Abstract

Stable isotope patterns in lichens are known to vary largely, but effects of substrate on carbon and nitrogen stable isotope signatures of lichens were previously not investigated systematically. N and C contents and stable isotope (δ15N, δ13C) patterns have been measured in 92 lichen specimens of Xanthoria parietina from southern Bavaria growing on different substrates (bark and stone). Photobiont and mycobiont were isolated from selected populations and isotopically analyzed. Molecular investigations of the internal transcribed spacer of the nuclear ribosomal DNA (ITS nrDNA) region have been conducted on a subset of the specimens of X. parietina. Phylogenetic analysis showed no correlation between the symbionts X. parietina and Trebouxia decolorans and the substrate, isotope composition, or geographic origin. Instead specimens grown on organic substrate significantly differ in isotope values from those on minerogenic substrate. This study documents that the lichens growing on bark use additional or different N sources than the lichens growing on stone. δ15N variation of X. parietina apparently is controlled predominantly by the mass fraction of the mycobiont and its nitrogen isotope composition. In contrast with mycobionts, photobionts of X. parietina are much more 15N-depleted and show less isotopic variability than mycobionts, probably indicating a mycobiont-independent nitrogen acquisition by uptake of atmospheric ammonia.

Keywords: Lichen symbiosis, mycobiont, photobiont, stable isotope, substrate, Xanthoria parietina, δ13C, δ15N

Introduction

Lichen growth is most notable on substrate, where almost no other organisms can grow, particularly due to low or absent water storage in the environment or where some factor like low temperature excludes higher plants (e.g., Garvie et al. 2008). Frequently lichens colonize nutrient-poor substrates, and especially N-limitation seems to be a considerable limiting factor (Crittenden et al. 1994; Nash 2008). In the last decades, the use of stable isotope techniques has become an important tool for ecophysiology and ecosystem research (e.g., Högberg 1997; Dawson et al. 2002; Post 2002), but was comparatively rarely applied to lichens. Krouse (1977) was among the first conducting stable isotope measurements on lichens and elucidated the uptake of atmospheric sulfur emissions using their δ34S values. Since then δ34S values were repeatedly used to study the response of lichens to atmospheric sulfur pollution (e.g., Wiseman and Wadleigh 2002).

The δ13C and δ15N values of lichens were in the focus of comparatively few studies so far. In general, δ13C values of lichens were found to vary broadly over a large range of habitats and species (e.g., Batts et al. 2004), but δ13C values of lichens appeared to be less variable within one lichen species, for example, Usnea antarctica Du Rietz, when growing in less diverse habitats not influenced by anthropogenic emissions, for example, Antarctic islands (Galimov 2000). As all lichen photobionts use the standard Rubisco (Máguas et al. 1995), the most notable influence on the δ13C value of lichens is the δ13C of the CO2 source and diffusion resistance, where the ratio of internal to external CO2 determines the final discrimination (Farquhar et al. 1989; Lakatos et al. 2007; Marshall et al. 2007). Consequently, factors influencing diffusion resistance will have significant effects on the δ13C value. One such factor is water content (e.g., Lange et al. 1988) and more positive δ13C values in plants are generally used as indicator for desiccation stress (e.g., epiphytes on thin vs. thick branches; Hietz et al. 2002). But this cannot be easily adopted to lichens due to different diffusion pathways of water vapor and CO2 in lichen thalli as opposed to higher plants, where both occur via the stomata. Nevertheless, more positive δ13C values in drier habitats have also been found for the lichens Ramalina celastri (Spreng.) Krog & Swinscow and R. subfraxinea Nyl. by Krouse & Herbert (1996, cited in Batts et al. 2004) and for Cladonia aggregata (Sw.) Nyl. by Batts et al. (2004), as well as for lichens collected in summer in France by Riera (2005). In contrast, Cuna et al. (2007) found a weak positive correlation between δ13C values of lichens (Cladonia fimbriata (L.) Fr. and Pseudevernia furfuracea (L.) Zopf) and monthly precipitation sums, but a negative correlation with relative humidity. Next to water availability the photosynthetic rate of lichens is limited by light (Palmqvist 2000; Lange et al. 2001) and consequently light levels influence photosynthesis and hence alter the CO2 gradient inside the lichen thallus as well.

Lichens utilize different N sources that may be distinguished by their isotopic fingerprints. On the one hand, the negative δ15N values observed in epiphytic and mat-forming lichens were explained by the uptake of NH4+ and NO3− from rainwater (Hietz et al. 2002; Ellis et al. 2003; Fogel et al. 2008), as these atmospheric sources have generally negative δ15N values (Moore 1977; Heaton 1986; Cornell et al. 1995). On the other hand, several lichen taxa have cyanobacterial photobionts and are known to be able to fix substantial amounts of atmospheric N2 (Forman 1975; Matzek and Vitousek 2003). Atmospheric nitrogen, the standard for presenting nitrogen stable isotope ratios, has a δ15N value of 0‰ by definition and N2-fixation is one of the few biological processes in the N-cycle with little or no isotopic fractionation (Hoering and Ford 1960; Fogel and Cifuentes 1993; Hübner 1986). Possibly the first record on δ15N values of lichens was given by Virginia and Delwiche (1982). These authors reported a positive δ15N value for the N2-fixing Lobaria oregana (Tuck.) Müll. Arg. (+0.8‰) and slightly negative values for the tripartite lichen L. pulmonaria (L.) Hoffm., the green-algal lichens Umbilicaria phaea Tuck., and Letharia vulpina (L.) Hue with values between −0.6 and −2.8‰. δ15N values of five tropical montane cloud forest canopy lichens ranged around −8 or −1.5‰, respectively, and were either among the highest or the lowest δ15N values and N concentrations of all investigated plants (Hietz et al. 2002). Albeit the lichens were not identified, Hietz et al. (2002) speculated that lichens with high N content and δ15N values closer to 0‰ can be attributed to N2-fixers. Nadelhoffer et al. (1996) reported δ15N values between −3 and 1.5‰ for unidentified lichens in a tundra ecosystem. A much wider δ15N range (−2.6 to −12.4‰) was found in unidentified lichens from Iceland (Wang and Wooller 2006). The reasons for lichen δ15N variability in most studies remain unexplained what is expected as more than 10 processes can alter δ15N values and these can hardly be separated in field studies (see Robinson 2001 for a review).

The morphologically complex foliose thalli of Xanthoria parietina (L.) Beltr. (Fig. 1) are the result of a long interaction history between the symbiotic myco- and photobiont. But our understanding of these interactions is still far from complete. While the movement of carbohydrates between lichen symbionts has been investigated rather intensively (for reviews see, e.g., Honegger 1991; Eisenreich et al. 2011), the knowledge on nitrogen (N) movement in lichens is much less. Except for lichens containing cyanobacteria, lichens depend on the deposition of nutrients directly on the thallus (Nash 2008). In tripartite lichens (containing cyanobacteria as well as green algae) like Peltigera aphthosa (L.) Willd. about 5% of the N fixed by the cyanobiont and released as ammonia was transferred by the fungus to the photobiont Coccomyxa, thus covering large parts of its N requirements (Rai et al. 1981; Rai 1988). For the pathway of nitrogen acquisition by the green-algal photobiont, at least three alternative concepts exist. Crittenden (1989) argues for a nitrogen acquisition mainly from living fungal cells and only a minority through the external fungal tissue, based on the findings in Peltigera mentioned above, and the observed nutrient movement in decomposing Cladonia mats. On the other hand, Honegger (1991) and Richardson (1999) argue that in foliose green-algal lichens like Xanthoria, lichen fungi and algae compete for dissolved nutrients in the apoplast, given the hydrophobic interface – no capillary water is present on the outer side of the hydrophobic wall surfaces of the thalline interior. As a third pathway, a gaseous exchange at the photobiont and mycobiont surface might occur. This would not be negatively affected by any hydrophobins. The analysis of nitrogen isotope ratios of lichen symbionts may shed some light on possible nutrient relationships and competition.

