Abstract

Ovarian cancer has a clear predilection to metastasize to the peritoneum, which represents one of the most important prognostic factors of poor clinical outcome. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor is significantly overexpressed during the malignant progression of human ovarian cancer. Here, using lentiviral-based small interfering RNA (siRNA) technology to downregulate GnRH receptor in metastatic ovarian cancer cells, we show that GnRH receptor is an important mediator of ovarian cancer peritoneal metastasis. GnRH receptor downregulation dramatically attenuated their adhesion to the peritoneal mesothelium. By inhibiting the expression of GnRH receptor, we showed decreased expression of α2β1 and α5β1 integrin and adhesion to specific extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. This was also associated with a reduction of P-cadherin. Furthermore, adhesion of ovarian cancer cells to different ECMs and the mesothelium were abrogated in response to β1 integrin and P-cadherin reduction, confirming that the effects were β1 integrin- and P-cadherin–specific. Using a mouse model of human ovarian cancer metastasis, we found that the inhibition of GnRH receptor, β1 integrin, and P-cadherin significantly attenuated tumor growth, ascites formation, and the number of metastatic implants. These results define a new role for GnRH receptor in early metastasis and offer the possibility of novel therapeutic targets.

Introduction

Ovarian cancer has the highest mortality rate of all gynecologic tumors.1 This is due largely to the advanced stage (stages III and IV) of disease in the majority (75%) of patients at the time of diagnosis. Unlike most solid tumors, ovarian cancer rarely disseminates through the vasculature but has a high propensity to metastasize to the peritoneum, and successful adhesion is a key step in the metastasis formation of ovarian cancer cells.2 This unique metastatic mechanism poses distinct therapeutic challenges, in which current treatments are not effective (5-year survival <25%).3 Unraveling the molecular mechanisms underlying this process may lead to new therapeutic targets.

The integrins, a major family of cell surface receptors composed of various α- and β-transmembrane subunits, mediate cellular contacts to the extracellular matrix (ECM),4 and is proposed to be a critical factor in metastatic dissemination of ovarian cancer cells. Several studies have documented an increased expression of integrins and the hyaluronan receptor CD44 during ovarian neoplastic progression.5,6,7 Because of the unique function in mediating cell–cell interaction, cadherin adhesion molecules are also postulated to play a role in organ-specific metastasis,8 but their role in ovarian cancer metastasis has not been established. The factors regulating such communications are also largely unknown.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is a decapeptide well known for its role in the ovary. With the findings of the widespread presence (>80%) of GnRH receptor in primary cultures of ovarian carcinomas and tumor biopsy specimens, alterations of GnRH receptor may be one of the most common abnormalities in human ovarian cancer.9,10 Although it was originally described as being exclusively involved in cell proliferation, we recently published data describing GnRH in other aspects of tumor progression, such as metastasis.11,12,13 These results implicate a role of the GnRH regulatory system in ovarian cancer. Peritoneal dissemination of ovarian cancer cells typically involves several steps, including tumor cell attachment, invasion, and growth within the peritoneum. Whereas previous studies have focused on the role of GnRH on migration and invasion,11,12,13 it is still not known whether GnRH receptor overexpression affects the peritoneal adhesion formation, which represents the first and rate-limiting step for metastatic spread. Nor is it clearly exactly how GnRH receptor contributes to this process. Moreover, given the potential side effects of GnRH receptor antagonists,14 it is of great interest to develop a safe and effective therapeutic approach.

In this study, we show for the first time that stable small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of GnRH receptor in the highly malignant ovarian cancer cells abolishes adhesion and peritoneal metastasis in vitro and in vivo. We also provide mechanistic insights suggesting that GnRH receptor action through metastasis-associated cell surface proteins β1 integrin and P-cadherin, modulating their expression and function.

Results

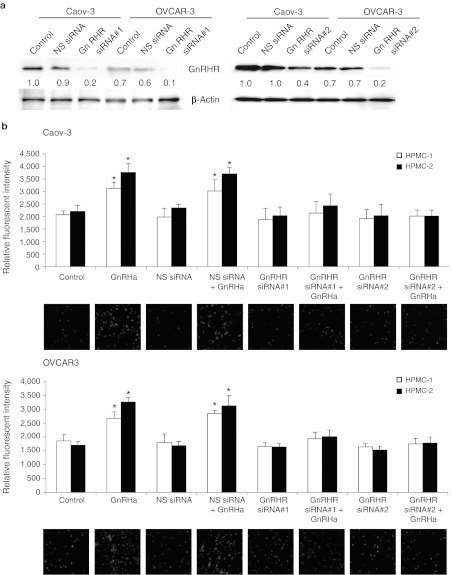

Inhibition of GnRH receptor in ovarian cancer cells reduces their adhesion to HPMCs

