ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To assess the impact of four patient information leaflets on patients’ behavior in primary care.

DESIGN

Cluster randomized multicenter controlled trial between November 2009 and January 2011.

PARTICIPANTS

French adults and children consulting a participating primary care physician and diagnosed with gastroenteritis or tonsillitis. Patients were randomized to receive patient information leaflets or not, according to the cluster randomization of their primary care physician.

INTERVENTION

Adult patients or adults accompanying a child diagnosed with gastroenteritis or tonsillitis were informed of the study. Physicians in the intervention group gave patients an information leaflet about their condition. Two weeks after the consultation patients (or their accompanying adult) answered a telephone questionnaire on their behavior and knowledge about the condition.

MAIN MEASURES

The main and secondary outcomes, mean behavior and knowledge scores respectively, were calculated from the replies to this questionnaire.

RESULTS

Twenty-four physicians included 400 patients. Twelve patients were lost to follow-up (3 %). In the group that received the patient information leaflet, patient behavior was closer to that recommended by the guidelines than in the control group (mean behavior score 4.9 versus 4.2, p < 0.01). Knowledge was better for adults receiving the leaflet than in the control group (mean knowledge score 4.2 versus 3.6, p < 0.01). There were fewer visits for the same symptoms by household members of patients given leaflets (23.4 % vs. 56.2 %, p < 0.01).

CONCLUSION

Patient information leaflets given by the physician during the consultation significantly modify the patient’s behavior and knowledge of the disease, compared with patients not receiving the leaflets, for the conditions studied.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2164-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: patient information leaflet, primary care, general practice, patient behavior, knowledge about disease

INTRODUCTION

The exchange of information is one of the duties of the physician and is at the heart of the doctor–patient relationship. Patients are keen to receive patient information leaflets (PIL)1–4 and use them.5,6 Many doctors believe that, in addition to oral information, written information is essential. Written information has several advantages: it improves patients' satisfaction,7,8 it increases their knowledge of the condition,8–10 it helps patients remember what was said during the consultation,1,10 and it also limits the number of unnecessary medications requested by patients.11 However, despite a wealth of patient information material, very little meets all the quality criteria defined by the UK Department of Health12 or the French National Authority for Health (Haute Autorité de Santé, HAS),13 such as the names of the authors, the date of writing and/or the sources used, even though all these items are expected by patients. Written information is an area that should be more fully researched for ethical, quality and economic reasons.14

Information leaflets targeting high blood pressure and oral contraception have resulted in an improvement in patient knowledge9,15,16 and satisfaction.17,18 While some studies have evaluated the impact of these documents on the behavior of patients,5,19–25 few have been conducted in a general practice setting and most studies focus on only one specific theme (e.g. low back pain). This is why it appeared interesting to test information leaflets in several pathologies, so as to broaden the use of this tool.

As a result of the shortcomings, starting in 2007, we developed a methodology for the realization of patient information leaflets for general practitioners and suitable for use in primary care. We wrote 125 PIL for common clinical conditions encountered in general practice.26,27 In 2009, a prospective study evaluating six PIL with 350 patients8 showed that these PIL were popular with patients (96 % of them considered that doctors should use them more often) and were clearly understood in terms of knowledge about health issues (mean knowledge score of 22/24).

In the present study, our aim was to describe the impact of four of these PIL on the subsequent behavior of patients evaluating the specific effect of PIL, regardless of the pathological context.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This was a cluster randomized study in 30 primary care practices in France (Rhone-Alps, the Paris region and Provence-Alps Côte d’Azur), conducted between November 2009 and January 2011. The study was approved by the regional ethics committee (IRB n°5891) and the French National Agency for Information and Liberty (CNIL).

Population Studied

Patients were recruited from three regions of France by physicians who had volunteered to participate after being contacted by the Grenoble Clinical Research Center. The centre generated a computer list of random numbers for the randomization of physicians into two groups of 15 (with and without PIL).

All consecutive adults and children (<18 years old and accompanied by an adult) diagnosed with acute gastroenteritis or tonsillitis, and who could be contacted by telephone 10 to 15 days after the consultation, were informed of the study (orally and in a patient information letter). Patients with streptococcal infections were excluded. Physicians included patients in the study by completing a short inclusion-case report form describing the patient’s profile. Physicians in the PIL group gave the PIL (the intervention) corresponding to the patient’s condition to all the adults at, or towards the end of the consultation (Appendix: PIL in English available online). If the adult declined to participate, this was recorded.

