Abstract

Model based dose finding designs such as the Continual Reassessment Method (CRM), rely on some basic working model. In the Bayesian setting, these take the form of “guess estimates” of the probabilities of toxicity at each level. In the Likelihood setting, these estimates simply take the form of a model since operational characteristics are una ected by arbitrary positive power transformations. These initial estimates are often referred to as the model skeleton. The impact of any prior distribution on the model parameter that describes the dose-toxicity curve will itself depend on the skeleton being used.

We study the interplay between prior assumptions and skeleton choice in the context of two-stage CRM designs. We consider the behavior of a two-stage design at the point of transition from a 3+3 design to CRM. We study how use can be made of stage 1 data to construct a more efficient skeleton in conjunction with any prior information through an example of a clinical trial. We evaluate to what extent stage 1 data might be down weighted when the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) is far away from the starting level and stage 1 data is strongly informative. The results show no improvement in accuracy thus weighting is not necessary, unless the investigators feel strongly about the location of the MTD and wish to accelerate into the vicinity of the MTD. In general, since this information is not available we recommend that the design of two stage trials utilize stage 1 data to establish a skeleton.

1 Introduction

Two stage Phase I designs have received increased attention from clinicians in academic centers [1], the pharmaceutical industry [2] and regulatory agencies such as Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in recent years [3]. Two stage designs are defined as a combination of a rule based design when escalation is based on some clinical rule, usually one constructed by the clinicians, and then at some point when we have observed one or more dose limiting toxicities (DLT), we switch to a model based dose escalation algorithm. For the first stage there is no model and statistical considerations are elementary or absent. During this stage, although information on intermediary grades can be used [4], a first stage based on 3+3 inclusions has a feature attractive to some clinicians in that it looks exactly like the standard design until the first toxicity is observed, at which time a model based design such as the Continual Reassessment Method (CRM) sequential allocation and estimation cycle kick in. This allows for great flexibility for the following clinical and statistical considerations:

Heterogeneity among the responses is required in order for the likelihood estimation to have a unique solution not on the boundary of the parameter space.

The first DLT should be an indication that we are in the vicinity of the MTD and thus the first stage enables us to eliminate low, sub therapeutic levels by experimenting through those low levels fast.

The first stage can also reduce a problem of testing many levels, say 10, to a more manageable set of levels, for example six, where the modeling and estimation have been studied extensively and known to be stable. When the first DLT occurs or we think we are in the vicinity of the MTD we can embark on the modeling stage, where all levels are included in the algorithm. Since model based designs such as CRM have been shown to converge to the location of the MTD fast [5, 6] then we ensure most patients are being treated at or near the MTD.

The question we explore in this paper is how can we use the data obtained from the first stage to build a more efficient skeleton and an informative, if only weakly informative, prior and how can the first stage information help us to improve upon the original design that uses a vague prior? Since modeling does not start until the second stage then the modeling parameters such as the initial toxicity rates (skeleton values) assigned to each level and the prior distribution can be defined at the end of first stage. The algorithms for model based designs are rigid once you have selected a model and priors, but the dose assignment and the procedure itself is adaptive and it is flexible through some tuning parameters which can reflect the current knowledge at the start of the second stage. One can argue that the information obtained from the first stage can be the basis to form both an informative skeleton as well as an informative prior distribution which of course will eventually have smaller influence as the data from stage 2 accumulates.

One approach would be to view the number of patients treated and the observed toxicities as toxicity rates from a retrospective analysis at the end of first stage since patients have not been assigned to doses as part of a model based dose finding algorithm. As such, we should use the information obtained in these observed toxicity rates but adjust it such that the information is not too restrictive in terms of the remaining untested levels where patients have not yet been treated. Another approach would be to build an informative prior with the investigators’ input on within trial performance and after evaluating the method’s operating characteristics.

If for example 18 patients have been treated at dose 1 to 6, and the first 3 patients have no toxicities at dose level 6, this is likely indicative of the MTD being at higher levels, in which case a prior to encourage more rapid escalation beyond the current level might be used. If, on the other hand, the clinician wishes to discourage too rapid an escalation, then a prior that assigns greater weights at the dose levels near the occurrence of the first DLT would slow down subsequent escalation. In this way we would encourage more experimentation in the neighborhood of the first observed DLT so that, when the true MTD is in this same neighborhood, we could anticipate an improvement in performance. The investigator’s response would determine the method’s behavior. Based on the operating characteristics and the accumulated data from the first stage the statistical and clinical team can decide how strong the prior should be. Here, our aim is to utilize the information from stage 1 data while ensuring that stage 1 data are not too dominant during the subsequent modeling stage and, in particular, at the point of transition from rule to model based escalation. We assess the impact of stage 1 data in particular cases where the first stage included too many patients treated at levels that they would not have been treated under CRM, and provide several weighting schemes that could potentially down weight stage 1 data. **** A possible reason to down weight stage 1 data can be when investigators have strong prior data from other studies or earlier formulations of the drug that indicate the location of the MTD and they might want to accelerate into the vicinity of the MTD. Whitehead and Williamson [7] illustrate how pseudo-observations can serve as the prior in Bayesian dose finding studies. In the context of two stage designs, the likelihood from stage 1 data can form the prior in the Bayesian approach where the contributions from stage 1 patients can be possibly down weighted. We compare various approaches that weight stage 1 data differently both in the bayesian and likelihood framework. In addition, we weight the first stage data through the use of an informative prior, while making sure the prior is not so strong that it controls the model based algorithm in stage 2.

We compare these results with a likelihood CRM that either uses the full or reduced data from the first stage. We also compared the results with Bayesian single stage CRM using a non-informative skeleton and vague prior.

2 Methods

2.1 Two stage designs

A general presentation of the models in use is given in O’Quigley and Iasonos [8]. The focus of this paper is on two stage designs where the first stage is based on 3+3 inclusion until we observe heterogeneity among the responses, i.e., at least one toxicity and one non-toxicity. Following that, the model can be fit and parameter estimation can be carried out. Using the usual notation in this field, we assume the trial consists of k ordered dose levels, d1, d2,…,dk, and a total of N patients. The visited dose level for patient j is denoted as xj, and the binary toxicity outcome is denoted as yj, where yj= 1 indicates a dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) for patient j, and 0 indicates absence of a DLT. O’Quigley and Shen used a one-parameter working model for the dose toxicity relation of the form, , where a ∈ (0, ∞) is the unknown parameter, and αi are the standardized units representing the discrete dose levels di. Since drugs are assumed to be more toxic at higher dose levels, ψ(di, a) is an increasing function of di. The parameter estimate can be obtained through a Bayesian framework [5] or maximum likelihood estimation [6]. In the likelihood approach, the heterogeneity among the responses guarantees a unique solution to the likelihood equation. The standardized units αi representing each dose level have a different interpretation within the Bayesian or likelihood approach. In the Bayesian setting, the αi correspond to best point guesses of the probability of toxicity at each level. In the likelihood setting, with no prior, the αi describe a class of invariant models up to any arbitrary power transform, i.e., another set of, say , where for any r > 0 produces a model with identical operating characteristics. In either case we simply refer to the αi as the skeleton. Once the current estimate of is calculated, the MTD is defined to be the dose d0 ∈ {d1,…, dk} such that some distance measure is minimized. The choice of measure can give greater weight to the lower of two doses on either side of the running estimate. Here we use the simplest distance; . The parameter θ is a pre-specified acceptable probability of toxicity (also known as the target rate).

