Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine 1) symptoms; 2) pain characteristics (intensity, location, quality); 3) pain medications and nonpharmacological strategies used for pain; 4) thoughts and feelings; and 5) health care visits. We also examined the relationship between pain and sleep.

Data Sources

Pain and symptoms were entered on an electronic e-Diary using a smartphone and were remotely monitored by an advanced practice registered nurse. Sixty-seven children and adolescents (10 to 17 years) reported mild to severe pain at home that did not require health care visits. Symptoms reported were: 1) general symptoms such as tiredness/fatigue (34.7%), headache (20.8%), yellowing of the eyes (28.4%); 2) respiratory symptoms such as sniffling (32.9%), coughing (19.1%), changes in breathing (10.0%); and 3) musculoskeletal symptoms such as stiffness in joints (15.8%). A significant negative correlation was found between pain and sleep (r = −0.387, p=0.024). Factors that predict pain included previous history of SCD related events, symptoms, and negative thoughts.

Conclusion

Pain and multiple symptoms entered on a web-based e-Diary were remotely monitored by an APRN and prompted communications, further evaluation, and recommendations.

Implications for Practice

Remote monitoring using wireless technology may facilitate timely management of pain and symptoms and minimize negative consequences in SCD.

Keywords: sickle cell disease, remote monitoring, pain, symptoms, wireless technology, smartphone, children, adolescents

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is a genetic blood disorder that affects the shape and structure of red blood cells (sickle-shaped), limiting the blood flow and its ability to carry oxygen. It is characterized by microvascular occlusion, hypoxemia, hypoxia, hemolytic anemia, and jaundice (NIH, 2002; Pack-Mabien & Haynes, 2009). Multiple pathologic processes are associated with SCD that includes inflammation, reperfusion injury, hemolysis, oxidant stress, and increased adhesion of the sickled red blood cells to vascular endothelium.

Although there are many types of SCD, the most common type is the βS / βS – hemoglobin SS (HgbSS), which occurs in 65% of the population in US. Infants with HgbSS typically present with hemolysis and anemia by 6 to 12 months. The second type is βS / βc – hemoglobin SC (HgbSC), which occurs in 25%, and infants present with no anemia or mild anemia by 12 months. The less common types are βS / β+ – hemoglobin S beta+ thalassemia (HgbSβ+) and βS / β0 – hemoglobin S beta0 thalassemia (HgbSβ°), which occurs in 8% and 2% respectively. They present with no anemia or mild anemia by 6 to 12 months (NIH, 2002; Pass, Lane, Fernhoff, Hinton, Panny, et al., 2000; Steinberg, 2008). The severity of SCD symptoms varies according to the amount of normal and abnormal beta globin produced. Individuals with HgbSS have the more severe symptoms with recurrent sickle-cell pain crises, acute organ syndromes, and chronic hemolytic anemia. The HgbSC type may cause similar, milder symptoms as HgbSS, but less anemia due to the higher hemoglobin level. When no beta globin (HgbSβ°) is produced, the symptoms are almost identical to HgbSS, with severe cases needing chronic blood transfusions (Kohne, 2011; Steinberg, 2008).

Many complications may occur that involves different organs such as splenic sequestration, cerebrovascular accident, acute chest syndrome, pulmonary hypertension, priapism, cholelithiasis, bone infarctions, and retinopathy (NIH, 2002; Pack-Mabien & Haynes, 2009). The recurrent vaso-occlusion may damage organs (renal, lung, liver), delay puberty, and affect neurocognition (Rees, Williams & Gladwin, 2010; Tripathi, Jerrell, & Stallworth, 2011). Some individuals with SCD begin having symptoms during the first year of life, presenting with dactylitis (hand-foot syndrome), febrile illness and infections, or aplastic crisis. Symptoms and complications differ for each person.

The acute painful episode from blocked blood vessels is the most common complication, and the most common reason that individuals with SCD go to an emergency room or hospital (Rees, et al., 2010; Tripathi, et al., 2011). Sickle cells travel through small blood vessels, get trapped, block the blood flow and cause acute onset of pain that can last for brief or prolonged periods of time. Acute episodes of pain may require hospitalizations for treatment of pain that include predominantly opioids, such as morphine (Jacob, Miaskowski, Savedra, Beyer, Treadwell, et al., 2003; Jacob, Hockenberry, & Mueller, et al., 2008a) and hydromorphone (Jacob, Hockenberry, & Mueller, 2008b). The pain may be accompanied by complications to organs as a result of the sickled red blood cells blocking blood flow to the lungs, spleen, kidneys, bones, liver, and brain (Rees, et al., 2010).

Although children and adolescents with SCD have benefited from improved medical treatment for pain and symptoms, accessing these treatments requires continuity of care with health care providers (hematologist, pain specialists, advanced practice registered nurses). They require periodic prescription and refill of pain medications (opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, adjuvant medications). They require periodic monitoring of the benefits and side effects of investigational treatments such as hydroxyurea. They require preventive care for early detection of SCD related complications that includes transcranial Doppler ultrasound, echocardiogram, ophthalmology exam, pulmonary function tests, complete blood count with differential and reticulocyte counts, chemistries, ferritin level, hepatitis panel, and urinalyses (NIH, 2002). They require follow-up assessment and evaluation of risk factors, early recognition and treatment of SCD related complications such as pulmonary hypertension, cerebrovascular accident, acute chest syndrome, splenic sequestration, priapism, gall bladder disease, and organ damage (NIH, 2002; Pack-Mabien & Haynes, 2009). They require annual reminders for preventive care such as pneumococcal-conjugated vaccine (Prevnar), pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (Pneumovax), and other routine immunizations to prevent infections (NIH, 2002). They need prompt and progressive management of acute pain episodes. They require psychosocial support for emotional difficulties, such as anxiety, body dissatisfaction, and poor social adjustment (Hijmans, Grootenhuis, Oosterlaan, Last, Heijboer, et al., 2009; Simon, Barakat, Patterson, & Dampier, 2009; Unal, Toros, Kütük, &Uyanıker, 2011).

Despite the importance of continuity of care, almost half of the children and adolescents with SCD were “no shows” or have “missed appointments” with regularly scheduled clinic visits (Crosby, Modi, Lemanek, Guilfoyle, Kalinyak et al., 2009). Barriers to clinic attendance identified by Crosby and colleagues (2009) were dissatisfaction with clinical care, poor communication, long waiting periods, negative experiences with multiple medical providers, inconvenient and conflicting schedules, long distance travel time, and other transportation issues. Communication between patient and provider was reported to be one of the most important factors in attendance for scheduled appointments (Crosby, et al., 2009).

