ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Handoffs are communication processes that enact the transfer of responsibility between providers across clinical settings. Prior research on handoff communication has focused on inpatient settings between provider teams and has emphasized patient safety. This study examines handoff communication within multidisciplinary provider teams in two outpatient settings.

OBJECTIVE

To conduct an exploratory study that describes handoff communication among multidisciplinary providers, to develop a theory-driven descriptive framework for outpatient handoffs, and to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of different handoff types.

DESIGN & SETTING

Qualitative, in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 31 primary care, mental health, and social work providers in two Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center outpatient clinics.

APPROACH

Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed and analyzed using Grounded Practical Theory to develop a theoretical model of and a descriptive framework for handoff communication among multidisciplinary providers.

RESULTS

Multidisciplinary providers reported that handoff decisions across settings were made spontaneously and without clear guidelines. Two situated values, clinic efficiency and patient-centeredness, shaped multidisciplinary providers’ handoff decisions. Providers reported three handoff techniques along a continuum: the electronic handoff, which was the most clinically efficient; the provider-to-provider handoff, which balanced clinic efficiency and patient-centeredness; and the collaborative handoff, which was the most patient-centered. Providers described handoff choice as a practical response to manage constituent features of clinic efficiency (time, space, medium of communication) and patient-centeredness (information continuity, management continuity, relational continuity, and social interaction). We present a theoretical and descriptive framework to help providers evaluate differential handoff use, reflect on situated values guiding clinic communication, and guide future research.

CONCLUSIONS

Handoff communication reflected multidisciplinary providers’ efforts to balance clinic efficiency with patient-centeredness within the constraints of day-to-day clinical practice. Evaluating the strengths and weaknesses among alternative handoff options may enhance multidisciplinary provider handoff decision-making and may contribute to increased coordination and continuity of care across outpatient settings.

KEY WORDS: handoff, communication, outpatient care, decision making, coordination of care, continuity of care, patient-centeredness, clinic efficiency

INTRODUCTION

A handoff has been defined as the process of transferring clinical roles and responsibilities between providers across health care settings.1,2 Previous literature has suggested that handoff effectiveness includes efficient communication between providers during care transitions1,3,4 and the ability of providers to coordinate roles and responsibilities,5–7 which may contribute to overall continuity8 and coordination of care.9–11 Handoffs that occur laterally between providers from different specialties may be a key ingredient contributing to coordinated care,12 but they can be performed suboptimally or may not occur at all, which may result in communication lapses and discontinuity.13

Most handoff communication occurs in the inpatient setting where physicians, trainees, and nurses coordinate responsibility for the patient’s overall care.14–19 Communication error has been shown to negatively impact patient safety within the inpatient setting.16,19,20 While research on handoffs in the inpatient setting has proliferated, research on outpatient handoffs is limited.

In outpatient settings, multidisciplinary providers are simultaneously responsible for distinct facets of patient care. For example, while primary care providers deal with medical problems,21 specialty mental health providers address psychological problems.22–24 Some collaborative care models have emphasized care coordination between specialties for complex medical conditions,25–28 and have characterized handoffs as “cold,”26 “lukewarm,”26 or “warm;”21–25,27,28 however, these terms have neither been well-defined nor have they been investigated empirically to determine their interactional components.

We conducted a qualitative study to explore the techniques multidisciplinary providers reported when transferring patients between outpatient specialties. The three primary objectives of this study were: first, to conduct an exploratory study that describes routine handoff communication among multidisciplinary providers in two outpatient settings and, second, to develop a theory-driven descriptive framework that identifies constituent features of outpatient handoffs, and third, to characterize the strengths and weaknesses of different handoff types.

STUDY DESIGN & METHODS

Theoretical Orientation

Grounded Practical Theory (GPT)29 is a metatheoritical framework and a variation of the Grounded Theory Method.30 Using discourse analytic techniques,31–33 GPT describes observed or reported behavior in general terms, a process known as theoretical reconstruction, to make habitual communication techniques and values explicit. As a theoretical framework, GPT seeks to empirically inform good practice by developing theories whose ultimate test are their practical usefulness and for reflective practice.34–37

