Abstract

Induction of hyperactivity in the central auditory system is one of the major physiological hallmarks of animal models of noise-induced tinnitus. Although hyperactivity occurs at various levels of the auditory system, it is not clear to what extent hyperactivity originating in one nucleus contributes to hyperactivity at higher levels of the auditory system. In this study we compared the time courses and tonotopic distribution patterns of hyperactivity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus (DCN) and inferior colliculus (IC). A model of acquisition of hyperactivity in the IC by passive relay from the DCN would predict that the two nuclei show similar time courses and tonotopic profiles of hyperactivity. A model of acquisition of hyperactivity in the IC by compensatory plasticity mechanisms would predict that the IC and DCN would show differences in these features, since each adjusts to changes of spontaneous activity of opposite polarity. To test the role of these two mechanisms, animals were exposed to an intense hyperactivity-inducing tone (10 kHz, 115 dB SPL, 4 hours) then studied electrophysiologically at three different post-exposure recovery times (from 1 to 6 weeks after exposure). For each time frame, multiunit spontaneous activity was mapped as a function of location along the tonotopic gradient in the DCN and IC. Comparison of activity profiles from the two nuclei showed a similar progression toward increased activity over time and culminated in the development of a central peak of hyperactivity at a similar tonotopic location. These similarities suggest that the shape of the activity profile is determined primarily by passive relay from the cochlear nucleus. However, the absolute levels of activity were generally much lower in the IC than in the DCN, suggesting that the magnitude of hyperactivity is greatly attenuated by inhibition.

Keywords: Inferior colliculus, dorsal cochlear nucleus, hyperactivity, noise exposure, tinnitus

INTRODUCTION

Chronic tinnitus affects the quality of life of approximately 5 –15 % of the population of the United States (Roberts et al. 2010) and continues to be one of the major reasons for patient visits to the Otolaryngology clinic. Over the past decade, numerous animal models of the acute and chronic forms of tinnitus have been developed. These models are based on the use of manipulations which induce tinnitus in humans, such as exposure to intense noise and ototoxic drugs such as salicylate, quinine, cisplatin and carboplatin (Bauer 2004; Eggermont and Roberts, 2004; Rachel et al., 2002; Kaltenbach et al., 2002). These inducers of tinnitus lead to increases in spontaneous activity (hyperactivity) in brainstem auditory nuclei as well as in primary and secondary auditory cortical areas. Noise-induced hyperactivity has been well characterized at the level of dorsal cochlear nucleus (DCN) (Zhang and Kaltenbach, 1998; Kaltenbach and Afman, 2000; Zacharek et al., 2002; Brozoski et al., 2002; Kaltenbach et al., 2002; Kaltenbach et al., 2004), ventral cochlear nucleus (VCN)(Vogler et al. 2011), inferior colliculus (IC) (Bauer et al. 2008; Mulders and Robertson 2009; Dong et al. 2010) and auditory cortex (Norena et al. 2003; Seki and Eggermont 2003). Hyperactivity has been detected in animals that show behavioral patterns consistent with tinnitus using various psychophysical tests (Brozoski et al., 2002; Kaltenbach et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2011; Longenecker and Galazyuk, 2011; Middleton et al., 2011; Dehmel et al., 2012).

The mechanisms underlying the induction of hyperactivity in the auditory brainstem have been investigated in numerous studies. The prevailing view is that hyperactivity is due to a shift in the balance of excitation and inhibition (Roberts et al., 2010). Several auditory brainstem nuclei show reductions of inhibition and/or increases in excitation, following noise exposure (see reviews of Kaltenbach, 2007; 2011). The most notable examples include the DCN, VCN and IC. Following noise exposure, these nuclei show evidence of decreased glycinergic and gabaergic neurotransmission (Abbott et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2009; Milbrandt et al., 2000; Dong et al., 2010a, 2010b) and upregulated glutamatergic and cholinergic transmission (Jin and Godfrey, 2006; Jin et al., 2005, 2006; Zeng et al., 2009; Muly et al., 2004; Zeng et al., 2009; Dehmel et al., 2012).

A shift in the balance of excitation and inhibition is thought to be the result of synaptic plasticity triggered by injury to cochlear receptors. The resulting loss of normal input from the auditory nerve may trigger compensatory and non-compensatory adjustments in local circuitry. The compensatory adjustments can involve both anatomical and physiological changes. When there is loss of anatomical input, the lost synapses are replaced through the process of axonal sprouting and re-growth of new synapses (Benson et al., 1997; Bilak et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2004; Illing et al., 2005). When the loss of input is physiological, neurons can compensate homeostatically by scaling up the strength of weakened synapses (Desai et al., 2002; Turrigiano, 1998; Kim and Tsien, 2008; Stellwagen and Malenka, 2006; Knogler et al., 2010; Goel and Lee, 2007; O’Brien et al., 1998). Homeostatic changes have been implicated as a basis of tinnitus-related hyperactivity in the cochlear nucleus (Schaette and Kempter, 2006, 2008).

In addition to these compensatory mechanisms, deafferentation-induced hyperactivity may also be induced by non-compensatory mechanisms. For example, the spontaneous activity of neurons in the IC may be driven directly by passive relay of hyperactivity from the cochlear nucleus (CN). One of the afferent inputs to IC neurons comes directly from fusiform cells in the DCN. These cells have been shown to become hyperactive following intense noise exposure (Brozoski et al., 2002; Finlayson and Kaltenbach, 2009; Shore et al., 2008; Middleton et al., 2011). In addition, neurons in the VCN also become hyperactive (Vogler et al., 2011). Therefore, it is expected that a significant component of the hyperactivity induced in the IC after noise exposure might be inherited from these cochlear nucleus inputs.

These two responses to alterations of external inputs, (compensatory adjustments vs. passive relay) represent opposing forces and make fundamentally different predictions regarding the relationships between DCN and IC hyperactivity. If changes of activity in the DCN and IC are largely determined by compensatory adjustments in response to altered input, then the two nuclei should show very different levels and/or patterns of hyperactivity following cochlear injury. Because noise exposure causes decreases of spontaneous and stimulus-driven activity of auditory nerve fibers (Liberman and Kiang, 1978; Liberman and Dodds, 1984), a compensatory mechanism would trigger increases of activity in the cochlear nucleus, and the increases in spontaneous activity would exceed normal levels to compensate for lost stimulus driven activity (Schaette and Kempter, 2006). However, at the IC level, the loss of normal stimulus-driven activity would be offset by increases of spontaneously activity at the CN level. The increased input to the IC from the CN would therefore be expected to trigger a weaker increase of activity or even a decrease relative to that in the CN. In contrast, if hyperactivity in the IC is determined largely by passive relay from the CN, then the IC and CN should show similar levels and tonotopic patterns of hyperactivity following noise exposure.

