Abstract

Blood transcriptional profiling is a powerful tool for understanding global changes after infection, and may be useful for prognosis and prediction of drug treatment responses. This study characterizes the effects of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection on gene expression by analyzing blood samples from 10 treatment-naïve HCV patients and 6 healthy volunteers. Differential expression analysis of microarray data from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) identified a 136-gene signature, including 66 genes elevated in infected individuals. Most of the upregulated genes were associated with interferon (IFN) activity (including members of the OAS and MX families, ISG15, and IRF7), suggesting an ongoing immune response. This HCV signature was also found to be consistently enriched in many other viral infection and vaccination datasets. These genes were validated using a second cohort composed of 5 HCV patients and 5 healthy volunteers, confirming the upregulation of the IFN signature. In summary, this is the first study to directly compare blood transcriptional profiles from HCV patients with healthy controls. The results show that chronic HCV infection has a pronounced effect on gene expression in PBMCs of infected individuals, and significantly elevates the expression of a subset of IFN-stimulated genes.

Introduction

It is estimated that there are 2.7 million cases of chronic hepatitis C infection in the United States, and ∼170 million worldwide (Deuffic-Burban and others 2007). Of these, between 5% and 10% will advance to cirrhosis over the course of infection, and ∼1%–3% of cirrhotic patients will develop hepatocellular carcinoma annually (Kagawa and Keeffe 2010). Currently, no vaccine exists to prevent hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and the standard treatment regimen, which consists of 48 weeks of Interferon-α (IFN-α) plus ribavirin, is associated with a number of serious side-effects and is only moderately effective. IFN therapy results in a sustained response (clearance of the virus 6 months post-therapy) in only about 25%–50% of patients infected with genotype 1 (Conjeevaram and others 2006). More recently, a number of new protease inhibitors have been introduced, which increase the response rate to near 80%, although to date, these inhibitors have only been used in combination with IFN/ribavirin (Pockros 2011).

Genome-wide expression profiling is a powerful tool for understanding the global changes after infection with hepatitis C. Many previous studies have analyzed liver biopsies from HCV-infected patients to identify potential biomarkers correlating with progression to fibrosis (Smith and others 2003, 2006), and the preactivation of IFN-stimulated genes has been suggested as a negative predictor of response to standard therapy (Chen and others 2005). However, the liver is not an ideal tissue for analysis over time, as biopsies are highly invasive and carry risks. An alternative approach involves studying hematological gene expression profiles, which are becoming increasingly popular and have already proven informative in a wide variety of diseases and conditions (Twine and others 2003; Sharma and others 2005; Tsuang and others 2005; Ramilo and others 2007).

The impact of chronic HCV infection on blood transcriptional profiles remains unclear, as a direct comparison with healthy controls has yet to be carried out. Most existing studies focus on predicting IFN therapy response using peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) gene expression profiles from HCV-infected individuals. However, these efforts have largely failed, even where paired liver biopsies from the same patients have been successful (Sarasin-Filipowicz and others 2008; Taylor and others 2007, 2008). The lack of a predictive treatment–response signature in PBMCs may indicate that HCV has little (if any) measurable effect on gene expression in the blood, although it is also possible that gene expression changes induced by chronic HCV infection are independent of the response to IFN therapy. Unfortunately, because no previous studies have included blood samples from healthy controls to compare against, it has not been possible thus far to differentiate between these hypotheses.

Due to the tendency of chronically infected patients to develop immune exhaustion (Rehermann 2007; Thimme and others 2012), and because the primary reservoir of HCV is the liver, there is some debate as to whether HCV should be expected to affect PBMC gene expression at all. However, there are reasons to believe that HCV will still have a measurable impact on hematological gene expression. There have been contradictory reports of infection of PBMCs by the virus (Bartolomé and others 1993; Meier and others 2001; Castillo and others 2005), which would likely cause a pattern of expression in the infected PBMCs that is similar in some respects to those found in the liver. It has also been shown that double-stranded RNA can be transferred from infected hepatocytes to plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), subsequently inducing large amounts of IFN production (Takahashi and others 2010). Both the circulation of these cytokines and the potential transiting of these IFN-producing pDCs back into the blood could have a pronounced effect on gene expression in PBMCs. Indeed, several studies of other chronic diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis, have been associated with significant IFN response signatures in the blood (Bennett and others 2003; van der Pouw Kraan and others 2007; Higgs and others 2011), although whether a similar effect exists in chronic viral infections has not previously been shown.

In this article, we compare gene expression patterns from PBMCs of chronically infected HCV patients with a group of healthy volunteers. We show that there is a distinct gene expression signature associated with chronic HCV infection, including many genes related to inflammation and the IFN response. The set of induced genes was validated in a second cohort. This HCV signature overlaps many other antiviral immune responses and vaccinations, but is not shared with bacterial responses. Our results identify a signature of chronic HCV infection, and suggest that blood gene expression profiling may provide useful markers for the immune status of HCV patients.

Methods

Patient recruitment

The primary HCV cohort used in this study was previously described in (Taylor and others 2008). Whole blood was collected from a subgroup of these patients, who were infected with genotype 1 hepatitis C, before initiation of treatment at the Indiana University School of Medicine. Control blood samples were harvested from healthy student volunteers. All study participants signed a consent form before blood was drawn. This experiment was approved by the Indiana University Human Subjects Committee. Treatment-naïve patients for the validation HCV cohort were recruited by hepatologists in the outpatient hepatitis clinic within the Yale Liver Center. Healthy volunteers were recruited from Yale's PhenoGenetic Cohort of Healthy controls. Informed consent was obtained before acquisition of blood samples from all participants, and the protocol was approved by the Human Research Protection Program (HRPP) at the Yale University School of Medicine. Clinical characteristics for all subjects involved in these studies can be found in Table 1, and detailed characteristics of the HCV patients can be found in the Supplementary Table S1 (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/jir). While the samples analyzed here are from treatment-naïve HCV patients, all of these patients subsequently received standard IFN therapy, and were followed at least 12 weeks to determine treatment response (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics for HCV Patients and Healthy Subjects

| |

Primary cohort |

Validation cohort |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | HCV patients (n=10) | Healthy controls (n=6)a | HCV patients (n=5) | Healthy controls (n=5) |

| Mean age (year) | 49.9±5.5 | <30 | 52.4±9.8 | 40.4±7.2 |

| Gender (M/F) | 10/0 | 5/1 | 2/3 | 1/4 |

| Therapy response (EVR/NR) | 9/1 | — | 2/2 | — |

| Genotype (1a/1b) | 7/3 | — | 2/3 | — |

| Mean fibrosis score (metavir) | 2.9±1.1 | — | 3.2±0.8 | — |

| Serum ALT (IU/L) | 84.1±36.5 | — | 61.2±25.6 | — |

| Log10 HCV RNA level (IU/mL) | 6.4±0.6 | — | 6.5±0.6 | — |

The 2 healthy subjects removed from our analysis are not shown in this table.

HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Sample processing

PBMCs were isolated from the whole-blood samples of the primary cohort using centrifugation through a 10-mL Ficoll-Hypaque gradient (Amersham/Pharmacia), and RNA was isolated within a few hours as previously described (Taylor and others 2007). RNA was then processed according to the protocols recommended by Affymetrix, and run on an Affymetrix Human Genome U133 array. For the validation cohort, PBMCs were isolated from whole blood by density-gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare) centrifugation. Total RNA was isolated from PBMCs using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen), and the quality of total RNA was evaluated by the A260/A280 ratio and by electrophoresis on an Agilent Bioanalyzer. All subsequent processing, hybridization to the Illumina HumanHT-12 microarray, and quality control analyses were carried out by the Yale Center for Genome Analysis using standard protocols.

Data preparation

Microarray data from the primary cohort were normalized using the GCRMA package in bioconductor. After normalization, Principle Component Analysis was used to identify major patterns in the data (Supplementary Fig. S1a), which revealed that the HCV samples were split into 2 groups based on the sample preparation time. Batch-correction techniques were applied to remove these effects (see Supplementary Methods), and the data then separated into 2 distinct groups representing the healthy and HCV samples. However, 2 of the healthy samples consistently clustered within the HCV group (Supplementary Fig. S1b). Since the healthy subjects were volunteers and were never screened for infections, we hypothesize that these subjects were most likely suffering from an unknown or unreported infection, causing an immune response similar to HCV-infected patients. Therefore, these 2 expression profiles were excluded from subsequent analyses. We have verified that removing these outliers does not qualitatively alter the resulting HCV signature (data not shown). Microarray data from the validation cohort underwent quantile normalization using the BeadArray package in bioconductor. Basic quality control analyses did not reveal any abnormalities in these data, so no further preprocessing was applied. Microarray data are available through the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO): GSE40224.

Data analysis

Differential expression analysis

Differentially expressed probe sets were determined by comparing samples from HCV-infected patients versus healthy volunteer subjects using the LIMMA package in BioConductor (Smyth 2004). Significance was defined using a false discovery rate cutoff of 0.05 using the method of Benjamini and Hochberg, and a minimum absolute fold change of 2×.

Functional analysis

Related gene expression studies were identified using the online version of ProfileChaser (Engreitz and others 2011) to search through the 3000 annotated gene expression datasets available in the Gene Expression Omnibus. The default settings were used. The enrichment of gene ontology (GO) categories was calculated using DAVID (Huang and others 2009), which uses a modified Fisher's exact test to identify over-represented categories in a set of genes. Statistical significance was defined by a false discovery rate (FDR) lower than 0.05.

Microarray deconvolution

The fraction of each cell subset from a single PBMC transcriptional profile was estimated by deconvolution using the methods described in (Abbas and others 2009). Subset-specific expression data used for deconvolution were downloaded from the Supplementary Materials in Abbas and others (2009). The predicted proportions of related subsets were added together to generate the final cell fraction (eg, CD4+ T cell+CD8+ T cell=Proportion of T cells).

Enrichment analysis

Gene set enrichments were calculated using the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) Web tool from the Broad Institute (www.broadinstitute.org/gsea) (Subramanian and others 2005). Genes were rank-ordered by their signal-to-noise ratio, and the enrichment score was calculated using the classic enrichment statistic. Significance was determined using 1,000 permutations, and gene sets were considered significantly enriched if the P value was below 0.05.

Results

The chronic HCV infection signature in PBMCs

PBMC samples from 10 chronic HCV patients and 6 healthy volunteers were characterized using gene expression microarray analysis (Table 1). The HCV patients were all treatment-naïve and infected with genotype 1 HCV. We first sought to characterize the general trends in these data by identifying previously published studies with similar overall gene expression changes. Twelve such studies were identified using ProfileChaser (Engreitz and others 2011), all of which examined either monocyte differentiation or the response of cell cultures to IFN (FDR<0.01) (Supplementary Table S2). These results suggest that the gene expression profile of chronic HCV infection broadly resembles an ongoing immune response, including active IFN production and cell differentiation in the blood.