The Intervention

Although 125 PIL have been written, we used only four in this study. This was a compromise; while we would have preferred to target more conditions, we felt it would be confusing for physicians to have to juggle more than four different PIL and also, we would have needed a much larger number of patients. Only acute (not chronic) conditions were studied, because we believe that it is not the role of PIL, a very simple device, to replace regular active patient education, as has been developed for diabetes or for asthma.30,31

The PILs selected concerned acute gastroenteritis and tonsillitis, two frequently encountered conditions of usually short duration (for adults and children). Physicians in the intervention group were instructed to refer to the PIL during the consultation. The leaflet was A4 size (210 × 297 mm), included an illustration related to the condition and information on the causes of the condition, its symptoms, the risks, the usual course of the disease, the treatments, and persisting or new symptoms which would require further medical consultation (Appendix available online).

Patient Follow-Up

Patients or their accompanying adult were contacted by telephone between 10 and 15 days after consultation with a doctor who did not participate in patient recruitment. They were asked a series of questions on their behavior since the consultation and their knowledge about the relevant condition.

Outcomes

The main outcome was the impact of each PIL on patient behavior, scored according to the condition (Table 1). Secondary outcomes were the patients’ knowledge regarding their condition (Table 2). Scores were calculated from replies to the telephone questionnaire, which contained questions common to all the conditions, and questions specific to the patient’s condition (Tables 1 and 2). Thus, for each diagnosed condition there was a specific PIL and a questionnaire. The questions and scoring systems were developed by an expert committee composed of five doctors, on the basis of recommendations from the French National Authority for Health consensus conferences and recent data in the literature.

Table 1.

Components of Behavior Questionnaire According to Diagnosis

| Type of question | Questions | Adult tonsillitis | Childhood tonsillitis | Adult gastroenteritis | Childhood gastroenteritis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic | 1. Are there any new cases in the household? | No | No | No | No |

| (If yes: Relationship to patient?)* | |||||

| Generic | 2. Did you consult a 2nd time for the same condition (other than when advised to according to in the PIL)? | No | No | No | No |

| Generic | 3. Has another member of the household consulted a physician for the same symptoms? | No | No | No | No |

| (If yes: Relationship to patient?)* | |||||

| Specific | 4a. Was close contact with others avoided during the episode? | Yes | Yes | ||

| Specific | 5a. Did you drink plenty of liquids? | Yes | Yes | ||

| (If yes: What did you drink?)a | |||||

| Specific | 6a. Have you taken any antibiotics? | No | No | ||

| (If yes: Who were they prescribed by?)* | |||||

| Specific | 4b. Have you changed what you eat during this episode | Yes | Yes | ||

| (What have you eaten?)* | |||||

| Specific | 5b. Did you wash your hands more often than usual during the episode of gastroenteritis? | Yes | Yes | ||

| (At what times of the day?) * | |||||

| Specific | 6b. Did you drink any Coca-Cola during the episode?† | No | No | ||

| (If yes: Was it Normal, ‘light’ or Pepsi cola?)* |

Patients were asked to answer each question with: ☐ Yes or ☐ No

Scoring: One point for each answer that was in line with the recommendations given in the PIL. No points for a different answer or for no answer. For each condition, the total score was out of 6. Thus, 6/6 = behavior follows recommendations given in PIL; 0/6 indicates inappropriate behavior

*The questions in parentheses are supplementary open questions asked to confirm the reply to the closed question. Only replies to closed questions were analyzed

†The PIL recommended ORS and that Cola drinks should be avoided (contrary to common beliefs)

Table 2.

