Abstract

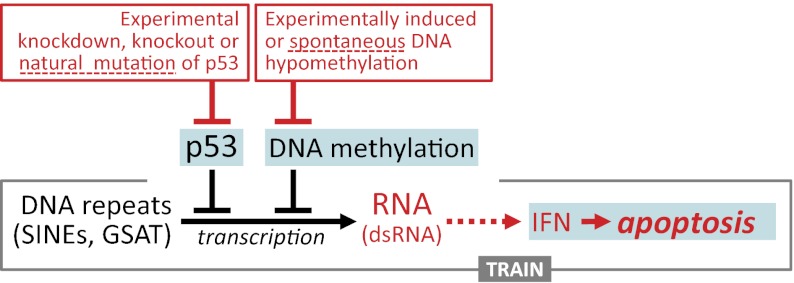

Large parts of mammalian genomes are transcriptionally inactive and enriched with various classes of interspersed and tandem repeats. Here we show that the tumor suppressor protein p53 cooperates with DNA methylation to maintain silencing of a large portion of the mouse genome. Massive transcription of major classes of short, interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) B1 and B2, both strands of near-centromeric satellite DNAs consisting of tandem repeats, and multiple species of noncoding RNAs was observed in p53-deficient but not in p53 wild-type mouse fibroblasts treated with the DNA demethylating agent 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine. The abundance of these transcripts exceeded the level of β-actin mRNA by more than 150-fold. Accumulation of these transcripts, which are capable of forming double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), was accompanied by a strong, endogenous, apoptosis-inducing type I IFN response. This phenomenon, which we named “TRAIN” (for “transcription of repeats activates interferon”), was observed in spontaneous tumors in two models of cancer-prone mice, presumably reflecting naturally occurring DNA hypomethylation and p53 inactivation in cancer. These observations suggest that p53 and IFN cooperate to prevent accumulation of cells with activated repeats and provide a plausible explanation for the deregulation of IFN function frequently seen in tumors. Overall, this work reveals roles for p53 and IFN that are key for genetic stability and therefore relevant to both tumorigenesis and the evolution of species.

Keywords: interferon alpha-beta receptor, RNA sequencing, epigenetic repression, microarray hybridization

Mammalian genomes contain an abundance of noncoding DNA sequences as well as multiple classes of interspersed repetitive elements such as DNA transposons and retrotransposons. They vary in length and copy number, are evolutionarily younger than structural genes, and are generally considered “genomic junk” with uncertain physiological roles (1). Among these, the most abundant are short, interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) that originate from reverse-transcription products of certain RNA polymerase III-driven transcripts (e.g., 7SL RNA and tRNAs) (2) and have been shown to retain some ability to retrotranspose (3, 4). In addition, the mammalian genome also contains tandemly organized repeats known as “satellite DNAs” (5). These highly reiterated sequences are the main component of the centromeric and pericentromeric heterochromatin and are considered important structural elements of the chromosome (6). Together, these classes of noncoding DNA sequence elements occupy more than 50% of the human and mouse genomes (1).

Analysis of the phylogeny of SINEs suggests that they accumulated through multiple “explosions,” or bursts of amplification, which started about 65 million years ago and were intermitted by periods of dormancy (7, 8). The explosive nature of multiplication of SINEs and the fact that they all are located predominantly in intergenic areas, pseudogenes, and noncoding regions of genes suggest that their bursts of amplification were genetic catastrophes associated with massive loss of those genomes in which SINEs inserted within essential genes (2, 9, 10) and presumably contributed to the diversity of mammalian species. In fact, integration of new SINE copies into coding or regulatory sequences has the potential to disturb gene expression (11).

Therefore, it is logical to assume that maintenance of the genetic stability of mammalian cells and organisms depends on their ability to prevent the expression and amplification of SINEs. In fact, SINEs normally are transcribed not as distinct autonomous elements but rather as integral parts of noncoding regions of larger protein-coding transcripts (2). The great majority of SINEs are located in heavily methylated regions of DNA and are believed to be epigenetically silenced through the mechanism of DNA methylation (12, 13).

However, under certain circumstances both retroelements and some classes of satellite DNA can be transcribed. The events triggering such activation are not well understood but have been shown to include a variety of stresses such as heat shock (14, 15), viral infections (16), various DNA-damaging treatments (17), and inhibition of translation (14). In addition, transcription of both retroelements and satellite DNA was observed in tumors in a variety of models of mouse and human origin (18). Both the mechanisms underlying the transcriptional activation of normally silent noncoding elements and repeats in stressed and transformed cells and the physiological consequences of this activation remain poorly understood.

Here we show that the tumor suppressor p53, known as a positive and negative regulator of transcription, plays a major role, along with DNA methylation, in epigenetic silencing of major classes of retroelements and satellite DNA in mice. In the absence of functional p53, DNA hypomethylation results in a massive transcription of several classes of normally silent repeats and in the accumulation of new, largely double-stranded RNA species, which are followed by a cytotoxic type I IFN response. These observations suggest that p53 and IFN cooperate through regulation of transcription and cell death, respectively, to prevent the accumulation of cells with “unleashed” repeats. This phenomenon, which we have named “TRAIN” (for “transcription of repeats activates interferon”), provides a plausible explanation for a number of well-known but never previously connected properties of tumor cells, including transcription of repeats and frequent deregulation of IFN function.

Results

DNA Demethylation Can Be Lethal for p53-Null, But Not for p53-WT Cells.