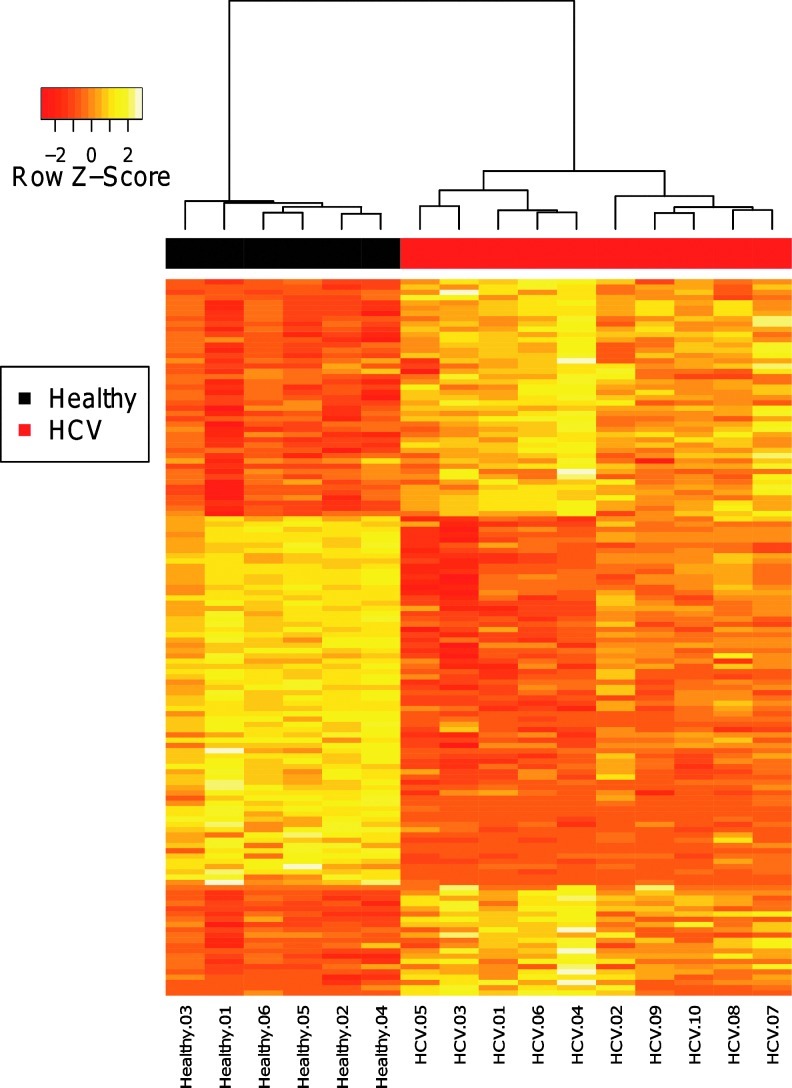

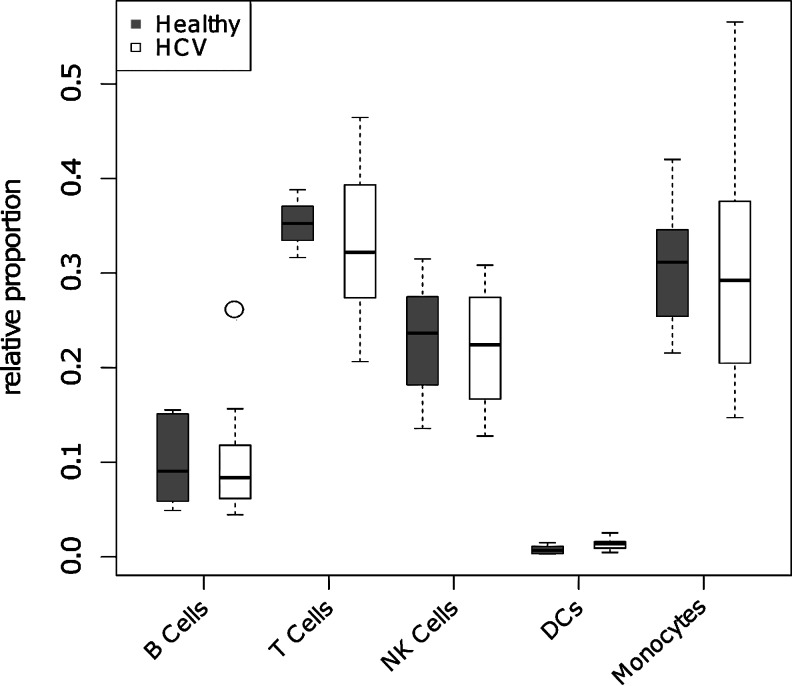

Differential expression analysis identified 136 significantly altered probe sets corresponding to 109 unique genes (FDR<0.05 and |Fold Change| ≥2) (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S3). This signature contained 53 genes that were upregulated in the HCV patients, and 56 genes that were downregulated relative to the healthy volunteers. These gene expression differences are likely to reflect phenotypic changes in PBMC subsets, rather than changes in PBMC subset composition, as no significant differences were found in the estimated cell proportions between the chronic HCV patients and healthy volunteers (Fig. 2). This is consistent with previous studies showing cell profiles in HCV patients are comparable to healthy controls (Corado and others 1997), although conflicting reports suggest that some natural killer cell subsets are negatively affected (Golden-Mason and others 2008). Thus, we have identified a set of genes that are differentially regulated in the blood of chronically infected HCV patients.

FIG. 1.

The chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) gene expression signature. Expression values for each of the 136 probe sets (rows) that were differentially expressed in chronic HCV patients are shown for each of the subjects (columns) in the primary cohort. Expression values are row-normalized and color-coded to range from red (downregulated) to yellow (upregulated). Hierarchical clustering of the subjects effectively separates HCV (red) and healthy (black) subjects.

FIG. 2.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell subset composition is similar in HCV patients and healthy volunteers. Microarray deconvolution was used to estimate the proportions of individual cell types from the expression profile from HCV (open boxes) and healthy (filled boxes) subjects using the methods described in (Abbas and others 2009). HCV and healthy cell type proportions were compared using a T test (P>0.05 for all cases).

HCV patients show activation of IFN-stimulated genes

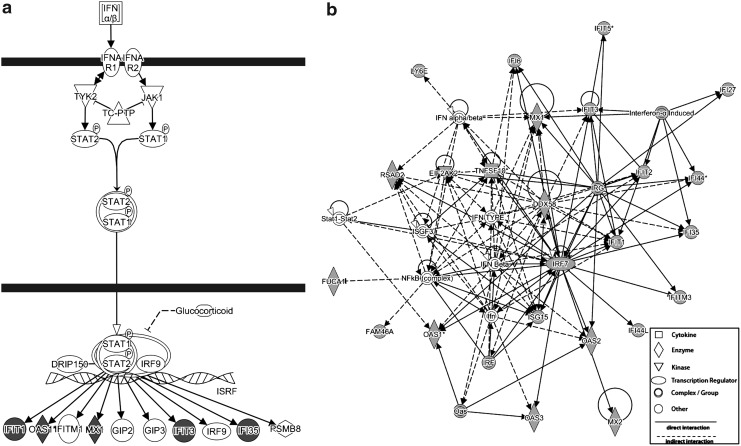

The functional implications of the chronic HCV signature were investigated using GO analysis. Upregulated signature genes were significantly enriched for several terms related to the immune response (see Supplementary Table S4), reflecting the activation of antiviral pathways. This profile is characteristic of a variety of infections (Nascimento and others 2009; Querec and others 2009; Huang and others 2011; Nakaya and others 2011), and most likely reflects the response of immune cells to infected hepatocytes. Pathway analysis using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) tool associated these genes with the IFN pathway, as many Type I interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) were upregulated (Fig. 3a), including key antiviral effectors such as OAS1 and MX1. The activity of these ISGs is linked through regulation by ISGF3 (IRF9), IRF7, and NFKB (Supplementary Fig. S2a), important transcription factors in both the innate and adaptive immune response.