Figure 1.

Xanthoria parietina growing at one of the sites of investigation (Oberschleißheim near Munich). Inset shows a close-up of the thalli (dimensions correspond to 2.5 × 2.7 cm in reality).

The aim of this study was the investigation of the nitrogen and carbon stable isotope composition of green-algal lichens with respect to intraspecies variability due to different substrates and sites. The isotopic signatures of photobiont and mycobiont have also been investigated separately in order to elucidate their respective contributions to the symbiont's isotope signal and elemental contents. The isotopic results presented give information about nutrient availability, different nitrogen sources used, and symbiotic interactions.

Materials and Methods

Sites and sampling

All samples were collected in Bavaria, southern Germany, between 11° 01′ E to 11° 56′ E longitude and 48° 14′ N to 47° 32′ N latitude, detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details for the collecting localities of the green-algal lichen Xanthoria parietina used for isotopic analyses

| Locality | Altitude | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|

| Oberschleißheim | ca. 500 m a.s.l. | 11° 35′ E, 48° 14′ N |

| München, Fasanerie (FA) | ca. 525 m a.s.l. | 11° 30′ E, 48° 07′ N |

| München, Landsberger Str. (LS) | ca. 525 m a.s.l. | 11° 30′ E, 48° 07′ N |

| München, Westpark (WP) | ca. 525 m a.s.l. | 11° 30′ E, 48° 07′ N |

| Planegg | ca. 550 m a.s.l. | 11° 25′ E, 48° 07′ N |

| Gauting | ca. 580 m a.s.l. | 11° 24′ E, 48° 03′ N |

| Maising | ca. 640 m a.s.l. | 11° 17′ E, 47° 58′ N |

| Pähl | ca. 600 m a.s.l. | 11° 11′ E, 47° 55′ N |

| Weilheim | ca. 560 m a.s.l. | 11° 08′ E, 47° 49′ N |

| Fischbachau | ca. 780 m a.s.l. | 11° 56′ E, 47° 42′ N |

| Unterammergau | ca. 800 m a.s.l. | 11° 01′ E, 47° 36′ N |

| Farchant | ca. 670 m a.s.l. | 11° 08′ E, 47° 32′ N |

Taxon analysis with molecular methods

Xanthoria parietina belongs to a species group that contains two additional species, namely X. aureola (Ach.) Erichsen and X. calcicola Oksner. These species differ in their substrate choice, with X. aureola growing on (seashore) rocks, X. calcicola growing on calcareous rocks and walls (only rarely on tree bark) and X. parietina having the widest substrate range growing on all these substrates. As incorrect species assignment might affect a study on the influence of the substrate on stable isotope composition within one species, unequivocal taxa assignment has been considered an important issue. Moreover, genetic data provides important information on intraspecies variability, which likewise adds important information for the analysis of the stable isotope composition. Thus, molecular investigations of the ITS nrDNA region have been conducted on selected samples in addition to careful examination of reliable morphological characters to assure proper species assignment (see Lindblom and Ekman 2005, 2007 for details).

DNA has been isolated using the PCR Template Preparation Kit from Roche (Mannheim, Germany; Cat No. 11 796 828 001) following the manufacturers protocol, but grinding the lichen carefully using a micropestle in liquid nitrogen before adding the lysis buffer. 10–50 mg of air-dried lichen material has been used for the DNA extraction. A volume of 1 μL of a 1:10 dilution of the obtained DNA solution has been used for PCR using algal primers as described by Beck and Koop (2001) and fungal primers as described in Dolnik et al. (2010) but using the newly designed primer ITS4m (GCC GCT TCA CTC GCC GTT AC) instead of ITS4. All PCR products were purified with the Macherey-Nagel columns (Macherey-Nagel, Düren) and labelled with Big Dye Terminator v3.1 Kit (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). Cycle sequencing was 30 cycles of: 95°C for 10 sec, 50°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 3 min. Postsequencing cleanup was performed using gelfiltration with Sephadex G-50 Superfine (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden; Cat. No. 17-0041-01) following the manufacturer's protocol. Forward and reverse strand sequences were detected in an ABI 3730 48 capillary automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems) and assembled using the Staden package (http://staden.source forge.net/). Double-stranded sequences were aligned manually jointly with representative sequences obtained from Genbank using Gendoc (http://www.nrbsc.org/downloads/). All sequences used are detailed in Table 2 (photobionts) and Table 3 (mycobionts). The resulting data sets were analyzed under the maximum parsimony (MP) and maximum likelihood (ML) criterion using the program PAUP Version 4.0b10 (Swofford 2000). All characters of the ITS1 and ITS2 region, but not the 5.8S nrDNA, have been included for these calculations. As outgroup, the sequences of T. asymmetrica T. Friedl & G. Gärtner (strain SAG 48.88), T. gigantea (Hildreth & Ahmadjian) G. Gärtner (strain UTEX 2231), T. incrustata Ahmadjian ex G. Gärtner (strain UTEX 784), and T. showmanii (Hildreth & Ahmadjian) G. Gärtner (strain UTEX 2234) have been used for the photobionts and sequences of X. aureola for the mycobionts. To select the nucleotide substitution model and parameters for the ML searches, a hierarchical likelihood ratio test was carried out as implemented in jModelTest 0.1.1 (Guindon and Gascuel 2003; Posada 2006, 2008). The optimal model was selected under the Akaike information criterion (photobiont data set: TVM+G, −ln: 1835.6953; mycobiont data set: TrN+G, −ln: 958.3756). Heuristic searches have been conducted with 1000 (MP) or 500 (ML) random addition sequence (RAS) replicates, tree bisection reconnection (TBR) branch swapping, Multrees option in effect, saving all trees and collapsing branches with maximum length equal to zero. Statistical support in all trees was assessed by bootstrap analysis (BS; Felsenstein 1985) using 1000 (MP) or 500 (ML) bootstrap replicates with five random-addition sequences per replicate, but multree option not in effect.

Table 2.

Sequences used in the phylogenetic analysis of photobiont sequences from Xanthoria parietina

| Taxon | Voucher | Substrate | Locality | GenBank No. ITS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trebouxia aggregata | UTEX180 | JF831903 | ||

| T. arboricola | SAG 219–1a | Z68705 | ||

| T. asymmetrica | SAG 48.88 | AJ249565.1 | ||

| T. crenulata | CCAP219/2 | JF831904 | ||

| T. decolorans | UTEX 781 | FJ626728.1 | ||

| T. gigantea | UTEX 2231 | AF242468.1 | ||

| T. incrustata | UTEX 784 | AJ293795.1 | ||

| T. showmanii | UTEX 2234 | AF242470.1 | ||

| T. decolorans ex Xanthoria parietina | M–0102151 | Bark | Germany, Maising | JF831923 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102152 | Bark | Germany, München | JF831914 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102304 | Bark | Germany, Pähl | JF831921 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102304 | Bark | Germany, Pähl | JF831922 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102305 | Stone | Germany, Pähl | JF831919 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102305 | Stone | Germany, Pähl | JF831920 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102305 | Stone | Germany, Pähl | JF831905 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102306 | Stone | Germany, Pähl | JF831915 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102307 | Bark | Germany, Pähl | JF831917 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102307 | Bark | Germany, Pähl | JF831906 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102308 | Stone | Germany, Fischbachau | JF831912 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102309 | Bark | Germany, Fischbachau | JF831913 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102316 | Stone | Germany, Gauting | JF831916 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102325 | Bark | Germany, München | JF831909 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102327 | Stone | Germany, Pähl | JF831908 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102328 | Bark | Germany, Pähl | JF831907 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102916 | Bark | Germany, Farchant | JF831910 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102919 | Stone | Germany, Farchant | JF831911 |

| T. decolorans ex X. parietina | M–0102925 | Bark | Germany, Gauting | JF831918 |

New sequences are marked in bold.