To gain insight into this issue, we compared the tonotopic patterns of hyperactivity in the DCN and IC following intense sound exposure. We mapped spontaneous activity in both structures as a function of location along the tonotopic axis. Since, the tonotopic profiles of hyperactivity have previously been shown to change over time, comparison of DCN activity profiles were also compared with those from the contralateral IC at three different post exposure recovery periods. The results suggest two opposing response in the IC, one of which increases activity in conformance with a passive relay of afferent activity from the CN, the other of which leads to a global decrease in activity relative to that of its CN inputs.

METHODS

Subjects

Animals were Syrian golden hamsters ranging from 70–120 days of age. These were housed in the Biological Resources Unit of the Cleveland Clinic where they were placed on a 12hr:12 hr. daily light:dark cycle. Animals were assigned to two general groups, one to be exposed to an intense sound, the other to serve as unexposed controls. Both groups were further subdivided for different experiments based on their recovery times. The goal was to test for successful induction of hyperactivity in the IC and DCN following intense sound exposure. All experimental procedures for these studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Cleveland Clinic, which follows the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Sound exposure

The exposure sound was a 10 kHz continuous tone maintained at a level of 115 dB SPL for a period of 4 hours. Sound exposures were conducted in a cylindrical acrylic chamber, subdivided into 4 compartments by wire mesh partitions and closed at the top with a lid into which was mounted a 6 inch diameter loudspeaker (BEYMA CP-25). The chamber was placed inside a sound insulation booth (Acoustic Systems). Before placement of the animals into the chamber, an Etymotic probe tube microphone was positioned about 1 inch above the floor of the chamber in each compartment to approximate the level where the ears of the animals would be during the exposure period. The sound was then turned on, and the voltage input to the speaker adjusted until the tone level measured 115 dB SPL at the center of each compartment. Sound levels at different positions within each of the 4 compartments varied by about ±6 dB. Following calibration, one animal was placed in each of the 4 compartments, and the lid with the speaker placed over the chamber. Since the animals were awake during the exposure, the sound was initially turned on at a level of 80 dB SPL for 5 minutes so that the animals accommodated to the presence of a moderate level tone. The sound level was then turned up in 5 dB steps, every 2 minutes until a level of 115 dB SPL was reached. No sign that the sound caused an alteration of behavior was observed. The sound level was maintained at the 115 dB SPL level for the remainder of the exposure period. Throughout the exposure period the sound level was monitored to ensure constancy of the tone. After the exposure period, the animals were returned to the animal care facility and allowed a post-exposure recovery period of 1 to 6 weeks before commencing electrophysiological studies.

Surgery

Following the recovery period, each animal was placed inside a double-walled sound attenuation room, where anesthesia was induced using a mixture of ketamine/xylazine (117/18 mg/kg) administered i.m. A depth of anesthesia was induced at which the animal showed no toe pinch reflexes in any limbs, no corneal touch reflex and the breathing rate was regular and constant. The animal was then placed on a heating pad (Physitemp) that was controlled by feedback from a rectal probe sensor. A tracheotomy was performed, and the animal was mounted on a head brace. The skin was reflected laterally, and a craniotomy was performed with the aid of a surgical microscope (Leica MZ16F) to uncover the cerebellum and the area above the midbrain. The right inferior colliculus was exposed by removal of overlying portions of parietal bone and the caudal-most aspects of the cerebral hemispheres. The DCN was uncovered as described in a previous study (Finlayson and Kaltenbach 2009). Supplements of anesthetic were administered as needed, typically once every 45–60 minutes.

Electrophysiological recordings

Electrodes were micropipettes filled with 0.3 M NaCl and having tip impedances of 0.4–0.5 MΩ, sufficient to record activity from clusters of neurons (multiunit activity). Output from the electrode was amplified 1000X and bandpass filtered (300 Hz-10,000 Hz) using a WPI preamplifier (DAM80). The electrode signal was monitored on an oscilloscope and fed to a National Instruments board custom programmed using Matlab to perform measures of spontaneous activity and frequency tuning.

Recordings from the DCN were conducted in different pairs of animal groups (exposed and controls) from those used for recordings from the IC. For these recordings, the methods were the same as those described previously (Finlayson and Kaltenbach, 2009), activity being measured on the DCN surface in 3 rows of sites, with a spacing of 100 µm between sites and between rows. For IC recordings, the electrode was lowered manually until its tip was just above the IC. Further movement was controlled remotely using a Narashige 3D micromanipulator placed outside the acoustic booth. A video camera mounted on top of the microscope was used to view the surface of the IC and facilitate placements of the electrode tip. In each animal, activity was mapped as a function of depth along each of three penetrations through the IC spaced 200 µm apart horizontally. For each penetration, the electrode was lowered to a depth at which responses to a search stimulus could be elicited. Search stimuli were 30 ms bursts of white noise presented at a level of 80 dB SPL. Spontaneous activity was measured every 100 µm along a depth range from roughly 0.7 to 2.5 mm below the IC surface. This range spanned a characteristic frequency (CF) range of about 3 kHz to 32 kHz in the central nucleus of the IC (ICC).

The methods for assessing the effects of tone exposure on spontaneous activity and tuning curve thresholds were similar to those used in the DCN (Finlayson and Kaltenbach 2009). Briefly, spontaneous activity was recorded at each site by counting the number of voltage events exceeding −100 µV over a period of 90 seconds. The measures of spontaneous activity were plotted as a function of depth yielding an activity profile for each penetration. Activity profiles were then averaged across penetrations, yielding a mean activity profile for each animal. Comparison between mean activity profiles from exposed and control animals allowed assessment of the topographic distribution of any hyperactivity that was induced. Frequency tuning properties were performed every few hundred µm by counting the number of voltage events in response to each of 800 tonal stimuli (16 intensities and 50 frequencies), each lasting 30 ms (5 ms rise/fall time) and separated by an interstimulus interval of 40 ms, as described previously (Finlayson and Kaltenbach, 2009). These measures were used to plot response areas in which the bar height for each of the 800 stimulus conditions was proportioned to the number of counts during the stimulus period. The response areas were used to determine the CF and CF thresholds of the recorded neurons, which provided an estimate of the degree to which neural response thresholds were shifted as a consequence of the intense tone exposure.