Learning to communicate and connect effectively with hematologists and pediatric pain specialists in a timely manner requires children and youth with SCD to have access to technology that is simple and easy to use. Innovative approaches such as advances in telehealth and internet technology have been shown to improve access to knowledgeable health care providers and improved health outcomes (Harper, 2003; Spittaels, De Bourdeaudhuij, & Vandelanotte, 2007). Palermo, Valenzuela, & Stork (2004) found that higher compliance to daily diary completion and accuracy in diary reporting occurred when youths with SCD used electronic pain diaries (e-diaries). Advances in technology have also allowed delivery of behavioral interventions using computer- and internet-based programs for a range of conditions including pain management in youth with chronic medical conditions (Hicks, von Baeyer, & McGrath, 2006; Ritterband, Cox, Walker, Kovatchev, McKnight et al., 2003). These e-health interventions have been reported to decrease barriers to continuity of care such as limited access to care due to distant location or travel difficulties and lack of trained knowledgeable health care providers with expertise in SCD (Devineni & Blanchard, 2005; Jerome& Zaylor 2000).

The Institute of Medicine document entitled Crossing the Quality Chasm (2001), emphasizes the importance of patient-provider communication, provision of patient education to gain self-management skills, easy access to web-based monitoring information, and provision of decision support systems to improve the outcomes of care. In response to the call to improve the delivery of health care services, there has been an increase in new technology-based care and disease management support systems (Stinson, Wilson, Gill, Yamada, & Holt, 2009). Health information technology and wireless devices were designed to support patient and provider communications, and encourage patients to become active participants in their own care. Technology also enables health care providers to remotely monitor patients and to detect and prevent potential problems. Therefore preventive interventions maximize patients’ abilities to recognize problems early and minimize complications that lead to hospitalizations and other health care expenses.

We developed the Wireless Intervention Program which has two features: 1) participants answered questions about pain and symptoms twice daily using a web-based e-diary accessible by using a smartphone (Jacob, Stinson, Duran, Gupta, et al., 2012a); and 2) an advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) remotely monitored pain and symptoms, and communicated with participants and parents when needed about pain and symptoms (Jacob, et al, 2012b). The purpose of this study was to examine pain and symptoms in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease who were participating in the Wireless Intervention Program. More specifically, we examined 1) symptoms; 2) pain characteristics (intensity, location, quality); 3) pain medications and nonpharmacological strategies used for pain; 4) thoughts and feelings; and 5) health care visits. We also examined the relationship between pain and sleep. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center and the UCLA Harbor Medical Center.

Methods

Design

A prospective longitudinal design was used to examine pain and symptoms. Participants were asked to use a smartphone to access a web-based e-Diary twice daily between April 2010 and December, 2010. The e-Diary entries were transmitted via a wireless service plan into a secure server and were monitored remotely by an advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) with expertise in SCD.

Sample & Setting

Recruitment was conducted by a community based organization in Southern California, the Sickle Cell Disease Foundation of California (SCDFC). The SCDFC serves the sickle cell community residing in the greater Los Angeles area, the Inland Empire (San Bernardino and Riverside Counties), within approximately a 75-mile radius of Los Angeles and San Diego. The SCDFC offers services to an estimated 5,000 individuals throughout the state of California. The ethnic mix of the population served is approximately 90% African-Americans. The other 10% are Hispanics and other ethnic origins.

Sample Size

A sample size of 76 was determined (a priori) using GPOWER (Erdfelder et al., 1996) to allow detection of an effect size of d=0.20 difference between baseline scores and repeated measures of pain, with alpha of 0.05 and power of 0.80, and also account for a 15% drop out rate. For the current descriptive analysis, the combined sample of 67 allows reasonable accuracy of 95% confidence intervals around means of +/− 0.23 standard deviation units in analyses where one summary measure is available for each subject or as small as +/− 0.08 standard deviation units for the 509 pain ratings.

Eligibility

Eligible participants received flyers and were invited by the special projects coordinator from the SCDFC to participate in the study. Children and adolescents were eligible to participate if: 1) they were 10 to 17 years of age; 2) diagnosed with SCD; 3) able to speak, read, write, and understand English, and 4) able to use the computer and smartphone. They were excluded if they had major cognitive or neurological impairments (as reported by parents) that may have impacted their ability to understand and complete the study procedures.

Measures on the e-Diary

The items on the e-Diary were taken from measures with established reliability and validity (Table 1), and included the following eight items: 1) Symptoms Checklist, which lists 27 symptoms experienced the previous 12 hours that were derived from our previous study (Jacob, Beyer, Miaskowski, Savedra, Treadwell, et al., 2005); 2) 0 to 10 Visual Analog Scales (VAS), for rating of pain “now,” “highest,” and “lowest” pain the previous 12 hours (Tesler, Savedra, Holzemer, Wilkie, Ward, et al., 1991); 3) Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool (Savedra, Holzemer, Tesler, Wilkie, 1993) for marking the locations of pain the previous 12 hours, and indicating the quality of pain using a list of 67 words that describe the affective, evaluative, sensory, and temporal dimensions of pain (Wilkie, Holzemer, Tesler, Ward, Paul, et al., 1990); 4) Medications Checklist for assessing the name, dose, and frequency of medications taken for pain, as well as the amount of relief received from medications the previous 12 hours (Jacob et al., 2003; Jacob, Miaskowski, Savedra, Beyer, Treadwell, et al., 2007); 5) Other Strategies Checklist, which listed non-pharmacological strategies that were used to relieve pain the previous 12 hours (deep breathing, relaxation exercises, heat packs, hot bath/shower, massage, imagery, distraction, talking with friends/parents), as well as the amount of relief received from other strategies the previous 12 hours (Beyer & Simmons, 2004); 6) sleep to assess “How much sleep did you have during the night?”, followed by responses from 0 = did not sleep at all to 10 = slept a lot (Jacob, Miaskowski, Savedra, Beyer, Treadwell, et al., 2006); 7) Thoughts/Feelings checklist that included words to describe thoughts and feelings the previous 12 hours -- happy/delighted/joyful; content/calm; anxious; depressed; angry/mad/upset; fearful/scared/frightened; sad/lonely/gloomy; miserable; worried/bothered; nervous/jittery; ashamed; guilty; tired (Hughes & Kendall, 2009); and 8) health care visits to determine if they went to the Sickle Cell Clinic, a Medical Office, Urgent Care Clinic, Other Clinic, Emergency Department, or Day Hospital, and if the child was hospitalized or discharged from the hospital the previous 12 hours (Jacob, et al, 2012a).

