Summary

A specific mutation (ΔE) in torsinA underlies most cases of the dominantly inherited movement disorder, early-onset torsion dystonia (DYT1). TorsinA, a member of the AAA+ ATPase superfamily, is located within the lumen of the nuclear envelope (NE) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER). We investigated an association between torsinA and nesprin-3, which spans the outer nuclear membrane (ONM) of the NE and links it to vimentin via plectin in fibroblasts. Mouse nesprin-3α co-immunoprecipitated with torsinA and this involved the C-terminal region of torsinA and the KASH domain of nesprin-3α. This association with human nesprin-3 appeared to be stronger for torsinAΔE than for torsinA. TorsinA also associated with the KASH domains of nesprin-1 and -2 (SYNE1 and 2), which link to actin. In the absence of torsinA, in knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), nesprin-3 was localized predominantly in the ER. Enrichment of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-nesprin-3 in the ER was also seen in the fibroblasts of DYT1 patients, with formation of YFP-positive globular structures enriched in torsinA, vimentin and actin. TorsinA-null MEFs had normal NE structure, but nuclear polarization and cell migration were delayed in a wound-healing assay, as compared with wild-type MEFs. These studies support a role for torsinA in dynamic interactions between the KASH domains of nesprins and their protein partners in the lumen of the NE, with torsinA influencing the localization of nesprins and associated cytoskeletal elements and affecting their role in nuclear and cell movement.

Keywords: Nesprin, Dystonia, Cell migration, Nuclear polarization, DYT1, Vimentin, Actin

Introduction

Early-onset generalized torsion dystonia (DYT1) is a severe, dominantly inherited movement disorder with onset in childhood and limited therapeutic options (Breakefield et al., 2008; Kamm et al., 2008). Most cases of DYT1 are caused by a specific mutation (ΔGAG) resulting in loss of a glutamic acid in the C-terminal region of torsinA (Ozelius et al., 1997). The mutant form of torsinA, torsinAΔE, appears to have a loss of function and to act in a dominant-negative manner to decrease function of wild-type torsinA (Goodchild et al., 2005; Dang et al., 2006; Pham et al., 2006; Hewett et al., 2008). Dystonic symptoms are believed to arise from abnormal functioning of neurons in the brain with no apparent neuronal loss (Rostasy et al., 2003; McNaught et al., 2004). Polymorphisms in the TOR1A gene (Ozelius et al., 1997) have been implicated in adult-onset focal forms of dystonia through genetic association studies (Clarimon et al., 2005; Kamm et al., 2006).

TorsinA is a member of the AAA+ (associated with a variety of cellular activities) superfamily of ATPases based on homology and configurational alignment (Ozelius et al., 1997; Neuwald et al., 1999; Lupas et al., 1997; Kock et al., 2006). These proteins typically form six-membered oligomeric complexes, usually associate with one or more additional proteins, and share Mg2+-ATP-binding domains, ATPase activity and secondary structure. AAA+ proteins mediate conformational changes in other proteins and perform a variety of functions, including correct folding of nascent proteins, unfolding of proteins for degradation, and dynamic interactions between proteins involved in signaling, membrane trafficking and organelle biogenesis/movement (for a review, see Hanson and Whiteheart, 2005).

TorsinA is predominantly localized in the contiguous lumen of the nuclear envelope (NE) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Hewett et al., 2003; Kustedjo et al., 2000; Callan et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2003), and presumably interacts with transmembrane proteins concentrated in these locales. TorsinA is associated with lamin-associated polypeptide 1 (LAP1; TOR1AIP1) in the inner nuclear membrane(INM) of the NE and with LULL1 (TOR1AIP2) in the ER/NE (Goodchild and Dauer, 2005; Naismith et al., 2004), as well as with conventional kinesin light chain 1 (KLC1) (Kamm et al., 2004), vimentin and actin (Hewett et al., 2006) in the cytoplasm. The function of torsinA is unknown, but studies support a role in the structure of the NE (Goodchild et al., 2005; Naismith et al., 2004) and in the processing of proteins through the secretory pathway(Torres et al., 2004; Hewett et al., 2007; Hewett et al., 2008).

The present study was initiated based on our findings of coordinated movement of torsinA and vimentin during cellular recovery from microtubule dissociation (Hewett et al., 2006). Vimentin intermediate filaments (IFs) form a net around the NE and are involved in defining nuclear shape and mediating nuclear movement (Djabali, 1999). Cells lacking vimentin have abnormally shaped nuclei with invaginations (Sarria et al., 1994) and a reduced rate of migration as compared with control cells in wound assays (Eckes et al., 1998). Vimentin also participates in the distribution of NE membrane/LAP1-containing vesicles during mitosis (Maison et al., 1997), in the movement of the ER during cell migration(Eckes et al., 1998), and in early neurite outgrowth (Dubeyet al., 2004). Loss of a nematode ortholog of torsinA, OOC-5, disrupts nuclear rotation during early embryogenesis (Basham and Rose, 2001).

The structure, shape and movement of the nucleus is maintained, at least in part, by interactions between proteins, such as the SUNs, which span the INM and interact with the IF lamins in the nucleus, and the nesprins (SYNEs), which span the outer nuclear membrane (ONM) and link to cytoskeletal elements, including IFs, microtubules and actin microfilaments, in the cytoplasm (Crisp et al., 2006; Starr and Fischer, 2005; Wilhelmsen et al., 2006). The SUN domain of INM proteins interacts with the KASH domain of nesprins in the lumenal space. Nesprin-1 and -2 (SYNE1 and 2) interact with actin microfilaments, UNC-83(in nematodes) interacts with microtubules, and mouse nesprin-3α (the homolog of human nesprin-3) interacts with the cytolinker/plakin, plectin (Wilhelmsen et al., 2005; Wilhelmsen et al., 2006), which in turn links to IFs (Sonnenberg and Liem, 2007). Like the other nesprins, nesprin-3 is a type II transmembrane protein and contains a C-terminal KASH domain that lies within the lumenal space of the NE. Unlike nesprin-1 and -2, nesprin-3 lacks an actin-binding domain (ABD) and is therefore unable to associate with actin directly, but forms an interconnected mesh with actin microfilaments, microtubules and IFs through plakins (Wilhelmsen et al., 2006; Chang and Goldman, 2004; Herrmann et al., 2007). Recent commentaries on the links between the NE and cytoskeleton have suggested a possible role for torsinA in modulating the interaction between SUNs and nesprins within the NE lumen (Gerace, 2004; Worman and Gundersen, 2006).

In this study, we have investigated the association between torsinA in the NE and plectin/vimentin in the cytoplasm in primary cultures of torsinA-null and control mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), human skin fibroblasts from DYT1 patients and controls, mouse pup fibroblasts (MFs) and human 293T cells, using recombinant proteins, immunoprecipitation, pull-downs, immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy. We found that torsinA associates with the C-terminal KASH domains of nesprin-3α, nesprin-1 and nesprin-2. Under some conditions, the DYT1 mutant form of torsinA, torsinAΔE, associated more strongly with human nesprin-3 than did torsinA. TorsinA-null MEFs showed reduced polarization of nuclei relative to the centrosome, and delayed migration in wound-healing assays. These studies support a role for torsinA in modulating dynamic interactions between the KASH domain of nesprins and their binding partners in the lumen of the NE, with torsinA loss causing anenrichment of nesprin-3 in the ER.

Results

Interaction between torsinA and mouse nesprin-3α, plectin and vimentin

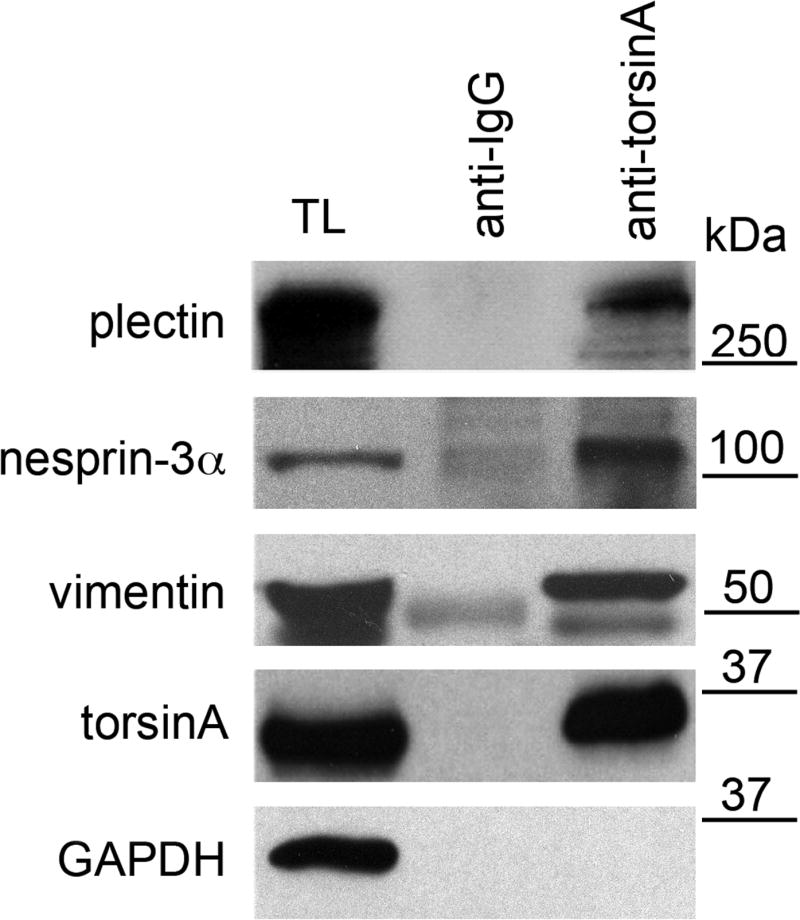

Immunoprecipitations carried out in previous studies showed associations between torsinA, vimentin and actin (Hewett et al., 2006) and between nesprin-3α, plectin and vimentin (Wilhelmsen et al., 2005; Wilhelmsen et al., 2006). In order to evaluate whether endogenous torsinA participates in a composite complex that includes these proteins, we carried out immunoprecipitations of torsinA using lysates of wild-type MFs (Andra et al., 2003). Immunoprecipitations were performed in RIPA buffer using antibodies to torsinA (D-M2A8 and D-MG10, 1:1) and to immunoglobulin G (anti-IgG) as a control. Proteins in lysates and precipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and blots probed with antibodies to plectin (300 kDa), nesprin-3α (120 kDa), vimentin (55 kDa), torsinA (37 kDa) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 36 kDa) (Fig. 1). Nesprin-3α, plectin and vimentin co-immunoprecipitated with torsinA, with very little or no co-immunoprecipitation of the cytoplasmic control protein GAPDH. This demonstrates an association between endogenous torsinA, nesprin-3α, plectin and vimentin in fibroblasts.