Setting and Participants

The San Francisco VA Medical Center (SFVAMC) has a large, urban primary care clinic, in which approximately 30 primary care providers are available on any given day and serve several hundred patients per week. Because the SFVAMC primary care clinic has adopted the VA Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) Model, it also includes two full-time, co-located mental health providers and several social workers.38–41 Embedded within this usual care PACT clinic, a separate primary care-mental health-social services integrated clinic serves returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans.42,43 Iraq and Afghanistan veteran patients who initiate primary care upon returning from deployment may be scheduled for a “one-stop” integrated visit for their initial appointment. Integrated visits consist of three 50-min sessions with primary care, mental health, and social service providers.44,45 Eight total integrated care appointments are available each week, seven for male and one for female returning veterans. Due to the limited availability of integrated care appointments, some new patients are seen in the usual care clinic where they are scheduled for a primary care visit, but also have the option of also seeing co-located social work or mental health providers. Both usual and integrated care providers have the option of conducting handoffs to co-located mental health and social service providers.

We purposively sampled primary care, mental health and social work providers among provider teams who routinely transfer care of veteran patients between specialties in both clinics. We focused on the Iraq and Afghanistan veteran population because SFVAMC multidisciplinary provider teams routinely coordinate these patients’ initial visits. This study examines communication among multidisciplinary providers only during these initial visits. We contacted division heads for the names of providers who worked with Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Providers were eligible if they held licenses or were trainees in primary care, mental health, or social work, and had cared for two or more Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in the past 6 months. We sent eligible providers an introduction letter, an information sheet, and an opt-out postcard. If the postcard was not returned within 14 days, we contacted them by phone to explain the study and to invite their participation. The Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco, the Research Protection Program at the SFVAMC, and the United States Department of Defense approved this research.

Data Collection

The first author (CJK), a medical linguist with expertise in qualitative methodology, conducted individual semi-structured interviews between June and December 2010 in usual and integrated care clinics. Interviews began with an explanation of the study goals to investigate providers’ experiences caring for newly returned veterans as part of a multidisciplinary team. Participants received no payment for participation.

The study team developed a semi-structured interview guide46 drawing on the senior author’s (KHS) experience as a primary care clinician in treating Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, and as an active member of a multidisciplinary team in both clinics. The full interview guide included general questions about multidisciplinary collaboration, provider-to-provider communication, and handoff communication included in Table 1, as well as specific questions about perceptions of clinic organization, staffing, and provider self-care behavior, which we will address in future publications. Five national experts in VA post-deployment primary care-mental health integration reviewed the interview guide, and we incorporated their suggestions. We piloted the instrument in our first five interviews and removed follow-up probes to reduce overall interview length. Interviews lasted approximately 30 min (mean duration = 34 min; SD ±9:44 min). All interviews were audio-recorded with participants’ permission. A professional transcribed the recorded audio files verbatim. Transcribed interviews resulted in 670 total pages of transcripts (mean length = 32.3 pages; SD ±12.8 pages).

Table 1.

Example Interview Areas and Illustrative Questions from the Semi-Structured Interview Guide

| Interview area | Illustrative Questions |

|---|---|

| Multidisciplinary collaboration | Do primary care, mental health, and social work providers have areas of overlap within this clinic? If so, what are they? What are some positive aspects of this overlap? What are some negative aspects of this overlap? Does the overlap of responsibilities help you feel more supported in your role? Or does it simply add redundancy? |

| Provider-to-provider communication | In an ordinary visit, how much communication would you have with another provider type? Can you give me a typical example? |

| Can you identify some of the methods you regularly use to communicate with providers inside your clinical unit? What methods do you regularly use to communicate with providers outside your clinical unit? | |

| Handoff communication | Can you explain what happens after you end your visit with a patient? Is there something special you do? |

| Can you describe how you transition patients between visits? What are some benefits/drawbacks of transferring a patient in this way? How else do you transfer patients between visits? | |

Data Analysis

To generate our analysis, we first segmented transcripts into question-answer sequences47 as the basic analytic unit. Next, we condensed the semi-structured interview guide into a provisional coding scheme,48 which provided sensitizing concepts49 for interpreting participants’ meanings.50 Two experienced coders (CJK, AD) simultaneously listened to the audio recordings while manually coding the corresponding transcripts. Listening to interviews while coding enabled the team to be immersed in the interview situation, and to discern interactional features that contributed to participants’ meanings, such as emphatic intonation or speaking pauses. Coders applied all provisional codes separately to the first ten interviews chronologically in the order they were collected. Coders met weekly to discuss similarities and differences, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion until reaching consensus. All identified units were coded, and particularly rich segments were annotated.