It has been shown that two stage CRM is not necessarily coherent at the transition point from stage 1 to stage 2 [9]. In order to respect the coherence principle, in practice we can use a provision where we do not allow a patient to be treated at a higher level than a patient who had a DLT. We have compared two stage CRM designs in the context of different stage 1 designs where the coherence provision was not met [4] and showed that restricting escalation after the occurrence of a DLT does not compromise the performance of the method. Such a provision is often followed in real trials in order to escalate conservatively. The focus of this paper is the investigation of the prior and skeleton interplay and how it can potentially influence two stage designs at the transition point. In order to be able to isolate the combined and joint effects of the prior and skeleton from the principle that ensures coherence, we evaluated designs without making an appeal to the coherence provision.

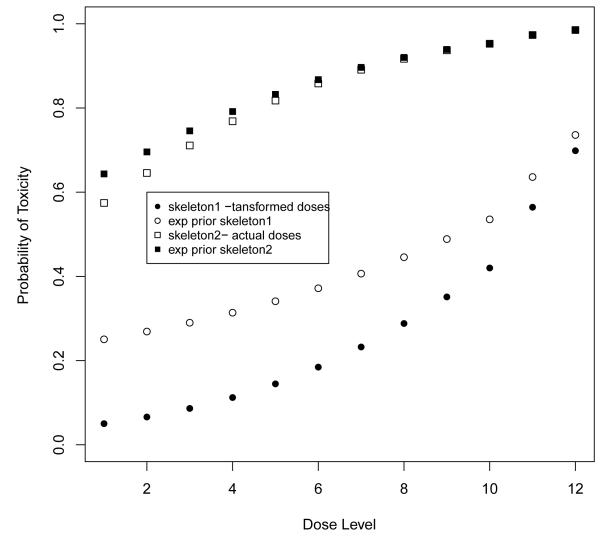

The CRM relies on some basic conditions on the underlying model structure for the algorithm to proceed efficiently [5]. Several papers show the CRM to be robust and efficient as long as reasonable skeletons are used [10, 11, 12]. Reasonable skeletons are defined by the spacing among adjacent levels, not the actual values themselves. To reflect the uncertainty in our initial probability estimates, we often assume a non-informative prior on the parameter a. The prior assumptions in bayesian phase I designs have been studied extensively in the past and it is generally recommended to use a vague prior [13] unless data from a complete study can be used to form some informative prior [14]. However, it can be seen that the skeleton and the prior itself are confounded. In the original paper on the CRM [5], it was argued that the simple exponential prior would work well in the simple situation of 6 dose levels. This was roughly true although, while such a prior was close to non-informative at 5 of the levels, it was slightly informative against the highest level making this level (when the MTD) a little more difficult to attain. Moller [15] kept this same exponential prior with a skeleton which corresponded to a transformed amount of the actual dose. According to this distribution, the recommended MTD prior to the experiment was level 10. Since the target toxicity rate was high, 40%, this choice amounted to roughly putting a very strong and concentrated prior on levels 8 and above, chosen from a total of 12 levels (Figure 1). Before any experimentation the prior alone indicated the MTD to be level 10. It was no surprise that an initial observation of a non-toxicity at the lowest level was followed by a recommendation to treat again at level 10. The reason for this large escalation is because the prior, for the given skeleton, was assigning a low probability of toxicity at the lower levels while the probability associated with high levels was too high. Specifically, the probability that level 4 was too safe, i.e., < 40% was 0.66 and for level 6 < 30% was 0.49 based on exponential prior. Given this prior, low levels should not be considered since their probabilities of toxicity are too low and higher levels should be tried out given the target rate of 0.4. The solution was to use a more vague prior with respect to this particular chosen skeleton such as normal distribution with a larger variance. Or, alternatively, to keep the exponential prior but to transform the administered dose values into a skeleton with higher values at the lowest dose levels.

Figure 1.

The skeletons and expected value of probability of toxicity at each level given the exponential prior used in Moller’s example (reference [14]).

As a result, for a given prior, certain skeletons will be non-informative while others will be informative. Herein, we define an informative skeleton a skeleton that, given a true dose-toxicity curve, tends to recommend one or more levels more than other levels [16]. If for example, the skeleton is conservative favoring lower doses then the method might not escalate as rapidly when observing non toxicities, whereas in the other extreme case, if the skeleton is too flat favoring higher doses, then the method might allow much larger jumps in dose escalation than what is considered clinically acceptable. Since there is no modeling involved in the first stage, the question we address in the following sections is how can we construct a weakly informative skeleton and an informative prior at the beginning of the second stage that utilizes the observed data from the first stage.

2.2 Informative skeleton

If we still use the interpretation of a skeleton as the initial assumed probabilities of toxicity at each level then it is natural to use the observed toxicity rates as the skeleton values at the visited levels. However, clinical practice tells us that it is not uncommon to have observed rates equal to zero [17] resulting from the 3+3 since it tends to experiment at low dose levels [1, 18, 19]. In fact since the first stage ends at the occurrence of the first DLT, we can only observe 0/3 or 1/3 DLTs per dose, assuming patients are accrued 3 at a time. In order to fit retrospectively a dose-toxicity curve on these low observed rates that resulted from a non CRM design, for example the 3+3 design, a constrained maximum likelihood estimation was proposed [17]. The observed rates are hence modified based on constraints that take into account the prior knowledge of the investigators in terms of the expected increase in toxicity probabilities among adjacent doses. The target rate at the MTD, the number of visited levels in relation to the total number of dose levels in the trial also determine the constraints that control the minimum and maximum allowed increase in toxicity rates among adjacent levels. We denote the minimum and maximum increase as δmin and δmax. The choice of how much should the estimated rates increase, i.e., the values of the constraints, should be based on some clinical information from studies outside the one we analyze, but when such information is lacking a value of θ/k would imply that we enforce a slowly increasing curve that has not reached its target rate by the kth dose level which will have an estimated toxicity rate less than θ. If we assume that the first DLT is observed at the expected MTD or at the vicinity of the MTD then that level should be the one closer to the target rate. For example assume the target rate, θ is 0.25 and there are k = 10 dose levels in the trial, that the first DLT is at level six, then δmin = θ/(k – 3) = 0.036 and δmax = 1/(k – 1) = 0.11. If the observed rates are equal to 0/3, 0/3, 0/3, 0/3, 0/3, 1/3 at the six first levels respectively, then the estimated toxicity rates based on the retrospective analysis are 0.00001, 0.0357, 0.0714, 0.1072, 0.1429, 0.2540 respectively (refer to the Appendix for details). This estimation technique takes into account the number of subjects treated and the number of observed toxicities at each level separately, while imposing the increase to be at least 0.04 so that the estimated rates are strictly increasing with dose. For more details regarding the choice of the constraints and the constrained estimation refer to the discussion in [17].