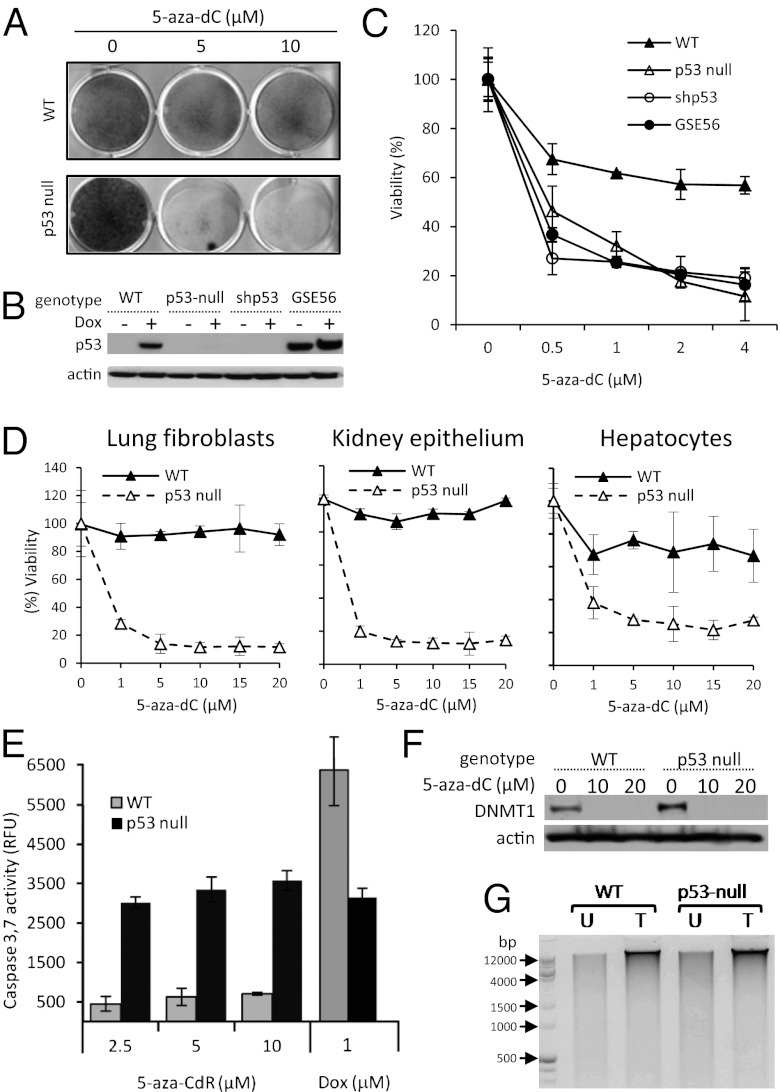

In 2004, Nieto et al. (19) reported that in vitro treatment with the DNA-demethylating agent 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5-aza-dC) induced apoptosis in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) lacking p53 but not in those with WT p53. We confirmed and extended this observation (Fig. 1 A and C) by showing that MEFs, irrespective of the sex of the embryo (Fig. S1), become highly sensitive to 5-aza-dC following either shRNA-mediated knockdown of p53 or ectopic expression of a dominant-negative p53 mutant, GSE56 (20) (Fig. 1 B and C). The latter result indicates that sensitization to 5-aza-dC does not require the physical absence of p53 but only its functional inactivation. High sensitivity to a DNA-demethylating agent is not limited to p53-deficient fibroblasts and also is the property of fibroblasts and epithelial cells isolated from different tissues of adult mice (Fig. 1D). This phenomenon was observed only in proliferating p53-null cells (Fig. S2) and required at least 72 h of 5-aza-dC treatment, reflecting the time needed for the compound to exert its DNA-demethylating activity fully (19). Death of 5-aza-dC–treated p53-null cells was associated with activation of caspases 3 and 7, indicating involvement of apoptosis (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Primary cells deficient in functional p53 are hypersensitive to 5-aza-dC treatment. (A) p53-WT and p53-null MEFs were treated with 0, 5, or 10 µM 5-aza-dC for 120 h. Viable cells were visualized by methylene blue staining. (B) Western blot detection of p53 and β-actin (loading control) proteins in p53-WT MEFs (lanes 1 and 2), p53-null MEFs (lanes 3 and 4), and p53-WT MEFs expressing shRNA against p53 (shp53, lanes 5 and 6) or the p53-inactivating genetic suppressor element-56 (GSE56, lanes 7 and 8) left untreated (−) or treated (+) with 500 nM doxorubicin (Dox) for 16 h. (C) Cytotoxicity of 5-aza-dC in cells described in B. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of 5-aza-dC for 5 d. Viability was determined by methylene blue staining and extraction, followed by spectrophotometric quantification. Percent viability is shown relative to control cells treated with 0.1% DMSO. In all relevant figures, error bars show SDs for assays performed in triplicate. (D) Cytotoxicity of 5-aza-dC (5 d in vitro treatment) in primary cells from different tissues of adult p53-WT and p53-null mice was determined as in C. (E) Caspase-3,7 activity (cleavage of the fluorescent substrate AC-Devd-AMC) in p53-WT and p53-null MEFs treated with the indicated concentrations of 5-aza-dC for 48 h or 1 µM doxorubicin (Dox) for 16 h. (F) Western blot analysis of DNMTI and β-actin (loading control) protein levels in p53-WT and p53-null MEFs treated with the indicated concentrations of 5-aza-dC for 48 h. (G) The overall extent of genomic DNA methylation in p53-WT and p53-null MEFs left untreated (U) or treated (T) with 10 µM 5-aza-dC for 48 h was determined by digestion of DNA with the methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme McrBC, which cuts only its sites that are methylated.

A potential trivial explanation for the observed phenomenon would be that 5-aza-dC is inefficient as a demethylating agent in cells with functional p53 because of their ability to undergo growth arrest following DNA damage [known to be caused by 5-aza-dC (19)]. This possibility was ruled out by our findings of (i) complete depletion of free DNA methyltransferase I (DNMT1) protein in both p53-WT and p53-null cells after 5-aza-dC treatment (Fig. 1F), and (ii) similar degrees of DNA demethylation in the genomic DNA of p53-WT and p53-null cells following 5-aza-dC treatment as evidenced by similar patterns of DNA digestion by the methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme McrBC (Fig. 1G).

In summary, sensitivity to 5-aza-dC–induced apoptosis is a common property of p53-deficient mouse cells regardless of their tissue of origin or the mechanism of p53 inactivation (knockout, knockdown, or functional inactivation). The selective toxicity to p53-null cells differentiates 5-aza-dC from other DNA damaging agents, which generally are more toxic to p53-WT cells (21). Indeed, doxorubicin treatment induced higher levels of caspases 3 and 7 in p53-WT than in p53-null MEFs (Fig. 1E). Therefore, the selective toxicity of 5-aza-dC to p53-null cells is likely associated with its demethylating activity rather than with its DNA damaging activity.

Different Subsets of Genes Are Activated by 5-aza-dC in p53-Null and p53-WT MEFs.

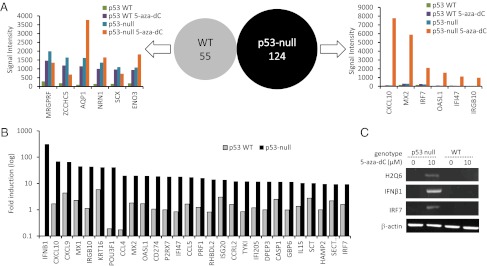

It is believed that many potentially functional genetic elements in mammalian genomes are transcriptionally repressed by methylation of CpG dinucleotides in the vicinity of their promoters (22). Derepression of some genes regulated in this way (e.g., tumor suppressors p16, PTEN, and Arf, among others) can have a detrimental effect on cell growth or even be cytotoxic (23). Therefore, we hypothesized that the hypersensitivity of p53-null cells to 5-aza-dC might be caused by the activation of transcription of some “killer” genes that normally are repressed by the combined action of a DNA methylation-mediated mechanism and the transrepressor function of p53. To identify these putative killer genes, we compared sets of transcripts activated by 5-aza-dC treatment in p53-WT and p53-null MEFs shortly before the onset of the toxic effect of the drug (i.e., at 48 h) using microarray (Illumina MouseWG-6 v2.0) hybridization-based global gene-expression profiling. The results of this comparison are summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Illumina microarray-based analysis of gene expression in p53-WT and p53-null MEFs left untreated or treated with 10 µM 5-aza-dC for 48 h. (A) (Center) Venn diagram showing no overlap between the 55 and 124 genes up-regulated (≥fivefold) by 5-aza-dC in p53-WT (Left) and p53-null (Right) cells. Bar graphs show mRNA expression levels (signal intensity on Illumina microarray) of genes identified as 5-aza-dC–induced in p53-WT MEFs (Left) or in p53-null MEFs (Right) in all four samples (p53-WT and p53-null MEFs left untreated or treated with 5-aza-dC). (B) Fold-induction (log scale; 5-aza-dC–treated relative to untreated) of a subset of genes identified as 5-aza-dC–induced in either p53-WT MEFs or p53-null MEFs. Note the scale of induction of IFN-β1 in p53-null MEFs. (C) Validation of Illumina microarray gene expression analysis was performed by RT-PCR using independently isolated RNA from p53-WT and p53-null MEFs left untreated or treated with 10 µM 5-aza-dC for 48 h and specific primers for mouse IFN-β1, H2-Q6, IRF7, and β-actin (control).

Treatment of p53-WT and p53-null MEFs with 5-aza-dC led to activation (by at least fivefold) of 55 and 124 genes, respectively (Tables S1 and S2). Surprisingly, there were no genes shared between these two lists (Venn diagram, Fig. 2A). To investigate the reason underlying this difference, we compared the basal expression levels of genes identified as 5-aza-dC–inducible in either cell line in untreated p53-WT and p53-null MEFs. We found that for the majority of genes induced by 5-aza-dC in p53-WT MEFs, the induced level of RNA expression reached only the basal level observed in untreated p53-null cells (Fig. 2A, Left). Therefore, in the absence of p53, these genes are not suppressed by DNA methylation, and thus p53 has a role as a driver of DNA methylation-mediated gene silencing.

Transcripts up-regulated by 5-aza-dC treatment in p53-null cells demonstrated a completely different pattern of behavior. With a few exceptions, they all remained silent (expressed at low/undetectable levels) in p53-WT MEFs regardless of 5-aza-dC treatment but were strongly up-regulated by 5-aza-dC in p53-null cells (Fig. 2A, Right). The literature indicated that most of these genes are known transcriptional targets lying downstream of type I IFNs (IFN-α and IFN-β) (Table S2). Moreover, one gene in the group with the highest degree of induction encoded mouse IFN-β1 (Fig. 2B and Table S2). The microarray results were validated using semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of several representative genes from the identified subsets (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these data confirm association of p53 deficiency with (i) lack of silencing (high basal expression) of genes that are transcribed in p53-WT cells only after 5-aza-dC treatment and (ii) induction of a strong IFN response by 5-aza-dC.