After completing ten interviews, we noticed that integrated care providers had particularly rich descriptions of communication with one another before and after visits with Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. The senior author’s experience as a primary care provider confirmed the importance of care transfer between multidisciplinary providers for these veterans,31 and suggested conducting a literature review for handoffs in outpatient settings. Finding relatively little previous research, we decided to focus our analysis on handoff communication patterns between multidisciplinary outpatient care providers.

Returning to the data, the first author entered all segmentation decisions, provisional codes, and annotations into Atlas.ti software51 to facilitate qualitative data management.52 We reviewed and grouped each of the 51 units so-far identified into collections for systematic comparison.53 We used these units to construct the initial theoretical model illustrated in Figure 1. To corroborate preliminary findings, we used focused coding techniques48,54 to identify units uniquely describing handoff communication in the remaining 21 interviews. We reached saturation after identifying 482 units, 99 of which described handoff communication. Constant comparison techniques of the full collection confirmed and refined the model by iteratively comparing all instances against one another. We validated the model by periodically presenting findings to participants during informal feedback sessions in a collective forum held three times throughout the analytic process. Quotations are anonymized and have been edited for clarity.

Figure 1.

Grounded Practical Theory (GPT) of outpatient handoff communication.

RESULTS & ANALYSIS

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

Out of 75 eligible providers, 31 were interviewed, including four trainees. There was no discernable difference between providers who did and did not participate. The most common reasons provided for non-participation were: did not routinely see Iraq and Afghanistan veterans (n = 5), lacked time to participate in the study (n = 8), or did not respond to solicitations (n = 31). Social workers accounted for 9.7 % (n = 3) of the sample, whereas mental health and primary care providers accounted for 38.7 % (n = 12) and 51.6 % (n = 16), respectively, which matched the overall distribution of all eligible providers. More than half of the participants were female (67 %, n = 21). Providers had a mean of 11.5 years working in their area of specialization and an average of 9.9 years working at the VA.

Methods of Communication Across Settings

Multidisciplinary providers in usual and integrated care clinics described various communication methods to coordinate patient care. One common method used the VA electronic medical record (EMR) to communicate specific information. For example, after a mental health appointment, psychologists reported using an electronic signature, a procedure that requires the targeted provider to acknowledge receipt of a progress note, an addendum, or other clinical notification. Another common method was the “curbside consultation,” a brief, face-to-face conversation between providers about professional matters when they opportunistically encountered one another in a private hallway or other area. Finally, providers described various handoff techniques in which transfers of patient care were precisely coordinated between provider types described in the next section.

Outpatient Handoff Communication Techniques

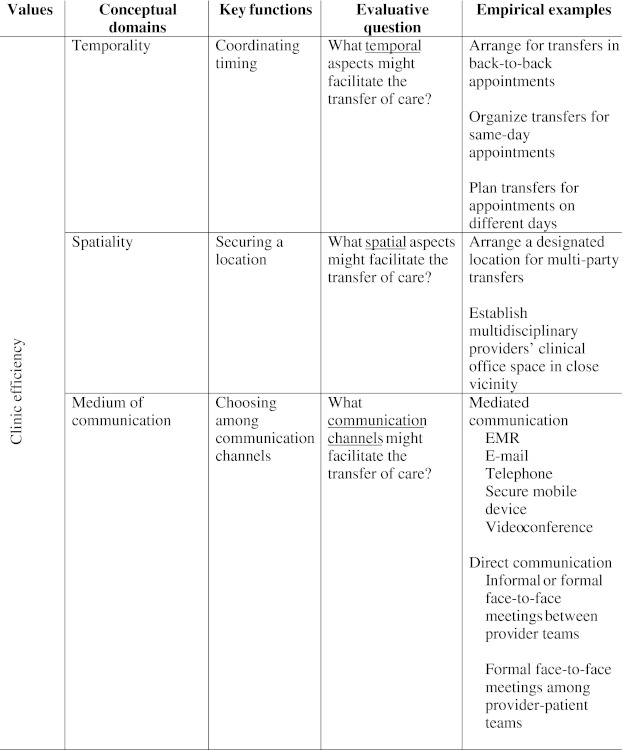

Overwhelmingly, multidisciplinary providers reported that handoff decisions were made spontaneously and without clear guidelines. Two situated values, clinic efficiency and patient-centeredness, guided multidisciplinary providers’ handoff decisions in transferring patients. Although providers in both clinics described similar handoff techniques, integrated care providers had particularly rich descriptions, due to the repeated and routine nature of cross-disciplinary communication. We assembled providers’ descriptions into three distinct handoff techniques illustrated in Figure 1: the electronic handoff, the provider-to-provider handoff, and the collaborative handoff. Table 2 presents a descriptive framework that identifies major constituent features of outpatient handoffs across settings. In the next section, we present each handoff technique in detail.