2.3 Weighted Likelihood

In the context of sequential likelihood estimation, O’Quigley and Shen [6] first introduced the necessity of an initial first stage since the likelihood equation fails to have a solution on the interior of the parameter space unless some heterogeneity in the responses has been observed. They showed that the operating characteristics of CRM appear relatively insensitive to the choice of any initial, reasonable scheme. At the beginning of second stage the log likelihood is non-monotonic and has a unique maximum. Here we extend the likelihood approach of [6] by weighting the likelihood at the transition point from stage 1 to stage 2 such that contributions from stage 1 are weighted differently. We express the likelihood in terms of contributions from different dose levels instead of contributions from individual patients [20], and we weight the contributions to the likelihood from the dose levels and patients treated at the first stage only. Once the second stage initiates, patients contribute to the likelihood one at a time without any weighting scheme, or equivalently with weight equal to 1. Specifically, let j = N1, N2 be the the sample sizes from stage 1, and 2 respectively, N = N1 + N2 be the total sample size and k* ≤ k be the visited dose levels in stage 1. The derivative of log Likelihood expressed in terms of dose levels di at the end of stage 1, assuming N1 patients have been treated, can be expressed as:

| (1) |

where ni(N1), ti(N1) are the number of patients treated and the number of DLTs respectively at each dose level i out of a total of N1 patients.

The derivative of log Likelihood expressed in terms of contributions from patients accrued in stage 2, i.e the sample starts from N1 + 1 to N, is given by:

| (2) |

Summing the above two expressions, which are derivatives of log-likelihoods and multiplying the first stage likelihood by weights (w1, …wk*) would result to the following expression (score) which is set equal to zero in order to find at each sequential step after each inclusion in stage 2.

| (3) |

If each wi < 1 such that then these weights become much smaller as we add new patients with weight equal to 1. If instead we use wi that are not smaller than 1 and replace wi with vi where then will change sequentially after each patient is added and eventually as N2 increases relative to N1 then the final weight vi at level i will be equal to wi + ni(N2)/N2 where ni(N2) are the number of patients allocated to level i out of N2 patients. Since the contributions to the log likelihood from stage 2 are non-zero, the second stage data will eventually dominate. It can be shown (refer to Appendix A.2) that the minimum value of the log likelihood from stage 2 data is N2 log ψxk** if ψxk** ≤ 0.5 or N2 log(1–ψxk** > 0.5 where k**, 1 < k** < k is the lowest visited dose level in stage 2. Let’s assume for simplicity that ψxk** ≤ 0.5. After we have completed the first stage and we have the value of the log likelihood from stage 1, denoted as LN1, we would need to include a minimum of LN1/log(ψxk**) patients in the second stage in order to have at least as much information as the information provided by stage 1 data.

2.4 Informative prior

Another approach to down weight the information from stage 1, would be to use an informative prior so that specific dose levels are weighted differently. Through a prior distribution we can impose different weights to the low levels or patients treated far away from the vicinity of the MTD which will correspond to levels included at the beginning of the first stage. This can be achieved by partitioning the parameter space for a into ki intervals that correspond to each dose level based on a pre-specified skeleton and then assign a discrete uniform prior distribution in each subinterval. Depending on how far away the level is from the MTD, then the corresponding weight will be smaller, whereas levels around the MTD, which here is assumed to be the level with the first occurrence of a DLT, will be assigned a larger weight. O’Quigley [13] and Cheung and Chappell [21] showed how to obtain the constants ki such that we can write the interval of [A,B] as a union of non overlapping intervals whereby where S1 = [A, k1), S2 = [k1, k2),…,Sk = [kk–1, B]

For each 1 ≤ i ≤ k – 1 there exists a unique constant ki such that θ –ψ (xi, ki) = ψ(xi+1, ki) – > 0.

For example, for and the skeleton values corresponding to 10 dose levels given by α = (0.00001, 0.0357, 0.0714, 0.1072, 0.1429, 0.2540, 0.3, 0.4, 0.55, 0.7), the interval [0,5] can be written with the following partition: S1 = [0, 0.246), S2 = [0.246, 0.469), S3 = [0.469, 0.572), S4 = [0.572, 0.666), S5 = [0.666, 0.854), S6 = [0.854, 1.080), S7 = [1.080, 1.325), S8 = [1.325, 1.89), S9 = [1.89, 3.043), S10 = [3.043, 5]. This partition enables the construction of an informative prior by assigning a different weight on each segment. Contrary, a vague prior would be a piecewise uniform so that the probability associated with each interval is just 1/k. The weighting scheme we evaluated for Bayesian CRM consists of weights of approximately 1/3 around the dose where the first DLT occurred, and almost 0 elsewhere. We denote the weights that determine the prior distribution as wP.

3 Illustration

As an illustrative example we present a trial that is currently open for accrual at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) and it follows the two stage CRM design as described below. The trial was designed to test k = 10 dose levels, where the first stage would accrue one patient per dose level and it would escalate to the next level until the first DLT is observed or dose level 6 is reached which ever occurs first. At the first DLT or level 6 dose escalation will proceed based on CRM. The investigators believed that the MTD will be between dose level 6 and 8 based on the MTD obtained in dogs, but they had a strong desire to have very few patients treated at dose level 9 and 10 since they were not sure whether those levels could be potentially too toxic. Based on this information, we evaluated several skeletons and models and decided that the following skeleton provides adequate operating characteristics under several scenarios when the MTD is above or below where we expect it to be, which we denote as α0. = (0.05, 0.08, 0.1, 0.12, 0.2, .25, 0.3, 0.4, 0.55, 0.7).