DNA Demethylation in p53-Null Cells Triggers a Lethal IFN Response.

Production of type I IFNs is a major antiviral response that limits the infectivity of a wide range of DNA and RNA viruses (24). In addition to this major function, type I IFNs also are involved in complex interactions with a wide range of biological outcomes, including cytostatic and cytotoxic effects (24). Therefore, because 5-aza-dC induced a strong IFN response in p53-null (but not in p53-WT) cells, we set out to test the functionality of the induced IFN response and determine whether it is involved in the hypersensitivity of p53-null cells to the drug.

As a measure of the functionality of the IFN response, we assessed the ability of MEFs to support infection with an IFN-sensitive virus, vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) (25). Treatment with 5-aza-dC strongly repressed virus replication only in p53-null cells (Fig. S3), thus confirming the functionality of the IFN response in these cells.

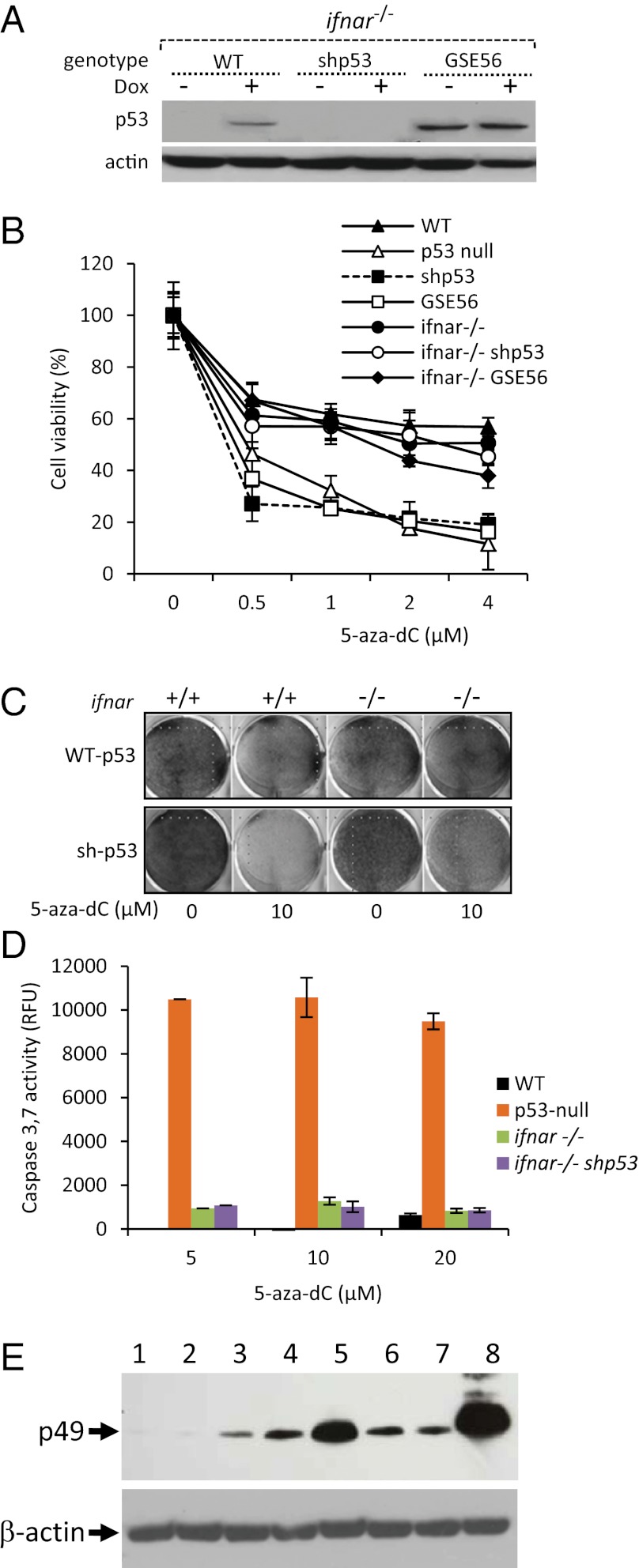

To determine whether the 5-aza-dC–induced IFN response plays a role in the toxicity of the drug toward p53-null cells, we used MEFs from IFN receptor 1 (ifnar) knockout mice (26), which are incapable of developing a type I IFN response. We introduced into these cells the constructs described above that either knock down (shRNA) or inactivate (GSE56) p53 (Fig. 3A). Although these methods of eliminating p53 activity made p53-WT MEFs with intact IFNAR sensitive to 5-aza-dC–mediated killing, they did not sensitize p53-WT, ifnar−/− MEFs (Fig. 3 B and C). No signs of caspase activation were detected in ifnar−/− MEFs treated with 5-aza-dC (Fig. 3D). These observations suggest that the IFN response is a major mediator of death induced by 5-aza-dC in p53-deficient cells.

Fig. 3.

Treatment of p53-null MEFs with 5-aza-dC induces a lethal IFN response. (A) Western blot detection of p53 and β-actin (loading control) proteins in MEFs from ifnar−/− mice expressing endogenous WT p53 (lanes 1 and 2) or shRNA against p53 (shp53, lanes 3 and 4) or the p53-inactivating genetic suppressor element-56 (GSE56, lanes 7 and 8) left untreated (−) or treated (+) with 500 nM doxorubicin (Dox) for 16 h. (B) Cytotoxicity of 5-aza-dC in cells differing in p53 and IFNAR status. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of 5-aza-dC for 5 d. Viability was determined by methylene blue staining and extraction, followed by spectrophotometric quantification. Percent viability is shown relative to control cells treated with 0.1% DMSO. (C) Cytotoxicity of 5-aza-dC in MEFs from ifnar+/+ or ifnar−/− mice expressing endogenous WT p53 (transduced with a nonspecific control shRNA construct) or shRNA against p53 (shp53). Cells were left untreated or treated with 10 µM 5-aza-dC for 120 h before detection of viable cells by methylene blue staining. (D) Caspase-3,7 activity (cleavage of the fluorescent substrate AC-Devd-AMC) in MEFs from p53-WT, p53-null, and ifnar−/− mice and MEFs from ifnar−/− mice expressing shRNA against p53 (shp53). Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of 5-aza-dC for 48 h before the caspase assay. (E) Western blot analysis of expression of the IFN-inducible protein p49 (and β-actin as a loading control) in SCCVII cells: intact (lane 1); mock transfected (lane 2); transfected with the GFP-expression construct plv-CMV-GFP (250 ng per well of a six-well plate; used here and below for monitoring transfection efficiency) (lane 3); transfected with plv-CMV-GFP as above together with 500 ng of RNA (rRNA-depleted fraction) from 5-aza-dC–treated p53-WT (lane 4) and p53-null MEFs (lane 5) and untreated p53-WT (lane 6) and p53-null MEFs (lane 7). Transfection of plv-CMV-GFP and double-stranded poly(I:C) RNA (1μg, an efficient IFN-inducing agent) was used as a positive control (lane 8).

Because DNA demethylation is expected to induce new transcripts, and the IFN response can be triggered by virus-like (i.e., double-stranded) RNA species, we tested the IFN-inducing capacity of RNA isolated from p53-WT and p53-null cells, untreated or treated with 5-aza-dC. After removal of rRNA (to reduce high background levels of abundant and largely double-stranded and abundant RNA species), RNA samples were transfected into SCCVII cells (a mouse head-and-neck cancer–derived cell line known to retain normal type I IFN response), and expression of the IFN-responsive protein p49 (27) was evaluated by Western blotting. Transfection of RNA isolated from 5-aza-dC–treated p53-null cells resulted in dramatically higher induction of p49 expression than seen in RNA from 5-aza-dC–treated p53-WT cells or untreated cells of either genotype (Fig. 3E). This result suggests the presence of an IFN-inducing RNA species specifically in p53-null cells with reduced DNA methylation.

Massive Transcription of Repetitive Elements in p53-Null Cells Treated with 5-aza-dC.