Table 2.

Descriptive Framework of Outpatient Handoff Communication Across Settings

The Electronic Handoff

The first handoff technique involved a first provider transferring patient care through an electronic referral for consultation, which we call “electronic handoff”. Once initiated, the EMR facilitates contact among and between providers to transfer patients with routine, non-urgent problems. The following quotations describe the electronic handoff process:

Extract 1. 5023, 8:29 Mental health provider

If I’m not physically at the VA during my half-day a week, I get electronic consults through CPRS [Computerized Patient Record System]. Primary care can put in that request electronically, and then I can call the patient and schedule them for a time to come in to meet with mental health.

Extract 2. 4067, 29:1 Primary care provider

[When] I would write a mental health consult, I would submit it electronically. Then they [the mental health clinic] would set up an appointment weeks down the way. At that time, either the patient would have forgotten about the visit or it would never happen for some reason.

In Extract 1, the mental health provider describes using the EMR, an indirect or mediated medium of communication, to transfer clinical information asynchronously and remotely from the previous provider, a primary care provider. The electronic handoff uses the EMR to exchange clinical information and to coordinate patient care after a specific visit. Similarly, in Extract 2 a primary care provider describes using the EMR to make a referral to specialty mental health. The mental health clinical team subsequently takes responsibility for following up with the patient. This provider speculates that electronic handoffs may negatively influence patient engagement because the process may take place over a period of weeks or even months.

The Provider-to-Provider Handoff

In the second handoff technique, providers in both usual and integrated care clinics transferred patient care through either telephone (Extract 3) or curbside communication. Additionally, integrated care providers held informal or formal face-to-face meetings (Extract 4) between appointments:

Extract 3. 5023, 8:23 Mental health provider

Typically, primary care sees the patient first, then I will get a [telephone] call like, “I just met with someone, and nothing much is going on.” Or they will say, “Yeah, this patient has PTSD [posttraumatic stress disorder] and SUD [substance use disorder], so I’m making a referral to PCT [PTSD Clinical Team].” Within 5 to 10 min after the call, I can meet with the patient.

Extract 4. 4032, 13:9 Primary care provider

I usually walk the patient to the waiting room [after the visit], and I say, “You are going to see the deployment stress specialist next (mental health provider). Wait here, and she (the mental health provider) will come pick you up.” Then, (the) mental health (provider) will instead come directly to me so we can talk one-on-one. I do a 5-min chat with the mental health provider alone in my office before she sees the patient so she knows what I have covered [and] what my concerns are. Then, she will go get the patient in the waiting room.

After the end of the visit, the first provider takes leave of the patient to communicate privately with the next provider. Because the patient is not present, providers are free to use technical terminology (e.g., PTSD, SUD) or refer to familiar organizational processes or clinical teams (e.g., PCT), which may contribute to clinic efficiency. This technique may also facilitate patient-centeredness because providers exchange information between visits, which enables next providers to “jump start” subsequent visits by demonstrating specific knowledge of a patient’s experiences, medical history, and symptoms, illustrated in the following extract:

Extract 5. 4026, 10:9, Primary care provider

I think it’s frustrating for the patient to start from scratch in every visit…it’s nicer for them when they meet that second person to say, “Dr. (primary care provider) mentioned that you experienced something in Iraq, and it’s been tough for you having nightmares.” Rather than starting from a blank slate, we have some continuity between visits. But it is challenging to do if my next patient is waiting right there at my door.

The temporal immediacy of the provider-to-provider exchange facilitates patient-centeredness in two ways. First, patients benefit when a second provider demonstrates specific knowledge of a patient’s experiences, history, and associated symptoms rather than “starting from a blank slate.” Second, patients may infer a good working relationship between providers who demonstrate coordination of care across visits. The main drawback of this technique is that time constraints make it challenging to exchange information during high workflow.