Fig. 1.

Association of endogenous nesprin-3α, plectin and vimentin with torsinA. Lysates from wild-type MFs were immunoprecipitated at 4°C overnight with antibodies to torsinA (D-M2A8 and DMG-10, 1:1) or IgG (anti-mouse IgG) without added ATP. Immunoprecipitates and lysates were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblotted with antibodies to plectin, nesprin-3, vimentin, torsinA and GAPDH. TL, total lysates. The position of MW markers is indicated. The experiment was repeated three times and representative blots are shown. The percentage of each protein immunoprecipitated from lysates is: 7±2% for plectin, 17±4% for nesprin-3α, 17±3% for vimentin,12±3% for torsinA (values are mean percentage ± s.e.m., n=3 experiments).

Association of torsinA and torsinAΔE with human nesprin-3

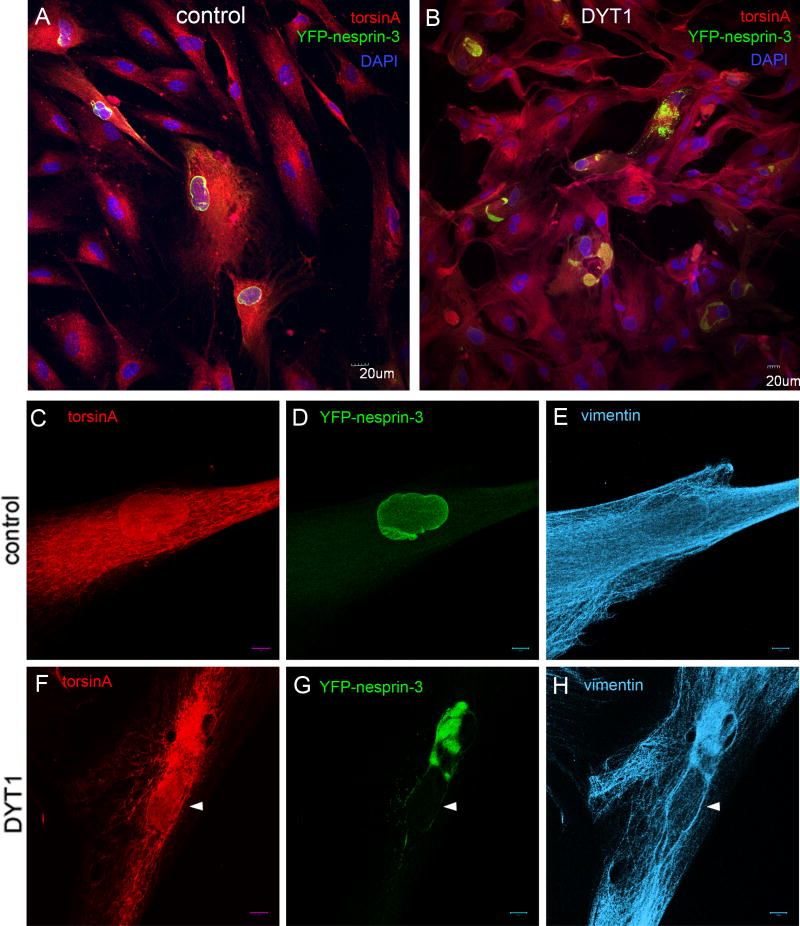

In order to evaluate the potential relevance of the torsinA-nesprin-3 association in DYT1 dystonia, we evaluated the relative association of torsinA and torsinAΔE in this complex. Human nesprin-3 exhibits 94.5% homology with mouse nesprin-3α, and shares the plectin-binding domain (PBD) (supplementary material Fig. S1). As no anti-human-nesprin-3 antibody is available, we used a tagged version consisting of human nesprin-3 fused in-frame at the N-terminus to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), termed YFP-nesprin-3. When this fusion protein was expressed in control primary human fibroblasts via a lentivirus vector, most fluorescence was found around the nucleus, typical of the localization of nesprin-3α described in mouse cells (Wilhelmsen et al., 2005) (Fig. 2A,D). Immunocytochemical staining of control cells expressing YFP-nesprin-3 showed a typical distribution of torsinA in the NE/ER (Fig. 2C) and of vimentin in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2E). By contrast, in DYT1 fibroblasts, YFP-nesprin-3 accumulated in globular structures, presumably within the lumen of the ER (Fig. 2B,G). These YFP+ globular structures were also enriched for torsinA (Fig. 2F), vimentin (Fig. 2H) and actin (supplementary material Fig. S2). These findings suggested that the presence of torsinAΔE inhibited the interaction of YFP-nesprin-3 with other binding partners in the NE, leading to an aggregation of overexpressed YFP-nesprin-3, cytoskeletal binding partners and torsinA-immunoreactive protein primarily in the ER.

Fig. 2.

Differential distribution of YFP-nesprin-3 in DYT1 and control human fibroblasts. Primary skin fibroblasts from controls and DYT1 subjects were infected with a lentivirus vector expressing YFP-nesprin-3 and fixed 72 hours later. (A,B) Cells were immunostained for torsinA and GFP, with DAPI staining of nuclei. In control cells, YFP-nesprin is primarily localized in the perinuclear region (A), whereas in DYT1 cells it accumulates in globular structures presumably within the ER/NE (B); this was seen in two different cell lines of each type. (C–E) Immunocytochemical staining of infected control cells showing a typical distribution of torsinA (ER/NE) and vimentin (cytoplasm), with YFP-nesprin-3 primarily localized around the nucleus. (F–H) Staining of infected cells from DYT1 patients showing increased concentration of both torsinA and vimentin in the region of YFP-nesprin-3 globular structures. White arrowheads indicate nuclei. Scale bars: 20 μm in A,B; 10 μm in C–H.

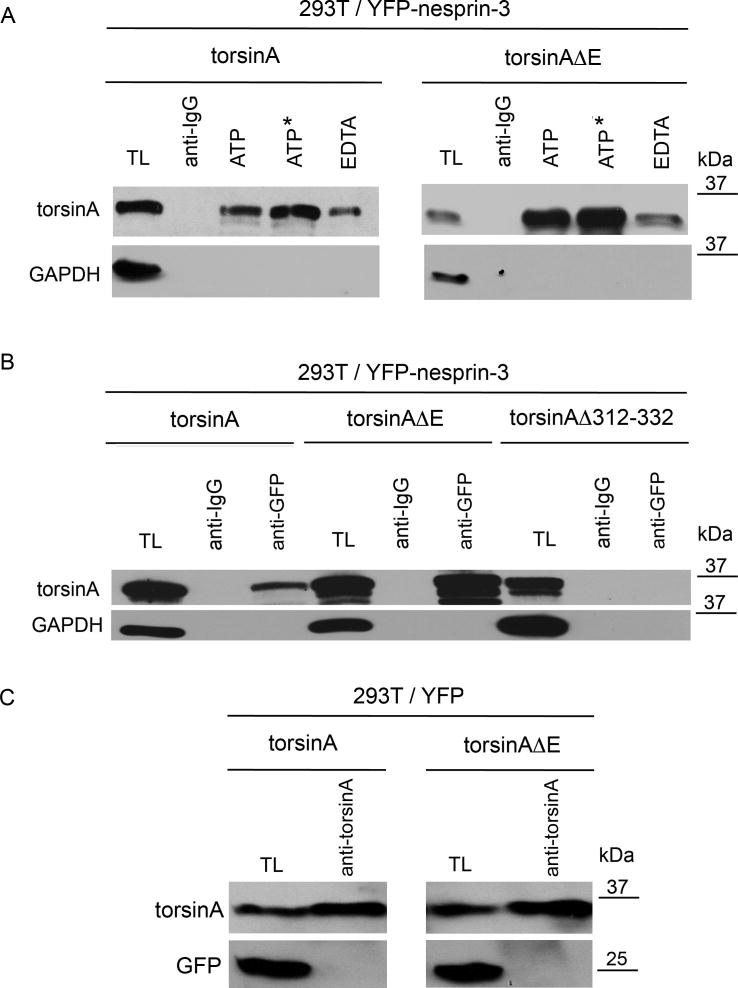

To further evaluate the association of YFP-nesprin-3 and torsinA we carried out immunoprecipitation from 293T cells co-transfected with YFP-nesprin-3 and torsinA or torsinAΔE expression cassettes. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies to green fluorescent protein (GFP) (which also recognize YFP) and IgG (as a control), followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies for torsinA and GAPDH. Because ATP is involved in the interaction of AAA+ proteins with their substrates, immunoprecipitations were carried out in the presence of 1 mM ATP, non-hydrolysable ATP, or EDTA (with no added ATP) to evaluate the role of ATP in torsinA-nesprin-3 interactions. Both torsinA and torsinAΔE were more efficiently immunoprecipitated with YFP-nesprin-3 in the presence of ATP or non-hydrolysable ATP than of EDTA (Fig. 3A). TorsinA and torsinAΔE were not found to associate with IgG and showed no co-immunoprecipitation with GAPDH (Fig. 3A). In the presence of ATP, less torsinA (8±0.57%, n=3) was immunoprecipitated with YFP-nesprin-3 than torsinAΔE (25±0.88%, n=3, P<0.0001, two-way ANOVA). These findings suggest that the association of both torsinA and torsinAΔE with YFP-nesprin-3 is enhanced by ATP, and that there is a tighter association of torsinAΔE than of torsinA with YFP-nesprin-3.

Fig. 3.

Association of torsinA and torsinAΔE with nesprin-3. (A) Human 293T cells were co-transfected with expression cassettes for YFP-nesprin and either torsinA or torsinAΔE. Immunoprecipitations were carried out in the presence of 1 mM ATP, non-hydrolysable ATP or EDTA (the latter with no added ATP) in RIPA buffer with antibody to GFP or with anti-rabbit IgG as control. Immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies to torsinA (D-M2A8) or GAPDH. On average, threefold more torsinAΔE was immunoprecipitated than torsinA (3.0±0.88, n=3, P<0.0001, ANOVA). (B) Experiments were carried out as in A except that transfections were with expression cassettes for torsinA, torsinAΔE or torsinAΔ312–322. The additional bands under the predominant 37-kDa torsinA band presumably represent the non- and partially glycosylated forms seen in other studies (Hewett et al., 2004). (C) To verify that torsinA and torsinAΔE bind to nesprin-3 and not to YFP, 293T cells were co-transfected with expression cassettes for YFP and either torsinA or torsinAΔE. Immunoprecipitations were carried out in the presence of 1 mM ATP in RIPA buffer with antibody to torsinA. Immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies to torsinA (D-M2A8) or GFP.