Because GnRH receptor is frequently overexpressed in ovarian cancer and that high GnRH receptor expression is associated with tumor progression, we sought to determine whether GnRH receptor inhibition is a feasible strategy for ovarian cancer treatment. For our analyses, we have utilized Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 cells, which are derived from serous adenocarcinomas and represent the clinically advanced human ovarian cancer.15 Our previous studies have also demonstrated GnRH receptor overexpression in these cells.11 To determine the effect of GnRH receptor on adhesion, Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 were infected with lentivirus expressing siRNA specifically engineered toward GnRH receptor, fluorescently labeled, and then plated on primary cultures of isolated human peritoneal mesothelial cells (HPMCs) removed from patients at surgery. The siRNA efficiently inhibited GnRH receptor protein (Figure 1a) and messenger RNA (data not shown), whereas a control virus expressing nonspecific siRNA had no effect (Figure 1a). This effective depletion of GnRH receptor was not altered in the absence as well as the presence of GnRH analogue (GnRHa) (Supplementary Figure S1), nor to cause alterations in cell morphology (Supplementary Figure S2). Importantly, there was a marked decrease (92–98% inhibition) in adhesion to HPMCs upon GnRHa stimulation between the control siRNA and GnRH receptor siRNA-treated cells (Figure 1b). A second GnRH receptor-specific siRNA was also used, and comparable results were obtained (Figure 1b), which confirms that GnRH receptor was responsible for this effect. Similar results were also observed in cells treated with cetrorelix, which is an antagonist of the GnRH receptor in the clinical arena (data not shown). Together, these data show that GnRH receptor has a critical role in adhesion to HPMCs.

Figure 1.

GnRH receptor (GnRHR) knockdown decreases adhesion of ovarian cancer cells to the mesothelium. (a) Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 cells were transduced with nonspecific (NS) or GnRHR siRNA. Cells were harvested and GnRHR expression was detected by western blotting. β-Actin was used to control for equal loading. Numbers below blots indicate quantification by densitometry for triplicate experiments. (b) NS or GnRHR siRNA-transduced cells were labeled with calcein-AM, plated onto 96-well plates coated with a monolayer of primary human peritoneal mesothelial cells (HPMCs), and incubated for 6 hours in the presence or absence of 0.1 nmol/l GnRHa. After nonadherent cells were removed, the number of adherent cells was quantified by measuring fluorescence intensity with a fluorescence spectrophotometer. Representative photographs were shown at low magnification. Data are mean values ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control. GnRHa, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

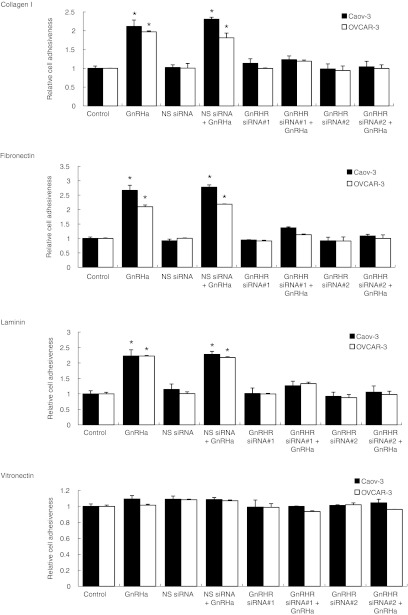

β1 integrin is important for GnRH receptor-mediated cell adhesion to HPMCs

The mesothelium lies on an ECM containing collagen, fibronectin, laminin, and vitronectin.16 To further demonstrate the effect of GnRH receptor in modulating adhesion, we have plated cells on different ECM components. As shown in Figure 2, Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 cells adhere preferentially on substrates of collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin, demonstrating a two- to threefold greater adhesion, whereas attachment to vitronectin was not affected. Adhesion to collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin was significantly inhibited by the GnRH receptor siRNA, whereas the nonspecific siRNA had no effect (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

GnRH receptor (GnRHR) siRNA decreases adhesion of ovarian cancer cells to ECM-coated wells. Nonspecific (NS) or GnRHR siRNA-transduced cells were plated onto 96-well plates coated with collagen I, fibronectin, laminin, and vitronectin, and incubated for 4 hours in the presence or absence of 0.1 nmol/l GnRHa. After nonadherent cells were removed, the number of adherent cells was quantified by staining with 0.5% crystal violet and measuring absorption at 630 nm. Data are mean values ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control. ECM, extracellular matrix; GnRHa, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