Table 3.

Sequences used in the phylogenetic analysis of mycobiont sequences from Xanthoria parietina

| Taxon | Voucher (herbarium) | Substrate | Locality | GenBank No. ITS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X. aureola no. 16 | 2002 Coppins s.n. (E) | Stone | Norway, Hordaland; Sweden, Bohuslän; Scotland, East Lothian | AY438275 |

| X. aureola no. 17 | 2001 Lindblom X188 (priv. herb.) | Stone | Sweden, Skåne | AY438276 |

| Xanthoria parietina no. 16 | 2003 L. Lindblom 14/445 (BG) | Bark | Sweden, Mölle chapel | DQ472227 |

| X. parietina no. 15 | 2003 L. Lindblom 13/400 (BG) | Bark | Sweden, Kullaberg lighthouse | DQ472226 |

| X. parietina no. 14 | 2002 L. Lindblom 10/315 (BG) | Bark | Sweden, Kullaberg, Ransvik | DQ472225 |

| X. parietina no. 13 | 2002 L. Lindblom 9/266 (BG) | Stone | Sweden, Arild, E | DQ472224 |

| X. parietina no. 12 | 2002 L. Lindblom 7/222 (BG) | Bark | Sweden, Hovvalla; Kullaberg lighthouse | DQ472223 |

| X. parietina no. 11 | 2002 L. Lindblom 7/216 (BG) | Bark | Sweden, Hovvalla; Mölle chapel | DQ472222 |

| X. parietina no. 10 | 2002 L. Lindblom 7/212 (BG) | Bark | Sweden, Hovvalla | DQ472221 |

| X. parietina no. 9 | 2002 L. Lindblom 7/211 (BG) | Bark | Sweden, Hovvalla; Kullaberg lighthouse; Mölle chapel | DQ472220 |

| X. parietina no. 8 | 2002 L. Lindblom 7/205 (BG) | Bark | Sweden, Hovvalla | DQ472219 |

| X. parietina no. 7 | 2002 L. Lindblom 7/204 (BG) | Bark | Sweden, Hovvalla; Kullaberg lighthouse | DQ472218 |

| X. parietina no. 6 | 2002 L. Lindblom 7/203 (BG) | Bark | Sweden, Hovvalla; Kullaberg lighthouse; Mölle chapel | DQ472217 |

| X. parietina no. 5 | 2002 L. Lindblom 7/201 (BG) | Bark | Sweden, Hovvalla; Kullaberg lighthouse; Mölle chapel | DQ472216 |

| X. parietina no. 4 | 2002 L. Lindblom 7/199 (BG) | Bark | Sweden, Hovvalla; Kullaberg lighthouse; Mölle chapel | DQ472215 |

| X. parietina no. 3 | 2002 L. Lindblom 7/197 (BG) | Bark | Sweden, Hovvalla; Kullaberg lighthouse; Mölle chapel | DQ472214 |

| X. parietina no. 2 | 2002 L. Lindblom 6/167 (BG) | Bark and Stone | Sweden, Hovs Hallar; Kullaberg lighthouse; Kullaberg, Ransvik; Mölle chapel; Arild, Nabben | DQ472213 |

| X. parietina no. 1 | 2002 L. Lindblom 6/163 (BG) | Bark and Stone | Sweden, Hovs Hallar; Hovvalla; Kullaberg, Ransvik; Mölle chapel; Arild, Nabben; Arild, E | DQ472212 |

| X. parietina | M–0102305 | Stone | Germany, Pähl | JF831884 |

| X. parietina | M–0102307 | Bark | Germany, Pähl | JF831885 |

| X. parietina | M–0102328 | Bark | Germany, Pähl | JF831886 |

| X. parietina | M–0102327 | Stone | Germany, Pähl | JF831887 |

| X. parietina | M–0102325 | Bark | Germany, München | JF831888 |

| X. parietina | M–0102916 | Bark | Germany, Farchant | JF831889 |

| X. parietina | M–0102919 | Stone | Germany, Farchant | JF831890 |

| X. parietina | M–0102308 | Stone | Germany, Fischbachau | JF831891 |

| X. parietina | M–0102309 | Bark | Germany, Fischbachau | JF831892 |

| X. parietina | M–0102306 | Stone | Germany, Pähl | JF831893 |

| X. parietina | M–0102316 | Stone | Germany, Gauting | JF831894 |

| X. parietina | M–0102307 | Bark | Germany, Pähl | JF831895 |

| X. parietina | M–0102925 | Bark | Germany, Gauting | JF831896 |

| X. parietina | M–0102151 | Bark | Germany, Maising | JF831897 |

| X. parietina | M–0102305 | Stone | Germany, Pähl | JF831899 |

| X. parietina | M–0102305 | Stone | Germany, Pähl | JF831900 |

| X. parietina | M–0102304 | Bark | Germany, Pähl | JF831901 |

| X. parietina | M–0102304 | Bark | Germany, Pähl | JF831902 |

| X. parietina | M–0102152 | Bark | Germany, München | JF831898 |

New sequences are marked in bold.

Stable isotope analyses

Isotope analyses were performed on 92 samples of lichens and 10 isolated lichen symbiont populations, all collected in Bavaria, southern Germany. Before analysis, external debris was carefully removed from the thalli. All isotopic analyses were performed with a Delta Plus (Thermo-Finnigan, Bremen, Germany) isotope-ratio mass spectrometer coupled with a ConFlo-II interface (Thermo-Finnigan) to an elemental analyzer (NC 2500, Carlo Erba, Italy). Samples have been ground using a mortar and pestle. The resulting powder was combusted at 1080°C with excess oxygen and the sample gases were purified and separated according to standard methods (Mayr et al. 2011). Nitrogen (δ15N) and carbon (δ13C) stable isotopes are given in the common δ-notation calculated as δ = (Rsample/Rstandard − 1) × 1000 with Rsample and Rstandard as isotope ratios (R) of the heavy isotope to the light isotope of the sample and an international standard, respectively. Samples are reported versus the international standards atmospheric N2 (AIR) for nitrogen and Vienna-Pee-Dee Belemnite (V-PDB) for carbon and are given in ‰. Carbon and nitrogen contents of the samples were determined from the peak area of the mass spectrometer analyses weighted by the sample's mass. For calibration, the elemental standards cyclohexanone-2,4-dinitrophenyl-hydrazone (C12H14N4O4) and atropine (C17H23NO3) (both Thermo Quest, Rodano, Italy) were used. Statistical tests for the stable isotope measurements were carried out with the software PASW Statistics 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Isolation of myco- and photobiont

Isolation was conducted as detailed in Fontaniella et al. (2000) for Evernia prunastri (L.) Ach. Basically, algal and fungal cells are separated in a sucrose-KI gradient. A total of 200 mg of cleaned, air-dried X. parietina (equating material from five lichen thalli) have been homogenized in a high-performance dispenser (Miccra D-8; Fa. Miccra, Germany). After separation, the algal/fungal pellets have been washed three times with 10 mmol/L phosphate buffer pH 7.2. Contamination with the other symbiont was microscopically determined to be less than 3%.

Mass balance calculations

Concentration-dependent mass balance mixing models (modified from Phillips and Koch 2002) were applied to evaluate the mass percentages (wt%) of photo- and mycobionts in selected lichens. The δ15N values and elemental contents of a lichen colony and the photobionts and mycobionts separated from a part of the population were needed for this calculation. The mass fractions fP and fM of photobionts (P) and mycobionts (M), respectively, in the lichen (L) were calculated from the δ15N values of P, M, L (δ15NP, δ15NM, δ15NL), and their nitrogen concentrations [N]P, [N]M using the following equations:

| (1) |

where δ15NM, δ15NP denotes the isotopic composition of mycobiont and photobiont, respectively, and fM,N and fP,N their fractional nitrogen contributions to total lichen nitrogen. Although the above values can be measured, the fractional biomass contributions of mycobiont (fM,B) and photobiont (fP,B) have to be calculated with the following equations.