IFN responses normally are triggered by dsRNA interpreted by the cell as an indication of viral infection (24). The gene-expression profiling that we performed using the Illumina MouseWG-6 v2.0 microarray assayed only protein-coding mRNA transcripts and did not reveal any candidate triggers for the suicidal IFN response observed in 5-aza-dC–treated p53-null cells. Therefore, we used a high-throughput RNA sequencing technique to build a comprehensive, unbiased picture of RNA species induced by 5-aza-dC treatment. Total RNA was isolated from p53-WT and p53-null MEFs left untreated or treated for 48 h with 5-aza-dC. After depletion of rRNA, the RNA samples were fragmented, converted to double-stranded cDNA using random primers, ligated with adaptors, and sequenced using a HiSeq2000 instrument (Illumina) with ∼80 × 106 reads per sample (50 nt per read).

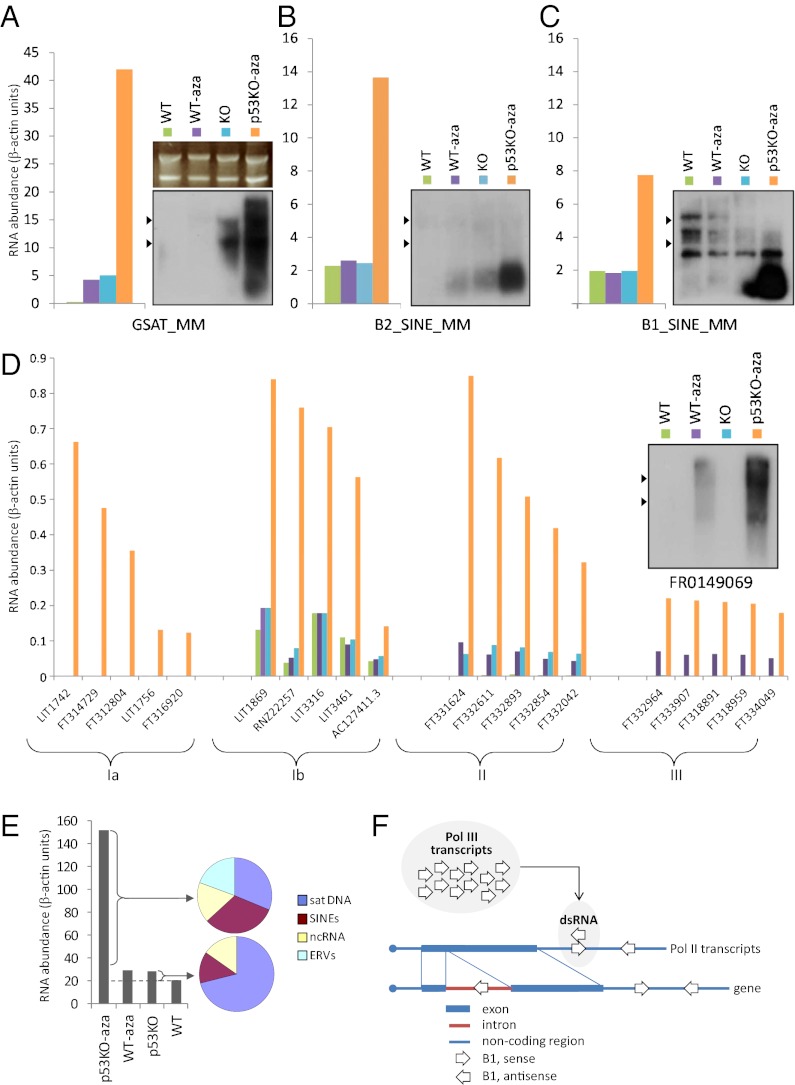

The sequencing results were analyzed by assigning individual cDNA sequences to specific entries in mammalian genome databases that include, besides protein-coding transcripts, functional RNA species (rRNA, small nuclear RNA, tRNA, and so forth), RNAs transcribed from various classes of repeats, and noncoding RNAs (28). The majority of database entries were represented equally among the four RNA samples; however, three types of RNA transcripts were specifically and significantly more abundant in the RNA sample from 5-aza-dC–treated p53-null MEFs. These included (i) both major classes of mouse SINEs, namely B1 and B2 (Fig. 4 B and C), (ii) near-centromeric major (γ) satellite repeats (GSAT) (Fig. 4A), and (iii) a large number of different noncoding RNA species (ncRNAs) (Fig. 4D and Table S3). Importantly, we also identified repeats and ncRNAs that were induced in both p53-WT and p53-null MEFs upon treatment with 5-aza-dC, albeit to a greater extent in p53-null cells. These transcripts apparently represent cases of methylation-based silencing that depends only partially on p53 and included, for example, transcripts of endogenous retrotransposons such as intracisternal A particles (IAP) (Fig. S4), “primitive” relatives of retroviruses present in mouse genomes at about 10,000 copies (29). All these observations were confirmed using Northern blot hybridization with independently isolated RNA samples from untreated and 5-aza-dC–treated p53-WT and p53-null MEFs (Fig. 4 A–D and Fig. S4).

Fig. 4.

Massive transcriptional up-regulation of repetitive elements in p53-null MEFs treated with 5-aza-dC. The abundance of GSAT (A), B2 (B), B1 (C), and ncRNA (D) transcripts in RNA samples isolated from untreated p53-WT MEFs, 5-aza-dC–treated p53-WT MEFs, untreated p53-null MEFs, and 5-aza-dC–treated MEFs relative to the abundance of β-actin mRNA is shown in bar graphs (calculations are based on the results of total RNA sequencing) and Northern blots. For Northern blots the positions of 18S and 28S rRNAs are indicated by arrowheads, and ethidium bromide staining of the gel before transfer is shown in A as a common control for RNA loading and quality. (E) The overall abundance of RNA transcripts representing GSAT DNA (sat DNA), SINEs B1 and B2, ncRNAs, and IAPs in the p53-null (KO) or p53-WT MEFs, untreated or treated with 5-aza-dC, is shown in β-actin units (y axis). Pie diagrams show the proportion of each of the above-listed classes of RNAs in the pool of new transcripts induced by 5-aza-dC treatment in p53-null MEFs (Upper) and in the pool of transcripts present in untreated p53-null cells versus untreated p53-WTcells (Lower). (F) Hypothetical scheme of formation of dsRNA by annealing of RNA-polymerase III-driven transcripts of B1 or B2 SINEs with B1 and B2 sequences present in antisense orientation in polymerase II-driven mRNAs. Introns within mRNA are spliced out before nuclear export, so it is unlikely that a dsRNA will be formed by the annealing of a polymerase III-transcribed SINE sequence to SINE sequences within mRNA introns for further detection by pattern recognition receptors outside the nucleus, such as PKR.

Northern blotting demonstrated that both 5-aza-dC–treated and untreated p53-WT cells, as well as untreated p53-null cells, expressed sequences corresponding to B1 SINE predominantly within large RNA transcripts, whereas RNA corresponding to individually transcribed B1 elements (116-bp-long RNA polymerase III-driven transcript) was barely detectable (Fig. 4C). However, in the sample from 5-aza-dC–treated p53-null MEFs, the most intense signal was concentrated in the size range of single-element transcripts, thus indicating that DNA demethylation in the absence of p53 results in strong activation of transcription of B1 and B2 elements. Annealing of these induced monomeric-positive strands of B1 and B2 transcripts to antisense-oriented B1 and B2 sequences present in the untranslated regions of numerous protein-coding mRNAs can be predicted to create a large pool of dsRNA potentially capable of triggering an IFN response (Fig. 4F).

In contrast to SINEs, transcripts of GSAT sequences vary in length from 240 bp to more than 10 kb (Northern blot in Fig. 4A). Detection of GSAT transcripts can be revealed by radiolabeled probes representing both positive and negative strands of GSAT DNA as demonstrated by dot-blot hybridization with the probes specific for different RNA strands, indicative of bidirectional transcription. This result is consistent with previous reports in which temporary activation of GSAT transcription and the appearance of dsRNA of various lengths was observed during specific stages of embryonic development (30) and in the hearts of old adult mice (31). dsRNA formed by annealed complementary GSAT RNA strands could trigger IFN induction.