Our laboratory has previously shown that overexpression of torsinB, which is highly homologous to torsinA (Ozelius et al., 1997), or of torsinAΔE, leads to an enrichment of immunoreactive protein in the ER and perinuclear region in large inclusion bodies (Hewett et al., 2004). We evaluated the association between endogenous torsinB and YFP-nesprin-3 in 293T cells (supplementary material Fig. S3). Antibodies to torsinB were able to immunoprecipitate YFP-nesprin-3, indicating that both torsinB and torsinA can associate with nesprin-3 and thus might carry out related functions in the NE.

To evaluate whether the C-terminal region of torsinA is involved in the association with nesprin-3, 293T cells were co-transfected with YFP-nesprin-3 and torsinA, torsinAΔE or torsinAΔ312–332 (Fig. 3B). Forty-eight hours post-transfection, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies to GFP and IgG (as a control), followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies for torsinA and GAPDH. Again, torsinAΔE associated more tightly with YFP-nesprin-3 than did torsinA, whereas there was no association of YFP-nesprin-3 with torsinAΔ312–332, indicating that the C-terminal region of torsinA is necessary for this association. To certify that torsinA binds specifically to nesprin-3 and not to YFP, 293T cells were also co-transfected with YFP and torsinA or torsinAΔE (Fig. 3C). Forty-eight hours post-transfection, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies to torsinA followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies for torsinA and GFP. TorsinA or torsinAΔE did not immunoprecipitate YFP alone. Our recent results, and those by Phyllis Hanson’s group (School of Medicine, Washington University in St Louis, MO; personal communication), suggest that torsinA has two independent binding domains: one in the N-terminal α-β sub-domain of the AAA+ domains that binds LULL1 and LAP1 (transmembrane proteins in the INM), and one in the C-terminal α-helical sub-domain that binds the KASH domain of nesprins. It remains to be tested whether torsinA can bind both types of partners simultaneously.

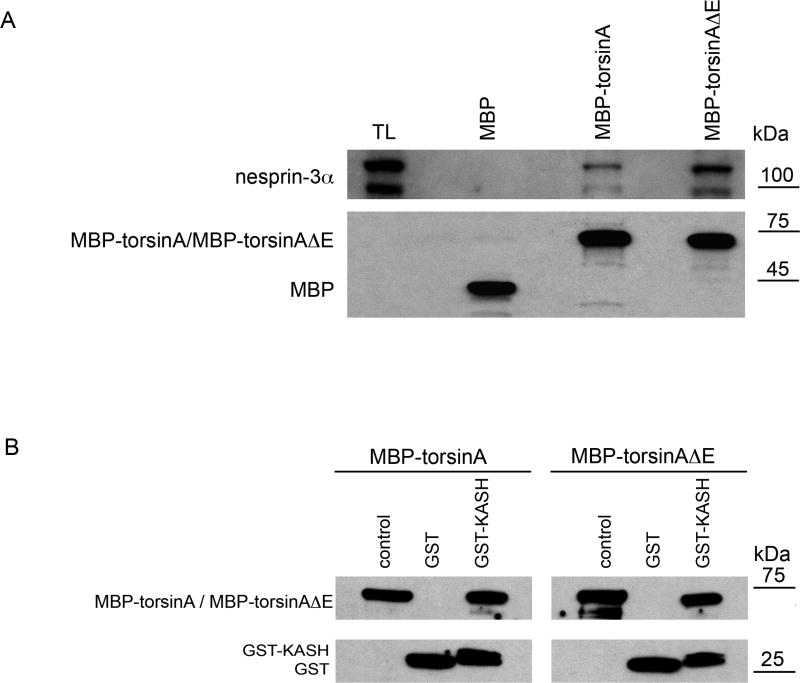

A difference in the binding of torsinA and torsinAΔE to nesprin-3α was also detected in pull-down experiments using recombinant maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusion proteins of torsinA. Both MBP-torsinA and MBP-torsinAΔE fusion proteins were able to pull down endogenous nesprin-3α in lysates from MFs in the presence of ATP, with MBP-torsinAΔE consistently pulling down ~threefold more than torsinA (3.0±0.3, n=3, P<0.003, two-way ANOVA) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Binding of MBP-torsinA and MBP-torsinAΔE recombinant proteins to nesprin-3α and GST KASH. (A) MBP, MBP-torsinA or MBP-torsinAΔE fusion proteins (Hewett et al., 2003) (8 μg) were bound to amylase resin (New England Biolabs) and incubated overnight at 4°C with lysates of wild-type MFs (500 μl protein in 1 ml) in RIPA buffer containing 1 mM ATP and 3 mM MgCl2. Beads were washed five times with RIPA buffer and proteins bound to beads resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies to nesprin-3α (top) and MBP (bottom), with relative binding assessed as in Fig. 1. MBP-torsinAΔE consistently pulled down ~threefold more nesprin-3α than did MBP-torsinA (3.0±0.3, n=3, P<0.003, ANOVA). The lower, immunoreactive nesprin-3α band is a degradation product, also seen by Wilhelmsen et al. (Wilhelmsen et al., 2005). (B) GST or GST-KASH fusion protein (10 μg) bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads was incubated with 10 μg of MBP-torsinA or MBP-torsinAΔE in 500 μl PBS containing 1 mM ATP and 3 mM MgCl2 for 1 hour at 4°C. Unbound material was removed by centrifugation and the beads washed five times with 0.1% NP40 buffer followed by an additional wash with PBS. The proteins bound to the beads were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by western blotting with antibodies to MBP and GST.

Association of the KASH domain of nesprin-3 with torsinA

If torsinA associates with nesprin-3 it must do so through its KASH domain, which is the only portion of nesprin-3 located in the lumen of the NE, where torsinA resides. To evaluate whether torsinA binds directly to nesprin-3α KASH sequences, MBP-torsinA and MBP-torsinAΔE recombinant proteins were mixed 1:1 with GST or GST-KASH-3α and bound to glutathione-Sepharose TM4B beads in the presence of ATP. The mouse nesprin-3α KASH domain exhibits a high degree of homology with that of human nesprin-3 (88%) and the two proteins also share a PBD domain in the N-terminal region (supplementary material Fig. S1). Unbound material was removed by centrifugation and washing, and bound proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunostained with antibodies to MBP and GST (Fig. 4B). Direct binding of wild-type and mutant torsinA fusion proteins to GST-KASH-3α was observed, but with no apparent binding differential between mutant and wild-type torsinA under these in vitro conditions.

Nesprin-3α has an alternatively spliced exon 1 variant, nesprin-3β, which retains the KASH domain that determines NE localization but is unable to associate with plectin (Wilhelmsen et al., 2005). Consistent with this, nesprin-3β also binds to torsinA(supplementary material Fig. S4).

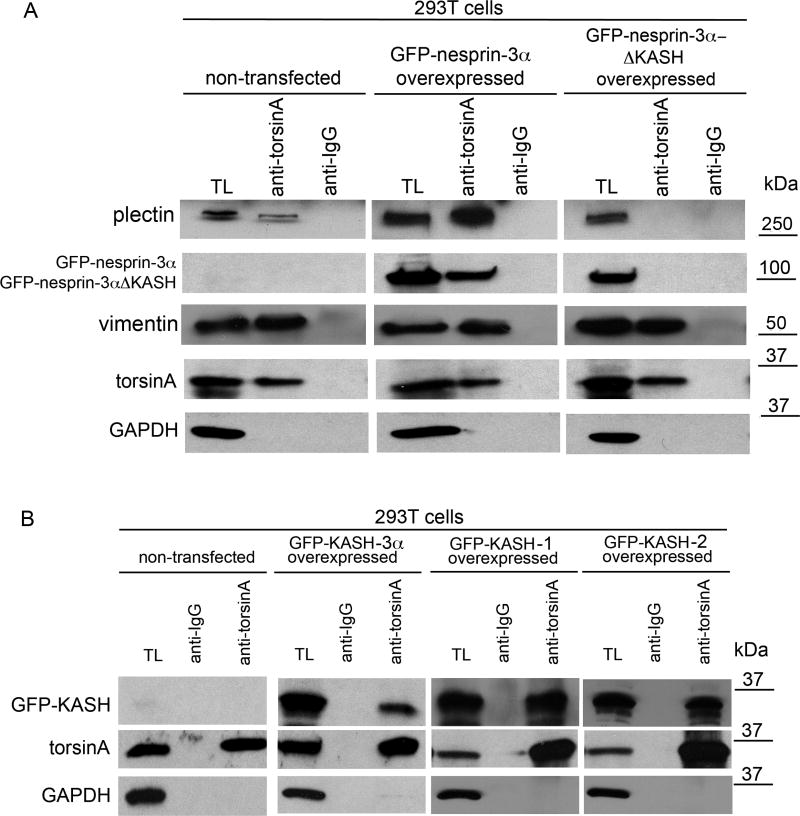

To further evaluate the involvement of the KASH domain in thenesprin-3-torsinA complex, 293T fibroblasts were transfected with expression cassettes for GFP-nesprin-3α or GFP-nesprin-3αΔKASH (Wilhelmsen et al., 2005). SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting of lysates of transfected cells revealed comparable expression levels of both fusion proteins 48 hours post-transfection (data not shown). Immunoprecipitation of torsinA was carried out in cell lysates, and precipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subject to western blotting using antibodies to plectin, GFP, vimentin, torsinA and GAPDH. GFP-nesprin-3α showed the previously observed association with torsinA, but GFP-nesprin-3αΔ KASH did not (Fig. 5A). Similar amounts of torsinA were precipitated with torsinA antibodies from non-transfected cells (10±3%) as from cells transfected with GFP-nesprin-3α (13±5%) or GFP-nesprin-3αΔ KASH (11±5%). By contrast, 2.5-fold more plectin was immunoprecipitated from cells transfected with GFP-nesprin-3α than from non-transfected cells, and no detectable plectin was immunoprecipitated with torsinA from cells expressing GFP-nesprin-3αΔKASH. However, levels of immunoprecipitated vimentin were essentially the same under all three conditions. This might be explained by the association of torsinA with the KASH domains of nesprin-1 and -2 (see below), and by the binding of the latter proteins to actin microfilaments with direct interaction with vimentin (Esue et al., 2006) and cross-links to IFs, such as vimentin, via plakins (Hermann et al., 2007).

Fig. 5.