Data analysis

Effects of tone exposure on the IC and DCN were examined by comparing the activity profiles in exposed animals with similar measures in controls at different post exposure recovery periods. For the DCN, the surface map was plotted as distance from the 6 kHz locus to generate an activity profile. The 6 kHz locus was chosen as the point of reference, as it was the highest frequency location where CF thresholds were normal or near normal levels (i.e., within 20 dB of normal thresholds) in exposed animals following the 115 dB SPL exposure. For ICC, the spontaneous rates at corresponding depths across penetrations were averaged to yield a plot of mean spontaneous activity (±S.E.M.) vs. depth (activity profiles). The topographic (depth) coordinates were translated into tonotopic coordinates using CFs derived from tuning curves from the control animal group. Differences between activity profiles of exposed and control animals were tested statistically using t-test and were judged to be significant if p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Establishing the tonotopic coordinates of the IC

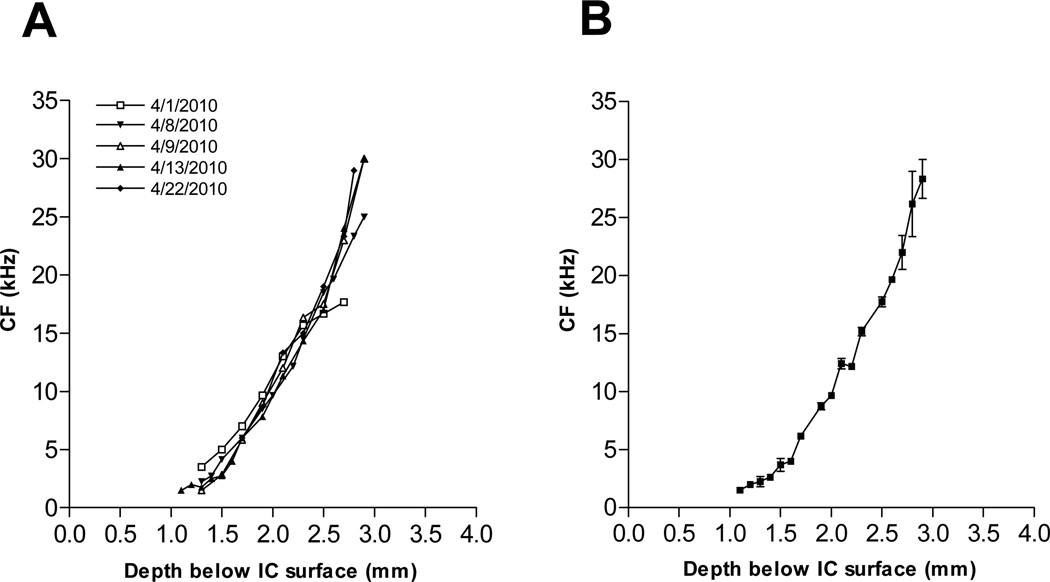

Although the tonotopic gradient of the hamster DCN has been described previously (Kaltenbach and Lazor, 1991), that for the hamster IC has not. We therefore began this study by mapping the frequency tuning properties of neuron clusters as a function of depth along vertical electrode penetrations through the IC. The results of this effort are shown for 5 animals in Fig. 1A. A systematic increase in CF with depth was observed in all 5 animals, with little variation across individuals. The average of the 5 gradients in Fig. 1A is shown in Fig. 1B. This gradient was similar to that for the rat described by others (Izquierdo et al., 2008; Malmierca et al., 2008, Fig. 1), except that the slope of the gradient in the hamster was slightly less steep owing to the more limited audiometric range of this species. The mean gradient of Fig. 1B was used to estimate the tonotopic loci of all subsequent recordings not only in control animals, but also in tone-exposed animals, whose tuning curves were usually too distorted above 6 kHz to establish reliable tonotopic coordinates.

Figure 1.

Tonotopic gradient from the hamster IC. A. Data for individual animals. Each curve represents the mean CF averaged across corresponding depths in 2–3 vertical penetrations through the IC of a single animal. B. Tonotopic gradient obtained by averaging the curves in panel A (n=5).

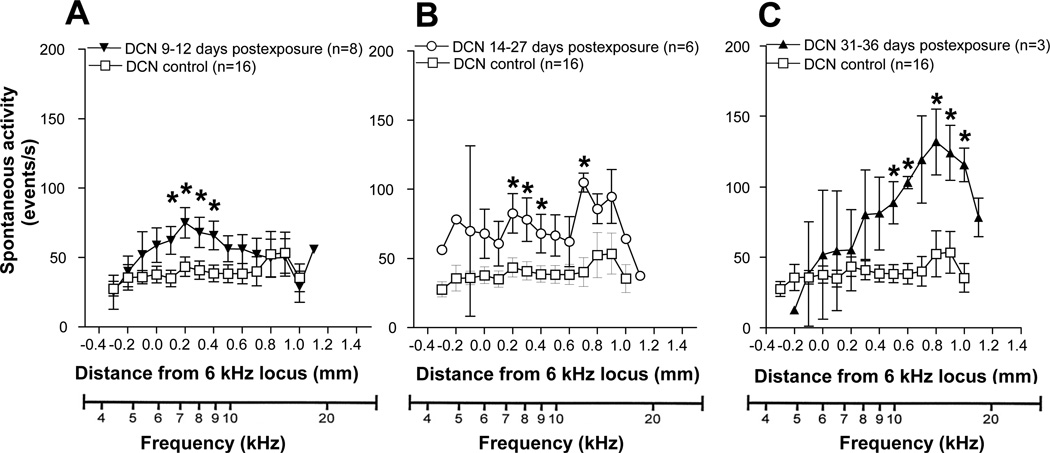

Induction of hyperactivity in the DCN

There was marked elevation of multiunit spontaneous activity across much of the tonotopic range of the DCN in noise exposed animals compared to controls. However, the magnitude and tonotopic distribution of this hyperactivity depended on the post-exposure recovery time (Fig. 2A–C). In the early post-exposure (PE) group (PE: 9–12 days), most of the loci showed a robust increase of activity, exceeding 50 events/s compared to < 40 events/s in the control group. The peak of the activity profile was reached at the 7 kHz locus (Fig 2A). The elevation in spontaneous activity was generally broadly distributed, spanning most of the tonotopic range. The increase in spontaneous activity was stronger in the intermediate post-exposure group (PE: 14–27 days) with most of the loci showing activity between 60 and 75 events/sec (Fig 2B). The activity peak was over 100 events/s and occurred at the 12 kHz locus. In the latest post-exposure group (PE: 31–36 days), the activity profile was further increased and showed a narrowly defined profile of hyperactivity which reached its peak at the 13 kHz locus (Fig 2C), but rolling off sharply in the high and low frequency coordinates of the DCN.

Figure 2.

Mean spontaneous activity profiles in the DCN of tone-exposed and control animals compared at different post-exposure times. A. Short post-exposure time (9–12 days after exposure). B. Middle post-exposure time (14–27 days after exposure). C. Long post-exposure time (31–36 days after exposure). Tonotopic axes is adapted from Kaltenbach and Afman, (2000) based on recordings in control animals.