The fractional nitrogen and biomass contributions of photo- and mycobiont sum up to 1:

| (2) |

| (3) |

N contents of myco- and photobiont [N]M, [N]P are incorporated in the following equations

| (4) |

| (5) |

Substituting equations (4) and (5) in equation (1) gives

| (6) |

According to equation (3), fP,B can be substituted by

| (7) |

Thereafter, equation (6) only contained measured variables except of fM,B. The optimum value of fM,B was found by iterative fitting so that the calculated δ15NL value corresponded to the actually measured value of the total lichen.

Results

Relation between substrate and stable isotopes and element contents of Xanthoria parietina

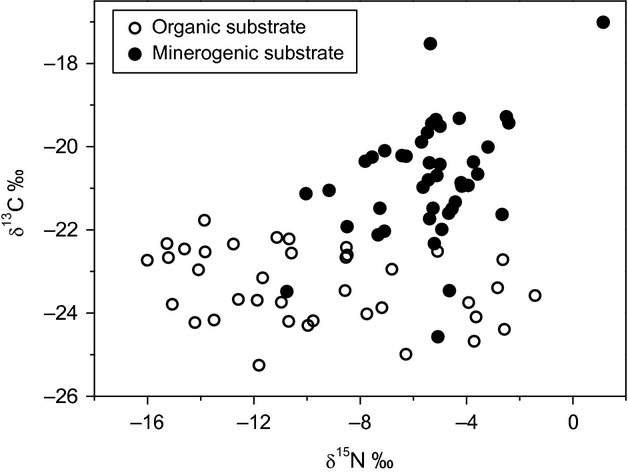

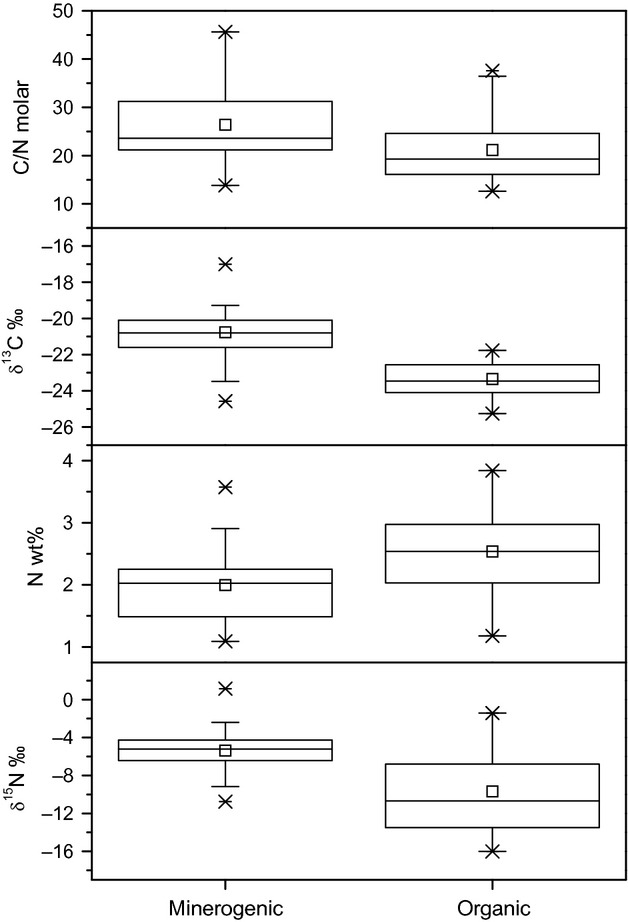

The isotope values of X. parietina show a large variability ranging from −16.0 to 1.2‰ for δ15N and from −17.0 to −25.3‰ for δ13C (Fig. 2). δ13C values separate the lichens from both substrates. δ15N values of bark lichens have a very broad range while those of lichens on minerogenic ground cover only part of that range, but do fall completely within values for bark samples, possibly indicating an extra depleted source for bark lichens that is not available to rock lichens. Specimens that were growing on organic substrate (bark, wood, moss; N = 38) have significantly different C/N ratios, N contents, δ13C, and δ15N values than those grown on minerogenic substrate (concrete, stone, brick, metal; N = 44) (Mann–Whitney test, P < 0.01; Fig. 3). In contrast, C contents were not significantly different between Xanthoria growing on minerogenic versus organic substrates. Thus, higher C/N ratios for specimens growing on minerogenic substrate can be attributed mainly to their lower N contents. Xanthoria from minerogenic substrates are on average 4.3 and 2.6‰ enriched in δ15N and δ13C, respectively, relative to those growing on organic substrates. The range of δ15N values for Xanthoria from organic substrate is larger compared with those growing on minerogenic ground (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

δ13C versus δ15N values of 82 Xanthoria specimens distinguished in those grown on minerogenic (filled dots) and those grown on organic substrate (open circles) from various collection sites in southern Germany.

Figure 3.

Box-and-whisker plot comparing isotopic compositions, N content, and C/N ratios of Xanthoria parietina grown on minerogenic and organic substrate. Whiskers represent the lowest and highest dates within the 1.5 interquartile ranges. Crosses are 1st and 99th percentiles, respectively, and short lines the most extreme values. Means are given by open squares.

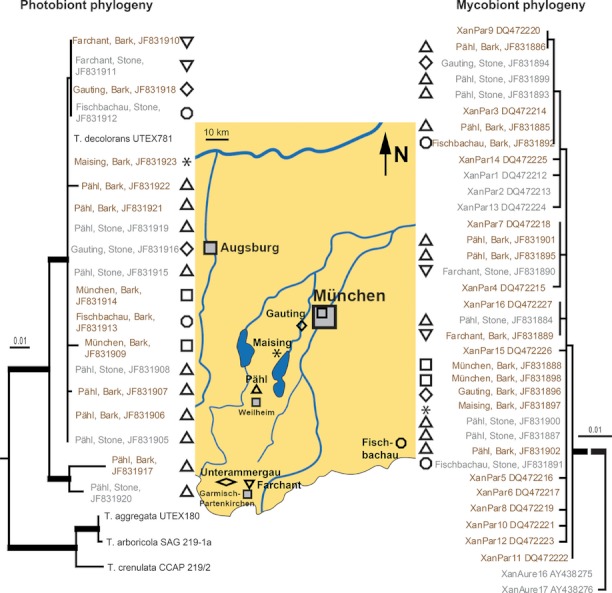

Genetic homogeneity of Xanthoria parietina

In order to secure genetic homogeneity of the investigated material, 19 samples of X. parietina have been analyzed on the molecular level, randomly chosen to cover all substrates, isotope values, and various localities (Pähl, Fischbachau, Farchant, Gauting, and München). The ITS nrDNA region has been sequenced and analyzed for both bionts separately together with representative sequences from GenBank (Table 2 and 3). MP and ML analysis yielded only one tree each with identical tree topologies, indicating highly reliable results. The sequences of all lichen mycobionts group with high statistical support together with other sequences from X. parietina mycobionts obtained from specimens collected in Sweden and Norway by Lindblom and Ekman (2005, 2007), corroborating the morphological determinations (Fig. 4, right-hand side). All photobiont sequences group with high statistical support with the sequence of the authentic strain of Trebouxia decolorans Ahmadjian, UTEX 781 (isolated from the lichen Amandinea punctata (Hoffm.) Coppins & Scheid. collected in the United States of America). The morphologically similar species T. aggregata (P. A. Archibald) G. Gärtner, T. arboricola Puym., and T. crenulata P. A. Archibald form the highly supported sister group. Thus, all photobionts of the investigated lichen thalli belong to only one algal species, T. decolorans (Fig. 4, left-hand side). Differences in the sequences do not show any correlation with the substrate or isotope composition, nor with the geographic origin of the specimen, indicating again that specimens of one and the same species have been analyzed (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Molecular analysis of the nrITS region of selected specimens of Xanthoria parietina. Shown are the single most likely trees of a ML search regarding the nrITS sequences of the photobionts (left-hand side) and mycobionts (right-hand side), respectively, analyzed together with selected sequences from Genbank. A MP search resulted in one tree each with identical tree topology. Branches with high statistical support (≥95% bootstrap support for MP and ≥75% bootstrap support for ML) are indicated by thick lines. For the mycobionts, the line connecting the X. parietina sequences has been shortened due to practical reasons, which is indicated by the dashed line. For the photobionts, the distance to the sequences used as outgroup (see Materials and Methods section for details) is not shown. Specimens growing on bark are given in brown color; gray color is used for the specimens from rocks. In the center, a map of southern Bavaria indicates the geographic location of the sampling localities characterized by the respective symbols. Grey filled symbols represent major cities.