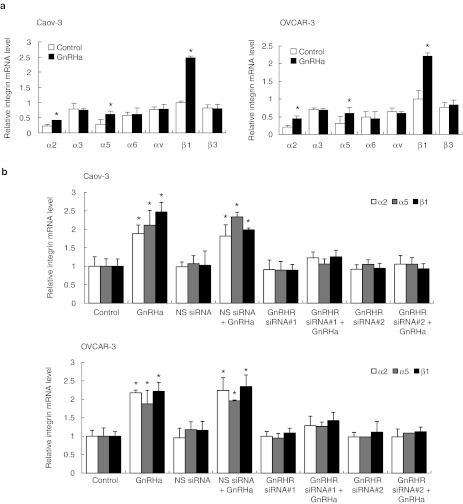

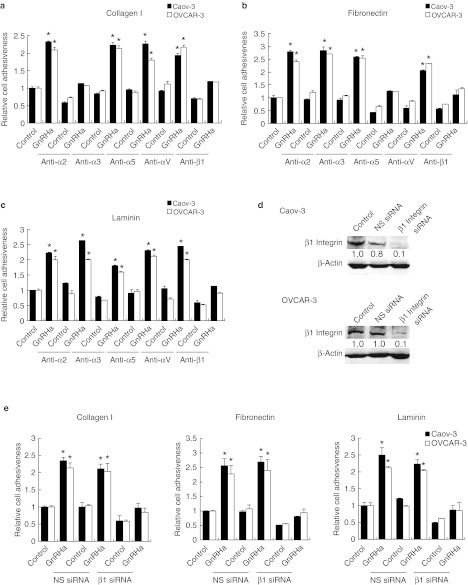

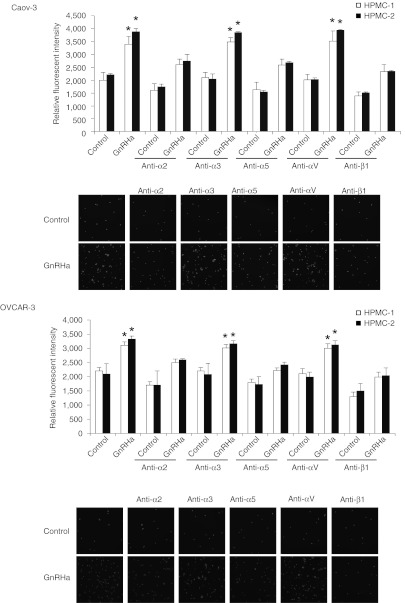

Cell adhesion to ECM is mediated by integrins, which are obligate heterodimers containing two distinct subunits, α and β.4 We tested the possibility that the GnRH receptor siRNA inhibits the expression of integrins by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Although several α- and β-integrins that mediate cellular binding to these ECM proteins were expressed on Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 cells, there was only a robust GnRHa-mediated increase in the expression of α2, α5, and β1 integrins (Figure 3a). The expression of α3, α6, αv, and β3 integrin subunits remained unchanged (Figure 3a). The inhibition of GnRH receptor also effectively reduced α2, α5, and β1 (Figure 3b), but not with α3, α6, αv, and β3 integrin expression (data not shown). The nonspecific siRNA had no effect (Figure 3b). Treatment of Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 cells with α2-, α5-, and β1-blocking antibodies, which bind to the extracellular domain on the membrane surface and prevent attachment to their respective ligands (α2β1 is a collagen receptor, α5β1 is a fibronectin receptor, and β1 is also a laminin receptor),17 substantially reduced adhesion of Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 cells to collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin to a similar degree as treatment with GnRH receptor siRNA (Figure 4a–c). β1 integrin-inhibiting antibodies reduced adhesion to collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin by 89%, α2 integrin-inhibiting antibodies decreased adhesion to collagen I by 98%, and α5 integrin-inhibiting antibodies impaired the adhesion to fibronectin by 94% (Figure 4a–c). No inhibition of collagen I, fibronectin, or laminin, binding was evident using antibodies against the α3 or αv integrin (Figure 4a–c). This was similar to the effect that β1 integrin siRNA had on these ECMs (Figure 4d,e). In addition, α2, α5, and β1 integrin-inhibiting antibodies or β1 integrin siRNA treatment of Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 also caused a substantial decrease in their adhesion to HPMCs (Figures 5 and 6), suggesting that inhibition of β1 integrin either by the use of antibodies or siRNA to inhibit its activity or expression results in the same reduction in adhesion, which gives further support that GnRH receptor mediates adhesion of ovarian cancer cells to the peritoneum by an α2β1 and α5β1 integrin mechanism.

Figure 3.

GnRH stimulates the expression of α2, α5, and β1 integrin. (a) Total RNA was extracted from Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 treated with 0.1 nmol/l GnRHa, reverse-transcribed, and amplified with α2, α3, α5, α6, αv, β1, and β3 integrin-specific primer. (b) Same assay as (shown in a) in cells transduced with nonspecific (NS) or GnRH receptor (GnRHR) siRNA. GAPDH was included as an internal control. Data are mean values ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GnRHa, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue; mRNA, messenger RNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

Figure 4.

Effect of inhibition of integrins on binding of ovarian cancer cells to different ECM components. Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 cells were preincubated with inhibiting antibodies to α2, α3, α5, αv, or β1 integrin plated onto 96-well plates coated with (a) collagen I, (b) fibronectin, or (c) laminin, and incubated for 4 hours in the presence or absence of 0.1 nmol/l GnRHa. (d) Nonspecific (NS) or β1 integrin siRNA-transduced cells were harvested and β1 integrin expression was detected by western blotting. β-Actin was used to control for equal loading. Numbers below blots indicate quantification by densitometry for triplicate experiments. (e) Cells were plated onto 96-well plates coated with collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin, and incubated for 4 hours in the presence or absence of 0.1 nmol/l GnRHa. After nonadherent cells were removed, the number of adherent cells was quantified by staining with 0.5% crystal violet and measuring absorption at 630 nm. Data are mean values ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control. ECM, extracellular matrix; GnRHa, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

Figure 5.

Effect of inhibition of integrins on binding of ovarian cancer cells to the mesothelium. Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 cells were preincubated with blocking antibodies to α2, α3, α5, αv, or β1 integrin, labeled with calcein-AM, plated onto 96-well plates coated with human peritoneal mesothelial cells (HPMCs), and incubated for 6 hours in the presence or absence of 0.1 nmol/l GnRHa. After nonadherent cells were removed, the number of adherent cells was quantified by measuring fluorescence intensity with a fluorescence spectrophotometer. Representative photographs were shown at low magnification. Data are mean values ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control. GnRHa, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue.

Figure 6.