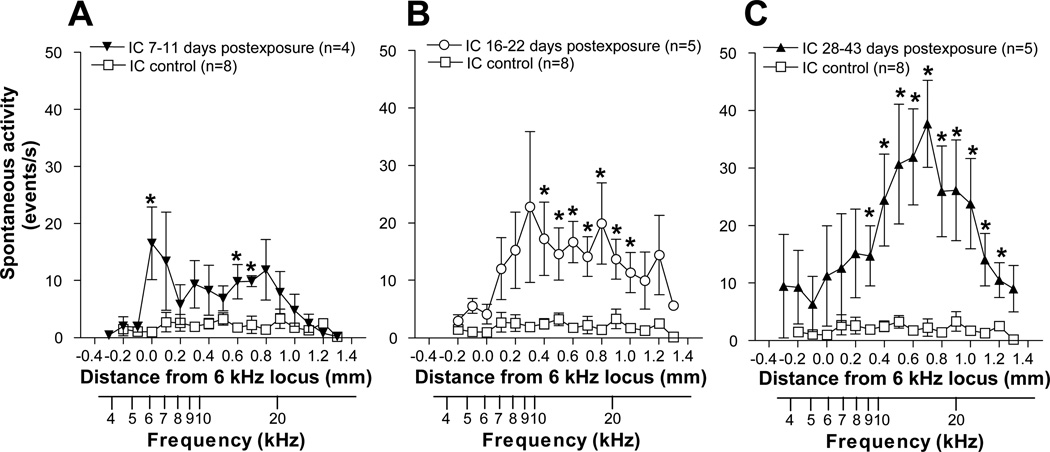

Induction of hyperactivity in the ICC

Exposure to intense sound also resulted in major elevations of spontaneous activity in the ICC relative to control levels. However, as was observed in the DCN and is shown in Fig. 3, the distribution and degree of the elevation depended on post-exposure recovery time. Animals examined in the earliest post-exposure time frame (PE: 7–11 days) showed a modest increase in activity over much of the tonotopic range. Activity in this group was between 8 and 12 events/s over most of the middle third (7–16 kHz) of the tonotopic range (Fig 3A). Animals examined in the intermediate post-exposure time frame (PE: 16–22 days) also displayed a broadly distributed pattern of hyperactivity, but the levels were generally higher than those in the early PE group, falling in the range of 15–23 events/sec over most of the middle third of the tonotopic range (Fig 3B). The differences between exposed and control activity levels were significant at all sites from the 10 kHz to the 23 kHz loci (p < 0.05). In animals studied 28–43 days after exposure (mean: 33 days), hyperactivity became more focused in the middle of the tonotopic range, with a distinct peak reaching 38 events/s just above the 16 kHz locus but rolling off sharply toward control levels in the upper and lower frequency regions of the tonotopic range (Fig 3C). In the latter group, activity was significantly higher than control levels at all loci from the 9 kHz to the 28 kHz loci (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Mean spontaneous activity profiles in the IC of tone-exposed and control animals compared at different post-exposure times. A. Short post-exposure time (7–11 days after exposure). B. Middle post-exposure time (16–22 days after exposure). C. Long post-exposure time (28–43 days after exposure). Tonotopic axes based on the CF gradient in Fig. 1 are shown below each graph.

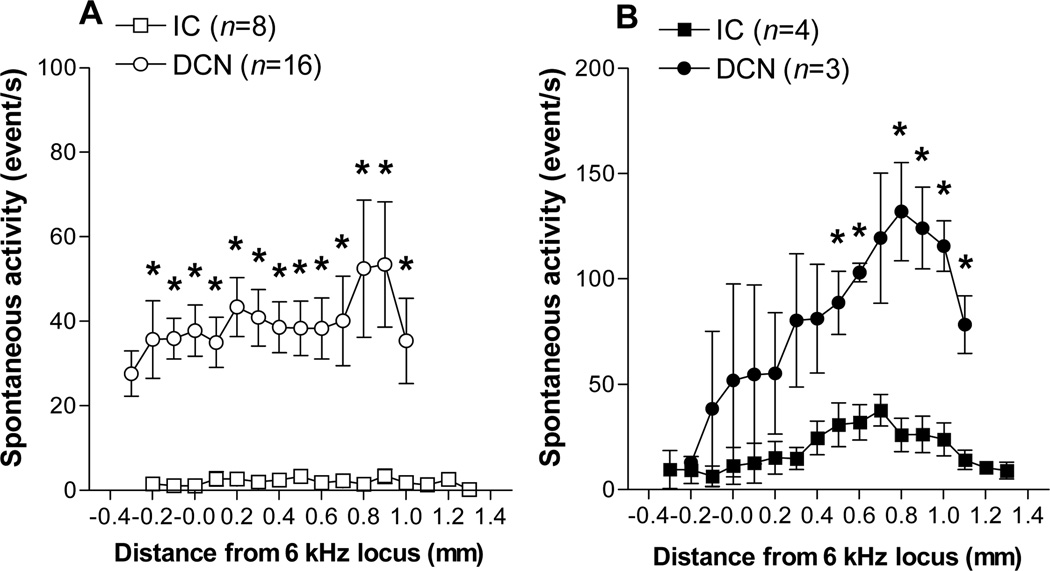

Comparison of hyperactivity profiles in the IC and the DCN

A comparison of activity profiles from the DCN and IC of control animals is shown in Fig. 4A, while a similar comparison for exposed animals (later PE group only) is shown in Fig. 4B. The comparisons reveal that both the levels of normal activity in the IC of control animals and the levels of hyperactivity in the IC of exposed animals were much lower than their counterparts in the DCN. This difference was robust. For example, the DCN of control animals yielded activity that was mostly between 30 and 40 events/s across the tonotopic range, while the IC of control animals was consistently below 5 events/s. In the exposed animals, hyperactivity in the DCN was mostly above 80 events/s, while in the IC, hyperactivity was mostly between 15 and 30 events/s. These differences were large enough to raise the possibility that the lower activity in the IC might have resulted from surgical damage to the IC or from injury resulting from electrode penetration. However, attempts were made to map spontaneous activity with metal microelectrodes having similar impedance but smaller diameter to minimize damage. This effort did not yield the higher levels of spontaneous activity expected. Nor was there any evidence of altered CF thresholds in the frequency tuning curves recorded from the IC of control animals with either size electrodes (data not shown). These findings suggest that the lower levels of spontaneous activity in the IC were not likely related to electrode-induced injury to the IC.

Figure 4.

Comparison of mean activity profiles from the IC with those from the DCN. A. Control animals. B. Exposed animals. Note that each graph shows the much lower levels of activity recorded in the IC relative to those recorded in the DCN. Data were obtained from the long post-exposure recovery time group (31–36 days for the DCN, 28–43 days for the IC).