Components of Knowledge Questionnaire According to Diagnosis

| Pathology | Questions | Incorrect answers | Correct answers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | 0 | 0.33 | 0.66 | 1.00 | |

| Tonsillitis in adults and children | 1. The rapid diagnostic test looks for the virus | Agree | Tend to agree | Tend to disagree | Disagree |

| 2. Viral tonsillitis cannot be treated with antibiotics | Disagree | Tend to disagree | Tend to agree | Agree | |

| 3. Viral tonsillitis is not contagious | Agree | Tend to Agree | Tend to disagree | Disagree | |

| 4. Mouthwashes can reduce the symptoms | Disagree | Tend to disagree | Tend to agree | Agree | |

| 5. Smoking and tobacco smoke have no influence on the course of the illness | Agree | Tend to agree | Tend to disagree | Disagree | |

| Gastroenteritis in adults and children | 1. Dehydration is the greatest risk of gastroenteritis | Disagree | Tend to disagree | Tend to agree | Agree |

| 2. Antibiotics speed up recovery from gastroenteritis | Agree | Tend to agree | Tend to disagree | Disagree | |

| 3. Gastroenteritis is not contagious | Agree | Tend to agree | Tend to disagree | Disagree | |

| Gastroenteritis: specific questions for children | 4a. Breast feeding should be temporarily stopped if gastroenteritis occurs | Agree | Tend to agree | Tend to disagree | Disagree |

| 5a. People in the child’s entourage should wash their hands frequently | Disagree | Tend to disagree | Tend to agree | Agree | |

| Gastroenteritis: specific questions for adults | 4b. One should preferably eat raw fruit and vegetables | Agree | Tend to agree | Tend to disagree | Disagree |

| 5b. Gastroenteritis can be passed to others via objects that have been touched by the patient | Disagree | Tend to disagree | Tend to agree | Agree | |

Patients were asked to answer each question with:

☐ Disagree, ☐ Not sure, tend to disagree, ☐ Not sure, tend to agree, or ☐ Agree

Scoring: 0, 0.33, 0.66 or 1 depending on degree of correctness. Total score out of 5: 5/5 = good knowledge; 0/5 poor knowledge

The phone questionnaire contained six closed behavioral questions (scored 0 or 1) and the total behavior score could vary from zero for completely inappropriate behavior, to six for behavior corresponding to the recommendations in the PIL. Five other questions (scored on a four item ordinal scale: 0, 0.33, 0.66 or 1 point) assessed the patient’s knowledge, giving a score from 0 (zero knowledge or comprehension) to five (good knowledge and/or complete understanding).

In a pilot study, we tested how well the questionnaires were perceived and answered by 30 patients; furthermore, the expert committee determined cut-off values for the main and secondary outcome measurements to give dichotomous variables for the assessment of efficacy. These were a score ≥ 5 for behavior that conformed to the PIL recommendations, and a score >3 for adequate knowledge about the condition.

Calculation of the Number of Subjects

We based our calculation of the number of subjects needed on the pilot study. Assuming a 25 % improvement in behavior between the two groups, the mean behavior score in the pilot study was four without PIL, and five with PIL. Thus, with a common standard deviation of 1.4, an error risk (α) of 5 %, a power of 90 %, an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.03 and 30 clusters, the number of subjects required would be 45 per group per condition; i.e. 360 patients. Allowing for 10 % patients to either refuse to answer the questionnaires or to be lost to follow-up, 400 patients were needed.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in intention to treat. Qualitative variables are expressed as number and frequency, and continuous variables as the mean and standard deviation. The two groups were compared in terms of all the demographic and clinical variables using the chi2 test for qualitative variables (with Fisher’s test as needed), and the Student t test for continuous variables. To take into account correlation between patients in the same primary care clinic, multi-level models with a random effect were used for all the univariate or multivariate analyses. The main outcome was also tested between the two groups using a linear multivariate model, and expressed as the effect size and the number needed to treat (NNT). The NNT represents the number of patients needed to receive a PIL to improve the behavior score for one patient. Correlation between the behavior and the knowledge scores was explored using a Pearson coefficient.

In multivariate analysis, on order to adjust for co-variables and/or to test for interactions, the primary and secondary endpoints were tested in two ways depending on the type of variable:

For continuous scores, a linear regression model that included interactions within the model (condition, age, sex and educational level) in a second step, was used.

To assess efficacy, scores were dichotomized according to cut-off values determined by the expert committee from pilot study data. With dichotomous scores, we used a logistic regression model in order to assess the role of PIL on behavior and knowledge, by adjustment of the variables sex, age, educational level, work in a medical setting, and employment status.

P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA® software, version 11 (Stata Corporation 4905 Lakeway Drive College Station, TX 77845 USA).

