Abstract

Background

Breast cancer surveillance is important for women with a known history of breast cancer. However, relatively little is known about the prevalence and determinants of adherence to surveillance procedures, including associations with seeking of cancer-related information from medical and nonmedical sources.

Methods

We conducted a longitudinal cohort study of breast cancer patients diagnosed in Pennsylvania in 2005. Our main analyses included 352 women who were eligible for surveillance and participated in both baseline (approximately one year after cancer diagnosis) and follow-up surveys. Outcomes were self-reported doctor visits and physical examination, mammography, and breast self-examination (BSE) at one-year follow-up.

Results

Most women underwent two or more physical examinations according to recommended guidelines (85%). For mammography, 56% of women were adherent (one mammogram in a year) while 39% reported possible over-utilization (two or more mammograms). About 60% of respondents reported regular BSE (five or more times in a year). Controlling for potential confounders, higher levels of cancer-related information seeking from nonmedical sources at baseline was associated with regular BSE (OR=1.52, 95% CI=1.01 to 2.29, p=0.046). There was no significant association between information seeking behaviors from medical or nonmedical sources and surveillance with physical examination or mammography.

Conclusions

Seeking cancer related information from nonmedical sources is associated with regular BSE, a surveillance behavior that is not consistently recommended by professional organizations.

Impact

Findings from this study will inform clinicians on the contribution of active information seeking toward breast cancer survivors’ adherence to different surveillance behaviors.

Keywords: Information seeking, breast cancer, post-treatment surveillance, breast self-examination, mammography, clinical examination

INTRODUCTION

Based on recent estimates, there are over 2.6 million women alive in the United States who have a history of breast cancer (1). With a rapidly aging population, increased detection of early stage tumors, and improved treatment procedures, the population of breast cancer survivors is projected to grow even further. Improvements in diagnostic technologies and treatment delivery make breast cancer surveillance following womens’ initial cancer treatment even more essential.

Given the increased risk of second cancers in breast cancer survivors, routine surveillance is important for diagnosing early local recurrences and second primary breast tumors. Considerable evidence supports routine surveillance through regular physician examination and screening mammography (2–9); both are recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), and other national or international professional agencies (10–17). In contrast, evidence supporting breast self-examinations (BSE) is absent. Thus far, no controlled trials have demonstrated improved patient survival with BSE surveillance. Accordingly, only a handful of advisory organizations provide guidance about BSE for breast cancer surveillance (11, 12, 18).

Research suggests that many breast cancer survivors do not receive mammography and clinical examination as recommended or perform BSE (19–22). One survey found only about 60% of breast cancer survivors underwent surveillance mammography in the first year after their treatment, with fewer doing so in the second year after treatment and beyond (21). Adherence to surveillance mammography and clinical examination is lower among women of older age, ethnic minorities, women suffering from comorbid conditions, and those who underwent certain types of treatment (19–21, 23–26). However, relatively little attention has been paid to potentially modifiable factors that may influence breast cancer surveillance adherence, including the level of cancer-related information seeking.

Cancer patients are interested in obtaining information about a variety of topics related to their disease and from a multitude of sources (27–29). While health professionals are the key information source for most cancer survivors, nonmedical information sources including interpersonal contacts (e.g., family members, friends, support groups) and media sources (e.g., printed materials such as books, brochures, magazines and newspapers and other forms of mass media such as TV, radio and internet) play an increasingly important role for cancer patients (27). Active seeking of cancer-related information from medical and nonmedical sources have been linked to various patient behaviors and health outcomes. For instance, studies report patients’ active seeking of cancer-related information is associated with utilization of targeted therapy, treatment decision satisfaction, nutrition behaviors, patient-reported quality-of-life, and emotional well-being (30–35). Given this background, we analyzed longitudinal survey data from a population sample of breast cancer survivors to determine the associations between information seeking from medical and nonmedical sources measured at baseline and subsequent breast cancer surveillance.