Isotopic differences between photo- and mycobiont of lichens

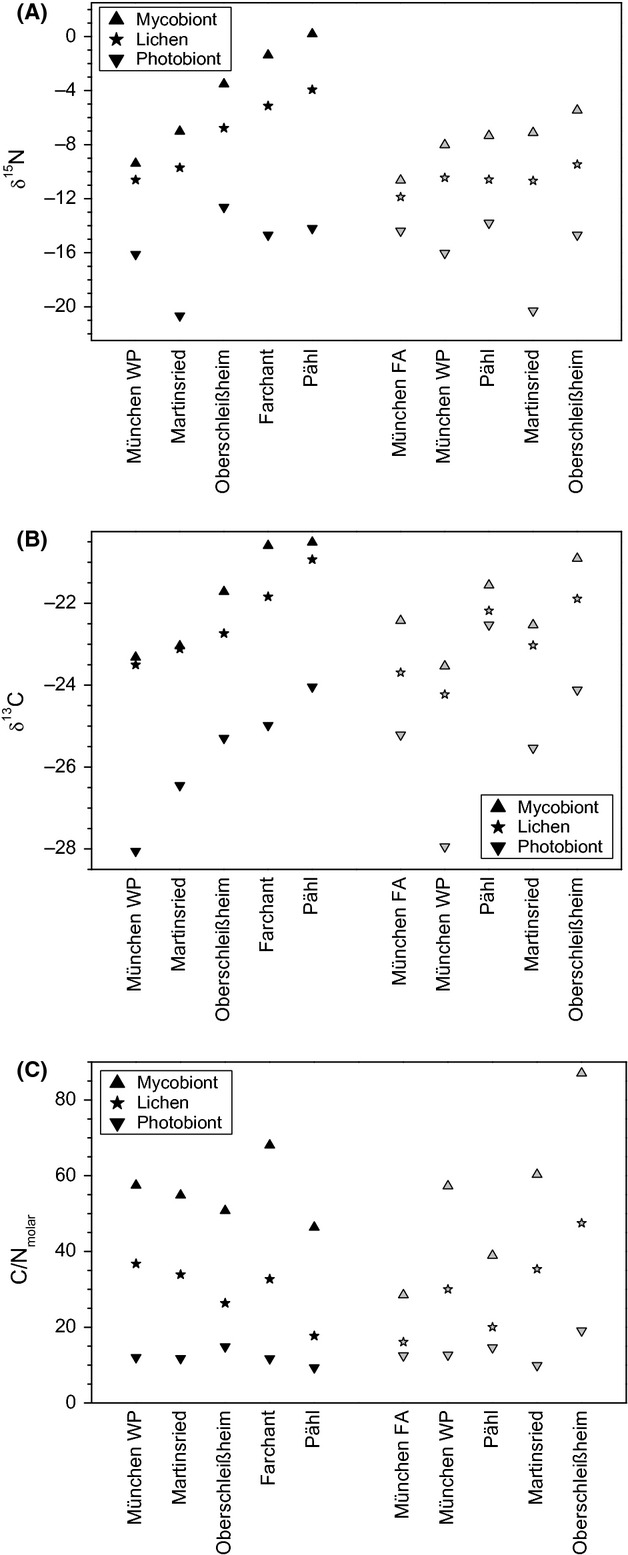

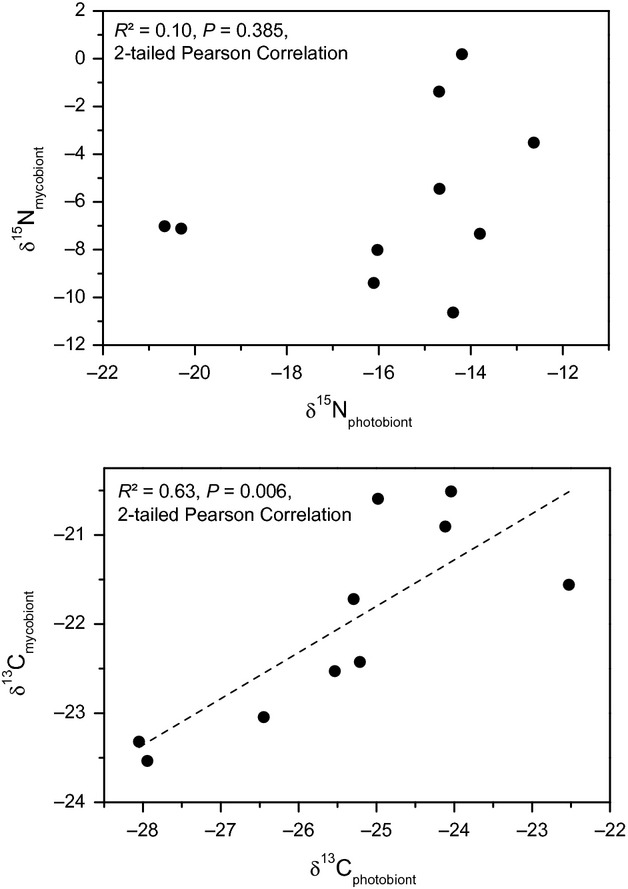

Photo- and mycobiont of 10 populations of X. parietina were separated from five lichen thalli of each population. Their nitrogen and carbon isotope composition as well as their N content were analyzed. The δ15N results show rather little isotopic differences for the Xanthoria photobionts with values ranging between −12.6 and −20.7‰ independent of substrate (averages −15.7 ± 3.1‰ and −15.8 ± 2.6‰ for minerogenic and organic substrates, respectively). Mycobionts of Xanthoria, however, were always more 15N enriched (total range: 0.2 to −10.6‰) and showed larger differences depending on substrate (Fig. 5A). Mycobionts of populations grown on minerogenic substrates had higher δ15N values (−4.2 ± 4.0‰) than those grown on tree bark (−7.7 ± 1.9‰). δ13C values range from −28.1 to −22.5‰ (mean value −25.4 ± 1.7‰) for photobionts and from −23.5 to −20.5‰ (mean value −22.0 ± 1.1‰) for mycobionts. As for δ15N, mycobionts of Xanthoria were always relatively enriched in the heavy isotope relative to the photobiont (Fig. 5B). C/N values were lower and less variable for photobionts (mean value 12.9 ± 2.8) than for mycobionts (mean value 55.0 ± 16.0) due to a higher and more stable N content (Fig. 5C). δ15N values of photobionts and mycobionts are not correlated, while δ13C values are (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Nitrogen (A) and carbon (B) isotopic composition as well as C/N ratios (C) of 10 Xanthoria parietina populations and of myco- and photobionts separated from the same samples. Black symbols represent values from lichens that grew on minerogenic, gray symbols those that grew on organic substrates.