The FDA requested that the first stage should not include single patient cohorts but instead escalate in cohorts of 3 patients until the first occurrence of DLT or when dose level 6 is reached. After this point dose escalation will proceed with CRM. Since we expect to have 18 patients treated from stage 1, with the majority of patients having no DLTs (17/18), the aim was to evaluate the impact of the first stage data on the modeling stage. We present an application of the methods presented above for this example. The parameters that describe this trial are: 3 patients were accrued at 6 dose levels during stage 1 resulting in 0/3 in all levels, except dose 6 where 1/3 DLTs was observed. The sample size is 18 from stage 1, the target rate is 0.25 and the working model was the power model . The skeleton values were replaced with the ones derived in section 2.2 for the visited levels where data were observed. The values of the skeleton for the remaining four levels were the original values used to design the trial resulting to skeleton values equal to α1. = (0.00001, 0.0357, 0.0714, 0.1072, 0.1429, 0.2540, 0.30, 0.40, 0.55, 0.70). At the transition point from stage 1 to 2, four methods were compared in terms of the estimated dose-toxicity curve and dose recommendation:

CRML: Likelihood CRM with the information from all 18 patients from stage 1

CRMLn=6: Likelihood CRM with reduced information from 6 patients from stage 1, ie only patients treated at nearby levels, such as dose 5 and 6 are included

CRMLw: Weighted likelihood CRM as described in section 2.3.

CRMBw: Bayesian CRM where the prior distribution is stepwise discrete uniform in the respective dose levels intervals, obtained from the partition described in section 2.4

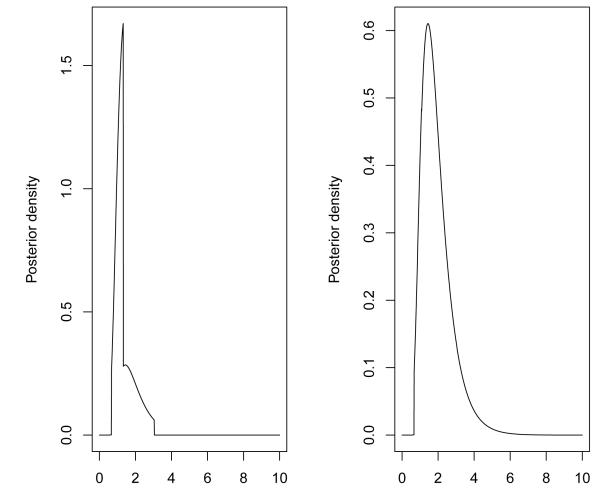

For the weighted likelihood CRM (CRMLw), and weighted Bayesian CRM (CRMBw), various weighting schemes were evaluated but for the sake of brevity we present two weighting schemes for each method respectively. The weights for the visited dose levels from stage 1, when using the likelihood approach, are given by wL, whereas the weights for the informative prior are given by wP (Table 1). A programming code for weighted CRM, and for setting an informative prior can be provided by the first author. Figure 2 shows the posterior density after we have multiplied the likelihood with the weighted prior using weights equal to wP1 and wP2. We can see how different weights a ect the likelihood and posterior density respectively. Table 2 shows the estimated and the resulting probabilities of toxicities estimated by each method at the end of stage 1. The weighted likelihood method used the following weights for stage 1 data: wL1 = (0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4) and wL3 = (0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 4). We see that different weighting schemes can result in a more conservative dose escalation while higher weights assigned to lower dose levels push the method to a more aggressive escalation. Depending on the investigators knowledge from pre-clinical data regarding the risk associated with each level, we can impose these weights such that the dose escalation method can behave accordingly.

Table 1.

Weighting schemes when stage 1 data are fixed

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose Levels | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| wL 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | ||||

| wL 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| wL 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | ||||

| wP 1 | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.297 | 0.300 | 0.300 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0 |

| wP 2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.166 | 0.170 | 0.166 | 0.166 | 0.166 | 0.16 |

Figure 2.

Posterior density for the illustrative example of Section 3 at the point of transition from stage 1 to 2 using weights wP1 and wP2 for left and right panel respectively.

Table 2.

Predicted toxicity rates at each dose level di the end of stage 1 data, when using various weighting schemes. The weighted likelihood approach uses wL1 and wL3.

| Method | Score (1) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRML | 2.319 | 1.438 | 0 | 0.008 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.42 | 0.60 |

| CRML n=6 | 0.535 | 1.165 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 0.66 |

| CRML wL 1 | 0.198 | 1.145 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.66 |

| CRML wL 3 | 0.197 | 1.018 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.39 | 0.54 | 0.70 |

| CRMBwP1 | NA | 1.349 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.45 | 0.62 |

| CRMBwP2 | NA | 1.897 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 0.51 |

Score (1) is the value of the score function evaluated at a = 1 at the end of stage 1

4 Simulation study

This section presents a simulation study that evaluates different weighting schemes of stage 1 data obtained from a two stage design, where the first stage is a rule based design and the second stage is model based design such as CRM. We compared the methods described in section 3 which weight stage 1 data in different ways. Specifically, one can use the likelihood CRM without any weighting but discard stage 1 data obtained from low doses, or alternatively the data can be included in the estimation process but with different weights on the contributions to the respective likelihood.

All methods were compared to a two-stage CRM design without any weighting and full use of stage 1 data. First we consider the case where stage 1 data are fixed. We evaluated two cases of stage 1 data resulting from the 3+3: when the first DLT occurs at level 3 (data not shown) or when it occurs at level 6. In the latter case, stage 1 data consist of 18 patients as in the example of the previous section. The weighting schemes that we evaluated (Table 1) were meant to down weight the information from the first stage, with the assumption that if the first stage consisted of 18 patients being tested at 6 levels, then some of these levels are far from the location of the MTD and should have little influence on estimation. Following the same parameters as in Section 3, the study simulated the responses of the patients accrued in the second stage and compared the percent of trials out of 1000 simulated trials that recommended the correct MTD. Several true toxicity rates were evaluated. We restricted dose escalation to one level for all methods. The target rate is 0.25 in all scenarios and the sample size in stage 2 is 22 additional patients (ie N = 18 + 22 ).

Table 3 shows the proportion of trials selecting each dose level using various weighting schemes across four methods when the MTD is among levels 4-9. We can see that across scenarios the weights wL1 lead to a conservative dose escalation by favoring low levels, while on the other hand wL2 improve the method’s performance compared to CRM with the full data, but the increase is very small and not applicable when the MTD is among the highest level. Weighting the data via the prior distribution, instead of the likelihood seems to improve performance slightly as shown in scenario 3 and 4 using wP1, or in scenario 5 and 6 using wP2. Note, that any improvement below 4% is within twice the standard error of these estimates and thus is not meaningful. The weights’ influence on estimation depends on the data obtained from stage 2, which here depend on the true toxicity rates that the simulated data are based on. Hence the weights can become less or more influential depending on the spacing of the levels and the sample size in stage 2 relative to stage 1. When the MTD turns out to be among the levels that we already considered “too low”, i.e., the tested levels from stage 1, then the weighted likelihood performs as good as the non-weighted estimation, but the weighted Bayesian CRM is 7% less accurate than the likelihood when the weights favor higher levels as the MTD such as (wP2). The weights presented here are constant across scenarios, however different scenarios would result to different patient to dose allocation and to a different number of toxicities per level. That is why, the final weights at dose levels tested in stage 1 are the weights we have assigned plus ni(N2)/N2 for patients with toxicities and (ni(N2) – ti(N2))/N2 for patients included with no toxicities. Thus the influence of the weights is not deterministic but rather depends on subsequent inclusions and the number of subsequent toxicities and non-toxicities at the same level.