To gain an appreciation of the potential biological impact of the identified 5-aza-dC–induced transcripts in p53-null MEFs, we estimated their overall abundance vis-à-vis the abundance of mRNAs for β-actin, a highly expressed transcript commonly used as a reference in gene-expression studies. We calculated the relative representation of RNAs transcribed from SINEs (B1 and B2), satellite DNA (GSAT and SATMIN), IAPs, and ncRNAs in each sample based on the proportions of their corresponding sequences in RNA samples used for high-throughput sequencing. The results shown in Fig. 4E demonstrate that the amount of new RNA (counted as the number of monomeric copies) synthesized specifically in p53-null cells following treatment with 5-aza-dC was more than 150 times greater than the level of β-actin mRNA. Two-thirds of this new pool of RNA comprised transcripts of SINEs and satellite DNA in nearly equal proportions, and the remaining one-third consisted of equal proportions of IAP transcripts and ncRNAs. Interestingly, however, IAPs were not among the RNA species that showed differential expression between untreated p53-null and untreated p53-WT MEFs, thus suggesting that their DNA methylation-based silencing is not strictly p53 dependent.

Structural Properties of Major Classes of p53-Controlled Repeats.

Reconstruction of the phylogenetic history of SINEs suggests that their amplification in mammalian genomes started about 65 million years ago and involved a series of explosions that created subfamilies of repeats, each with shared mutations (9, 12, 32). To determine whether B1 and B2 transcription initiated by DNA hypomethylation in p53-null cells involved random or specific subsets of repeats, we calculated the deviation from the consensus SINE sequence (built by analyzing the entire SINE family in the mouse genome) for each nucleotide position of the B1 and B2 sequences identified in sequencing our four RNA samples (p53-WT and p53-null MEFs, untreated and 5-aza-dC–treated). No major differences were found in the profiles of nucleotide polymorphisms along B1 and B2 transcripts among thefour samples, thus indicating roughly random activation of transcription of different subsets of SINEs in p53-null cells treated with 5-aza-dC (correlation coefficients >0.96). However, more precise analysis revealed significant shifts in frequency of mutations in a number of positions in B1 transcripts in the RNA sample from 5-aza-dC–treated p53-null MEFs as compared with the three other subsets. Interestingly, nucleotide substitutions were significantly less frequent in specific positions within putative p53-binding sequences (Fig. 5 E and F).

Fig. 5.

Structural features of major repetitive sequences that are transcriptionally repressed by p53. (A and B) Comparison of putative p53-binding sites from B1, B2, and GSAT repeats with “activating” and “repressing” p53-binding consensus sequences (32). (C and D) p53 binding to its consensus sequence within a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide was detected by EMSA (C, lane 1), and the specificity of the observed p53-probe complex was confirmed by supershift with the anti-p53 antibody Ab421 (lane 2). Unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides were added at 10:1, 20:1, and 40:1 molar excess over the labeled probe in lanes 3–5 (oligonucleotide containing the p53-binding consensus sequence, positive control), lanes 6–8 (an 84-bp oligonucleotide containing the first two B1-derived putative p53-binding sequences), and lanes 9–11 (λpL promoter-derived oligonucleotides of similar length, negative control). Bands corresponding to p53-binding complexes were quantified by densitometry and normalized to the free radio-labeled probe. (E) Relative frequency of deviations from consensus at specific nucleotides positions within putative p53-binding sites of B1 elements activated by 5-aza-dC in p53-null MEFs. Mutation rates (calculated as P values) were determined for the indicated sets of nucleotides of the three putative p53-binding sites found in B1 consensus sequence. The directed minimal difference was calculated between P values in the 5-aza-dC–treated p53-KO sample versus the first three samples. Analysis of each key position (highlighted in red) of the p53-binding sites within the SINE B1 revealed that the positive minimal differences (black bars) are indicative of lower mutation rates found in the treated p53-KO samples as compared with any other sample set comprising other nucleotides from p53 recognition element (blue bars; shown for only one of four sets analyzed). (F) Comparison of the mutation rate in the key nucleotide positions with mutation rates in other nucleotides within putative p53-binding sites in all four series was performed by the voting method. For each series, the sum of squares of positive differences is χ2 distributed; the sum of squares of the negative differences also is χ2 distributed. The first χ2 value indicates the overall voting of series’ positions for lower rate of mutation in 5-aza-dC–treated p53-KO. Conversely, the second χ2 value is voting for higher overall rate of mutations in the series. The ratio of these two values normalized by the corresponding degrees of freedom (numbers of positive and negative differences) is F-distributed. Results are shown as minus log P values of the F-test in key-position series (red) and four control series (blue). The F-test P values of a lower mutation rate in the 5aza+p53ko sample across five series of positions are listed. *Only one P value (0.004 of the key positions) is statistically significant.

p53 is known as a repressor of transcription acting via recognition of specific sequences that are similar to those that serve as p53-binding sites in p53-induced genes (33, 34). A search for putative p53-binding–like sites revealed a series of candidate sequences in B1, B2, and GSAT elements (Fig. 5 A and B). GSAT elements were found to be especially enriched with potential p53-binding sequences. The functionality of predicted p53-binding sites was tested using EMSA with synthetic oligonucleotides representing different B1 fragments incubated with nuclear extracts of mouse cells known to have WT and functional p53. Although the oligonucleotides used did not show stable binding with p53 under the applied conditions, they nevertheless were capable of inhibiting p53 binding to a control oligonucleotide containing a consensus p53-binding site (Fig. 5 C and D). This inhibition was dependent on the presence of intact putative p53-binding sites in B1-derived oligonucleotides, because point mutations at key nucleotides of the p53-binding sequence completely abrogated the ability of oligonucleotide to compete for p53 binding (Fig. S5). Remarkably, mutations were less frequent in these particular nucleotides than in the rest of the positions within p53-binding sites of B1 transcripts induced by 5-aza-dC treatment (Fig. 5 E and F). These observations suggest that B1 repeats are capable of specific p53 binding, albeit with low affinity, and that this binding is required for their transcriptional repression by p53.

Transcription of Repeats and ncRNAs Can Occur in Tumors.