RESULTS

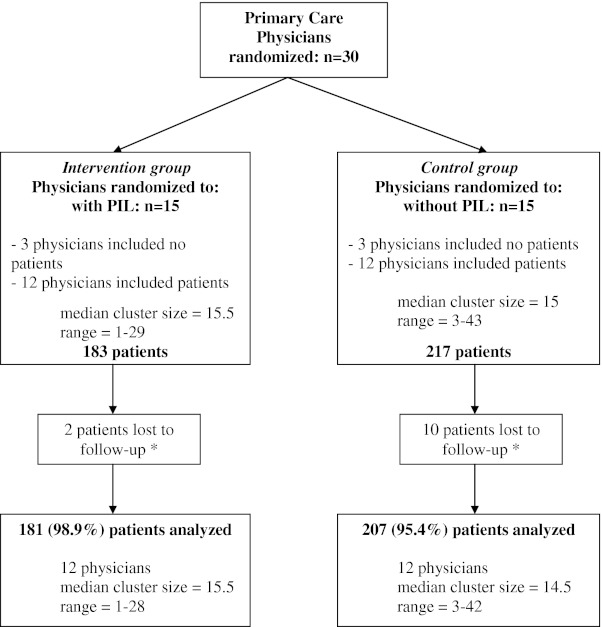

Thirty physicians in the three regional primary care networks agreed to participate in the study and were randomized. During the study period, 24 physicians included 400 patients aged between 2 months and 88 years (Fig. 1 and Table 3); six physicians did not include any patients on the pretext of lack of time. The physicians had a mean age of 46.1 years (SD: 10.8) and 70 % were male. They had been practicing for a mean of 16.8 years (SD: 12.1), and 83 % were part of a group primary care clinic that included doctors and sometimes a secretary, but no nurses or social workers. Half of the physicians practiced in an urban setting, 25 % in a semi-rural setting and 25 % in a rural context.

Figure 1.

Flow-diagram for the Patient Information Leaflet study. The coordinating centre was informed by fax of three eligible patients who declined to participate in the control group. PIL: Patient Information Leaflet. *Patients lost to follow-up were those who could not be contacted by telephone after 4 attempts.

Table 3.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study Population

| Characteristic | Total | PIL group | No PIL group |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 400) | (N = 183) | (N = 217) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Adult Patients | 246 (61.5) | 108 (59.0) | 138 (63.6) |

| Sex: Male | 96 (39.0) | 41 (38.0) | 55 (39.9) |

| *Age (mean +/− SD) | 35.7 (13.3) | 35.0 (13.3) | 36.3 (13.3) |

| In Employment (1 missing) | 185 (75.5) | 80 (74.8) | 105 (76.1) |

| Higher Education† (8 missing) | 113 (47.5) | 58 (54.2) | 55 (42.0) |

| Condition | |||

| Adult Tonsillitis | 97 (39.4) | 44 (40.7) | 53 (38.4) |

| Adult Gastroenteritis | 149 (60.6) | 64 (59.3) | 85 (61.6) |

| Child Patients | 154 (38.5) | 75 (41.0) | 79 (36.4) |

| Sex: Male | 83 (53.9) | 38 (50.7) | 45 (57.0) |

| *Age (months)(mean +/− SD) | 80.3 (42.5) | 82.3 (44.8) | 78.4 (40.5) |

| Condition | |||

| Childhood Tonsillitis | 75 (48.7) | 39 (52.0) | 36 (45.6) |

| Childhood Gastroenteritis | 79 (51.3) | 36 (48.0) | 43 (54.4) |

*Age: units are in years for adults and months for children, SD: standard deviation

†Higher education means studies after graduating from high school

In all, 246 adult patients consulted a physician, and 154 adults accompanied a sick child; of these, 97 % (388) replied to the telephone questionnaire. There were no significant differences between the ‘with’ and ‘without PIL’ patients at baseline. Table 3 shows that the two groups are comparable in terms of their socio-demographic characteristics.