Table 3.

Proportion of trials selecting each dose level using various weighting schemes when stage 1 data are fixed. The weights w1 and w2 correspond to wL1 and wL2 as given in Table 1. Parenthesis shows Standard Error at the MTD.

| Levels | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True rates: S1 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| CRML | 0.001 | 0.1 | 0.32 (0.01) | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.01 | ||||

| CRML n=6 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.40 (0.02) | 0.30 | 0.1 | 0.00 | ||||

| CRML w 1 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.36 (0.02) | 0.27 | 0.04 | 0.00 | ||||

| CRML w 2 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.37 (0.02) | 0.39 | 0.11 | 0.00 | ||||

| CRMBwP1 | 0.10 | 0.31 (0.01) | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.00 | |||||

| CRMBwP2 | 0.10 | 0.29 (0.01) | 0.42 | 0.20 | 0.00 | |||||

| True rates: S2 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| CRML | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.45 (0.02) | 0.40 | 0.07 | 0.01 | ||||

| CRML n=6 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.49 (0.02) | 0.27 | 0.03 | 0.00 | |||

| CRML w 1 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.49 (0.02) | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.00 | |||

| CRML w 2 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.49 (0.02) | 0.36 | 0.04 | 0.00 | ||||

| CRMBwP1 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.40 (0.02) | 0.51 | 0.00 | |||||

| CRMBwP2 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.38 (0.02) | 0.43 | 0.10 | 0.02 | ||||

| True rates: S3 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| CRML | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.56 (0.02) | 0.29 | 0.05 | |||||

| CRML n=6 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.52 (0.02) | 0.21 | 0.03 | ||||

| CRML w 1 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.47 (0.02) | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.00 | ||

| CRML w 2 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.60 (0.02) | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.00 | ||||

| CRMBwP1 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.70 (0.01) | 0.22 | 0.01 | |||||

| CRMBwP2 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.51 (0.02) | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.00 | ||||

| True rates: S4 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.1 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.4 | 0.45 | 0.5 |

| CRML | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.54 (0.02) | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.00 | |||

| CRML n=6 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.48 (0.02) | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.00 | ||

| CRML w1 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.40 (0.02) | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.00 | |

| CRML w2 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.54 (0.02) | 0.19 | 0.00 | ||||

| CRMBwP1 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.57 (0.02) | 0.110 | 0.010 | |||||

| CRMBwP2 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.45 (0.02) | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.00 | ||||

| True rates: S5 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.1 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| CRML | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.61 (0.02) | 0.15 | 0.00 | ||||

| CRML n=6 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.56 (0.02) | 0.11 | 0.00 | |||

| CRML w1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.51 (0.02) | 0.17 | 0.01 | |

| CRML w2 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.60 (0.02) | 0.03 | |||||

| CRMBwP1 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.41 (0.02) | 0.11 | ||||||

| CRMBwP2 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.62 (0.02) | 0.23 | 0.00 | ||||

| True rates: S6 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.1 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.4 |

| CRML | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.43 | 0.51 (0.02) | 0.02 | |||||

| CRML n=6 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.44 | 0.43 (0.02) | 0.01 | |||

| CRML w1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 0.52 (0.02) | 0.08 | ||

| CRML w2 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.64 | 0.21 (0.01) | |||||

| CRMBwP1 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.39 | 0.44 (0.02) | ||||||

| CRMBwP2 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.29 | 0.65 (0.02) | 0.04 |

We also considered the case where stage 1 data are not fixed, but rather follow escalation in cohorts of 3 patients and hence each simulated trial represents a different realization of the 3+3 depending on the true underlying toxicity rates presented above. In this case, the weights are not fixed but change depending on the level where the first DLT occurred and where stage 1 ended. For the likelihood approach, we assigned similar weights as above, ie the last dose from stage 1 is assigned a weight of 0.4 or 2 denoted as w1 and w2 respectively, and the level below is assigned a weight of 0.2 and 2 respectively and all remaining levels are assigned a small weight under w1 scheme or zero weight under w2 scheme. For the Bayesian approach, we assigned a weight equal to 0.14 at the 7 levels around the occurrence of first DLT (3 below and 3 levels above if possible) and the remaining levels get a weight of 0.006; this scheme is denoted as wP1. The second scheme wP2 mimics the idea of equal weighting to the remaining untested levels although the actual value of the weights depends on the location of the occurrence of the first DLT. The total sample size is fixed at 40 for comparison across scenarios. Tables 4 and 5 show the proportion of trials selecting each level and the percentage of patients treated at each level. The results show that the weighting schemes do not offer any advantages over the standard two stage CRM, but certain weights can offer a 10% advantage in accuracy when the MTD is among the higher levels. As a reference, we also present simulations with single stage Bayesian CRM with the power model , with N(0,2) as the prior distribution for a (Table 6). Accuracy is a few percentage points higher (ranges from 0 to 12% improvement) with Bayesian CRM compared to two stage CRM, but the gains are apparent in patient to dose allocation especially if the MTD turns out to be among the highest levels (13% versus 31%). Using cohorts of 3 patients during stage 1 is not the most efficient way to get to the vicinity of the MTD and many patients will end up being treated at low dose levels. Alternatively, use of information on intermediary grades can speed up escalation in the first stage [4].

Table 4.