TorsinA associates with the KASH domain. (A) Human 293T cells were transfected with lentivirus vector encoding expression constructs for GFP-mouse-nesprin-3α or GFP-mouse-nesprin-3αΔ KASH. After 48 hours the cells were lysed and proteins immunoprecipitated with antibodies to torsinA or IgG (no added ATP), resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies to plectin, GFP, vimentin, torsinA and GAPDH. Similar amounts of torsinA were precipitated from non-transfected cells and cells transfected with the GFP-nesprin-3α or GFP-nesprin-3αΔ KASH constructs. By contrast, no detectable plectin was immunoprecipitated with torsinA from cells expressing GFP-nesprin-3αΔ KASH, although some was immunoprecipitated from cells expressing GFP-nesprin-3α. (B) A similar experiment to A except that cells were transfected with expression constructs for GFP-KASH-3α, GFP-KASH-1 or GFP-KASH-2 (i.e. the KASH domains of nesprin-3α, nesprin-1 and nesprin-2, respectively). Immunoprecipitation with torsinA antibodies followed by immunoblotting for GFP revealed an association of torsinA with the KASH domains of all three nesprins. The percentage of each protein immunoprecipitated from lysates by torsinA antibodies is: 11±3% for GFP-KASH-3α, 21±5% for GFP-KASH-1, 12±4% for GFP-KASH-2 (values are mean percentage ± s.e.m., n=3 experiments).

The KASH domains are highly homologous (65%) among nesprins, with nesprin-1 and -2 having an ABD domain and nesprin-3 a PBD domain (Wilhelmsen et al., 2006) (supplementary material Fig. S1). To evaluate the association of torsinA with these different KASH domains, 293T fibroblasts were transfected with expression cassettes for GFP-KASH fusion proteins derived from mouse nesprin-3α and human nesprin-1 and -2. Immunoprecipitation with torsinA antibodies and immunoblotting for GFP revealed an association of torsinA with all three KASH domains (Fig. 5B).

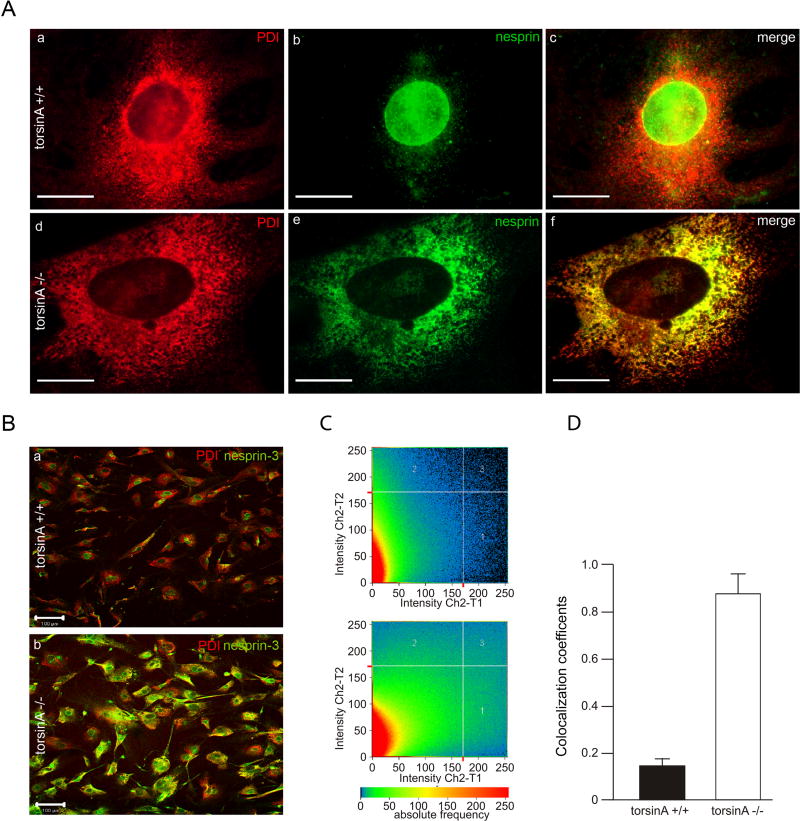

Effect of torsinA status on the distribution of endogenous nesprin-3α

Since torsinA appears to be associated with nesprin-3α in the ONM, the absence of torsinA might affect the cellular distribution of nesprin-3α. In most torsinA+/+ MEFs, nesprin-3α immunoreactivity (green) was primarily concentrated in the perinuclear region, as described for other cells (Wilhelmsen et al., 2005), as judged by co-immunocytochemistry for phosphodisulfide isomerase (PDI; red), a soluble chaperone in the lumen of the ER (Fig. 6Aa–c). By contrast, in most torsinA−/− MEFs, a substantial proportion of the nesprin-3α immunoreactivity appeared to be in the ER, as confirmed by relative co-localization with PDI (Fig. 6Ad–f). The relative proportion of nesprin-3α in the perinuclear region versus the ER proper was quantitated by evaluating co-localization coefficients for ER staining of PDI and nesprin-3α using a confocal microscope (Fig. 6B–D). TorsinA+/+ cells showed a predominantly perinuclear localization of nesprin-3α (co-localization coefficient with PDI of 14±5%, n=3), whereas in torsinA−/− cells nesprin-3α had extensive overlap with the ER (co-localization coefficient of 87±12%, n=3; P<0.0001, two-way ANOVA), indicating that interaction with torsinA is a factor in localizing nesprin-3 in the NE.

Fig. 6.

Differential distribution of nesprin-3 in torsinA+/+ and torsinA−/− MEFs. (A) Double immunolabeling for the ER marker PDI and nesprin-3α in torsinA+/+ and torsinA−/− MEFs. (B) As A, but at lower magnification. (C) The relative proportion of immunoreactive nesprin-3α that was co-localized with the ER marker PDI in torsinA+/+ and torsinA−/− cells was assessed with a confocal microscope using the LSM 5 Pascal program, evaluating the co-localization coefficient for 150 cells of each cell type. (D) The relative number of co-localizing pixels in the red and green channels was evaluated in a value range 0–1 (0, no co-localization; 1, all pixels co-localize) and a significant difference was found between torsinA+/+ and torsinA−/− cells (n=3, P<0.0001, ANOVA). Error bars indicate s.e.m. Scale bars: 10 μm in A; 100 μm in B.

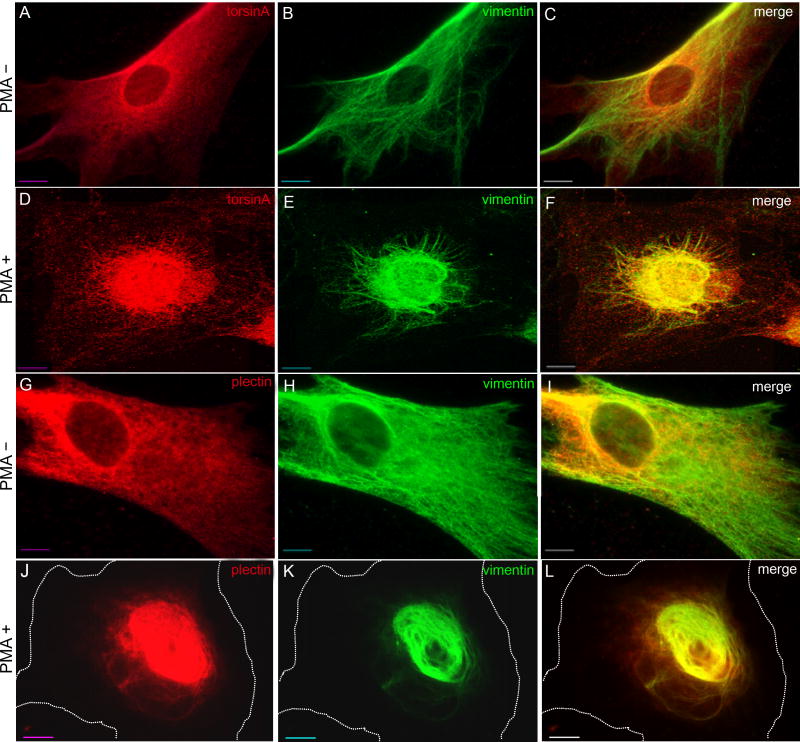

Effect of PMA treatment on the cytoskeletal network and torsinA distribution

Treatment of human fibroblasts with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate(PMA), an activator of protein kinase C (PKC), causes a collapse of vimentin into the perinuclear region (Djabali, 1999). PKC is a serine-threonine kinase that phosphorylates vimentin at multiple sites, leading to partial filament disassembly (Erikssonet al., 2004). Plectin is also phosphorylated by PKC with a consequent weakening, but not elimination, of plectin-vimentin connections (Foisner et al., 1991). We confirmed that treatment of control primary human fibroblasts with PMA led to a concentration of vimentin immunoreactivity in the perinuclear region within30 minutes (Fig. 7E,K), with no concomitant collapse of microfilaments or microtubules (supplementary material Fig. S5), and with rapidrecovery upon removal of PMA and no loss of viability (data not shown). In addition to vimentin, torsinA and plectin also collapsed into the perinuclear region in PMA-treated fibroblasts (Fig. 7D,J). PMA-induced perinuclear vimentin collapse was also observed in torsinA+/+ MEFs, but not in torsinA−/− MEFs, consistent with a role for torsinA in maintaining nesprin-3α in the ONM and with nesprin-3α linking vimentin to the NE (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Co-collapse of torsinA, plectin and vimentin following PMA treatment. Control human fibroblasts were treated with 200 ng/ml PMA (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate) for 30 minutes and the distribution of torsinA and vimentin (A-F), or of plectin and vimentin (G-L), was assessed by immunocytochemistry. The cell perimeter is outlined in J-L. This experiment was repeated three times and representative images are shown. Scale bar: 10 μm.