METHODS

Study Population and Procedure

This analysis was part of a larger study involving a randomly selected sample of 2,013 patients diagnosed with breast, prostate, or colorectal cancers between January 2005 and December 2005, as reported to the Pennsylvania Cancer Registry. The larger study aimed to examine the influence of cancer patients’ information-seeking behaviors on a variety of health behaviors and outcomes. We included participants who were diagnosed with breast cancer in the current analyses. The baseline survey was conducted in September 2006 with a follow-up survey in September 2007. We oversampled cancer patients with Stage IV disease and African-American patients to facilitate planned subgroup analyses (not part of this present study). Further details are described elsewhere (36).

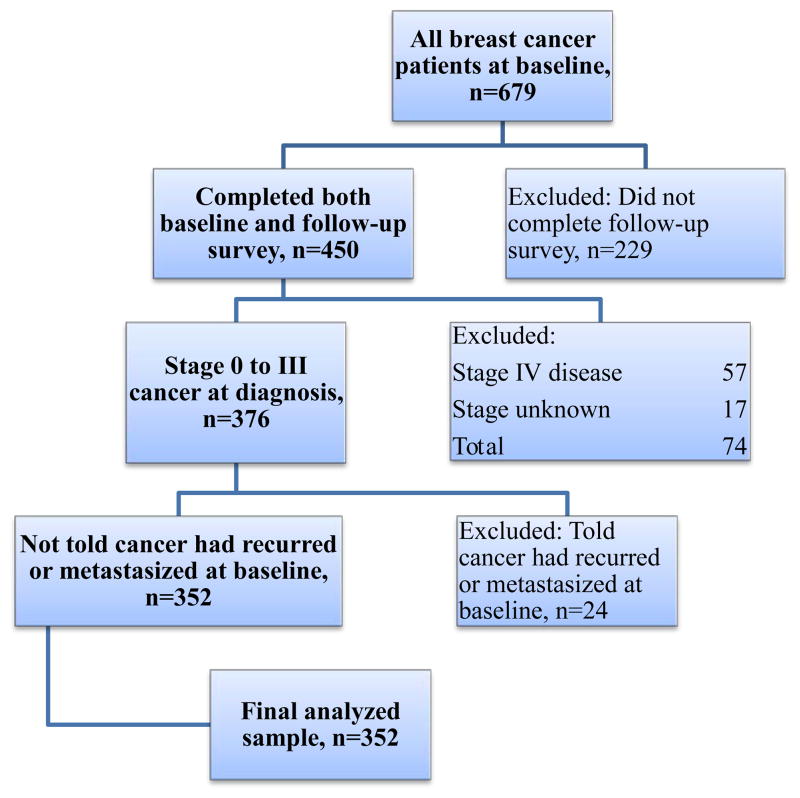

Of 679 patients diagnosed with breast cancer at baseline, 450 completed the follow-up survey. The response rate for participants with breast cancer at baseline was 68% (American Association for Public Opinion Research response rate 4) (37). At follow-up, the raw response rate among those who agreed to be re-contacted was 79%. We excluded patients who did not complete the second survey (n=229), those with metastatic disease as they were not eligible for surveillance testing (n=81), and those with unknown cancer stage (n=17), leaving 352 patients in the analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection criteria for analysis

We developed the survey questionnaire following a literature review, expert consultation, and a pilot study involving in-depth interviews among 43 patients diagnosed with breast, prostate, or colorectal cancer in the greater Philadelphia area (38). Participants in the pilot study were not part of the longitudinal survey. Data collection was based on Dillman’s tailored design method for mail surveys (39). First, we mailed notice letters to sampled participants to inform them about the study objectives and instructions for opting out. Next, participants received the survey, a small monetary incentive (either $3 or $5 at baseline and $3 at follow-up), and stamped return envelopes. Participants who did not opt out or return the survey within two weeks were sent an additional letter and survey. The instructions for completing the survey indicated that participation was voluntary and submitting a completed questionnaire implied informed consent. The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board approved the study procedure and materials.