FIG. 3.

The upregulated HCV gene signature is enriched for interferon (IFN) pathway genes. Ingenuity pathway analysis was used to find significantly enriched pathways and networks among the genes that were upregulated in chronic HCV infection. (a) The IFN pathway was found to be significantly enriched (P<0.0001), with several signature genes (shaded) occurring downstream of Jak-Stat signaling. (b) Many direct (solid arrow) and indirect (dashed arrow) interactions were identified among the signature genes (shaded), and others related to the IFN response.

To confirm the upregulated HCV signature, gene expression microarray analysis was carried out on PBMC samples from a second (validation) cohort composed of 5 chronic HCV patients and 5 healthy volunteers (Table 1). All HCV patients were infected with genotype 1, were treatment naïve, and shared similar clinical characteristics with the primary cohort (Table 1). GSEA (Subramanian and others 2005) demonstrated that the upregulated HCV signature from the primary cohort was significantly positively enriched in these data (Fig. 4), confirming that the majority of these genes are consistently upregulated among HCV patients in the validation cohort. Indeed, most of the genes were among the most highly expressed, with ∼30% induced >1.5-fold, and more than 60% induced >1.2-fold. However, in the validation cohort, none of the individual genes, whether in the HCV signature or otherwise, met the more stringent criteria used in the primary cohort. This is not surprising, given the small size of this cohort and the high variability characteristic of human studies, and makes the use of GSEA a more appropriate method for comparison. Overall, these results show that chronic HCV is associated with an IFN response in the blood of infected patients.

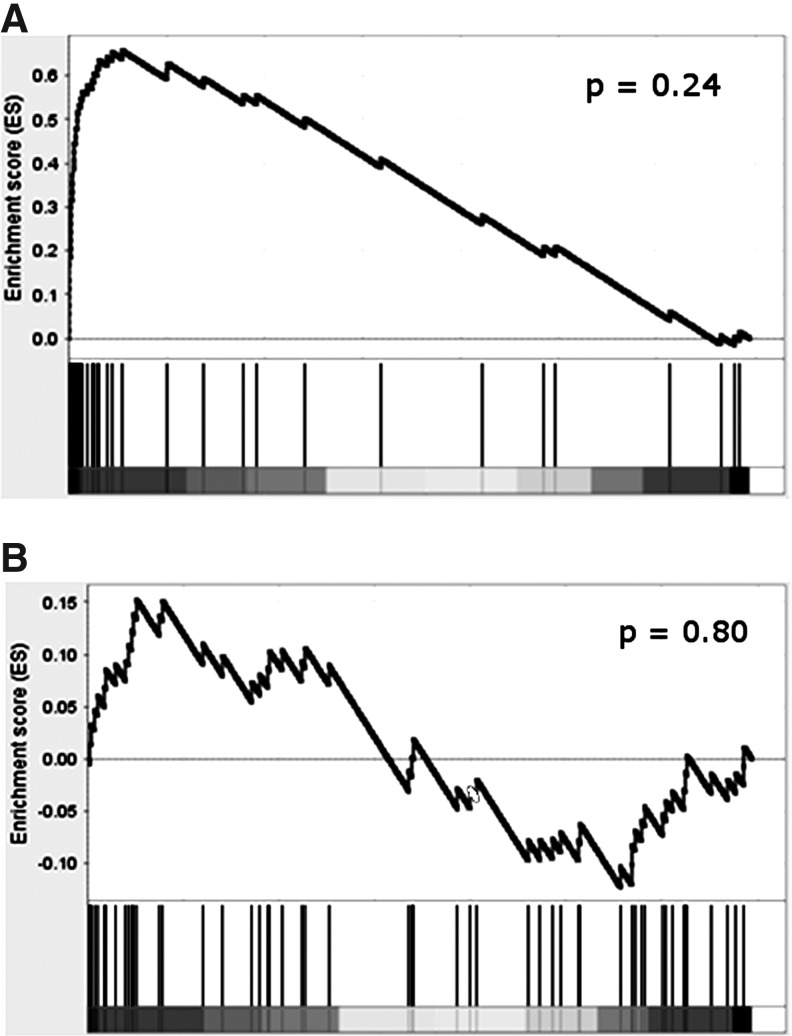

FIG. 4.

Validation of the upregulated HCV signature in an independent HCV patient cohort. The enrichment of the upregulated (A) and downregulated (B) components of the HCV signature was determined in a validation cohort using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (Subramanian and others 2005). Genes in the validation dataset were ranked by their signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) comparing HCV patients with healthy volunteers (x-axis), from most upregulated (left) to most downregulated (right) (grayscale bar represents deviation of SNR from 0). Starting from the most upregulated gene, a running-sum statistic (y axis) was calculated at each gene based on the proportion of genes preceding it that are in the HCV signature (vertical black bars). The enrichment score is the maximum deviation of this running sum from zero. Statistical significance for the enrichment score was calculated using 1,000 permutations of phenotype labels: (a) P=0.24; (b) P=0.80.

Chronic HCV infection may be associated with reduced expression of some cytokine genes

In addition to elevated levels of antiviral genes, our analysis of gene expression patterns also identified many genes that were repressed in HCV patients compared to healthy controls. GO analysis for these downregulated genes identified a number of terms related to immune response, as well as many related to cytokine activity, reflecting the repression of genes such as CXCL5 and CCL24, which have not previously been linked to HCV infection. We found that most of the downregulated genes were associated with gene patterns observed in inflammatory diseases such as ulcerative colitis and rheumatoid arthritis, suggesting that these patients are experiencing a repression of a component of the immune system related to inflammation. Pathway analysis using the IPA tool linked these genes to the interleukin (IL)-17 pathway (P<0.001) (Fig. 3b), which may reflect a suppression of inflammation in the patients due to the chronic nature of HCV infection. Many of these cytokines are also downstream of NFKB activation and the IL-8 pathway (Supplementary Fig. S2b), and genes such as IL-8 (CXCL8), CXCL1, CXCL3, and CXCL5 all bind to the IL-8RB (CXCR2) cell surface receptor. However, unlike the upregulated HCV genes, the downregulated gene set did not show a consistent pattern of regulation in the validation dataset (Fig. 4B). Thus, we were unable to confirm repression of these genes as a general characteristic of chronic HCV infection.