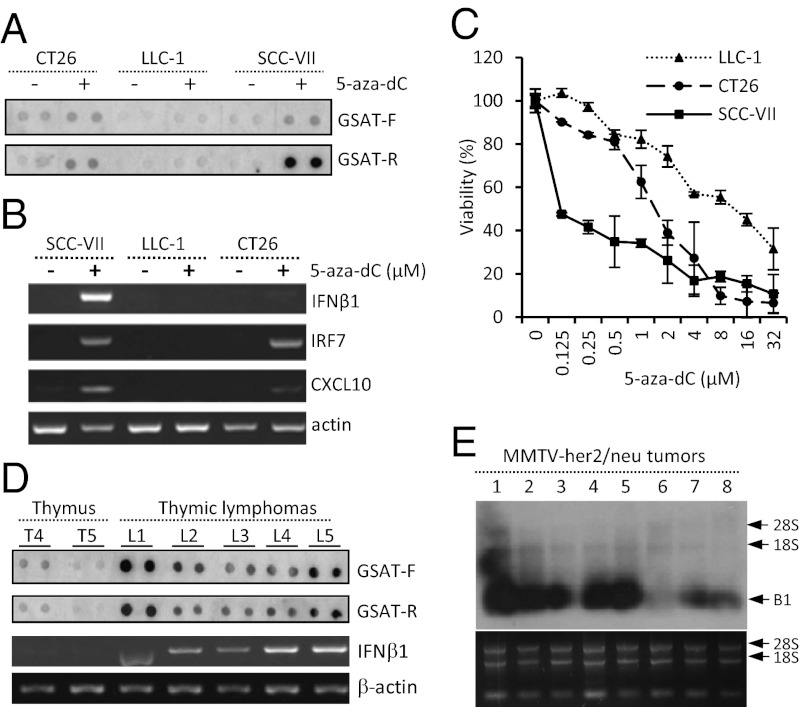

p53 is the most frequently mutated gene in tumors. However, even in tumors that retain WT p53 gene sequences, p53 commonly is inactivated by other means [e.g., viral protein expression, overexpression of the natural p53 inhibitor mdm2, or loss of Arf (35)]. Hence, we hypothesized that tumor cells might be prone to induction of transcription of repeats and ncRNAs following 5-aza-dC treatment, as was observed in p53-null MEFs. To test this hypothesis, we chose three mouse tumor-derived cell lines (SCC-VII, CT26, and LLC) without significant levels of basal repetitive element transcription (as illustrated by low levels of GSAT transcripts; Fig. 6A). We found that SCC-VII, CT26, and LLC cells showed strong, intermediate, and undetectable expression of GSAT RNA, respectively, upon treatment with 5-aza-dC (Fig. 6A). In addition, we detected strong up-regulation of the mRNAs encoding IFN-β1 and its downstream responsive genes, IFN regulatory factor 7 (IRF7) and CXCL10, in 5-aza-dC–treated SCC-VII cells and, to a somewhat lesser extent, in 5-aza-dC–treated CT26 cells (Fig. 6B). In contrast, none of these IFN response-associated transcripts was detected in 5-aza-dC–treated LLC cells. Consistent with these findings, SCC-VII cells were the most 5-aza-dC–sensitive cell line (LD50 = 0.125 µM), CT26 cells showed intermediate sensitivity (LD50 = 2 µM), and LLC cells were the least sensitive (LD50 = 14 μM) (Fig. 6C). The identified positive correlation between transcription of repeats, induction of an IFN response, and sensitivity to 5-aza-dC supports our model in which tumors with reduced p53 function (36–38) are prone to activation of transcription of repeats under conditions of reduced DNA methylation. These results suggest that the sensitivity of tumor cells with silent repeats to 5-aza-dC (i.e., the drug decitabine approved for treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome and considered for anticancer use) may depend on whether they have functional p53.

Fig. 6.

Detection of transcripts of repetitive elements in mouse tumor cell lines and spontaneous tumors. (A) Detection of mouse GSAT sequences in total RNA from mouse tumor cell lines CT-26 (colon tumor), LLC-1 (Lewis lung carcinoma), and SCC-VII (squamous cell carcinoma) left untreated or treated with 10 µM 5-aza-dC for 48 h. Dot blotting was performed with 500 ng total RNA per dot and single-strand hybridization probes GSAT-F and GSAT-R. (B) Detection of IFN-β1, IRF-7, CXCL10, and β-actin (loading control) mRNA by RT-PCR in the cells described in A. (C) Cytotoxicity of 5-aza-dC in LLC-1, CT26, and SCC-VII cells. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of 5-aza-dC for 5 d. Viability was determined by methylene blue staining and extraction, followed by spectrophotometric quantification. Percent viability is shown relative to control cells treated with 0.1% DMSO. (D) (Upper Two Panels) GSAT sequences were detected in total RNA from thymic lymphomas of p53-null mice (five tumors, L1–L5, from five different mice assayed in duplicate) and in two normal thymuses (T4 and T5) isolated from p53-null mice using dot blotting as described in A. (Lower Two Panels) RT-PCR analysis of IFN-β1 and β-actin (loading control) mRNA expression. (E) Northern hybridization was used to detect SINE B1 sequences in total RNA from MMTV-her2/neu mammary tumors (eight tumors from eight different mice). 18S and 28S rRNA levels detected by ethidium bromide staining confirmed equivalent RNA quality and loading for all tumors.

Decreased genome-wide DNA methylation is another common property of tumors acquired during in vivo growth (39). Together with inactivation of p53, this decreased methylation could create conditions sufficient to induce transcription of repeats and ncRNAs normally suppressed by a combination of p53 and DNA methylation. Therefore, we hypothesized that transcription of repeats leading to the induction of an IFN response might occur spontaneously during tumor growth and progression in vivo. We tested this hypothesis in two mouse tumor models. First, we showed that all tested spontaneous thymic lymphomas [the tumors that develop most frequently in cancer-prone p53-null mice (40)] contained much higher levels of repetitive element transcripts than normal tissues of p53-null mice, including thymuses of p53-null mice before lymphoma development (Fig. 6D, shown for GSAT RNA transcribed from both DNA strands). As in p53-null MEFs treated with 5-aza-dC, the activation of transcription of repeats correlated with the induction of IFN response, as demonstrated by RT-PCR results (Fig. 6D).

Similarly, repetitive element expression was observed in six of the eight the mammary gland tumors that developed spontaneously in untreated MMTV-her2/neu transgenic mice (41) (Fig. 6E). Previous reports indicate acquisition of missense mutations in at least 37% of these tumors (42). Note that although expression of only one specific class of repeats is shown for each of the above cases, activation of GSAT, B1, and B2 always occurred together. Our finding that growing tumors express high levels of repeats capable of generating dsRNA and subsequently inducing a lethal IFN response suggest that such tumors have passed successfully through selection for resistance to endogenous IFN toxicity.

Discussion

This study reveals a function of p53 that, in cooperation with DNA methylation, keeps large families of interspersed and tandem repeats transcriptionally dormant. Treatment of p53-deficient but not p53-WT cells with the DNA-demethylating agent 5-aza-dC was shown to cause transcriptional derepression of several classes of normally silent interspersed repeats (e.g., SINEs such as B1 and B2 repeats), tandem DNA satellites (e.g., GSAT), and ncRNAs. Together, these elements represent a significant proportion of the mouse genome (>10%) and, when transcribed, give rise to new RNA species comparable in their abundance to the bulk of cellular mRNA.

Transcriptional derepression of repeats resulting from a combined lack of p53 function and DNA methylation was accompanied by induction of the classical type I IFN signaling pathway, which in MEFs is driven by IFN-β1 and leads to apoptotic cell death. We have named this phenomenon TRAIN. The critical role played by the IFN response in death of MEFs under conditions of TRAIN was demonstrated using cells deficient in IFN receptor expression. Although the precise mechanism underlying this toxicity remains to be determined, our findings are consistent with a growing body of evidence indicating that activation of a strong IFN response by dsRNA can result in apoptosis mediated either by induction of the proapoptotic protein kinase R (PKR) and 2’-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS)/RNase L pathways or activation of TRAIL/FAS death receptors (24).

In mammalian cells, IFN signaling commonly is triggered as an antiviral defense mechanism in response to dsRNA produced during viral replication (24). Our results suggest that RNA species produced following transcriptional derepression of endogenous repeats in the absence of p53 and methylation also can trigger of the IFN response. Transcripts of repetitive elements, retrotransposons, and satellite DNA sequences can form dsRNA because of their intense secondary structure and the presence of complementary transcripts in the cell. For SINEs, such complementary sequences exist in noncoding regions of mRNAs that were transcribed through SINEs integrated in their antisense orientation (Fig. 4F). In the case of GSAT, both strands are transcribed, thereby producing cRNA strands (30). Although we have shown that total RNA from 2-aza-dC–treated p53-null cells has stronger IFN-inducing capacity than RNA from untreated p53-null cells or from both treated and untreated p53-WT cells (Fig. 3E), our current technical capabilities are not sufficient to determine the relative impact of each of these classes of transcripts on TRAIN. In fact, the scale of expression of “new” transcripts that appear in p53−/− cells treated with 5-aza-dC is so strong and their copy number in the genome is so high as to preclude the use of any gene knockout or knockdown technique to assess this impact directly. Nevertheless, because transcripts of SINEs and GSAT, both of which are capable of forming dsRNAs, comprise the major proportion of new RNA synthesized in p53-null cells following DNA hypomethylation, it is highly probably that these RNA species are responsible for IFN induction.

Overall, our results support a model in which epigenetic silencing of repeats (an essential condition for genomic stability and viability of currently existing species) is controlled by three factors: (i) p53-mediated transcriptional silencing, (ii) DNA methylation-mediated suppression of transcription, and (iii) a suicidal IFN response which eliminates cells that escape the first two lines of control. This model presents a major role for p53 as a “guardian of repeats,” which is likely an important component of its function as a “guardian of the genome” (43). In fact, for at least interspersed repeats (products of reverse transcription), transcription is an essential prerequisite for their amplification and subsequent possible insertional mutagenesis. Given the abundance of repeats in mammalian genomes and their potential for producing large amounts of transcripts (which in the presence of reverse transcriptase may be converted into insertional mutagens), it is reasonable to state that silencing of repeats is likely an evolutionarily important function of p53 that may have been critical for survival of predecessors of current species during times of active repeat amplification. Our work also reveals a function for the IFN response in addition to its role in antiviral innate immunity: maintenance of genomic stability through the elimination of cells that have lost epigenetic silencing of interspersed and tandem repeats. Although all the results reported here were obtained in mice, the literature provides numerous indications that TRAIN may be universal among mammals. For example, aberrant overexpression of satellite repeats was reported recently in pancreatic and other epithelial human cancers (18). In addition, hypomethylation and activation of polymerase III-driven Alu (the only major SINE in the human genome) transcription was found in human tumors (44, 45). TRAIN is likely to be the explanation for the previously described phenomenon of inhibition of growth of pancreatic tumor cells by 5-aza-dC accompanied with the induction of IFN response signaling (46).