The Collaborative Handoff

In the final handoff technique, providers transferred patient care through a face-to-face meeting with the patient present. While usual care providers reported using this technique primarily with patients who had emergency psychiatric or social service problems, integrated care providers routinely used this technique for Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, regardless of screening results or perceived biopsychosocial risk. Providers described collaborative handoffs as a multi-step process:

Extract 6. 7016, 18:9–10 Mental health provider

When a veteran screens positive [for a mental health problem], ideally, the primary care provider addresses whether the individual is interested in talking to someone about what [treatment] options are available. Then, they walk him on over. Because the [primary care] provider already has a relationship—even if it’s just newly established—there is an introduction, like, “I want you to meet Dr. [mental health provider], we’re going to be seeing him and talk to him a little bit about what we discussed in our visit together.” We then have a short conversation with the patient to discuss it all together.

In Extract 6, the collaborative handoff begins when the primary care provider explains the meaning of a positive mental health screen or other mental health problem during the first visit and suggests further assessment or treatment. If the patient agrees, the first provider accompanies the patient to the next visit where she introduces the patient to the second provider. Finally, the three participants discuss the patient’s clinical and social situation together.

Providers felt the main benefit of this technique was enhanced rapport-building across and between the provider–patient teams:

Extract 7. 4067, 29:1 Primary care provider

In medical practice, if I take a patient by the hand and walk over to introduce him [to the mental health provider], he can see that they are a nice person who wants to help, and that it’s not as scary as they imagined. If we can make the initial handoff directly, chances are they will come back again.

The personalized introduction described in Extract 7 helps establish an ongoing relationship among provider and patient participants. Because the patient is present, she or he has the opportunity to participate in and to monitor communication between providers firsthand, which contributes to transparency of the care transfer. Additionally, this provider implies that collaborative transfers may mitigate stigma associated with specialty mental health care. Finally, this provider speculates that this technique may promote continued treatment engagement beyond the first visit. Despite these benefits, the collaborative handoff presents logistical challenges:

Extract 8. 1033, 14:7 Primary care provider

We have a little problem with timing. Sometimes veterans come in late or the providers are backed up. So when the medical visit starts late, we try to play catch up and keep others attuned [about] how we’re doing with our visit time. But then it is hard to coordinate [a handoff with the next provider] because we are trying to get the veteran through the clinic as fast as possible.

A successful collaborative handoff requires both additional time and space, which are scarce resources. The provider in Extract 8 articulates a tension between enacting a collaborative handoff and maintaining efficient clinic workflow.

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study describes three handoff techniques that multidisciplinary providers used when transferring patients between visits in usual and integrated VA outpatient clinics. Our empirical analysis suggests that handoff “warmth” may not be related to handoff type, but rather to how providers manage the dual values of clinic efficiency and patient-centeredness in their routine communication choices. Across settings, providers demonstrated an implicit understanding of the relative advantages and disadvantages of each technique, although few could articulate explicit criteria for why one technique might be used over another. In the following section, we use our descriptive framework to evaluate the advantages, disadvantages, and usage suggestions for each handoff type to foster critical reflection29,34–37 about handoff decision-making.

Evaluating Outpatient Handoff Communication

The Electronic Handoff

The electronic handoff prioritizes clinic efficiency through the use of the EMR as the primary medium of communication when providers are separated in time and/or space.3,11 The electronic handoff is a type of electronic referral in which the EMR is used to exchange clinical information after a visit with one provider and before a visit with the next provider. The electronic handoff can be differentiated from other EMR uses, such as the electronic signature, because whereas the latter requires a targeted provider to acknowledge receipt of a clinical notification, the former uses the EMR specifically to coordinate patient care between visits. Research on electronic referrals has shown that communication mediated through the EMR can accurately transfer clinical and demographic information,55 which may facilitate informational continuity between providers.8

Various risks have been associated with EMR communication, including inaccurate assumptions about the intent and motivation of transfer,1 communication breakdowns,56 insufficient information,6,7 and inappropriate referrals,57 which can result in patients lost to follow-up.

The electronic handoff may be effectively used with patients who have routine clinical and social problems that do not require immediate provider contact or consultation. This handoff type may be inappropriate for higher-risk patients requiring significant management and relational continuity among multidisciplinary teams, and social interaction between provider–patient teams.