β1 integrin siRNA decreases adhesion of ovarian cancer cells to the mesothelium. Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 cells were transduced with nonspecific (NS) or β1 integrin siRNA, labeled with calcein-AM, plated onto 96-well plates coated with human peritoneal mesothelial cells (HPMCs), and incubated for 6 hours in the presence or absence of 0.1 nmol/l GnRHa. After nonadherent cells were removed, the number of adherent cells was quantified by measuring fluorescence intensity with a fluorescence spectrophotometer. Representative photographs were shown at low magnification. Data are mean values ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control. GnRHa, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

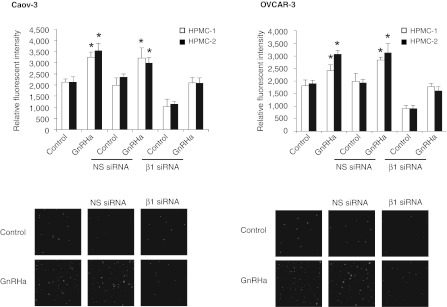

P-cadherin facilitates the adhesion of ovarian cancer cells with HPMCs

In addition to modulation of integrin expression levels, we also wanted to examine the contribution of cadherin activity toward adhesion. Our laboratory has previously demonstrated that treatment of cells with GnRHa resulted in specific increase in P-cadherin,12 and that P-cadherin was also expressed by the mesothelium (Figure 7a).18 We therefore determined whether P-cadherin inhibition also affects adhesion. A significant decrease in HPMC adhesion was observed in Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 cells pretreated with the P-cadherin–inhibiting antibodies (NCC-CAD-299), but not with the control IgG (Figure 7c). In contrast, blockade of E- and N-cadherin, which are also present on ovarian cancer cells and/or peritoneal mesothelial cells, did not produce any inhibition on the coculture (Figure 7c), indicating that the adhesion is ascribed to P-cadherin. The inhibition of P-cadherin using siRNA also inhibited the adhesion of both Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 cells to HPMCs to about the same level as did GnRH receptor siRNA (~90% inhibition) (Figure 7b,c), suggesting that P-cadherin is required for ovarian cancer cell and mesothelium interaction.

Figure 7.

Effect of inhibition of P-cadherin on peritoneal attachment. (a) Expression of P-, E-, and N-cadherin by Caov-3, OVCAR-3, and human peritoneal mesothelial cells (HPMCs) were evaluated by western blot analysis. β-Actin was used to control for equal loading. (b) Nonspecific (NS) or P-cadherin siRNA-transduced cells were harvested and P-cadherin expression was detected by western blotting. β-Actin was used to control for equal loading. Numbers below blots indicate quantification by densitometry for triplicate experiments. (c) Cells were preincubated with inhibiting antibodies to E-, N-, P-cadherin, or transduced with NS or P-cadherin siRNA, labeled with calcein-AM, plated onto 96-well plates coated with a monolayer of HPMCs, and incubated for 6 hours in the presence or absence of 0.1 nmol/l GnRHa. After nonadherent cells were removed, the number of adherent cells was quantified by measuring fluorescence intensity with a fluorescence spectrophotometer. Representative photographs were shown at low magnification. Data are mean values ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control. GnRHa, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

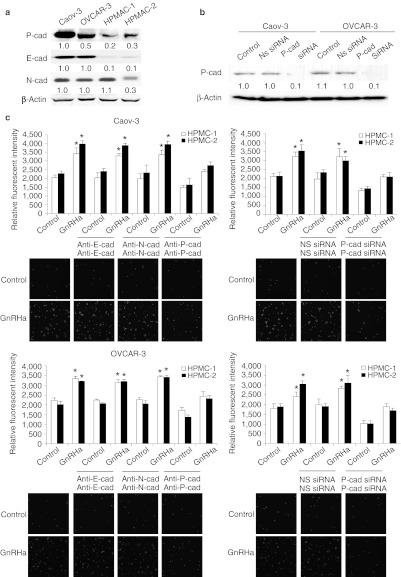

GnRH receptor and its associated signaling blockade inhibit tumor metastasis in vivo

Finally, we evaluated the efficacy of intraperitoneal injection of the GnRH receptor siRNA-expressing cells that emulates peritoneally disseminated ovarian carcinoma.19 As shown in Figure 8a, the tumor burden as gauged by ascites volume was significantly lower in mice injected with GnRH receptor siRNA compared with those in the nonspecific siRNA groups (P = 0.035). There was also a significant reduction in the number and the size of tumor nodules in the GnRH receptor siRNA-treated mice (P = 0.007) (Figure 8b). Likewise, the ascites volume and formation of tumor nodules were substantially decreased by β1 integrin and P-cadherin siRNA (P < 0.05) (Figure 8a,b). The tumor distribution resembled that of human ovarian cancer with multiple tumors on the mesenterium and small bowel (Figure 8c). Microscopic, invasive tumors were also observed on the omentum of control and nonspecific siRNA mice (Figure 8d). While there were fewer metastatic nodules in the GnRH receptor, β1 integrin, and P-cadherin siRNA-treated mice, the sizes of these nodules were similar as those found in the controls, suggesting that reduced metastasis is not due to impaired proliferation (Figure 8c). MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) staining showed no difference between injected control groups and the siRNA-treated tumor cells (Supplementary Figure S3). Western blot of tumor samples harvested from mice at the end of the study confirmed successful target gene knockdown of the targeted protein GnRH receptor and its downstream effectors, β1 integrin and P-cadherin (Figure 8e). These results suggest that GnRH receptor and its associated signaling may represent useful targets for the treatment of peritoneal dissemination in vivo.