Outcome Measures – Cancer surveillance procedures

The outcomes were based on patients’ self-reported use of surveillance procedures during the 12 months preceding the survey at follow-up (approximately two years after being diagnosed with breast cancer). The item asked, “How often have you done the following things in the past 12 months, as part of your routine cancer follow-up? Do not include the times that you have done things because of a new symptom or health concern.” Participants indicated the frequency across five response options, ranging from ‘0 times’ to ‘5 or more times’ of: 1) doctor visit and physical exam, 2) mammogram, and 3) breast self-exam. The baseline survey omitted these adherence measures because some patients might not have completed treatment. The outcome of doctor visit and physical exam was dichotomized to “less than two times” vs. “two or more times” in the past 12 months based on typical recommendations for 6-monthly routine physical exams or more (11–17). Because of the high prevalence of receiving one or more mammograms in this study population and growing concern about possible overutilization, we categorized the responses for the mammography measure as non-adherent (zero times in the past year), adherent (one time in the past year) or over-utilizing (two or more times in the last year). As the highest frequency of all surveillance behaviors was ‘5 or more times’ in the past 12 months, BSE was dichotomized to “less than five times” vs. “five or more times”. We further analyzed BSE as a continuous variable across the five response categories.

Predictor Measure – Information seeking from nonmedical sources (Seeking)

To measure patients’ information seeking from nonmedical sources, we asked participants to think back to the first few months of their cancer diagnosis and to recall whether they sought information (yes/no) about treatments, information related to their cancer, and information about quality-of-life issues from a variety of interpersonal and media sources as described in previous research (32, 33). These different sources included: 1) television or radio, 2) books, brochures or pamphlets, 3) newspapers or magazines, 4) the internet other than personal e-mail, 5) family members, friends, or co-workers, 6) other cancer patients, 7) support groups, and 8) telephone hotlines from the American Cancer Society, comprising 24 items across three topic domains. Of these sources, previous research from this study population indicated that the main nonmedical sources of information that breast cancer survivors sought from included (from most frequent to least frequent) books, brochures, or pamphlets; family, friends, co-workers; other cancer patients; and the internet (40). Responses were summed within each topic domain (i.e., treatment, cancer information, and quality of life) and the summed scores were standardized and averaged to form the seeking from nonmedical sources scale (Cronbach’s alpha=0.81).

Predictor Measure – Patient-Clinician Information Engagement (PCIE)

Seeking cancer-related information from medical sources was measured using the PCIE scale as described by Martinez and colleagues (31). Briefly, the scale comprised eight survey items (yes/no) that asked participants to think back to the first few months of their cancer diagnosis and to recall whether they: 1) sought information about treatments from their treating physician, 2) sought treatment information from other physicians or health professionals, 3) actively looked for information about their cancer from their treating physician, 4) looked for cancer information from other physicians or health professionals, 5) discussed information from other sources with their treating physician, 6) received suggestions from their treating physician to get information from other sources, 7) actively looked for information about quality of life issues from their treating physician, and 8) actively looked for quality of life information from other physicians or health professionals. Each item was standardized and the average of these eight standardized items formed the PCIE scale. This measure demonstrated reasonable internal consistency in the analyzed sample (Cronbach’s alpha=0.80).

Potential Confounder Variables

Informed by prior literature, the analysis controlled for demographic variables (age in years, gender, education level, marital status, and race/ethnicity), respondents’ indication of concern at baseline about how to reduce their chances of cancer recurrence (yes/no), their tendency to follow doctors’ recommendations for tests to monitor their cancer (ranging from ‘Never’ to ‘Always’), cancer-related worry (Lerman Cancer Worry Scale)(41), and other clinical characteristics including the American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union Against Cancer TNM stage at diagnosis (derived from the PCR data and ranging from Stage 0 to III) (42), treatment received (i.e., self-reported type of surgery, radiation therapy, and systemic therapy) and self-reported health status (ranging from ‘Poor’ to ‘Excellent’). All confounder variables were assessed at baseline.