The Provider-to-Provider Handoff

The provider-to-provider handoff balances clinic efficiency and patient-centeredness. Providers coordinate care transfer by employing multiple mediums of communication, such as the telephone or face-to-face communication, to discuss patient care in professional and technical terms. This coordination may minimize communication lapses4 while maximizing management continuity8,58–60 that may prevent lost follow-up, creation of cross-disciplinary treatment plans, and negotiation of roles and responsibilities across specialties. Providers using this technique may also contribute to relational continuity,5,8 through relaying patient narratives and treatment preferences, an important facet of patient-centered care.

Lack of designated time and space can hinder communication if either provider is late or backlogged with patients,6,7 potentially compromising the quality of provider exchange.3,4 Finally, this technique prioritizes inter-provider communication, but excludes social interaction between provider–patient teams, which may compromise overall continuity of care.10

The provider-to-provider handoff may be effectively used when providers must openly discuss patients with complex or urgent problems. Patients may feel part of the health care team because multiple providers demonstrate specific knowledge of a patient’s experiences and biopsychosocial history.

The Collaborative Handoff

The collaborative handoff prioritizes patient-centeredness through formal face-to-face meetings among provider–patient teams during care transitions.1,8 Provider–patient teams meet together at a designated time and place, which facilitates social interaction and may reduce stigma associated with mental health care. Because the patient is an active participant in the care transfer, she or he has the opportunity to help shape what clinical and social information is discussed, which may contribute to relational continuity through a multidisciplinary therapeutic alliance.5,8

The most obvious disadvantage of the collaborative handoff is the challenge of coordinating multiple participants to be present at the same place and time. Less obviously, while the presence of the patient facilitates active participation, it also changes the social dynamics of the exchange.61 For example, providers may not mention sensitive, potentially embarrassing, or technical clinical information while a patient is present, which may result in a failure to transfer some clinically important information.

The collaborative handoff may be effectively used in clinical settings in which multidisciplinary providers are co-located; and for patients who have complex, comorbid conditions, who have the potential for poor engagement in care, or whose care may benefit from developing a robust therapeutic alliance with their provider team up-front. For instance, previous literature suggests this technique may be particularly valuable with patients who have been exposed to trauma, such as returning combat veterans.23 Some providers suggested that the collaborative handoff was effective for promoting follow-up for patients who were in need of help, but resistant to referrals to specialty care, such as mental health or social work.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, data are limited to 31 multidisciplinary providers from two outpatient clinics at a single VA facility. Expanding the data collection to additional sites may enrich current findings and increase generalizability. Second, the primary data for this study were qualitative, semi-structured interviews. While interviews can provide detailed descriptions, they lack the empirical detail that participant observation or audio-video recordings might provide. Third, questions about inter-provider communication and handoffs were one part of a larger semi-structured interview. Focused interviews, participant observation, and audiovisual recording concentrated specifically on these topics may reveal more robust detail within and between handoff techniques. Finally, because Grounded Practical Theory is an interpretive theoretical framework, other interpretations may be possible.

CONCLUSION

This qualitative study describes how multidisciplinary providers coordinate the transfer of patient care through handoff communication in two outpatient settings. Our analysis suggests that while providers are experts at navigating the practical contingencies of day-to-day clinical work, they may not have an explicit understanding of their situated communication strategies. Our outpatient handoff communication model aims to develop a practical theory to help multidisciplinary providers articulate how, why, and when they use handoffs in day-to-day clinical practice, while simultaneously balancing multiple clinic values in light of system ideals. Each handoff is an opportunity for reflection as well as action. We advocate a pragmatic orientation towards handoff decision-making where the right tool is used for the right job with the goal of enhancing patient care across different outpatient settings.

Acknowledgements

Contributors

We would like to thank the SFVAMC primary care providers, mental health providers, and social workers that took time to participate in this study. We also thank Dr. Lucile Burgo, Dr. John Chardos, Dr. Brad Felker, Dr. Drew Helmer, and Dr. Steve Hunt for their feedback on the interview guide. We extend a special thanks to Drs. Robert Craig, Karen Tracy, and Daniel Dohan for their theoretical counsel. Finally, we acknowledge and thank all Iraq and Afghanistan veterans for their service to our country.

Funders

Department of Defense awards W81XWH-08-2-0072 and W81XWH-08-2-0106 funded this study. The funders had no role in the design, data analysis, writing or approval of the manuscript.