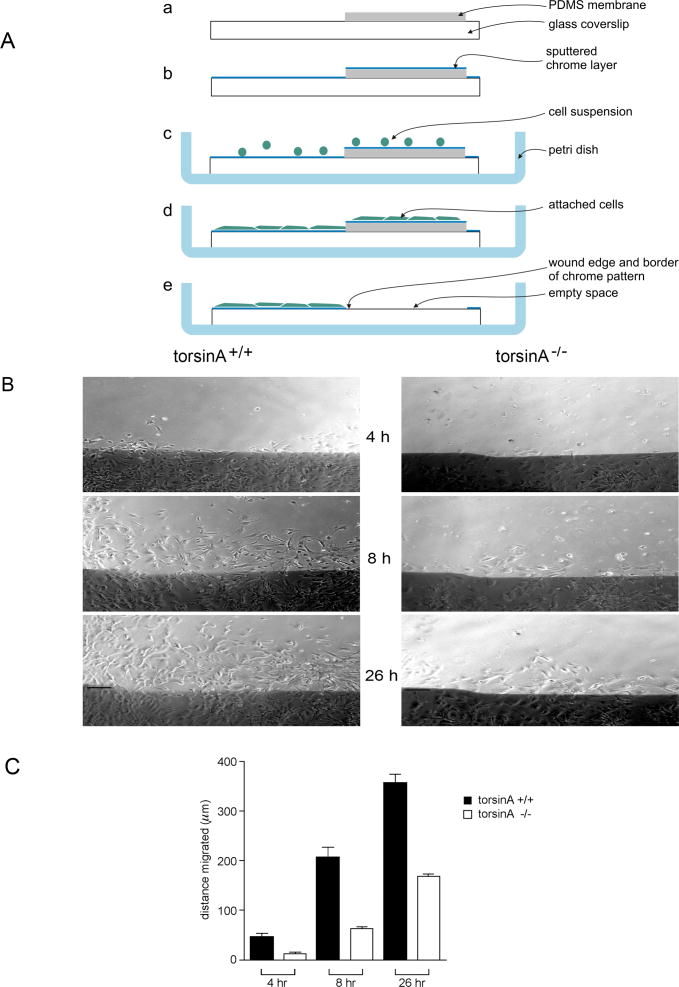

Effects of torsinA status on nuclear structure, cell migration and nuclear polarization

Given the influence of vimentin on nuclear shape (Sarria et al., 1994) and the involvement of vimentin and plectin in cell migration (Eckes et al., 1998; Andra et al., 1998), the question remained as to the possible functions of the complex formed between torsinA, nesprin-3α, plectin and vimentin in fibroblasts (see above). Ultrastructural evaluation of the apposition of the INM and ONM in the NE in torsinA−/− MEFs did not reveal any apparent abnormalities (supplementary material Fig. S6). To evaluate whether this torsinA-nesprin association was involved in cell migration, we carried out a wound-healing assay in which swaths were made in confluent monolayers of MEFs and the rate of migration of the leading edge was evaluated using both a standard assay (Gomes and Gundersen, 2006) and a new method employing microfabricated coverslips. In the latter method, cells are plated on coverslips that are partially covered by a thin polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane co-incident with micropatterned marks, and then covered with a thin layer of chrome (Fig. 8A) that does not affect cell adhesion or movement (Hunter et al., 1995). Cells were allowed to form a confluent monolayer on this surface and then a wound was initiated by removal of the PDMS membrane, made visible microscopically by the absence of chrome in the wound region. A significant delay in the migration of torsinA−/− cells was noted, with only 23±7% of the distance covered by torsinA+/+ cells at 4 hours post-wounding, 31±4% at 8 hours and 47±3% at 26 hours (n=7; P<0.0001at all time points, two-way ANOVA) (Fig. 8B,C).

Fig. 8.

Migration of torsinA+/+ and torsinA−/− MEFs. (A) A microfabrication chamber was designed for wound-healing assays to provide a precise physical reference of the original position of the wound edge during long-term observations. (a) A micropatterned coverslip was partially covered with a thin polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane. (b) A thin layer of chrome was deposited over the entire surface of the coverslip and membrane. (c) The coverslip was placed in a Petri dish and covered with a suspension of cells. (d) The cells were allowed to form a confluent monolayer on the glass and the thin PDMS membrane. (e) The wound was initiated by peeling off the PDMS membrane, which removes all cells except those on the chrome layer. (B) Confluent monolayers were incubated in serum-free medium for 48 hours, then a wound was made in the monolayer and 5% serum was added (Gomes and Gundersen, 2006). Marked regions in the wound were photographed under phase-contrast microscopy, sequentially at intervals up to 26 hours post-wounding and the migration of cells into the cleared space was monitored at different time points. Digital images were taken at 10× magnification and evaluated using MetaVuE software with Microsoft Excel. Photographs of fibroblast monolayers were taken under phase-contrast microscopy 4, 8 and 26 hours after wounding (a representative region is shown). Scale bar: 150 μm. (C) The migration of the leading edge of cells was measured (in μm) from fixed points on the wound edge. Values represent mean ± s.e.m. (error bars) of measurements in six regions per time point for each genotype from seven experiments. Differences between torsinA+/+ and torsinA−/− cells were significant at all time points (P<0.0001, ANOVA).

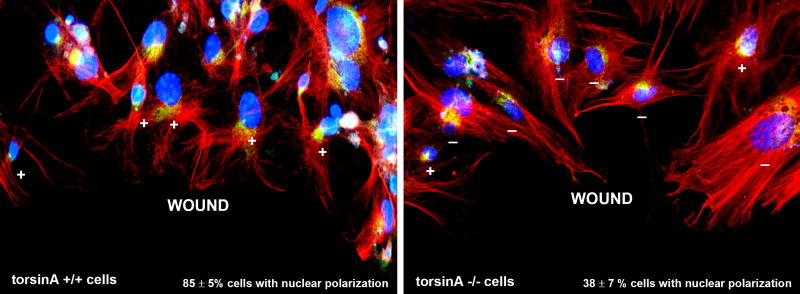

As an initial step in cell migration, we also evaluated polarization of the nucleus relative to the wound edge by immunocytochemistry for pericentrin, as to determine the position of the centrosome relative to the nucleus (DAPI staining), as described (Gomes et al., 2005). At 3 hours post-wounding, there was a significant difference between the extent of nuclear polarization, with85±5% of torsinA+/+ cells and only 38±7% of torsinA−/− cells (n=3; P<0.01, two-way ANOVA) showing positioning of the nucleus behind the centrosome relative to the wound edge(Fig. 9). Together, these findings suggest that torsinA is not crucial to the structure of the NE per se in fibroblasts, but does affect the positioning of the nuclei within migrating fibroblasts and the rate of movement of these cells.

Fig. 9.

Nuclear polarization in migrating torsinA+/+ and torsinA−/−MEFs. To evaluate nuclear polarization, confluent monolayers of MEFs were serum-starved for 24 hours, then a wound was made through the monolayer and cells were stimulated with 2 μM lysophosphatidic acid (LPA; Sigma-Aldrich) (Gomes and Gundersen, 2006). Three hours later, the cells were fixed and immunostained for pericentrin to label the centrosome (green) and for β-tubulin to label microtubules (red), with DAPI staining (blue) for nuclei. The nucleus was scored as polarized (+) when the centrosome was localized between the nucleus and the leading wound edge and as non-polarized (-) in any other location. Representative images are shown for torsinA+/+ (left) and torsinA−/− (right) cells along the wound edge. One hundred cells of each type were evaluated for orientation of the centrosome between the nucleus and the leading edge in each of three experiments using two different MEF preparations of each type. TorsinA+/+ cells showed 85±5% nuclei in the polarized location, whereas torsinA−/− cells showed only 38±7% in the polarized position at this time point (values are mean percentage ± s.e.m., n=3 experiments, P<0.001). Magnification: 20×.

Discussion

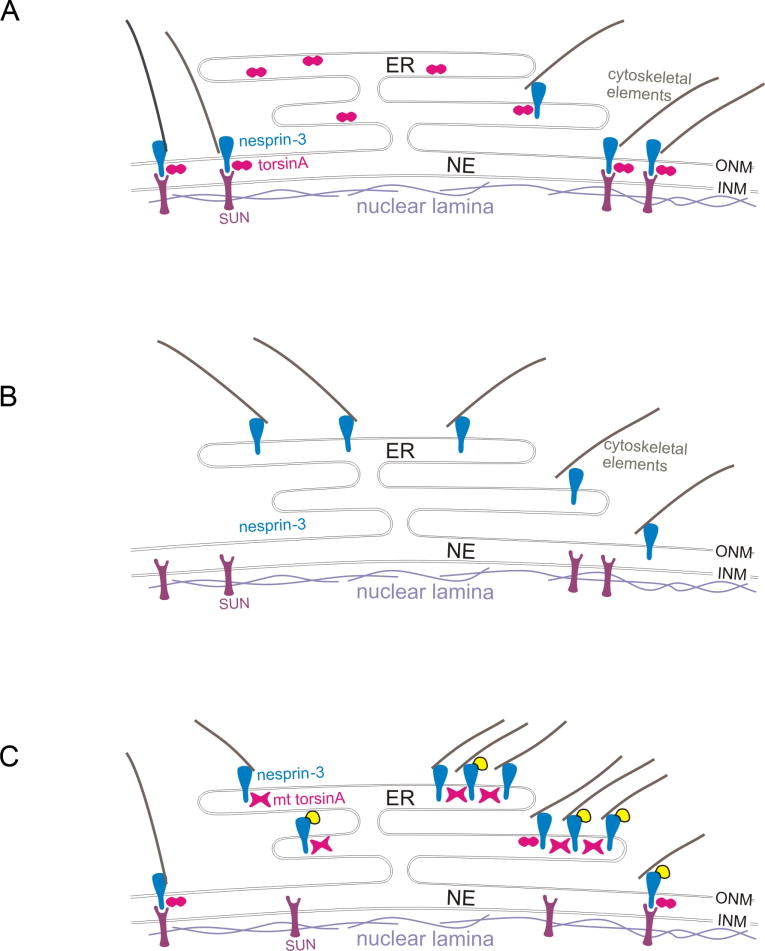

This study demonstrates an association between torsinA in the lumen of the NE and the transmembrane protein nesprin-3 in the ONM of the NE, which in turn links to plectin (Wilhelmsen et al., 2005) and vimentin (Sonnenberg and Liem, 2007) in the cytoplasm. Using recombinant proteins, this association appears to involve a direct interaction between the KASH domain of nesprin-3 and the C-terminal region of torsinA. TorsinA also binds to the KASH domains of nesprin-1 and -2, which interact with cytoplasmic actin (Crisp et al., 2006; Starr and Fischer, 2005) (see Fig. 10A). TorsinA appears to play a role in the localization of nesprin-3 because in fibroblasts lacking torsinA, nesprin-3α is concentrated in the ER (Fig. 10B, diagram), whereas in wild-type cells it is localized predominantly in the NE region. Furthermore, the collapse of vimentin into the perinuclear region in response to PKC activation was abrogated in torsinA-null cells, consistent with vimentin being normally anchored to the NE by nesprin-3/plectin. The accumulation of nesprin-3α in the ER was also observed in a previous study upon overexpression of GFP-nesprin-3αΔ PPPT (nesprin-3α deleted for the SUN-binding domain) (Ketema et al., 2007), consistent with the interaction of nesprin-3α with both torsinA and SUN proteins. The dystonia-associated inactive mutant form of torsinA, torsinAΔE, was found under some conditions to bind more tightly to nesprin-3 than did torsinA. Thus, when YFP-nesprin-3 was overexpressed in control fibroblasts, it showed a predominantly NE localization, whereas in fibroblasts from DYT1 subjects it resulted in YFP-nesprin-3 globular structures located predominantly in the ER compartment that were enriched in torsinA, vimentin and actin (Fig. 10C). This torsinA-nesprin-cytoskeletal association does not appear to be involved in maintaining the structure of the NE in fibroblasts per se, but torsinA-null fibroblasts showed a reduced ability to position nuclei behind the centrosome in relation to the leading edge of cell migration in a wound assay, and migration itself was delayed in torsinA-null as compared with wild-type fibroblasts.