Figure 6.

δ15N values of the lichens from Figure 5A, photobiont plotted versus mycobiont. δ13C values of the lichens from Figure 5B, photobiont plotted versus mycobiont.

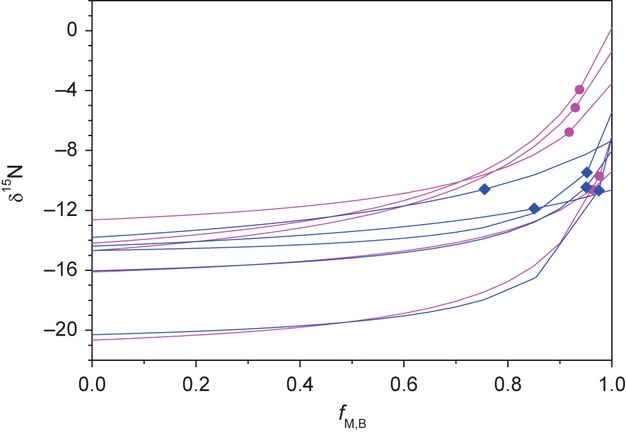

The fraction of mycobiont biomass (fM,B) was modelled using equation (6). The modelled nonlinear mixing lines demonstrate that the lichen δ15N increases with increasing fM,B (Fig. 7). The fM,B of each sample was determined by fitting the model to the actually measured lichen δ15N. The results show that fM,B was similar (90 ± 9%) for the Xanthoria selection from organic as for Xanthoria from minerogenic substrate (94 ± 2%). Based on the available dataset, the higher δ15N means of Xanthoria grown on minerogenic compared with organic substrate in Figure 2 can be attributed to (1) higher δ15N values of their respective mycobionts and (2) a higher fraction of mycobiont biomass contributing to the total lichen biomass. However, the populations from which the bionts were separated demonstrate that there is an overlap in the isotopic composition as well as in the mycobiont biomass fraction between Xanthoria populations grown on different substrates.

Figure 7.

Modelled δ15N values of the lichens from Figure 5A with increasing fraction of mycobiont biomass (fM,B) based on a concentration-dependent two-end-member mixing model. End points of mixing lines represent δ15N values of photo- and mycobionts, respectively. The actually measured δ15N values of lichens are given as diamonds on the respective mixing lines (symbols as in Fig. 5A). Colors differentiate lichens grown on minerogenic (magenta dots) and organic (blue diamonds) substrate.

Discussion

Substrate-specific δ13C variability: microclimate or respiratory CO2?

The δ13C values of X. parietina from minerogenic substrate show significantly higher δ13C values than those grown on organic substrate (Fig. 3). Inorganic carbon acquisition in lichens is accomplished by the photobiont and, thus, dependent on moisture and light availability (Palmqvist 2000). The observed δ13C differences therefore could have been evoked either by different microclimatic conditions on both substrate types or isotope effects due to uptake of isotopically different CO2 sources.

Increased δ13C values in drier habitats have been found for lichens (Batts et al. 2004). Therefore, the higher water storage capability of organic in contrast with minerogenic substrates is a likely reason for the observed lower δ13C values of lichens growing on it. However, very high water contents in lichens (suprasaturation) can increase the CO2 diffusion resistance for lichens (Lange et al. 2001). This diffusion limitation decreases the fractionation by 3−4‰ at highest suprasaturation (Máguas et al. 1995) and therefore will result in higher δ13C values. Apparently this effect plays a minor role for substrate-related δ13C differences investigated in our study.

Besides the water status, the uptake of respiratory CO2 can be a second cause for lower δ13C values of lichens growing on organic substrates. Lichens growing in the canopy or close to the soil potentially assimilate CO2 from plant and soil respiration (Broadmeadow et al. 1992; Máguas et al. 1993, 1995), but also CO2 from bark respiration could be taken up by corticolous lichens. This “canopy effect” could shift δ13C to more negative values, as the isotopic composition of respired CO2 is in the δ13C range of organic matter and thus much more negative (−19 to −32‰; Pataki et al. 2003) than atmospheric CO2 (−8‰ on average). The more negative δ13C values of lichens growing on organic substrate, thus, could be related to respiratory CO2. Another source for differences in δ13C values in lichen thalli from bark versus rock substrates is additional organic carbon uptake as it is well known that both lichen bionts readily take up organic carbon (Ahmadjian 1965). Whether uptake of respiratory CO2, light level, water availability, or additional organic carbon uptake on different substrates, or a combination of these factors, are responsible for the observed δ13C differences remains, however, the object of further studies.

Causes for substrate-specific δ15N variability

The N content of lichen thalli is dependent on the nutritional status of the lichens and might be limiting for growth and distribution of lichens (Crittenden et al. 1994; Palmqvist et al. 2002; Nash 2008). When nitrogen is scarce, lichens were found to invest relatively more N in photosynthetically active substances (Chl a and Rubisco) instead of fungal substances (chitin; Palmqvist et al. 1998). At least three possible causes may be responsible for the observed substrate-specific differences in δ15N values: Preferential selection of 14N in short periods of uptake may lead to 15N depletion. These N-uptake periods may be temporary due to short-dated wetting (and thus transient metabolic activity) or short periods of nutrient availability. Second, different N sources, like nitrate (liquid) or ammonia (gaseous) may lead to different δ15N values due to higher fractionation in the gaseous phase. Third, transfer of organic nitrogen, for example, from the mycobiont to the photobiont may result in 15N depletion in a similar way as in mycorrhizal symbiosis (Hobbie and Hobbie 2008), resulting in increased 15N depletion of the photobiont and less depletion in the mycobiont. This process would be most likely to occur on bark where organic nitrogen sources in the runoff water are available. Thus, the overall higher δ15N values of X. parietina that grew on minerogenic substrate may reflect the lower nitrogen availability (Fig. 3). Nitrogen availability and demand determine the 15N discrimination in plants (Evans 2001). Lower nitrogen availability, as supposed for the lichens growing on minerogenic substrates, leads to a lower discrimination and hence to higher δ15N values of lichen thalli. The same effect as in the lichen X. parietina was observed in individual thalli of Anaptychia ciliaris and Phaeophyscia orbicularis growing on bark or stone, respectively (data not shown). With respect to the N-content of the substrate the stone surfaces contained no measurable N amounts. Measurements for the δ15N values of bark ranged from −0.7 to −4.6‰ (mean of −2.7 ± 1.6‰), again providing evidence for isotope discrimination by the lichens given their much more negative values (−9.7 ± 4.2‰ for Xanthoria grown on bark). Nevertheless, as lichens are not single organisms, the δ15N values of the symbionts need to be taken into account. Our analysis showed that the higher δ15N values of Xanthoria grown on minerogenic compared with organic substrate can be attributed to (1) higher δ15N values of their respective mycobionts and (2) a higher fraction of mycobiont biomass contributing to the total lichen biomass (Figs. 5, 7). A higher photobiont biomass in the specimens with higher N content is well in agreement with data presented by Dahlman et al. (2003) for Hypogymnia physodes (L.) Nyl. and Platismatia glauca (L.) W. L. Culb. & C. F. Culb.