Prior Presentations

A version of this article was presented orally at the annual meeting of the International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies in November, 2011.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Solet DJ, Norvell JM, Rutan GH, Frankel RM. Lost in translation: Challenges and opportunities in physician-to-physician communication during patient handoffs. Acad. Med. 2005;80(12):1094–1099. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200512000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patterson ES, Wears RL. Patient handoffs: Standardized and reliable measurement tools remain elusive. Joint Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36(2):52–61. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forrest CB. A typology of specialists’ clinical roles. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(11):1062–1068. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen AH, Yee HF. Improving the primary care-specialty care interface. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(11):1024–1026. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehrota A, Forrest CB, Lin CY. Dropping the Baton: Specialty referrals in the United States. Millbank Q. 2011;89(1):39–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein RM. Communication between primary care physicians and consultants. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4:403–409. doi: 10.1001/archfami.4.5.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gandhi TK, Sittig DF, Franklin M, Sussman AJ, Fairchild DG, Bates DW. Communication breakdown in the outpatient referral process. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:626–631. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.91119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: A multi-disciplinary review. Br Med J. 2003;327:1219–1221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM. Care coordination. In: Shojania KG, McDonald KM, Watcher RM, Owens DK, editors. Closing the quality gap: A critical analysis of quality improvement strategies. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Stanford Univesity-UCSF Evidence-based Practice Center; 2007 [PubMed]