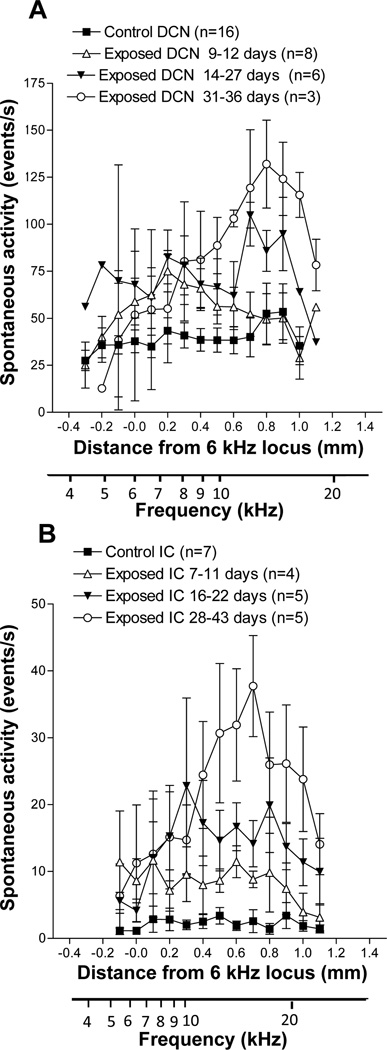

The activity profiles from each of the 3 postexposure time frames are presented in Fig. 5A for the DCN and in Fig. 5B for the IC. Despite the lower levels of spontaneous activity in the IC, both the DCN and IC showed two important parallels. First, there was a progressive increase in the level of hyperactivity over time. Second, both nuclei showed a progressive sharpening of the activity profiles over time, with broad distributions of hyperactivity in the early post-exposure recovery group, and a distinct peak of hyperactivity at closely spaced tonotopic loci in the later post-exposure recovery group (Figs. 5A–B). In these ways, the time course of emergence of hyperactivity in the IC and its tonotopic distribution pattern approximately mirrors the changes occurring in the DCN, although the fact that the activity in the IC is consistently lower than that in the DCN suggests that factors that suppress activity are present in the IC that are weak or absent in the DCN.

Figure 5.

Comparison of activity profiles at different post-exposure recovery times for the DCN (A) and IC (B). Both graphs show similar upward trends in the overall levels of activity across the tonotopic range and a sharpening of the activity profile over time. Note that peak levels of hyperactivity in the late recovery groups were centered on tonotopic loci that were close together (13 kHz in the DCN and 16 kHz IC).

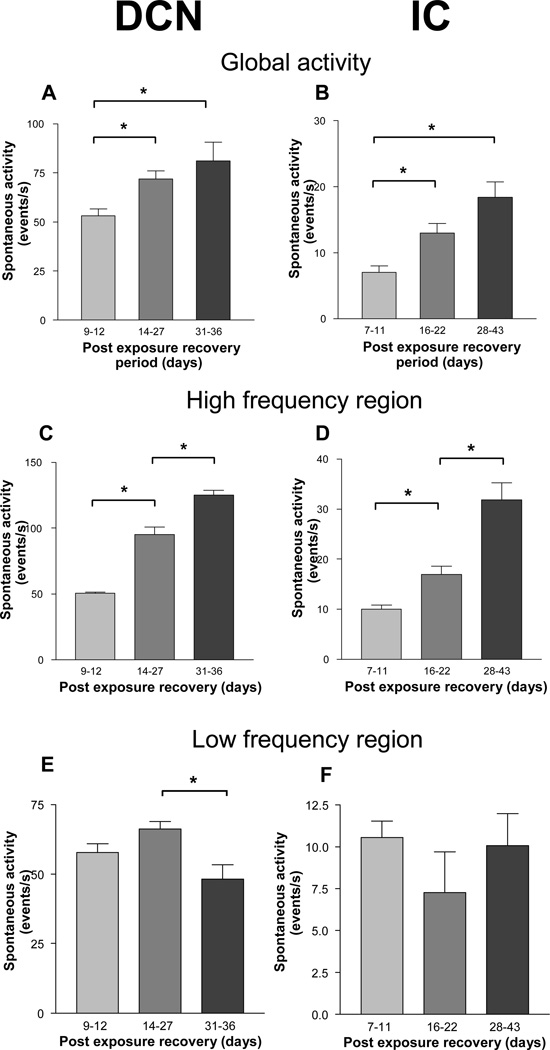

Comparison of the tonotopic profiles of activity with mean activity averaged across the tonotopic range

Since a number of studies examining the effects of noise on spontaneous activity have compared only the mean rates averaged across the neural population, we were interested in knowing how these trends compared in different tonotopic regions of their respective structures. The results, presented in Fig. 5, reveal some interesting differences. When activity was averaged across all tonotopic locations to obtain a single mean representing global activity throughout the DCN or IC, irrespective of variations at different tonotopic locations, the upward trends in activity with post-exposure recovery time were clearly apparent for both structures (Fig. 6A–B). A similar result was obtained when activity from the high frequency (>12 kHz) band was averaged (Fig. 6C–D). In contrast, activity averaged across sites in the low frequency region of these nuclei (5–8 kHz) showed no upward trends over time; both nuclei showed no statistically significant changes in activity from the earliest to the latest post-exposure times (Fig. 6E–F). Thus, the trends in activity changes over time show some noteworthy regional variations.

Figure 6.

Comparison of mean activity levels at each of the 3 post-exposure recovery time frames. A–B. Global activity. Each bar in the graphs was obtained by averaging the mean activity levels across all tonotopic locations within each nucleus. C–D. Activity in the high frequency region (tonotopic loci from 12 kHz and above). E–F. Activity in the low frequency region (tonotopic loci below 8 kHz). The asterisks represent statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Hyperactivity in the IC and DCN: the similarities

Our results revealed some striking similarities between the activity profiles of the DCN and IC after exposure to a 115 dB SPL tone. These similarities were evident both along the tonotopic and temporal axis. In both nuclei, the distribution of activity along the tonotopic axis became increasingly non-uniform with post-exposure recovery times. This was apparent as a narrowing of the profile over time and the tendency for the weight of hyperactivity to become increasingly focused in the middle frequency part of the tonotopic range. At the same time, the peak activity trended upward in its magnitude while the low frequency shoulder flanking the peak did not change appreciably over the span of the observation period. These changes indicate that the hyperactivity generating mechanism(s) remain(s) in a dynamic state over time and continues to shift the balance of excitation and inhibition over time toward the side of excitation in the middle frequency range.