Main Objective

For the whole population (adults and adults accompanying children), those in the PIL group significantly showed behavior that was closer to that recommended by the PIL than those in the group that had not received a PIL (mean behavior score 4.9 versus 4.2, p < 0.01) (Table 4). This was confirmed by the alternative analytical approach, where the behavior scores were dichotomized and used in univariate analysis (recommended behavior 71.8 % versus 43.0 %, p < 0.01). Likewise, those in the PIL group had a mean knowledge score that was significantly higher than those in the control group (mean knowledge score 4.2 versus 3.6, p < 0.01) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of Scores by Group for the Whole Study Population

| Scores | With PIL | Without PIL | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 181 | n = 207 | ||

| Behavior Score | |||

| - As a continuous value/6 points | |||

| Mean (+/− SD) | 4.9 (+/− 1.0) | 4.2 (+/− 1.2) | < 0.01 |

| Effect size [CI 95 %] | 0.60 [0.40 to 0.79] | ||

| - As a dichotomous variable: scores ≥ 5 | |||

| n (%) | 130 (71.8 %) | 89 (43.0 %) | < 0.01 |

| Number needed to treat | 3.5 | ||

| Multivariate Odds Ratio [CI 95 %] * | 5.0 [2.6 – 9.4] | < 0.01 | |

| Knowledge Score | |||

| - As a continuous value/5 points | |||

| Mean (+/− SD) | 4.2 (+/− 0.8) | 3.6 (+/− 1.1) | < 0.01 |

| Effect size [CI 95 %] | 0.56 [0.36 to 0.76] | ||

| - As a dichotomous variable: scores > 3 | |||

| n (%) | 153 (84.5 %) | 128 (61.8 %) | < 0.01 |

| Number needed to treat | 4.4 | ||

| Multivariate Odds Ratio [CI 95 %] * | 5.0 [1.9 – 13.2] | < 0.01 |

*The multivariate odds ratio is obtained from a logistic regression model adjusted for the variables: gender, age, educational level, work in a medical setting, and employment status(only among adult patients n = 224)

The adult patient subgroup showed behavior that was closer to that recommended by the PIL than adult patients in the control group (mean behavior score 4.9 versus 4.0, p < 0.01) (Table 5). The adults accompanying children subgroup showed the same tendency, but did not reach significance (mean behavior score 4.9 versus 4.5, p = 0.11) (Table 5). There was interaction between the variables ‘with PIL’ or ‘without’ PIL, and child or adult patient (p = 0.013). Indeed, in the group without PIL, the behavior of the accompanying adults at the time of evaluation was closer to recommended behavior than for adult patients. This difference between accompanying and sick adults did not occur in the intervention groups (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of Behavior Scores With and Without a PIL by Condition

| Behavior Score | With PIL* | Without PIL* | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| All included patients | |||

| TONSILLITIS | 5.2 (+/− 0.9) | 4.3 (+/− 1.1) | < 0.01 |

| (n = 44) | (n = 51) | ||

| CHILDHOOD TONSILLITIS | 4.8 (+/− 0.9) | 4.6 (+/− 1.1) | 0.37 |

| (n = 39) | (n = 35) | ||

| GASTROENTERITIS | 4.8 (+/− 1.0) | 3.8 (+/− 1.2) | < 0.01 |

| (n = 62) | (n = 78) | ||

| CHILDHOOD GASTROENTERITIS | 4.9 (+/− 0.9) | 4.5 (+/− 1.2) | 0.05 |

| (n = 36) | (n = 43) | ||

| Adult patients only | |||

| All | 4.9 (+/− 1.0) | 4.0 (+/− 1.2) | < 0.01 |

| (n = 106) | (n = 129) | ||

| Children only | |||

| All | 4.9 (+/− 0.9) | 4.5 (+/− 1.1) | 0.11 |

| (n = 75) | (n = 78) |

*Mean (+/− SD)

For the adult patient subgroup, knowledge was significantly better in the group that received a PIL (mean knowledge score 4.2 versus 3.5, p < 0.01), irrespective of the condition studied or of socio-demographic parameters (with the exception of the level of education where the difference was not significant) (Table 6). There was significant interaction between receiving a PIL or not, and the level of education (p = 0.026). Indeed, while patients who had pursued higher education had a better understanding of their condition in the control group, such a difference was not observed in the intervention group. The correlation coefficient between the behavior and knowledge scores was 0.18 with p < 0.01. In exploratory analyses, the effect of PIL on knowledge and behavior did not vary across age and sex.

Table 6.