Statistical analysis

We conducted the analyses using Stata Release 12 (43). Based on initial descriptive analyses, 50% of the analyzed sample had missing data on one or more variables. The majority of missing values (39%) occurred in the covariate measure of patients’ tendency to follow doctors’ recommendations for tests because 84 cases were randomly selected to receive the short form of the survey and were therefore not asked this item (44). Excluding this control variable from the analysis did not alter the substantive findings of the study and the final model retained this variable. Additional missing cases were due to missing values on one or more of the three individual items that asked about adherence to mammography (29 cases), BSE (50 cases), and physical examinations (12 cases). Missingness for the PCIE and information seeking from nonmedical sources was minimal in this analysis, only one respondent had missing values for PCIE while two had missing values on the information seeking from nonmedical sources. We performed multiple imputations to address missing data only for predictor variables using the Stata MI program according to recommended procedures (45, 46) to generate 30 datasets with imputed values of predictor variables. To analyze the associations between the information seeking measure and surveillance behaviors, we utilized binary logistic regression to predict physical examinations and BSE and multinomial logistic regressions to predict mammography, controlling for potential confounders.

RESULTS

Among the analyzed sample, the mean age of participants at diagnosis was 62 years, 50% had some college education or higher, and 87% were white (Table 1). At follow-up, the majority of participants reported two or more doctor visits and physical examination (84.7%). For mammography surveillance, 4% were not adherent (no mammogram in the past year), 56% of women were adherent (one mammogram), while 39% were categorized as over-utilizers (two or more mammograms). Therefore, the majority of women received at least one mammogram for surveillance in this study sample. In addition, 60% of participants reported having performed BSE five or more times in the past year.

Table 1.

Characteristics of analyzed sample (N=352).

| Participant characteristic | Range | Mean | SD | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29 to 90 | 62.2 | 12.9 | ||

| Education | |||||

| High school and below | 176 | 50.1 | |||

| Some college and above | 175 | 49.9 | |||

| Race/ ethnicity | |||||

| White | 307 | 87.2 | |||

| Black | 36 | 10.2 | |||

| Hispanic or other | 9 | 2.6 | |||

| Marital status | |||||

| Not married | 130 | 36.9 | |||

| Married | 222 | 63.1 | |||

| Seeking of cancer information from nonmedical sources | −1.15 to 2.84 | 0.25 | 0.87 | ||

| PCIE | −1.22 to 1.24 | 0.12 | 0.63 | ||

| Concern about reducing chances of recurrence | |||||

| No | 70 | 20.2 | |||

| Yes | 276 | 79.8 | |||

| Cancer stage | |||||

| Stage 0 | 67 | 19.0 | |||

| Stage I | 153 | 43.5 | |||

| Stage II | 111 | 31.5 | |||

| Stage III | 21 | 6.0 | |||

| Health status | 1 to 5 | 3.86 | 1.12 | ||

| Surgery | |||||

| Lumpectomy | 217 | 61.8 | |||

| Mastectomy | 109 | 31.1 | |||

| Other | 25 | 7.1 | |||

| Radiation therapy | |||||

| No | 96 | 27.4 | |||

| Yes | 255 | 72.6 | |||

| Systemic therapy | |||||

| No | 58 | 16.5 | |||

| Yes (chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, or biologics) | 293 | 83.5 | |||

| Followed doctor’s recommendations for tests | 1 to 5 | 4.57 | 0.94 | ||

| Lerman Cancer Worry Scale | 1 to 5 | 2.41 | 0.91 | ||

Table 2 presents the results of the binary logistic regressions predicting physical examination and BSE surveillance behaviors. Seeking from medical or nonmedical sources did not significantly predict physical examination (two or more physical examinations vs. less than two). Seeking from nonmedical sources was associated with performing BSE five or more times in the past year at follow-up (OR = 1.52; 95% CI = 1.01 to 2.29; p = 0.046), controlling for potential confounders (Table 2). This association held when considering frequency of BSE as a continuous variable (Spearman’s rho = 0.194, p = 0.001; Kendall’s tau-b = 0.150, p = 0.001). Using multinomial logistic regressions, information seeking from medical and nonmedical sources was not associated with over-utilization of routine mammography (vs. being adherent) or with adherence to surveillance mammography (vs. non-adherence) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Logistic regression analyses predicting physical examination and BSE at follow-up with cancer-related information seeking from nonmedical and medical sources.