Figure 8.

GnRH receptor (GnRHR) knockdown inhibits adhesion and intraperitoneal dissemination in vivo. Nude mice were intraperitoneally injected with Caov-3 cells transduced by nonspecific (NS), GnRHR, β1 integrin, or P-cadherin siRNA (three mice per group; 107 cells per mouse). (a) At autopsy, ascitic fluid was collected and measured. (b) The total number of metastases were excised and counted. (c) Representative views of the metastasis in the peritoneal cavity are shown, and arrows indicate tumor. (d) Histologic sections containing microscopic tumor nodules in the mouse omentum, bar = 100 µm. (e) Tumor samples harvested from mice were analyzed by western blot with the respective antibodies. Numbers below blots indicate quantification by densitometry for triplicate experiments. Data are mean values ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control. GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

Discussion

Peritoneal metastasis in ovarian cancer signals poor prognosis. However, despite the high prevalence and importance of this phenomenon, the underlying mechanisms remain largely uncharacterized. In this report, we provide new insights that RNA interference-mediated GnRH receptor silencing could result in significant and reproducible in vitro and in vivo binding to the mesothelial cells, indicating that GnRH receptor is a promising gene-targeting therapy for ovarian cancer metastasis.

In the present report, we identify the integrin receptors, in particular β1 integrin, in mediating GnRH-induced cell adhesion to the peritoneum. The nearly complete inhibition of adhesion by the inhibition of β1 integrin, coupled with a similar inhibition of α2 and α5 integrins, suggest preferential adhesion of ovarian carcinoma cells to collagen I, as well as significant adhesion to fibronectin are involved in this process.17 Indeed, collagen I is a major component of the submesothelial ECM.20,21 Furthermore, in the tumor tissue and peritoneal cavity, it has been reported that progressive ovarian carcinoma might induce a fibroproliferative response corresponded with an increase in interstitial collagen production,22 indicating that binding involving collagen I may represent an important early event unique to ovarian carcinoma peritoneal dissemination. We also included the hyaluronan receptor CD44 in our initial evaluation, but there was no noticeable effect (data not shown), which is consistent with its widespread distribution and its known ability to mediate several adhesion interactions.23 Similar results have also been reported earlier that the CD44-blocking antibody did not cause complete inhibition in either the in vitro or the in vivo studies, further suggesting that it is probable that some other cell surface molecules may be involved in the ovarian cancer cell adhesion to the mesothelium.24,25,26

The first step in ovarian cancer metastasis is adhesion to the mesothelial cells.27 The involvement of P-cadherin suggests that GnRH receptor might be involved in the early stages of cell adhesion. It also corroborates other findings, supporting the idea that P-cadherin is a distinct property of the malignant phenotype of ovarian cancer.28,29 P-cadherin is a predominant cadherin expressed in the peritoneum.18 Here, we provide direct evidence for the importance of this molecule in this implantation process. This observation also expands on those of our previous studies that have examined expression of P-cadherin in human ovarian cancer tissue, where an increase of P-cadherin expression is found in the metastatic adenocarcinoma as well as on omentum or peritoneum, suggesting that P-cadherin may mediate tumor–mesothelial cell interaction.13 The fact that cadherins are unique in their ability to mediate homophilic (between the same cadherins) as well as heterotypic (between two different cell types) interactions30,31 may also explain this predilection. In contrast to other tissues where loss of E-cadherin is a rate-limiting step in malignant progression, the majority of highly invasive and ascitic ovarian carcinomas rarely lose complete E-cadherin expression.28,32 Our finding that neither E- nor N-cadherin inhibition was capable of inhibiting mesothelial binding is consistent with these observations.

Successful adhesion is a prerequisite for peritoneal colonization. Once adhered, the cancer cells then invade into the peritoneum, leading to miliary dissemination. In addition to providing a physical link between ovarian cancer cells and peritoneal mesothelial cells, it is important to emphasize that both β1 integrin and P-cadherin may activate “outside-in signaling” to stimulate ovarian cancer cell motility and invasiveness.33,34 We have shown that the use of antibodies blocking the adhesive function of P-cadherin was able to inhibit its activation of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signaling and the subsequent cell migration and invasion.13 Moreover, although the integrin and cadherin adhesion systems have been presented here separately, this should not suggest that they act independently. There is evidence that integrins, like cadherins, associate with and control the action of receptor tyrosine kinases.35 Both systems can also interact with each other by their connections with the actin cytoskeleton, and some components from their cytoplasmic complexes, such as α-actinin, are shared and can be interchanged.36

Although several small-sized studies of GnRH receptor antagonists have shown certain efficacy, the clinical response to phase I/II trials in patients with late-stage, recurrent, chemotherapy-resistant ovarian tumors was less than expected.37,38 The data presented here demonstrating that GnRH receptor is important for adhesion may explain in part why GnRH receptor antagonists failed in the treatment of advanced or widely metastatic ovarian cancer. It is tempting to speculate that a GnRH receptor targeting approach may achieve the best results at inhibiting the progression of ovarian cancer at its early stage. These include ovarian carcinomas which are still confined to the ovary, but with the presence of malignant ascites or positive peritoneal washings. Alternatively, it may be used as a consolidation therapy after the optimal surgical debulking to delay the repopulation of residual microscopic tumor remnants in the peritoneal cavity. GnRHa are being investigated in clinical trials with mixed success at the levels of efficacy and toxicity.39 Therefore, seeking an effective and safe therapeutic method is crucial. In recent years, siRNA— a powerful gene-silencing technology with high efficiency and low toxicity— has been widely used for silencing malignant genes. The peritoneal dissemination of ovarian cancer may offer an advantage for gene transfer in that the therapeutic genes can be sensitive and specific to the target cells owing to the closed space of the peritoneal cavity.40