Fig. 10.

Theoretical consequences of torsinA status for nesprin-SUN interactions. Nesprins span the outer nuclear membrane (ONM) and interact with cytoskeletal elements in the cytoplasm and with inner nuclear membrane (INM) proteins, such as SUNs, in the lumen of the nuclear envelope (NE). TorsinA is hypothesized to act as an AAA+ protein in the disassembly/reassembly of these nesprin-SUN interactions, for example, during movement of the nucleus in cell migration. (A) In wild-type cells, nesprins and associated cytoskeletal elements are localized to the ONM by interactions with INM proteins, such as SUNs, and this interaction (at least for nesprin-3) is modulated by torsinA (depicted as an oligomer in cross-section, two circles). (B) In torsinA-null cells, nesprin-3 and linked cytoskeletal elements are located predominantly in association with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (see Fig. 6), as the association of nesprins with INM proteins is predicted to be compromised. (C) Cells from DYT1 subjects express both torsinA and torsinAΔE, with the mutant (mt) torsinA hypothesized to form inactive oligomers with torsinA (depicted as X-shaped structures). When YFP-nesprin-3 is overexpressed in DYT1 cells, torsinA oligomers containing torsinAΔE, which binds more tightly than torsinA to nesprins, reduce the interaction of YFP-nesprin-3 with INM proteins, such that YFP-nesprin-3 accumulates in the ER, where, together with torsinA/torsinAΔE and associated cytoskeletal elements, it forms globular structures (see Fig. 2).

Relationship between torsinA and the cytoskeleton

TorsinA has been hypothesized to be involved in modulating connections between transmembrane proteins in the INM, such as LAP1 and SUNs, and those in the ONM, such as nesprins, which in turn connect with cytoskeletal elements (Gerace, 2004; Worman and Gundersen, 2006). The present study supports a complex of torsinA-nesprin-3-plectin-vimentin in fibroblasts, with torsinA also associating with the KASH domains of nesprin-1 and -2 and hence presumably with complexes involving actin microfilaments. As nesprin-3 is primarily localized in the NE (Wilhelmsen et al., 2005), and torsinA is found in both the NE and ER, torsinA must have other partners in the ER. Since both SUNs (Starr and Fischer, 2005) and torsinA (this study) bind to the KASH domain of nesprins, it is hypothesized that, as an AAA+ protein, torsinA might confer a dynamic aspect to the interaction between nesprin and SUN proteins in the lumen of the NE.

Vimentin dynamics

Vimentin, a member of the large family of IF proteins, is especially abundant in fibroblasts and extends out from the nucleus to the plasma membrane in a dense filamentous network interlinked to actin filaments and microtubules through plakins (Wiche, 1998). Vimentin-knockout mice do not have an obvious phenotype(Colucci-Guyon et al., 1999), but their fibroblasts have impaired mechanical stability and contractility with poorly organized actin filaments and reduced directional migration (Eckes et al., 1998). A similar cellular phenotype was observed in plectin-knockout fibroblasts, again implicating an effect on actin dynamics (Andra et al., 1998). Vimentin is also involved in initial neurite outgrowth from neurons (Dubey et al., 2004) and in retrograde signaling following nerve injury and regeneration (Perlson et al., 2005), with vimentin-null mice having abnormal brain morphology(Colucci-Guyon et al., 1999). Thus, changes in IF dynamics caused by loss of, or mutations in, torsinA could affect a wide range of neuronal properties, including process extension, response to injury and embryonic migration.

Involvement of torsinA in nuclear dynamics

A role for torsinA in nuclear dynamics was initially indicated by a nematode homolog, OOC-5, which has a perinuclear/ER localization and is involved in rotation of the nucleus during early embryogenesis (Basham and Rose, 2001). Other studies indicate that an E171Q mutation in the Walker B ATP-binding domain of torsinA, which blocks ATPase activity, results in accumulation of torsinA near the NE, presumably owing to prolonged interaction with substrate(s) there and abnormalities in the structure of the NE (Naismith et al., 2004; Goodchild et al., 2005). High-level expression of torsinAΔE or torsinA produces whorled membrane inclusions that appear to ‘spin off’ the NE/ER (Bragg et al., 2004; Gonzalez-Alegre and Paulson, 2004; Grundmann et al., 2007). These observations are consistent with torsinA regulating the interaction between the lumenal domains of transmembrane proteins that span the INM and ONM and are involved in NE structure.

The interaction of NE proteins with cytoskeletal elements contributes to intracellular movement of the nucleus during cell migration(Gomes et al., 2005; Wilhelmsen et al., 2006). For example, SUN1 (UNC84A) is involved in linkage between the centrosome and the NE (Malone et al., 2003) and other SUN proteins interact with nesprins, which link to actin microfilaments and IFs (Crispet al., 2006; Ketema et al., 2007). Several components might underlie the reduced rate of cell migration in torsinA−/− MEFs, including disorientation of vimentin or actin microfilaments and/or a reduced rate of nuclear polarization. Polarization of the nucleus during cell migration is thought to be dependent primarily on actin microfilaments (Gomes et al., 2005). Nuclear polarization in torsinA−/− cells might be compromised by localization of nesprin-3 in the ER, with associated plakin-mediated interconnections between IFs and actin microfilaments (Chang and Goldman, 2004). The potential mislocalization of nesprin-1 and -2 in cells lacking torsinA was not investigated in this study, so it is not known whether the decrease in cell migration observed in torsinA−/− MEFs involves a disturbance in nesprin-1 and -2 connections to actin microfilaments (Crisp et al., 2006).

Interestingly, BPAG1 (dystonin), which is responsible for dystonic movements in a mouse model termed dystonia musculorum deformans (dt/dt) is, like plectin, a member of the plakin family of proteins that link together elements of the cytoskeleton (Sonnenberg and Liem, 2007). Recent studies show that an isozyme of BPAG1 is associated with the NE and affected neurons in BPAG1-deficient mice have neurofilament aggregates and improper placement of nuclei (Young et al., 2006). Thus, alterations in nuclear dynamics appear to be a common feature in neurons of dt/dt mice and torsinA-null or torsinAΔE homozygous knock-in mice (Goodchild et al., 2005), as well as in torsinA-null MEFs.

Implications for DYT1 dystonia

Although dystonia is primarily a disease of motor control, imaging studies indicate subtle alterations in microstructure and metabolism in certain regions of the brain in DYT1 patients (Asanuma et al., 2005; Carbon et al., 2008). These findings are consistent with torsinAΔE interfering with development and communication in select neuronal populations. Our findings that torsinAΔE, thought to be an inactive form of torsinA, appears to associate more strongly with nesprin-3 than does torsinA, and that loss of torsinA activity reduces nuclear polarization and cell migration, are consistent with there being abnormalities in brain development in DYT1 patients. Presumably, only a subset of neurons in the human brain, possibly those with normally high levels of torsinA and therefore more dependent on it than other cells, is compromised by low levels of torsinA function. TorsinA dependency is thought to be greatest during the developmental period when its expression is highest in the brain (Xiao et al., 2004; Vasudevan et al., 2006; Siegert et al., 2005) and neuronal migration is ongoing. Results from in situ hybridization with probes for torsinA andnesprin-3 genes in adult mice suggest extensive overlap of expression in striatum, cerebral cortex, substantia nigra and cerebellum (Allen Brain Atlas, Mouse Brain Project, Allen Institute for Brain Research, http://www.brain-map.org/welcome.do). These same brain regions have been implicated in the pathogenesis of dystonia (Eidelberg, 1998; Yokoi et al., 2008; Berardelli et al., 1998; Breakefield et al., 2008).

Conclusions

This study supports a role for torsinA in nuclear dynamics via its association with nesprins and the cytoskeleton. As an AAA+protein, torsinA might confer a dynamic property to the ONM and INM protein interactions involved in the movement of nuclei within migrating cells. In DYT1 patients, mutant torsinA might compromise these interactions in some neurons, leading to delayed migration during development and thus reduced numbers of neurons in specific regions of the brain. This would predict a subtly altered neuronal circuitry in the brains of DYT1 subjects that contributes to an abnormal neurotransmission underlying the dystonic symptoms.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Cells were primary human skin fibroblasts as control (HF19 andHF27, Breakefield Laboratory) and from DYT1 subjects (FFF13111983, from M. Filocamo, L’Instituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa, Italy; HF48 and HF49, Breakefield Laboratory) and human embryonic kidney fibroblast line 293T (from D. Baltimore, MIT, Cambridge, MA). Primary MEFs were generated from individual E13–14 embryos, genotyped (Dang et al., 2005), treated with Plasmocin (InvivoGen) to avoid mycoplasma contamination and used within the first four passages. MFs were generated from mouse pups (Andra et al., 1998). Cells were maintained in culture as described (Hewett et al., 2007).

Vectors and constructs

Lentivirus vectors were derived from self-inactivating lentivirus (CS-CGW) (Sena-Esteves et al., 2004), in which the cDNA of interest under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate early promoter is followed by an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) and a reporter cDNA (Hewett et al., 2006). Fusion constructs use a modified version lacking the IRES.

cDNAs for human torsinA and torsinAΔE (Ozelius et al., 1997) were cloned downstream of the CMV promoter yielding CS-CGW-TorAand CS-CGW-TorAΔE, respectively (Hewett et al., 2006). A C-terminal-deleted version of torsinA containing amino acids 1-311 (torsinAΔ312–332) was amplified from the cDNA and inserted into the CFP-containing PCS-CGW backbone.

To generate YFP-human-nesprin-3, human nesprin-3 cDNA was amplified from single-stranded DNA that had been reverse-transcribed from human fibroblast (HF19) RNA. PCR was performed with Phusion Hot Start (Finnzymes) using primers upstream of the start codon(5′-GCCCCTGCAGGTGCCATGACTCAG-3′) and downstream of the stopcodon (5′-CTGATATGGATGCAGCTCTGCAGT-3′). Nested forward (5′-ATGACTCAGCAGCCCCAGGACGAC-3′) and reverse (5′-TTAGGTGGGTGGTGGGCCATTGTA-3′) primers were used to amplify just the cDNA. YFP sequences were PCR-amplified from pEYFP-C1 (Clontech) using primers containing a 5′ NheI site (5′-AATGCTAGCGGTCGCCACCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAG-3′) and HindIII site (5′-CAGAAGCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCC-3′).

Vectors were produced by co-transfection of 293T cells with the lentivirus packaging plasmid (pCMVR8.91), envelope-coding plasmid (pVSVG) and vector construct, yielding typical titers of 1×108 transducing units/ml (Sena-Esteves et al., 2004).