Table 1.

Content of the e-Diary

| Content | Description of Content | Reliability & Validity |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms Checklist | A list of 27 symptoms experienced at home prior to admission to the hospital that were identified by parents, children, and adolescents in our previous study (Jacob, et al., 2005; Jacob, et al., 2012a). |

Content validity of content of the symptoms checklist was determined by a panel of expert clinicians and researchers (Jacob, et al., 2005; Jacob, et al., 2012a). |

| Pain Intensity | Visual Analog Scale of the Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool (APPT) for measurement of highest level, lowest level, and pain level at time of completion (Tesler, et al, 1991). |

r = 0.68 to r = 0.97; correlation of five scales to rate pain intensity of standardized painful stimuli in an analogue situation supporting convergent validity (Tesler, et al, 1991). r = 0.91 test-retest reliability between the visual analog scale, word-graphic rating scales and one of 4 other scales (Tesler, et al, 1991). |

| Pain Location | Body Outline Diagram of the APPT for quantifying the number and percent of pain sites marked on a body outline diagram (Savedra, et al, 1993). |

κ= 0.71; agreement of pair 2 coders on site number (Savedra, et al, 1993). |

| Pain Quality | Word Descriptor List of the APPT for quantifying the number of sensory, affective, evaluative, and temporal quality of pain (Wilkie, et al, 1990) |

r = 0.99; correlation between number of sensory words and number of pain sites r = 0.81; correlation between number of affective words and number of pain sites r = 0.99; correlation between number of evaluative words and number of pain sites r = 0.86; correlation between number of temporal words and number of pain sites (Wilkie, et al, 1990) |

| Medications | A list of medications that were taken at home for pain and symptoms, identified by parents and children and adolescents with sickle cell disease in our previous study |

Content validity of the words to describe the medications that were used for management of pain was determined by a panel of expert clinicians and researchers based on review of the literature and clinical experience (Jacob, et al, 2003;Jacob, et al, 2007; Jacob, et al., 2012a) |

| Strategies for Pain Management |

A list of strategies used for managing pain at home, identified by parents and children and adolescents with sickle cell disease (Beyer, et al, 1999) |

Content validity of the words to describe the nonpharmacological items that were used for management of pain was determined by a panel of expert clinicians and researchers based on review of the literature and clinical experience (Beyer, et al, 1999; Jacob, et al., 2012a) |

| Sleep | “How much sleep did you have during the night?”, followed by a list of responses that were checked: ◻ did not sleep at all,◻ slept a little,◻ slept some, and ◻ slept a lot (assigned the following numbers during analyses – 0, 2.5, 5, 10, respectively assigned to transform nominal level to an interval 0 to 10 scale (Von Bayer, et al., 2000; Waltz, Strickland, Lenz, 2010). |

Content validity of the words to describe the amount of sleep was determined by a panel of expert clinicians and researchers (Jacob, et al, 2006; Jacob, et al., 2012a) |

| Thoughts/Feelings | A list of items that were identified in the literature (Laurent, et al., 1999; Laurent, et al., 2004) that describe a range of thoughts and feelings that children expressed |

Content validity of the words used to describe thoughts and feelings was determined by a panel of expert clinicians and researchers based on review of the literature and clinical experience (Jacob, et al., 2012a) |

| Health care visits | A list of health care visits (sickle cell clinic, doctor’s office emergency department, day hospital, hospital) that are used by children and adolescents with sickle cell disease Jacob, et al., 2012a).. |

Content validity of the words used to describe health care visits was determined by a panel of expert clinicians and researchers based on review of the literature and clinical experience (Jacob, et al., 2012a) |

r: Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficients; κ: Cohen’s Kappa coefficient

Procedures

After consenting procedures, participants were enrolled and attended an information session on the use of a smartphone for accessing the web-based e-Diary (Jacob, et al, 2012a) which included questions related to symptoms, pain, medications and other strategies used to relieve pain and symptoms,sleep, thoughts/feelings, and health care utilization. Participants were instructed to complete their e-Diary two times each day and received automated reminders if e-Diary was not completed.

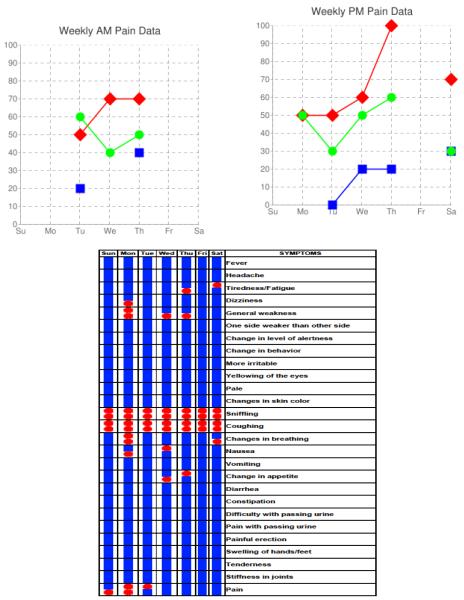

The APRN monitored entries daily on the APRN web-interface where participants’ e-Diary entries could be seen (Figure 1). The APRN contacted participants (via text messages or phone calls) in the event that pain and other symptoms required attention, to maintain contact, and monitor their progress. Smartphones with wireless service plans were provided at no cost. The participants were able to send unlimited text messages and make unlimited phone calls as needed to the APRN. The research staff and programmer from the University of California Los Angeles Computer Science Department, were available for technical assistance and problem solving when needed. Participants received $30 gift cards during the information session and at the end of 3 and 6 months.

Figure 1.

Example of web-interface screens viewed remotely by the APRN for monitoring of pain (top) and symptoms (bottom).