In summary, our results elucidate that GnRH receptor plays a critical role in one of the earliest steps that is adhesion toward ovarian cancer metastasis to the peritoneum. These results, together with our previous studies,11,12,13 suggest that GnRH receptor may function on multiple levels to promote dissemination of ovarian carcinoma cells (adhesion to mesothelial cells, and the subsequent increase in cell migration and invasion). These multifaceted roles offer the exciting possibility of GnRH receptor as a promising target for effective treatment of metastatic ovarian cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatments. Human ovarian cancer cell lines Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 were generous gifts from Dr Nelly Auersperg (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada). Cells were maintained in M199:MCDB105 (1:1) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT) with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. HPMCs were isolated from the omentum of consenting patients undergoing surgery for benign conditions by a method as described previously.41 The cells were cultured in M199 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, plus insulin (5 µg/ml), transferrin (5 µg/ml), hydrocortisone (0.4 µg/ml). For inhibition studies, cells were pretreated for 30 minutes at 37 °C with function-blocking antibodies before GnRH agonist (GnRHa; D-Ala6) (Sigma, St Louis, MO) stimulation. Function-blocking antibodies against α2 (clone P1E6), α3 (clone P1B5), α5 (clone P1D6), αv (clone AV1), β1 (clone JB1A) (10 µg/ml), and P-cadherin (NCC-CAD-299) (100 µg/ml) were from Chemicon (Chandlers Ford, UK), N-cadherin (GC4) (1:100) from Sigma, and E-cadherin (HECD-1) (200 µg/ml) from Zymed (San Francisco, CA). Nonspecific mouse IgG was used as a control. Every experiment was repeated at least two times in either duplicate or triplicate with different cell preparations to ensure consistency of the findings.

siRNA lentivirus transduction. High titers of lentiviruses carrying siRNAs that targeted the GnRH receptor (#1: 5′-CAAGAACAAUAUACCAAGA-3′ #2: 5′-CCAAUGGUAUGCUGGAGAGUU-3′), P-cadherin (5′-CAGCU CUGUUUAGCACUGAUA-3′), β1 integrin (5′-CCUGUUUACAAGGAG CUGAAA-3′), or nonspecific siRNA (5′-caacaagaUgaagagcaccaa-3′) were generated by cotransfection of HEK293T cells with the viral constructs and the lentiviral packaging mix (Sigma) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the lentiviral vector containing media were collected and filtered through 0.45 µm syringe filters. These particles were then used to transduce Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 (1 × 105 cells in 6-well plate) for 24 hours, and selected with 1 µg/ml puromycin (Invitrogen).

Reverse transcription and real-time PCR. Total RNA was extracted with the Trizol reagent, purified, and reverse-transcribed into cDNA with oligo-dT primers using the SuperScript II System (Invitrogen). cDNA was amplified using SYBR Green PCR master mix (Bio-Rad) in the iCycler iQ Real-Time detection system (Bio-Rad) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The sequence of the primers for α2 was, sense, 5′-GCGATGTAGGCTACCCTGCTTT-3′ and antisense, 5′-GAGAGACGCCTGATTCTGAAGG-3′ α3, sense, 5′-TGGG CAGATGGATGTGGATGAGAA-3′ and antisense, 5′-GATGATGATGG GGCGGAGTTTGTC-3′ α5, sense, 5′-GCTCGAGAGGATTGCAGA GA-3′ and antisense, 5′-GAGGGACTGTAAACCGAAGG-3′ α6, sense, 5′-CAAGATGGCTACCCAGATAT-3′ and antisense, 5′-CTGAATCTGA GAGGGAACCA-3′ αv, sense, 5′-GTTGGGAGATTAGACAGAGGA-3′ and antisense, 5′-CAAAACAGCCAGTAGCAACAA-3′ β1, sense, 5′-GA GGAA TGTTACACGGCTGCT-3′ and antisense, 5′-GGACAAGGTG AGCAATAGAAGG-3′ β3, sense, 5′-TGCCTCAACAATGAGGTCATCC CT-3′ and antisense, 5′-AGACACATTGACCACAGAGGCACT-3′. Specificity of each PCR was verified by melting curve analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis. The mean Ct of the integrin subunits was calculated and normalized with that of the internal control GAPDH (sense, 5′-CCTCCCGCTTCGCTCTCT-3′ and antisense, 5′-TGG CGACGCAAAAGAAGAT-3′). These experiments were carried out in triplicate and independently repeated three times.

Western blot analysis. Cells were collected in radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 50 mmol/l Tris-HCl; pH 7.4, 0.1% SDS, 150 mmol/l NaCl, and 5 mmol/l EDTA) plus protease inhibitors leupeptin, aprotonin, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and pepstatin A. Equal amounts of protein (40 µg) were loaded on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with different antibodies against P-cadherin (1:1,000) (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), integrin β1 (1:1,000) (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), and GnRH receptor (1:1,000) (Neomarkers, Fremont, CA). The immunocomplexes were captured by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad) and visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Images were quantified by using Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD). The blot was reprobed with anti-β–actin (Sigma) to confirm equal amounts of protein loading.