For GST-KASH, the KASH domain (amino acids 910–975) of nesprin-3α was amplified by PCR using Phusion Hot Start and primers containing5′ BamHI (5′-GGGATCCATCCTCCAAAAATCGGAT-3′) and 3′ XhoI (5′-CATAAGCTTATGACTCAGCAGCCCCAGGAC-3) sites. After digestion with BamHI and XhoI, the sequence was inserted into the PGEX-4T1 vector in-frame with GST. GFP-KASH derived from nesprin-1 and -2 were kindly provided by BrianBurke, University of Florida.

Antibodies

Antibodies included mouse monoclonals specific to torsinA [D-M2A8 and D-M10 (Hewett et al., 2003) and MBP (New England Biolabs) and rabbit polyclonal antibodies to torsinA and torsinB [TAB1(Hewett et al., 2003)] and specific to torsinB [TB2 (Hewett et al., 2004)], human plectin (BD Biosciences or Epitomics), mouse nesprin-3α (Wilhelmsen et al., 2005), protein disulfide isomerase (PDI; SPA-891, Stressgen), pericentrin (Covance), rabbit GFP (Molecular Probes), goat GFP (Abcam), α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich), vimentin (Lab Vision), GAPDH (MAB374, Chemicon), pericentrin (PRB-432C, Covance), GST (Abgent), β-actin (clone AC-15, Sigma) and Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin (Molecular Probes).

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was carried out as described (Hewett et al., 2006). DNA was stained with 0.1% 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole(DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich). Antibody dilutions were as follows: D-M2A8 (1:100), α-tubulin (1:1000), GFP (1:2000), human plectin (BD Biosciences) (1:50), nesprin-3α (1:1000), PDI (1:200), pericentrin (1:1000), vimentin (1:800), β-actin (1:500) and Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin (1:1000) was used to stain actin.

Immunoprecipitation, pull-downs and western blots

For immunoprecipitation, total cell lysates (~1×106 cells) were resuspended in 1 ml RIPA lysis buffer [150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 1% NP40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS (Hewett et al., 2006)]. The lysates were immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C using specific antibodies: 10 μl D-M2A8 and D-MG10 (1:1) or 10 μl goat anti-mouse IgG (Abcam) per 500 μglysate in 1 ml with 3 mg/ml Protein A-agarose (Roche), as described (Hewett et al., 2003). For immunoprecipitation of overexpressed protein in 293T cells, we added to the lysis buffer 1 mM ATP, or 1 mM non-hydrolysable ATP, or 1 mM EDTA (all Sigma). Proteins were resolved by electrophoresis in 10% SDS-PAGE gels, stained for protein and immunoblotted as described (Hewett et al., 2006). Antibody dilutions for western blots were as follows: TAB1 (1:200), D-M2A8 (1:100), nesprin-3α (1:1000), MBP (1:10,000), plectin (Epitomics) (1:1000), vimentin (1:2000), rabbit GFP (1:2000), goat GFP (1:2000), GAPDH (1:500) and GST (1:3000).

Purified recombinant MBP-torsinA and MBP-torsinAΔE expression plasmids (constructs started at amino acid 51 of torsinA) and the control MBP expression plasmid were constructed in pmal-C1-torA (Hewett et al., 2003) and used to transform Escherichia coli BL21 (New England Biolabs). Protein expression and purification were carried out as described (Hewett et al., 2003), with the addition of 1 mM ATP and 3 mM MgCl2 to the elution buffer. For MBP pull-down from the MF lysate, we also added 1 mM PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich). Purified recombinant GST-KASH from the nesprin-3α expression plasmid (derived from pGEX-4T1, Amersham Biosciences) and control GST protein from the original expression plasmid were used to transform E. coli BL21 and protein expression and purification were carried out as described in the pGEX manual. For GST or GST-KASH pull-down, 10 μg fusion protein bound to glutathione-Sepharose TM4B beads (Amersham Biosciences) was incubated with 10 μg eluted MBP-torsinA or MBP-torsinAΔE recombinant protein in 500 μl PBS containing 1 mM ATP and 3 mM MgCl2 for 1 hour at 4°C.

Beads were collected by centrifugation (1095 g) and washed five times with 0.1% NP40 buffer [0.1% NP40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0)]. After an additional wash with PBS, bound proteins were eluted from the beads by resuspension in SDS-PAGE loading buffer and resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting using standard methods.

The percentage of proteins immunoprecipitated from lysates was determined by scanning the blots using a Perfection 2480/2580 scanner (Epson America Inc., Long Beach, CA) and quantifying band intensity using Quantity One 4.6.1 software (Bio-Rad).

Wound assay in culture

MEFs were plated on coverslips at 1×105 cells/well in 12-wellplates in normal growth medium. Cell migration was assessed using the method of Eckes et al. (Eckes et al., 1998) or with a novel microfabrication device (see Fig. 8); the methods gave equivalent results. For the latter, a glass coverslip (Fisher Scientific) was partially covered by a 200- to 300-μm rectangular polydimethylsiloxane membrane (PDMS, Dow Corning). The membrane had one edge aligned with micropatterned marks to identify positions along the edge. The micropatterned membranes are manufactured by casting small amounts of PDMS between a micropatterned mold and a flat Mylar film. The mold was produced using standard microfabrication techniques and involves photopatterning a 200-μm layer of expoyphotoresist (SU8, MicroChem) onto a silicon wafer through a photolithography mask (Fineline Imaging). After the PDMS membrane was reversibly bonded to the glass surface by hydrophobic interaction, a thin (50 A) layer of chrome was deposited on the glass using a sputtering machine (Kurt J. Lesker Sputtering System). The chrome layer coated both the glass and the PDMS, creating a pattern on the glass complementary to the PDMS membrane.

Confocal microscopy

A Carl Zeiss LSM 5 Pascal laser-scanning confocal microscope was used. Images were acquired using a 10×, 40× or 63× numerical aperture 1.4 PlanApo differential interference contrast (DIC) objective on an inverted microscope (Axiovert 200M, Zeiss) equipped with an LSM 510META scan head (Zeiss). Argon ion (488 nm), HeNe(543 nm) and HeNe (633 nm) lasers were used for excitation. Green, red and blue fluorescence emissions were detected through BP 505–530, 560–615 and 650 filters, respectively. The different fluorochromes were scanned sequentially using the multitracking function to avoid any bleed through among these fluorescent dyes. Brightfield images were obtained using the argon 488-nm laser. The resolution was 2048, 8 bit. We also used an OlympusFluoView 1000 confocal microscope with independent photostimulation and imaging channels, with the same lasers as above as well as a 361-nm UV laser, including a tunable two-photon source for reduced photodynamic damage. This microscope also has DIC optics and a photomultiplier collector for transmitted light imaging.

Electron microscopy

MEFs were grown as confluent monolayers on plastic coverslips, fixed in situ in 2% glutaraldehyde in 30 mM HEPES (pH 7.3), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MgCl2. Coverslips were then washed in the same buffer without glutaraldehyde, incubated for 30minutes in 0.5% KMnO4 in 150 mM NaCl, then dehydrated, embedded in araldite resin, sectioned and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate according to standard procedures. Sections were viewed in a JEOL transmission electron microscope operating at 100 kV and photographed with a charge-coupled device camera system (Advanced Microscopy Techniques).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prisma software (version3.0). Results are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Multiple comparison analysis of variance between the groups was performed by a two-way ANOVA test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Phyllis Hanson for advice and help with electron microscopy analysis; Brian Burke for advice and for the GFP-KASH constructs for nesprin-1 and -2; John Heuser for electron microscopy; Igor Bagayev, Thomas Wurdinger, Johan Skog and Bakhos Tannous for help with image analysis; D. Cristopher Bragg for advice; Miguel Sena-Esteves for vector generation; Pradeep Bhide and Deirdre McCarthy for help with timed pregnancies and for advice; Ashira Gendelman, Lisa Pike and John Kuster for data analysis; DavidCorey for his generosity in allowing us to use his confocal microscope; and Suzanne McDavitt for skilled editorial assistance. Funding was provided by the Bachmann-Strauss Foundation, the Jack Fasciana Fund for Support of Dystonia Research and NINDS NS037409.