Data Analyses

Diary entries were readily accessible on Excel spreadsheets at time of entry. Data were then imported from Excel to the statistical software (SPSS version 19, Chicago, IL) for analyses. Descriptive statistics were used (means, standard deviations, frequencies, percentages) to quantify: 1) the frequency of entries and type of symptoms; 2) pain intensity ratings; 3) number of areas on the body outline indicating location of pain; 4) the number of word descriptors used to describe the quality of pain; 5) medications and other strategies used for pain; 6) sleep; 7) thoughts/feelings; and 8) health care visits that were experienced by children and adolescents with SCD.

Pain was categorized as mild for pain scores of 3 or less on the 0 to 10 VAS; moderate for VAS pain scores of 4 to 6; and severe for VAS pain scores 7 to 10. Pearson correlation was used to examine the relationship between pain and sleep (Munro, 2004). Since participants were enrolled in the study at different times, there were variations in length of participation. Therefore, we calculated the average number of pain and symptoms occurrences per week. The Repeated Measures Zero-Inflated Poisson (ZIP) Model (Lee, Wang, Scott, Yau, & McLachlan, 2006) was used to determine factors that predict the number of pain occurrences per week.

RESULTS

A total of 76 children and adolescents with SCD from the Sickle Cell Disease Foundation of California were screened, assented, and enrolled after parental consent was obtained between April, 2010 and December, 2010. Participants were withdrawn if the smartphone was lost or damaged (n=5), and if the AM and PM questions were not fully completed (n=4). Data presented are from the 67 participants who completed the study. They ranged in age from 10 to 17 years (median age was 13.0 ± 1.9 years); 54.3% were females. Their grade levels ranged between 4th grade and 12th grade; the mean was 7th grade.

A majority of participants had either HgbSS (47.8%) or HgbSC (28.4%). The majority were African-Americans (95.5%) with a few Hispanics (4.5%). Some reported having a history of acute chest syndrome (46.3%), splenectomy (11.9%) and/or iron overload (13.4%). Few reported having other sickle cell related complications such as cerebrovascular accident (7.5%), avascular necrosis (6%), splenic sequestration (6%), leg ulcers (6%), priapism (6%), pulmonary hypertension (3%), and cholecystectomy (3%). Some reported having history of asthma (28.4%) and other medical conditions (23.9%) unrelated to SCD.

The participants had a total of 9216 e-Diary entries between April, 2010 and December, 2010; these entries include 4573 morning (49.5%) and 4653 evening (50.5%) entries.

Symptoms

The number of symptom events ranged from 4 to 7 symptoms per patient per week (Table 2). The most frequently reported symptoms were: 1) general symptoms such as tiredness/lack of energy (34.7%), headache (20.8%), yellowing of the eyes (28.4%); 2) respiratory symptoms such as sniffling (32.9%), coughing (19.1%), changes in breathing (10.0%); and 3) musculoskeletal symptoms such as stiffness in joints (15.8%) and muscle tenderness (8.4%).

Table 2.

Most Frequent Symptoms (N=9216 e-Diary entries)

| General Symptoms | |

| Tiredness/fatigue | 34.7% |

| Headache | 20.8% |

| Yellowing of the eyes | 28.4% |

| Respiratory symptoms | |

| Sniffling | 32.9% |

| Coughing | 19.1% |

| Changes in breathing | 10.0% |

| Musculoskeletal symptoms | |

| Stiffness in joints | 15.8% |

| Muscle tenderness | 8.4% |

Pain

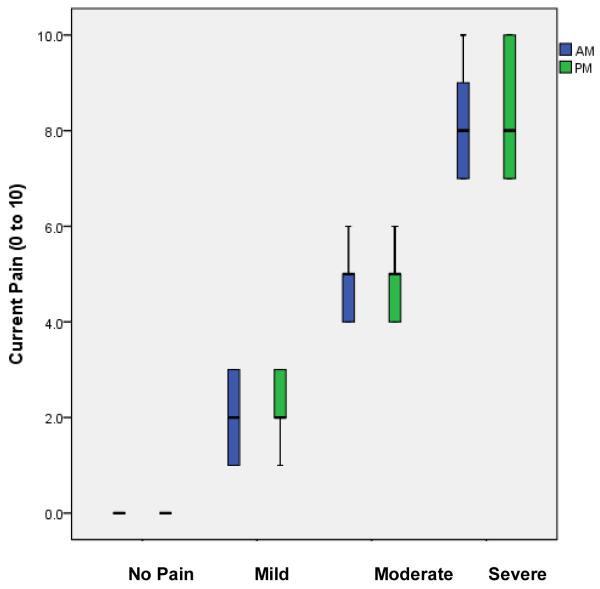

The incidence of pain events ranged from 0 to 2 pain entries per patient per week (Table 3). At the time of e-Diary completion, participants reported having pain in 509 entries; these pain entries include 217 morning (42.6%) and 292 evening (57.4%) entries. Pain ratings ranged from 1.0 to 10.0 (on 0 to 10 Visual Analog Scale) with an overall mean of 4.1 ± 2.2. No significant difference was found in current pain ratings between the morning (4.2 ± 2.3) and evening (4.0 ± 2.2) ratings. No significant difference was found in pain ratings (4.1 ± 1.6) of children 10 to 13 years when compared to pain ratings (4.0 ± 1.8) of adolescents 14 to 17 years. The overall highest pain rating was 5.2 ± 2.5 and the overall lowest pain rating was 2.6 ± 1.9. Of the 509 entries, current pain was rated as mild in 226 (44.4%) entries with mean pain 2.7 ± 0.8; moderate in 213 (41.8%) entries with mean pain 4.7 ± 0.6; and severe in 70 (13.8%) entries with mean 8.4 ± 1.2 (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Pain at Home (N=509 entries)

| Incidence | 0 to 2 per patient/week |

| Number of Entries with Pain | n (%) |

| Morning | 217 (42.6%) |

| Evening | 292 (57.4%) |

| Overall mean | 4.1 ± 2.2 (0 to 10 VAS) |

| Mild (mean 2.7 ± 0.8) | 226 (44.4%) |

| Moderate (mean 4.7 ± 0.6) | 213 (41.8%) |

| Severe (mean 8.4 ± 1.2) | 70 (13.8%) |

VAS: Visual Analog Scale

Figure 2.