Although the precise mechanism by which p53 controls silencing of repeats remains to be defined, it is reasonable to consider that it may involve the known transcriptional repressor function of p53 (34). The power of p53 as an epigenetic silencer is implied by the fact that none of the multiple, independently generated lines of transgenic mice carrying p53-responsive reporter genes (47–49) was able to maintain transgene inducibility for more than two generations (in contrast to mice with reporters of other transcriptional regulators). p53 exerts its transcriptional repressor function by binding to sites that are similar to those that mediate its transcriptional activation function but that have more sequence flexibility (50). Thus, we hypothesized that p53-mediated silencing of repeats might occur through a similar mechanism involving direct binding of p53 to specific sites within the repetitive elements. Support for this hypothesis was provided by our identification of predicted p53-binding sites within elements representing all the major classes of repeats that become activated in the absence of p53 and DNA methylation and demonstration of p53 binding (albeit weak) to such sites in EMSA competition assays. After low-affinity binding to sites in repeat elements, p53 may recruit other factors to establish transcriptional repression. Candidates for such factors include DNMT1 (51) and DNA methyltransferase 3a (DNMT3a) (52), which have been shown to interact with p53 and execute p53-mediated gene repression. It should be noted, nevertheless, that other p53-independent mechanisms must exist to explain DNA methylation-mediated silencing of repeats observed in tissues of p53-null mice. In this regard, it would be interesting to determine whether other p53 family members (e.g., p63 or p73) might contribute to the suppression of TRAIN.

A striking observation related to the phenomenon of TRAIN is the presence of p53-binding sites within major classes of SINEs of both primates [Alu repeats (53)] and rodents [B1, B2, and GSAT (this work)], even though primate and rodent repeats evolved independently after the divergence of these two phylogenetic branches. The presence of these sites suggests that p53 may play a similar role in silencing SINEs in both genera and that this role may be evolutionarily important for preventing SINE expansion and maintaining genetic stability.

The contribution of the TRAIN-suppressor function of p53 to its tumor-suppressor activity (if any) remains to be elucidated. Tumors developing spontaneously in p53-null mice demonstrated naturally occurring derepression of repetitive elements involved in TRAIN, thus suggesting a potential link between TRAIN and carcinogenesis. Whether unleashed expression of repeats in tumors causes amplification of repeats and increased genomic instability remains to be determined. It is noteworthy that activation of transcription of reverse transcriptase-associated repetitive elements was limited to SINEs and did not involve long interspersed nuclear elements, the likely source of functional reverse transcriptase in mammalian genome (54).

Our observation of repeat derepression in spontaneous breast tumors from p53-WT MMTV-neu transgenic mice suggests that tumor progression provides a platform upon which such derepression occurs naturally. Tumors, including those that develop in this particular model (42), frequently are characterized by p53 inactivation, which enables unconstrained cell proliferation. There also is extensive evidence showing that the general degree of DNA methylation declines during tumor progression (23). Hence, both conditions required to initiate TRAIN (loss of p53 function and hypomethylation) occur naturally and with high frequency in tumors. In fact, transcription of normally silent and heavily methylated sequences representing different types of repeats (both interspersed and tandem repeats) has been shown to occur in tumors (refs. 18, 45, and this work) as well as under other stress conditions (15). Nevertheless, tumor cells apparently escape TRAIN-induced cell death. This avoidance presumably involves selection of tumor cells that have acquired changes that make them resistant to suicidal IFN induction, thus implying an important tumor-suppressor role for the IFN pathway. In fact, the combination of p53 deficiency with the knockout of the irf1 gene, one of the major triggers of IFN signaling by dsRNA (24), dramatically increases the frequency and spontaneous tumor development (55).

Tolerance of tumor cells to constitutive expression of repetitive elements associated with TRAIN is likely caused by (i) acquired defects in IFN induction or (ii) acquired or intrinsic resistance to the suicidal IFN response. Consistent with this notion, there are numerous indications of loss of IFN function in multiple tumor types (56, 57), including, for example, homozygous loss of chromosome 9p21, which contains the genes for all type I IFNs (58, 59). In this regard, it should be noted that tumor cells frequently are hypersensitive to lytic viruses (60), a property that could be well explained by acquisition of defects in IFN responses driven by the necessity to survive TRAIN.

Thus, the phenomenon of TRAIN explains a series of previously unconnected but well-documented properties of tumor cells, including transcription of repeats, deregulation of IFN function, and increased sensitivity to lytic viruses. Identification of specific derepressed sequences involved in TRAIN in human cells and development of assays for detection of TRAIN in clinical samples of human tumors will be an essential step in linking this biological process to the diagnosis of specific tumor types and stages of progression as well as the prediction of their prognosis and sensitivity to treatment. For example, detection of TRAIN-associated marker transcripts or signs of constitutively active IFN signaling (without signs of toxicity) could be used to assess p53 functionality in tumors.

Materials and Methods

Analysis of Results of Total RNA Sequencing.

Mapping of Illumina reads onto repetitive elements and ncRNA species was performed by the BOWTIE program (61) under default parameters. As to ndRNAs, the sequences from all of the RNAdb (http://research.imb.uq.edu.au/rnadb/) subbases (fantom 3, RNAz, and others) were used for mapping of reads from the samples. The Repbase database (www.girinst.org/repbase/) was used as a set of unique repetitive elements for the mapping. The expression level of each ncRNA and repetitive element was calculated as median per-position coverage of its sequence by mapped reads, the per-position normalized measure of expression that does not depend on the sequence length. To give a biological dimension to this measure of expression for the studied ncRNA species and repetitive elements, each value was recalculated in “β-actin units.” Namely, first, the reads of four RNA-sequence samples were mapped onto β-actin mRNA, and the median per-position counts of this mRNA across samples were calculated. Next, the per-position measure of expression for a particular ncRNA or a repetitive element in a sample was divided by the per-position value of expression for β-actin in the same sample, giving the expression level of each studied sequence across the four RNA-seq samples in units of the β-actin expression in the corresponding sample.

Mapping of reads from the RNA samples onto B1 and B2 consensus sequences was performed by a BLAST-like alignment program that detects mutations more accurately than the programs based on Burrows–Wheeler indexing. For each position, a significance of the mutation in three treated samples regarding the WT sample was calculated via Poisson statistics. Namely, for each position of the consensus, the expected number of counts of the consensus nucleotide at this position in a treated sample was calculated based on the frequency of this nucleotide in the WT sample. A distance in SD units between the real number of counts of the consensus nucleotide in a treated sample and expected number of nucleotide counts defines the polymorphism of this particular position. A limit of 20 SDs was considered the threshold of mutation significance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Patricia Stanhope-Baker for help in manuscript preparation; Gus Frangou, Mikhail Makhanov, Jaime Wetzel, Anatoli Gleiberman, and Natalia Fedtsova for technical help; and Katerina Gurova for critical reading of the manuscript. This work fulfilled part of the requirements for the PhD earned by K.I.L. at State University of New York at Buffalo. This work was funded by a grant from Tartis, Inc. (to A.V.G.) and a grant from the National Institutes of Health AI073303 (to G.C.S.).