The HCV signature resembles other viral infections and vaccinations

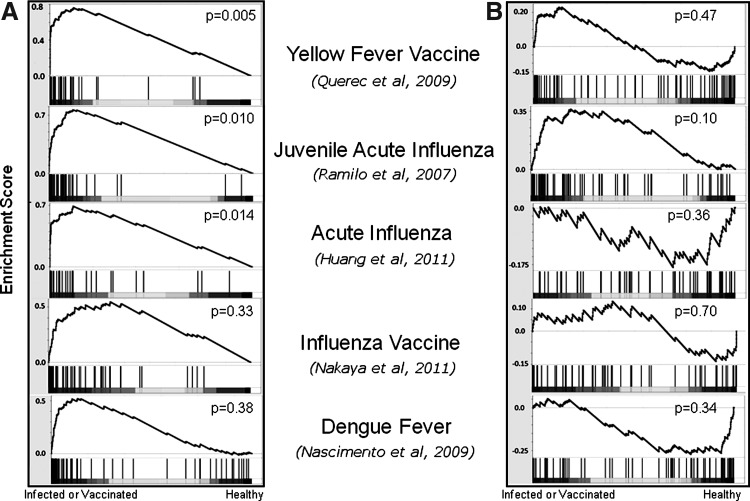

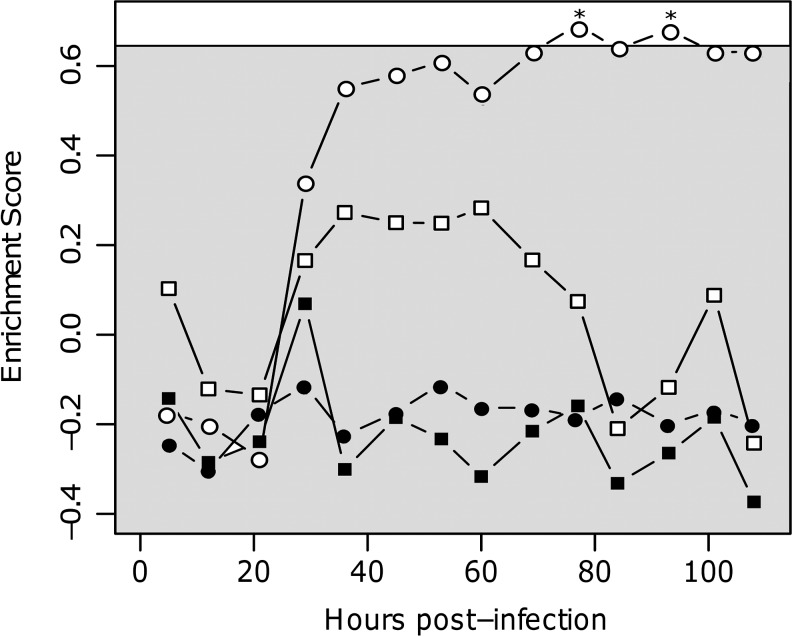

The specificity of the HCV signature was examined by analyzing the behavior of signature genes in the responses to other viral infections and vaccinations. Specifically, GSEA (Subramanian and others 2005) was used to calculate the enrichment of the up- and downregulated signature in 5 datasets: yellow fever vaccination (Querec and others 2009), influenza vaccination (Nakaya and others 2011), acute influenza infection in adults (Huang and others 2011) and in juveniles (Ramilo and others 2007), and acute Dengue hemorrhagic fever infection (Nascimento and others 2009). The upregulated HCV signature was significantly enriched in the blood of subjects after yellow fever vaccination, as well as in both adult and juvenile acute influenza patients (P=0.005, P=0.014, and P=0.01, respectively, Fig. 5A). While a similar pattern of positive enrichment was found in the influenza vaccination response and Dengue fever infection, these cases failed to reach statistical significance (P>0.05). As the HCV signature contains many IFN-stimulated genes, this enrichment likely reflects the actions of the innate immune system. The association with innate immunity was further confirmed by the timing of enrichment in an influenza infection time-series experiment. Huang and others (2011) infected 11 subjects with influenza virus, and gene expression analysis was carried out on blood samples approximately every 8 h up to 108 h postexposure. We found that the enrichment of the upregulated signature started to increase in the blood of these subjects ∼24 h post-infection, consistent with the activation of innate immunity (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the enrichment was only significant in the subjects who became symptomatic. In contrast to the upregulated HCV gene signature, the downregulated signature was not consistently modulated by acute viral infection or vaccination (Figs. 5B and 6). If this signature is accurate, this result may be explained by an HCV-specific subversion of the innate immune response, or possibly the consequence of chronic infection, leading to immune exhaustion and downregulation of inflammation pathways.

FIG. 5.

Enrichment of upregulated HCV signature genes in acute viral infections and vaccinations. The enrichment of the upregulated (A) and downregulated (B) components of the HCV signature was examined in a variety of viral infection datasets using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis, as described in Figure 4.

FIG. 6.

Genes upregulated in chronic HCV are enriched after influenza infection. Time-course data from the influenza infection study by (Huang and others 2011) was used to rank-order genes by their signal-to-noise ratio at various times postinfection (compared to preinfection levels). The enrichment of the upregulated HCV signature genes (open) and the downregulated signature genes (filled) was determined at each time point for both symptomatic (circles) and asymptomatic (squares) subjects. P values were estimated individually for each point by a permutation test (*P<0.05), with the approximate average cutoff for statistical significance shown by the shaded box.