Mean pain intensity ratings at time of e-diary entry

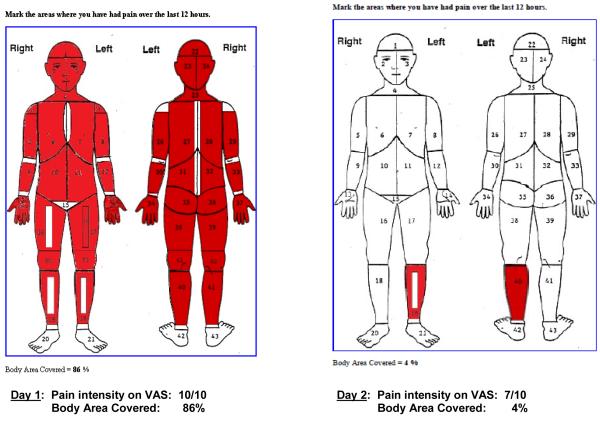

The percent of body areas marked on the body outline diagram ranged from 63% to 86% when they were experiencing severe pain. The most frequently marked areas were front (20.3%) and back (22.4%) of chest, abdomen (22.5%), lower back (25.8%), and knees (16.5%). As illustrated in Figure 3, the spatial distribution of pain may change from day 1 (86% marked areas) to day 2 (5% marked areas) whereas the pain intensity ratings remained severe (10.0 on day 1, to 7.0 on day 2 on 0 to 10 VAS scale).

Figure 3.

Example of Body Outline Diagram with pain markings on day 1 and day 2 that decreased remarkably in spatial distribution of the pain (86% on day 1 to 4% to day 2); but pain intensity ratings remained severe (10 on day 1 to 7 on day 2; pain measured on 0 to 10 VAS)

The most frequently used words describing the quality of pain was annoying (44.0%), uncomfortable (49.5%), hurt (42.6%), ache (38.9%), and throbbing (37.7%). The most frequently selected sensory, affective, evaluative, and temporal quality word descriptors are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Quality of Sickle Cell Pain at Home (N=509)

| Sensory | Number of Entries (%) | |

| Hurt | 217 (42.6%) | |

| Ache | 198 (38.9%) | |

| Throbbing | 192 (37.7%) | |

| Pressure | 163 (32.0%) | |

| Tight | 153 (30.0%) | |

| Pounding | 103 (20.2%) | |

| Sharp | 96 (18.8%) | |

| Beating | 90 (17.6%) | |

| Cramping | 88 (17.2%) | |

| Stiff | 79 (15.5%) | |

| Sore | 78 (15.3%) | |

| Affective | ||

| Suffocating | 138 (27.1%) | |

| Crying | 134 (26.3%) | |

| Awful | 125 (24.5%) | |

| Terrifying | 84 (16.5%) | |

| Evaluative | ||

| Uncomfortable | 252 (49.5%) | |

| Annoying | 224 (44.0%) | |

| Bad | 144 (28.3%) | |

| Never goes away | 121 (23.8%) | |

| Uncontrollable | 104 (20.4%) | |

| Horrible | 95 (18.7%) | |

| Miserable | 69 (13.6%) | |

| Temporal | ||

| Always | 194 (38.1%) | |

| Forever | 149 (29.3%) | |

| Comes and goes | 134 (26.3%) | |

| Sometimes | 124 (24.4%) | |

| Comes suddenly | 116 (22.8%) | |

| Once in awhile | 114 (22.4%) |

Pain Management

The most frequently used medications were ibuprofen indicated in 202 entries and acetaminophen with codeine in 62 entries. When asked how much did the medicine help to relieve the pain (0=did not help at all to 10=helped a lot), the mean relief score was 4.1 ± 2.1 for ibuprofen and 4.3 ± 1.9 for acetaminophen with codeine. Other strategies for pain management were distraction (n=158 entries), heat packs (n=114 entries), bath (n=92 entries), deep breathing (n=44 entries), relaxation (n=39 entries), massage (n=39 entries), and talking (n=32 entries).

Thoughts/Feelings

Over half of the entries indicated that the participants were happy (62.0%) and less than half were content (41.4%). In over a quarter of the entries (28.8%), participants indicated they were tired. Few entries indicated they were anxious (5.3%), angry (5.2%), sad (3.3%), miserable (2.6%), worried (2.1%), and depressed (2.1%).

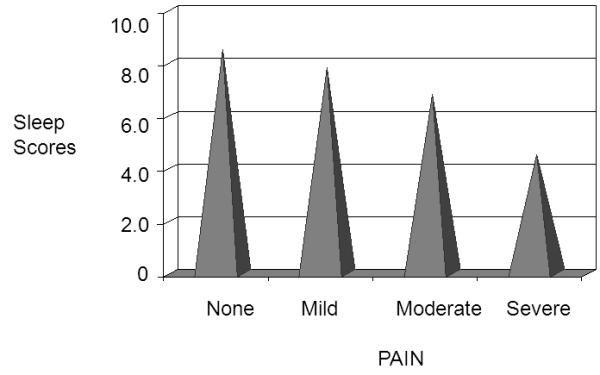

Sleep

Over half of the participants (54.8%) indicated having “slept quite a bit” during the night and almost a third (31.7%) reported having “slept some”. A few participants indicated they “slept a little” (7.3%). A significant negative correlation (r = −0.387, p=0.024) was found between pain and sleep. For the morning entries when participants reported no pain, the mean sleep score was high (8.1 ± 1.2 on 0 = did not sleep at all to 10 = slept a lot). Sleep scores decreased with increasing pain. Mean sleep scores were 7.7 ± 1.7 when their pain was mild, 6.9 ± 2.7 when their pain was moderate, and 4.8 ± 3.8 when their pain was severe (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

High sleep scores when no and mild pain, and lower sleep scores with moderate and severe pain

Health Care Use

Participants indicated that they went to the sickle cell clinic (n=29 entries), medical office (n=28 entries), urgent care clinic (n=12 entries), or other clinic (n=31 entries). Few indicated that they were in the ED (n=11 entries). Some reported admission to a Day Hospital (n=58 entries), an acute care hospital (n=74 entries) or discharged (n=30 entries) from an acute care hospital.

Factors that Predict Pain

Factors that predict the number of pain occurrences per week after controlling for time were: 1) number of previous history of SCD related events (e.g., acute chest syndrome, splenectomy, cerebrovascular accident) reported (β=0.22 ± 0.10, p=0.04), 2) number of symptoms per week (β=0.09 ± 0.02, p<0.0001), and 3) number of negative thoughts per week (β=0.02 ± 0.01, p=0.01). Other factors such as age, gender, number of pain episodes per year, and number of hospitalizations and clinic visits per year, were not significant predictors of pain occurrences per week.