A similar trend over time in the magnitude of hyperactivity following exposure to a 10 kHz tone for 1 hour has been observed in the IC of guinea pigs by Mulders and Robertson (2009). Their peak single unit activity levels increased from 7 spikes/s at 1 week post-exposure to 20 spikes/s at 4 weeks, compared to the increase in multiunit activity from 12 events/s at our early post-exposure time (~1–2 weeks) to 38 event/s at 4–6 weeks. One way in which the results of Mulders and Robertson differed from ours is that an increase in activity was observed over time at all tonotopic locations 4 weeks post-exposure; the tendency for the activity to become more heavily weighted in the middle part of the tonotopic range was less striking, but nonetheless apparent. Our results are also qualitatively similar to those reported earlier from our laboratory (Kaltenbach et al., 2000), which described a narrowing of hyperactivity in the middle of the tonotopic range of the DCN, although decreases in the degree of hyperactivity over time occurred in the high and low frequency regions. The upward trend in the present study, however, followed a slightly different time course from that in our earlier work, in that, as in the study by Mulders and Robertson, there was a progressive increase in peak activity over the entire period of the study (i.e., from 7 days to 43 days post-exposure), whereas in our previous work, the activity increased mainly in the first 5 days post-exposure, after which peak levels changed only negligibly. The difference between our two studies may be related to differences in the exposure conditions. Whereas the present study used an exposure level of 115 dB SPL, our earlier study used a exposure levels of 125–130 dB SPL. It may be that the different exposure levels induce different lesions types, which could, in turn, trigger different patterns or different time courses of changes in activity. Exposure levels above 126 dB SPL have been shown to result in severe damage to both outer and inner hair cells in hamsters, while levels from 110 to 120 dB SPL usually produced injury to outer hair cells, but inner hair cells remain intact (Kaltenbach et al., 1992).

Hyperactivity in the IC and DCN: the differences

An intriguing aspect of our results was the differences between hyperactivity in the DCN and IC. Both the level of hyperactivity in exposed animals and the levels of spontaneous activity in controls were much lower in the IC than in the DCN. The lower IC activity did not result from surgical injury to the IC, since tuning curve thresholds in control animals were within normal limits, and there was no indication that higher levels of activity emerged with the use of smaller diameter microwire electrodes, which would have caused less damage to the IC during penetration. The levels of spontaneous activity in the IC of control animals were similar to those observed in the IC of other species (Le Beau et al., 1996; Pollak and Park, 1993; Vater et al., 1992).

Lower levels of activity in the IC relative to those in the DCN may reflect the influence of strong inhibitory inputs to neurons in this auditory midbrain nucleus. It is well known that the ICC contains an abundance of local inhibitory circuits. Several studies have reported that disinhibitions of ICC spontaneous activity in normal hearing animals can result from injections of GABA or glycine receptor antagonists (e.g., bicucullline, strychnine) directly into the ICC (Pollak and Park, 1993; Davis, 2002; Xu et al., 2006). On the other hand, De Beau et al. (1996), found no effects of GABA-ergic and glycinergic agonists and antagonists on spontaneous activity of ICC neurons but found potent effects of these agents on monaural temporal responses to sound in anesthetized guinea pigs. The ICC receives heavy inhibitory input from nuclei of the lateral lemniscus, and investigations conducted in vivo show that spontaneous activity in the ICC can be disinhibited by iontophoretic injection of the GABA agonist, THIP, into the dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus (Faingold et al., 1993). Thus, although the exact source and circuit elements involved are unknown, the weight of evidence suggests that inhibitory synaptic influences in the ICC are strong and probably play a role in maintaining spontaneous activity at a low level. One possible functional implication of this lower IC hyperactivity is that it may facilitate adaptation to the tinnitus signal, leading to lower level sound percepts than would be possible if the percepts were determined by the level of hyperactivity in the DCN alone. A role of adaptation in tinnitus perception is suggested by the clinical finding that noise-induced permanent tinnitus is usually perceived as being very low in loudness (i.e., <15 dB SL) (Axelsson and Sandh, 1985; Axelsson and Prahsher, 2000).

Relationship between IC hyperactivity and DCN hyperactivity

One of the major issues concerning the origin of tinnitus is whether each auditory center that becomes hyperactive acquires its hyperactivity independently, or instead derives it passively from inputting extrinsic sources. The present results showing similar trends in the development of hyperactivity in the DCN and IC are consistent with the hypothesis that the hyperactivity in one structure is derived from the same source that drives hyperactivity in the other. One possibility is that the hyperactivity originates peripherally, is relayed to the DCN, which in turn relays it to the IC. This possibility would seem to be ruled out by earlier studies showing that noise exposure causes a decrease in mean spontaneous activity of auditory nerve fibers (Liberman and Kiang, 1978; Liberman and Dodds, 1984). Moreover, we have found previously that ablation of the cochlea, which completely destroyed the spiral ganglion, failed to abolish noise-induced hyperactivity in the DCN. On the other hand, a study by Mulders and Robertson (2009) found that noise-induced hyperactvity in the IC was abolished by ablation of the cochlea, although this effect only endured up to 6 weeks postexposure. After 8 weeks, the hyperactivity in the IC was not abolished by cochlear ablation or by blocking auditory nerve activity, indicating that IC hyperactivity becomes increasingly independent of peripheral input. Mulders and Robertson (2009) suggested that the hyperactivity that is present in the IC results from a heightened level of sensitivity of IC neurons to afferent inputs from the periphery.

A second possible origin of hyperactivity might be a higher level source, such as the auditory cortex, which may reach the IC and DCN via top down corticofugal pathways. Hyperactivity has been found to occur in the primary auditory cortex and beyond after exposure to intense sound (Seki and Eggermont, 2003; Norena and Eggermont, 2006), and it is known that descending fibers originating in laminae V of the primary auditory cortex project to the IC and DCN (Meltzer and Ryugo, 2006; Schofield and Coomes, 2006). However, the likelihood that hyperactivity in the DCN has its origin in descending pathways would seem to be ruled out by the findings of Zhang et al. (2006) showing that hyperactivity in the DCN persists even after a circumferential section around the CN, which would have severed all three tracts (dorsal and intermediate acoustic striae and trapezoid body) providing input to the CN. This finding would also seem to rule out the IC as a source of hyperactivity to the DCN.

The last two possibilities are that the IC and DCN acquire their hyperactivity independently by compensatory mechanisms or that the IC derives its hyperactivity from the DCN or other part of the cochlear nucleus by passive relay. An independent compensatory mechanism would require that each structure has its own capacity to adjust its spontaneous activity in response to alterations of input. The ability of neurons in the CNS to adjust their activity by homeostatic scaling after blockade of either their excitatory or inhibitory inputs has been well documented (see review of Turrigiano, 2011), and has been invoked to explain increases in spontaneous activity in the central auditory system after noise exposure (Schaette and Kempter, 2006, 2008). Accordingly, the loss of stimulus-driven and spontaneous activity in the auditory nerve caused by cochlear injury is viewed as a trigger of a compensatory increase in spontaneous activity in central auditory neurons as a means of maintaining their mean firing rates at a constant level. This model predicts that spontaneous activity would be increased the most in tonotopic regions sustaining the largest decreases of active input. However, the DCN and IC might be expected to show different profiles of hyperactivity in response to diminished auditory nerve input. The model predicts increases in activity in the DCN. However, because the hyperactivity in the DCN is relayed to the IC, it might be expected that the increase in activity in the IC would be less than that in the DCN. Moreover, a compensatory mechanism would predict that the greatest decreases of activity in the IC would occur at a tonotopic locus where hyperactive input from the DCN is highest. The fact that IC activity was generally much lower than that in the DCN is partially consistent with these predictions. On the other hand, because the DCN profile over time becomes increasingly sharp with a distinct peak in the mid-frequency region, it would be expected that the IC would show weaker compensation in this region, and perhaps even a decrease of activity, in this mid-frequency region. On the contrary, our results showed that the peak of the hyperactivity profile occurred at approximately the same tonotopic locus in the IC as in the DCN. Although our results do not completely rule out an independent compensatory mechanism of increased spontaneous activity in the two levels, a mechanism based exclusively on homeostatic or compensatory adjustments cannot fully account for the similar trends in the profiles and developmental time courses of hyperactivity in these two nuclei.