Specificity of the HCV signature compared to bacterial infections

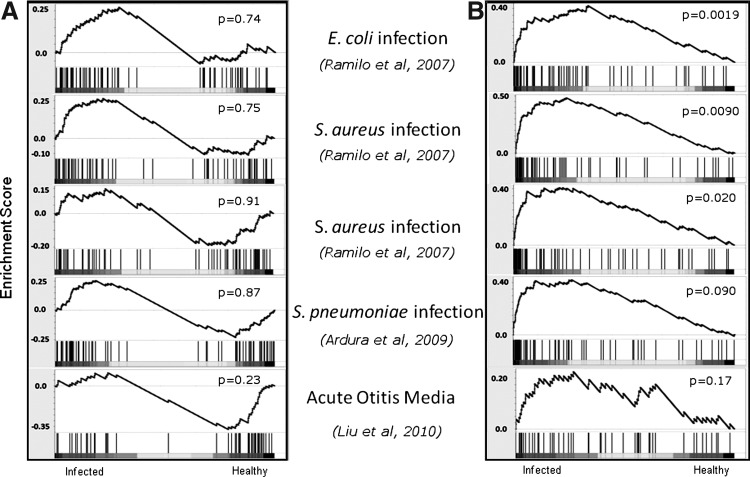

To understand whether the HCV signature was specific to viral responses, the enrichment of signature genes was also determined in 5 antibacterial response studies, including the responses to Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae (Ramilo and others 2007; Ardura and others 2009; Liu and others 2010). As expected, the upregulated HCV signature was not enriched in any of these bacterial infections (P>0.05, Fig. 7A), with the genes showing no discernible pattern of regulation either up or down. Surprisingly, the downregulated HCV signature genes were significantly positively enriched in 4 of the 5 responses investigated (P<0.05, Fig. 7B), that is, the genes that were repressed in chronic HCV infection tended to be elevated in antibacterial responses. Analysis of the leading edge of the signature indicated that the same genes tended to be among the most highly upregulated. These results suggest that despite the variable response of these genes observed in the validation cohort, the genes in the downregulated signature can behave as a coherent group under certain conditions.

FIG. 7.

Enrichment of downregulated HCV signature genes in antibacterial responses. The enrichment of upregulated (A) and downregulated (B) components of the HCV signature was examined in a variety of bacterial infection datasets using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis, as described in Figure 4.

Discussion

In this article, we have used transcriptional profiling of HCV patients and healthy controls to define a blood gene expression signature of chronic HCV infection. While several previous studies have compared gene expression patterns in the blood of HCV patients that differ in their treatment responses (Taylor and others 2007, 2008; Sarasin-Filipowicz and others 2008), these studies do not address whether chronic HCV infection modulates blood gene expression profiles. In this study, we included PBMC samples from both chronic HCV patients and healthy controls to establish a chronic HCV signature containing 53 genes that are induced and 56 genes that are repressed. The set of induced genes was confirmed using an independent validation cohort. However, the downregulated gene signature could not be confirmed. Pathway analysis using both GO and IPA revealed that the upregulated gene signature was enriched for IFN-stimulated genes. In fact, ∼90% of the genes upregulated in the HCV signature were previously identified as being regulated by IFN in PBMCs in vivo or in vitro (Taylor and others 2004, 2007, 2008). These results suggest that this signature represents an ongoing innate immune response composed in large part of genes that normally respond to IFN, although it is unclear what the source of the IFN is.

Although enriched for ISGs, the HCV signature is distinct from that produced by IFN treatment in vivo. Taylor and colleagues have previously reported transient expression changes in many genes following IFN administration in vivo (Taylor and others 2008), including mRNA from CXCL10, IL-1Ra, JAK2 and many others. The chronically infected HCV patient signature reported herein is distinct from this list; with the exception of TNFSF10, none of these transient genes were significantly upregulated in the HCV patients. These differences most likely reflect the chronic nature of the illness. Previous studies have also identified many genes of the complement and coagulation pathways (as defined by KEGG) that were upregulated in response to IFN therapy of chronic HCV patients. This was not seen in this group of patients, again indicating differences between therapeutic injection of IFN and chronic endogenous production due to the persisting HCV infection.

The presence of a large number of downregulated genes in our gene signature is unexpected. Although many of the chemokines of this cluster, including CXCL1, CXCL5, and CCL22, have previously been shown to be suppressed by IFN treatment in PBMCs (Taylor and others 2004), none of these genes have been linked to HCV infection. Many of the genes in the downregulated gene set, such as IL-8 (CXCL8), CXCL1, CXCL3, and CXCL5, bind to the IL-8RB cell surface receptor, and together with IL-1β and IL-6, are all major mediators of the inflammatory response. The key immune regulators IL-1-α and IL-1-β are also downregulated in HCV-infected cells, which may explain the suppression of many of the genes related to immune response. Still, whether these genes are truly repressed as a result of chronic HCV infection is unclear, as we were unable to validate this observation in an independent (although small) validation cohort. The finding that these genes are enriched among upregulated genes in antibacterial responses raises the possibility that some of the healthy volunteers in the primary HCV cohort had unidentified bacterial infections. However, it is possible that the chronic nature of the infection is leading to immune exhaustion in the PBMCs, causing some immune pathways to be suppressed, or that HCV is actively interfering with gene expression in the blood via mechanisms similar to those found in infected hepatocytes (Short 2009). Further studies will be required to definitively identify conclusions from this set of genes.

A comparison of the HCV signature with the expression profiles of other immune responses revealed that the upregulated gene signature was largely specific to viral infections. This may reflect the activation of toll-like receptors (TLRs) within infected cells, which recognize specific viral molecular patterns and lead to the upregulation of IFN. In contrast, while some bacterial infections have been known to activate TLRs, there is much less IFN produced in response to bacteria. Interestingly, the downregulated HCV signature was consistently induced after bacterial infection, suggesting that these genes can operate as a group in response to some alternative stimulus.