Footnotes

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

See Author Summary on page 22 (volume 110, number 1).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1216922110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Makałowski W. Genomic scrap yard: How genomes utilize all that junk. Gene. 2000;259(1-2):61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00436-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kramerov DA, Vassetzky NS. SINEs. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2011;2(6):772–786. doi: 10.1002/wrna.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smit AF. Interspersed repeats and other mementos of transposable elements in mammalian genomes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9(6):657–663. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostertag EM, Kazazian HH., Jr Biology of mammalian L1 retrotransposons. Annu Rev Genet. 2001;35:501–538. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.091032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charlesworth B, Sniegowski P, Stephan W. The evolutionary dynamics of repetitive DNA in eukaryotes. Nature. 1994;371(6494):215–220. doi: 10.1038/371215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plohl M, Luchetti A, Mestrović N, Mantovani B. Satellite DNAs between selfishness and functionality: Structure, genomics and evolution of tandem repeats in centromeric (hetero)chromatin. Gene. 2008;409(1-2):72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quentin Y. Successive waves of fixation of B1 variants in rodent lineage history. J Mol Evol. 1989;28(4):299–305. doi: 10.1007/BF02103425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deininger PL, Batzer MA. Mammalian retroelements. Genome Res. 2002;12(10):1455–1465. doi: 10.1101/gr.282402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amariglio N, Rechavi G. Insertional mutagenesis by transposable elements in the mammalian genome. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1993;21(3):212–218. doi: 10.1002/em.2850210303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrigno O, et al. Transposable B2 SINE elements can provide mobile RNA polymerase II promoters. Nat Genet. 2001;28(1):77–81. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramerov DA, Vassetzky NS. Origin and evolution of SINEs in eukaryotic genomes. Heredity (Edinb) 2011;107(6):487–495. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2011.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carnell AN, Goodman JI. The long (LINEs) and the short (SINEs) of it: Altered methylation as a precursor to toxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2003;75(2):229–235. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhee I, et al. DNMT1 and DNMT3b cooperate to silence genes in human cancer cells. Nature. 2002;416(6880):552–556. doi: 10.1038/416552a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu WM, Chu WM, Choudary PV, Schmid CW. Cell stress and translational inhibitors transiently increase the abundance of mammalian SINE transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23(10):1758–1765. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.10.1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen TA, Von Kaenel S, Goodrich JA, Kugel JF. The SINE-encoded mouse B2 RNA represses mRNA transcription in response to heat shock. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11(9):816–821. doi: 10.1038/nsmb813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jang KL, Latchman DS. The herpes simplex virus immediate-early protein ICP27 stimulates the transcription of cellular Alu repeated sequences by increasing the activity of transcription factor TFIIIC. Biochem J. 1992;284(Pt 3):667–673. doi: 10.1042/bj2840667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagan CR, Rudin CM. DNA cleavage and Trp53 differentially affect SINE transcription. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46(3):248–260. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ting DT, et al. Aberrant overexpression of satellite repeats in pancreatic and other epithelial cancers. Science. 2011;331(6017):593–596. doi: 10.1126/science.1200801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nieto M, et al. The absence of p53 is critical for the induction of apoptosis by 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. Oncogene. 2004;23(3):735–743. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ossovskaya VS, et al. Use of genetic suppressor elements to dissect distinct biological effects of separate p53 domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(19):10309–10314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bunz F, et al. Disruption of p53 in human cancer cells alters the responses to therapeutic agents. J Clin Invest. 1999;104(3):263–269. doi: 10.1172/JCI6863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoo CB, Jones PA. Epigenetic therapy of cancer: Past, present and future. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5(1):37–50. doi: 10.1038/nrd1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3(6):415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrg816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borden EC, et al. Interferons at age 50: Past, current and future impact on biomedicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6(12):975–990. doi: 10.1038/nrd2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu S-Y, Sanchez DJ, Aliyari R, Lu S, Cheng G. Systematic identification of type I and type II interferon-induced antiviral factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(11):4239–4244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114981109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller U, et al. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science. 1994;264(5167):1918–1921. doi: 10.1126/science.8009221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fensterl V, White CL, Yamashita M, Sen GC. Novel characteristics of the function and induction of murine p56 family proteins. J Virol. 2008;82(22):11045–11053. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01593-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: A revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(1):57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barbot W, Dupressoir A, Lazar V, Heidmann T. Epigenetic regulation of an IAP retrotransposon in the aging mouse: Progressive demethylation and de-silencing of the element by its repetitive induction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(11):2365–2373. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.11.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Probst AV, et al. A strand-specific burst in transcription of pericentric satellites is required for chromocenter formation and early mouse development. Dev Cell. 2010;19(4):625–638. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaubatz JW, Cutler RG. Mouse satellite DNA is transcribed in senescent cardiac muscle. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(29):17753–17758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kidwell MG, Lisch DR. Perspective: Transposable elements, parasitic DNA, and genome evolution. Evolution. 2001;55(1):1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho J, Benchimol S. Transcriptional repression mediated by the p53 tumour suppressor. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10(4):404–408. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang B, Xiao Z, Ren EC. Redefining the p53 response element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(34):14373–14378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903284106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408(6810):307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hauser U, et al. Reliable detection of p53 aberrations in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck requires transcript analysis of the entire coding region. Head Neck. 2002;24(9):868–873. doi: 10.1002/hed.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langlois MJ, et al. The PTEN phosphatase controls intestinal epithelial cell polarity and barrier function: Role in colorectal cancer progression. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12):e15742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burdelya LG, et al. Inhibition of p53 response in tumor stroma improves efficacy of anticancer treatment by increasing antiangiogenic effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy in mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66(19):9356–9361. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smet CD, Loriot A. Epigenetic scars of a neoplastic journey DNA hypomethylation in cancer. Epigenetics. 2010;5:206–213. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.3.11447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donehower LA, et al. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356(6366):215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green JE, Hudson T. The promise of genetically engineered mice for cancer prevention studies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(3):184–198. doi: 10.1038/nrc1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li B, Rosen JM, McMenamin-Balano J, Muller WJ, Perkins AS. neu/ERBB2 cooperates with p53-172H during mammary tumorigenesis in transgenic mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(6):3155–3163. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lane DP. Cancer. p53, guardian of the genome. Nature. 1992;358(6381):15–16. doi: 10.1038/358015a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lerat E, Sémon M. Influence of the transposable element neighborhood on human gene expression in normal and tumor tissues. Gene. 2007;396(2):303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li TH, Kim C, Rubin CM, Schmid CW. K562 cells implicate increased chromatin accessibility in Alu transcriptional activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(16):3031–3039. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.16.3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Missiaglia E, et al. Growth delay of human pancreatic cancer cells by methylase inhibitor 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine treatment is associated with activation of the interferon signalling pathway. Oncogene. 2005;24(1):199–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Komarova EA, et al. Transgenic mice with p53-responsive lacZ: p53 activity varies dramatically during normal development and determines radiation and drug sensitivity in vivo. EMBO J. 1997;16(6):1391–1400. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gottlieb E, et al. Transgenic mouse model for studying the transcriptional activity of the p53 protein: Age- and tissue-dependent changes in radiation-induced activation during embryogenesis. EMBO J. 1997;16(6):1381–1390. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacCallum DE, et al. The p53 response to ionising radiation in adult and developing murine tissues. Oncogene. 1996;13(12):2575–2587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riley T, Sontag E, Chen P, Levine AJ. Transcriptional control of human p53-regulated genes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(5):402–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Estève PO, Chin HG, Pradhan S. Human maintenance DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase and p53 modulate expression of p53-repressed promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(4):1000–1005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407729102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang YA, et al. DNA methyltransferase-3a interacts with p53 and represses p53-mediated gene expression. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4(10):1138–1143. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.10.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cui F, Sirotin MV, Zhurkin VB. Impact of Alu repeats on the evolution of human p53 binding sites. Biol Direct. 2011;6:2. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-6-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beck CR, Garcia-Perez JL, Badge RM, Moran JV. LINE-1 elements in structural variation and disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2011;12:187–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082509-141802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nozawa H, et al. Loss of transcription factor IRF-1 affects tumor susceptibility in mice carrying the Ha-ras transgene or nullizygosity for p53. Genes Dev. 1999;13(10):1240–1245. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haus O. The genes of interferons and interferon-related factors: Localization and relationships with chromosome aberrations in cancer. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2000;48(2):95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heyman M, et al. Interferon system defects in malignant T-cells. Leukemia. 1994;8(3):425–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fountain JW, et al. Homozygous deletions within human chromosome band 9p21 in melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(21):10557–10561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lydiatt WM, Davidson BJ, Schantz SP, Caruana S, Chaganti RS. 9p21 deletion correlates with recurrence in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 1998;20(2):113–118. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199803)20:2<113::aid-hed3>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ring CJA. Cytolytic viruses as potential anti-cancer agents. J Gen Virol. 2002;83(Pt 3):491–502. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-3-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10(3):R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]