Isotopic discrimination between lichen symbionts

δ15N values of the photobiont T. decolorans are independent from and always more negative than those of the associated mycobiont (Figs. 5A, 6). If the photobiont would gain its N primarily from the mycobiont, one would expect a correlation between these values as the mycobiont N would be the pool for the photobiontal N. This applies to both, active N transport through the fungus to the alga and N leakage from the fungus to the alga. Such a correlation only exists for δ13C values (Figs. 5B, 6). A transport of the sugar alcohol ribitol from the Trebouxia photobiont to the Xanthoria mycobiont is well established (Richardson and Smith 1968; see Eisenreich et al. 2011 for a review) and can easily explain the observed correlation. The independence of the δ15N values could be interpreted as further evidence that the Trebouxia photobiont is able to compete successfully with the mycobiont for available nitrogen like nitrate as discussed by Dahlman et al. (2004) due to indirect evidence by low nitrate uptake rates in bipartite cyanobacterial lichens as compared to the tripartite lichens, but both with similar nitrogen content. The latter showed a significant higher nitrate assimilation that might have primarily been conducted by the green algal partner Coccomyxa. Nevertheless, Pavlova and Maslov (2008) demonstrated the inability of nitrate uptake for the lichenized Trebouxia photobiont of Parmelia sulcata Taylor. Moreover, δ15N values of nitrate in rain in central Europe ranged between +2.4 and −6.5‰ (Freyer 1991) and thus did not reach such negative values as measured in T. decolorans in this study (−15.8 ± 2.7‰). Ammonia dissolved in rain (ammonium) is known to be more depleted in 15N, ranging from −5.6 to −8.6‰ measured in the United Kingdom (Heaton et al. 1997). Even more negative values are reported for atmospheric ammonia around −10‰ (Erskine et al. 1998; Tozer et al. 2005). The latter authors also demonstrated, that diffusion into the tissue of lithophytes (as simulated by an acidified mat of glass fibers) results in a further 15N depletion of 4.0–5.5‰. Thus, the observed photobiontal δ15N values between −12.6 and −20.7‰ are very well in accordance with the uptake of atmospheric ammonia as primary N source by T. decolorans. This may explain the nitrophilic nature of X. parietina, as no bird droppings have been found at the investigated sites. If it is true for lichen algae in general remains to be tested. While atmospheric ammonia may not be the only nitrogen source, the data presented in this study suggest that it is the most important N source for T. decolorans. In accordance, ammonia is the most abundant N species in the atmosphere in remote as well as anthropogenic influenced areas (Crittenden 1998; Krupa 2003). Lichen mycobionts, in contrast, can use additional N sources, most notably NHx and NOx species from rainfall as demonstrated by the nitrate uptake of the P. sulcata mycobiont (Pavlova and Maslov 2008). The use of these more 15N-enriched sources than ammonia is reflected by the more positive δ15N values of the X. parietina mycobiont. The mycobiont-independent photobiontal δ15N values are thus best explained by a mycobiont-independent N uptake of the photobiont of atmospheric ammonia. In X. parietina, and possibly in more green-algal lichens, only a very limited (if at all) N transfer seems to occur from the mycobiont to the green-algal photobiont which has been shown for tripartite lichens harboring cyanobacteria and green algae (Rai et al. 1983).

Acknowledgments

We thank Markus Oehlerich, Kati Böhm, Andrea Hofmann, and Laurentius Sauer for assistance with sample preparation. We are grateful to the GeoBio-Center at the LMU Munich for financing a part of the laboratory work. The article profited from the helpful comments of Peter Crittenden and two anonymous referees on an earlier manuscript version.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Ahmadjian V. Lichens. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1965;19:1–20. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.19.100165.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batts JE, Calder LJ, Batts BD. Utilizing stable isotope abundances of lichens to monitor environmental change. Chem. Geol. 2004;204:345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Koop HU. Analysis of the photobiont population in lichens using a single-cell manipulator. Symbiosis. 2001;31:57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Broadmeadow MSJ, Griffiths H, Maxwell C, Borland AM. The carbon isotope ratio of plant organic material reflects temporal and spatial variations in CO2 within tropical forest formations in Trinidad. Oecologia. 1992;89:435–441. doi: 10.1007/BF00317423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell S, Rendell A, Jickells T. Atmospheric inputs of dissolved organic nitrogen to the oceans. Nature. 1995;376:243–246. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PD. Nitrogen relations of mat-forming lichens. In: Body L, Marchant R, Read DJ, editors. Nitrogen, phosphorous and sulphur utilization by fungi. NY: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1989. pp. 243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PD. Nutrient exchange in an Antarctic macrolichen during summer snowfall–snow melt events. New Phytol. 1998;139:697–707. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PD, Kalucka I, Oliver E. Does nitrogen limit the growth of lichens? Cryptogam. Bot. 1994;4:142–155. [Google Scholar]

- Cuna S, Balas G, Hauer E. Effects of natural environmental factors on δ13C of lichens. Isot. Environ. Health Stud. 2007;43:95–104. doi: 10.1080/10256010701362401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlman L, Persson J, Näsholm T, Palmquist K. Carbon and nitrogen distribution in the green algal lichens Hypogymnia physodes and Platismatia glauca in relation to nutrient supply. Planta. 2003;217:41–48. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-0977-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlman L, Persson J, Palmquist K, Näsholm T. Organic and inorganic nitrogen uptake in lichens. Planta. 2004;219:459–467. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson TE, Mambelli S, Plamboeck AH, Templer PH, Tu KP. Stable isotopes in plant ecology. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2002;33:507–559. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnik C, Beck A, Zarabska D. Distinction of Cladonia rei and Cladonia subulata based on molecular, chemical and morphological characters. Lichenologist. 2010;42:373–386. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenreich W, Knispel N, Beck A. Advanced methods for the study of the chemistry and the metabolism of lichens. Phytochem. Rev. 2011;10:445–456. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis CJ, Crittenden PD, Scrimgeour CM, Ashcroft C. The natural abundance of 15N in mat-forming lichens. Oecologia. 2003;136:115–123. doi: 10.1007/s00442-003-1201-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine PD, Bergstrom DM, Schmidt S, Stewart GR, Tweedie CE, Shaw JD. Subantarctic Macquarie Island – a model ecosystem for studying animal-derived nitrogen sources using 15N natural abundance. Oecologia. 1998;117:187–193. doi: 10.1007/s004420050647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RD. Physiological mechanisms influencing plant nitrogen isotope composition. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)01889-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Ehleringer JR, Hubick KT. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1989;40:503–537. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Confidence-limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel ML, Cifuentes LA. Isotopic fractionation during primary production. In: Engel M, Macko SA, editors. Organic geochemistry. New York: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel ML, Wooller MJ, Cheeseman J, Smallwood BJ, Roberts Q, Romero I, et al. Unusually negative nitrogen isotopic compositions (d15N) of mangroves and lichens in an oligotrophic, microbially-influenced ecosystem. Biogeosci. Discuss. 2008;5:937–969. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaniella B, Molina MC, Vicente C. An improved method for the separation of lichen symbionts. Phyton. 2000;40:323–328. [Google Scholar]

- Forman RTT. Canopy lichens with blue-green algae: a nitrogen source in a Colombian rain forest. Ecology. 1975;56:1176–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Freyer HD. Seasonal variation of 15N/14N ratios in atmospheric nitrate species. Tellus. 1991;43B:30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Galimov EM. Carbon isotope composition of Antarctic plants. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2000;64:1737–1739. [Google Scholar]

- Garvie LAJ, Knauth LP, Bungartz F, Klonowski S, Nash TH. Life in extreme environments: survival strategy of the endolithic desert lichen Verrucaria rubrocincta. Naturwissenschaften. 2008;95:705–712. doi: 10.1007/s00114-008-0373-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast and accurate method to estimate large phylogenies by maximum-likelihood. Syst. Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton THE. Isotopic studies of nitrogen pollution in the hydrosphere and atmosphere – a review. Chem. Geol. 1986;59:87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton THE, Spiro B, Madeline S, Robertson C. Potential canopy influences on the isotopic composition of nitrogen and sulphur in atmospheric deposition. Oecologia. 1997;109:600–607. doi: 10.1007/s004420050122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hietz P, Wanek W, Wania R, Nadkarni NM. Nitrogen-15 natural abundance in a montane cloud forest canopy as an indicator of nitrogen cycling and epiphyte nutrition. Oecologia. 2002;131:350–355. doi: 10.1007/s00442-002-0896-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie EA, Hobbie JE. Natural abundance of 15N in nitrogen-limited forests and tundra can estimate nitrogen cycling through mycorrhizal fungi: a review. Ecosystems. 2008;11:815–830. [Google Scholar]