Comparison of Knowledge Scores With and Without a PIL by Condition

| Knowledge Score | With PIL* | Without PIL* | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| All included patients | |||

| TONSILLITIS | 3.9 (+/− 0.9) | 2.9 (+/− 0.9) | < 0.01 |

| (n = 44) | (n = 51) | ||

| CHILDHOOD TONSILLITIS | 3.7 (+/− 0.9) | 3.1 (+/− 1.1) | < 0.01 |

| (n = 39) | (n = 35) | ||

| ADULT GASTROENTERITIS | 4.4 (+/− 0.7) | 3.9 (+/− 0.9) | < 0.01 |

| (n = 62) | (n = 78) | ||

| CHILDHOOD GASTROENTERITIS | 4.5 (+/− 0.5) | 4.1 (+/− 0.8) | < 0.01 |

| (n = 36) | (n = 43) | ||

| Adult Patients only | |||

| All | 4.2 (+/− 0.8) | 3.5 (+/− 1.1) | < 0.01 |

| (n = 106) | (n = 129) | ||

| Children only | |||

| All | 4.1 (+/− 0.8) | 3.6 (+/− 1.1) | < 0.01 |

| (n = 75) | (n = 78) |

*Mean (+/− SD)

Due to missing data on adults who accompanied sick children, multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed only on the sick adult population (224 patients). Here again, patients who had received a PIL were significantly more likely to exhibit recommended behavior (see Table 4 for multivariate odds ratios). Likewise, adult patients over age 40 were more likely to exhibit recommended behavior (OR = 2.16, p = 0.02) and have better knowledge (OR = 2.23, p = 0.04) about their condition than younger adult patients. Lastly, patients who were employed understood their condition better (OR = 2.18, p = 0.05), but changed their behavior less, than those who did not work (OR = 0.44, p = 0.02).

Among new cases within a household, the number of household members consulting for the same symptoms was lower in the intervention group than in the control group (23.4 % vs. 56.2 %, p <0.01).

DISCUSSION

Patient information leaflets given to patients to complement oral information led to significantly better compliance with behavior recommended by the guidelines, and better knowledge of their condition. In addition, PIL helped to reduce the number of consultations considered as unnecessary, according to the recommendations given in the PIL under the heading “contact you doctor”, by other household members who had contracted the same infection; PIL also erased the inequalities in knowledge related to the level of education. The results were consistent for all four PIL, whether they concerned an adult or a childhood condition, and suggest that the use of PIL can improve the behavior and increase patients’ knowledge about their condition for the pathologies tested.

Comparison with Other Studies

Several studies have shown the benefit of PIL for different criteria, for example for acute low back pain,19,23 where the advantages of PIL were assessed by reduction in pain or decrease in functional disability, rather than by evaluating behavior. Other studies have focused either on the patients’ knowledge of the pathology,15 on patient satisfaction,8,9 or on the autonomy of patients.19,21,28 In our study, adult patients in the PIL group behaved in a manner that was closer to the recommended behavior than those in the control group, for both conditions. For the child patient subgroup, the results showed the same tendency, but did not reach significance. It is likely that this difference between adult and childhood contexts occurs because the accompanying adults become far more concerned when the condition affects their child, or a child in their care, compared to themselves. Parents seem more likely to follow the physician’s instructions when they concern the well-being of their child (rather than themselves), with or without the use of a PIL, and this makes the impact of the PIL less clear. Indeed, in the group without PIL, the behavior of the accompanying adult subgroup was more in line with recommended behavior from the outset, compared to the adult patient group. Likewise, knowledge scores were higher for childhood conditions than for adult conditions.

Regarding knowledge about the condition, for all four conditions, the scores were better in the groups which received a PIL (Table 6). As may be expected, patients in the group without PIL who had attended higher education showed better knowledge about the condition.10 In the group that received a PIL, differences in knowledge linked to differences in educational level were not found. The use of a PIL therefore promotes equality of knowledge, regardless of the level of education. A PIL has an impact on the entourage of patients; those who were close to patients in the PIL group and who contracted the same symptoms consulted less than household members of patients who had not received a PIL. This suggests a spontaneous sharing of information, as noted by Vetto.17 Only a weak correlation was found between behavior and knowledge about the condition, as in the “Back Home Trial”.22 On return home, the written information allows patients to remind themselves of the doctor’s advice, which could improve compliance with the treatment and better adherence to the recommendations.5 It should be noted that patients who were employed showed better knowledge of their condition but were less likely to change their behavior, perhaps due to time constraints. Furthermore, patients under 40 years showed poorer knowledge and were less prone to adjust their behavior, although there was no direct link between age and working status.