Proportion of trials selecting each dose level using various weighting schemes when stage 1 data are simulated. Weights vary depending on the location of first DLT. Standard error for all estimates is bounded by 2%.

| Levels | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True rates: S1 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.90 |

| CRML | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.20 | 0.01 | ||||

| CRML w1 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.00 | |||

| CRML w2 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.15 | 0.01 | ||||

| CRMBwP1 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| CRMBwP2 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| True rates: S2 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.80 |

| CRML | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.52 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.00 | ||

| CRML w1 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.00 | ||

| CRML w2 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.54 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.00 | ||

| CRMBwP1 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.48 | 0.28 | 0.04 | 0.01 | ||

| CRMBwP2 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.41 | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| True rates: S3 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 |

| CRML | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.53 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.00 | |

| CRML w1 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.48 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.00 | |

| CRML w2 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.00 | |

| CRMBwP1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.54 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.01 | |

| CRMBwP2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.51 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.01 | |

| True rates: S4 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.50 |

| CRML | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 0.14 | 0.01 | |

| CRML w1 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| CRML w2 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.07 | 0.01 | |

| CRMBwP1 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| CRMBwP2 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| True rates: S5 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.50 |

| CRML | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.45 | 0.12 | 0.00 |

| CRML w1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.02 |

| CRML w2 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.05 | |

| CRMBwP1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.49 | 0.17 | 0.01 |

| CRMBwP2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.51 | 0.15 | 0.01 |

| True rates: S6 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 |

| CRML | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.07 | ||

| CRML w1 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.10 | |||

| CRML w2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.03 | |

| CRMBwP1 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.11 | |||

| CRMBwP2 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.11 |

Table 5.

Percentage of patients treated using methods with various weighting schemes when stage 1 data are simulated. Weights vary depending on the location of first DLT.

| Levels | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| True rates: S1 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.90 |

| CRML | 20.9 | 15.6 | 20.1 | 22.7 | 16.2 | 3.7 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 |

| CRML w1 | 17.1 | 18.1 | 23.4 | 22.3 | 14.7 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 |

| CRML w2 | 24.4 | 15.7 | 21.5 | 22.7 | 13.6 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRMBwP1 | 16.3 | 13.6 | 19.7 | 23.3 | 18.4 | 6.6 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 |

| CRMBwP2 | 16.3 | 13.5 | 19.2 | 20.7 | 15.2 | 9 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| True rates: S2 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.80 |

| CRML | 8.9 | 11.4 | 11.5 | 16.6 | 31.3 | 15.9 | 3.7 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 |

| CRML w1 | 8.6 | 11.9 | 14.1 | 18.1 | 28.8 | 13.7 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0 |

| CRML w2 | 10 | 12.6 | 13.3 | 19.6 | 32.5 | 10.3 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 |

| CRMBwP1 | 8.1 | 9.2 | 10.1 | 14.5 | 29.6 | 20.4 | 6 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 0 |

| CRMBwP2 | 8.1 | 9.2 | 10 | 13.8 | 24.6 | 22.4 | 7.8 | 3.8 | 0.4 | 0 |

| True rates: S3 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 |

| CRML | 8.7 | 9.6 | 8.6 | 9 | 19.9 | 26.8 | 13.4 | 3.7 | 0.3 | 0 |

| CRML w1 | 8.2 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 10.3 | 21 | 25.1 | 11.9 | 3.9 | 0.5 | 0 |

| CRML w2 | 9.7 | 10.4 | 9.4 | 11.3 | 26.1 | 24.1 | 7.3 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 0 |

| CRMBwP1 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 16.5 | 27.6 | 16.2 | 6.4 | 1.1 | 0 |

| CRMBwP2 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 7.6 | 7.9 | 14.4 | 27.6 | 15.4 | 9.5 | 1.2 | 0 |

| True rates: S4 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.50 |

| CRML | 16.6 | 11.2 | 8 | 7.1 | 12.1 | 17 | 17.9 | 8.9 | 1.1 | 0.1 |

| CRML w1 | 12.9 | 10.9 | 8.9 | 8 | 12.2 | 17.2 | 18 | 10.2 | 1.8 | 0.1 |

| CRML w2 | 19.8 | 10.3 | 8.7 | 9 | 16.6 | 18 | 13.1 | 4 | 0.4 | 0 |

| CRMBwP1 | 12.7 | 11.1 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 10.8 | 16.1 | 19.3 | 11.6 | 2.8 | 0.3 |

| CRMBwP2 | 12.7 | 11.1 | 7.8 | 7.1 | 8.7 | 15.8 | 19.4 | 14.1 | 3 | 0.3 |

| True rates: S5 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.50 |

| CRML | 8.7 | 9.8 | 8.3 | 7.7 | 11.2 | 12.7 | 16.3 | 19.2 | 5.8 | 0.2 |

| CRML w1 | 8.2 | 9.1 | 8.4 | 7.4 | 9.8 | 12.3 | 15.5 | 21.1 | 7.5 | 0.8 |

| CRML w2 | 9.8 | 10.4 | 9.2 | 9.1 | 15.6 | 16.8 | 15 | 11.9 | 2.3 | 0.1 |

| CRMBwP1 | 8 | 8.5 | 7.6 | 7.1 | 10.5 | 12.5 | 15.5 | 20.9 | 8.3 | 1.2 |

| CRMBwP2 | 8 | 8.5 | 7.6 | 6.9 | 8.5 | 11 | 15.6 | 23.9 | 8.8 | 1.2 |

| True rates: S6 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 |

| CRML | 7.6 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 7.3 | 8.5 | 10.7 | 13.4 | 21.4 | 13.2 | 2.4 |

| CRML w1 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 8.2 | 7.5 | 8 | 8.9 | 10.9 | 20 | 16.8 | 4.3 |

| CRML w2 | 7.8 | 8 | 8 | 8.1 | 12.8 | 15.7 | 15.1 | 16.8 | 6.6 | 1.2 |

| CRMBwP1 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 7.8 | 11.6 | 12 | 19.3 | 15 | 4.6 |

| CRMBwP2 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.4 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 10.5 | 22.3 | 18.2 | 4.8 |

Table 6.

Proportion of trials selecting each dose level using single stage Bayesian CRM (Percentage of patients treated). Skeleton 1 and Skeleton 2 are α1. and α2. defined in Section 3 and 4 respectively.

| Levels | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| True rates: S1 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.90 |

| Skeleton 1 | 4.6 (9.4) | 6.0 (12.7) | 27 (23.9) | 43.7 (28.5) | 18.0 (19.2) | 0.7 (4.6) | 0 (1.3) | 0 (0.4) | 0 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| Skeleton 2 | 0.3 (6.0) | 2.6 (9.6) | 26.3 (25.2) | 56.8 (38.2) | 13.6 (16.1) | 0.4 (3.7) | 0 (1.0) | 0 (0.2) | 0 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| True rates: S2 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.80 |

| Skeleton 1 | 0.1 (3.4) | 1.0 (6.6) | 4.0 (9.6) | 21.9 (19.2) | 57.4 (37.5) | 15.0 (16.9) | 0.5 (4.5) | 0.1 (1.7) | 0 (0.5) | 0 (0.1) |

| Skeleton 2 | 0.0 (3.4) | 0.6 (4.8) | 2.2 (9.2) | 27.0 (24.7) | 56.0 (37.3) | 13.7 (15.2) | 0.5 (3.9) | 0.0 (1.1) | 0 (0.3) | |

