y.C. wrote, revised and edited the paper.

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.de Kretser DM, Kerr JB. The cytology of the testis. In: Knobil E, et al., editors. The Physiology of Reproduction. Vol. 1. Raven Press; New York: 1988. pp. 837–932. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. The blood-testis barrier and its implication in male contraception. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:16–64. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.002790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharpe RM. Regulation of spermatogenesis. In: Knobil E, Neill JD, editors. The Physiology of Reproduction. Raven Press; New York: 1994. pp. 1363–1434. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parvinen M. Regulation of the seminiferous epithelium. Endocr Rev. 1982;3:404–417. doi: 10.1210/edrv-3-4-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hess RA, de Franca LR. Spermatogenesis and cycle of the seminiferous epithelium. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;636:1–15. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09597-4_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carreau S, Hess RA. Oestrogens and spermatogenesis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365:1517–1535. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Donnell L, Nicholls PK, O'Bryan MK, McLachlan RI, Stanton PG. Spermiation: the process of sperm release. Spermatogenesis. 2011;1:14–35. doi: 10.4161/spmg.1.1.14525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mruk DD, Silvestrini B, Cheng CY. Anchoring junctions as drug targets: Role in contraceptive development. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:146–180. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. Cell junction dynamics in the testis: Sertoli-germ cell interactions and male contraceptive development. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:825–874. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00009.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan HHN, Cheng CY. Laminin α3 forms a complex with β3 and γ3 chains that serves as the ligand for α6β1-integrin at the apical ectoplasmic specialization in adult rat testes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17286–17303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salanova M, Stefanini M, De Curtis I, Palombi F. Integrin receptor α6β1 is localized at specific sites of cell-to-cell contact in rat seminiferous epithelium. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:79–87. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. A local autocrine axis in the testes that regulates spermatogenesis. Nature Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6:380–395. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan HHN, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Ectoplasmic specialization: a friend or a foe of spermatogenesis? BioEssays. 2007;29:36–48. doi: 10.1002/bies.20513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siu MKY, Cheng CY. Interactions of proteases, protease inhibitors, and the β1 integrin/laminin γ3 protein complex in the regulation of ectoplasmic specialization dynamics in the rat testis. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:945–964. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.023606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan HHN, Mruk DD, Wong EWP, Lee WM, Cheng CY. An autocrine axis in the testis that coordinates spermiation and blood-testis barrier restructuring during spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8950–8955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711264105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coopman PJ, et al. Influence of basement membrane molecules on directional migration of human breast cell lines in vitro. J Cell Sci. 1991;98:395–401. doi: 10.1242/jcs.98.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porter BE, Sanes JR. Gated migration: neurons migrate on but not onto substrates containing S-laminin. Dev Biol. 1995;167:609–616. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamashita H, et al. The role of a recombinant fragment of laminin-332 in integrin α3β1-dependent cell binding, spreading and migration. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5110–5121. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santos-Valle P, et al. The heterotrimeric laminin coiled-coil domain exerts anti-adhesive effects and induces a pro-invasive phenotype. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazaud-Guittot S. Dissecting the phthalate-induced Sertoli cell injury: the fragile balance of proteases and their inhibitors. Biol Reprod. 2011;85:1091–1093. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.095976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao PL, Lin YC, Richburg JH. TNFα-mediated disruption of spermatogenesis in response to Sertoli cell injury in rodents is partially regulated by MMP2. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:581–589. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao PL, Lin YC, Richburg JH. Mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-induced disruption of junctional complexes in the seminiferous epithelium of the rodent testis is mediated by MMP2. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:516–527. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.080374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lie PPY, et al. Focal adhesion kinase-Tyr407 and -Tyr397 exhibit antagonistic effects on blood-testis barrier dynamics in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12562–12567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202316109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee NPY, Mruk DD, Conway AM, Cheng CY. Zyxin, axin, and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein are adaptors that link the cadherin/catenin protein complex to the cytoskeleton at adherens junctions in the seminiferous epithelium of the rat testis. J Androl. 2004;25:200–215. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb02780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siu MKY, Wong CH, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Sertoli-germ cell anchoring junction dynamics in the testis are regulated by an interplay of lipid and protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25029–25047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501049200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lie PPY, Cheng CY, Mruk DD. Crosstalk between desmoglein-2/desmocollin-2/Src kinase and coxsackie and adenovirus receptor/ZO-1 protein complexes, regulates blood-testis barrier dynamics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:975–986. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li MWM, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Disruption of the blood-testis barrier integrity by bisphenol A in vitro: Is this a suitable model for studying blood-testis barrier dynamics? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:2302–2314. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janecki A, Jakubowiak A, Steinberger A. Effect of cadmium chloride on transepithelial electrical resistance of Sertoli cell monolayers in two-compartment cultures - a new model for toxicological investigations of the “blood-testis” barrier in vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992;112:51–57. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(92)90278-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okanlawon A, Dym M. Effect of chloroquine on the formation of tight junctions in cultured immature rat Sertoli cells. J Androl. 1996;17:249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grima J, Pineau C, Bardin CW, Cheng CY. Rat Sertoli cell clusterin, α2-macroglobulin, and testins: biosynthesis and differential regulation by germ cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1992;89:127–140. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(92)90219-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung NPY, Mruk DD, Mo MY, Lee WM, Cheng CY. A 22-amino acid synthetic peptide corresponding to the second extracellular loop of rat occludin perturbs the blood-testis barrier and disrupts spermatogenesis reversibly in vivo. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:1340–1351. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.5.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong CH, Mruk DD, Lui WY, Cheng CY. Regulation of blood-testis barrier dynamics: an in vivo study. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:783–798. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Setchell BP, Waites GMH. Changes in the permeability of the testicular capillaries and of the “blood-testis barrier” after injection of cadmium chloride in the rat. J Endocrinol. 1970;47:81–86. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0470081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hew KW, Heath GL, Jiwa AH, Welsh MJ. Cadmium in vivo causes disruption of tight junction-associated microfilaments in rat Sertoli cells. Biol Reprod. 1993;49:840–849. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod49.4.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saitou M, et al. Complex phenotype of mice lacking occludin, a component of tight junction strands. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:4131–4142. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takehashi M, et al. Production of knockout mice by gene targeting in multipotent germline stem cells. Dev Biol. 2007;312:344–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee NPY, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Is the cadherin/catenin complex a functional unit of cell-cell-actin-based adherens junctions (AJ) in the rat testis? Biol Reprod. 2003;68:489–508. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.005793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siu MKY, Cheng CY. Dynamic cross-talk between cells and the extracellular matrix in the testis. BioEssays. 2004;26:978–992. doi: 10.1002/bies.20099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brankin B, Campbell M, Canning P, Gardiner TA, Stitt AW. Endostatin modulates VEGF-mediated barrier dysfunction in the retinal microvascular endothelium. Exp Eye Res. 2005;81:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell M, et al. Involvement of MAPKs in enostatin-mediated regulation of blood-retinal barrier function. Curr Eye Res. 2006;31:1033–1045. doi: 10.1080/02713680601013025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogura Y, Matsunaga Y, Nishiyama T, Amano S. Plasmin induces degradation and dysfunction of laminin 332 (laminin 5) and impaired assembly of basement membrane at the dermal-epidermal junction. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:49–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seppinen L, et al. Lack of collagen XVIII accelerates cutaneous wound healing, while overexpression of its endostatin domain leads to delayed healing. Matrix Biol. 2008;27:535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rabie T, Strehl A, Ludwig A, Nieswandt B. Evidence for a role of ADAM17 (TACE) in the regulation of platelet glycoprotein Vi. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14462–14468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van den Berg A, Dowdy SF. Protein transduction domain delivery of therapeutic macromolecules. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011;22:888–893. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mariyanna L, et al. Excision of HIV-1 proviral DNA by recombinant cell permeable trerecombinase. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mruk DD, Wong CH, Silvestrini B, Cheng CY. A male contraceptive targeting germ cell adhesion. Nature Med. 2006;12:1323–1328. doi: 10.1038/nm1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee JH, Vigit MV, Mazumdar D, Lu Y. Molecular diagnostic and drug delivery agents based on aptamer-nanomaterial conjugatese. Adv Drug Del Rev. 2010;62:592–605. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuen AK, Hutton GAM, A.F., Maschmeyer T. The interplay of catechol ligands with nanoparticulate iron oxides. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:2545–2559. doi: 10.1039/c2dt11864e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su L, Mruk DD, Lui WY, Lee WM, Cheng CY. P-glycoprotein regulates blood-testis barrier dynamics via its effects on the occludin/zonula occludens 1 (ZO-1) protein complex mediated by focal adhesion kinase (FAK) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:19623–19628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111414108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Russell LD, Saxena NK, Weber JE. Intratesticular injection as a method to assess the potential toxicity of various agents to study mechanisms of normal spermatogenesis. Gamete Res. 1987;17:43–56. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1120170106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.