- Hoering TC, Ford HT. The isotope effect in the fixation of nitrogen by Azotobacter. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960;82:376–378. [Google Scholar]

- Högberg H. Tansley Review No. 95 – N-15 natural abundance in soil–plant systems. New Phytol. 1997;137:179–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1997.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honegger R. Functional aspects of the lichen symbiosis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1991;42:553–578. [Google Scholar]

- Hübner H. Isotope effects of nitrogen in the soil and biosphere. In: Fritz P, Fontes JC, editors. Handbook of environmental isotope geochemistry. Vol. 2. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier; 1986. pp. 361–425. [Google Scholar]

- Krouse HR. Sulphur isotope abundances elucidate uptake of atmospheric sulphur emissions by vegetation. Nature. 1977;265:45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Krouse HR, Herbert HK. δ13C systematics of the lichens Ramalina celastri and Ramalina subfraxinea var. confirmata, coastal Eastern Australia and adjacent hinterland. In: van Aarsen BGK, editor. Australian organic geochemistry conference abstracts. Washington: Fremantle; 1996. pp. 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Krupa SV. Effects of atmospheric ammonia (NH3) on terrestrial vegetation: a review. Environ. Pollut. 2003;124:179–221. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(02)00434-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos M, Hartard B, Máguas C. The stable isotopes δ13C and δ18O of lichens can be used as tracers of micro-environmental carbon and water sources. In: Dawson T, Siegwolf R, editors. Isotopes as tracer of ecological change. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Academic Press; 2007. pp. 77–92. Chapter 6. [Google Scholar]

- Lange OL, Green TGA, Ziegler H. Water status related photosynthesis and carbon isotope discrimination in species of the lichen genus Pseudocyphellaria with green or blue-green photobionts and in photosymbiodemes. Oecologia. 1988;75:494–501. doi: 10.1007/BF00776410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange OL, Green TGA, Heber U. Hydration-dependent photosynthetic production of lichens: what do laboratory studies tell us about field performance? J. Exp. Bot. 2001;52:2033–2042. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.363.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom L, Ekman S. Molecular evidence supports the distinction between Xanthoria parietina and X. aureola (Teloschistaceae, lichenized Ascomycota) Mycol. Res. 2005;109:187–199. doi: 10.1017/s0953756204001790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom L, Ekman S. New evidence corroborates population differentiation in Xanthoria parietina. Lichenologist. 2007;39:259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Máguas C, Griffiths H, Ehleringer J, Serôdio J. Characterization of photobiont associations in lichens using carbon isotope discrimination techniques. In: Ehleringer J, Hall A, Farquhar J, editors. Stable isotopes and plant carbon–water relations. New York: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Máguas C, Griffiths H, Broadmeadow MSJ. Gas exchange and carbon isotope discrimination in lichens: evidence for interactions between CO2-concentrating mechanisms and diffusion limitation. Planta. 1995;196:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JD, Brooks JR, Lajtha K. Sources of variation in the stable isotopic composition of plants. In: Michener R, Lajtha K, editors. Stable isotopes in ecology and environmental science. 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2007. pp. 22–60. [Google Scholar]

- Matzek V, Vitousek P. Nitrogen fixation in bryophytes, lichens, and decaying wood along a soil-age gradient in Hawaiian Montane Rain Forest. Biotropica. 2003;35:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr C, Försterra G, Häussermann V, Wunderlich A, Grau J, Zieringer M, et al. Stable isotope variability in a Chilean food-web: implications for N- and C-cycles. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011;428:89–104. doi: 10.3354/meps09015. [Google Scholar]

- Moore H. The isotopic composition of ammonia, nitrogen dioxide and nitrate in the atmosphere. Atmos. Environ. 1977;11:1239–1243. [Google Scholar]

- Nadelhoffer K, Shaver G, Fry B, Giblin A, Johnson L, McKane R. 15N natural abundances and N use by tundra plants. Oecologia. 1996;107:386–394. doi: 10.1007/BF00328456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash TH. Nitrogen, its metabolism and potential contribution to ecosystems. In: Nash TH III, editor. Lichen biology. 2nd ed. Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge Univ. Press; 2008. pp. 216–233. [Google Scholar]

- Palmqvist K. Tansley Review No. 117 – carbon economy in lichens. New Phytol. 2000;148:11–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmqvist K, Campbell D, Ekblad A, Johansson H. Photosynthetic capacity in relation to nitrogen content and its partitioning in lichens with different photobionts. Plant Cell Environ. 1998;21:361–372. [Google Scholar]

- Palmqvist K, Dahlman L, Valladares F, Tehler A, Sancho LG, Mattsson J-E. CO2 exchange and thallus nitrogen across 75 contrasting lichen associations from different climate zones. Oecologia. 2002;133:295–306. doi: 10.1007/s00442-002-1019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pataki DE, Ehleringer JR, Flanagan LB, Yakir D, Bowling DR, Still CJ, et al. The application and interpretation of Keeling plots in terrestrial carbon cycle research. Global Biogeochem. Cycles. 2003;17:1022. doi: 10.1029/2001GB001850. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova EA, Maslov AI. Nitrate uptake by isolated bionts of the lichen Parmelia sulcata. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2008;55:475–479. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DL, Koch PL. Incorporating concentration dependence in stable isotope mixing models. Oecologia. 2002;130:114–125. doi: 10.1007/s004420100786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D. ModelTest Server: a web-based tool for the statistical selection of models of nucleotide substitution online. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W700–W703. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl042. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D. jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008;25:1253–1256. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post DM. Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology. 2002;83:703–718. [Google Scholar]

- Rai AN. Nitrogen metabolism. In: Galun M, editor. CRC handbook of lichenology. I. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Inc; 1988. pp. 201–237. [Google Scholar]

- Rai AN, Rowell P, Stewart WDP. 15N2 incorporation and metabolism in the lichen Peltigera aphthosa Willd. Planta. 1981;152:544–552. doi: 10.1007/BF00380825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai AN, Rowell P, Stewart WDP. Mycobiont–cyanobiont interactions during dark nitrogen fixation by the lichen Peltigera aphtosa. Physiol. Plant. 1983;57:285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson DHS. War in the world of lichens: parasitism and symbiosis as exemplified by lichens and lichenicolous fungi. Mycol. Res. 1999;103:641–650. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson DHS, Smith DC. Lichen physiology. IX. Carbohydrate movement from the Trebouxia symbiont of Xanthoria aureola to the fungus. New Phytol. 1968;67:61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Riera P. δ13C and δ15N comparisons among different co-occurring lichen species from littoral rocky substrata. Lichenologist. 2005;37:93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D. δ15N as an integrator of the nitrogen cycle. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001;16:153–162. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(00)02098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. PAUP: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (and other methods), Version 4. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tozer WC, Hackell D, Miers DB, Silvester WB. Extreme isotopic depletion of nitrogen in New Zealand lithophytes and epiphytes: the result of diffuse uptake of atmospheric ammonia? Oecologia. 2005;144:628–635. doi: 10.1007/s00442-005-0098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virginia RA, Delwiche CC. Natural 15N abundance of presumed N2-fixing and non-N2-fixing plants from selected ecosystems. Oecologia. 1982;54:317–325. doi: 10.1007/BF00380000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YM, Wooller MJ. The stable isotopic (C and N) composition of modern plants and lichens from northern Iceland: with ecological and paleoenvironmental implications. Jökull. 2006;56:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman RD, Wadleigh MA. Lichen response to changes in atmospheric sulphur: isotopic evidence. Environ. Pollut. 2002;116:235–241. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(01)00133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]