Footnotes

References

- Andra K, Nikolic B, Stocher M, Drenckhahn D, Wiche G. Not just scaffolding: plectin regulates actin dynamics in cultured cells. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3442–3451. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andra K, Kornacker I, Jorgl A, Zorer M, Spazierer D, Fuchs P, Fischer I, Wiche G. Plectin-isoform-specific rescue of hemidesmosomal defects in plectin (−/−) keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:189–197. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma K, Carbon-Correll M, Eidelberg D. Neuroimaging in human dystonia. J Med Invest. 2005;52:272–279. doi: 10.2152/jmi.52.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basham SE, Rose LS. The Caenorhabditis elegans polarity gene ooc-5 encodes a Torsin-related protein of the AAA ATPase superfamily. Development. 2001;128:4645–4656. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.22.4645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardelli A, Rothwell JC, Hallett M, Thompson PD, Manfredi M, Marsden CD. The pathophysiology of primary dystonia. Brain. 1998;121:1195–1212. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.7.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragg DC, Camp SM, Kaufman CA, Wilbur JD, Boston H, Schuback DE, Hanson PI, Sena-Esteves M, Breakefield XO. Perinuclear biogenesis of mutant torsin-A inclusions in cultured cells infected with tetracycline-regulated herpes simplex virus type 1 amplicon vectors. Neuroscience. 2004;125:651–661. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breakefield XO, Blood AJ, Li Y, Hallett M, Hanson PI, Standaert DG. The pathophysiologic basis of the dystonias. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:222–234. doi: 10.1038/nrn2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callan AC, Bunning S, Jones OT, High S, Swanton E. Biosynthesis of the dystonia-associated AAA+ ATPase torsinA at the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem J. 2007;401:607–612. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon M, Kingsley PB, Tang C, Bressman S, Eidelberg D. Microstructural white matter changes in primary torsion dystonia. Mov Disord. 2008;23:234–239. doi: 10.1002/mds.21806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Goldman RD. Intermediate filaments mediate cytoskeletal crosstalk. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:601–613. doi: 10.1038/nrm1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarimon J, Asgeirsson H, Singleton A, Jakobsson F, Hjaltason H, Hardy J, Sveinbjornsdottir S. Torsin A haplotype predisposes to idiopathic dystonia. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:765–767. doi: 10.1002/ana.20485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci-Guyon E, Gimenez YRM, Maurice T, Babinet C, Privat A. Cerebellar defect and impaired motor coordination in mice lacking vimentin. Glia. 1999;25:33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp M, Liu Q, Roux K, Rattner JB, Shanahan C, Burke B, Stahl PD, Hodzic D. Coupling of the nucleus and cytoplasm: role of the LINC complex. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:41–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang MT, Yokoi F, McNaught KS, Jengelley TA, Jackson T, Li J, Li Y. Generation and characterization of Dyt1 DeltaGAG knock-in mouse as a model for early-onset dystonia. Exp Neurol. 2005;196:452–463. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang MT, Yokoi F, Pence MA, Li Y. Motor deficits and hyperactivity in Dyt1 knockdown mice. Neurosci Res. 2006;56:470–474. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djabali K. Cytoskeletal proteins connecting intermediate filaments to cytoplasmic and nuclear periphery. Histol Histopathol. 1999;14:501–509. doi: 10.14670/HH-14.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey M, Hoda S, Chan WK, Pimenta A, Ortiz DD, Shea TB. Reexpression of vimentin in differentiated neuroblastoma cells enhances elongation of axonal neurites. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:245–249. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckes B, Dogic D, Colucci-Guyon E, Wang N, Maniotis A, Ingber D, Merckling A, Langa F, Aumailley M, Delouvee A, et al. Impaired mechanical stability, migration and contractile capacity in vimentin-deficient fibroblasts. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:245–249. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.13.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eidelberg D. Abnormal brain networks in DYT1 dystonia. Adv Neurol. 1998;78:127–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson JE, He T, Trejo-Skalli AV, Harmala-Brasken AS, Hellman J, Chou YH, Goldman RD. Specific in vivo phosphorylation sites determine the assembly dynamics of vimentin intermediate filaments. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:919–932. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esue O, Carson AA, Tseng Y, Wirtz D. A direct interaction between actin and vimentin filaments mediated by the tail domain of vimentin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30393–30399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605452200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foisner R, Traub P, Wiche G. Protein kinase A- and protein kinase C-regulated interaction of plectin with lamin B and vimentin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3812–3816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerace L. TorsinA and torsion dystonia: unraveling the architecture of the nuclear envelope. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8839–8840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402441101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes ER, Gundersen GG. Real-time centrosome reorientation during fibroblast migration. Methods Enzymol. 2006;406:579–592. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)06045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes ER, Jani S, Gundersen GG. Nuclear movement regulated by Cdc42, MRCK, myosin, and actin flow establishes MTOC polarization in migrating cells. Cell. 2005;121:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Agosti P, Paulson HL. Aberrant cellular behavior of mutant torsinA implicates nuclear envelope dysfunction in DYT1 dystonia. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2593–2601. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4461-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild RE, Dauer WT. The AAA+ protein torsinA interacts with a conserved domain present in LAP1 and a novel ER protein. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:855–862. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild RE, Kim CE, Dauer WT. Loss of the dystonia-associated protein torsinA selectively disrupts the neuronal nuclear envelope. Neuron. 2005;48:923–932. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann K, Reischmann B, Vanhoutte G, Hubener J, Teismann P, Hauser TK, Bonin M, Wilbertz J, Horn S, Nguyen HP, et al. Overexpression of human wildtype torsinA and human DeltaGAG torsinA in a transgenic mouse model causes phenotypic abnormalities. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;27:190–206. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson PI, Whiteheart SW. AAA+ proteins: have engine, will work. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann H, Bar H, Kreplak L, Strelkov SV, Aebi U. Intermediate filaments: from cell architecture to nanomechanics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:562–573. doi: 10.1038/nrm2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett J, Ziefer P, Bergeron D, Naismith T, Boston H, Slater D, Wilbur J, Schuback D, Kamm C, Smith N, et al. TorsinA in PC12 cells: localization in the endoplasmic reticulum and response to stress. J Neurosci Res. 2003;72:158–168. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett JW, Kamm C, Boston H, Beauchamp R, Naismith T, Ozelius L, Hanson PI, Breakefield XO, Ramesh V. TorsinB-perinuclear location and association with torsinA. J Neurochem. 2004;89:1186–1194. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett JW, Zeng J, Niland BP, Bragg DC, Breakefield XO. Dystonia-causing mutant torsinA inhibits cell adhesion and neurite extension through interference with cytoskeletal dynamics. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22:98–111. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett JW, Tannous B, Niland BP, Nery FC, Breakefield XO. Mutant torsinA interferes with protein processing through the secretory pathway in DYT1 dystonia cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7271–7276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701185104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett JW, Nery FC, Niland B, Ge P, Tan P, Hadwiger P, Tannous BA, Sah DW, Breakefield XO. siRNA knock-down of mutant torsinA restores processing through secretory pathway in DYT1 dystonia cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1436–1445. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter A, Archer CW, Walker PS, Blunn GW. Attachment and proliferation of osteoblasts and fibroblasts on biomaterials for orthopaedic use. Biomaterials. 1995;16:298–295. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)93256-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamm C, Boston H, Hewett J, Wilbur J, Corey DP, Hanson PI, Ramesh V, Breakefield XO. The early onset dystonia protein torsinA interacts with kinesin light chain 1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19882–19892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamm C, Asmus F, Muller J, Mayer P, Sharma M, Muller U, Bekert S, Ehling R, Illig T, Wichmann H, et al. Strong genetic evidence for association of TOR1A/TOR1B with idiopathic dystonia. Neurology. 2006;67:1857–1859. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000244423.63406.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamm C, Ozelius LJ, Breakefield XO. TorsinA and DYT1 early onset dystonia. Funct Neurol. 2008:61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ketema M, Wilhelmsen K, Kuikman I, Janssen H, Hodzic D, Sonnenberg A. Requirements for the localization of nesprin-3 at the nuclear envelope and its interaction with plectin. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3384–3394. doi: 10.1242/jcs.014191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kock N, Naismith TV, Boston HE, Ozelius LJ, Corey DP, Breakefield XO, Hanson PI. Effects of genetic variations in the dystonia protein torsinA: identification of polymorphism at residue 216 as protein modifier. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1355–1364. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kustedjo K, Bracey MH, Cravatt BF. TorsinA and its torsion dystonia-associated mutant forms are lumenal glycoproteins that exhibit distinct subcellular localizations. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:680–685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910025199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Zolkiewska A, Zolkiewski M. Characterization of human torsinA and its dystonia-associated mutant form. Biochem J. 2003;374:117–122. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas A, Flanagan JM, Tamura T, Baumeister W. Self-compartmentalizing proteases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:399–404. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maison C, Pyrpasopoulou A, Theodoropoulos PA, Georgatos SD. The inner nuclear membrane protein LAP1 forms a native complex with B-type lamins and partitions with spindle-associated mitotic vesicles. EMBO J. 1997;16:4839–4850. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone CJ, Misner L, Le Bot N, Tsai MC, Campbell JM, Ahringer J, White JG. The C. elegans hook protein, ZYG-12, mediates the essential attachment between the centrosome and nucleus. Cell. 2003;115:825–836. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00985-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaught KS, Kapustin A, Jackson T, Jengelley TA, Jnobaptiste R, Shashidharan P, Perl DP, Pasik P, Olanow CW. Brainstem pathology in DYT1 primary torsion dystonia. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:540–547. doi: 10.1002/ana.20225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naismith TV, Heuser JE, Breakefield XO, Hanson PI. TorsinA in the nuclear envelope. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7612–7617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308760101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuwald AF, Aravind L, Spouge JL, Koonin EV. AAA+: A class of chaperone-like ATPases associated with the assembly, operation, and disassembly of protein complexes. Genome Res. 1999;9:27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozelius LJ, Hewett JW, Page CE, Bressman SB, Kramer PL, Shalish C, de Leon D, Brin MF, Raymond D, Corey DP, et al. The early-onset torsion dystonia gene (DYT1) encodes an ATP-binding protein. Nat Genet. 1997;17:40–48. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlson E, Hanz S, Ben-Yaakov K, Segal-Ruder Y, Seger R, Fainzilber M. Vimentin-dependent spatial translocation of an activated MAP kinase in injured nerve. Neuron. 2005;45:715–726. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham P, Frei KP, Woo W, Truong DD. Molecular defects of the dystonia-causing torsinA mutation. NeuroReport. 2006;17:1725–1728. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3280101220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostasy K, Augood SJ, Hewett JW, Leung JC, Sasaki H, Ozelius LJ, Ramesh V, Standaert DG, Breakefield XO, Hedreen JC. TorsinA protein and neuropathology in early onset generalized dystonia with GAG deletion. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;12:11–24. doi: 10.1016/s0969-9961(02)00010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarria AJ, Lieber JG, Nordeen SK, Evans RM. The presence or absence of a vimentin-type intermediate filament network affects the shape of the nucleus in human SW-13 cells. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:1593–1607. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.6.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sena-Esteves M, Tebbets JC, Steffens S, Crombleholme T, Flake AW. Optimized large-scale production of high titer lentivirus vector pseudotypes. J Virol Methods. 2004;122:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegert S, Bahn E, Kramer ML, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Hewett JW, Breakefield XO, Hedreen JC, Rostasy KM. TorsinA expression is detectable in human infants as young as 4 weeks old. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2005;157:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg A, Liem RK. Plakins in development and disease. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2189–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr DA, Fischer JA. KASH ‘n Karry: the KASH domain family of cargo-specific cytoskeletal adaptor proteins. BioEssays. 2005;27:1136–1146. doi: 10.1002/bies.20312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres GE, Sweeney AL, Beaulieu JM, Shashidharan P, Caron MG. Effect of torsinA on membrane proteins reveals a loss of function and a dominant-negative phenotype of the dystonia-associated DeltaE-torsinA mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15650–15655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308088101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan A, Breakefield XO, Bhide P. Developmental patterns of torsinA and torsinB expression. Brain Res. 2006;1073–1074:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiche G. Role of plectin in cytoskeleton organization and dynamics. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2477–2486. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.17.2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsen K, Litjens SH, Kuikman I, Tshimbalanga N, Janssen H, van den Bout I, Raymond K, Sonnenberg A. Nesprin-3, a novel outer nuclear membrane protein, associates with the cytoskeletal linker protein plectin. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:799–810. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsen K, Ketema M, Truong H, Sonnenberg A. KASH-domain proteins in nuclear migration, anchorage and other processes. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:5021–5029. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worman HJ, Gundersen GG. Here come the SUNs: a nucleocytoskeletal missing link. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:67–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Gong S, Zhao Y, LeDoux MS. Developmental expression of rat torsinA transcript and protein. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;152:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi F, Dang MT, Mitsui S, Li J, Li Y. Motor deficits and hyperactivity in cerebral cortex-specific Dyt1 conditional knockout mice. J Biochem. 2008;143:39–47. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young KG, Pinheiro B, Kothary R. A Bpag1 isoform involved in cytoskeletal organization surrounding the nucleus. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.