| True rates: S3 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 |

| Skeleton 1 | 0.1 (3.2) | 0.2 (4.6) | 0.8 (5) | 2.7 (7.1) | 26.8 (23.2) | 53.3 (34.6) | 14.8 (15.2) | 1.3 (5.5) | 0 (1.4) | 0 (0.4) |

| Skeleton 2 | 0.0 (3.0) | 0.0 (3.6) | 0.5 (5.4) | 4.1 (10.6) | 27.6 (24.7) | 55.4 (34.9) | 11.6 (13.6) | 0.8 (3.2) | 0 (1) | 0 (0.1) |

| True rates: S4 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.50 |

| Skeleton 1 | 2 (6.7) | 2.3 (6.4) | 1.2 (4.8) | 2.6 (5.5) | 7.4 (10.6) | 24.6 (21.0) | 43.5 (25.7) | 14.7 (14) | 1.5 (3.9) | 0.2 (1.3) |

| Skeleton 2 | 0 (4.3) | 0.7 (4.9) | 1.2 (6.8) | 4.6 (10.0) | 12.7 (13.0) | 27.1 (21.2) | 44.4 (27.4) | 8.2 (9.2) | 1.0 (2.6) | 0.1 (0.7) |

| True rates: S5 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.50 |

| Skeleton 1 | 0.1 (3.2) | 0.2 (4.5) | 0.8 (4.1) | 0.5 (4.6) | 3.5 (8.2) | 8.2 (11.0) | 21.8 (17.5) | 53.4 (31.9) | 11.1 (12.3) | 0.4 (2.9) |

| Skeleton 2 | 0.0 (3.0) | 0.0 (3.6) | 0.5 (4.9) | 1.2 (7.1) | 6.8 (10.4) | 13 (13.3) | 27.5 (21.2) | 44.5 (26.5) | 6.1 (8.7) | 0.4 (1.4) |

| True rates: S6 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.40 |

| Skeleton 1 | 0 (2.6) | 0 (3.1) | 0.1 (3.3) | 0.2 (3.8) | 0.8 (5.7) | 2.7 (7.7) | 7.9 (9.5) | 29.5 (22.6) | 50 (30.9) | 8.8 (11.1) |

| Skeleton 2 | 0 (2.6) | 0 (2.9) | 0.1 (3.6) | 0.4 (5.0) | 2.2 (7.7) | 7.2 (10.3) | 15 (13.3) | 31.4 (23.4) | 39.3 (24.9) | 4.4 (6.4) |

Finally, we compared the performance of two stage designs under different skeletons in order to assess the effect of the skeleton on the operating characteristics. The choice of skeleton is arbitrary in general, but here we attempted to divide the probability (0,1) space into “equal increments”. We used the arcsin() transformation to divide the spacing among adjacent levels equally. Specifically, we set α2,1 = 0.05 and α2,10 = 0.9 and the increment between adjacent levels was set equal to on the transformed scale. In the probability scale the skeleton is equal to 0.05, 0.11, 0.19, 0.29, 0.40, 0.51, 0.62, 0.73, 0.82, 0.90, for the 10 levels respectively and is denoted as α2.. The results are shown in Table 6. When the MTD is among the lower levels, α2. shows higher accuracy and the reverse is true when the true MTD is among the higher levels both in the single stage CRM (Table 6) and two stage CRM (Supplemental Table 1).

5 Conclusion

In general, it is possible to find some weighting scheme that can modify the performance of CRM enabling some of the higher levels to be attained more quickly. There can be situations, resulting from rule based designs, in which many patients have been treated at lower dose levels, so that the dose escalation at the point of transition from the rule based stage to the modeling stage may not be optimal. This issue is only applicable at the point of transition, until the second stage data dominates and the influence of those early observations becomes smaller which is in agreement with previous work that evaluated the influence of early toxic responses [22, 23].

We evaluated cases where the first stage data might be too informative because of too many tested levels and can be down weighted but, in general, depending on the true toxicity scenario, there is not much improvement over the basic design across many scenarios unless we have a strong idea of where the MTD is (plus or minus a level). The simulations showed no improvement in accuracy since an increase in the range of 4% falls within twice the standard error of the estimates based on 1000 simulations. Another example is when the starting dose is too low relative to the MTD, an issue that is often the case in practice [24]. Two stage designs are useful in such settings because they can reach the vicinity of the MTD faster [25, 8].

How can previous studies be used?

Su [2] suggested to estimate the prior’s variance from the information provided from stage 1 data which can also be useful in certain cases, however depending on the amount of data provided by stage 1, this variance might be too large and the prior too strong or too weak relative to the first stage data which would a ect how fast the method reaches higher dose levels. Satoshi et al. [26] provide guidelines on the effective sample size (ESS) by estimating the prior’s influence in terms of number of patients and they recommend to have an ESS ≤ 0.1 × n where n can be the number of patients from a previous completed study or from stage 1. The motivation behind two stage designs is that stage 1 would provide us with an empirical (data-based) prior before we initiate model fit in the second stage. Alternatively, if data from a completed study are available we can develop a prior using that data to guide us through stage 1, and at the end of stage 1, the posterior distribution can be the prior distribution of the second stage. Data from the completed study can be used to inform the prior distribution either by fitting a curve to the data [20, 17, 27], or by using the data to estimate the parameters of a parametric distribution (variance). Another approach is to use existing data to inform the choice of skeleton values either by fitting a retrospective CRM, isotonic regression or any other parametric model. However, Phase I trials test very few levels with a small number of patients, and as a result the challenge of model fit of Phase I data has inherent limitations [17]. Our recommendation is to use a reasonable skeleton since it was shown that one-parameter CRM is robust given a different model parameterization [10]. Reasonable skeletons can be obtained based on achieving some desirable operating characteristics [11] or based on dividing the (0,1) space approximately equally among the levels ensuring that the spacing between any adjacent levels is not narrow. This is simple in the case of 6 levels and it can become more challenging when more than 10 levels are being tested. In this paper we illustrated how to assign weights on levels directly by partitioning the parameter space into corresponding dose levels and assigning discrete uniform prior which can be informative in each sub-interval/segment. Data from a completed study or clinicians’ knowledge about the toxicity profile of the drug can be incorporated in the prior distribution through this weighting scheme.

There are no cases where the method behaved less well than simply using the original CRM with the information from the first stage as obtained and without any kind of weighting. We recommend that the above weighting schemes be considered as a fine tuning device when the investigators want to control the within trial performance at the initiation of the second stage of a two-stage design, based on stronger current (prior) knowledge regarding the location of the MTD.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1 : Proportion of trials selecting each dose level using various weighting schemes when stage 1 data are simulated using Skeleton 2, denoted as α2.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the reviewers and Associate Editor for the valuable feedback and suggestions that have strengthened the overall presentation of the paper. Funding: Partial support for this research was provided by National Cancer Institute (Grant Number 1R01CA142859).