| Sources of cancer-related information seeking | Physical Examination (Two or more visits in the past 12 months)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | |

| Nonmedical | 1.43 | 1.00 – 2.05 | 1.15 | 0.67 – 1.97 |

| Medical | 1.56 | 0.97 – 2.51 | 1.02 | 0.50 – 2.10 |

| BSE (Five or more times in the past 12 months)

|

||||

| Unadjusted OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | |

|

| ||||

| Nonmedical | 1.63 | 1.22 – 2.16 | 1.52 | 1.01 – 2.29 |

| Medical | 1.58 | 1.08 – 2.32 | 0.98 | 0.58 – 1.66 |

Notes. OR = Odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval. Adjusted ORs controlled for baseline confounder variables (age, education, ethnicity, marital status, concern about recurrence, cancer stage, health status, surgery, radiation therapy, systemic therapy, following doctors’ recommendations for tests, and Lerman Cancer Worry scale).

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression analyses predicting mammography at follow-up with cancer-related information seeking from nonmedical and medical sources.

| Sources of cancer-related information seeking | Adherence to mammography (Once in the past 12 months vs. None)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted RRR | 95% CI | Adjusted RRR | 95% CI | |

| Nonmedical | 0.90 | 0.48 – 1.68 | 1.14 | 0.38 – 3.45 |

| Medical | 0.70 | 0.29 – 1.70 | 0.40 | 0.11 – 1.54 |

| Overutilization of mammography (Two or more times in the past 12 months vs. None)

|

||||

| Unadjusted RRR | 95% CI | Adjusted RRR | 95% CI | |

|

| ||||

| Nonmedical | 0.86 | 0.46 – 1.68 | 0.89 | 0.29 – 2.78 |

| Medical | 0.82 | 0.33 – 2.01 | 0.50 | 0.12 – 2.01 |

| Overutilization of mammography (Two or more times in the past 12 months vs. Once)

|

||||

| Unadjusted RRR | 95% CI | Adjusted RRR | 95% CI | |

|

| ||||

| Nonmedical | 0.96 | 0.73 – 1.25 | 0.78 | 0.53 – 1.15 |

| Medical | 1.17 | 0.81 – 1.68 | 1.24 | 0.74 – 2.05 |

Notes. RRR = Relative risk ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval. Adjusted RRRs controlled for baseline confounder variables (age, education, ethnicity, marital status, concern about recurrence, cancer stage, health status, surgery, radiation therapy, systemic therapy, following doctors’ recommendations for tests, and Lerman Cancer Worry scale).

DISCUSSION

Active seeking of cancer information represents a strategy for cancer patients’ to cope with breast cancer (47, 48). Prior studies have found linkages between information seeking behaviors and various important behavioral outcomes among cancer survivors, including a positive association between information seeking and participation in shared decision-making about their care (48) and adoption of healthier lifestyle practices such as fruit and vegetable intake (49). In contrast to prior studies, this present research did not find an association between seeking cancer-related information from medical and nonmedical sources and adherence to physical examination and mammography surveillance.

Several observations arising from the study findings deserve further discussion. First, the majority of breast cancer survivors in this study reported undergoing mammography (95.7%) and physical examinations (84.7%) at or above recommended levels. This finding compares favorably with other studies which typically described underuse of surveillance mammography or clinical visits for follow-up among women diagnosed with breast cancer (19, 20, 25). Although direct comparisons across studies are not possible due to differences in study populations and study designs, possible reasons for the higher adherence in this present analysis may be due to the study population who were more recently diagnosed (within the last 2 years) or secular trends over time of survivors being more adherent for follow-up with physical examinations and mammography. This present study also found that about 40% of participants reported undergoing two or more mammograms in the previous year, which exceeded the typical recommendations of performing annual mammography for surveillance purposes. While we did not detect significant associations between information seeking behaviors and what might be considered overuse of mammography, the prevalence of over-utilization of mammography may warrant further study of the underlying reasons.

This research has several strengths. The sample was population-based representing a broader range of demographic characteristics. Moreover, the present study utilized longitudinal data analysis, which enabled us to establish temporal precedence of information seeking predictor variables at baseline in relation to surveillance at follow-up. Although we were not able to conduct a true lagged analysis to control for prior adherence to surveillance procedures, we controlled for patients’ tendency to follow their doctor’s recommendations for tests to monitor their disease at baseline. While this precludes a claim that information seeking produced a change in individual adherence to surveillance over time, this study compares favorably with prior observational research limited by cross-sectional data with all measures collected simultaneously.