This leaves the last possibility, that hyperactivity in the IC may be derived from its external inputs. The most powerful of these inputs would be the hyperactive inputs from the DCN, since these project directly to the contralateral IC and therefore represent the most direct source of hyperactive input. Other nuclei in the auditory brainstem could also contribute to IC hyperactivity. The VCN has recently been shown to become hyperactive following intense noise exposure (Vogler et al., 2011), and there are both direct and indirect inputs to the IC from the VCN. It may be that noise-induced hyperactivity in the IC is dependent on inputs from both CN subdivisions. Studies examining the effects of removing or blocking inputs to the IC from these subdivisions would help determine the relative importance of these nuclei in driving hyperactivity in the IC. The answer to this question would have implications for understanding the origin of tinnitus-related signals and for defining potential therapeutic targets in the brain.

Research Highlights.

This article compares tonotopic patterns of noise-induced hyperactivity in the inferior colliculus and cochlear nucleus.

We found that hyperactivity develops over similar time courses and displays similar tonotopic patterns in the two nuclei.

The hyperactivity in the inferior colliculus is much lower in the inferior colliculus than in the dorsal cochlear nucleus.

The IC may acquire its hyperactivity from the DCN, but some degree of compensatory plasticity is probably also involved.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH DC009097.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Axelsson A, Sandh A. Tinnitus in noise-induced hearing loss. British Journal of Audiology. 1985;19:271–276. doi: 10.3109/03005368509078983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson A, Prasher D. Tinnitus induced by occupational and leisure noise. Noise Health. 2000;2:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer CA. Mechanisms of tinnitus generation. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;12:413–417. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000134443.29853.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer CA, Turner JG, Caspary DM, Myers KS, Brozoski TJ. Tinnitus and inferior colliculus activity in chinchillas related to three distinct patterns of cochlear trauma. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:2564–2578. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson CG, Gross JS, Suneja SK, Potashner SJ. Synaptophysin immunoreactivity in the cochlear nucleus after unlateral cochlear or ossicular removal. Synapse. 1997;25:243–257. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199703)25:3<243::AID-SYN3>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilak M, Kim J, Potashner SJ, Bohne BA, Morest DK. New growth of axons in the cochlear nucleus of adult chinchillas after acoustic trauma. Exp Neurol. 1997;147:256–268. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozoski TJ, Bauer CA, Caspary DM. Elevated fusiform cell activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of chinchillas with psychophysical evidence of tinnitus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2383–2390. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02383.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colletti V, Shannon RV, Carner M, Veronese S, Colletti L. Progress in restoration of hearing with the auditory brainstem implant. Prog Brain Res. 2009;175:333–345. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17523-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KA. Evidence of a functionally segregated pathway from dorsal cochlear nucleus to inferior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:1824–1835. doi: 10.1152/jn.00769.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehmel S, Pradhan S, Koehler S, Bledsoe S, Shore S. Noise overexposure alters long-term somatosensory-auditory processing in the dorsal cochlear nucleus-possible basis for tinnitus-related hyperactivity. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:1660–1671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4608-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai NS, Cudmore RH, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Critical periods for experience-dependent synaptic scaling in visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:783–789. doi: 10.1038/nn878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S, Mulders WH, Rodger J, Woo S, Robertson D. Acoustic trauma evokes hyperactivity and changes in gene expression in guinea-pig auditory brainstem. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:1616–1628. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont JJ, Roberts LE. The neuroscience of tinnitus. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:676–682. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faingold CL, Anderson CA, Randall ME. Stimulation or blockade of the dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus alters binaural and tonic inhibition in contralateral inferior colliculus neurons. Hear Res. 1993;69:98–106. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90097-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson PG, Kaltenbach JA. Alterations in the spontaneous discharge patterns of single units in the dorsal cochlear nucleus following intense sound exposure. Hear Res. 2009;256:104–117. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel A, Lee HK. Persistence of experience-induced homeostatic synaptic plasticity through adulthood in superficial layers of mouse visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6692–6700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5038-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illing RB, Kraus KS, Meidinger MA. Reconnecting neuronal networks in the auditory brainstem following unilateral deafening. Hear Res. 2005;206:185–199. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo MA, Gutiérrez-Conde PM, Merchán MA, Malmierca MS. Non-plastic reorganization of frequency coding in the inferior colliculus of the rat following noise-induced hearing loss. Neurosci. 2008;154:355–369. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA. The dorsal cochlear nucleus as a contributor to tinnitus: mechanisms underlying the induction of hyperactivity. Prog Brain Res. 2007;166:89–106. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)66009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA. Tinnitus: Models and mechanisms. Hear Res. 2011;276:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Lazor J. Tonotopic maps obtained from the surface of the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the hamster and rat. Hear Res. 1991;51:149–160. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90013-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Afman CE. Hyperactivity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus after intense sound exposure and its resemblance to tone-evoked activity: a physiological model for tinnitus. Hear Res. 2000;140:165–172. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Godfrey DA. Dorsal cochlear nucleus hyperactivity and tinnitus: are they related? Am J Audiol. 2008;17:S148–S161. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2008/08-0004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Rachel JD, Mathog TA, Zhang J, Falzarano PR, Lewandowski M. Cisplatin-induced hyperactivity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus and its relation to outer hair cell loss: relevance to tinnitus. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:699–714. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.2.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Schmidt RN, Kaplan CR. Tone-induced stereocilia lesions as a function of exposure level and duration in the hamster cochlea. Hear Res. 1992;60:205–215. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90022-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Zacharek MA, Zhang J, Frederick S. Activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of hamsters previously tested for tinnitus following intense tone exposure. Neurosci Lett. 2004;355:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Zhang J, Afman CE. Plasticity of spontaneous neural activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus after intense sound exposure. Hear Res. 2000;147:282–292. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Gross J, Morest DK, Potashner SJ. Quantitative study of degeneration and new growth of axons and synaptic endings in the chinchilla cochlear nucleus after acoustic overstimulation. J Neurosci Res. 2004;77:829–842. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Tsien RW. Synapse-specific adaptations to inactivity in hippocampal circuits achieve homeostatic gain control while dampening network reverberation. Neuron. 