Cell adhesion to ECM components. 1 × 104 cells pretreated with GnRHa for 24 hours were placed in a 96-well culture plate, which had been precoated with collagen type I, fibronectin, laminin, or vitronectin (10 µg/ml) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). After 4 hours of incubation at 37 °C, nonadherent cells were removed by gentle washing. The number of adherent cells was quantified by staining the plates with 0.5% crystal violet and measuring absorption at 630 nm using a Bio-Rad microplate reader (Bio-Rad), and assays were performed in triplicate at least three times.

Cell adhesion to HPMCs. HPMCs were placed in a 96-well culture plate to form a monolayer culture. To the monolayer, a suspension of calcein-AM–labeled (5 µmol/l; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) Caov-3 and OVCAR-3 (2 × 104) cells were added, and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 6 hours. After the nonadherent cells were removed by gentle washing, the fluorescent intensity was measured in a CytoFluor fluorescence plate reader (Millipore, Bedford, MA) at an excitation wavelength of 494 nm and an emission wavelength of 517 nm. The fluorescence intensity was expressed in arbitrary units, and all values were corrected for background fluorescence (i.e., autofluorescence of HPMC monolayer alone). For the inhibition experiment, the cells were treated with antibodies against the α2, α5, or β1 integrin subunits or the equivalent control mouse IgG for 30 minutes before and during the adhesion assay. The experiment was carried out in triplicate and independently repeated three times.

In vivo intraperitoneal metastasis model. The experimental protocols were approved by the Committee on the Use of Live Animals in Teaching and Research of the University of Hong Kong. To assess tumorigenicity, Caov-3 cells (1 × 107) stably transduced with GnRH receptor, P-cadherin, or β1 integrin siRNA were injected intraperitoneally into 5–8 weeks old female nude athymic mice (BALB/c-u/nu; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) (n = 3 mice per group), and the experiment was conducted twice. The injected cells were >90% viable as assessed by trypan blue exclusion. Engrafted mice were inspected biweekly for signs of distress, weight changes, and ascites formation, and mice were killed by cervical dislocation when the tumor burden exceeded 10% of their body weight, and tumor burden was assessed by quantifying the volume of ascites with a pipette and counting the number of all visible (>0.1 cm) metastatic nodules in the peritoneal cavity. Paraffin-embedded tumor tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Statistical analysis. Results are presented as mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), and significance was determined using a t-test. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at a value of P < 0.05.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. GnRHa did not affect GnRH receptor knockdown. Figure S2. GnRH receptor siRNA did not alter cell morphology. Figure S3. Effect of GnRH receptor, β1 integrin, and P-cadherin knockdown on cell proliferation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Hong Kong Research Grant Council grant HKU778108. A.S.T.W. is a recipient of the Croucher Foundation Senior Research Fellowship. The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

GnRHa did not affect GnRH receptor knockdown.

GnRH receptor siRNA did not alter cell morphology.

Effect of GnRH receptor, β1 integrin, and P-cadherin knockdown on cell proliferation.