Discussion

The Wireless Pain Intervention Program for at risk youths with sickle cell disease, included a web interface for an APRN to remotely monitor pain and symptoms that children and adolescents entered into a web-based e-Diary accessible by using a smartphone. Participants reported symptoms at home, such as tiredness/fatigue, headache, and respiratory symptoms, which is consistent with previous reports (Jacob, et al, 2005, Jacob, Sockrider, Dinu, Acosta, & Mueller, 2010).

Participants reported pain at home with the most frequently marked areas as the chest, abdomen, lower back, and knees. A majority of the pain episodes were mild or moderate and often did not require clinic, hospital, or emergency department visits. These findings were similar to other reports (Dampier, Ely, Brodecki, & O’Neal, 2002a; Dampier, Ely, Brodecki, & O’Neal, 2002b; Dampier, et al., 2004). Consistent with findings from other studies, we found significant correlations between pain and sleep, with lower sleep scores when pain ratings were more severe (Palermo & Kiska 2005; Palermo & Fonareva, 2006; Palermo, et al., 2007). Similar to previous studies, children reported the most frequently used strategies for pain management at home were ibuprofen and acetaminophen with codeine (Dampier, et al., 2002 ; Beyer & Simmons, 2004; Beyer, Simmons, Woods, & Woods, 2000).

To our knowledge, this is the first study in which children and adolescents with SCD used smartphones to report their symptoms and pain to an APRN who helped them to deal with and resolve their problems using a wireless system. The majority of internet and mobile technology programs reported to date are informational with multimedia and interactive personalized features to deliver information for pain and symptom management (Abascal, Bruning –Brown, Winzelberg, Dev, & Taylor, 2004; Bruning-Brown, Winzelberg, Abascal, & Taylor, 2004; Celio, Winzelberg, Wilfley, Eppstein-Herald, Springer, et al., 2000; Hicks, von Baeyer & McGrath 2006; Liss, Glueckauf, & Ecklund-Johnson, 2002 ; Long & Palermo, 2009; Luce, Osborne, Winzelberg, Das, Abascal, et al., 2005; Rabascam, 2000 ; Ritterband, et al., 2003). In contrast to previous studies that used web-based internet intervention to deliver information (Long & Palermo, 2009; Rabascam, 2000) and promoted communications using web portals (Leveille, Huang, Tsai, Weingart, & Iezzoni, 2008; Glasgow & Toobert, 2000; Peters & Davidson, 1998 ; Gustafson, Hawkins, & Pingree, 2001; Gustafson, 1999), the participants in our study self-monitored pain and symptoms and personally interacted with the APRN through text messages and direct phone calls using the smartphone.

The APRN monitored entries daily on the APRN web-interface where participant e-Diary entries may be seen and contacted participants (via text messages or phone calls) in the event that pain and other symptoms required attention, to maintain contact, and monitor their progress. The APRN provided ongoing coaching, psychosocial support, educational interventions (including web-based resources), and referrals to providers (hematologist, pediatric pain specialist, physical therapy, primary care providers) as needed. Participants contacted the APRN via text messages or phone calls as needed if they had thoughts, questions, and wanted to share information related to health (Jacob, et al, 2012b).

Although we demonstrated the ability of the participants to self-monitor pain and symptoms, and an APRN with SCD expertise to remotely monitor entries, we do not know if the communications and text message exchange between the APRN and participants made a difference in the outcomes of care. Future studies are needed to measure the outcomes and benefits of wireless technology and text message communications with health care providers with expertise in SCD. The APRN established open communications and maintained ongoing connection with participants, particularly about management of pain and symptoms at home, as well as other psychosocial concerns that potentially minimized health care visits. Examples of outcomes that need to be measured in future studies include health care use, frequency and duration of pain episodes, pain coping, sleep, and quality of life.

The successful use of smartphones for self-monitoring of pain and symptoms, the ability of the APRN to remotely monitor them, and the ongoing connection and open communications between pediatric participants with SCD and the APRN will lead to further innovations in the use of wireless technology that may transform the assessment and management of pain and symptoms in individuals with SCD. Future studies with larger sample sizes in multiple sites and health care providers with expertise in SCD are needed to demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach. Prospective randomized studies are needed to identify individuals with SCD who may benefit from proactive management and follow-up, and improved monitoring not only of pain and symptoms but also of the efficacy of therapeutic interventions.

The web interface that was developed in the study could facilitate timely management of pain and symptoms and minimize negative consequences of prolonged unrelieved pain and symptoms in sickle cell disease. Many young individuals with sickle cell disease rely upon their parents to help them to relieve their pain and symptoms, and to seek health care services. This dependence upon parents could create a barrier to self-reliance as these children and adolescents approach adulthood. Effective and ongoing communication between an experienced APRN and the pediatric patient using wireless technology builds upon the foundation to help children gain the skills to cope with their symptoms and assume an active role in prevention and treatment of their pain and symptoms, and health care utilization. The wireless intervention program model used in this study has the potential to improve communication between children and adolescents with other chronic diseases and their health care providers. It could be a prototype for remote monitoring of pain and symptoms among children and adolescents with cancer, cystic fibrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and other diseases that involve pain and disabling symptoms.

This study has several limitations. First of all, only families who had access to the services of the Sickle Cell Disease Foundation of California (SCDFC) were included. Thus, the results may not be generalizable to families who live in other regions, or those who access care from medical centers. Second, the data were transmitted directly onto a server using a wireless service provider. Therefore, the web-based interface and the APRN’s ability to remotely monitor pain and symptoms were highly dependent on compliance with completing the web-based e-Diary and the participants having wireless service in areas where wireless connectivity was possible. Third, the participants in our study were older children. Therefore, remotely monitoring of pain and symptoms in younger children might be feasible only if parents were able to complete the e-Diary; we did not recruit parents to participate in the study. Fourth, the web-based e-Diary was available only in English, a factor that limits its utilization to children and adolescents who do not speak, read, write, and understand English. Finally, children and adolescents who have significant cognitive or neurological impairments may not be able to use the web-based e-Diary unless their parents were able to complete the e-Diary for them. This change in protocol would require parents to participate in the intervention.