2008;58:925–937. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knogler LD, Liao M, Drapeau P. Synaptic scaling and the development of a motor network. J Neurosci. 2010;30:8871–8881. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0880-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Beau FE, Rees A, Malmierca MS. Contribution of GABA- and glycine-mediated inhibition to the monaural temporal response properties of neurons in the inferior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:902–919. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.2.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman MC, Dodds LW. Single-neuron labeling and chronic cochlear pathology. II. Stereocilia damage and alterations of spontaneous discharge rates. Hear Res. 1984;16:43–53. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman MC, Kiang NY. Acoustic trauma in cats. Cochlear pathology and auditory-nerve activity. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1978;358:1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longenecker RJ, Galazyuk AV. Development of tinnitus in CBA/CaJ mice following sound exposure. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2011;12:647–658. doi: 10.1007/s10162-011-0276-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmierca MS, Izquierdo MA, Cristaudo S, Hernández O, Pérez-González D, Covey E, Oliver DL. A discontinuous tonotopic organization in the inferior colliculus of the rat. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4767–4776. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0238-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor N, Licari F, Klapchar M, Elkin R, Gao Y, Chen G, Kaltenbach JA. Noise-induced hyperactivity in the inferior colliculus: its relationship with hyperactivity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. 2012 doi: 10.1152/jn.00833.2011. (Submitted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed SB, Kaltenbach JA, Church MW, Burgio DL, Afman CE. Cisplatin-induced increases in spontaneous neural activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus and associated outer hair cell loss. Audiology. 2000;39:24–29. doi: 10.3109/00206090009073051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloni EG, Davis M. The dorsal cochlear nucleus contributes to a high intensity component of the acoustic startle reflex in rats. Hear Res. 1998;119:69–80. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer NE, Ryugo DK. Projections from auditory cortex to cochlear nucleus: A comparative analysis of rat and mouse. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2006;288:397–408. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton JW, Kiritani T, Pedersen C, Turner JG, Shepherd GM, Tzounopoulos T. Mice with behavioral evidence of tinnitus exhibit dorsal cochlear nucleus hyperactivity because of decreased GABAergic inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7601–7606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100223108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulders WH, Robertson D. Hyperactivity in the auditory midbrain after acoustic trauma: dependence on cochlear activity. Neuroscience. 2009;164:733–746. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norena AJ, Eggermont JJ. Enriched acoustic environment after noise trauma abolishes neural signs of tinnitus. Neuroreport. 2006;17:559–563. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200604240-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norena AJ, Tomita M, Eggermont JJ. Neural changes in cat auditory cortex after a transient pure-tone trauma. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:2387–2401. doi: 10.1152/jn.00139.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien RJ, Kamboj S, Ehlers MD, Rosen KR, Fischbach GD, Huganir RL. Activity-dependent modulation of synaptic AMPA receptor accumulation. Neuron. 1998;21:1067–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak GD, Park TJ. The effects of GABAergic inhibition on monaural response properties of neurons in the mustache bat's inferior colliculus. Hear Res. 1993;65:99–117. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90205-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachel JD, Kaltenbach JA, Janisse J. Increases in spontaneous neural activity in the hamster dorsal cochlear nucleus following cisplatin treatment: a possible basis for cisplatin-induced tinnitus. Hear Res. 2002;164:206–214. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LE, Eggermont JJ, Caspary DM, Shore SE, Melcher JR, Kaltenbach JA. Ringing ears: the neuroscience of tinnitus. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14972–14979. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4028-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaette R, Kempter R. Development of tinnitus-related neuronal hyperactivity through homeostatic plasticity after hearing loss: a computational model. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:3124–3138. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaette R, Kempter R. Development of hyperactivity after hearing loss in a computational model of the dorsal cochlear nucleus depends on neuron response type. Hear Res. 2008;240:57–72. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield BR, Coomes DL. Pathways from auditory cortex to the cochlear nucleus in guinea pigs. Hear Res. 2006;216–217:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki S, Eggermont JJ. Changes in spontaneous firing rate and neural synchrony in cat primary auditory cortex after localized tone-induced hearing loss. Hear Res. 2003;180:28–38. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellwagen D, Malenka RC. Synaptic scaling mediated by glial TNF-alpha. Nature. 2006;440:1054–1059. doi: 10.1038/nature04671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano G. Too many cooks? Intrinsic and synaptic homeostatic mechanisms in cortical circuit refinement. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:89–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, Leslie KR, Desai NS, Rutherford LC, Nelson SB. Activity-dependent scaling of quantal amplitude in neocortical neurons. Nature. 1998;391:892–896. doi: 10.1038/36103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vater M, Habbicht H, Kossl M, Grothe B. The functional role of GABA and glycine in monaural and binaural processing in the inferior colliculus of horseshoe bats. J Comp Physiol A. 1992;171:541–553. doi: 10.1007/BF00194587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogler DP, Robertson D, Mulders WH. Hyperactivity in the ventral cochlear nucleus after cochlear trauma. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6639–6645. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6538-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Brozoski TJ, Caspary DM. Inhibitory neurotransmission in animal models of tinnitus: maladaptive plasticity. Hear Res. 2011;279:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Brozoski TJ, Turner JG, Ling L, Parrish JL, Hughes LF, Caspary DM. Plasticity at glycinergic synapses in dorsal cochlear nucleus of rats with behavioral evidence of tinnitus. Neuroscience. 2009;164:747–759. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Wang W, Tang ZQ, Xu TL, Chen L. Taurine acts as a glycine receptor agonist in slices of rat inferior colliculus. Hear Res. 2006;220:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans JS, Frankland PW. The acoustic startle reflex: neurons and connections. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1995;21:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(96)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharek MA, Kaltenbach JA, Mathog TA, Zhang J. Effects of cochlear ablation on noise induced hyperactivity in the hamster dorsal cochlear nucleus: implications for the origin of noise induced tinnitus. Hear Res. 2002;172:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C, Nannapaneni N, Zhou J, Hughes LF, Shore S. Cochlear damage changes the distribution of vesicular glutamate transporters associated with auditory and nonauditory inputs to the cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4210–4217. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0208-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JS, Kaltenbach JA. Increases in spontaneous activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the rat following exposure to high-intensity sound. Neurosci Lett. 1998;250:197–200. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JS, Kaltenbach JA, Godfrey DA, Wang J. Origin of hyperactivity in the hamster dorsal cochlear nucleus following intense sound exposure. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84:819–831. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]