REFERENCES

- Siegel R, Naishadham D., and, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naora H., and, Montell DJ. Ovarian cancer metastasis: integrating insights from disparate model organisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:355–366. doi: 10.1038/nrc1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayantunde AA., and, Parsons SL. Pattern and prognostic factors in patients with malignant ascites: a retrospective study. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:945–949. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner MJ, Jones LM, Catterall JB., and, Turner GA. Expression of cell adhesion molecules on ovarian tumour cell lines and mesothelial cells, in relation to ovarian cancer metastasis. Cancer Lett. 1995;91:229–234. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03743-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey RC., and, Skubitz AP. CD44 and beta1 integrins mediate ovarian carcinoma cell migration toward extracellular matrix proteins. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2000;18:67–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1026519016213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmasri WM, Casagrande G, Hoskins E, Kimm D., and, Kohn EC. Cell adhesion in ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;149:297–318. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-98094-2_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidmaier R., and, Baumann P. ANTI-ADHESION evolves to a promising therapeutic concept in oncology. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:978–990. doi: 10.2174/092986708784049667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emons G, Pahwa GS, Brack C, Sturm R, Oberheuser F., and, Knuppen R. Gonadotropin releasing hormone binding sites in human epithelial ovarian carcinomata. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1989;25:215–221. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(89)90011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irmer G, Bürger C, Müller R, Ortmann O, Peter U, Kakar SS.et al. (1995Expression of the messenger RNAs for luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) and its receptor in human ovarian epithelial carcinoma Cancer Res 55817–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung LW, Leung PC., and, Wong AS. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone promotes ovarian cancer cell invasiveness through c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-mediated activation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10902–10910. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung LW, Leung PC., and, Wong AS. Cadherin switching and activation of p120 catenin signaling are mediators of gonadotropin-releasing hormone to promote tumor cell migration and invasion in ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:2427–2440. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung LW, Mak AS, Cheung AN, Ngan HY, Leung PC., and, Wong AS. P-cadherin cooperates with insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor to promote metastatic signaling of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in ovarian cancer via p120 catenin. Oncogene. 2011;30:2964–2974. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JM, Diedrich K., and, Ludwig M. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists: pharmacology and clinical use in women. Treat Endocrinol. 2002;1:281–291. doi: 10.2165/00024677-200201050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buick RN, Pullano R., and, Trent JM. Comparative properties of five human ovarian adenocarcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1985;45:3668–3676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed N, Riley C, Rice G., and, Quinn M. Role of integrin receptors for fibronectin, collagen and laminin in the regulation of ovarian carcinoma functions in response to a matrix microenvironment. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2005;22:391–402. doi: 10.1007/s10585-005-1262-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozer EC, Hughes PE., and, Loftus JC. Ligand binding and affinity modulation of integrins. Biochem Cell Biol. 1996;74:785–798. doi: 10.1139/o96-085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GT, Tai CT, Yeh LS, Yang TC., and, Tsai HD. Identification of the cadherin subtypes present in the human peritoneum and endometriotic lesions: potential role for P-cadherin in the development of endometriosis. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002;62:289–294. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw TJ, Senterman MK, Dawson K, Crane CA., and, Vanderhyden BC. Characterization of intraperitoneal, orthotopic, and metastatic xenograft models of human ovarian cancer. Mol Ther. 2004;10:1032–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey W., and, Amlot PL. Collagen production by human mesothelial cells in vitro. J Pathol. 1983;139:337–347. doi: 10.1002/path.1711390309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stylianou E, Jenner LA, Davies M, Coles GA., and, Williams JD. Isolation, culture and characterization of human peritoneal mesothelial cells. Kidney Int. 1990;37:1563–1570. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu GG, Risteli J, Puistola U, Kauppila A., and, Risteli L. Progressive ovarian carcinoma induces synthesis of type I and type III procollagens in the tumor tissue and peritoneal cavity. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5028–5032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneath RJ., and, Mangham DC. The normal structure and function of CD44 and its role in neoplasia. MP, Mol Pathol. 1998;51:191–200. doi: 10.1136/mp.51.4.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannistra SA, Kansas GS, Niloff J, DeFranzo B, Kim Y., and, Ottensmeier C. Binding of ovarian cancer cells to peritoneal mesothelium in vitro is partly mediated by CD44H. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3830–3838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel T, Swanson L., and, Cannistra SA. In vivo inhibition of CD44 limits intra-abdominal spread of a human ovarian cancer xenograft in nude mice: a novel role for CD44 in the process of peritoneal implantation. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1228–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessan K, Aguiar DJ, Oegema T, Siebenson L., and, Skubitz AP. CD44 and beta1 integrin mediate ovarian carcinoma cell adhesion to peritoneal mesothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1525–1537. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65406-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedbala MJ, Crickard K., and, Bernacki RJ. Interactions of human ovarian tumor cells with human mesothelial cells grown on extracellular matrix. An in vitro model system for studying tumor cell adhesion and invasion. Exp Cell Res. 1985;160:499–513. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(85)90197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AS, Maines-Bandiera SL, Rosen B, Wheelock MJ, Johnson KR, Leung PC.et al. (1999Constitutive and conditional cadherin expression in cultured human ovarian surface epithelium: influence of family history of ovarian cancer Int J Cancer 81180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel IS, Madan P, Getsios S, Bertrand MA., and, MacCalman CD. Cadherin switching in ovarian cancer progression. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:172–177. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeichi M. Morphogenetic roles of classic cadherins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:619–627. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbiner BM. Regulation of cadherin-mediated adhesion in morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:622–634. doi: 10.1038/nrm1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundfeldt K. Cell-cell adhesion in the normal ovary and ovarian tumors of epithelial origin; an exception to the rule. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;202:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(03)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczek-Thomas JA, Chen N., and, Hasan T. Integrin-mediated adhesion and signalling in ovarian cancer cells. Cell Signal. 1998;10:55–63. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(97)00074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung LW, Ip CK., and, Wong AS.2010Cadherin-catenin signaling in ovarian cancer progression Wu WS., and, Hu CT.eds). Signal Transduction in Cancer Metastasis Springer Life Sciences; pp. 225–253. [Google Scholar]

- Comoglio PM, Boccaccio C., and, Trusolino L. Interactions between growth factor receptors and adhesion molecules: breaking the rules. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:565–571. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B. Cytoskeleton-associated cell contacts. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1989;1:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(89)80045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verschraegen CF, Westphalen S, Hu W, Loyer E, Kudelka A, Völker P.et al. (2003Phase II study of cetrorelix, a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone antagonist in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer Gynecol Oncol 90552–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emons G, Gründker C, Günthert AR, Westphalen S, Kavanagh J., and, Verschraegen C. GnRH antagonists in the treatment of gynecological and breast cancers. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10:291–299. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh-Abady MM, Naderi-Manesh H, Alizadeh A, Shamsipour F, Balalaie S., and, Arabanian A. Anticancer activity of a new gonadotropin releasing hormone analogue. Biopolymers. 2010;94:292–297. doi: 10.1002/bip.21335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball KJ, Numnum TM, Rocconi RP., and, Alvarez RD. Gene therapy for ovarian cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2006;8:441–447. doi: 10.1007/s11912-006-0073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung S, Li FK., and, Chan TM. Peritoneal mesothelial cell culture and biology. Perit Dial Int. 2006;26:162–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

GnRHa did not affect GnRH receptor knockdown.

GnRH receptor siRNA did not alter cell morphology.

Effect of GnRH receptor, β1 integrin, and P-cadherin knockdown on cell proliferation.