Future studies should compare the HCV gene signature with expression profiles from other chronic illnesses, such as chronic Hepatitis B. Hepatitis B and C viruses are very different in how they interact with the host innate immune response (Wieland and Chisari 2005). Therefore, comparing the PBMC gene expression signatures in chronically infected patients could provide a valuable insight into the persistence and pathogenesis of these 2 viruses. In addition, a comparative analysis with nonvirus-associated liver disease would provide a means of delineating the effects of inflammation of the liver, a significant portion of HCV morbidity (Poynard and others 2003), from that of viral infection. Unfortunately, such datasets are not currently available in the public domain, but will be important to generate moving forward. Additionally, it would be interesting to investigate how the HCV signature is modulated by genetic polymorphisms. Recent studies have associated polymorphisms in IL-28B with the response to IFN therapy (Ge and others 2009; Suppiah and others 2009; Tanaka and others 2009). However, given the significant association between the IL-28B polymorphisms and treatment response, combined with the lack of a treatment–response signature from blood gene expression, we do not expect to see a dramatic impact of this particular polymorphism on the HCV signature.

We have defined a blood transcriptional signature of chronic HCV by directly comparing PBMC gene expression profiles from chronic HCV-infected patients with healthy controls. Our results demonstrate that chronic HCV infection has a pronounced effect on blood gene expression in infected individuals, leading to the upregulation of a subset of ISGs. Correlation of this signature with clinical factors, such as liver fibrosis or response to therapy, may lead to useful biomarkers and help assess the immune status of HCV patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ruth Montgomery for her advice and her critical reading of the manuscript. This project was partially funded by NIH Grant DK34989: Silvio O. Conte Digestive Diseases Research Core Centers - 5P30DK034989. C.R.B was supported in part by an NIH Grant T15 LM07056 from the National Library of Medicine.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Abbas AR. Wolslegel K. Seshasayee D. Modrusan Z. Clark HF. Deconvolution of blood microarray data identifies cellular activation patterns in systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardura MI. Banchereau R. Mejias A. Di Pucchio T. Glaser C. Allantaz F. Pascual V. Banchereau J. Chaussabel D. Ramilo O. Enhanced monocyte response and decreased central memory T cells in children with invasive Staphylococcus aureus infections. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomé J. Castillo I. Quiroga JA. Navas S. Carreño V. Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA in serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Hepatol. 1993;17(Suppl. 3):S90–S93. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80431-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett L. Palucka AK. Arce E. Cantrell V. Borvak J. Banchereau J. Pascual V. Interferon and granulopoiesis signatures in systemic lupus erythematosus blood. J Exp Med. 2003;197(6):711–723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo I. Rodríguez-Iñigo E. Bartolomé J. de Lucas S. Ortíz-Movilla N. López-Alcorocho JM. Pardo M. Carreño V. Hepatitis C virus replicates in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with occult hepatitis C virus infection. Gut. 2005;54(5):682–685. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.057281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. Borozan I. Feld J. Sun J. Tannis L-L. Coltescu C. Heathcote J. Edwards AM. McGilvray ID. Hepatic gene expression discriminates responders and nonresponders in treatment of chronic hepatitis C viral infection. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(5):1437–1444. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conjeevaram HS. Fried MW. Jeffers LJ. Terrault NA. Wiley-Lucas TE. Afdhal N. Brown RS. Belle SH. Hoofnagle JH. Kleiner DE. Howell CD. Peginterferon and ribavirin treatment in African American and Caucasian American patients with hepatitis C genotype 1. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(2):470–477. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corado J. Toro F. Rivera H. Bianco NE. Deibis L. De Sanctis JB. Impairment of natural killer (NK) cytotoxic activity in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;109(3):451–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4581355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuffic-Burban S. Poynard T. Sulkowski MS. Wong JB. Estimating the future health burden of chronic hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus infections in the United States. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14(2):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engreitz JM. Chen R. Morgan AA. Dudley JT. Mallelwar R. Butte AJ. ProfileChaser: searching microarray repositories based on genome-wide patterns of differential expression. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(23):3317–3318. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge D. Fellay J. Thompson AJ. Simon JS. Shianna KV. Urban TJ. Heinzen EL. Qiu P. Bertelsen AH. Muir AJ. Sulkowski M. McHutchison JG. Goldstein DB. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461(7262):399–401. doi: 10.1038/nature08309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden-Mason L. Madrigal-Estebas L. McGrath E. Conroy MJ. Ryan EJ. Hegarty JE. O'Farrelly C. Doherty DG. Altered natural killer cell subset distributions in resolved and persistent hepatitis C virus infection following single source exposure. Gut. 2008;57(8):1121–1128. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.130963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs BW. Liu Z. White B. Zhu W. White WI. Morehouse C. Brohawn P. Kiener PA. Richman L. Fiorentino D. Greenberg SA. Jallal B. Yao Y. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, myositis, rheumatoid arthritis and scleroderma share activation of a common type I interferon pathway. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(11):2029–2036. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.150326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang DW. Sherman BT. Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. Zaas AK. Rao A. Dobigeon N. Woolf PJ. Veldman T. Oien NC. McClain MT. Varkey JB. Nicholson B. Carin L. Kingsmore S. Woods CW. Ginsburg GS. Hero AO., 3rd Temporal dynamics of host molecular responses differentiate symptomatic and asymptomatic influenza a infection. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(8):e1002234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa T. Keeffe EB. Long-term effects of antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepat Res Treat. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/562578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K. Casey J. Pichichero M. Serum intercellular adhesion molecule 1 variations in young children with acute otitis media. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17(12):1909–1916. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00194-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier V. Mihm S. Braun Wietzke P. Ramadori G. HCV-RNA positivity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with chronic HCV infection: does it really mean viral replication? World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7(2):228–234. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i2.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya HI. Wrammert J. Lee EK. Racioppi L. Marie-Kunze S. Haining WN. Means AR. Kasturi SP. Khan N. Li G-M. McCausland M. Kanchan V. Kokko KE. Li S. Elbein R. Mehta AK. Aderem A. Subbarao K. Ahmed R. Pulendran B. Systems biology of vaccination for seasonal influenza in humans. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(8):786–795. doi: 10.1038/ni.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento EJM. Braga-Neto U. Calzavara-Silva CE. Gomes ALV. Abath FGC. Brito CAA. Cordeiro MT. Silva AM. Magalhães C. Andrade R. Gil LHVG. Marques ETA., Jr Gene expression profiling during early acute febrile stage of dengue infection can predict the disease outcome. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockros PJ. Drugs in development for chronic hepatitis C: a promising future. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2011;11(12):1611–1622. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2011.627851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poynard T. Yuen M-F. Ratzin V. Lai CL. Viral hepatitis C. Lancet. 2003;362(9401):2095–2100. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querec TD. Akondy RS. Lee EK. Cao W. Nakaya HI. Teuwen D. Pirani A. Gernert K. Deng J. Marzolf B. Kennedy K. Wu H. Bennouna S. Oluoch H. Miller J. Vencio RZ. Mulligan M. Aderem A. Ahmed R. Pulendran B. Systems biology approach predicts immunogenicity of the yellow fever vaccine in humans. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(1):116–125. doi: 10.1038/ni.1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramilo O. Allman W. Chung W. Mejias A. Ardura M. Glaser C. Wittkowski KM. Piqueras B. Banchereau J. Palucka AK. Chaussabel D. Gene expression patterns in blood leukocytes discriminate patients with acute infections. Blood. 2007;109(5):2066–2077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-002477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehermann B. Chronic infections with hepatotropic viruses: mechanisms of impairment of cellular immune responses. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27(2):152–160. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarasin-Filipowicz M. Oakeley EJ. Duong FHT. Christen V. Terracciano L. Filipowicz W. Heim MH. Interferon signaling and treatment outcome in chronic hepatitis C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(19):7034–7039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707882105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P. Sahni NS. Tibshirani R. Skaane P. Urdal P. Berghagen H. Jensen M. Kristiansen L. Moen C. Sharma P. Zaka A. Arnes J. Sauer T. Akslen LA. Schlichting E. Børresen-Dale A-L. Lönneborg A. Early detection of breast cancer based on gene-expression patterns in peripheral blood cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7(5):R634–R644. doi: 10.1186/bcr1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short JAL. Viral evasion of interferon stimulated genes. Biosci Horiz. 2009;2(2):212–224. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MW. Walters K-A. Korth MJ. Fitzgibbon M. Proll S. Thompson JC. Yeh MM. Shuhart MC. Furlong JC. Cox PP. Thomas DL. Phillips JD. Kushner JP. Fausto N. Carithers RL., Jr. Katze MG. Gene expression patterns that correlate with hepatitis C and early progression to fibrosis in liver transplant recipients. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(1):179–187. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MW. Yue ZN. Korth MJ. Do HA. Boix L. Fausto N. Bruix J. Carithers RL., Jr. Katze MG. Hepatitis C virus and liver disease: global transcriptional profiling and identification of potential markers. Hepatology. 2003;38(6):1458–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3(1) doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A. Tamayo P. Mootha VK. Mukherjee S. Ebert BL. Gillette MA. Paulovich A. Pomeroy SL. Golub TR. Lander ES. Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(43):15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppiah V. Moldovan M. Ahlenstiel G. Berg T. Weltman M. Abate ML. Bassendine M. Spengler U. Dore GJ. Powell E. Riordan S. Sheridan D. Smedile A. Fragomeli V. Müller T. Bahlo M. Stewart GJ. Booth DR. George J. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-[alpha] and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 2009;41(10):1100–1104. doi: 10.1038/ng.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K. Asabe S. Wieland S. Garaigorta U. Gastaminza P. Isogawa M. Chisari FV. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense hepatitis C virus-infected cells, produce interferon, and inhibit infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(16):7431–7436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002301107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y. Nishida N. Sugiyama M. Kurosaki M. Matsuura K. Sakamoto N. Nakagawa M. Korenaga M. Hino K. Hige S. Ito Y. Mita E. Tanaka E. Mochida S. Murawaki Y. Honda M. Sakai A. Hiasa Y. Nishiguchi S. Koike A. Sakaida I. Imamura M. Ito K. Yano K. Masaki N. Sugauchi F. Izumi N. Tokunaga K. Mizokami M. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-[alpha] and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet. 2009;41(10):1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/ng.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. Tsukahara T. McClintick J. Edenberg H. Kwo P. Cyclic changes in gene expression induced by Peg-interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin in peripheral blood monocytes (PBMC) of hepatitis C patients during the first 10 weeks of treatment. J Transl Medicine. 2008;6(1):66. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-6-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MW. Grosse WM. Schaley JE. Sanda C. Wu X. Chien S-C. Smith F. Wu TG. Stephens M. Ferris MW. McClintick JN. Jerome RE. Edenberg HJ. Global effect of PEG-IFN-alpha and ribavirin on gene expression in PBMC in vitro. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2004;24(2):107–118. doi: 10.1089/107999004322813354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MW. Tsukahara T. Brodsky L. Schaley J. Sanda C. Stephens MJ. McClintick JN. Edenberg HJ. Li L. Tavis JE. Howell C. Belle SH for the Virahep-C Study Group. Changes in gene expression during pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy of chronic hepatitis C virus distinguish responders from nonresponders to antiviral therapy. J Virol. 2007;81(7):3391–3401. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02640-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimme R. Binder M. Bartenschlager R. Failure of innate and adaptive immune responses in controlling hepatitis C virus infection. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36(3):663–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuang MT. Nossova N. Yager T. Tsuang M-M. Guo S-C. Shyu KG. Glatt SJ. Liew CC. Assessing the validity of blood-based gene expression profiles for the classification of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a preliminary report. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;133B(1):1–5. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twine NC. Stover JA. Marshall B. Dukart G. Hidalgo M. Stadler W. Logan T. Dutcher J. Hudes G. Dorner AJ. Slonim DK. Trepicchio WL. Burczynski ME. Disease-associated expression profiles in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63(18):6069–6075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Pouw Kraan TCTM. Wijbrandts CA. van Baarsen LGM. Voskuyl AE. Rustenburg F. Baggen JM. Ibrahim SM. Fero M. Dijkmans BAC. Tak PP. Verweij CL. Rheumatoid arthritis subtypes identified by genomic profiling of peripheral blood cells: assignment of a type I interferon signature in a subpopulation of patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(8):1008–1014. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.063412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland SF. Chisari FV. Stealth and cunning: hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses. J Virol. 2005;79(15):9369–9380. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9369-9380.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.