Biases and Limitations of the Study

We found no published validated scoring system to evaluate the knowledge or behavior of patients presenting the conditions we studied. We thus constructed a scoring system based on the consensus of five experts, using a methodology validated by the French National Authority for Health.29 The same method was used for all conditions, but was adapted to each condition. In the pilot study, we had validated the comprehensibility of the questionnaires, as well as the discriminatory character of the scores. The recruitment of physicians was done on a voluntary basis, which may have selected doctors who supported the hypothesis of the study. As the interviews were by telephone, patients were able to answer the questions without having really followed the practical advice given.24 To monitor this measurement bias, we asked two questions (re-consultation by the patients themselves and whether relatives had consulted the physician for the same symptoms), for which the answers could be verified from the clinic’s records (Table 1).

CONCLUSION

Our study has shown that the four PIL studied significantly improved patient knowledge and increased patient autonomy by inducing behavior closer to that recommended by the guidelines. It has particularly shown that PIL promote: 1) egalitarian access to knowledge by eliminating differences related to level of education, and 2) a reduction in consultations by members of the patient’s entourage, who develop similar symptoms. The homogeneity of the results argues in favor of a specific effect of PIL, regardless of the pathological context. These results deserve to be confirmed by other studies. In particular, it is important to find and evaluate methods of communication aimed at younger and professionally active patients to encourage them to change their behavior when they are ill.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOC 662 kb)

Acknowledgements

Contributors

We thank Carole Rolland for managing the study (Grenoble CIC) and Aurélia Meneau for participating in the study design. We also thank Philippe Eveillard for critically reading the manuscript. We thank the following physicians for their participation: Baud N, Blanckemane M, Boivin JE, Brin M, Constans D, Corchia L, Dauphin D, Demaret F, D’Herouville C, Dubayle V, Folacci JL, Gamby A, Gandiol J, Genthon A, Gozlan E, Guetta B, Lagabrielle D, Lamy D, Leclercq A, Moulle C, Lambert P, Magnen L, Menuret H, Poucel F, Rony N, Schihin R, Triviella F, Verjus P, Vignoulle JL, and Zerbib Y for joining us in the expert committee

Funding

The study was supported by the Grenoble Clinical Research Centre, which is financed by INSERM and French hospital funding, both belonging to the public sector. Neither INSERM nor the hospital influenced the study design, analysis or interpretation of results.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01398696

REFERENCES

- 1.Dunkelman H. Patients’ knowledge of their condition and treatment: how it might be improved. BMJ. 1979;2(6185):311–314. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6185.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shank JC, Murphy M, Schulte-Mowry L. Patient preferences regarding educational pamphlets in the family practice center. Fam Med. 1991;23(6):429–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziegler DK, Mosier MC, Buenaver M, Okuyemi K. How much information about adverse effects of medication do patients want from physicians? Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(5):706–713. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.5.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nair K, Dolovich L, Cassels A, et al. What patients want to know about their medications. Focus group study of patient and clinician perspectives. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:104–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenny T, Wilson RG, Purves IN, et al. A PIL for every ill? Patient information leaflets (PILs): a review of past, present and future use. Fam Pract. 1998;15(5):471–479. doi: 10.1093/fampra/15.5.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitching JB. Patient information leaflets—the state of the art. J R Soc Med. 1990;83(5):298–300. doi: 10.1177/014107689008300506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Little P, Dorward M, Warner G, et al. Randomized controlled trial of effect of leaflets to empower patients in consultations in primary care. BMJ. 2004;328(7437):441. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37999.716157.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sustersic M, Voorhoeve M, Menuret H, Baudrant M, Meneau A, Bosson JL. Fiches d’information pour les patients: quel intérêt? L’étude EDIMAP. La Rev méd gén. 2010;276:332–339. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Little P, Griffin S, Kelly J, Dickson N, Sadler C. Effect of educational leaflets and questions on knowledge of contraception in women taking the combined contraceptive pill: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 1998;316(7149):1948–1952. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7149.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pernod G, Labarere J, Yver J, et al. EDUC’AVK: reduction of oral anticoagulant-related adverse events after patient education: a prospective multicenter open randomized study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1441–1446. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0690-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mainous AG, 3rd, Hueston WJ, Love MM, Evans ME, Finger R. An evaluation of statewide strategies to reduce antibiotic overuse. Fam Med. 2000;32(1):22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health. Better information, better choices, better health: putting information at the center of health. 2004; Available at: ttp://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/DH_4098576 (last accessed June 2012).