The study was limited in terms of relying on patients’ self-reported engagement with cancer information and receipt of cancer surveillance. Self-reported measures of these variables may be subject to recall or social desirability bias. Although self-reported adherence was not validated against administrative or medical records in this study, validation studies on screening mammography have found self-reported screening to be reasonably accurate (50–52). Because the information seeking measures were not specific to patients actively searching for information about surveillance procedures, we were not able to perfectly match the behavior of interest (information seeking) to the outcomes of surveillance adherence. However, the information seeking measures do provide valuable indications of patients’ overall information seeking about various cancer topics (treatments, information related to cancer, quality-of-life issues), which routine surveillance is a component of. Furthermore, the items asked about patients’ information-seeking behaviors in the first few months after diagnosis; this is a stressful time period for most patients and they may have difficulty recalling their information seeking behaviors. In addition, despite the longitudinal analysis, the observational design is unable to prove a causal relationship between information seeking and adherence. As our study population was confined to patients from the Pennsylvania Cancer Registry, the inferences from this study may not generalize to breast cancer survivors in other geographic areas. Finally, we cannot know exactly if, or when, the study participants have ended their active treatment for breast cancer. For instance, some women may be undergoing hormonal therapy, which typically lasts for 5 years and would therefore be continuing with clinic visits and physical examinations as part of their treatment. In this analysis, we controlled for patients’ receipt of systemic therapy to partially address the potential threat that ongoing hormonal therapy would confound the observed association between information engagement and adherence.

The clinical implications of the discovery that cancer-related information seeking is associated with regular BSE, a surveillance behavior that is not widely recommended for breast cancer survivors, remain unknown and deserve further research and discussion. In view of the findings from this research, one practice implication is how should clinicians communicate with their patients about information from nonmedical sources that may be over-emphasizing the benefits of BSE or other surveillance procedures that are not widely recommended? More rigorous research on whether BSE influences meaningful outcomes including early detection and survival may be necessary before advocating (or discouraging) patients’ practice of BSE for routine surveillance. Another implication for future research would be to assess whether other non-recommended surveillance procedures that may entail higher costs or adverse effects (e.g., advanced imaging procedures such as PET or CT) are similarly associated with active information seeking from nonmedical sources. Forthcoming research from this team is addressing these specific research questions.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: 5P50CA095856-05 and 5P50CA095856-06 from the National Cancer Institute

Grant support

The authors wish to acknowledge the funding support of the National Cancer Institute’s Center of Excellence in Cancer Communication (CECCR) located at the Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania (P20CA095856 and P50CA095856). An earlier version of part of this analysis was presented at the International Communication Association 2012 Annual Conference in Phoenix, Arizona (May 24-28, 2012).