In conclusion, the children and adolescents with sickle cell disease reported pain and multiple symptoms they experienced at home and included general (fever, tiredness), respiratory (cough, sniffles) and musculoskeletal symptoms (joint stiffness, muscle tenderness). They reported different pain levels from none to severe, and those who had higher pain scores also reported lower sleep scores. Factors that predicted pain included SCD related events, symptoms, and negative thoughts. They were able to use a smartphone to access the web-based e-Diary to report pain and symptoms. The APRN was able to remotely monitor the pain and symptoms that prompted communications, further evaluation, and recommendations. Future studies are recommended to examine the effects of using wireless technology, on the number of health care visits, pain coping, sleep, function, quality of life and other outcomes in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease.

Acknowledgements

Funding was received from the National Institute of Health, National Heart, Blood, & Lung Institute, American Recovery & Reinvestment Act Grant #1RC1 HL100301-01. We thank all the children and adolescents from the Sickle Cell Disease Foundation of California (SCDFC) who participated in the study. We are grateful to Mary Brown at the SCDFC and their staff, particularly Tara Ragin, who facilitated accessing participants, screening and recruitment, scheduling of participants, and making private room arrangements during enrollment and follow-up procedures. The authors wish also to acknowledge the research assistance provided by Meredith Pelty, PsyD, Christopher Hodge, MA, Victoria Wong, BS, Ashley Ponce, BS, RN, Cecilia Dong, BS, RN, and the University of California Los Angeles, nursing students, Miya Villanueva, Anjana Gokhale, Ryann Engelder, and Danica Nizich for assisting with different aspects of the research. We appreciate the technical expertise of Ankur Gupta and his faculty mentor, Dr. Mario Gerla from the UCLA Department of Computer Science who developed the computer software for the web-based e-Diary accessible by smartphone and the APRN web interface, and provided technical assistance during the study. Finally, we would like to thank Dr. Judith E. Beyer for her editorial assistance on the final draft of this manuscript.

References

- Abascal L, Bruning–Brown J, Winzelberg AJ, Dev P, Taylor CB. Combining universal and targeted prevention for school-based eating disorder programs. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35(1):1–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.10234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer JE, Simmons L, Woods G, Woods P. Judging the effectiveness of analgesia for children and adolescents during vaso-occlusive events of sickle cell disease. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2000;19(1):63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer JE, Simmons LE. Home treatment of pain for children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Pain Management Nursing. 2004;5(3):126–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruning–Brown J, Winzelberg AJ, Abascal LB, Taylor CB. An evaluation of an Internet-delivered eating disorder prevention program for adolescents and their parents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35(4):290–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio AA, Winzelberg AJ, Wilfley DE, Eppstein-Herald D, Springer EA, Dev P, Taylor CB. Reducing risk factors for eating disorders: comparison of an Internet- and a classroom-delivered psychoeducational program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(4):650–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby LE, Modi AC, Lemanek KL, Guilfoyle SM, Kalinyak KA, Mitchell MJ. Perceived barriers to clinic appointments for adolescents with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Hematology & Oncology. 2009;31(8):571–6. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181acd889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampier C, Ely E, Brodecki D, O’Neal P. Home management of pain in sickle cell disease: A daily diary study in children and adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Hematology Oncology. 2002a;24(8):643–647. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampier C, Ely B, Brodecki D, O’Neal P. Characteristics of pain managed at home in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease by using diary self-reports. Journal of Pain. 2002b;3(6):461–470. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2002.128064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampier C, Setty BN, Eggleston B, Brodecki D, O’Neal P, Stuart M. Vaso-occlusion in children with sickle cell disease: clinical characteristics and biologic correlates. Journal of Pediatric Hematology Oncology. 2004;26(12):785–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devineni T, Blanchard EB. A randomized controlled trial of an Internet-based treatment for chronic headache. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2005;43(3):277–292. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Toobert DJ. Brief, computer-assisted diabetes dietary Self-management counseling: Effects on behavior, physiologic outcomes, and quality of life. Medical Care. 2000;38:1062–1073. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200011000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, Pingree S, et al. Effect of computer support on younger women with breast cancer. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;(16):435–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, Boberg E, et al. Impact of a patient-centered, computer-based health information/support system. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 1999;(16):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper AC. Telehealth. In: Roberts MC, editor. Handbook of pediatric psychology. 3rd ed Guilford Press; New York: 2003. pp. 735–746. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, McGrath PJ. Online psychological treatment for pediatric recurrent pain: A randomized evaluation. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31(7):724–736. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans CT, Grootenhuis M, Oosterlaan J, Last BF, Heijboer H, Peters M, et al. Behavioral and emotional problems in children with sickle cell disease and healthy siblings: Multiple informants, multiple measures. Pediatric Blood Cancer. 2009;53(7):1277–83. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AA, Kendall PC. Psychometric properties of the Positive and Negative Affect Scale for Children (PANAS-C) in children with anxiety disorders. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2009;40(3):343–52. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob E, Hockenberry M, Mueller BM, Coates T, Zeltzer L. Analgesic Response to Morphine in Children with Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of Pain Management. 2008a;2(1):179–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob E, Hockenberry M, Mueller BM. Effects of Patient Controlled Analgesia Hydromorphone During Acute Painful Episodes in Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of Pain Management. 2008b;2(1):173–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob E, Miaskowski C, Savedra M, Beyer JE, Treadwell M, Styles L. Management of pain in children with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Hematology & Oncology. 2003;25(4):307–311. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200304000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob E, Beyer JE, Miaskowski C, Savedra M, Treadwell M, Styles L. Are there phases to the acute painful episode in children with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2005;29(4):392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob E, Miaskowski C, Savedra M, Beyer JE, Treadwell M, Styles L. Changes in sleep, eating, and activity levels in children with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2006;21(1):23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob E, Miaskowski C, Savedra M, Beyer JE, Treadwell M, Styles L. Quantification of analgesic use in children with sickle cell disease. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2007;23(1):8–14. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210938.58439.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob E, Sockrider MM, Dinu M, Acosta M, Mueller BM. Respiratory symptoms and acute painful episodes in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Hematology & Oncology Nursing. 2010;27(1):33–39. doi: 10.1177/1043454209344578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob E, Stinson J, Duran J, Gupta A, Gerla M, Lewis MA, Zeltzer L. Usability testing of a smartphone for accessing a web-based e-Diary for self-monitoring of pain and symptoms in sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Hematology & Oncology. 2012a doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318257a13c. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob E, Pavlish C, Stinson J, Duran J, Lewis MA, Zeltzer L. Facilitating pediatric patient-provider communications using wireless technology in sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2012b doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2012.02.004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerome L, Zaylor C. Cyber-Space: Creating a therapeutic environment for telehealth applications. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2000;31(5):478–483. [Google Scholar]