- 13.HAS. Methodology guide: How to produce an information brochure for patients and users of the healthcare system. Available at: http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/jcms/c_430286 (last accessed June 2012).

- 14.Arthur VAM. Written patient information—a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 1995;21:1081–1086. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.21061081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watkins CJ, Papacosta AO, Chinn S, Martin J. A randomized controlled trial of an information booklet for hypertensive patients in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1987;37(305):548–550. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scala D, Cozzolino S, D’Amato G, et al. Sharing knowledge is the key to success in a patient-physician relationship: how to produce a patient information leaflet on COPD. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2008;69(2):50–54. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2008.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vetto JT, Dubois PM, Vetto IP. The impact of distribution of a patient-education pamphlet in a multidisciplinary breast clinic. J Cancer Educ. 1996;11(3):148–152. doi: 10.1080/08858199609528418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leichtnam-Dugarin L, Carretier J, Delavigne V, et al. The SOR SAVOIR Patient, a project of patient information and education. Cancer Radiother. 2003;7(3):210–212. doi: 10.1016/S1278-3218(03)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roland M, Dixon M. Randomized controlled trial of an educational booklet for patients presenting with back pain in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1989;39(323):244–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobson TA, Thomas DM, Morton FJ, Offutt G, Shevlin J, Ray S. Use of a low-literacy patient education tool to enhance pneumococcal vaccination rates. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282(7):646–650. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macfarlane J, Holmes W, Gard P, Thornhill D, Macfarlane R, Hubbard R. Reducing antibiotic use for acute bronchitis in primary care: blinded, randomized controlled trial of patient information leaflet. BMJ. 2002;324(7329):91–94. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts L, Little P, Chapman J, Cantrell T, Pickering R, Langridge J. The back home trial: general practitioner-supported leaflets may change back pain behavior. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27(17):1821–1828. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200209010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coudeyre E, Givron P, Vanbiervliet W, et al. The role of an information booklet or oral information about back pain in reducing disability and fear-avoidance beliefs among patients with subacute and chronic low back pain. A randomized controlled trial in a rehabilitation unit. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2006;49(8):600–608. doi: 10.1016/j.annrmp.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mansoor L, Dowse R. Written medicines information for South African HIV/AIDS patients: does it enhance understanding of co-trimoxazole therapy? Health Educ Res. 2007;22(1):37–48. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francis NA, Butler CC, Hood K, Simpson S, Wood F, Nuttall J. Effect of using an interactive booklet about childhood respiratory tract infections in primary care consultations on reconsulting and antibiotic prescribing: a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:2885. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sustersic M, Meneau A, Dremont R, Bosson JL. Fiches d’information patient: quelle méthodologie? La rev prat Méd gén. 2007;790:1167–1168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sustersic M, Meneau A, Drémont R, Paris A, Laborde L, Bosson JL. Elaboration de fiches d’information pour les patients en médecine générale. Rev Prat. 2008;58(S):17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paris A, Nogueira da Gama Chaves D, Cornu C, et al. Improvement of the comprehension of written information given to healthy volunteers in biomedical research: a single-blind randomized controlled study. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2007;21(2):207–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2007.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.HAS. Guide méthodologique - Bases méthodologiques pour l’élaboration de recommandations professionnelles par consensus formalisé. Available at: http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/jcms/c_240386 (last accessed June 2012).

- 30.World Health Organization - Europe. Therapeutic Patient Education - Continuing Education Programmes for HealthCare Providers in the Field of Prevention of Chronic Diseases. 1998; www.euro.who.int/document/e63674.pdf (last accessed June 2012)

- 31.Paul F, Jones MC, Hendry C, Adair PM. The quality of written information for parents regarding the management of a febrile convulsion: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(12):2308–2322. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 662 kb)