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: None

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2007. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2010. Report No.: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grunfeld E, Noorani H, McGahan L, Paszat L, Coyle D, van Walraven C, et al. Surveillance mammography after treatment of primary breast cancer: A systematic review. The Breast. 2002;11(3):228–35. doi: 10.1054/brst.2001.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mellink WA, Holland R, Hendriks JH, Peeters PH, Rutgers EJ, van Daal WA. The contribution of routine follow-up mammography to an early detection of asynchronous contralateral breast cancer. Cancer. 1991 Apr 1;67(7):1844–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910401)67:7<1844::aid-cncr2820670705>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Senofsky GM, Wanebo HJ, Wilhelm MC, Pope TL, Jr, Fechner RE, Broaddus W, et al. Has monitoring of the contralateral breast improved the prognosis in patients treated for primary breast cancer? Cancer. 1986 Feb 1;57(3):597–602. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860201)57:3<597::aid-cncr2820570334>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houssami N, Abraham LA, Miglioretti DL, Sickles EA, Kerlikowske K, Buist DS, et al. Accuracy and outcomes of screening mammography in women with a personal history of early-stage breast cancer. JAMA. 2011 Feb 23;305(8):790–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Bock GH, Bonnema J, van Der Hage J, Kievit J, van de Velde CJH. Effectiveness of routine visits and routine tests in detecting isolated locoregional recurrences after treatment for early-stage invasive breast cancer: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004 Oct 01;22(19):4010–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lash TL, Fox MP, Buist DSM, Wei F, Field TS, Frost FJ, et al. Mammography surveillance and mortality in older breast cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007 Jul 20;25(21):3001–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.9572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schootman M, Jeffe D, Lian M, Aft R, Gillanders W. Surveillance mammography and the risk of death among elderly breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2008;111(3):489–96. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9795-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu WL, Jansen L, Post WJ, Bonnema J, Van de Velde JC, De Bock GH. Impact on survival of early detection of isolated breast recurrences after the primary treatment for breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009 Apr;114(3):403–12. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith TJ, Davidson NE, Schapira DV, Grunfeld E, Muss HB, Vogel VG, et al. American society of clinical oncology 1998 update of recommended breast cancer surveillance guidelines. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1999 Mar 01;17(3):1080–2. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khatcheressian JL, Wolff AC, Smith TJ, Grunfeld E, Muss HB, Vogel VG, et al. American society of clinical oncology 2006 update of the breast cancer follow-up and management guidelines in the adjuvant setting. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Nov 1;24(31):5091–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sunga AY, Eberl MM, Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM, Mahoney MC. Care of cancer survivors. Am Fam Physician. 2005 Feb 15;71(4):699–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) Health care guideline: Breast cancer treatment. 8. Institute of Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) Clinical practice guidelines for the management of early breast cancer. 2. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Cancer practice guidelines in oncology: Breast cancer v.1.2005. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pestalozzi BC, Luporsi-Gely E, Jost LM, Bergh J. ESMO minimum clinical recommendations for diagnosis, adjuvant treatment and follow-up of primary breast cancer. Annals of Oncology May 2005. 2005 May;16(suppl 1):i7–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mauriac L, Luporsi E, Cutuli B, Fourquet A, Garbay JR, Giard S, et al. Summary version of the standards, options and recommendations for nonmetastatic breast cancer (updated January 2001) Br J Cancer. 2003 Aug;89(Suppl 1):S17–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grunfeld E, Dhesy-Thind S, Levine M for The Steering Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Breast Cancer. Clinical practice guidelines for the care and treatment of breast cancer: Follow-up after treatment for breast cancer (summary of the 2005 update) Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2005 May 10;172(10):1319–20. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.045062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doubeni CA, Field TS, Ulcickas Yood M, Rolnick SJ, Quessenberry CP, Fouayzi H, et al. Patterns and predictors of mammography utilization among breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2006 Jun 1;106(11):2482–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Winer EP, Ayanian JZ. Factors related to underuse of surveillance mammography among breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Jan 1;24(1):85–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandelblatt JS, Lawrence WF, Cullen J, Stanton AL, Krupnick JL, Kwan L, et al. Patterns of care in early-stage breast cancer survivors in the first year after cessation of active treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Jan 1;24(1):77–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trask PC, Pahl L, Begeman M. Breast self-examination in long-term breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2008 Dec;2(4):243–52. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lash TL, Silliman RA. Medical surveillance after breast cancer diagnosis. Med Care. 2001 Sep;39(9):945–55. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200109000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breslau E, Jeffery D, Davis W, Moser R, McNeel T, Hawley S. Cancer screening practices among racially and ethnically diverse breast cancer survivors: Results from the 2001 and 2003 California health interview survey. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2010;4(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Winer EP, Ayanian JZ. Surveillance testing among survivors of early-stage breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007 Mar 20;25(9):1074–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carcaise-Edinboro P, Bradley C, Dahman B. Surveillance mammography for Medicaid/Medicare breast cancer patients. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2010;4(1):59–66. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0107-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rutten LJ, Arora NK, Bakos AD, Aziz N, Rowland J. Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: A systematic review of research (1980–2003) Patient Educ Couns. 2005 Jun;57(3):250–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beckjord E, Arora N, McLaughlin W, Oakley-Girvan I, Hamilton A, Hesse B. Health-related information needs in a large and diverse sample of adult cancer survivors: Implications for cancer care. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2008;2(3):179–89. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luker KA, Beaver K, Lemster SJ, Owens RG. Information needs and sources of information for women with breast cancer: A follow-up study. J Adv Nurs. 1996;23(3):487–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gray SW, Armstrong K, Demichele A, Schwartz JS, Hornik RC. Colon cancer patient information seeking and the adoption of targeted therapy for on-label and off-label indications. Cancer. 2009 Apr 1;115(7):1424–34. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez LS, Schwartz JS, Freres D, Fraze T, Hornik RC. Patient–clinician information engagement increases treatment decision satisfaction among cancer patients through feeling of being informed. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(3):384–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan ASL, Bourgoin A, Gray SW, Armstrong K, Hornik RC. How does patient-clinician information engagement influence self-reported cancer-related problems? Cancer. 2011;117(11):2569–76. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis N, Martinez LS, Freres DR, Schwartz JS, Armstrong K, Gray SW, et al. Seeking cancer-related information from media and family/friends increases fruit and vegetable consumption among cancer patients. Health Commun. 2012;27(4):380–8. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.586990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan AS, Mello S, Hornik RC. A longitudinal study on engagement with dieting information as a predictor of dieting behavior among adults diagnosed with cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2012 Mar 6; doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mello S, Tan ASL, Armstrong K, Schwartz JS, Hornik RC. Anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: The role of engagement with sources of emotional support information. Health Communication. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.690329. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith-McLallen A, Fishbein M, Hornik RC. Psychosocial determinants of cancer-related information seeking among cancer patients. J Health Commun. 2011 Feb;16(2):212–25. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: Final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. AAPOR; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagler RH, Romantan A, Kelly BJ, Stevens RS, Gray SW, Hull SJ, et al. How do cancer patients navigate the public information environment? understanding patterns and motivations for movement among information sources. J Cancer Educ. 2010 Sep;25(3):360–70. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0054-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dillman DA, Dillman DA. Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method. 2. New York: J. Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagler RH, Gray SW, Romantan A, Kelly BJ, DeMichele A, Armstrong K, et al. Differences in information seeking among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer patients: Results from a population-based survey. Patient Educ Couns. 2010 Dec;81(Suppl):S54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lerman C, Trock B, Rimer BK, Jepson C, Brody D, Boyce A. Psychological side effects of breast cancer screening. Health Psychology. 1991;10(4):259–67. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.4.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greene FL American Joint Committee on Cancer, American Cancer Society. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 43.StataCorp. Stata: Release 12. statistical software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelly BJ, Fraze TK, Hornik RC. Response rates to a mailed survey of a representative sample of cancer patients randomly drawn from the Pennsylvania cancer registry: A randomized trial of incentive and length effects. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010 Jul 14;10:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.StataCorp. Stata: Release 11. statistical software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Newman DA. Longitudinal modeling with randomly and systematically missing data: A simulation of ad hoc, maximum likelihood, and multiple imputation techniques. Organizational Research Methods. 2003 Jul 01;6(3):328–62. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fredette LS. Breast cancer survivors: Concerns and coping. Cancer Nursing. 1995;18(1):35–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rees CE, Bath PA. Information-seeking behaviors of women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001 Jun;28(5):899–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lewis N, Martinez LS, Freres D, Schwartz JS, Armstrong K, Gray SW, et al. Information seeking from media and family and friends increases fruit and vegetable consumption among cancer patients. Health Communication. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.586990. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DiMatteo MR, Robinson JD, Heritage J, Tabbarah M, Fox SA. Correspondence among patients’ self-reports, chart records, and audio/videotapes of medical visits. Health Commun. 2003;15(4):393–413. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1504_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Caplan LS, Mandelson MT, Anderson LA. Validity of self-reported mammography: Examining recall and covariates among older women in a health maintenance organization. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003 Feb 01;157(3):267–72. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Caplan LS, McQueen DV, Qualters JR, Leff M, Garrett C, Calonge N. Validity of women’s self-reports of cancer screening test utilization in a managed care population. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2003 Nov 01;12(11):1182–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]