Appendix.

A.1 A dose-toxicity curve from a trial that had followed the 3+3 design can be estimated retrospectively based on the observed toxicity rates ti/ni at each dose i by using constrained maximum likelihood estimation as follows. We define the increment in toxicity rate between adjacent levels as πi = pi – pi–1, 2 ≤ i ≤ k where pi is the probability of toxicity at di and π1 = p1 and thus . The estimated toxicity rates maximize the binomial log-likelihood

| (4) |

under the constraints that δmin ≤ πi ≤ δmax, i = 2, …, k, π1 ≥ 0 and .

Appendix.

A.2 Assume ψ(di, a) is the working model and for simplicity we denote it as ψxi. The contributions to the likelihood, denoted as L from stage 2 data, ie N2 patients are given by

Since log(ψxj) < log(1 – ψxj) if 0 < ψxj < 0.5 and log(1 – ψxj) < log(ψxj) if 0.5 < ψxj < 1 then the minimum value of the log LN2 from stage 2 contributions expressed as a function of k dose levels is

where ni(N2) are the number of patients allocated to level i out of N2 patients, thus and I is an indicator function taking the value of 1 if the expression is true or 0 otherwise. Since ψxi is monotonic and increasing with di then the min log L occurs when all N2 patients from stage 2 are treated at the lowest dose among stage 2 levels, denoted as k**, 1 < k** < k. Thus the min log L equals N2logψxk** if ψxk** ≤ 0.5 or N2 log(1 – ψxk**) if ψxk** > 0.5.

References

- 1.Iasonos A, Wilton AS, Riedel ER, Seshan VE, Spriggs DR. A comprehensive comparison of the continual reassessment method to the standard 3 + 3 dose escalation scheme in Phase I dose-finding studies. Clinical Trials. 2008;5:465–77. doi: 10.1177/1740774508096474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su Z. A two-stage algorithm for designing phase I cancer clinical trials for two new molecular entities. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2010 Jan;31(1):105–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.10.004. Epub 2009 Oct 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Tourneau C, Lee JJ, Siu LL. Dose escalation methods in phase I cancer clinical trials. Journal of National Cancer Institute. 2009 May 20;101(10):708–20. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iasonos A, Zohar S, O’Quigley J. Incorporating lower grade toxicity information into dose finding designsClinical Trials. Clinical Trials. 2011;8:370379. doi: 10.1177/1740774511410732. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Quigley J, Pepe M, Fisher L. Continual reassessment method: a practical design for phase 1 clinical trials in cancer. Biometrics. 1990;46:33–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Quigley J, Shen LZ. Continual reassessment method: a likelihood approach. Biometrics. 1996;52:673–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitehead J, Williamson D. Bayesian decision procedures based on logistic regression models for dose-finding studies. Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics. 1998;8:445–467. doi: 10.1080/10543409808835252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Quigley J, Iasonos A. In: Handbook of statistics in clinical oncology. Crowley John, Ankerst Donna Pauler., editors. CRC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung YK. Coherence principles in dose-finding studies. Biometrika. 2005;92:863–873. [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Quigley J, Zohar S. Retrospective robustness of the continual reassessment method. Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics. 2010;20(5):1013–25. doi: 10.1080/10543400903315732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SM, Cheung YK. Model calibration in the continual reassessment method. Clinical Trials. 2009 Jun;6(3):227–38. doi: 10.1177/1740774509105076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daimon S, Zohar S, O’Quigley J. Posterior maximization and averaging for Bayesian working model choice in the continual reassessment method. Statistics in Medicine. 2011 Jun 15;30(13):1563–73. doi: 10.1002/sim.4054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Quigley J. Theoretical study of the continual reassessment method. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 2006;136:1765–1780. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morita S, Thall PF, Mller P. Determining the effective sample size of a parametric prior. Biometrics. 2008 Jun;64(2):595–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00888.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moller S. An extension of the continual reassessment methods using a preliminary up-and down desigh in a dose findings study in cancer patients, in order to investigate a greater range of doses. Statistics in Medicine. 1995;14(9):911–922. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin G, Yuan Y. Bayesian model averaging continual reassessment method in phase I clinical trials. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2009;104(487):954–968. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iasonos A, Ostrovnaya I. Estimating the dose-toxicity curve in completed phase I studies. Statistics in Medicine. 2011 Jul 30;30(17):2117–29. doi: 10.1002/sim.4206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Quigley J, Zohar S. Experimental designs for phase I and phase I/II dose-finding studies. British Journal of Cancer. 2006;94:609–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He W, Liu J, Binkowitz B, Quan H. A model-based approach in the estimation of the maximum tolerated dose in phase I cancer clinical trials. Statistics in Medicine. 2006 Jun 30;25(12):2027–42. doi: 10.1002/sim.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Quigley J. Retrospective analysis of sequential dose-finding designs. Biometrics. 2005 Sep;61(3):749–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheung YK, Chappell R. A simple technique to evaluate model sensitivity in the continual reassessment method. Biometrics. 2002 Sep;58(3):671–4. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2002.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Resche-Rigon M, Zohar S, Chevret S. Adaptive designs for dose-finding in non-cancer phase II trials: influence of early unexpected outcomes. Clinical Trials. 2008;5(6):595–606. doi: 10.1177/1740774508098788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Resche-Rigon M, Sarah Zohar, Chevret Sylvie. Maximum-Relevance Weighted Likelihood Estimator: Application to the Continual Reassessment Method. Statistics and Its Interface. 2010;Vol 3(No 2):177–184. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Tourneau C, Stathis A, Vidal L, Moore MJ, Siu LL. Choice of starting dose for molecularly targeted agents evaluated in first-in-human phase I cancer clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010 Mar 10;28(8):1401–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9606. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zohar S, Chevret S. Phase I (or phase II) dose-ranging clinical trials: proposal of a two-stage Bayesian design. Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics. 2003 Feb;13(1):87–101. doi: 10.1081/BIP-120017728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morita S, Thall P, Muller P. Evaluating the impact of prior assumptions in bayesian biostatistics. Statistics in Biosciences. 2010 Jul 1;2(1):1–17. doi: 10.1007/s12561-010-9018-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ivanova A, Flournoy N. Comparison of Isotonic Designs for Dose-Finding. Statistics in Biopharmaceutical Research. 2009;1:101–107. doi: 10.1198/sbr.2009.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1 : Proportion of trials selecting each dose level using various weighting schemes when stage 1 data are simulated using Skeleton 2, denoted as α2.