- Kohne E. Hemoglobinopathies: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2011;108(31–32):532–40. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent J, Catanzaro SJ, et al. Development and preliminary validation of the physiological hyperarousal scale for children. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16(4):373–380. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent J, Catanzaro SJ, et al. A measure of positive and negative affect for children: scale development and preliminary validation. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11(3):326–338. [Google Scholar]

- Lee AH, Wang K, Scott JA, Yau KW, McLachlan GJ. Multi-level zero-inflated Poisson regression modeling of correlated count data with excess zeros. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2006;15:47–61. doi: 10.1191/0962280206sm429oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leveille S,G, Huang A, Tsai S,B, Weingart SN, Iezzoni LI. Screening for chronic conditions using a patient internet portal: Recruitment for an internet-based primary care intervention. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(4):472–5. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0443-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss H, Glueckauf RL, Ecklund-Johnson EP. Research on telehealth and chronic medical conditions: Critical review, key issues, and future directions. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2002;47:8–30. [Google Scholar]

- Long AC, Palermo TM. Brief report: Web-based management of adolescent chronic pain: Development and usability testing of an online family cognitive behavioral therapy program. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34(5):511–6. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce, Kristine H, Megan I Osborne, Andrew J Winzelberg, Das Smita, Liana B. Abascal, Celio AA, Wilfley DE, Stevenson D, Dev P, Taylor CB. Application of an algorithm-driven protocol to simultaneously provide universal and targeted prevention programs. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;37(3):220–6. doi: 10.1002/eat.20089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro BH. Statistical Methods for Health Care Research. 5th edition Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: PA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute . Disease and conditions index. Sickle cell anemia: who is at risk? US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2009. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/dci/Diseases/Sca/SCA_WhoIsAtRisk.html. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health . Management of Sickle Cell Disease. 4th edition. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Division of Blood Diseases and Resources; 2002. NIH Publication No. 02-2117. [Google Scholar]

- Nebor D, Bowers A, Hardy-Dessources MD, Knight-Madden J, Romana M, Reid H, Barthélémy JC, Cumming V, Hue O, Elion J, Reid M, Connes P. CAREST Study Group. Frequency of pain crises in sickle cell anemia and its relationship with the sympatho-vagal balance, blood viscosity and inflammation. Haematologica. 2011;96(11):1589–94. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.047365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pack-Mabien A, Haynes J. A primary care provider’s guide to preventive and acute care management of adults and children with sickle cell disease. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2009;21(5):250–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo TM, Valenzuela D, Stork PP. A randomized trial of electronic versus paper pain diaries in children: Impact on compliance, accuracy, and acceptability. Pain. 2004;107(3):213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo TM, Kiska R. Subjective sleep disturbances in adolescents with chronic pain: Relationship to daily functioning and quality of life. Journal of Pain. 2005;6:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo T, Fonareva I. Sleep in children and adolescents with chronic pain. Pediatric Pain Letter. 2006;8:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Palermo TM, Toliver-Sokol M, Fonareva I, Koh JL. Objective and subjective assessment of sleep in adolescents with chronic pain compared to healthy adolescents. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2007;23(9):812–20. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318156ca63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pass KA, Lane PA, Fernhoff PM, Hinton CF, Panny SR, Parks JS, Pelias MZ, Rhead WJ, Ross SI, Wethers DL, Elsas LJ. U.S. newborn screening system guidelines II: follow-up of children, diagnosis, management, and evaluation. Statement of the Council of Regional Networks for Genetic Services. Journal of Pediatrics. 2000;137(Suppl):S1–46. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.109437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters AL, Davidson MB. Application of a diabetes managed care program. The feasibility of using nurses and a computer system to provide effective care. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1037–1043. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.7.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabascam L. Taking telehealth to the next step. Monitoring Psychology. 2000;31(36):37. [Google Scholar]

- Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 2010;376(9757):2018–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61029-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritterband LM, Cox DJ, Walker LS, Kovatchev B, McKnight L, Patel K, Borowitz S, Sutphen J. An Internet intervention as adjunctive therapy for pediatric encopresis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(5):910–7. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savedra MC, Holzemer WL, Tesler MD, Wilkie DJ. Assessment of postoperation pain in children and adolescents using the Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool. Nursing Research. 1993;42(1):5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon K, Barakat LP, Patterson CA, Dampier C. Symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescents with sickle cell disease: The role of intrapersonal characteristics and stress processing variables. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2009;40(2):317–30. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spittaels H, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Vandelanotte C. Evaluation of a website-delivered computer-tailored intervention for increasing physical activity in the general population. Preventive Medicine. 2007;44(3):209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg MH. Sickle cell anemia, the first molecular disease: Overview of molecular etiology, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approaches. Science World Journal. 2008;8:1295–1324. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson J, Wilson R, Gil l. N., Yamada J, Holt J. A systematic review of internet-based self-management interventions for youth with health conditions. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34(5):495–510. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesler MD, Savedra MC, Holzemer WL, Wilkie DJ, Ward JA, Paul SM. The word-graphic rating scale as a measure of children’s and adolescents’ pain intensity. Research in Nursing & Health. 1991;14(5):361–371. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770140507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi A, Jerrell JM, Stallworth JR. Clinical complications in severe pediatric sickle cell disease and the impact of hydroxyurea. Pediatric Blood Cancer. 2011;56(1):90–4. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unal S, Toros F, Kütük MÖ, Uyanıker MG. Evaluation of the psychological problems in children with sickle cell anemia and their families. Pediatric Hematology & Oncology. 2011;28(4):321–8. doi: 10.3109/08880018.2010.540735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Baeyer CL, Hicks CL. Support for a common metric for pediatric pain intensity scales. Pain Research and Management. 2000;5(2):157–60. [Google Scholar]

- Waltz C, Strickland OL, Lenz E. Measurement in Nursing and Health Research. 4th Edition Springer Publishing Company; New York: [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie DJ, Holzemer WL, Tesler MD, Ward JA, Paul SM, Savedra MC. Measuring pain quality: Validity and reliability of children’s and adolescents’ pain language. Pain. 1990;41(2):151–159. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90019-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]