- 10.Kimerling R, Pavao J, Valdez C, Mark H, Hyun JK, Saweikis M. Military sexual trauma and patient perceptions of Veteran Health Administration health care quality. Wom Health Issues. 2011;21(4S):S145–S151. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care–A perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1064–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0706165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanton M, Dunkin JA. A review of case management functions relation to transitions of care at a rural nurse managed clinic. Prof Case Manag. 2009;14(6):321–327. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0b013e3181c3d405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coleman EA, Berenson RA. Lost in transition: Challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(7):533–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-7-200410050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arora VM, Manjarrez E, Dressler DD, Basaviah P, Halasyamani L, Kripalani S. Hospitalist handoffs: A systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):433–440. doi: 10.1002/jhm.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. What are covering doctors told about their patients? Analysis of sign-out among internal medicine house staff. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(4):248–255. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.028654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang LL, Bradley EH. Consequences of inadequate sign-out for patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1755–1760. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeffcott SA, Evans SM, Cameron PA, Chin GSM, Ibrahim JE. Improving measurement in clinical handover. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(4):272–277. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.024570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manser T, Foster S, Gisin S, Jaeckel D, Ummenhofer W. Assessing the quality of patient handoffs at care transitions. Quality & Safety in Health Care. 2010;19(6). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Raduma-Tomas MA, Flin R, Yule S, Williams D. Doctors’ handovers in hospitals: a literature review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2011;20(2):128–133. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.034389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen MD, Hilligoss PB. The published literature on handoffs in hospitals: deficiencies identified in an extensive review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(6):493–497. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.033480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolber T, Ward D. Implementation of a diabetes nurse case management program in a primary care clinic: a process evaluation. J Nurs Healthc Chronic Illn. 2010;2(2):122–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-9824.2010.01051.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacGregor C, Hamilton AB, Oishi SM, Yano EM. Description, development, and philosophies of mental health service delivery for female veterans in the VA: A qualitative study. Wom Health Issues. 2011;21(4):S138–S144. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elder M, Silvers S. The integration of psychology into primary care: Personal perspectives and lessons learned. Psychol Serv. 2009;6(1):68–73. doi: 10.1037/a0014006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Funderburk J, Maisto S, Sugarman D, Smucny J, Epling J. How do alcohol brief interventions fit with models of integrated primary care? Fam Syst Health . 2008;26(1):1–15. doi: 10.1037/1091-7527.26.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigford BJ. “To Care for Him Who Shall Have Borne the Battle and for His Widow and His Orphan” (Abraham Lincoln): The Department of Veterans Affairs Polytrauma System of Care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(1):160–162. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tai-Seale M, Kunik ME, Shepherd A, Kirchner J, Gottumukkala A. A case study of early experience with implementation of collaborative care in the Veterans Health Administration. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13(6):331–337. doi: 10.1089/pop.2009.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belanger HG, Uomoto JM, Vanderploeg RD. The Veterans Health Administration system of care for mild traumatic brain injury: Costs, benefits, and controversies. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2009;24(1):4–13. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181957032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunter C, Goodie J. Operational and clinical components for integrated-collaborative behavioral healthcare in the patient-centered medical home. Fam Syst Health . 2010;28(4):308–321. doi: 10.1037/a0021761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craig R, Tracy K. Grounded practical theory: The case of intellectual discussion. Commun Theory. 1995;5(3):248–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.1995.tb00108.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bryant A, Charmaz K, editors. The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts C, Sarangi S. Theme-oriented discourse analysis of medical encounters. Med Educ. 2005;39(6):632–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koenig CJ. Patient resistance as agency in treatment decisions. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(7):1105–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mirivel JC. Communicative Conduct in commercial medicine: Initial consultations between plastic surgeons and prospective clients. Qual Heal Res. 2010;20(6):788–804. doi: 10.1177/1049732310362986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brady DW, Corbie-Smith G, Branch WT. “What’s important to you?”: The use of narratives to promote self-reflection and to understand the experiences of medical residents. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(3):220–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-3-200208060-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bolton G. Reflective Practice: Writing and Professional Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenhalgh J, Flynn R, Long AF, Tyson S. Tacit and encoded knowledge in the use of standardised outcome measures in multidisciplinary team decision making: A case study of in-patient neurorehabilitation. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(1):183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charon R. Narrative medicine - A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897–1902. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen BE, Gima K, Bertenthal D, Kim S, Marmar CR, Seal KH. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA non-mental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2009. Epub 2009/09/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Hoge CW. Interventions for war-related posttraumatic stress disorder meeting veterans where they are. JAMA. 2011;306(5):549–551. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vogt D. Mental health-related beliefs as a barrier to service use for military personnel and veterans: A review. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(2):135–142. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seal KH, Cohen BE, Metzler TJ, Gima K, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, et al. Mental health services utilization at VA facilities among Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans in the first year of receiving mental health diagnoses. J Trauma Stress. in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Lu MW, Duckart JP, O’Malley JP, Dobscha SK. Correlates of utilization of PTSD specialty treatment among recently diagnosed veterans at the VA. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(8):943–949. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.8.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeiss AMKB. Integration of Mental health and primary care services in the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2008;15:73–78. doi: 10.1007/s10880-008-9100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maguen S, Cohen G, Cohen BE, Lawhon D, Marmar CR, Seal KH. The role of psychologists in the care of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in primary care settings. Prof Psychol: Res Pract. 2010;41(2):135–142. doi: 10.1037/a0018835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kvale S, Brinkmann S. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sacks H, Schegloff E, Jefferson G. A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language. 1974;50(1):696–735. doi: 10.2307/412243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miles M, Huberman M. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blumer H. What is wrong with social theory? Am Sociol Rev. 1954;18:3–10. doi: 10.2307/2088165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hruschka DJ, Schwartz D, St. John DC, Picone-Decaro E, Jenkins RA, Carey JW. Reliability in coding open-ended data: Lessons learned from HIV behavorial research. Field Methods. 2004;16(3):307–331. doi: 10.1177/1525822X04266540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muhr T. Atlas.ti. 61. Berlin: Scientific Software Development GmbH; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crabtree B, Miller M, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Have P. Doing Conversation Analysis: A practical guide. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shaw LJ, de Berker DAR. Strengths and weaknesses of electronic referral: comparison of data content and clinical value of electronic and paper referrals in dermatology. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(536):223–224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh H, Esquivel A, Sittig D, Murphy D, Kadiyala H, Schiesser R, et al. Follow-up actions on electronic referral communication in a multispecialty outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(1):64–69. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1501-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim-Hwang JE, Chen AH, Bell DS, Guzman D, Yee HF, Kushel MB. Evaluating electronic referrals for specialty care at a public hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(10):1123–1128. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1402-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Keating NL, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Physicians’ experiences and beliefs regarding informal consultation. JAMA. 1998;280(10):900–904. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.10.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuo D, Gifford DR, Stein MD. Curbside consultation practices and attitudes among primary care physicians and medical subspecialists. JAMA. 1998;280(10):905–909. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.10.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Myers JP. Curbside consultation in infectious diseases: A prospective study. J Infect Dis. 1984;150(6):797–82. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.6.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goffman E. Interaction Ritual: Essays on Face-to-Face Behavior. New York: Pantheon Books; 1967. [Google Scholar]